CHAPTER 81 Leukemias

DEFINITIONS AND CLASSIFICATION

Leukemias are malignant neoplasms that originate from hematopoietic precursor cells in the bone marrow. Because these cells are unable to undergo terminal differentiation or apoptosis, they self-replicate as a clone of usually immature (and nonfunctional) cells. The neoplastic cells may or may not appear in peripheral circulation; thus the confusing terms aleukemic and subleukemic are used to refer to leukemias in which neoplastic cells proliferate within the bone marrow but are absent or scarce in the circulation.

Leukemias can be classified philogenetically into two broad categories according to the cell line they originate from: lymphoid and myeloid (or nonlymphoid; Table 81-1). The term myeloproliferative disease or disorder has also been used to refer to myeloid leukemias (mainly to the acute forms). On the basis of their clinical course and the cytologic features of the leukemic cell population, leukemias can also be classified as acute or chronic. Acute leukemias are characterized by an aggressive biologic behavior (i.e., death ensues shortly after diagnosis if the patient is not treated) and by the presence of immature (blast) cells in bone marrow or blood. Chronic leukemias have a protracted, often indolent course, and the predominant cell is a well-differentiated, late precursor (i.e., lymphocyte in chronic lymphocytic leukemia [CLL] and neutrophil in chronic myeloid leukemia [CML]). In dogs (and possibly in cats) CML can undergo blast transformation (blast crisis), during which the disease behaves like an acute leukemia and is usually refractory to therapy. Blast crises do not appear to occur in dogs or cats with CLL.

TABLE 81-1 Classification of Leukemias in Dogs and Cats

TABLE 81-1 Classification of Leukemias in Dogs and Cats

| CLASSIFICATION | SPECIES |

|---|---|

| Acute Leukemias | |

| Acute myeloid (myelogenous) leukemia (AML) | |

| Undifferentiated myeloid leukemia (AML-Mo) | D, C |

| Acute myelocytic leukemia (AML-M1-2) | D, C |

| Acute progranulocytic leukemia (AML-M3) | — |

| Acute myelomonocytic leukemia (AMML; AML-M4) | D, C |

| Acute monoblastic/monocytic leukemia (AMoL; AML-M5) | D, C |

| Acute erythroleukemia (AML-M6) | C, D |

| Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AML-M7) | D, C |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | |

| ALL-I-! | D, C |

| ALL-L2 | D, C |

| ALL-L3 | C, D |

| Acute leukemia of large granular lymphocytes (LGL) | D, C |

| Subacute and Chronic Leukemias | |

| Chronic myeloid (myelocytic) leukemia (CML) | D > C |

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) | D |

| Chronic lymphoid (lymphocytic) leukemia (CLL) | D > C |

| Large granular lymphocyte (LGL) variant | D |

D, Dog; C, cat;  , unknown.

, unknown.

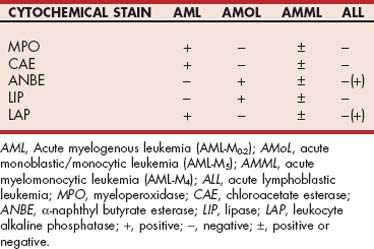

Acute leukemias may be difficult to classify morphologically as myeloid or lymphoid on the basis of the evaluation of Giemsa- or Wright’s-stained blood or bone marrow smears because poorly differentiated blasts look similar under the light microscope. In veterinary medicine cytochemical stains are used routinely in several diagnostic laboratories to establish whether the blasts are lymphoid or myeloid and also to subclassify myeloid leukemias, as described later (i.e., myeloid versus monocytic versus myelomonocytic). These cytochemical stains reveal the presence of different enzymes in the cytoplasm of the blasts, which aids in establishing their origin (Table 81-2).

Immunophenotyping of canine and feline leukemic cells using monoclonal antibodies is now available in teaching institutions and some commercial diagnostic laboratories; however, clinical correlations between immunophenotype and prognosis have not yet been established, although it appears that certain phenotypes may be associated with poor prognosis.

