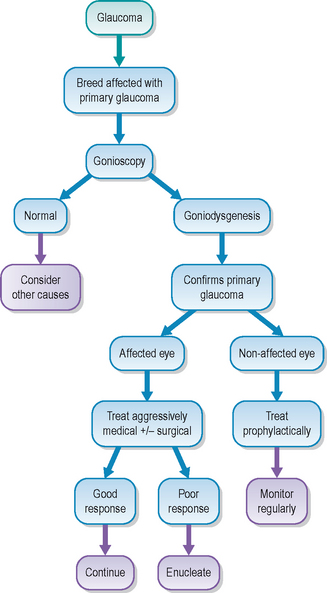

44 Primary canine glaucoma

PRESENTING SIGNS

Dogs with primary glaucoma will be presented with a painful, cloudy eye. Increased lacrimation is normally present as well. Owners might be aware of visual loss in the affected eye, but frequently this is not something which they have noticed. The patient is likely to be depressed and may be inappetant. In addition, the owner might report seeing their pet make attempts at rubbing or hiding their face. The presenting signs normally develop very quickly. Affected animals are usually pedigree dogs, and aged 5–8 years, although some breeds develop primary glaucoma at a younger age – discussed in more detail later.

CASE HISTORY

In most cases there is no previous history of ocular disease or relevant systemic disease. Indeed, the patient is usually completely normal one day, then suddenly develops a very sore, cloudy eye – perhaps noticed when the owner gets up or when they come in from work. Occasionally there is a history of some intermittent slight clouding and redness on a few occasions which settled before the owner became particularly worried, but this is the exception rather than the rule.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

General clinical examination is unremarkable, although a mild, pain-induced pyrexia is sometimes present. The dog might resent examination of the face and the affected eye can be difficult to examine due to the severe blepharospasm. However, with patience, gentle handling, and the use of topical anaesthesia if necessary, a rewarding ophthalmic examination should be possible.

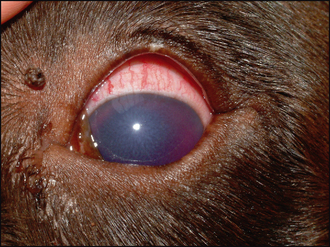

The affected eye is likely to be blind, or with severely reduced vision, demonstrated by a reduced or absent menace response. Corneal oedema will manifest as a blue–grey corneal discolouration. In addition to the clouding, the eye will also be red – episcleral congestion is usually marked and peripheral corneal vascularization develops which manifests as a red fringe around the limbus (ciliary flush) (Figure 44.1). The pupil can be assessed using a bright light source and is usually mid sized or dilated with very limited constriction when illuminated. A dazzle reflex remains if the pressure has not got too high. The indirect or consensual pupillary light reflex should be assessed and this can help with the prognosis regarding any return of vision – if there is no constriction of the fellow pupil there is less chance of a return of any useful eyesight in the affected eye.

Figure 44.1 Primary glaucoma showing severe corneal oedema and episcleral congestion. The pupil is mid-dilated. Intraocular pressure was 38 mmHg.

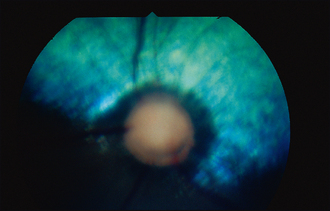

Detailed intraocular examination is hampered by the corneal oedema but the use of indirect ophthalmoscopy will be more informative than direct ophthalmoscopy since it provides better imaging through semi-opaque media. Thus, on fundus examination, cupping of the optic disc might be appreciated – seen as a small, dark disc with the blood vessels seeming to dip down into it from the retina (Figure 44.2). Peripapillary retinal degeneration is sometimes seen, along with more widespread hyper-reflectivity and blood vessel attenuation in advanced cases.

Figure 44.2 Optic disc cupping. The canine optic disc is small and round, with the blood vessels appearing to dip down into it.

Measurement of intraocular pressure is essential to reach a definitive diagnosis, to provide prognostic advice, to draw up a treatment plan and to monitor the effectiveness of the treatment. Without tonometry it is very difficult to assess the patient properly. If a tonometer is not available, then referral for pressure measurement should be considered. The technique for tonometry, using a Schiotz tonometer, Tonopen or TonoVet, is detailed in Chapter 1. Remember that there are several factors which can affect the intraocular pressure readings (Table 44.1).

