29 The acute abdomen

Differential diagnoses of acute abdomen are discussed in Chapter 8 and some of the most common disorders are discussed in greater detail here using case examples.

Septic (Bacterial) Peritonitis

Theory refresher

Free peritoneal fluid and gas

Abdominal palpation is an insensitive means of detecting free peritoneal fluid. Ultrasonography is extremely useful in this respect even in relatively inexperienced hands. Small amounts of free peritoneal fluid are most readily detected at the apex of the urinary bladder and between liver lobes. If ultrasonography is not available, loss of serosal detail may be identified radiographically.

Abdominal radiography is useful for identifying free peritoneal gas (often most readily seen between the liver and diaphragm) as well as diagnosing intestinal foreign body material and obstruction. Radiography will be less useful in this respect if a large volume of free peritoneal fluid is present due to increased loss of contrast.

In animals without a history of recent (last 3–4 weeks) laparotomy or open system abdominocentesis, free peritoneal gas suggests rupture of a hollow viscus and is an indication for emergency surgical exploration. This also applies to animals that have suffered penetrating injuries as free peritoneal gas implies full thickness penetration into the abdomen.

Cytology of peritoneal fluid

Depending on the severity of peritoneal contamination, direct smears of peritoneal effusion may be less rewarding than smears made after centrifugation with respect to identifying bacteria. However, centrifugation may alter cell morphology, preventing accurate assessment. The author therefore routinely examines direct smears first and then smears made following centrifugation if appropriate – typically if no bacteria are identified on direct smears but there is a high index of suspicion for bacterial peritonitis or neutrophils appear degenerate. The exception to this approach is for samples obtained via diagnostic peritoneal lavage which are likely to contain only scant cellular and other material and must be centrifuged prior to cytological analysis.

The identification of even one intracellular (phagocytosed) bacterium is considered diagnostic for septic peritonitis which is a surgical emergency. Extracellular bacteria are suggestive of this condition but the possibility of contamination cannot be excluded and in such cases other considerations must be taken into account in making a diagnosis.

Case example 1 – surgical gastrointestinal wound dehiscence

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 1-year-old male entire Staffordshire bull terrier presented as an emergency 3 days after gastrotomy and enterotomy for removal of a linear foreign body. The dog had initially recovered well from surgery and had been discharged from the primary care clinic after 48 hours. However, he had become progressively more depressed and lethargic in the 12 hours prior to emergency presentation.

Clinical Tip

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was ambulatory but depressed. Cardiovascular examination was unremarkable with no evidence of hypovolaemia. Respiratory examination was unremarkable and rectal temperature was within normal limits. The dog’s abdomen was rigid and diffusely painful on palpation but a fluid thrill was not detected. Digital examination per rectum was unremarkable.

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood collected via the catheter for an emergency database. This was unremarkable except for the presence of a subjective neutrophilia with mild to moderate toxic change (see Ch. 3).

Case management

Morphine (0.3 mg/kg slow i.v.) was administered for analgesia. An abdominal ultrasound was performed using a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) protocol. This involved scanning the dog in lateral recumbency and obtaining both transverse and longitudinal views at each of four sites – just caudal to the xiphoid process (last sternebra), on the midline over the urinary bladder, and at the right and left flank regions. Despite this thorough evaluation, no peritoneal fluid could be identified. However, given the dog’s history and clinical signs, there was a very high index of suspicion for bacterial peritonitis secondary to surgical gastrointestinal wound dehiscence and a diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) was therefore performed (see p. 294).

The peritoneal fluid subsequently obtained was centrifuged and smears made from the sediment. Cytology demonstrated degenerate neutrophils with occasional intracellular rod-shaped bacteria and a diagnosis of bacterial peritonitis was therefore confirmed. A peritoneal fluid glucose concentration of less than 2.8 mmol/l is reported to have high specificity for bacterial peritonitis and was found to be 2.0 mmol/l in this case.

Intravenous antibiosis using amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (20 mg/kg) was commenced and an exploratory laparotomy performed. This revealed dehiscence with leakage from the enterotomy incision that was debrided and repaired. Antibiosis was continued postoperatively, first intravenously and then per os, and culture of the fluid obtained from the abdomen following DPL revealed a scant growth of Escherichia coli that was sensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. The dog made an uneventful recovery from the surgery and was discharged after 5 days to complete a 2-week course of antibiotics.

Clinical Tip

Case example 2 – uterine rupture

Presenting Signs and Case History

An 11-year-old female entire cross-bred dog presented with a 3-day history of intermittent vomiting and progressive lethargy and inappetence. She had also been panting excessively on the day of presentation. Her last season had finished apparently uneventfully 3 weeks earlier and no vulval discharge had been noted by her owners prior to presentation.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was obtunded. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 200 beats per minute with very weak femoral pulses and absent dorsal pedal pulses. Mucous membranes were hyperaemic with a rapid capillary refill time. Respiratory examination revealed tachypnoea with appropriate lung auscultation. The abdomen was tense and painful on palpation but a more thorough examination could not be performed due to the dog’s recumbency. Marked pyrexia (rectal temperature 40.4°C) was identified. The vulva was swollen but no discharge was detected. A brown-tinged serous mammary discharge was present but the mammary glands were not enlarged or obviously inflamed.

