Chapter 49 Substance use and misuse

Introduction

This chapter begins with some background information before it summarizes current thinking on drug misuse and drug dependence. It then looks at treatment provision in the UK and the range of interventions used, focusing on the practical provision of the two main pharmaceutical interventions – needle exchange and substitute pharmacotherapy provision.

Terminology

Terminology used in the field of drug misuse can be confusing, even for those who work in the area. There are political and philosophical differences behind the use of various terms, a discussion of which is outside the scope of this work. However, it is important to be aware that a variety of terms essentially refer to the same things.

‘Drug use’ in the context of this chapter is the term commonly used to refer to the consumption of psychoactive substances without medical or healthcare instruction. The term ‘drug misuse’ refers to drug use that is problematical and incurs a significant risk of harm. These two terms are often used interchangeably. ‘Drug abuse’ essentially refers to the same thing but its use is less common in recent publications. ‘Substance’ is sometimes used in place of ‘drug’ to include non-medicinal chemicals such as solvents, alcohol and nicotine.

‘Dependence’ or ‘addiction’ refers to the compulsion to continue administration of psychoactive substance(s) in order to avoid physical and/or psychological withdrawal effects. Drug dependence is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as:

a cluster of psychological, behavioural and cognitive phenomena of variable intensity, in which the use of a psychoactive drug (or drugs) takes on a high priority. The necessary descriptive characteristics are preoccupation with a desire to obtain and take the drug and persistent drug seeking behaviour.

Dependence can be classified in more detail, as found in the Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry.

‘Drug user’ is commonly used to refer to someone who participates in drug/substance use. The term ‘drug misuser’ refers to someone undertaking drug use in such a way that it is problematical and presents a significant risk of harm. Again the two terms tend to be used interchangeably. Terms such as ‘drug addict’ and ‘drug abuser’ are less used in recent literature.

Historical note

Historical works on psychoactive drug consumption make interesting reading and help us to understand how current drug policy came to be formulated. They indicate that psychoactive drug use is not a new phenomenon in society – psychoactive drug use has been recorded as part of some societies more than 7000 years ago. More information is given by Berridge & Edwards (1998).

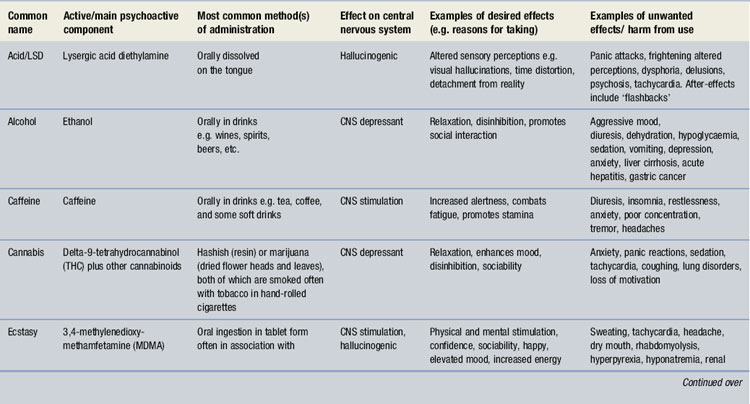

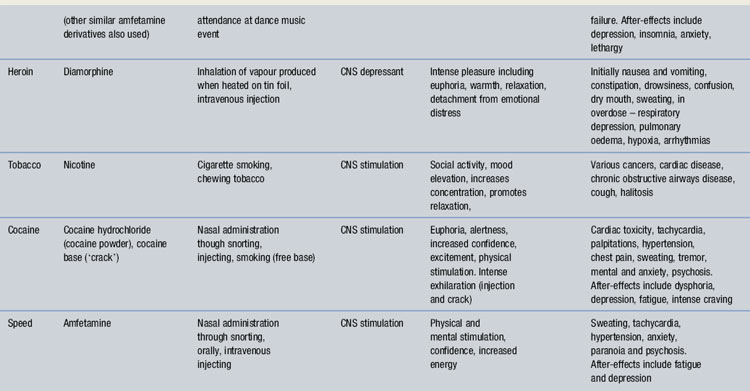

Substances that are used and their effects

Table 49.1 lists some commonly used psychoactive substances in western societies and summarizes their effects. (Nicotine is included for completeness, but the role of the pharmacist in smoking cessation is covered in Ch. 5.) The unwanted and harmful effects of some drugs relate to prolonged and excessive use, whereas others occur with single doses of smaller amounts. The method of administration also influences the extent of the risks, e.g. injecting opiates presents greater health risks than taking them by vaporization (‘chasing the dragon’). Table 49.1 is presented as a guide, but it is not comprehensive. The books Drugs of Abuse (Wills 2005) and Living with Drugs (Gossop 2007) and the DrugScope website (http://www.drugscope.org.uk/) provide extensive information and the common street names of various drugs. DrugScope is a UK charity that provides information on drugs and support mainly for policy makers and service providers.

Why do people use psychoactive drugs?

Benefits

The question of why people use psychoactive drugs is a multifaceted question to which there is no simple answer. As a crude summary, people who use psychoactive drugs do so because they expect to experience a benefit in some way. They may be aware of risks too, but these are weighed up against the perceived benefits and the decision to take the drug prevails. The extent of the benefits and risks will of course vary depending on the drug, the circumstances and how it is used.

