Low Back Pain

Occupational therapy interventions

Activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, and other areas of occupation

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

2 Demonstrate how a neutral spine is integrated into a variety of activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

3 Demonstrate use of the “golfer’s lift” in performing an activity of daily living.

4 Identify the basic concepts of body mechanics.

5 Demonstrate the relationship between anatomy and body mechanics.

6 Articulate normal back anatomy in terms that a client can comprehend.

7 Identify the occupational therapist’s role in evaluation and intervention.

Low back pain (LBP) is a complaint that often causes the individual to seek help from the medical system. Four of five adults will experience significant LBP sometime during their lives. After the common cold, LBP is the most frequent cause of lost workdays in adults younger than 45 years. Most cases of LBP are not serious and respond to simple treatments such as rest or anti-inflammatory drugs. Common causes of LBP include poor conditioning, improper use of the back, obesity, smoking, age, and simple wear and tear over time. Osteoporosis, arthritis, fractures of the spine, and protruding disks are the most common causes of structural problems in the low back region. Before consulting a physician or occupational therapist, patients often seek help from chiropractors, massage therapists, acupuncturists, and proponents of the latest fads (e.g., magnets) to reduce the pain.

Spinal Anatomy

The occupational therapist must understand both normal anatomy and the pathology underlying numerous back problems. To educate the patient regarding the rationale for proper body mechanics, the occupational therapist must also understand how the anatomy and pathology are related to movement and daily occupations. Furthermore, the occupational therapist must be able to convey this information in a way that is accessible to clients with varying degrees of knowledge about anatomy and back pathology.

Vertebral Column

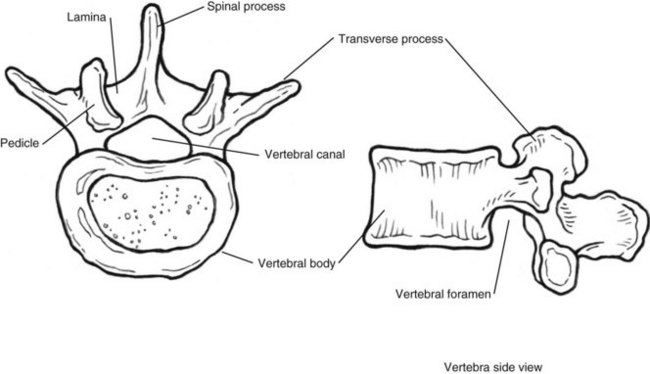

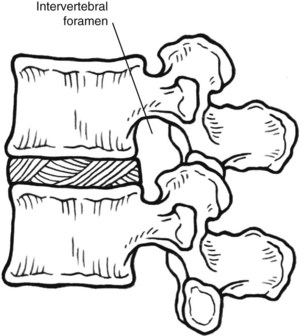

The structures that compose the vertebral column are the vertebrae and intervertebral disks. Each vertebra contains the vertebral body, which is the weight-bearing component, and the vertebral arch, which arises from the back of the vertebral body (Figure 41-1). The vertebral arch is composed of two pedicles (one on each side) that extend into the lamina. The laminae join together to form the vertebral foramina, which make up the vertebral canal in which the spinal cord resides. From the pedicle and joining of laminae are three bony projections called processes. These lateral processes join to form joints with adjacent vertebrae superiorly and inferiorly (Figure 41-2). Between the joint of these adjacent vertebrae is the intervertebral foramen, from which the spinal nerves enter and exit. At the back of the spinal arch is the spinous process, where muscles attach. The low back region is composed of five lumbar vertebrae.

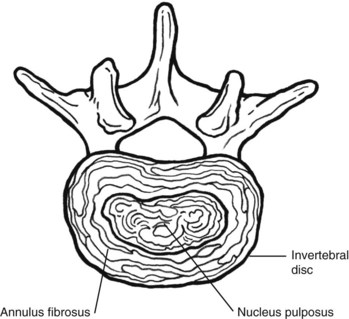

Between the vertebrae are intervertebral disks. The intervertebral disks are composed of fibrocartilage and a central mass of pulpy tissue, the nucleus pulposus (Figure 41-3).

Under pressure, the disk bulges. The disks work as shock absorbers and are relieved of pressure only when the body is supine. Being the nonrigid part of the column, they provide flexibility for movement. When a person is standing with a neutral spine, the disk is under uniform pressure. Movements such as bending, twisting, and reaching result in extension of the spine, and pressure on the disk may increase in one part of the back, whereas in another part of the back it may be under stretch (Figure 41-4).

Anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments extend the length of the vertebral column and are attached to the vertebral bodies and intervertebral disks. These ligaments check excessive movement of the column. The sacrum is the lower fused portion of the vertebral column and is attached to the pelvis. Movement of the pelvis changes the lordosis, or curve of the lower part of the spine.

Muscles of the lumbar spine include the intertransversarii and interspinalis, which are small intersegmental muscles that connect the transverse process to the spinous process of adjacent vertebrae. The lumbar multifidus, lumbar longissimus, and iliocostalis make up the lumbar muscles. These muscles are primarily extensors for the spine, but the lumbar longissimus and iliocostalis can also assist in lateral flexion. In addition, muscles of the abdominal wall contribute to stabilization of the spine, including the transversus abdominis and obliquus internus abdominis, by providing a corseting effect. For further information on interaction of the back and abdominal muscles during specific movements, the reader is advised to do additional reading in this area.

Incidence of Low Back Pain

LBP resolves within 6 weeks in 90% of clients. It resolves in 12 weeks in another 5%.1 “Less than 1% of back pain is due to ‘serious’ spinal disease (e.g., tumor, infection). Less than 1% of back pain stems from inflammatory disease, and less than 5% is true nerve root pain.”1 Typically, back pain is a result of poor physical fitness, obesity, reduced muscle strength and endurance, or use of poor body mechanics. Actual changes in the structure or mechanics of the lower part of the back may result in problems, including the following:

• Sciatic (nerve root) pain. The nerve is entrapped by a herniated disk.

