CHAPTER 61 Disorders of the Penis, Prepuce, and Testes

PENILE DISORDERS

PENILE TRAUMA

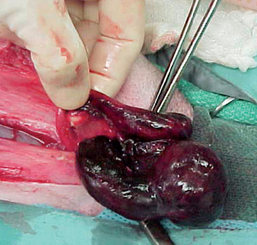

Traumatic injury of the penis occurs in dogs and cats as a result of fighting, being hit by cars, mating inappropriately, and jumping through or upon, rather than over, barriers. Hematomas, lacerations (Fig. 61-1), and fracture of the os penis are injuries that may occur. Penile injuries are usually painful. Other clinical signs include swelling, bruising, and hemorrhage. The prepuce may or may not be similarly affected, depending on whether the penis was extruded (as it would be if erect) when the injury occurred. The diagnosis is made by visual examination of the penis and radiographic examination of the penile urethra and os penis. The integrity of the urethra should be evaluated by retrograde urethrography whenever significant penile trauma is identified. Ultrasonography and color-flow Doppler may help differentiate penile hematoma from priapism.

Treatment includes cleansing of the wounds and débridement if necessary. Lacerations may require surgical closure using absorbable sutures. An antibiotic cream should be applied to the surface of the penis, and the penis should be protruded from the prepuce twice daily until the lesions are healed. This is done to prevent adhesions between the penis and the prepuce from forming. Sexual arousal and other types of excitement must be avoided until the penile lesion is completely healed because erection before then is likely to result in hemorrhage and possibly dehiscence.

Fractures of the canine os penis are very uncommon but are often associated with a urinary outflow tract obstruction or a urethral tear. In addition to the local signs associated with the trauma, these animals may have signs referable to a distended urinary bladder or postrenal uremia. The treatment adopted depends on the severity of the urethral damage and fracture displacement. As an emergency treatment, the urinary bladder may be decompressed by cystocentesis. An indwelling urethral catheter may be placed while the urethra heals. Urethral tears should be sutured if necessary. Urethrotomy or urethrostomy could be considered in some circumstances to temporarily or permanently divert urine flow. Systemic antibiotics should be administered to prevent urinary tract infection. Displaced fractures of the os penis can be immobilized with orthopedic wires. Immobilization is not required in animals with fractures that are not displaced because the penis itself provides adequate support. Occasionally, calluses that form during the healing of the os penis obstruct the urethra. It may be necessary to amputate the penis in the event of severe penile trauma.

PRIAPISM

Priapism is abnormal, persistent erection that is not associated with sexual arousal. The neurophysiology of erection includes sympathetic innervation via the hypogastric nerve, parasympathetic innervation via the pelvic nerve, and somatic and sensory input via the pudendal nerve. Parasympathetic innervation is considered to be responsible for stimulating erection, and sympathetic innervation is considered to be responsible for stimulating ejaculation. During the normal process of erection, relaxation of sinusoidal smooth muscle and increased flow through the arteries and arterioles facilitate rapid filling of the sinusoidal system, which in turn compresses the venous channels and occludes outflow. During the process of detumescence, the trabecular smooth muscle contracts, enabling the venous channels to reopen, and the trapped blood is expelled.

Spinal cord lesions, general anesthesia, phenothiazine administration, and thromboembolism are reported causes of priapism. Venous occlusion at the base of the penis, due to any cause, could result in priapism. In many cases the cause of priapism is undetermined, but the outcome is occlusion of venous outflow and stagnation of blood that will eventually clot in the cavernous sinuses. In addition, ischemic necrosis is common. Fortunately, priapism occurs rarely in dogs and cats.

Some high-strung dogs transiently develop erections when they are excited for any reason. This is not priapism. These transient erections in highly excitable dogs usually diminish as the dog matures. If not, castration, with or without behavioral modification, is usually curative. Priapism is also different from the erection that occasionally persists in some dogs for longer than expected after copulation or semen collection. In these cases, if the estrous bitch is still present, she should be removed from the premises. The male dog should be taken out of the room in which copulation or semen collection took place. These distractions are often sufficient and the erection subsides. If not, sedation or application of cold water compresses could be considered. Priapism should also be differentiated from other causes of penile swelling, such as hematoma or edema. Penile hematomas usually form as a result of trauma or bleeding disorders. Edema usually occurs as a result of paraphimosis. Simple visual inspection and palpation of the penis are usually sufficient to differentiate the conditions. An ultrasound and/or color-flow Doppler examination may help differentiate hematoma from priapism.