Assessment

The dog was assessed as being in moderate to severe mal-distributive shock that was most likely secondary to acute abdomen. Given the dog’s signalment and history, there was a high index of suspicion for pyometra. The cardiovascular picture in this case was highly suggestive of sepsis as the cause of the mal-distributive shock that raised the index of suspicion for septic peritonitis secondary to uterine rupture following closed-cervix pyometra.

Clinical Tip

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood collected via the catheter for an emergency database. This revealed marked haemoconcentration (manual packed cell volume (PCV) 72%, reference range 37–55%; plasma total solids (TS) 95 g/l, reference range 49–71 g/l) and a subjective degenerate neutrophilic left shift.

Case management

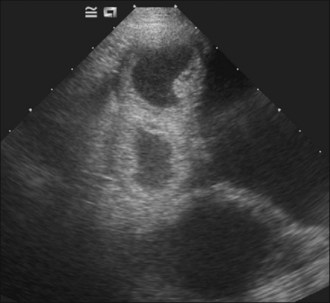

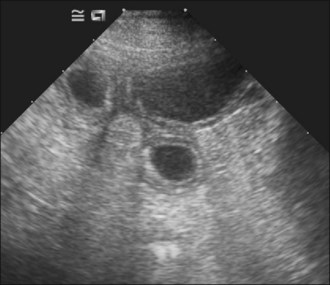

Aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation with an isotonic crystalloid solution was commenced and morphine (0.3 mg/kg slow i.v.) administered. Abdominal ultrasound revealed the presence of enlarged uterine horns distended with hypoechoic fluid consistent with pyometra and peritoneal fluid was detected (Figure 29.1).

Figure 29.1 Ultrasound image of pyometra showing enlarged uterine horns distended with hypoechoic fluid; the urinary bladder is also visible.

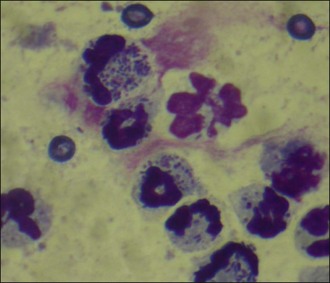

Abdominocentesis (see p. 293) was performed and a sample of the fluid retrieved. Cytology demonstrated large numbers of degenerate neutrophils with intracellular bacteria as well as a considerable number of extracellular bacteria (Figure 29.2). A diagnosis of bacterial peritonitis secondary to uterine rupture was made. Regrettably, due to financial constraints, the dog was euthanased.

Haemoabdomen

Causes of haemoabdomen are listed in Box 29.1.

Theory refresher

Canine haemangiosarcoma

Canine haemangiosarcoma is most commonly diagnosed in German shepherd dogs followed by golden retrievers. Other large breed dogs, such as Labrador retrievers and Boxers, are also over represented. The spleen is the most common site of origin but right atrial, pericardial and hepatic canine haemangiosarcoma are also reported relatively frequently. Any site in the body that contains vascular endothelium can theoretically be affected.

Haemangiosarcoma is presumed to have metastasized at the time of diagnosis in the vast majority of cases, regardless of whether or not metastases are detected by currently available imaging modalities. The prognosis is very poor, with survival times in the region of 2–4 months reported for splenic haemangiosarcoma following splenectomy alone; survival may in some cases be improved modestly by additional chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

In dogs presenting with haemoabdomen presumed to be secondary to rupture of a splenic lesion, splenectomy will be palliative and remove the risk of recurrent haemorrhage in the short term. It should be remembered that the nature (benign or malignant) of hepatic nodules that may be identified in such cases cannot be determined based on ultrasonographic appearance and surgical intervention therefore remains a rational choice. Palliative surgery is unlikely to be an option in primary hepatic haemangiosarcoma.

Abdominal counterpressure bandage

The purpose of an abdominal bandage is to apply external pressure that will increase intra-abdominal pressure and thereby tamponade bleeding. Realistically, intra-abdominal pressure is only likely to be increased sufficiently to exceed venous pressure and reduce venous haemorrhage. Therefore, excessively tight bandages do not offer any significant advantage and are likely to be associated with greater complications.

Traditionally a soft material has been used as the primary layer of an abdominal pressure bandage with an elastic material applied on top. In the author’s experience, however, these bandages are more likely to slip and the author prefers to use an elastic adhesive primary layer despite the inherent difficulties in subsequent removal. The bandage should be placed starting caudally, approximately at the level of the pubis, and moving in a cranial direction up to the xiphoid, stopping before the caudal rib margin.

The bandage should be removed once the patient has remained stable for a reasonable period. Removal should commence at the cranial end (i.e. in the opposite direction to how the bandage was placed) and should be staggered by cutting a small section every 30–60 minutes over a period of several hours. The patient should be monitored closely for signs of deterioration during removal of counterpressure.

