Preoperative Patient Considerations

After completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Understand the importance of and be able to perform a complete physical examination on the day of a scheduled surgery.

• Know the legal significance of a signed surgical consent form.

• Explain to clients the details in a surgical consent form.

• Collect and analyze preanesthesic diagnostic tests.

• Describe what is considered a minimum database for particular patients.

• Bring the veterinarian’s attention to any abnormal or invalid results.

• Understand the reasons for premedicating surgical patients.

• Explain the importance of preemptive analgesia.

• Describe the drug options available for preemptive analgesia.

• Explain the mechanisms of action of the different types of analgesics.

• Discuss the indications for placement of an intravenous (IV) catheter.

• Identify appropriate sites for placement of IV catheters.

• List the supplies required for IV catheter placement.

• Discuss the technique for IV catheterization of peripheral vessels.

• Identify the components of an endotracheal (ET) tube.

• Discuss factors considered for determining ET tube size.

• List supplies required for endotracheal intubation.

• Identify the anatomic structures of the larynx.

• Discuss the differences between the one-person technique and the two-person technique of performing endotracheal intubation.

• Discuss methods of assessing proper ET tube placement.

• Describe hair removal protocols for a variety of soft tissue, orthopedic, neurologic, and miscellaneous surgical cases.

• List antiseptic products available for use to prepare patients for surgery.

• Discuss different patterns used in applying materials for the surgical preparation.

• Discuss potential patient reactions from clipper or chemical irritation.

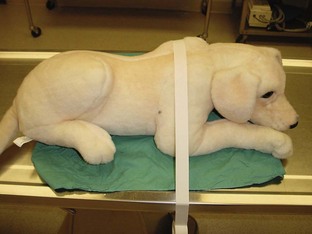

• Secure the patient to the surgery table in a safe, accessible manner.

• Properly position the patient for various surgical procedures, providing access to the (1) surgical site, (2) IV catheter site, (3) ET tube, (4) other venous access sites, and (5) monitoring sites.

• Perform a sterile preparation of the surgical site.

History Taking

The ability to collect a history that is both concise and chronologically accurate is a skill that takes practice. After the client (owner, guardian) and patient (animal) have been brought into the examination room and introductions have been made, a good starting point for collecting the history is to confirm the patient’s signalment. Confirming the patient’s age, gender, and breed with the owner, then comparing this information with the patient’s medical record, ensures the record’s accuracy and clarifies any confusion should a discrepancy be found.

Once the patient’s signalment has been established and verified, the client should be asked about the chief complaint (or reason for the visit). This is usually a brief but complete description of the current problem; for example, “HBC [hit by car] 2 days ago and fractured right femur.” Once the chief complaint has been established or confirmed, ask the client to explain the sequence of events, starting from the beginning of the particular problem.

While collecting a history, the technician should avoid asking leading questions. Leading questions make the client feel compelled to answer a certain way; for example, “You don’t feed your dog anything other than dog food, do you?” The owner feels compelled to answer in the negative because the question is leading toward or encouraging a specific answer. Formatting the question in a different way encourages the owner to answer the question truthfully, without prejudice. “What do you feed your dog?” is a nonleading, nonthreatening question that usually yields more useful information than the first example. Follow-up questions should be asked when appropriate. If there is a concern regarding the dog’s nutritional status or body condition, it would be appropriate to ask how much and how often the dog is fed, in addition to what the dog is fed. A concluding question for the specific topic is often revealing as well. A final question about the dog’s diet could be asked as follows: “Is there anything else your dog eats?” Again, this is a nonleading question and allows the owner to share information that may be helpful or even significant.

During the history it is important to review what other treatments have been tried to address the current problem, including any attempts by the owner to treat the problem at home. In addition, it is important to establish the nature of the treatment and the patient’s response to each treatment. A review of the current medications and supplements that the animal may be given, including both over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription medications, is an important part of the history. Certain medications and supplements may interact with diagnostic tests or premedications and anesthetic drugs.

Once the history of the current problem has been thoroughly investigated, a general question about any previous medical problems is appropriate. If a patient has had surgery or medical treatment in the past, additional follow-up questions may be in order. A good way to conclude the history-taking session is to ask the owner whether there is anything else that would be helpful to know but that was not addressed. Occasionally, this general question reminds clients about something else that is relevant to the situation or that they wanted to ask.

Allowing the animal to explore the examination room at will (e.g., letting the cat out of the carrier) during the history taking helps the technician determine the patient’s general attitude and condition without even touching it. In addition, most animals will take this opportunity to familiarize themselves with the scents and sounds of the hospital, and they may even relax if given a chance to explore the exam room on their own terms. An observant technician can establish a first impression of the patient’s personality and degree of anxiety during the history.

After the history has been collected, the details need to be recorded in chronologic order in the medical record.

Physical Examination

The veterinary technician should be adept in the performance of the physical examination (PE), even though veterinarians may elect to perform the PE themselves. The veterinary medical team will consult the PE findings when determining the appropriate anesthetic and surgical protocols for the patient. The owner’s presence during the PE allows for ongoing communication between the technician or veterinarian and the owner in regard to the findings and provides a historical perspective to unusual findings. This is especially true for any physical findings that might affect the surgical procedure or anesthetic protocols (e.g., retained testicles, pregnancy).

The complete PE should become a routine for the veterinary technician. This routine should be carried out in the same manner every time the PE is performed (e.g., head to tail or by body systems). This approach minimizes the possibility of forgetting to check a vital system and helps ensure patient safety. Being able to perform a complete PE is the first step in being the patient’s advocate. The PE reveals the needs of the patient more than any other diagnostic procedure, and knowing their needs is the only way to advocate for patients.

Even if the animal was seen recently, it is imperative that a thorough PE is performed the day of the surgery, ideally with the owner present. The goal of this chapter is not to detail every aspect of a PE, but rather to give an abbreviated overview. Many wonderful textbooks have complete chapters dedicated to performing PEs.

General Body Condition and Mentation

The patient’s general body condition (e.g., “strong and healthy” or “weak and emaciated”) and mentation (e.g., “bright, alert and responsive” [BAR] or “dull and depressed”) should be observed and noted during the history taking. The patient’s ability to see and hear is assessed during the history taking as well. If the patient is clearly distressed or aggressive, it is appropriate to request an assistant and to use a restraint device (e.g., muzzle) before the “hands-on” portion of the PE. If the patient is scared and timid, a slow, calm, and soft-spoken approach may sufficiently relax and calm the patient to allow for a thorough PE. Any gait abnormalities (lameness, ataxia), muscle atrophy, or asymmetry should be noted while observing the animal during the history taking and should be examined more closely during the hands-on examination.

The complete exam should include an evaluation of the temperature, pulse, and respiration (TPR).

Thoracic Auscultation

Thoracic auscultation requires using a stethoscope to listen to the chest for both heart and lung sounds (Figure 2-1). The heart and lungs are heard best with the animal standing still on all four legs. A talented veterinary technician will quickly learn how to keep a cooperative animal standing quietly while auscultating the thorax without an assistant (Figure 2-2). Occasionally it is necessary to prevent a dog from panting or a cat from purring. To stop a dog from panting, use the hand with the wristwatch to extend the neck by gently lifting up on the dog’s mandible using the top surface of the hand, while the other hand holds the stethoscope to the patient’s chest. Clamping the mouth shut to try to prevent a dog from panting (Figure 2-3) frequently results in excessive movement as the dog tries to wriggle out of the technician’s grip. Most dogs tolerate a gentle lift of the mandible with the top of the hand better and stand quietly long enough to count a heart rate. To stop a cat from purring, it may be necessary to restrain the cat firmly near a sink and turn on the water to a slow stream.