The expected or perceived benefits may include the attainment of pleasurable feelings (e.g. relaxation), increased social interaction (e.g. reduced inhibitions), alteration of the person’s psychological condition to a more desirable state (e.g. escapism), physical change (e.g. anabolic steroids taken by bodybuilders) or avoidance of withdrawal symptoms in someone who is dependent on a drug. The reasons for use may change over time with the same user; for example opiate use may be commenced to escape from reality but then continued to avoid the withdrawal effects.

Choice of drug used

The decision to use a drug may be influenced by many things, including:

Risks

The risks from various drugs are not equivalent. Their incidence and nature vary with the drug and how it is used, the individual concerned and the circumstances. Examples of such variables include the drug substance, the presence of impurities, the dose, the frequency of use, the route of administration, the legal status of the drug, related social and financial circumstances, the personality of the individual drug user and the interaction between drug use and lifestyle.

Weighing up benefits vs risks

If the benefits from drug use are experienced before the harm, or to a greater perceived extent than the harm, positive endorsement of drug taking occurs. Following positive endorsement, drug use may, but does not necessarily, continue.

Control and dependence

A lack of specific types of neurological control is sometimes given as the reason why some people develop addictions to specific psychoactive drug(s) whereas others do not. Published studies can be criticized as the models of behaviour are largely shown in animals not humans, making the assumption that the two findings are directly transferable. Nevertheless, neurological processes manifest positive and negative reinforcement of drug seeking and taking behaviours, with genetic variations influencing these.

The level of control a drug user has over his use will influence the balance between the benefits and harms experienced. With controlled use, harms can be prevented or contained, e.g. the quantity of alcohol consumed may be controlled to avoid unwanted effects. In uncontrolled use, harms can escalate. Uncontrolled use is a characteristic of drug dependence.

When a person loses control over his drug consumption, or rather drug consumption controls the person, this may be described as dependence. Drug dependence can present a significant amount of risk and harm to the individual and to society. There is a clear association between drug dependence and social deprivation. In areas where social deprivation is high there tends to be a greater incidence of drug problems. However, drug problems are not exclusive to deprived areas and can be found in most parts of the UK, in both urban and rural environments. Please remember at this stage that drug use and drug dependence do not refer to the same thing.

Withdrawal

When a person stops using a substance they are dependent on they often experience withdrawal. Withdrawal can be described in two forms:

Physical withdrawal effects

These are physical signs and symptoms experienced when the drug is removed. Examples include seizures in alcohol withdrawal, stomach cramps and severe influenza-type symptoms experienced in opiate withdrawal, palpitations and anxiety in cocaine withdrawal, insomnia in nicotine withdrawal. Physical withdrawal effects can be quite severe and tend to be of shorter duration than psychological withdrawal effects. For example the acute physical withdrawal stage from heroin lasts usually no more than 7 days.

Psychological withdrawal effects

These are psychological disturbances experienced when a drug is removed. These cannot be so easily observed or measured in the way that many physical withdrawal effects usually can, but they must not be underestimated. Psychological withdrawal includes intense craving, intense emotional experiences such as unmasking of grief, inability to cope, altered mood and depression, which may be prolonged and severe. It tends to be of long duration and contributes markedly to relapse back to drug use. For example, cravings may be induced by situations, paraphernalia or locations many years after last consumption.

The harms relating to psychoactive drug use and dependence

The risks and harms that drug use and dependence can present to the individual and society vary with the drug taken, the individual and the circumstances in which the drugs are taken. It is not possible to list all possible consequences from drug use/misuse in this chapter, but these are dealt with in the ‘Key references and further reading’ section (Appendix 5). The risks are categorized below.

Health problems

These affect the individual drug user and include physical and psychological health problems, which can be large and complex. As well as being caused by the individual substances concerned, health problems may relate to the method of administration. For example, injecting drug use is associated with damage to the circulatory system. Blood-borne virus infection (e.g. with HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C) is associated with the sharing of injecting equipment. Pharmacists are largely involved in preventing or reducing the harm from drug dependence, benefiting both the individual and society. Hence the role of the pharmacist in drug dependence is about contributing towards individual and public health and safety.

Social problems

The social problems that relate to drug dependence must not be underestimated. It is often these that drive people to seek treatment. Social problems may include poverty (e.g. social deprivation, exclusion or failure in education, inability to obtain or sustain employment, spending of income on drugs), damage to family relationships, difficulties forming relationships, exclusion from society and homelessness.

Drug-related crime

Drug-related crime includes not only the criminal activities committed against the Misuse of Drugs Act (see below) for which the individual is punished, but also crime that impacts on communities and society at large. The latter may relate to the acquisition of drugs or the effects of drugs, e.g. burglary to obtain money to buy drugs, robbery, violence associated with drunkenness, drunk/drug driving. Drug-related crime is of concern to society and is one of the reasons why treatment of drug problems and drug dependence is a key public health issue. Additionally there is evidence that treatment of drug dependence contributes towards a very marked reduction in drug-related crime. Hence treatment benefits not only the individual in terms of improved health but also society by making communities safer.

Drug users are often at greater risk than non-drug users of being victims of crime, e.g. violence associated with debt to drug dealers, prostitution, robbery and mugging if homeless or intoxicated.

Legislation

Misuse of Drugs Act

The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 classifies drugs into Class A, Class B and Class C. The purpose of this legislation is to define the penalties imposed for the illegal undertaking of various activities, e.g. possession, supply, import, export. These are summarized in Table 49.2. For more information see: http://www.release.org.uk/. This classification system is different from the Misuse of Drugs Regulations that largely govern dispensing and other activities of the pharmacist. For guidance on dispensing of controlled drugs, see the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB) website (http://www.rpsgb.org.uk) or the very comprehensive National Prescribing Centre guidance issued in February 2007: http://www.npc.co.uk/controlled_drugs/cdpublications.htm.