Abdominal bandages should not be used in animals with respiratory compromise or those suffering from diaphragmatic rupture.

Case example 3

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 10-year-old male neutered German shepherd dog presented with a 7-day history of intermittent lethargy and exercise intolerance. The dog had been found collapsed and tachypnoeic with a distended abdomen on the day of presentation.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was obtunded. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 180 beats per minute with no murmur detected; femoral and dorsal pedal pulses were absent. Mucous membranes were very pale with a prolonged capillary refill time. Respiratory examination revealed tachypnoea with appropriate lung auscultation and both marked distension and recumbency precluded reliable abdominal palpation.

Assessment

The dog was assessed as being in severe hypovolaemic shock that was most likely due to acute abdomen. Given the dog’s signalment and history, there was a high index of suspicion for haemoabdomen secondary to rupture of an intra-abdominal haemangiosarcoma lesion. The fact that some colour remained in the mucous membranes despite the severity of hypovolaemia suggested that severe anaemia was not present.

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood collected via the catheter for an emergency database. This revealed mild anaemia (PCV 31%, reference range 37–55%) with a more significant decrease in TS (40 g/l, reference range 49–71 g/l), findings that were compatible with acute haemorrhage. Peripheral blood smear examination showed the anaemia to be regenerative (moderate polychromasia, moderate anisocytosis). As a regenerative response often takes a minimum of 3 days to be detectable clinically in dogs, this suggested one or more prior episodes of haemorrhage in the days preceding presentation. Platelet count was considered adequate and a neutrophilia with left shift suspected.

Case management

Aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation with an isotonic crystalloid solution was commenced (60 ml/kg bolus via pressure infusor). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed the presence of a large volume of echogenic peritoneal fluid. Abdominocentesis (see p. 293) was performed and the non-clotting haemorrhagic fluid was found to have a PCV of 30%; cytology of the fluid revealed red blood cells, occasional erythrophagocytosis, no platelets and no evidence of sepsis. An abdominal counterpressure bandage was applied and fluid therapy discontinued as soon as the dog was assessed as being adequately perfused. The dog remained stable subsequently and the abdominal bandage was removed gradually over several hours.

The following day the dog was referred for further management. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a cavitary splenic lesion and although the liver was hyperechoic, no focal lesions were identified. Thoracic radiography was performed under general anaesthesia and found to be unremarkable. Complete splenectomy and a liver biopsy were then carried out, from which the dog made an uneventful recovery. Histopathology confirmed the suspicion of splenic haemangiosarcoma although no neoplastic cells were identified in the sample of liver submitted.

Clinical Tip

Uroabdomen

Causes

Trauma is the most common cause of uroabdomen:

Neoplasia and prolonged urinary tract obstruction are less common causes.

Diagnosis

Animals with uroabdomen typically have severe azotaemia, and variable hyperkalaemia may be present. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine and potassium concentrations in the peritoneal fluid are typically higher than plasma concentrations measured at the same time. Creatinine and potassium in peritoneal effusion equilibrate more slowly with the intravascular space and are therefore considered more reliable than BUN for detecting uroabdomen. Blood and peritoneal fluid samples should be collected within a few minutes of one another and an intravenous fluid bolus should not be administered in the interim if the peritoneal fluid is collected first (dilution of plasma BUN, creatinine and potassium by the bolus may create concentration gradients consistent with uroabdomen and lead to misdiagnosis).

Positive contrast radiography of the urinary system (intravenous urography, retrograde urethrocystography) is helpful in determining the site of urinary tract rupture.

Clinical Tip

Bile Peritonitis

Causes

Bile peritonitis occurs due to leakage from or rupture of the gallbladder and/or biliary tract. This may result from:

Diagnosis

Clinical jaundice and hyperbilirubinaemia may be identified in animals with bile peritonitis, depending on the cause, along with varying degrees of cardiovascular compromise. Marked elevations in liver enzymes may also be seen.

Peritoneal fluid may be greenish in appearance and clusters of golden refractile pigment are identified. The bilirubin concentration of the peritoneal fluid is considerably higher than the plasma bilirubin concentration.

Gastric Dilatation/Volvulus Syndrome (GDV)

Theory refresher

Risk factors

A large number of risk factors have been suggested for acute gastric dilatation/volvulus syndrome (GDV). Some are supported by sound clinical evidence; others are more controversial or anecdotal. The cause of this condition, however, remains unknown and is likely to be multifactorial. Suggested risk factors are listed in Box 29.2.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GDV is multifactorial and involves the cardiovascular and gastrointestinal systems in particular. Respiratory compromise may also be severe. Significant pathophysiological mechanisms are as follows.