FIGURE 2-1 Typical stethoscope, with both diaphragm and bell in chest piece. Swiveling the chest piece determines whether the diaphragm or bell is used for auscultation. Note the curvature in the stems of the ear pieces. The stems should be placed in the examiner’s ear canals and pointing toward the nose.

FIGURE 2-2 If the patient is cooperative, one technician can easily restrain the patient in a standing position while auscultating the thorax.

FIGURE 2-3 Preventing a dog from panting by gently closing the mouth while auscultating the thorax helps the examiner hear heart sounds over breath sounds.

Begin auscultating the heart by placing the diaphragm of the stethoscope’s chest piece just caudal to the point where the dog’s left elbow meets the chest. For cats a more ventral placement of the chest piece may be necessary to hear the heart best. One heartbeat normally has two sounds; that is, the “lub-dub” is two sounds but one heartbeat. Once the distinctive lub-dub heart sounds have been identified, time 15 seconds on a watch and count the number of heart sounds heard. To determine the heart rate, multiply the number of beats heard in 15 seconds by 4; this number is the heart rate in beats per minute. Systolic murmurs are usually heard as a swishing sound between the lub-dub (“lub-shh-dub”). Moving the stethoscope one rib space cranially or caudally may amplify the sound of the murmur. The rib space where the murmur is heard the loudest is the point of maximum intensity (PMI). The rib space can be identified by counting backward from the last (13th) rib. Keep in mind that some murmurs are heard loudest on the right side of the chest. The presence of a murmur and the PMI of the murmur should be noted in the medical record.

The lungs should fill up the pleural space when fully expanded during maximum inhalation. Normal lung sounds should be distinct but soft and free of any wheezing, crackling, and popping sounds. Normal lung sounds should be heard equally well on the left and the right sides of the thorax. Be sure to listen to both sides (cranial and caudal, dorsal and ventral) for lung sounds. One breath is a two-part movement: inhalation and exhalation. To determine the respiratory rate (number of breaths per minute), count the number of breaths in 15 seconds and multiply that number by 4. Any increased effort by the animal to breathe (dyspnea) and any increase or absence of lung sounds must be noted in the medical record and addressed. Usually, addressing respiratory abnormalities includes giving the patient supplemental oxygen. The lungs should be assessed, not only for respiratory rate but also for crackles, wheezes, and any other abnormalities. Any abnormalities or noteworthy findings in the PE need to be recorded in the medical record and brought to the attention of the attending veterinarian.

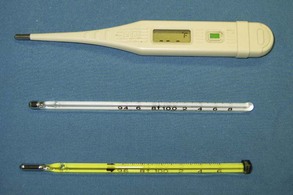

Taking the Temperature

Ideally the temperature is taken rectally with a well-lubricated thermometer. Some patients strongly resist this part of the PE, and therefore taking the temperature should be saved for the end of the examination so that the patient may be more cooperative for most of the PE. Some states no longer allow the sale or purchase of mercury thermometers, but it is still important that every veterinary technician can read a mercury thermometer (Figure 2-4). Most mercury thermometers require 90 to 120 seconds to record the patient’s temperature (check the manufacturer’s recommendation). Most digital thermometers emit a series of audible beeps within 60 seconds to indicate that the final temperature has been recorded.

FIGURE 2-4 Digital thermometer (top) and two mercury thermometers. Note the differing ranges between the lower and upper limits of the two mercury thermometers (94° F to 108° F and 96° F to 106° F).

If it is not possible to take the temperature rectally, an aural temperature measurement can be taken. There are several styles of ear thermometers on the market. Ear thermometers read the temperature of the tympanic membrane using infrared technology. The probe sits several millimeters off the ear drum as it records the temperature. This space and the shape of the animal’s ear canal can lead to inaccurate readings (Figure 2-5).

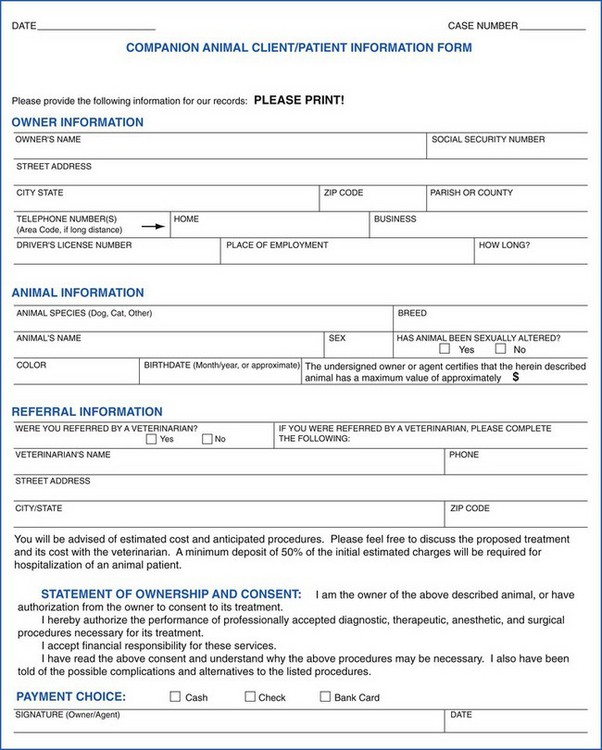

Consent Form

A consent form is a piece of paper that identifies the patient (name, signalment, and descriptors such as hair coat color and body weight), the specific procedure(s) to be performed along with the potential risks to the patient, the physician(s) who will perform the procedures, and the signature of the owner consenting to the procedure(s). Frequently, the receptionist merely hands the consent form to the owner to sign when the animal is brought to the hospital on the day of the scheduled procedure. Because the consent form contains such important information, however, the veterinary technician familiar with the surgical procedure should review the form in detail with the owner at completion of the PE. This gives the owner the opportunity to ask any last-minute questions about the procedure before the animal is admitted to the hospital. Open and clear communication is essential to avoid any confusion and to prevent miscommunication that could lead to legal complaints later. Many legal complaints originate with poor or rushed attempts at client communication.

Descriptions of the procedures should be written out and should be all inclusive; that is, everything that will be done to the animal needs to be listed. This form also should document whether or not the patient was fasted appropriately, should include a notation that the owner received an estimate for the procedure(s) to be performed, and should provide a way of contacting the owner during the time the procedure(s) will be performed. It is extremely important that the owner can be contacted during the procedure, should the need arise (Figure 2-6).

Preanesthetic Diagnostic Tests

With the ever-increasing standards of care in veterinary medicine and the owner’s expectations for the surgical patient’s optimum health care, the minimum preanesthetic diagnostic database, or minimum database (MDB), is continually rising in scope. Information collected in the history and PE will help determine which diagnostic tests should be performed before the patient is anesthetized. What is considered the MDB for an elective surgical procedure on a young, healthy animal will be different from the MDB for a procedure on a geriatric patient with preexisting health problems. The MDB results may suggest additional diagnostics may be indicated, or that the original anesthetic protocol may have to be amended.

Minimum Database

A minimum database for a young, healthy surgical candidate should include a packed cell volume, total solids, blood glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and alanine aminotransferase. These tests should be considered a starting point, and other diagnostic tests should be performed if any of these four basic parameters cause any concern. These tests are generally easy to run, can usually be performed as “point of care” or “in-house” tests, and require only a small amount of blood. With minimal time and effort, much useful information can be gained from these tests. Several laboratories and in-house analyzer companies sell packaged pre-anesthetic test panels, making the process even easier.