A classification scheme for acute leukemia in people was devised by a group of French, American, and British investigators (the FAB scheme) and was based on the morphologic features of the cells in Giemsa-stained smears of blood and bone marrow and the clinical presentation and biologic behavior of the disease. Because this scheme has not yet proved to be prognostically or therapeutically applicable to cats or dogs, it is not discussed here (see Suggested Readings for additional information on the FAB scheme in people and animals).

The terms preleukemic syndrome and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS, or myelodysplasia) refer to a syndrome of hematopoietic dysfunction and specific cytomorphologic changes that precedes the development of acute myelogenous leukemia by months to years. The syndrome is characterized by cytopenias and a hypercellular bone marrow and appears to be more common in cats than in dogs. The clinical and hematologic features of cats and dogs with MDS are discussed at the end of this chapter.

LEUKEMIAS IN DOGS

In dogs leukemias constitute fewer than 10% of all hemolymphatic neoplasms and are therefore considered rare. At our hospital the leukemia : lymphoma ratio is approximately 1 : 7 to 1 : 10. However, this ratio is artificially high because most dogs with lymphoma are treated by their local veterinarians, whereas most dogs with leukemia are referred for treatment. Although most leukemias in dogs are considered to be spontaneous in origin, radiation and viral particles have been identified as etiologic factors in some experimental dogs with this disease.

ACUTE LEUKEMIAS

Prevalence

Acute myeloid leukemias are more common than acute lymphoid leukemias in dogs, constituting approximately three fourths of the cases of acute leukemia. It should be remembered, however, that morphologically (i.e., as determined by evaluation of a Wright’s- or Giemsa’s-stained blood or bone marrow smear), most acute leukemias are initially classified as lymphoid. After cytochemical staining of the smears or immunophenotyping is performed, approximately one third to one half of them are then reclassified as myeloid.Approximately half of the dogs with myeloid leukemia have myelomonocytic differentiation when cytochemical staining or immunophenotyping is performed (see Table 81-2).

Clinical Features

The clinical signs and physical examination findings in dogs with acute leukemia are usually vague and nonspecific (Table 81-3). Most owners seek veterinary care when their dogs become lethargic or anorectic or when persistent or recurrent fever, weight loss, shifting limb lameness, or other nonspecific signs develop; neurologic signs occur occasionally. Some of these signs may be quite acute (e.g., days). Spleno megaly, hepatomegaly, pallor, fever, and mild generalized lymphadenopathy are commonly detected during routine physical examination. The spleen in these dogs is usually markedly enlarged, and it has a smooth surface on palpation. Careful inspection of the mucous membranes in dogs with acute leukemia often reveals petechiae, ecchymoses, or both, in addition to pallor. Icterus may also be detected if marked leukemic infiltration of the liver has occurred. The generalized lymphadenopathy seen in dogs with acute leukemia is usually mild, in contrast to that seen in dogs with lymphoma, in which the lymph nodes are massively enlarged. In other words, the hepatosplenomegaly is more striking than the lymphadenopathy. Most dogs with leukemia also have constitutional signs (i.e., they are clinically ill), whereas most dogs with lymphoma are asymptomatic. Although it is usually impossible to distinguish between acute myeloid and acute lymphoid leukemia on the basis of physical examination findings alone, some subtle differences do exist: Mainly, shifting limb lameness, fever, and ocular lesions are more common in dogs with acute myeloid leukemia, whereas neurologic signs are more common in dogs with acute lymphoid leukemia.

TABLE 81-3 Clinical Signs and Physical Examination Findings in Dogs and Cats with Acute Leukemias*

TABLE 81-3 Clinical Signs and Physical Examination Findings in Dogs and Cats with Acute Leukemias*

| FINDING | DOG | CAT |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Sign | ||

| Lethargy | >70 | >90 |

| Anorexia | >50 | >80 |

| Weight loss | >30-40 | >40-50 |

| Lameness | >20-30 | > > > |

| Persistent fever | >30-50 | > |

| Vomiting/diarrhea | >20-40 | > |

| Physical Examination Finding | ||

| Splenomegaly | >70 | >70 |

| Hepatomegaly | >50 | >50 |

| Lymphadenopathy | >40-50 | >20-30 |

| Pallor | >30-60 | >50-70 |

| Fever | >40-50 | >40-60 |

Unknown.

