CHAPTER 202 Spine

CHAPTER 202 Spine

SPINAL DEFORMITIES

A simplified classification of the common spinal abnormalities, scoliosis and kyphosis, is presented in Table 202-1.

TABLE 202-1 Classification of Spinal Deformities

SCOLIOSIS

KYPHOSIS

Adapted from the Terminology Committee of the Scoliosis Research Society, 1975.

Clinical Manifestations

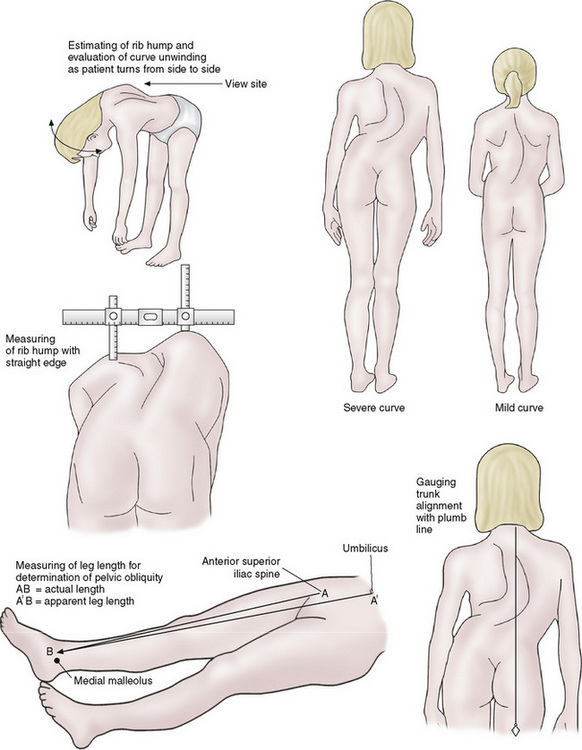

Most patients will present for evaluation of an asymmetrical spine, which is usually pain free. A complete physical examination is necessary for any patient with a spinal deformity, because the deformity can indicate an underlying disease. The back is examined from behind (Fig. 202-1). First the levelness of the pelvis is assessed. Leg-length discrepancy produces pelvic obliquity, which often results in compensatory scoliosis. When the pelvis is level, the spine is examined for symmetry and spinal curvature with the patient upright. Cutaneous lesions (hemangioma, skin dimple, or hair tuft) should be noted. The spine should be palpated for areas of tenderness.

The patient is then asked to bend forward with the hands directed between the feet (Adams forward bend test). The examiner should inspect for asymmetry in the spine. The presence of the hump in this position is the hallmark for scoliosis. The area opposite the hump is usually depressed, which is due to spinal rotation. Scoliosis is a rotational malalignment of one vertebra on another, resulting in rib elevation in the thoracic spine and paravertebral muscle elevation in the lumbar spine. With the patient still in the forward flexed position, inspection from the side can reveal the degree of roundback. A sharp forward angulation in the thoracolumbar region indicates a kyphotic deformity. It is important to examine the skin for café au lait spots (neurofibromatosis), hairy patches, and nevi (spinal dysraphism). Abnormal extremities may indicate skeletal dysplasia, whereas heart murmurs can be associated with Marfan syndrome. It is essential to do a full neurologic examination to determine whether the scoliosis is idiopathic or secondary to an underlying neuromuscular disease, and to assess whether the scoliosis is producing any neurologic sequelae.

Radiologic Evaluation

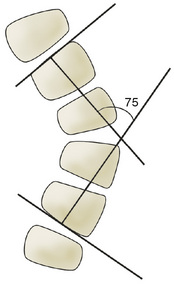

Initial radiographs should include a posteroanterior and lateral standing film of the entire spine. The iliac crests should be visible to help determine skeletal maturity. The degree of curvature is measured from the most tilted or end vertebra of the curve superiorly and inferiorly to determine the Cobb angle (Fig. 202-2).

FIGURE 202-2 Cobb method of scoliotic curve measurement. Determine which are the end vertebrae of the curve: They are at the upper and lower limits of the curve and tilt most severely toward the concavity of the curve. Draw two perpendicular lines, one from the bottom of the lower body and one from the top of the upper body. Measure the angle formed. This is the accepted method of curve measurement according to the Scoliosis Research Society. Curves of 0 to 20 degrees are mild; 20 to 40 degrees, moderate; and greater than 40 degrees, severe.

