CHRONIC ULCERATIVE STOMATITIS

Chronic ulcerative stomatitis is another immune-mediated disorder that affects the oral mucosa. This condition was initially described in 1989, and slightly more than 40 cases have been reported. Although the precise pathogenetic mechanisms are unknown, these patients develop autoantibodies against a 70-kD nuclear protein that is very similar to p63 and may play a role in epithelial growth and differentiation.

The prevalence of this disease may be more common than is realized. Because of its clinical similarity to erosive lichen planus, it is possible that only a clinical diagnosis is made when an affected patient is encountered, and a biopsy is not performed. Even if a biopsy is done, the tissue is often submitted for routine light microscopy alone, and the direct immunofluorescence studies that are required for its diagnosis are not ordered. Distinction from lichen planus should be made because chronic ulcerative stomatitis typically does not respond as well to corticosteroid therapy, and just as is the case with lupus erythematosus, chronic ulcerative stomatitis often can be effectively treated using antimalarial drugs.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Chronic ulcerative stomatitis usually affects adult women, and the mean age at diagnosis is late in the sixth decade of life. The condition may appear as desquamative gingivitis, although ulcerations or erosions of the tongue or buccal mucosa are also quite common (Fig. 16-104). The ulcers are generally surrounded by patchy zones of erythema and streaky keratosis that somewhat resemble lichen planus, although classic striae formation is not evident. The ulcers heal without scarring and often migrate around the oral mucosa. As is typical with most immune-mediated conditions, the severity of the oral lesions tends to wax and wane. Fewer than 20% of affected patients will develop concurrent lichenoid skin lesions.

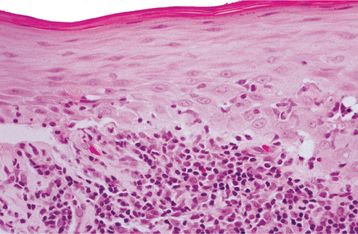

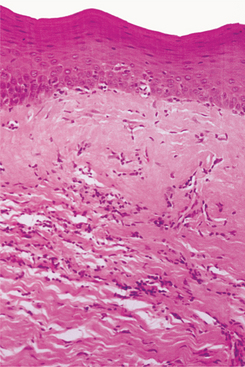

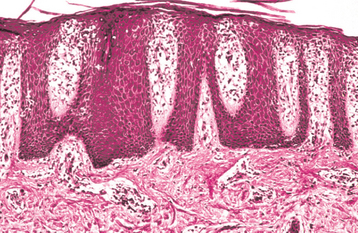

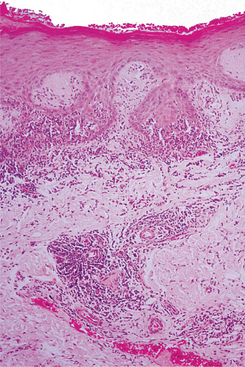

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Although the histopathologic features of chronic ulcerative stomatitis are similar to those of lichen planus, the epithelium is generally more atrophic and the inflammatory infiltrate usually contains significant numbers of plasma cells in addition to lymphocytes (Fig. 16-105). Artifactual epithelial separation from the underlying connective tissue is not unusual.

Fig. 16-105 Chronic ulcerative stomatitis. A, Low-power photomicrograph showing epithelial atrophy with a heavy chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the superficial lamina propria. B, High-power photomicrograph showing interface degeneration of the basilar epithelium in association with the inflammation. Unlike lichen planus, this infiltrate includes numerous plasma cells, as well as lymphocytes.

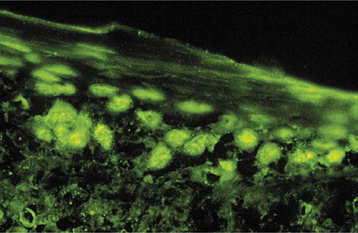

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of chronic ulcerative stomatitis is essentially based on its characteristic immunopathologic pattern. Although it may not be economically feasible to do immunologic testing on every case of lichen planus, this procedure should be considered for erosive lichenoid lesions that do not have a characteristic appearance or distribution, as well as for erosive lesions that do not respond to topical corticosteroid therapy. With direct immunofluorescence studies, autoanti-bodies (usually IgG) that are directed against the nuclei of stratified squamous epithelial cells in the basal and parabasal regions of the epithelium are detected (Fig. 16-106). Indirect immunofluorescence studies are also positive for these stratified epithelium-specific antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), and some investigators believe that confirmation of the diagnosis is necessary using serum for indirect immunofluorescence evaluation. Other immune-mediated conditions (e.g., systemic sclerosis and lupus erythematosus) may show ANA deposition with direct immunofluorescence; however, nuclei throughout the entire thickness of the epithelium are positive with those diseases.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Unlike the lesions of erosive lichen planus, the lesions associated with chronic ulcerative stomatitis may not respond as well to topical or systemic corticosteroid therapy. If the lesions are not adequately controlled with corticosteroids, then management with hydroxy chloroquine, an antimalarial drug, should be considered. Hydroxychloroquine therapy, however, requires both periodic ophthalmologic evaluation to monitor for drug-related retinopathy and periodic hematologic evaluation.

GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) occurs mainly in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplanta-tion, a procedure performed on approximately 4000 patients in the United States each year. Such transplants are performed at major medical centers to treat life-threatening diseases of the blood or bone marrow, such as leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, aplastic anemia, thalassemia, sickle cell anemia, or disseminated metastatic disease. Cytotoxic drugs, radiation, or both may be used to destroy the malignant cells, but in the process the normal hematopoietic cells of the patient are destroyed. To provide the patient with an immune system, an HLA-matched donor must be found. The donor supplies hematopoietic stem cells obtained from bone marrow, peripheral blood, or umbilical cord blood. These stem cells are transfused into the patient, whose own hematopoietic and immune cells have been destroyed. The transfused hematopoietic cells make their way to the recipient’s bone marrow and begin to reestablish normal function.

Unfortunately, the HLA match is not always exact, and despite the use of immunomodulating and immunosuppressive drugs, such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, and prednisone, the engrafted cells often recognize that they are not in their own environment. When this happens, these cells start attacking what they perceive as a foreign body. The result of this attack is GVHD, and it can be quite devastating to the patient.

In recent years, oncologists have taken advantage of this type of immunologic attack when treating leukemia patients, and often a beneficial “graft-versus-leukemia” effect is seen when the donor cells interpret the leukemic cells as being foreign. For older patients, who tend to have more significant side effects with traditional bone marrow transplantation, the concept of a “miniallograft” has been developed. Not all of the patient’s white blood cells (WBCs) are destroyed in this procedure, which is also known as nonmyeloablative allogenic hematopoietic cell transplantation, to allow the donor cells to mount a more aggressive assault on the patient’s leukemic cells.

Autologous stem cell transplantation has also become an increasingly popular method of treatment for some of these life-threatening diseases. Because these cells are derived from the patient, there is no risk of GVHD in this setting.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The systemic signs of GVHD are varied, depending on the organ system involved and whether the problem is acute or chronic. The severity of GVHD depends on several factors, with milder disease seen in patients who have a better histocompatibility match, are younger, have received cord blood, and are female.

Acute GVHD is typically observed within the first few weeks after bone marrow transplantation. Although acute GVHD has arbitrarily been defined as occurring within 100 days after the procedure, most investigators make this diagnosis based on the clinical features rather than a specific time point. The disease affects about 50% of bone marrow transplant patients. The skin lesions that develop may range from a mild rash to a diffuse severe sloughing that resembles toxic epidermal necrolysis (see page 777). These signs may be accompanied by diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and liver dysfunction.

Chronic GVHD may represent a continuation of a previously diagnosed case of acute GVHD, or it may develop later than 100 days after bone marrow transplantation, sometimes not appearing for several years after the procedure. Chronic GVHD can be expected to develop in 30% to 70% of bone marrow transplant recipients, and it often mimics any one of a variety of autoimmune conditions, such as systemic lupus ery-thematosus (SLE), Sjögren syndrome, or primary biliary cirrhosis. Skin involvement, which is the most common manifestation, may resemble lichen planus or even systemic sclerosis.

