CHAPTER 200 Lower Extremity and Knee

CHAPTER 200 Lower Extremity and Knee

Torsional (in-toeing and out-toeing) and angular (physiologic bowlegs and knock knees) variations in the legs are common reasons that parents seek medical attention for their child. Most of these concerns are physiologic and resolve with normal growth. It is important to understand the natural history in order to reassure the family and to identify nonphysiologic disorders that necessitate further intervention. Physiologic disturbances are referred to as variations, and pathologic disturbances are called deformities.

TORSIONAL VARIATIONS

The femur is internally rotated (anteversion) at birth about 30 degrees, decreasing to about 10 degrees at maturity. The tibia begins with up to 30 degrees of internal rotation at birth and can decrease to a mean of 15 degrees at maturity.

Torsional variations should not cause a limp or pain. Unilateral torsion should raise the index of suspicion for a neurologic (hemiplegia) or neuromuscular disorder.

In-Toeing

Femoral Anteversion

Internal femoral torsion or femoral anteversion is the most common cause of in-toeing in children 2 years or older (Table 200-1). It is at its worst between 4 and 6 years of age, and then resolves. It occurs twice as often in girls. Many cases are associated with generalized ligamentous laxity. The etiology of femoral anteversion is likely congenital, and is common in individuals with abnormal sitting habits such as W-sitting.

TABLE 200-1 Common Causes of In-Toeing and Out-Toeing

| In-Toeing | Out-Toeing |

|---|---|

Clinical Manifestations

The family may give a history of W-sitting, and there may be a family history of similar concerns when the parents were younger. The child may have kissing kneecaps due to increased internal rotation of the femur. While walking, the entire leg will appear internally rotated, and with running the child may appear to have an egg-beater gait where the legs flip laterally. The flexed hip will have internal rotation increased to 80 to 90 degrees (normal 60–70 degrees) and external rotation limited to about 10 degrees. Radiographic evaluation is usually not indicated.

Internal Tibial Torsion

This is the most common cause of in-toeing in a child younger than 2 years old. When it is the result of in utero positioning, it may be associated with metatarsus adductus.

Clinical Manifestations

The child will present with a history of in-toeing. The degree of tibial torsion may be measured using the thigh-foot angle (Fig. 200-1). The patient lies prone on a table with the knee flexed to 90 degrees. The long axis of the foot is compared with the long axis of the thigh. An inwardly rotated foot represents a negative angle and internal tibial torsion. Measurements should be done at each visit to document improvement.

FIGURE 200-1 Thigh-foot angle measurement. The thigh-foot angle is useful for assessment of tibial torsion. The patient lies prone, with knees flexed to 90 degrees. The long axis of the thigh is compared to the long axis of the foot to determine the thigh-foot angle. Negative angles are associated with internal tibial torsion, and positive angles are associated with external tibial torsion.

Treatment of In-toeing

The mainstay of management is identifying patients who have pathologic reasons for in-toeing and reassurance and follow-up to document improvement for patients with femoral anteversion and internal tibial torsion. It can take 7 to 8 years for correction, so it is important to inform families of the appropriate timeline. Braces (Denis Browne splint) do not improve these conditions. The lack of improvement by 2 years of age for children with internal tibial torsion should result in referral to a pediatric orthopedist. Approximately 1% to 2% of all patients with in-toeing will need surgical intervention due to functional disability or cosmetic appearance.

Out-Toeing

External Tibial Torsion

External tibial torsion is the most common cause of out-toeing and may be associated with a calcaneovalgus foot (see Chapter 201). This is often related to in utero positioning. It may improve over time, but because the tibia rotates externally with age, external tibial torsion can worsen. It may be an etiologic factor for patellofemoral syndrome, especially when combined with femoral anteversion. Treatment is usually observation and reassurance, but patients with dysfunction and cosmetic concerns may benefit from surgical intervention.