Packed Cell Volume (Hematocrit)

The packed cell volume (PCV), or hematocrit (Hct), is the percentage of whole blood that is made up of red blood cells (RBCs). Low PCVs are found in cases of decreased RBC production (as in chronic renal failure), decreased RBC life span (as with some autoimmune diseases and parasite infections), and blood loss (secondary to trauma, blood-clotting disorders, or gastric ulcers). Increased PCV may indicate dehydration (common) or absolute polycythemia (rare). Any values outside the normal ranges need to be brought to the attending clinician’s attention.

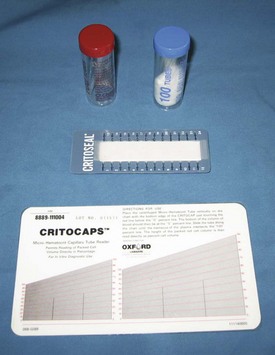

Checking a PCV requires microhematocrit tubes, a tube sealant (e.g., Critoseal), a centrifuge, and a hematocrit card reader (Figure 2-7). If whole blood is collected in a syringe without an anticoagulant, heparinized microhematocrit tubes should be used for this test. If blood is collected into a heparinized syringe or placed in a Vacutainer tube with anticoagulant (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA]) in it, a plain microhematocrit tube should be used. Glass microhematocrit tubes are generally easier to work with than the plastic variety.

FIGURE 2-7 Heparinized (red) and plain (blue) microhematocrit tubes (top), packed cell volume (PCV) card reader (bottom), and clay to seal blood in microhematocrit tube (middle).

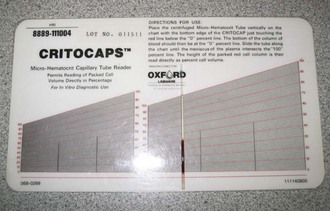

After spinning the microhematocrit tube for the appropriate time in the centrifuge (Figure 2-8), the tube is placed on the card reader. Line up the top of the clay with the “0%” line on the card reader. Roll the tube across the card until the top of the plasma lines up with the 100% line on the card. Read the percentage line that crosses the point where the packed RBCs are separated from the plasma, at the “buffy coat”; this percentage is the PCV (Figure 2-9). The buffy coat usually appears as a small column of white between the packed RBCs below it and the clear plasma above it. The buffy coat contains white blood cells (WBCs) and platelets. The area just above the buffy coat can be examined under a microscope to perform a heartworm screening for live microfilaria.

FIGURE 2-9 To read packed cell volume (PCV) on a card, line the top of the clay plug on the 0% line and the top of the plasma on the 100% line. PCV is read on the line where plasma and packed red blood cells meet. On this sample, PCV is approximately 40%.

Normal range of packed cell volume:

Plasma is the liquid (noncellular) component of blood that separates out from the packed RBCs after whole blood is placed in a microhematocrit tube, sealed with the clay, and spun in a centrifuge. Normally, plasma is clear and colorless. If the plasma has any color, the color should be noted next to where the PCV percentage is recorded in the medical record and brought to the attention of the veterinarian.

Total Solids or Proteins

Total solids (TS) or total proteins (TP) provide information on the animal’s plasma protein levels. There are three major plasma proteins: albumin, globulin, and fibrinogen. These levels have a direct effect on serum oncotic pressure. The lower the TP value, the lower the serum oncotic pressure. Changes in serum oncotic pressure directly affect changes in the patient’s fluid shifts between the interstitium and the vasculature. With a low serum oncotic pressure, fluid tends to accumulate in the interstitium, resulting in edema. On the other hand, with a high serum oncotic pressure, fluid shifts out of the interstitium and back into the vasculature (blood vessels).

Elevated plasma protein values are associated with dehydration, malignancies (e.g., lymphosarcoma), and infections. Decreased plasma protein values are associated with inadequate production (albumin is made in the liver), inadequate intake (starvation), increased loss (renal disease, blood loss, parasites), and inadequate absorption from the gastrointestinal tract (pancreatic disease, inflammatory bowel disease).

In addition, plasma protein levels are important because some anesthetics (some barbiturates) are highly bound to proteins. If a patient is hypoproteinemic, more free drug (not bound to plasma proteins) will be available to function as an anesthetic, effectively increasing the dose. Therefore the animal’s protein levels should be noted when deciding which anesthetics to use, or the anesthetic dose may need to be adjusted accordingly.

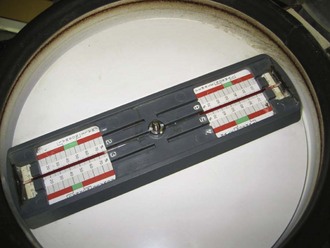

Supplies needed to check plasma proteins include a refractometer (Figure 2-10) and microhematocrit tubes. After the PCV level is checked, snap the glass microhematocrit tube in the area of the plasma column. Take care not to touch or scratch the glass platform of the refractometer with the sharp edges of the microhematocrit tube. Allow the plasma to drip onto the refractometer out of the microhematocrit tube. The TS level is read on the scale seen in the refractometer.

Blood Glucose

Blood glucose (BG) levels indicate carbohydrate metabolism and measure the endocrine function of the pancreas. Eating raises BG levels, and fasting lowers them. Stress will elevate BG levels in cats. In juvenile patients and diabetic patients, BG values may need to be checked intraoperatively and postoperatively if the procedure is especially long.

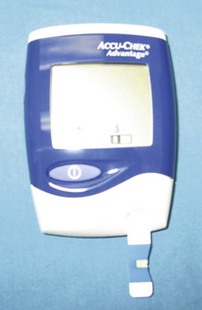

Glucometers are available at most pharmacies and are easy to use (Figure 2-11). Usually, only a drop of fresh whole blood is required. Some glucometers (e.g., Roche’s ACCUCHEK Advantage, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) can determine BG levels using blood collected in EDTA or heparin, two types of anticoagulants, but they will not accurately measure BG in serum. It is important to use recently collected blood because glucose values are affected by how long the blood sits before it is analyzed. Likewise, it is important to follow the manufacturer’s guidelines and directions. Any invalid results should be addressed (e.g., repeat with another sample) and any abnormal results should be brought to the attending veterinarian’s attention and addressed.

Blood Urea Nitrogen

Urea is a nitrogenous compound that is a product of amino acid breakdown in the liver. BUN levels are used to evaluate the kidney’s ability to remove nitrogenous wastes (urea) from the blood. If the kidneys are not working properly, an insufficient amount of urea is removed from the plasma, resulting in increased BUN levels.

An estimate of the patient’s BUN value can be assessed quickly using a reagent strip (e.g., Azostix, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Washington, DC; Figure 2-12). Blood mixed with the anticoagulants EDTA or heparin (as long as it does not contain an ammonium salt) will not affect the estimated BUN of an Azostix; however, neither serum nor plasma should be used for this test. Supplies needed to check BUN on a reagent strip include the reagent strip, fresh blood sample, watch with second hand, and a strong stream of water to rinse the strip. The color change on the reagent strip is compared with the color scale on the bottle for the strips. The corresponding color match between the reagent strip and the bottle indicates the estimated BUN (Figure 2-13).

FIGURE 2-12 Bottle of reagent strips (Azostix, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Washington, DC) used to estimate blood urea nitrogen (BUN); color scale is used to estimate BUN value.

Some anesthetics are primarily metabolized by the kidneys, and if there is any question of the patient’s renal function, choosing a drug that is not primarily metabolized by the kidneys ought to be considered. Further diagnostic tests assessing kidney function (e.g., urinalysis) should be considered as well.

Alanine Aminotransferase

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is an enzyme found in high concentration in the liver cells of dogs, cats, and primates. Damage to hepatocytes can elevate blood ALT levels. Certain drugs, such as anticonvulsants and corticosteroids, can also raise blood levels. ALT, while not indicative of specific liver disease, can be used as a general hepatic screen.

