Allergies and Immunologic Diseases

TRANSIENT LINGUAL PAPILLITIS

Transient lingual papillitis (lie bumps, tongue torches) represents a common oral pathosis that, for some reason, rarely has been documented. Affected patients experience clinical alterations that involve a variable number of fungiform papillae of the tongue. The pathogenesis currently is unknown, but the lesions most likely arise from a variety of influences. Suggested causes include local irritation, stress, gastrointestinal disease, hormonal fluctuation, upper respiratory tract infection, viral infection, and topical hypersensitivity to foods, drinks, or oral hygiene products.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Three patterns of transient lingual papillitis have been documented. The first pattern is localized and involves one to several fungiform papillae that become enlarged and present as elevated papules that are red but may demonstrate a yellow, ulcerated cap (Fig. 9-1). The lesions appear most frequently on the anterior portion of the dorsal surface, are associated with mild to moderate pain, and resolve spontaneously within hours to several days. In a survey of 163 dental school staff members, 56% reported previous episodes of transient lingual papillitis. There was a female predominance, and the vast majority reported a single affected papilla. In one report the occurrence of the lesions appeared to be associated with a food allergy.

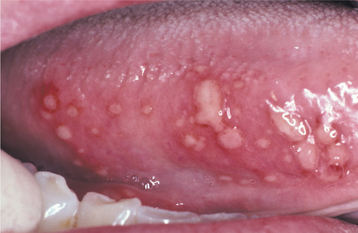

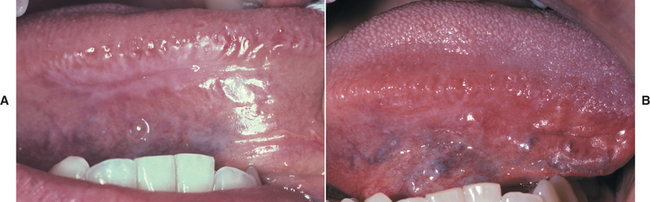

In the second pattern the involvement is more generalized and affects a large percentage of the fungiform papillae on the tip and lateral portions of the dorsal surface (Fig. 9-2). Individual papillae are very sensitive, enlarged, erythematous, and occasionally display focal surface erosion. Fever and cervical lymphadenopathy are not rare. In these cases, spread of the process among family members has been reported, suggesting a possible correlation to an unknown virus. Spontaneous resolution occurs in about 7 days, with occasional recurrences reported.

Fig. 9-2 Transient lingual papillitis. Multiple painful white papules on the lateral dorsum and tip of tongue.

The third pattern of transient lingual papillitis also demonstrates more diffuse involvement. The altered papillae are asymptomatic, appear as elevated white to yellow papules, and have been termed the papulokeratotic variant because of a thickened parakeratotic cap (Fig. 9-3). Although these lesions could be the result of a topical allergy, the histopathology demonstrates features similar to chronic nibbling and suggests the possibility of an unusual pattern of frictional hyperkeratosis.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: On histopathologic examination of the first two variants, affected papillae demonstrate normal surface epithelium that may reveal focal areas of exocytosis or ulceration. The underlying lamina propria exhibits a proliferation of numerous small vascular channels and a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate. Investigation for evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes simplex, and fungal infestation has been negative. The papulokeratotic variant demonstrates marked hyperparakeratosis in which the surface is ragged and reveals bacterial colonization. A chronic lymphocytic infiltrate is noted in the superficial lamina propria with extension into the basilar portion of the adjacent epithelium.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Although transient lingual papillitis resolves without therapy, topical corticosteroids, anesthetics, and coating agents have been used to reduce the pain or duration. In an attempt to eliminate the pain, occasional patients have reported removing the affected papillae with devices such as fingernail clippers. The papulokeratotic variant is asymptomatic and requires no therapy. Although frequently unsuccessful, search for a local or systemic triggering event seems prudent.

RECURRENT APHTHOUS STOMATITIS (RECURRENT APHTHOUS ULCERATIONS; CANKER SORES)

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis is one of the most common oral mucosal pathoses. The reported prevalence in the general population varies from 5% to 66%, with a mean of 20%. The hypotheses of its pathogenesis are numerous. As soon as one investigator claims to have discovered the definitive cause, a subsequent report discredits the discovery. Different subgroups of patients appear to have different causes for the occurrence of aphthae. These factors suggest a disease process that is triggered by a variety of causative agents, each of which is capable of producing the disease in certain subgroups of patients. To state it simply, the cause appears to be “different things in different people.”

Although no single triggering agent is responsible, the mucosal destruction appears to represent a T cell–mediated immunologic reaction. Analysis of the peripheral blood in patients with aphthae shows a decreased ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T lymphocytes, increased T cell–receptor γδ+ cells, and increased tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Many investigators agree that the epithelial destruction appears to be a local T cell–mediated response and involves T cells with TNF-α generated by these cells, macrophages, and mast cells. Evidence of the destruction of the oral mucosa mediated by these lymphocytes is strong, but the initiating causes are elusive and most likely highly variable.

The following all have been reported to be responsible in certain subgroups of patients (and each discounted in other subgroups!):

When all the various subgroups are combined, the various causes cluster into three categories:

One or more of these three factors may be involved in subgroups of patients.

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis demonstrates a definite tendency to occur along family lines. When both parents have a history of aphthous ulcers, there is a 90% chance that their children will develop the lesions. In addition, several investigators have shown an association with certain histocompatibility antigen (HLA) types in subgroups of patients. Stress, with its presumed effects on the immune system, directly correlates with the presence of aphthous stomatitis in some groups. In studies of professional students, recurrences clustered around stressful periods of the academic year; conversely, periods of vacation were associated with a low frequency of lesions.

Aphthouslike ulcerations have occurred in patients with systemic immunodysregulations. Patients with cyclic neutropenia (see page 583) occasionally have cycles of aphthouslike ulcerations that correspond to the periods of severe immunodysregulation. In addition, patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) have an increased frequency of severe aphthous stomatitis (see page 278), a fact that is not surprising considering the elevated CD8+/CD4+ ratio as the result of the reduction of CD4+ T lymphocytes.

The mucosal barrier appears to be important in the prevention of aphthous stomatitis and might explain the almost exclusive presence of aphthous stomatitis on nonkeratinized mucosa. Numerous factors that decrease the mucosal barrier increase the frequency of occurrence (e.g., trauma, nutritional deficiencies, smoking cessation); conversely, those associated with an increased mucosal barrier have been correlated with decreased ulcerations (e.g., smoking, hormonal changes, marked absence of aphthae on mucosa bound to bone). In a small subset of female patients, a negative association was reported between the occurrence of aphthae and the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle—a period of mucosal proliferation and keratinization. In addition, these same patients often experience ulcer-free periods during pregnancy.

An antigenic stimulus appears to be the primary initiating factor in the immune-mediated cytotoxic destruction of the mucosa in many patients. The list seems endless, and every item on the list may be important in small subsets of patients. Commonly mentioned potential antigens include sodium lauryl sulfate in toothpaste, many systemic medications (e.g., nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], various beta blockers, nicorandil), microbiologic agents (e.g., L forms of streptococci, Helicobacter pylori, herpes simplex virus [HSV], varicella-zoster virus [VZV], adenovirus, and cytomegalovirus [CMV]), and many foods (e.g., cheese, chocolate, coffee, cow’s milk, gluten, nuts, strawberries, tomatoes, dyes, flavoring agents, preservatives).

An increased prevalence of aphthouslike ulcerations has been noted in a variety of systemic disorders (Box 9-1). These ulcerations typically are identical clinically and histopathologically to those noted in otherwise healthy individuals. In many cases, resolution of the systemic disorder produces a decreased frequency and severity of the mucosal ulcerations.

Three clinical variations of aphthous stomatitis are recognized:

Minor aphthous ulcerations (Mikulicz’s aphthae) are the most common and represent the pattern present in more than 80% of those affected. Major aphthous ulcerations (Sutton’s disease or periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens [PMNR]) occur in approximately 10% of the patients referred for treatment. The remaining patients have herpetiform aphthous ulcerations. The minor and major forms most likely represent variations of the same process, although herpetiform aphthae demonstrate a unique pattern. Some investigators differentiate the herpetiform variant because of supposed evidence of a viral cause, but the proof is weak and does not justify its distinction from the other aphthous ulcerations. Some authors include Behçet’s syndrome as an additional variation of aphthous stomatitis, but this multisystem disorder is more complex and is considered later in this chapter.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Aphthous ulcerations are noted more frequently in children and young adults, with approximately 80% of affected individuals reporting their first ulceration before the age of 30. In one large series of 17,235 adults older than 17 years of age, the point prevalence of aphthous ulcerations was 0.89%, with the annual incidence in adults younger than 40 years old being almost twice that of older adults (22.5% versus 13.4%).

