APPENDIX 2 Procedures – equipment and techniques

In-Dwelling Nasal Oxygen Catheter Placement

Equipment required

Procedure

Thoracocentesis

Equipment required

Procedure

Additional notes

Clinically significant respiratory compromise is generally associated with approximately 20 ml/kg or more of pleural air or fluid. Removal of a smaller volume than this is therefore unlikely to cause significant clinical improvement although smaller volumes may be of greater significance in the presence of concurrent injuries (e.g. pulmonary contusions). If clinical signs do not improve following aspiration of an appropriate volume of pleural air or fluid it suggests that another abnormality exists and is predominantly responsible for the dyspnoea.

This may be the case for example in an animal that has suffered blunt thoracic injury resulting in both pneumothorax and pulmonary contusions. Aspiration of 20 ml/kg of air may only cause partial improvement in clinical signs if pulmonary contusions are significantly involved in the dyspnoea noted. Nevertheless, therapeutic thoracocentesis is still appropriate as it will be of some benefit in improving expansion of the already compromised lungs.

Pericardiocentesis

Equipment required

Procedure

Additional notes

The ECG should be monitored for significant ventricular dysrhythmia (see Ch. 12) throughout – if this is noted, it may be that the catheter is making contact with the myocardium and it should be withdrawn slightly. If the dysrhythmia is very severe or if it does not improve when the catheter is withdrawn slightly, the catheter should be removed completely. Lidocaine (start with 2mg/kg bolus) should be administered intravenously if a ventricular dysrhythmia is haemodynamiacally significant and fails to improve with catheter withdrawal.

A sample of pericardial effusion withdrawn at the start of the procedure should be checked frequently for clotting while the procedure progresses. Pericardial effusion is devoid of platelets and clotting factors and will not clot unless it is from active or very recent haemorrhage. If the catheter has inadvertently punctured a cardiac chamber or there is rupture of a sizeable vessel, blood will be aspirated and will clot. The haematocrit of pericardial fluid is usually less than that of the patient. In addition drainage of pericardial fluid is typically associated with a rapid improvement in patient status.

Abdominocentesis

Equipment required

Procedure

Additional notes

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage

Equipment required

Procedure

Additional notes

It is common to retrieve only a small proportion of the lavage fluid originally infused (the remainder will be absorbed via the peritoneum or removed at surgery).

Due to dilution, fluid obtained via diagnostic peritoneal lavage cannot reliably be subjected to biochemical quantitative analysis; the main uses are cytology and microbiology.

Gastric Decompression – Orogastric Intubation

Procedure

Additional notes

In addition to the opioid that should already have been administered, sedation with an agent that is cardiovascular sparing may be needed for orogastric intubation to be performed (e.g. diazepam to effect).

It must be remembered that the ability to pass a stomach tube does not exclude the presence of some degree of gastric volvulus in gastric dilatation/volvulus syndrome.

Gastric Decompression – Percutaneous Needle Decompression

Procedure

Additional notes

Needle decompression is a quick and easy procedure that is effective in relieving gaseous distension. However, it does involve blindly placing a needle through a gastric wall that may already be severely compromised. It should perhaps therefore be reserved for the following types of cases:

Nasooesophageal Feeding Tube Placement

Equipment required

Procedure

Additional notes

Correct tube placement can also be checked by connecting the feeding tube to a capnograph. If the tube is in the oesophagus, end-tidal carbon dioxide should be approximately 0 mmHg with no waveform. Tracheal placement results in a higher ETCO2 and a capnograph waveform.

Gastric Lavage

Procedure

Urethral Catheterization of Male Cats with Urethral Obstruction

Equipment required

Procedure

Additional notes

Great care must be taken throughout catheterization to minimize trauma to the already inflamed and friable urethra and avoid rupture. Although it can take copious flushing and much patience to achieve catheterization in some cases, in the author’s experience it is almost always achievable.

