4 Parenteral fluid therapy

Parenteral fluid therapy is the most common therapeutic intervention performed in veterinary emergency practice. A thorough understanding of the indications for the use of parenteral fluids, the types of therapeutic fluid available, and the most appropriate protocol for their administration is mandatory both to maximize the benefit and minimize the potential harm associated with this therapy.

Hypovolaemia and dehydration are the most common indications for the use of fluid therapy and it is essential to understand their differences with respect to pathophysiology and clinical assessment in order to administer appropriate fluid therapy (see Ch. 2). This chapter focuses on the different types of parenteral fluid commonly available in nonreferral emergency practice and their appropriate use in hypovolaemia and dehydration.

Types of Parenteral Fluid

Crystalloids

Crystalloids are electrolyte solutions that can pass freely out of the bloodstream through the capillary membrane. Crystalloid solutions are described as isotonic, hypertonic or hypotonic based on how their tonicity compares to that of plasma. The tonicity is related to the sodium concentration and it is the tonicity that determines how the crystalloid solution is distributed between fluid compartments following administration into the bloodstream.

The two most commonly used crystalloid solutions are buffered lactated Ringer’s solution (Hartmann’s solution, compound sodium lactate) and 0.9% sodium chloride (normal strength or physiological saline). Both these solutions are examples of replacement isotonic crystalloids as their tonicity and electrolyte composition are similar to that of extracellular fluid. Following intravascular administration, these fluids equilibrate relatively quickly with the interstitial space and 75–85% of the administered volume is likely to have left the bloodstream 30–60 min after infusion. This is why large volumes are required to expand the intravascular compartment effectively in hypovolaemia and is also the reason why these solutions are used to replenish extravascular fluid losses in dehydration (see below).

Hypertonic (e.g. 7.2–7.5% sodium chloride (hypertonic saline)) and hypotonic (e.g. 0.45% sodium chloride (half strength saline)) crystalloid solutions are also available but their use is much less commonly indicated. Hypertonic saline administration causes plasma volume expansion mainly by drawing water out of cells into the extracellular space down an osmotic gradient. Most of this fluid remains in the interstitial space but a proportion diffuses into the vasculature. The recommended dose is 4 ml/kg i.v. (dogs 4–7 ml/kg, cats 2–4 ml/kg) over a minimum of 5 minutes and a rapid though short-lived effect is typically seen (within 5 minutes). Hypertonic saline is indicated in volume resuscitation, especially in large or giant breed dogs where rapid administration of large volumes of isotonic crystalloids may be impossible. Administration of hypertonic saline must be followed by the use of a replacement isotonic crystalloid due to the osmotic diuresis and rapid sodium redistribution that occur with this treatment. Hypertonic saline is often administered in combination with a colloid solution to prolong intravascular volume expansion. Hypertonic saline is also indicated in the treatment of raised intracranial pressure, especially with concurrent hypovolaemia, where it causes fluid to move out of the brain parenchyma and into the vasculature (see Ch. 28).

Hypotonic saline is most often used in combination with 0.9% sodium chloride to correct hyponatraemia gradually. It is also occasionally used in dehydrated animals with cardiac disease to provide rehydration while limiting the amount of sodium administered.

Clinical Tip

Synthetic colloids

Colloid solutions consist of large (macro) molecules that do not readily leave the intravascular space (through capillary pores) and are hyperoncotic relative to normal animals. Synthetic colloids therefore draw fluid into and hold fluid in the vasculature, causing plasma volume expansion. Commercially available synthetic colloid preparations are often made up in a 0.9% sodium chloride solution. Nonsynthetic (natural) colloid solutions that are currently used therapeutically include plasma and human serum albumin solutions.

The three types of synthetic colloid solution currently in veterinary use are:

The volume and duration of plasma expansion that follows colloid administration depend in part on the specific colloid used (its colloid osmotic pressure (COP)), as well as the dose given and the species in question.

Indications for synthetic colloid use

Synthetic colloids are usually used in hypovolaemic patients in one of two scenarios:

Synthetic colloids are not generally used alone when employed in the treatment of hypovolaemia and are typically discontinued earlier on than the replacement crystalloid solution. It is much less common for patients to remain on long-term colloid therapy (although on-going hypoproteinaemia or the presence of systemic vasculitis or capillary-leak syndrome for example may warrant this treatment).