SCOLIOSIS

Alterations in normal spinal alignment that occur in the anteroposterior plane are termed scoliosis. Most scoliotic deformities are idiopathic. Scoliosis may also be congenital, neuromuscular, or compensatory from a leg-length discrepancy.

Idiopathic Scoliosis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Idiopathic scoliosis is the most common form of scoliosis. It occurs in healthy, neurologically normal children. Approximately 20% of patients have a positive family history. The incidence is slightly higher in girls than boys, and the condition is more likely to progress and require treatment in females. There is some evidence that progressive scoliosis may have a genetic component as well.

Idiopathic scoliosis can be classified in three categories: infantile (birth to 3 years), juvenile (4–10 years), and adolescent (>11 years). Idiopathic adolescent scoliosis is the most common cause (80%) of spinal deformity. The right thoracic curve is the most common pattern. Juvenile scoliosis is uncommon, but may be under-represented because many patients do not seek treatment until they are adolescents. In any patient younger than 11 years of age, there is a greater likelihood that their scoliosis is not idiopathic. The prevalence of an intraspinal abnormality in a child with congenital scoliosis is approximately 40%.

Clinical Manifestations

Idiopathic scoliosis is a painless disorder 70% of the time. A patient with pain requires a careful evaluation. Any patient presenting with a left-sided curve has a high incidence of intraspinal pathology (syrinx or tumor). Evaluation of the spine with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated in these cases.

Treatment

Treatment of idiopathic scoliosis is based on the skeletal maturity of the patient, the size of the curve, and whether the spinal curvature is progressive or nonprogressive. Initial treatment for scoliosis is likely observation and repeat radiographs to assess for progression. No treatment is indicated for nonprogressive deformities. The risk factors for curve progression include gender, curve location, and curve magnitude. Girls are five times more likely to progress than boys. Younger patients are more likely to progress than older patients.

Typically curves under 25 degrees are observed. Progressive curves between 20 and 50 degrees in a skeletally immature patient are treated with bracing. A radiograph in the orthotic is important to evaluate correction. Curves greater than 50 degrees usually require surgical intervention.

Congenital Scoliosis

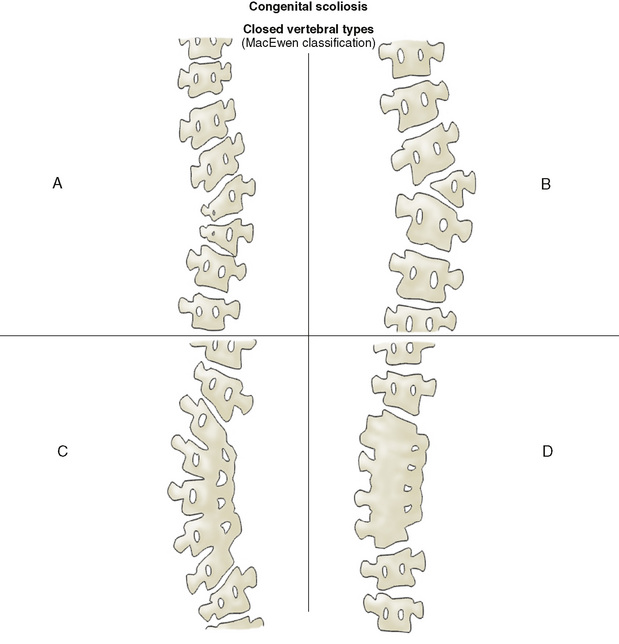

Abnormalities of the vertebral formation during the first trimester may lead to structural deformities of the spine that are evident at birth or early childhood. Congenital scoliosis can be classified as follows (Fig. 202-3):

FIGURE 202-3 Types of closed vertebral and extravertebral spinal anomalies that result in congenital scoliosis. A, Partial unilateral failure of formation (wedge vertebra). B, Complete unilateral failure of formation (hemivertebra). C, Unilateral failure of segmentation (congenital bar). D, Bilateral failure of segmentation (block vertebra).

