CHAPTER 47 Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease

Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) is characterized by one or more of the following clinical signs: pollakiuria, hematuria, dysuria-stranguria, inappropriate urination, and partial or complete urethral obstruction. These clinical signs have historically been termed feline urologic syndrome; however, this syndrome is not a single disease entity. The definition of the syndrome has varied among studies and authors, and it is difficult to interpret the literature without a broader definition that includes all disorders associated with FLUTD.

FLUTD has been reported to occur in 0.34% to 0.64% of all cats, and it is thought to be the reason for 4% to 10% of all feline admissions to veterinary hospitals. It appears to be equally prevalent in male and female cats, although overweight cats are thought to be at higher risk for FLUTD. Indoor cats are also reported to be more predisposed to FLUTD than outdoor cats; however, because the urination habits of indoor cats are more closely observed than those of outdoor cats, this may be an observational difference. Most feline lower urinary tract disorders occur in cats between 2 and 6 years of age, with a higher prevalence in the winter and spring months. Between 30% and 70% of cats that have one episode of FLUTD will have a recurrence.

The reported mortality rates for cats with FLUTD range from 6% to 36%. Hyperkalemia and uremia are major causes of death in male cats with urethral obstruction; however, some cats with recurrent FLUTD are euthanized because their owners are unwilling to incur the expense of repeated treatment, diagnostics, or hospitalization necessary to relieve urethral obstruction. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) secondary to ascending pyelonephritis is a possible long-term sequela or complication of FLUTD, especially if there have been repeated urethral catheterizations.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

FLUTD can be divided into two broad categories according to the presence or absence of an identifiable cause of the urinary tract disease. Uroliths, urinary tract infection (UTI), anatomic abnormalities (e.g., urachal remanants, urethral strictures), trauma, irritant cystitis, neurologic disorders, behavioral abnormalities, and neoplasia can all cause or mimic FLUTD. In many cases, despite a thorough diagnostic evaluation, the cause of FLUTD remains unknown and is classified as idiopathic.

Uroliths.

FLUTD may occur in association with uroliths, microcalculi, and/or crystal-containing mucous urethral plugs. Struvite and calcium oxalate are the most common feline uroliths. As with canine urolithiasis, there must be a sufficiently high concentration of urolith-forming constituents in the urine, a favorable pH, and adequate time in the urinary tract for crystals/uroliths to form.

Approximately 45% of the uroliths in cats consist either entirely or predominantly of struvite. Most struvite uroliths form in the urinary bladder of young cats, and in contrast to dogs, most feline struvite uroliths form in sterile urine. When a bacterial infection is present, the most common organism is a urease-producing Staphylococcus sp. Tamm-Horsfall mucoprotein, secreted by the renal tubules, is the major protein found in feline struvite uroliths. It may also play a role in the pathogenesis of urethral plugs that may contain struvite crystals.

Urethral obstruction is more common in the male cat; the length and diameter of the urethra play a relevant role in this. Many obstructions are caused by mucus- and/or struvite-containing plugs that lodge in the penile urethra. Uroliths may lodge in any portion of the urethra, including sections proximal to fibrous connective tissue strictures resulting from previous injuries. Local inflammation that develops in response to urethral calculi or plugs may exacerbate the obstruction by causing urethral edema. Iatrogenic trauma created by urethral catheterization may also cause urethritis or inflammation of the periurethral tissue, leading to urethral compression.