ANGULAR VARIATIONS

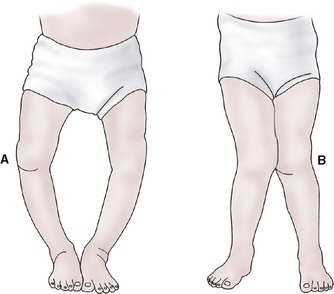

The majority of the patients that present with knock-knees (genu valgum) or bowlegs (genu varum) are normal (Fig. 200-2). Infants are born with maximum genu varum. The lower extremity straightens out around 18 months of age. Children typically progress to maximal genu valgum around 4 years. The legs are usually straight to a slight genu valgum in adulthood.

FIGURE 200-2 Bowleg and knock-knee deformities. A, Bowleg deformity. Bowlegs are referred to as varus angulation (genu varum) because the knees are tilted away from the midline of the body. B, Knock-knee or valgus deformity of the knees. The knee is tilted toward the midline.

(From Scoles P: Pediatric Orthopedics in Clinical Practice. Chicago, Year Book Medical Publishers, 1982, p 84.)

It is important to inquire about family history and assess overall height. A child who is 2 standard deviations (SDs) below normal with angular deformities may have skeletal dysplasia. Dietary history should be obtained, as rickets (see Chapter 31) may cause angular deformities. For genu valgum, following the intermalleolar distance (distance between the two tibial medial malleoli with the knees touching) is used. Measurement of the intercondylar distance (the distance between the medial femoral condyles with the medial malleoli touching) is used for genu varum. These measurements track improvement or progression. When obtaining radiographs, it is important to have the patella, not the feet, facing forward. In the child with external tibial torsion, having the feet facing forward gives the false appearance of bowlegs.

Genu Valgum

Physiologic knock-knees are most common in 3- to 4-year-olds and usually resolve between 5 and 8 years of age. Patients with asymmetrical genu valgum or severe deformity may have underlying disease causing their knock-knees (e.g., renal osteodystrophy, skeletal dysplasia). Treatment is based on reassurance of the family and patient. Surgical intervention may be indicated for severe deformities, gait dysfunction, pain, and cosmesis.

Genu Varum

Physiologic bowlegs are most common in children older than 18 months with symmetrical genu varum. This will generally improve as the child approaches 2 years of age. The most important consideration for genu varum is differentiating between physiologic genu varum and Blount disease (tibia vara).

Tibia Vara (Blount Disease)

Tibia vara is the most common pathologic disorder associated with genu varum. It is characterized by abnormal growth of the medial aspect of the proximal tibial epiphysis, resulting in a progressive varus deformity. Blount disease is classified according to age of onset:

Late onset Blount disease is less common than infantile disease. The cause is unknown, but it is felt to be secondary to growth suppression from increased compressive forces across the medial knee.

Clinical Manifestations

Infantile tibia vara is more common in African Americans, females, and obese patients. Many patients were early walkers. Nearly 80% of patients with infantile Blount disease have bilateral involvement. It is usually painless. The patients will often have significant internal tibial torsion and lower extremity leg-length discrepancy. There may also be a palpable medial tibial metaphyseal beak.

Late onset Blount disease is more common in African Americans, males, and patients with marked obesity. Only 50% have bilateral involvement. The initial presentation is usually painful bowlegs. Late onset Blount disease is usually not associated with palpable metaphyseal beaking, significant internal tibial torsion, or significant leg length discrepancy.

Radiologic Evaluation

Weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of both legs are necessary for the diagnosis of tibia vara. Fragmentation, wedging, and beak deformities of the proximal medial tibia are the major radiologic features of infantile Blount disease. In late onset Blount disease, the medial deformity may not be as readily noticeable. It can be very difficult to tell the difference between physiologic genu varum and infantile Blount disease on radiographs in the patient younger than 2 years of age.

Treatment

Once the diagnosis of Blount disease is confirmed, treatment should begin immediately. The use of orthotics to unload the medial compressive forces can be done in children younger than 3 years of age with a mild deformity. Compliance with this regimen can be difficult. Nonoperative management of more severe Blount disease is contraindicated.

Any patient older than 4 years should undergo surgical intervention. Patients with moderate to severe deformity and patients that fail orthotic treatment also require surgical intervention. Proximal tibial valgus osteotomy with fibular diaphyseal osteotomy is the usual procedure performed.

