Degenerative Diseases of the Central Nervous System

Section 1: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Section 2: Alzheimer’s disease

Section 3: Huntington’s disease

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Describe the course of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

2 Describe the differences between familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

3 Describe the role of the occupational therapist for a client with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

4 Describe the three subtypes of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

5 Identify the symptoms and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.

6 Describe the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease.

7 Describe the overall model of medical management of Alzheimer’s disease used by primary care providers and other health professionals.

8 Describe an approach to evaluation used by occupational therapists.

9 Identify stages of disease progression and general methods of treatment interventions associated with stages of dementia.

10 Describe the course and stages of Huntington’s disease.

11 Identify current research regarding the etiology of the disease.

12 Describe the medical management of Huntington’s disease.

13 Describe the purpose of occupational therapy for a client with Huntington’s disease.

14 Describe the three typical forms of multiple sclerosis.

15 Describe current research regarding the etiology of the disease.

16 Describe the symptoms of multiple sclerosis.

17 Describe complications that may occur as a result of the disease.

18 Describe the role of the occupational therapist for a person with multiple sclerosis.

19 Describe the course and stages of Parkinson’s disease.

20 Identify current research on the etiology of the disease.

21 Describe the medical management of Parkinson’s disease.

22 Describe the role of the occupational therapist for a client with Parkinson’s disease.

Introduction

This chapter addresses the impact of degenerative neurologic disorders on a person’s occupational performance and outlines the role of occupational therapy (OT) in providing services to clients with these disorders. The specific disorders discussed in this chapter are amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease (HD), multiple sclerosis (MS), and Parkinson’s disease (PD).

In degenerative neurologic disorders, the disease progresses and an individual’s occupational performance is often increasingly compromised. OT aims to help the client compensate and adapt as function declines secondary to the disease process. Environmental adaptations and modifications are frequently necessary to maintain functional skills for as long as possible.

Degenerative neurologic diseases may occur because of structural or neurochemical changes within the central nervous system (CNS).72 In the disorders discussed in this section, the client’s CNS usually functions normally during childhood and adolescence. After these years, the client experiences signs and symptoms indicating that CNS functions are deteriorating. The progressive nature of the disorder varies from person to person. Some clients have a rapid decline in function, whereas others maintain functional skills for many years.

The decline in function may compromise the individual’s sense of self-efficacy in performing various tasks.195 No longer is the individual able to perform personal or instrumental activities of daily life at the same level of independence. Dependence on others can alter the client’s concept of self-worth and self-control. The OT practitioner serves an important role in reframing the client’s sense of self even though functional independence may be deteriorating. A man with PD who is unable to dress independently may now direct a personal care attendant or home health aide to perform these tasks. A woman with MS who was previously responsible for household finances may need to instruct a member of the family to complete these activities.

The disorders discussed in this chapter are most often diagnosed during adult or later adult life, after habits, routines, and patterns of independent behavior are well established. A client may encounter a significant change in social relationships and interactions secondary to a decline in functional abilities. The OT practitioner must consider the ways in which progressive loss of function affects the client’s social and occupational roles, whether those roles are as husband, wife, parent, adult child, worker, sibling, or friend. OT must address the needs of the client within the context of his or her social, physical, and cultural environment.

OT intervention aims to support the client’s ability to function within his or her environment. The rate at which the client’s symptoms progress influences the intervention plan. A client who displays progressive loss of fine motor skills over a 20-year period has a much different profile than one who loses all upper extremity function within 2 years. Use of adaptive equipment must be weighed carefully against the rate of deteriorating skills.

The OT practitioner must be knowledgeable about the support services and respite care available to clients with a degenerative neurologic disorder. A PD support group may provide the necessary social support for both a man with this disorder and his family. MS support groups may offer clients information on new intervention methods available, along with the opportunity to share life experiences.

An OT intervention plan should address not only the physical limitations associated with various disorders but also their cognitive, social, and emotional implications. Many individuals with neurodegenerative disorders have concomitant depression. Depression can be a reaction to the loss of function associated with some disorders or the primary symptom of other disorders. Occupational therapists should regularly screen for depressive features. An instrument such as the Beck Depression Inventory can effectively evaluate this component.25,26 In addition to evaluation of depression in clients with neurodegenerative disorders, cognitive abilities should be assessed. Clients may have concomitant cognitive problems because of the destruction of neurologic structures, and these deficits can have a dramatic effect on intervention. Brief assessments such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)65 or the Cognistat154 can be used to determine cognitive abilities and establish a baseline of performance.

In most cases, the occupational therapist is a member of a team providing services to the individual with a degenerative neurologic disorder.98 As a team member, the occupational therapist must consider the roles that other professionals and family members play in the client’s life and incorporate this knowledge into the intervention plan. OT practitioners provide a unique and needed service to individuals with degenerative neurologic disorders. A client who is able to engage in meaningful occupations despite deteriorating skills reflects the significant contribution of OT.

Two case studies are presented to illustrate the similarities and differences among clients faced with degenerative neurologic disorders. The first case concerns a woman who has MS. That case is presented at the beginning of the chapter. The second case concerns a man with PD and is presented at the end of the chapter to serve as a review. The cases should serve to prompt clinical reasoning and decision making as you read this chapter.

Section 1 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

This section of the chapter focuses on both areas of occupation and performance skills. Diagnosis and progression of disease are described in terms of the loss of performance skills, whereas Box 35-1 describes the OT interventions in relation to both occupation and performance skills as identified in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework.

The term amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is used to identify a group of progressive, degenerative neuromuscular diseases. The underlying neurologic process involves destruction of motor neurons within the spinal cord, brainstem, and motor cortex.28,35 Affected individuals exhibit a combination of both upper motor neuron (UMN) and lower motor neuron (LMN) deficits at some point in the progression of the disease.

In the United States, ALS is also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease; in France, it is referred to as Charcot’s disease.27 The term motor neuron disease refers to a group of diseases that includes ALS, progressive bulbar palsy, progressive spinal muscular atrophy, and primary lateral sclerosis.106,151 Table 35-1 provides a description of each of these distinct subtypes of ALS. The classic forms of ALS are presented in this section.

TABLE 35-1

Clinical Subtypes of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

| Name | Area of Destruction | Symptoms |

| Progressive bulbar palsy (bulbar form) | Corticobulbar tracts and brainstem motor nuclei involved | Dysarthria, dysphagia, facial and tongue weakness, and wasting |

| Progressive spinal muscular atrophy (lower motor neuron form) | Lower motor neurons in the spinal cord and sometimes the brainstem | Marked muscle wasting of the limbs, trunk, and sometimes the bulbar muscles |

| Primary lateral sclerosis (upper motor neuron form)* | Destruction of cortical motor neurons; may involve both the corticospinal and corticobulbar regions | Progressive spastic paraparesis |

*The World Federation of Neurology classification of spinal muscular atrophy and other disorders of the motor neurons does not identify primary lateral sclerosis as a subtype of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.27 This author is including primary lateral sclerosis in the list in recognition of the many other articles and books that recognize it as a subtype of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

From Belsh JM, Schiffman PL, editors: ALS diagnosis and management for the clinician, Armonk, NY, 1996, Futura; and Guberman A: An introduction to clinical neurology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment, Boston, Mass, 1994, Little, Brown.

The incidence of ALS is about 2.0 per 100,000 people, and it is diagnosed in approximately 5000 people in the United States each year.146 Two forms of ALS are recognized: sporadic and familial. Sporadic ALS makes up about 90% to 95% of the ALS population. Between 5% and 10% of individuals with ALS are found to have a family history of the disease. There is no difference in the symptoms of clients with the familial and sporadic types.