In addition to struvite uroliths, other types of uroliths, including calcium oxalate and urate stones, can cause signs of FLUTD. Calcium oxalate uroliths account for approximately 45% of feline uroliths, and urate uroliths constitute approximately 5%. According to one study, Burmese, Persian, and Himalayan cats may be at higher risk for calcium oxalate urolithiasis. Calcium oxalate uroliths are also more common in neutered male cats than in female cats, their prevalence is higher in older animals, and they occur more frequently in the kidneys than struvite uroliths do. Calcium oxalate uroliths are becoming more prevalent in cats, and this may be related to the widespread use of acidifying diets designed to prevent struvite-related FLUTD. Epidemiologic studies indicate that cats fed diets low in sodium or potassium or formulated to maximize urine acidity have an increased risk of developing calcium oxalate uroliths but a decreased risk of developing struvite uroliths. Another retrospective study suggested that feeding cats urine-acidifying diets, feeding cats a single brand of cat food, and maintaining cats in an indoor-only environment were factors associated with the development of calcium oxalate urolithiasis. The increase in prevalence of calcium oxalate uroliths in cats may also correlate with the observation that cats are living longer lives than they were 10 to 15 years ago. Finally, because the prevalence of calcium oxalate uroliths is also increasing in people and dogs, there may be unidentified environmental factors common to all three species influencing the development of these uroliths.

Urinary tract infection.

A primary bacterial infection of the feline urinary tract, although rare in young cats compared with dogs, may also cause the clinical signs observed in FLUTD. Usually, UTI will occur secondary to altered normal host defense mechanisms that allow bacteria to colonize the bladder or urethra. Complete voiding (bladder content washout) is a major host defense mechanism against bacterial infection. Therefore anatomic abnormalities, partial obstructions, or detrusor atony that may interfere with normal voiding can result in an increased urine residual volume. Chronic inflammation of the urinary bladder with fibrosis and thickening of the bladder wall may also cause decreased detrusor tone and incomplete voiding. Perhaps the most important factor predisposing to the development of a secondary bacterial cystitis in association with FLUTD is urethral catheterization (especially placement of indwelling urinary catheters) combined with fluid therapy and the formation of dilute urine that has decreased antibacterial properties.

From time to time, researchers have implicated viruses, including feline calicivirus, bovine herpesvirus 4, and feline syncytia-forming virus, in the pathogenesis of FLUTD. The finding of bovine herpesvirus 4 antibodies in cats and the detection of calicivirus-like particles in the crystalline-mucous urethral plugs of male cats have sparked renewed interest in the possibility of a viral component in the syndrome (Osborne et al., 1999). Whether viruses play a major role remains to be determined.

Miscellaneous causes of feline lower urinary tract disease.

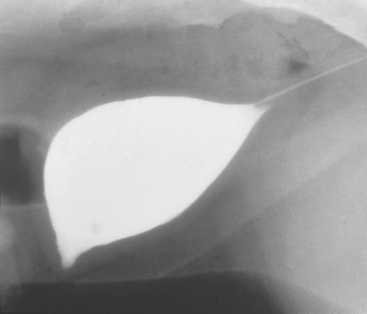

In previous studies of cats with naturally occurring FLUTD, approximately 25% had vesicourachal diverticuli (Fig. 47-1). These may be congenital or acquired; the acquired diverticuli are observed primarily in cats older than 1 year, with a mean age of 3.7 years. Male cats are twice as likely to acquire the abnormality as female cats, and increased intravesical pressure and bladder inflammation during urethral obstruction may play a major role in its pathogenesis. Although a urachal diverticulum may be an incidental finding in an asymptomatic cat, hematuria and dysuria are frequently noted clinical signs. Vesicourachal diverticuli are currently thought to develop secondary to FLUTD and increased intravesical pressure and are not thought to be a major initiating factor.

Idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease.

