CHAPTER 62 Disorders of the Prostate Gland

OVERVIEW OF PROSTATIC DISEASE

Disorders of the prostate gland are common in dogs but very rare in cats. They include benign prostatic hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia, bacterial prostatitis, prostatic abscess, prostatic and paraprostatic cysts, and prostatic neoplasia. Clinical signs of prostatic diseases are similar because each causes some degree of prostatic enlargement or inflammation (Box 62-1). The most common clinical signs include tenesmus, blood dripping from the urethra independent of urination, and recurrent urinary tract infections. Blood is usually found in the urine and semen from dogs with prostatic disease. Additional, nonspecific signs, such as fever, malaise, and caudal abdominal pain, are often present in dogs with bacterial infections and neoplasia of the prostate gland. Prostatic adenocarcinoma may cause an animal’s gait to be abnormal as a result of pelvic and lumbar vertebral metastatic lesions. Less commonly, prostatic diseases may cause urethral obstruction, infertility, or urinary incontinence.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF THE PROSTATE GLAND

A complete physical examination is performed. Palpation is done to assess the size, shape, symmetry, and consistency of the prostate as well as to detect any discomfort. This is accomplished by both abdominal and rectal palpation. The enlarged prostate is rarely located completely within the pelvic canal. There is a positive correlation between prostatic size and age and also body weight. The clinical signs and physical findings will usually localize the disease process to the prostate gland, but they are not able to differentiate among the various prostatic conditions.

Diagnostic imaging, prostatic cytologic studies, bacterial culture, biopsy, or a combination of these studies is usually required to differentiate the specific prostatic disorders. Culture results from normal prostatic fluid should yield less than 100 colony forming units (CFUs)/ml. Abdominal radiographs help define the size, shape, and position of the prostate. Prostatic length of greater than 70% of the distance from the sacral promontory to the pelvic brim on the lateral abdominal radiograph is indicative of prostatomegaly. The radiographic appearance of the sublumbar lymph nodes, lumbar vertebrae, and bony pelvis should be examined for evidence of metastasis. A positive-contrast cystourethrogram can be performed if it is difficult to differentiate an abnormal prostate from the urinary bladder and to assess the prostatic urethra. Ultrasonography provides additional information about the homogeneity of the prostatic parenchyma, the urethral diameter, and the diffuse or focal nature of the disease (Fig. 62-1). The finding of urethral invasion or destruction during diagnostic imaging is highly suggestive of prostatic neoplasia. As can be seen from the similarities of the figures in this chapter, radiographic and ultrasonographic findings do not differentiate cysts from abscesses or hyperplasia from metaplasia, prostatitis, or diffuse neoplasia.

FIG 62-1 Sonogram of normal canine prostate (arrows) of an English Setter. Hatch marks represent 1 cm.

Prostatic material for cytologic and microbiologic examination can be obtained by several methods. The rationale for prostatic massage or brush techniques is that material from the prostate may be recovered via the urethra. The accuracy of the results will depend on whether the prostatic lesion communicates in some way with the urethra. Prostatic massage is performed by placing a urethral catheter and removing urine from the bladder. An aliquot of urine is saved for future comparison. The catheter is then withdrawn to the level of the prostate, as determined by rectal palpation; the prostate is thoroughly massaged by way of the rectum; and additional material is aspirated through the catheter. The prostatic urethra can be lavaged with sterile saline solution if an inadequate volume is recovered. The premassage and postmassage specimens are analyzed and compared. A urethral brush may also be used to obtain material for cytologic and microbiologic evaluation. In this method the brush is passed through a urinary catheter to the level of the prostate, as determined by rectal palpation. The prostatic urethra is then “brushed.”

Prostatic massage is easily performed. There is a risk of rupturing prostatic abscesses or liberating septic emboli during massage. Because prostatic fluid normally refluxes into the urinary bladder, urinary tract infection is usually present whenever there is bacterial prostatitis. Conversely, urinary tract infection can exist in the absence of prostatitis. If a urinary tract infection is present, microbiologic and cytologic examination of the prostatic portion (third fraction) of the ejaculate to confirm the presence of bacterial prostatitis is more accurate than examination of specimens obtained by massage. Neoplastic cells may not be recovered in specimens obtained by prostatic massage or brush unless there is urethral invasion.