Table 49.2 Classification of some commonly misused substances according to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971

| Class | Drugs | Maximum penalties |

| A | Cocaine including crack cocaine, diamorphine (heroin), dipipanone, ecstasy, LSD, methadone, morphine, opium, pethidine | Seven years imprisonment and/or unlimited fine for possession. Life imprisonment and/or fine for supply* |

| B† | Most amphetamines§, cannabis‡, codeine, dihydrocodeine, methylphenidate | Five years imprisonment and/or fine for possession Fourteen years imprisonment and a fine for supply |

| C | Benzodiazepines, anabolic steroids and growth hormones | Two years imprisonment and/or fine for possession Fourteen years imprisonment and/or fine for supply |

* The term ‘supply’ includes drug trafficking and unauthorized production.

† If Class B drugs are prepared for injection they become Class A.

§ Unless prepared for injection when amfetamines become class A.

Road Traffic Act

This 1988 act makes it illegal to be in charge of a motor vehicle if ‘unfit to drive through drink or drugs’. This includes both illicit substances and prescribed medicines. Drivers are required by law to notify the Driving and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) if there is any reason that the safety of their driving may be impaired, e.g. disability, the misuse of drugs, the need for medicines that impair reactions or cause sedation. The responsibility for notification lies with the patient, not healthcare professionals (see the publication At a Glance Guide to Medical Aspects of Fitness to Drive (DVLA 2008), which is also available online: http://www.dvla.gov.uk/medical/ataglance.aspx.)

The management of drug use and dependence

This chapter focuses on problematic drug use and specifically on drug dependence. The reason for this is that pharmacists are primarily involved with the treatment of dependence rather than interventions aimed at recreational and non-problematic drug use. Drug dependence must, however, be kept in perspective as not everyone who tries drugs or uses drugs will become dependent on them. The prevalence of drug dependence on a population basis is relatively small compared to national statistics that estimate numbers of people who have ever tried drugs. However, the extent of harm from drug dependence can be large and affect not only the individual but their families and communities, hence the need for effective strategies to support people in changing their drug use is great.

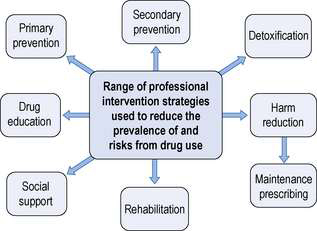

A range of strategies is used to prevent, limit the extent of and address the problems associated with drug use and dependence. These will be summarized in order to illustrate the contribution made by pharmacists. Figure 49.1 illustrates the range of strategies used in preventing, reducing and controlling drug use and dependence and managing the adverse consequences. These will be briefly reviewed.

Fig. 49.1 The range of professional intervention strategies used to reduce or manage drug use and dependence.

Primary prevention

Primary prevention is concerned with preventing people from starting to use drugs. Target groups include vulnerable groups such as school children, looked after children and young people who have left education. It includes warning of the harm that can result from drug use and dependence using health promotion and education campaigns. Primary prevention also includes legislation, as the illegal nature of many drugs may prevent some people from using them. It is difficult to evaluate the impact of primary prevention activities as so many factors may influence the person’s decision to use or not to use drugs. Reliable research in this area can also be difficult to undertake. This does not mean that primary prevention activities should not be used. They are very important for informing children and young people about drugs and their effects. Such activities should not be scaremongering but need to be factually accurate to give young people an informed knowledge base about drugs which reflects what they may see within society.

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention is aimed at people who use drugs by discouraging further use. Examples of secondary prevention are giving advice to prevent problems such as overheating and dehydration to ecstasy users, discouraging heroin smokers from progressing to injecting, and warning on the risks and guiding on the use of CNS depressant drugs (such as heroin and methadone) by stimulant users (such as ecstasy and amfetamine) when depressant drugs are used to assist with the ‘come down’ following CNS stimulation.

Drug education

Drug education is a tool used in primary and secondary prevention campaigns and includes leaflets, booklets, videos and posters. People who are dependent on drugs may also benefit from drug education as they may not be fully informed on the drugs they use or may consider using, e.g. long-term risks and overdose prevention. Drug education is also a key part of harm reduction, giving people information to assist them in minimizing risks from drug taking, e.g. safer injecting information. Drug education may be provided by a range of people, e.g. teachers, youth workers, health promotion workers, medical and nursing staff and police officers and should always be appropriate for the target group. For example, advice given to dependent heroin smokers would differ from that aiming to prevent heroin use in school children. Pharmacists may be asked to provide talks and should only deliver such talks if they feel competent to do so and capable of answering questions. Before such talks are given it is advisable to get advice and information from a credible source such as publications by drug charities and health promotion units. Seeking the support of the local drugs service may also be prudent. Inaccurate advice can be harmful and discredited.

Social support

Social support refers loosely to non-medical/pharmacological interventions that can be made. These may include practical advice and assistance (e.g. seeking housing, benefits advice, provision of hostel accommodation) and use of psychological tools such as motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing aims to assist people in examining their drug use and the impact it has on their lives and those of others to move people towards a psychological state where they are motivated to change their behaviour and attempt to change their drug use. There are many psychological tools that are used by clinical psychologists and counsellors in the treatment and support of people with drug problems. Pharmacists should be aware of the need for a holistic approach to care, using not only pharmacological therapies where appropriate, but non-drug treatments too. Some pharmacists with a special interest (PwSI) who have specialized in drug misuse have developed skills in motivational interviewing and other psychological support tools.