LEG-LENGTH DISCREPANCY

Leg-length discrepancy (LLD) is common and may be due to differences in the femur, tibia, or both bones. The differential diagnosis is extensive, but common causes are listed in Table 200-2. The majority of the lower extremity growth comes from the distal femur (38%) and the proximal tibia (27%).

TABLE 200-2 Common Causes of Leg-Length Discrepancy

| Congenital | |

| Developmental | |

| Neuromuscular | |

| Infectious | Physeal injury secondary to osteomyelitis |

| Tumors | |

| Trauma | |

| Syndrome |

Measuring Leg-Length Discrepancy

Clinical measurements using bony landmarks (anterior superior iliac spine to medial malleolus) are inaccurate. The teloradiograph is a single radiograph of both legs that can be done in very young children. The orthoradiograph consists of three slightly overlapping exposures of the hips, knees, and ankles. The scanogram consists of three standard radiographs of the hips, knees, and ankles with a ruler next to the extremities. A computed tomography (CT) scanogram is the most accurate measure of LLD. Distal radiography with computer assisted measurement is the most accurate method. The measured discrepancy is followed using Moseley and Green-Anderson graphs.

Treatment

Treating LLD is complex. The physician must take into account the estimated adult height, discrepancy measurements, skeletal maturity, and the psychological aspects of the patient and family. LLD greater than 2 cm usually requires treatment. Shoe lifts can be used, but they will often cause psychosocial problems for the child and may make the shoes heavier and less stable. Surgical options include shortening of the longer extremity, lengthening of the shorter extremity, or a combination of the two procedures. Discrepancies less than 5 cm are treated by epiphysiodesis (surgical physeal closure) of the affected side, while discrepancies greater than 5 cm are treated by lengthening.

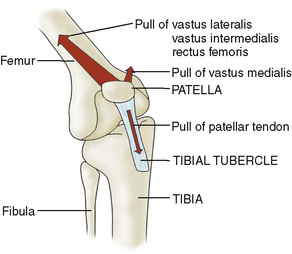

KNEE

The knee joint is constrained by soft tissues rather than the usual geometric fit of articulating bones. The medial and lateral collateral ligaments as well as the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments maintain knee stability. Weight and force transmission can cross articular cartilage and the meniscus. The patellofemoral joint is the extensor mechanism of the knee and a common site of injury in the adolescent (Fig. 200-3).

FIGURE 200-3 Diagram of the knee extensor mechanism. The major force exerted by the quadriceps muscle tends to pull the patella laterally out of the intercondylar sulcus. The vastus medialis muscle pulls medially to keep the patella centralized.

(Modified from Smith JB: Knee problems in children. Pediatr Clin North Am 33:1439, 1986.)

Knee effusion or swelling is a common sign of injury. When the fluid accumulates rapidly after an injury, it is usually a hemarthrosis (blood in the joint) and may indicate a fracture, ligamentous disruption (often of the anterior cruciate ligament, ACL), or meniscus tear. Unexplained knee effusion may occur with arthritis (septic, Lyme disease, viral, postinfectious, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus). It may also occur as a result of overactivity and hypermobile joint syndrome (ligamentous laxity). An aspiration and laboratory evaluation of unexplained effusion can help expedite a diagnosis.

Discoid Lateral Meniscus

Each meniscus is normally semilunar in shape; rarely the lateral meniscus will be disc shaped. A normal meniscus is attached at the periphery and glides anteriorly and posteriorly with knee motion. The discoid meniscus is less mobile, and may tear more easily. When there is inadequate posterolateral attachment, the discoid meniscus can displace anteriorly with knee flexion, causing an audible click. Most commonly, patients will present in late childhood or early adolescence after an injury with knee pain and swelling. The anteroposterior radiographs can show widening of the lateral femoral condyle; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can confirm the diagnosis. Treatment is usually arthroscopic excision of tears and reshaping of the meniscus.