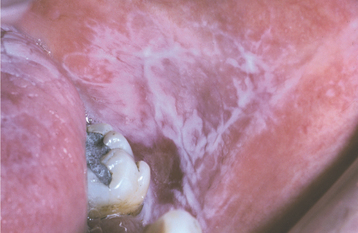

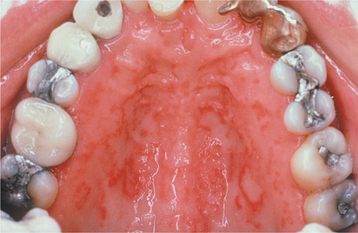

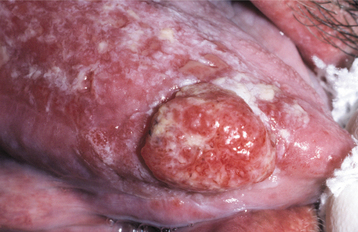

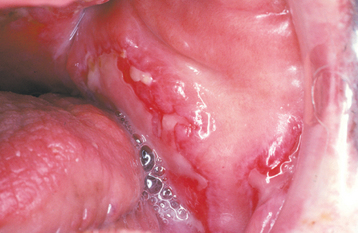

The oral mucosal manifestations of GVHD can also vary, depending on the duration and severity of the attack and the targeted oral tissues. Of patients with acute GVHD, 33% to 75% will have oral involvement; of patients with chronic GVHD, 80% or more will have oral lesions. Sometimes the oral lesions of GVHD are the only sign of the disorder. In most patients with oral GVHD, there is a fine, reticular network of white striae that resembles oral lichen planus, although a more diffuse pattern of pinpoint white papules has also been described (Figs. 16-107 to 16-109). The tongue, the labial mucosa, and the buccal mucosa are the oral mucosal sites most frequently involved. Patients often complain of a burning sensation of the oral mucosa, and care must be taken not to overlook possible candidiasis. Atrophy of the oral mucosa may be present, and this can contribute to the mucosal discomfort. Ulcerations that are related to the chemotherapeutic conditioning and neutropenic state of the patient often develop during the first 2 weeks after bone marrow transplantation. Ulcers that persist longer than 2 weeks may represent acute GVHD, and these should be differentiated from intraoral herpesvirus infection or bacterial infection. Bone marrow transplant patients have a small but increased risk for the development of both oral and cutaneous epithelial dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Demarcated white or red plaques of the oral mucosa that do not have the characteristic lichenoid features should be biopsied to rule out preneoplastic or neoplastic changes (Fig. 16-110).

Fig. 16-107 Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Confluent, interlacing white linear lesions of the vermilion zone superficially resemble oral lichen planus.

Fig. 16-109 Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Involvement of the tongue showing erosions and ulcerations that resemble erosive lichen planus.

Fig. 16-110 Squamous cell carcinoma arising in graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Erythematous, ulcerated mass arising on the lateral border of the tongue. Note the surrounding mucosal erosions, which represent GVHD.

Xerostomia is also a common complaint. If the patient is not taking drugs that dry the mouth, it is likely that the immunologic response is destroying the salivary gland tissue. Other evidence of salivary gland involvement includes the development of small superficial mucoceles, particularly on the soft palate.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic features of GVHD resemble those of oral lichen planus to a certain degree. Both lesions display hyperorthokeratosis, short and pointed rete ridges, and degeneration of the basal cell layer. The inflammatory response in GVHD is usually not as intense as in lichen planus. With advanced cases, an abnormal deposition of collagen is present, similar to the pattern in systemic sclerosis. Minor salivary gland tissue usually shows periductal inflammation in the early stages, with gradual acinar destruction and extensive periductal fibrosis appearing later.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of GVHD may be difficult because of the varied clinical manifestations. Such a diagnosis is of great clinical significance to the patient because complications of the condition and its treatment may be lethal. Although the diagnosis of GVHD is based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, each patient may have a different constellation of signs and symptoms. Oral lesions appear to have value as a highly predictive index of the presence of GVHD.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The primary strategy for dealing with GVHD is to reduce or prevent its occurrence. Careful tissue histocompatibility matching is performed, and the patient is given prophylactic therapy with immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents, such as prednisone in combination with either cyclosporine or tacrolimus. If GVHD develops, then the doses of these drugs may be increased or similar pharmacologic agents, such as mycophenolate mofetil, or azathioprine, may be added. The drug thalidomide has shown some promise for cases of chronic GVHD that have been resistant to standard therapy.

Topical corticosteroids may facilitate the healing of focal oral ulcerations associated with GVHD. Topical anesthetic agents are administered to pro-vide patient comfort while the lesions are present, although narcotic analgesics may be required in some cases. Several case reports have described the efficacy of topical tacrolimus for management of oral ulceration caused by GVHD. The use of psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy also has been shown to improve the cutaneous and oral lesions of patients with the lichenoid form of GVHD. If significant xerostomia is present in a dentulous patient, then topical fluorides should be used daily to prevent xerostomia-related caries. If significant amounts of salivary acinar tissue remain, then treatment with pilocarpine hydrochloride or cevimeline hydrochloride may improve the salivary flow. Current recommendations are to evaluate the oral status of patients before bone marrow transplantation and eliminate any potential sources of infection. Interestingly, one recent study showed no differences in posttransplant infections or survival between a group of patients who received dental treatment before their transplant and a group who did not.

In general, some degree of GVHD is expected in most allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients. The prognosis depends on the extent to which the condition progresses and whether or not it can be controlled. The significance of this complication is reflected in the survival of more than 70% of patients with relatively mild GVHD at 6 years posttransplant, compared with approximately 15% of patients with severe GVHD.

PSORIASIS

Psoriasis is a common chronic skin disease affecting approximately 2% of people in the United States. According to some estimates, roughly 6 million people in this country have psoriasis, and up to 250,000 new cases are diagnosed each year.

Psoriasis is characterized by an increased proliferative activity of the cutaneous keratinocytes. Recent advances in cell kinetics, immunology, and molecular biology have increased the understanding of the etiopathogenesis of the keratinocyte proliferation in this disorder. Although the triggering agent has yet to be identified, activated T lymphocytes appear to orchestrate a complex scenario that includes abnormal production of cytokines, adhesion molecules, chemotactic polypeptides, and growth factors. Genetic factors also seem to play a role, because as many as one third of these patients have affected relatives. Currently nine different genetic loci have been identified that may be related to the development of psoriasis. Yet, if one twin in a set of identical twins has psoriasis, there is only a 35% chance that the other twin will have it. This suggests that genetic factors are not entirely responsible for the condition, and that one or more uniden-tified environmental agents must influence its pathogenesis.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Psoriasis often has its onset during the second or third decade of life and tends to persist for years, with periods of exacerbation and quiescence. Patients often report that the lesions improve during the summer and worsen during the winter, an observation that may be related to lesional exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light. The lesions are often symmetrically distributed in certain favored locations, such as the scalp, elbows, and knees. The classic description is a well-demarcated, erythematous plaque with a silvery scale on its surface (Fig. 16-111). The lesions are often asymptomatic, but it is not unusual for a patient to complain of itching—in fact, the term psoriasis is derived from the Greek word for itching. An unfortunate complication affecting approximately 11% of these patients is psoriatic arthritis, which may involve the TMJ.

Fig. 16-111 Psoriasis. Characteristic cutaneous lesions on the skin of the elbow. Note the erythematous plaques surmounted by silvery keratotic scales.

Oral lesions may occur in patients with psoriasis, but they are distinctly uncommon. Because descriptions of these lesions have ranged from white plaques to red plaques to ulcerations, it is difficult to determine the true nature of intraoral psoriasis (Fig. 16-112). To render a diagnosis of intraoral psoriasis, some investigators say that the activity of the oral lesions should parallel that of the cutaneous lesions. Some authors refer to erythema migrans (see page 779) as intraoral psoriasis, and the prevalence of erythema migrans in psoriatic patients appears to be slightly greater than that seen in the rest of the population. It is difficult, however, to prove a direct correlation of that common mucosal alteration with psoriasis.

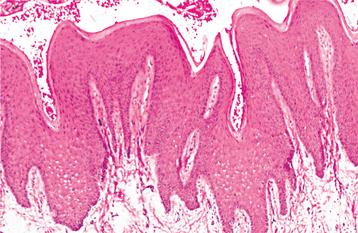

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopically, psoriasis has a characteristic pattern. The surface epithelium shows marked parakeratin production, and the epithelial rete ridges are elongated (Fig. 16-113). The connective tissue papillae, which contain dilated capillaries, approach close to the epithelial surface, and a perivascular chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate is present. In addition, collections of neutrophils (Munro abscesses), are seen within the parakeratin layer.

Fig. 16-113 Psoriasis. Low-power photomicrograph showing elongation of the rete ridges, hyperkeratosis, and inflammation of the papillary dermis.

With respect to oral lesions, good correlation with skin disease activity should be seen in addition to the characteristic histopathologic features, because other intraoral lesions, such as erythema migrans and oral mucosal cinnamon reaction (see page 352), exhibit a psoriasiform microscopic appearance.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of psoriasis depends on the severity of the disease activity. For mild lesions, no treatment may be necessary.

For moderate involvement, topical corticosteroids are commonly prescribed in the United States. Coal tar derivatives and keratolytic agents also may be used. Other topical drugs that have proven effective include calcipotriene, a vitamin D3 analog, and tazarotene, a retinoid (vitamin A) compound. Newer topical biologic agents include the calcineurin inhibitors, tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, although these are usually reserved for recalcitrant lesions. Exposure to UV radiation may also be helpful for mild to moderate disease.

For severe cases, psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy or ultraviolet B (UVB) therapy may be needed. Methotrexate or cyclosporine may also be used as systemic treatments for severe disease; however, these drugs have significant side effects. Newer systemic biologic agents that target specific disease-related components include infliximab and etanercept (directed against tumor necrosis factor-a [TNF-a]) or alefacept and efalizumab (directed against T-cell receptors).

