Personal and Social Contexts of Disability

Implications for Occupational Therapists

Sandra E. Burnett*

Disability as a collective experience

Occupational therapy practice and the independent living philosophy

Interactional process: the person with a disability and the environment

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Describe the philosophy of the independent living movement and compare and contrast its view of the medical model and the social model of disability. Discuss implications of the philosophy of the independent living movement with occupational therapy practice.

2 Describe the personal context of the disability experience, noting the effect of individual differences, gender, type of disability, interests, beliefs, stage of life, and the usefulness of the stage models of disability adaptation.

3 Describe the social context of disability using the concepts of stigma, stereotypes, liminality, and spread. Discuss the effect on social context of person-first language, the culture of disability, and universal design principles.

4 Describe the ways the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) challenges mainstream ideas of health and disability.

5 Discuss various relationship issues between the occupational therapist and the person with a disability.

Occupational therapy (OT) has the overarching goal to promote independence and self-direction with those whose lives include the experience of disability. Since the early 1980s, the independent living movement has gained both scholarly and public support to promote the same end goal and has transformed models of disability, as well as the ways we think about disability. How the occupational therapy practitioners, as members of the healthcare and rehabilitation team, and independent living movement activists, composed primarily of leaders with disabilities, interact can lead to a marriage of commonly held goals or produce a battleground of cross purposes. This chapter describes the ways that occupational therapists (OTs) may approach a call for an accord with activists.

Social scientists, such as Irving Zola, who had both high academic, scholarly credentials and personal experience with physical disability, began an infusion of their work into the rehabilitation and social program literature in the early 1980s. Missing Pieces: A Chronicle of Living with a Disability91 and Ordinary Lives: Voices of Disability and Disease92 provide an insider’s discovery of the then unspoken social experience of disability that had been concealed in plain view. Zola’s field notes chronicle a discovery self-framed within the social status of the researcher having a physical disability that others could easily see. For many also drawn to the independent living movement, it was the proverbial elephant in the room, finally acknowledged in their professional lives.

The independent living movement, which achieved public recognition in the early 1970s, is a political social justice, civil rights challenge to prior disability policy, practice, and research.23 It is aligned with other minority groups (e.g., race, gender, ethnicity) in a call for equality in the dominant society, a civil rights movement, founded on the idea that the difficulties of having a disability are primarily based on the myths, fears, and stereotypes established in society today.70 This movement seeks to modify the convention of habilitating the isolated individual with disability through social and environmental changes.70 A major political achievement was passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) signed into federal law in 1990 and the enactment of the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 (see Chapters 2 and 15). This civil rights movement has had its share of detractors, including representatives of the healthcare industry, but sustained an expansive momentum.37

The social justice movement successfully entered the international arena on May 3, 2008, with the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). The CRPD obligates states to provide equal access to healthcare and related services for people with disabilities, and represents the first legally binding international instrument that specifically protects the rights of some 650 million such people worldwide. It is also the first treaty in which nongovernmental organizations were present during negotiations and could make interventions. People with disabilities participated as members of organizations of persons with disabilities, state delegations, and UN organizations. Partly because of this inclusive process, the CRPD has received wide support, with 143 states having signed and 71 states having ratified the instrument.

The core principles of the CRPD include respect for human dignity, nondiscrimination, full participation, social inclusion, equality of opportunity, and accessibility:76

• The relationship between occupation, justice, and client-centered practice is increasingly a focus of the OT profession.15

• Occupational therapy proclaims the necessity and power of occupation in the everyday lives of all human beings. The disruption and return of occupation for those with disability is our therapeutic focus. Health is supported and maintained when individuals are able to engage in their valued occupations. Occupation always occurs within the context of interrelated conditions that will affect client performance.3

The social and personal context of disability is inextricably linked when considering the lived experience of those with disability and ways to facilitate engagement in occupation. This chapter seeks to illuminate these contexts so that valued goals are achieved.

Client-Centered Self-Report

A justified complaint by those who have found their voice within the independent living movement is that medical and rehabilitation professionals focus on the attempt to classify an individual and do not listen to the personal account of the individual with the disability.42,59 The medical rehabilitation tradition of case presentation seeks to frame the individual with the disability in the professional’s point of view. There can be numerous goals for a “case” description: treatment justification, entitlement to support services, legal testimony as an expert witness, reimbursement of costs, social science research, educational process, and the like. The role of the occupational therapist is to work with the client to achieve an individual desired outcome.79 Occupational therapists are called to create a client-centered description of the individual’s occupational self, one that must include the interrelated conditions of the social and personal context both surrounding and within the client. We must include the personal view of his or her own context in order to frame an accurate occupational picture that is responsive to individual values and goals.

Personal Context

People who acquire disability share the common experience of feelings of shame and inferiority, along with avoidance of being identified as a person with disability.87

Neuroscience research, using state-of-the-art brain imaging, confirms what biologic, psychological, and sociologic studies and theory have posed; chiefly, that humans are social beings and a neurologic response at the most basic physiologic level is evident when conditions of social interaction are varied.2 In short, we are drawn toward interaction with “our kind,” and isolation from others may be deemed socially abnormal.

Community psychologists note that the individual forms an identity in relation to the social environment. In discussing those who deviate from societal-based norms, problems arise when individuals are assigned an identity and status that is demeaning and lacks elements of personal choice and human rights.63

A commonly experienced effect of having a disability is the social stigma associated with all individuals with a disability regardless of the condition.82 The psychological effects of being labeled a “disabled individual” is considered to be the process of devaluation. To be continuously perceived as an individual “blemished” in form or function is psychologically demeaning, regardless of the nature of the individual condition.82 The broadness of the term disabled imbues each individual with a disability with characteristics that are outside the norm.82

The individual with a disability must attend to an array of stimuli perceived as abnormal: some biologic, such as being paralyzed; some environmental, such as inaccessible entrances; and some social, such as the patronizing behavior of others or preferential access to an event. It is a continuous flow of perceptions, which are not experienced by those who are not disabled. In short, many of the experiences of an individual with a disability are not shared by the normative society. Isolation and a lack of accord with one’s thoughts and feelings compound the list of non-normative situations.82

In defining the experience of disability, social scientists82 and psychologists have constructed what can only be described as the psychology of disability. Of interest, however, is that by exploring the differences inherent in the social experience of the individual with a disability, the gap in perceived differences from the social norm may be widened by exaggerations. Thus, the devaluation of the individual with a disability may be perpetuated by those seeking to understand and even modify the conventional social perceptions. The fact is, human beings are more alike than different, regardless of variances in their physical bodies, sensory capacities, or intellectual abilities.14

It has been suggested that individuals with a disability shape their personal identities and social conception from their personal experiences through the modes of nonconformity and the outcomes of interactions with others in society. Specifically, if the individual considers his or her situation as nonconformative, it is due to the imposition of external societal factors and not a symptom of a condition.74 What is actually known about the similarities and differences between people with and people without disability? Siller reported that as soon as one departs from the direct fact of disability, evidence can be provided to demonstrate that persons with disabilities do or do not have different developmental tracks, social skills and precepts, defensive orientations, empathetic potential, and so on. The data suggest that if the disabled do present themselves as different, it is often a secondary consequence of the social climate rather than inherent disability-specific phenomena.74

Another study83 reported that a group of people with disability showed no differences in life satisfaction, frustration, or happiness, compared with a group without disability. The only difference found was on ratings of the difficulty of life. People with disability judged their lives to be more difficult and more likely to remain so. For example, people with chronic, but not fatal, health problems may not only seem to be quite happy but also may derive some happiness from their ability to cope with their difficulty. We may question the assumption that physical limitations are directly related to happiness. Instead, many people with disabilities may find happiness despite their disabilities, even though the able-bodied public may expect otherwise.

