Dermatologic Diseases

ECTODERMAL DYSPLASIA

Ectodermal dysplasia represents a group of inherited conditions in which two or more ectodermally derived anatomic structures fail to develop. Thus depending on the type of ectodermal dysplasia, hypoplasia or aplasia of tissues (e.g., skin, hair, nails, teeth, sweat glands) may be seen. The various types of this disorder may be inherited in any one of several genetic patterns, including autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked patterns. Even though by some accounts more than 170 different subtypes of ectodermal dysplasia can be defined, these disorders are considered to be relatively rare, with an estimated frequency of seven cases occurring in every 10,000 births. For fewer than 20% of these conditions, the specific genetic mutations and their chromosomal locations have been identified. Systematically classifying these conditions can be challenging because of their wide-ranging clinical features; however, some investigators have suggested that a classification scheme based on the molecular genetic alteration associated with each type might be appropriate. Thus groups of ectodermal dysplasia syndromes could be categorized as being caused by mutations in genes encoding cell-cell signals, genes encoding adhesion molecules, or genes regulating transcription.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Perhaps the best known of the ectodermal dysplasia syndromes is hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. In most instances, this disorder seems to show an X-linked inheritance pattern, with the gene mapping to Xq12-q13.1; therefore, a male predominance is usually seen. However, a few families have been identified that show autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant patterns of inheritance.

Affected individuals typically display heat intolerance because of a reduced number of eccrine sweat glands. Sometimes the diagnosis is made during infancy because the baby appears to have a fever of undetermined origin; however, the infant simply cannot regulate body temperature appropriately because of the decreased number of sweat glands. Uncommonly, death results from the markedly elevated body temperature, although this generally happens only when the condition is not identified. Sometimes, as a diagnostic aid, a special impression can be made of the patient’s fingertips and then examined microscopically to count the density of the sweat glands. Such findings should be interpreted in conjunction with appropriate age-matched controls.

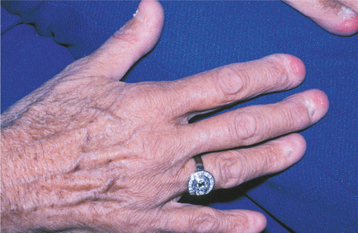

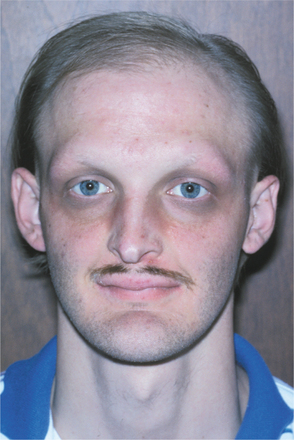

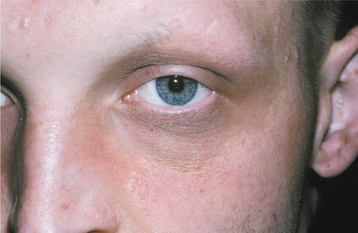

Other signs of this disorder include fine, sparse hair, including a reduced density of eyebrow and eyelash hair (Fig. 16-1). The periocular skin may show a fine wrinkling with hyperpigmentation (Fig. 16-2), and midface hypoplasia is frequently observed, often resulting in protuberant lips. Because the salivary glands are ectodermally derived, these glands may be hypoplastic or absent, and patients may exhibit varying degrees of xerostomia. The nails may also appear dystrophic and brittle.

Fig. 16-1 Ectodermal dysplasia. The sparse hair, periocular hyperpigmentation, and mild midfacial hypoplasia are characteristic features evident in this affected patient.

Fig. 16-2 Ectodermal dysplasia. Closer view of the same patient depicted in Fig. 16-1. Fine periocular wrinkling, as well as sparse eyelash and eyebrow hair, can be observed.

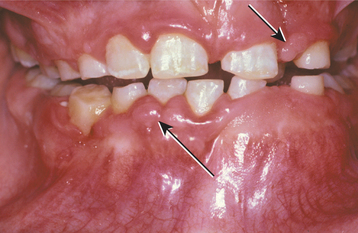

The teeth are usually markedly reduced in number (oligodontia or hypodontia), and their crown shapes are characteristically abnormal (Fig. 16-3). The incisor crowns usually appear tapered, conical, or pointed, and the molar crowns are reduced in diameter. Complete lack of tooth development (anodontia) has also been reported, but this appears to be uncommon.

Fig. 16-3 Ectodermal dysplasia. Oligodontia and conical crown forms are typical oral manifestations. (Courtesy of Dr. Charles Hook and Dr. Bob Gellin.)

Female patients may show partial expression of the abnormal gene; that is, their teeth may be reduced in number or may have mild structural changes. This incomplete presentation can be explained by the Lyon hypothesis, with half of the female patient’s X chro mosomes expressing the normal gene, and the other half expressing the defective gene.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Histopathologic examination of the skin from a patient with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia shows a decreased number of sweat glands and hair follicles. The adnexal structures that are present are hypoplastic and malformed.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Management of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia warrants genetic counseling for the parents and the patient. The dental problems are best managed by prosthetic replacement of the dentition with complete dentures, overdentures, or fixed appliances, depending on the number and location of the remaining teeth. With careful site selection, endosseous dental implants may be considered for facilitating prosthetic management of patients older than 5 years of age.

WHITE SPONGE NEVUS (CANNON’S DISEASE; FAMILIAL WHITE FOLDED DYSPLASIA)

White sponge nevus is a relatively rare genodermatosis (a genetically determined skin disorder) that is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait displaying a high degree of penetrance and variable expressivity. This condition is due to a defect in the normal keratinization of the oral mucosa. In the 30-member family of keratin filaments, the pair of keratins known as keratin 4 and keratin 13 is specifically expressed in the spinous cell layer of mucosal epithelium. Mutations in either of these keratin genes have been shown to be responsible for the clinical manifestations of white sponge nevus.

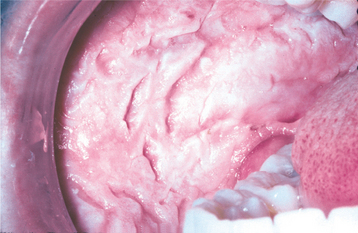

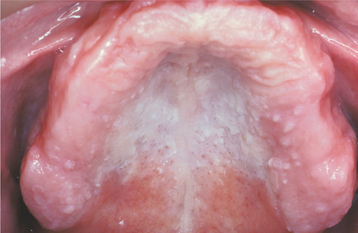

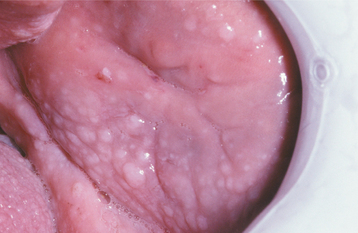

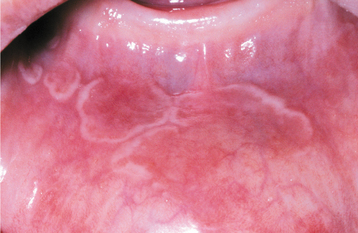

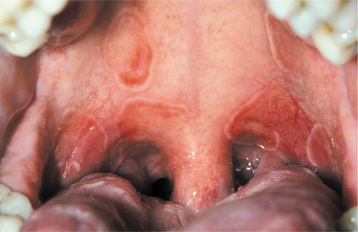

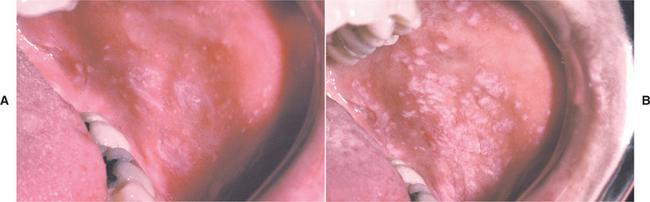

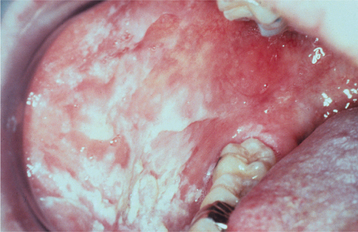

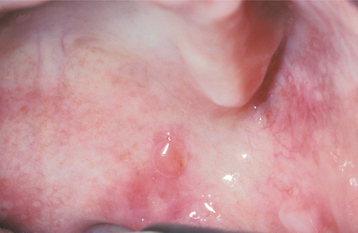

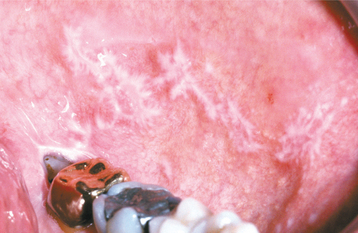

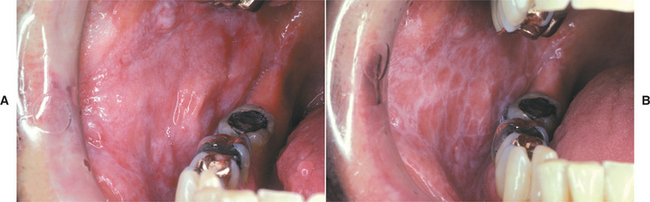

CLINICAL FEATURES: The lesions of white sponge nevus usually appear at birth or in early childhood, but sometimes the condition develops during adolescence. Symmetrical, thickened, white, corrugated or velvety, diffuse plaques affect the buccal mucosa bilaterally in most instances (Fig. 16-4). Other common intraoral sites of involvement include the ventral tongue, labial mucosa, soft palate, alveolar mucosa, and floor of the mouth, although the extent of involvement can vary from patient to patient. Extraoral mucosal sites, such as the nasal, esophageal, laryngeal, and anogenital mucosa, appear to be less commonly affected. Patients are usually asymptomatic.