Unknown.

* Results are expressed as the approximate percentage of animals showing the abnormality.

Hematologic Features

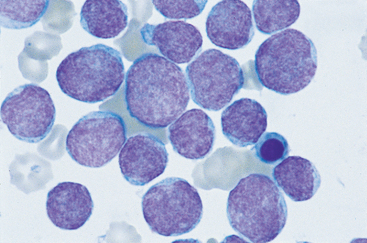

Marked hematologic changes are usually present in dogs with acute leukemia. Couto (1985) and Grindem et al. (1985b) have published detailed reviews of the hematologic features of dogs with acute leukemia. Briefly, abnormal (leukemic) cells are observed in the peripheral blood of most dogs with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), although this is slightly more common in the latter (i.e., circulating blasts are absent in some dogs with AML; Fig. 81-1). Isolated cytopenias, bicytopenias, or pancytopenia is present in almost all dogs with AML and ALL. Leukoerythroblastic reactions are detected in approximately half of dogs with AML but are rare in dogs with ALL. The total white blood cell (WBC) and blast counts are highest in dogs with ALL (median, 298,200/μl; range, 4000 to 628,000/μl), and as a general rule, only dogs with ALL have WBC counts greater than 100,000/μl. Most dogs with AML and ALL are anemic, but dogs with acute monoblastic/monocytic leukemia (AMoL or AML-M5) have the least severe anemia (packed cell volume of 30% versus 23% in all other groups). Most dogs with acute leukemias are also thrombocytopenic, although the thrombocytopenia also appears to be less severe in dogs with AML-M5 (median, 102,000/μl; range, 39,000 to 133,000/μl).

Diagnosis

A presumptive diagnosis in dogs with acute leukemia is usually made on the basis of the history and physical examination findings; a CBC is usually confirmatory, although the hematologic changes in dogs with “aleukemic leukemia” may resemble those of ehrlichiosis or other bone marrow disorders. To evaluate the extent of the disease, a bone marrow aspirate or biopsy is indicated. Splenic, hepatic, or lymph node aspirates for cytologic evaluation can also be obtained easily, although the information yielded may not help in establishing the diagnosis or prognosis. For example, if a dog has mild generalized lymphadenopathy and the only sample submitted to a laboratory is a lymph node, spleen, or liver aspirate, the finding of undifferentiated blasts in the smear points toward a cytologic diagnosis of either acute leukemia or lymphoma (i.e., the neoplastic lymphoid cells in lymphoma and leukemia are indistinguishable morphologically); indeed, it is quite common for the clinical pathologist to issue a diagnosis of lymphoma because it is the most common of the two diseases. In these cases, further clinical and clinicopathologic information (i.e., the degree and extent of lymphadenopathy, presence and degree of hepatosplenomegaly, hematologic and bone marrow biopsy or aspiration findings) is required to establish a definitive diagnosis.

It may be difficult to diagnose the tumor type in a dog with generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and a low number of circulating lymphoblasts. The main differential diagnoses are ALL and lymphoma with circulating blasts (lymphosarcoma cell leukemia). It is important to differentiate between these two disorders because the prognosis for dogs with lymphoma is considerably better than that for dogs with acute leukemia. These two entities may be difficult to distinguish on the basis of the clinical, hematologic, and cytologic information obtained, but the guidelines found in Box 81-1 can be used to try to arrive at a definitive diagnosis.

BOX 81-1 Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia or Lymphoma with Circulating Blasts (Lymphosarcoma Cell Leukemia): Guidelines for a Definitive Diagnosis

BOX 81-1 Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia or Lymphoma with Circulating Blasts (Lymphosarcoma Cell Leukemia): Guidelines for a Definitive Diagnosis

When the neoplastic cells are poorly differentiated, cytochemical staining or immunophenotyping is required to establish a definitive diagnosis (see Table 81-2). This is important if the owner is contemplating treatment because the therapy and prognosis for dogs with AML are different from those for dogs with ALL (i.e., the survival time in dogs with AML is shorter than that in dogs with ALL).