Fine-needle aspiration is an excellent method to obtain prostatic specimens for cytology and culture. Fine-needle aspiration is usually performed percutaneously, preferably with ultrasound guidance. A transrectal approach for fine-needle aspiration has also been described. The percutaneous approach is generally safe and simple if a careful technique, especially with ultrasound guidance, is used. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate can also be performed. Prostatic biopsy is also performed via a celiotomy. After prostatic biopsy there may be mild, transient hematuria that resolves spontaneously.

BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the most common prostatic disorder in the dog. Some degree of BPH is found in most intact male dogs older than 6 years of age. It occurs as a result of androgenic stimulation. Specifically, it is mediated by dihydrotestosterone, which causes symmetric prostatic growth. Why some males are affected and others are not is unknown. BPH is often a subclinical incidental finding on routine examination of older dogs. When clinical signs are present, the most common are tenesmus and prostatic bleeding reflected by blood dripping from the urethra in the absence of urination. This bleeding may be exacerbated by sexual arousal. Macroscopic or microscopic hematuria and hemospermia may also be found (see Box 62-1). Contrary to the situation in men, urine retention is a rare manifestation of BPH in dogs.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of BPH is suggested when tenesmus, a sanguineous urethral discharge, hematuria, or a combination of these is found in an otherwise healthy, middle-aged or older, intact dog with symmetric prostatomegaly. Less commonly, dogs with BPH may be evaluated because of blood in the semen. The prostate gland is not painful when palpated. Radiologic studies confirm the presence of prostatomegaly (Fig. 62-2, A). Ultrasound studies should show diffuse, relatively symmetric involvement throughout the prostate (Figs. 62-2, B, and 62-3). Small, multiple, diffuse, cystic structures are commonly seen on ultrasound images obtained in dogs with BPH. Initially, prostatic enlargement is due primarily to glandular hyperplasia. This progresses to cystic hyperplasia. Cytologic examination reveals evidence of hemorrhage and perhaps mild inflammation but no evidence of sepsis or neoplasia. The diagnosis of BPH could be confirmed by histopathologic studies of biopsy specimens, in which hyperplastic changes, often with microscopic cysts, are found; however, biopsy is rarely necessary.

Treatment

Treatment is not necessary for asymptomatic BPH, but castration is the treatment of choice for dogs showing clinical signs of BPH. Prostatic involution is usually evident within a few weeks of castration and is complete by 12 weeks after the source of androgens is removed. Prostatic bleeding usually resolves in about 4 weeks. Castration may not be a feasible treatment option for breeding males. Such animals can be treated with antiandrogens, but this is not as effective as castration in resolution of the clinical signs, and the results are temporary. However, it may be many months before signs recur. In addition to castration or antiandrogen therapy, cysts can be treated by fine-needle aspiration under ultrasound guidance. The fluid should be submitted for bacterial culture because many cultures are found to be positive for bacteria (see later discussion of chronic bacterial prostatitis).

When castration is not a desirable option, antiandrogenic drugs may be considered. Estrogen therapy to reduce prostatic hyperplasia, although initially effective, is not recommended because estrogens can induce squamous metaplasia of the prostate, enhance the cystic changes within the prostate, and depress spermatogenesis. The dose-dependent and idiosyncratic toxic effect of estrogens on canine bone marrow is well known.

Progestins have antiandrogenic effects. At high doses they suppress spermatogenesis and spermatozoal motility, increase morphologic defects in spermatozoa, and suppress serum testosterone concentrations, despite having no apparent effect on serum luteinizing hormone (LH) concentrations. Progestins reportedly also have no apparent effect on libido in dogs, despite the fact that they suppress serum testosterone concentrations. Megestrol acetate at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg orally, q24h for 10 days to 4 weeks, has been reported to cause the clinical signs of BPH to resolve without adverse effects on fertility in dogs, but its long-term use has not been evaluated. Delmadinone acetate is another progestin that is used to treat BPH. It is administered at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg subcutaneously at weeks 0, 1, and 4. This causes adrenal suppression for up to 21 days after the last dose but no changes in glucose tolerance or growth hormone. It is not as effective as castration in resolving prostatic bleeding. A single subcutaneous injection of 3 mg/kg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) relieves the clinical signs of BPH for 10 to 24 months in most dogs treated (84%). Although serum testosterone concentrations were decreased after week 5, there were no apparent problems with semen quality or libido. The effects of progestins on adrenal function, growth hormone secretion, and insulin and glucose homeostasis (see Chapter 56) should be considered.

