37 Canine intraocular neoplasia

PRESENTING SIGNS

Most cases present because the eye has become red or the owner has noticed a change in appearance. Some blepharospasm and ocular discharge might be present but this is not consistent, especially early in the course of the disease. It is more common to encounter unilateral cases, associated with primary intraocular neoplasia, but bilateral cases, normally associated with metastatic disease, do occur. These latter patients are more likely to present with a uveitis rather than just change of appearance, and the patient might be systemically unwell. Such cases are discussed more in the section on uveitis. Thus, in most dogs, there are no other clinical symptoms which the owner has noticed. Sometimes the owner has not been aware of any problem at all and the lesion is identified by the veterinary surgeon during a consultation for something else. Affected dogs are typically 8–10 years and older.

CASE HISTORY

In most cases there is no previous history of ocular disease, or relevant systemic disease.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

Since most cases of intraocular neoplasia will be primary rather than secondary it is likely that the general clinical examination will be normal. Obviously if both eyes are affected or the patient is unwell, then metastatic disease is more likely. However, the majority of cases will be unilateral. As such, the abnormal eye can be compared to the normal one during examination which is helpful.

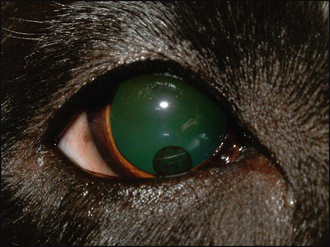

The affected eye might be blind but usually vision is present. Thus a menace response is likely to be normal. Some conjunctival hyperaemia and episcleral congestion might be present but not always. Normally a discoloured lesion will be present. This can be on or in the iris, or behind it poking thorough the pupil. Its colour can vary from dark brown to pale pink and various shades in between (Figure 37.1). The pupil is frequently distorted (dyscoria) but pupillary light reflexes remain. Mild uveitis, with aqueous flare and episcleral congestion, can be present and occasionally the patient is not presented until the eye is painful and enlarged through secondary glaucoma.

Figure 37.1 Ciliary body mass in an elderly Labrador cross. The non-pigmented mass can be seen at 1–3 o’clock behind the pupil. Apart from some dyscoria due to the mass, plus age-related iris atrophy and nuclear sclerosis, the eye is otherwise unremarkable.

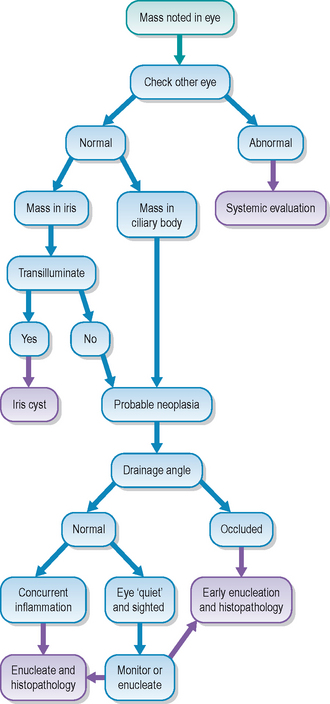

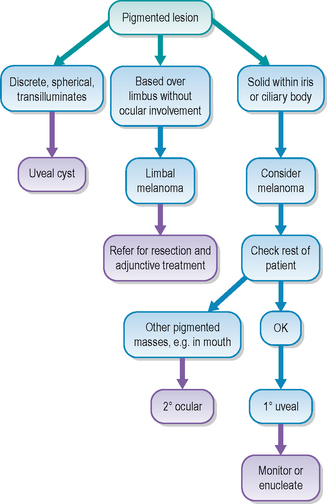

If the neoplasm is based in the iris, then the discolouration will be visible within the iris, and can be raised above it (Figure 37.2). Thus looking at the eye from the side can be useful to determine if the lesion protrudes out from the plane of the iris. Ciliary body-based masses are more difficult to see initially; however, by dilating the pupil the lesion should be more easily visualized through the pupil, especially when looking tangentially across the eye. Vitreal haze is often present with ciliary body neoplasms. Fundus neoplasia is rare but occasionally chor-oidal extension of uveal melanomas does occur.

Figure 37.2 Uveal melanoma in a Labrador. The pigment is close to the iris base and slightly raised above the plane of the iris.

The most commonly encountered uveal tumour in dogs is the iris melanoma/melanocytoma, with ciliary body adenoma/adenocarcinoma the next most frequent. However, many tumour types can occur – haemangiosarcoma, medulloepithelioma, primary lymphoma and so on, and although the clinical examination can suggest the tumour type, it is only on histological examination or cytology that this can be confirmed.

CASE WORK-UP

If an ocular mass is suspected a thorough clinical examination is required to try to establish whether this is primary or secondary. Thus if there are no changes in the fellow eye, nor on general examination, it is appropriate to assume the lesion is primary – especially if it presents as a mass rather than a diffuse uveitis.

Gonioscopy can be useful to determine whether extension into the drainage angle has occurred (which could indicate an increased risk of metastasis as tumour cells escape from the eye into the general circulation). Ocular ultrasonography can be considered but this might not provide further information about the lesion (although it can differentiate a solid mass from a cyst). Chest and abdominal radiography and/or ultrasonography should be undertaken if there is any suspicion of metastatic spread – for example, in advanced cases where there is not only a visible mass but also associated uveitis and secondary glaucoma.

Fine needle aspirates of draining lymph nodes can also be performed should metastatic disease be suspected. However, since many cases of ocular neoplasia in dogs are primary, and metastasis is uncommon, extensive work-up is not usually required unless there is an unusual aspect to the presentation.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Primary ocular neoplasia is not particularly common in dogs, but will be encountered in general practice from time to time, especially in older dogs. Uveal melanomas are the most common neoplasm encountered and normally behave in a benign manner – metastasis is via the bloodstream and occurs in less than 4% of cases. This is different from the situation in cats where malignancy with metastasis is more common. As with most tumours, histological examination can assist prognosis regarding the likelihood of metastasis.

Local extension – through the sclera, into the choroid or even down the optic nerve – is more likely in cases which have not been presented early. It should be remembered that uveal melanomas can occasionally be secondary – metastasis from oral or skin tumours does occur and so if other pigmented lesions are discovered on clinical examination it is probably more likely that the lesion in the eye is secondary to these. Uveal melanomas occur in dogs more frequently than in other domestic species, and darkly pigmented breeds such as the boxer and German shepherd dog are more frequently affected. Lines of Labrador retrievers can also suffer from the condition, suggesting an inherited component in this breed. In addition, affected Labradors are often younger – 3–6 years rather than the 8–10 years normally cited for other breeds. No sex predilection has been demonstrated

The second most common primary intraocular mass derives from the ciliary body – usually adenoma or adenocarcinoma, although medulloepitheliomas, originating from undifferentiated embryonal tissue, are occasionally encountered. Adenoma and adenocarcinoma behave clinically in a similar manner and rarely metastasize, even though the histological appearance may suggest different levels of malignancy. As with the melanoma, the German shepherd dog seems predisposed, and possibly the American cocker spaniel as well, but again, no sex predilection is reported. Older dogs are more frequently affected – 8 years and above most commonly. Most ciliary body neoplasms arise from the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium and are pinkish in colour, but they can develop from the pigmented epithelium and, as such, clinical examination cannot accurately differentiate them from melanoma.

Various other primary intraocular tumours have been reported – haemangioma and leiomyosarcoma for example – but these are extremely rare. Secondary neoplasia is sometimes seen in dogs, and is more often bilateral, presenting as a diffuse uveitis rather than a distinct mass. However, on occasions, a discrete mass will be secondary and emphasizes the importance of histological examination.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

Since most primary intraocular tumours are clinically benign (even if histology shows signs of malignancy), and it is normally older patients that are affected, in some cases a ‘watch and see’ approach is appropriate. If the lesion is causing no discomfort and the eye is sighted, then it can be logical to examine the patient on a regular basis – every 1–2 months for example – and consider enucleation only if the mass starts to enlarge or cause uveitis. In very elderly patients, where the risks of anaesthesia are significant, especially if the dog has other medical problems such as chronic cardiac disease, topical steroids might help if localized inflammation occurs. However, should a secondary glaucoma develop, then enucleation would be recommended. Delaying removal of malignant masses could increase the risk of metastasis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

Enucleation remains the most appropriate treatment for many intraocular neoplasms and if a moderate uveitis or secondary glaucoma has developed it is definitely advised. All globes should be sent for histopathological examination. Sometimes the globe can be salvaged and so if the owner is not willing for enucleation, or if the mass is small and localized, referral should be considered. Small uveal melanomas (such as shown in Figure 37.2) are amenable to laser destruction and the prognosis for such patients is good. Occasionally ciliary body masses can be removed surgically, saving a visual eye.

PROGNOSIS

Generally the prognosis for primary ocular neoplasia in the dog is good, and enucleation is usually curative. However, histological examination of all removed eyes is recommended since the occasional mass is not what it appeared and thus there might be potential repercussions to which the owner should be alerted. Owners are often concerned that the tumour could spread from one eye to the other – this is extremely unlikely if the mass is primary, but can occur in metastatic disease – normally with spread to other tissues as well.

CASE EXAMPLE 37.1 (SEE ALSO CHAPTER 45)

Patient details: Springer spaniel/collie cross, 15 years old, male (entire)

The owner had been aware of problems with the dog’s left eye for many months – it had been cloudy and ‘odd-looking’ but had not caused any discomfort. However, recently the eye had started to bulge and the dog could not see from it. The dog was very elderly and the owner did not want him ‘messed about with’.

CLINICAL SIGNS

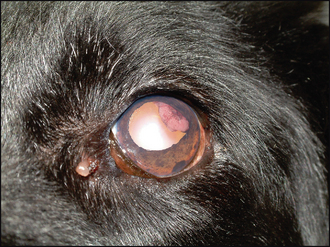

On general clinical examination the dog was underweight, weak on the hind legs and had severe dental disease. He was blind in the left eye with a fixed dilated pupil and no menace response. No consensual pupillary light reflex to the right eye was present. The left globe was enlarged and distorted laterally where a large pigmented mass was visible in the sclera; there was also some corneal pigment dorsolaterally (Figure 37.6). This was seen to be an extension from a large ciliary body mass. The iris was thickened and dark. The lens was cataractous and totally luxated into the anterior chamber with some pigment attached to the lens capsule. No ulceration was noted. Intraocular pressures were 32 mmHg in the left eye and 14 mmHg in the right. Apart from dense nuclear sclerosis the right eye was unremarkable. A ciliary body mass with scleral extension, chronic uveitis and secondary glaucoma was diagnosed.

Figure 37.6 Large episcleral pigmented lesion which is an extension from a ciliary body mass (although from the angle of the photograph this cannot be seen). The globe is enlarged and distorted, chronic uveitis has been present, the lens is luxated into the anterior chamber and is a hypermature cataract and the pupil is widely dilated.

WORK-UP

The owner was advised that enucleation was the best option – the eye was irreparably blind from the glaucoma and although it did not seem particularly painful, it was thought that some discomfort must be present, and which would worsen as the mass continued to enlarge. However, the owner was totally against surgical intervention and did not want the dog’s general deterioration investigated either.

TREATMENT

Medication was started with prednisolone acetate and dorzolamide drops, both three times daily.

OUTCOME

A week later the eye looked unchanged on examination, but intraocular pressure had reduced to 26 mmHg. The owner was happy that the dog was in no discomfort and wanted to continue. The drops were reduced to once daily prednisolone acetate but dorzolamide continued three times daily. The eye remained stable for the following 6 months until the dog went off his hind legs and was euthanized.

This patient was presented very late in the course of the disease and early enucleation could have prevented the secondary glaucoma. However, he was very elderly, and the owner’s reluctance for surgery was understandable – this was one reason for the delay in presentation. It was possible to prevent suffering through ocular discomfort by controlling the glaucoma medically for the dog’s last few months.