Radiography

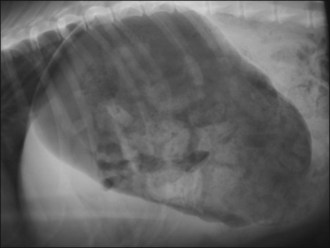

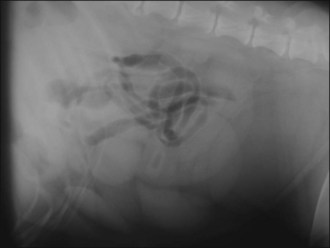

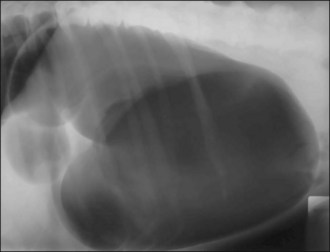

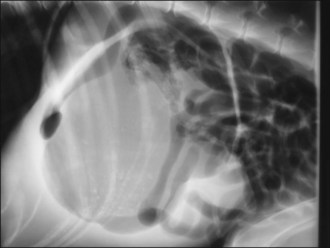

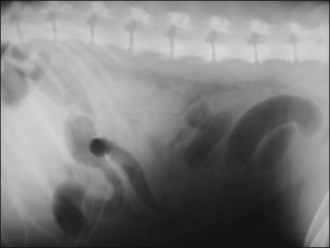

Acute GDV can usually be diagnosed on the basis of history, signalment and physical examination; radiography is generally not required. However, radiography may allow differentiation of gastric dilatation alone from gastric dilatation with volvulus. Radiography should not be performed until after fluid therapy and analgesia have been commenced and only if the patient is compliant as is usually the case. Radiography may be performed during the initial fluid resuscitation but should not delay gastric decompression. A single radiograph with the patient in right lateral recumbency is all that is typically required. Examples of radiographic findings are shown in Figures 29.3-29.6.

Figure 29.4 Right lateral abdominal radiograph showing gastric dilatation with volvulus with the Popeye arm (double bubble, reverse C) configuration.

Figure 29.5 Right lateral abdominal radiograph showing gastric dilatation with volvulus; compartmentalization by a soft tissue fold is present. Gas-filled intestines are often identified as in this example.

Figure 29.6 Right lateral abdominal radiograph showing gastric dilatation with volvulus and perforation of the stomach wall. Free air is visible within the abdominal cavity.

Thoracic radiography may be indicated in dogs suspected of having cardiac disease or inappropriate respiratory compromise (e.g. due to aspiration), or to rule out co-existing disease (e.g. neoplasm) in older animals.

Intra-operative considerations

Patients require close monitoring of vital signs during anaesthesia, and blood pressure and electrocardiogram monitoring is recommended. Cardiovascular depression can be minimized by careful dosing of induction and maintenance agents to effect. A crystalloid rate of 10–40 ml/kg/hr is advisable and colloids may be required. If orogastric intubation is performed during surgery, the risk of aspiration of oesophageal reflux means that use of a cuffed endotracheal tube is mandatory, and great care must be taken at extubation.

Postoperative considerations

Fluid therapy is continued postoperatively and adjusted on the basis of regular assessment. Serum potassium levels should be monitored and supplemented as necessary, in particular if lidocaine administration is required. Analgesia must be continued using a dynamic approach and the usual postoperative considerations such as wound management, appropriate bedding and bladder management should not be forgotten. The time at which food and water are provided will depend to an extent on the nature of the surgical intervention in each case.

Electrocardiogram abnormality has been reported to occur in approximately 40% of dogs with acute gastric dilatation/volvulus. Ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) and ventricular tachycardia (VT) are the most common, both pre- and postoperatively (see Figures 12.4 and 12.5). In general, ventricular dysrhythmias arising secondary to another condition such as acute GDV only warrant antidysrhythmic therapy if they are considered to be compromising the patient’s perfusion based on physical examination and blood pressure measurement if available. In addition, VT should be treated if it occurs at rates greater than 180 beats per minute or if R-on-T phenomenon is identified (see Ch. 12).

Is surgery always necessary?

The aims of surgical intervention in dogs with acute GDV are:

In animals in which gastric volvulus persists despite decompression or in which the presence of volvulus cannot be excluded, surgical intervention is mandatory but should only be performed when the patient is haemodynamically stable.

As described above, there are compelling reasons for surgical intervention in patients presenting with gastric dilatation alone. There are cases, however, in which owners may not be willing to provide consent, for example due to financial constraints or because of the age of the pet. Such cases can be successfully managed conservatively but the owner must be advised of the risks associated with this approach, particularly a lack of information regarding the viability of the stomach and spleen, and the possibility of recurrence both overnight and subsequently.

Case example 4

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 10-year-old male neutered weimaraner presented with a 2-hour history of nonproductive retching and drooling that began shortly after eating his evening meal. He had become progressively more lethargic and the owner had noticed abdominal distension.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was ambulatory but depressed and drooling. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 160 beats per minute with absent dorsal pedal pulses and weak femoral pulses. Mucous membranes were pink with a capillary refill time of approximately 2 seconds. The dog was panting but lung sounds were appropriate when this was temporarily stopped. Abdominal palpation revealed tympany cranially and was uncomfortable. Rectal temperature was within normal limits.

Emergency database

A large bore (16 gauge) intravenous catheter was placed into each cephalic vein and blood collected via one of the catheters for an emergency database. This was largely unremarkable except for hyperlactataemia (4.0 mmol/l, reference range 0.6–2.5 mmol/l).