Although the mortality rate is not increased in patients with psoriasis, the condition often persists for years despite therapy. Some studies have shown a modest increase in the risk for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in psoriasis patients, possibly related to their PUVA or methotrexate therapy.

LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Lupus erythematosus (LE) is a classic example of an immunologically mediated condition, and is the most common of the so-called collagen vascular or connective tissue diseases in the United States, with more than 1.5 million people affected. It may exhibit any one of several clinicopathologic forms.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a serious multisystem disease with a variety of cutaneous and oral manifestations. There is an increase in the activity of the humoral limb (B lymphocytes) of the immune system in conjunction with abnormal function of the T lymphocytes. Although genetic factors probably play a role in the pathogenesis of SLE, the precise cause is unknown. Undoubtedly, interplay between genetic and environmental factors occurs, for if SLE develops in one monozygotic (identical) twin, then the other twin has a 24% chance of having SLE as well. In contrast, if one dizygotic (fraternal) twin has SLE, then the other twin has only a 2% chance of being affected.

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) may represent a different, but related, process. It primarily affects the skin and oral mucosa, and the prognosis is good.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a third form of the disease, which has clinical features intermediate between those of SLE and CCLE.

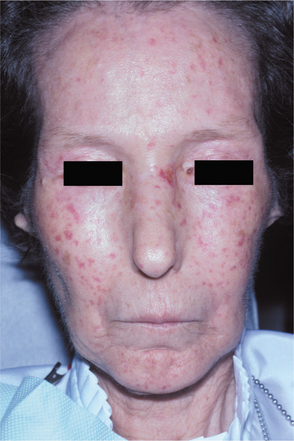

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS: SLE can be a very difficult disease to diagnose in its early stages because it often appears in a nonspecific, vague fashion, frequently with periods of remission or disease inactivity. Women are affected nearly 8 to 10 times more frequently than men. The average age at diagnosis is 31 years. Common findings include fever, weight loss, arthritis, fatigue, and general malaise. In 40% to 50% of affected patients, a characteristic rash, having the pattern of a butterfly, develops over the malar area and nose (Fig. 16-114), typically sparing the nasolabial folds. Sunlight often makes the lesions worse.

Fig. 16-114 Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The erythematous patches seen in the malar regions are a characteristic sign.

The kidneys are affected in approximately 40% to 50% of SLE patients. This complication may ultimately lead to kidney failure; thus it is typically the most significant aspect of the disease.

Cardiac involvement is also common, with pericarditis being the most frequent complication. At autopsy nearly 50% of SLE patients display warty vegetations affecting the heart valves (Libman-Sacks endocar-ditis). Its significance is debatable, although some patients may develop superimposed subacute bacterial endocarditis on these otherwise sterile outgrowths of fibrinoid material and connective tissue cells.

Oral lesions of SLE develop in 5% to 25% of these patients, although some studies indicate prevalence as high as 40%. The lesions usually affect the palate, buccal mucosa, and gingivae. Sometimes they appear as lichenoid areas, but they may also look nonspecific or even somewhat granulomatous (Fig. 16-115). Involve ment of the vermilion zone of the lower lip (lupus cheilitis) is sometimes seen. Varying degrees of ulceration, pain, erythema, and hyperkeratosis may be present. Other oral complaints such as xerostomia, stomatodynia, candidiasis, periodontal disease, and dysgeusia have been described, but the direct association of these problems with SLE remains to be proven.

Fig. 16-115 Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Irregularly shaped ulcerations of the buccal mucosa.

Confirming the diagnosis of SLE can often be difficult, particularly in the early stages. Criteria for making the diagnosis of SLE have been established by the American Rheumatism Association, and these include both clinical and laboratory findings (Table 16-4).

Table 16-4

Prevalence of Clinical and Laboratory Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| Findings | Affected Patients (%) |

| SYSTEMIC SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS: FATIGUE, MALAISE, FEVER, ANOREXIA, WEIGHT LOSS | 95% |

| MUSCULOSKELETAL SYMPTOMS | 95% |

| Arthralgia/myalgia | 95% |

| Nonerosive polyarthritis | 60% |

| CUTANEOUS SIGNS | 80% |

| Photosensitivity | 70% |

| Malar rash | 50% |

| Oral ulcers | 40% |

| Discoid rash | 20% |

| HEMATOLOGIC SIGNS | 85% |

| Anemia (chronic disease) | 70% |

| Leukopenia (<4000/μL) | 65% |

| Lymphopenia (<1500/μL) | 50% |

| Thrombocytopenia (<100,000/μL) | 15% |

| Hemolytic anemia | 10% |

| NEUROLOGIC SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | 60% |

| Cognitive disorder | 50% |

| Headache | 25% |

| Seizures | 20% |

| CARDIOPULMONARY SIGNS | 60% |

| Pleurisy, pericarditis, effusions | 30%-50% |

| Myocarditis, endocarditis | 10% |

| RENAL SIGNS | 30%-50% |

| Proteinuria >500 mg/24 hours, cellular casts | 30%-50% |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 25% |

| End-stage renal disease | 5%-10% |

Reproduced with permission of The McGraw-Hill Companies.

Adapted from Hahn BH: Systemic lupus erythematosus. In Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fanci AS et al, editors: Harrison’s principles of internal medicine, ed 16, pp 1960-1967, New York, 2005, McGraw-Hill.

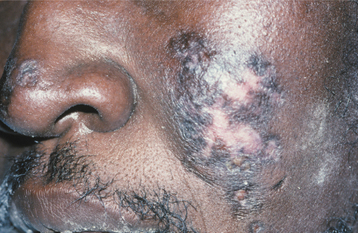

CHRONIC CUTANEOUS LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS: Patients with CCLE usually have few or no systemic signs or symptoms, with lesions being limited to skin or mucosal surfaces. The skin lesions of CCLE most commonly present as discoid lupus erythematosus. They begin as scaly, erythematous patches that are frequently distributed on sun-exposed skin, especially in the head and neck area (Fig. 16-116). Patients may indicate that the lesions are exacerbated by sun exposure. With time, the lesions may heal spontaneously in one area, only to appear in another area. The healing process usually results in cutaneous atrophy with scarring and hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation of the resolving lesion. Conjunctival involvement by CCLE has rarely been reported to cause cicatrizing conjunctivitis, clinically similar to mucous membrane pemphigoid.

Fig. 16-116 Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). The skin lesions are characterized by scaling, atrophy, and pigmentary disturbances, which are most evident on sun-exposed skin.

In most cases the oral manifestations of CCLE essentially appear clinically identical to the lesions of erosive lichen planus. Unlike the oral lesions of lichen planus, however, the oral lesions of CCLE seldom occur in the absence of skin lesions. An ulcerated or atrophic, erythematous central zone, surrounded by white, fine, radiating striae, characterizes the oral lesion of CCLE (Figs. 16-117 and 16-118). Sometimes the erythematous, atrophic central region of a lesion may show a fine stippling of white dots. As with erosive lichen planus, the ulcerative and atrophic oral lesions of CCLE may be painful, especially when exposed to acidic or salty foods.

SUBACUTE CUTANEOUS LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS: Patients with SCLE have clinical manifestations intermediate between those of SLE and CCLE. The skin lesions are the most prominent feature of this variation. They are characterized by photosensitivity and are, therefore, generally present in sun-exposed areas. These lesions do not show the induration and scarring seen with the skin lesions of CCLE. Usually, the renal or neurologic abnormalities associated with SLE are not present either, with most patients having arthritis or musculoskeletal problems. SCLE may be triggered by any one of a variety of medications (see page 347).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic features of the skin and oral lesions of the various forms of LE show some features in common but are different enough to warrant separate discussions.

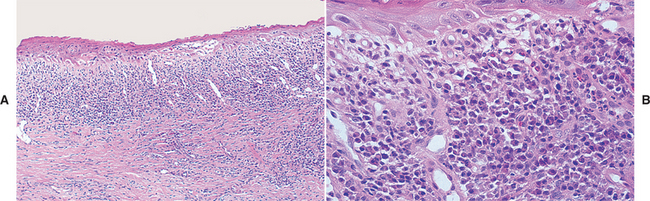

The skin lesions of CCLE are characterized by hyperkeratosis, often displaying keratin packed into the openings of hair follicles (“follicular plugging”). In all forms of LE, degeneration of the basal cell layer is frequently observed, and the underlying connective tissue supports patchy to dense aggregates of chronic inflammatory cells (Figs. 16-119 and 16-120). In the deeper connective tissue, the inflammatory infiltrate often surrounds the small blood vessels.

Fig. 16-119 Lupus erythematosus (LE). Low-power photomicrograph showing hyperparakeratosis with interface mucositis and perivascular inflammation.