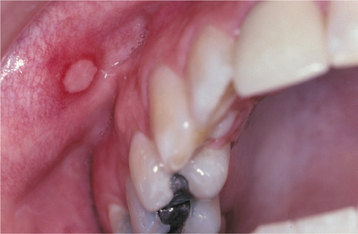

MINOR APHTHOUS ULCERATIONS: Patients with minor aphthous ulcerations experience the fewest recurrences, and the individual lesions exhibit the shortest duration of the three variants. The ulcers arise almost exclusively on nonkeratinized mucosa and may be preceded by an erythematous macule in association with prodromal symptoms of burning, itching, or stinging. The ulceration demonstrates a yellow-white, removable fibrinopurulent membrane that is encircled by an erythematous halo (Fig. 9-4). Classically, the ulcerations measure between 3 and 10 mm in diameter and heal without scarring in 7 to 14 days (Fig. 9-5). From one to five lesions typically are present during each episode, and the pain often is out of proportion for the size of the ulceration. The buccal and labial mucosae are affected most frequently, followed by the ventral surface of the tongue, mucobuccal fold, floor of the mouth, and soft palate (Fig. 9-6). Involvement of keratinized mucosa (e.g., hard palate, gingiva, dorsal surface of the tongue, and vermilion border) is rare and usually represents extension from adjacent nonkeratinized epithelium. The recur rence rate is highly variable, ranging from one ulceration every few years to two episodes per month.

Fig. 9-4 Minor aphthous ulceration. Erythematous halo encircling a yellowish ulceration of the lower labial mucosa. (Courtesy of Dr. Dean K. White.)

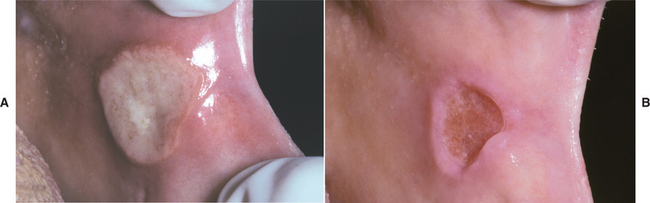

MAJOR APHTHOUS ULCERATIONS: Major aphthous ulcerations are larger than minor aphthae and demonstrate the longest duration per episode. The number of lesions usually is intermediate between that seen in the minor and herpetiform variants. The ulcerations are deeper than the minor variant, measure from 1 to 3 cm in diameter, take from 2 to 6 weeks to heal, and may cause scarring (Fig. 9-7). The number of lesions varies from 1 to 10. Any oral surface area may be affected, but the labial mucosa, soft palate, and tonsillar fauces are involved most commonly (Fig. 9-8). The onset of major aphthae is after puberty, and recurrent episodes may continue to develop for up to 20 years or more. With time, the associated scarring can become significant, and in rare instances may lead to a restricted mouth opening.

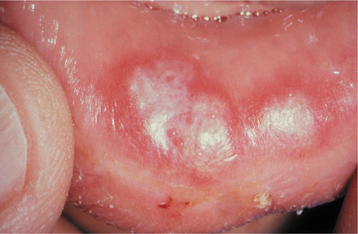

HERPETIFORM APHTHOUS ULCERATIONS: Herpetiform aphthous ulcerations demonstrate the greatest number of lesions and the most frequent recurrences. The individual lesions are small, averaging 1 to 3 mm in diameter, with as many as 100 ulcers present in a single recurrence. Because of their small size and large number, the lesions bear a superficial resemblance to a primary HSV infection, leading to the confusing designation, herpetiform. It is common for individual lesions to coalesce into larger irregular ulcerations (Fig. 9-9). The ulcerations heal within 7 to 10 days, but the recurrences tend to be closely spaced. Many patients are affected almost constantly for periods as long as 3 years. Although the nonkeratinized, movable mucosa is affected most frequently, any oral mucosal surface may be involved. There is a female predominance, and typically the onset is in adulthood.

Fig. 9-9 Herpetiform aphthous ulcerations. Numerous pinhead ulcerations of the ventral surface of the tongue, several of which have coalesced into larger, more irregular areas of ulceration.

Further classification of all three types is valuable when planning the most appropriate diagnostic evaluation and therapy. The lesions are diagnosed as simple aphthosis when they appear in patients with few lesions that heal within 1 to 2 weeks and recur infrequently. In contrast, patients with complex aphthosis have multiple (≥3) and almost constant oral ulcerations that often develop as older lesions resolve. Severe pain and large size are common. Although associated genital or perianal lesions also may be present, there is no other evidence of an associated systemic disease.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic picture of aphthous stomatitis is characteristic but not pathognomonic. The early ulcerative lesions demonstrate a central zone of ulceration, which is covered by a fibrinopurulent membrane. Deep to the area of ulceration, the connective tissue exhibits an increased vascularity and a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate that consists of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The epithelium at the margin of the lesion demonstrates spongiosis and numerous mononuclear cells in the basilar one third. A band of lymphocytes intermixed with histiocytes is present in the superficial connective tissue and surrounding deeper blood vessels.

DIAGNOSIS: No laboratory procedure provides definitive diagnosis. The diagnosis is made from the clinical presentation and from exclusion of other diseases that produce ulcerations that closely resemble aphthae (see Box 9-1). In patients with complex aphthous ulcerations, a systematic evaluation for an underlying trigger or associated systemic condition is prudent. In a review of 244 patients with complex aphthous ulcerations, an associated triggering condition (e.g., hematologic deficiency, gastrointestinal disease, immunodeficiency, drug reaction) was discovered in almost 60%. Because the histopathologic features are nonspecific, a biopsy is useful only in eliminating differential possibilities and is not beneficial in arriving at the definitive diagnosis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The patient’s medical history should be reviewed for signs and symptoms of any systemic disorder that may be associated with aphthouslike ulcerations. Most patients with mild aphthosis receive either no treatment, therapy with a number of over-the-counter anesthetics or protective bioadhesive products, or periodic topical medicaments that minimize the frequency and severity of the attacks.

In patients with mild disease, the mainstay of therapy is the use of topical corticosteroids, and the list of possible choices is long. Most patients with diffuse minor or herpetiform aphthae respond well to 0.01% dexamethasone elixir used in a rinse-and-expectorate method. Patients with localized ulcerations can be treated successfully with 0.05% augmented betamethasone dipropionate gel or 0.05% fluocinonide gel. Adrenal suppression does not occur with appropriate use of these medications. Major aphthous ulcerations are more resistant to therapy and often warrant more potent corticosteroids (Fig. 9-10). The individual lesions may be injected with triamcinolone acetonide or covered with 0.05% clobetasol propionate gel or 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment. Triamcinolone tablets also can be dissolved directly over the lesions. In hard-to-reach areas, such as the tonsillar pillars, beclomethasone dipropionate aerosol spray can be used. In resistant cases, systemic corticosteroids may be required to supplement the topical medications and gain control. In such instances, prednisolone or betamethasone syrup in a swish-and-swallow method is preferable to prednisone tablets. In this way the ulcerations will receive both topical and systemic therapy.

Fig. 9-10 Major aphthous ulceration. A, Large ulceration of the left anterior buccal mucosa. B, Same lesion after 5 days of therapy with betamethasone syrup used in a swish-and-swallow method. The patient was free of pain by the second day of therapy. The ulceration healed completely during the next week.

Numerous alternatives to corticosteroid agents have been used to treat patients suffering from aphthous ulcerations (the most widely accepted are highlighted in bold). Caution should be exercised, however, because many of these agents have not been examined in a double-blind, placebo-controlled fashion to assess the degree of effectiveness compared with placebo. Furthermore, some of these treatments may have significant side effects or may be quite expensive. Included within the list of therapies are acyclovir, amlexanox, topical 5-aminosalicylic acid, azelastine hydrochloride, benzydamine hydrochloride, carbenoxolone sodium, chemical cauterizing agents, chlorhexidine, colchicine, cyclosporine, dapsone, deglycyrrhizinated liquorice, gamma globulin, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxypropyl cellulose films, interferon-a, irsogladine maleate, levamisole, LongoVital, monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, pentoxifylline, prostaglandin E-2 gel, sucralfate, sodium cromoglycate (cromolyn), tacrolimus, tetracyclines, thalidomide, transfer factor (extract of immunocytes), triclosan, and vitamin and mineral supplements (especially zinc sulfate). The success of these therapies is highly variable. These treatments do not resolve the underlying problem and are merely an attempt to “beat back brush fires.” Recurrences often continue, although breaking up the cycle may induce longer disease-free intervals between attacks. Surgical removal of aphthous ulcerations has been used but is an inappropriate therapy. Although laser ablation shortens the duration and decreases associated symptoms, its use is of very limited practical benefit because patients cannot return on each recurrence.