The diagnosis is primarily determined by clinical symptoms and ruling out other neurologic disorders.27 Multiple tests and a thorough neurologic examination provide a differential diagnosis. Tests include electromyography and nerve conduction velocity; blood and urine studies, including high-resolution serum protein electrophoresis, thyroid and parathyroid hormone levels, and 24-hour urine collection to assess for heavy metals; spinal tap; radiographs; magnetic resonance imaging; myelography of the cervical spine; and muscle and/or nerve biopsy.1,27,28,35

Pathophysiology

The etiology of ALS has not been established. Multiple theories have been proposed as the cause of the motor neuron destruction, including metabolic disorders of glutamate insufficiency, metal toxicity, autoimmune factors, genetic factors, and viral infection.187

Clinical Picture

The symptoms of ALS are variable, depending on the initial area of motor neuron destruction. An individual with ALS typically has a focal weakness beginning in the arm, leg, or bulbar muscles. The individual may trip or drop things and may have slurred speech, abnormal fatigue, and uncontrollable periods of laughing or crying (i.e., emotional lability). As the disease progresses, marked muscle atrophy, weight loss, spasticity, muscle cramping, and fasciculations (i.e., twitching of the muscle fascicles at rest) ensue. The individual may have greater difficulty with walking, dressing, fine motor activities, swallowing, and breathing. In the end stages the individual may require tube feedings and the support of a ventilator for respiration. ALS is a rapidly progressive disease with the majority dying of respiratory failure in 3 to 5 years after the onset of symptoms if no tracheostomy is performed. Approximately 10% of the population will live 10 years or longer.146 As ALS progresses, the disorder does not affect a person’s eye function, bowel and bladder function, or sensory function. Recent research has found that cognitive changes occur in 20% to 25% of the population with ALS. Specific cognitive deficits have been identified such as frontal temporal lobe dysfunction. As many as half may have mild to moderate cognitive or behavioral abnormalities. “Risk factors for developing cognitive problems, behavior changes or a full-fledged dementia syndrome may include: older age, bulbar onset ALS, a reduction in FVC (functional vital capacity) and a family history of dementia.”1,125,177

The prognosis is difficult to predict. Generally, individuals with early bulbar involvement have a poorer prognosis. A more positive prognosis is usually associated with the following factors: younger age at onset; onset involving LMNs located in the spinal cord; deficits in either UMNs or LMNs, not a combination of both areas; absent or slow changes in respiratory function; fewer fasciculations; and a longer time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis. In some cases, the client’s condition stabilizes, with little progression of the disease.86

A client with ALS differs from a client, such as Marguerite, with MS; with ALS the loss of function is more rapid, without episodes of remission. A person with ALS must cope with a fatal disease, whereas a person with MS must cope with a chronically disabling condition.

Medical Management

The American Academy of Neurology has established practice parameters and standards to address major management issues for persons with ALS. An OT practitioner working with this population should be familiar with the standards to better understand the approaches and rationale for intervention. The parameters cover the following topics: how to inform the client of the diagnosis, when to consider noninvasive and invasive ventilator support, evaluation of dysphagia and intervention with a feeding tube, management of saliva and pain, and use of hospice services.133

Symptoms such as muscle cramping, excessive saliva, depression, and pain are managed with medication. The client’s respiratory status should be re-evaluated frequently to determine when noninvasive and invasive ventilator support is necessary. Swallowing function should also be evaluated frequently to prevent aspiration and to determine when and whether a feeding tube should be placed.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the drug riluzole (Rilutek) in 1995. Riluzole, an antiglutamate, was the first drug used specifically to alter the course of the disease by prolonging survival. In addition to inhibiting the release of glutamate from nerve endings, it blocks amino acid receptors on the cell bodies.187 Researchers believe that the success of riluzole indicates that an excess of glutamate leads to the death of motor neurons. Research has shown that riluzole prolongs the life of clients with ALS by at least a few months.142

Other medications and stem cell research204 for the treatment of ALS are currently in clinical trial.28,217 The clinical trials are focused on extending survival and slowing the decline associated with the disease.

Occupational Therapy Evaluation and Intervention

It is essential to work with the client and family throughout progression of the disease as needs change. Cultural, social, and spiritual values must be understood because these factors will influence ongoing decisions about personal care and life support. The client and family members must regularly update decisions about care. Decisions range from when or whether a wheelchair or adaptive eating device should be used to whether the client should undergo a tracheostomy, choose tube feeding, or use a ventilator. Psychosocial support regarding decisions about the extent of life support and medical intervention should be provided by the entire health care team, with the physician and client having primary responsibility. Several studies have shown that caregivers and patients have different needs and perceptions of quality of life. It may be beneficial for patients and caregivers to have time for education and support separately to meet their individual needs.32,88,162

Initial and ongoing OT assessment is essential to educate the client about ways to adapt functional activities as the disease progresses. Education is needed for nursing staff and physicians to understand the role of the occupational therapist in the treatment of clients with ALS.

Steady disintegration in the ability to speak, swallow, move, and perform activities of daily living (ADLs) makes it easy to overlook the presence of some common signs of cognitive or behavioral dysfunction, such as poor insight and deficits in planning.1 Multiple cognitive domains may be affected in persons with ALS, including psychomotor speed, fluency, language, visual memory, immediate verbal memory, and executive function.177

With impaired executive function, a person with ALS may have difficulty handling the visual, auditory, and other sensory data required for complex decision making.125 These cognitive and behavioral issues are pertinent when considering teaching strategies and the need for caregiver counseling and support.

Role of the Occupational Therapist

ALS progresses rapidly, with ongoing deterioration in physical status and possibly cognitive deficits. The intervention plan should focus on the client’s participation in occupational performance because the client’s functional status changes frequently and intervention focused on physical performance is limited. As the client’s function declines, there is a greater need for environmental support through providing durable medical equipment, modifying the home, and providing adaptive equipment. Depending on the client’s level of understanding, life support choices, and acceptance of the disease, the OT intervention may focus on structuring the client’s environment to support independence.45 Some clients with ALS may choose to have the maximum environmental and life support available to extend life. In this case, the occupational therapist may provide periodic re-evaluations to determine the client’s need for adapting self-care, work, and leisure activities. Other clients may request that no extraordinary life support be used, in which case the occupational therapist would assume a supportive role, perhaps helping these clients create a memory book to give to their loved ones. Table 35-2 provides a list of the functional deficits at various stages of the disease and interventions that may be required. When referring to this table, the OT practitioner must remember that each client’s clinical picture is unique and that symptoms may appear in a different sequence than the table indicates. For example, a client with early-onset bulbar signs may require earlier intervention regarding swallowing assessment and communication devices; another client may not need a wheelchair until the very late stages. Olney’s resource manual, Daily Activities Made Easier for People with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, provides practical solutions for ADLs and a variety of resources that address many of the problems that this population faces and is an invaluable resource for practitioners, patients, and families.32,131

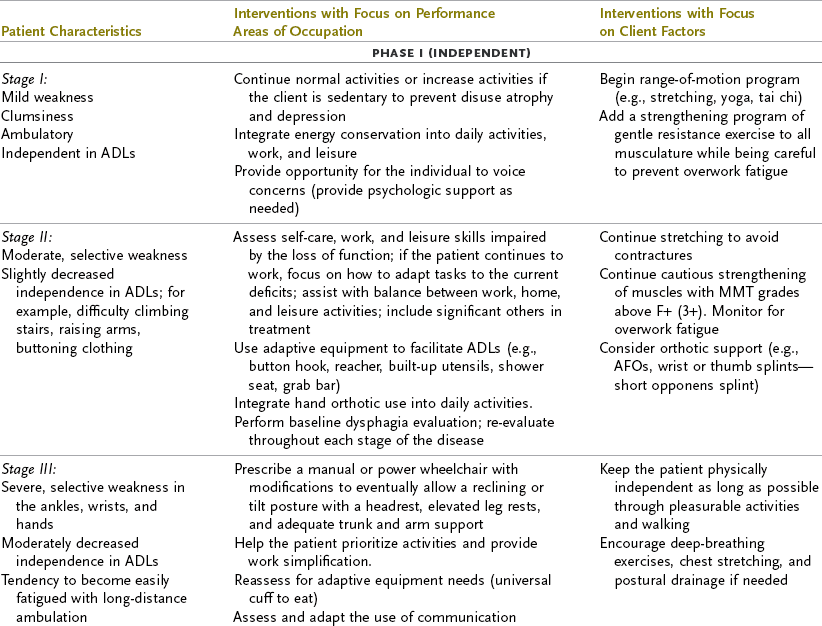

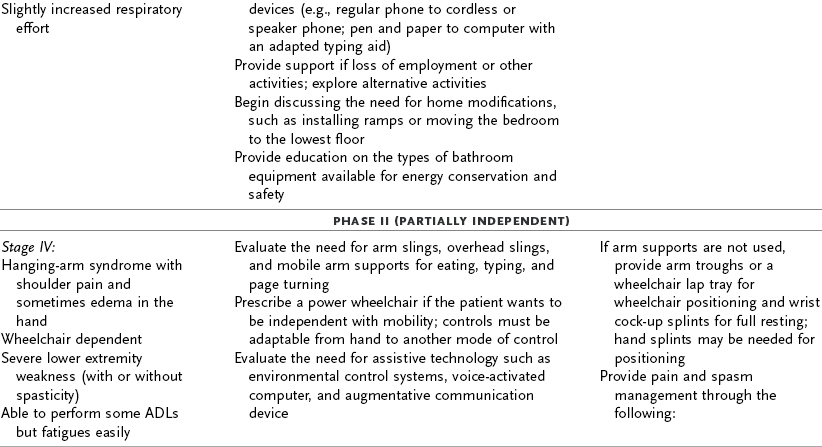

TABLE 35-2

Interventions for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

ADL, activities of daily living; AFO, ankle-foot orthosis; MMT, manual muscle test.

Modified from Yase Y, Tsubaki T, editors: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: recent advances in research and treatment, Amsterdam, 1988, Elsevier; and Umphred DA, editor: Neurological rehabilitation, ed 3, St. Louis, Mo, 1995, Mosby.

