Chapter 16 Access to medicines and prescribing – introduction

Introduction

The legal constraints introduced in the United Kingdom to limit prescribing of certain medicines for humans to doctors and dentists remained largely unaltered until 1994 when suitably trained community nurses were added to the list of professions able to prescribe a limited range of medicines and appliances listed in the Nurse Prescribers’ Formulary (NPF). Prior to the introduction of community nurse prescribing it was recognized that many district nurses were prescribing in all but name as they were instructing GPs what to prescribe and that much time was wasted waiting for GPs to write the prescription. The review of prescribing, supply and administration of medicines chaired by June Crown in 1999 recommended that there should be two types of prescriber: the independent prescriber and the dependent prescriber, although the term dependent prescriber has now been replaced by the term supplementary prescriber (Department of Health 1999). The independent prescriber is responsible for diagnosis and the supplementary prescriber is responsible for the ongoing care of the patient in line with an agreed clinical management plan (CMP). At the start of the 21st century there were significant changes to non-medical prescribing with the introduction of different classifications of nurse prescriber and the extension of prescribing to suitably trained pharmacists and other healthcare professionals (Department of Health 2006).

Over the years there have been many reports from the Department of Health outlining the benefits of non-medical prescribing for patients, doctors and non-medical prescribers themselves (Department of Health 1999, 2006). Many of these benefits stem from having the healthcare professional responsible for the care of a patient’s condition also writing the prescription (Box 16.1).

Independent prescribing

Independent prescribers (IP) are responsible for the diagnosis of the patient and can initiate prescriptions for patients without referring to other healthcare professionals. They have responsibility for monitoring and reviewing the patient’s progress. The first group of independent non-medical prescribers were the community practitioner nurse prescribers. This was first introduced in 1994 in eight pilot sites. The scheme was extended nationwide in 1999. It is open to nurses holding a district nurse (DN) or health visitor (HV) qualification working in the community, and this includes a small number of practice nurses with a DN or HV qualification. Training consisted of 2 days of taught sessions in addition to an open learning package (approximately 15 hours of study material) followed by a written examination. This has now been incorporated into the DN and HV course. These prescribers prescribe from the NPF that can be found in the British National Formulary (see Box 16.2 for examples of items in the NPF).

Box 16.2 Examples of products in the Nurse Prescribers’ Formulary (NPF) that can be prescribed by community practitioner nurse prescribers

| Types of product that can be prescribed | Examples |

| Wound management products | Granuflex® |

| Catheter care products | Bard, Simpla, etc. |

| Analgesics | Paracetamol |

| Laxatives | Lactulose, phosphate enema |

| Skin preparations | Aqueous cream |

In 2002 a new class of nurse prescriber was created; these were originally called extended formulary nurse prescribers. This opened prescribing to any registered nurse and it originally covered four main areas:

Nurses that chose this route to becoming a prescriber were required to complete a training course which consisted of 26 taught days and 12 days learning in practice, which included prescribing under the supervision of a medical prescriber (Department of Health 2006). It should be noted that the taught element of the training programme did not include therapeutics, i.e. it did not cover what to prescribe for a particular condition; it did cover how to prescribe in a way that complied with legal requirements. In 2006 many of the previous restrictions on extended formulary nurse prescribers were removed and their name was changed to independent nurse prescribers. The independent nurse prescribers are able to prescribe any licensed medicine and some controlled drugs. Therefore there is no need for the extended nurse prescriber’s formulary, which is no longer in existence. The changes in 2006 also paved the way for independent pharmacist prescribers. Independent pharmacist prescribers can prescribe any licensed medicine except controlled drugs.

Supplementary prescribing

Supplementary prescribing is viewed by the Department of Health as a voluntary partnership between the independent and the supplementary prescriber that has the agreement of the patient (Department of Health 2005). Therefore the patient must be informed regarding the underlying principles of the prescribing partnership by the independent prescriber and give their consent to the transfer of care to a supplementary prescriber (SP). The patient does not have to give written consent, but once consent has been given it should be noted in the patient’s medical notes.

Providing the patient agrees, there is very little restriction as to what can be prescribed. The drugs that can be prescribed by supplementary prescribers include all ‘prescription only medicines’, ‘pharmacy’ medicines and ‘general sales list’ medicines, although the NHS prescribers cannot prescribe items listed in the Black List (Part XVIIIA of the Drug Tariff) at NHS expense. Controlled drugs and unlicensed medicines were added to the list of drugs that can be prescribed by supplementary prescribers in May 2005.

An independent prescriber, who must be a doctor or a dentist, makes the diagnosis. If the independent prescriber thinks that the patient can be safely managed by a supplementary prescriber then both the independent prescriber and supplementary prescriber agree a clinical management plan for the patient. However, the independent prescriber does not discard all their responsibility and must still review the patient at suitable intervals, which should rarely exceed a year (Department of Health 2005).