Case management

Aggressive intravenous fluid therapy was commenced with 1 l of Hartmann’s solution being administered as a bolus via each cephalic catheter using pressure infusors (see Figure 4.1). Electrocardiography demonstrated sinus tachycardia with occasional ventricular premature complexes (see Figure 12.4). As radiography facilities were readily accessible, a right lateral abdominal radiograph was taken during initial fluid resuscitation that confirmed the presence of gastric dilatation with volvulus.

The dog’s cardiovascular status improved noticeably and fluid therapy was continued but less aggressively. Sedation was administered using methadone (0.2 mg/kg i.v.) and diazepam (0.5 mg/kg i.v.) and orogastric decompression performed using a stomach tube (see p. 294). This resulted in a noticeable reduction in abdominal distension and further improvement in cardiovascular status.

Clinical Tip

In the majority of cases fluid resuscitation can be achieved through the use of an isotonic crystalloid alone (e.g. Hartmann’s solution). In some cases, the additional use of small volume resuscitation fluids (colloids, hypertonic saline) may be applicable if available. Examples are:

Clinical Tip

The combination of methadone and diazepam already administered acted as premedication to reduce the dose of cardiovascular depressant drugs subsequently required for general anaesthesia. Exploratory laparotomy was performed that confirmed 180° clockwise volvulus of the stomach. This was reduced manually after further decompression and emptying of the stomach contents. Both the gastric wall and spleen appeared to be viable. An incisional gastropexy was performed between the pyloric antrum and the right abdominal wall. The abdomen was lavaged thoroughly prior to closure. Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiosis (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 20 mg/kg i.v) was commenced preoperatively and repeated during surgery; however, it was stopped thereafter based on the relatively benign findings at laparotomy.

Clinical Tip

The dog was monitored closely following surgery, in particular for clinically significant cardiac dysrhythmia, but made an uneventful recovery. Water was introduced as soon as the dog was fully recovered from general anaesthesia and food was offered 12 hours postoperatively.

Small Intestinal Foreign Body

Case example 5

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 2-year-old female neutered cross-bred dog presented with a 24-hour history of vomiting, depression and anorexia. The dog was still drinking and no other signs were reported. The dog was known to be a notorious scavenger although the owner was unaware of a specific episode of dietary indiscretion prior to the onset of signs. The dog had had an enterotomy 1 year previously for removal of a linear foreign body.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was ambulatory but depressed. Heart rate was 140 beats per minute but the dog was assessed as euvolaemic and not obviously clinically dehydrated. Respiratory examination revealed tachypnoea but auscultation was unremarkable. Abdominal palpation revealed moderate discomfort but this could not be localized. The dog was mildly pyrexic (rectal temperature 39.3°C).

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood collected for an emergency database that was suggestive of dehydration (high-normal PCV and TS) but was otherwise unremarkable.

Case management

Methadone (0.2 mg/kg i.v.) was administered and plain abdominal radiography performed. This revealed focal areas of gaseous small intestinal dilatation consistent with possible mechanical obstruction (Figure 29.7).

Figure 29.7 Right lateral abdominal radiograph showing focal areas of gaseous small intestinal dilatation consistent with obstruction.

The options of contrast radiography or referral for ultrasonography were discussed; however, given the dog’s history of scavenging and the highly suggestive plain radiographs, it was decided to perform an exploratory laparotomy. A cloth intestinal foreign body was subsequently removed via enterotomy. The dog recovered uneventfully from surgery.

Clinical Tip

Intussusception

Theory refresher

Intussusception may involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract but a significant proportion of published cases in dogs and cats are enterocolic and in particular ileocolic. Affected animals are often young, especially less than 1 year of age, and a variety of intestinal disorders (e.g. gastroenteritis/enteritis, parasitic infestation, mass lesions, foreign bodies) may potentially predispose to intussusception. Acute enteritis or gastroenteritis has been shown to be the most likely predisposing factor in young dogs. However, the majority of cases in dogs and cats are thought to be idiopathic.

Survey abdominal radiographic findings may be suspicious for intussusception and positive contrast studies are often diagnostic. However, in experienced hands abdominal ultrasonography is the preferred method of diagnosis. A target-like mass consisting of multiple hyperechoic and hypoechoic concentric rings in transverse section (Figure 29.8), or the appearance of multiple hyperechoic and hypoechoic parallel lines in longitudinal section, is considered virtually diagnostic of an intussusception.

Case example 6

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 13-year-old female neutered domestic short hair cat presented with a 2-day history of anorexia, progressive depression and a small amount of diarrhoea. No vomiting had been noted but the cat had retched once and had been drinking more than normal over the last 48 hours. The cat’s diet had been changed 2 weeks prior to the onset of signs. A small intestinal intussusception had been manually reduced 1 year previously.