In addition to lymphoma, differential diagnoses in dogs with acute or chronic leukemias include other disorders of the mononuclear-phagocytic or hematopoietic systems, such as malignant or systemic histiocytosis; systemic mast cell disease (mast cell leukemia); and infectious diseases such as ehrlichiosis, bartonellosis, mycoplasmosis, and mycobacteriosis. Box 81-2 lists the basic principles of diagnosis that apply to all dogs with suspected leukemia.

BOX 81-2 Basic Diagnostic Principles for Dogs with Suspected Leukemia

BOX 81-2 Basic Diagnostic Principles for Dogs with Suspected Leukemia

The diagnosis of acute leukemia can be extremely straightforward (i.e., a dog that is evaluated because of weight loss, lethargy, hepatosplenomegaly, pallor, and central nervous system [CNS] signs and that has a WBC of more than 500,000/μl, most of which are blasts, is most likely to have ALL), or it may represent a challenge (i.e., a dog with unexplained cytopenias of prolonged duration in which aleukemic AML-M1 subsequently develops).

Treatment

The treatment of dogs with acute leukemias is usually unrewarding. Most dogs with these diseases respond poorly to therapy, and prolonged remissions are rare. Treatment failure usually stems from one or more of the following factors:

Prolonged remissions in dogs with AML treated with chemotherapy are extremely rare. In most dogs with AML remissions in response to any of the protocols listed in Box 81-3 are rarely observed. If animals do respond, the remission is usually extremely short-lived and survival rarely exceeds 3 months. In addition, more than half of the dogs die during induction as a result of sepsis or bleeding. Furthermore, the supportive treatment required in these patients (e.g., blood component therapy, intensive care monitoring) is financially unacceptable to most owners, and the emotional strain placed on the owner is also quite high. Therefore owners should be aware of all these factors before deciding to treat their dogs.

BOX 81-3 Chemotherapy Protocols for Dogs and Cats with Acute Leukemias

BOX 81-3 Chemotherapy Protocols for Dogs and Cats with Acute Leukemias

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

1. OP protocol

Vincristine, 0.5 mg/m2 IV once a week

Prednisone, 40-50 mg/m2 PO q24h for a week; then 20 mg/m2 PO q48h

2. COP protocol

Vincristine, 0.5 mg/m2 IV once a week

Prednisone, 40-50 mg/m2 PO q24h for a week; then 20 mg/m2 PO q48h

3. LOP protocol

Vincristine, 0.5 mg/m2 IV once a week

Prednisone, 40-50 mg/m2 PO q24h for a week; then 20 mg/m2 PO q48h

l-Asparaginase, 10,000-20,000 IU/m2 IM or SC once every 2-3 weeks

4. COAP protocol

Vincristine, 0.5 mg/m2 IV once a week

Prednisone, 40-50 mg/m2 PO q24h for a week; then 20 mg/m2 PO q48h

Cyclophosphamide, 50 mg/m2 PO q48h

Cytosine arabinoside, 100 mg/m2 SC daily for 2-4 days*

Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

Cytosine arabinoside, 5-10 mg/m2 SC q12h for 2-3 weeks; then on alternate weeks

Cytosine arabinoside, 100-200 mg/m2 in IV drip over 4 hours

Mitoxantrone, 4-6 mg/m2 in IV drip over 4 hours; repeat every 3 weeks

IV, Intravenous; PO, by mouth; IM, intramuscular; SC, subcutaneous.

* The daily dose should be divided into two to four daily administrations

The prognosis may be slightly better in dogs with ALL; however, responses to treatment and survival times in these patients are considerably lower than those in dogs with lymphoma. The remission rates in dogs with ALL are approximately 20% to 40%, in contrast with those in dogs with lymphomas, which approach 90%. Survival times with chemotherapy in dogs with ALL are also shorter (average, 1 to 3 months) than those in dogs with lymphoma (average, 12 to 18 months). Untreated dogs usually live less than 2 weeks. Chemotherapy protocols used in dogs with acute leukemia are listed in Box 81-3.