Detoxification

Detoxification refers to the provision of treatment to help someone who is dependent on a drug to stop using it. Examples include the use of diazepam at gradually reducing doses in benzodiazepine dependence and the use of nicotine replacement therapy. The aim of detoxification is for the person to become abstinent from the drug on which they are dependent.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation may include a detoxification process followed by a period of social support and intensive psychotherapy to facilitate sustained change. Alternatively, it may comprise the social support and intensive psychotherapy phase only, with successful detoxification being a requirement for entry on the programme. Rehabilitation is usually provided within a ‘therapeutic community’ – participants live in the environment where treatment is given, often for several months. Often people who enter rehabilitation programmes have serious, complex and chronic drug dependency problems and may previously have experienced community-based treatment. The outcomes from various drug rehabilitation programmes were studied as part of the National Treatment Outcomes Research Study (NTORS), undertaken in the UK. Improvements were seen in drug use, physical health, psychological health and involvement in crime. At 4–5 year follow-up, 47% of people who had previously been dependent on opiates were abstinent, with reductions in frequency of opiate use seen in a significant number of the remainder (Gossop et al 2001).

Harm reduction

Harm reduction is a generic term to describe the range of interventions used to reduce the adverse consequences of drug dependence experienced by both individual drug users and society. Strategies prioritize goals in treatment, recognizing that, whereas abstinence from drug use may be the end goal, in some cases and for some drugs it is not always immediately achievable. Instead the risks and harm to the individual and others are reduced, by a process of prioritization which the individual is involved in defining.

Examples of harm reduction interventions include the provision of sterile injecting equipment and information to drug injectors to prevent the sharing of injecting equipment (to prevent the transmission of viruses such as HIV, hepatitis B and C). Minimizing the prevalence of such diseases also protects the non-injecting community.

Harm reduction also includes the provision of substitute therapies with the aim of reducing illicit drug use and reducing drug-related crime, hence benefiting communities. This is often done by providing substitute therapy, either at an adequate maintenance dose or as a detoxification agent. Pharmacists are frequently involved in the provision of harm reduction services (see later).

Service providers

Drug and alcohol services in the UK can be broadly grouped according to their different sources of funding. The three main groups are described below.

Statutory sector

The statutory sector comprises NHS and local authority services and includes prevention interventions, harm reduction services and abstinence-directed care. A large amount of NHS drug treatment is provided in GP surgeries, either by GPs alone or in partnership with GP liaison workers from specialist drugs services, who advise the GP on prescribing and offer patient counselling and support. Community drug teams (CDTs) are attached to NHS trusts, often led by psychiatrists. CDTs may provide primary care drug treatment, either through GP liaison work or with their own doctors running special clinics, similar to outpatient clinics. CDT services are typically provided by doctors and psychiatric nurses but some employ pharmacists to advise on or undertake prescribing and manage on-site dispensing. Statutory sector needle exchanges also exist, often staffed by specialist nurses.

NHS services also include secondary care, where treatment such as inpatient detoxification from alcohol and other drugs is provided, typically over a short time period such as 2 weeks.

Voluntary sector

Voluntary services are particularly prevalent in the substance misuse field because they developed quickly in response to the threat of HIV in the mid-1980s. The voluntary sector services receive funding from a range of sources (e.g. NHS, criminal justice money, local authorities, grants and donations) and are usually registered charities, with paid workers and/or volunteers operating under a management committee structure. Workers may come from a range of backgrounds, e.g. nursing, social work and community work. Some projects employ current or ex drug users. Services may include:

Other voluntary sector services offer spiritual and practical support, e.g. hostel accommodation and self-help groups. The voluntary sector also may represent drug users’ views in advocacy, policy and service planning (e.g. The Alliance, see http://www.m-alliance.org.uk).

Private sector

The private sector includes ultra-rapid detoxification units, inpatient detoxification clinics, private primary care doctors and residential rehabilitation providers, private psychotherapists and alternative therapy providers. Funding for some of these treatments may come through the statutory sector but they are most often paid for by the patients or their families. Some pharmacists work in private sector treatment facilities advising on prescribing and dispensing. Private services offer a wide range of choice to patients but access is obviously limited by ability to pay. Ultra-rapid detoxification is not recommended for safety reasons.

Pharmaceutical care

This section focuses on pharmaceutical care of drug users, specifically looking at aspects of good pharmacy practice. The reader is referred for more detail to the National Treatment Agency publication Best Practice Guidance for Commissioners and Providers of Pharmaceutical Services for Drug Users (February 2006), available online at: http://www.rpsgb.org/pdfs/pharmservdrugusersguid.pdf.

The role of the pharmacist in drug dependence

Community pharmacists

Community pharmacists are ideally placed to contribute to the care of drug users. In addition to the health gains for the patient, there are several advantages for drug users, the community and pharmacists from providing care:

The two most common services provided by community pharmacists to prevent and reduce harm are needle exchange and dispensing services. These are discussed later. For more detailed information on community pharmacy and drug misuse, the reader is referred to Sheridan & Strang (2002).