Finasteride (Proscar®; Propecia®; Merck) inhibits 5-α-reductase, thereby inhibiting the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone. It is not labeled for use in dogs. Doses of 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg q24h, or 5 mg/dog/day, orally have been studied. Relative to body weight, these doses are much higher than the 5 mg/day recommended for men with BPH. Treatment is continued for several months. Clinical signs begin to improve after 1 week of treatment. Prostatic size is demonstrably and significantly decreased by 8 weeks of treatment because of atrophy of the prostatic epithelium and fibromuscular stroma. Prostatic fluid volume will decrease; otherwise, there is no apparent effect on semen quality. Libido and ejaculation are unaffected. Serum testosterone concentration was unchanged, but serum dihydrotestosterone concentrations were significantly decreased. Although the changes induced by finasteride are reversed by 6 months after the termination of treatment, the prostate gland does not necessarily return to pretreatment sizes. At the 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg doses, adverse effects were not reported. Finasteride is teratogenic. Therefore pregnant women must not handle the drug.

The concept of immunizing dogs against gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) or LH has appeal for the treatment of BPH. Because GnRH and LH control gonadal function, blocking them would theoretically suppress testosterone production, which in turn would diminish dihydrotestosterone and prostate size. These effects might be maintained permanently or temporarily, depending on the duration of adequate antibody titers. An anti-GnRH factor product (Canine Gonadotropin Releasing Factor Immunotherapeutic®; Pfizer) is marketed in the United States for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in dogs. Treatment also causes the testes to shrink and serum testosterone concentrations to decline, both of which would be deleterious to spermatogenesis.

An over-the-counter medicament made from an extract of the berry from the saw palmetto plant (Serenoa repens) has been marketed for relief of some of the urine retention symptoms of BPH in men. There is no evidence that it is beneficial in either dogs or men with BPH (Barsanti, et al., 2000; Bent, et al., 1998). No adverse effects were noted in the treated dogs.

SQUAMOUS METAPLASIA OF THE PROSTATE

Estrogen-secreting testicular tumors are the most common cause of prostatic squamous metaplasia. Rarely, adrenal tumors and exogenous estrogen therapy also may cause squamous metaplasia of the prostatic epithelium and diminish the movement of prostatic fluid within prostatic ducts. The clinical signs and physical examination findings may be identical to those seen in the setting of BPH. Additional signs of hyperestrogenism (see Box 61-1) may also be present. A testicular mass may be palpable or cryptorchidism may be identified during physical examination. Increased numbers of squamous epithelial cells are often found in ejaculated or aspirated prostatic specimens. If necessary, the diagnosis can be confirmed by prostatic biopsy.

Squamous metaplasia is treated by removing the source of estrogen. This is accomplished by the castration of dogs with testicular tumors or the discontinuation of estrogenic drugs. In the absence of estrogenic drugs, the finding of prostatic squamous metaplasia in a castrated dog strongly suggests the presence of a cryptorchid testicle that was not removed. The effects of estrogen are potentially reversible. Unilateral castration might be considered for a dog that still has potential value as a stud, although it may take some time for the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis to recover.

ACUTE BACTERIAL PROSTATITIS AND PROSTATIC ABSCESS

Bacterial infection of the prostate gland may be acute or chronic, and overt prostatic abscesses may develop in dogs with such infections. Normally, the prostate is protected against bacterial colonization by the local production of secretory IgA, the production of prostatic antibacterial factor, and the removal of organisms through frequent micturition. Presumably, the diseased prostate is more prone to infection than the normal gland. Indeed, when cultured, many of the cysts in BPH are found to have asymptomatic infection. The most common route of infection is the ascension of urethral flora. A hematogenous route of infection is also possible. The organisms most commonly isolated from the infected prostate are Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Mycoplasma. Occasionally, Proteus spp., Pseudomonas, or anaerobic organisms are found.