Chemical cautery with silver nitrate continues to be suggested as an effective therapy, but it can no longer be recommended because of the numerous safer alternatives and its rare association with massive necrosis (see page 292) and systemic argyria (see page 315). An over-the-counter cautery that uses sulfuric acid and phenolic agents is indicated in certain situations, but patients must be warned of the potential for significant local tissue necrosis related to its misuse.

Patients with complex aphthosis require a more extensive evaluation for occult systemic disease and a search for possible triggers of the immune-mediated mucosal destruction. To go beyond the management of individual recurrences is difficult, expensive, and often frustrating. In spite of this, patients with severe disease should be offered the opportunity to investigate the underlying causes.

As previously mentioned, the immune attacks are usually a result of immunodysregulation, a decreased mucosal barrier, or an elevated antigenic stimulus. The evaluation for systemic disorders usually eliminates the first two causes. Typically, this is followed by patch tests for antigen stimuli or an elimination diet for possible offending foods. Therapeutic trials might be instituted against the viruses and bacteria that have been implicated in subsets of patients with aphthous stomatitis. The investigator should explain to the patient that the underlying causation is diverse; even with the most exhaustive search, the answer may be elusive. In many cases, stress appears involved, and all evaluations in these patients will be within normal limits. In spite of the high likelihood of an expensive and negative evaluation, discovery of an underlying abnormality that can be treated often leads to permanent resolution or dramatic improvement in the course of the recurrences.

BEHÇET’S SYNDROME (BEHÇET’S DISEASE; ADAMANTIADES SYNDROME)

The combination of chronic ocular inflammation and orogenital ulcerations was reported as early as the era of the ancient Greeks and later described in 1931 by a Greek ophthalmologist, Benedict Adamantiades. The classic triad was not delineated until 1937, when a Turkish dermatologist, Hulusi Behçet, defined the disease that bears his name. Although the disease has been traditionally thought primarily to affect the oral, genital, and ocular regions, it now is recognized to be a multisystem disorder.

Although no clear causation has been established, Behçet’s syndrome has an immunogenetic basis because of strong associations with certain HLA types. As in aphthous stomatitis, the disorder appears to be an immunodysregulation that may be primary or secondary to one or more triggers. Investigators have correlated attacks to a number of environmental antigens, including bacteria (especially streptococci), viruses, pesticides, and heavy metals.

Histocompatibility antigen B-51 (HLA-B51) has been linked closely to Behçet’s syndrome, and the frequency of both the disease (approximately 1 in 1000) and the haplotype is high in Turkey, Japan, and the Eastern Mediterranean countries. This distribution appears correlated to the ancient “Silk Route” that extended from China to Rome and was traveled by the Turks. Sexual reproduction between immigrants and locals along the route appears to have spread the genetic vulnerability. Interestingly, when predisposed populations migrate to nonendemic locations, the prevalence decreases, suggesting environmental factors also are involved.

CLINICAL FEATURES: As mentioned previously, the highest prevalence occurs in the Middle East and Japan, with a much lower frequency noted in northern Europe, the United States, and the United Kingdom. At the time of discovery, most patients are young adults, with the disease diagnosed uncommonly in blacks, children, and older adults.

Oral involvement is an important component of Behçet’s syndrome, and it is the first manifestation in 25% to 75% of the cases. Oral lesions occur at some point during the disease in 99% of the patients and typically precede other sites of involvement.

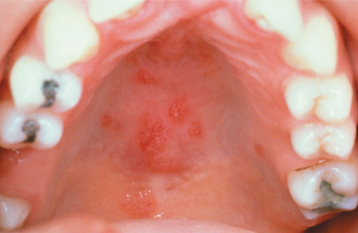

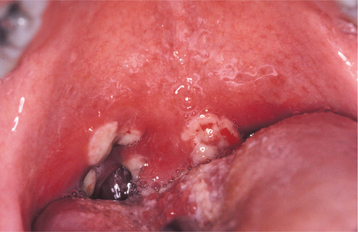

The lesions are similar to aphthous ulcerations occurring in otherwise healthy individuals and demonstrate the same duration and frequency. In spite of this, investigators have shown several statistically significant clinical variations that are different from typical aphthous ulcerations and may be used to increase the index of suspicion for Behçet’s syndrome. When compared with patients with aphthae, a larger percentage of those with Behçet’s syndrome demonstrate six or more ulcerations. The lesions commonly involve the soft palate and oropharynx, which are usually infrequent sites for the occurrence of routine aphthae. The individual lesions vary in size, have ragged borders, and are surrounded by a larger zone of diffuse erythema (Fig. 9-11).

Fig. 9-11 Behçet’s syndrome. Diffuse erythema surrounding numerous irregular ulcerations of the soft palate.

All three forms of oral aphthous stomatitis may be seen. Although the majority of affected patients have lesions that resemble minor aphthous ulcerations, some reports have documented a prevalence of major aphthae that approaches 40% in patients affected with Behçet’s syndrome. The herpetiform variant remains uncommon and is noted in approximately 3%. Patients with major aphthae often demonstrate more frequent recurrences and more ulcerations per relapse. In spite of more severe oral disease, the presence of major aphthae in Behçet’s syndrome does not correlate with an increased risk for more severe systemic expression.

The genital lesions are similar in appearance to the oral ulcerations. They occur in 75% of the patients and appear on the vulva, vagina, glans penis, scrotum, and perianal area (Fig. 9-12). These lesions recur less frequently than do the oral ulcerations, are deeper, and tend to heal with scarring. The genital ulcerations cause more symptoms in men than in women andmay be discovered only by a routine examination in women.

Fig. 9-12 Behçet’s syndrome. Numerous irregular ulcerations of the labia majora and perineum. (From Helm TN, Camisa C, Allen C et al: Clinical features of Behçet’s disease, Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 72:30, 1991.)

Common cutaneous lesions include erythematous papules, vesicles, pustules, pyoderma, folliculitis, acneiform eruptions, and erythema nodosum–like lesions. From a diagnostic standpoint, one of the most important skin manifestations is the presence of positive “pathergy.” One or 2 days after the oblique insertion of a 20-gauge or smaller needle under sterile conditions, a tuberculin-like skin reaction or sterile pustule develops (Fig. 9-13). This skin hyperreactivity (pathergy) appears to be unique to Behçet’s syndrome and is present in 40% to 88% of patients with this disorder.

Fig. 9-13 Behçet’s syndrome. Sterile pustule of the skin that developed 1 day after injection of saline. This reaction is termed cutaneous pathergy.

Ocular involvement is present in 70% to 85% of the cases and is more frequent and severe in males. The most common findings are posterior uveitis, conjunctivitis, corneal ulceration, papilledema, and arteritis. Although Behçet originally described hypopyon (pus in the anterior chamber) as a cause of blindness, this finding currently is rare. The most common secondary ocular complications are cataracts, glaucoma, and neovascularization of the iris and retina.

Arthritis is one of the more common minor manifestations of the disease and is usually self-limiting and nondeforming. The knees, wrists, elbows, and ankles are affected most frequently.

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is not common but, when present, is associated with a poor prognosis. From 10% to 25% of the patients demonstrate CNS involvement, and the alterations produced result in a number of changes that include paralysis and severe dementia.

Other alterations may be seen that involve the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, hematologic, pulmonary, muscular, and renal systems. These most likely occur secondary to vasculitis and create a variety of clinical presentations.

DIAGNOSIS: No laboratory finding is diagnostic of Behçet’s syndrome. In an attempt to standardize diagnoses, definitive criteria have been developed. Table 9-1 delineates the requirements proposed by the Behçet’s International Study Group. Although this system is used widely, many authorities exclude acneiform skin lesions in young adults from the criteria because of the high prevalence of this finding in an otherwise normal population.

Table 9-1

International Study Group Criteria for the Diagnosis of Behçet’s Disease

| Recurrent oral ulceration | Minor, major, or herpetiform aphthae |

| Plus two of the following: | |

| Recurrent genital ulcerations | Aphthaelike ulcerations |

| Eye lesions | Anterior or posterior uveitis, cells in vitreous on slit-lamp examination, or retinal vasculitis |

| Skin lesions | Erythema nodosum, pseudofolliculitis or papulopustular lesions, or acneiform nodules noted in postadolescent patients not receiving corticosteroids |

| Positive pathergy test | Read by physician at 24-48 hours |

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic features are not specific for Behçet’s syndrome and can be seen in many disorders, including aphthous stomatitis. The pattern most frequently seen is called leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The ulceration is similar in appearance to that seen in aphthous stomatitis, but the small blood vessels classically demonstrate intramural invasion by neutrophils, karyorrhexis of neutrophils, extravasation of red blood cells, and fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The oral and genital ulcerations typically respond well to potent topical or intralesional corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus. In more severe cases, this therapy can be combined with oral colchicine or dapsone. Patients who fail this initial conservative approach often respond to thalidomide, low-dose methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, or infliximab (anti–TNF-α antibody). Severe ocular or systemic disease often necessitates combined use of systemic immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory agents (e.g., corticosteroids, cyclosporine, azathioprine, interferon-a2a, cyclophosphamide).

