45 Secondary canine glaucoma

PRESENTING SIGNS

Most dogs with secondary glaucoma will present with a painful eye and colour change – redness or grey/blueing of the cornea. The owner might or might not be aware of visual impairment in the affected eye. Since the condition is normally unilateral the reduction in vision in the affected eye is not always apparent to owners. The dog can be any breed, including crossbreeds, and is usually middle aged or older. The owner might have noticed the dog rubbing and the eye looking red or simply ‘different’ for days or weeks prior to seeking veterinary advice. The dog might also be slightly ‘depressed’ and quiet. Occasionally the presentation will be very acute, with no previous ocular changes, although this is less common with secondary than with primary glaucoma.

CASE HISTORY

Many dogs will have a history of previous ocular disease, although this is not always the case, and the dog might not have received veterinary treatment despite the owner being aware that there was something ‘not quite right’ with the eye for a while before it became red and painful. The most frequent previous ocular problem will be anterior uveitis – traumatic, immune-mediated or infectious – which responded to treatment initially but on cessation of anti-uveitis medication the eye deteriorated again a few days or weeks later. Sometimes owners will have restarted the previously prescribed medication but this did not improve the eye and so they returned for another examination. The cases with an acute history might be associated with lens luxation, so this should be considered in all terrier breeds (see Chapter 33 on uveitis and Chapter 42 on lens luxation).

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

On general clinical examination the dog might be slightly depressed with a mild pyrexia. It might be head shy and resent examination of the affected eye. A thorough general examination should be undertaken since the ocular problems might be associated with systemic disease (see Chapter 33). The presentation is normally unilateral for secondary glaucoma, but if a bilateral uveitis has been present, then both eyes can develop secondary glaucoma more or less simultaneously.

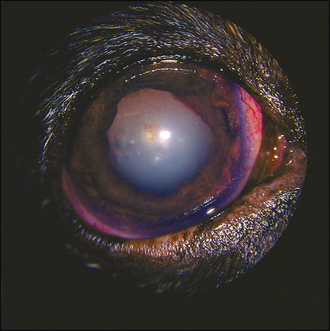

On ocular examination the affected eye might be noticeably enlarged. This is more common in long-standing cases or in younger dogs and puppies where the globe is able to stretch more easily (see Figure 37.5). The eye is likely to be red, with conjunctival hyperaemia and episcleral congestion; some peripheral corneal vascularization (ciliary flush) is also likely to be present. The eye is probably blind with no menace response, and the pupil is normally dilated and unresponsive, although if a previous uveitis has been present the pupil might be miotic, especially if extensive posterior synechiae are present. Alternatively, the pupil might be misshapen (dyscoria) (Figure 45.1). Thus the actual size of the pupil is not always useful in assisting with the diagnosis of secondary glaucoma.

Figure 45.1 Glaucoma secondary to uveitis – note the dyscoria, posterior synechiae, pigment disruption, cataract and episcleral congestion.

The cornea will not be normal. Some corneal oedema is likely, giving a steamy appearance, such that detailed intraocular examination might be difficult. Corneal vascularization, pigmentation and ulceration are all possible (often associated with exposure keratitis). In addition, corneal striae (Haab’s striae; see Figure 44.4) might be present. These appear as a double white line on the cornea, almost like narrow train tracks, and are due to breaks in Descemet’s membrane which form as the globe stretches. If there is any ongoing uveitis, this might manifest as aqueous flare, hypopyon or hyphaema.

Careful examination of the iris is important as neoplasia with a uveal mass is a common cause of secondary glaucoma in older dogs. If a mass is suspected, it is important to look tangentially through the pupil to see if any mass is present in the vitreous extending from the ciliary body – what is visible on the anterior surface of the iris is often just the tip of the iceberg, with a large ciliary body component also present. If fundus examination is possible this is likely to reveal optic disc cupping and possibly some retinal degeneration.