• Spinal stenosis. Narrowing of the intervertebral foramen decreases the space where the spinal nerve exits or enters the spine.

• Facet joint pain. Inflammation or changes in the spinal joints cause facet joint pain.

• Spondylosis. This is a stress fracture of the dorsal to the transverse process.

• Spondylolisthesis. One vertebra slips on another.

• Herniated nucleus pulposus. Stress may tear fibers of the disk and result in an outward bulge of the enclosed nucleus pulposus. This bulge may press on spinal nerves and cause various symptoms, including nerve entrapment.

• Compression/stress fractures. These fractures are usually a result of osteoporosis and occur in the vertebrae.2

Rehabilitation

The best intervention for a client with LBP is a team approach using the skills of not only an occupational therapist but also a physician, physical therapist, caseworker, and psychologist. Depending on the circumstances of the client, other team members, such as the vocational counselor, social worker, discharge planner, nutritionist, and nurse, could be vital to successful intervention outcomes. These members may be part of the rehabilitation team, pain team, managed care group, and so forth.

The main member of this team, however, is the client. The client’s goals and desired outcome should direct the way in which the team approaches care. Each member must be aware of the context or contexts that will influence the client’s performance. This will affect the way that the client may or may not participate or take responsibility for his or her performance outcome.

Much has been written about workers and the effects of job satisfaction and limitations resulting from back pain. However, Waddell “asserts upon extensive review of the literature that ‘social class’ is probably the strongest personal predictor of incurring back trouble. This is in part due to heavy manual labor and in past due to ‘social disadvantages’ such as poor health care or lifestyle.”5 People who experience more anxiety with loss of work and the resulting financial implications frequently require the assistance of a psychologist. However, both these issues—decreased job satisfaction and anxiety—may surface during the patient’s occupational profile and should be addressed by all members of the team.

Physician

The physician is responsible for the initial work-up (or evaluation) of the client. Although the evaluation process varies according to the type of physician, the examination usually includes a thorough medical history, current symptoms and complaints, functional limitations, posture, gait, strength, reflexes and sensation, and past interventions for this problem. A diagnosis is usually made at this time, or the physician may order additional tests, such as nerve conduction tests, computed tomography scans, magnetic resonance imaging, and blood work. After arriving at a diagnosis, the physician often prescribes medication and determines restrictions in activity and exercise guidelines. To re-evaluate progress or lack thereof, the physician will typically see the patient in 1 or 2 weeks for a follow-up visit. If the symptoms have not decreased by that time, the client may be referred to physical therapy (PT).

During the client’s course of treatment, the skilled services of psychology, vocational counseling, and social work may be required. A low back injury may affect many areas of the client’s life significantly, including personal interactions, work, and finances; these consequences can increase the client’s stress and affect the outcome of treatment.

Physical Therapy

The client is usually referred to PT to address pain, spasms, limited flexibility, and posture. The PT evaluation generally includes a review of the mechanism of injury, date of injury, progression of symptoms, medical history, recent tests and procedures, medications, past treatment history, previous level of functioning, and the client’s goal for therapy. A subjective history of activities of daily living (ADLs) and sleep disturbances is reviewed. An objective examination will include analysis of posture, gait, active range of motion (ROM) of the spine, active ROM of the extremities, pelvic symmetry, signs of nerve tension, strength, reflexes and sensation, leg length, and palpation of soft tissue. On the basis of the data collected, the physical therapist develops a treatment plan that includes pain and spasm control, exercises, determination of the pelvic basis for daily activities, and patient education. The goals of PT are to reduce symptoms and increase strength and flexibility to achieve a functional pain-free outcome for the client.

A number of different theories are used by physical therapists. Two popular approaches are the McKenzie extension exercises and the Williams flexion exercises,1 but there are many others. For the purpose of this chapter, the dynamic lumbar stabilization (DLS) approach will be considered. Regardless of the approach or program used by the physical therapists with whom you work, additional knowledge of the theory and program is necessary to provide effective team communication and a satisfactory client outcome.4

Dynamic Lumbar Stabilization

DLS incorporates many PT theories, including flexion, extension, and body mechanics of the lower part of the back. DLS involves integration of the muscle groups that control movement of the spine and the abdominal muscles that support the back. The abdominal muscles act as a corset to support the lumbar area. These muscles can flex the lumbar spine by acting on the superficial portion of the dorsolumbar fascia. They can also extend the lumbar spine by acting on the deep portions of the fascia, which form the interspinal ligaments. Control of lordosis in flexion and extension is extremely important. Because repetitive loads applied to the lumbar intervertebral joint can lead to progressive tearing, fatigue, and ongoing disk prolapse, the client must learn to balance muscular function and flexibility to control the stresses involved in movement.

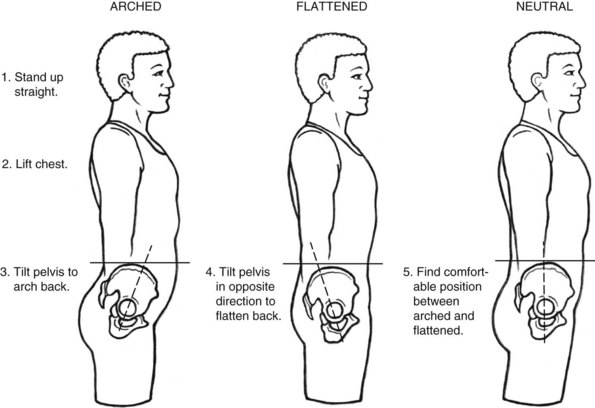

Each client must be able to identify his or her own “neutral position.” A neutral spine does not mean an absence of or no lordosis or curve of the lower part of the spine but rather refers to the most comfortable spinal position for the individual to complete movement patterns and then integrate this neutral position into daily occupations. The neutral position for each client is the condition in which the vertebrae and disks are under equal pressure.