Hospital pharmacists

Hospitals should have guidelines for the admission and discharge of drug users to ensure that any ongoing prescribing is continued. There should also be policies and specialist support available to ensure treatment can be initiated if a need is identified. This is especially important for cases when people are admitted to general medical or surgical wards for matters not relating to their drug use. The teams on these wards may not be familiar with substance misuse prescribing. Hospital pharmacists may contribute to the formulation of such guidelines. Issues to include are:

Hospital pharmacists also play a key role in advising on co-prescribing for people on substitute therapies such as methadone. Many drug interactions can occur and changes in doses may be necessary if methadone is co-administered with enzyme-inhibiting or enzyme-inducing drugs. Treatments for epilepsy and HIV/AIDS in particular must be carefully considered. Clinical issues of co-prescribing cannot be covered here; instead reference to appropriate texts on drug interactions is advised (e.g. Stockley 2005).

Specialist pharmacists (PwSI)

There are pharmacists who specialize in drug dependency, many of whom come under the umbrella term of ‘pharmacist with a special interest’ (PwSI). Some provide services from community pharmacies whereas others may be based in GP surgeries or specialist drugs services. They may be prescribers, or provide support to clinical colleagues, e.g. by advising on prescribing or providing drug information. They may also oversee dispensing and liaise with (other) community pharmacists. Others undertake strategic roles such as coordinating local pharmacy needle exchange services or overseeing the pharmacy contribution to shared care (see below).

Needle and syringe exchange

Background

Needle and syringe exchange (NSE) began in the UK in the mid-1980s in response to the threat from HIV. Prior to this, availability of clean injecting equipment was limited due to the belief that this would prevent people injecting. There was grave concern in the mid-1980s regarding the threat to public health that HIV presented and fears of an epidemic unless something was done to reduce its spread. Large health education campaigns were aimed at those at high risk, e.g. gay men, people having casual unprotected heterosexual sex and injecting drug users. In order to enable injecting drug users to follow the advice not to share needles and syringes, NSE programmes were started in many countries. These programmes were studied in several research projects which found that NSE programmes were effective in reducing the transmission of HIV without causing an increase in injecting drug use. A comparative study of 12 cities was conducted by Stimson et al for the World Health Organization (WHO); this is described in the text Drug Injecting and HIV Infection (Stimson et al 1998). An excellent summary article was published by MacDonald and colleagues (2003). Ksobiech (2003) published a meta-analysis of 47 studies looking at needle exchange outcomes and concluded that blood-borne virus transmission was significantly reduced by NSE availability.

In the early 1990s hepatitis C (HCV) was identified. This blood-borne virus appears to be highly transmissible among injectors and there is as yet no vaccine, although recent research is promising. It has been shown to be spread through the sharing of injecting paraphernalia, including needles and syringes, but also probably other items used in the preparation of illicit injections, for example the spoon or metal container in which the drug is mixed with water, the makeshift filter used to remove insoluble materials and adulterants and potentially items such as swabs used to clean injecting sites. Recently an odds ratio of 2.44:1 (95% CI, 1.44-4.12) has been calculated predicting the risk of contracting HCV through paraphernalia sharing when never having shared needles and syringes (Mathei et al 2006). It is important that NSE is widely available in order to limit the spread of blood-borne viruses. Community pharmacies contribute to the network of needle exchanges. They increase coverage, especially for those reluctant to access specialist agencies, at times when agencies are closed (such as weekends) and in areas where no such agencies exist. Privacy may be limited in community pharmacies, so there may be limits to the extent of dialogue and examination that can take place. Additionally drug users may not perceive the pharmacist to be knowledgeable about drug misuse so pharmacists need to be proactive in demonstrating their competence.

Practical issues in NSE provision

Training

Before any pharmacist begins to provide any new service it is important that they are adequately trained and competent to provide the service. NSE is no exception. Therefore pharmacists and their staff should undertake training on issues relating to needle exchange. Specialist agencies may be able to offer training for pharmacists and their staff.

Hepatitis B vaccination

Although pharmacists and their staff do not handle loose needles during the needle exchange process, it is a wise health and safety precaution for all staff to be vaccinated against hepatitis B (HBV). There are no vaccines for hepatitis C or HIV. Community pharmacists should discuss HBV vaccination for staff with NSE scheme coordinators or the local public health consultant.

Needle exchange procedure

NSE involves supplying clean, sterile injecting equipment in exchange for used equipment, which is returned in a sealed sharps container. As well as supplying equipment, NSE services should provide advice and check injecting sites, with referral to medical services when problems such as abscesses are identified.

Needle exchange schemes are usually coordinated within the health locality, so local policies may exist and support and guidance should be available to pharmacists. Failing this, policies and procedures for needle exchange need to be put in place in order to minimize risk. Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2009), National Pharmaceutical Association, National Treatment Agency, public health departments and needle exchange agencies can assist. Adequate storage facilities are essential. Used equipment returned to the pharmacy in a bin should be placed in a larger bin by the client, stored in a separate area from clean equipment and away from medicines. These bins are sealed when full and collected for incineration by clinical waste disposal companies.

To maximize the public health benefits, injecting drug users need to be able to use a clean set of equipment for each injection and every set of equipment supplied should be returned for incineration. In order to try to meet this aim, adequate amounts of injecting equipment should be supplied, bearing in mind that some crack cocaine injectors may be injecting very frequently (e.g. 15 times per day or more). Also the number of needles and syringes supplied does not necessarily equate with the number of injections the person themself takes, as needles can be damaged or broken during access attempts or distributed to peers. The number of needles and syringes that can be supplied in any one visit may be dictated locally by scheme coordinators. It is wise to discuss supply quantities with local needle exchange agencies to ensure continuity in service provision. Capping of numbers of sets of equipment allowed is not advocated and dilutes harm reduction effectiveness. In Scotland the Lord Advocate’s Guidance dictates the number of sets that can be supplied. A sharps bin should be supplied with every exchange. Bins range from pocket size to large clinical waste tubs. The return of equipment should be strongly encouraged and local campaigns to promote returns participated in. Written advice on safe disposal accompanied by verbal emphasis is important. However, if a person requests needle exchange but has no used equipment to return, it is advocated that supply of clean needles and syringes is made, as the health risks of not supplying are great. Pharmacy staff should not open disposal bins to count the number of sets returned. Instead estimates of returned numbers should be made based on the number of returns reported by the service user and the size and estimated fullness of the returned disposal bin.