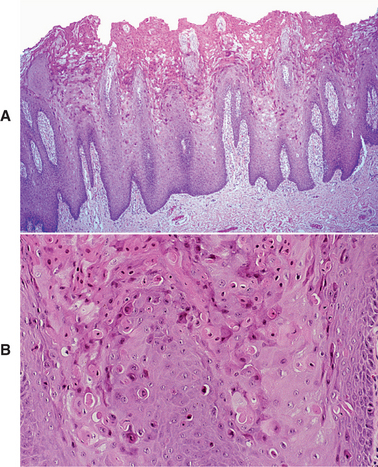

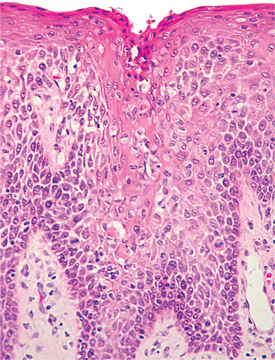

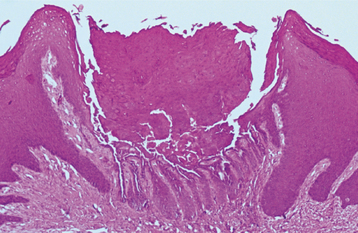

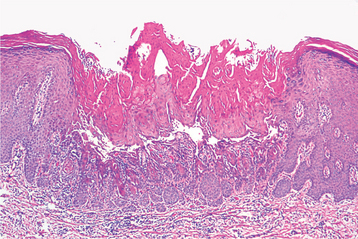

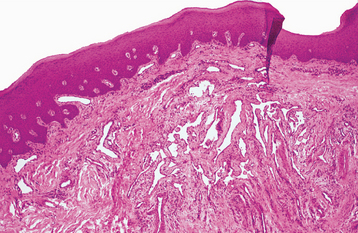

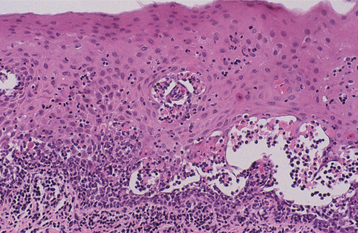

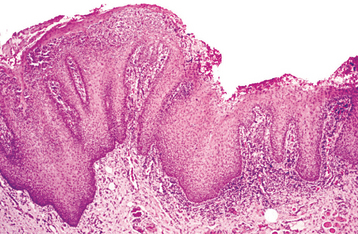

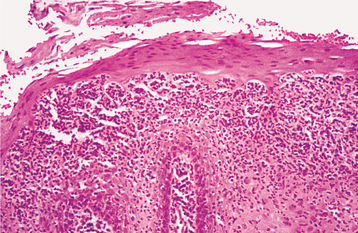

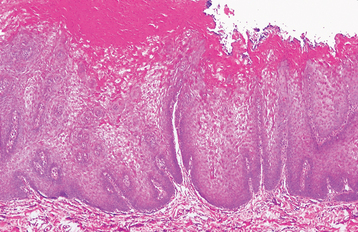

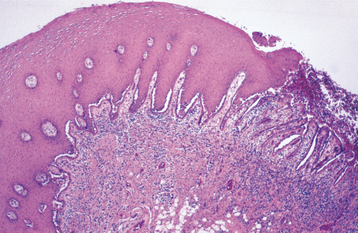

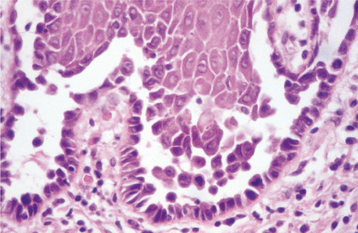

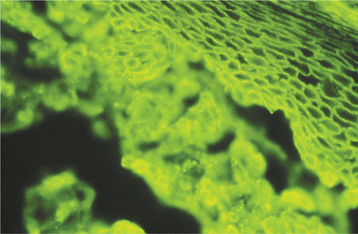

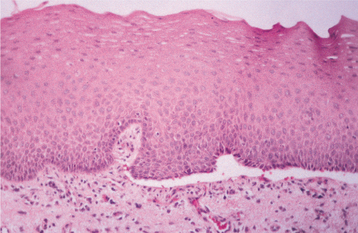

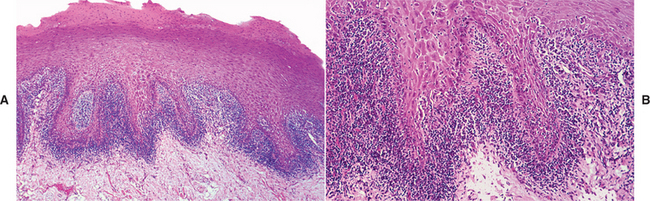

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The microscopic features of white sponge nevus are characteristic but not necessarily pathognomonic. Prominent hyperparakeratosis and marked acanthosis with clearing of the cytoplasm of the cells in the spinous layer are common features (Figs. 16-5 and 16-6); however, similar microscopic findings may be associated with leukoedema and hereditary benign intra-epithelial dyskeratosis (HBID). In some instances, an eosinophilic condensation is noted in the perinuclear region of the cells in the superficial layers of the epithelium, a feature that is unique to white sponge nevus. Ultrastructurally, this condensed material can be identified as tangled masses of keratin tonofilaments.

Fig. 16-5 White sponge nevus. This low-power photomicrograph shows prominent hyperparakeratosis, marked thickening (acanthosis), and vacuolation of the spinous cell layer.

Fig. 16-6 White sponge nevus. This high-power photomicrograph shows vacuolation of the cytoplasm of the cells of the spinous layer, with no evidence of epithelial atypia. Perinuclear condensation of keratin tonofilaments can also be observed in some cells.

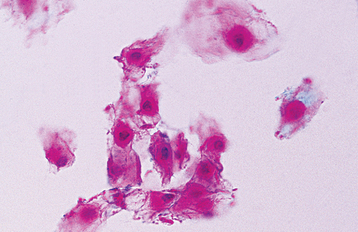

Exfoliative cytologic studies may provide more definitive diagnostic information. A cytologic preparation stained with the Papanicolaou method often shows the eosinophilic perinuclear condensation of the epithelial cell cytoplasm to a greater extent than does the histopathologic section (Fig. 16-7).

HEREDITARY BENIGN INTRAEPITHELIAL DYSKERATOSIS (WITKOP-VON SALLMANN SYNDROME)

Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis (HBID) is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatosis primarily affecting descendants of a triracial isolate (Native American, black, and white) of people who originally lived in North Carolina. Examples of HBID have sporadically been reported from other areas of the United States because of migration of affected individuals, and descriptions of affected patients with no apparent connection to North Carolina have also appeared in the literature.

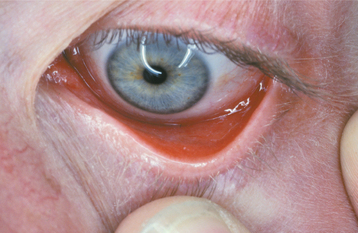

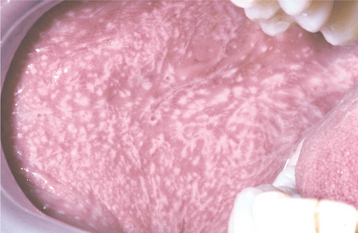

CLINICAL FEATURES: The lesions of HBID usually develop during childhood, in most instances affecting the oral and conjunctival mucosa. The oral lesions are similar to those of white sponge nevus, with both conditions showing thick, corrugated white plaques involving the buccal and labial mucosa (Fig. 16-8). Milder cases may exhibit the opalescent appearance of leukoedema. Other oral mucosal sites, such as the floor of the mouth and lateral tongue, may also be affected. These oral lesions may exhibit a superimposed candidal infection as well.

Fig. 16-8 Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis (HBID). Oral lesions appear as corrugated white plaques of the buccal mucosa. (Courtesy of Dr. John McDonald.)

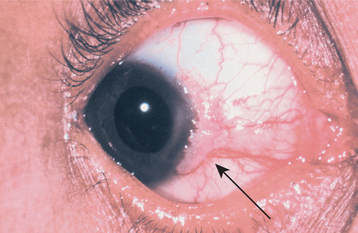

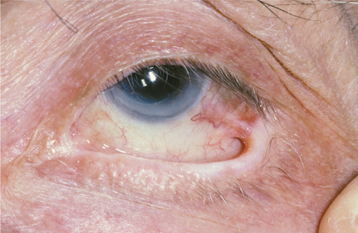

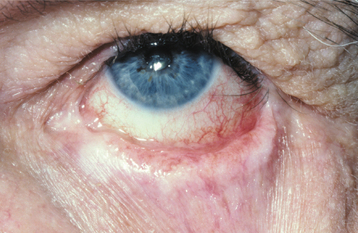

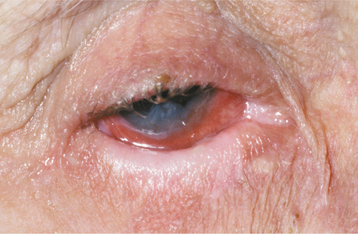

The most interesting feature of HBID is the ocular lesions, which begin to develop very early in life. These appear as thick, opaque, gelatinous plaques affecting the bulbar conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea (Fig. 16-9) and sometimes involving the cornea itself. When the lesions are active, patients may experience tearing, photophobia, and itching of the eyes. In many patients, the plaques are most prominent in the spring and tend to regress during the summer or autumn. Sometimes blindness may result from the induction of vascularity of the cornea secondary to the shedding process.

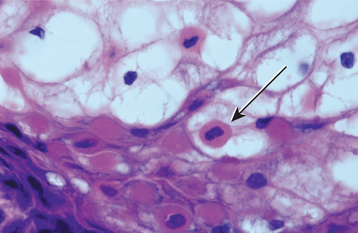

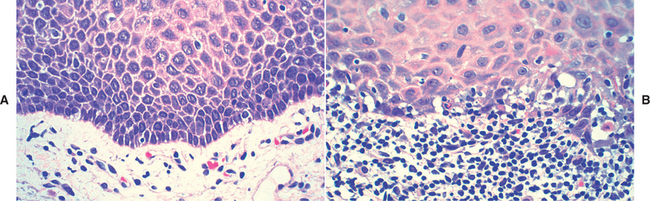

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic features of HBID include prominent parakeratin production in addition to marked acanthosis. A peculiar dyskeratotic process, similar to that of Darier’s disease, is scattered throughout the upper spinous layer of the surface oral epithelium (Fig. 16-10). With this dyskeratotic process, an epithelial cell appears to be surrounded or engulfed by an adjacent epithelial cell, resulting in the so-called cell-within-a-cell phenomenon.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Because HBID is a benign condition, no treatment is generally required or indicated for the oral lesions. If superimposed candidiasis develops, then an antifungal medication can be used. Patients with symptomatic ocular lesions should be referred to an ophthalmologist. Typically, the plaques that obscure vision must be surgically excised. This procedure, however, is recognized as a temporary measure because the lesions often recur.

PACHYONYCHIA CONGENITA (JADASSOHN-LEWANDOWSKY TYPE; JACKSON-LAWLER TYPE)

Pachyonychia congenita is a group of rare genodermatoses that are usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. The nails are dramatically affected in most patients, but oral lesions are seen only in patients affected by the Jadassohn-Lewandowsky form of the disease (pachyonychia congenita type 1). Fewer than 500 cases have been reported. Specific mutations in either the keratin 6a or keratin 16 gene have been detected for the Jadassohn-Lewandowsky type of pachyonychia congenita, whereas mutations of either the keratin 6b or keratin 17 gene are associated with the Jackson-Lawler form (pachyonychia congenita type 2).