To find the neutral position (called “finding neutral”), the client should stand with the knees slightly bent and the weight distributed evenly. Using the abdominal muscles to tilt the pelvis, the client should flex and extend the lumbar spine until the balanced position of optimal function and stability is attained (Figure 41-5). The abdominal muscles should be contracted to maintain this position, much as a corset would. This position or stabilization should be maintained and integrated into performance of the client’s occupations. Some individuals experience no pain while in a greater degree of extension or with a greater curve in the lower back region, whereas others prefer a neutral position of flexion and have more of a flattened abdomen.

FIGURE 41-5 Finding the neutral position. (Redrawn from Moore J, Long K, Von Korff M, et al: The back pain help book, Cambridge, Mass, 1999, Perseus Books Group.)

Clients who prefer a neutral position in extension find that extension of the back is beneficial in relieving pain generated from flexion, which is a result of impingement of the nerve as a result of narrowing of the foramen by arthritis or a disk problem. The focus is on extension exercises and low back positioning with a greater low back curve. This takes the pressure off the disk and places it on the facet joints, which allows the nucleus pulposus to migrate anteriorly away from the area of impingement. The neutral-with-flexion position is most commonly used with patients who have a posterior spine problem such as facet pain. Positioning the spine in flexion acts to reduce facet joint compression and places the pressure on the disk and vertebra body.

As a team member, the physical therapist will communicate the appropriate pelvic position for the client to the rest of the team. On the basis of the physical therapist’s recommendations for pelvic positioning, the occupational therapist will work with the client to incorporate the proper movement into daily occupations (Figure 41-6).

Occupational Therapy

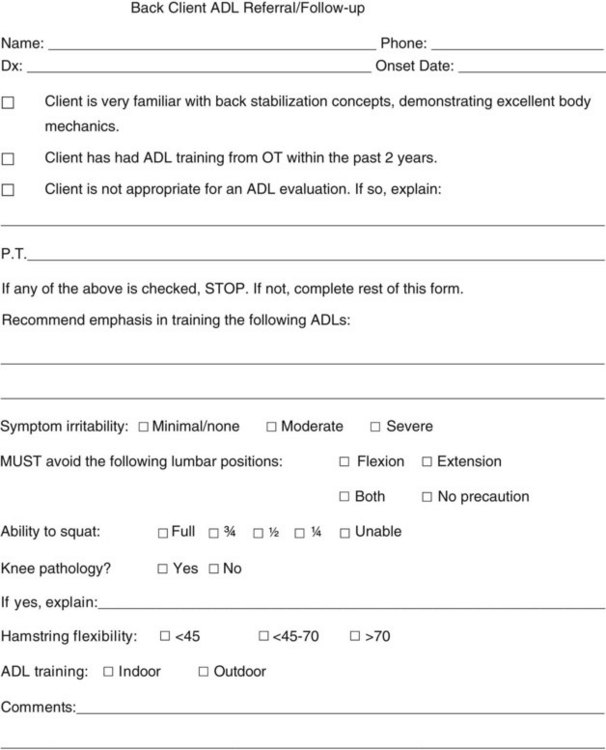

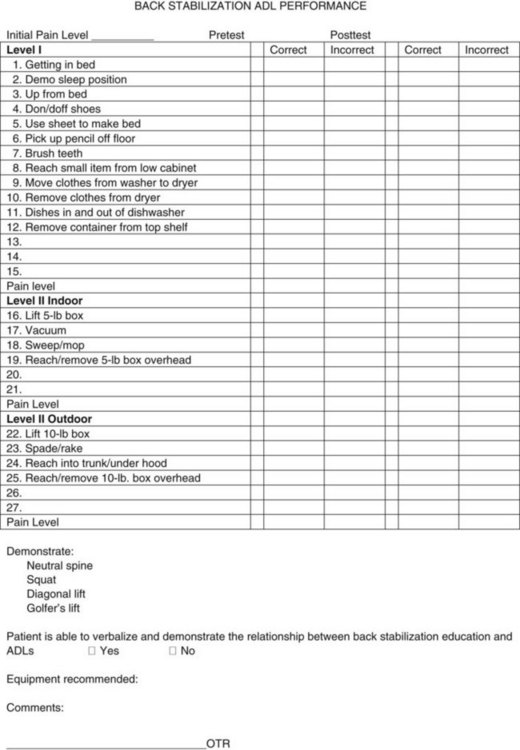

The occupational therapist will work with the client to develop an occupational profile. This is achieved by using an occupational self-report questionnaire and interview process. Filling out a questionnaire before the actual interview allows the client to begin to identify problem areas of occupation and stimulates conversation during the occupational profile. However, depending on the treatment setting, the client may regard the use of a questionnaire and subsequent review of the same material with the therapist as redundant and a waste of time. To develop a thorough occupational profile, performance areas that have been affected by back pain should be identified. Analysis of occupational performance can best be determined by actual performance. To structure the evaluation within the clinic setting, an obstacle course consisting of various ADLs and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) may be used to assess various performance skills within predetermined occupations (Figure 41-7). In addition, occupations identified as being problematic during the interview should be assessed in the same way.

FIGURE 41-7 Back stabilization, activity of daily living performance form. (Courtesy Eisenhower Medical Center, Rehabilitation Services, Rancho Mirage, Calif.)