Individual Differences

Social scientists observe that an individual’s reactions to having disability are influenced not only by the time of onset, type of onset, functions impaired, severity and stability, visibility of disability, and the experiences of pain, but also by the person’s gender, activities affected, interests, values and goals, inner resources, personality and temperament, self-image, and environmental factors.82

Vash and Crewe believed that different disabilities (such as blindness or paralysis) generate different reactions because each creates different problems or challenges.82 However, the insider-outsider perspective also applies to people with disability. Thus, the person with disability may feel that his or her condition is not as difficult as that of others. For example, a person who is blind may feel that it would be worse to be deaf. This idea has also proven to hold for the severity of the individual condition. A person with the inability to walk may have the view that this disability is not nearly as difficult as someone without legs. Reactions are also tempered by the impact of the disability on the valued skills and capacities the person has lost. For example, a person who loves music more than the visual arts, such as photography, may have a stronger reaction to loss of hearing than a person who had a more dominant inclination with another sensory channel (e.g., a “visual person” with the opposite pattern). Similarly, the severity of disability may not have a direct, one-to-one relationship with the person’s reaction to it. (Note the use of the word may throughout this paragraph, indicating that reactions are individualized and unpredictable.)

The visibility or invisibility of impairment may influence a person’s response to his or her disability because of social reactions. For example, invisible disabilities such as pain may create difficulties because other people expect the person to perform in impossible ways. One woman with arthritis indicated that it was easier for her to go grocery shopping when she wore her hand splints because then her disability was visible and people would carry her packages for her without her having to ask.82

The stability of the disability or the extent to which it changes over time may influence reactions both for the individual with a disability and for those surrounding him or her. In some progressive disabilities the individual faces uncertainty as to the degree of limitations, as well as (in some cases) a hastened death. Reactions to such disabilities are shaped by these realities and by what the affected people tell themselves about their projected futures.82 When hope for neither containment nor cure is substantiated, the person may experience a new round of disappointment, fear, or anger. The prospect of a terminal condition can affect each person in individual ways. Some individuals may ignore even the experience of pain, which tends to overtake consciousness. Reactions to pain are highly influenced by culture. Particularly important for occupational therapists is the issue of finding and implementing resources to assist the client in developing effective and gratifying lifestyles. The activities and behavior patterns affected by an impairment become the focus of the OT. Core issues addressed by the OT must include the individual client’s spiritual or philosophic base (i.e., what makes the individual fulfilled).

Gender has also been found to elicit some of the most problematic issues for clients in their relationships with others. Gendered societal expectations dictate that individuals strive toward achieving, often idyllic, sexual roles. For example, the ideal for women to be physically perfect specimens or to carry the major responsibility for managing the home and caring for children may be of more concern for a female client than a male client.

Temporal elements of activity are part of the impact of disablement. The ways it interferes with what one is doing, with the interruption of ongoing activities, will influence the person’s reactions. Additionally, activities never done but imagined as future goals also may be equally powerful influences in the person’s reactions.

Interests, values, and goals influence a person’s reaction to his or her disablement. The individual with a limited range of interests may react more negatively to a disability that prevents his or her expression, whereas an individual with a wide range of interests and goals may adapt more readily. Many people may not even be aware of their own interests, values, and goals and, therefore, may not be conscious of the ones that have the potential to lead to satisfaction after acquiring a disability. Thus, the client with multiple interests, activities, and goals has a greater probability of attaining engagement in satisfying activities. The resources that the individual possesses for coping with and enjoying life are assets that may counterbalance the devastation of loss of function. Some of these, such as social skills and persistence, may be developed to a level enabling paid employment, whereas others, such as artistic talent or leisure skills, may contribute to a more satisfying life.82

An often overlooked aspect of the individual with a disability is the importance of spiritual and philosophic beliefs toward that person’s disablement. People who acknowledge a spiritual dimension of life and who have a philosophy of life into which disablement can be integrated in a meaningful, nondestructive way may be better able to deal with having a disability.82 Specific religious beliefs may or may not be helpful. The person who views having a disability as punishment for past sins will respond differently from one who views the disability as a test or opportunity for spiritual development.

Lastly, the OT must acknowledge the importance of the person’s environment in influencing his or her reactions to having disability. Immediate environmental qualities such as family support and acceptance, income, community resources, and loyal friends are powerful contributors. The institutional environment if one is hospitalized also has a profound effect, especially the attitudes and behaviors of the staff members. The culture and its support (or lack thereof) for resolving functional problems or protecting the civil rights of people with disability is another significant influence.

Stage Models of Adjustment to Disability

The medical model generally provides the medical rehabilitation team with a four-stage process of adjustment or adaptation to the experience of disability (Box 6-1).56

Evidence only exists for emotional distress, commonly experienced as an initial response, and that it tends to diminish over time, but even that is not universal. Rehabilitation researchers are turning to a far more complex process of involving changes in the body, body image, self-concept, and the interactions between the person and the environment. For example, little attention has been given to individual personality differences (i.e., personal context), well recognized as contributors to all human endeavors (e.g., work, marriage, play, education, and occupations) expressed in an environment. Rather, the disability has been seen as the sole determinant of the individual personal experience.

The terms adaptation, adjustment, and acceptance are commonly applied to the process of resolving the negative experiences of having a disability. In recent years, social scientists aligned with the social model of disability have questioned the usefulness of such terms. They point out the preoccupation by service professionals with the psychological loss, or stages of bereavement, process to describe appropriate adjustment by those with an impairment. The studies usually cited, which contain a four-stage process of psychological adjustment and rehabilitation applied to those with spinal cord injury, are troublesome for the social model scientists.8 That process is usually thus: the initial reaction of shock and horror is followed by denial of the situation, leading to anger at others, bargaining, and finally to depression as a necessity for coming to terms with the acquired impairment. The acceptance, or adjustment, process takes one to two years to resolve.8 The process draws from Kübler-Ross’s seminal work describing the grief process, stages of loss of those who are dying, with an implicit assumption that the former, nondisabled self is dead and must be mourned.44

The social model views the notion of adaptation, adjustment, or acceptance with an unjust society as abhorrent at the most basic level of human rights and social justice. Other minority groups have not tolerated such treatment within democratic societies, and disability rights activists believe that those with disabilities should not either. They point to a major flaw in these stage models: what about the physical condition that is progressive in nature (such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, etc.) or limiting, physical changes as the body ages associated with lifelong disorders, such as spina bifida, or early in life trauma, such as spinal cord injury, or post-polio? The stages-of-loss concept common with the medical model gives little to community-based occupational therapy in which the issues of chronic or progressive disability-related problems are more typically addressed. One might speculate that the stage-of-loss concept, at best, suits the emotional needs of clinicians to have a sense of closure and resolution as patients move out of acute medical rehabilitation.