Measurement of intraocular pressure is essential in any suspected cases. Referral should be offered to the client if this is not possible in the practice. Both the absolute reading and the comparison between the two eyes are considered.

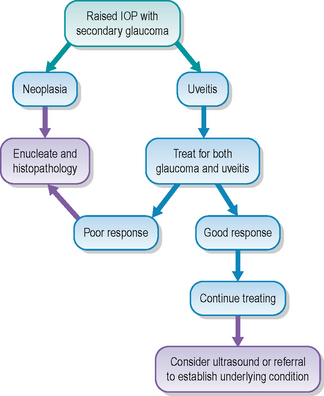

CASE WORK-UP

It is important to try to establish the underlying cause which triggered the secondary glaucoma. If a uveal mass, an anteriorly luxated lens or an intumescent cataract is present, this might be obvious on ophthalmic examination. However, ultrasonography is frequently required since the cornea is often opaque and detailed intraocular examination is thus not possible. In addition to examining for evidence of intraocular neoplasia, the size and position of the lens should be evaluated, the depth of the anterior chamber assessed and the posterior segment checked for evidence of retinal detachment. If there is a history of previous uveitis, this has hopefully been investigated already, and the secondary glaucoma is an unfortunate complication from the uveitis. This is one reason why it is important to accurately diagnose anterior uveitis cases and treat them appropriately – assuming that a ‘red eye’ is purely conjunctivitis, i.e. a superficial disease, can have disastrous consequences. Chest and abdominal radiography together with full haematology and biochemistry are warranted if the cause is not obvious. Many eyes require enucleation and histopathology should always be considered, both for diagnostic and prognostic indicators.

Since dogs with secondary glaucoma will be in some discomfort they should be given suitable analgesics while awaiting decisions on more specific treatment. They should be made as comfortable as possible and be prevented from self-traumatizing. Both topical and systemic medication might be necessary and some dogs will require surgery.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

As with primary glaucoma, most secondary cases develop a raised intraocular pressure through problems with aqueous drainage, rather than due to overproduction. The flow of aqueous can be blocked at the pupil – posterior synechiae, where the iris is stuck on the anterior lens capsule, will cause this if extensive (total posterior synechiae will result in iris bombé, where the whole of the pupil margin is attached to the lens and a forward bowing of the iris results). A lens which is displaced anteriorly – either subluxated or totally luxated – will also result in pupil block, as will an intumescent (swollen) cataract. The sudden onset of total cataract seen in diabetic patients is the most frequently encountered intumescent cataract and can lead to secondary glaucoma, often exacerbated by lens-induced uveitis. Checking the depth of the anterior chamber can help to determine if the lens is swollen or shifted forwards, although ultrasonography can be more revealing. Pupil block can also occur with displaced vitreous – again associated with lens luxation/subluxation or following cataract extraction surgery.

The other area where aqueous flow is impeded is at the drainage angle. Forward movement of the iris will result in closure of the angle and occurs with intumescent cataracts, subluxated lenses and uveal neoplasia. Blockage of the angle with inflammatory, pigment or neoplastic cells, with red blood cells in cases of hyphaema, or with vitreous is also encountered, while both anterior uveitis and neoplasia can result in neovascularization of the anterior iris face (pre-iridal fibrovascular membrane formation) and this can also restrict aqueous drainage. Occasionally glaucoma can develop secondary to perforating injuries, where the iris moves anteriorly to plug the defect and the resultant anterior synechiae disrupt aqueous flow. However, the uveitis and sequelae of that are usually more to blame than the actual position on the iris in these cases.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

Medical management of secondary glaucoma is directed towards treatment of the underlying cause as well as the raised intraocular pressure. However, many cases are not responsive to medical management and enucleation is frequently required. Moderately raised intraocular pressures associated with primary uveitis are worth treating medically, with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors topically and both topical and systemic anti-inflammatory agents – typically steroids but sometimes NSAIDs. Prostaglandin analogues and miotic agents such as pilocarpine are both contraindicated in cases of secondary glaucoma associated with an inflammatory process. As the uveitis settles the pressure will come down, providing there is not excessive damage at the drainage angle. Frequent rechecks are necessary and life-long medication can be required.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