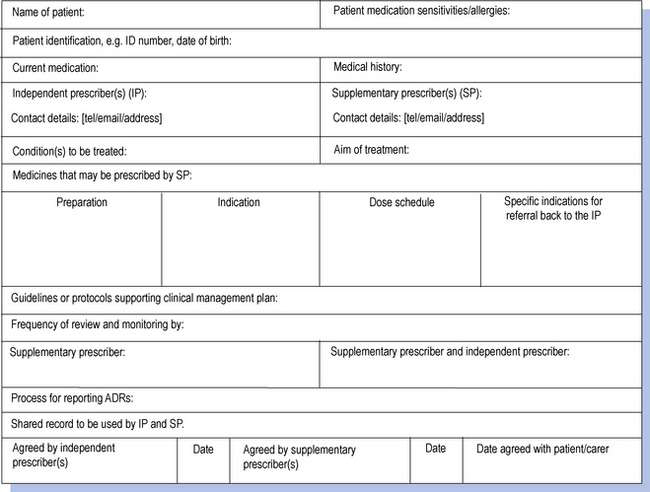

The clinical management plan is central to supplementary prescribing in that it forms the agreement between the independent and supplementary prescribers that sets out what the supplementary prescriber is able to prescribe (Fig. 16.1). Each clinical management plan must be drawn up for a specific named patient. The nature of the clinical management plan can vary in terms of its detail and scope. At one end of the spectrum it could be very specific, allowing only relatively minor modifications to be made to the original prescription under specified criteria such as increasing the dosage of an antihypertensive drug in order to reduce blood pressure to a specified level. At the other end of the spectrum it could be very open, allowing the supplementary prescriber to prescribe a wide range of drugs in accordance with a clinical guideline such as the British Thoracic Society’s guidelines for the management of asthma. The nature of the clinical management plan will depend upon the confidence and competence of the supplementary prescriber in each therapeutic area and also the willingness of the independent prescriber to delegate the responsibility. The plan also sets out the circumstances that would require referral back to the independent prescriber.

The patients most likely to benefit from supplementary prescribing are those with chronic conditions requiring ongoing care, such as diabetes mellitus, asthma or hypertension. In addition, those with uncomplicated conditions rather than those patients with multiple problems are likely to be the most suitable candidates for supplementary prescribing. In practice the supplementary prescriber is likely to continue prescribing the items initiated by the independent prescriber until there is a change in the patient’s condition, provided such items have been included in the clinical management plan. A change in the patient’s condition could involve a deterioration of a chronic progressive condition. An example of managing the deterioration is stepping up therapy by prescribing an additional item such as a steroid inhaler (preventer) to an asthmatic patient who is poorly controlled on a salbutamol inhaler (reliever) alone (see Ch. 37).

As supplementary prescribers do not diagnose conditions, one might assume that they would be unable to prescribe for patients presenting with acute conditions. However, they can prescribe items in response to changes in the patient’s condition, provided such items have been included in the clinical management plan. A change in the patient’s condition could involve an acute exacerbation of a chronic condition. An example is prescribing an antibiotic for a chest infection for a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Patient group directions

An alternative way of getting medicines to patients without writing a prescription involves the use of patient group directions (PGD). These allow pharmacists, or other healthcare professionals, to supply named products to patients that meet the inclusion criteria specified in the PGD (Department of Health 1998). The legal definition of a PGD is: ‘A written instruction for the sale, supply and/or administration of named medicines in an identified clinical situation. It applies to groups of patients who may not be individually identified before presenting for treatment.’

Under a PGD, pre-packed licensed medicines can be supplied to patients who meet the appropriate inclusion criteria and do not meet any of the specified exclusion criteria. The PGD must state the qualifications and training required of the staff administering the PGD, and it must name the medicine(s) that can be supplied. It must also list any advice that should be given to the patient, describe the referral procedure and state the action that should be taken in the case of a patient suffering an adverse drug reaction (ADR). The PGD must be reviewed and approved by a team containing a doctor and a pharmacist.

The Department of Health has made it clear that the preferred route of getting medicines to patients is via the issuing of a prescription to a named patient by a trained and qualified prescriber and that PGDs should only ever be used where they offer clear advantages to patient care without compromising patient safety (Department of Health 1998). Situations that could be suitable for PGDs are those that involve one off or relatively short courses of standard treatment (i.e. the PGD operator does not have to select the drug, dose or formulation). An example of a PGD is the supply of emergency hormonal contraception through community pharmacies.

