18 Dacryocystitis – chronic purulent conjunctivitis

PRESENTING SIGNS

Dacryocystitis is inflammation within the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct. Affected animals are presented with ocular discharge – usually this is mucopurulent in nature. Alternatively, a unilateral red eye due to conjunctivitis with conjunctival hyperaemia and a variable discharge can be the initial presenting sign. It is quite common for the patient not to be brought to the surgery when the signs first develop, but only when they change and become persistent with a chronic mucopurulent discharge. The discharge is most copious at the medial canthus and reforms frequently following cleansing and removal by the owner. Sometimes the medial canthal skin is erythematous or swollen and the patient is uncomfortable. The condition is rarely encountered in cats but occurs occasionally in dogs and quite frequently in rabbits. The latter are discussed separately in Chapter 19.

CASE HISTORY

The patient may have history of a wet eye 1–3 weeks prior to the development of the chronic discharge and the discharge itself could have changed from serous to purulent in nature. A previous conjunctivitis or even removal of a conjunctival foreign body might have occurred. The patient can be any age or breed. Although normally unilateral in dogs, the condition can be bilateral on occasion (this is more common in rabbits, as discussed in Chapter 19).

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

General clinical examination is usually normal in dogs. Ophthalmic examination reveals a unilateral ocular discharge centred around the medial canthus (Figure 18.1). Evidence of pain with blepharospasm or self-trauma though rubbing is variable. Conjunctival hyperaemia is normally present in the nictitans conjunctiva but can be widespread. Schirmer tear test readings are normal. No corneal disease is usually present and the rest of the ocular examination is unremarkable. On cleaning the discharge (after taking a swab for culture and sensitivity testing and cytology for Gram stain) gentle pressure at the medial canthus will often result in the appearance of further purulent material at the nasolacrimal punctae (often just the lower one but sometimes the upper as well). Fluorescein passage to the nostril is absent on the affected side (Figure 18.2); remember to compare both sides, and also that false negatives are common.

Figure 18.1 Right eye of a 5-year-old golden retriever with mucopurulent discharge at medial canthus plus elevation and hyperaemia of nictitans membrane.

Figure 18.2 Another golden retriever with a blocked left nasolacrimal duct – notice the fluorescein at the right nostril but not the left, while it pools below the left eye.

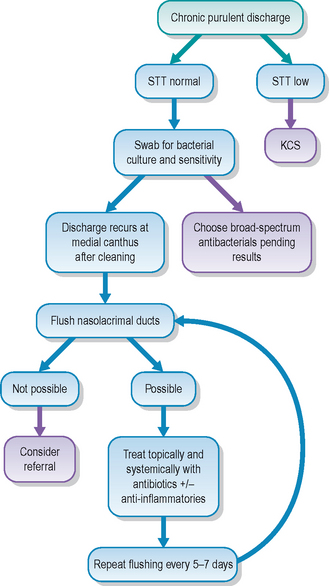

CASE WORK-UP

Nasolacrimal duct flushing is necessary to reach a definitive diagnosis and to assist with establishing the underlying aetiology, if possible. Often this can be done conscious but sedation or general anaesthesia will be required if the condition is painful or if further diagnostic tests are to be undertaken. Some purulent material can be flushed between upper and lower punctae (depending which one is cannulated). Initially there is likely to be resistance to the passage of saline down the nasolacrimal duct to the nose; however, with persistence, and using steadily increasing pressure, it might be possible to establish drainage. Purulent material should be collected from the nasal ostium for bacterial culture and sensitivity testing. If the nasolacrimal flush is not successful under topical anaesthesia or sedation, then the patient should undergo general anaesthesia. Sometimes flushing from one punctum to the other in dogs will lead to the expulsion of fragments of foreign material (most commonly pieces of grass awn) which will suggest similar material down the nasolacrimal duct itself. Care should be exercised to prevent damage to the duct by overzealous flushing. If sharp pieces of foreign material are present, then exerting excessive pressure could result in rupture of the duct. If any bloodstained material is encountered, then further attempts at flushing should be discontinued.

If it is not possible to establish drainage, then there are several options available. The first is to attempt retrograde flushing. This is really only feasible in medium and large sized dogs. The nasal ostium of the duct is located on the ventrolateral nasal meatus approximately 1 cm inside the external meatus. An otoscope or small vaginal speculum is useful to provide magnification and illumination when trying to locate the opening. Initial cannulation with monofilament nylon (e.g. 2/0) is achieved and this is passed up the duct as far as possible – occasionally it is stiff enough to dislodge any inspissated material as the duct widens as it approaches the lacrimal sac. A narrow gauge catheter can be introduced over the nylon thread into the nasal ostium such that retrograde flushing can be attempted.