Individuals and their families require an interdisciplinary approach to the rapid changes in function, complex psychosocial factors, and quality-of-life issues associated with ALS. The impact of the disease on the client’s quality of life has been examined frequently. One study indicated that those who were less distressed and less depressed129,131,133 and had a more positive attitude lived longer.91 Fatigue and depression have been associated with a poor quality of life for an individual with ALS.121 The same study found that progression of the disease was not necessarily associated with a poor quality of life. Hecht and colleagues91 found that social withdrawal correlated with levels of disability; based on the results of this investigation, the authors recommended that mobility be improved with power wheelchairs and public transportation to prevent social withdrawal. Studies have also examined the impact of hope, spirituality, and religion as a means of coping with the disease.

Summary

ALS is a rapidly progressing, fatal condition of unknown etiology. OT aims to maximize the client’s function by providing interventions and periodic reassessment to compensate for declining motor function through modification of the environment, roles, and tasks and by helping the client and family achieve self-identified goals.

Section 2 Alzheimer’s Disease

Dementia is the general word used for a group of symptoms caused by serious disorders of the brain. Memory loss and other related problems in language, perception, thinking, and judgment interfere with learning, communicating, relating, and even caring for self. Dementia is not just one disease but includes a number of diseases (e.g., vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia). The most common dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, especially in persons older than 65 years.

AD is considered a primary dementia because it does not result from other diseases. Secondary dementia may be used to refer to symptoms of dementia that are associated with other physical diseases (PD, ALS, MS, HD) and are discussed elsewhere in this chapter. AD, unlike the other neurologic disorders discussed in this chapter, is formally classified as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association.11 The exact cause of AD is still unknown. Because of the damage to brain cells and irreversible cognitive decline, the disease results in impaired higher mental processes, altered behavior, and disturbances in mood. The disorder progresses gradually and produces multiple cognitive deficits, a significant decline from previous levels of functioning, and noticeable impairment in social and occupational functioning. Effects on the motor and sensory systems are not apparent until later in the disease process. Dementia is a significant health care problem because of the increasing number of individuals who are living longer, the higher incidence of dementia in older persons, the very high cost of supervised care, and the extensive use of medical resources.93 Almost three times as much money is spent by Medicare for persons with AD and other dementias as for beneficiaries without AD.4,6 Early recognition of cognitive decline by physicians, occupational therapists, and all other health care professionals is critical. Slower progression of the disease, greater understanding of functional decline, improved quality of life, and time to prepare for the future for older adults and their families could be an outcome of early recognition. AD is often overlooked or mistaken for other disorders, especially in the early stages.

Incidence

AD accounts for more than two thirds of cases of dementia, and the incidence increases dramatically as people age.4,6,41,61,184,225 It is estimated that close to 13% of adults 65 years or older have AD. The disease affects more than 5 million people in the United States, and 4.9 million are older than 65 years. Age is the strongest primary risk factor. The incidence of AD more than doubles for every 5 years above the age of 65. It is estimated that 40% to 50% of the population of old-old (85+ years) adults have AD. Many more Americans are surviving into their 80s and 90s because of advances in medical technology. In a recent study of 97-year-olds, 61% of the population had some form of dementia.104 As the population of old-old adults continues to grow, the number of persons with AD is also expected to grow. Family history and genetics are other risk factors for AD.70 Early-onset, familial forms of AD are linked to genetic mutations on chromosomes 1, 14, and 21.81,117,150,199 Late-onset AD has been linked to the apolipoprotein E-4 (APOE-4) allele on chromosome 19, but it should be noted that this allele has also been found in older persons who do not have AD.150,151,172 It is generally agreed that although genetic factors pose some risk for late-onset AD, it is the interactive effects of diet, lifestyle, and environment affecting each person differently. This field of research is known as epigenetics. Three new genes thought to have a role in late-onset AD have recently been discovered by researchers.69,150 Two of these genes are responsible for protein encoding (CLU—clearing β-amyloid; PICALM—recycling cell membrane proteins at synapses), and a third gene, CR1 (complement receptor 1), is responsible for the inflammatory response and clearing of β-amyloid. Scientists conducting AD research are currently exploring the idea that changes in the regulation of genes—turning them on and off through the interactive effects of nature and nurture—and not just gene mutations can make someone more or less susceptible to AD.150 Previous head trauma is a well-established risk factor for AD; other factors that result in increased risk include diabetes mellitus, APOE gene variation, current smoking, and depression. Limited evidence shows increased risk associated with use of estrogens and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and the evidence is inconsistent for risk factors associated with heart disease, high blood pressure, and obesity. Researchers are also exploring the effects of certain inhaled anesthetics, lead exposure, and timing of the use of hormone replacement therapy after menopause.148–150

Although the incidence of dementia is growing rapidly, it does not occur in all older adults. Many older adults experience a normal slowing of information processing, called age-related cognitive decline. Clinically significant cognitive deficits do not develop in this population.11 Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a condition that involves problems with memory, language, or other essential cognitive functions that is serious enough to be noticeable to others and to show up on tests, develops in a proportion of the older adult population, but this impairment is not severe enough to interfere with daily life.148 In some, but not all persons with MCI, AD eventually develops. A study by Driscoll and colleagues found that persons with MCI showed brain atrophy, but the group in whom AD eventually developed exhibited a pattern of atrophy in the region of the temporal lobes.58 A term sometimes used by laypersons to refer to older adults with memory loss or cognitive impairments is senility. Senility is not a medical term. Use of the word senility perpetuates stereotypic impressions that progressive cognitive decline occurs in normal aging. Such ideas prevent early recognition and accurate diagnosis of dementia.

Pathophysiology

AD is the result of degenerative changes in the CNS. Neuroanatomic (structural) and neurochemical changes occur in genetically and/or environmentally susceptible brains.134 Many neurons die, stop functioning, or lose their connections with other neurons. Disruption of communication, metabolism, and neuron repair occurs. The result of these changes is progressive and diffuse neuronal loss in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus.150,194 Three noticeable pathologic changes have been found through microscopic examination of brain tissue after death: accumulation of amyloid in the space between neurons, increased neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, and loss of neurons and synapses. Early AD is associated with decreased cholinergic markers in areas of the brain with an increased distribution of plaques and tangles. Many of the changes in the brains of persons with AD can be seen only at autopsy, although neuroimaging techniques (e.g., computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and positron emission tomography [PET]) provide further diagnostic information such as enlarged ventricles. The degenerative changes in the brain involve several processes that affect neurotransmission and result in neuronal death.194 Studies suggest that the sequence of disease events in individuals with AD involves amyloid deposits in the earliest stages that are not yet associated with actual cognitive impairment.136,150,209 Later, abnormal tau protein accumulates and causes loss of synapses, neurons, and brain volume An inflammatory process causes the tau proteins in cortical and limbic neurons to undergo microtubular dysfunction, which prevents neurons from sending nutrients and hormones along the axons. The paired filaments of these intracellular proteins actually become cross-linked in an abnormal metabolic process. These filaments form neurofibrillary tangles that eventually lead to neuron death as the neuron transport system collapses. Neurofibrillary tangles are also seen in the temporal areas and to a lesser degree in the parietal association areas.

Neuritic plaques are large, extraneuronal bodies consisting of accumulated β-amyloid and neuronal debris—small axons and dendrites. Neuronal plaques predominate in the temporal and parietal areas in early AD. This material degenerates and takes up cellular space. Extracellular accumulation of too much insoluble β-amyloid in neuritic plaques contributes to the neuron degeneration. When neurons lose their connections, they cannot function and eventually die. The neuron degeneration and death spread through the brain, connections between other neurons break down, and affected regions begin to shrink in a process called brain atrophy. By the final stage of AD, damage is widespread, and brain tissue has shrunk significantly. The production of high levels of insoluble β-amyloid is associated with early-onset familial AD and has been linked to genetic markers on chromosomes 1, 14, and 21.81,117,199 In late-onset AD, the accumulation of amyloid deposits may be affected by APOE-4 on chromosome 19 and can also affect the development of neurofibrillary tangles.197 Scientists anticipate that an understanding of the mutation in chromosomes associated with early-onset AD will help them better understand late-onset AD.150 Late-onset AD is more likely related to a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that affect the regulation of gene expression, which can differ from person to person.51

Cholinergic dysfunction also occurs in individuals with AD, and this depletion in neurotransmitter is the process responsible for the expression of clinical symptoms, such as deficits in memory and word-finding problems, in early AD. Specifically, cholinergic deficits, thought to be linked to APOE-4, include less choline acetyltransferase activity in the frontal cortex, hippocampus, and temporal cortex.169,171,194 These areas of the brain are associated with such symptoms of AD as recent memory impairment and problems in executive functions.