CHRONIC LEUKEMIAS

Prevalence

In dogs CLL is far more common than CML; in addition, the latter is poorly characterized. At our hospital we evaluate approximately six to eight dogs with CLL a year, whereas we evaluate approximately one dog with CML every 3 to 5 years. CLL is one of the leukemias most commonly diagnosed at diagnostic referral laboratories.

Clinical Features

Like their acute counterparts, the clinical signs in dogs with CLL or CML are vague and nonspecific; however, there is a history of chronic (i.e., months), vague clinical signs in approximately half of the dogs with chronic leukemia. Many cases of chronic leukemia are diagnosed incidentally during routine physical examination and clinicopathologic evaluation (i.e., dogs are asymptomatic). Clinical signs in dogs with CLL include lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, mildly enlarged lymph nodes, intermittent diarrhea or vomiting, and weight loss. As mentioned previously, more than half of the dogs with CLL are asymptomatic and are diagnosed serendipitously. Physical examination findings in dogs with CLL include mild generalized lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, pallor, and pyrexia. The clinical signs and physical examination findings in dogs with CML appear to be similar to those in dogs with CLL.

A terminal event in dogs with CLL is the development of a diffuse large cell lymphoma, termed Richter syndrome; in humans Richter syndrome also includes prolymphocytic leukemia, acute eukemia, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In dogs Richter syndrome is characterized by a massive, generalized lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. Once this multicentric lymphoma develops, chemotherapy-induced, long-lasting remissions are difficult to obtain and survival times are short.

Blast crisis, which involves the appearance of immature blast cells in blood and bone marrow, occurs in humans and dogs with CML months to years after the initial diagnosis is made; in humans with CLL acute leukemias are part of the Richter syndrome. In humans with blast crisis associated with CML these blasts are of either myeloid or lymphoid phenotype; the origin of the blast cell in dogs with blast crises has not been determined. Blast crises occurred in five of eleven dogs with CML described in the literature (Leifer et al., 1983). Blast crises do not appear to occur in dogs with CLL.

Hematologic Features

The most common hematologic abnormality in dogs with CLL is a marked lymphocytosis resulting in leukocytosis. The lymphocytes are usually morphologically normal, although large granular lymphocytes (LGLs) are occasionally present. The lymphocyte counts range from 8000/μl to more than 100,000/μl, but lymphocyte counts of more than 500,000/μl are rare. In most dogs with CLL the neoplastic cell population is of T-cell origin. In addition to the lymphocytosis, which may be diagnostic in itself (e.g., a dog with a lymphocyte count of 100,000/μl most certainly has CLL), anemia is detected in more than 80% of the dogs and thrombocytopenia in approximately half of the dogs. Although cytologic evaluation of bone marrow aspirates in dogs with CLL usually reveals the presence of many morphologically normal lymphocytes, normal numbers of lymphocytes are occasionally detected. This is probably because the lymphocytosis in some animals with CLL stems from disorders of recirculation rather than from the increased clonal proliferation of lymphocytes in the bone marrow.

Monoclonal gammopathies have been reported in approximately two thirds of dogs with CLL in which serum was evaluated using protein electrophoresis (Leifer et al., 1986). The monoclonal component is usually IgM, but IgA and IgG components have also been reported. This monoclonal gammopathy can lead to hyperviscosity. Rarely, dogs with CLL have paraneoplastic, immune-mediated blood disorders (e.g., hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia). However, in my experience, monoclonal gammopathies are uncommon in dogs with CLL.

The hematologic features of CML in dogs are poorly characterized but include leukocytosis with a left-shift down to myelocytes (or occasionally myeloblasts), anemia, and possibly thrombocytopenia, although thrombocytosis can also occur. The hematologic findings seen during a blast crisis are indistinguishable from those seen in dogs with AML or ALL.