Record keeping and audit

Records need to be kept in order to audit the pharmacy NSE service. In order to encourage use, pharmacy NSE should be provided on an anonymous basis (no names recorded). Attractions of pharmacy-based NSE are the anonymity and low threshold access. Too many obstacles will discourage use. In some schemes, pharmacies issue cards which give the service user an identification number or code. This can be used to record service usage but it also allows discreet service provision, as the person only needs to show the card to indicate that they require needle exchange. This can be helpful in a crowded pharmacy. The advantage of having a record for each service user is that it can quickly be seen if someone returns used equipment or not. Those who do not can be targeted with information and firm requests to return equipment. The disadvantage is that in a busy pharmacy this system can be too time-consuming. Additionally some people do not want to carry a card that identifies them as an injector. As a basic requirement, the daily number of sets of injecting equipment supplied and the approximate number returned should be recorded and data compiled for weekly or monthly audit purposes. Data should be returned to the scheme coordinator where one exists. Pharmacies with poor return rates should seek the advice of specialist drugs agencies and the scheme coordinator on strategies to increase return rates and be proactive in encouraging returns. In some areas, including Leeds, novel ideas such as client completed ‘order forms’ have been successful in minimizing the pharmacy burden of paperwork but providing auditable records of supplies.

Risk management

A written procedure for needle exchange should be in place and followed. Body fluid spillage kits should be kept in all pharmacies as a matter of routine, irrespective of whether the pharmacy is part of an NSE scheme, and staff should be trained in their use. In the event of an incident (e.g. a patient bleeds or vomits on the floor), the kit should be used. It should be noted that use of the kit is dictated by the situation and not the perceived risk presented by the patient, i.e. use of the kit does not depend on whether the patient is a known injector or not.

Chain mail gloves should be kept in needle exchange pharmacies for use in the event of loose used injecting equipment requiring disposal. However, this is only a precaution, as the needle exchange scheme procedure should be such that it minimizes the risk of such events. If any such events occur they should be documented as part of the pharmacy’s critical incident scheme. Procedures should then be reviewed to see if anything could be done to avoid such an incident in the future.

Links with specialist services

Pharmacy NSE providers should have links with local drugs agencies and know what services they provide. Often younger and newer injectors use pharmacy needle exchanges because of the low threshold and discretion. These people may also not want to stop injecting and consider agencies to be for people with drug ‘problems’ or people who want to stop using. Women may also prefer the anonymity of using pharmacy services. Female drug users are often extremely stigmatized, especially if they are also mothers. The pharmacist may be the only healthcare professional these service users have contact with. Knowledge of other local services means that the pharmacist can advise when a need is identified or an opportunity arises. The pharmacy should consider itself a gateway to specialist services. Some specialist agencies may be able to supply pharmacists with targeted written information for drug injectors, such as safer injecting leaflets, and with free condoms to reduce sexually transmitted diseases. Safer injecting leaflets should not be available for self-selection but should be targeted at injectors. The pharmacist needs to ensure they are competent to provide advice and allow a rapport with the client to develop over time. This in turn will facilitate the provision of information, advice and signposting when the time is right.

Use of pharmacotherapies in drug dependence

The term pharmacotherapy in this context refers to any drug treatment used to assist in the management of drug dependence or symptoms of withdrawal. Substitute therapy refers to drug treatment that replaces an illegal drug with a legal one of the same or similar pharmacological class. For example methadone is a substitute for opiates such as heroin. Non-substitute drugs may also be used to control withdrawal symptoms (e.g. lofexidine to manage opiate withdrawal) and to manage symptoms secondary to withdrawal (e.g. loperamide to manage diarrhoea associated with opiate withdrawal).

Role of pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy can be mistaken both by patients and by professionals as an all-encompassing solution. However, it is one of several tools used in the care of drug dependence. Alone it cannot stop someone using drugs but it can facilitate change in motivated people by providing what many describe as ‘breathing space’. For example substitute therapy can prevent withdrawal symptoms thus giving the person a chance to sever links with illicit drug suppliers. Substitute therapy also removes the need to commit crime to obtain money for drugs. Pharmacotherapy therefore has benefits for both the individual and society. Substitute therapy, from a risk-reduction point of view, is also preferable to illicit drugs because the quality and dose of the product is assured.

There is an ever increasing evidence base of literature to support the provision of pharmacotherapy in drug dependence. In particular most literature focuses on methadone and high-dose buprenorphine. Evidence shows maintenance doses of treatment alone improve patient physical health and mental health outcomes, reduce drug-related deaths and improve social functioning. However, outcomes can be enhanced with appropriate ‘wrap around’ services providing support and counselling, where the person freely is willing to take part. Coercion into such services or psychotherapy is not advocated.

The psychoactive and non-psychoactive effects of substitute therapies are not usually the same as the illicit drugs they replace and an awareness of this in the patient at the start of treatment is important. For example, methadone is used as a long-acting substitute in opiate dependence. When taken orally it does not produce euphoria and it can cause lethargy and a feeling of ‘heaviness’ not associated with heroin use.