Table 44.1 Factors that can affect intraocular pressure (IOP) readings

| Factor | Effect |

|---|---|

| Breed | Higher in terriers and fluctuates more in these breeds as well |

| Age | Decreases with age |

| Degree of restraint required | Pressure around the neck will result in higher readings |

| Position of head | Higher with the head back and elevated |

| Instrument used | Slight variations between types of tonometer |

| Amount of pressure used to measure IOP | Pressure on the globe (including the forced lid opening required to access the cornea) will increase readings |

CASE WORK-UP

Measurement of the intraocular pressure will give the diagnosis of glaucoma but does not tell us the cause for the raised pressure. Primary glaucoma develops in the absence of other intraocular disease and is an inherited condition in several breeds of dog. Goniodysgenesis, or malformation of the drainage angle, is the most frequent cause of acute primary glaucoma in dogs, and is a bilateral condition (although usually presented as a unilateral problem). Thus it is necessary to evaluate the contralateral eye. Gonioscopy is the examination of the drainage angle and referral for this procedure should be considered in all dogs which present with acute glaucoma. It is rarely possible to perform gonioscopy on the affected eye (due to the corneal oedema, peripheral corneal vascularization and pain for example) but examination of the fellow eye will reveal evidence of goniodysgenesis and thus the second eye is also at risk from the development of glaucoma.

Other tests which can be performed as part of the case work-up include ultrasonography. This will allow detailed visualization of intraocular structures despite the opaque ocular media and can help to differentiate primary from secondary glaucoma. For example, an iridal mass or lens luxation could be detected, which would suggest that the raised intraocular pressure developed secondary to other intraocular disease. Ultrasonography can also allow measurement of the globe diameter to determine if it has been stretched and enlarged (hydro-phthalmos) as a result of the increased pressure.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Primary glaucoma is most commonly associated with goniodysgenesis but a second category, open-angle glaucoma, also occurs. Goniodysgenesis is considered inherited in several breeds, as listed above. The exact relationship between the abnormal drainage angle and the development of glaucoma is unknown. Indeed, some dogs with severely malformed iridocorneal angles do not develop glaucoma at all, while others with relatively mild changes can have severe disease in one or both eyes. If gonioscopy reveals an abnormal angle, then the animal is certainly at a higher risk from developing glaucoma than the general population, but unfortunately at present we cannot quantify this risk. The glaucoma seen with goniodysgenesis is acute and serious. The dog exhibits a sudden onset, red, cloudy, painful, often blind eye and intraocular pressure measurement is mandatory in any of the breeds listed above which present with these signs. Screening programmes, such as the British Veterinary Association/Kennel Club/International Sheep Dog Society (BVA/KC/ISDS) eye scheme, provide gonioscopy to breeders and it is recommended that dogs affected with goniodysgenesis are removed from breeding circles.

Primary open-angle glaucoma is less common, but can be encountered in the Norwegian elkhound and beagle. Here the condition is slow in onset and vision can be maintained until quite late in the course of the disease. The increase in intraocular pressure is gradual and the eye can tolerate these changes with less pain and globe damage than with goniodysgenesis. Thus patients are presented late in the course of the disease, with visual loss, dilated pupils and enlarged globes as the most notable symptoms.

General nursing to make the patient comfortable and prevent self-trauma is required, along with the application of various topical (and sometimes also systemic) medications.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

The medical treatment for acute primary glaucoma is divided into emergency treatment and long-term control (see Table 43.3 for summary). Only once the pressure has been reduced and stabilized should the long-term management be considered. Most medical approaches to treatment involve expensive topical agents and owners must be able to administer these effectively and should be aware of the ongoing costs of treatment.

Pain relief should be a priority in acute glaucoma. Systemic NSAIDs in combination with an opiate are most frequently administered.