The oral lesions demonstrate hyperkeratosis, alternating atrophy and thickening of the spinous cell layer, degeneration of the basal cell layer, and subepithelial lymphocytic infiltration. These features may also be seen in oral lichen planus; however, the two conditions can usually be distinguished by the presence in LE of patchy deposits of a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive material in the basement membrane zone, subepithelial edema (sometimes to the point of vesicle formation), and a more diffuse, deep inflammatory infiltrate, often in a perivascular orientation. Some authorities, however, feel that differentiating lichen planus from LE is best done by direct immunofluorescence studies or histopathologic examination of the cutaneous lesions.

DIAGNOSIS: In addition to the clinical and microscopic features, a number of additional immunologic studies may be helpful in making the diagnosis of LE.

Direct immunofluorescence testing of lesional tissue shows deposition of one or more immunoreactants (usually IgM, IgG, or C3) in a shaggy or granular band at the basement membrane zone. In addition, direct immunofluorescence testing of clinically normal skin of SLE patients often shows a similar deposition of IgG, IgM, or complement components. This finding is known as a positive lupus band test. Although a positive lupus band test is consistent with the diagnosis of LE, it is now known that other conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, and systemic sclerosis, may also have similar positive findings. Furthermore, some patients with LE may not have a positive lupus band test; therefore, this study must always be interpreted in the context of other clinical signs.

Evaluation of serum obtained from a patient with SLE shows various immunologic abnormalities. Approximately 95% of these patients have antibodies directed against multiple nuclear antigens (i.e., antinuclear antibodies [ANAs]). Although this is a nonspecific finding that may be seen in other autoimmune diseases, as well as in otherwise healthy older individuals, it is nevertheless useful as a screening study. Furthermore, if results are negative on multiple occasions, then the diagnosis of SLE should probably be doubted. Antibodies directed against double-stranded DNA are noted in 70% of patients with SLE, and these are more specific for the disease. Another 30% of patients show antibodies directed against Sm, a protein that is complexed with small nuclear RNA. This finding is very specific for SLE.

A summary of selected immunologic findings in LE is shown in Table 16-5.

Table 16-5

Selected Abnormal Immunologic Findings in Lupus Erythematosus

| Findings | Frequency | Significance |

| Direct immunofluorescence, lesional skin | CCLE: 90% | May help distinguish among the various types of LE |

| SLE: 95% | ||

| Direct immunofluorescence, normal skin | CCLE: 0% | Lupus band test |

| SLE: 25%-60% | ||

| Antinuclear antibodies | CCLE: 0%-10% | Very sensitive for SLE, but not very specific; not useful for CCLE diagnosis |

| SLE: 95% | ||

| Antidouble-stranded DNA antibodies | CCLE: 0% | Specific for SLE; may indicate disease activity or kidney involvement |

| SLE: 70%-80% | ||

| Anti-Sm antibodies | CCLE: 0% | Specific for SLE |

| SLE: 10%-30% |

CCLE, Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; LE, lupus erythematosus.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Patients with SLE should avoid excessive exposure to sunlight because ultraviolet light may precipitate disease activity. Mild active disease may be effectively managed using nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) combined with antimalarial drugs, such as hydroxychloroquine. For more severe, acute episodes that involve arthritis, pericarditis, thrombocytopenia, or nephritis, systemic corticosteroids are generally indicated; these may be combined with other immunosuppressive agents. If oral lesions are present, they typically respond to the systemic therapy.

As with SLE patients, patients with CCLE should avoid excessive sunlight exposure. Because most of the manifestations of CCLE are cutaneous, topical corticosteroids are often reasonably effective. For cases that are resistant to topical therapy, systemic antimalarial drugs or low-dose thalidomide may produce a response. Topical corticosteroids are also helpful in treating the oral lesions of CCLE.

The prognosis for the patient with SLE is variable. For patients undergoing treatment today, the 5-year survival rate is approximately 82% to 90%; however, by 20 years, the survival rate falls to 63% to 75%. Ultimately, the prognosis depends on which organs are affected and how frequently the disease is reactivated. The most common cause of death is renal failure; however, chronic immunosuppression also predisposes these patients to increased mortality because of infection and development of malignancy. For reasons that are poorly understood, the prognosis is worse for men than for women. In addition, blacks tend to fare more poorly than whites.

The prognosis for patients with CCLE is considerably better than that for patients with SLE, although transformation to SLE may be seen in approximately 5% of CCLE patients. Usually, CCLE remains confined to the skin, but it may persist and be quite a nuisance. For about 50% of CCLE patients, the problem eventually resolves after several years.

SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS (PROGRESSIVE SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS; SCLERODERMA; HIDE-BOUND DISEASE)

Systemic sclerosis is a relatively rare condition that probably has an immunologically mediated pathogenesis. For reasons that are not understood, dense collagen is deposited in the tissues of the body in extraordin-ary amounts. Although its most dramatic effects are seen in association with the skin, the disease is often quite serious, with most organs of the body affected.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Systemic sclerosis affects approximately 19 persons per million population each year. Women have the condition three to five times more frequently than do men. Most patients are adults. The onset of the disease is generally insidious, with the cutaneous changes often responsible for bringing the problem to the patient’s attention.

Often one of the first signs of the disease is Ray-naud’s phenomenon, a vasoconstrictive event triggered by emotional distress or exposure to cold. Raynaud’s phenomenon (see CREST syndrome, on page 801) is not specific for systemic sclerosis, however, because it may be present in other immunologically mediated diseases and in otherwise healthy people. Resorption of the terminal phalanges (acro-osteolysis) and flexion contractures produce shortened, clawlike fingers (Fig. 16-121). The vascular events and the abnormal collagen deposition contribute to the production of ulcerations on the fingertips (Fig. 16-122).

Fig. 16-121 Systemic sclerosis. The tense, shiny appearance of the skin is evident. Note that the fingers are fixed in a clawlike position, with some showing shortening as a result of acro-osteolysis.

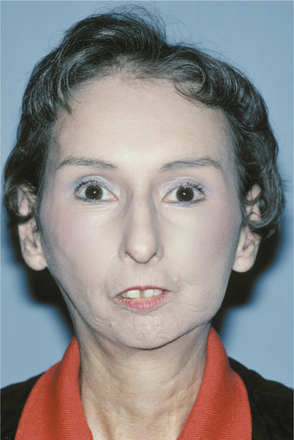

The skin develops a diffuse, hard texture (sclero = hard; derma = skin), and its surface is usually smooth. Involvement of the facial skin by subcutaneous collagen deposition results in the characteristic smooth, taut, masklike facies (Fig. 16-123). Similarly, the nasal alae become atrophied, resulting in a pinched appearance to the nose, called a mouse facies.

Fig. 16-123 Systemic sclerosis. The involvement of the facial skin with abnormal collagen deposition produces a masklike facies. Note the loss of the alae of the nose.

Involvement of other organs may be subtle at first, but the results are more serious. Fibrosis of the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract leads to organ failure, typically within the first 3 years after the diagnosis is made. Pulmonary fibrosis is particularly sign-ificant, leading to pulmonary hypertension and heart failure, a primary cause of death for these patients.

The oral manifestations occur in varying degrees. Microstomia often develops as a result of collagen deposition in the perioral tissues. This causes a limitation of opening the mouth in nearly 70% of these patients (Fig. 16-124). Characteristic furrows radiating from the mouth produce a “purse string” appearance. Loss of attached gingival mucosa and multiple areas of gingival recession may occur in some patients. Dysphagia often develops as a result of deposition of collagen in the lingual and esophageal submucosa, producing a firm, hypomobile (boardlike) tongue and an inelastic esophagus, thus hindering swallowing. Xerostomia is frequently identified in these patients, and the possibility of concurrent secondary Sjögren syndrome may require consideration.

Fig. 16-124 Systemic sclerosis. Same patient as depicted in Fig. 16-123. Because of the associated microstomia, this is the patient’s maximal opening.

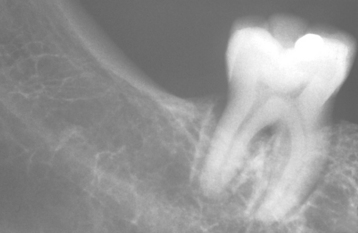

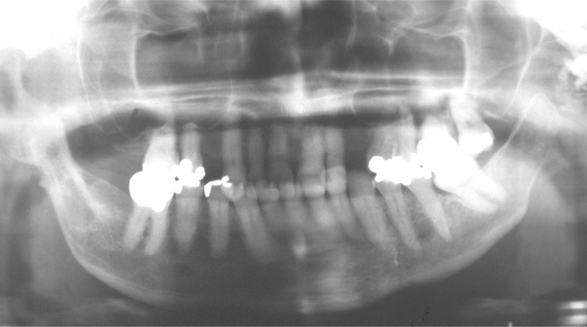

On dental radiographs, diffuse widening of the periodontal ligament space is often present throughout the dentition. The extent of the widening may vary, with some examples being subtle and others quite dramatic (Fig. 16-125). Varying degrees of resorption of the posterior ramus of the mandible, the coronoid process, the chin, and the condyle may be detected on panoramic radiographs, affecting approximately 10% to 20% of patients (Fig. 16-126). In theory, these areas are resorbed because of the increased pressure associated with the abnormal collagen production. Individual tooth resorption has also been reported to occur at a higher frequency in these patients.