In large retrospective studies of cats with FLUTD conducted at the University of Minnesota and Ohio State University, a cause could not be found in 54% and 79% of the cats, respectively. Researchers at Ohio State University have found numerous similarities between cats with idiopathic FLUTD and women with interstitial cystitis. These similarities include chronic irritative voiding patterns, sterile urine, a prominent bladder mucosal vascularity with spontaneous hemorrhages observed during cystoscopy, decreased mucosal production of glycosaminoglycan, and increased numbers of mast cells and sensory afferent neurons in bladder mucosal biopsy samples. The cause of interstitial cystitis in women is also unknown. A decreased urine volume and decreased frequency of urination may facilitate the development of FLUTD. Possible causes of a decreased urine volume and frequency of urination include a dirty or poorly available litter box; decreased physical activity as a result of cold weather, castration, obesity, illness, or confinement; and decreased water consumption because of water taste, availability, or temperature. Stress may also contribute to the development of the clinical signs of urinary tract disease. Increased plasma concentrations of noradrenaline have been documented in cats with idiopathic FLUTD. Increased noradrenaline could increase uroepithelial permeability, increase nociceptive nerve fiber (C-fiber) activity, and activate neurogenic bladder inflammatory responses. Furthermore, decreased cortisol concentrations have been observed when corticotropin-releasing factor and adrenocorticotropic hormone concentrations are increased in cats with idiopathic FLUTD, indicating the possibility of reduced adrenocortical reserve. Although the role of stress is difficult to prove, it is often implicated; the history provided by owners frequently points to a recent association with boarding, cat shows, a new pet or baby in the home, a vacation, or cold or rainy weather. Additional stressors in multiple cat households may include intercat aggression brought on by competition for access to water, food, litter boxes, and space.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The clinical signs of FLUTD depend on the component of the disease complex present (Box 47-1). Unobstructed cats usually have pollakiuria, dysuria-stranguria, and microscopic or gross hematuria, and they urinate in inappropriate places, often in a bathtub or sink (see also Chapter 41). These clinical signs may be readily apparent in cats that live indoors but may be missed in cats that live primarily outdoors.

BOX 47-1 Clinical Signs Associated with Lower Urinary Tract Inflammation in Cats

BOX 47-1 Clinical Signs Associated with Lower Urinary Tract Inflammation in Cats

In male cats with urinary obstruction, the presenting signs depend on the duration of the obstruction. Within 6 to 24 hours, most obstructed cats will make frequent attempts to urinate, pace, vocalize, hide under beds or behind couches, lick their genitalia, and display anxiety. If the obstruction is not relieved within 36 to 48 hours, clinical signs characteristic of postrenal azotemia, including anorexia, vomiting, dehydration, depression, weakness, collapse, stupor, hypothermia, acidosis with hyperventilation, bradycardia, and sudden death, may occur.

On physical examination an unobstructed cat will be apparently healthy, except for a small, easily expressed bladder. The bladder wall may also be thickened. Abdominal palpation may be painful for the unobstructed cat; however, the obstructed cat always resents manipulation of the caudal area of the abdomen. The most relevant finding during physical examination of an obstructed cat is a turgid, distended bladder that is difficult or impossible to express. Care should be exercised when manipulating the distended bladder, however, because the wall has been injured by the increased intravesical pressure and is susceptible to rupture. In the cat with urethral obstruction, the penis may be congested and protrude from the prepuce. Occasionally, a urethral plug is observed to extend from the urethral orifice; in some cases the cat may lick its penis until it becomes excoriated and bleeds.