Traditionally the emergency treatment for reducing intraocular pressure has relied on osmotic diuretic drugs such as mannitol. Given intravenously this will draw fluid from the aqueous and vitreous into the extracellular space. Renal function should be assessed prior to its use since it can lead to kidney failure in compromised patients. Mannitol is given at a dose of 1–2 g/kg over 20 minutes, and a 20% solution is usually administered. This will result in a reliable reduction of intraocular pressure which lasts for about 6 hours. This provides time for the other pressure-lowering drugs to take effect. Clearly tonometry should be performed regularly (e.g. hourly) following the administration of mannitol. Gly-cerol is another hyperosmotic agent that can be given orally but can induce vomiting and is not used as frequently as mannitol.

Another emergency treatment which is gaining favour is the use of topical prostaglandin analogues such as latanoprost and travoprost. These reduce intraocular pressure in 15–30 minutes and the reduction will last up to 12–24 hours.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are routinely used for both emergency and maintenance treatment of primary glaucoma. Topical agents have largely superseded the systemic preparations. Dorzolamide and brinzolamide are most widely used, although several other products are becoming available, some combined with beta-blocking drugs (which are effective in human patients but less so in our species).

The long-term medical treatment of primary glaucoma in dogs usually involves a topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (e.g. dorzolamide three times daily) plus a prostaglandin analogue (e.g. latanoprost once daily in the evening). The carbonic anhydrase inhibitor reduces the production of aqueous while the prostaglandin analogue improves its drainage and the drugs work synergistically. Topical beta-blocking agents are widely available, and although they can reduce intraocular pressure by a small amount in our patients, they are certainly far less effective in cases with goniodys-genesis than in the cases of open-angle glaucoma which are frequently encountered in human ophthalmology.

Treatment of the second eye is frequently undertaken, although this will not prevent the eye developing full-blown glaucoma. However, it might provide some protection during the insidious pressure spikes which are known to occur before the eye develops sustained elevated intraocular pressure. Typical prophylactic treatment would be a twice daily topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

Surgical options for primary glaucoma include globe-saving procedures or enucleation. The former include techniques for reducing the production of aqueous, such as cyclophotocoagulation (laser ablation of the ciliary body) and cyclocryoablation (cryosurgery to freeze and destroy the ciliary body epithelium), together with techniques involving drainage implants to redirect aqueous outflow. Sometimes more than one procedure is combined. Newer techniques such as ciliary body endo-laser show promise, but their cost and availability are limiting factors. Clearly referral is required for all of these techniques.

In cases of severe glaucoma, where the eye is blind and painful, enucleation is frequently necessary and owners report that the dog is much happier and more playful and so on after the surgery, indicating that chronic pain was present prior to globe removal. Histopathological examination of enucleated globes should always be considered to confirm the diagnosis of primary glaucoma. The use of intrascleral prosthetics is becoming a more popular alternative to enucleation. Here the contents of the globe are removed (evisceration), leaving the sclera and corneal shell, and a silicone ball is placed into the empty globe. This can provide a more cosmetically acceptable appearance to the owners, but the procedure carries no benefit to the patient whatsoever and has the potential to cause problems such as corneal ulceration and extrusion of the implant. As such, the ethics of performing what is essentially cosmetic surgery for the benefit of the owner should be questioned.

PROGNOSIS

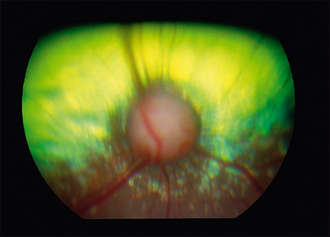

The prognosis for primary glaucoma is always guarded, both in terms of saving vision and in saving the eye. Owners should be aware from the start that the condition has the potential for both eyes to become affected and that blindness can be total. Often the first eye to become affected is permanently blinded, even if the owners present the dog quickly. The damage caused by the sudden rise in intraocular pressure can be severe and thus the aim with the first eye is often to keep the patient comfortable. The acute episode will become chronic, and other ocular changes such as globe enlargement (hydrophthalmos), corneal striae (breaks in Descemet’s membrane, also called Haab’s striae), corneal ulceration and pigmentation from exposure keratitis, secondary lens luxation and so on can all develop (Figure 44.4). Some globes eventually become phthitic and then non-painful but it can take several years for this to occur. Many globes are ultimately enucleated.

Figure 44.4 Chronic glaucoma showing corneal striae (Haab’s striae), some corneal pigmentation and episcleral congestion. Intraocular pressure was 32 mmHg.