Clinical Picture

Initially, the signs and symptoms of AD may seem puzzling because the disease can affect different people in different ways.4 The symptom that is most prominent is the progressive inability to remember new information. Recently, the Alzheimer’s Association compiled a checklist, “Know the 10 Signs,”5 an Early Detection Matters education campaign that assists older adults and their families in early recognition and contact with their primary care physician. The symptoms and patterns of behavior in persons with AD are often described in terms of stages, but it is important to recognize that it can be difficult to place a person with AD in a specific stage because stages may overlap.196 The simplest description of staging, useful for caregivers and consumers, defines the progression of AD in terms of a three-point stage scale: early, middle, and late stages.80 A more clinically and diagnostically complex scale, such as the seven-point Global Deterioration Scale (GDS),182,183 is used in research or modified for diagnostic purposes and is often used as part of an assessment battery. It is important to realize that not all persons with AD will progress at the same rate or have the same pattern of symptoms despite the GDS staging framework.

The primary symptom of AD is impairment in recent memory that worsens with time, with at least one other cognitive deficit being present, such as apraxia, aphasia, agnosia, or impaired executive function, according to the American Psychiatric Association.11 Memory impairment involves increased difficulty learning new information and recalling information after more than a few minutes.150,205 Over time, the ability to learn deteriorates further and the ability to recall old memories also declines. Symptoms such as speech and language problems, impaired recognition of previously familiar objects, and impaired ability to perform planned motor movement are more variable and may not be seen in all persons with AD. Expression of symptoms depends on the areas of the brain most affected by the disease. Executive function (the ability to initiate, plan, organize, implement safely, and judge and monitor performance) inevitably deteriorates as AD progresses. Visuospatial dysfunction is common. Changes in mood and behavior consisting of personality shifts and the development of depression, anxiety, and increased irritability are often observed in the early stages of AD.130 Later in the course of the disease, troubling behavioral problems such as agitation, psychosis (i.e., delusions and hallucinations), aggression, and wandering can emerge.4,6,148,150 Motor performance areas such as gait and balance may become impaired, and sensory changes usually arise in the middle to later stages of the course of AD (see Table 35-3). Frequently, delirium and depression complicate the clinical picture. The life expectancy following the diagnosis of AD is typically 8 to 10 years but can range from 3 to 20 years, with a variable rate of progression.137