Assessment of performance in specific problematic areas of occupation will help in formulating the intervention plan and outcomes. A combination of intervention methods will provide the best outcomes for the client. For the intervention plan to succeed, the therapist should discuss with the client anatomy, pathology, back stabilization, ergonomics, body mechanics, and pacing. The plan must incorporate education and demonstration of back protection techniques while the client is engaged in actual occupations. The most important part of this process is to have the client understand, practice, demonstrate, and then incorporate the learned information into current and new occupations. The education received and incorporated into performance of occupations by the client must become a habit to ensure pain-free living. The client’s outcomes will include reduction of pain, use of back stabilization techniques, use of adaptive equipment, and incorporation of body mechanics and ergonomics into client-specific areas of occupation, as well as the ability to adapt this learning to new occupations to prevent future problems.

Occupational Therapy Interventions

On the basis of the client’s evaluation, the therapist develops an intervention plan that may use any or all of the following:

• Education regarding normal back anatomy and the physiology of back movement as they relate to performance of occupations

• Use of neutral-spine back stabilization in occupational performance to reduce pain

• Education in basic body mechanics

• Training in the use of adaptive equipment to modify tasks

• Task analysis and use of ergonomic design to modify the environment

• Training in the use of energy conservation to maintain participation in occupation

• Use of occupations to increase strength and endurance

• Education in strategies for pain management, stress reduction, and coping.

Client Education

As described and reiterated throughout this chapter, client education seems to be the key to success for a client with LBP. Knowledge of basic anatomy and physiology helps the client understand what is occurring when movement while engaging in an occupation results in pain. This knowledge is the foundation on which to build the rest of the intervention plan and ultimately select the appropriate interventions. Education can be provided in both group and individual settings.

Back Stabilization and Neutral Spine

Before starting each activity, the occupational therapist should work with the client to identify his or her proper lower back position. It is important to monitor and cue the client as needed during the activity to maintain the proper position (see Figure 41-5).

In addition to a neutral spine, the client will need to learn and integrate a number of positions into activities to help in lifting and movement. These positions include the squat, diagonal lift, and golfer’s lift. The client’s ability to perform a squat requires an absence of any knee or hip pathology. While performing a squat, the client keeps the back straight while maintaining a neutral spine (Figure 41-8, A). A diagonal lift requires the lift to be performed with one foot in front of the other and the legs shoulder length apart (see Figure 41-8, B). A golfer’s lift requires bending at the hips while raising one leg behind (see Figure 41-8, C). Using a team method, the physical therapist identifies the client’s ability to squat, as well as the type of neutral spine. Proper analysis of specific ADLs and the best position for commencement of activities requires a thorough understanding of the client’s particular type of neutral spine, either flexion or extension.

FIGURE 41-8 A, Squat. Squat and lift with both arms held against the upper part of the trunk. Tighten the stomach muscles without holding your breath. Use smooth movements to avoid jerking. B, Diagonal lift. Squat down and bring the item close for lifting. C, Golfer’s lift. When reaching into the cart, lift the opposite leg to keep the back straight.

Body Mechanics

Thorough knowledge of the concepts of body mechanics by the client is critical for the use of back stabilization. These concepts include maintaining a straight back, bending from the hip, avoiding twisting, maintaining good posture, carrying objects close to the body, lifting with the legs to promote safe performance, and using a wide base of support. Another key concept that is incorporated into activities is reducing back stress while standing. Using a small stool or opening a cabinet door and resting the foot inside the cabinet base usually accomplishes this goal. Instruction in avoiding any twisting of the back during activities is also essential, as will be noted in many habitual activities, such as flushing the toilet. In these instances the client must be instructed to turn as a unit while maintaining a neutral spine.

Adaptive Equipment

Adaptive equipment is often useful. The most frequently recommended pieces of equipment for persons with LBP include long-handled sponges or brushes, reachers, long-handled shoehorns, sock aids, elevated commodes or toilet seats, hand-held shower sprayers, and footstools.

Ergonomics

Much has been done to create environments that better fit the individual needs of a person with LBP. For example, office chairs that permit height, back angle, and back height adjustments allow the user to fit the chair. A chair for desktop work must provide back support and maintain the hips and knees at 90 degrees with the feet flat on the floor or a footrest. The back of the chair should not be so far back that it cuts into the back of the legs or causes forward bending of the back and straining with the arms. The rest of the body position should allow the client to complete the desktop activity with proper positioning of the neck and upper extremities.

An analysis of the client’s work tasks should be completed and modifications made. In addition, the worker needs to change positions and take breaks. Occupational therapists and other specialists in ergonomics are available to provide consultation, as well as work site assessment and recommendations to employers, or to give the client information that allows him or her to complete a task analysis independently in the relevant environment. The Internet and office supply companies offer a great deal of information, in addition to products for the consumer.

Energy Conservation

Given their busy lives, clients may not realize that vacuuming, dusting, cleaning bathrooms, and preparing dinner for guests may be more than they—or their backs—can tolerate. Teaching clients the principles of energy conservation can help alleviate or minimize problems in this area. These principles include planning ahead, pacing oneself, setting priorities, eliminating unnecessary tasks, balancing activity with rest, and learning one’s activity tolerance.

Planning ahead, for example, might involve preparing portions of a meal ahead of time for company and freezing them so that they may be reheated. Pacing requires examination of the required task, the time frame for completion, and the individual’s ability to complete the task without resulting dysfunction. An example of pacing might include the recommendation that the client finish dusting a room in the morning and then vacuum in the afternoon instead of completing both tasks in one session. The principle of setting priorities might be illustrated by the client going out to dinner with company rather than preparing a large meal (cooking, serving, and cleaning); the former affords the client greater opportunity to enjoy the evening. The principle of eliminating unnecessary tasks might involve using paper towels for guests instead of cloth towels, which creates extra laundry. One example of balancing rest with an activity is to use a stool and sit while preparing food, thus resting the back while completing a task. Similarly, the therapist might suggest that the client complete grocery shopping in the morning and read in the afternoon to rest after the morning task. The key to success in incorporating energy conservation into one’s daily occupational life is for the client to be aware of his or her individual activity tolerance, including specific knowledge regarding triggers of fatigue and the amount of rest necessary for recovery.