Additional Tests

Other diagnostic tests specific to the patient’s history and PE findings should be performed before any surgery. Generally, preanesthetic diagnostics are noninvasive and may eliminate (“rule out”) the need for more invasive procedures. However, these diagnostic tests may support the need for additional, more invasive diagnostics or procedures. For example, the logical progression of diagnostic testing for a puppy with vomiting and diarrhea would start with an intestinal parasite test (“fecal”) and a parvovirus (“parvo”) test, followed by abdominal radiographs, then an abdominal ultrasound, and finally an abdominal exploratory procedure. In addition, the puppy with vomiting and diarrhea should receive a complete blood count (CBC) and serum chemistry panel and electrolyte panel to aid in determining what type of intravenous fluids or additional support (e.g., antibiotics, parenteral nutrition, plasma transfusion) is indicated.

It is important to note that preanesthetic diagnostic tests will not be the same for every patient and that not all preanesthetic diagnostics are limited to blood tests (e.g., CBC; serum chemistry, electrolyte, thyroid, and clotting panels; heartworm and feline leukemia virus tests; blood cultures). For example, intestinal parasite tests, radiographs, diagnostic ultrasounds, urinalyses, and electrocardiograms may need to be performed before surgery on certain patients, depending on the history and PE findings.

Preoperative Medications

Once all the preanesthetic diagnostic tests have been performed and analyzed, if the results still indicate that surgery is necessary and is the appropriate next step, the patient is premedicated for anesthesia.

Surgical patients are routinely premedicated with a combination of agents, including analgesics, sedatives, and at times anticholinergics. The purpose of administering these agents before induction is threefold. First, the patient is more relaxed, allowing a less stressful transition to anesthesia. Second, pain management is provided at the optimum time, before surgical tissue trauma occurs. Third, appropriate premedications (“premeds”) ease the transition out of anesthesia, facilitating a smooth recovery. Anticholinergics may be added to prevent some of the undesired effects of the analgesia and sedation, mainly bradycardia.

Balanced Anesthesia

Premedication is an important part of balanced anesthesia. The objective of balanced anesthesia is to combine several agents, in smaller dosages, to maximize the positive effects, such as analgesia and muscle relaxation, while minimizing the negative effects, like cardiac and respiratory depression. The goal is to calm the patient, minimize pain, and reduce the adverse effects of the agents used (Box 2-1).

Principles of Pain Management

The basic principles of current pain management involve (1) preemptive (preventive) analgesia, (2) multimodal analgesia (using different classes of drugs simultaneously to interrupt the pain pathway at various points), and (3) appropriate follow-up analgesia. Using this strategy, veterinarians design an analgesic plan for each patient that maximizes pain control, keeps patients on an analgesic plane, and reduces unwanted side effects.

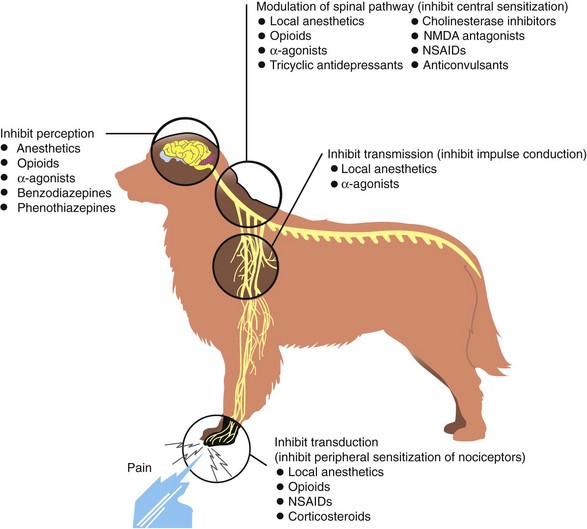

These simple principles have evolved from our current understanding of the pain pathway, or nociception. Pain signaling occurs in a distinct pathway that begins at the onset of a noxious stimulus. The stimulus may be tissue trauma, surgical incision, or even heat. When tissue is traumatized, the first phase of the nociceptive pathway is triggered, and the event is converted to a signal that can be sent to the central nervous system (CNS) for processing. This phase is called transduction. The second phase, transmission, is the propagation of the impulses up toward the spinal cord. Once in the spinal cord, pain signals may undergo a number of different effects. Some signals are handled locally by the release of endogenous opioids, whereas others are sent to the brain for further processing. This sorting process is called modulation, the third phase; pain signals are said to be “modulated” in the spinal cord. The fourth and final phase of nociception, perception, occurs only in the conscious patient. Perception is “knowing” that pain is present and usually results in such reactions as withdrawal, vocalization, and, in some cases, aggression. Anesthesia interrupts the perception phase only. It is important to remember that interfering with perception alone does not address transduction, transmission, or modulation. Patients who undergo surgery only with anesthesia have essentially no pain management; the spinal cord is continually bombarded by pain signals, which will become evident as soon as the animal wakes.

The four distinct phases of the pain pathway allow pain to be interrupted at more than one juncture. Pain management specialists believe that interrupting nociception or pain perception can be achieved most effectively by targeting multiple points along the pathway. The analgesic drugs currently available target one or more of the nociceptive phases, although each class of agents exerts a major effect on one of the four phases (Figure 2-14). This is the rationale for combining different analgesics as premedications for surgery, a process called multimodal analgesia.

Analgesics

Optimum premedication for surgery is likely to include several agents, as just discussed. Four classes of drugs can be effectively used to deliver preemptive analgesia: opioids (e.g., butorphanol, buprenorphine, morphine, fentanyl), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; e.g., carprofen, meloxicam, deracoxib), local anesthetic agents (e.g., bupivacaine, lidocaine), and α2-adrenergic agonists (e.g., medetomidine, xylazine). (The appendix provides complete dosage information.) The most effective time to administer analgesia is before tissue trauma or damage occurs. Preemptive analgesia, the anticipation of pain and its treatment in advance, is a critical pain management strategy. Most patients require less anesthesia and actually experience less pain on recovery with smaller doses of analgesics when effective preemptive analgesia is administered.

Table 2-1 summarizes the side effects of analgesics. Note that not all the agents described in this table are approved for use in veterinary patients. Some are approved for use in dogs but not cats, and some are approved for use as single agents rather than in combination with other drugs. However, although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved all the previously cited analgesics for use in veterinary medicine, the Animal Medical Drug Use Clarification Act of 1994 (AMDUCA) permits veterinarians to use them on an “extra-label” basis.

TABLE 2-1

| Agent | Adverse Effects | Monitoring |

| Opioids | Sedation, low blood pressure, respiratory depression | Mentation, blood pressure, respiratory rate and quality |

| Local anesthetics | None unless given by CRI With CRI: nausea, vomiting, neurologic signs, seizures |

Observe regularly for muscle tremors and GI upset |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | GI disturbances, GI bleeding, renal disturbances | General observation, hydration status, stool quality, urine production |

| α2–agonists | Bradycardia, cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, peripheral vasoconstriction | Palpate femoral pulse rate and quality; auscultate heart; monitor blood pressure. |

Opioids

Opioids, the mainstay of acute pain management, provide analgesia by binding to specific opioid receptors in both the CNS and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Opioids work at several locations along the pain pathway, affecting nociceptive signal transduction, modulating signals at the spinal level, and inhibiting perception of pain. In addition to providing analgesia, opioids help reduce anxiety and nonpainful distress.

Almost every patient expected to experience pain is a candidate for opioid analgesia. As a class, opioids produce minimal side effects in animals. The only cases in which opioids may be contraindicated are patients with head trauma, because even mild respiratory depression associated with opioids may worsen potential intracranial pressure. Opioids are most effective when administered before the onset of pain. Opioids can be administered through the conventional intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), and oral (PO) routes. Other, less common but effective routes of administration are transdermal (e.g., fentanyl), epidural, and intra-articular, as well as by constant-rate infusion. Buccal administration has become a popular route for buprenorphine in the cat, whose unique oral pH allows for excellent absorption by this route. (See the Appendix for an in-depth description of these techniques).