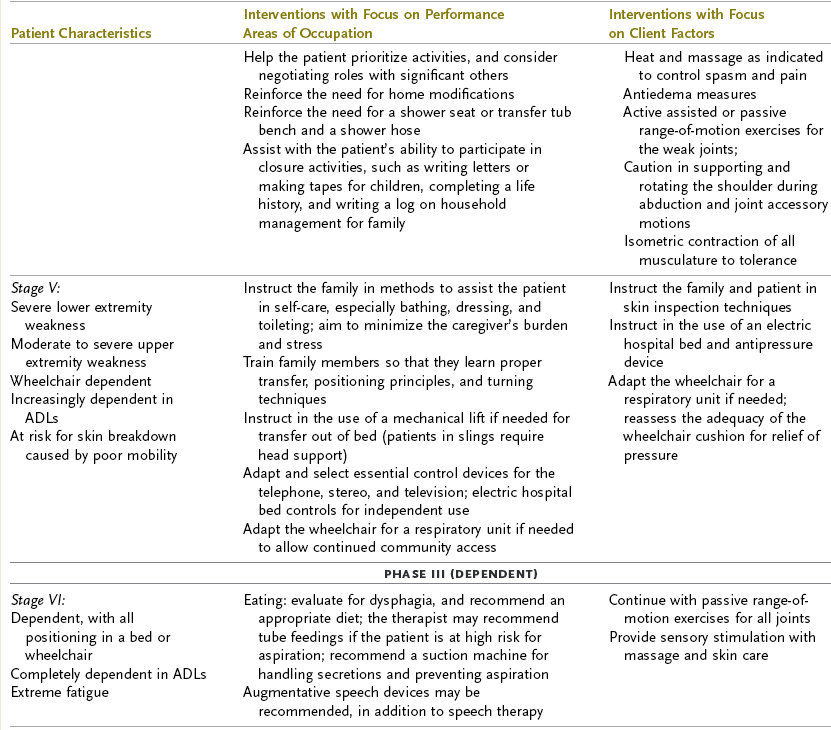

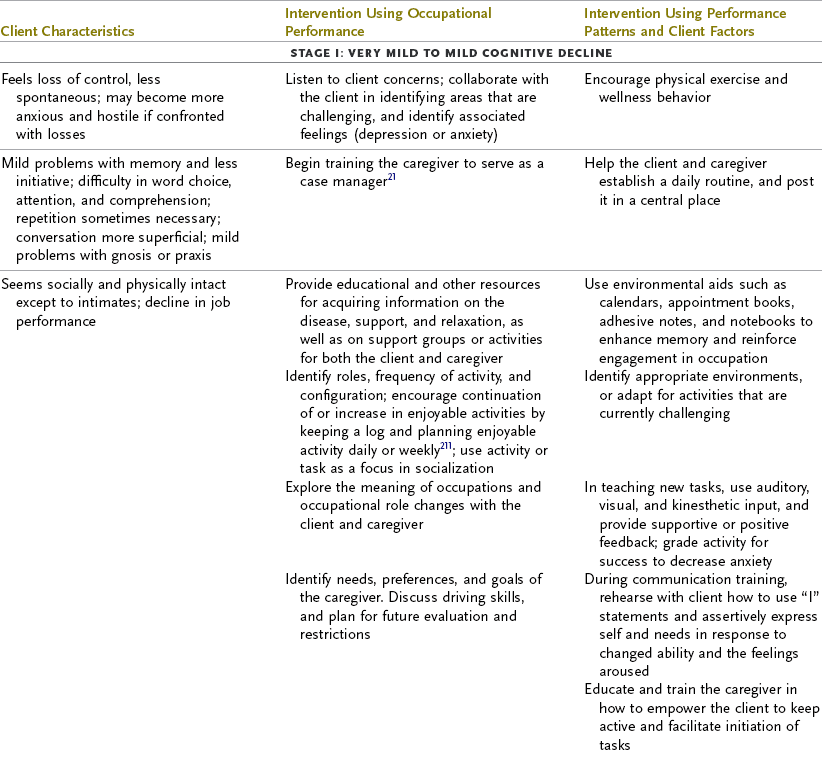

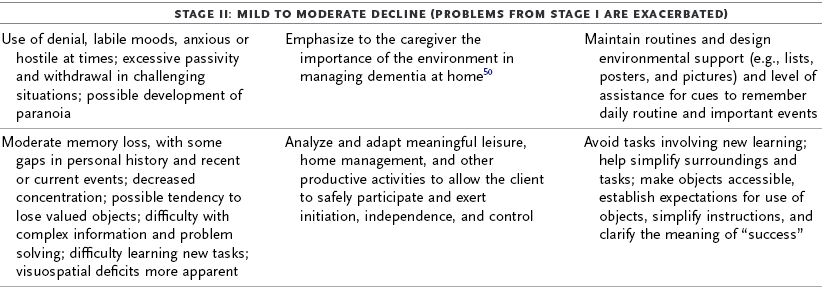

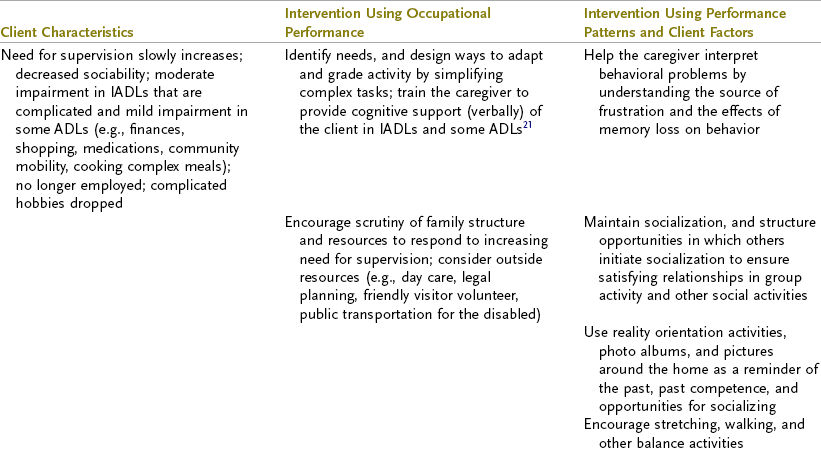

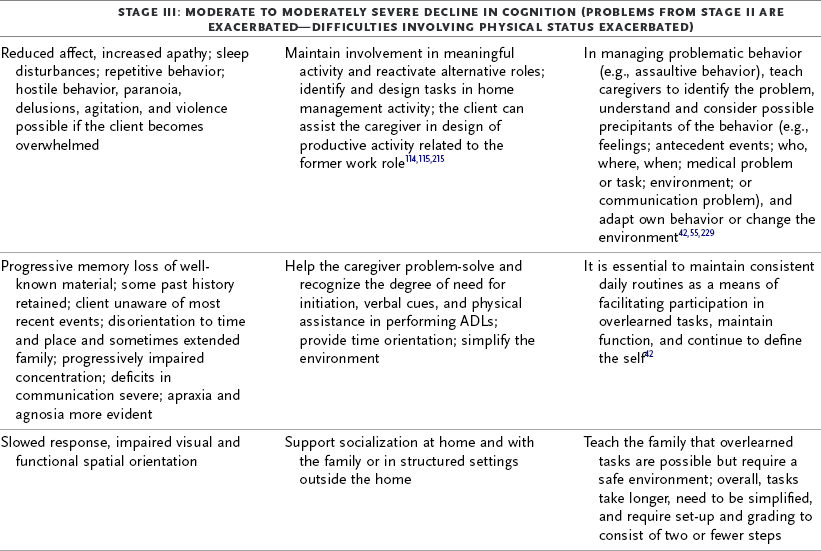

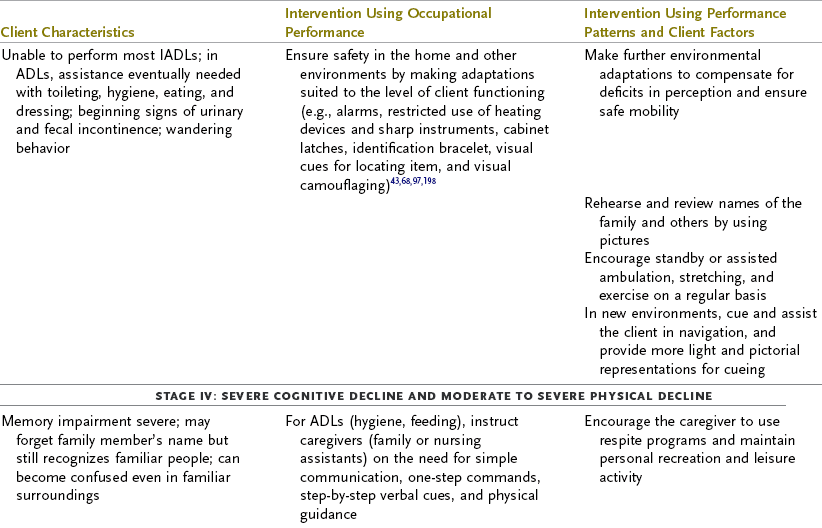

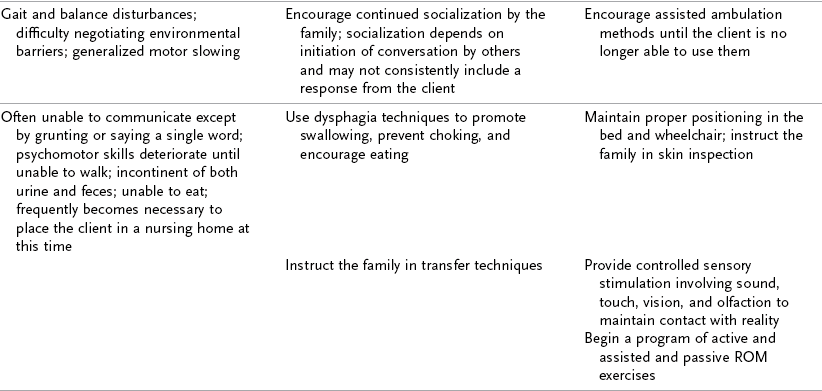

TABLE 35-3

Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease and Intervention Considerations

ADL, activities of daily living; AFO, ankle-foot orthosis; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; MMT, manual muscle test; ROM, range of motion.

Adapted from Baum C: Addressing the needs of the cognitively impaired elderly from a family policy perspective, Am J Occup Ther 45:594, 1991; Morscheck P: An overview of Alzheimer’s disease and long term care, Pride J Long-Term Health Care 3:4, 1984; Glickstein J: Therapeutic interventions in Alzheimer’s disease, Gaithersburg, Md, 1997, Aspen; Gwyther L, Matteson M: Care for the caregivers, J Gerontol Nurs 9, 1983.

Deterioration in the individual’s functional performance usually occurs in a hierarchic pattern. This pattern of decline initially consists of a gradual progression from mild impairments in work and leisure performance to more moderate difficulty in performing instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), especially finances and driving. Eventually, there is progressive loss of the ability to perform even basic self-care ADL tasks. The pattern of disability is usually characterized by lower extremity ADL problems (walking) before decline in upper extremity ADL functions.87,208 The trend in AD is for cognitive deficits to increase and executive function to become more impaired (see Table 35-3). Motivation and perception can influence functional performance but may not be routinely considered in individuals with AD (Levy, 2005).68

Medical Management

According to Larson,109 medical management of individuals with AD in primary care settings generally includes several areas. Many aspects of what is termed medical management may also be performed by certain other members of an interdisciplinary health care team, including the nurse, social worker, physical therapist, or occupational therapist. First, early recognition and diagnosis of AD are needed.109,148,193 Second is the issue of how to intervene on behalf of a person with AD who is living in the community before institutionalization or more restrictive care becomes necessary. The third area concerns intervention issues as the disease progresses. Last is the role of health care providers in recognizing and addressing the treatment of other conditions that lead to excess disability in a person with AD.

The brain damage caused by AD begins much earlier than the appearance of cognitive impairment. Although dementia is relatively common in persons older than 80 years, it is often not diagnosed in such individuals until approximately 2 to 4 years after the onset of dementia symptoms.108,109,111,128 Recent evidence suggests that AD eventually develops in as many as 23% of persons with MCI.38,148,220 Wilson and colleagues identified olfactory impairment in persons in whom AD later developed.226 Identification of motor, visuospatial, and other sensory deficits, even before impaired memory is evident, is a current area of research that may aid in earlier detection of AD.148,150 The Alzheimer’s Association has made a concerted effort to help in the earlier diagnosis of older adults through their Early Detection Matters program.6 A comprehensive physical examination, laboratory evaluation, mental status examination, brief neurologic examination, and informant and family interview are essential in diagnosing AD. It is important to identify and treat medical conditions (e.g., metabolic disturbances, infections, alcohol use, vitamin deficiencies, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and drug toxicity) that can contribute to comorbidity. Findings on MRI, PET, and CT can be useful, but overreliance on these techniques should be avoided because their value lies in identifying relatively uncommon, treatable causes of cognitive impairment. A comprehensive and skillful interview with a reliable informant is essential to the evaluation and diagnostic process to recognize decline by comparing current changes with past performance. Informant questionnaires, interviews, and screening measures may be performed by many health care professionals other than physicians and are important in the diagnostic process. National Institute on Aging145–funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers can diagnose AD with up to 90% accuracy,150 although autopsy is the only diagnostic tool with 100% accuracy. Cognitive testing and testing of cerebrospinal fluid are two developing areas for earlier detection and diagnosis.

The goal of health care providers in the successful management of an individual with dementia, whether in the community or in a semi-institutional or institutional setting, is to “minimize behavior disturbances, maximize function and independence, and foster a safe and secure environment”205 (p. 1367). Dementia is associated with increased mortality.34 Regular health maintenance visits in primary care settings to identify treatable illnesses such as depression, PD, low folate levels, arthritic conditions, urinary tract infections, and other conditions that may complicate dementia are important for all older adults, especially those with AD.113,194 New evidence suggests that the cellular abnormalities of vascular disease (high blood pressure, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes) exacerbate the cellular abnormalities found in AD, increase the risk, and may speed the progression of AD.150 Depression and dementia may easily be mistaken for each other, or they may coexist.205 Careful attention to whether the onset of symptoms has been gradual (dementia) or more recent (depression) is an important diagnostic issue because affective and cognitive symptoms frequently occur together.181 The cognitive impairments and especially functional performance may improve in individuals with both dementia and depression after they are treated for depression. Delirium (i.e., impairment in attention, alertness, and perception) and dementia frequently coexist as well, especially in hospital settings.205 Both conditions involve global cognitive impairment, but delirium is usually acute in onset, shows fluctuating symptoms, disrupts consciousness and attention, and interferes with sleep. Adverse drug reactions are more common in AD because of the vulnerable, impaired brain.110 Drug toxicity, often a cause of delirium, is treatable.

Hearing, vision, and other sensory impairments are known to make dementia worse and cause greater strain on the caregiver.218,219 Falls with hip fractures are 5 to 10 times more common in persons with AD than in normal persons of the same age and frequently result in earlier institutionalization for the individual and the need for higher levels of care.36 Unsafe mobility quickly becomes an overwhelming burden for caregivers, especially those who are aged. Occupational therapists can assess the tasks, context, and environmental features of the living situation in which the person with AD resides and find ways to analyze activities and make compensations so that living is more meaningful and safe.