Once gonioscopy has been performed and it is established that the second eye is at risk from developing full-blown glaucoma, efforts should be made to reduce this risk. Prophylactic medication can delay the onset of glaucoma but we cannot predict which patients will benefit from prophylactic medication. Some dogs will never develop glaucoma despite goniodysgenesis, and thus the use of topical beta-blockers or carbonic anhydrase inhibitors prophylactically is an expensive waste of time. However, since the condition is so severe, the use of such drugs can probably be justified. They will ‘buy some time’ and provide some protection should the pressure suddenly rise. Owners should be educated to check their pet themselves and to bring it for regular ophthalmic examinations which include tonometry. They should check the pupil and look for any ocular redness (episcleral congestion) or subtle corneal oedema.

Many cases of primary glaucoma have wide variations in intraocular pressure with high pressure spikes prior to the onset of full-blown glaucoma, and observant owners can detect these. Regular ophthalmic examinations might reveal areas of retinal infarction or early optic disc cupping which resulted from short pressure spikes. These findings would indicate that the patient is starting with glaucoma and aggressive medical management or surgical intervention is warranted at this stage. With early diagnosis and thorough treatment the prognosis can be improved slightly, but the condition is still a very serious one which we are not able to manage particularly well. Prevention, by screening at-risk breeds with gonioscopy and removing affected animals from breeding pools, is to be encouraged.

The dog was presented with sudden onset pain, redness and clouding of the left eye. The owner was a breeder and was aware of glaucoma in the breed, but had not had her dogs examined under the BVA/KC/ISDS eye scheme. However, she was worried that this could be what was wrong with the dog and presented him to the surgery quickly. With hindsight she did concede that the eye had been a bit red and watery several times over the previous 2 months but she had not been worried at that stage.

CLINICAL SIGNS

On general examination the dog was subdued and head shy on the affected side but otherwise in good condition. The left eye was uncomfortable. No menace response was noted. There was marked episcleral congestion but only mild corneal haze. The pupil was dilated and unresponsive although a consensual response to the fellow eye was present. A reduced dazzle reflex was noted. Fundus examination revealed a very small, pale optic disc and some vascular attenuation (Figure 44.5). Intraocular pressures were 46 mmHg in the left eye and 18 mmHg in the right, which was ophthalmoscopically normal. Thus glaucoma was diagnosed, and assumed to be primary.

WORK-UP

Gonioscopy was performed on the right eye. This revealed a very narrow drainage angle, with sheets of tissue spanning it rather than discrete pectinate ligaments. This confirmed goniodysgenesis as the cause for the primary glaucoma.

TREATMENT

The left eye was treated topically with four times daily dorzolamide and twice daily latanoprost. Twice daily dorzolamide was also started in the right eye. The dog was given an injection of buprenorphine initially followed by oral carprofen.

OUTCOME

The intraocular pressure reduced to 32 mmHg 4 hours after initiating treatment and the patient was comfortable, albeit still blind in the left eye. Over the following 3 weeks the pressure varied between 28 and 42 mmHg despite continued medication. The owner decided that, since no vision had returned even when the pressure was lower, enucleation would be best for the dog. This was performed a month following diagnosis and certainly he was much more comfortable afterwards. The right eye was monitored on a monthly basis and the owner was fully aware that glaucoma could develop at any time. She diligently checked the eye and was prepared for surgery (probably laser rather than a drainage implant) as soon as either the pressure was above 25 mmHg or any evidence of optic disc or retinal disease was noted on the monthly check-ups. Early surgical intervention does offer the best prognosis but most ophthalmologists will not intervene until some indication of glaucoma has developed – each surgical technique carries the risk of complication (including blindness) and therefore is not usually undertaken prophylactically.

The dog had been used at stud. The owner had two of his offspring and both were found to have goniodysgenesis. The breed club arranged a testing session at one of their dog shows and any dogs which were affected with goniodysgenesis were not used for further breeding.

This case illustrates that, even with early diagnosis, the prognosis for the first eye is frequently hopeless. However, the second eye does have a better chance of remaining visual and pain free for some time, although even with aggressive intervention blindness can ensue. The incidence of this debilitating disease can be reduced with selective breeding.