How opioids work: Opioids bind to opioid receptors in the spinal cord. The mu (µ) and kappa (κ) opioid receptors are primarily responsible for producing analgesia, with the µ receptor producing the most profound analgesia. The κ receptors produce much milder analgesia. Both receptor types are also responsible for producing respiratory depression, euphoria, sedation, and miosis. An opioid can interact with one or more types of opioid receptor. Drugs that bind to a receptor and cause expression of activity are called agonists. Drugs that bind to receptors and block their action are called antagonists. There are further subclassifications into full (pure) agonists, partial agonists, and mixed agonist-antagonists. The opioid drugs are classified by these subdivisions, which describe their potential action and duration.

Pure agonists (e.g., morphine, hydromorphone) bind and stimulate all types of opioid receptors, causing maximum analgesia. They are extremely effective but of only moderate duration, typically about 4 hours. Full agonists are also the most likely to have side effects.

Partial agonists function much the same as full agonists, but the interaction occurs with less than full activity at the receptors. Buprenorphine is a µ partial agonist. Although buprenorphine only partially binds to the µ receptor, it does so with great affinity. Therefore, although it provides analgesia of less intensity than morphine, buprenorphine has a much longer duration of action, up to 8 to 12 hours.

Agonist-antagonist opioids (e.g., butorphanol) bind to more than one type of opioid receptor, having an effect at one type but blocking effects at another receptor. Butorphanol binds and activates κ receptors to produce analgesia and sedation; it also binds with µ opioid receptors, blocking (antagonizing) the receptors. For this reason, butorphanol is considered a mild analgesic with extremely short duration, less than 1 hour in most cases. Butorphanol does produce profound sedation for up to 2 hours, outlasting the analgesia provided. Co-administration with butorphanol may result in reversal of the µ effects of full opioid agonists.

Antagonist opioids fully or partially reverse the effects of opioid agonists. Naloxone is a pure opioid antagonist that completely reverses the effects of all opioid agonists at all receptor sites. Butorphanol can be used as a partial reversing agent, reversing µ activity but not κ effects.

Side effects: Opioids have few clinically significant cardiovascular effects, other than bradycardia, in dogs and cats when administered at recommended doses. However, opioid-induced bradycardia is responsive to anticholinergics and can be reduced if a patient is pretreated with an anticholinergic. Respiratory depression is a common side effect with opioids in humans but rarely is clinically significant in veterinary patients. Emesis (vomiting) is a common side effect of some opioids, particularly morphine and hydromorphone. Vomiting typically occurs once when opioids are used as a premedication rather than when administered to an animal already in pain. Panting is a fairly common side effect of many opioids, especially at higher doses. This potential side effect may not be clinically important, but it can make patient monitoring difficult postoperatively because it is difficult to differentiate between panting as a sign of pain and panting as a reaction to an opioid.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs have been used in human and veterinary medicine for many decades to treat fever, inflammation, and pain. More recently, NSAIDs have been shown to be quite efficacious for treating inflammation and pain associated with surgery, and several NSAIDs have been approved for preoperative use in dogs. NSAIDs can be incorporated into premedication protocols to control mild to moderate pain associated with surgery. For maximum effect, NSAIDs should be administered preoperatively, up to 1 to 2 hours before tissue trauma. When they are used in this way, controlling inflammation before it begins, dramatic results can be observed in the postoperative period. Patients who receive preemptive NSAIDs tend to recover with significantly less pain and often require less postoperative analgesia than those who do not. This class of drugs can be safely combined with opioids to provide excellent multimodal analgesia. NSAIDs are available in several formulations, including oral tablets, chewable forms, liquids, and injectable solutions.

How Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Work

When cells are damaged as a result of trauma, surgery, or disease, fatty acids such as arachidonic acid (AA) are released from cell membranes. The release of AA triggers a cascade of biochemical activities that ultimately produce prostaglandins, which serve many functions in the body; some prostaglandins are essential for normal homeostasis, and some result in inflammation and pain. The enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX) metabolizes AA to prostaglandin and is the target of NSAIDs. To date, two forms of COX enzymes have been identified. These enzymes are closely related and are now known as COX-1 and COX-2. Each converts AA to prostaglandins, although the prostaglandins produced by each COX enzyme appear to serve very different functions. COX-1 is continuously present in most cells and is important for normal body functions. In the stomach, COX-1 plays a key role in maintaining integrity of gastric mucosa. In platelets, COX-1 is essential for thromboxane A2 production. In contrast, COX-2 is not readily present in the cells, but it is rapidly synthesized in response to various inflammatory stimuli. Once induced by tissue injury, COX-2 converts AA into prostaglandins that create inflammation and pain. Both COX-1 and COX-2 play a vital role in the kidney as important mediators of salt and water balance, rennin (chymosin) release, and vascular tone. NSAIDs exert their anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting activity of COX-1, COX-2, or both. This inhibitory activity varies between NSAID compounds and with animal species.

Side effects: As a class, NSAIDs are associated with specific types of potential side effects. Some of these are species specific and drug specific, as in the case of acetaminophen metabolism in cats. Possible side effects associated with NSAIDs include gastrointestinal tract damage, hepatopathy, renal toxicity, impaired platelet function, and cartilage destruction. Administration of NSAIDs should be restricted to well-hydrated, normotensive animals with normal hepatic and renal function, no hemostatic abnormalities, and no evidence of gastric ulceration.

Alpha2-Adrenergic Agonists

Alpha2-adrenergic agonists (α2-agonists) are short-duration sedative-analgesic–muscle relaxants that can be rapidly reversed with α2-antagonists. This characteristic makes these drugs suitable for procedures requiring short-term restraint and analgesia as well as premedication for longer surgical procedures. Use of α2-antagonists as premedications may result in substantial reduction in both induction and inhalant anesthetic dosages. α2-agonists are nonnarcotic and nonscheduled agents. Medetomidine and xylazine are the two α2-agonists currently approved for use in dogs in the United States. Medetomidine is a dose-dependent sedative-analgesic often used as a preanesthetic agent in healthy animals. Onset of effect is 5 to 15 minutes depending on route of administration, which can be IV or IM, and sedation can last up to 90 minutes.

How α2-agonists work: α2-agonists inhibit release of the excitatory neurotransmitter norepinephrine to produce analgesia and sedation. These agents interrupt the pain pathway by inhibiting nerve impulse transmission, modulating nociceptive signals in the spinal cord, and inhibiting perception within the brain. Because α2-adrenoceptors are found in various sites throughout the body, α2-agonists normally induce a number of physiologic changes in addition to sedation, analgesia, and muscle relaxation. Administration results in physiologically normal peripheral vasoconstriction, which creates a transient increase in blood pressure. Because the normal cardiovascular response to these events is a reflexive decrease in heart rate, patients are expected to become bradycardic. All cardiovascular parameters smoothly return to presedation levels on reversal of the agent with atipamezole.

Side effects: α2-agonists can have profound effects on the CNS and cardiovascular system, but using low dosages can minimize these adverse events. Bradycardia and vomiting are the most common side effects. All α2-agonists have potential side effects, including hypertension, bradycardia and heart block, respiratory depression, excessive CNS depression, vomiting, increased urine production, and peripheral vasoconstriction.

Candidates for α2-agonist administration should be healthy, have sound cardiovascular systems, and be exercise tolerant. An α2-agonist should never be administered to an animal with a compromised cardiovascular or respiratory system.