Over 60% of patients have other associated abnormalities, such as VACTERL association (vertebral defects, imperforate anus, cardiac anomalies, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, limb abnormalities like radial agenesis) or Klippel-Feil syndrome. Renal anomalies occur in 20% of children with congenital scoliosis, with renal agenesis being the most common; 6% of children have a silent, obstructive uropathy suggesting the need for evaluation with ultrasonography. Congenital heart disease occurs in about 12% of patients. Spinal dysraphism (tethered cord, intradural lipoma, syringomyelia, diplomyelia, and diastematomyelia) occurs in approximately 20% of children with congenital scoliosis. These disorders are frequently associated with cutaneous lesions on the back and abnormalities of the legs and feet (e.g., cavus foot, neurologic changes, calf atrophy). MRI is indicated in evaluation of spinal dysraphism.

The risk of spinal deformity progression in congenital scoliosis is variable and depends on the growth potential of the malformed vertebrae. A unilateral unsegmented bar typically progresses, but a block vertebra has little growth potential. About 75% of patients with congenital scoliosis will show some progression that continues until skeletal growth is complete, and about 50% will require some type of treatment. Progression can be expected during periods of rapid growth (before 2 years and after 10 years).

Treatment of congenital scoliosis hinges on early diagnosis and identification of progressive curves. Orthotic treatment is not helpful in congenital scoliosis. Early spinal surgery should be performed once progression has been documented. This can help prevent major deformities. Patients with large curves that cause thoracic insufficiency should undergo surgery immediately.

Neuromuscular Scoliosis

Progressive spinal deformity is a common and potentially serious problem associated with many neuromuscular disorders, such as cerebral palsy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, and spina bifida. Spinal alignment must be part of the routine examination for a patient with neuromuscular disease. Once scoliosis begins, progression is usually continuous. The magnitude of the deformity depends on the severity and pattern of weakness, whether the underlying disease process is progressive and the amount of remaining musculoskeletal growth. Nonambulatory patients have a higher incidence of spinal deformity than ambulatory patients. In nonambulatory patients, the curves tend to be long and sweeping, produce pelvic obliquity, involve the cervical spine, and also produce restrictive lung disease. If the child cannot stand, then a supine anteroposterior radiograph of the entire spine, rather than a standing posteroanterior view, is indicated.

The goal of treatment is to prevent progression and loss of function. Nonambulatory patients are more comfortable and independent when they can sit in their wheelchair without external support. Progressive curves can impair sitting balance, which affects quality of life. Orthotic treatment is usually ineffective in neuromuscular scoliosis. Surgical intervention is necessary in most cases with frequent fusion to the pelvis.

Compensatory Scoliosis

Adolescents with a leg-length discrepancy (Chapter 200) may have a positive screening examination for scoliosis. When examining the patient before correcting the pelvic obliquity, the spine curves in the same direction of the obliquity. However, with identification and correction of their pelvic obliquity, the curvature should resolve, and treatment should be directed at the leg-length discrepancy. Thus, it is important to distinguish between a structural and compensatory spinal deformity.

KYPHOSIS

Kyphosis refers to a roundback deformity or to increased angulation of the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine in the sagittal plane. Kyphosis can be postural, structural (Scheuermann kyphosis), or congenital.

Postural Roundback

Postural kyphosis is secondary to poor posture. It is voluntarily corrected in the standing and prone positions. The patient may also have increased lumbar lordosis. Radiographs are usually unnecessary if the kyphosis fully corrects. If not, radiographs will reveal no vertebral abnormalities. Treatment, if needed, is aimed at improving the child’s posture.

Scheuermann Kyphosis

Scheuermann disease is the second most common cause of pediatric spinal deformity. It occurs equally in males and females. The etiology is unknown, but there may be hereditary factors. Scheuermann kyphosis is differentiated from postural roundback on physical examination and by radiographs.

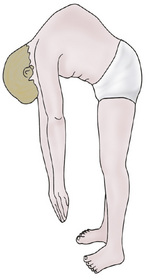

A patient with Scheuermann disease cannot correct the kyphosis with standing or lying prone. When viewed from the side in the forward flexed position, patients with Scheuermann disease will have an abrupt angulation in the mid to lower thoracic region (Fig. 202-4), and patients with postural roundback show a smooth, symmetrical contour. In both conditions, lumbar lordosis is increased. However, half of the patients with Scheuermann disease will have atypical back pain, especially with thoracolumbar kyphosis. The classic radiologic findings of Scheuermann kyphosis include the following:

FIGURE 202-4 Note the sharp break in the contour of a child with kyphosis.