Popliteal Cyst

A popliteal cyst (Baker cyst) is commonly seen in the middle childhood years. The cause is the distension of the gastrocnemius and semimembranous bursa along the posteromedial aspect of the knee by synovial fluid. In adults, Baker cysts are associated with meniscus tears. In childhood, the cysts are usually painless and benign. They often spontaneously resolve, but it may take several years. Knee radiographs are normal. The diagnosis can be confirmed by ultrasound. Treatment is reassurance, since surgical excision is indicated only for progressive cysts or cysts that cause disability.

Osteochondritis Dissecans

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) most commonly involves the knee. It occurs when an area of bone adjacent to the articular cartilage suffers a vascular insult and separates from the adjacent bone. It most commonly affects the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. Patients may complain of knee pain or swelling. The lesions can be seen on anteroposterior, lateral, and tunnel view radiographs. MRI can be helpful in determining the extent of the injury. In young patients with intact articular cartilage, the lesion will often revascularize and heal with rest from activities. The healing process may take several months and requires radiographic follow-up to document healing. With increasing age, the risk for articular cartilage damage and separation of the bony fragment increase. Older patients are more likely to need surgical intervention. Any patient with a fracture of the articular cartilage will not improve without surgical intervention.

Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Osgood-Schlatter disease is a common cause of knee pain at the insertion of the patellar tendon on the tibial tubercle. The stress from a contracting quadriceps muscle is transmitted through the developing tibial tubercle, which can cause a microfracture or partial avulsion fracture in the ossification center. It usually occurs after a growth spurt and is more common in boys. The age at onset is typically 11 years for girls and 13 to 14 years for boys.

Patients will present with pain during and after activity as well as have tenderness and local swelling over the tibial tubercle. Radiographs may be necessary to rule out infection, tumor, or avulsion fracture.

Rest and activity modification are paramount for treatment. Pain control medications and icing may be helpful. Lower extremity flexibility and strengthening exercise programs are important. Some patients may require immobilization. The course is usually benign, but symptoms frequently last 1 to 2 years. Complications can include bony enlargement of the tibial tubercle and avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle.

Patellofemoral Disorders

The patellofemoral joint is a complex joint that depends on a balance between restraining ligaments of the patella, muscular forces around the knee, and alignment for normal function. The interior surface of the patella has a V-shaped bottom which moves through a matching groove in the femur called the trochlea. When the knee is flexed, the patellar ligaments and the majority of the muscular forces pulling through the quadriceps tendon move the patella in a lateral direction. The vastus medialis muscle counteracts the lateral motion, pulling the patella toward the midline. Problems with function of this joint usually result in anterior knee pain.

Idiopathic anterior knee pain is a common complaint in adolescents. It is particularly prevalent in adolescent female athletes. Previously, this was referred to as chondromalacia of the patella, but this term is incorrect as the joint surfaces of the patella are normal. It is now known as patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFS). The patient will present with anterior knee pain that worsens with activity, going up and down stairs, and soreness after sitting in one position for an extended time. There is usually no associated swelling. The patient may complain of a grinding sensation under the kneecap. Palpating and compressing the patellofemoral joint with the knee extended elicits pain. The patient may have weak hip musculature or poor flexibility in the lower extremities. Radiographs are rarely helpful but may be indicated to rule out other diagnoses such as osteochondritis dissecans.

Treatment is focused on correcting the biomechanical problems that are causing the pain. This is usually done using an exercise program emphasizing hip girdle and vastus medialis strengthening with lower extremity flexibility. Anti-inflammatory medication, ice, and activity modifications may also be helpful. Persistent cases should be referred to an orthopedist or sports medicine specialist.

One must exclude recurrent patellar subluxation and dislocation when evaluating a patient with PFS. Acute traumatic dislocation will usually cause significant disability and swelling. Recurrent episodes may not have the degree of swelling, loss of motion, and difficulty weight bearing seen in an initial dislocation. Patients with recurrent episodes often have associated ligamentous laxity, genu valgum, and femoral anteversion. The initial treatment is nonoperative and may involve a brief period of immobilization, followed by an aggressive physical therapy program designed to strengthen the quadriceps and improve function of the patellofemoral joint. Continued subluxation or dislocation is failure of this treatment plan and surgical repair is usually necessary.