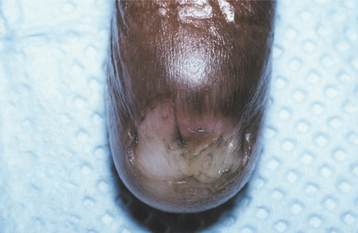

CLINICAL FEATURES: Virtually all patients with pachyonychia congenita exhibit characteristic nail changes, either at birth or in the early neonatal period. The free margins of the nails are lifted up because of an accumulation of keratinaceous material in the nail beds. This results in a pinched, tubular configuration. Ultimately, nail loss may occur (Fig. 16-11).

Other skin changes that may occur include marked hyperkeratosis of the palmar and plantar surfaces, producing thick, callouslike lesions (Fig. 16-12). Hyperhidrosis of the palms and soles is also commonly present. The rest of the skin shows punctate papules, representing an abnormal accumulation of keratin in the hair follicles. One disabling feature of the syndrome is the formation of painful blisters on the soles of the feet after a few minutes of walking during warm weather.

Fig. 16-12 Pachyonychia congenita. The soles of the feet of affected patients typically show marked calluslike thickenings. (Courtesy of Dr. Lou Young.)

The oral lesions seen in the Jadassohn-Lewandowsky form consist of thickened white plaques that involve the lateral margins and dorsal surface of the tongue. Other oral mucosal regions that are frequently exposed to mild trauma, such as the palate, buccal mucosa, and alveolar mucosa, may also be affected (Fig. 16-13). Neonatal teeth have been reported in patients affected by the Jackson-Lawler form, but these individuals do not have oral white lesions. Hoarseness and dyspnea have been described in some patients as a result of laryngeal mucosal involvement.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of lesional oral mucosa shows marked hyperparakeratosis and acanthosis with perinuclear clearing of the epithelial cells.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Because the oral lesions of pachyonychia congenita show no apparent tendency for malignant transformation, no treatment is required. The nails are often lost or may need to be surgically removed because of the deformity. In addition, the keratin accumulation on the palms and soles can be quite uncomfortable and distressing to many of the affected individuals. Most patients have to pay continuous attention to removal of the excess keratin, and issues related to quality of life often arise. Patients should receive genetic counseling, as an aid in family planning. Identification of the various keratin mutations associated with these disorders is now possible, using molecular techniques to evaluate material obtained from chorionic villus sampling, thereby allowing prenatal diagnosis.

DYSKERATOSIS CONGENITA (COLE-ENGMAN SYNDROME; ZINSSER-COLE-ENGMAN SYNDROME)

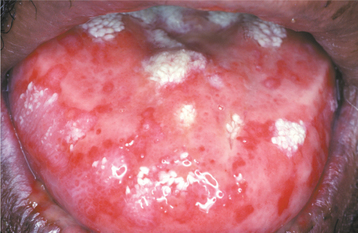

Dyskeratosis congenita is a rare genodermatosis that is usually inherited as an X-linked recessive trait, resulting in a striking male predilection. Autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive forms, although less common, have been reported. Mutations in the DKC1 gene have been determined to cause the X-linked form of dyskeratosis congenita. The mutated gene appears to disrupt the normal maintenance of telomerase, an enzyme that is critical in determining normal cellular longevity. The clinician should be aware of the condition because the oral lesions may undergo malignant transformation, and patients are susceptible to aplastic anemia.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Dyskeratosis congenita usually becomes evident during the first 10 years of life. A reticular pattern of skin hyperpigmentation develops, affecting the face, neck, and upper chest. In addition, abnormal, dysplastic changes of the nails are evident at this time (Fig. 16-14).

Intraorally, the tongue and buccal mucosa develop bullae; these are followed by erosions and, eventually, leukoplakic lesions (Fig. 16-15). The leukoplakic lesions are considered to be premalignant, and approximately one third of them become malignant in a 10- to 30-year period. The actual rate of transformation may be higher, but this may not be appreciated because of the shortened life span of these patients. Rapidly progressive periodontal disease has been reported sporadically.

Fig. 16-15 Dyskeratosis congenita. Atrophy and hyperkeratosis of the dorsal tongue mucosa are visible.

Thrombocytopenia is usually the first hematologic problem that develops, typically during the second decade of life, followed by anemia. Ultimately, aplastic anemia develops in approximately 70% of these patients (see page 580). Mild to moderate mental retardation may also be present. Generally, the autosomal recessive and X-linked recessive forms show a more severe pattern of disease expression.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsy specimens of the early oral mucosal lesions show hyperorthokeratosis with epithelial atrophy. As the lesions progress, epithelial dysplasia develops until frank squamous cell carcinoma evolves.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The discomfort of the oral lesions is managed symptomatically, and careful periodic oral mucosal ex-aminations are performed to check for evidence of malignant transformation. Routine medical evaluation is warranted to monitor the patient for the development of aplastic anemia. Selected patients may be considered for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation once the aplastic anemia is identified.

As a result of these potentially life-threatening complications, the prognosis is guarded. The average life span for the more severely affected patients is 32 years of age. The parents and the patient should receive genetic counseling, but identification of the DKC1 gene should allow for accurate confirmation of carriers of the gene and for prenatal diagnosis.

XERODERMA PIGMENTOSUM

Xeroderma pigmentosum is a rare genodermatosis in which numerous cutaneous malignancies develop at a very early age. The prevalence of the condition in the United States is estimated to be 1 in 250,000 to 500,000. The condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait and is caused by one of several defects in the excision repair and/or postreplication repair mechanism of DNA. As a result of the inability of the epithelial cells to repair ultraviolet (UV) light-induced damage, mutations in the epithelial cells occur, leading to the development of skin cancer at a rate 1000 to 4000 times what would normally be expected in people younger than 20 years of age.

CLINICAL FEATURES: During the first few years of life, patients affected by xeroderma pigmentosum show a markedly increased tendency to sunburn. Skin changes, such as atrophy, freckled pigmentation, and patchy depigmentation, soon follow (Fig. 16-16). In early childhood, actinic keratoses begin developing, a process that normally does not take place before 40 years of age. These lesions quickly progress to squamous cell carcinoma, with basal cell carcinoma also appearing; consequently, in most patients a nonmelanoma skin cancer develops during the first decade of life. Melanoma develops in about 5% of patients with xeroderma pigmentosum, but it evolves at a slightly later time. As a consequence of sun exposure, the head and neck region is the site most frequently affected by these cutaneous malignancies. Neurologic manifestations include subnormal intelligence in 80% of affected individuals.

Fig. 16-16 Xeroderma pigmentosum. The atrophic changes and pigmentation disturbances shown are characteristic of xeroderma pigmentosum.

Oral manifestations, which often occur before 20 years of age, include development of squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip and the tip of the tongue. This latter site is most unusual for oral cancer, and its involvement is again undoubtedly related to the increased sun exposure, however minimal, which this area receives in contrast to the rest of the oral mucosa.

The diagnosis of xeroderma pigmentosum is usually made when the patient is evaluated for the cutaneous lesions, because it is highly unusual for a very young person to have skin cancer. Because xeroderma pigmentosum is an autosomal recessive trait, a family history of the disorder is not likely to be present, but the possibility of a consanguineous relationship of the affected child’s parents should be investigated.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic features of xeroderma pigmentosum are relatively nonspecific, in that the cutaneous premalignant lesions and malignancies that occur are microscopically indistinguishable from those observed in unaffected patients.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of xeroderma pigmentosum is challenging because in most instances significant sun damage has already occurred by the time of diagnosis. Patients are advised to avoid sunlight and unfiltered fluorescent light and to wear appropriate protective clothing and sunscreens if they cannot avoid sun exposure. Before receiving dental treatment, a calibrated UV light meter should be used to evaluate the amount of UV light being emitted from various sources in the dental office, such as the examination light, the radiograph viewbox, computer screens in the area, fiber-optic lights, or lights that are used for curing composite restorations. Some authors have suggested that any reading greater than 0 nm/cm2 would be unacceptable. A dermatologist should evaluate the patient every 3 months to monitor the development of cutaneous lesions.

Topical chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., 5-fluorouracil) may be used to treat actinic keratoses. Nonmelanoma skin cancers should be excised conservatively, preferably with microscopically controlled excision (Mohs surgery) to preserve as much normal tissue as possible. Patients should also receive genetic counseling, because a high number of consanguineous marriages have been reported in some series.

The prognosis is still poor. Most patients die 30 years earlier than the normal population, either directly from cutaneous malignancy or from complications associated with the treatment of the cancer.

HEREDITARY MUCOEPITHELIAL DYSPLASIA

Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia is a rare disorder that may occur sporadically or may be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Approximately 30 cases have been reported. For reasons that are not entirely understood, the mucosal epithelial cells do not develop in a normal fashion, and for this reason the designation of dysplasia has been given. However, in this situation, no increased risk of malignant transformation is seen. When a cervical exfoliative cytologic preparation (“Pap smear”) is done, the epithelial cells that are harvested may be interpreted as appearing cytologically unusual or atypical; in the past, some female patients have been advised to undergo hysterectomy because of this misinterpretation. Consequently, accurate identification of this disorder is extremely important for these patients.

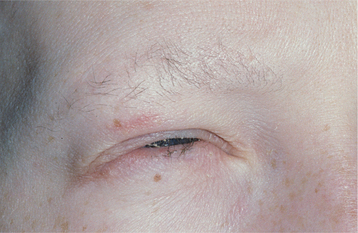

CLINICAL FEATURES: Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia is characterized by both cutaneous and mucosal abnormalities. Patients typically have sparse, coarse hair with nonscarring alopecia. Eyelashes and eyebrows are generally affected (Fig. 16-17). Severe photophobia develops at an early age, and most of these patients will have evidence of cataracts beginning in childhood or early adult life. Corneal vascularization, keratitis, and nystagmus are also commonly described. As would be expected, vision is usually markedly impaired for these patients. Other skin manifestations include a prominent perineal rash that appears during infancy, as well as a widespread rough, dry texture because of follicular keratosis.

Pulmonary complications related to mucoepithelial dysplasia can range in severity, presumably because of the degree of gene expression. In one family, cavitary bullae were reported to form within the lung parenchyma, and these led to recurrent bouts of pneumonia, often resulting in life-threatening complications.