Fig. 16-125 Systemic sclerosis. Diffuse widening of the periodontal ligament space is often identified on evaluation of periapical radiographs.

Fig. 16-126 Systemic sclerosis. Panoramic radiographic evaluation may show a characteristic resorption of the ramus, coronoid process, or condyle.

A mild variant of this condition, called localized scleroderma, usually affects only a solitary patch of skin. Because these lesions often look like scars, the name en coup de sabre (“strike of the sword”) is used to describe them (Fig. 16-127). This problem is primarily cosmetic and, unlike systemic sclerosis, it is rarely life threatening.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of tissue involved by syste-mic sclerosis shows diffuse deposition of dense collagen within and around the normal structures (Fig. 16-128). This abnormal collagen replaces and destroys the normal tissue, causing the loss of normal tissue function.

DIAGNOSIS: During the early phases, it may be difficult to make a diagnosis of systemic sclerosis. Generally, the clinical signs of stiffened skin texture along with the development of Raynaud’s phenomenon are suggestive of the diagnosis. A skin biopsy may be supportive of the diagnoses if abundant collagen deposition is observed microscopically.

Laboratory studies may be helpful to the diagno-stic process if anticentromere antibodies or anti-Scl 70 (topoisomerase I) is detected. Antitopoisomerase I antibodies are seen more often with systemic sclerosis; anticentromere antibodies are usually associated with more limited forms of scleroderma or CREST syndrome (see next topic). In addition, increasing levels of endothelial cell autoantibodies appear to correlate with disease severity.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The management of systemic sclerosis is difficult. Unfortunately, many of the recommended treatments have not been examined in controlled trials, and the natural waxing and waning course of the disease makes it difficult to assess the effectiveness of a given treatment in an open-label trial. Systemic medications, such as penicillamine, are prescribed in an attempt to inhibit collagen production. A recent double-blind study, however, showed no difference in measured patient outcomes with high-dose versus low-dose penicillamine, suggesting that perhaps this medication has limited efficacy. Surprisingly, corticosteroids are of little benefit. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy has shown some beneficial effect on the skin lesions; however, no improvement of the pulmonary function tests is observed.

Other management strategies are directed at controlling symptoms. Such techniques as esophageal dilation are used, for example, to temporarily correct the esophageal dysfunction and dysphagia. Calcium channel blocking agents help to increase peripheral blood flow and lessen the symptoms of Raynaud’s phenomenon, but many patients can reduce episodes by keeping warm (especially their hands and feet) or by stopping cigarette smoking. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors often effectively control hypertension if kidney involvement is prominent.

From a dental standpoint, problems may develop for patients who wear prostheses because of the microstomia and inelasticity of the mouth. Collapsible dental appliances with special hinges have been made to facilitate the insertion and removal of dentures. Microstomia and inelastic soft tissue also hamper the maintenance of good oral hygiene, and affected patients have a decreased ability to manipulate a toothbrush as a result of sclerotic changes in the fingers and hands. Surgical correction of open bite associated with condylar resorption has been described. Infrequently, the resorption of the mandible may become so great as to cause a pathologic fracture.

The prognosis is poor, although the outlook is better for patients with limited cutaneous involvement than for those with diffuse involvement. If the heart is affected, then the prognosis is particularly poor, but most patients die because of pulmonary involvement. Overall survival figures are difficult to calculate be-cause of a variety of factors, including the rarity of the disease, the inherent variability of its natural course, and the variation in treatments provided at medical centers around the world. With current treatment regimens, it is estimated that 10-year survival rates for patients with limited cutaneous scleroderma approach 80% to 90%, whereas survival drops to 60% to 75% for patients with diffuse systemic sclerosis.

CREST SYNDROME (ACROSCLEROSIS; LIMITED SCLERODERMA)

CREST syndrome is an uncommon condition that may be a relatively mild variant of systemic sclerosis. The term CREST is an acronym for Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysfunction, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasia.

CLINICAL FEATURES: As with systemic sclerosis, most patients with CREST syndrome are women in the sixth or seventh decade of life. The characteristic signs may not appear synchronously but instead may develop sequentially over a period of months to years.

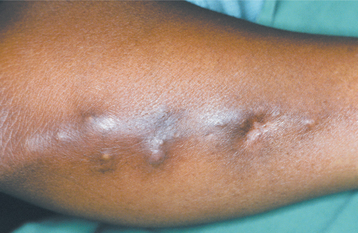

Calcinosis cutis occurs in the form of movable, nontender, subcutaneous nodules, 0.5 to 2.0 cm in size, which are usually multiple (Fig. 16-129). Larger, more numerous or superficial calcifications may occasionally become bothersome and require removal.

Fig. 16-129 CREST syndrome. The subcutaneous nodules on this patient’s arm represent deposition of calcium salts (calcinosis cutis). (Courtesy of Dr. Román Carlos.)

Raynaud’s phenomenon may be observed when a person’s hands or feet are exposed to cold temperatures. The initial clinical sign is a dramatic blanching of the digits, which appear dead-white in color as a result of severe vasospasm. A few minutes later, the affected extremity takes on a bluish color because of venous stasis. After warming, increased blood flow results in a dusky-red hue with the return of hyperemic blood flow. This may be accompanied by varying degrees of throbbing pain.

Esophageal dysfunction, caused by abnormal collagen deposition in the esophageal submucosa, may not be noticeable in the early phases of CREST syndrome. Often the subtle initial signs of this problem must be demonstrated by barium swallow radiologic studies.

The sclerodactyly of CREST syndrome is rather remarkable. The fingers become stiff, and the skin takes on a smooth, shiny appearance. Often the fingers undergo permanent flexure, resulting in a characteristic “claw” deformity (Fig. 16-130). As with systemic sclerosis, this change is due to abnormal deposition of collagen within the dermis in these areas.

The telangiectasias in this syndrome are similar to those seen in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) (see page 754). As with that condition, significant bleeding from the superficial dilated capillaries may occur. The facial skin and the vermilion zone of the lips are commonly affected (Fig. 16-131).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic findings in CREST syndrome are similar, although milder, to those seen in systemic sclerosis. Superficial dilated capillaries are observed if a telangiectatic vessel is included in the biopsy specimen.

DIAGNOSIS: Sometimes, HHT may be considered in the differential diagnosis if the history is unclear and the other signs of CREST syndrome are not yet evident. In these cases, laboratory studies directed at identifying anticentromere antibodies may be useful, because this test is relatively specific for CREST syndrome.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of patients with CREST syndrome is essentially the same as that of those with systemic sclerosis. Because CREST syndrome usually is not as severe, the treatment does not have to be as aggressive. Although the prognosis for this condition is much better than that for systemic sclerosis, patients should be monitored for an increased risk of developing pulmonary hypertension or primary biliary cirrhosis, generally more than 10 years after the initial diagnosis.

ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS

Acanthosis nigricans is an acquired dermatologic problem characterized by the development of a velvety, brownish alteration of the skin. In some instances, this unusual condition develops in conjunction with gastrointestinal cancer and is termed malignant acanthosis nigricans. The cutaneous lesion itself is benign, yet it is significant because it represents a cutaneous marker for internal malignancy. The cause of malignant acanthosis nigricans is unknown, although a cytokine-like peptide capable of affecting the epidermal cells may be produced by the malignancy.

Most cases, estimated to affect as many as 5% of adults, are not associated with a malignancy and are termed benign acanthosis nigricans. A clinically similar form, pseudoacanthosis nigricans, may occur in some obese people. Some benign forms of acanthosis nigricans may be inherited or may occur in association with various endocrinopathies, such as diabetes mellitus, Addison’s disease, hypothyroidism, and acromegaly. Furthermore, benign acanthosis nigricans may occur with certain syndromes (e.g., Crouzon syndrome) or drug ingestion (e.g., oral contraceptives, corticosteroids). These forms of the condition are typically associated with resistance of the tissues to the effects of insulin, similar to the insulin resistance seen in non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM). Even though the affected individuals may not have overt diabetes mellitus, they often show increased levels of insulin or an abnormal response to exogenously administered insulin.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The malignant form of acanthosis nigricans develops in association with an internal malignancy, particularly adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Approximately 20% of the cases of malignant acanthosis nigricans are identified before the malignancy is found, but most appear at about the same time as discovery of the gastrointestinal tumor or thereafter.

Both forms of acanthosis nigricans affect the flexural areas of the skin predominantly, appearing as finely papillary, hyperkeratotic, brownish patches that are usually asymptomatic (Fig. 16-132). The texture of the lesions has been variably described as either velvety or leathery.

Fig. 16-132 Acanthosis nigricans. The lesions are characterized by numerous fine, almost velvety, confluent papules. The lesions most often affect the flexural areas, such as the axilla depicted in this photograph. (From Hall JM, Moreland A, Cox GJ et al: Oral acanthosis nigricans: report of a case and comparison of oral and cutaneous pathology, Am J Dermatopathol 10:68-73, 1988.)