(From Behrman RE: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 14th ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1992.)

Treatment of Scheuermann kyphosis is similar to idiopathic scoliosis. It is dependent on the degree of deformity, skeletal maturity, and the presence or absence of pain. Nonoperative treatment begins with bracing. Surgical fusion is done for patients who have completed growth, have a severe deformity, or who have intractable pain.

Congenital Kyphosis

Congenital kyphosis is a failure of the formation of all or part of the vertebral body (with preservation of posterior elements) or failure of anterior segmentation of the spine, or both. Severe deformities are found at birth and tend to progress rapidly. Progression will not cease until the end of skeletal growth. A progressive thoracic spine deformity may result in paraplegia. This complication is most often associated with failure of vertebral body formation. When indicated, treatment is often surgical.

TORTICOLLIS

Etiology and Epidemiology

Torticollis is usually first identified in newborns because of a head tilt. Torticollis is usually secondary to a shortened sternocleidomastoid muscle (muscular torticollis). This may result from in utero positioning or birth trauma. Acquired torticollis may be related to upper cervical spine abnormalities or central nervous system pathology (mass lesion). It can also occur in older children during a respiratory infection (potentially secondary to lymphadenitis) or local head or neck infection, and may herald psychiatric diagnoses.

Clinical Manifestations and Evaluation

Infants with muscular torticollis have the ear tilted toward the clavicle on the ipsilateral side. The face will look upward toward the contralateral side. There may be a palpable swelling or fibrosis in the body of the sternocleidomastoid shortly after birth, which is often the precursor of a contracture. Congenital muscular torticollis is associated with skull and facial asymmetry (plagiocephaly) and developmental dysplasia of the hip.

After a thorough neurologic examination, anteroposterior and lateral radiographs should be obtained. The goal is to rule out a nonmuscular etiology. A computed tomography (CT) scan or MRI of the head and neck is necessary for persistent neck pain, neurologic symptoms, and persistent deformity.

Treatment

Treatment of muscular torticollis is aimed at increasing the range of motion of the neck and correcting the cosmetic deformity. Stretching exercises of the neck can be very beneficial for infants. Surgical management is indicated if patients do not improve with adequate stretching exercises in physical therapy. Postoperative physical therapy is needed to decrease the risk of recurrence. Treatment in patients with underlying disorders should target the disorder.

BACK PAIN IN CHILDREN

Etiology and Epidemiology

Back pain in the pediatric population should always be approached with concern. In contrast to adults, in whom back pain is frequently mechanical or psychological, back pain in children may be the result of organic causes, especially in preadolescents. Back pain lasting longer than a week requires a detailed investigation. In the pediatric population, approximately 85% of children with back pain for greater than 2 months have a specific lesion: 33% are post-traumatic (spondylolysis, occult fracture), 33% developmental (kyphosis, scoliosis), and 18% have an infection or tumor. In the remaining 15%, the diagnosis is undetermined.

Clinical Manifestations and Management

The history must include the onset and duration of symptoms. The location, character, and radiation of pain are important. Neurologic symptoms (muscle weakness, sensory changes, and bowel or bladder dysfunction) must be reviewed. Past history and family history should be obtained, with a focus on back pain, rheumatologic disorders, and neoplastic processes. The review of systems should include detailed questions on overall health, fever, chills, recent weight loss, and recent illnesses. Physical examination should include a complete musculoskeletal and neurologic evaluation. Spinal alignment, range of motion, areas of tenderness, and muscle spasm should be noted. Red flags for childhood back pain include persistent or increasing pain, systemic findings (e.g., fever, weight loss), neurologic deficits, bowel or bladder dysfunction, young age (under 4 is strongly associated with tumor), night waking, pain that restricts activity, and a painful left thoracic spinal curvature.

Anteroposterior and lateral standing films of the entire spine with bilateral oblique views of the affected area should be obtained. Secondary imaging with bone scan, CT scan, or MRI may be necessary for diagnosis. MRI is very useful for suspected intraspinal pathology. Laboratory studies, such as a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and specialized testing for juvenile idiopathic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, may be indicated.