Local Anesthetics

Local anesthetics are inexpensive to use and quite effective in blocking the transmission of nociceptive signals at the source. Use of local anesthetics offers three major benefits. First, these agents produce true analgesia, that is, a complete absence of pain. Second, they are nonscheduled agents, requiring no cumbersome paperwork. Third, the techniques used to administer local anesthetics are relatively easy to perform. Most blocking techniques are well within the skill level of licensed veterinary technicians. Local anesthetics can and should be used in any surgical patient with an identifiable site for nerve blockade. For example, local anesthetics can be used effectively in patients undergoing thoracotomy, elbow surgery, maxillomandibular procedures, local excisions, feline declawing, and knee or cruciate repair. Anesthetic agents can be administered to create local and regional anesthesia and analgesia (Box 2-2).

In addition, local anesthetics are most often the drugs of choice for epidural anesthesia and analgesia. This technique is a good alternative to general anesthesia or as an adjunct to inhalant anesthesia, especially for patients at high risk during general anesthesia and those undergoing painful orthopedic surgeries of the hind limb. Finally, an IV constant-rate infusion of a local anesthetic can provide sustained pain control in a variety of patients undergoing extensive nerve trauma, such as limb amputation. Lidocaine and bupivacaine are the agents most often used for dogs and cats. Lidocaine is characterized by rapid onset (5-10 minutes) but short duration (45-90 minutes). In contrast, bupivacaine has a longer onset (15-20 minutes) but provides up to 6 hours of analgesia (Table 2-2).

TABLE 2-2

Comparison of Local Anesthetic Agents

| Drug | Onset | Duration |

| Lidocaine | 5-10 minutes | 45-90 minutes |

| Bupivacaine | 15-20 minutes | Up to 6 hours |

How local anesthetics work: Local anesthetics act by inhibiting transduction and transmission of nerve impulses and by modifying the signals at the spinal cord. Local anesthetics inhibit generation and transmission of nerve impulses by blocking sodium channels in the neuron’s cell membrane. This effect slows the rate of depolarization of the neuron cell membrane and prevents the threshold potential from being reached.

Side effects: When administered at an appropriate dose, local anesthetics have relatively few, if any, adverse side effects. The potential systemic side effects of local anesthetics involve the CNS and cardiovascular system. Other potential side effects include development of methemoglobinemia, nerve and skeletal muscle toxicities, and allergic reactions, including hypersensitivity and anaphylaxis.

Sedation and Tranquilization

Sedatives alone do not possess any analgesic properties but are an important adjunct to premedication protocols. Sedation should be incorporated into preoperative regimens to reduce stress, fear, and anxiety, all of which exacerbate pain, and vice versa. However, sedatives alone (with the exception of α2-agonists) should never be administered to an animal without analgesia when pain is anticipated. Sedation alone may decrease the animal’s ability to express pain and give the false impression that the animal is pain free. The most frequently used sedatives for premedication include the tranquilizing agents phenothiazines (acepromazine) and benzodiazepines (diazepam, midazolam).

Anticholinergics

Anticholinergic drugs such as atropine and glycopyrrolate are sometimes added to premedication protocols that are expected to produce profound, sustained bradycardia. For example, anticholinergics are frequently given to patients who receive opioids and are expected to have a long gas inhalation anesthesia time. Anticholinergics are given to reduce bradycardia and to dry oral secretions. Atropine sulfate has a quick onset of action and rapid elimination and can be given subcutaneously (SC), IM, or IV to prevent or to treat bradycardia and to dry oral secretions. Glycopyrrolate can be given SC, IV, or IM, although onset of action is substantially increased when given IV. Glycopyrrolate is typically used to prevent bradycardia rather than treat it once it has occurred. The effects of glycopyrrolate are much longer lasting than those of atropine.

Anticholinergics can increase the incidence of cardiac arrhythmias and sinus tachycardia. Increasing heart rate is not always beneficial to the patient because higher heart rates do not necessarily translate into better perfusion. Whether or not an anticholinergic should be routinely administered in conjunction with drugs that lower heart rate (e.g., α2-agonists) has been the subject of considerable scientific debate. Initially, treatment of α2-agonist–induced bradycardia was thought to be beneficial. Currently, however, anticholinergic drugs are not generally recommended to prevent periods of expected transient bradycardia. Bradycardia that is considered life threatening because it is associated with poor perfusion can be rapidly corrected with atropine. The most practical approach may be to avoid “routine” use of anticholinergics, administering them on a case-by-case basis only to patients in need.

Antibiotics

An important consideration is whether or not the surgery patient needs intraoperative antibiotics and, if antibiotics are indicated, which type is appropriate. If the procedure is elective and a possible break in sterility during it is not a concern, antibiotics are generally unnecessary. However, if the surgical procedure is done specifically to treat contaminated or infected wounds, or if possible contamination during an elective procedure is a concern, intraoperative antibiotics may be indicated. Specific guidelines for prophylactic antibiotic use follow this section on wounds.

When determining whether antibiotics are indicated, it is helpful to know what type of wound is present. See Chapter 8 for a discussion on wound classifications.

Prophylaxis refers to the measures taken in the prevention of disease. The administration of antibiotics just before and during surgery is known as perioperative prophylaxis. The purpose of this practice is to decrease the chances of postoperative infection of the surgical site. Few surgical cases or circumstances warrant prophylactic antibiotic treatment; one example is an orthopedic procedure involving the placement of implants.

The choice of antibiotic depends on the type of bacterial contamination expected. For example, staphylococci from the skin are of concern in orthopedic procedures. Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli) are of concern in large-bowel procedures. The antibiotic’s spectrum of activity should be narrow and limited to the predicted bacterial contaminant.

The antibiotic must be administered by IV injection just before induction. The dose may be repeated during the surgical procedure to ensure adequate serum levels throughout the surgery. The antibiotic administration is usually not continued after the procedure is completed. Antibiotics that cannot be administered IV are not used as prophylactic antibiotics.

If an animal is taken to surgery with an infection that is already established, the clinician may have prescribed antibiotics for a period before the surgery. This situation is not considered “prophylactic” in nature. The antibiotics have been prescribed in response to an already established infection. In this case, it is important to continue the administration perioperatively and postoperatively, during the recuperative period. The antibiotic may need to be administered by injection (SC, IM, or IV) immediately before the surgery. Oral antibiotic administration can be reinstituted as soon as the animal can tolerate (“keep down”) food and water after the surgery.

Intravenous Catheters

After the patient has received the appropriate premedication, an IV catheter should be placed. In addition to the analgesic benefits provided by premedicating the surgical patient, premedication makes for a more sedate and cooperative patient when the catheter is placed.

The placement of an IV catheter offers many benefits to the surgical patient. Once an IV catheter has been placed, it is easier for the veterinary technician to administer, as well as less stressful for the patient to receive, multiple IV medications. Puncturing through the skin and vein (venipuncture) for every injection is unnecessary when an IV catheter is in place. Also, the patient with an IV catheter is not poked with a needle every time an IV medication is administered. Likewise, the veterinary technician does not need to find a “good” vein for every drug administered intravenously. Many drugs needed by a surgical patient are intended to be, and some can only be, administered intravenously, and the IV catheter allows for easier administration of these drugs. For example, induction agents for general anesthesia, analgesics, antibiotics, and fluids may need to be given to the surgical patient at some point during its hospital stay. Having established access to the vascular system through an IV catheter aids in the efficiency of administering these medications. From a safety standpoint, having venous access allows for immediate administration of emergency drugs if necessary.

