CHAPTER 79 Approach to the Patient with a Mass

APPROACH TO THE CAT OR DOG WITH A SOLITARY MASS

It is common for the practicing veterinarian to evaluate a clinically healthy cat or dog in which a single mass is found during a routine physical examination or in which the owner has detected a mass and is concerned about it. The mass can be superficial (e.g., enlarged prescapular lymph node, subcutaneous mass) or deep (e.g., splenic mass, enlarged mesenteric lymph node), and often the clinician wonders how to proceed and what to recommend to the owner.

In this situation there are several possible approaches:

The first option (i.e., do nothing and see if the mass goes away) is not really an option because the presence of any mass is abnormal, and it should therefore be evaluated. As a general rule, most masses, with the notable exception of inflammatory lesions, histiocytomas in young dogs, and transmissible venereal tumors, do not regress spontaneously.

At our clinic the typical first step in evaluating a solitary mass is to perform fine-needle aspiration (FNA) to obtain material for cytologic evaluation (see Chapter 75). Using this simple, relatively atraumatic, quick, and inexpensive procedure, the clinician can arrive at a highly presumptive or definitive diagnosis in the vast majority of animals. After identifying the nature of the mass (i.e., benign neoplastic, malignant neoplastic, inflammatory, or hyperplastic), the clinician can recommend additional tests to the owner.

Performing a biopsy for histopathology constitutes another valid alternative. However, the cost, the trauma to the patient, and the time it takes for the pathologist’s report to become available make this a less attractive option than FNA. An intensive workup of a cat or dog with a solitary mass (i.e., option 4) may not be warranted because additional diagnostic information regarding the mass is rarely gained from these procedures. However, the presence of metastatic lesions on thoracic radiographs may suggest that the mass in question is a malignant tumor.

If a cytologic diagnosis of a benign neoplasm is made (e.g., lipoma), the clinician faces two options: to do nothing and observe the mass or to surgically excise it. Because benign neoplasms in cats and dogs are rarely premalignant (with the notable exception of solar dermatitis/carcinoma in situ preceding the development of squamous cell carcinomas in cats), if a benign neoplasm is definitively diagnosed, a sound approach is to recommend a wait-and-see attitude. If the mass enlarges, becomes inflamed, or ulcerates, then surgical excision is recommended. However, the clinician should keep in mind that most benign neoplasms are more easily excised when they are small (i.e., it is not advisable to wait until the mass becomes quite large). To some owners the option of surgically excising the mass shortly after diagnosis is more appealing.

If a cytologic diagnosis of malignancy is obtained (or if the findings are suggestive of or compatible with malignancy), additional evaluation is warranted. Different approaches are indicated, depending on the cytologic diagnosis (i.e., carcinoma versus sarcoma versus round cell tumor). However, with the exception of mast cell tumors (i.e., pulmonary metastases are extremely rare in dogs and cats with this tumor type), thoracic radiographs should be obtained to search for metastatic disease in dogs and cats with most types of malignant neoplasms. Two lateral views and a ventrodorsal (or dorsoventral) view are recommended to increase the likelihood of detecting metastatic lesions. If available, a computed tomography (CT) scan may be obtained because it can detect masses smaller than those detectable on plain radiography. Plain radiographs of the affected area may also be indicated to look for soft tissue and bone involvement. Abdominal ultrasonography (or radiography) may be indicated for further staging in animals with certain neoplasms (e.g., hemangiosarcoma, intestinal neoplasms, mast cell tumors). A CBC, serum biochemistry profile, and urinalysis may provide additional clinical information (e.g., paraneoplastic syndromes, concurrent organ failure).

If the mass is malignant and there is no evidence of metastatic disease, surgical excision is usually recommended. If there are metastatic lesions, the pathologist feels comfortable with the cytologic diagnosis, and the tumor is likely to respond to chemotherapy (e.g., lymphoma, hemangiosarcoma), chemotherapy constitutes the best viable option (see Chapter 76). However, as discussed in Chapter 76, surgical resection of the primary mass (e.g., mammary carcinoma) in a patient with metastatic lesions may provide considerable palliation and prolong good-quality survival. If an assertive diagnosis cannot be made on the basis of the cytologic findings, an incisional or excisional biopsy of the mass is advisable. In our clinic we typically do not recommend euthanasia in dogs and cats with metastatic lesions and good quality of life because survival times in excess of 6 months (without chemotherapy) are common in animals with most metastatic neoplasms.

APPROACH TO THE CAT OR DOG WITH A METASTATIC LESION

Radiographic or ultrasonographic evidence of metastatic cancer is often found during the routine evaluation of an animal with a suspected or confirmed malignancy or during the evaluation of a cat or dog with obscure clinical signs. In such instances the clinician should be familiar with both the biologic behavior of the common neoplasms and with their characteristic radiographic and ultrasonographic patterns (Table 79-1). Suter et al. (1974) have described the typical radiographic appearances of various metastatic malignancies. In addition, the owner should be questioned regarding any prior surgeries in the pet (e.g., excision of a mass that was thought to be benign but may have been the primary malignancy).