Oral lesions of acanthosis nigricans have also been reported and may occur in 25% to 50% of affected patients, especially those with the malignant form. These lesions appear as diffuse, finely papillary areas of mucosal alteration that most often involve the tongue or lips, particularly the upper lip (Figs. 16-133 and 16-134). The buccal mucosa may also be affected. The brownish pigmentation associated with the cutaneous lesions is usually not seen in oral acanthosis nigricans.

Fig. 16-133 Acanthosis nigricans. The vermilion zone of the lips is affected. (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

Fig. 16-134 Acanthosis nigricans. Same patient as depicted in Fig. 16-133. Note involvement of the palatal mucosa. (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic features of the various forms of acanthosis nigricans are essentially identical. The epidermis exhibits hyperorthokeratosis and papillomatosis. Usually, some degree of increased melanin depo sition is noted, but the extent of acanthosis (thickening of the spinous layer) is really rather mild. The oral lesions have much more acanthosis, but show minimal increased melanin pigmentation (Fig. 16-135).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Although acanthosis nigricans itself is a harmless process, the patient should be evaluated to ascertain which form of the disease is present. Identification and treatment of the underlying malignancy obviously are important for patients with the malignant type; unfortunately, the prognosis for these individuals is very poor. Interestingly, malignant acanthosis nigricans may resolve when the cancer is treated. Keratolytic agents may improve the appearance of the benign forms.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aswegan, AL, Josephson, KD, Mowbray, R, et al. Autosomal dominant hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia in a large family. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:462–467.

Berg, D, Weingold, DH, Abson, KG, et al. Sweating in ectodermal dysplasia syndromes. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1075–1079.

Bonilla, ED, Guerra, L, Luna, O. Overdenture prosthesis for oral rehabilitation of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: a case report. Quintessence Int. 1997;28:657–665.

Cambiaghi, S, Restano, L, Paakkonen, K, et al. Clinical findings in mosaic carriers of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:217–224.

Ho, L, Williams, MS, Spritz, RA. A gene for autosomal dominant hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (EDA3) maps to chromosome 2q11-q13. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1102–1106.

Itin, PH, Fistarol, SK. Ectodermal dysplasias. Am J Med Genet. 2004;131C:45–51.

Jorgenson, RJ, Salinas, CF, Dowben, JS, et al. A population study on the density of palmar sweat pores. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1988;24:51–63.

Kantaputra, PN, Hamada, T, Kumchai, T, et al. Heterozygous mutation in the SAM domain of p63 underlies Rapp-Hodgkin ectodermal dysplasia. J Dent Res. 2003;82:433–437.

Kearns, G, Sharma, A, Perrott, D, et al. Placement of endosseous implants in children and adolescents with hereditary ectodermal dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:5–10.

Lamartine, J. Towards a new classification of ectodermal dysplasias. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:351–355.

Levin, LS. Dental and oral abnormalities in selected ectodermal dysplasia syndromes. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1988;24:205–227.

Lo Muzio, L, Bucci, P, Carile, F, et al. Prosthetic rehabilitation of a child affected from anhydrotic ectodermal dysplasia: a case report. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:1–7.

Mills, R, Montague, M-L, Naysmith, L. Ear, nose and throat manifestations of ectodermal dysplasia. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:406–408.

Munoz, F, Lestringant, G, Sybert, V, et al. Definitive evidence for an autosomal recessive form of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia clinically indistinguishable from the more common X-linked disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:94–100.

Nordgarden, H, Johannessen, S, Storhaug, K, et al. Salivary gland involvement in hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Oral Dis. 1998;4:152–154.

Shankly, PE, Mackie, IC, McCord, FJ. The use of tricalcium phosphate to preserve alveolar bone in a patient with ectodermal dysplasia: a case report. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19:35–39.

Singh, P, Warnakulasuriya, S. Aplasia of submandibular salivary glands associated with ectodermal dysplasia. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:634–636.

Jorgenson, RJ, Levin, LS. White sponge nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:73–76.

Krajewska, IA, Moore, L, Brown, JH. White sponge nevus presenting in the esophagus—case report and literature review. Pathology. 1992;24:112–115.

Marcushamer, M, King, DL, McGuff, S. White sponge nevus: case report. Pediatr Dent. 1995;17:458–459.

Martelli, H, Mourão-Pereira, S, Martins-Rocha, T, et al. White sponge nevus: report of a three-generation family. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:43–47.

Morris, R, Gansler, TS, Rudisill, MT, et al. White sponge nevus: diagnosis by light microscopic and ultrastructural cytology. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:357–361.

Richard, G, De Laurenzi, V, Didona, B, et al. Keratin 13 point mutation underlies the hereditary mucosal disorder white sponge nevus. Nat Genet. 1995;11:453–455.

Rugg, EL, Magee, GJ, Wilson, NJ, et al. Identification of two novel mutations in keratin 13 as the cause of white sponge naevus. Oral Dis. 1999;5:321–324.

Rugg, EL, McLean, WHI, Allison, WE, et al. A mutation in the mucosal keratin K4 is associated with oral white sponge nevus. Nat Genet. 1995;11:450–452.

Terrinoni, A, Candi, E, Oddi, S, et al. A glutamine insertion in the 1A alpha helical domain of the keratin 4 gene in a familial case of white sponge nevus. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:388–391.

Terrinoni, A, Rugg, EL, Lane, EB, et al. A novel mutation in the keratin 13 gene causing oral white sponge nevus. J Dent Res. 2001;80:919–923.

Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis

McLean, IW, Riddle, PJ, Scruggs, JH, et al. Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis. A report of two cases from Texas. J Ophthalmol. 1981;88:164–168.

Reed, JW, Cashwell, LF, Klintworth, GK. Corneal manifestations of hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97:297–300.

Sadeghi, EM, Witkop, CJ. The presence of Candida albicans in hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis: an ultrastructural observation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;48:342–346.

Shields, CL, Shields, JA, Eagle, RC. Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:422–423.

Feinstein, A, Friedman, J, Schewach-Millet, M. Pachyonychia congenita. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:705–711.

García-Rio, I, Peñas, PF, García-Díez, A, et al. A severe case of pachyonychia congenital type I due to a novel praline mutation in keratin 6a. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:800–802.

Leachman, SA, Kaspar, RL, Fleckman, P, et al. Clinical and pathological features of pachyonychia congenita. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:3–17.

McLean, WHI, Rugg, EL, Lunny, DP, et al. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nat Genet. 1995;9:273–278.

Milstone, LM, Fleckman, P, Leachman, SA, et al. Treatment of pachyonychia congenita. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:18–20.

Pradeep, AR, Nagaraja, C. Pachyonychia congenita with unusual dental findings: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:89–93.

Smith, FJD, Liao, H, Cassidy, AJ, et al. The genetic basis of pachyonychia congenita. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:21–30.

Smith, FJD, McKusick, VA, Nielsen, K, et al. Cloning of multiple keratin 16 genes facilitates prenatal diagnosis of pachyonychia congenita type 1. Prenat Diag. 1999;19:941–946.

Stieglitz, JB, Centerwall, WR. Pachyonychia congenita (Jadassohn-Lewandowsky syndrome): a seventeen member, four-generation pedigree with unusual respiratory and dental involvement. Am J Med Genet. 1983;14:21–28.

Baykal, C, Kavak, A, Gülcan, P, et al. Dyskeratosis congenita associated with three malignancies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:216–218.

Davidovitch, E, Eimerl, D, Aker, M, et al. Dyskeratosis congenita: dental management of a medically complex child. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27:244–248.

Dokal, I, Vulliamy, T. Dyskeratosis congenita: its link to telomerase and aplastic anemia. Blood Rev. 2003;17:217–225.

Elliot, AM, Graham, GE, Bernstein, M, et al. Dyskeratosis congenita: an autosomal recessive variant. Am J Med Genet. 1999;83:178–182.

Fernandes-Gomes, M, Pinheiro de Abreu, P, de Freitas-Banzi, ÉC, et al. Interdisciplinary approach to treat dyskeratosis congenita associated with severe aplastic anemia: a case report. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:81–85.

Ghavamzadeh, A, Alimoghadam, K, Nasseri, P, et al. Correction of bone marrow failure in dyskeratosis congenita by bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:299–301.

Handley, TPB, McCaul, JA, Ogden, GR. Dyskeratosis congenita. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:331–336.

Handley, TPB, Ogden, GR. Dyskeratosis congenita: oral hyperkeratosis in association with lichenoid reaction. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:508–512.

Hyodo, M, Sadamoto, A, Hinohira, Y, et al. Tongue cancer as a complication of dyskeratosis congenita in a woman. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20:405–407.

Kanegane, H, Kasahara, Y, Okamura, J, et al. Identification of DKC1 gene mutations in Japanese patients with X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:432–434.

Knight, SW, Heiss, NS, Vulliamy, TJ, et al. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is predominantly caused by missense mutations in the DKC1 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:50–58.