The type and placement site of the catheter greatly influence its capabilities. Peripheral catheters are completely adequate for short-term use (1-3 days), anesthesia induction, and medication administration. However, for long-term use (>3 days), extended fluid therapy, or systemic monitoring, a jugular catheter (central line) should be placed.

Peripheral Catheters

Peripheral catheters are most often placed in the following sites:

Almost any palpable vessel can be used to place a catheter.

Supplies

Regardless of the site, the basic supplies needed to place the catheter remain the same (Figure 2-15).

FIGURE 2-15 Supplies required for placement of IV catheter and administration of IV fluids. From left: IV fluid bag (1-L bag of lactated Ringer’s solution shown), cotton balls and scrub product, IV fluid administration set, IV catheters, gauze squares, tape, and clippers.

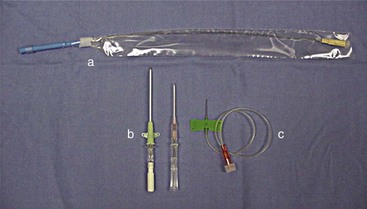

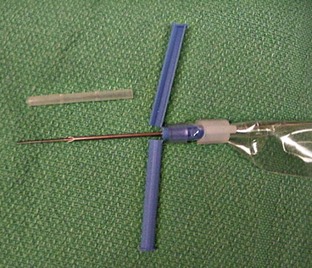

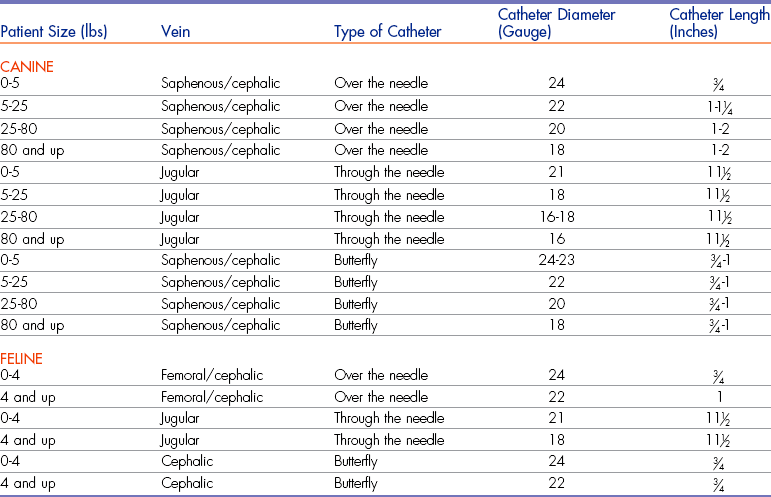

Catheter: Many styles of catheters are available for use. The three most common styles are the over-the-needle catheter, the through-the-needle catheter, and the butterfly catheter (Figure 2-16). The choice of catheter style is primarily determined by the site of placement and the intended use. The over-the-needle type is typically used for short-term and surgical catheters and is usually placed in a peripheral vein (e.g., cephalic vein). The butterfly catheter is useful when vascular access is required for medications that need to be administered once (as in outpatient treatments) and slowly (i.e., over 1-3 minutes). Butterfly catheters are sharp and rigid and are not intended to remain in a patient that is not being directly monitored (i.e., with hands-on monitoring). Through-the-needle catheters are often placed in the jugular veins of animals that will need intensive nursing care postoperatively (Figure 2-17).

FIGURE 2-16 Examples of IV catheters (a) through-the-needle catheter; (b) over-the-needle catheters; (c) butterfly catheter.

The choice of catheter size is primarily influenced by five factors: (1) site of placement, (2) length of time the catheter will be needed, (3) reason for placement, (4) diameter of the vessel, and (5) length of the vessel working area. Catheter diameter (gauge) should be chosen after evaluation of the vessel’s size and the reason for placement. The length of the catheter needs to be considered after the vessel has been chosen so that the length of the working area is known. For example, a 2-inch catheter placed in the cephalic vein of a dachshund is inappropriate, because once completely seated, the catheter would be proximal to the patient’s elbow and would be more likely to kink every time the leg was bent. Table 2-3 provides guidance in making appropriate catheter selections based on the factors listed.

Injection caps, T-ports, and fluid administration sets: Injection caps may be placed on the catheter if occasional injections or blood sample collections are anticipated (Figure 2-18). An injection cap allows for repeated punctures through the cap without resulting in damage to or leaking from the cap. Needle-less styles of injection caps are available and are a good option because they reduce accidental needle punctures of workers.

T-ports (or T-sets) serve the same purpose as an injection cap and also allow easier access to the catheter (see Figure 2-18). The short tubing incorporated into the design of the device allows sample collection or medication administration to be done more easily. A fluid administration set of the appropriate size should be used if continuous infusion of fluids or IV medications is anticipated, and the set can be connected to the T-port.

Usually an administration set supplying 15 or 20 drops/ mL (macrodrip set) is used for patients weighing more than 7 kg. Sets supplying 60 drops/mL (microdrip set) are used for patients weighing less than 7 kg for more accurate fluid administration. For extremely small patients, a Buretrol solution administration set (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) can be employed for the most accurate measurement of fluids administered, and it is especially useful if an electric fluid infusion pump is not available (Figure 2-19).

Extension sets: An extension set may be used in conjunction with an administration set to allow for better animal mobility in the cage postoperatively. The administration sets are often not long enough to be practical, so extension sets may be used.

Tape: The tape is one of the most important components of the catheter. Without proper anchoring, even the best placed catheter is useless. The technique for taping can vary from technician to technician, the only constant being that the catheter must be secure without being too tight. A loose tape job would allow the catheter to lose patency, but applying the tape too tightly could occlude blood flow. Typically, 1-inch and  -inch tape are used in varying orders to secure the catheter. If

-inch tape are used in varying orders to secure the catheter. If  -inch tape is not available, the 1-inch tape can be ripped in half. The first piece of tape should be long enough to encircle the patient’s limb or neck, depending on where the catheter is placed. Two additional pieces of tape, the same length as the first, will be needed to secure the catheter further in place.

-inch tape is not available, the 1-inch tape can be ripped in half. The first piece of tape should be long enough to encircle the patient’s limb or neck, depending on where the catheter is placed. Two additional pieces of tape, the same length as the first, will be needed to secure the catheter further in place.

Catheter “Prep” materials: Clippers with a number 40 (No. 40) blade are required for hair removal from the catheter site (Figure 2-20). The amount of hair to remove depends on the catheter site and the patient’s size. In general, for peripheral veins, a margin of  to 2 inches on all sides of the proposed puncture site is appropriate (clipping an area of this size often requires clipping the entire circumference of the limb). For catheters placed in the jugular vein, a larger area should be clipped.

to 2 inches on all sides of the proposed puncture site is appropriate (clipping an area of this size often requires clipping the entire circumference of the limb). For catheters placed in the jugular vein, a larger area should be clipped.

FIGURE 2-20 Two types of clipper blades, a No. 50 (left) and a No. 40 (right), that can be used to clip hair in preparation for surgery or placement of an IV catheter.

Preparation materials include cotton balls saturated with either dilute (50 : 50) povidone-iodine scrub or chlorhexidine scrub for the cleansing step and cotton balls saturated with 70% isopropyl alcohol for the rinsing step. Jugular catheter sites may be prepared with saturated gauze sponges instead of cotton balls.

Fluids or heparinized saline: Either continuous infusion of IV fluids or regular flushing of the catheter with heparinized saline is necessary to maintain patency of the catheter once it is placed. If fluids are used, 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl) or lactated Ringer’s solution (LRS) is most often used (Box 2-3).