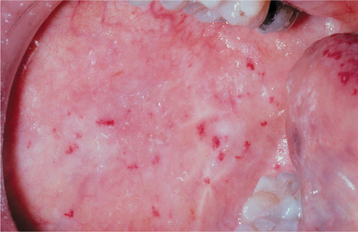

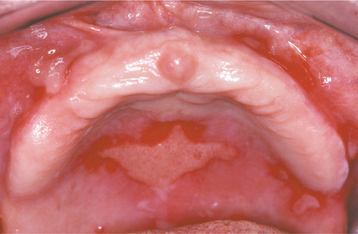

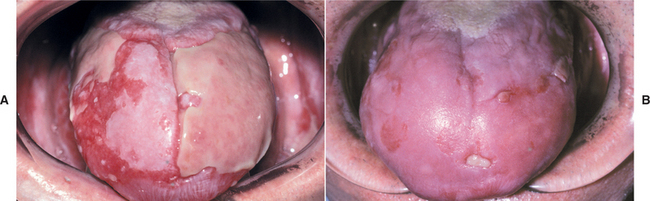

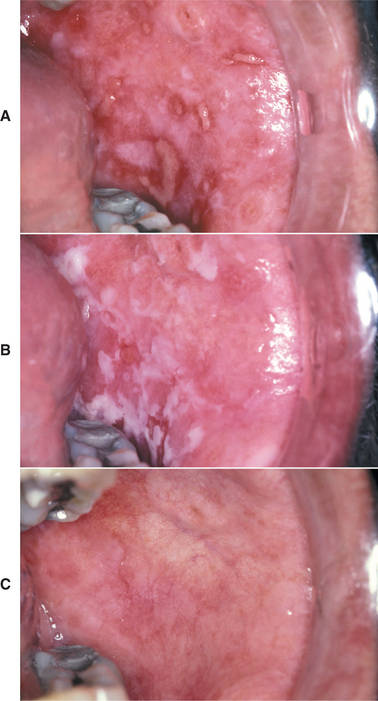

The oral manifestations of hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia are usually quite striking, appearing as demarcated fiery-red erythema of the hard palate (Fig. 16-18), with generally less involvement of the attached gingivae and tongue mucosa. These mucosal alterations are typically asymptomatic, despite their remarkable clinical appearance. The nasal, conjunctival, vaginal, cervical, urethral, and bladder mucosa may have the same unusual erythematous features.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsies of the mucosal lesions of hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia show epithelium with minimal keratinization and a disorganized maturation pattern. The squamous epithelial cells may have a relatively high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, but significant nuclear or cellular pleomorphism is not observed. Cytoplasmic vacuoles have been described and may appear as grayish inclusions (Fig. 16-19). These vacuoles also may be observed in exfoliative cytology samples. Ultrastructurally, the lesional cells have been described as having reduced numbers of desmosomes and internalized gap junctions.

INCONTINENTIA PIGMENTI (BLOCH-SULZBERGER SYNDROME)

Incontinentia pigmenti is a relatively rare inherited disorder, with approximately 800 cases reported worldwide. It typically evolves in several stages, primarily affecting the skin, eyes, and central nervous system (CNS), as well as oral structures. There is a marked female predilection, with a 37:1 female-to-male ratio reported. The condition is inherited as an X-linked dominant trait, with the single unpaired gene on the X chromosome being lethal for most males. The mutated gene responsible for producing the phenotypic features of incontinentia pigmenti maps to the Xq28 locus, where the genetic information related to nuclear factor-kB essential modulator (NEMO) is found. Of the few males who survive, a small percentage have Klinefelter syndrome (XXY karyotype), whereas the rest usually show mosaicism for the NEMO gene, suggesting a postzygotic mutation.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The clinical manifestations of incontinentia pigmenti usually begin in the first few weeks of infancy. There are four stages:

1. Vesicular stage—Vesiculobullous lesions appear on the skin of the trunk and limbs. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 4 months.

2. Verrucous stage—Verrucous cutaneous plaques develop, affecting the limbs. These clear by 6 months of age, evolving into the third stage.

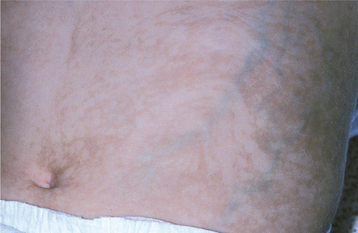

3. Hyperpigmentation stage—Macular, brown skin lesions appear, characterized by a strange swirling pattern (Fig. 16-20), although these tend to fade around the time of puberty.

4. Atrophy and depigmentation stage—Atrophy and depigmentation of the skin ultimately occur.

CNS abnormalities occur in approximately 30% of affected patients. The most common problems are mental retardation, seizure disorders, and motor difficulties. Ocular problems (e.g., strabismus, nystagmus, cataracts, retinal vascular abnormalities, optic nerve atrophy) may also be identified in nearly 35% of these patients.

The oral manifestations of incontinentia pigmenti, noted in 70% to 95% of the cases, include oligodontia (hypodontia), delayed eruption, and hypoplasia of the teeth (Fig. 16-21). The teeth are small and cone shaped; both the primary and permanent dentitions are affected.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The microscopic findings in incontinentia pigmenti vary, depending on when a biopsy of the skin lesions is performed.

In the initial vesicular stage, intraepithelial clefts filled with eosinophils are observed. During the verrucous stage, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis are noted. The hyperpigmentation stage shows numerous melanin-containing macrophages (melanin incontinence) in the subepithelial connective tissue, the feature from which the disorder derives its name.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of incontinentia pigmenti is directed toward the various abnormalities. Dental management includes appropriate prosthodontic and restorative care, although this is sometimes difficult if CNS problems are severe. Prenatal genetic testing can be performed, but currently this is not widely available.

DARIER’S DISEASE (KERATOSIS FOLLICULARIS; DYSKERATOSIS FOLLICULARIS; DARIER-WHITE DISEASE)

Darier’s disease is an uncommon genodermatosis with rather striking skin involvement and relatively subtle oral mucosal lesions. The condition is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, having a high degree of penetrance and variable expressivity. A lack of cohesion among the surface epithelial cells characterizes this disease, and mutation of a gene that encodes an intracellular calcium pump has been identified as the cause for abnormal desmosomal organization in the affected epithelial cells. Estimates of the prevalence of Darier’s disease in Northern European populations range from 1 in 36,000 to 1 in 100,000.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Patients with Darier’s disease have numerous erythematous, often pruritic, papules on the skin of the trunk and the scalp that develop during the first or second decade of life (Fig. 16-22). An accumulation of keratin, producing a rough texture, may be seen in association with the lesions, and a foul odor may be present as a result of bacterial degradation of the keratin. The process generally becomes worse during the summer months, either because of sensitivity of some patients to UV light or because increased heat results in sweating, which induces more epithelial clefting. The palms and soles often exhibit pits and keratoses. The nails show longitudinal lines, ridges, or painful splits.

The oral lesions are typically asymptomatic and are discovered on routine examination. The frequency of occurrence of oral lesions ranges from 15% to 50%. They consist of multiple, normal-colored or white, flat-topped papules that, if numerous enough to be confluent, result in a cobblestone mucosal appearance (Fig. 16-23). These lesions affect the hard palate and alveolar mucosa primarily, although the buccal mucosa or tongue may be occasionally involved. If the palatal lesions are prominent, then the condition may resemble inflammatory papillary hyperplasia or nicotine stomatitis. Some patients with this condition also experience recurrent obstructive parotid swelling secondary to duct abnormalities.

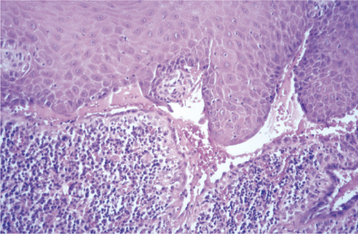

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of the cutaneous or mucosal lesions shows a dyskeratotic process characterized by a central keratin plug that overlies epithelium exhibiting a suprabasilar cleft (Fig. 16-24). This intraepithelial clefting phenomenon, also known as acantholysis, is not unique to Darier’s disease and may be seen in conditions such as pemphigus vulgaris (see page 765). In addition, the epithelial rete ridges associated with the lesions appear narrow, elongated, and “test tube”-shaped. Closer inspection of the epithelium reveals varying numbers of two types of dyskeratotic cells, called corps ronds (round bodies) or grains (because they resemble cereal grains).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of Darier’s disease depends on the severity of involvement. Photosensitive patients should use a sunscreen, and all patients should minimize unnecessary exposure to hot environments. For relatively mild cases, keratolytic agents or emollients may be the only treatment required. For more severely affected patients, systemic retinoids are often beneficial, but the side effects of such medications are often quite bothersome to the patient and can be significant; therefore, the physician should carefully monitor their use. Although the condition is not premalignant or otherwise life threatening, genetic counseling is appropriate.

WARTY DYSKERATOMA (ISOLATED DARIER’S DISEASE; ISOLATED DYSKERATOSIS FOLLICULARIS; FOCAL ACANTHOLYTIC DYSKERATOSIS; FOLLICULAR DYSKERATOMA)

The warty dyskeratoma is a distinctly uncommon solitary lesion that can occur on skin or oral mucosa. It is histopathologically identical to Darier’s disease. For this reason the lesion has been termed isolated Darier’s disease. The lesion is not otherwise related to Darier’s disease, however, and its cause remains unknown.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The cutaneous warty dyskeratoma typically appears as a solitary, asymptomatic, umbilicated papule on the skin of the head or neck of an older adult. The intraoral lesion also develops in patients older than age 40, and a slight male predilection has been identified. The intraoral warty dyskeratoma appears as a pink or white, umbilicated papule located on the keratinized mucosa, especially the hard palate and the alveolar ridge (Fig. 16-25). A warty or roughened surface is noted in some lesions. Most warty dyskeratomas are smaller than 0.5 cm in diameter.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Histopathologically, the warty dyskeratoma appears very similar to keratosis follicularis. Both conditions display dyskeratosis, basilar hyperplasia, and a suprabasilar cleft (Fig. 16-26). The warty dyskeratoma is a solitary lesion, however, and the formation of corps ronds and grains is not a prominent feature.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of the warty dyskeratoma consists of conservative excision. The prognosis is excellent; these lesions have not been reported to recur, and they have no apparent malignant potential. Careful histopathologic evaluation of the tissue should be performed, because some epithelial dysplasias may show a marked lack of cellular cohesiveness, resulting in a similar acantholytic appearance microscopically.

PEUTZ-JEGHERS SYNDROME

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a relatively rare but well-recognized condition, having a prevalence of approximately 1 in 100,000 to 200,000 births. It is characteri-zed by freckle-like lesions of the hands, perioral skin, and oral mucosa, in conjunction with intestinal polyposis and predisposition for affected patients to develop cancer. The syndrome is generally inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, although as many as 35% of cases represent new mutations. Mutation of the STK11 gene (also known as LKB1) on chromosome 19p13.3, which encodes for a serine/threonine kinase, is responsible for most cases of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

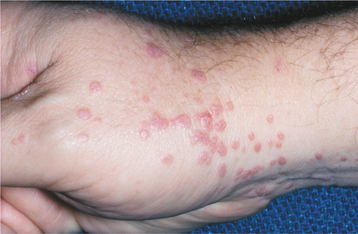

CLINICAL FEATURES: The skin lesions of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome usually develop early in childhood and involve the periorificial areas (e.g., mouth, nose, anus, genital region). The skin of the extremities is affected in about 50% of patients (Fig. 16-27). The lesions resemble freckles, but they do not wax and wane with sun exposure, as do true freckles.