Haemoglobin-based oxygen-carrying solutions

Haemoglobin-based oxygen-carrying solutions (HBOC) are not blood replacement solutions. They increase plasma haemoglobin concentration and therefore oxygen-carrying capacity but do not contain other blood constituents. The only HBOC currently available for veterinary clinical use is Oxyglobin® (Biopure Corporation; www.biopure.com). This solution is based on polymerized modified bovine haemoglobin and is administered using standard intravenous fluid administration sets. It is currently only licensed for use in dogs but has been used extensively off-licence in cats with great success.

The main indication for Oxyglobin® is in euvolaemic anaemia where it can act as a substitute for the deficient red blood cells and allow improved tissue oxygenation. Unlike with blood transfusions, there are no cellular antigens in Oxyglobin® so typing and crossmatching do not need to be performed. The product as supplied in foil by the manufacturer also has a long shelf-life of 3 years. Oxyglobin® is used in these cases to support the patient while diagnosis is achieved and treatment is instituted and given time to take effect.

Clinical Tip

Administration of Oxyglobin® typically causes a fall in packed cell volume (PCV) due to intravascular volume expansion. Ideally, therefore, plasma haemoglobin concentration should be used to monitor increase in oxygen-carrying capacity in lieu of packed cell volume. An approximately equivalent PCV can be calculated as follows:

However, a haemoglobinometer is required to measure free plasma haemoglobin concentration as in-house machines typically calculate haemoglobin concentration from haematocrit. Regardless of whether a haemoglobinometer is available or not, positive clinical response to treatment is the best guide of effective therapy.

As Oxyglobin® contains large molecules it is also a potent colloid solution and can therefore be used very effectively to provide intravascular volume expansion in animals with hypovolaemia. Despite the unique oxygen-carrying benefits of this modified biological colloid, the much greater cost of Oxyglobin® over other available colloids means that its use in hypovolaemia is typically restricted to animals that have suffered significant blood loss.

Clinical Tip

As with all colloids, Oxyglobin® will interfere with serum total solids measurement via refractometry and results must be interpreted cautiously. Oxyglobin® will also interfere with colorimetric serum biochemistry analysis although the parameters affected will depend on both the analyser and the methodology. Peripheral blood smear evaluation is not affected.

The Fluid Plan

On the basis of the physical examination, and subsequently other findings, it should be possible to answer the following questions (see Ch. 2):

Hypovolaemia

The basic objective is to restore the effective circulating intravascular volume and thereby restore adequate tissue perfusion. Appropriate fluid therapy is therefore provided until end-points suggestive of acceptable systemic perfusion are achieved. This volume expansion is performed over a short period of time – usually a few minutes to an hour but sometimes longer – and may involve the use of both isotonic crystalloids and colloids including Oxyglobin® (plus whole blood and hypertonic saline if available). Isotonic crystalloids are the first choice in the majority of cases.

How?

Hypovolaemia is treated via the intravenous route using one or more of the shortest but largest bore catheters possible. If a peripheral vein cannot be catheterized and a central venous catheter is not available or inappropriate, the intraosseous route may be used initially.

How much and for how long?

Isotonic crystalloids

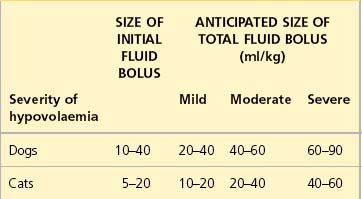

See Table 4.1 for guidelines for initial rates of isotonic crystalloid fluid therapy in dogs and cats with uncomplicated hypovolaemia. Initial boluses are usually given over 15–20 minutes. For some bigger dogs the use of a pressure infusor (Figure 4.1) around the crystalloid bag can be invaluable in delivering the fluid within a suitable period of time.

Colloids

In moderate to severe hypovolaemia, the following rates of colloid administration are applicable:

| •Dogs: | 5 ml/kg boluses up to a total of 20 ml/kg |

| •Cats: | 5 ml/kg boluses up to a total of 10 ml/kg |

| •Oxyglobin®: | 10–30 ml/kg total dose. |

Whenever a synthetic colloid is added to an animal’s fluid regime, due attention must be paid to whether this affects the rate of crystalloid therapy, with the latter being reduced if appropriate (often by about 50%).

Approach to fluid resuscitation

Initial rates of fluid therapy for volume expansion were traditionally quoted per hour. However, it is more appropriate to think in terms of bolus administration and constant reassessment.