According to Small and colleagues205 and the most recent progress report on AD from the National Institutes of Health,150 pharmacotherapy for the treatment of individuals with AD should be assessed carefully and justified at regular intervals.192 Although OT practitioners do not prescribe medications, knowledge of pharmacotherapy is useful. Cholinesterase inhibitors such as galantamine and donepezil may improve cognition and functional performance, at least in the short term. The drug memantine blocks receptors for glutamate and has been used in individuals with moderate to severe AD.150 Promising research is under way in this area. Cognitive health is highly related to the health of blood vessels in the brain. Controlling blood pressure, using cholesterol-lowering drugs, eating a Mediterranean diet, and maintaining physical activity are strategies for vascular health and are also thought to reduce the risk for AD. Antidepressant medications, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, are often prescribed to manage the behavioral manifestations of AD—but it should be noted that these medications are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AD. It is important to note that some of the tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, imipramine, and clomipramine) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors can have troublesome side effects in older adults. Atypical antipsychotics such as clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine may be used to reduce agitation and psychosis.123,205 Benzodiazepines are prescribed for treating anxiety and infrequent agitation but have been found to be less effective than antipsychotics when the symptoms are severe.205

Role of the Occupational Therapist

Most individuals with AD live in the community, alone or with family or friends, rather than in institutions. A predominant feature of AD is significant and progressive deterioration in function from previous levels of performance because of advancing brain atrophy and pathologic tissue changes. Families and significant others associated with persons with AD become progressively involved as the disease itself progresses and provide increasing oversight and personal assistance.77 Changes in the brain caused by AD result in deficits in client factors, which in turn lead to deterioration in occupational performance skills and occupational performance areas and major changes in occupational roles. Over time, more structured, supervised living environments are usually needed. Increased difficulty in performing everyday functions creates challenges for the individual with AD and has an impact on quality of life for the client, family, and caregivers as the disease progresses. Effective OT interventions must be directed at supporting occupational performance for the individual and creating as much quality of life as possible. Intervention should focus on supporting and maintaining capabilities and adapting tasks and environments or otherwise compensating for declining function in individuals with AD while trying to help them retain as much control as possible over their lives in the least restrictive environment.10 Adult day care centers can often provide an alternative to assisted living or skilled nursing facilities; they offer a safe, structured day program for persons with cognitive impairments who still reside at home and allow them to be in the least restrictive setting and able to return to their caregivers in the evenings. The Program of All-Inclusive Care is one model of day care available in some communities and offers innovative, high-quality care for older adults at high risk for needing institutional care (Trice, 2006).79

Behavioral problems can be expected in clients with AD until the terminal or bed-bound stage. Encouragement to use respite care, in-home support services, and caregiver support groups is important. Caregivers also need effective strategies for dealing with behavioral disturbances and disruptions in mood. The use of environmental adaptations, therapeutic interpersonal approaches, referral to other disciplines, and sharing of resources helps in collaborating with the client’s family and handling these problems. Health professionals use education, training, counseling, and support to help caregivers deal with their feelings, manage behavior, and maintain quality of life for themselves and for the client with AD. Awareness of the multidimensional effects of this illness on the individual, the family, and the society at large is important to promote more effective and efficient care.178 Specialized homes and units known as Alzheimer’s Care Centers are available.79 The model of care is one of wellness support instead of an illness model of care. The idea is to maximize and support independence, maintain safety, and focus on the strengths and remaining skills of the individual. The Alzheimer’s Association5 has developed “Dementia Care Practice Recommendations” for dementia care centers, and these guidelines are supported by the American Occupational Therapy Association. The fundamentals are provision of food and fluid, management of pain, resident wandering, falls, physical free restraint, and social engagement.5,79

Evaluation

An OT screening is often performed before the evaluation. OT services are indicated for individuals who have demonstrated a recent decline in function; whose behavior poses a safety hazard to family, staff, other residents, or self; or who may experience improved quality of life.30 Much of the therapist’s time in community settings and in long-term care is spent helping families and caregivers develop strategies and environmental adaptations to cope with the overwhelming stress of safely managing a cognitively impaired individual.21 The other major focus is promoting the best quality of life that is possible while ensuring that no matter the setting, a person with AD has choice, dignity, and self-determination.

The type of assessment and the depth of the evaluation process used are influenced by the setting, the stage of progression of AD, the reimbursement process, the presence of other medical and mental health disorders, and the cooperation and interest of the caregiver or care staff. The consequences of caregiving and the needs of the caregiver can vary greatly, depending on gender, family relationships, culture, and ethnicity. The caregiver’s understanding of dementia, reaction to dementia-related behavior, use of problem-solving skills, use of the environment, use of formal and informal support systems, and decision-making style greatly affect the caregiver’s ability to participate in the care plan and treatment of persons with dementia.19,49,60,118,227 In some cases the occupational therapist must engage in the dual role of serving as an advocate for the person with AD.

Evaluation should be comprehensive despite changing reimbursement. Much information can be gathered before an interview and intervention session by asking caregivers, family members, and staff informants to complete questionnaires and rating scales. These scales assess occupational performance, functional abilities, and skills with the use of measures such as the Functional Behavior Profile,23 the Activity Profile,21 the Caregiver’s Strain Questionnaire,188 the Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale,103 and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale.112 Informant rating measures should routinely be followed by an interview either before or during the first visit. The use of a few brief screening instruments for mental status (e.g., the MMSE),65 depression,26,228 and anxiety113 provides baseline data and a wealth of information about factors that are likely to influence performance. It is always useful, with any evaluation, to triangulate information to achieve reliability. This means talking with other family members, roommates, and care staff and, of course, the occupational therapist’s own observations.40

The functional evaluation of an individual with AD depends on the stage of cognitive decline.10 The American Occupational Therapy Association’s statement on services for persons with AD suggests that tasks involving work, home management, driving skills, and safety should be targeted in the early stages of the disease. In the later stages, the focus shifts to self-care, mobility, communication, and leisure skills.

The concerns and observations of the caregiver are important, but observation of task performance by the therapist is also necessary. Unfortunately, many of the functional ADL scales developed for use in older adults have targeted physical performance and are not appropriate for persons experiencing cognitive decline.73 Fortunately, several excellent, standardized measures that determine whether individuals are able to use their cognitive skills to perform ADL and IADL tasks have been developed over the last 15 years. The Kitchen Task Assessment determines the level of cognitive support that a person with AD needs to complete a cooking task successfully.22 More recently, Baum and colleagues compiled the Executive Function Performance Test,24 a performance-based standardized assessment of cognitive function that has been standardized in administration and scoring.2 The Allen Cognitive Level (ACL) test determines the quality of problem solving that an individual uses while engaged in perceptual motor tasks.2 Levy has written at great length about use of the ACL test for clients with cognitive impairments.115,116 Consistent with the Allen theoretic approach, the Cognitive Performance Test was developed to identify cognitive deficits that are predictive of functional capacity by using several ADL and IADL tasks.3,37 Another measure, the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS), has been used in individuals who have dementia.63,158 The AMPS measures motor (e.g., posture, mobility, and strength) and process (e.g., attentional, organizational, and adaptive) skills by using task performance in IADLs. The Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD) uses informant ratings to determine the ability of an individual with AD to complete tasks in both ADLs and IADLs.73 The DAD also provides information relevant to executive functioning, such as the person’s ability to initiate, plan, and execute the activity. The Independent Living Scales was originally developed to assess older adults and assist in making a determination of an individual’s problem solving and performance as applied to memory and orientation, money management, home maintenance and transportation, health and safety, and social development.120 Further information regarding the evaluation of cognitive function and ADL performance is provided in Chapters 10 and 26. After obtaining a thorough evaluation and a good understanding of the disease process and the functional level of the person with AD, the therapist can begin to look at the all-important question of what aspects of the occupational performance context, especially the environment and care provider interactions, must be modified to optimize safety, function, and quality of life of the person with AD.158

Intervention Methods

The goals of OT are to provide services to persons with dementia and their families and caregivers that emphasize remaining strengths, maintain physical and mental activity for as long as possible, decrease caregiver stress, and keep the person in the least restrictive setting possible.12,14,89,101 Although AD is the primary problem, the occupational therapist has to consider the complexities of making interventions in an older adult who may be experiencing additional sensory loss and numerous medical problems such as arthritis, orthopedic issues, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and heart disease in addition to AD. Intervention planning takes into account the physical issues associated with aging, co-occurring disorders such as depression and anxiety, the progressive nature of the disorder, the expected decline in function, and the care setting itself. OT interventions for clients with dementia are directed toward maintaining, restoring, or improving functional capacity; promoting participation in occupations that are satisfying and that optimize health and well-being; and easing the burdens of caregiving.21 Gitlin and colleagues recently instituted a program to improve the overall pleasure of persons living at home who have dementia.78 This program was designed to decrease the distress of caregivers when caring for a person with AD who exhibits erratic and disturbing behavior. A program called the Tailored Activity Program (TAP) is an OT service that evaluates the interests and capabilities of a person with dementia and provides customized activities for each individual. TAP then trains families to use these activities as part of the daily care routines. Caregivers reported “being less upset with the behavioral symptoms” when using the tailored activities (p. 428). Methods that therapists use in the intervention process include activity analysis, caregiver training, behavior management techniques, environmental modification, use of purposeful activity, and provision of resources and referrals. Services are provided in many different settings, such as home care, adult day care, and semi-institutional or institutional long-term care. The intervention setting and the stage of the illness help frame the focus of intervention, determine the recipients of service, and prescribe the methods used (see Table 35-3). A useful role for an occupational therapist working with an individual with dementia and his or her family is to assist the individual with AD in making the many transitions that will probably take place—from home to hospital to assisted living, residential care, or skilled nursing home—as the disease progresses, as well as medical problems that bring about crises. With each move to a new residential setting the therapist can determine the interrelationship of the client’s physical, cognitive, sensory, and social world. OT can be instrumental in determining how this newest transition might influence occupational performance, health, and well-being. At each transition, interventions can target arriving at the best person-environment fit, recommending environmental adaptations, providing assistive devices, and promoting collaborative relationships between care providers to support occupational engagement and desired roles while enabling independence and safety at each transition79