Fig. 16-27 Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Cutaneous lesions appear as brown, macular, frecklelike areas, often concentrated around the mouth or on the hands. (Courtesy of Dr. Ahmed Uthman.)

The intestinal polyps, generally considered to be hamartomatous growths, are scattered throughout the mucus-producing areas of the gastrointestinal tract. The jejunum and ileum are most commonly affected. Patients often have problems with intestinal obstruction because of intussusception (“telescoping” of a proximal segment of the bowel into a distal portion), a problem that usually becomes evident during the third decade of life. Most of these episodes are self-correcting, but surgical intervention is sometimes necessary to prevent ischemic necrosis of the bowel, with subsequent peritonitis. Gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma develops in a significant percentage of affected patients, although the polyps themselves do not appear to be premalignant. In one large series of cases, 9% of the patients had developed gastrointestinal malignancy by 40 years of age and 33% by 60 years of age. This compares to 0.1% and 1.0%, respectively, in the general population. Other tumors affecting the pancreas, male and female genital tract, breast, and ovary may also develop. In women, the risk of developing breast cancer approaches 50% by 60 years of age. The increased frequency of malignancy in these patients overall is estimated to be approximately 18 times greater than normal.

The oral lesions essentially represent an extension of the perioral freckling. These 1- to 4-mm brown to blue-gray macules primarily affect the vermilion zone, the labial and buccal mucosa, and the tongue; they are seen in more than 90% of these patients (Fig. 16-28). The number of lesions and the extent of involvement can vary markedly from patient to patient. Some degree of fading of the pigmented lesions may be noted during adolescence.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The gastrointestinal polyps of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome histopathologically represent benign overgrowths of intestinal glandular epithelium supported by a core of smooth muscle. Epithelial atypia is not usually a prominent feature, unlike the polyps of Gardner syndrome (see page 651).

Microscopic evaluation of the pigmented cutaneous lesions shows slight acanthosis of the epithelium with elongation of the rete ridges. No apparent increase in melanocyte number is detected by electron microscopy, but the dendritic processes of the melanocytes are elongated. Furthermore, the melanin pigment appears to be retained in the melanocytes rather than being transferred to adjacent keratinocytes.

HEREDITARY HEMORRHAGIC TELANGIECTASIA (OSLER-WEBER-RENDU SYNDROME)

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is an uncommon mucocutaneous disorder that is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, and recent epidemiologic studies suggest a prevalence of at least 1 in 10,000 people. Mutation of either one of two different genes at two separate loci is responsible for the condition. HHT1 is caused by a mutation of the ENG (endoglin) gene on chromosome 9, whereas mutation of ALK1 (activin receptor-like kinase-1; ACVRL1), a gene located on chromosome 12, produces HHT2. The proteins produced by these genes may play a role in blood vessel wall integrity. With both types of HHT, numerous vascular hamartomas develop, affecting the skin and mucosa; however, other vascular problems, such as arteriovenous fistulas, may also be seen. Patients affected with HHT1 tend to have more pulmonary involvement, whereas those with HHT2 generally have a later onset of their telangiectasias and a greater degree of hepatic involvement. The clinician should be familiar with HHT because the oral lesions are often the most dramatic and most easily identified component of this syndrome.

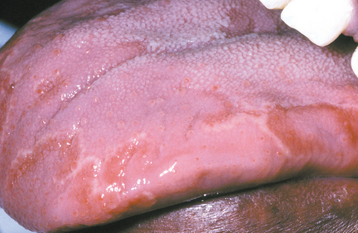

CLINICAL FEATURES: Patients with HHT are often diagnosed initially because of frequent episodes of epistaxis. On further examination, the nasal and oropharyngeal mucosae exhibit numerous scattered red papules, 1 to 2 mm in size, which blanch when diascopy is used. This blanching indicates that the red color is due to blood contained within blood vessels (in this case, small collections of dilated capillaries [telangiectasias] that are close to the surface of the mucosa). These telangiectatic vessels are most frequently found on the vermilion zone of the lips, tongue, and buccal mucosa, although any oral mucosal site may be affected (Figs. 16-29 and 16-30). With aging, the telangiectasias tend to become more numerous and slightly larger.

Fig. 16-29 Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). The tongue of this patient shows multiple red papules, which represent superficial collections of dilated capillary spaces.

Fig. 16-30 Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). Red macules similar to the tongue lesions are observed on the buccal mucosa.

In many patients, telangiectasias are seen on the hands and feet. The lesions are often distributed throughout the gastrointestinal mucosa, the genitourinary mucosa, and the conjunctival mucosa. The gastrointestinal telangiectasias have a tendency to rupture, which may cause significant blood loss. Chronic iron-deficiency anemia is often a problem for such individu als. Significantly, arteriovenous fistulas may develop in the lungs (30% of HHT patients), liver (30%), or brain (10% to 20%). The brain lesions seem to predispose these patients to the development of brain abscesses. In at least one instance, periodontal vascular malformations were felt to be the cause of septic pulmonary emboli that resolved only after several teeth with periodontal abscesses were extracted.

A diagnosis of HHT can be made if a patient has three of the following four criteria:

1. Recurrent spontaneous epistaxis

2. Telangiectasias of the mucosa and skin

3. Arteriovenous malformation involving the lungs, liver, or CNS

In some instances, CREST syndrome (Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysfunction, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasia) (see page 801) must be considered in the differential diagnosis. In these cases, serologic studies for anticentromere autoantibodies often help to distinguish between the two conditions because these antibodies typically would be present only in CREST syndrome.

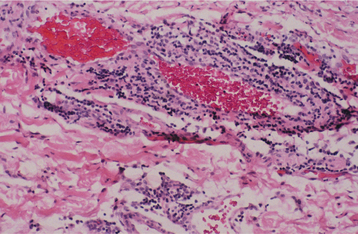

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: If one of the telangiectasias is submitted for biopsy, the microscopic features essentially show a superficially located collection of thin-walled vascular spaces that contain erythrocytes (Fig. 16-31).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: For mild cases of HHT, no treatment may be required. Moderate cases may be managed by selective cryosurgery or electrocautery of the most bothersome of the telangiectatic vessels. Laser ablation of the telangiectatic lesions has also been used, although this approach appears to be most successful for patients with mild to moderate disease. More severely affected patients, particularly those troubled by repeated episodes of epistaxis, may require a surgical procedure of the nasal septum (septal dermoplasty). The involved nasal mucosa is removed and replaced by a skin graft; however, some long-term follow-up studies suggest that the grafts eventually become revascularized, resulting in recurrence of the problem. Nasal closure is another surgical technique that has been performed for patients with severe epistaxis in whom other methods have failed.

Combined progesterone and estrogen therapy may benefit some patients, but because of the potentially serious side effects, this should be limited to the most severely affected individuals. Iron replacement therapy is indicated for the iron-deficient patient, and occasionally blood transfusions may be necessary to compensate for blood loss.

From a dental standpoint, some authors recommend the use of prophylactic antibiotics before dental procedures that might cause bacteremia in patients with HHT and evidence of a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. For patients with a history of HHT, such antibiotics are advocated until a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation is ruled out because of the 1% prevalence of brain abscesses in affected individuals. Researchers believe that antibiotic coverage, similar to that for endocarditis prophylaxis, may prevent this serious complication. Patients with a history of HHT should be screened for arteriovenous malformations, which can be eliminated by embolization or other vasodestructive techniques using interventional radiologic methods.

The prognosis is generally good, although a 1% to 2% mortality rate is reported from complications related to blood loss. For patients with brain abscesses, the mortality rate is 10%, even with early diagnosis and appropriate therapy.

EHLERS-DANLOS SYNDROMES

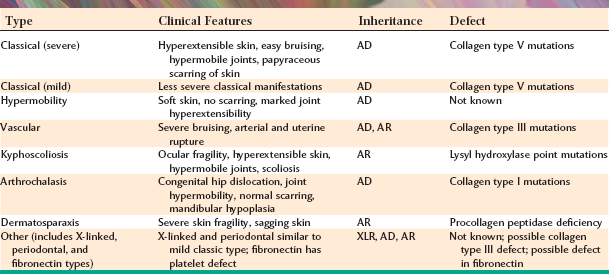

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, a group of inherited connective tissue disorders, are relatively heterogeneous. At least 10 types have been described over the years, but recent clinical and molecular evidence suggests that seven categories of this disease may be more appropriate. The patient exhibits problems that are usually attributed to the production of abnormal collagen, the protein that is the main structural component of the connective tissue. Because the production of collagen necessitates many biochemical steps that are controlled by several genes, the potential exists for any one of these genes to mutate, producing selective defects in collagen synthesis. The various forms of abnormal collagen result in many overlapping clinical features for each of the types of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (Table 16-1). This discussion concentrates on the most common and significant forms of this group of conditions.

Typical clinical findings include hypermobility of the joints, easy bruisability, and marked elasticity of the skin. Some patients have worked in circus sideshows as the “rubber” man and the “contortionist” as a result of their pronounced joint mobility and ability to stretch the skin.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The pattern of inheritance and the clinical manifestations vary with the type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome being examined. About 80% of patients have the classical type in either the mild or severe form. Classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, and defects of type I collagen have been reported in some families, whereas problems with type V collagen have been identified in others, suggesting genetic heterogeneity. Hyperelasticity of the skin (Fig. 16-32) and cutaneous fragility can be observed. An unusual healing response that often occurs with rela tively minor injury to the skin is termed papyraceous scarring because it resembles crumpled cigarette paper (Fig. 16-33).

Fig. 16-32 Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. The hyperelasticity of the skin is evident in this patient affected by the mild form of classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Fig. 16-33 Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Scarring that resembles crumpled cigarette paper (papyraceous scarring) is associated with minimal trauma in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. These lesions involve the skin of the knee.

Patients with the hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome exhibit remarkable joint hypermobility but no evidence of scarring.

The vascular type of Ehlers-Danlos used to be known as the ecchymotic type because of the extensive bruising that occurs with everyday trauma. Defects in type III collagen have been identified in this disorder. This form is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, and the patient may be mistaken for a victim of child abuse. The life expectancy of these patients is often greatly reduced because of the tendency for aortic aneurysm formation and rupture.

One rare form of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (originally reported as type VIII) was described as having dental manifestations as a hallmark feature, with patients showing marked periodontal disease activity at a relatively early age. Although these patients may have overlapping features with either the classical or vascular forms of the disease, recent studies examining five affected families in Sweden have suggested that this form of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is linked to a specific mutation of a gene that has been mapped to chromosome 12p13.