Behçet’s syndrome has a highly variable course. A relapsing and remitting pattern is typical, with attacks becoming more intermittent after 5 to 7 years. The major morbidity and mortality of the disease appear confined to the years immediately after the initial diagnosis; therefore, early aggressive therapy is recommended for patients with severe clinical manifestations. Mortality is typically low; when noted, it most frequently is secondary to pulmonary hemorrhage, CNS hemorrhage, or bowel perforation. In the absence of CNS disease or significant vascular complications, the prognosis is generally good.

SARCOIDOSIS

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown cause. Jonathan Hutchinson initially described the disease in 1875, but Boeck coined the term sarcoidosis (Greek meaning “fleshlike condition”) 14 years later. The evidence implicates improper degradation of antigenic material with the formation of noncaseating granulomatous inflammation. The nature of the antigen is unknown, and probably several different antigens may be responsible. Possible involved antigens include infectious agents (e.g., mycobacterium, propionibacteria, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 8 [HHV-8]) and a number of environmental factors (e.g., wood dust, pollen, clay, mold, silica). The inappropriate defense response may result from prolonged or heavy antigenic exposure, an immunodysregulation (genetic or secondary to other factors) that prevents an adequate cell-mediated response, a defective regulation of the initial immune reaction, or a combination of all three of these factors. Several investigators have confirmed a genetic predisposition and positive associations with certain HLA types.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Sarcoidosis has a worldwide distribution but is recognized more commonly in the developed world. In North America, blacks are affected 10 to 17 times more frequently than whites. There is a slight female predominance, and the disease exhibits a bimodal age distribution, with the first peak between 25 and 35 years of age and the second peak between 45 and 65 years of age.

Sarcoidosis most commonly appears acutely over a period of days to weeks, and the symptoms are variable. Common clinical symptoms include dyspnea, dry cough, chest pain, fever, malaise, fatigue, arthralgia, and weight loss. Less frequently, sarcoidosis arises insidiously over months to years, without significant symptoms; when clinically evident, pulmonary symptoms are most common. Approximately 20% of patients have no symptoms, and the disease is discovered on routine chest radiographs.

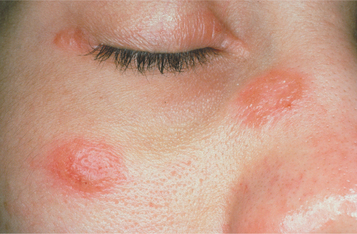

Although any organ may be affected, the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, eyes, and salivary glands are the predominant sites. Lymphoid tissue is involved in almost all cases. The mediastinal and paratracheal lymph nodes are involved commonly, and chest radiographs frequently reveal bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Approximately 90% of affected patients will reveal an abnormal chest radiograph sometime during the course of the disease. Cutaneous manifestations occur about 25% of the time. These often appear as chronic, violaceous, indurated lesions that are termed lupus pernio and frequent the nose, ears, lips, and face (Fig. 9-14). Symmetrical, elevated, indurated, purplish plaques also are seen commonly on the limbs, back, and buttocks. Scattered, nonspecific, tender erythematous nodules, known as erythema nodosum, frequently occur on the lower legs.

Fig. 9-14 Sarcoidosis. Violaceous indurated plaques of the right malar area and bridge of nose. (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

Ocular involvement is noted in 25% of the cases and most often appears as anterior uveitis. Lesions of the conjunctiva and retina may occur. Involvement of the lacrimal glands often produces keratoconjunctivitis sicca; the salivary glands can be altered similarly, with resultant clinical enlargement and xerostomia. Significant enlargement can occur in any major or minor salivary gland. Removal of intraoral mucoceles that occur in the salivary glands affected by the granulomatous process has led to the initial diagnosis in some cases. The salivary gland enlargement, xerostomia, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca can combine to mimic SjÖgren syndrome (see page 466).

Although lymphoid, pulmonary, cutaneous, and ocular lesions are most common, virtually any organ system may be affected. Other potential sites include the endocrine system, gastrointestinal tract, heart, kidneys, liver, nervous system, and spleen. Intraosseous lesions may occur and most commonly involve the phalanges, metacarpals, and metatarsals. Less frequently, the skull, nasal bones, ribs, and vertebrae are affected.

Two distinctive clinical syndromes are associated with acute sarcoidosis. LÖfgren’s syndrome consists of erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia. Patients with Heerfordt’s syndrome (uveoparotid fever) have parotid enlargement, anterior uveitis of the eye, facial paralysis, and fever.

If salivary gland and lymph node involvement are excluded, clinically evident oral manifestations in sarcoidosis are uncommon. Any oral mucosal site can be affected, most often appearing as a submucosal mass, an isolated papule, an area of granularity, or an ulceration. The mucosal lesions may be normal in color, brown-red, violaceous, or hyperkeratotic (Figs. 9-15 and 9-16). The most frequently affected intraoral soft tissue site is the buccal mucosa, followed by the gingiva, lips, floor of mouth, tongue, and palate. Most cases appearing in the floor of the mouth involve salivary glands and create mucus extravasation. Intraosseous lesions affect either jaw and represent approximately one fourth of all reported intraoral cases. Of these cases, most appeared as ill-defined radiolucencies that occasionally eroded the cortex but never created expansion. In a literature review of 45 reported cases of intraoral sarcoidosis, the oral lesion was the first documented clinical manifestation of the disease in the majority of patients.

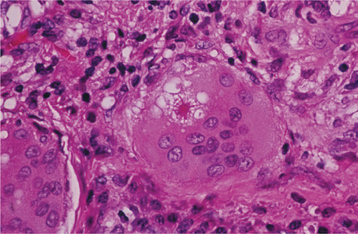

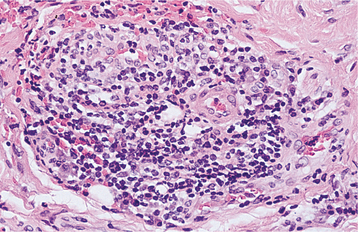

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of sarcoidosis exhibits a classic picture of granulomatous inflammation. Tightly clustered aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes are present, with a surrounding rim of lymphocytes. Intermixed with the histiocytes are scattered Langhans’ or foreign body type giant cells (Fig. 9-17). The granulomas often contain laminated basophilic calcifications, known as Schaumann bodies (degenerated lysosomes), or stellate inclusions, known as asteroid bodies (entrapped fragments of collagen) (Fig. 9-18). In lymph nodes, small yellow-brown structures called Hamazaki-Wesenberg bodies (large lysosomes) may be noted in the subcapsular sinus. None of these structures are specific for sarcoidosis. Special stains for fungal and bacterial organisms are negative. No polarizable, dissolvable, or pigmented foreign material can be detected.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis is established by the clinical and radiographic presentations, the histopathologic appearance, and the presence of negative findings with both special stains and cultures for organisms. Elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels and appropriate documentation of pulmonary involvement strongly support the diagnosis. Other laboratory abnormalities that may be seen include eosinophilia; leukopenia; anemia; thrombocytopenia; and elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum calcium concentration, and urinary calcium level.

A skin test for sarcoidosis, the Kveim test, can be performed by intradermal injection of a sterilized suspension of human sarcoid tissue. The procedure is no longer widely used because of difficulty in obtaining material for the test, concern related to its accuracy, and the inability to guarantee the absence of contamination (e.g., prions) in this human tissue.

Minor salivary gland biopsy has been promoted as a diagnostic aid in suspected cases of sarcoidosis (see Fig. 9-17). Investigators have documented success rates between 38% and 58%. The misdiagnosis of SjÖgren syndrome from minor salivary gland biopsy specimens has been reported in patients with sarcoidosis. Previously, biopsy of the parotid was avoided because of the fear of salivary fistula formation and damage to the facial nerve. These concerns have been reduced through biopsy of the posterior superficial lobe of the parotid gland, and confirmation of sarcoidosis has been reported in 93% of patients from this procedure.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: In approximately 60% of patients with sarcoidosis, the symptoms resolve spontaneously within 2 years without treatment. Most initial diagnoses are followed by a 3- to 12-month period of observation to define the general course of the disease. Active intervention is recommended for progressive disease and patients with cardiac or neurologic involvement, hypercalcemia, disfiguring skin disease, or serious ocular lesions that do not respond to local therapy. In patients requiring treatment, corticosteroids remain first-line therapy, but resistance and relapses are common. Medications used in patients with refractory disease include methotrexate, azathioprine, chlorambucil, and cyclophosphamide. Several studies have shown promising results with TNF-α antagonists such as etanercept, infliximab, pentoxyphylline, and thalidomide. Antimalarial medications, such as chloroquine, have demonstrated effectiveness in resolving mucocutaneous sarcoidosis that was resistant to steroids. In 10% to 20% of those affected by sarcoidosis, resolution does not occur even with treatment. CNS and chronic extrathoracic involvement are associated with a poor response to therapy. Approximately 4% to 10% of patients die of pulmonary, cardiac, or CNS complications.