TABLE 79-1 Metastatic Behavior of Some Common Neoplasms in Dogs and Cats

TABLE 79-1 Metastatic Behavior of Some Common Neoplasms in Dogs and Cats

| NEOPLASM | SPECIES | COMMON METASTATIC SITES |

|---|---|---|

| HSA | D | Liver, lungs, omentum, kidney, eye, CNS |

| OSA | D | Lungs, bone |

| SCC—oral | C, D | Lymph nodes, lungs |

| aCA—mammary | C, D | Lymph nodes, lungs |

| aCA—anal sac | D | Lymph nodes |

| aCA—prostate | D | Lymph nodes, bone, lungs |

| TCC—bladder | D | Lymph nodes, lungs, bone |

| MEL—oral | D | Lymph nodes, lungs |

| MCT | D | Lymph nodes, liver, spleen |

| MCT | C | Spleen, liver, bone marrow |

aCa, Adenocarcinoma; C, cat; CNS, central nervous system; D, dog; HSA, hemangiosarcoma; MEL, malignant melanoma; MCT, mast cell tumor; OSA, osteosarcoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; TCC, transitional cell carcinoma.

If a cytologic or histopathologic diagnosis of malignancy has already been made and the metastatic lesions are detected while staging the animal, treatments can be recommended to the owner at this point (assuming that the metastatic lesions have arisen from the previously diagnosed primary tumor). As a general rule, cytologic or histopathologic evaluation of one or more of these lesions should be performed so that the clinician can best advise the owner as to the appropriate course of action.

A cytologic diagnosis of metastatic lung lesions can usually be obtained through blind or ultrasonography-, fluoroscopy-, or CT-guided percutaneous FNA of the lungs. To do this, the area to be aspirated (i.e., the one with the highest density of lesions radiographically or the identified lesions) is clipped and aseptically prepared. For blind percutaneous lung aspirates the animal should be in sternal recumbency or standing; a 25-gauge, 2- to 3-inch (5- to 7.5-cm) needle (depending on the size of the animal) coupled to a 12- to 20-ml syringe is rapidly advanced through an intercostal space along the cranial border of the rib to the depth required (previously determined on the basis of the radiographs), and suction is applied two or three times and then released; the needle is then withdrawn. Smears are made as described in Chapter 75. When aspirating lungs, the clinician is likely to obtain a fair amount of air or blood (or both) in the syringe. Rare complications associated with this technique include pneumothorax (animals should be closely observed for 2 to 6 hours after the procedure and dealt with accordingly if pneumothorax develops) and bleeding. As a general rule, FNA of the lungs should not be performed in cats or dogs with coagulopathies.

If an FNA of the lungs fails to yield a diagnostic sample, a lung biopsy performed with a biopsy needle (under ultrasonographic, fluoroscopic, or CT guidance) or through a thoracotomy should be contemplated. This procedure is associated with an extremely low morbidity and should be recommended if owners are considering treatment.

Metastatic lesions in other organs or tissues (e.g., liver, bone) can also be diagnosed on the basis of FNA findings. The clinician should remember that nodular lesions of the liver or spleen in dogs with a primary malignancy should not necessarily be considered metastatic. FNA or biopsies of such lesions frequently reveal normal hepatocytes (i.e., regenerative hepatic nodule) or extramedullary hematopoiesis/lymphoreticular hyperplasia, respectively. In the case of bone metastases, an aspirate can be obtained using a hypodermic needle (20-22G) that is inserted blindly or under ultrasonographic guidance; if this fail to yield cells, a 16 or 18 gauge bone marrow aspiration needle can be used. If a cytologic diagnosis cannot be made, a core (needle) biopsy can be performed.

As discussed in Chapter 76, cats and dogs with metastatic neoplasms can now be treated fairly successfully using chemotherapy. To do this, however, it is necessary to know the histologic (or cytologic) tumor type. The clinician should always bear in mind that euthanasia is a viable option for some owners.

APPROACH TO THE CAT OR DOG WITH A MEDIASTINAL MASS

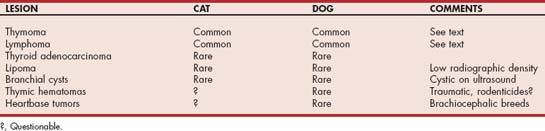

Several lesions are found as anterior mediastinal masses (AMMs) during physical examination or plain thoracic radiography (Table 79-2). Some of these lesions are malignant neoplasms; therefore diagnosis and treatment should be approached aggressively in such animals.

Clinicopathologic Features and Diagnosis

When evaluating a cat or dog with an AMM, the clinician should consider several issues before recommending a specific treatment. As discussed previously (see Chapter 76), the treatment prescribed depends on the specific tumor type (i.e., surgical excision may be curative for dogs and cats with thymomas, whereas chemotherapy is indicated for those with lymphoma). Because lymphomas and thymomas are the most common AMMs in small animals, the ensuing discussion is limited to these two neoplasms. Other neoplasms that originate in anterior mediastinal structures include chemodectomas (heartbase tumors), ectopic thyroid carcinomas, and lipomas, among others. Nonneoplastic lesions of the mediastinum include mainly thymic or mediastinal hematomas and ultimobranchial cysts.

Paraneoplastic syndromes, such as generalized or focal myasthenia gravis, polymyositis, exfoliative dermatitis, and second neoplasms, have been well characterized in cats and dogs with thymoma. Aplastic anemia, a paraneoplastic syndrome common in humans with thymoma, has not been recognized in small animals with this tumor type. Hypercalcemia is a common finding in dogs with mediastinal lymphoma, but it can also occur in dogs with thymoma.

In cats the age at the time of presentation points to a specific diagnosis. In other words, anterior mediastinal lymphomas are more common in young cats (1 to 3 years old), whereas thymomas are more common in older cats (8 to 10 years old). It is also important to know the feline leukemia virus (FeLV) status in this species because most cats with mediastinal lymphomas are viremic (i.e., FeLV-positive), whereas most cats with thymoma are not. We occasionally see FeLV-negative mediastinal lymphomas in young to middle-age Siamese cats.

In dogs most AMMs are diagnosed in older animals (older than 5 to 6 years of age); therefore age cannot be used as a means of distinguishing between lymphomas and thymomas. However, a large proportion of dogs with mediastinal lymphomas are hypercalcemic, whereas most dogs with thymoma are not (although hypercalcemia can also occur in dogs with this neoplasm). Peripheral lymphocytosis can be present in dogs and cats with either lymphoma or thymoma. The presence of neuromuscular signs in a dog or cat with an AMM suggests the existence of a thymoma.

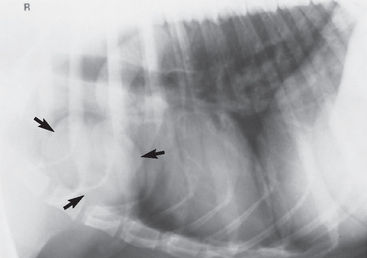

Thoracic radiographs are of little help in differentiating thymomas from lymphomas. The two neoplasms are similar in appearance, although lymphomas appear to originate more frequently in the dorsal anterior mediastinum, whereas thymomas originate more often in the ventral mediastinum (Fig. 79-1). The prevalence of pleural effusion in dogs and cats with either thymomas or lymphomas appears to be similar; thus the finding cannot be used as a means to distinguish between these two tumor types.

FIG 79-1 Typical radiographic features of thymoma (arrows) in a dog. The mass originates in the ventral mediastinum, unlike most lymphomas, which usually originate in the dorsal mediastinal region. Percutaneous fine-needle aspiration of this mass yielded findings diagnostic for thymoma, and the dog underwent a thoracotomy with complete resection of the mass.

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the AMM should be attempted before more invasive diagnostic techniques are used. Ultrasonographically, most thymomas have a mixed echogenicity, with discrete hypoechoic to anechoic areas that correspond to true cysts on cross section. The lack of a supporting stroma in lymphomas usually confers a hypoechoic to anechoic density to the mass, which therefore may look diffusely cystic. In addition to aiding in the presumptive diagnosis of a given tumor type, ultrasonography may provide information regarding the resectability of the mass and assists in obtaining a specimen for cytologic evaluation (see next paragraph). In patients with thymoma a thoracic CT scan may help in planning surgery.

Transthoracic FNA of AMMs constitutes a relatively safe and reliable evaluation technique. After sterile preparation of the thoracic wall overlying the mass (see Chapter 75), a 2- to 3-inch (5- to 7.5-cm), 25-gauge needle coupled to a syringe is used to aspirate the mass. This can be done blindly (if the mass is so large that it is pressing against the interior thoracic wall) or guided by radiography (using three views to establish a three-dimensional location), fluoroscopy, ultrasonography, or CT. Despite the fact that there are large vessels within the anterior mediastinum, postaspiration bleeding is extremely rare if the animal remains motionless during the procedure. Alternatively, if the mass is large enough to be in close contact with the internal thoracic wall, a transthoracic needle biopsy can be performed to allow histopathologic evaluation.

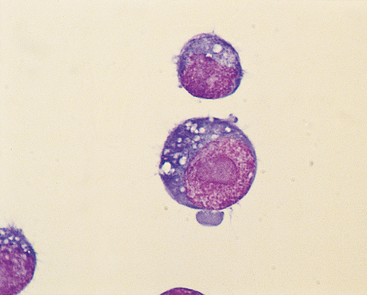

Cytologically, mediastinal lymphomas are composed of a monomorphic population of lymphoid cells that are mostly immature (i.e., low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, dark blue cytoplasm, clumped chromatin pattern, and nucleoli); in cats most cells in anterior mediastinal lymphomas are heavily vacuolated and resemble human Burkitt’s lymphoma cells (Fig. 79-2). Thymomas are cytologically heterogeneous and composed primarily of a population of small lymphocytes (although large blasts are sometimes present), and occasionally a distinct population of epithelial-like cells that are usually polygonal or spindle shaped and can be identified either as individual cells or in sheets. Hassall’s corpuscles are rarely seen in Wright’s-stained cytologic preparations. Plasma cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, mast cells, macrophages, and melanocytes are all occasionally seen.

Treatment

As discussed in preceding paragraphs, anterior mediastinal lymphomas are best treated with chemotherapy (see Chapter 80). Radiotherapy can also be used in conjunction with chemotherapy to induce a more rapid remission. However, in my experience, the combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy does not offer any advantages over chemotherapy alone, and it may indeed be detrimental to the animal, given that many cats and dogs with anterior mediastinal lymphoma have severe respiratory compromise at the time of presentation. Chemical restraint of these animals for radiotherapy may further compound this problem.

Because most thymomas are benign, surgical excision is usually curative. Although in some reports the perioperative morbidity and mortality of this procedure are high (Atwater et al., 1994), in our experience, most patients that undergo thoracotomies for removal of a thymoma do well and are released from the hospital in 3 to 4 days. We recently reviewed the surgical outcome in 9 cats and 11 dogs with thymomas (Zitz et al., 2008); eight out of nine cats and eight out of eleven dogs survived the immediate postoperative period and had median survival times of 30 and 18.5 months, respectively. Two cats and one dog had late recurrences.

Radiotherapy can successfully induce remission in patients with thymoma, although complete, long-lasting remission is rarely achieved. This may be because the radiotherapy eliminates only the lymphoid component of the neoplasm but the epithelial component remains unchanged. Chemotherapy may be beneficial in selected cats and dogs with nonresectable thymomas or in those in which repeated anesthetic episodes or a major surgical procedure poses a severe risk. We have used combination chemotherapy protocols commonly used for dogs and cats with lymphoma (i.e., cyclophosphamide, vincristine, cytosine arabinoside, and prednisone [COAP]; cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone [COP]; and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone [CHOP]; see Chapter 80) in a limited number of cats and dogs with cytologically diagnosed thymomas. As with radiotherapy, however, chemotherapy may only eliminate the lymphoid cell population, thus rarely resulting in complete or long-lasting remissions.

If a definitive diagnosis of thymoma or lymphoma cannot be obtained preoperatively, the clinician has two therapeutic options: (1) to perform a thoracotomy and excise the mass or (2) to initiate chemotherapy for lymphoma (COP, COAP, or CHOP). In the latter case, if no remission (or only a partial remission) is observed 10 to 14 days after the start of chemotherapy, the mass is most likely a thymoma and surgical resection should be considered.

Aronsohn MG, et al. Clinical and pathologic features of thymoma in 15 dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1984;184:1355.

Atwater SW, et al. Thymoma in dogs: 23 cases (1980–1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994;205:1007.

Bellah JR, et al. Thymoma in the dog: two case reports and review of 20 additional cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;183:1095.

Carpenter JL, et al. Thymoma in 11 cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1982;181:248.

Lana S, et al. Diagnosis of mediastinal masses in dogs by flow cytometry. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:1161.

Liu S, et al. Thymic branchial cysts in the dog and cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;182:1095.

Nemanic S, London CA, Wisner ER. Comparison of thoracic radiographs and single breath-hold helical CT for detection of pulmonary nodules in dogs with metastatic neoplasia. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:508.

Rae CA, et al. A comparison between the cytological and histological characteristics in thirteen canine and feline thymomas. Can Vet J. 1989;30:497.

Scott DW, et al. Exfoliative dermatitis in association with thymoma in 3 cats. Fel Pract. 1995;23:8.

Suter PJ, et al. Radiographic recognition of primary and metastatic pulmonary neoplasms of dogs and cats. J Am Vet Radiol Soc. 1974;15:3.

Yoon J, et al. Computed tomographic evaluation of canine and feline mediastinal masses in 14 patients. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2004;45:542.

Zitz JC, et al. Thymoma in cats and dogs: 20 cases (1984-2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;232:1186.