36 The Limbs of the Pig

The principal distinguishing features of the limb skeleton of the pig are the well-developed, weight-bearing ulnae and fibulae and the complete metapodial and phalangeal complements in the paired accessory digits (Figures 36–1 and 36–4), even though these fail to make contact with firm ground. It will also be recalled that very few pigs live long enough to attain skeletal maturity.

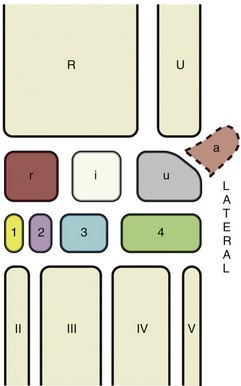

Figure 36–1 The bones of the carpal skeleton in the pig. Roman numerals identify the metacarpal bones, Arabic numerals, the distal carpal bones. R, Radius; U, ulna; a, accessory carpal bone; i, intermediate carpal bone; r, radial carpal bone; u, ulnar carpal bone.

The hoofs resemble those of cattle and have a soft digital pad, or bulb, that is well demarcated from the wall and sole (Figure 36–2). The short life span and the common practice of running pigs on concrete make hoof trimming rarely necessary.

Figure 36–2 A, Palmar surface of the foot of a pig. 1, Bulb (digital pad) of hoof; 2, sole of hoof; 3, wall of hoof; 4, hoof of accessory digit. B, Lateral view of foot of a pig.

The limbs of pigs received little veterinary attention before it was recognized that articular disease (especially osteochondrosis) was relatively common; this stimulated a belated interest in the anatomy of the major joints and in the development of appropriate procedures for their injection. The causation of much articular pathology is uncertain, but suspicion attaches to the demand for rapid weight gain beyond the ability of the immature skeleton to provide adequate support, resulting in articular cartilage breakdown and bone deformities. The use of concrete flooring may also be a factor.

THE FORELIMB

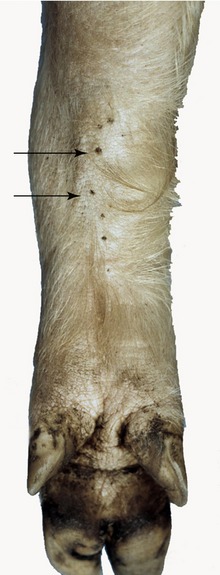

Skeletal features that may be identified on palpation include the cranial and caudal angles and the tubercle on the spine of the scapula; the caudal part of the greater tubercle of the humerus; the medial and lateral condyles of the humerus and the olecranon at the elbow; and the accessory carpal, revealing the level of the proximal row of carpal bones (see Figure 32–1). Soft tissue structures that may be identified include the cephalic vein on the cranial aspect of the arm (not always visible but possibly available for puncture) and the skin glands at the caudomedial aspect of the carpus (Figure 36–3).

THE SHOULDER JOINT

The large cranial part of the greater tubercle deflects the intertubercular groove medially and, with it, the biceps tendon. Even so, it is the smaller caudal part of the tubercle that is palpable, together with the infraspinatus tendon approaching it. Intraarticular injection is made at the cranial border of the tendon, immediately proximal to the bone.

THE ELBOW JOINT

The lateral epicondyle of the humerus is accentuated by the sharp crest presented by its caudal border. Insertion of the needle for puncture is made just caudal to this crest, between it and the ulna. In an alternative method that uses the same landmark the needle is entered at a site 2 or 3 cm proximal to the previous one and is directed mediodistally to pierce the capsule within the olecranon fossa.

THE CARPAL JOINT

This exceptionally moveable joint (Figure 36–1) permits almost 180° of flexion. The accessory carpal bone reveals the locations of the two more proximal compartments of the joint; these are in communication with each other and thus allow a single injection to reach both. Entry is made to either side of the extensor carpi radialis tendon, which is readily identified.