OROFACIAL GRANULOMATOSIS

Since Wiesenfeld introduced it 1985, orofacial granulomatosis has become a well-accepted and unifying term encompassing a variety of clinical presentations that, on biopsy, reveal the presence of nonspecific granulomatous inflammation. The conditions previously designated as Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and cheilitis granulomatosa of Miescher are subsets of orofacial granulomatosis, and neither represents a specific disease.

The disorder is somewhat analogous to aphthous stomatitis, in that the cause is idiopathic but appears to represent an abnormal immune reaction. Sometimes oral lesions are seen that are identical to idiopathic orofacial granulomatosis but represent a secondary reaction to one or more of a variety of factors. Table 9-2 delineates systemic diseases that may mimic orofacial granulomatosis, and Table 9-3 lists possible local causes. Although many researchers have presented evidence that the immune response appears secondary to a chronic antigenic stimulus, the pathosis most likely has numerous triggers, resulting in various theories that are correct only in subsets of patients.

Table 9-2

Systemic Evaluation of Patients with Orofacial Granulomatosis

| Systemic Cause | Preliminary Screening Procedure |

| Chronic granulomatous disease | Neutrophil nitroblue tetrazolium reduction test (perform if medical history of chronic infections is noted) |

| Crohn’s disease | Hematologic evaluation for evidence of gastrointestinal malabsorption (e.g., low albumin, calcium, folate, iron, and red blood cell count; elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate) or leukocyte scintigraphy using 99mTc-HMPAO (hexamethylpropylene amine oxime); if initial screen is positive, then recommend esophagogastroduodenoscopy, ileocolonoscopy, and small-bowel radiographs |

| Sarcoidosis | Serum angiotensin–converting enzyme and chest radiograph (hilar lymphadenopathy) |

| Tuberculosis | Skin test and chest radiograph (negative acid-fast bacteria [AFB] stain on biopsy specimen does not rule out mycobacterial infection) |

Table 9-3

Interventions to Rule Out Local Causes for Orofacial Granulomatosis

| Local Cause | Intervention |

| Chronic oral infection | Eliminate all oral foci of infection. |

| Foreign material | The foreign debris noted in iatrogenic gingivitis is often subtle and difficult to associate definitively with the diffuse inflammatory process. If lesions are nonmigrating and isolated to gingiva, then response to local excision of a single focus should be evaluated. |

| Allergy | Cosmetics, foods, food additives, flavorings, oral hygiene products (e.g., toothpaste, mouth rinses), and dental restorative metals have been implicated. Patch testing (i.e., contact dermatitis standard series with oral battery) or elimination diet may discover the offending antigen. |

The majority of patients are adults; however, the process may occur at any age. When noted in children and adults younger than 30 years old, some investiga tors have found an increased association with an asymptomatic gastrointestinal inflammatory process that is not consistent with Crohn’s disease and possibly may be associated with a dietary trigger. A positive response has been seen in patients maintaining a diet free of two common food allergens, cinnamon and benzoate. In another cohort, allergy testing and dietary restriction also proved beneficial.

Because clinical and histopathologic features of orofacial granulomatosis can be produced by a variety of underlying causes, this diagnosis is the beginning, not the end, of the patient’s evaluation. After initial diagnosis, the patient should be evaluated for several systemic diseases and local processes (see Tables 9-2 and 9-3) that may be responsible for similar oral lesions. If features diagnostic of one of these more specific disorders are discovered, then the final diagnosis is altered appropriately.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The clinical presentation of orofacial granulomatosis is highly variable. By far, the most frequent site of involvement is the lips. The labial tissues demonstrate a nontender, persistent swelling that may involve one or both lips (Fig. 9-19). On rare occasions, superficial amber vesicles, resembling lymphangiomas, are found. When these signs are combined with facial paralysis and a fissured tongue, the clinical presentation is called Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (Figs. 9-20 and 9-21). Involvement of the lips alone is called cheilitis granulomatosa (of Miescher). Some consider cheilitis granulomatosa an oligosymptomatic form of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, but it appears best to include all of these under the term orofacial granulomatosis. In addition to labial edema, swelling of other parts of the face may be seen, and cervical lymphadenopathy rarely has been noted.

Fig. 9-19 Orofacial granulomatosis (cheilitis granulomatosa). Nontender, persistent enlargement of the upper lip. (From: Allen CM, Camisa C: Diseases of the mouth and lips. In Sams WM, Lynch P, editors: Principles of dermatology, New York, 1990, Churchill Livingstone.)

Fig. 9-20 Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Persistent enlargement of the lower lip. (Courtesy of Dr. Richard Ziegler.)

Fig. 9-21 Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Same patient as depicted in Fig. 9-20. Note numerous furrows on the dorsal surface of the tongue. (Courtesy of Dr. Richard Ziegler.)

Intraoral sites also can be affected, and the predominant lesions are edema, ulcers, and papules. The tongue may develop fissures, edema, paresthesia, erosions, or taste alteration. The gingiva can develop swelling, erythema, pain, or erosions. The buccal mucosa often exhibits a cobblestone appearance of edematous mucosa or focal areas of submucosal enlargement. Linear hyperplastic folds may occur in the mucobuccal fold, with linear ulcerations appear in the base of these folds (Fig. 9-22). The palate may have papules or large areas of hyperplastic tissue. Hyposalivation rarely is reported.

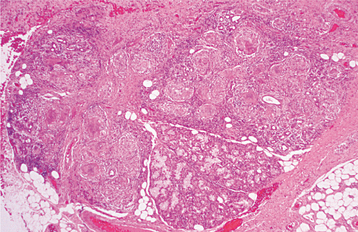

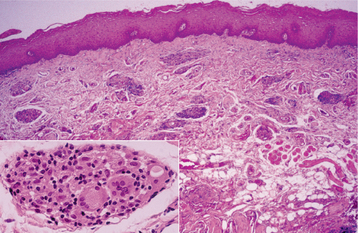

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: In classic cases of cheilitis granulomatosa, edema is present in the superficial lamina propria with dilation of lymphatic vessels and scattered lymphocytes seen diffusely and in clusters. Fibrosis may be present in long-term lesions. Scattered aggregates of noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, consisting of lymphocytes and epithelioid histiocytes, are present, with or without multinucleated giant cells. Typically, the granulomas appear to cluster around scattered vessels and are not as well formed or discrete as those seen in sarcoidosis (Fig. 9-23).

Fig. 9-23 Orofacial granulomatosis. Clusters of granulomatous inflammation around scattered vessels. The inset illustrates the histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells within the granulomas.

Special stains for fungal organisms and acid-fast bacteria are negative. No dissolvable, pigmented, or polarizable foreign material should be present. When the lesions are confined to the gingiva, a thorough search should be made, because many cases of granulomatous gingivitis are due to subtle collections of foreign material (see page 160).

DIAGNOSIS: The initial diagnosis of orofacial granulomatosis is made on histopathologic demonstration of granulomatous inflammation that is associated with negative special stains for organisms and no foreign material. Based on the clinical and historical findings, one or more conditions may have to be considered in the differential diagnosis. It should be stressed that no one cause for the granulomas will be found when large groups of patients with orofacial granulomatosis are studied. (See Tables 9-2 and 9-3 for a list of conditions and suggested procedures that may be appropriate to arrive at a more definitive diagnosis.)

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The first goal of management should be discovery of the initiating cause, although this may be difficult because the trigger often is elusive. In children and young adults, the search for a dietary allergen or an association with underlying gastrointestinal disease should be considered. Local measures to resolve the clinical manifestations can be attempted but, as would be expected, recurrences are common. The individual lesions have been treated with a variety of interventions, with variable results. Topical or intralesional corticosteroids, radiotherapy, salazosulfapyridine (sulfasalazine), hydroxychloroquine sulfate, azathioprine, cyclosporine A, methotrexate, danazol, dapsone, TNF-α antagonists (infliximab, thalidomide), clofazimine, metronidazole, and numerous other antibiotics have been tried. Currently, most investigators administer intralesional delayed-release high-concentrate triamcinolone to control the progression of this disease (Figs. 9-24 and 9-25). Of the alternatives, clofazimine (antileprosy agent with antigranulomatous properties) is mentioned most frequently as the second choice after corticosteroids. Because of the natural variability of the disease’s progression and the occurrence of spontaneous remissions, therapies are difficult to assess. In the absence of a response to other treatments, surgical recontouring has been used by some but carries a considerable risk of recurrence and rarely appears to be warranted. After excision, some clinicians recommend intralesional steroids to slow recurrences.