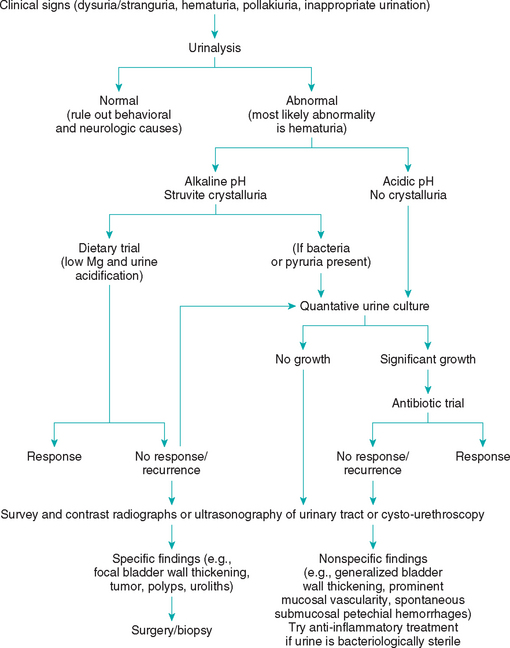

The diagnosis of urethral obstruction is usually straightforward and is based on historical and physical examination findings. In unobstructed cats with FLUTD, urinalysis usually reveals hematuria; if not, behavioral causes of abnormal urination should be considered (Box 47-2 and Fig. 47-2). Struvite-associated disease is likely in cats in which the initial urine pH is alkaline and struvite crystals are observed in the urine sediment. Radiography or ultrasonography and urine cultures should be employed to rule out or identify overt urolithiasis and a urinary tract infection in cats with suspected struvite-associated disease, especially if there is no response to a magnesium-restricted, acidifying diet (see Fig. 47-2 and the section on management). In cats with FLUTD that have acidic urine, radiography or ultrasonography can help identify or rule out anatomic abnormalities (e.g., thickened bladder wall, polyps, tumors, nonstruvite-associated urolithiasis). Cystoscopy is also a valuable tool in cats with FLUTD. Nonspecific cystoscopic findings include prominent mucosal vascularity and submucosal petechial hemorrhages. Radiography (plain and double-contrast–enhanced cystography), ultrasonography, or cystoscopy and urine culture should be performed in all cats with recurrent FLUTD.

BOX 47-2 Diagnostic and Therapeutic Plan for Cats with Lower Urinary Tract Inflammation

BOX 47-2 Diagnostic and Therapeutic Plan for Cats with Lower Urinary Tract Inflammation

IV, Intravenous; FLUTD, feline lower urinary tract disease.

Management

Unobstructed cats.

The nature of the treatment for FLUTD depends on the clinical signs at presentation (see Box 47-2 and Fig. 47-2). Unobstructed cats with dysuria-stranguria and hematuria will often become asymptomatic within 5 to 7 days of presentation whether therapy is instituted or not. Many cats are treated with antibiotics, and if clinical signs abate, a cause-and-effect relationship is often established in the minds of the clinician and cat owner. The clinician should remember, however, that more than 95% of young cats with FLUTD have sterile urine and that the same results could be obtained by treating with numerous placebos.

If the initial urinalysis reveals an alkaline urine with struvite crystalluria, imaging of the urinary tract to rule out struvite uroliths is indicated. Urine culture and sensitivity tests should be performed if pyuria or bacteriuria is observed in the urine sediment, and appropriate antibiotics should be administered if urine cultures are positive. Cystocentesis is the ideal way to obtain urine for bacterial culture; if urine is obtained by any other method, a quantitative urine culture should be performed. Several sources of fresh water should be made available to the cat. The litter boxes should also be cleaned frequently and placed in convenient locations.

Hill’s Feline Prescription Diet s/d can be used to effectively dissolve struvite uroliths. It takes an average of 36 days for sterile struvite uroliths to dissolve, whereas struvite uroliths associated with urease-producing bacterial infections in cats take an average of 79 days to dissolve. Antibiotic treatment in cats with struvite urolithiasis and a concurrent bacterial urinary tract infection should be determined on the basis of urine culture and sensitivity results and continued throughout the period of dissolution. The diet should be fed for 30 days beyond the point when the uroliths are no longer visible in radiographs.

If struvite crystalluria and alkaline urine recur repeatedly in cats with previous struvite uroliths, longer-term dietary therapy is warranted. Examples of diets that can be used to treat struvite-associated FLUTD as well as prevent recurrence include Hill’s Feline Prescription Diet c/d (canned or dry), Science Diet Feline Maintenance (canned or dry), Iams pH/S, Purina UR–Formula Feline Diet, and Waltham Veterinarium Feline Control pHormula Diet. The composition of many over-the-counter cat foods is not constant; therefore it is difficult to make recommendations regarding their use. Ideally, the urine pH, measured 4 to 8 hours after feeding, should be maintained between 6.2 and 6.4. The aforementioned prescription diets are metabolized to form acid ions, which are excreted in the urine; it is rare, therefore, for these prescription diets not to maintain an acidic urine in cats. A urease-producing bacterial infection and dietary indiscretion should be identified or ruled out if alkaline urine is found to persist during dietary therapy.