There has always been tension between the medical model of disability, which emphasizes an individual’s physical or mental deficit, and the social model of disability, which highlights the barriers and prejudice that exclude people with disabilities from fully engaging in society and accessing appropriate healthcare (see Chapter 2). Unfortunately, one of the biggest barriers to accessing appropriate healthcare is the attitude of health professionals, which might further isolate and stigmatize people with disabilities. Despite what many health professionals might assume, people with disabilities can be healthy, do not necessarily need to be “fixed,” are often independent, and might well be consulting for a reason unrelated to their disability. Conversely, people with chronic conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, are often debilitated by their condition yet are often not perceived by health professionals as having a disability. Such perceptions matter: people with disabilities still have the same health needs as other people and are entitled to specific rights, including the right to make choices about their healthcare.88

In contrast, bioethicist Singer has posed that healthcare rationing decisions should be quantified by using a quality-adjusted life-year, or QALY, which might assess the relative value of life with a disability to a nondisabled one,73 which is in stark contrast to a social justice model, with each individual possessing equal value.

Stages of Life and Self-Concept

Many views of the individual and groups of people divide the human life cycle into three categories: childhood, adulthood, and the elderly. Its stages, statuses, and transitions are constructed in large by social institutions (i.e., the family, economic demands, and education) and the dominant culture. One might expect that by identifying the onset of a physical impairment in the life cycle, one may know the trajectory of many factors including self-concept. The stage of life at which disability occurs is thought to influence the person because it affects the way he or she is perceived by others and the developmental tasks that might be interrupted. In that vein, the three main trajectories commonly identified are as follows: (1) people whose impairment is diagnosed at birth or in early childhood, (2) those who acquire an impairment during the adolescent or early adult years, usually through illness or injury, and (3) older people whose impairment is most often attributed to the aging process.8

The person who is born with disability or acquires disability in infancy or childhood may experience isolation or separation from the mainstream in family life, play, and education. The trajectory of an early onset disability is thought to include socialization with pervasively abnormal low expectations, and lifestyle, with few positive role models to exhibit alternative models. Families and special-needs schools may hide children with congenital impairments in order to protect them from discrimination and rejection from bullying peers. A “disabled identity” results from the child with a disability, growing up in a household and community with no other disabled person, lengthy periods of hospitalization, segregated special education, or a largely inaccessible physical environment.8

A 2003 study of self-image of a group of Swedish young persons with cerebral palsy revealed that most respondents viewed themselves in a very positive manner and rated markedly higher self-image than norm groups.1 The influence of a generally positive or negative attitude toward oneself formed early in life and the sparse interaction with others outside of the family are posed as explanations of the research findings. Future studies must focus on the relationship between self-image and the social interaction with persons outside the immediate family as the individual with an impairment begins to interact with a wider social group.

Barnes and Mercer have concluded that many youth with disabilities do not experience the full impact of disablement until they seek to participate in more peer-directed leisure pursuits or are expected to join the workforce. When young people with disabilities are compared with nondisabled peers, they report lower job aspirations, poor or nonexistent career advice, employer discrimination, and a feeling of marginalization in the job market. There is evidence that the age of key major life transition indicators—such as leaving home, getting married, becoming a parent, and entry into the job market—occurs later among those with disabilities compared with those without disabilities.8

One cannot assume there will be continuing negative effects on self-esteem if there is an early onset disability. A longitudinal study found that although adolescent girls with cerebral palsy scored significantly lower on physical, social, and personal self-esteem evaluations, as adults the same individuals no longer scored significantly different from able-bodied groups.53 The authors speculated that factors in their subjects’ changed self-esteem may have been due to an expanded range of environments in which to interact, better social relationships, or a wider variety of experiences in education, work, and commerce (than in earlier years).

A study of self-evaluations of global self-worth in adolescents with disability (e.g., cerebral palsy, orofacial clefts, and spina bifida) found that the participants did not differ from those of an able-bodied comparison group (the assumption that self-esteem is necessarily reduced by a disability effect needs to be reassessed in light of recent studies).43

A person who acquires disability later in life may face different issues, such as the need to change vocations, find a marital partner, or remain a part of his or her culture via the routines of daily life.11,82 Some are forced into a sudden and substantial reevaluation of their identities, perhaps reinforced within a short time period by downward economic and social mobility. A distinction can be made between those who experience discontinuity with a sharp shift into unemployment, contrasted with the drift of a more gradual process of downward mobility. Generally, a chronic illness is less drastic than an accident resulting in disability, affording the individual the opportunity to plan and adjust to threats to self-identity.8

It has been posed that individuals who acquire an impairment in middle age may, more often than those who are aged, view the onset of a disability as an unexpected, personal tragedy. In comparison, those who are aged, and those who surround them, both family and service providers, may interpret the disability experience as an inevitable fact of life and, therefore, more of a normal course of events.8

Social scientists are calling for research on those with disabilities that includes much more descriptive factors such as the visibility of the impairment, the distinct type of impairment, whether the impairment was preventable, the age of onset, the influence of public perception on the individual, and social interactions. Increasingly, many persons who have disabilities from various backgrounds are learning to think about disability as a social justice issue rather than as a category of individual deficiency. Some surveys have indicated that disabled Americans who are young enough to have been influenced by the disability rights movement are more likely than older counterparts to identify themselves as members of a minority group, namely, the disability community.31

Gill has called for “deindividualizing the problem of disability,”31 contrasting this view with seeing disability as a personal tragedy. In understanding the social determinants of the devalued status by challenging the disabling society, one reinforces the valid and whole feelings held by those who are disabled. Plainly stated, if the individual with a disability views personal experience as a problem highly influenced by factors outside of oneself, this perspective provides a way to effectively challenge societal perceptions of a devalued status.