Fig. 9-24 Orofacial granulomatosis. A, Diffuse enlargement of the upper lip. B, Same patient after intralesional triamcinolone injections.

Fig. 9-25 Orofacial granulomatosis. Same patient depicted in Fig. 9-24. A, Clinical appearance before local therapy. B, Significant resolution after intralesional corticosteroid therapy.

The prognosis is highly variable. No therapy has proved to be the “silver bullet” in resolving the individual lesions. In some cases, lesions resolve spontaneously, with or without therapy; in others, they continue to progress in spite of a myriad of therapeutic attempts to stop the progression. The “lucky” subset of patients includes those who have found an initiating causation and have resolved their problems by the exclusion of the offending agent.

WEGENER’S GRANULOMATOSIS

Wegener’s granulomatosis is a well-recognized, although uncommon, disease process of unknown cause. The initial description of the syndrome by Wegener included necrotizing granulomatous lesions of the respiratory tract, necrotizing glomerulonephritis, and systemic vasculitis of small arteries and veins. Hypotheses about the cause of the disease include an abnormal immune reaction secondary to a nonspecific infection or an aberrant hypersensitivity response to an inhaled antigen. A possible hereditary predisposition has been mentioned in some cases.

Before the current treatment modalities were initiated, the disorder was uniformly fatal. The disease begins as a localized process, which may become more widely disseminated if left untreated. Most patients respond favorably to treatment; consequently, early diagnosis and appropriate therapy are critical.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Wegener’s granulomatosis demonstrates a wide age range from childhood to old age, with a mean of approximately 40 years and no sex predilection. The disease can involve almost every organ system in the body. With classic Wegener’s granulomatosis, patients initially show involvement of the upper and lower respiratory tract; if the condition remains untreated, then renal involvement often rapidly develops (generalized Wegener’s granulomatosis).

Limited Wegener’s granulomatosis is diagnosed when there is involvement of the respiratory system without rapid development of renal lesions. One subset of patients exhibits lesions primarily of the skin and mucosa, a condition termed superficial Wegener’s granulomatosis. In this form of the disease, systemic involvement develops slowly. These three different clinical patterns highlight the variability of the clinical aggressiveness that can occur in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Purulent nasal drainage, chronic sinus pain, nasal ulceration, congestion, and fever are frequent findings from upper respiratory tract involvement. Persistent otitis media, sore throat, and epistaxis also are reported. With progression, destruction of the nasal septum can result in a saddle-nose deformity. Patients with lower respiratory tract involvement may be asymptomatic, or they may have dry cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, or chest pain. Renal involvement usually occurs late in the disease process and is the most frequent cause of death. The glomerulonephritis results in proteinuria and red blood cell casts. Occasionally, the eyes, ears, and skin also are involved.

Oral lesions are seen in the minority of those affected; occasionally, the oral changes may be the only clinically evident finding. The most characteristic oral manifestation is strawberry gingivitis. This distinctive but uncommon pattern of gingival alteration appears to be an early manifestation of Wegener’s granulomatosis and has been documented before renal involvement in most cases. The affected gingiva demonstrates a florid and granular hyperplasia. The surface forms numerous short bulbous projections, which are hemorrhagic and friable; this red, bumpy surface is responsible for the strawberry-like appearance (Fig. 9-26). The buccal surfaces are affected more frequently, and the alterations are classically confined to the attached gingiva. The process appears to begin in the interdental region and demonstrates lateral spread to adjacent areas. At the time of diagnosis, the involvement may be localized or generalized to multiple quadrants. Destruction of underlying bone with the development of tooth mobility has been reported.

Fig. 9-26 Wegener’s granulomatosis. Hemorrhagic and friable gingiva (strawberry gingivitis). (Courtesy of Dr. Sam McKenna.)

Oral ulceration also may be a manifestation of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Unlike the strawberry gingiva, the ulcerations do not form a pattern that is unique. These lesions are clinically nonspecific and may occur on any mucosal surface (Fig. 9-27). In contrast to the gingival changes, the oral ulcerations are diagnosed at a later stage of the disease, with more than 60% of the affected patients demonstrating renal involvement. Other less common orofacial manifestations include facial paralysis, labial mucosal nodules, sinusitis-related toothache, arthralgia of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), jaw claudication, palatal ulceration from nasal extension, oral-antral fistulae, and poorly healing extraction sites.

Fig. 9-27 Wegener’s granulomatosis. Deep, irregular ulceration of the hard palate on the left side. (From Allen CM, Camisa C, Salewski C et al: Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of three cases with oral lesions, J Oral Maxillofac Surg 49:294-298, 1991.)

Enlargement of one or more major salivary glands from primary involvement of the granulomatous process also has been reported. The glandular involvement also appears early in the course of the disease and may lead to early diagnosis and treatment.

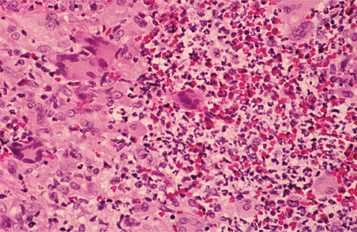

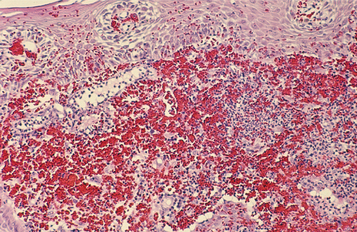

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Wegener’s granulomatosis appears as a pattern of mixed inflammation centered around blood vessels. Involved vessels demonstrate transmural inflammation, often with areas of heavy neutrophilic infiltration, necrosis, and nuclear dust (leukocytoclastic vasculitis). The connective tissue adjacent to the vessel has an inflammatory cellular infiltrate, which contains a variable mixture of histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 9-28). Special stains for organisms are negative, and no foreign material can be found. In oral biopsy specimens, the oral epithelium may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and subepithelial abscesses. Because of the paucity of large vessels in many oral mucosal biopsies, vasculitis may be difficult to demonstrate, and the histopathologic presentation may be one of ill-defined collections of epithelioid histiocytes intermixed with eosinophils, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. In addition, the lesions of strawberry gingivitis typically demonstrate prominent vascularity with extensive red blood cell extravasation (Fig. 9-29).

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis is made from the combination of the clinical presentation and the microscopic finding of necrotizing and granulomatous vasculitis. Radiographic evaluation of the chest and sinuses is recommended to document possible involvement of these areas. The serum creatinine and urinalysis results are used to rule out significant renal alterations.

A laboratory marker for Wegener’s granulomatosis has been identified. Indirect immunofluorescence for serum antibodies directed against cytoplasmic components of neutrophils has been used to support a diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis. There are two reaction patterns of these antineutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA):

Cytoplasmic localization (c-ANCA) is the most useful in the diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Positive immunofluorescence for c-ANCA should be confirmed with a specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test for antibodies against proteinase 3 (PR3), the major antigen for c-ANCA that resides in the azurophilic granules of neutrophils. These combined tests are associated with a sensitivity of 73% and a diagnostic specificity of 99% for Wegener’s granulomatosis. False positives are uncommon and may be associated with a variety of other diseases. In contrast, p-ANCAs are detected in several vasculitides that typically do not present in the oral cavity. With ELISA testing, antibodies directed against myeloperoxidase, a lysosomal enzyme in neutrophils, will be identified.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The mean survival of untreated patients with disseminated classic Wegener’s granulomatosis is 5 months; 80% of the patients are dead at 1 year and 90% within 2 years. The prognosis is better for the limited and superficial forms of the disease, although a proportion of patients with localized disease eventually will develop classic Wegener’s granulomatosis.

The first line of therapy is oral prednisone and cyclophosphamide. On remission, the prednisone is gradually discontinued, with continuation of the cyclophosphamide for at least 1 year. Relapse is not uncommon, especially during tapering of the therapy. Although high response rates are noted, serious side effects related to the therapy are not rare. Tri-methoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been used successfully in localized cases and when the immunosuppressive regimen has failed. Low-dose methotrexate and corticosteroids also have been used in patients whose disease is not immediately life threatening or has not responded appropriately to cyclophosphamide. Additional treatment options under study for generalized Wegener’s granulomatosis include cyclosporine, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, plasmapheresis, antilymphocytic monoclonal antibodies, and intravenous pooled immunoglobulin.

Treatment has a profound effect on the progression of the disease. With appropriate therapy, prolonged remission is noted in up to 75% of affected patients; a cure often is attainable when the disease is diagnosed and appropriately treated while the involvement is localized. Because of a relapse rate up to 30%, maintenance therapy is necessary in many patients. The c-ANCA levels can be used to monitor the disease activity. Patients appear less likely to have relapses if their antineutrophilic antibodies disappear during treatment; in contrast, patients whose levels of antibodies persist are at greater risk for relapse.