Summary

AD is a neurologic condition characterized by the gradual development of multiple cognitive impairments. The effect of these impairments is a significant and progressive decline from previous levels of functioning. The course of the disorder is variable, but loss of function generally occurs in a hierarchic pattern, beginning with work and progressing to difficulties with home management, driving, and safety, until even basic self-care skills such as dressing, functional mobility, toileting, communication, and feeding are affected.

OT interventions should be directed at enhancing the abilities of a client with AD by continually adapting tasks of daily living and modifying the physical and social environment as the client experiences progressive loss of function. Given many of the current limitations in treatment time imposed by third party payment, therapists may find it helpful to use some of the self-report and informant report measures identified in this chapter as a means of gathering information more efficiently during the evaluation process. Several standardized measures have also been identified to assist in the assessment of functional performance and establishment of a baseline of performance. Recommendations for OT treatment of AD have been identified. The focus of intervention must be flexible and depends on an understanding of the particular expression of the disease process in the client, the specific treatment setting, and the needs of the caregiver. Generally, the goals of OT services for persons with dementia are to maintain or enhance function, promote continued participation in meaningful occupation, optimize health and quality of life, and work collaboratively with the caregiver to ease the burden of caregiving.

Section 3 Huntington’s Disease

Incidence

HD is a fatal, degenerative neurologic disorder that affects 5 to 10 of every 100,000 individuals.76,167 The disorder is transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern. Each offspring of an affected parent has a 50% chance of having HD. Genetic studies have identified a mutation on chromosome 4 as the cause of this disease.144,167,176,180 Presymptomatic diagnosis of HD is possible with genetic testing when the family history shows this disease.165,167 Diagnosis is also made through clinical examination when the family history is unavailable or unknown.

Pathophysiology

The neurologic structure associated with HD is the corpus striatum. Deterioration of the caudate nucleus is more severe and occurs earlier than atrophy of the putamen.44,163 The corpus striatum plays an important role in motor control, and deterioration in this area contributes to the chorea associated with HD. The caudate nucleus is also linked to cognitive and emotional function through connections with the cerebral cortex. Progressive loss of tissue occurs in the frontal cortex, globus pallidus, and thalamus as the disease advances.167 Degeneration of the corpus striatum results in a decrease in the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid. Additional deficiencies in acetylcholine and substance P, both neurotransmitters, are noted in clients with HD. The triggering mechanism for the neuronal degeneration has not been clearly identified, but it is linked to genetic coding on chromosome 4.180

Clinical Picture

HD is characterized by progressive disorders in both voluntary and involuntary movement, in addition to a significant deterioration in cognitive and behavioral abilities.167,200 A client usually experiences an insidious onset of symptoms in the third to fourth decade of life, but cases have been reported in teenage and younger clients.224 Clients who are positively identified by genetic testing should be carefully monitored for the first indications of HD symptoms. Not all individuals who have potential for the development of HD because of a family history have elected to undergo genetic testing, a fact that may affect determination of the time at which the first symptoms emerged. The course of progression of HD is often divided into three stages—early, middle, and late—but with the advent of genetic testing, an additional presymptomatic stage has been added.221 During the presymptomatic stage, monitoring of symptoms is critical, and a decrease in the speed of finger tapping (an item on the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale [UHDRS]) may mark the beginning of the early stage of HD. The symptoms progress over a 15- to 20-year period, with long-term care or hospitalization of the client ultimately being necessary.167,203 Death is often the result of secondary causes, such as pneumonia.165

The initial symptoms vary but are most often reported as alterations in behavior, changes in cognitive function, and choreiform movements of the hands.221,224 The early symptoms of cognitive disturbances are most likely related to degeneration of the caudate nucleus. The client may appear forgetful or display difficulty concentrating. During the early stages of HD a client may have difficulty maintaining adequate work performance. Family members frequently identify the initial behavioral changes seen in a person with HD as increased irritability or depression. Irritability and depression may be attributed inappropriately to the decline in work performance rather than to the disease process. Emotional and behavioral changes are often the earliest symptoms of HD.17,66 Chorea, seen in clients with HD, consists of rapid, involuntary, irregular movements.166 During the early stages of HD, chorea is often limited to the hands. A client may mask the initial chorea by engaging in behavior such as manipulating small objects with the hands. These irregular movements are exacerbated during stressful conditions and decrease during voluntary motor activities in the early stages of HD. Chorea is absent when the client is sleeping. Onset of HD in the teenage years is associated more frequently with early symptoms of rigidity rather than chorea.221,224

Cognitive and emotional abilities progressively deteriorate over the course of the disease.224 Disturbances in memory and decision-making skills become more apparent during the middle stages of HD. Establishing and maintaining meaningful habits and routines for an individual who has HD are important ways to support continued participation in occupational pursuits. A client may be able to complete familiar tasks at work or in the home, but if the environment is changed or if additional demands are placed on the individual, task performance is significantly compromised. Further deterioration in cognitive abilities in a person with HD may result in dismissal from employment. The cognitive deficits most frequently associated with HD are problems involving mental calculations, performance of sequential tasks, and memory.66 Verbal comprehension is often spared until the middle or later stages of the disease, and even then, dysarthria is a more significant issue than difficulty in comprehension until the late stage of HD.

As HD progresses, depression often worsens and suicide is not uncommon.221,224 Clients with HD are frequently hospitalized because of various psychiatric problems, including depression, emotional lability, and behavioral outbursts. Although the loss of function may contribute to the client’s level of depression, depression is clearly identified as a specific characteristic of HD.66,143 This affective disorder is frequently treated with various antidepressants. Periods of mania have also been reported in approximately 10% of individuals with HD.

As the disease progresses, the chorea becomes more severe and may involve the entire body, including the face.167 Disturbances in gait are often observed during the middle stages of the disease, and balance is frequently compromised.66 An individual with HD may display a wide-based gait pattern and have difficulty walking on uneven terrain. This staggering gait is at times misinterpreted by others in the client’s life as evidence of alcoholism.166 The client also has progressive difficulty in performing voluntary movements.167 Performance of voluntary motor tasks is slowed (bradykinesia), and initiation of movement is compromised (akinesia). Although handwriting ability may be spared initially, the client displays increasing difficulty with this task as the disease progresses. Letter size is enlarged, and letter formation, such as slant and shape, is distorted. Saccadic eye movements and ocular pursuits may be slowed at this stage of HD.165 Slight dysarthria compromising communication may be noted.66 Dysphagia occurs, and the client may choke on various foods. Difficulty may be noted in coordination of both chewing and breathing while eating.

In the later stages of HD, choreiform movements may be reduced because of further deterioration of the corpus striatum and globus pallidus.167 Hypertonicity and rigidity often replace the chorea as the disease progresses, and the client experiences a severe reduction in voluntary movements. Severe difficulties in eye movement are common during the final stage of the disease.165 At this stage the client often needs significant support from others or resides in a long-term care facility. The client is usually unable to talk, walk, or perform basic ADLs without significant assistance.144

Medical Management

Medical management of clients with HD can address the symptoms, but no effective course of treatment has been identified to arrest progression of this disease.179 Intervention based on replacing the deficient neurotransmitters has not been effective in changing the course or rate of progression of HD. Tricyclic antidepressants are often used to treat the depression seen in clients with HD, but monoamine oxidase inhibitors are contraindicated because of possible exacerbation of chorea.224 Haloperidol may be used to decrease the negative effects of chorea on the performance of functional activities.167 Haloperidol is prescribed cautiously and only when the chorea significantly compromises a person’s daily activities. Medical management is focused on three areas: managing symptoms and reducing the burden of the symptoms, maximizing function, and providing education to the client and significant others regarding the course of progression of the disease.143 A team of professionals, including an occupational therapist, is advocated when working with a client who has HD.