The differential diagnosis of pediatric back pain is extensive (Table 202-2). Treatment depends on the specific diagnosis. If serious pathology has been ruled out and no definite diagnosis has been established, an initial trial of physical therapy with close follow-up for reevaluation is recommended.

TABLE 202-2 Differential Diagnosis of Back Pain

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

RHEUMATOLOGIC DISEASES

DEVELOPMENTAL DISEASES

TRAUMATIC AND MECHANICAL ABNORMALITIES

NEOPLASTIC DISEASES

OTHER

SPONDYLOLYSIS AND SPONDYLOLITHESIS

Etiology and Epidemiology

Spondylolysis is a defect in the pars interarticularis. Spondylolithesis refers to bilateral defects with anterior slippage of the superior vertebra on the inferior vertebra. The lesions are not present at birth, but about 5% of children will have the lesion by 6 years of age. It is most common in adolescent athletes, especially those involved in sports that involve repetitive back extension. Classically, this was an injury seen in gymnasts and divers. However, with increased intensity and year-round sports, the incidence is increasing. Football interior lineman (extension while blocking), soccer players (extension while shooting), and basketball players (extension while rebounding) are examples of athletes at higher risk. The most common location of spondylolysis is L5, followed by L4.

Spondylolithesis is classified according to the degree of slippage:

Clinical Manifestations

Patients will often complain of an insidious onset of low back pain persisting over 2 weeks. The pain tends to worsen with activity and with extension of the back and improves with rest. There may be some radiation of pain to the buttocks. A loss of lumbar lordosis may occur due to muscular spasm. Pain is present with extension of lumbar spine and with palpation over the lesion. Patients with spondylolithesis may have a palpable step off at the lumbosacral area. A detailed neurologic examination should be done, especially because spondylolithesis can have nerve root involvement.

Radiologic Evaluation

Anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs of the spine should be obtained. The oblique views may show the classic Scotty dog findings associated with spondylolysis. The lateral view will allow measurement of spondylolithesis. Unfortunately, plain radiographs do not regularly reveal spondylolysis, so secondary imaging may be needed. A bone scan and CT scan can be helpful with diagnosis of spondylolysis. MRI may be required in patients with neurologic deficits.

Treatment

Spondylolysis

Painful spondylolysis requires activity restriction. Bracing is controversial but may help with pain relief. Patients benefit from an aggressive physical therapy plan to improve lower extremity flexibility and increase core strength and spinal stability. It is most beneficial to begin with flexion exercises and progress to extension exercises as tolerated. There is evidence that some patients with an acute spondylolysis can achieve bony union and that these patients have a decreased incidence of low back pain and degenerative change in the low back as they age when compared with spondylolysis patients with nonunion. Rarely, surgery is indicated for intractable pain and disability.

Spondylolithesis

Patients with spondylolithesis require periodic evaluation for progression of their slippage. Treatment of spondylolithesis is based on grading.

DISKITIS

Diskitis is an intervertebral disk space infection that does not cause associated vertebral osteomyelitis (see Chapter 117). The most common organism is Staphylococcus aureus. The infection can occur at any age but is more common in patients under 6 years of age.

Clinical Manifestations

Children may present with back pain, abdominal pain, pelvic pain, irritability, and refusal to walk. Fever is an inconsistent symptom. The child typically holds the spine in a straight or stiff position, generally has a loss of lumbar lordosis due to paravertebral muscular spasm, and refuses to flex the lumbar spine. The white blood cell count is normal or elevated, but the ESR is usually high.

Radiologic Evaluation

Radiographic findings vary according to the duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis. Anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs of the lumbar or thoracic spine will typically show a narrow disk space with irregularity of the adjacent vertebral body end plates. In early cases, bone scan or MRI may be helpful, because they will be positive before findings are noticeable on plain radiographs. MRI can also be used to differentiate between diskitis and the more serious condition of vertebral osteomyelitis.

Treatment

Intravenous antibiotic therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Blood cultures may occasionally be positive and identify the infectious agent. Aspiration and needle biopsy are reserved for children who are not responding to empirical antibiotic treatment. Symptoms should resolve rapidly with antibiotics, but intravenous antibiotics should be continued for 1 to 2 weeks, and be followed by 4 weeks of oral antibiotics. Pain control can be obtained with medications and temporary orthotic immobilization of the back.