Occupations to Increase Strength and Endurance

Once the principles of energy conservation have been taught and incorporated into several of the client’s occupations, it is important to build on that knowledge and enable the client to increase strength and endurance for engagement in more favored occupations. Given the opportunity to prepare a meal nightly, the client can soon develop the endurance to prepare a meal for guests. Sitting at a computer to write a letter while maintaining a neutral spine strengthens the abdominal muscles; it also increases the ability to sit in the car for a ride.

Strategies for Stress Reduction and Coping

Numerous methods can be used to promote stress reduction and coping, including relaxation techniques, deep breathing, meditation, prayer, and guided imagery. Avoiding frustration, managing angry feelings and negative thoughts, and most important, participating in meaningful daily occupations can help the client avoid stress that results in pain. In addition to the services provided by occupational therapists and other professionals, the local bookstore offers many self-help books addressing LBP.

The following sections describe specific areas of occupation that may be identified during the occupational profile and the type of back position that can be used to reduce back stress. It is important to begin by analyzing each occupation by using an approach such as the one described in the next section.

Analysis of Occupations

After the client has completed the occupational profile and identified specific problem areas, ask yourself the following questions:

• What is the normal movement in this activity? Analyze the activity.

Now plan for the way in which this intervention will be provided:

Activities of Daily Living, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, and Other Areas of Occupation

This section reviews specific areas of occupation that may be identified during the occupational profile and the type of back position that can be used to reduce back stress.

Bathing

For a person with LBP, a shower is usually better than a bath because it is easier to maintain a neutral spine while standing. It is also more difficult to get in and out of the tub safely.

One tip to make showering easier on the back is to keep all items within easy reach in the shower. Many types of racks that allow the client to place items below the showerhead are available for purchase. Long-handled scrub brushes or sponges allow washing of the back, legs, and feet without bending and twisting. A hand-held shower attachment also allows control of water flow and decreases unnecessary movements. With significant back pain, a shower chair can be used. A simple plastic lawn chair outfitted with nonskid safety feet will work well. If a client must use a tub, he or she could sit in a plastic chair and use a hand-held shower attachment. When sitting in the tub, the client should always use a bath mat to reduce the chance of slipping and drain the water before attempting to get out.

Dressing

The client should sit while dressing and keep the back straight or should lie flat on the bed while pulling clothing up. Clients should refrain from getting dressed while bending forward. To don and doff socks and shoes, the client should sit and bring the foot to rest on the knee. Clients who do not have good external rotation of the hip may place their feet on a stool while donning and doffing socks and shoes (Figure 41-10). Slip-on shoes are easier to use than lace-up shoes. A long-handled shoehorn is useful to assist in donning shoes that require tying. Similarly, the client can thread a belt through the belt loops before donning slacks to keep from twisting the back. Loose-fitting clothing is easier to put on than tight clothing. Back protection techniques should be used for both dressing and undressing.

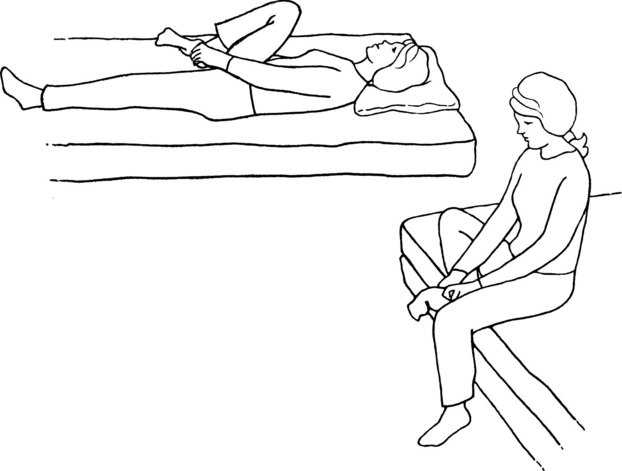

Functional Mobility

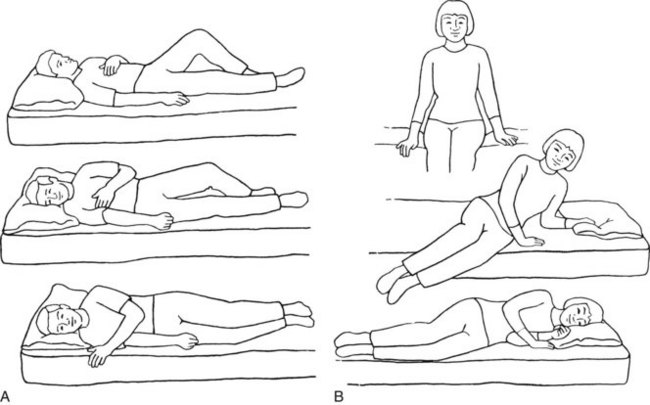

Use of a “logroll” to roll in bed requires movement of the body as a whole unit (Figure 41-11, A). To sit up or lie down, the client bends the knees and pushes up with the arms while coming to a sitting position (see Figure 41-11, B). To lie down, the client brings the legs up and uses the arms to lower the body to the bedside. For both movements, the client is instructed to lie down and bring the legs up while using the arms to lower the body to the bedside. During both movements, the client must keep the back straight and tighten the abdominal muscles to support the back.

FIGURE 41-11 A, Logroll. Lying on your back, bend your left knee and place your left arm across your chest. Roll all in one movement to the right. Reverse for rolling to the left. Always move as one unit. B, Movement in and out of bed. Lower your body to lie down on one side by raising your legs and lowering your head at the same time. Use your arms to assist in moving without twisting. Bend both knees to roll onto your back if desired. To sit up, start by lying on your side, and use the same movements in reverse. Keep your trunk aligned with your legs.