If retrograde cannulation or flushing is not feasible, then further case work-up will involve radiography – both plain and contrast studies (dacryocystorhinography). Plain radiographs might reveal bony fractures or neoplastic processes which were not clinically noted. Periodontal disease involving the upper premolars or canine teeth might be present, leading to a localized inflammation in the nasolacrimal duct and subsequent obstruction. Contrast studies, using water-soluble contrast agents, can locate the exact blockage and help identify whether surgical intervention is feasible. In dogs, small amounts (1–2 ml) of contrast are injected into the upper punctum while holding the lower one closed, such that the contrast material is forced down the duct. Care should be taken to ensure that no excess contrast material is spilled as this could easily confuse interpretation of the radiographs. It is sensible to take a lateral radiograph after injecting the affected side, followed by dorsoventral or intraoral views after injecting both sides for comparison. Cystic dilations can be delineated by this method, as well as locating radiolucent foreign material. If the blockage is anterior – within the lacrimal bone for example – then referral for surgical removal can be considered.

Frequent gentle bathing is required and owners should be shown how to do this effectively. Sterile saline on cotton wool pads or soft gauze swabs is advised. A combination of topical and systemic medication is normally necessary and again the nurse should ensure that the owner is able to medicate effectively.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Dacryocystitis is usually an isolated unilateral finding in dogs and is not contagious. It is most commonly associated with infection following a conjunctival foreign body or extension of dental disease. Secondary bacterial infections are often due to mixed populations of bacteria, and culture and sensitivity testing is recommended. The lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct are small conduits which easily become blocked. Neoplasia spreading from adjacent structures can occasionally result in dacryocystitis and traumatic fractures in the area can also lead to problems, although other clinical signs would normally assist the diagnosis in this instance.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

Initial medical treatment should involve both topical and systemic antibiotics. Broad spectrum agents are chosen such as topical chloramphenicol and systemic cefalexin until culture and sensitivity results are obtained. Repeated attempts at nasolacrimal flushing are advised every few days. If flushing is successful, then both topical and systemic treatment should be continued for 3–4 weeks – even if the clinical signs appear fully resolved before then. Failure to treat systemically, and to use too short a course of medication, are both common reasons for animals to have recurring problems. Some dogs need 6 weeks of oral antibiotics and owners should be advised that the full course of treatment should be completed to avoid relapses. If there is marked conjunctival inflammation at the medial canthus, then a short course of topical corticosteroid drops can be used alongside the antibiotics. Systemic anti-inflammatory agents such as carprofen or meloxicam can also be beneficial.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

If medical management is not successful, then surgical intervention can be considered. Referral to a suitably qualified veterinary ophthalmologist is recommended. If the nasolacrimal duct is patent then a catheter can be sutured in place for 3–4 weeks while continuing with the medical treatment outlined above.

However, if a permanent blockage is present, attempts at removing this can be considered. It should be ascertained that the blockage is due to foreign material or a cystic lesion for example, rather than a neoplastic process, before surgery is undertaken. Magnetic resonance imaging might even be necessary. Surgical approaches include via the nasal chambers or from the lacrimal bone with gentle curettage of the bone over the duct. Clearly these are difficult approaches.

If the duct is totally blocked, but no foreign matter is present and any infection has been fully resolved, the patient will be left with chronic epiphora. This can occur following inflammation of the duct, such that the swelling incurred at the time sticks the duct together (like a straw collapsing on itself and remaining so). Although the permanent epiphora can be worrying for the owner, it rarely is so for the patient. In many cases it can be managed with regular wiping of the serous discharge and general hygiene. However, on occasions, the patient can suffer from serious epiphora such that the skin along the face becomes inflamed and infected with a type of moist dermatitis. In these rare cases it might be necessary to recreate an alternate pathway for tear drainage. Procedures such as a conjunctivorhinostomy or conjunctivobuccostomy, where alternate routes for tear drainage are established to the nasal chambers or mouth respectively, can be undertaken as specialist procedures.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for cases of dacryocystitis will depend upon the inciting cause and the duration of symptoms. Thus a relatively acute inflammation, where the duct is still patent and repeated flushing is possible, carries a good prognosis, providing treatment is continued for long enough. Stopping oral antibiotics too soon can result in recurrence. Clearly if a neoplastic process involving the nasal chambers is present, the prognosis is guarded. As with so many ophthalmic complaints, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment does offer the best outcome. Thus the dog with the purulent discharge which is sent away with inappropriate topical medication could re-present 2 weeks later with a permanently blocked duct, chronic infection and persistent epiphora, while simply flushing the nasolacrimal duct at the initial consultation could have resulted in a complete cure.