Major body system examination

On presentation the cat was quiet but alert and responsive. Cardiovascular examination revealed a grade IV/VI holosystolic heart murmur but was otherwise unremarkable. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. Abdominal palpation revealed a nonpainful sausage-shaped mass approximately 5 cm long in the ventral abdomen suggestive of an intussusception. Rectal temperature was within normal limits.

Case management

An intravenous catheter was placed into a cephalic vein and blood collected for an emergency database that was unremarkable except for mild hypokalaemia. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a small intestinal intussusception (see Figure 29.8) and exploratory laparotomy was performed.

The intussusception was manually reduced and enteroplication performed in an attempt to reduce the likelihood of recurrence. Multiple full thickness small intestinal biopsies and several mesenteric lymph node biopsies were taken and the abdomen thoroughly lavaged prior to closure. The cat made an uneventful recovery from surgery. Histopathology revealed moderate lymphoplasmacytic–eosinophilic enteritis and the lymph nodes were hyperplastic with moderate eosinophilic infiltration.

The heart murmur in this case warranted caution with intravenous fluid therapy and the cat was therefore kept on Hartmann’s solution at a conservative 3 ml/kg/hr while under general anaesthesia. Vital parameters, including systolic blood pressure, were monitored closely throughout and the cat remained normotensive.

Severe Acute Pancreatitis

Theory refresher

Diagnosis

Detection of elevated serum amylase and lipase activities show relatively poor sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing acute pancreatitis. Hyper-amylasaemia may also for example be seen in pancreatic neoplasia, intestinal disorders and in association with renal insufficiency/azotaemia. Hyper-lipasaemia may also for example be seen in pancreatic neoplasia, liver disease (especially neoplasia) and in association with renal insufficiency/azotaemia. Consideration must be given to the severity of elevation during interpretation. It is noteworthy that hypovolaemia and/or dehydration that may be a feature of some of the differential diagnoses of acute pancreatitis (e.g. intestinal obstruction, haemorrhagic gastroenteritis) can cause elevations in serum amylase and lipase activities that may prompt misdiagnosis of pancreatitis. Measurement of canine pancreatic lipase (cPLI) is now the preferred diagnostic test.

Abdominal radiography has relatively poor sensitivity and specificity for acute pancreatitis but should help to exclude some of the differential diagnoses (e.g. intestinal obstruction). Signs consistent with acute pancreatitis in dogs include loss of serosal detail and increased density in the right cranial abdomen, displacement of the descending duodenum to the right with widening of the angle between the proximal duodenum and the pylorus, and caudal displacement of the transverse colon. Ultrasonographic changes are usually present in severe acute pancreatitis but this modality requires considerable expertise.

Analgesia in acute pancreatitis

Opioids are the mainstay of analgesia in pancreatitis. Some authors have argued that pethidine is the most appropriate initial choice but this would appear to be based on theoretical considerations adopted from human literature and is unlikely to be of clinical significance in dogs and cats. Pethidine cannot be administered intravenously and has a short duration of action, making it a poor choice for on-going analgesia in pancreatitis. The author therefore prefers to use morphine, given as intravenous boluses titrated to effect initially and then as a constant rate infusion. Following adequate improvement, analgesia is then stepped down to intermittent boluses of buprenorphine. Again, suggested contraindications of using this agent in pancreatitis are more likely to be of theoretical concern rather than of clinical significance.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are generally not used and should definitely not be administered to animals with acute pancreatitis that are cardiovascularly unstable, dehydrated or azotaemic.

Feline pancreatitis

Most cats with severe acute pancreatitis present with vague signs of lethargy, anorexia and dehydration, with vomiting and abdominal pain featuring less commonly than in dogs. Testing of serum feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (fPLI) is available, and concurrent inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and/or cholangitis–cholangiohepatitis are reported relatively frequently in cats (this is the so-called ‘triad disease’ of cats); hence icterus is relatively common in cats with pancreatitis. Serum amylase and lipase activities are of little diagnostic value in feline pancreatitis.

Treatment of feline and canine acute pancreatitis is similar. However, these cats are especially vulnerable to developing potentially fatal hepatic lipidosis. Nutritional support must therefore be emphasized and early feeding tube placement is recommended. Given the inherent difficulties in reliably detecting abdominal pain in animals in general and especially in cats, analgesia is indicated in all cases. Buprenorphine may be a suitable first line agent in this species although its onset of action is likely to be slower than that of the pure opioids. Low plasma ionized calcium concentration may be associated with a worse outcome in cats with acute pancreatitis.

Case example 7

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 9-year-old female neutered Cocker Spaniel presented with a 1-day history of anorexia, restlessness, vomiting and intermittently adopting the praying position. No diarrhoea had been noted. The dog had been seen to scavenge from the rubbish bin several days prior to the onset of signs.

Clinical Tip

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was depressed and recumbent. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 160 beats per minute and absent pedal pulses with weak femoral pulses. Mucous membranes were markedly hyperaemic with a very rapid capillary refill time. Respiratory rate was 80 breaths per minute with a shallow pattern and abdominal palpation was painful cranially. An abdominal fluid thrill could not be detected. The dog was moderately pyrexic (rectal temperature 39.7°C) and had a body condition score of 7/9 (heavy fat cover over ribs, lumbar area and tail base; absent waist).