During priapism clotting of the blood trapped in the cavernous sinuses, ischemia, and necrosis develop quickly. Therefore pharmacologic intervention, if it is to be successful, must be done within hours. Nonischemic priapism may respond to pharmacologic treatment with anticholinergic or antihistaminic agents, such as diphenhydramine and benztropine. Benztropine contains the active ingredients of atropine and diphenhydramine; a dose of 0.015 mg/kg intravenously has been suggested for dogs. The β-adrenergic agonist terbutaline has also been used successfully in the treatment of priapism in men. Surgical drainage and intracorporeal lavage have also been reported as successful treatments. Unfortunately, many of the reported cases in dogs and cats were not presented to veterinarians until the condition had been present for days to weeks, by which time necrosis necessitated penile amputation or perineal urethrostomy.

During priapism (Fig. 61-2) the penis should be protected against additional damage or irritation that may perpetuate the problem or invite the development of sequelae, such as edema, thrombosis, fibrosis, penile paralysis, or necrosis. Physical treatments include cleansing the penis, applying antibiotic cream, and attempting to maintain the penis within the prepuce until the condition subsides.

MISCELLANEOUS PENILE DISORDERS

Vesicles, ulcers, pyogranulomatous lesions, warts, and neoplasia of the penis have been identified in dogs. The clinical signs are similar and include a preputial discharge, excessive licking of the prepuce or penis, or a mass protruding from the prepuce. These lesions are differentiated by visual examination, exfoliative cytologic studies, bacterial and fungal cultures, and biopsy. Transmissible venereal tumor (TVT) is the most commonly reported penile tumor in dogs (see Chapter 57). The macroscopic appearance of TVT and penile warts may be similar. In our experience, penile warts often resolve spontaneously after biopsy of the lesion (Fig. 61-3). The cause of vesicular lesions is uncertain. Canine herpes virus has been implicated but is usually not documented. Herpes virus infection is discussed in Chapter 58. Hyperplasia of the lymphoid follicles at the base of the penis may have a similar appearance to vesicles. Lymphoid follicular hyperplasia is thought to develop as a result of chronic irritation. Ulcers and pyogranulomatous lesions are uncommon, but when present they seem to be associated with infection and balanoposthitis.

Congenital penile disorders other than a persistent penile frenulum are rare. Penile hypoplasia has been noted in dogs and cats. Some affected animals have had an abnormal complement of sex chromosomes. In most the penile hypoplasia has been an incidental finding. In one dog it was associated with urine pooling in the preputial cavity. Diphallia, or duplication of the penis, has been reported in dogs and cats. Hypospadia is an anomaly in closure of the urethra that occurs because of a defect in the androgen receptor(s). The result is one or more abnormal openings into the urethra anywhere along its length. The penis, prepuce, and sometimes the scrotum are simultaneously and similarly affected (Fig. 61-4). Hypospadia has been reported more often in dogs than in cats. Besides the abnormal appearance of the external genitalia, clinical signs include urinary incontinence and urinary tract infection. Affected animals may have additional congenital anomalies, such as cryptorchidism. Surgical correction may be considered.

PERSISTENT PENILE FRENULUM

Under the influence of androgens, the surfaces of the glans penis and the preputial mucosa normally separate before or within months of birth, depending on the species of animal. If this separation does not occur, connective tissue persists between the penis and the prepuce. In dogs the persistent penile frenulum is usually located on the ventral midline of the penis (see Fig. 61-5). A persistent penile frenulum may cause no clinical signs, or it may be associated with preputial discharge or excessive licking of the prepuce. Persistent frenulum may cause the penis to deviate ventrally or laterally so that the dog is unable or unwilling to mate. The diagnosis is made by visual examination. Treatment is surgical excision, which can often be done using sedation with local anesthesia because the frenulum tends to be a sheer, avascular membrane.

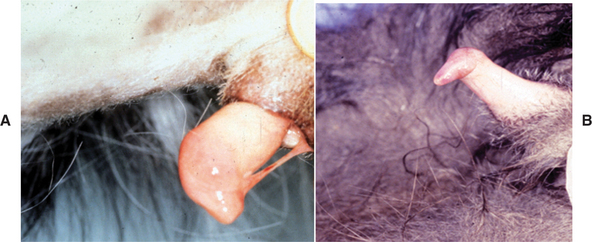

FIG 61-5 A, Persistent frenulum in a dog. B, Failure of complete separation of the penile and preputial mucosa in a cat.