The dog presented with a purulent right ocular discharge which had been present for 2 months. The owner was unclear regarding its initial appearance but thought that the eye had been a bit red and weepy for a few days before she took the dog to the veterinary surgeon for an unrelated problem (grass seed in his left ear). The eye then became sticky and the owner mentioned this at the recheck for the ear. Treatment for the presumed conjunctivitis had included two different antibiotic drops and an antibiotic/steroid ointment. Although the eye improved slightly on all of these, within days of stopping the discharge returned as before. The other eye was fine and the dog was very well in himself.

CLINICAL SIGNS

General clinical examination was unremarkable. On ophthalmic examination the right eye had a mucopurulent ocular discharge at the medial canthus and the nictitans membrane was prolapsed and inflamed (see Figure 18.1). No corneal ulceration was noted and the bulbar surface of the third eyelid looked normal. No conjunctival foreign body was noted. Intraocular contents were normal. Fluorescein failed to flow to the nostril on the affected side, but did so rapidly on the normal side.

WORK-UP

A swab was taken for culture and sensitivity testing prior to the instillation of fluorescein dye. After cleaning the discharge away the medial canthus was palpated. The dog showed signs of discomfort when this was done, and more purulent material exited from the lower punctum. General anaesthesia for nasolacrimal flushing was advised – the dog would not tolerate this fully conscious and since the area was painful it was thought that sedation might not be sufficient.

TREATMENT

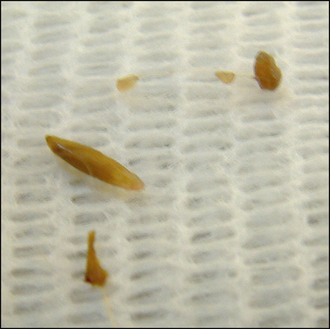

Under general anaesthesia the lower punctum was cannulated but no drainage could be established. The upper punctum was cannulated and copious amounts of purulent material were flushed out from the lower punctum. A swab was taken from this material and this was sent for bacterial culture while the previous swab from the conjunctival discharge was discarded. Small fragments of grass awn were present within the purulent material (Figure 18.4). It was not possible to flush to the nose initially. A piece of monofilament nylon was used as a gentle probe down the ventral nasolacrimal punctum, but this could only be extended 1.5 cm down the duct before stopping. Some bloodstained discharge was produced. The probe was removed and the upper punctum flushed again until only clear fluid drained from the lower punctum.

The patient was recovered from anaesthesia and discharged with oral cefalexin and carprofen, along with topical neomycin, polymyxin B and dexamethasone drops.

Five days later the dog was anaesthetized again and repeated flushing was performed. By this stage the discharge had reduced significantly and it was possible to flush down to the nose although with moderate resistance. No further fragments of plant matter were identified. A moderate grown of mixed bacteria was isolated which were sensitive to the antibiotics prescribed. These were continued for a further 3 weeks (both topically and systemically), together with the carprofen.

OUTCOME

The dog continued to improve. Two weeks later it was possible to flush the nasolacrimal duct under sedation and minimal resistance to this was encountered, with saline appearing at the nostril, but no mucopurulent material. Four weeks after initial presentation treatment was stopped and the dog remained clinically normal.

This case illustrates how grass seeds can become lodged in the nasolacrimal canaliculus and initiate a dacryocystitis. The fact that the dog had a grass seed in the opposite ear at the same time as the eye started to show symptoms should have alerted the veterinary surgeon in attendance that a foreign body could have been present in the eye. This was not looked for (it might have been in the ventral fornix at that stage and only tracked down the duct later, or might have been visible in the punctum). Identification and removal in the first place would have avoided the chronic problem and repeated anaesthesia. Thankfully the grass awn had started to break up and did not proceed down the bony part of the nasolacrimal duct where permanent obstruction is more likely to develop.