Diagnosis

Absolute lymphocytosis is the major diagnostic criterion for CLL in dogs. Although other diseases (e.g., ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, leishmaniasis, Chagas’ disease, Addison’s disease) should be considered in the differential diagnosis of dogs with mild lymphocytosis (i.e., 7000 to 20,000/μl), marked lymphocytosis (i.e., more than 20,000/μl) is almost pathognomonic for CLL. If the physical examination and hematologic abnormalities discussed in previous paragraphs (i.e., mild lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, monoclonal gammopathy, anemia) are found, this may help establish a diagnosis of CLL in dogs with lymphocytosis, although all these changes can also be present in dogs with chronic ehrlichiosis (see Chapter 96). In patients with lymphocytosis in which a confirmatory diagnosis of CLL cannot be made, a PCR assay for clonality will typically reveal if the cells are clonal in origin. The phenotypic distribution after performing immunophenotyping may also establish if the cell population is monoclonal or polyclonal.

The diagnosis of CML may be challenging, particularly because this syndrome is poorly characterized in dogs. Some of the markers used to diagnose CML in humans are of no use in dogs. For example, the Philadelphia 1 chromosome and the alkaline phosphatase score were originally used in humans to differentiate CML from leukemoid reactions (i.e., CML cells have the Philadelphia 1 chromosome, and the alkaline phosphatase content of the neutrophils increases in the setting of leukemoid reactions and decreases in the setting of CML). Chromosamal analysis of the cells in question may reveal specific abnormalities that support a diagnosis of CML. As a general rule, a final diagnosis of CML should be made only after the clinical and hematologic findings have been carefully evaluated and the inflammatory and immune causes of neutrophilia have been ruled out.

Treatment

The clinician usually faces the dilemma of whether to treat a dog with CLL. If the dog is symptomatic, has organomegaly, or has concurrent hematologic abnormalities, treatment with an alkylator (with or without corticosteroids) is indicated. If there are no paraneoplastic syndromes (i.e., immune hemolysis or thrombocytopenia, monoclonal gammopathies), I recommend using single-agent chlorambucil at a dosage of 20 mg/m2 given orally once every 2 weeks (Box 81-4). If there are paraneoplastic syndromes, the addition of corticosteroids (prednisone, 50 to 75mg/m2 by mouth [PO] q24h for 1 week, then 25 mg/m2 PO q48h) may be beneficial.

BOX 81-4 Chemotherapy Protocols for Dogs and Cats with Chronic Leukemias

BOX 81-4 Chemotherapy Protocols for Dogs and Cats with Chronic Leukemias

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Chlorambucil, 20 mg/m2 PO once every 2 weeks

Chlorambucil as above, plus prednisone, 50 mg/m2 PO q24h for a week; then 20 mg/m2 PO q48h

COP protocol

Cyclophosphamide, 200-300 mg/m2 IV once every 2 weeks

Vincristine, 0.5-0.75 mg/m2 IV once every 2 weeks (alternating weeks with the cyclophosphamide)

Prednisone as in protocol 2; this treatment is continued for 6-8 weeks, at which time protocol 1 or 2 can be used for maintenance

Because the growth fraction of neoplastic lymphocytes in CLL appears to be low, a delayed response to therapy is common. In a high proportion of dogs with CLL treated with chlorambucil or chlorambucil and prednisone, it may take more than 1 month (and as long as 6 months) for the hematologic and physical examination abnormalities to resolve. This is in contrast to dogs with lymphoma and acute leukemias, in which remission is usually induced in 2 to 7 days.

The survival times in dogs with CLL are quite long. Indeed, even without treatment, survival times of more than 2 years are common. More than two thirds of the dogs with CLL treated with chlorambucil (with or without prednisone) at our clinic have survived in excess of 2 years. In fact, most dogs with CLL do not die as a result of leukemia-related causes but rather of other senior disorders.