Individuals with disabilities often demonstrate remarkable strength and achievement in the face of environmental obstacles and social exclusion. Those seeking to truly understand the disability experience should consider the aspects of the disability identity that engender creativity and an enhanced awareness of many commonly unappreciated aspects of human experience.31

Understanding Individual Experience

To avoid turning a category such as disability into an inflexible framework for identity, occupational therapists must develop methods that elicit the personal experiences and opinions of those who are disabled.1 The narrative process for discovery of the individual is a recommended method. The process relies less on observable behavior and more on how people use their own stories to gain an understanding of everyday experience and emotion. It allows us to analyze the ways that personal identity is shaped by social interaction while maintaining the individual studied as an active agent.8

Part of a therapy program for clients with a disability should include client-centered exploration into the individual perspective. Initially, to help better define the client perspective, research has shown that discussing the meaning of core categories can lead to insight about the feelings and attitudes of the client.24 Examples of core meaning categories have included (but are not restricted to) illness, independence, activity, altruism, self-caring, and self-respect. Researchers demonstrated that the independence, activity, and altruism categories actively directed behavior before and during treatment, and that the last two meanings emerged as treatment progressed as a transformation process. Explanation of the categories identified should be a part of the rehabilitation intervention, with both therapists and clients benefiting from the increased awareness and self-reflection of the individual clients.

One study employed this phenomenological approach to describe the lived experience of disability of a woman who sustained a head injury 21 years before.59 The woman identified themes of nostalgia, abandonment, and hope and what the core categories meant to her. More important than simply defining these terms, she reflected on how these meanings had shaped her life experiences for those 21 years. The outcome for this individual focused on changing her perspective from that of a passive victim to an active constructor of her own identity.8 Revaluating these themes with the individual may allow both the therapist and the client to discover the unique disability experience.

Social Context

The historical Chicago city ordinance recorded in Box 6-2 is an example of the segregation and discrimination society has openly communicated to those with disabilities. A more extreme example is the extermination of 200,000 people with disabilities in the death camps of the Nazi regime in World War II. Our 21st century perspective may scoff and feel distanced from such obvious prejudice. These may seem to be events consigned to another place, another time. To see our own present-day society behaving somewhere along the continuum that still includes discrimination and injustice is difficult. This is an inquiry we must not shy away from; the cost to our professional integrity would be too high without it; and, our ability to provide a useful service would be compromised without such an understanding.

Goffman’s classic work32 used the term stigma to describe the social discrediting process in strained relations between disabled and nondisabled people31 that reduces the life chances of people with disability or other differences. In the process, an obvious impairment or knowledge of a hidden one signifies a moral deficiency. The individual with stigma is seen as not quite human. Society tends to impute a wide range of imperfections on the basis of the impairment.

As with individuals from other minority groups, those with disabilities are categorized with stereotypes. The standard definition of a stereotype is an unvarying form or pattern, a fixed notion, having no individuality, as though cast from a mold.84 Stereotyping is part of the stigmatization process, applied to those perceived to exhibit certain qualities. Stigma may be expressed as a societal reaction to fear of the unknown. One explanation for stereotypes applied to those with disabilities is that little direct experience, despite recent mainstreaming in education and the removal of some environmental barriers, produces little real knowledge of what to expect in daily life.

Individuals with visible disabilities may be discredited in social situations, without regard for their actual abilities. “The exclusion of persons with physical disabilities from educational settings and work situations regardless of their ability to participate in and perform all required activities is well recorded in the literature.”69

Several researchers have noted the popular media portrayals of those with disabilities, forming and reinforcing the basis of our common stereotypes, even for those of us in health professions59 (Box 6-3). For example, “Films present people with disabilities either condescendingly as ‘inspirational,’ endeavoring to be as ‘normal’ as possible by ‘overcoming’ their limitations, or as disfigured monsters ‘slashing and hacking their way to box office success.’ ”27 Cahill and Norden,18 in their discussion of such stereotypic characterization of women with disabilities in the media, found the two most frequent categories of portrayal: the disabled ingénue victim and the awe-inspiring overachiever. The disabled ingénue is young and pretty but significantly helpless because of her disability. The ingénue may be victimized or terrorized by others. Usually she is cured of her malady and able to return to the mainstream by the end of the story. Her return, or “reabsorption,” often produces an ability to have a new perspective on life. Similarly, the awe-inspiring overachiever is attractive and succeeds in reaching extraordinary levels of competitive acclaim only to be taken down by an incurable disability. She eventually “overcomes” her disability with unrelenting personal fortitude, and often unexplained economic resources.18

The traditional approach used in telethons or other fund-raising ventures, in which people with disabilities may be portrayed as victims, reinforces our negative attitudes, stereotypes, and stigma. More recently, with pressure from disability advocacy groups, some network television programs and commercials include people with disabilities as regular participants in daily life, as workers or family members.

Disability as a Collective Experience

Vash and Crewe recounted a rehabilitation conference a number of years ago when an address by a psychiatrist included the speaker alternatively standing up and then sitting back down in a wheelchair several times.82 The speaker challenged the audience to deny that their sense of his competence changed as he stood before them or sat in the wheelchair. Vash reported that when discussion followed, most acknowledged that their perception of his competence fluctuated; the speaker was more credible and worth attention when he was standing. The demonstration forced them to acknowledge their own, previously denied, prejudice and was emotionally charged for much of the audience. A wheelchair can be a powerful social symbol, conveying devaluation of the person in it.

Zola91 observed that, at its worst, society denigrates, stigmatizes, and distances itself from people with chronic conditions. He experienced little encouragement to integrate his disability identity into his life because this would be interpreted as foregoing the fight to be normal. In letting his disability surface as a real and not necessarily bad part of himself, he was able to shed his super strong “I can do it myself” attitudes and be more demanding for what he needed. Only later did he come to believe that he had the right to ask for or demand certain accommodations. He began to refuse invitations for speaking engagements unless they were held in a fully accessible facility (not only for him as the speaker, but also for the audience).

Another insider’s view of disability is provided by Robert Murphy,57 an anthropologist who developed a progressive spinal cord tumor that ultimately led to quadriplegia. His account particularly captures the medical and rehabilitation setting from the perspective of the client. He described his initial reaction: “But what depressed me above all else was the realization that I had lost my freedom, that I was to be an occasional prisoner of hospitals for some time to come, that my future was under the control of the medical establishment.”57 He reported the feeling as like falling into a vast web, a trap from which he might never escape.

The hospitalized individual must conform to the routine imposed by the medical establishment. For example, Murphy spent 5 weeks on one ward where he was bathed at 5:30 every morning because the day shift nurses were too busy to do it. The chain of authority from physicians on down creates a bureaucratic structure that breeds and feeds on impersonality.57 The totality (of social isolation) of such institutions is greater in long-term care facilities, such as mental health and rehabilitation centers. A closed-off, total institution generally attempts to erase prior identity and make the person assume a new one, imposed by authority. The hospital requires that the “inmates” think of themselves primarily as patients, a condition of conformity and subservience.

Murphy highlighted the experience of an increased social isolation as some of his friends avoided him.57 He often encountered physical barriers in his environment, which restricted opportunities for social contact. He applied a term from anthropology, liminality, to the observation that people with disability have the social experience of pervasive exclusion from ordinary life, the denial of full humanity, an indeterminate limbo-like state of being in the world, in other words, the marginal status of individuals who have not yet passed a test of full societal membership. Those with such social status have a kind of invisibility; as their bodies are impaired, so is their social standing. “Caught in a transitional state between isolation and social emergence” people with disabilities “do not count as proven citizens of the culture.”31 This limbo-like state affects all social interaction. “Their persons are regarded as contaminated; eyes are averted and people take care not to approach wheelchairs too closely.”31 One of his colleagues viewed wheelchairs as portable seclusion huts or isolation chambers.

