Potential risks of sedation and anaesthesia

Clinical Tip

•

Before commencing sedation or anaesthesia, the patient should be assessed in the context of how the major body systems are likely to cope with the adverse effects of the drugs employed, and also in turn how the course of anaesthesia is likely to be influenced by the patient’s condition. Potential problems should be anticipated and prepared for in advance.

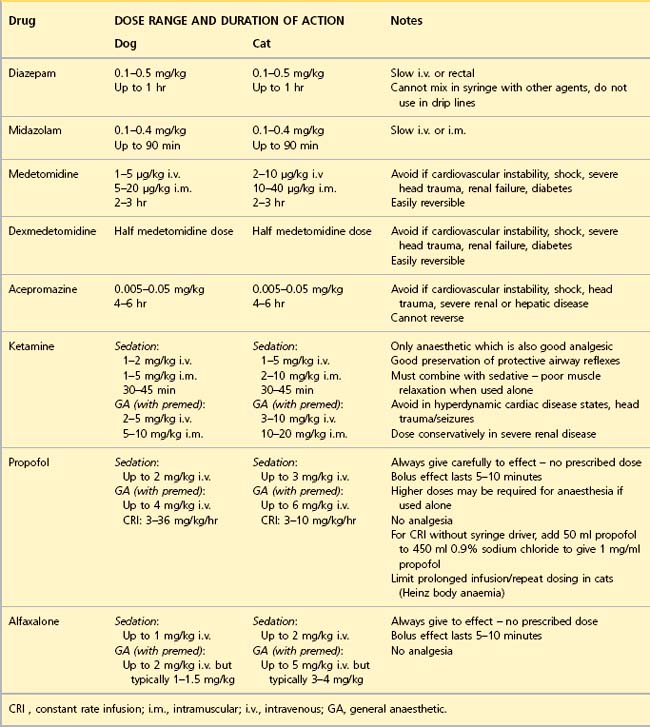

See Tables 39.1 and 39.2.

Table 39.1 Potential adverse effects of anaesthesia on body systems

| Body system |

Adverse effects |

| Cardiovascular |

Reversal of peripheral vasoconstriction which the patient may be relying on to maintain perfusion of vital organs Bradycardia or tachycardia |

| Respiratory |

Reduced ventilation or apnoea Ventilation/perfusion mismatch |

| Nervous |

Direct central nervous system suppression Raised intracranial pressure Reduced cerebral or spinal perfusion |

| Renal |

Reduced renal perfusion |

| Hepatic |

Reduced hepatic perfusion |

| Gastrointestinal |

Increased risk of regurgitation and subsequent aspiration |

| Temperature |

Hypothermia |

Table 39.2 Potential effects of patient condition on the course of anaesthesia

| Patient condition |

Effect on anaesthesia |

| Cardiovascular compromise (e.g. hypovolaemia) |

Risk of overdose (e.g. due to reduced volume of drug distribution, delayed response to intravenous injection) Reduced cardiac output increases rate of inhalation anaesthetic uptake resulting in more rapid inhalation induction Reduced hepatic and renal perfusion reduces metabolism and elimination of drugs |

| Respiratory compromise |

Reduced ventilation results in slower onset of inhalation anaesthesia and a slowed response to altered inhalation anaesthetic concentration |

| Central nervous system disease |

Reduced level of consciousness increases sensitivity to all sedatives and anaesthetic agents |

| Renal disease |

Reduced renal elimination of drugs, prolonging duration of effect |

| Hepatic disease |

Reduced hepatic metabolism of anaesthetic drugs, prolonging duration of effect |

| Hypoalbuminaemia |

Increases nonprotein-bound, active concentration of many drugs, increasing sensitivity to these drugs |

Hypothermia

Body temperature is likely to fall progressively in proportion to the duration of anaesthesia and may result in widespread detrimental effects, for example:

•

Central nervous system dysfunction

•

Slowed drug metabolism, potentiating or prolonging sedative and anaesthetic effects.

Maximizing patient safety prior to sedation and anaesthesia

The fundamental goal is to ensure adequate oxygen delivery to the vital organs.

•

By ensuring vital organ perfusion

–

Correct hypovolaemia (± correct dehydration)

–

Correct malignant or premalignant dysrhythmia

•

By ensuring adequate blood oxygenation

–

Restore blood oxygen-carrying capacity (correct packed cell volume/haemoglobin content)

–

Improve ventilation (e.g. drain pleural fluid, relieve pneumothorax, treat pulmonary oedema)

•

In addition

–

Reduce intracranial pressure if suspected to be elevated

–

Treat acute renal failure, improve urine output in oliguria/anuria, correct azotaemia

–

Correct any clinically significant electrolyte abnormality

Is general anaesthesia necessary?

Depending on the intended investigation or procedure, important questions to consider may be:

•

Can general anaesthesia be avoided while still providing sufficient restraint and insensibility to pain to accomplish the task?

•

Will appropriate analgesia, with or without additional sedation, be sufficiently effective?

•

Could local anaesthesia be utilized in combination with sedation to perform a painful procedure?

•

Or in fact, is general anaesthesia the safest option?

Maximizing patient safety during general anaesthesia

1

Select the most appropriate induction method.

2

Establish good venous access.

3

Do anything you can do without anaesthesia beforehand to minimize anaesthetic time (e.g. pre-clip surgical site).

4

Have all equipment and drugs well prepared (anticipate problems) (

Table 39.3).

5

Preoxygenate via a facemask or flow-by oxygen until ready to intubate.

6

Adopt a calm, quiet approach – relaxing the patient minimizes the dose of anaesthetic required.

7

Take preinduction readings of vital parameters.

8

Attach the required monitoring equipment pre-induction if the patient allows it.

9

Intravenous fluids. Unless the patient’s condition contraindicates it, run isotonic crystalloid fluids at surgical rates (typically 10 ml/kg/hr) as induction commences to offset any potential drop in blood pressure. The type and rate of fluids employed subsequently under anaesthesia in general will be based on that already instituted for stabilization (see

Ch. 4). To what extent these rates are modified for anaesthesia depends on:

(a)

Cardiovascular status at induction

(b)

Packed cell volume, albumin and electrolyte levels

(c)

Expected on-going pathological fluid losses (bleeding, body cavity effusions or gut sequestration)

(d)

Intraoperative blood loss.

10

Calculate the approximate expected dose of anaesthetic agent required – be conservative. Consider using an intravenous sedative pre-induction to minimize the intravenous anaesthetic dose (e.g. diazepam). Dose in increments until the desired effect is reached (usually to allow smooth intubation), allowing plenty of time between doses if the patient is cardiovascularly unstable. More rapid administration may be justified if patent airway or intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) is a priority.

11

Ensure smooth intubation. Use local anaesthetic spray in cats in a timely fashion and allow it time to work.

12

Perform an airway, breathing, circulation (ABC) check immediately on intubation and be prepared to implement IPPV:

(a)

Airway = check correct intubation and secure the tube in place

(b)

Breathing = confirm breathing through tube (chest movement produces bag movement) or give a breath if no breath observed (bag movement produces chest movement)

(c)

Circulation = check pulse.

13

Use a balanced anaesthetic technique for the maintenance of anaesthesia: use nitrous oxide in the gas mixture if it is safe to do so, timely opioid analgesia bolus or constant rate infusion (local anaesthetic techniques, muscle relaxants if familiar with their use). Minimize anaesthetic concentrations at all times.

Table 39.3 Being prepared for anaesthesia of critical patients

| Anaesthetic aspect |

Equipment |

| Intubation |

Range of ET tubes – include several much smaller tubes where potential for unexpectedly narrow airway exists (e.g. upper airway obstruction) Local anaesthetic spray for cats |

| Complications of intubation |

Alternative narrow endotracheal oxygen delivery device: long narrow bore tube such as urinary catheter which can be adapted to connect to oxygen supply ET tube stylets/wire to act as guide and thread tube over in event of partial obstruction of nasopharynx Emergency tracheotomy kit |

| Oxygen administration and ventilation |

Appropriate breathing circuit: if continuous IPPV anticipated, use T-piece for <10 kg, use Bain or Circle for >10 kg |

| Monitoring |

Pulse oximeter, ECG, blood pressure monitor, capnograph, thermometer or temperature probe, glucometer |

| Intravenous fluids |

Include those that might be required later or in event of patient deterioration: crystalloids, colloids, Oxyglobin ®, appropriate blood products as indicated and as available Fluid administration equipment, preferably including infusion pumps |

| Temperature control |

Preventing heat loss: blanket, bubble wrap, heat and moisture exchanger on circuit (Thermovent ®), warm ambient temperature of room Heat sources if appropriate: warm air blanket, warm water bed, ‘hot hands’ |

| Emergency drugs |

Atropine, adrenaline (epinephrine), lidocaine (only indicated if there is continuous ECG monitoring to characterize nature of cardiac dysrhythmia) |

ECG, electrocardiograph; ET, endotracheal; IPPV, intermittent positive pressure ventilation.

Clinical Tip

•

Because anaesthetic drugs cause cardiorespiratory depression in a dose-dependent manner, it is important to try to minimize the dose used. Anaesthetic administration can be minimized by the rational use of additional drugs which contribute to the anaesthetic state, without producing significant cardiorespiratory effects of their own.

•

The anaesthetic state consists of unconsciousness, analgesia and muscle relaxation. The provision of effective analgesia using opioids and, where possible, local anaesthesia in particular can go a long way to reducing anaesthetic dosage.

14

Control temperature (see

Table 39.3). Rebreathing circuits (circle systems) recycle exhaled breath (minus carbon dioxide) and so help to retain warmth and moisture.

15

Monitor appropriately (see below).

16

Ensure that intensive patient monitoring and support continue through the recovery as well.

Patient monitoring during general anaesthesia

Under anaesthesia, the following questions should constantly be asked:

•

Is there adequate circulation and perfusion?

•

Is the patient adequately oxygenated?

•

Is there adequate ventilation to get rid of carbon dioxide from the body?

•

Is there adequate kidney function to ensure other waste products are removed from the body?

The emphasis should be on continuous monitoring of physical examination parameters, ideally by a member of staff dedicated to this purpose:

•

Pulse rate and quality – ideally access to a central (femoral) and peripheral (distal limb, tongue) pulse. This should be supplemented by heart auscultation by stethoscope or oesophageal stethoscope

•

Respiratory rate and quality – observation of chest and reservoir bag movement

•

Capillary refill time and mucous membrane colour

•

Core temperature and the temperature of the extremities

•

Eye position, palpebral reflex, pupil size, jaw tone.

Clinical Tip

•

Recording of measurements every 5 minutes is to be encouraged, primarily to focus the mind and alert the recorder to important trends in vital parameters over time.

Clinical Tip

Monitoring such as pulse oximetry, blood pressure measurement, capnography and electrocardiography should be used as available. There are two golden rules with monitoring:

1

When in doubt, always look at the patient and rely on your own senses.

2

Do not rely on what just one monitor is telling you; always consider it in the context of all the other information you have available – from the patient, from other monitors, and from what is being done to the patient (surgery, drugs, fluids, anaesthetic, etc.).