Diagnosis

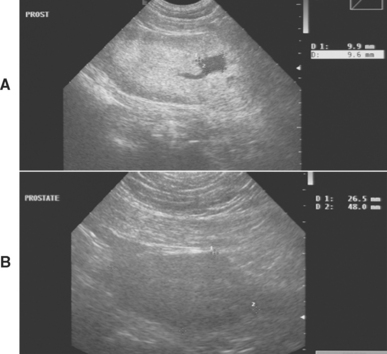

Animals with acute bacterial prostatitis or prostatic abscess usually have a history of an acute onset of severe illness, with abdominal pain and perhaps a hemorrhagic urethral discharge. Fever, dehydration, and pain on palpation of the prostate are usually present. The prostate may be normal in size or enlarged. Asymmetry, prostatomegaly, and fluctuant areas are usually palpable in animals with prostatic abscesses. Septicemia and endotoxemia can develop, in which case signs of shock may also be present. Bacterial prostatitis and prostatic abscess are diagnosed on the basis of the findings from physical examination and ultrasonography and cytology and culture of prostatic fluid. Ultrasonographic examination of the prostate identifies intraparenchymal, fluid-filled spaces consistent with abscesses (Fig. 62-4). A neutrophilic leukocytosis with a variable shift toward immaturity, signs of toxicity in the neutrophils, and monocytosis are typically shown by a complete blood count in animals with acute infections or abscesses.

FIG 62-4 Prostatic abscesses in a 5-year-old male Mastiff treated for 1 year with intermittent antibiotic therapy for recurrent E. coli urinary tract infection. A, Precastration prostate size was 7.0 × 3.5 cm. Largest abscess (9.9 × 9.6 mm) indicated by marks. B, 3 months postcastration prostate size was 4.8 × 2.6 cm. Normal echotexture and all cystic structures resolved. (Notice different magnification of A and B.)

Prostatic fluid obtained by ejaculation is a good specimen for bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity testing. However, dogs with acute prostatitis or abscess usually are too ill or in too much pain to ejaculate. Prostatic specimens obtained by fine-needle aspiration, preferably with ultrasound guidance, are also acceptable. Cultures of prostatic specimens from dogs with bacterial prostatitis usually yield greater than 103 to 105 CFUs/ml. Culture of urine is an alternative to culture of prostatic material because normally some prostatic fluid refluxes into the bladder. Urinalysis usually shows hematuria, pyuria, and/or bacteriuria. When urinalysis findings are abnormal, urine should always be submitted for culture and sensitivity testing. Usually, cultures of urine and prostatic material grow the same organisms. Although specimens for culture can also be obtained by prostatic massage, extreme caution should be exercised when massaging the prostate of animals with acute bacterial prostatitis or prostatic abscess because of the risk of rupturing an abscess or the risk of a septic embolism developing. Cytologic evaluation of the prostatic material should be performed. This usually reveals inflammation with evidence of sepsis and hemorrhage, with macrophages found in animals with chronic infection. Unlike the situation in men, prostatic fluid pH, specific gravity, and cholesterol and zinc concentrations typically are not of diagnostic value in dogs.

Treatment

Acute bacterial prostatitis and prostatic abscesses are serious, life-threatening disorders. Treatment must be prompt and aggressive. Fluid therapy is necessary to correct dehydration and shock. Despite aggressive therapy, the morbidity and mortality associated with prostatic abscesses are high. Large prostatic abscesses are treated most effectively by surgical drainage and omentalization. The abscess may also be drained by fine-needle aspiration under ultrasound guidance. Pending the results of culture and susceptibility, treatment with a fluoroquinolone, ampicillin, or first-generation cephalosporin should be initiated. Antibiotic treatment for acute prostatitis and prostatic abscesses should be continued for a minimum of 4 weeks. Urine or prostatic fluid should be recultured a week after discontinuing antibiotic therapy and again 2 to 4 weeks later to be certain the infection has resolved. Castration should be considered. It can be performed whenever the dog’s hemodynamic and metabolic status is stable enough for general anesthesia. Prostatic abscessation has been reported to recur in about 10% of treated dogs.

CHRONIC BACTERIAL PROSTATITIS

The primary sign of chronic bacterial prostatitis is recurrent urinary tract infection. Chronic bacterial prostatitis may be asymptomatic. Physical abnormalities are often limited to the urinary tract. Prostatic size and shape may be normal, or the prostate may be asymmetric and more firm than normal. It may or may not be painful to palpation. Ultrasonographic findings are nonspecific but typically will be of mixed echotexture with hyperechoic areas reflecting fibrosis. Confirmation of chronic bacterial prostatitis requires cytologic and microbiologic examination of urine and prostatic material, which may be obtained by fine-needle aspiration.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis may be difficult to eradicate because the blood-prostate barrier is quite effective in preventing many drugs from penetrating into the prostatic parenchyma. Erythromycin, clindamycin, oleandomycin, trimethoprim-sulfonamide, chloramphenicol, carbenicillin, enrofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin are the agents most capable of achieving therapeutic concentrations in the prostate. Antibiotic therapy should be based on culture and susceptibility results from urine and prostatic material. Treatment should be continued for at least 4 weeks. Cultures should be repeated during and for several months after discontinuing antibiotic therapy to ascertain whether resistance to antibiotics or persistent infection has developed. Castration hastens the response to treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis.