Marrone, A, Mason, PJ. Human genome and diseases: review. Dyskeratosis congenita. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:507–517.

Mason, PJ, Wilson, DB, Bessler, M. Dyskeratosis congenita—a disease of dysfunctional telomere maintenance. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5:159–170.

Mitchell, JR, Wood, E, Collins, K. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 1999;402:551–555.

Tanaka, A, Kumagai, S, Nakagawa, K, et al. Cole-Engman syndrome associated with leukoplakia of the tongue: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:1138–1141.

Vulliamy, TJ, Marrone, A, Knight, SW, et al. Mutations in dyskeratosis congenita: their impact on telomere length and the diversity of clinical presentation. Blood. 2006;107:2680–2685.

Vulliamy, T, Dokal, I. Dyskeratosis congenita. Semin Hematol. 2006;43:157–166.

Benhamou, S, Sarasin, A. Variability in nucleotide excision repair and cancer risk: a review. Mutat Res. 2000;462:149–158.

Cleaver, JE. Common pathways for ultraviolet skin carcinogenesis in the repair and replication defective groups of xeroderma pigmentosum. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;23:1–11.

Cleaver, JE. Cancer in xeroderma pigmentosum and related disorders of DNA repair. Nature Rev. 2005;5:564–573.

Goyal, JL, Rao, VA, Srinivasan, R, et al. Oculocutaneous manifestations in xeroderma pigmentosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:295–297.

Kraemer, KH, Lee, MM, Scotto, J. Xeroderma pigmentosum: cutaneous, ocular, and neurologic abnormalities in 830 published cases. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:241–250.

Magnaldo, T, Sarasin, A. Xeroderma pigmentosum: from symptoms and genetics to gene-based skin therapy. Cells Tissues Organs. 2004;177:189–198.

Park, S, Dock, M. Xeroderma pigmentosum: a case report. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25:397–400.

Patton, LL, Valdez, IH. Xeroderma pigmentosum: review and report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:297–300.

van Steeg, H, Kraemer, KH. Xeroderma pigmentosum and the role of UV-induced DNA damage in skin cancer. Mol Med Today. 1999;5:86–94.

Hereditary Mucoepithelial Dysplasia

Boralevi, F, Haftek, M, Vabres, P, et al. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia: clinical, ultrastructural and genetic study of eight patients and literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:310–318.

Rogers, M, Kourt, G, Cameron, A. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:133–138.

Scheman, AJ, Ray, DJ, Witkop, CJ, et al. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia: case report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:351–357.

Urban, MD, Schosser, R, Spohn, W, et al. New clinical aspects of hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1991;39:338–341.

Witkop, CJ, White, JG, Sauk, JJ, et al. Clinical, histologic, cytologic and ultrastructural characteristics of the oral lesions from hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;46:645–657.

Bentolila, R, Rivera, H, Sanchez-Quevedo, MC. Incontinentia pigmenti: a case report. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:54–57.

Berlin, AL, Paller, AS, Chan, LS. Incontinentia pigmenti: a review and update on the molecular basis of pathophysiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:169–187.

Bruckner, AL. Incontinentia pigmenti: a window to the role of NF-kB function. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2004;23:116–124.

Emery, MM, Siegfried, EC, Stone, MS, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: transmission from father to daughter. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:368–372.

Faloyin, M, Levitt, J, Bercowitz, E, et al. All that is vesicular is not herpes: incontinentia pigmenti masquerading as herpes simplex virus in a newborn. Pediatrics. 2004;114:270–272.

Fusco, F, Fimiani, G, Tadini, G, et al. Clinical diagnosis of incontinentia pigmenti in a cohort of male patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:264–267.

Landy, SJ, Donnai, D. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome). J Med Genet. 1993;30:53–59.

Pacheco, TR, Levy, M, Collyer, JC, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti in male patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:251–255.

Phan, TA, Wargon, O, Turner, AM. Incontinentia pigmenti case series: clinical spectrum of incontinentia pigmenti in 53 female patients and their relatives. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:474–480.

Welbury, TA, Welbury, RR. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome): report of a case. ASDC J Dent Child. 1999;66:213–215.

Adams, AM, Macleod, RI, Munro, CS. Symptomatic and asymptomatic salivary duct abnormalities in Darier’s disease: a sialographic study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1994;23:25–28.

Burge, SM, Wilkinson, JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40–50.

Cooper, SM, Burge, SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97–105.

Dhitavat, J, Dode, L, Leslie, N, et al. Mutations in the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase isoform cause Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:486–489.

Foggia, L, Hovnanian, A. Calcium pump disorders of the skin. Am J Med Genet. 2004;131C:20–31.

Frezzini, C, Cedro, M, Leao, JC, et al. Darier disease affecting the gingival and oral mucosal surfaces. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:e29–e33.

Jalil, AA, Zain, RB, van der Waal, I. Darier disease: a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:336–338.

Macleod, RI, Munro, CS. The incidence and distribution of oral lesions in patients with Darier’s disease. Br Dent J. 1991;171:133–136.

Munro, CS. The phenotype of Darier’s disease: penetrance and expressivity in adults and children. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:126–130.

Sakuntabhai, A, Ruiz-Perez, V, Carter, S, et al. Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca2+ pump, cause Darier’s disease. Nat Genet. 1999;21:271–277.

Sehgal, VN, Srivastava, G. Darier’s (Darier-White) disease/keratosis follicularis. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:184–192.

Zeglaoui, F, Zaraa, I, Fazaa, B, et al. Dyskeratosis follicularis disease: case reports and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:114–117.

Chau, MNY, Radden, BG. Oral warty dyskeratoma. J Oral Pathol. 1984;13:546–556.

Kaddu, S, Dong, H, Mayer, G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423–428.

Kaugars, GE, Lieb, RJ, Abbey, LM. Focal oral warty dyskeratoma. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:123–130.

Laskaris, G, Sklavounou, A. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23:371–375.

Mesa, ML, Lambert, WC, Schneider, LC, et al. Oral warty dyskeratoma. Cutis. 1984;33:293–296.

Giardiello, FM, Trimbath, JD. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:408–415.

Hearle, N, Schumacher, V, Menko, FH, et al. Frequency and spectrum of cancers in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3209–3215.

Hemminki, A. The molecular basis and clinical aspects of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:735–750.

Jenne, DE, Reimann, H, Nezu, J-I, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nat Genet. 1998;18:38–43.

Le Meur, N, Martin, C, Saugier-Veber, P, et al. Complete germline deletion of the STK11 gene in a family with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Eur J Human Genet. 2004;12:415–418.

McGarrity, TJ, Amos, C. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: clinicopathology and molecular alterations. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2135–2144.

McGarrity, TJ, Kulin, HE, Zaino, RJ. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:596–604.

Uno, A, Hori, Y. Disturbance of melanosome transfer in pigmented macules of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. In: Fitzpatrick TB, et al, eds. Brown melanoderma. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; 1986:173–178.

Westerman, AM, Entius, MM, de Baar, E, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: 78-year follow-up of the original family. Lancet. 1999;353:1211–1215.

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

Abdalla, SA, Letarte, M. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: current views on genetics and mechanisms of disease. J Med Genet. 2006;43:97–110.

Abdalla, SA, Pece-Barbara, N, Vera, S, et al. Analysis of ALK-1 and endoglin in newborns from families with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1227–1237.

Bayrak-Toydemir, P, McDonald, J, Markewitz, B, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: mutations and manifestations. Am J Med Genet. 2006;140A:463–470.

Begbie, ME, Wallace, GMF, Shovlin, CL. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome): a view from the 21st century. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:18–24.

Bergler, W, Götte, K. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias: a challenge for the clinician. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;256:10–15.

Braveman, IM, Keh, A, Jacobson, BS. Ultrastructure and three-dimensional organization of the telangiectases of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;95:422–427.

Cymerman, U, Vera, S, Pece-Barbara, N, et al. Identification of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1 in newborns by protein expression and mutation analysis of endoglin. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:24–35.

Fiorella, ML, Ross, D, Henderson, KJ, et al. Outcome of septal dermoplasty in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:301–305.

Guttmacher, AE, Marchuk, DA, White, RI. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:918–924.

Hitchings, AE, Lennox, PA, Lund, VJ, et al. The effect of treatment for epistaxis secondary to hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Am J Rhinol. 2005;19:75–78.

Kjeldsen, AD, Vase, P, Green, A. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: a population-based study of prevalence and mortality in Danish patients. J Intern Med. 1999;245:31–39.

McAllister, KA, Grogg, KM, Johnson, DW, et al. Endoglin, a TGF-b binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat Genet. 1994;8:345–351.

Russi, EW, Dazzi, H, Gäumann, N. Septic pulmonary embolism due to periodontal disease in a patient with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Respiration. 1996;63:117–119.

Swanson, DL, Dahl, MV. Embolic abscesses in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:580–583.

Abel, MD, Carrasco, LR. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: classifications, oral manifestations, and dental considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:582–590.