The oral manifestations of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome include the ability of 50% of these patients to touch the tip of their nose with their tongue (Gorlin sign), a feat that can be achieved by less than 10% of the general population. Some authors have noted easy bruising and bleeding during minor manipulations of the oral mucosa; others state that oral mucosal friability is present. A tendency for recurrent subluxation of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and the development of other TMJ disorders has also been reported.

Most patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome have normal teeth. A variety of dental abnormalities have been described, however, including malformed, stunted tooth roots, large pulp stones, and hypoplastic enamel. Although most of these findings have not been consistently correlated with any particular type of the syndrome, pulp stones seem to occur more commonly in patients affected by classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The prognosis for the patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome depends on the type. Some forms, such as the vascular type, can be very serious, with sudden death occurring from rupture of the aorta secondary to the weakened, abnormal collagen that constitutes the vessel wall. The mild classical type is generally compatible with a normal life span, although affected women may have problems with placental tearing and hemorrhage during gestation.

Accurate diagnosis is important because it affects the prognosis heavily. Similarly, because the various types of this syndrome show a variety of inheritance patterns, an accurate diagnosis is required so that appropriate genetic counseling can be provided.

TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS (EPILOIA; BOURNEVILLE-PRINGLE SYNDROME)

Tuberous sclerosis is an uncommon syndrome that is classically characterized by mental retardation, seizure disorders, and angiofibromas of the skin. The condition is often inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, but two thirds of the cases are sporadic and appear to represent new mutations. These mutations involve either one of two genes: TSC1 (found on chromosome 9) or, more commonly, TSC2 (found on chromosome 16). Both of these gene products are believed to contribute to the same intracellular biochemical pathway that seems to have a tumor suppressor function. The multiple hamartomatous growths that are seen in this disorder are thought to arise from disruption of the normal tumor suppressor function of these genes. Tuberous sclerosis has a wide range of clinical severity, although patients who have the TSC2 mutation have a more severe expression of the disease than patients who have the TSC1 mutation. Milder forms of tuberous sclerosis may be difficult to diagnose.

The prevalence is at least 1 in 10,000 in the general population, although in some long-term care facilities tuberous sclerosis accounts for as high as 1% of the mentally retarded patients.

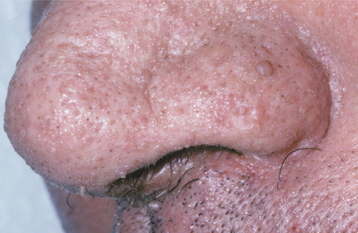

CLINICAL FEATURES: Several clinical features characterize tuberous sclerosis. The first of these, facial angiofibromas, used to be called adenoma sebaceum. Because these lesions are neither adenomas nor sebaceous, the use of that term should be discontinued. Facial angiofibromas appear as multiple, smooth-surfaced papules and occur primarily in the nasolabial fold area (Fig. 16-34). Similar lesions, called ungual or periungual fibromas, are seen around or under the margins of the nails (Fig. 16-35).

Fig. 16-34 Tuberous sclerosis. Patients typically have multiple papular facial lesions that microscopically are angiofibromas.

Two other characteristic skin lesions are connective tissue hamartomas called shagreen patches and ovoid areas of hypopigmentation called ash-leaf spots. Even though approximately 5% of the general population may have an ash-leaf spot, studies have reported that 60% to 97% of children with tuberous sclerosis display these lesions. The shagreen patches, so named because of their resemblance to sharkskin-derived shagreen cloth, affect the skin of the trunk. The ash-leaf spots may appear on any cutaneous surface and may be best visualized using UV (Wood’s lamp) illumination.

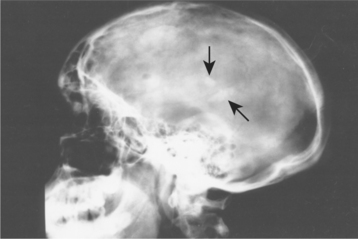

CNS manifestations include seizure disorders in 70% to 80% of affected patients and mental retardation in 33% to 45%. In addition, hamartomatous proliferations in the CNS develop into the potato-like growths (“tubers”) seen at autopsy, from which the term tuberous sclerosis is derived (Fig. 16-36). The tuberous hamartomas can best be visualized using T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and are present in 80% to 95% of these patients.

Fig. 16-36 Tuberous sclerosis. Patchy calcifications (arrows) associated with intracranial hamartoma formation are seen on this lateral skull radiograph. (Courtesy of Dr. Reg Munden.)

A relatively rare tumor of the heart muscle, called cardiac rhabdomyoma, is also typically associated with this syndrome. This lesion, which probably represents a hamartoma rather than a true neoplasm, occurs in approximately 30% to 50% of affected patients and is typically identified in childhood. Problems with myocardial function often develop as a result of this process, but many of these tumors undergo spontaneous regression.

Another hamartomatous type of growth related to this disorder is the angiomyolipoma. This is a benign neoplasm composed of vascular smooth muscle and adipose tissue and occurs primarily in the kidney.

Oral manifestations of tuberous sclerosis include developmental enamel pitting on the facial aspect of the anterior permanent dentition in 50% to 100% of patients. These pits are more readily appreciated after applying a dental plaque-disclosing solution to the teeth. Multiple fibrous papules affect 11% to 56% of patients. The fibrous papules are seen predominantly on the anterior gingival mucosa (Fig. 16-37), although the lips, buccal mucosa, palate, and tongue may be involved. Diffuse fibrous gingival enlargement is reported in affected patients who are not taking phenytoin; however, most cases of gingival hyperplasia in these individuals are probably related to medication taken to control seizures. Some patients with tuberous sclerosis may also exhibit radiolucencies of the jaws that represent dense fibrous connective tissue proliferations (Fig. 16-38).

Fig. 16-37 Tuberous sclerosis. Patients often exhibit gingival hyperplasia, which may be secondary to phenytoin medications used to control seizures in some cases. Fibrous papules of the gingiva (arrows) may also be present.

Fig. 16-38 Tuberous sclerosis. Periapical radiograph exhibiting a well-defined radiolucency apical to the maxillary left lateral incisor. Biopsy revealed an intraosseous fibrous proliferation.

The diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis can be based on finding at least two of the following major features:

The presence of one major and two minor features may also confirm the diagnosis. The minor features include the following:

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of the fibrous papules of the oral mucosa or the enlarged gingivae shows a nonspecific fibrous hyperplasia. Similarly, the radiolucent jaw lesions consist of dense fibrous connective tissue that resembles desmoplastic fibroma or the simple type of central odontogenic fibroma. The angiofibroma of the skin is a benign aggregation of delicate fibrous connective tissue characterized by plump, uniformly spaced fibroblasts with numerous interspersed thin-walled vascular channels.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: For patients with tuberous sclerosis, most of the treatment is directed toward the management of the seizure disorder with anticonvulsant agents. Periodic MRI of the head may be done to screen for intracranial lesions, whereas ultrasound evaluation is performed for evaluation of kidney involvement. Mentally retarded patients may have problems with oral hygiene procedures, and poor oral hygiene contributes to phenytoin-induced gingival hyperplasia. Patients affected by this condition have a slightly reduced life span compared with the general population, with death usually related to CNS or kidney disease. Genetic counseling is also appropriate for affected patients, and genetic testing is available for both TSC1 and TSC2 mutations if prenatal or preimplantation family planning is desired.

MULTIPLE HAMARTOMA SYNDROME (COWDEN SYNDROME; PTEN HAMARTOMA-TUMOR SYNDROME)

Multiple hamartoma syndrome is a rare condition that has important implications for the affected patient, because malignancies, in addition to the benign hamartomatous growths, develop in a high percentage of these individuals. Usually, the syndrome is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait showing a high degree of penetrance and a range of expressivity. The gene responsible for this disorder has been mapped to chromosome 10, and a mutation of the PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10) gene has been implicated in its pathogenesis. The estimated prevalence of this condition is approximately 1 in 200,000, and more than 300 affected patients have been described in the literature. In recent years, overlapping clinical features of multiple hamartoma syndrome with Lhermitte-Duclos disease, Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, and Proteus-like syndrome have been noted, and all of these disorders have demonstrated mutations of the PTEN gene.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Cutaneous manifestations are present in almost all patients with multiple hamartoma syndrome, usually developing during the second decade of life. The majority of the skin lesions appear as multiple, small (less than 1 mm) papules, primarily on the facial skin, especially around the mouth, nose, and ears (Fig. 16-39). Microscopically, most of these papules represent hair follicle hamartomas called trichilemmomas. Other commonly noted skin lesions are acral keratosis, a warty-appearing growth that develops on the dorsal surface of the hand, and palmoplantar keratosis, a prominent calluslike lesion on the palms or soles. Cutaneous hemangiomas, neuromas, xanthomas, and lipomas have also been described.

Fig. 16-39 Multiple hamartoma syndrome. These tiny cutaneous facial papules represent hair follicle hamartomas (trichilemmomas).

Other problems can appear in these patients as well. Thyroid disease usually appears as either a goiter or a thyroid adenoma, but follicular adenocarcinoma may develop. In women, fibrocystic disease of the breast is frequently observed. Unfortunately, breast cancer occurs with a relatively high frequency (25% to 50%) in these patients. The mean age at diagnosis of breast malignancy is 40 years, which is much younger than usual. In the gastrointestinal tract, multiple benign hamartomatous polyps may be present. In addition, several types of benign and malignant tumors of the female genitourinary tract occur more often than in the normal population.

The oral lesions vary in severity from patient to patient and usually consist of multiple papules affecting the gingivae, dorsal tongue, and buccal mucosa (Figs. 16-40 and 16-41). These lesions have been reported in more than 80% of affected patients and generally produce no symptoms. Other possible oral findings include a high-arched palate, periodontitis, and extensive dental caries, although it is unclear whether the latter two conditions are significantly related to the syndrome.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic features of the oral lesions are rather nonspecific, essentially representing fibroepithelial hyperplasia. Other lesions associated with this syndrome have their own characteristic histopathologic findings, depending on the hamartomatous or neoplastic tissue origin.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis can be based on the finding of two of the following three pathognomonic signs:

A variety of other major and minor diagnostic criteria, as well as a positive family history, are also helpful in confirming the diagnosis. Genetic testing for mutations of the PTEN gene are clinically available, but 20% of patients who otherwise have characteristic multiple hamartoma syndrome will not demonstrate a genetic abnormality; therefore, a negative test does not necessarily preclude the diagnosis of multiple hamartoma syndrome.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of multiple hamartoma syndrome is con-troversial. Although most of the tumors that develop are benign, the prevalence of malignancy is higher than in the general population; therefore, annual physical examinations that focus specifically on anatomic sites of increased tumor prevalence are appropriate. Some investigators recommend bilateral prophylactic mastectomies as early as the third decade of life for female patients because of the associated increased risk of breast cancer.