PARAPROSTATIC CYSTS

Paraprostatic cysts apparently develop from remnants of the Müllerian duct or as a result of the tremendous enlargement of an existing cyst (prostatic retention cyst). In the former situation the rest of the prostate gland is essentially normal, whereas in the latter situation cystic benign hyperplasia usually exists. Often, the origin of the cyst is obscure. Paraprostatic cysts are located outside the prostatic parenchyma but are attached to the gland by a stalk or adhesions. These cysts can become extremely large and cause clinical signs, including tenesmus, stemming from mechanical interference with abdominal viscera. Otherwise, they are often asymptomatic.

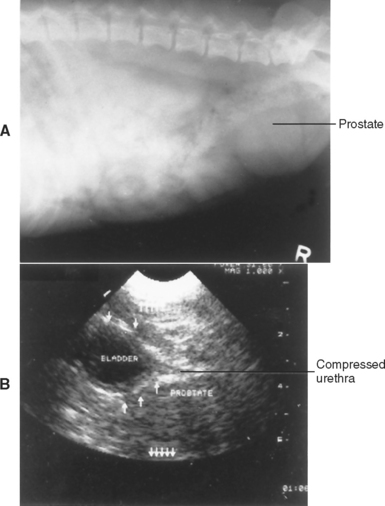

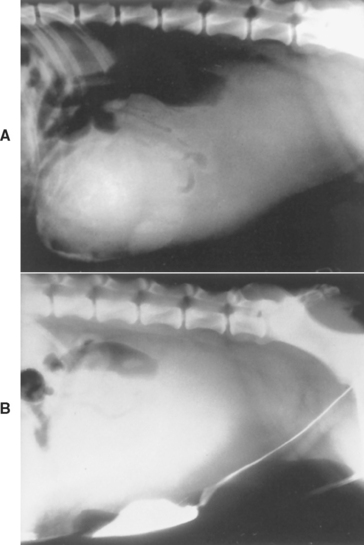

The possibility of a paraprostatic cyst should be considered in the dog with a large caudal-abdominal mass. Diagnostic imaging will identify the mass as a cystic structure and will help differentiate the cyst from the urinary bladder (Fig. 62-5). Fine-needle aspiration of the paraprostatic cyst usually yields a sterile, yellow-to-serosanguineous fluid showing minimal evidence of inflammation. The treatment is castration and complete surgical excision of the cyst. In situations in which the cyst cannot be completely excised, omentalization is recommended. If this fails to resolve the problem, marsupialization could be performed, but this is a very poor alternative to extirpation or omentalization.

PROSTATIC NEOPLASIA

Prostatic adenocarcinoma is the most common neoplasm of the canine prostate. It occurs in older dogs, with a mean age of 10 years at the time of diagnosis. Transitional cell carcinoma arising in the urinary tract may also invade the prostate. The clinical signs and biologic behavior of both tumors in the prostate gland are similar. Prostatic adenocarcinoma is locally invasive and metastasizes to the sublumbar lymph nodes, bony pelvis, and lumbar vertebrae. The link between previous castration and the development of prostatic adenocarcinoma is unclear, but about 50% of affected dogs have been previously castrated. A benign prostatic adenoma has been reported in an intact male dog. Rarely, prostatic adenocarcinoma occurs in cats.

Clinical Features

Clinical signs include tenesmus and dyschezia, stranguria, pain, gait abnormalities, and weight loss. Palpation of the prostate usually elicits pain. The gland is usually not dramatically enlarged, but the shape may be irregular and the consistency somewhat firmer than normal. Because prostatic involution, resulting in a small gland, occurs within 12 weeks of castration, prostatic neoplasia should be the primary consideration in a previously castrated male dog found to have a “normal”-size or large prostate. Urinary obstruction rarely occurs in dogs as a result of prostatic diseases other than prostatic neoplasia, but it is fairly common in those with cancer.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of prostatic neoplasia is suggested by the history, physical, and the findings of diagnostic imaging. Prostatic adenocarcinoma is usually hyperechoic relative to the normal prostate, but this is not pathognomonic. The finding of urethral invasion demonstrated by contrast radiologic studies or ultrasonography is highly suggestive of neoplasia. The diagnosis is confirmed by fine-needle aspiration or biopsy findings. Neoplastic cells may be found in specimens aspirated through a urethral catheter, especially if the tumor has invaded the urethra. Usually, neoplastic cells are not found in ejaculate specimens. The serum and seminal plasma concentrations of acid phosphatase and prostate-specific antigen are not different between normal dogs and dogs with prostatic disease. Although prostate-specific esterase concentrations are higher in dogs with prostatic disease than in normal dogs, this finding is not specific to the cause of prostatic disease.

Treatment

The prognosis for dogs in which prostatic adenocarcinoma arose after castration is much worse than for dogs that are intact at the time. Prostatic adenocarcinoma in intact dogs is likely to be somewhat hormone responsive, and castration may be a beneficial part of the therapy. Prostatic adenocarcinoma in previously castrated dogs is likely to be refractive to hormonal therapy. To date, surgical (prostatectomy), chemotherapeutic, and radiation therapy have been largely unsuccessful in improving the quality or length of life. Treatment with the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug piroxicam may offer some relief. Consultation with a veterinary oncologist is recommended.

Barsanti J. Genitourinary infections. In Greene C, editor: Infectious diseases of the dog and cat, ed 3, St Louis: WB Saunders, 2005.

Barsanti J, et al. Effects of an extract of Serenoa repens on dogs with hyperplasia of the prostate gland. Am J Vet Res. 2000;61:880.

Bent S, et al. Saw palmetto for benigh prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;356:557.

Court E, et al. Effects of delmadinone acetate on pituitary-adrenal function, glucose tolerance, and growth hormone in male dogs. Aust Vet J. 1998;76:555.

Johnston S, et al, editors. Canine and feline theriogenology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

Kutzler M, et al. Prostatic disease. In Ettinger SJ, et al, editors: Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, ed 6, St Louis: Elsevier, 2005.

BOX 62-1

BOX 62-1

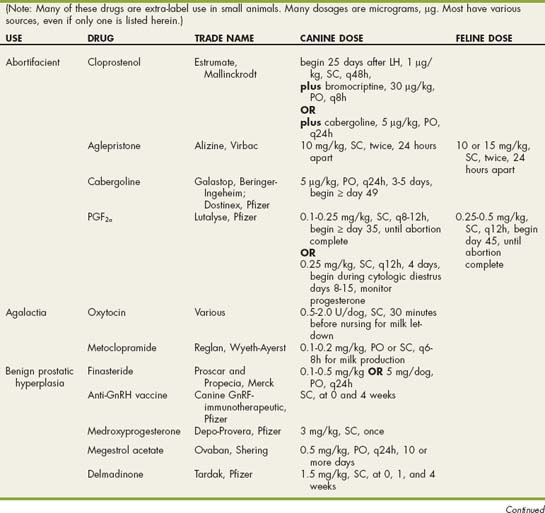

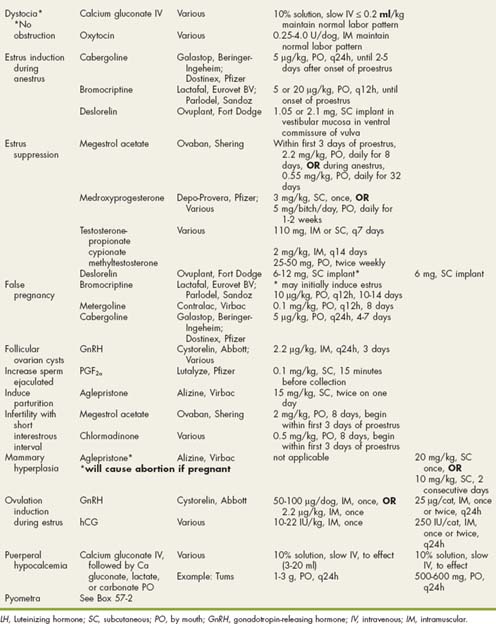

Drugs Used in Reproductive Disorders

Drugs Used in Reproductive Disorders