Beighton, P, De Paepe, A, Steinmann, B, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Am J Med Genet. 1998;77:31–37.

Burrows, NP. The molecular genetics of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:99–106.

De Coster, PJ, Malfait, F, Martens, LC, et al. Unusual oral findings in dermatosparaxis (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VIIC). J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:568–570.

De Coster, PJ, Martens, LC, De Paepe, A. Oral health in prevalent types of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:298–307.

Dyne, KM, Vitellaro-Zuccarello, L, Bacchella, L, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VIII: biochemical, stereological and immunocytochemical studies on dermis from a child with clinical signs of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and a family history of premature loss of permanent teeth. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:458–463.

Fridrich, KL, Fridrich, HH, Kempf, KK, et al. Dental implications in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:431–435.

Hartsfield, JK, Kousseff, BG. Phenotypic overlap of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome types IV and VIII. Am J Med Genet. 1990;37:465–470.

Malfait, F, De Coster, P, Hausser, I, et al. The natural history, including orofacial features of three patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, dermatosparaxis type (EDS type VIIC). Am J Med Genet. 2004;131A:18–28.

Norton, LA, Assael, LA. Orthodontic and temporomandibular joint considerations in treatment of patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1997;111:75–84.

Nuytinck, L, Freund, M, Lagae, L, et al. Classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome caused by a mutation in type I collagen. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1398–1402.

Pepin, M, Schwarze, U, Superti-Furga, A, et al. Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:673–680.

Pope, FM, Komorowska, A, Lee, KW, et al. Ehlers Danlos syndrome type I with novel dental features. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:418–421.

Rahman, N, Dunstan, M, Teare, MD, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome with severe early-onset periodontal disease (EDS-VIII) is a distinct, heterogeneous disorder with one predisposition gene at chromosome 12p13. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:198–204.

Sacks, H, Zelig, D, Schabes, G. Recurrent temporomandibular joint subluxation and facial ecchymosis leading to diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: report of surgical management and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:641–647.

Yassin, OM, Rihani, FB. Multiple developmental dental anomalies and hypermobility type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2006;30:337–341.

Barron, RP, Kainulainen, VT, Forrest, CR, et al. Tuberous sclerosis: clinicopathologic features and review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002;30:361–366.

Çelenk, P, Alkan, A, Canger, EM, et al. Fibrolipomatous hamartoma in a patient with tuberous sclerosis: report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:202–206.

Crino, PB, Nathanson, KL, Henske, EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1345–1356.

Damm, DD, Tomich, CE, White, DK, et al. Intraosseous fibrous lesions of the jaws. A manifestation of tuberous sclerosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:334–340.

Franz, DN. Diagnosis and management of tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1998;5:253–268.

Franz, DN. Non-neurologic manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:690–698.

Houser, OW, Shepherd, CW, Gomez, MR. Imaging of intracranial tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:81–93.

Hurst, JS, Wilcoski, S. Recognizing an index case of tuberous sclerosis. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:703–708. [710].

Hyman, MH, Whittemore, VH. National Institutes of Health consensus conference: tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:662–665.

Jones, AC, Shyamsundar, MM, Thomas, MW, et al. Comprehensive mutation analysis of TSC1 and TSC2—and phenotypic correlations in 150 families with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1305–1315.

Lendvay, TS, Marshall, FF. The tuberous sclerosis complex and its highly variable manifestations. J Urol. 2003;169:1635–1642.

Lygidakis, NA, Lindenhum, RH. Oral fibromatosis in tuberous sclerosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:725–728.

O’Callaghan, FJ, Osborne, JP. Advances in the understanding of tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83:140–142.

Roach, ES, Sparagana, SP. Diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis com-plex. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:643–649.

Rosser, T, Panigrahy, A, McClintock, W. The diverse clinical manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex: a review. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:27–36.

Sampson, JR, Attwood, D, Al Mughery, AS, et al. Pitted enamel hypoplasia in tuberous sclerosis. Clin Genet. 1992;42:50–52.

Shepherd, CW, Gomez, MR. Mortality in the Mayo Clinic tuberous sclerosis complex study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:375–377.

Thomas, D, Rapley, J, Strathman, R, et al. Tuberous sclerosis with gingival overgrowth. J Periodontol. 1992;63:713–717.

Albrecht, S, Haber, RM, Goodman, JC, et al. Cowden syndrome and Lhermitte-Duclos disease. Cancer. 1992;70:869–876.

Bagan, JV, Penarrocha, M, Vera-Sempere, F. Cowden syndrome: clinical and pathological considerations in two new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:291–294.

Bonneau, D, Longy, M. Mutations of the human PTEN gene. Hum Mutat. 2000;16:109–122.

Devlin, MF, Barrie, R, Ward-Booth, RP. Cowden’s disease: a rare but important manifestation of oral papillomatosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;30:335–336.

Eng, C. Genetics of Cowden syndrome: through the looking glass of oncology (Review). Int J Oncol. 1998;12:701–710.

Hand, JL, Rogers, RS. Oral manifestations of genodermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:183–194.

Leão, JC, Batista, V, Guimarães, PB, et al. Cowden’s syndrome affecting the mouth, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:569–572.

Mallory, SB. Cowden syndrome (multiple hamartoma syndrome). Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:27–31.

Merks, JHM, de Vries, LS, Zhou, X-P, et al. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: variability of an entity. J Med Genet. 2003;40:e111.

Mignogna, MD, Lo Muzio, L, Ruocco, V, et al. Early diagnosis of multiple hamartoma and neoplasia syndrome (Cowden disease). The role of the dentist. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:295–299.

Nelen, MR, Padberg, GW, Peeters, EAJ, et al. Localization of the gene for Cowden disease to chromosome 10q22-23. Nat Genet. 1996;13:114–116.

Pilarski, R, Eng, C. Will the real Cowden syndrome please stand up (again)? Expanding mutational and clinical spectra of the PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome. J Med Genet. 2004;41:323–326.

Porter, S, Cawson, R, Scully, C, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome presenting with oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82:295–301.

Schaffer, JV, Kamino, H, Witkiewicz, A, et al. Mucocutaneous neuromas: an underrecognized manifestation of PTEN hamartoma-tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:625–632.

Scheper, MA, Nikitakis, NG, Sarlani, E, et al. Cowden syndrome: report of a case with immunohistochemical analysis and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:625–631.

Takenoshita, Y, Kubo, S, Takeuchi, T, et al. Oral and facial lesions in Cowden’s disease: report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:682–687.

Wright, DD, Whitney, J. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden’s syndrome): case report and literature review. Gen Dent. 2006;54:417–419.

Azrak, B, Kaevel, K, Hofmann, L, et al. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: oral findings and problems. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:111–115.

Bello, YM, Falabella, AF, Schachner, LA. Management of epidermolysis bullosa in infants and children. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:278–282.

Brain, JH, Paul, BF, Assad, DA. Periodontal plastic surgery in a dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa patient: review and case report. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1392–1396.

Bruckner-Tuderman, L. Hereditary skin diseases of anchoring fibrils. J Dermatol Sci. 1999;20:122–133.

Çagirankaya, LB, Hatipoglu, MG, Hatipoglu, H. Localized epidermolysis bullosa simplex with generalized enamel hypoplasia in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:167–168.

Das, BB, Sahoo, S. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Perinatol. 2004;24:41–47.

De Benedittis, M, Petruzzi, M, Favia, G, et al. Oro-dental manifestations in Hallopeau-Siemens type recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:128–132.

Dunnill, MGS, Eady, RAJ. The management of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:179–188.

Fine, J-D, Eady, RAJ, Bauer, EA, et al. Revised classification system for inherited epidermolysis bullosa: report of the Second International Consensus Meeting on diagnosis and classification of epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1051–1066.

Jonkman, MF. Hereditary skin diseases of hemidesmosomes. J Dermatol Sci. 1999;20:103–121.

Lin, AN. Management of patients with epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:381–387.

Marinkovich, MP. Update on inherited bullous dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 1999;17:473–485.

McAllister, JC, Marinkovich, MP. Advances in inherited epidermolysis bullosa. Adv Dermatol. 2005;21:303–334.

McGrath, JA, O’Grady, A, Mayou, BJ, et al. Mitten deformity in severe generalized recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: histological, immunofluorescence, and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:385–389.

Momeni, A, Pieper, K. Junctional epidermolysis bullosa: a case report. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15:146–150.

Mullett, F. A review of the management of the hand in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Hand Ther. 1998;11:261–265.

Pai, S, Marinkovich, MP. Epidermolysis bullosa: new and emerging trends. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:371–380.

Pekiner, FN, Yücelten, D, Özbayrak, S, et al. Oral-clinical findings and management of epidermolysis bullosa. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2005;30:59–66.

Pulkkinen, L, Uitto, J. Mutation analysis and molecular genetics of epidermolysis bullosa. Matrix Biol. 1999;18:29–42.

Serrano-Martínez, MC, Bagán, JV, Silvestre, FJ, et al. Oral lesions in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Oral Dis. 2003;9:264–268.