Clinical Tip

A dog with hypoperfusion secondary to severe hypovolaemia for example may be given an initial intravenous isotonic crystalloid bolus of 40 ml/kg over 20 minutes:

Clinical Tip

Dehydration

The basic objective in the treatment of dehydration is to replenish the deficit from all fluid compartments that are affected. A significant proportion of dehydrated animals have minimal intravascular deficits (i.e. they are not hypovolaemic) and the aim of fluid therapy in these cases is therefore to replace fluid losses from the extravascular (interstitial and intracellular) compartments.

Dehydration is corrected over a longer period of time than hypovolaemia – typically 12–48 hours depending on the severity and rate of onset – and is usually achieved through the use of replacement isotonic crystalloids alone. In animals that have a normal intravascular volume, excessively aggressive rehydration will overexpand the interstitial compartment. This is manifested clinically as increased skin turgor, chemosis, subcutaneous pitting oedema and pulmonary oedema. Once pulmonary oedema (i.e. fluid overload of the pulmonary interstitial space) has developed, and despite the extensive protective lymphatic drainage available, alveolar flooding may occur and can be very severe if not addressed early enough. Cerebral oedema is another possible and extremely serious consequence of overexpansion of the interstitial compartment.

How?

Fluid therapy for rehydration is also usually given by the intravenous route. In some cases, the use of the subcutaneous route may be a reasonable option. Examples include:

Subcutaneous fluid therapy is also used intermittently to provide fluid support in chronic illnesses such as chronic renal failure. Its sole use is inappropriate in patients with hypovolaemia as absorption is too slow due to poor peripheral perfusion. An empirical total volume of 10 ml/kg of an isotonic crystalloid is usually given distributed over multiple sites; this clearly is highly dependent on patient compliance.

How much?

The equation that is traditionally used to calculate the fluid requirement of a dehydrated patient over a chosen period of time is:

Replacement volume

The volume of fluid required to replace the deficit in a dehydrated animal is calculated as follows:

Despite the inherent inaccuracies (see Ch. 2), estimating the patient’s percentage dehydration on the basis of physical examination is useful as it allows the above calculation to be made.

Maintenance requirement

Clinical Tip

The commonly cited figures for maintenance crystalloid requirements are 2 ml/kg/hr or 50 ml/kg/day. While these rates may be appropriate for the majority of fully grown dogs and cats, the notion that all dogs and cats have the same maintenance fluid requirements is counterintuitive when one considers, for example, a 3-year-old Great Dane versus a 6-week-old Yorkshire terrier. It is more appropriate therefore to use a range for fully grown dogs of 1.5 ml/kg/hr (larger dogs) up to 4 ml/kg/hr (very small dogs), and a range for fully grown cats of 2–3 ml/kg/hr. Maintenance requirements for puppies and kittens are higher than for adult dogs and cats. Maintenance rates as high as 8 ml/kg/hr have been described by some authors, for example for paediatric animals of toy breeds. In addition, maintenance requirements for overweight animals should be calculated using a reduced body weight.

On-going losses

The practicalities of accurately quantifying on-going losses (e.g. vomitus, diarrhoea) in addition to those assumed in maintenance requirements preclude this as a realistic option in most settings. In order to allow initial fluid requirements to be calculated, a useful technique is to estimate the contribution from these on-going losses in terms of multiples of the patient’s maintenance requirements. Thus some animals may have no additional contribution here; a vomiting animal may have an extra maintenance requirement added; and an animal with profuse vomiting and diarrhoea may have or more extra maintence requirement added to the initial calculation.

For how long?

The initial fluid plan calculated for a dehydrated patient is an approximation and must be approached dynamically; both the rate and the type of fluid used need to be reassessed. A range of different factors are taken into account, including:

Due attention must also be paid to the provision of supplementary potassium in particular in appropriate cases.

Fluid Therapy Case Examples

The rest of this chapter will use some common canine and feline emergencies to highlight situations in which a more conservative approach is recommended in the aggressive fluid resuscitation of hypovolaemic patients. There is no set protocol for fluid therapy in any given situation and what follows are merely suggestions intended as a guide and to prompt discussion of other available options in each case. In addition to the case examples presented here, it is noteworthy that recent or active haemorrhage may be a reason to be more conservative with fluid therapy as overzealous volume expansion has the potential to exacerbate bleeding by disrupting blood clots at sites of haemostasis. Providing only sufficient fluid therapy to restore perfusion to minimum end-points may be most sensible in these cases but it must be remembered that restoration of effective circulating volume is essential.

Use of parenteral fluid therapy is further demonstrated by the case examples referred to throughout the book.