Persistence of the adhesions of the prepuce and penis has been seen in male cats that are castrated between 7 weeks and 5 months of age, but the prevalence of this condition in the general cat population, irrespective of neuter status or age at castration, is unknown. Failure of the glans penis and preputial mucosa to separate prevents the penis from being fully extruded or causes deviation of the erect penis (see Fig. 61-5). The clinical significance, if any, of the failed penile-preputial separation seen in some cats neutered at very young ages remains to be determined.

PREPUTIAL DISORDERS

BALANOPOSTHITIS

Inflammation or infection of the preputial cavity and penis, balanoposthitis, is very common in dogs and rare in cats. The offending organisms are usually members of the normal preputial flora (see Box 60-1), although infection with canine herpes virus and Blastomyces has also been reported. Balanoposthitis usually causes no clinical signs other than a purulent preputial discharge that is quite variable, from a scant white smegma to a copious green pus. The discharge associated with balanoposthitis is not sanguineous unless the cause is neoplasia or foreign material. The diagnosis of balanoposthitis is made by physical examination of the penis and preputial cavity all the way to the fornix, in a search for foreign material, neoplasia, ulceration, or inflammatory nodules. Cultures and cytologic studies are rarely performed, unless herpes virus or fungal infection is suspected because of the vesicular appearance of the lesions or the presence of similar lesions elsewhere on the body. The treatment of balanoposthitis is usually conservative. The hair should be clipped from the preputial orifice and from the surrounding area if discharge has been accumulating there. Flushing the preputial cavity with antiseptic solutions (e.g., chlorhexidine, povidone-iodine) seems to be helpful. Topical antibacterial medications may be instilled into the preputial cavity. Castration usually results in diminished preputial secretions. In persistent or refractory cases, cytology, culture, and endoscopic examination should be considered.

PARAPHIMOSIS

Paraphimosis is a condition in which the penis is prevented from retracting back into the preputial cavity. It occurs most frequently after an erection in dogs. Therefore it is seen quite often after semen collection and occasionally after copulation. Paraphimosis may occur in longhaired cats when the penis becomes entangled in the preputial hairs. Otherwise, it is uncommon in cats. The protruded penis usually becomes trapped because the prepuce has turned in on itself (see Fig. 61-2). Presumably, this occurs because the skin or hair at the preputial orifice adheres to the surface of the penis and is pulled into the preputial cavity as an erection subsides. The inverted preputial skin then compromises the circulation to the protruded penis.

The signs of paraphimosis depend primarily on its duration. Initially, the exposed penis is normal in appearance and nonpainful. However, after several minutes the exposed penis becomes edematous (see Fig. 61-6) and increasingly painful. In addition to the damage caused by continued poor circulation, the exposed penis is subject to trauma. The surface becomes dry, and fissures may develop. The urethra is usually not damaged. The unexposed penis and the uninvolved prepuce are normal and nonpainful. Long-standing paraphimosis may result in gangrene or necrosis.

Paraphimosis is diagnosed by visual inspection. The exposed penis may have become so painful that sedation or anesthesia is required, although this is not usually necessary early on. Treatment involves returning the prepuce to its normal configuration, restoring circulation to the penis, and replacing the penis in the preputial cavity. This is accomplished by gently sliding the prepuce in a posterior direction, such that more of the glans penis is protruded. The prepuce is thus retracted until the cranial aspect of the prepuce “unfolds” and the preputial orifice is exposed (see Fig. 61-6). Circulation to the penis usually improves immediately after the prepuce is restored to its normal configuration. Penile edema then begins to subside. The surface of the penis is cleansed or débrided as necessary. Topical antibiotic or an antibiotic-steroid cream may be applied if the penile mucosa has been damaged. Even though some penile edema may still be present, the prepuce usually slides easily over it and the penis is thus replaced in the preputial cavity. Water-soluble lubricant should be applied as necessary to accomplish this. If, even after circulation is restored, the edematous tissue is of sufficient magnitude that the prepuce cannot slide over it, application of pressure with a cool water compress is usually effective in resolving the edema.