EPIDERMOLYSIS BULLOSA

The term epidermolysis bullosa describes a heterogeneous group of inherited blistering mucocutaneous disorders. Each has a specific defect in the attachment mechanisms of the epithelial cells, either to each other or to the underlying connective tissue. Recent advances in the understanding of the clinical, epidemiologic, and molecular genetic abnormalities of these conditions have led to the identification of approximately 25 different forms. Depending on the defective mechanism of cellular cohesion, there are four broad categories:

Each category consists of several forms of the disorder. A variety of inheritance patterns may be seen, depending on the particular form. The degree of severity can range from relatively mild, annoying forms, such as the simplex types, through a spectrum that includes severe, fatal disease. For example, many cases of junctional epidermolysis bullosa result in death at birth because of the significant sloughing of the skin during passage through the birth canal. Specific mutations in the genes encoding keratin 5 and keratin 14 have been identified as being responsible for most of the simplex types, whereas mutations in the genetic codes for the a3, b3, and g2 subunits of laminin have been documented for the junctional types. Most of the dystrophic types appear to be caused by mutations in the genes responsible for type VII collagen production, with nearly 200 distinctly different mutations identified to date. The hemidesmosomal type is the most recently characterized pattern of this group of disorders, and mutations of genes associated with various hemidesmosomal attachment proteins, such as plectin, type XVII collagen (BP180), and a6b4 integrin, have been established.

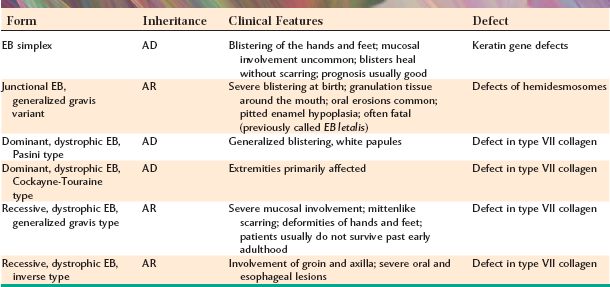

A few representative examples of the types of epidermolysis bullosa are summarized in Table 16-2. Because oral lesions are most commonly observed in the dystrophic forms, this discussion centers on these forms. Dental abnormalities, such as anodontia, enamel hypoplasia, pitting of the enamel, neonatal teeth, and severe dental caries, have been variably associated with several of the different types of epidermolysis bullosa, although studies have suggested that the prevalence of dental abnormalities is significantly increased only with the junctional type. A disorder termed epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is mentioned because of the similarity of its name; however, this appears to be an unrelated condition, having an autoimmune (rather than a genetic) origin (see page 744).

Table 16-2

Examples of Epidermolysis Bullosa

EB, Epidermolysis bullosa; AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive.

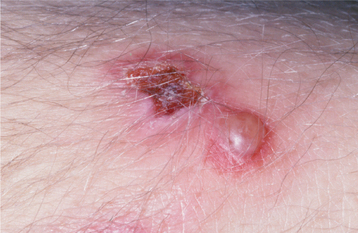

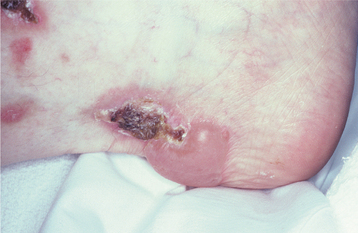

DOMINANT DYSTROPHIC TYPES: The dystrophic forms of epidermolysis bullosa that are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion are not usually life threatening, although they may certainly be disfiguring and pose many problems. The initial lesions are vesicles or bullae, which are seen early in life and develop on areas exposed to low-grade, chronic trauma, such as the knuckles or knees (Fig. 16-42). The bullae rupture, resulting in erosions or ulcerations that ultimately heal with scarring. In the process, appendages such as fingernails may be lost.

Fig. 16-42 Epidermolysis bullosa. A young girl, affected by the dominant dystrophic form of epidermolysis bullosa, shows the characteristic hemorrhagic bullae, scarring, and erosion associated with minimal trauma to the hands.

The oral manifestations are typically mild, with some gingival erythema and tenderness. Gingival recession and reduction in the depth of the buccal vestibule may be observed (Fig. 16-43).

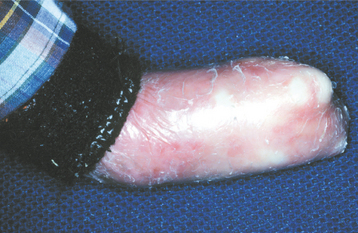

RECESSIVE DYSTROPHIC TYPES: Generalized recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa represents one of the more debilitating forms of the disease. Vesicles and bullae form with even minor trauma. Secondary infections are often a problem because of the large surface areas that may be involved. If the patient manages to survive into the second decade, then hand function is often greatly diminished because of the repeated episodes of cutaneous break down and healing with scarring, resulting in fusion of the fingers into a mittenlike deformity (Fig. 16-44).

Fig. 16-44 Epidermolysis bullosa. A 19-year-old man, affected by recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, shows the typical mittenlike deformity of the hand caused by scarring of the tissue after damage associated with normal activity.

The oral problems are no less severe. Bulla and vesicle formation is induced by virtually any food having some degree of texture. Even with a soft diet, the repeated cycles of scarring often result in microstomia (Fig. 16-45) and ankyloglossia. Similar mucosal injury and scarring may cause severe stricture of the esophagus. Because a soft diet is usually highly cariogenic, carious destruction of the dentition at an early age is common.

Fig. 16-45 Epidermolysis bullosa. Same patient as depicted in Fig. 16-44. Microstomia has been caused by repeated trauma and healing with scarring. Note the severe dental caries activity associated with a soft cariogenic diet.

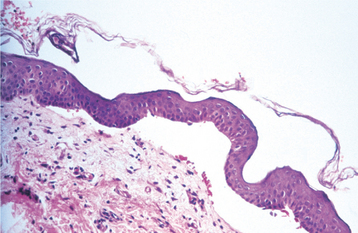

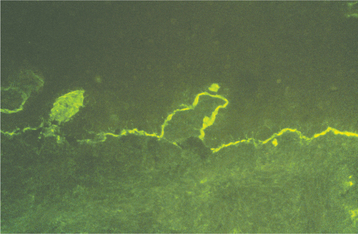

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic features of epidermolysis bullosa vary with the type being examined. The simplex form shows intraepithelial clefting by light microscopy. Junctional, dystrophic, and hemidesmosomal forms show subepithelial clefting (Fig. 16-46). Electron microscopic examination, which is still considered the diagnostic “gold standard,” reveals clefting at the level of the lamina lucida of the basement membrane in the junctional forms and below the lamina densa of the basement membrane in the dystrophic forms. In contrast, the hemidesmosomal form shows clefting just below the basal cell layer, at its interface with the lamina lucida. Immunohistochemical evaluation of perilesional tissue may help to identify specific defects to classify and subtype the condition further. Molecular genetic analysis is now being used to confirm the diagnosis in some instances.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa varies with the type. For milder cases, no treatment other than local wound care may be needed. Sterile drainage of larger blisters and the use of topical antibiotics are often indicated in these situations. For the more severe cases, intensive management with oral antibiotics may be necessary if cellulitis develops; despite intensive medical care, some patients die as a result of infectious complications.

The “mitten” deformity of the hands, seen in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, can be corrected with plastic surgery, but the problem usually recurs after a period of time, and surgical intervention is required every 2 years on average. With esophageal involvement, dysphagia may be a significant problem, resulting in malnutrition and weight loss. Placement of a gastrostomy tube may be necessary at times. Patients with the recessive dystrophic forms are also predisposed to development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. This malignancy often develops in areas of chronic ulceration during the second through third decades of life and represents a significant cause of death for these patients. Infrequently, the lingual mucosa of affected patients has been reported to undergo malignant transformation as well.

Management of the oral manifestations also depends on the type of the disease. For patients who are susceptible to mucosal bulla formation, dental manipulation should be kept to a minimum. To achieve this, topical 1% neutral sodium fluoride solution should be administered daily to prevent dental caries. A soft diet that is as noncariogenic as possible, as well as atraumatic oral hygiene procedures, should be encouraged. Maintaining adequate nutrition for affected patients is critical to ensure optimal wound healing.

If dental restorative care is required, the lips should be lubricated to minimize trauma. Injections for local anesthesia can usually be accomplished by depositing the anesthetic slowly and deeply within the tissues. For extensive dental care, endotracheal anesthesia may be performed without significant problems in most cases.

Unfortunately, because of the genetic nature of these diseases, no cure exists. Genetic counseling of affected families is indicated. Both prenatal diagnosis and preimplantation diagnosis are available as adjuncts to family planning.

Immune-Mediated Diseases and Their Evaluation

Several conditions discussed in this chapter are the result of inappropriate production of antibodies by the patient (autoantibodies). These autoantibodies are directed against various constituents of the molecular apparatus that hold epithelial cells together or that bind the surface epithelium to the underlying connective tissue. The ensuing damage produced by the interaction of these autoantibodies with the host tissue is seen clinically as a disease process, often termed an immunobullous disease. Because each disease is characterized by production of specific types of autoantibodies, identification of the antibodies and the tissues against which they are targeted is important diagnostically. The two techniques that are widely used to investigate the immunobullous diseases are (1) direct immunofluorescence and (2) indirect immunofluorescence studies. Following is a brief overview of how they work.

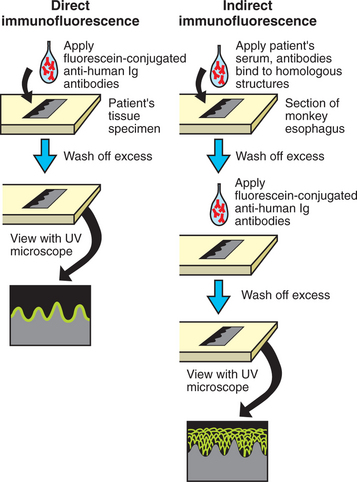

Direct immunofluorescence is used to detect autoantibodies that are bound to the patient’s tissue. Before testing can take place, several procedures must occur. Inoculating human immunoglobulins into a goat creates antibodies directed against these human immunoglobulins. The antibodies raised in response to the human immunoglobulins are harvested from the animal and tagged with fluorescein, a dye that glows when viewed with ultraviolet (UV) light. As illustrated on the left side of Fig. 16-47, a frozen section of the patient’s tissue is placed on a slide, and this is incubated with fluorescein-conjugated goat antihuman antibodies. These antibodies bind to the tissue at any site where human immunoglobulin is present. The excess antibody suspension is washed off, and the section is then viewed with a microscope having a UV light source.