Case example 1 – pulmonary pathology

Clinical Tip

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 3-year-old male neutered domestic short hair cat presented shortly after a suspected motor vehicle accident. The incident was estimated to have occurred within the 2 hours prior to presentation. The cat was initially found collapsed under a hedge. He had subsequently been seen to take a few steps but was reportedly very lame in his pelvic limbs. No other significant preceding history was reported.

Major body system examination

On presentation the cat was depressed and recumbent. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 150 beats per minute and neither a gallop sound nor a heart murmur was detected. Both femoral pulses were palpable but very weak and dorsal pedal pulses were not identified. Mucous membranes were pale, dry and cold to touch, and capillary refill time was 2 seconds. The extremities were also cold.

Respiratory rate was 50 breaths per minute with a shallow, nonparadoxical and regular pattern. Lung sounds were diffusely harsh and bilaterally symmetrical. The pupils were equal and reactive and there was no external evidence of significant head trauma. No gait assessment was made at this stage. Abdominal palpation revealed a small soft bladder and was unremarkable. There was evidence of urine staining around the perineum and the cat was moderately hypothermic (rectal temperature 35.5°C).

Assessment

The cat was assessed as hypoperfused due to moderate hypovolaemia (presumably due to haemorrhage plus effects on vasomotor control). The degrees of hypothermia and bradycardia were not considered unusual for a moderately hypovolaemic cat (see Ch. 2), and his mentation was considered appropriate for the severity of hypoperfusion with a low index of suspicion for raised intracranial pressure. Some respiratory compromise was present and pulmonary contusions were considered the most likely cause of the harsh lung sounds.

Management discussion

There is no information in this cat’s history prior to the traumatic incident that would contraindicate the use of aggressive fluid therapy. In addition, both the absence of any significant preceding history and the time scale in question do not support the likelihood of pre-existing dehydration.

The suspicion of pulmonary contusions (see Ch. 28) is a reason to be more conservative with resuscitative fluid therapy in this case. The aim of fluid therapy should be to restore acceptable tissue perfusion while avoiding excessive fluid administration. Commencing volume expansion using an isotonic replacement crystalloid solution is an appropriate choice in this cat but a conservative initial bolus of only 5–10 ml/kg may be most sensible. At the end of the bolus perfusion parameters and respiratory status should be reassessed. If significant hypovolaemia persists, another 5–10 ml/kg isotonic crystalloid bolus may be given and the cat reassessed.

If significant hypovolaemia still persists after the second crystalloid bolus, the next step may be to assess the cat’s response to a conservative (e.g. 2–3 ml/kg) synthetic colloid bolus. This may reduce the risk of expanding the pulmonary interstitial space to the point of alveolar flooding, which would exacerbate the existing respiratory compromise from contusions. However, in some types of lung pathology, the pulmonary vasculature can become leakier to colloid molecules despite their large size. Once the colloid molecules move into the pulmonary interstitium they may worsen pulmonary oedema and may persist there for some time. Nevertheless, it is not possible to predict in advance whether this will occur and it is therefore recommended to assess the patient’s response to a colloid bolus and discontinue this therapy if the respiratory status worsens as a result.

Given the concerns in this case regarding pulmonary contusions, intravenous fluid therapy should be discontinued as soon as the cat’s perfusion is adequately restored. Conservative fluid therapy may need to be restarted for any procedures subsequently performed under general anaesthesia or sedation if hypotension becomes a concern. Maintenance fluids (including potassium supplementation) may be required if the cat is anorexic while hospitalized.

Intravenous fluids should be warmed to body temperature prior to administration. However, it is important to start fluid therapy before other warming measures are instituted. This is because warming a hypothermic (and therefore peripherally vasoconstricted) animal will cause cutaneous vasodilation that may exacerbate existing hypotension. Oxygen supplementation is recommended and opioid analgesia is mandatory in this cat.

Case example 2 – cardiac disease, intracranial hypertension

Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 10-year-old male neutered Cavalier King Charles spaniel presented 30 minutes after a motor vehicle accident witnessed by the owner. The dog fell over briefly as a result but no loss of consciousness was observed. He had been very subdued since the incident. The owner also reported that the dog had been less keen to exercise for a few weeks and was panting more during his walks. He had also been coughing intermittently although this had not become noticeably worse. His appetite had been variable but there had been no other clinical signs.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was markedly depressed. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 140 beats per minute and a grade IV/VI systolic murmur with the point of maximal intensity over the mitral valve region. Femoral pulses were hyperdynamic and dorsal pedal pulses were readily palpable. Mucous membranes were mildly hyperaemic with a capillary refill time of 1 second and the dog’s extremities were normal to the touch. Respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute with normal pattern and effort, and lung field auscultation was unremarkable. Gait assessment was not made at this stage.