Murphy was surprised to discover that in attending meetings of organizations formed by people with disability, often more attention was paid to the opinions of experts who were able bodied than to his views, in spite of his having disability and being a professor of anthropology.57 Those with disabilities may hold the same social attitudes from the culture about disability and behave in ways consistent with those negative views.

A major aspect of Murphy’s life was his work as a professor, which he continued as long as possible. But even with his status as an internationally recognized anthropologist and researcher, hospital personnel often saw him as an anomaly. A hospital social worker asked him, “What was your occupation?” even though he was working full time and doing research in areas related to medical expertise. With their mindset, hospital workers seemed unable to place him in the mainstream of society. Murphy concluded that people with disability must make extra efforts to establish themselves as autonomous, worthy individuals.57

In certain ways, many disabled persons are forced to lead dual lives. First, they are repeatedly mistaken for something they are not: tragic, heroic, pathetic, not full humans. Persons with a wide range of impairments report extensive experience with such identity misattributions. Second, disabled people must submerge their spontaneous reactions and authentic feelings to smooth over relations with others, from strangers to family members to the personal assistants they rely on to maneuver through each day.31

Murphy’s book ended with this observation: “But the essence of the well-lived life is the defiance of negativity, inertia and death. Life has a liturgy which must be constantly celebrated and renewed; it is a feast whose sacrament is consummated in the paralytic’s breaking out from his prison of flesh and bone, and in his quest for autonomy.”57

Wright, a social psychologist, studied and wrote about society’s reactions to people with disability for many years.87 She used the term spread to describe how the presence of disability or an atypical physique serves as a stimulus to inferences, assumptions, or expectations about the person who has disability. For example, a person who is blind may be shouted at, as though lack of vision indicates impaired hearing as well, or a person with cerebral palsy and a speech impairment may be assumed to be mentally retarded. One extreme manifestation of spread is the belief that an individual’s life must be a tragedy because of having a disability. This attitude may be expressed in such statements as “I would rather be dead than have multiple sclerosis.” The assumption that the presence of a disabling condition is a life sentence to a tragic existence denies that satisfaction and happiness may ever be achieved. This attitude is of particular ethical concern today, when genetic counseling and euthanasia may provide a socially acceptable means of exterminating people with disability.80 If life is seen as tragic or not worth living, it is a fairly easy step to argue that it would be better for everyone if people with disability ceased to exist.62

Wright’s work describing efforts to integrate disability with a positive sense of self has explicit recognition that the devalued status of those with disability is imposed on such persons collectively.31 Gill pointed out that individuals with disabilities make assessments (of asset values in comparison with comparative-status values) in terms of contributions to one’s life. She used the example of the skill in using adaptive equipment; although others may judge the use of such devices as inferior (compared with “normal” functioning), persons with disabilities regard them as assets because they have learned to appreciate the benefit derived from their use.31

Occupational Therapy Practice and the Independent Living Philosophy

Until recently, much of the emphasis in rehabilitation has been on modifying the individual to adapt to the existing environment. Individuals have been modified by machines, surgery, physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychotherapy, vocational counseling, social work, prosthetic and orthotic devices, education, training and so on.82 This emphasis on modification of the person is termed the medical model (or biomedical model) of intervention. It is based on the thought that there must be intervention, treatment, repair or correction of pathology, of that which is a deviation from the norm. The norm may be physiologic, anatomic, behavioral, or functional. The cause of problem, in this model, is intrinsic to the person; normalization is the goal. In contrast, these normalization models are considered erroneous and dangerous by those aligned with the independent living philosophy, the social model of disability. Of particular concern is the tendency to isolate specific differences and then use those differences to determine and explain the consequences at a societal level.28 This tendency creates a kind of logical fallacy, in which the evidence for what is normal is then used to explain the resultant problems that prevent participation in society.

In his landmark article first published in 1979, DeJong described the differences between the medical rehabilitation model and the independent living model, and its sister, the social model of disability.23 In the medical model, the physician is the primary decision maker, and healthcare professionals are considered the experts. The problem is defined as the patient’s impairment or disease; the solution lies in the services delivered by the healthcare professionals. Oftentimes, the goal of rehabilitation is for the patient to be independent in activities of daily living (ADLs) performance. The client is expected to participate willingly in the program established by the healthcare professionals, and success is determined by the patient’s compliance with the prescribed program and attainment of goals established by the medical rehabilitation team.14

Fleischer and Zames27 pointed out that with the emergence of those with severe disabilities from secluded institutions in combination with independent living, strategies that produced participation in the community, a critical force gained momentum, creating the disability rights movement. Previously, many who became prime movers in the fledgling civil rights struggle for people with disabilities might have been hidden away in segregated institutions or become homebound. Edward Roberts, father of the worldwide independent living movement, had to sleep in an iron lung. Both Judith E. Heumann, the former assistant secretary of education and founder of Disabled in Action, and Roberts, of the World Institute on Disability, require attendant care for activities of daily living. In the 1990s, it was reported that Fred Fay, cofounder of the Center for Independent Living and the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities, would lie on his back all day, every day, managing not only his home but also state and national political campaigns and international disability advocacy programs using a combination of personal assistance and three computers.14

Bowen pointed out that occupational therapy practitioners should not deceive themselves into believing they are using an independent living, or social, model because the professional role is to help people live independently.3–5 This is merely a simple shift of words, not the core of the model. The independent living movement and the associated model are quite different and separate approaches to practice from the traditional medical model used by most practitioners.14

When the independent living model is used, the person receiving services is considered a consumer, not a patient; is the expert who knows his or her own needs; and is the one who should be the primary decision maker. In this model, the healthcare service provider describes what he or she can do with the consumer, and the consumer then decides what aspects of the service he or she wants to use. The foremost issues addressed are the inaccessible environment, negative attitudes held by others about disabilities, and the medical rehabilitation process, which tends to produce dependence on others. These problems are best resolved through self-help and consumer control of decision making, self-advocacy, peer counseling, and removal of attitudinal and architectural barriers. The goal of independent living is full participation and integration into the entire society.14

Consumer-controlled and consumer-directed independent living programs offering a broad spectrum of services, including some that occupational therapy practitioners have considered hallmarks of the profession, such as assistive device recommendation and daily living skills training, are funded through federal, state, local, and private resources. In 1993, the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) published a position paper outlining the role of occupational therapy in such programs. The general practice of the professional per se does not differ from other settings. The major difference is that the consumer selects which services to use, rather than receiving those chosen by the therapist. With the community-based nature of the settings, as contrasted with healthcare facility-based settings, the services are directly related to the consumer’s ability to function within his or her roles in the local community. The practitioner may need a higher level of creativity to address the diverse role-related functional activities.

