43 Glaucoma – introduction

Glaucoma is the term given to the group of diseases in which a raised intraocular pressure leads to damage to the optic nerve and the retinal cells. It is a painful, often blinding, condition and is a very serious disease which can be difficult to treat. There are many causes of glaucoma and the choice of treatment often depends on the cause, the duration of the disease and the potential visual outcome.

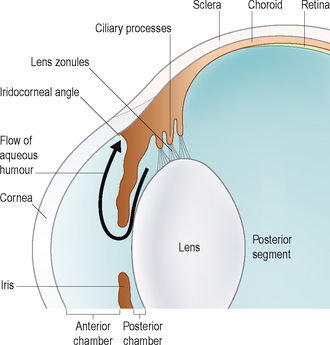

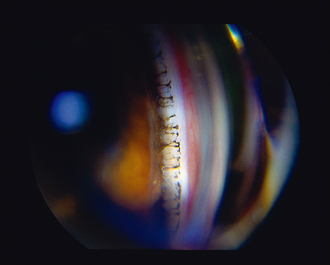

The maintenance of normal intraocular pressure depends on a balance between production and drainage of aqueous humour. The ciliary body produces aqueous from the posterior non-pigmented epithelial cells by a process of both active secretion and passive ultrafiltration, and it flows through the pupil into the anterior chamber. It drains out of the eye through the iridocorneal angle (drainage or filtration angle). This pathway is shown in Figure 43.1. Once in the drainage angle, the aqueous passes through the pectinate ligaments and into the uveal trabecular meshwork where it is absorbed into the venous plexus vessels and out into the episcleral and scleral drainage veins (Figure 43.2). There is a second route of aqueous drainage – the uveoscleral or unconventional pathway. Here aqueous is drained via the ciliary body interstitial cells into the suprachoroidal space and choroidal and scleral vessels. The percentage of aqueous following this alternative pathway varies between species – it is more important in the horse than in dogs for example.

Figure 43.2 Drainage angle as seen on gonioscopy – the pectinate ligaments can be clearly seen spanning the angle.

Most cases of glaucoma result from impaired drainage rather than from overproduction. Tonometry, the measurement of intraocular pressure, is essential for the diagnosis and management of glaucoma. Normal intraocular pressures are listed in Table 43.1. Without the appropriate instruments to do this, it is impossible to diagnose and treat successfully, and therefore referral to an ophthalmologist is advised should a tonometer (Schiotz, Tonopen or TonoVet) not be available in the surgery. Since glaucoma is such a common ophthalmic problem, representing approximately 10% of ocular problems in one survey, it is strongly recommended that each veterinary practice has access to tonometry. In addition to measuring the intraocular pressure, gonioscopy – the examination of the iridocorneal (drainage) angle – is frequently necessary. The techniques for both tonometry and gonioscopy are discussed in Chapter 1. The latter technique requires practice to master and so is not routinely performed in general practice.

Table 43.1 Normal intraocular pressures in dogs, cats and rabbits

| Dog | Cat | Rabbit |

|---|---|---|

| 15–25 mmHg | 16–27 mmHg | 16–20 mmHg |

The clinical signs of glaucoma will vary depending on the species of animal, the cause, the speed of onset and the duration, together with how high the intraocular pressure has become. For ease of description the signs are usually divided into those seen with acute glaucoma and those in chronic cases – these are listed in Table 43.2. In general terms, the condition usually presents unilaterally and acute onset is common in dogs. Cats more frequently suffer from a chronic insidious onset. In dogs, pain, corneal oedema, episcleral congestion and blindness are the most consistent presenting signs whereas in cats it might just be a dilated pupil which is noted.

Table 43.2 Clinical signs of glaucoma

| Acute glaucoma | Chronic glaucoma |

|---|---|

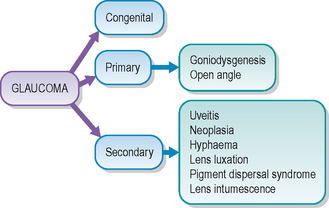

The causes of glaucoma are broadly divided into primary and secondary (see Figure 43.3). Congenital glaucoma is also encountered albeit rarely. Primary glaucoma usually involves goniodysgenesis – an abnormality of the drainage angle which is visible on gonioscopy. It is a bilateral, but not usually symmetrical, disease and there can be a delay of weeks to years before the second eye is affected. It is discussed in the following section. Secondary glaucoma is more commonly encountered in dogs and cats, as well as in horses. It develops due to some other ocular abnormality leading to problems with the circulation and drainage of aqueous humour – for example, at the pupil due to adhesions between the iris and lens, or due to a tumour blocking the drainage angle – more details follow in Chapter 45.

TREATMENT OF GLAUCOMA

The treatment of glaucoma can be medical or surgical and often a combination of both is required. Clearly the underlying cause needs to be determined since this will influence the choice of treatment. If the glaucoma is secondary to an intraocular mass, then enucleation is the treatment of choice, while primary glaucoma is more amenable to medical or surgical management. The aim of treatment is to lower the intraocular pressure to a level which is comfortable and does not promote further optic nerve or retinal damage. If the eye is still visual, or has the potential for a return of some vision, then this is also a major aim – to prevent deterioration in eyesight. Unfortunately, many eyes will be irreparably blind on presentation. If the cause is primary glaucoma, then treatment must be targeted to prevent the same outcome for the second eye.

Emergency treatment for glaucoma should be considered in all acutely presented cases regardless of cause. Alleviation of the pain associated with the elevated intraocular pressure will give time for further investigation such that a long-term management plan can be devised. Osmotic diuretics such as mannitol solution are given intravenously. Care must be taken to ensure that renal function is adequate before using these agents since they can trigger renal failure in compromised patients. The pressure-lowering effect of osmotic diuretics is only short lived, and so a longer term treatment plan involving medication or surgery must be arranged.

In addition to lowering the pressure, specific pain relief should be provided, e.g. with opiates or NSAIDs. Long-term medication usually involves the use of topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as dorzolamide (Trusopt, MSD) and brinzolamide (Azopt, Allergan). These lower intraocular pressure by reducing the production of aqueous humour at the ciliary body. Topical prostaglandin analogues such as latanoprost (Xalatan, Pharmacia & Upjohn) are used for primary glaucoma but should not be used if uveitis is present. They work by improving the outflow of aqueous, and are often used in conjunction with the topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Other agents such as miotics and beta-adrenergic blockers are also sometimes prescribed (see Table 43.3).

Table 43.3 Medical treatment of glaucoma

| Emergency treatment | Long-term treatment |

|---|---|

| Mannitol – 10–20% solution by intravenous infusion over 20–30 minutes | Topical anhydrase inhibitor, e.g. dorzolamide (Trusopt MSD) |

| Analgesia – systemic NSAID or opiate | Topical prostaglandin analogue, e.g. latanoprost (Xalatan, Pharmacia & Upjohn) |

| Paracentesis (removal of a small volume of aqueous) | Topical miotic, e.g. pilocarpine |

| Systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, e.g. acetazolamide occasionally used | Topical beta-adrenergic blockers, e.g. timolol |

Surgery for glaucoma can include procedures to reduce the production of aqueous such as laser and cryosurgery (cyclophotocoagulation and cyclocryotherapy, respectively) and procedures to increase outflow which involve either drainage implant surgery or scleral trephination and peripheral iridectomy. Clearly these are specialist procedures and referral is required to assess whether a patient might be suitable. Unfortunately, enucleation is frequently necessary, particularly if the eye is blind and painful.