Anisocoria was present with slow but intact pupillary light reflexes (both direct and consensual); bilateral menace responses were identified. There was left-sided scleral haemorrhage but no blood in the left ear canal and no readily palpable skull fractures. Abdominal palpation was nonpainful with a moderate size bladder palpable and rectal temperature was mildly reduced (37.7°C).

Assessment

The dog was assessed as mildly hypovolaemic with an inappropriately depressed mentation, i.e. he was more depressed than would be expected from mild hypovolaemia/hypoperfusion alone. This finding, supported by the anisocoria and scleral haemorrhage, was suggestive of raised ICP secondary to head trauma. The tachycardia may have been compensatory for the hypovolaemia and/or secondary to pain. However, the possibility of pre-existing cardiac insufficiency could not be excluded and it was possible that the dog had had a resting tachycardia in the weeks prior to this incident.

Management discussion

This dog is of a breed that is predisposed to mitral valve disease and his reported history raises the suspicion of this becoming clinically significant. It is difficult to know how important the heart disease is in the dog’s clinical presentation.

Commencing acute volume expansion using an isotonic crystalloid solution is an option in this dog. However, the benefits of restoring euvolaemia and thereby optimizing cerebral perfusion have to be balanced with the possibility of clinically significant cardiac disease. If the dog was suitably compliant, conscious thoracic radiography may help guide therapy by providing further information with respect to left atrial enlargement and pulmonary congestion and oedema. If facilities and expertise allow, echocardiography to evaluate left atrial size more accurately would be very useful.

In this case it may be more appropriate for example to administer an initial isotonic crystalloid rate of 3 ml/kg/hr rather than bolus therapy. This is especially true if blood pressure measurement was possible and the dog was found to be normotensive. Perfusion parameters and respiratory status should be reassessed regularly and the rate adjusted as appropriate. Given the greater concerns in this case with respect to fluid overload, intravenous fluid therapy should be discontinued as soon as possible. Although this dog does not have any pre-existing dehydration that requires replacement, maintenance fluids may be required if he remains depressed for an extended period of time. A conservative isotonic crystalloid rate of 1 ml/kg/hr should be considered and a hypotonic solution such as 0.45% sodium chloride may be more appropriate if available. Oxygen supplementation is recommended and opioid analgesia is mandatory.

Case example 3 – rehydration

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 3-month-old male entire Staffordshire bull terrier (4 kg) presented with a 2-day history of vomiting and diarrhoea. The puppy had not eaten anything at all for 12 hours and although continuing to drink was typically vomiting immediately afterwards. He had vomited approximately four times each day. The diarrhoea was occurring with increasing frequency and while watery initially had progressed to being bloody.

The puppy had been in the owner’s possession for 1 week and was acquired from a private family. He had been appropriately wormed but had not been vaccinated and the owner was unsure regarding the dam’s vaccination status. The owner was unaware of any significant scavenging incidents and the puppy had been confined to the house.

Major body system examination

On presentation the puppy was ambulatory but markedly depressed. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 130 beats per minute and no murmur, gallop sound or dysrhythmia was detected. Femoral and dorsal pedal pulses were unremarkable and mucous membranes were pink and dry with a normal capillary refill time. Respiratory rate was 30 breaths per minute, and respiratory pattern and effort and lung field auscultation were unremarkable.

The puppy’s abdomen was diffusely painful on palpation and the intestines were fluid-filled with no normal faeces palpable. A focal lesion suggestive of surgical disease was not identified. Rectal temperature was 37.5°C and there was fresh blood on the thermometer.

Management discussion

The puppy will have salt and water losses affecting both the extravascular and intravascular compartments and a replacement isotonic crystalloid solution is an appropriate initial choice. Additional potassium and glucose supplementation may be indicated once an emergency database has been obtained. The initial fluid rate for this puppy is calculated as follows:

Maintenance requirement

Given this dog’s age an estimated maintenance requirement of 4 ml/kg/hr is used:

On-going losses

Given this dog’s presenting history, an additional maintenance requirement is added initially to allow for on-going losses:

The puppy’s fluid requirement for the replacement period of 12 hours is therefore:

At the end of the replacement period, the fluid rate should be reduced to meet maintenance and on-going loss requirements. The reader is reminded again that this type of calculation is helpful to provide an initial fluid rate but is derived using a number of assumptions and approximations. The rate should be adjusted as necessary in accordance with regular assessment of both physical and laboratory parameters.