40 Notes on transfusion medicine

There is an increasing availability to nonreferral practices of products for transfusion through commercial and charitable pet blood banks, and a good understanding of the basic principles of transfusion medicine is essential. This is to ensure that the recipient is treated in the safest and most appropriate way, that the owner’s resources are put to greatest use, and that the product which was donated by another animal, sometimes requiring sedation, is in fact used in the most beneficial manner. In the author’s opinion, the latter is sometimes readily overlooked and ultimately it must be remembered that animal blood donors do not volunteer for the task!

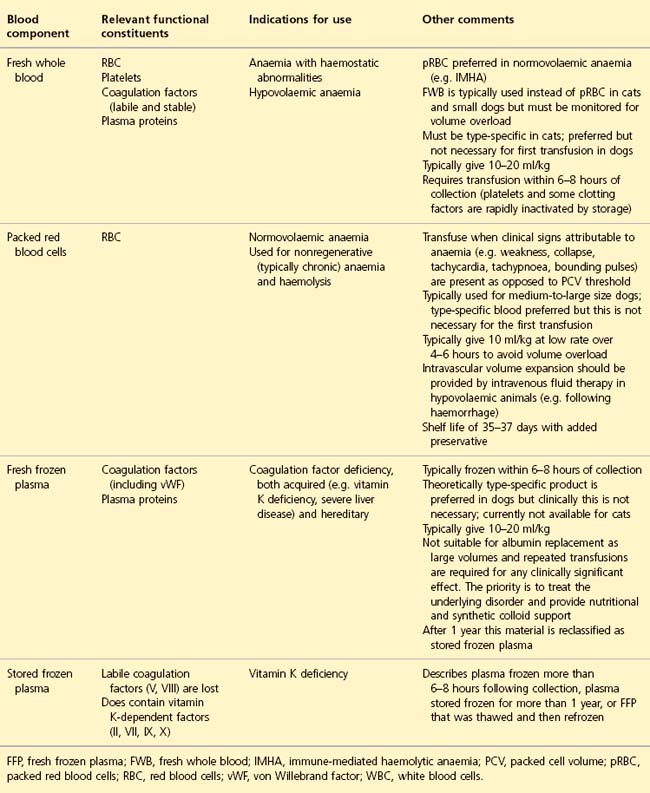

Blood Components

Use only the blood product indicated to minimize risk of a transfusion reaction and reduce the total volume to be administered (Table 40.1).

Anaemia – normovolaemic versus hypovolaemic

Normovolaemic anaemia

•

e.g. chronic nonregenerative anaemia, acute haemolytic anaemia.

•

These patients require oxygen-carrying capacity and therefore ideally packed red blood cells (pRBC) only.

•

Separation of feline whole blood into components is not commonplace, so cats typically receive fresh whole blood (FWB) transfusion.

•

It is often less wasteful to use FWB for small dogs (although smaller or half-units of pRBC may be satisfactory).

•

Recipients should be monitored for volume overload.

Hypovolaemic anaemia

•

These patients require both intravascular volume expansion and oxygen-carrying capacity.

•

Typically use aggressive isotonic crystalloid or synthetic colloid therapy to correct the hypovolaemia (see

Ch. 4), and lower rate FWB or pRBC transfusion for the anaemia.

•

Haemoglobin-based oxygen-carrying solutions may have a role in the treatment of hypovolaemic anaemia (see

Ch. 4).

Blood Types

These are determined by species-specific inherited antigens on the red blood cell surface.

Canine blood types

•

Dog erythrocyte antigen (DEA) 1.1, 1.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 (plus others); positive or negative for each DEA type.

•

DEA 1.1 is extremely antigenic.

•

Blood typing is typically restricted to determining DEA 1.1-positive or -negative status.

Clinical Tip

•

If blood typing cannot be performed, DEA 1.1-negative blood should ideally be given if available. However, dogs are not believed to have clinically significant, naturally occurring antibodies against foreign red blood cell surface antigens (alloantibodies) and therefore the first blood transfusion between two dogs of opposite blood types is unlikely to cause an acute transfusion reaction. Therefore DEA 1.1-positive blood can be used for the first transfusion if necessary. However, it will induce alloantibody production that may then shorten the lifespan of the transfused red blood cells.