Fig. 16-47 Immunofluorescence techniques. Comparison of the techniques for direct and indirect immunofluorescence. The left side depicts the direct immunofluorescent findings in cicatricial pemphigoid, a disease that has autoantibodies directed toward the basement zone. The right side shows the indirect immunofluorescent findings for pemphigus vulgaris, a disease that has autoantibodies directed toward the intercellular areas between the spinous cells of the epithelium. Ig, Immunoglobulin; UV, ultraviolet.

With indirect immunofluorescence studies, the patient is being evaluated for presence of antibodies that are circulating in the blood. As shown on the right side of Fig. 16-47, a frozen section of tissue that is similar to human oral mucosa (e.g., Old World monkey esophagus) is placed on a slide and incubated with the patient’s serum. If there are autoantibodies directed against epithelial attachment structures in the patient’s serum, then they will attach to the homologous structures on the monkey esophagus. The excess serum is washed off, and fluorescein-conjugated goat antihuman antibody is incubated with the section. The excess is washed off, and the section is examined with UV light to detect the presence of autoantibodies that might have been in the serum.

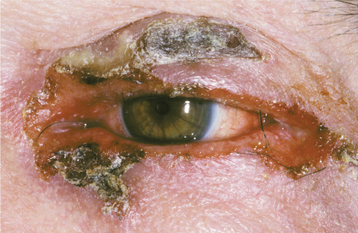

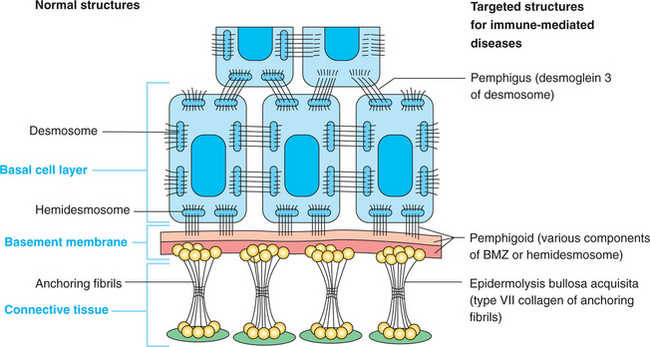

Examples of the molecular sites of attack of the autoantibodies are seen diagrammatically in Fig. 16-48. Each site is distinctive for a particular disease; however, the complexities of the epithelial attachment mechanisms are still being elucidated, and more precise mapping may be possible in the future. A summary of the clinical, microscopic, and immunopathologic features of the more important immune-mediated mucocutaneous diseases is found in Table 16-3.

Fig. 16-48 Epithelial attachment apparatus. Schematic diagram demonstrating targeted structures in several immune-mediated diseases. BMZ, Basement membrane zone.

PEMPHIGUS

The condition known as pemphigus represents four related diseases of an autoimmune origin:

Only the first two of these affect the oral mucosa, and the discussion is limited to pemphigus vulgaris. Pemphigus vegetans is rare; most authorities now feel it represents simply a variant of pemphigus vulgaris.

Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common of these disorders (vulgaris is Latin for common). Even so, it is not seen very often. The estimated incidence is one to five cases per million people diagnosed each year in the general population. Nevertheless, pemphigus vulgaris is an important condition because, if untreated, it often results in the patient’s death. Furthermore, the oral lesions are often the first sign of the disease, and they are the most difficult to resolve with therapy. This has prompted the description of the oral lesions as “the first to show, and the last to go.”

The blistering that typifies this disease is due to an abnormal production, for unknown reasons, of autoantibodies that are directed against the epidermal cell surface glycoproteins, desmoglein 3 and desmoglein 1. These desmogleins are components of desmosomes (structures that bond epithelial cells to each other), and the autoantibodies attach to these desmosomal components, effectively inhibiting the molecular interaction that is responsible for adherence. As a result of this immunologic attack on the desmosomes, a split develops within the epithelium, causing a blister to form. Desmoglein 3 is preferentially expressed in the parabasal region of the epidermis and oral epithelium, whereas desmoglein 1 is found primarily in the superficial portion of the epidermis, with minimal expression in oral epithelium. Patients who have developed autoantibodies directed against desmoglein 3, with or without desmoglein 1, will histopathologically show intraepithelial clefting just above the basal layer, and clinically oral mucosal blisters of pemphigus vulgaris will form. Patients who develop autoantibodies directed against only desmoglein 1 will histopathologically show superficial intraepithelial clefting of the epidermis, but oral mucosa will not be affected. Clinically, the fine scaly red lesions of pemphigus foliaceous or pemphigus erythematosus will be evident.

Occasionally, a pemphigus-like oral and cutaneous eruption may occur in patients taking certain medications (e.g., penicillamine, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) or in patients with malignancy, especially lymphoreticular malignancies (so-called paraneoplastic pemphigus) (see page 769). Similarly, a variety of other conditions may produce chronic vesiculoulcerative or erosive lesions of the oral mucosa, and these often need to be considered in the differential diagnosis (see Table 16-3). In addition, a rare genetic condition termed chronic benign familial pemphigus or Hailey-Hailey disease may have erosive cutaneous lesions, but oral involvement in that process appears to be uncommon.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The initial manifestations of pemphigus vulgaris often involve the oral mucosa, typically in adults. The average age at diagnosis is 50 years, although rare cases may be seen in childhood. No sex predilection is observed, and the condition seems to be more common in persons of Mediterranean, South Asian, or Jewish heritage.

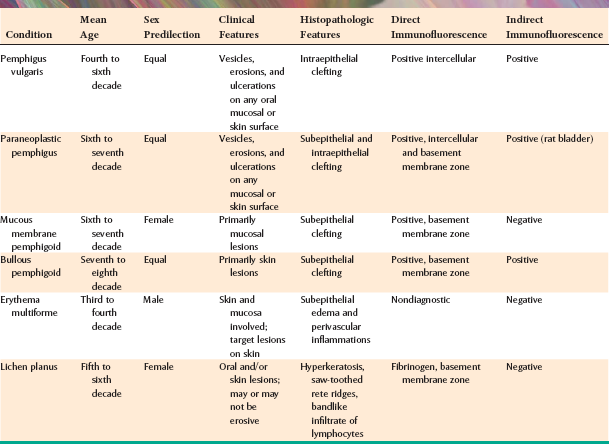

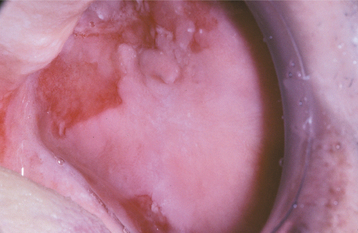

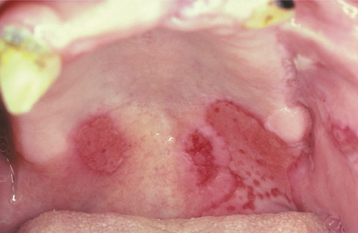

Patients usually complain of oral soreness, and examination shows superficial, ragged erosions and ulcerations distributed haphazardly on the oral mucosa (Figs. 16-49 to 16-52). Such lesions may affect virtually any oral mucosal location, although the palate, labial mucosa, buccal mucosa, ventral tongue, and gingivae are often involved. Patients rarely report vesicle or bulla formation intraorally, and such lesions can seldom be identified by the examining clinician, probably because of early rupture of the thin, friable roof of the blisters. More than 50% of the patients have oral mucosal lesions before the onset of cutaneous lesions, sometimes by as much as 1 year or more. Eventually, however, nearly all patients have intraoral involvement. The skin lesions appear as flaccid vesicles and bullae (Fig. 16-53) that rupture quickly, usually within hours to a few days, leaving an erythematous, denuded surface. Infrequently ocular involvement may be seen, usually appearing as bilateral conjunctivitis. Unlike cicatricial pemphigoid, the ocular lesions of pemphigus do not tend to produce scarring and symblepharon formation (see page 772).

Fig. 16-50 Pemphigus vulgaris. Large, irregularly shaped ulcerations involving the floor of the mouth and ventral tongue.

Fig. 16-52 Pemphigus vulgaris. The patient, with a known diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris, had been treated with immunosuppressive therapy. The oral erosions shown here were the only persistent manifestation of her disease.

Without proper treatment, the oral and cutaneous lesions tend to persist and progressively involve more surface area. A characteristic feature of pemphigus vulgaris is that a bulla can be induced on normal-appearing skin if firm lateral pressure is exerted. This is called a positive Nikolsky sign.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsy specimens of perilesional tissue show characteristic intraepithelial separation, which occurs just above the basal cell layer of the epithelium (Fig. 16-54). Sometimes the entire superficial layers of the epithelium are stripped away, leaving only the basal cells, which have been described as resembling a “row of tombstones.” The cells of the spinous layer of the surface epithelium typically appear to fall apart, a feature that has been termed acantholysis, and the loose cells tend to assume a rounded shape (Fig. 16-55). This feature of pemphigus vulgaris can be used in making a diagnosis based on the identification of these rounded cells (Tzanck cells) in an exfoliative cytologic preparation. A mild-to-moderate chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate is usually seen in the underlying connective tissue.

Fig. 16-54 Pemphigus vulgaris. Low-power photomicrograph of perilesional mucosa affected by pemphigus vulgaris. An intraepithelial cleft is located just above the basal cell layer.

Fig. 16-55 Pemphigus vulgaris. High-power photomicrograph showing rounded, acantholytic epithelial cells sitting within the intraepithelial cleft.

The diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris should be confirmed by direct immunofluorescence examination of fresh perilesional tissue or tissue submitted in Michel’s solution. With this procedure, antibodies (usually IgG or IgM) and complement components (usually C3) can be demonstrated in the intercellular spaces between the epithelial cells (Fig. 16-56) in almost all patients with this disease. Indirect immunofluorescence is also typically positive in 80% to 90% of cases, demonstrating the presence of circulating autoantibodies in the patient’s serum. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) have been developed to detect circulating autoantibodies as well.

Fig. 16-56 Pemphigus vulgaris. Photomicrograph depicting the direct immunofluorescence pattern of pemphigus vulgaris. Immunoreactants are deposited in the intercellular areas between the surface epithelial cells.

It is critical that perilesional tissue be obtained for both light microscopy and direct immunofluorescence to maximize the probability of a diagnostic sample. If ulcerated mucosa is submitted for testing, then the results are often inconclusive because of either a lack of an intact interface between the epithelium and connective tissue or a great deal of nonspecific inflammation.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: A diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris should be made as early in its course as possible because control is generally easier to achieve. Pemphigus is a systemic disease; therefore, treatment consists primarily of systemic corticosteroids (usually prednisone), often in combination with other immunosuppressive drugs (so-called steroid-sparing agents), such as azathioprine. Although some clinicians have advocated the use of topical corticosteroids in the management of oral lesions, the observed improvement is undoubtedly because of the absorption of the topical agents, resulting in a greater systemic dose. The potential side effects associated with the long-term use of systemic corticosteroids are significant and include the following: