19 Pallor and approach to anaemia

Pallor

Pallor of the mucous membranes is a common finding during major body system examination of dogs presenting as emergency patients. Pallor is harder to detect in cats but many of the points that follow are equally applicable. Pallor is most commonly the result of anaemia or vasoconstriction secondary to hypovolaemia and both processes may be present within the same patient. In addition, hypoperfusion due to cardiogenic or obstructive shock may also cause mucous membranes to appear pale, as can thermoregulatory vasoconstriction in hypothermia.

In many cases it will be possible on the basis of historical and physical examination findings to determine whether anaemia or hypovolaemia may be present. Concomitant hypovolaemia and anaemia are typically seen where anaemia is secondary to acute blood loss and the degree of pallor may be more severe than would otherwise be expected for the degree of hypovolaemia. It is important to remember that the packed cell volume may be normal for several hours following acute blood loss in dogs (but serum total solids should be low) (see Ch. 3).

Euvolaemic dogs with anaemia of sufficient severity are likely to show compensatory cardiovascular changes that may be distinguishable from hypovolaemia. In particular, capillary refill time (if detectable) is usually normal in euvolaemic anaemia. Euvolaemic dogs with acute anaemia may be distinguishable from chronically anaemic dogs as the former tend to be depressed or moribund while the latter are often remarkably bright (until a critical end-point is reached), having had time to adapt to the anaemia. In some cases anaemia is not identified until packed cell volume/haematocrit is measured.

Anaemia

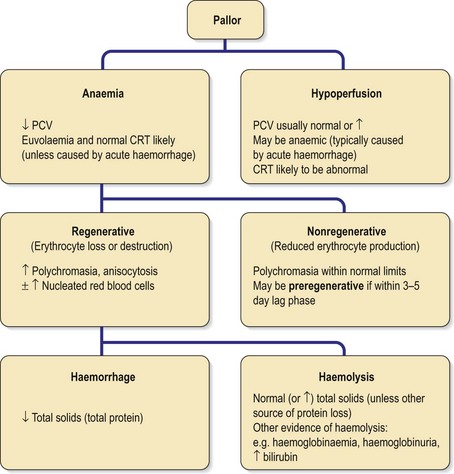

A rational approach to the investigation of anaemia starts with classification of the anaemia as regenerative (due to red blood cell loss or destruction) or nonregenerative (due to reduced red blood cell production). In the emergency setting, this is done on the basis of peripheral blood smear examination, with regenerative anaemia being manifested as polychromasia, anisocytosis and a possible increase in nucleated red blood cells (see Figures 3.3 and 3.5). Regenerative anaemia occurs as a result of haemolysis or haemorrhage, and additional findings are used to determine which of these two processes is the likely cause (Figure 19.1).

Figure 19.1 Algorithm for pallor and approach to anaemia. CRT, capillary refill time; PCV, packed cell volume.

Clinical Tip

Regenerative anaemia

Causes of regenerative anaemia are listed in Box 19.1.

BOX 19.1 Causes of regenerative anaemia

Haemorrhage

Haemolysis

Dogs

Case example 1

Presenting Signs and Case History

An 8-year-old female neutered cross-bred dog presented for acute collapse. The owners reported a several week history of intermittent self-limiting lethargy.

Major body system examination

Major body system examination revealed the dog to be recumbent and depressed. Heart rate was 150 beats per minute with no murmur or gallop sound audible. Femoral pulse was (inappropriately) normal and no pulse deficits were detected; however, dorsal pedal pulse was only just palpable. Mucous membranes were markedly pale; capillary refill could only just be detected and took approximately 2 seconds. Respiratory rate was 36 breaths per minute with appropriate effort and auscultation. The abdomen was tense on palpation with a detectable fluid thrill. Rectal temperature was 38.5°C.

Assessment

The cardiovascular assessment of this patient was consistent with moderate hypovolaemia in which mucous membranes are expected to appear inappropriately normal (i.e. pink) or perhaps mildly pale. The marked pallor in this case was therefore inconsistent with uncomplicated hypovolaemia and anaemia was therefore also suspected.

Case management

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and an emergency database performed that showed a manual packed cell volume (PCV) of 25% (normal range 37–55%). Serum total solids (TS) were also reduced (34 g/l, normal range 49–71 g/l) and anaemia secondary to blood loss was therefore suspected. Peripheral blood smear examination demonstrated a regenerative anaemia (moderate polychromasia and anisocytosis).

The dog was subsequently found to have a haemoabdomen that was the result of splenic rupture secondary to haemangiosarcoma (see Ch. 29).

Case example 2

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 6-year-old male neutered Cocker Spaniel presented with a 2-day history of progressive lethargy and inappetence. The dog had vomited twice the day before presentation.

Major body system examination

Major body system examination revealed the dog to be recumbent and depressed. Heart rate was 110 beats per minute with no murmur or gallop sound audible. Both femoral and dorsal pedal pulses were readily palpable and hyperdynamic with no deficits. Mucous membranes were pale and jaundiced with a normal capillary refill time. The rest of the major body system examination was unremarkable.

Case management

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and an emergency database performed that showed PCV 18% (37–55%) with normal serum TS 66 g/l (49–71 g/l) and icteric serum. Blood smear examination revealed a strongly regenerative anaemia (marked polychromasia, moderate anisocytosis) with moderate spherocytosis (see Figure 3.4) and in-saline agglutination testing was strongly positive. A diagnosis of immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia (IMHA) and prehepatic jaundice was made.

Nonregenerative anaemia

Causes of nonregenerative anaemia are listed in Box 19.2.

Case example 3

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 6-year-old female neutered Boxer dog presented for self-limiting ataxia following a period of short exercise. This had occurred on two previous occasions in the preceding 2 weeks. The owners also reported progressive exercise intolerance over several weeks and that pallor of the mucous membranes had been present for some time.

Major body system examination

Major body system examination revealed the dog to be ambulatory and bright. Heart rate was 140 beats per minute and a grade II/VI systolic murmur was audible. Both femoral and dorsal pedal pulses were readily palpable and hyperdynamic with no deficits. Mucous membranes were pale with a normal capillary refill time. The rest of the major body system examination was unremarkable.

Case management

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and an emergency database performed that showed PCV 16% (37–55%), serum TS 60 g/l (49–71 g/l) and nonregenerative anaemia on blood smear examination. Subsequently a diagnosis of pure red cell aplasia was made on bone marrow sampling.