•

Once a dog has received a blood transfusion, regardless of whether this was type specific or not, sensitization may occur. It is probably only safe to repeat the transfusion within 4 days before crossmatching becomes essential.

Feline blood types

Routine testing is carried out for blood types A, B and AB.

Type B

•

More common among exotic and pure breeds – e.g. British short hair, Devon Rex, Cornish Rex, Abyssinian, Persian, Himalayan, Somali and Maine Coon.

•

Most type B cats have high levels of strong, naturally occurring anti-type A alloantibodies (from 2 months of age).

•

Severe and potentially fatal transfusion reaction is a very real possibility if a type B cat is given type A blood.

Type A

•

The majority are type A.

•

A small percentage of type A cats have weak, naturally occurring anti-type B alloantibodies (from 2 months of age).

•

A type A cat receiving type B blood is at risk of a transfusion reaction but this should be relatively mild and certainly not fatal.

Type AB

•

These cats do not possess naturally occurring antibodies to type A or B red cell antigens.

•

They could therefore receive type A or type B (or type AB) red blood cells; however, because cats typically receive fresh whole blood, a type A donor is preferred as anti-type A alloantibodies in the plasma of a type B donor cat could result in a transfusion reaction.

Clinical Tip

•

Ideally cats must be blood typed prior to even the first transfusion and receive type-specific blood; crossmatching must be performed for any subsequent transfusion. If blood typing is not possible, use of a haemoglobin-based oxygen-carrying solution (see

Ch. 4) should be considered as a readily available and often invaluable substitute that does not carry risks with respect to transfusion reactions. If this is not available, immediate referral of the case should be considered, although some severely anaemic cats are too unstable to travel.

•

In the exceptional circumstance when an untyped blood transfusion must be given, it is essential to try to minimize the associated risks by using a donor cat that is likely to have the same blood type as the recipient (e.g. domestic short hair donor for a domestic short hair recipient as both are likely to be type A; exotic breed donor for an exotic breed recipient to at least try to increase the likelihood that both are type B). This situation is far from ideal, especially if the recipient is potentially type B, and the owner must be warned of the significant risks.

In-house blood typing

All practices likely to perform regular transfusions should invest in this facility. Most methods involve visualization of an agglutination reaction between a red cell surface antigen if present and antibodies specific for that antigen.

•

Blood-typing cards (RapidVet-H Canine DEA 1.1

® and RapidVet-H Feline A, B, AB

®, DMS Laboratories, New Jersey, USA) are currently used most widely

•

Other systems are increasingly available and may offer advantages, especially easier interpretation (e.g. DME VET DEA 1.1

® and DME VET DEA A+B

®, Alvedia, Lyon, France; DiaMed ID-Card Anti-DEA 1.1 (Dog)

® and DiaMed ID-Card Anti A+B (Cat)

®, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., California, USA).

Crossmatching

This is used to detect existing antibodies to red cell antigens, but does not test for antibodies against white blood cell or platelet antigens that may cause nonhaemolytic transfusion reactions. Compatible crossmatches do not guarantee normal red blood cell survival as delayed transfusion reactions may occur.

In-house testing (e.g. RapidVet-H Crossmatch®, DMS Laboratories, New Jersey, USA) is becoming increasingly available.

Major crossmatch

This tests for alloantibodies in the recipient’s plasma to donor red cell antigens. This type of incompatibility has the potential to be associated with the most severe transfusion reactions as the recipient plasma volume, and therefore alloantibody concentration, is large (hence major).

Minor crossmatch

This tests for alloantibodies in the donor’s plasma to recipient red cell antigens. Transfusion reactions are likely to be less severe as the donor plasma volume, and therefore alloantibody concentration, is smaller (hence minor).

Controls

A donor and a recipient control test is usually also performed that checks for any reaction between each individual’s serum and its own red blood cells.

Transfusion Reactions

Clinical Tip

•

All animals receiving a blood component transfusion should be monitored closely for an acute transfusion reaction, ideally using a dedicated transfusion monitoring chart.