Bowen stated that practitioners often fall short in implementation of an independent living philosophy, namely, striving to make others aware of the handicapping nature of the environment. The focused goal, using the independent living philosophy, is on problems that reside in the physical and social environment, not on a deficit within the person with a disability. Research noted that practitioners write therapeutic goals that seek to change the client 12 times more often than goals that focus on altering the environment.14 Other occupational therapy researchers reported an extreme lack of practitioners’ knowledge related to architectural accessibility regulations that, thereby, compromised their ability to promote integration into the community and empower consumers who use wheelchairs.64

Person-First Language

The language used to communicate ideas about people with disability is important because it conveys images about the people that may diminish their status as human beings. Kailes, a disability policy consultant who has a lifelong disability, wrote, “Language is powerful. It structures our reality and influences our attitudes and behavior. Words can empower, encourage, confuse, discriminate, patronize, denigrate, inflame, start wars and bring about peace. Words can elicit love and manifest hate, and words can paint vivid and long lasting pictures.”38 For example, in the jargon of the medical environment, disabled people may be called “quads,” “paras,” “CPs” or “that stroke down the hall.” Such categorization leads to viewing individuals as stereotypic examples, engulfed by their impairments.13 Some individuals are of the opinion that referring to people as “the disabled” or “a disabled person” makes the disability swallow up their entire identity, leaving them outside the mainstream of humanity. How, then, might occupational therapy practitioners use language in a spirit of dignity?

Switzer noted in her discussion of the complexities of disability policy that there is

virtually universal agreement that pejorative terms that objectify disabled persons (such as deformed or wheel-chair bound) diminish the importance of the individual and create the perception of people only in terms of their disability. Similarly, attempts to develop euphemisms (physically challenged, height-impaired) generally are thought to be misguided attempts that still identify persons by their disability alone.77

For persons with disabilities (PWDs) to develop a sense of pride, culture, and community, past negative attitudes must be changed. The use of language that recognizes that the person comes first, namely, a person with a disability, is yet again another acknowledgment that the individual is a human being before being someone with a disability.77 This shift in use of language is widely known as person-first language.47

All struggles for basic human rights have included the significant issue of what labels will be used by and about a particular people. With other minority groups, examples include the following: “Negro” was replaced by “black” and then changed to “African American”; “Indian” changed to “Native American” or “People of First Nations”; and “ladies” or “girls” are now more commonly called “women.” Kailes has reminded us that terms such as crippled, disabled, and handicapped are labels imposed from outside the community of people with disabilities, from definitions constructed by social services, medical institutions, governments, and employers. The preferred terms continue to evolve and change. Negative attitudes, values, biases, and stereotypes can be amended by using disability-related language that is precise, objective, and neutral. Disability-related terms are often subjective and indirectly carry a feeling or bias through innuendo and tone. But the effect of these terms on those with disabilities can be very direct and disturbing with a sharp cringe, a flash of anger, or shutting down the interaction when confronted with “ablest” and “handicapist” language. Use of such language creates social distance, establishes an inequality in the interaction, and produces demeaning expectations.38

What should we call the recipient of occupational therapy—patient, client, or patient-client (Box 6-4). Patient conveys both a sense of ethical responsibility66 by practitioners, as well as passivity and dependence57 for those people receiving care. Client, on the other hand, conveys merely an economic relationship,71 as does consumer. One might sell a product or service to a client with the buyer beware ethic of a free market economy, whereas our professional ethics demand the provision of service based entirely on the benefits it affords its recipients. Perhaps a sensitive inquiry by the therapist is needed, asking what term that particular individual prefers might give the answer.

Culture of Disability

Shapiro, a highly regarded journalist, wrote about the new group consciousness emerging through a powerful coalition of literally millions of people with disabilities, their families, and those working with them. He noted the start of a disability culture, which did not exist nationally even as recently as the late 1970s.70 Barnes and Mercer,9 British social scientists, more recently stated that the disability culture is a sense of common identity and interests that unites disabled people and separates them from those who are non-disabled.

As Steven Brown, cofounder of the Institute on Disability Culture in Las Cruces, New Mexico, said:

People with disabilities have forged a group identity. We share a common history of oppression and a common bond of resilience. We generate art, music, literature, and other expressions of our lives and our culture, infused from our experience of disability. Most importantly, we are proud of ourselves as people with disabilities. We claim our disabilities with pride as part of our identity. We are who we are: we are people with disabilities.27

The notion of “disability pride,” as an echo of “black pride” or “gay pride,” was dismissed as unachievable even within independent living movement circles during the mid-1970s. In the summer of 2004, however, was the first Disability Pride Parade in Chicago. Sarah Triano, Disabilities Pride Parade Planning co-chair, said, “It takes a lot for people with disabilities, particularly non-apparent disabilities, to get to a place where they openly and proudly identify themselves as disabled. Just as in other social/human rights movements, the first arena of acceptance comes from the internalized feelings of pride and power.” She went on to say, “It’s time that we reclaim the definition of Disability and take control over the naming of our own experience … disability is a natural and beautiful part of human diversity … The barrier to be overcome is not my disability; it is societal oppression and discrimination based on biologic differences (such as disability, gender, race, age, or sexuality)” (www.disabledandproud.com/selfdefinition.htm).

The emergence of the disability arts movement marks a significant stage in the transition to positive portrayal of disabled people building on the social model of disability. From the mid-1980s, there has been a substantial increase in work by disabled poets, musicians, artists, and entertainers that articulates the experience and value of the “disabled” lifestyle.9 Art, literature, and performance, from the time of Shakespeare to the present day Axis Dance Company, aspire to convey the universality of human experience that we all share. For more than 20 years, the late John Callahan, an irreverent cartoonist and self-stated “quadriplegic in a wheelchair” depicted a point of view of life, including the experience of disability, which was published in newspapers across the nation.55 Callahan’s autobiography, Don’t Worry He Won’t Get Far on Foot, made it to the New York Times bestseller list.

“Disdainful of pity, disability culture celebrates its heritage and sense of community, using various forms of expression common to other cultures such as, for example, film, literature, dance, and painting.”27 The UCLA National Arts and Disability Center is dedicated to promoting the full inclusion of children and adults with disabilities into the visual-, performing-, media-, and literary-arts communities. Beyond Victims and Villains: Contemporary Plays by Disabled Playwrights49 and Bodies in Commotion: Disability and Performance67 are well-regarded examples.