All who receive pharmacotherapy, especially in the early stages of treatment, may not achieve complete abstinence from illicit drug use. It is a common misconception that substitute treatment should be given at a reducing dose leading in a short time period to abstinence from illicit drug use. Whereas in a minority of patients this will produce sustained benefits, for many, rapid detoxification has been shown not to produce long-term abstinence from illicit drugs. Instead a period, often prolonged, of maintenance therapy at an adequate dose may be necessary. This may last for many years.

Methadone

Methadone is used as a substitute drug in opiate dependence. Its long half-life (24–48 hours) makes it suitable for once-daily dosing in the majority of cases, although a few patients prefer to divide the dose. Providing it is given in adequate doses and for a satisfactory length of time, there is substantial evidence to suggest that methadone treatment has several benefits:

As can be seen, the benefits extend beyond the individual patient into the community. Less injecting will reduce the risks of blood-borne virus transmission. The reductions seen in drug-related crime have been large. These findings have been reported in a range of publications. As a summary, the reader is referred to the NICE technology appraisal of methadone and buprenorphine (January 2007), available online at: http://www.nice.org.uk/TA114. An updated version of the Department of Health publication Drug Misuse and Dependence, Guidelines on Clinical Management is now available.

Failure to reduce or prevent illicit drug consumption is associated with maintenance doses of methadone less than 60 mg per day and premature pressure to abstain from methadone (Ward et al 1999). Before detoxification can be considered, treatment may need to be given at maintenance dose level for prolonged periods of time, with some people remaining on maintenance doses indefinitely. Withdrawal of treatment should begin only when the patient is willing to attempt this, as motivation is the key to success. Regular review of patients on maintenance doses and on detoxification schemes is necessary. In detoxification, the speed of dose reduction largely depends on how well the patient is coping. Reductions should be calculated as a percentage of the dose; hence towards the smaller end of the scale, dosing will be reduced by smaller quantities. For some people the small doses can be the hardest to reduce and some people remain on doses of as little as 1 mg and 2 mg per day for several months until they feel capable of stopping treatment completely. Psychological adjustment is very important at this stage, especially if drug use has been used as a coping mechanism. Withdrawal can take several months, even years. If the dose needs to be increased at any point during detoxification, emotional support and reassurance may be necessary as some people can regard such increases as failure.

It is important to discuss with patients potential overdose risks from combining CNS depressants, including alcohol. Healthcare teams need to understand that some illicit drug use may continue, especially at the early stages of treatment. During the initiation of treatment, this can be a time when there is a greater risk of overdose, due to the fact that treatment dosing will not yet be optimized and withdrawal effects are likely, leading to ‘on top’ illicit drug use. The patient must be advised of this risk and monitored closely. Several information leaflets are available which explain this to patients, e.g. the ‘Methadone Briefing’ from Exchange Health or the Department of Health-supported Going Over DVD. If illicit drug use continues at a similar frequency as it was before substitution therapy was introduced, it is important to review the dose and treatment goals with the patient. Methadone treatment may be suboptimal or the person is not ready to change their drug use. In this case methadone may be compounding the risks and other harm reduction strategies may be more appropriate.

Pharmacists should have a good understanding of the clinical aspects relating to methadone treatment before they begin providing methadone dispensing services. This should be gained as part of a continuous professional development plan if needed.

Safe storage in the home

If take-home doses are dispensed, pharmacists should discuss safe storage of methadone and other drugs in the home with patients, especially those with children. As little as 5 mg of methadone can kill a small child. Parents on methadone prescriptions should store take-home doses in overhead cupboards, which should be locked to prevent access by children. In addition parents should be advised not to consume medicines in front of children to prevent copying behaviours.

Other treatments

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist, used as an opiate substitution therapy instead of methadone. Its use is becoming more widespread as the evidence base develops. As it is a partial agonist, it antagonizes the effects of other opiates if they are used on top. The patient needs clear advice on initiation and counselling on the risks of attempting to overcome the antagonist properties, for example by using large amounts of opiate. This may present an overdose risk. Buprenorphine is used in sublingual tablet form and also has a long half-life, which facilitates daily or even every second day administration, although in practice daily use is usually preferred.

Lofexidine and naltrexone are also used in the management of opiate withdrawal. The former reduces some of the physical withdrawal effects from opiates by acting on the noradrenergic system, while the latter is an opiate antagonist used in relapse prevention. There are also recognized regimens to assist withdrawal for those with stimulant, benzodiazepine and alcohol dependence. When a person is dependent on more than one drug, withdrawal should be done one drug at a time. Further reading regarding these treatments is advised.

Urine screening and responding to symptoms

People receiving treatment for drug dependence may have their urine screened. This is done to check for evidence of compliance with prescribed regimens or to confirm for the consumption of illicit drugs. In some areas urine screen results may be used to make a decision on whether treatment is continued or not. Pharmacists should undertake training in this area of toxicology, as some over the counter and prescribed medicines can interfere with urine screens, giving false results. It is important to have an understanding of what medicines to avoid in people receiving treatment for dependence, so that patients and prescribers can be advised. This is also relevant to athletes subject to urine screens for banned substances.