In most cases of FLUTD, the urine is acidic and no struvite crystals are observed; therefore magnesium-restricted, acidifying diets are not recommended. In cats with persistent or recurrent clinical signs, a urine sample should be obtained by cystocentesis for urine culture, and plain abdominal radiography or ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced radiographic studies of the bladder and urethra, or cystoscopy should be performed to identify or rule out anatomic abnormalities if the urine is bacteriologically sterile (see Box 47-2 and Fig. 47-2). Numerous agents, including antibiotics, tranquilizers, anticholinergics, analgesics, antispasmodics, glycosaminoglycans, amitriptyline, and antiinflammatory drugs (e.g., dimethylsulfoxide, glucocorticoids, and nonsteroidal antiinflammmatory drugs [NSAIDs]), have been recommended for the treatment of FLUTD in cats; however, no controlled studies have demonstrated the efficacy of any of these agents. Oxybutynin and propantheline are antispasmodic drugs that may alleviate pollakiuria in some cats, and buprenophine (0.005 to 0.01 mg/kg administered intravenously or intramuscularly q4-8h) or butorphanol (0.2 to 0.8 mg/kg administered intravenously or subcutaneously q2-6h or 1.5 mg/kg administered orally q4-8h) can be used as an analgesic. It must be kept in mind that in controlled studies, more than 70% of cats with idiopathic FLUTD have appeared to respond to placebo treatments (e.g., lactose, wheat flour).

In cats that will accept the change, switching from a dry diet to a canned diet to help increase water intake and decrease urine concentration is often associated with improvement. Decreasing stress and improving quality of life may also be very important factors in the management of cats with idiopathic FLUTD. Increasing the number of litter boxes and keeping them clean may help decrease stress in multiple cat households. Similarly, providing access to several sources of fresh food and water may help. Cats may also benefit from increased play activities and increased access to private space. Finally, pheromone therapy (Feliway CEVA Animal Health, Libourne, France) may produce a calming effect and help reduce stress.

Obstructed cats.

In cats with a urethral obstruction, the relative urgency for relieving the obstruction depends on the physical status of the cat. Cats that are alert and not azotemic may be sedated for urethral catheterization without further diagnostic tests or treatment; however, in a depressed cat with urethral obstruction, the serum potassium concentration should be measured in-house or an electrocardiograph rhythm strip should be evaluated to assess the degree of hyperkalemia (see Box 46-1) and an intravenous (IV) catheter should be placed for the administration of normal (0.9%) saline solution before establishing urethral patency. If the electrocardiogram or blood tests confirm the presence of hyperkalemia, the cat should be treated aggressively to decrease serum potassium concentrations or counteract the effects of hyperkalemia on cardiac conduction (see Box 46-1).

The degree of restraint required for urethral catheterization depends on the cat’s temperament and physical status. Physical restraint in a towel or cat bag, with or without the topical application of lidocaine, may be all that is required in a severely depressed cat. In cats requiring more restraint, ketamine HCl (1 to 2 mg/kg administered intravenously), an ultra–short-acting barbiturate (IV thiamylal sodium or thiopental sodium, 1 mg/kg titrated to effect), or propofol 6.6 mg/kg administered IV slowly over 60 seconds) may be used to effect. Because ketamine is eliminated by the kidneys, low IV doses (10 to 20 mg total) are frequently adequate for restraint. The administration of additional doses of ketamine should be avoided in severely azotemic cats.