Sports and games, heralds of cultural pursuit, are also evident in the culture of disability. The term disabled athlete has been reclaimed from sports medicine and orthopedics to mean competitive athletes with disabilities. Every major city marathon includes “runners” with wheels. The international Paralympics occur every four years in tandem with the Olympic Games, with 4000 entrants from 130 countries (www.paralympic.org). The 2005 film Murderball,36 about athletes with paraplegia who play full-contact rugby in Mad Max–style wheelchairs and who competed in the Paralympic Games in Athens, Greece, was nominated for an Oscar from the Academy of Motion Pictures (IMDb, Inc., www.imdb.com/title/tt0436613). In another example, professional wheelchair skaters are showcased at skate parks.26

Charlton’s Nothing about Us without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment details the worldwide “grassroots disability activism” of those with disabilities. He stated, “A consciousness of empowerment is growing among people with disabilities … it has to do with being proud of self and having a culture that fortifies and spreads the feeling.”19

The well-known journalist and author of Moving Violations, A Memoir: War Zones, Wheelchairs, and Declarations of Independence,35 John Hockenberry, who had a spinal cord injury and uses a wheelchair, sees disability in a novel way, as a cultural resource, and is quoted as follows:

Why is it that a person would not be considered educated or privileged if he went to school and never learned there was a France or a French language? But if a person went through school and knew nothing about disability, never met a disabled person, never heard of American Sign Language, he might be considered not only educated, but also lucky? Maybe we in the disability community need to get out of the clinical realm, even out of the equity realm, into the cultural realm, and show that a strategy that leads to inclusion makes a better community for everyone.35

Murphy, in The Body Silent,57 described how his degenerative disability impelled him to examine the society of people with disabilities with the same analytic tools he used to study esoteric cultures in remote geographic areas, the classic field study location of his discipline. He stated:

Just as an anthropologist gets a better perspective on his own culture through the long and deep study of a radically different one, my extended sojourn in disability has given me, like it or not, a measure of estrangement far beyond the yield of any trip. I now stand somewhat apart from American culture, making me in many ways a stranger. And with this estrangement has come a greater urge to penetrate the veneer of cultural differences and reach an understanding of the underlying unity of all human experience.57

Why should an occupational therapist know about this evolving social phenomenon—disability culture? Is our contribution so bound to a medical model that we cannot acknowledge this cultural expression? What value is our relationship with those who have disabilities if not to support participation in all aspects of occupation, including those expressing a disability cultural perspective?

Design and Disability

Bickenbach, a disability rights law and policy maker, has drawn on Irving Zola’s work,12 reminding us that the “special needs” approach to disability is inevitably short-sighted. If we see the mismatch between impairments and the social, attitudinal, architectural, medical, economic, and political environment as merely a problem facing the individual with a disability, then we are ignoring that disability is an essential feature of the human condition. It is not whether a disability will occur, but when; not so much which one, but how many and in what combination. The entire population is at risk for the impairments associated with chronic illness and disability. As people live longer, the incidence of disability increases. Viewing disability as an abnormality does not provide a realistic picture of the human experience. Bickenback, in his discussion of disability as a human rights issue, underlined the fact that disability is a constant and fundamental part of human experience and that no individual has a perfect set of abilities for all contexts; there are no fixed boundaries dividing all the variations in human abilities. Our usual description of contrast between ability and disability is, in fact, a continuum of functionality in various settings.12

This perspective impacts the occupational therapy role in the realm of assistive technology and modification of the environment to enhance individual performance of occupational behavior. Our literature is overflowing with discussions about assistive technology (see Chapter 17) and environmental modifications: applications with various diagnostic classifications, methods for training one on the use of assistive technology, the usefulness of providing a specialized device to enhance performance, and home modifications. The concept of universal design (the way the environment may be designed to support individual differences) is not as prominent in our professional literature. This idea includes the built environment, information technology, and consumer products, as well as a host of commercial and social transactions, usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design. The concept is thus: if devices (buildings, computers, educational services, etc.) are designed with the needs of people with disabilities in mind, they will be more usable for all users, with or without disabilities.

Disability is just one of many characteristics that an individual might possess that should influence the design of our environments. An example of universal design is ramped entries, which are required by federal law (Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines [ADAAG]) regulations in public buildings (including transportation services such as airports and train stations) and designed for those who use wheelchairs. As that design requirement has become increasingly implemented, the pervasive use of wheeled luggage by all travelers, as well as parents pushing children in strollers and delivery staff with rolling carts, has become commonplace. Just imagine the impact on home modification if new housing construction design included the requirement for one entrance easily adaptable and a bathroom door wide enough for wheelchair access.

Activists from the independent living movement influenced the fledgling personal computer revolution to integrate a multitude of individual preferences from the size and type of the font to the ease with which adaptive technologies such as speech recognition and alternative keyboards interact with operating systems. Universal design of instruction is evident as educators are increasingly trained to include multiple modalities of visual, auditory, and tactile systems to address the needs of people with wide differences in their abilities to see, hear, speak, move, read, write, understand English, attend, organize, engage, and remember.16

It is argued that universal design principles could make assistive technology unnecessary in many situations involving an impairment. A can opener that has been designed for one-handed use by anyone busy preparing multiple steps in a recipe also will also be usable by the cook who has a CVA-caused hemiparesis impairment.

Universally designed devices and aids may be one remedy for the stigmatization attached to special equipment. We know from research with older persons that “potential usefulness of a device is often offset in the minds of clients by concerns about social acceptability and aesthetics.”22 There will always be a need for individually prescribed equipment because impairments and individual needs are associated with so many variations of disability.

Interactional Process: The Person with a Disability and the Environment

International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) restructured its classification (the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, known as ICF) of health and health-related domains that describe body functions and structures, activities, and participation. The domains are classified from body, individual, and societal perspectives. The ICF also includes a list of environmental factors, because the individual performs within a context. The aim of the ICF classification is to provide a unified and standard language and framework to describe changes in body function and structure, what a person with a health condition can do in a standard environment (the person’s level of capacity), as well as what the person actually does in his or her usual environment (the person’s level of performance). The text produced with the language will depend on the users, their creativity, and their scientific orientation. This document is a companion to WHO’s International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10).85 For health practitioners, including occupational therapists, the ICF challenges mainstream ideas on how health and disability are understood.

The ICF stresses health and functioning, rather than disability. Abandoned is the notion that disability begins at the point where health ends. The ICF is a tool for measuring the act of functioning, without regard for the etiology of the impairment. This radical shift emphasizes the person’s level of health, not the individual disability.86

Fougeyrollas and Beauregard pointed out that the revision of the ICF is more aligned with social ecology’s theoretical description of disability and is distanced from reductionist social theory by emphasizing the role of environmental factors. It is also more in accord with the disability rights movement.28 The revised OTPF—Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, second edition—uses the ICF terminology to enhance communication with other healthcare areas.4,34 Disciplines such as ergonomics and occupational therapy consider the environment to be an essential component of human behavior. To illustrate this shift in thinking, social ecologists point particularly to models of human occupation used in occupational therapy, such as the ecology of human performance,25 the human occupation model,40 and the person-environment-occupational model.46 Occupational therapy theory development has had significant influence in changing the paradigm used in rehabilitation by applying holistic and ecological principles to an understanding of the human condition.28

Historically, occupational therapy has been associated with the field of medicine and its emphasis on etiology, or causation, to explain function and disability. In contrast, our profession is presently building an understanding of occupation as a social construction. In keeping consistent with a social model of disability, our focus on occupation produces an “understanding of people for who they are, have come to be, and are in the process of becoming.”59