ALLERGIC MUCOSAL REACTIONS TO SYSTEMIC DRUG ADMINISTRATION

The future of dentistry and medicine will involve a high volume of patients suffering from adverse drug reactions. By 2030, 20% of the population will be more than 65 years old. As the population ages and those affected with chronic diseases increase, patients taking multiple medications most likely will escalate. In the United States during the year 2000, more than 2.8 billion prescriptions were filled, enough to supply each inhabitant with 10 prescriptions annually. Although use of two medications is associated with a 6% risk of an adverse reaction, the frequency rises to 50% with five drugs and almost a 100% when eight or more medications are used simultaneously.

The list of offending medications and their resultant side effects appears almost endless. In a short and highly beneficial article, Matthews listed more than 150 frequently prescribed medications and related them to 46 oral and perioral side effects associated with their use. Despite such excellent articles, it may be helpful for health care practitioners to use one of the excellent drug reference programs available on compact disk or online to create an adverse reaction and drug interaction document for patients in their practice and to update these on a regular basis.

In addition to common drug-related problems such as xerostomia (see page 464), dysgeusia (see page 875), and gingival hyperplasia (see page 163), medications can induce a wide variety of mucosal ulcerations and erosions. An allergic reaction of the oral mucosa to the systemic administration of a medication is called stomatitis medicamentosa. Besides erythema multiforme (see page 776), several different patterns of oral mucosal disease can be seen:

• Intraoral fixed drug eruptions

• Lupus erythematosus–like eruptions

Anaphylactic stomatitis arises after the allergen enters the circulation and binds to IgE–mast cell complexes. Although systemic anaphylactic shock can result, localized alterations also occur. Fixed drug eruptions are inflammatory alterations of the mucosa or skin that recur at the same site after the administration of any allergen, often a medication.

The vast number of medications capable of producing anaphylactic stomatitis precludes their listing, but common culprits are antibiotics (especially penicillin) and sulfa drugs. Medications reported to be associated with fixed drug eruptions are listed in Box 9-2, lichenoid drug eruptions in Box 9-3, lupus erythematosus–like drug eruptions in Box 9-4, pemphigus-like drug reactions in Box 9-5, and nonspecific vesiculoerosive or aphthouslike eruptions in Box 9-6.

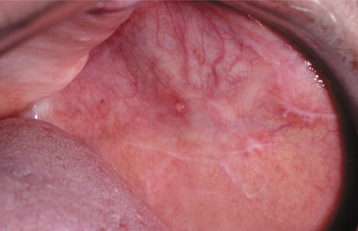

CLINICAL FEATURES: The patterns of mucosal alterations associated with the systemic administration of medications are varied, almost as much as the number of drugs that result in these changes. Anaphylactic stomatitis may occur alone or in conjunction with urticarial skin lesions or other signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis (e.g., hoarseness, respiratory distress, vomiting). The affected mucosa may exhibit multiple zones of erythema or numerous aphthouslike ulcerations. Mucosal fixed drug eruptions appear as localized areas of erythema and edema, which can develop into vesiculoerosive lesions and are located most frequently on the labial mucosa. Lichenoid, lupuslike, and pemphigus-like drug reactions resemble their namesakes clinically, histopathologically, and immunologically (Fig. 9-30). These latter chronic drug reactions may involve any mucosal surface, but the most common sites are the posterior buccal mucosa and the lateral borders of the tongue (Figs. 9-31 and 9-32). Bilateral and symmetrical lesions are fairly common.

Fig. 9-30 Allergic mucosal reaction to systemic drug administration. Mucosal lesions associated with use of oxybutynin chloride (anticholinergic therapy for urinary incontinence). Note lichen planus–like striae. In addition, multiple superficial mucoceles occurred on the soft palate, floor of the mouth, and bilaterally on the buccal mucosa.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Anaphylactic stomatitis typically reveals a nonspecific pattern of subacute mucositis that contains lymphocytes intermixed with eosinophils and neutrophils. Fixed drug eruptions also reveal a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate that consists of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils, often combined with spongiosis and exocytosis of the epithelium. Vacuolar change of the basal cell layer and individual necrotic epithelial cells are occasionally noted. The drug reactions that simulate lichen planus, lupus erythematosus, and pemphigus resemble their namesakes. The histopathologic and immunologic features of these chronic drug reactions cannot be used reliably to separate them from their associated primary immunologic disease.

Immunofluorescence has been used in an attempt to separate drug reactions from primary vesiculoerosive disease. In most instances, this technique has proven to be unsatisfactory. In spite of these findings, a unique pattern of reaction has been seen when indirect immunofluorescence for IgG has been performed in patients with lichenoid drug reactions. In many of these patients, a distinctive annular fluorescent pattern, termed string of pearls, has been noted along the cell membrane of the basal cell layer of stratified squamous epithelium. The detected circulating antibody has been termed basal cell cytoplasmic antibody. Although further study is desirable, this technique may prove to be a useful adjunct during evaluation of oral lichenoid lesions.

DIAGNOSIS: A detailed medical history must be obtained, and the patient should be questioned closely concerning the use of both prescription and over-the-counter medications. Once a potentially offending medication is discovered, a temporal relationship between the drug’s use and the mucosal alteration must be established. The association may be acute and obvious, or the onset of the oral lesions may be delayed. If more than one medication is suspected, then serial elimination of the medications can be performed in collaboration with the patient’s physician until the offending agent is discovered.

In chronic drug reactions, definitive diagnosis can be made if the mucosal alterations resolve after resolution of the medication and recur on reintroduction of the agent. Presumptive diagnosis is usually sufficient and justified when the mucosal alterations clear after cessation of the offending medication.

In possible lupuslike drug reactions, serum evaluation for generic antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and antibodies against double-stranded DNA and histones often can be beneficial. Lupuslike drug reactions typically are associated with circulating generic ANAs and antibodies against histones, whereas lupus erythematosus also reveals antibodies to double-stranded DNA (a finding not typically noted in drug reactions). This pattern does not hold true in reactions associated with the TNF-α antagonists, infliximab and etanercept, which simulate systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) very closely and are associated with antibodies to double-stranded DNA.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The responsible medication should be discontinued and, if necessary, replaced with another drug that provides a similar therapeutic result. Localized acute reactions can be resolved with topical corticosteroids. When systemic manifestations are present, anaphylactic stomatitis often warrants systemic administration of adrenaline (epinephrine), corticosteroids, or antihistamines. Chronic oral lesions often resolve on cessation of the offending drug, but topical corticosteroids may sometimes be required for complete resolution.

If discontinuation of the medication is contraindicated, palliative care can be provided; however, corticosteroids often are ineffective as long as the offending medication is continued.

ALLERGIC CONTACT STOMATITIS (STOMATITIS VENENATA)

The list of agents reported to cause allergic contact stomatitis reactions in the oral cavity is extremely diverse. Numerous foods, food additives, chewing gums, candies, dentifrices, mouthwashes, glove and rubber dam materials, topical anesthetics, restorative metals, acrylic denture materials, dental impression materials, and denture adhesive preparations have been mentioned. Two types of allergens, cinnamon and dental restorative materials, demonstrate clinical and histopathologic patterns that are sufficiently unique to justify separate descriptions.

Although the oral cavity is exposed to a wide variety of antigens, the frequency of a true allergic reaction to any one antigen from this contact appears to be rare. This was verified in a prospective study of 13,325 dental patients, in which only seven acute and 15 chronic cases of adverse effects were attributed to dental materials. The oral mucosa is much less sensitive than the surface of the skin; this is most likely because of the following:

• The period of contact is often brief.

• The saliva dilutes, digests, and removes many antigens.

• The limited keratinization of oral mucosa makes hapten binding more difficult, and the high vascularity tends to remove any antigen quickly.

• The allergen may not be recognized (because of the lower density of Langerhans cells and T lymphocytes).

If the skin has been sensitized originally, the mucosa may or may not demonstrate future clinical sensitization. In contrast, if the mucosa is sensitized initially, then the skin usually demonstrates similar changes with future exposure. Long-term oral exposure may induce tolerance and reduce the prevalence of cutaneous sensitivity in some instances. For example, exposure to nickel-containing orthodontic hardware has been associated with a reduced prevalence of future cutaneous sensitivity to nickel jewelry.