Pharmaceutical dispensing services

Shared care

Shared care with regard to substance misuse is GPs, pharmacists, drugs services and the patient being in partnership to manage dependence within a formalized, structured scheme. Pharmacists participating in such schemes receive additional remuneration. Examples of schemes in the UK include those in Glasgow and Berkshire (Roberts & Bryson 1999; Walker 2001). Daily dispensing of controlled drugs is often advocated by prescribers, especially at the start of treatment, as it is believed to prevent leakage onto illegal markets. This means that the pharmacist is likely to be the healthcare professional with the most frequent contact with the patient as they see the patient daily, while the prescribing team may see them weekly or fortnightly. Pharmacists can play an important role in monitoring the patient’s health.

One of the benefits of shared care is that the workload of providing care is distributed locally. This prevents one or two pharmacies becoming overburdened and allows patients access to care within their communities. Participation of all or the majority of community pharmacies in the area is therefore vital for the scheme to succeed. To date this has not always been the case as some pharmacies have refused to provide services to drug users.

Before joining a shared-care scheme, pharmacists should consider any changes within the pharmacy that may be necessary. These should be discussed with the scheme coordinator who may be able to source financial assistance for such changes. For example is there enough space in the controlled drug cabinet to store dispensed controlled drugs waiting for collection? Consider the layout of the premises. What can be done to ensure an appropriate area is available to allow a respectful service to be provided? Is there a private area for methadone consumption? A private room is not always desired by patients but a discrete area can be very welcome. The Department of Health guidelines on drug misuse and dependence give more detail on the role of the pharmacist in shared care and cover issues such as information sharing and confidentiality.

Supervised consumption

The development of shared-care schemes for the management of drug dependence has led to an increased involvement of pharmacists, especially community pharmacists, in providing care to drug users. Many shared-care schemes require daily dispensing and supervision of consumption of all or most doses of substitute therapy, at least for the first 3–6 months of treatment. Supervised consumption was introduced because of leakage of methadone and other drugs to the illicit market contributing to overdoses in people who had not been prescribed the drugs.

Supervised consumption is a contentious area. Some patients view it as a useful part of treatment whereas others dislike it (Neale 1999). Supervised consumption can cause the patient much embarrassment. In a busy shop it may be very humiliating for a person if a pharmacist presents them with a measure of green liquid to drink or some tablets to take in front of other customers. As it is not ‘normal’ to take medicines in front of the pharmacist, people can quickly be identified as drug users. Much can be done by the pharmacist to show respect and consideration for someone when they are required to consume their treatment in the pharmacy, e.g. ask if they wish to wait until the shop is free of other customers before their dose is given. Pharmacists should also ask patients whether they wish to use a private area, if one is available. Patients appreciate such respect.

To assist with organization, it is suggested that pharmacists prepare all daily dispensed prescriptions the day before or early in the day required. Doses should be packaged appropriately in individually labelled containers and stored in the controlled drug cupboard, or as legislation dictates, with the prescription attached. When the patient presents for supervised consumption, the pharmacist should recheck the dispensed item. The patient should then be given the substance to be consumed together with a drink of water. The water helps take the taste of the medicine away, rinses the mouth (methadone has a high sugar content and is acidic, which could damage tooth enamel) and helps ensure the dose has been swallowed. Disposable cups should be used. Under no circumstances should patients be expected to share the same cup for water in case this presents a risk of infection transmission. The pharmacist should take the opportunity for discussion with the patient to assess their well-being and offer any advice as the opportunity arises. Over time a good rapport and therapeutic relationship can develop with patients.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain website on controlled drugs should be consulted for legal updates including recent guidance on instalment prescriptions.

Confidentiality

Communication between healthcare professionals is key in shared care. However, patient confidentiality must be borne in mind. Information should not be shared without consent. The patient should be involved in negotiations about care and treatment changes. When consulation with another service provider about a patient is necessary, this should be discussed with the patient. They should be informed of what the other service provider is to be told and their permission sought. Patient’s wishes should only be breached when a severe risk to health or well-being is considered to exist if confidentiality is not broken. All matters relating to the upholding or breaching of confidentiality should be documented.

Contracts

Some shared-care schemes advocate the use of contracts, which clearly state what is expected of the patient and what the patient can expect from the service. Often they dictate standards of behaviour and include clauses requiring the patient to fulfil certain criteria, including restricting the times when patients can collect prescriptions. It is debated whether contracts should be used specifically for patients with drug problems. They imply that it is expected that the person will not behave appropriately and as such stereotypes patients. Contracts are not routinely used within pharmacy health care for other patients and it can be argued that using one for drug users is unfair and discriminatory. Pharmacies should have practice leaflets as a matter of routine which are available to all pharmacy users. These may include a statement that all pharmacy customers have a right to privacy and respect and all pharmacy staff have a right to be treated with courtesy. If individuals present any problems, the pharmacist should deal with these individually. This applies to any customers who cause difficulty within the pharmacy. Pharmacies should have a complaints procedure which can be useful for reviewing response to such incidents.

When pharmacists are asked to use contracts as part of the shared-care scheme, the pharmacist should review the contract before agreeing. Pharmacists should ask themselves whether they, as a patient, would consider it fair to sign such terms. The contract should not imply that it is expected that the person cannot behave or will cause problems.

Restricted collection hours for drug users should also be considered with caution. Pharmacists are required to dispense prescriptions with ‘reasonable promptness’. Refusing to dispense a prescription during opening hours because a person has not arrived within a designated collection time may be considered discriminatory and is certainly unfair.

Locums

All standard operating procedures for pharmacy services should be documented and available for locums to use. This includes needle exchange and supervised consumption. It is important that all locums are aware of all the services provided, including those to drug users, and are briefed on the completion of any necessary documentation such as needle exchange usage.