•

A number of parameters, including heart and pulse rate, respiratory rate and effort, mucous membrane colour and capillary refill time, rectal temperature, and mentation are monitored before, regularly during and for a period after the transfusion. Plasma and urine colour should also be monitored if possible.

•

The reader is referred to other sources for more information on transfusion monitoring.

Transfusion reactions are typically classified as acute or delayed and then further classified as immunological (haemolytic or nonhaemolytic) or nonimmunological.

Acute haemolytic transfusion reaction

This is a type of immunological reaction (immunoglobulin (Ig) M (or IgG)-mediated type II hypersensitivity reaction). It occurs when the recipient has pre-existing alloantibodies to donor red blood cell surface antigens, and is the most concerning type of transfusion reaction.

Canine acute haemolytic transfusion reaction

•

The normal lifespan of canine red blood cells is 100–120 days.

•

The half-life of transfused canine red blood cells in the recipient is approximately 21 days.

•

It can be as little as 30 minutes with acute haemolysis.

Clinical findings

•

Tachycardia, tachypnoea or dyspnoea, weakness, collapse, salivation, vomiting and pyrexia.

•

Evidence of haemolysis:

–

Intravascular: haemoglobinaemia and haemoglobinuria; may become apparent within minutes of starting the transfusion

–

Extravascular: hyperbilirubinaemia and bilirubinuria are usually associated with less severe signs.

Intervention

•

Stop transfusion immediately.

•

Start appropriate fluid therapy to treat hypoperfusion if it is present.

•

Other symptomatic treatment.

•

Corticosteroids are not used in human medicine.

Feline acute haemolytic transfusion reaction

•

The normal lifespan of feline red blood cells is 70–80 days.

•

The half-life following appropriately matched allogenic transfusion is 29–39 days.

Type B blood given to a type A cat

•

A minor transfusion reaction is possible, reducing red cell half-life to approximately 2 days.

•

Clinical signs may occur within minutes but should be mild – lethargy, restlessness, tachycardia and tachypnoea.

•

Possible evidence of intravascular haemolysis, i.e. haemoglobinaemia, haemoglobinuria.

Type A blood to be given to a type B cat

•

This is likely to cause a severe and potentially fatal transfusion reaction, with red cell half-life reduced to several hours or less.

•

Clinical signs include gastrointestinal signs, salivation, vocalization and marked cardiorespiratory abnormalities.

•

There may be evidence of intravascular haemolysis, i.e. haemoglobinaemia, haemoglobinuria.

•

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), maldistributive shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) are all possible.

•

The severity of the reaction is usually proportional to the amount of blood transfused but even 1 ml may be enough to trigger a reaction.

Intervention

•

Stop transfusion immediately.

•

Give appropriate fluid therapy to treat hypoperfusion if it is present.

•

Other symptomatic treatment.

•

Corticosteroids are not used in human medicine.

Acute allergic transfusion reaction

•

This is a nonhaemolytic immunological reaction (type I hypersensitivity reaction, usually IgE or mast-cell mediated).

•

It occurs within seconds to minutes of the transfusion being started.

•

An allergic reaction to plasma proteins is a potential cause of transfusion reactions when only plasma is transfused (i.e. despite absence of red blood cells).

Clinical signs

•

These are usually mild, self-limiting or readily amenable to treatment and include erythema, pruritus, urticaria and oedema.

•

Occasionally there are more severe anaphylactic reactions with cardiovascular, respiratory or gastrointestinal signs.

Clinical Tip

•

An acute haemolytic transfusion reaction may be clinically indistinguishable from an allergic reaction and it is therefore important to check for evidence of intravascular (haemoglobinaemia, haemoglobinuria) and extravascular (hyperbilirubinaemia, bilirubinuria) haemolysis.

Intervention

•

Discontinuing the transfusion may be all that is needed.

•

Restart at a slower rate (e.g. half of the original rate) if the reaction subsides and monitor closely.

•

Intravenous fluid therapy, corticosteroid or antihistamine may be required – judge on the individual case basis. Anaphylactic shock requires aggressive management (see

Ch. 26).