The treatment of dogs with CML using hydroxyurea (see Box 81-4) may result in prolonged remission, provided a blast crisis does not occur. However, the prognosis does not appear to be as good as that for dogs with CLL (i.e., survivals of 4 to 15 months with treatment). The treatment of blast crises is usually unrewarding. A novel therapeutic approach targeting tyrosine kinase in the neoplastic cells of humans with CML using imatinib (Gleevec) has shown to be beneficial in inducing remission; however, the drug is hepatotoxic in dogs. New small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors are currently under investigation in dogs with CML and other diseases associated with c-kit mutations.

LEUKEMIAS IN CATS

ACUTE LEUKEMIAS

Prevalence

True leukemias are rare in the cat, constituting fewer than 15% of all hematopoietic neoplasms. Although exact figures regarding the incidences of leukemias and lymphomas are not available for cats, these neoplasms are now rare.

If cytochemical staining or immunophenotyping is used to classify acute leukemias in cats, approximately two thirds are myeloid and one third are lymphoid. However, in contrast to dogs, myelomonocytic leukemias (M4) appear to be rare in cats.

Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) is commonly implicated as a cause of leukemias in cats; however, the role of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) in the pathogenesis of these neoplasms is still unclear. Originally, it was reported that approximately 90% of cats with lymphoid and myeloid leukemias tested positive for FeLV p27 with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or immunofluorescence. As discussed in Chapter 80, because the prevalence of FeLV infection is decreasing, most cats with leukemia diagnosed in our clinic over the past few years have not been viremic for FeLV (i.e., they are FeLV-negative).

Clinical Features

The clinical features and physical examination findings in cats with acute leukemias are similar to those in dogs and are summarized in Table 81-3. Shifting limb lameness and neurologic signs do not appear to be as common in cats as in dogs with myeloid leukemias.

Hematologic Features

More than three fourths of cats with AML and ALL have cytopenias; leukoerythroblastic reactions are common in cats with AML but extremely rare in those with ALL. In contrast to dogs, circulating blasts appear to be more common in cats with AML than in those with ALL.

Sequential studies of cats with myeloid leukemias have revealed that the cytomorphologic features can change from one cell type to another over time (e.g., sequential diagnoses of erythremic myelosis, erythroleukemia, and acute myeloblastic leukemia are common in a given cat). This is one of the reasons that most clinical pathologists prefer the term myeloproliferative disorder (MPD) to refer to this leukemia in cats.

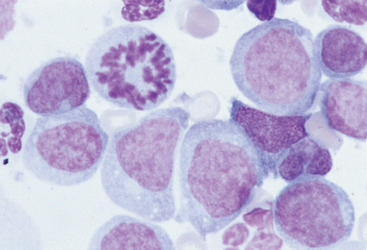

Diagnosis and Treatment

The diagnostic evaluation of cats with suspected acute leukemia follows the same general sequence as that for dogs. If the changes in the CBC are not diagnostic, a bone marrow aspirate can provide information that may confirm the diagnosis (Fig. 81-2). In addition, cats with suspected or confirmed acute leukemias should be evaluated for circulating FeLV p27 and for serum antibodies against FIV.

FIG 81-2 Bone marrow aspirate from a cat with peripheral blood cytopenias and absence of circulating blasts. Note the predominance of large immature myeloid cells, characterized by round to kidney-shaped nuclei. A mitotic figure is evident. (×1000.)

With treatment cats with ALL apparently have better survival times than cats with AML. Survival times in cats with ALL treated with multichemotherapy range from 1 to 7 months.

There have been several published reports of cats with myeloid leukemias treated with single-agent or combination chemotherapy. The treatment protocols have included single-agent cyclophosphamide or cytosine arabinoside, as well as combinations of cyclophosphamide, cytosine arabinoside, and prednisone; cytosine arabinoside and prednisone; cyclophosphamide, vinblastine, cytosine arabinoside, and prednisone; and doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone. Survival times in these cats have usually ranged from 2 to 10 weeks, with a median of approximately 3 weeks. Therefore, as in dogs, intensive chemotherapy does not appear to be beneficial in cats with acute leukemias.