A team of various medical professionals is needed to support an individual with HD, as well as family members and significant others in the client’s life.92,102 Perception of the illness experience and the coping strategies used by a client with HD are an important part of the overall medical services provided.92 Likewise, the significant others in the client’s life need support and guidance in developing coping strategies as their loved one who has HD experiences progressive deterioration.102

Systematic evaluation of a client with HD must be performed at regular intervals to identify the rate of symptom progression and modify intervention strategies. Standardized instruments are available for determining the presence and severity of various symptoms.96,200 One evaluation tool, the UHDRS, combines aspects from several instruments into a scale that can be administered within 30 minutes. The UHDRS is often administered by a team. This tool provides an accurate means of determining a change in the areas of “motor function, cognitive function, behavioral abnormalities, and functional capacity.”96 The UHDRS has been used to assess the rate of decline and demonstrates good reliability (Klempir et al, 2006). The occupational therapist should perform additional assessments before an intervention plan is developed. An evaluation would address functional daily living skills; cognitive abilities such as problem solving, motor performance, and strength; and personal interests and values. The occupational therapist must consider the client’s role within the family and community and incorporate these data into the intervention plan. An evaluation at both the home and work site would provide needed information that could be modified if necessary.

Role of the Occupational Therapist

The role of the OT practitioner varies depending on the stage of the disease.98 During the early stages of HD, an occupational therapist should address the cognitive components of memory and concentration. A client may still be employed at this stage. Strategies such as establishment of a daily routine, use of checklists, and task analysis to break tasks down into manageable steps can be very helpful. These strategies provide the external structure and support needed to help a person with HD maintain functional abilities at both the workplace and home. A work site evaluation can identify changes that would allow a person with HD to continue working. Modifications may include the use of tools such as organizers, electronic planners, and reminders to prompt an individual to complete regularly occurring tasks in the workplace. Family members should also be instructed in the use of these techniques. Environmental modifications such as providing a quiet workplace and reducing extraneous stimuli will decrease the impact of compromised memory and concentration on performing functional tasks in the workplace. Even during the early stages, work performance may deteriorate and the client may be dismissed because of an inability to meet the job essentials. This increases the stress experienced by the client from a financial perspective and from loss of a role as a worker.

Psychologic issues during this stage of the disease frequently include anxiety, depression, and irritability.66,90 A client may express guilt that any of his or her children have a 50% chance of HD developing.166 The diagnosis of HD is often not confirmed until a person is 30 to 40 years old unless genetic testing is performed and confirms HD. The client may already be married and have children by that time. Decisions whether children should undergo complete predictive genetic testing may be a significant stressor for a client with HD and for his or her family members. As mentioned previously, not all individuals elect to be genetically tested, and sporadic cases of HD do arise when no family member has HD. During this early stage of HD, clients may use denial as a coping strategy even though choreiform movements are present in the hands.92

Maintaining social contacts and engaging in purposeful activities are important in designing interventions for clients with HD.166 Changes in cognitive abilities and unpredictable or exaggerated emotional responses may result in the loss of a job and decreased income for the family, even during this early stage of the disease.66 This additional stress should also be considered when developing an intervention plan. The OT intervention plan must include community support services for clients with HD. OT services should include providing clients with information regarding support groups, opportunities to engage in community activities, and connecting with virtual resources through the Internet.

The motor disturbances during the early stages of HD are usually limited to fine motor coordination problems.66 The characteristic chorea may be noticed only as a twitching of the hands when the client is anxious. OT should provide modifications to diminish the effect of chorea and fine motor incoordination on performance of functional activities.98 This would include modifications in clothing and selection of clothing that does not require small fasteners such as small buttons, snaps, or hooks. Shoes with Velcro or elastic closure are recommended to compensate for diminished fine motor skills. Home modifications should be instituted at this stage to allow a client with HD to become familiar with the changes. Developing the skills for using adaptive equipment or modifications and then converting these skills into habits are critical during the early stage of HD. Typical modifications are the use of cooking and eating utensils with built-up handles, unbreakable dishes, a shower bench or seat with tub safety bars, and sturdy chairs with high backs and armrests. Throw or scatter rugs should be eliminated wherever possible in the home, and walkways should be kept free of clutter. The occupational therapist should establish a home exercise program with the client to address flexibility and endurance of the entire body. These exercises will be incorporated into the client’s daily routine. As the movement disorder progresses with increased chorea and difficulty in oculomotor control, the client will no longer be able to safely drive a car, and further loss of community mobility may be experienced. This further loss of independent function and control must be considered within the OT intervention plan. Alternative methods of community mobility must be explored.

As HD progresses, the role of OT changes to meet the client’s needs.98 During the middle stages of HD, further deterioration in cognitive abilities often requires the person to resign from a job. Engagement in purposeful activities is greatly needed at this stage and should be a focus of the OT intervention plan.90,166 Decision-making and arithmetic skills show further deterioration, and family members may need to arrange for others to handle the client’s financial matters.66,147 Generally, comprehension of verbal information is better preserved than the ability to perform sequential tasks during this stage. The occupational therapist should encourage the family to use simple written cues or words to help a family member with HD complete self-care and simple household activities. For example, selecting clothing items for a person with HD and placing the clothes in a highly visible area can provide the prompt to change from pajamas to clothes in the morning. Arranging the bathroom with visual cues, such as putting the toothpaste and toothbrush by the sink, can remind the client to brush his or her teeth in the morning and evening.

During the middle stage of HD, the client may display increasing levels of irritability and depression.224 Clients with HD may attempt suicide. The OT intervention plan should focus on the client’s engagement in purposeful activities, particularly leisure activities. When selecting craft activities, the therapist should always consider the client’s interests but should also strive to ensure that no sharp instruments are required.90,147 Modification of craft activities allows a client with HD to successfully complete a task with minimal support.31 Materials often require additional stabilization to compensate for the client’s movement disorders, and any tools used in the leisure activity, such as a wood sander and paintbrushes, should have enlarged or built-up handles.

Motor problems become more apparent during the middle stage of HD and necessitate further modifications in daily living tasks.98,200 The client’s compromised balance may require that tasks such as dressing, brushing teeth, shaving, and combing hair be performed while the client is seated. The client may require the use of a walker or wheelchair at this stage. A Rollator Walker is preferred over a standard walker without wheels. The walker may need to be fitted with forearm supports to provide additional support when the client is ambulating. Once a wheelchair becomes necessary, it should have a firm back and seat; however, additional padding is often required on the armrests because of the client’s chorea. Many clients with HD are better able to move the wheelchair with their feet than with their hands. The height of the wheelchair seat should be adjusted to allow clients to use their feet to move the chair if possible.

Fatigue is a common issue during the middle stage of HD and can be addressed by taking frequent breaks during the day. Breaks must be scheduled because a person with HD may not readily recognize fatigue. Clothing should have few or no fasteners, and shoes should be sturdy with low heels.147 Additional adapted equipment that may prove helpful for clients with HD includes shower mitts, electric razor or chemical hair removal method, covered mugs, and nonslip placemats.98 The choreic movements may become so severe that use of a bed with railings is necessary. Padding should be used on the railings, and additional cushions should be used on the bed.

Because of the excessive movements associated with chorea, clients with HD often need to consume 3000 to 5000 calories per day to maintain weight.147 Clients with HD display higher energy expenditure than do individuals without HD and consequently have issues with weight loss and difficulty maintaining appropriate weight.216 Smaller, high-calorie meals should be provided five times a day. This schedule may require additional support from family members or a personal care attendant. Dysphagia, poor postural control, and deficient fine motor coordination compromise the client’s ability to eat.98 Positioning during feeding is crucial, and the trunk should be well supported during mealtime. Clients with HD should be able to support their arms on the table while the feet are stabilized. The feet may be supported on the floor or wrapped around the legs of the chair for additional support. Problems with dysphagia can be addressed with positioning, oral motor exercises, and changes in diet consistency. Soft foods and thickened fluids are preferable to chewy foods, foods with mixed texture, and thin liquids. Nutritional support has been used successfully for clients with HD to maintain appropriate weight.216 Appropriate body weight is important to maintain overall health of clients with HD.

During the final stages of HD, the client often depends on others for all self-care tasks because of the lack of voluntary motor control.98,144 In some clients, the chorea may diminish and be replaced by rigidity. The occupational therapist provides important input on positioning and the use of splints to prevent contractures at this stage. Because of the risk for aspiration, oral feedings are provided by trained personnel; alternatively, the client may receive nutrition through a feeding tube.147 A combination of oral feedings and tube feedings may be used during this stage.

Although cognitive abilities continue to deteriorate, the level of functional decline is difficult to assess because of dysarthria and loss of motor control.66 Dementia is part of the HD profile and must be considered during development of the intervention plan. For example, a person in the late stage of HD may still recognize family members and enjoy watching television. The occupational therapist should explore the use of various environmental controls to allow the client control of and access to the immediate environment.16 Providing a touch pad or switch for selecting television channels may prove beneficial for the client.