A urethral obstruction may be relieved in some cases by penile massage and gentle expression of the bladder. If this does not result in urine flow, palpation of the urethra per rectum may dislodge a urethral plug or calculus. Sterile isotonic saline solution, administered through well-lubricated catheters or cannulas, should be used to hydropulse urethral plugs into the bladder. A variety of cannulas and catheters may be used for this purpose; however, nonmetal catheters with smooth, open ends are preferred to prevent iatrogenic damage to the urethral mucosa. Use of a strict aseptic technique is essential to prevent bacterial UTIs. If catheterizing the bladder proves difficult, cystocentesis with a 22-gauge or small needle may be performed to decrease the intravesical pressure and allow for the urethral obstruction to be backflushed into the bladder.

Indications for the placement of indwelling urinary catheters in male cats with obstructions that have just been relieved include the following: (1) an inability to restore a normal urine stream, (2) an abundance of debris that cannot be extracted via repeated bladder lavage, (3) evidence of detrusor atony in cats that cannot be manually expressed four to six times per day, or (4) intensive care of critically ill animals in which urine formation is being monitored as a guide to fluid therapy requirements. When an indwelling urinary catheter is necessary, again, strict aseptic technique should be used during placement. A soft red rubber feeding tube (3F to 5F) should be used; placing the feeding tube in the freezer for 30 minutes before use facilitates its passage. The catheter should be inserted only as far as the neck of the bladder; catheter passage should be stopped as soon as urine can be aspirated from the catheter. A closed urine-collection system should be used, and the catheter should be sutured to the prepuce and left in place for as short a time as possible (2 to 3 days is the average). An Elizabethan collar or tape hobbles are needed to prevent the cat from chewing out the sutures and removing the catheter. Phenoxybenzamine or prazosin treatment is often initiated at this time to decrease urethral spasms that can be stimulated by the indwelling catheter. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment is not recommended; however, the urine sediment should be examined daily for bacteria and white blood cells, and the urine cultured if necessary. Secondary bacterial UTIs are common in cats with indwelling urinary catheters receiving IV fluids to promote diuresis.

The degree of postrenal azotemia should be assessed by measuring the serum urea nitrogen, creatinine, and potassium concentrations. IV fluid therapy is indicated, especially in cats with azotemia. Maintenance therapy (approximately 60 to 70 ml/kg/day) and replacement therapy (percentage of dehydration × body weight [in kilograms] = liters to administer) should be administered intravenously over 24 hours. The subcutaneous administration of a balanced electrolyte solution is an acceptable mode of fluid therapy in some cats once the initial uremic crisis is under control. Measurement of the urine volume every 4 to 8 hours will facilitate the administration of correct replacement therapy. A large-volume, postobstructive diuresis may develop in some cats, and IV fluid replacement therapy is essential in these animals. Serum urea nitrogen, creatinine, and serum electrolyte concentrations should be reassessed as needed, depending on the degree of azotemia and the response to treatment, to ensure the adequate recovery of renal function. Occasionally, hypokalemia occurs in a cat with a prolonged and severe diuresis. In addition, if severe hematuria persists, the hematocrit should be monitored once or twice daily.

Detrusor atony is fairly common in cats obstructed for more than 24 hours and is associated with bladder overdistention. If the bladder can be expressed four to six times per day, an indwelling catheter may not be necessary. If the bladder cannot be expressed at least four times per day, an indwelling catheter is indicated. Bethanechol (2.5 mg q8h administered orally) may be administered to stimulate detrusor contractility only after the finding of a wide urine stream or the placement of an indwelling urinary catheter has confirmed that the urethra is patent. Acepromazine and phenoxybenzamine can significantly lower intraurethral pressures in anesthetized, healthy, intact male cats, and therefore these drugs may also be helpful in the management of a functional urethral obstruction in cats with FLUTD.

Perineal urethrostomy is rarely required for the emergency relief of a urethral obstruction. If the obstruction cannot be relieved by medical means, the condition of uremic cats must be stabilized before surgery is performed. Repeated cystocentesis should be done to keep the bladder empty until hyperkalemia, acidosis, and uremia resolve. Elective perineal urethrostomies are occasionally advisable in male cats with recurrent obstructions to decrease the likelihood of death from postrenal azotemia. However, a perineal urethrostomy does not decrease the risk of recurrence of clinical signs of cystitis, and it has been documented that cats with cystitis that undergo perineal urethrostomies are more susceptible to bacterial UTIs.

Probably the most important aspect of long-term patient monitoring is ensuring that the owner recognizes both the significance and the clinical signs of urethral obstruction. Owners of male cats with urinary obstruction must be warned of the risks of reobstruction, especially during the first 24 to 48 hours after the relief of an obstruction or the removal of an indwelling urinary catheter. Allowing the owner to palpate the distended bladder during the initial examination is a good way to teach him or her how to differentiate pollakiuria, dysuria-stranguria, and an obstruction. Any straining in the litter box should be cause for alarm in a male cat with a history of urethral obstruction, and careful observation for continued voiding of urine is essential for the early detection of a recurrence.

Follow-up urinalysis and urine culture should be performed 5 to 7 days after catheterization in all cats that have been catheterized to relieve a urethral obstruction. Because normal host defenses are bypassed when a catheter is introduced into the bladder, UTIs are common after catheterization, especially if an indwelling urinary catheter has been used. A follow-up urinalysis and urine culture should also be performed in all cats receiving corticosteroids because these may decrease immune system function (and decrease inflammation-related changes in the urine sediment) and predispose cats to the development of bacterial UTIs. Ascend ing pyelonephritis is a significant concern in cats with any UTI, and it is a potential complication of FLUTD, especially if corticosteroids are used. Urethral obstruction caused by struvite uroliths or struvite-containing mucous plugs should be managed with dietary treatment designed to either dissolve the urolith or prevent recurrence, as previously described. Periodic urinalyses to measure pH are beneficial in cats with struvite-associated disease being managed by diet to prevent recurrent episodes. The urine pH 4 to 8 hours after eating should be 6.4 or less. Yearly urinalysis and bacterial culture are especially important in cats with perineal urethrostomies because the normal host defense mechanisms of the lower urethra have been surgically removed in these cats.

The prognosis for male cats with recurrent urethral obstruction is guarded, and perineal urethrostomy should be considered, especially if the second obstruction occurs during medical management designed to prevent recurrence. The prognosis for cats with recurrent nonobstructed FLUTD is fair to good, inasmuch as this syndrome is rarely life-threatening. Pyelonephritis, renal urolithiasis, and CKD are potential sequelae of recurrent nonobstructed FLUTD.

Bartges JW, et al. Bacterial urinary tract infection in cats. In: Bonagura JD, editor. Current veterinary therapy XIII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000.

Buffington CAT, et al. Clinical evaluation of cats with nonobstructive urinary tract diseases. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1997;210:46.

Buffington CAT, et al. Feline interstitial cystitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;215:682.

Buffington CAT, et al. CVT update: idiopathic (interstitial) cystitis in cats. In: Bonagura JD, editor. Current veterinary therapy XIII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000.

Buffington CAT, Chew DJ. Management of non-obstructive idiopathic/interstitial cystitis in cats. In Elliott JA, Grauer GF, editors: BSAVA manual of canine and feline nephrology and urology, ed 2, Gloucester, England: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2007.

Kruger JM, et al. Nonobstructive idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease: therapeutic rights and wrongs. In: Bonagura JD, editor. Current veterinary therapy XIII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000.

Kruger JM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of short-term amitripyline administration for treatment of acute, nonobstructive, idiopathic lower urinary tract disease in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222:749.

Lekcharoensuk C, et al. Association between dietary factors and calcium oxalate and magnesium ammonium phosphate urolithiasis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219:1228.

Lekcharoensuk C, et al. Epidemiologic study of risk factors for lower urinary tract disease in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;218:1429.

Osborne CA, et al. Feline urologic syndrome, feline lower urinary tract disease, feline interstitial cystitis: what’s in a name? J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;214:1470.

Westropp JL, et al. Feline lower urinary tract disease. In Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors: Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, ed 6, St Louis: Elsevier/Saunders, 2005.