Rarely is it necessary to enlarge the preputial orifice. If it is, an incision is made on the ventral midline of the prepuce, and after the penis is in place, the incision is closed in separate layers. The penis will usually stay within the preputial cavity, and penile swelling quickly subsides. The degree of swelling can be assessed by palpating the penis through the prepuce if there is concern that protruding the penis from the preputial cavity will be unduly painful. Rarely does the still-swollen penis protrude from the prepuce. The preputial orifice may be temporarily (1 to 24 hours) sutured closed, but there is the risk that urine will accumulate in the preputial cavity during this time. If the penis has become necrotic or gangrenous, penile amputation is indicated.

Conditions other than paraphimosis may also cause the penis to protrude from the prepuce. These include priapism, phimosis, an abnormally short prepuce in dogs, and a ring of preputial hair in cats. Penile trauma may cause penile hematomas to form. The swelling associated with the extravasation of blood may be sufficiently severe to cause the penis to protrude. Treatment is conservative and consists in protecting the exposed penis from trauma. The preputial orifice may also be temporarily closed. If possible, the hematoma is allowed to resolve spontaneously; otherwise, it can be drained surgically. Foreign material within the preputial cavity or around the glans penis may also cause the penis to protrude.

PHIMOSIS

Phimosis is a condition in which the penis is trapped within the preputial cavity. It usually occurs as a congenital defect in which the preputial opening is abnormally small and the penis cannot protrude. Phimosis is uncommon in cats and dogs. It may be recognized in young animals as a cause of a urinary outflow tract obstruction or of the dribbling of urine that has accumulated in the preputial cavity. Phimosis may be recognized in an affected male when it is unable to copulate. It is treated by surgically enlarging the preputial orifice. The preputial hairs of longhaired cats may entangle the preputial orifice, causing clinical signs similar to phimosis. It is treated by clipping the preputial hairs.

TESTICULAR DISORDERS

CRYPTORCHIDISM

Cryptorchidism is the failure of one or both testes to descend into the scrotum. The condition may be unilateral or bilateral. The undescended or retained testicle may be located in the abdominal cavity, in the inguinal canal, or in the subcutaneous tissue between the external inguinal ring and the scrotum. On rare occasions a cryptorchid testis is found in the perineal subcutis dorsal or lateral to the scrotum. The testicular hormone insulin-like factor 3 (also called relaxin-like factor), which is produced by prenatal and postnatal Leydig cells, mediates the transabdominal testicular descent from the caudal pole of the kidney to the inguinal canal. It induces growth and differentiation of the gubernaculum from the caudal suspensory ligament. The transabdominal migration of the fetal testis is independent of androgens, whereas the inguino-scrotal descent is mediated by testosterone. Testosterone causes regression of the cranial suspensory ligament. During the inguino-scrotal phase of migration, there is shortening of the gubernaculum and eversion of the cremaster muscle. The normal time of testicular descent has not been firmly established in dogs or cats. In cats testicular descent appears to be a prenatal event. In dogs testicular descent is complete by 10 to 42 days of age. Although later descent is possible, a diagnosis of cryptorchidism is likely if the testes are not palpable within the scrotum by 8 to 10 weeks of age. Because the testes are so small and mobile in infant animals, some veterinarians have recommended that a diagnosis of cryptorchidism not be made until a dog is 6 months old.

Unilateral cryptorchidism is more common than bilateral cryptorchidism in both dogs and cats. The undescended testis is found in the abdomen or in the subcutaneous tissues in the inguinal area with about equal frequency. Bilaterally undescended testes are most often found in the abdomen. There is no apparent difference in the prevalence of right- or left-sided unilateral cryptorchidism in dogs or cats. True monorchidism (congenital absence of one testis) is extremely rare. The incidence of cryptorchidism in the general animal population is unknown. Of 1345 cats presented for castration, 23 (1.7%) were cryptorchid, which is similar to the findings in 3038 feral cats trapped for neutering, of which 35 (1.2%) were cryptorchid and 46 (1.5%) were thought to have been previously castrated. The prevalence of cryptorchidism in dogs in various hospital populations is reported between 1.2% and 5%. Cryptorchidism was found in 44 (2.6%) of 1679 dogs from a pet store.

Although the specific mode(s) of inheritance is not known in either species, cryptorchidism is generally believed to be associated with family lineage. Therefore the prevalence is likely to vary with breed and species. For example, the incidence of cryptorchidism in 2929 boxers was 10.7% (Nielen et al., 2001). The simplest model consistent with the evidence available is a sex-limited, autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. The expression of the trait is limited to males, but the genetic defect is not linked to the sex chromosomes. Therefore both males and females carry the gene and can pass it on to their offspring, but only the homozygous males are phenotypically abnormal (cryptorchid) and readily identifiable. Females cannot express the trait regardless of their genotype. Heterozygous (carrier) males have normal phenotype; in other words, they are not cryptorchid. Therefore, with the exception of a homozygous × homozygous cross, which would produce cryptorchid male puppies, some litters are likely to contain all phenotypically normal males, whereas other litters from the same dam and sire will have affected males. However, the inheritance of cryptorchidism is known to be more complex than that explained by the simple autosomal recessive, sex-limited model, providing yet another possible explanation for why each litter from the same breeding pair does not always have the same phenotypic result.

The undescended testis is not normal. Spermatogenesis is usually completely absent, especially in intraabdominal testes, because of the higher temperature. Spermatogenesis does not fully recover, even if the testis descends into the scrotum at a later time. Because interstitial cells continue to produce testosterone, libido and secondary sex characteristics are normal. Bilaterally cryptorchid animals are sterile, which effectively removes them from the gene pool. Although the number of spermatozoa in the ejaculate of animals with unilateral cryptorchidism is less than that of normal animals, they are expected to be fertile. Therefore unilaterally cryptorchid males will perpetuate the trait if allowed to breed.

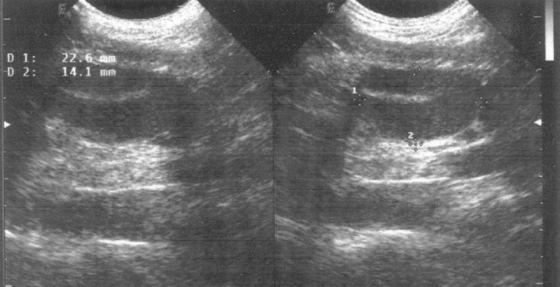

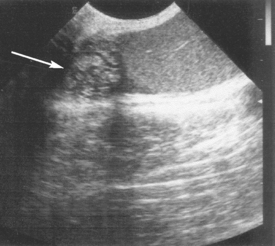

There is no known medical treatment that can reliably cause cryptorchid testes to descend. Favorable results occasionally have been noted in male dogs and in boys treated with human chorionic gonadotropin. However, it is generally believed that the apparent success is actually the result of the coincidental spontaneous descent of mobile testes that were located very near the scrotum. There appear to be no reports of the successful medical management of intra abdominal cryptorchidism in any species. Castration of cryptorchid dogs is recommended primarily because of the increased risk of testicular neoplasia in retained testes. Ultrasonography may be helpful in locating the retained testis (Fig. 61-7).

FIG 61-7 Sonogram showing an intraabdominal cryptorchid testis in a dog.

(Courtesy Dr. Gustavo Sepulveda, East Lansing, Mich.)

In dogs testicular neoplasia is as much as 13 times more likely to develop in undescended than in descended testes. Because testicular neoplasia, even in scrotal testes, is so common in older dogs, this represents a significant risk. Castration of cryptorchid dogs while they are young is therefore recommended. Sometimes the cryptorchid testis is difficult to find. If, at the time of surgery, the ductus deferens, testicular vessels, or epididymis are found, it is highly likely that the ipsilateral testis also exists. True monorchidism is extremely rare. After unilateral castration, suspected monorchidism should be confirmed with appropriate hormonal testing, such as determining serum testosterone concentrations before and after gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) or measuring serum luteinizing hormone (LH) concentrations. Testicular neoplasia is also more common in cryptorchid testes in men. Even after orchiopexy, the standard treatment for cryptorchidism in people, the previously ectopic testis is at greater risk for testicular cancer than the descended testis. The risk of testicular cancer in cryptorchid men treated with orchiopexy after puberty (age 13 years) is approximately twice that of men treated before the age of 13. Testicular neoplasia is rare in cats, although it has been reported in cryptorchid testes.

TESTICULAR NEOPLASIA

Testicular tumors are very common in dogs older than 10 years of age, second only to skin tumors. In most dogs testicular tumors are found incidentally during physical examination, castration, or necropsy. Testicular tumors are rare in cats. In dogs Sertoli cell tumors, Leydig cell (interstitial cell) tumors, and seminomas occur with about equal frequency except in intraabdominal testes, in which the most common neoplasm is Sertoli cell tumor. The most important risk factors for testicular neoplasia are age and cryptorchidism. Testicular tumors are rare in dogs younger than 6 years of age. Testicular cancer is diagnosed almost 11 times more often in cryptorchid testes than in scrotal testes. Certain gene expressions and carcinogens are also risk factors.

Diagnosis

The most common clinical sign of testicular neoplasia is enlargement of the testis. Sertoli cell and interstitial (Leydig) cell tumors can produce hormones, particularly estrogen, that cause paraneoplastic syndromes. These include atrophy of the contralateral testis, bone marrow suppression, pendulous prepuce, gynecomastia, alopecia and hyperpigmentation, and squamous metaplasia of the prostate (Box 61-1). The gynecomastia and pendulous prepuce have been referred to as feminization. The bone marrow suppression induced by estrogen is characterized by anemia, thrombocytopenia, and/or leukopenia. Some of the clinical signs may be related to anemia or bleeding as a result of the thrombocytopenia. Intraabdominal testicular tumors of sufficient size may cause interference with other abdominal organs. Uncommonly, dogs with testicular tumors may be presented because of infertility, but most affected animals are past their breeding years.

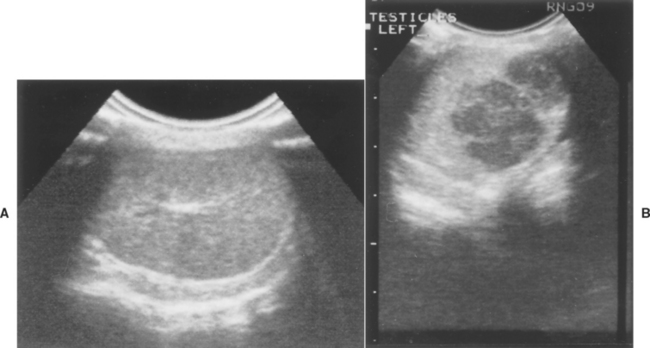

The diagnosis of testicular neoplasia is usually straightforward. It should be suspected as a possible cause for any testicular mass and also feminization. The index of suspicion is highest in old, cryptorchid males. The diagnosis is most challenging in dogs that do not have scrotal testes because they may erroneously be assumed to have previously been castrated. Exfoliative cytology of the preputial mucosa may confirm the presence of excessive estrogen, which causes it to cornify like the vaginal epithelium (see Chapter 56). A testicular tumor is by far the most likely source of hyperestrogenism in a male dog, although pathologic production of sex hormones by the adrenal gland has been reported in dogs with hyperadrenocorticism. Ultrasonography is helpful in evaluating the testes of animals in which testicular neoplasia is suspected but not palpable. They have a variable echo texture. Tumors less than 3 cm in diameter are usually hypoechoic (Fig. 61-8). The larger tumors tend to disrupt normal testicular architecture and may contain focal areas of ischemic necrosis; thus large testicular tumors usually have mixed echogenicity. Ultrasonography and radiology can be used to evaluate intraabdominal testes, but testes similar in size to the diameter of the small bowel may be difficult to identify.

FIG 61-8 Sonogram of normal right testis (A) and left testis (B) with a seminoma in an infertile, 9-year-old English Bulldog. After hemicastration the dog sired a litter of nine pups. Hatch marks are 1 cm.

Fine-needle aspiration of palpable testicular masses is easily performed, but it is rarely done when the index of suspicion of neoplasia is high because tissue specimens can be obtained at the time of castration. Nevertheless, cytologic examination of aspirated material can be very helpful in differentiating a testicular neoplasm from other masses, such as abscess or granuloma, or if owners are reluctant to consider castration without a definitive diagnosis. A complete blood count is indicated to assess the possibility of bone marrow toxicity. Because most affected dogs are geriatric, a preoperative biochemical panel and urinalysis are also reasonable.

Treatment for testicular tumors is castration. If the dog has value as a stud, unilateral castration could be performed. The clinical signs associated with hyperestrogenism usually resolve promptly, except for bone marrow toxicity and infertility. The latter is not surprising, given the age of most affected dogs. The testis should always be submitted for histopathologic evaluation. Because most canine testicular tumors are benign, it would be reasonable to delay complete staging of the tumor until histopathologic confirmation of malignancy. Intraabdominal metastasis is more common than pulmonary. Treatment options for malignant and metastatic testicular tumors should be considered in consultation with a veterinary oncologist.

ORCHITIS AND EPIDIDYMITIS

The testis or epididymis can become infected via the hematogenous route, through the ascension of pathogens from elsewhere in the urogenital tract, or as a result of penetrating wounds. Extension or progression of infection from the epididymis to the testis, or vice versa, is common. Orchitis-epididymitis is more common in dogs than in cats. Aerobic bacteria are most often implicated. Mycoplasma, Brucella canis (see Chapter 58), Blastomyces, Ehrlichia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and feline infectious peritonitis are also reported to infect the testes, epididymides, or scrotum. Bacterial infection of the testes, epididymides, or scrotum causes alterations in spermatogenesis as a result of the destructive properties of the organisms themselves and as a result of local swelling, inflammation, and hyperthermia.

The clinical signs of orchitis-epididymitis vary with the chronicity of the infection. Acute infections are usually associated with swelling of the scrotum and scrotal contents and are painful. The affected epididymis or testis is enlarged, firm, and warm. The scrotal skin may be inflamed, and dogs may lick the scrotum excessively. Fever and lethargy may be present in animals with systemic infections. Conversely, some affected animals may show minimal discomfort, and the owner may not notice the acute phase. The scrotum is usually normal in animals with chronic orchitisepididymitis. Eventually, the testis becomes soft and atrophic. Then the epididymis may seem more firm and prominent than usual. Infertility is common in animals with either acute or chronic orchitis-epididymitis, and it may be the presenting complaint.

Diagnosis

Orchitis-epididymitis is diagnosed on the basis of physical examination, ultrasonography (Fig. 61-9), cytology, and culture findings. Specimens for culture and cytology may be obtained by collection of semen or fine-needle aspiration of the testis. Semen from dogs with active orchitis-epididymitis contains many inflammatory cells (leukospermia) and abnormal spermatozoa. Bacteria or other infectious agents, however, are usually not seen during cytologic evaluation of semen. They are more commonly observed in specimens obtained by fine-needle aspiration. In animals with chronic infection and atrophy of the testes, the number of inflammatory cells and spermatozoa decreases, eventually resulting in azoospermia. Serologic tests for B. canis should always be performed in dogs with these clinical and cytologic findings. A thorough evaluation of the prostate gland is also warranted.

FIG 61-9 Sonogram of abnormal canine epididymis (arrow) typical of suppurative epididymitis. Normal-appearing testis is to the right.

Semen cultures in dogs with active bacterial orchitisepididymitis usually yield more than 105 colony-forming units/ml of semen. However, culture results must be interpreted in light of the normal urethral florae and other clinical and cytologic findings (see Chapter 60). Microbiologic cultures may be negative in animals with chronic orchitis-epididymitis. This is frequently the case in animals with chronic B. canis infection. Therefore negative culture results do not necessarily exclude infection as the inciting cause. The results of cytologic and microbiologic evaluation of semen from dogs with orchitis-epididymitis are indistinguishable from those of prostatitis. Further, prostatitis and orchitis-epididymitis may be concurrent. Therefore the prostate should always be thoroughly evaluated by palpation, ultrasonography, and cytologic evaluation of the third fraction of the ejaculate or specimens obtained by fine-needle aspiration of the prostate.

Treatment

Appropriate antimicrobial therapy should be initiated on the basis of culture results. Antibiotics to consider pending results of sensitivity testing are those that are usually effective against the common urogenital organisms. These antibiotics include enrofloxacin, amoxicillin, clavulanate-amoxicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfonamide, which are effective against either gram-negative or gram-positive organisms. Cephalosporins and tetracycline can also be considered. Antimicrobial therapy, determined on the basis of the results of culture and sensitivity testing, should continue for a minimum of 2 weeks. Soaking the scrotum in cool water may help to minimize the damage caused by hyperthermia and swelling. In cases of unilateral involvement, unilateral orchiectomy may be the best way to protect the apparently unaffected gonad. Antibiotics should be administered regardless of whether surgery is performed. The prognosis for recovery of fertility is poor in dogs or cats with orchitis and epididymitis, regardless of the causative organism. Orchiectomy effectively decreases the burden of infection and should be considered if fertility appears to be irreversibly lost.

TORSION OF THE SPERMATIC CORD

Torsion of the spermatic cord is often called testicular torsion. Torsion of the spermatic cord occurs more often in intraabdominal testes than scrotal testes (Fig. 61-10). The clinical signs are related to the acute abdominal pain that results. If torsion of a scrotal testis occurs, pain is also the major clinical sign. There is also scrotal and testicular swelling, which can be quite pronounced. Often, the thickened spermatic cord can be palpated. Ultrasonographic examination of the affected testis and spermatic cord usually reveals the spiral course of the spermatic vessels. Treatment is unilateral orchiectomy because spermatogenesis is irreparably damaged as a result of ischemia within 1 to 2 hours of testicular torsion. Although some recovery is possible, fibrosis usually occurs.

MISCELLANEOUS TESTICULAR AND SCROTAL DISORDERS

Whenever a lesion is found in one testis, both testes should be thoroughly evaluated. Differentiating focal lesions such as tumors, granulomas, spermatoceles or cysts can be accomplished with ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration. Spermatoceles are caused by stasis and accumulation of sperm. They occur more commonly in the ductus deferens or epididymal ducts than in the seminiferous tubules. They may be congenital or acquired as a result of trauma, including fine-needle aspiration or biopsy. They may be the result, or the cause, of local inflammation and the development of sperm granulomas. They may also be incidental findings. Cysts may arise in the seminiferous tubules or the rete testis. They are usually incidental findings during ultrasound, but, like spermatoceles, they may cause a mass or obstruction to the flow of sperm.

People often assume that an enlarged scrotum is due to testicular enlargement. Other causes of scrotal enlargement include epididymal or spermatic cord enlargement (e.g., scirrhous cord), herniation of omentum or small bowel into the scrotum, scrotal edema, or hydrocele. Hydrocele is the accumulation of fluid between the visceral and parietal tunics of the scrotum. It may be a transudate, hemorrhage, or exudate. To differentiate among these causes, careful palpation and ultrasound of the scrotal contents are necessary. The scrotal skin is susceptible to contact irritant dermatitis. Self-mutilation of the scrotal skin sometimes occurs as a result of underlying gonadal disease. Otherwise, the considerations for problems with the scrotal skin are the same as for skin elsewhere on the body.

Attia KA, et al. Anti-sperm antibodies and seminal characteristics after testicular biopsy or epididymal aspiration in dogs. Theriogenology. 2000;53:1355.

Hughes IA. Female development—all by default? N Engl J Med. 2004;351:8.

Johnston SD, et al. Canine and feline theriogenology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

King GJ, et al. Hypospadias in a Himalayan cat. J Small Animal Pract. 2000;41:508.

Knighton EL. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia secondary to 11 β-hydroxylase deficiency in a domestic cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;225:238.

Lue TF. Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1802.

Mischke R, et al. Blood plasma concentration of oestradiol-17β, testosterone and testosterone/oestradiol ratio in dogs with neoplastic and degenerative testicular diseases. Res Vet Sci. 2002;73:267.

Nielen AL, et al. Heritability estimations for diseases, coat color, body weight, and height in a birth cohort of Boxers. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62:1198.

Pavletic MM, et al. Subtotal penile amputation and preputial urethrostomy in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;230:375.

Peters MA, et al. Aging, testicular tumours and the pituitary-testis axis in dogs. J Endocrinol. 2000;166:153.

Peters MA, et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system and steroidogenic enzymes in canine testis tumors. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:22.

Pettersson A, et al. Age at surgery for undescended testis and risk of testicular cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1835.

Scott KC, et al. Characteristics of free-roaming cats evaluated in a trap-neuter-return program. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;221:1136.

Silversides DW, et al. Genetic manipulation of sex differentiation and phenotype in domestic animals. Theriogenology. 2001;55:51.

Syme HM, et al. Hyperadrenocorticism associated with excessive sex hormone production by an adrenocortical tumor in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219:1725.

Williams LS, et al. Use of the anesthetic combination of tiletamine, zolazepam, ketamine and xylazine for neutering feral cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;220:1491.

Yasuda MN, et al. Teratoma in a feline unilateral cryptorchid testis. Vet Path. 2001;38:719.

BOX 61-1

BOX 61-1