Over the counter medicines

Pharmacists have a long tradition of selling medicines over the counter to treat minor ailments. In some situations pharmacists might have a choice regarding the method of supply of a medicine to treat a patient. This could be via an over the counter sale, prescribing a medicine as part of a minor ailment scheme (see next section) or supply through a PGD. In some of these situations the exact same product could be supplied and the only differences between the different methods might be who pays for the treatment and whether records have to be made. The pharmacist’s duty of care to the patient does not vary between the different methods of supply and pharmacists should not treat an over the counter purchase of medicine any differently than prescribing a medicine.

When recommending products to patients for over the counter purchase, the pharmacist is acting as an independent prescriber, although they can only recommend general sales list (GSL) medicines or pharmacy only (P) medicines. As an independent prescriber, the pharmacist must go through all the steps of the prescribing process (see Ch. 17). The steps include questioning the patient or their carer to ascertain signs, symptoms and relevant medical history including prescribed and purchased medicines that the patient is currently taking, to arrive at a working diagnosis. The patient should be involved in the decision-making process to achieve concordance, and appropriate advice given to allow the patient or their carer to monitor the progress of their treatment and to know when to seek further help or advice.

Minor ailment schemes

Minor ailments have been described as ‘conditions that require little or no medical intervention’ (see Box 16.3 for a list of minor ailments; Royal Pharmaceutical Society 2006). It has been recognized that treatments for minor ailments are responsible for considerable amounts of GP time and considerable amounts of NHS expenditure. Minor ailment schemes have been developed to allow patients to be seen by community pharmacists to ease the burden on GPs. There are many schemes in operation and each scheme is locally agreed by patients, practices, pharmacists and primary care trusts and therefore there is no universally agreed minor ailment scheme. However, all minor ailment schemes should have a formal written protocol that sets out how the scheme should operate.

Box 16.3 Minor ailments treated by pharmacists as part of minor ailment schemes in the UK

| Athlete’s foot |

| Bites and stings |

| Constipation |

| Contact dermatitis |

| Cough |

| Diarrhoea |

| Dyspepsia |

| Earache |

| Hay fever |

| Headache |

| Head lice |

| Mouth ulcers |

| Nasal symptoms |

| Sore throat |

| Teething |

| Temperature |

| Vaginal thrush |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) |

There are three main types of intervention that pharmacists can make when participating in a minor ailment scheme and schemes could involve one or more of these interventions. The first of these involves providing advice to the patient. The second involves the patient receiving a medicine and this could be via the pharmacist writing a prescription for a pharmacy only medicine or supplying a product via a patient group direction. When pharmacists prescribe medicines in a minor ailment scheme the medicine is usually from a locally agreed formulary. The third intervention is referral to a GP and many of the schemes include a fast track referral allowing patients who have been reviewed by a pharmacist to be seen more quickly by the GP should their condition warrant such speed. The arrangements for referral on to a minor ailment scheme also vary between different schemes with some schemes allowing self-referral by patients and others requiring referral from a healthcare professional or a practice receptionist.

The arrangements for payments for any product supplied via a minor ailment scheme vary between different schemes. In some schemes patients have to pay the full cost of the product but in others the costs are met by trusts for all patients and in some only for those patients exempt from the normal prescription levy.

Influences on prescribing

Prescribers must have an awareness of factors with potential to influence prescribing decision making and take steps to ensure that their decision making is not adversely affected by these influences. Researchers have been investigating medical prescribing decision making for many years and there is now an extensive amount of literature on the factors that can influence medical prescribing. By comparison there is much less written about non-medical prescribing, which means that we must consult the medical literature to review the factors likely to influence prescribing.

A number of patient factors have been reported to have an influence on medical prescribing decision making (Bradley 1992). The age of the patient has been reported to cause prescribers discomfort, with the very old and very young being responsible. In such cases prescribers should question whether they should prescribe for any group of patients where they lack experience. Patients who were well known to the prescriber were identified as a source of discomfort and these included frequent attenders at the practice and patients considered to be untrustworthy. Patients deemed untrustworthy by the prescriber, perhaps through the previous misuse of drugs, deserve the same consideration as other patients, although prescribers should be cautious regarding requests for items liable for misuse. The patient’s social class, ethnic background and educational status were also reported to cause discomfort for some prescribers. It is obviously not acceptable to allow these factors to influence prescribing. It has been reported that patients affected prescribing decision making through demand for prescription items, although other researchers have suggested that doctors may overestimate this pressure to prescribe (Stevenson et al 1999). Prescribers should never assume patients want a prescription. They should explore what the patient feels about their condition as many patients visit healthcare professionals to receive reassurance that they do not have a serious problem rather than to get medicines to treat symptoms.