No features of the limb arteries demand notice. Lymph originating from superficial structures of the arm and forearm passes to the ventral superficial cervical nodes. That from deeper structures and from the entire distal part of the limb goes to the axillary lymph nodes of the first rib (cranial to the first rib and ventral to the axillary vessels).

THE HINDLIMB

Palpable skeletal features of this limb include the coxal tuber (a slight enlargement at the ventral end of the iliac crest) and the ischial tuber (lateral to the vulva in the female); the greater trochanter of the femur (less readily palpated as it is more deeply placed); the patella, single patellar ligament, the crest and extensor groove of the tibia, and the collateral ligaments, at the stifle; the entire medial surface of the tibia in the leg; and the calcaneus and calcaneal tendon and the medial and lateral malleoli (and adjacent part of the fibula) at the hock (Figure 32–1). The use of the hamstring muscles for intramuscular injection is contraindicated because of the risks of an adverse effect on the quality of the ham and because of injury to the sciatic nerve.

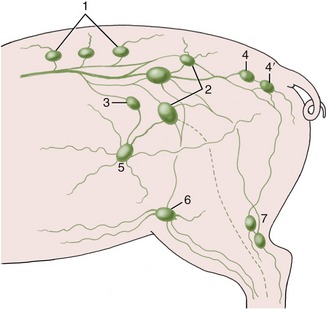

It is usually impossible to find the subiliac lymph nodes (Figure 36–5/5) located at the cranial border of the thigh, but the popliteal nodes (Figure 36–5/7) may often be palpated, depending on how deeply they lie within the popliteal fossa.

THE HIP JOINT

Because of its deep situation, the available landmarks are at some distance from this joint. Depending on the size of the pig, the greater trochanter is located from 2 to 4 cm ventral to the line joining the coxal with the lateral part of the ischial tuber. The needle is inserted at the same distance cranial to the trochanter and passed, at right angles to the skin, through the gluteal muscles to enter the dorsal part of the joint. The greater resistance offered by the fibrous tissue of the deep gluteal muscle and the joint capsule warns that the cavity is close.

THE STIFLE JOINT

The three compartments of this joint communicate, which allows a single injection to reach all parts (see the dog in Figure 2–63 for the general idea). The puncture is made lateral to the patellar ligament, about one third of the distance down from the patella to the tibial tuberosity.

THE HOCK JOINT

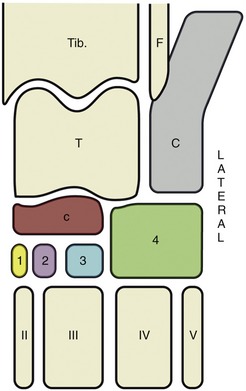

The tarsocrural and proximal intertarsal joints, the only joint compartments at the hock accessible for injection, do not communicate. Two sites are available for injection of the tarsocrural joint, both on the lateral side: one is dorsal and the other is plantar to the collateral ligament. The proximal intertarsal joint is entered from the medial side, plantar to the collateral ligament. There are two independent joint spaces at the tarsometatarsal level: one is proximal to metatarsals II and III, and the other is proximal to metatarsals IV and V. The first of these communicates with the distal intertarsal joint (Figure 36–4).

Figure 36–4 The bones of the tarsal skeleton in the pig, schematic. Roman numerals identify the metatarsal bones, Arabic numerals the distal tarsal bones. Tib., Tibia; F, fibula; T, talus; C, calcaneus; c, central tarsal bone.

No account will be given of the arteries of the limb. Lymph from superficial structures of the thigh and leg drains to the superficial inguinal and subiliac nodes (Figure 36–5); that from deeper parts travels in lymphatic vessels that run with the major arteries to reach the medial iliac nodes. Lymph from the distal part of the limb drains to the popliteal nodes. Some efferents from these nodes proceed to the gluteal and ischial nodes on the lateral surface of the sacrosciatic ligament; others join the lymphatics running to the medial iliac nodes.