Assessment

The dog was assessed as being in mal-distributive shock. Given the history and the other physical examination findings of tachypnoea and pyrexia, the dog was likely to be suffering from systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and potentially sepsis (i.e. SIRS secondary to confirmed or highly suspected infection). A primary intra-abdominal process was suspected and there was a high index of suspicion of severe acute pancreatitis given the dog’s signalment.

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood collected for an emergency database that showed mildly lipaemic plasma, hyperlactataemia, and a subjective neutrophilia with left shift. The dog was found to be normocalcaemic. Blood was also submitted in a serum gel tube for measurement of cPLI concentration.

Case management

A 40 ml/kg bolus of Hartmann’s solution was administered to which there was a noticeable but relatively short-lived positive response. Two 5 ml/kg boluses of a synthetic colloid (6% hydroxyethyl starch, Voluven®) were then administered, following which the dog remained stable. The dog was subsequently maintained on a combination of Hartmann’s solution (4 ml/kg/hr) and hydroxyethyl starch (2 ml/kg/hr).

Clinical Tip

Morphine (0.3 mg/kg slow i.v.) was administered for analgesia. The dog was reassessed after a short period and although improved, still showed signs of abdominal discomfort. A further dose of morphine (0.1 mg/kg slow i.v.) was administered and the dog was started on a constant rate infusion of morphine (0.1 mg/kg/hr).

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a significantly enlarged pancreas with a small amount of localized peritoneal effusion. There was hyperechogenicity of the peripancreatic mesentery. This provided further evidence for the suspected diagnosis of acute pancreatitis although an inciting cause was not identified, as is often the case.

The dog was managed intensively with fluid therapy, analgesia and anti-emetic treatment, and in keeping with more recent recommendations, first water and then food (low fat) was offered as soon as vomiting had resolved for 12 hours. The dog was eventually discharged after satisfactory improvement 5 days later. The sample submitted on the day of presentation showed an elevation in serum cPLI concentration (650 µg/l, reference range 0–200 µg/l), confirming inflammatory pancreatic disease.

Canine Parvoviral Gastroenteritis

Theory refresher

Canine parvovirus infection is seen most commonly in dogs under 6 months old but may occur in older animals. Existing passive maternal immunity may impair an effective response to vaccination in very young animals and clinical signs may therefore occur in vaccinated animals. The enteritis and leucopenia syndrome is the most common clinical manifestation and diarrhoea usually follows initial clinical signs by 12–48 hours.

Antimicrobial therapy

It is generally argued that any dog with blood in its faeces is at increased risk of translocation of intestinal bacteria into the bloodstream and therefore requires antibiotic therapy. However, the true clinical significance of this remains to be clearly elucidated. The author only uses antimicrobial therapy in neutropenic dogs and those with pyrexia or evidence of sepsis. A broad-spectrum bactericidal antibiotic is used and given intravenously early on while vomiting and delayed gastric emptying are likely.

Case example 8

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 9-week-old male neutered cross-bred dog presented with a 36-hour history of vomiting and progressive lethargy and inappetence. Haemorrhagic watery diarrhoea had also been noted on the morning of presentation. The puppy had been acquired from a rescue centre 1 week previously and had received the first dose of his primary vaccination course 2 weeks prior to being rehomed.

Major body system examination

On presentation the puppy was recumbent and depressed. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 200 beats per minute and hyperdynamic peripheral pulses. Mucous membranes were mildly hyperaemic with a brisk capillary refill time. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. Abdominal palpation was not obviously uncomfortable but fluid filled intestinal loops were detected. Mild pyrexia was identified (rectal temperature 39.3°C) and moderate dehydration (estimated 8%) was suspected. Body weight was 4.0 kg at presentation.

Case management

Local anaesthetic cream (EMLA® cream 5%, AstraZeneca) was applied to the skin over both cephalic veins in the consultation room and the sites lightly dressed. While waiting for the topical anaesthesia to take effect, a rectal swab was tested for faecal canine parvovirus-2 antigen using an ELISA test kit (SNAP® Parvo Test, Idexx Laboratories) and found to be strongly positive. Barrier nursing and isolation measures were immediately instituted.

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood collected for an emergency database. Manual PCV was 43% and plasma TS 65 g/l. Although these values fall within commonly cited reference ranges for adult dogs, both PCV and TS (considered approximately equivalent to total protein) would be expected to be lower than adult reference ranges in a puppy of this age. These values were therefore considered consistent with dehydration. The rest of the emergency database, including peripheral blood smear examination and blood glucose concentration, was unremarkable.

The puppy was assessed as mildly hypovolaemic on presentation and a bolus (20 ml/kg) of Hartmann’s solution was given initially, after which euvolaemia was restored. Thereafter the puppy was kept on Hartmann’s solution at 13 ml/kg/hr with appropriate potassium supplementation, but perfusion parameters were monitored regularly. This rate was calculated based on the following assumptions:

The puppy was also started on anti-emetic therapy (maropitant 1 mg/kg s.c. q 24 hr) and analgesia (buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg q 6 hr)) and monitored regularly for possible hypoglycaemia. A nasogastric feeding tube was placed and used to aspirate stomach contents intermittently (q 6 hr).