New alternatives for the therapy of feline MPD are currently being explored. Low-dose cytosine arabinoside (LDA; 10 mg/m2 subcutaneously q12h; Cytosar-U; Upjohn, Kalamazoo, Mich) has been used as an inductor of differentiation of the neoplastic clone. In several studies this treatment was observed to induce complete or partial remission in 35% to 70% of humans with MDS and MPD. Moreover, although myelosuppression was observed in some patients, the treatment was exceedingly well tolerated and associated with minimal toxicity.

We have treated several cats with MPD using LDA and have observed in most complete or partial remissions, with transient hematologic improvement. Although no major toxicities were seen, the remissions were short-lived (3 to 8 weeks).

CHRONIC LEUKEMIAS

Chronic leukemias are are becoming more common in cats; this may be due to the relative decrease in the prevalence of acute leukemias, or it may represent a true phenomenon. CLL is occasionally found incidentally during routine physical examination. More often, cats with CLL are seen by a veterinarian because of a protracted history of vague signs of illness, including anorexia, lethargy, and gastrointestinal tract signs. In cats with CLL mature, well-differentiated lymphocytes predominate in peripheral blood and bone marrow, and the response to therapy appears to be good. In most cats with CLL the leukemic population is of T-cell origin. Most cats with CLL evaluated at our clinic showed a complete remission in response to chlorambucil with or without prednisone treatment. As in dogs, CML is poorly characterized in cats.

Antognoni MT, et al. Acute myeloid leukaemia in five dogs: clinical findings and cytochemical characterization. Vet Res Commun. 2003;27((Suppl) 1):367.

Avery AC, Avery PR. Determining the significance of persistent lymphocytosis. Vet Clin N Am Small Anim Pract. 2007;37:267.

Bennett JM, et al. Proposal for the classification of acute leukemias. Br J Haematol. 1976;33:451.

Blue JT, et al. Non-lymphoid hematopoietic neoplasia in cats: a retrospective study of 60 cases. Cornell Vet. 1988;78:21.

Cotter SM. Treatment of lymphoma and leukemia with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone. II. Treatment of cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1983;19:166.

Comazzi S, et al. Flow cytometric expression of common antigens CD18/CD45 in blood from dogs with lymphoid malignancies: a semi-quantitative study. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2006;112:243.

Comazzi S, et al. Flow cytometric patterns in blood from dogs with non-neoplastic and neoplastic hematologic diseases using double labeling for CD18 and CD45. Vet Clin Pathol. 2006;35:47.

Couto CG. Clinicopathologic aspects of acute leukemias in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186:681.

Facklam NR, et al. Cytochemical characterization of feline leukemic cells. Vet Pathol. 1986;23:155.

Grindem CB, et al. Morphological classification and clinical and pathological characteristics of spontaneous leukemia in 10 cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1985;21:227.

Grindem CB, et al. Morphological classification and clinical and pathological characteristics of spontaneous leukemia in 17 dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1985;21:219.

Jain NC, et al. Proposed criteria for classification of acute myeloid leukemia in dogs and cats. Vet Clin Pathol. 1991;20:63.

Lachowicz JL, Post GS, Brodsky E. A phase I clinical trial evaluating imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) in tumor-bearing cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:860.

Leifer CE, et al. Chronic myelogenous leukemia in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;183:686.

Leifer CE, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the dog: 22 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;189:214.

Matus RE, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the dog: a review of 30 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;183:859.

Weiss DJ. Flow cytometric and immunophenotypic evaluation of acute lymphocytic leukemia in dog bone marrow. J Vet Intern Med. 2001;15:589.

Weiss DJ, et al. Primary myelodysplastic syndromes of dogs: a report of 12 cases. J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14:491.

Weiss DJ. A retrospective study of the incidence and the classification of bone marrow disorders in the dog at a veterinary teaching hospital (1996-2004). J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:955.

Wellman ML, et al. Lymphocytosis of large granular lymphocytes in three dogs. Vet Pathol. 1989;26:158.

Wilkerson MJ, et al. Lineage differentiation of canine lymphoma/leukemias and aberrant expression of CD molecules. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;106:179.

Workman HC, Vernau W. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia in dogs and cats: the veterinary perspective. Vet Clin N Am Small Anim Pract. 2003;33:1379.