In a blind, painful glaucomatous eye enucleation should be considered regardless of the cause. Sometimes it is not possible to determine the cause until histopathology is performed. Cases of uveal neoplasia which have resulted in secondary glaucoma should be enucleated, as should any eye with a very high pressure which does not respond to medication. If an acute lens luxation is the reason for the raised pressure, then lendectomy may be beneficial, and early referral for this is advised (see Chapter 42). Other surgical procedures for glaucoma such as drainage implants and laser ablation of the ciliary body are usually disappointing in secondary cases.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for the affected eye with secondary glaucoma is unfortunately poor, and most cases do end up with the eye being removed sooner or later. Acute lens luxation with emergency lendectomy is the only real exception to this, although even here the prognosis remains guarded with respect to a return of vision. However, the prognosis for the patient as a whole is normally good. Most cases of primary intraocular neoplasia in the dog do not metastasize (although survey radiography and ultrasonography are still advised, and histopathology should always be performed). Uveitis due to trauma with secondary glaucoma similarly should be cured on enucleation.

The patient had been treated for non-responsive conjunctivitis for several months before the owners changed veterinary surgeons. The dog had received several different antibiotic agents topically plus steroid drops, none of which made much difference. The owner changed practices when she noticed that the dog started bumping into things. The eyes were both still red, but the owner was not aware of any other changes to the eyes. However, the dog did have its fur covering the eyes most of the time and the owner had not looked closely!

CLINICAL SIGNS

The dog was clinically well with only ocular abnormalities. A menace response was present in the left eye but not the right. Pupillary light reflexes were poor. Dazzle reflexes were present in both eyes. Marked episcleral congestion was present along with patches of episcleral pigment. Corneal pigment was also noted and both irises were very dark. The pupils were irregular and dilated. Pigment was present on the anterior lens capsules. The left lens was subluxated. Asteroid hyalosis was noted bilaterally (Figure 45.3). Fundus examination showed cupping of both optic discs, with some retinal vessel attenuation in the right. No ulceration was present. Intraocular pressures were 48 mmHg in the right eye and 40 mmHg in the left.

WORK-UP

The clinical examination led to the diagnosis of glaucoma secondary to pigment dispersal syndrome and no further work-up was performed. The owners had this dog’s sister. They were not concerned about her eyes at all but examination revealed mild pigment changes and early glaucoma in her as well.

TREATMENT

Treatment was started with brinzolamide (Azopt, Alcon) three times daily bilaterally and dexamethasone (Maxidex, Alcon) twice daily bilaterally. The dog did not appear in pain so no analgesia was given.

OUTCOME

Intraocular pressures reduced to the mid 30s in both eyes and some improvement in vision was noted in the left eye, although the right remained blind. After 3 months of treatment the dog developed a corneal ulcer in the right eye. This did not improve on topical anti-biotics and intraocular pressure increased to 48 mmHg again. Enucleation of the right eye was performed 1 month later. Histopathology confirmed severe pigment proliferation and secondary glaucoma. The left eye maintained limited vision and no further increases in intraocular pressure for another 3 months, although further pigment deposition occurred. The dog continues to be monitored.

This case was misdiagnosed as conjunctivitis for several months prior to the correct diagnosis being reached. Pigment dispersal syndrome is a recognized breed-related problem and Cairn terriers are particularly susceptible. Treatment aims to reduce the inflammation associated with pigment deposition and reduce intra-ocular pressure, but unfortunately nothing has been discovered which will reduce the relentless pigment accumulation. Surgical treatment with drainage implants or laser ablation of the ciliary body are disappointing. However, if this dog had been correctly diagnosed in the first place the prognosis for saving vision for a much longer period would certainly have been better.