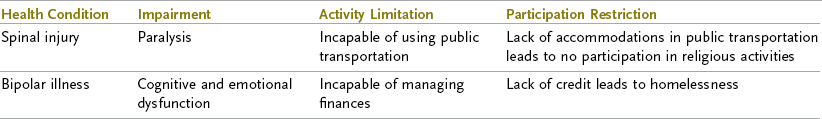

Health, as defined by the WHO, is a state of physical, mental, and social well-being. It is the capacity of the individual to function optimally within his or her environment or the adaptation of the person to his or her environment or setting.28 The ICF moved away from being “a consequences of disease” classification in 1980 to become instead a “components of health” classification. Components of health identify the constituents of health (Table 6-1), whereas consequences of health focused on what may follow as a result of disease. This shifted from an exclusive view of disability from the medical model, directly caused by disease, trauma, or other health conditions that require individual treatment by professionals, to a paradigm that allows for integration of a social model, where disability is not an attribute of an individual but rather a complex collection of conditions, many of which are created by the social environment (Box 6-5). The social model requires social action and is the collective responsibility of society at large to make the environmental modifications necessary for the full participation of people with disabilities in all areas of social life.85

TABLE 6-1

| Part | Component |

| Functioning and disability | Body functions and structuresActivities and participation |

| Contextual factors | Environmental factorsPersonal factors |

According to the WHO, neither the medical model nor the social model provides a complete picture of disability, although both are partially useful. The complex phenomenon called disability can be viewed at the level of a person’s body, as well as primarily viewed at the social level. It is always a dynamic exchange between the characteristics of the person and the overall context within which the person is operating, but some aspects of disability reside within the person (e.g., the cellular changes associated with a disease process), whereas other aspects are essentially external (e.g., fears and prejudice of others about the disease). Thus, both application of the medical and social model are appropriate. The best model of disability is one that synthesizes what is accurate in each model, without the exclusion of the other viewpoint. WHO proposes calling this the biopsychosocial model and has based the ICF on such a synthesis. The aim is an integration of the medical and the social to produce a coherent view of health, incorporating biologic, individual, and social perspectives.86

The ICF allows for the real-world observation that two persons with the same disease can have different levels of functioning, and two persons with the same level of functioning do not necessarily have the same health problem (Table 6-2). Two individuals will generally have different environmental and personal factors interacting with distinct body function.

The shift from the medical model—namely, away from fixing a problem residing within the individual—to an integration in occupational therapy practice of the social model, which accounts for the interaction of the person and the environment, has led to evolving theoretical constructs.21,41 For example, the therapeutic notion of adaptation to environment, whereby individuals are expected to transform themselves through therapy, has been questioned by occupational science theorists. Rather, an interactional, dynamic, reciprocal adaptation of both the person and the environment emphasizes more the social model approach. Cutchin proposed the concept of place integration instead of adaptation to environment, whereby “people are more a part of their environment, and environments more a part of people,”21 with the person’s “motivations and processes never fully independent from the physical, social, and cultural realms that shape the self and desires.”21 In Cutchin’s conclusion, he underlined that client and practitioner are reflexive social selves, with the potential for “the therapeutic moment, one in which the client and therapist are united by place and social ties and by the collaborative effort to coordinate occupation so that person and place become once again integrated and whole.”21

A Canadian study of women wheelchair users underscored these evolving theoretical constructs. The researchers concluded that the barriers these women experienced were a lack of space, stairs, difficult to reach spaces, poor transportation, and limited community access. The study recognized the importance of the many strategies the women used to regain control over their environment and to attain autonomy and participation in the community. The researchers call on clinicians to have sensitivity to the meaning of home by including the relationship between body and environmental features that surround that meaning.65

Swedish researchers, Lexell, Lund, and Iwarsson, studying people with multiple sclerosis (MS), similarly concluded that professionals need to broaden their repertoire to address the social conditions that influence meaningful occupations. They described the way those with MS in their study claimed they were forced to prioritize the most necessary occupations over the most desired occupations and those that could be conducted at any time over those that needed to be preplanned. Planning and addressing the balance of occupations over time is a more complex situation than previously recognized. Moreover, because planning and balance of occupations over time seems so strongly influenced by other people, interventions must be aimed not only at the client but also at other people involved in the client’s occupational engagement.51

Relationship between the OT and the Person with a Disability

Nancy Mairs’s account of her experience with multiple sclerosis in the case study at the beginning of the chapter does not describe her relationships with medical or rehabilitation specialists. One might assume that, at times, there were reasons for her to seek advice, treatment, or consultation with such professionals. The determination of a diagnosis with multiple sclerosis can be a long and arduous journey fraught with miscalculations, multiple speculations of cause, and little of the support one might expect in other aspects of medical rehabilitation, when there is a distinct, sudden onset or trauma.

Occupational therapy values center on a humanistic concern for the individual,59 particularly individuals who have a chronic, severe, and lifelong disability and who will never be cured.89 Some occupational therapy practitioners may be engaged by a person with a temporary disability (e.g., an injury to the hand that gains most or even all of its former function) or work in prevention programs designed to reduce work injuries and do not have contact with those who are considered disabled. However, most people served by occupational therapists have lifelong conditions that cannot be “cured”6 and, therefore, most of those served do not escape the potential for devaluation, stigma, liminality, stereotyping, and the experience of a world designed primarily for those without their differences. Some will have differences that are not observable in casual contact—for example, those with autoimmune deficiencies, seizure disorders, pain, or heart and pulmonary dysfunctions—and yet, once discovered or disclosed by others, produce similar personal and social results.

Rather than eradicating disease, occupational therapists identify and strengthen the healthy aspects or potential of the person. Self-directedness and self-responsibility of the person are emphasized rather than compliance or adherence to orders. A generalist, integrated view of the person as one who interacts with his or her environment guides OT practice rather than a specialist, reductive perspective. This integration requires emphasis on daily life activities and engagement in the occupations expected by the culture. The therapeutic relationships of occupational therapists should be based on mutual cooperation72 rather than an active therapist and passive patient approach. The recipient of our service should be viewed as an agent or actor with goals, interests, and motives and not as one whose behavior is determined by merely physical laws;50 rather, we possess faith in potential ability, actualized by engagement in activity. The recipient’s productivity and participation, rather than relief from responsibility, are emphasized.

Although many occupational therapists provide services in a medical model milieu, we view the client in a way that is different from the traditional medical perspective of diagnosis, cure, and recovery and should follow a different thought process. Our concern with the capacity to engage in daily life activities means that our scope of practice must include not only the hospital setting but also home and community. Thus, occupational therapy may practice both within and outside of the medical milieu, often helping clients to become agents in their own return to health and well-being. In this sense, OT practice bridges the sometimes alien world of acute medical care with engagement in the world of home, family, and culture.

Therapist as an Environmental Factor