When getting on and off a toilet, the client must lower the body while maintaining a straight back and neutral spine. Supporting the hands on the thighs is helpful. Grab bars at the side of the toilet are also useful. However, grab bars must be secured properly and designed exclusively for this purpose; clients sometimes jeopardize their safety by using towel bars or tissue holders, which may cause further injury. In addition, clients sometimes grab a countertop on one side and the tub on the other, which results in twisting of the back or lateral flexion.

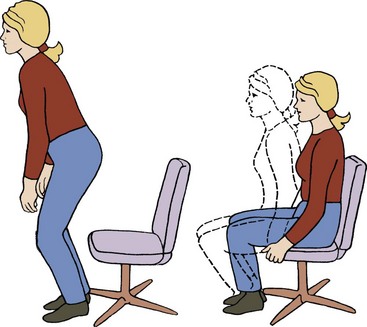

It is recommended that the client use a firm-armed chair that is supportive and not too low (rather than a soft couch). The client can use the chair arms to push up to a standing position (Figure 41-12). To reduce stiffness, the client should not sit longer than 15 or 20 minutes.

Personal Hygiene

Activities at a bathroom sink can be difficult because most sinks are designed to accommodate both children and adults; this low positioning forces most adults to bend forward, which places increased stress on the back structures. While brushing the teeth, shaving, or washing the face, the client should place a foot inside the base cabinet to reduce strain on the lower part of the back and bend from the hips while keeping the back straight (Figure 41-13). Alternatively, the client may bend forward and bear weight through one knee while extending a straight leg back for balance and support and maintaining a neutral spine position. To apply cosmetics, the client should use a hand-held mirror or a mirror that attaches to the wall so that the height can be adjusted.

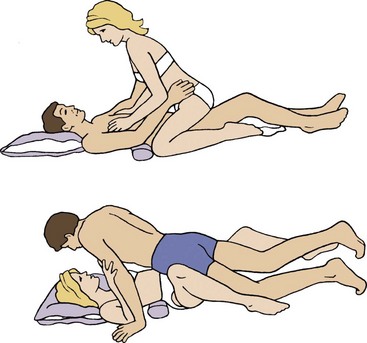

Sexual Activity

Sexual activities require positions that place the lower part of the back in the neutral position. Clients with back pain may be most comfortable taking a passive position on their back. Positioning pillows under the buttocks or upper part of the back may help reduce arching of the back. A rolled towel under the lower back region may also help maintain a neutral back position. In addition, the client is advised to start slowly and gradually work up to more vigorous movements. Stretching and warming up muscles may enable greater activity. Taking a warm shower or bath before sexual activity may also relax muscles and help reduce pain. A bit of planning will allow enjoyment of sexual activity (Figure 41-14).

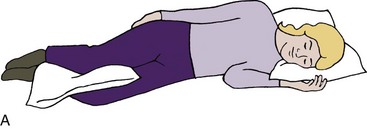

Sleep

We spend a third of our lives in bed, so it is important to consider the effects that being supine have on our backs. A firm, supportive mattress is important. The pillow should support the neck and head without causing the neck to flex. Many types of formed foam pillows are helpful. While sleeping on the back, the client should place a pillow under the knees to reduce strain on the lower part of the back and help maintain a balanced lower back position (Figure 41-15, A). While lying on the side, the client should place a pillow between the knees to keep the top leg from moving out of alignment and twisting the lower part of the back (see Figure 41-15, B). For some individuals, sleeping on the stomach is appropriate (see Figure 41-15, C). In this position, pillows would not be appropriate, but a small pillow under the feet to bend the ankles and knees will take stress off the lower back region.3 For additional information on sleep and rest please refer to Chapter 13.

FIGURE 41-15 A, Sleeping on the side. Place a pillow between your knees. Use cervical support under your neck and a roll around your waist as needed. B, Sleeping on the back. Place a pillow under your knees. A pillow with cervical support and a roll around the waist are also helpful. C, Sleeping on the stomach. If this is the only desirable sleep position, place a pillow under the lower part of your legs and under your stomach or chest as needed.

Toileting

When cleaning after toileting, the client should reach between the legs to avoid twisting the back. When turning to flush the toilet, the client should turn all the way around and face the toilet to flush it rather than twisting and reaching. During an acute episode of back pain, a toilet can be used by straddling the seat and facing the back of the toilet. This affords a wider base of support and also provides use of the toilet tank when coming to a standing position.

Child Care

Handling children requires special precautions for individuals with back pain. Sudden movements can increase the client’s pain and interfere with the ability to handle the child safely. Clients should use a changing table or elevated surface when dressing the child. Bathing can be performed in a kitchen sink or in a portable tub on an elevated surface. Many contemporary cribs have drop-down rails so that the client does not need to extend his or her arms to lift the child over the crib.

Always remind the client to bend at the hips and keep the back straight during all of these tasks. To lift a child from the ground, the client should squat down and bring the child close before standing up. As the child gets older, the client should ask the child to stand or sit on a chair or couch before being lifted. This decreases the distance that the child must be lifted and eliminates the need for the client to bend forward. To place a child in a car seat, the client should stand close to the car seat and keep the back straight (Figure 41-16).

Computer Use

Much has been written about the use of computers and their effect on the body. It is important to position work so that the client is facing forward and ensure that the body is in good alignment. The keyboard and monitor should be directly in front of the client. The top of the monitor should be approximately at eye level. Clients are instructed to use a proper work height and seat height with the feet flat on the floor, wrists in a neutral position with the forearms parallel to the floor, and the elbows at a 90-degree angle. If the client is using a laptop computer, the same guidelines should be used. Clients are taught to look at the screen by lowering their eyes rather than flexing their necks. In addition, clients are encouraged to stretch, take breaks, and change positions often. Document holders can assist in proper placement to prevent the need to twist the body. (See the previous section on ergonomics and Chapter 14 for additional information on seating.)