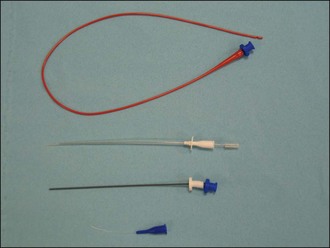

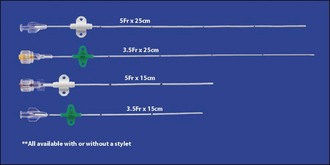

A number of different types of feline urethral catheters are available (Figures App2.2 and App2.3). It is usually necessary to use a rigid catheter to unblock the urethra initially. Although softer catheters can be made stiffer by placing them in the freezer, a rigid catheter such as the Portex® Jackson Cat Catheter (Smiths Medical International Ltd, UK) which is widely available in the United Kingdom is typically used for unblocking. It also has the advantage of a stylet that assists with catheterisation further. However it is preferable not to leave a rigid catheter in situ as there is a greater likelihood of exacerbating urethral and bladder mucosal damage and discomfort. The Jackson catheter is also not very long and can be too short to drain the bladder reliably in bigger tomcats. The rigid catheter should ideally be removed (flushing through the catheter repeatedly as it is pulled out) and replaced with a less traumatic one. MILA® Tomcat Urethral Catheters (MILA International, Inc., Erlanger, KY USA) are provided with optional stylets; they can therefore be used for unblocking and then left in situ. They have wings which can be separated from the catheter tube then repositioned at the appropriate length on the catheter once it has been measured against the cat. The two pieces are then attached together with a suture at each end of the wings, and the wings are sutured to the prepuce using dedicated suture holes (Figure App2.4). As such the catheter is essentially flexible in length. It is also soft and open-ended. Red rubber urethral catheters (3.5- or 5-French; e.g. Kendall Sovereign™, Tyco Healthcare Group LP, Massachusetts, USA) may also be used and are both soft and long. They are fixed to the preputial area using butterfly tapes. The Slippery Sam® (SurgiVet, Smiths Medical Inc., Wisconsin, USA) urethral catheter can be readily sutured in place and connected to a collection system via a suitable luer lock adaptor (e.g. Little Herbert®, SurgiVet, Smiths Medical Inc., Wisconsin, USA). However this catheter is not intended to be left in situ – the warning from the manufacturer at the time of writing is that the catheter and silicone hub are not permanently affixed to each other and it is advised not to leave the catheter in place for more than 6 hours.

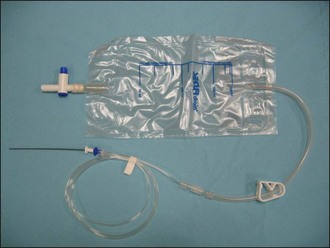

Advantages of a closed urinary collection system include reduced risk of ascending infection, avoiding urine scalding of the perineal region, and overall improved patient welfare (see Figure App2.5). If a proprietary urine collection system is not available, one can be improvised using an intravenous fluid administration set attached to an empty fluid bag. The chances of success with such an improvised system can be maximized by prefilling the administration set (as when setting up an intravenous drip) before it is connected to the urinary catheter and by minimizing the amount of air that gets into the line subsequently. If a closed collection system really cannot be made to work reliably, the urethral catheter can be bunged and the bladder can be manually drained intermittently using aseptic technique. It is clearly essential that this is done regularly. If for some exceptional reason the urethral catheter must be left open, it is recommended to leave a short length of tubing connected to the catheter such that the voided urine will collect at a site away from the cat’s perineum.

Retrograde Urohydropulsion in Male Dogs with Urethral Obstruction

Procedure

Additional notes

Successful retrograde hydropulsion usually requires general anaesthesia or heavy sedation and must therefore only be attempted once the patient has received adequate stabilization of cardiovascular, electrolyte and acid–base status.

Retrograde hydropulsion is intended to flush urethroliths into the bladder and not to push them physically with the catheter. Great care must be taken throughout catheterization to minimize urethral trauma and avoid rupture.

or 5 inch (a variety of other instruments including central venous catheters and small chest drains may be used for pericardiocentesis; the latter may be left in situ in the pericardial sac for repeat drainage short-term)

or 5 inch (a variety of other instruments including central venous catheters and small chest drains may be used for pericardiocentesis; the latter may be left in situ in the pericardial sac for repeat drainage short-term) or 1 inch long) and syringe (2 or 5 ml)

or 1 inch long) and syringe (2 or 5 ml)