In addition to oral lesions, allergic contact reactions may produce exfoliative cheilitis (see page 304) or perioral dermatitis (see next section). As mentioned in Chapter 8, most cases of chronic cheilitis represent local irritation, usually from chronic lip licking. In spite of this, investigation has revealed that approximately 25% of affected cases are allergic contact cheilitis from a variety of antigens that include medications, lipsticks, sunscreens, toothpaste, dental floss, nail polishes, and cosmetics.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Allergic contact stomatitis can be acute or chronic. Of those cases diagnosed, there is a distinct female predominance in both forms. After eliminating focal trauma, localized signs and symptoms suggest mucositis from an isolated allergen (e.g., dental metal); in contrast, widespread mouth pain suggests an association with a more diffuse trigger such as food, drink, flavorings, or oral hygiene materials.

In patients with acute contact stomatitis, burning is the most frequent symptom. The appearance of the affected mucosa is variable, from a mild and barely visible redness to a brilliantly erythematous lesion with or without edema. Vesicles are rarely seen and, when present, rapidly rupture to form areas of erosion (Fig. 9-33). Superficial ulcerations that resemble aphthae occasionally arise. Itching, stinging, tingling, and edema may be noted.

Fig. 9-33 Allergic contact stomatitis to aluminum chloride. Mucosal erythema and vesicles of the lower labial mucosa caused by use of aluminum chloride on gingival retraction cord.

In chronic cases the affected mucosa is typically in contact with the causative agent and may be erythematous or white and hyperkeratotic. Periodically, erosions may develop within the affected zones. Some allergens, especially toothpastes, can cause widespread erythema, with desquamation of the superficial layers of the epithelium (Fig. 9-34). Allergic contact cheilitis demonstrates clinical features identical to those cases created through chronic irritation, and it most frequently appears as chronic dryness, scaling, fissuring, or cracking of the vermilion border of the lip. Rarely, symptoms identical to orolingual paresthesia can be present without any clinically evident signs. One distinctive pattern, plasma cell gingivitis, is discussed elsewhere (see page 159).

DIAGNOSIS: Usually, the diagnosis of acute contact stomatitis is straightforward because of the temporal relationship between the use of the agent and the resultant eruption. If an acute oral or circumoral reaction is noted within 30 minutes of a dental visit, then allergy to all used dental materials, local anesthetics, and gloves should be investigated.

The diagnosis of chronic contact stomatitis is much more difficult. Most investigators require good oral health, elimination of all other possible causes, and visible oral signs, together with a positive history of allergy and a positive skin test result to the suspected allergen. If allergic contact stomatitis is strongly suspected but skin test results are negative, then direct testing of the oral mucosa can be attempted. The antigen can be placed on the mucosa in a mixture with Orabase or in a rubber cup that is fixed to the mucosa.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: In mild cases of acute contact stomatitis, removal of the suspected allergen is all that is required. In more severe cases, antihistamine therapy, which is combined with topical anesthetics (e.g., dyclonine HCl), is usually beneficial. Chronic reactions respond to removal of the antigenic source and application of a topical corticosteroid, such as fluocinonide gel or dexamethasone elixir.

When attempting to discover the source of a diffuse allergic mucositis, use of plain baking soda or toothpaste that is free of flavoring or preservatives is recommended. The patient also should be instructed to avoid mouthwash, gum, mints, chocolate, cinnamon-containing products, carbonated drinks, and excessively salty, spicy, or acidic foods. If an association cannot be found, then cutaneous patch testing may provide helpful information.

PERIORAL DERMATITIS

Perioral dermatitis refers to a unique inflammatory skin disease that involves the circumoral area. Although the exact mechanism is uncertain, many investigators believe the process arises from an idiosyncratic response to a variety of exogenous substances; once this process is initiated, potent topical corticosteroid use worsens the condition. Although the vast majority of affected patients report topical corticosteroid use, only a minority initiate this therapy before initial development of the dermatitis. Exogenous substances reported to initiate the rash include tartar-control toothpaste, bubble gum, moisturizers, night creams, and other cosmetic products (e.g., foundation). Some of these substances may initially induce an irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, whereas others are thought to produce inappropriate occlusion of the skin surface with subsequent proliferation of skin flora.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Perioral dermatitis appears with persistent erythematous papules and papulopustules that involve the skin surrounding the vermilion border of the upper and lower lips (Fig. 9-35). Classically, there is a zone of spared skin immediately adjacent to the vermilion border. Pruritus is variable. In adults, more than 90% of affected patients are women, lending further support to the association with cosmetic use. The prevalence of perioral dermatitis appears to be increasing and may be related to the greater percentage of cosmetic-wearing women in the workforce. In children, the female predominance is dramatically reduced or is nonexistent in some studies. In addition, an identical pattern of periorbital and perinasal dermatitis often is present in younger patients with classic perioral lesions.

Fig. 9-35 Perioral dermatitis. Multiple erythematous papules of the skin surrounding the vermilion border of the lips. (Courtesy of Dr. Charles Camisa.)

Some investigators have reported perioral dermatitis that has arisen solely from use of tartar-control toothpaste (irritant contact dermatitis from pyrophosphate compounds), but close inspection reveals a different clinical presentation. In these reports the dermatitis appears as a zone of erythema without papules or pustules; it involves only the skin immediately adjacent to the vermilion border, without the classic sparing of this area. This pathosis is classified most appropriately as circumoral dermatitis and does not fulfill the classic criteria for perioral dermatitis.

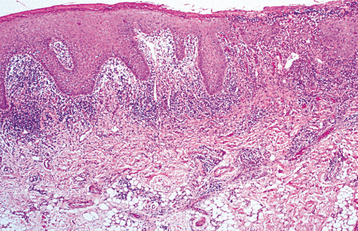

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsy of perioral dermatitis demonstrates a variable pattern. In many cases there is a chronic lymphohistiocytic dermatitis that often exhibits spongiosis of the hair follicles. In other patients a rosacea-like pattern is noted in which there is perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. On occasion, this histopathologic pattern has been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The first step in management is discontinuation of potent topical corticosteroid use, if present. Often, this is followed by a period of exacerbation, which can be minimized by substitution of a less potent corticosteroid before total cessation. Oral tetracycline has been shown to be effective by many investigators, with erythromycin substituted during childhood and pregnancy. Topical metronidazole or erythromycin also has been used successfully in several studies. The pathosis typically demonstrates significant improvement within several weeks and total resolution in a few months. Recurrence is uncommon.

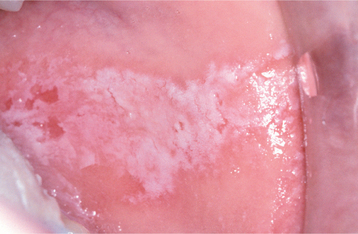

CONTACT STOMATITIS FROM ARTIFICIAL CINNAMON FLAVORING

Mucosal abnormalities secondary to the use of artificially flavored cinnamon products are fairly common, but the range of changes was not widely recognized until the late 1980s. Cinnamon oil is used as a flavoring agent in confectionery, ice cream, soft drinks, alcoholic beverages, processed meats, gum, candy, toothpaste, breath fresheners, mouthwashes, and even dental floss. Concentrations of the flavoring are up to 100 times that in the natural spice. The reactions are documented most commonly in those products associated with prolonged or frequent contact, such as candy, chewing gum, and toothpaste. The anticalculus components of tartar-control toothpastes have a strong bitter flavor and require a significant concentration of flavoring agents including cinnamon to hide the taste, resulting in a greater chance these formulations will cause oral mucosal lesions. Although much less common, reactions to cinnamon in its natural spice form have been documented.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The clinical presentations of contact stomatitis vary somewhat, according to the medium of delivery. Toothpaste results in a more diffuse pattern; the signs associated with chewing gum and candy are more localized. Pain and burning are common symptoms in all cases.

The gingiva is the most frequent site affected by toothpaste, often resembling plasma cell gingivitis (see page 159); enlargement, edema, and erythema are common. Sloughing of the superficial oral epithelium without creation of an erosion is seen commonly. Erythematous mucositis, occasionally combined with erosion, has been reported on the buccal mucosa and tongue. Exfoliative cheilitis and circumoral dermatitis also may occur.

Reactions from chewing gum and candy are more localized and typically do not affect the lip vermilion or perioral skin. Most of the lesions appear on the buccal mucosa and lateral borders of the tongue. Buccal mucosal lesions often are oblong patches that are aligned along the occlusal plane (Fig. 9-36). Individual lesions have an erythematous base but often are predominantly white as a result of hyperkeratosis of the surface epithelium. Ulceration within the lesions may occur. Hyperkeratotic examples often exhibit a ragged surface and occasionally may resemble the pattern seen in morsicatio (see page 286). Lingual involvement may become extensive and spread to the dorsal surface (Fig. 9-37). Significant thickening of the surface epithelium can occur and may raise clinical concern for oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) (see page 268) or carcinoma (Fig. 9-38).

Fig. 9-36 Contact stomatitis from cinnamon flavoring. Oblong area of sensitive erythema with overlying shaggy hyperkeratosis.