Driving

When getting in and out of a car, the client should sit on the seat and turn the body as a unit to keep from twisting. In some cars, this may require adjusting the seat to get in and out; the client should sit with the knees no higher than the hips. A small, rolled-up towel positioned in the lumbar area may be helpful. Most cars now allow adjustments in seat height, seat angle, seat position, and steering wheel angle. When riding for extended periods, the client should schedule rest breaks to change positions. For drivers with back pain, use of cruise control allows more frequent changes in position.

Home Establishment and Management

The client should organize all work spaces so that the equipment and materials needed for specific tasks are within the work area. For example, if the client is planning to bake cookies, flour, sugar, baking spices, bowls, and measuring cups should all be within reach. The mixer (if used regularly) should be on the counter to obviate the need for lifting and reaching. Work areas should allow flexion of the elbows and no bending or straining of the lower back region. Routinely used items in cabinets should be at reach overhead, and the client should not be required to extend the back or neck to retrieve them. Items in lower cabinets should allow easy access with a partial squat. Cabinets can be modified with slide-out shelves/drawers that allow easier access. Items that are used less frequently can be stored in hard-to-reach cabinets. To prepare meals, the client must work at a proper work space. The ideal height for most individuals allows comfortable work with the elbows bent at 90 degrees and above and below extension of the arms without extension of the back and neck or bending. The kitchen set-up should feature work areas in which the items needed for a particular task are within easy reach.

To remove clothing from the washer when doing laundry, the client should use a golfer’s lift to reach inside the machine (Figure 41-17). To place clothes in the dryer, the client is instructed to squat down and then load the dryer. To retrieve clothes, the client repeats the squat, removes the clothes, and places them in a basket that is positioned nearby. When carrying the basket, the client should hold it close to the body; the same is true while lifting the basket when coming from a squat to a standing position.

FIGURE 41-17 Laundry, unloading the wash. To unload small items at bottom of the washer, lift your leg opposite the arm used for reaching.

For ironing, it is recommended that the client raise the ironing board to the proper height, thus allowing the client to have the elbow flexed at 90 degrees, as well as providing adequate extension of the elbow to avoid twisting of the lower part of the back. While ironing, the client is instructed to rest one foot on a low stool to help reduce low back strain. Ironing can also be completed while sitting if the ironing board is lowered beforehand. Because of the adjustability of an ironing board, this surface can be used for many other activities, such as folding clothes and wrapping packages.

A long-handled brush or sponge is recommended to clean the bottom of a tub. Using a hand-held sprayer and a spray cleaner is easier than scrubbing and rinsing the surfaces. While vacuuming, clients should move their feet and legs rather than reach or bend forward. They are also cautioned to avoid twisting; when vacuuming under a table or chair, they should bend at the hips and knees to keep the back in a balanced position.

When mowing the lawn, the client should face forward and align the hips with the mower. The client should keep the back straight, the spine in a neutral position, and the abdominal muscles tight; take frequent breaks; and refrain from twisting. When using a shovel, the client should bend at the hips and knees rather than at the waist and keep the shovel and its load close to the body. The preferred method for emptying the shovel is to turn the entire body and keep the hips and shoulders in alignment while maintaining the load close to the body and facing the location to unload the shovel. None of these household activities should be attempted when the client is in an unstable condition with acute pain.

Shopping

When retrieving items from a lower shelf, the client should squat or go down on one knee while keeping the back straight. The shelf should be used as support when returning to a standing position. When items are located overhead, the client should get as close as possible and use one hand for support on the shelf. To use a shopping cart, the client should find his or her neutral spine position, which should cause the abdominal muscles to tighten. The client should stand up straight and push the cart with the elbows at the side. The force to move the cart should come from the legs and body, not the back. Use of a cart is preferable to carrying a basket, even for small loads. Clients can place items in the child’s portion of the cart rather than carry a basket in one hand, which puts uneven stress on the back. When unloading the cart, the client should use the golfer’s lift to retrieve items from the bottom. While carrying packages, the client should distribute the weight evenly between both arms to reduce uneven lateral bending on one side. Better yet, the client can carry packages close to the body and use both arms.

Work

The demands of jobs vary considerably. Many employers now have someone on staff to assess workstations and determine whether modifications can be made (see Chapter 14). In many cases, however, it is up to the individual worker to modify his or her work situation. Many improvements can be made by simply using correct lifting techniques, using the proper equipment for the job, pacing the activity, and asking for help.

Leisure

When reading, clients should sit in a supported chair, not curl up on a sofa. Tabletop hobbies such as sewing and building models require attention to table height, chair position, and positioning of the work items for the upper extremities; these positioning recommendations resemble those for computers. All these modifications will reduce uneven pulling and twisting of the body.

When traveling, the client should use a pull-type suitcase on wheels, which is easier on the back. Backpacks and fanny packs with light loads can also be used. Travelers are encouraged to pack lightly and take only what is needed for the trip. Checking luggage and having someone else carry the load instead of trying to lift items overhead are also recommended.

Gardening can be challenging for clients with back problems. Raised garden beds and container gardening are good options to reduce back strain. Many carts or moving seats can be purchased that allow safer back positioning when working at ground level. Knee pads make gardening in a kneeling position more comfortable. The gardener is cautioned to work only within his or her immediate reach to avoid bending forward or twisting.

Only a few of the many possible interventions have been described here. Each client and each occupation must be analyzed, and an individual intervention should be developed for each client. ADL body mechanics cards from Visual Health Information can be used to customize each program. This is a card file system from which cards can be selected and copied to develop interventions for each client according to his or her individual needs. Also available are many preprinted booklets and computer programs that may assist in client instruction. It is important to remember that most insurance companies do not cover adaptive equipment and that hospitals typically have large markups on vended equipment. Consequently, many clinics offer sample equipment for clients to try and provide community resources for equipment or consumer catalogs from vendors such as Sammons/Preston or North Coast Medical. Consumers should be made aware that many items once considered adaptive therapy equipment or ergonomic items are frequently available at a lower cost in discount stores.

Surgical Intervention

Recently, surgical treatment of back problems has undergone many advances. Current interventions include laminectomy, fusion, nerve decompression, disk dissection, vertebroplasty, and kyphoplasty. Surgical interventions are divided into two basic types: surgery that decompresses the nerve or stabilizes the spine to reduce pain. Surgeries that decompress the nerve open the transverse foramen and increase the space for exit of the spinal nerve and entrance to the spinal cord. Some surgeries may remove a structure, such as part of a disk or an osteophyte, which may create pressure on the nerve root. Stabilization can include the use of various pieces of hardware, such as screw, wires, rods, and bone grafts, to increase stability of the bony structures of the spine. In addition both vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty use a cement-like substance to stabilize compression/stress fractures. Kyphoplasty involves the use of a balloon that is placed in the fracture and, when inflated, helps restore height and reduce deformity before the cement is injected.2

Client precautions must be identified. Therapists should work with the physician to develop protocols or standards of care for specific surgeries. It is also important to identify the types of braces and other equipment that may be used for a specific surgery by a specific physician so that the occupational therapist can provide the expected instructions and precautions for use of the equipment in daily occupations. For example, one physician may allow a client to put a brace on while sitting at the bedside, whereas another physician may require the client to logroll into the brace and complete donning the brace before coming to a seated position. Frequently, braces will be ordered and fitted before surgery, and patients will have them at admission.

Postoperative Occupational Therapy Evaluation and Intervention

When seeing a client for the first time postoperatively, the occupational therapist should obtain the client’s history and occupational profile, as well as a description of his or her home environment to ascertain the types of modifications required for safety. During the occupational profile, ADL and IADL issues should be identified. As part of the home assessment, education in work simplification techniques, in conjunction with directive questions, helps the client identify further needs. Home modifications may include picking up rugs to prevent falls, increasing awareness of pets, and selecting a type of chair that is easy to get in and out of and that provides good support and fits the client. The therapist should also determine whether the home contains a standard toilet and shower and whether modifications are required.

Next, the therapist must educate the client in the required performance precautions for daily occupations; this should take place before even attempting to have the client get out of bed. This evaluation is somewhat contrary to customary practice in occupational therapy. In this situation, the therapist does not want to observe performance before the intervention. Instead, the primary focus is to educate and then cue the client through the process to avoid any improper positions or posture that creates stress on the surgical area. The outcome of occupational therapy intervention is to maintain a straight back, avoid twisting, and perform ADLs while safely incorporating back safety techniques and using adaptive equipment.

Postoperative Activities of Daily Living

While in the hospital, the most basic ADLs must be addressed initially. It is important to educate the client on proper positions for sleeping and have the client demonstrate the correct positions. The client will need to use the logroll for functional mobility in the bed. Proper methods are also taught for getting in and out of bed, in and out of a chair, and on and off a toilet; brushing teeth; washing the face; shaving; and dressing using the back protection techniques discussed earlier in this chapter. Clients are instructed to use adaptive equipment to prevent back stress in daily activities, including getting in and out of an automobile.

The hospital stay for these clients can be between 24 hours and 3 to 5 days, depending on the procedure and previous level of function. Most clients are discharged home. Because the client’s stay is so short, it is good to provide them with resources to help them should specific occupations be overlooked during the hospital stay. Some facilities develop educational materials that include basic body mechanics information, hints on ADLs, and anatomic and surgical information. Various publications include post-surgical back “dos and don’ts.” Many hospitals have computerized education programs that allow the provider to issue information on the surgical procedure and the resulting back precautions. Most insurance plans do not cover adaptive equipment such as reachers and long-handled sponges; however, this equipment is necessary to ensure a successful postoperative outcome. Raised commodes and shower chairs are not usually covered, but many clients purchase these items and have them delivered to their homes before discharge. To prepare the client for home and occupation modifications, many hospitals provide preoperative education classes.

Summary

Providing effective occupational therapy intervention for a client with LBP requires a good understanding of back anatomy and physiology. The ability to analyze daily occupations and determine how back positions are affected by the occupation is crucial in attaining a successful outcome. Good communication between all team members is important to achieve both reduction of symptoms and integration of knowledge to support the performance of meaningful occupations.

References

1. Brotzman, SB, Wilk, K. Clinical orthopaedic rehabilitation, ed 2. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2003.

2. Luo, J, Adams, M, Dolan, P. (2010). Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty can restore normal spine mechanics following osteoporotic vertebral fracture. J Osteopor. 2010;20:729257. [Jun].

3. Melnik, MS, Saunders, R, Saunders, HD. Self-help manual managing back pain. Bloomington, Minn: Educational Opportunities; 1989.

4. Nelson, DL, Ciriani, DJ, Thomas, JJ. Physical therapy and occupational therapy partners in rehabilitation for persons with movement impairments. Occup Ther Health Care. 2001;17:34.

5. Waddell, G. The back pain revolution. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

Cole, AJ, Herring, SA. The low back pain handbook: a practical guide for the primary care clinician. Philadelphia, Pa: Hanley & Belfus; 1997.

Larson, BA. Occupational therapy practice guidelines for adults with low back pain. Bethesda, Md: American Occupational Therapy Association; 1996.

Maxey, L, Magnusson, J. Rehabilitation for the postsurgical orthopedic patient. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2001.

Moore, J, Long, K, Von Korff, M, et al. The back pain help book. Cambridge, Mass: Perseus Books Group; 1999.