Over the next 24 hours the vomiting persisted but improved significantly; however, the diarrhoea worsened considerably. An emergency database was repeated that showed a marked decrease in TS to 35 g/l and panleucopenia. The Hartmann’s solution was reduced to 8 ml/kg/hr and a synthetic colloid (6% hydroxyethyl starch, Voluven®) infusion commenced at 1 ml/kg/hr. Broad-spectrum antibiosis was commenced using amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (20 mg/kg i.v. q 8 hr). A constant rate infusion of a complete liquid diet was commenced at a rate that would meet a third of the puppy’s resting energy requirement (RER) over the initial 24 hours.

The puppy was monitored closely, including regular weighing and gentle abdominal palpation in case of intussusception, and supported intensively as required. Therapy was weaned as appropriate and the puppy was eventually discharged 1 week following presentation, by which time normal faeces had been observed.

Canine Idiopathic Haemorrhagic Gastroenteritis (HGE)

Case example 9

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 6-year-old male neutered Border Collie presented with a 2-day history of vomiting and diarrhoea. The diarrhoea had become progressively more haemorrhagic and the dog was increasingly inappetent and lethargic. No significant preceding history was reported.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was ambulatory but depressed. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 160 beats per minute with absent dorsal pedal pulses and weak femoral pulses. Intermittent pulse deficits were identified. Mucous membranes were pale with a prolonged capillary refill time and the dog’s extremities were cold. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. The dog’s abdomen was tense and painful on palpation but a fluid thrill could not be detected. Mild hypothermia was identified (rectal temperature 37.0°C) and severe dehydration suspected.

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood collected for an emergency database that showed marked haemoconcentration (manual PCV 74%, reference range 37–55%) with normal TS (60 g/l, reference range 49–71 g/l). The emergency database also revealed:

Electrocardiography revealed sinus rhythm with intermittent uniform ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) (see Figure 12.4).

Clinical Tip

Case management

Aggressive fluid resuscitation was performed starting with a 60 ml/kg bolus of 0.9% sodium chloride solution (normal, physiological saline). This produced some improvement but the dog remained mildly hypovolaemic and a further 20 ml/kg bolus was administered, after which euvolaemia was restored. Thereafter fluid therapy was administered at a rate calculated (8 ml/kg/hr) to treat the dog’s dehydration, and perfusion and hydration parameters were monitored regularly. Fluid therapy was adjusted as indicated and colloidal support was not required.

Abdominal radiography showed mild focal gaseous dilation of the small intestine and no peritoneal fluid was detected ultrasonographically. Faecal analysis (cytology, microbiology and testing for parvoviral antigen) was unremarkable although a sample was not submitted for clostridial enterotoxin. Although the electrolyte abnormalities in this case were not consistent with classic hypoadrenocorticism, an adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH) stimulation test was performed to rule out atypical hypoadrenocorticism (see Ch. 34) and found to be unremarkable. A presumptive diagnosis of canine idiopathic HGE was made based on typical clinical presentation and progression, and exclusion of other differential diagnoses.

The dog was discharged 4 days after initial presentation following satisfactory improvement.

Canine Open-Cervix Pyometra

Pyometra typically affects mature bitches but may occur in bitches of any age. Most present within 12 weeks of the end of the previous oestrus but the condition may occur at any stage of the oestrus cycle as well as during pregnancy. No association has been shown between pseudopregnancy and pyometra but an increased incidence is reported in nulliparous bitches.

Diagnosis

Common clinical signs include polyuria/polydipsia and a malodorous mucopurulent vaginal discharge. An enlarged viscus may be palpable in the caudal abdomen and the cervix is found to be open on vaginal examination. Neutrophilia is a common finding and cytology of vaginal discharge reveals large numbers of degenerate neutrophils with intracellular bacteria.

Abdominal radiography reveals convoluted loops of tubular fluid opacity in the caudal abdomen with dorsal displacement of the descending colon (Figure 29.9), and ultrasonography shows enlarged uterine horns distended with hypoechoic fluid (Figure 29.10).

Treatment

Ovarohysterectomy remains the recommended treatment for pyometra in bitches without significant reproductive value or when the owner has no particular desire to breed from the bitch. However, good success rates have been reported with medical therapy when used in dogs with open-cervix pyometra. Protocols implemented include the use of prostaglandin, prolactin inhibition and/or progesterone receptor antagonists. Medical therapy is not recommended for bitches with closed-cervix pyometra due to a greater risk of potentially fatal complications.

Broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy should be administered to all cases, regardless of whether surgical or medical therapy is used. The bacteria most commonly isolated from the uterus in pyometra include Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus, Pseudomonas and Proteus species. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, a cephalosporin or potentiated sulphonamide are good empirical choices. Longer courses will be needed in dogs receiving medical therapy.