The characteristics of a product were also reported to influence prescribing decision making (Bradley 1992). Specific groups of products, such as antibiotics, benzodiazepines, cardiovascular drugs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tranquillizers, antidepressants and sleeping tablets were reported to cause discomfort for prescribers. The important aspect for non-medical prescribers may not be the actual product that caused discomfort but rather the reasons for the discomfort. These included safety, their own expectations, appropriateness of treatment and uncertainty over diagnosis. Ensuring that prescribing decisions are based upon the best available evidence should help to minimize discomfort over the first three of these reasons. The last reason can be more difficult as there are situations, such as diagnosing mental health problems and diagnosing ailments in young children, where a suspected diagnosis is difficult to confirm or may not be confirmed until after a period of time, although the patient’s symptoms are such that they require immediate management. Living with uncertainty can be difficult but informing the patient or their carer regarding the uncertainty and what action you recommend should help minimize its impact. A product’s cost has been reported to have an impact on prescribing for some prescribers (Denig & Haaijer-Ruskamp 1995). The impact of cost on prescribing was related to the condition being treated such that the effects of cost on prescribing were greater for self-limiting conditions compared to conditions perceived to be serious.

The time available for a consultation with patients has been noted as a factor that can affect the volume of prescriptions written (Muller 1972). It has been suggested that having too little time with patients meant that it was easier to prescribe, rather than to explain why no prescription was required. This is obviously not an acceptable reason for prescribing. Prescribers must consider the time management of their consultations and determine strategies for eliciting patients’ views on drugs and the management of their symptoms, as well as strategies to end a consultation without issuing a prescription.

Many studies have concluded that representatives from the pharmaceutical industry were the most commonly used source of information by prescribers when they were prescribing new drugs for the first time (McGettigan et al 2000; Prosser et al 2003). Interestingly, several studies that compared the quality of prescribing with the source of information used by the prescriber reported that poorer quality prescribing was associated with a higher use of information originating from the pharmaceutical industry (Haayer 1982).

Several studies have noted the influence of colleagues on medical prescribing decision making. It has been reported that hospital consultants are a major influence on the prescribing of GPs but fellow GPs are much less of an influence (Jones et al 2001). Colleagues can be a valuable source of information on developments in health care and sharing experiences with fellow professionals can aid the development of strategies to manage patient consultations discussed earlier. Establishing professional links with other prescribers – not just pharmacist prescribers but GPs, hospital medical prescribers, nurses and other non-medical prescribers – is to be encouraged.

Clinical governance in prescribing

Clinical governance is about regularly monitoring and continually updating services in a way that increases accountability for all activities with the overall aim of maintaining and improving standards of care. Prescribing is no different from any other pharmaceutical service and should comply with the principles of clinical governance. There should be clear lines of responsibility and accountability within organizations with regards to all aspects of prescribing so that prescribers and their managers are aware of their roles. Organizations should promote clinical audits and prescribers should participate in these audits where appropriate, as well as auditing their own prescribing performance against standards such as the National Prescribing Centre Competency Framework (see Ch. 17). Taking any drug will put a patient at risk of side-effects or adverse drug reactions. Prescribers must balance these risks against the potential benefits of the treatment. Organizations and individual prescribers must document errors and near misses so that all can learn and standards can be continually improved. Prescribers should have up-to-date therapeutic knowledge, be aware of national and local clinical guidelines and base their prescribing decisions on the best evidence available. Achieving concordance is key to ensuring effective treatment and prescribers must communicate the benefits and risks of the available treatment options to patients or their carers.

Code of Ethics

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB) Code of Ethics directs pharmacist prescribers to prescribe responsibly and in the patient’s best interests. It provides further direction for pharmacist prescribers around limitations (what they can prescribe, who they should not prescribe for and the information they must have access to before they can prescribe), knowledge they should have, communication and the practicalities of combining prescribing and dispensing (Box 16.4).

Box 16.4 Code of Ethics and standards service specification for pharmacist prescribers

| Limitations | Pharmacist prescribers must limit their prescribing to areas within their own professional expertise and competence |

| Pharmacists should not normally prescribe for themselves, family or friends except in emergencies | |

| Pharmacists must only prescribe when they have adequate knowledge of the patient’s health and medical history | |

| Knowledge | Pharmacists must be aware of local and national clinical guidelines and take these into account when prescribing |

| Practicalities of prescribing | Pharmacists must make appropriate patient assessments and only prescribe when there is a genuine clinical need |

| Where pharmacists can prescribe and dispense they must ensure that these roles are separated whenever possible | |

| This could be achieved by an accuracy checking technician or another pharmacist checking the final dispensed product | |

| Pharmacists must keep accurate and comprehensive records of the consultation with the patient and of the items that they have prescribed | |

| Relations with other professionals | Pharmacists must refer the patient to another practitioner when appropriate |

| Pharmacists must communicate effectively with other practitioners involved in the care of the patient |