Bandage materials: Bandage materials are needed if the catheter is to remain in place after the surgical procedure is completed. Antibiotic ointment, elastic gauze, and elastic tape (or Vetrap, 3M, St Paul, MN) are the materials of choice. (It should be noted that the benefits of using antibiotic ointment are anecdotal. Research in human medicine has shown that the use of such ointments at the catheter insertion point has actually led to antibiotic resistance and fungal growth.) Usually, 1-inch widths of all materials work best, given the area that will be bandaged on most dogs and cats, but personal preference eventually becomes the determining factor. Tegaderm (3M) is a sterile, transparent, breathable adherent dressing used to cover the insertion site of the catheter. This dressing is impervious to liquids and bacteria and therefore is effective in maintaining a catheter. Other sterile wound dressings may be used, depending on the indication for and placement site of the catheter.

Even with aseptic placement and appropriate bandaging, peripheral catheters should remain in place for only 3 days. Daily evaluation of the catheter and insertion site helps prevent phlebitis and detects any problems early. It is helpful to write the date, time, and initials of the technician placing the catheter on the outer bandage as well as on the inner tape. This information ensures that the catheter is replaced in the appropriate time frame.

Jugular Catheters

Some surgical patients require intense postoperative critical care. If part of this care requires central venous pressure (CVP) measurements or long-term fluid therapy, a jugular catheter (central line) should be placed.

Supplies

The supplies required for placement of a jugular catheter are similar to those used for a peripheral vein catheter. Jugular catheters are longer, usually 8 to 12 inches, and can be single lumen or double lumen. The extra length is needed to ensure placement of the catheter close to the right atrium of the heart, which is required to measure CVP. Because they are long-term catheters, jugular catheters should always be secured with a sterile bandage in addition to the tape. Antimicrobial ointment, elastic gauze, and elastic tape can be used for the bandage.

Placement

With the animal in lateral recumbency, a large area is clipped over the ventrolateral neck to reveal the jugular vein. The site is aseptically prepared as done for a peripheral catheter. Because these catheters are generally left in place for a longer time, a final “paint” is applied after the last rinse. The person placing the catheter should wear sterile gloves, and a sterile drape should cover the prepared area. Different catheters need to be inserted with different techniques, so it is best to consult and follow the manufacturer’s recommendation for the catheter used.

After the catheter has been placed and is secured, it is essential to maintain the patency of the line. The administration of fluids will aid in ensuring line patency. If fluids are not being administered, heparinized saline should be used to flush the line at regular intervals (e.g., every 6 hours).

Sample Collection

Sample collection from the catheter is easily accomplished and much less stressful on the patient than performing a venipuncture each time a sample is needed. The clinician must keep in mind that residues from medications administered through the catheter could interfere with test results. A three-syringe technique can be used to help decrease the incidence of contaminants in a blood sample collected from an IV catheter. A three-mL syringe is half-filled with heparinized saline, and blood is withdrawn into the syringe from the catheter. This helps clean any contaminants from the catheter. The second syringe is used to withdraw the appropriate sample and place it in the desired collection tubes. Lastly, the original syringe is used to replace the withdrawn blood and flush the catheter with the remaining heparinized saline.

Central Venous Pressure

CVP monitoring is done to assess how well blood is returning to the heart as well as how effectively blood is pumped from the heart. This procedure is helpful in monitoring a patient with right-sided heart failure because blood backs up into the vena cava in such a patient. CVP monitoring also helps to assess overhydration with fluids because as blood volume increases, CVP rises. A water manometer is connected to the catheter to determine the measurement. A normal reading for cats and dogs is less than 8 cm H2O.

Endotracheal Intubation

Endotracheal (ET) tubes are an important piece of anesthetic equipment. They are used for two main reasons: administration of oxygen and inhalation anesthetics and assistance with resuscitative needs.

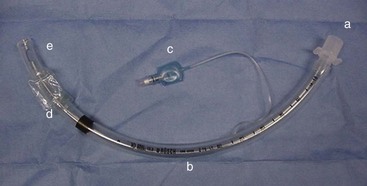

Components of Tube

All ET tubes have several components (Figure 2-33). It is important to know each of these components in order to use the tubes properly and evaluate the integrity of each tube before use.

FIGURE 2-33 Endotracheal tube; a, hose connector; b, body; c, cuff indicator; d, cuff; e, Murphy eye.

• The hose connector is found at one end of the ET tube. It connects the tube to the Y-piece, non-rebreathing system, or Ambu bag.

• The body is the major portion of the ET tube. Several numbers may be found on the tube body. The length measurements are in 2-mm increments and identify the length of the tube. The manufacturer’s name may also be seen on the body. The large bold number is the size of the internal diameter in millimeters. The most common tubes are available in sizes ranging from 3.0 to 12.0 mm in 0.5-mm increments.

• The cuff indicator is used to determine the pressure of the cuff on the trachea once air has been infused into the cuff.

• The cuff is present to permit the creation of a leakproof system. Air is infused into the cuff, via the cuff indicator, to ensure a seal between the ET tube and the lumen of the trachea. The cuff prevents the patient from inhaling room air, which would dilute the gas delivered to the patient during anesthesia. The cuff also prevents the patient from exhaling anesthetic gas into the operating room and from aspirating any vomitus while intubated.

• The Murphy eye is found at the tip of the ET tube. It allows airflow in the event that the end of the tube becomes occluded with respiratory secretions (mucous plugs).

Box 2-5 explains how to check an ET tube for leaks before using it in a patient.

Selection of Proper Tube Size

The largest size ET tube possible, without being traumatic, should be used. Generally, tube size is based on a patient’s weight, although palpation of the trachea and experience will aid in this decision. Table 2-4 is provided as a reference. Because of the variability in patient size, multiple tubes should be set aside for possible use and checked for leaks with every patient. An acceptable practice is to choose the size thought to be needed, in addition to a tube 0.5 mm smaller and a tube 0.5 mm larger.

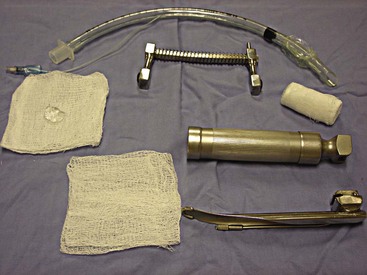

Supplies

Using the proper supplies in the proper manner will significantly increase the success rate of intubation (Figure 2-34).

Endotracheal Tube

Both clear and colored ET tubes are available. Although the two types work equally well, the clear tubes have two distinct advantages. First, any type of occlusion in the tube (e.g., blood, mucus) is more easily identified in a clear tube than in a colored or nonclear tube. Second, clear tubes allow visualization of the fog that moves along the lumen of the ET tube as the patient breathes. This is another useful means of quickly confirming that the patient is breathing.

Securing the Tube

A method of securing the tube in place is necessary. Rolled gauze is most commonly used to secure the ET tube to the patient once proper placement has been established. Any width can be used, although 2-inch gauze is most often employed. The gauze should be a nonstretch type, like muzzle gauze. Kling gauze can stretch, leading to tube slippage. The gauze is placed on the tube to indicate the depth of placement of the ET tube in the patient. Another method of securing the tube is using pieces of IV lines or plastic ties. The plastic can be cleaned and used with many different patients; it can also be less “messy” for performing dental procedures. The plastic or tubing is placed in a similar fashion to the gauze. Proper depth of insertion is determined by measuring the tube before placement. Box 2-6 describes the procedure for measuring the tube for proper placement in the patient.

Sterile Lubricant

Sterile lubricant is needed to lubricate the tip and cuff of the ET tube to permit easier passage of the tube through the larynx. The lubricant should be placed on a clean gauze sponge or clean paper towel and then applied to the tube. Water can also be used to lubricate the tube.

Cuff Syringe

The cuff syringe, or “puffer cuffer,” is needed to inflate the cuff of the ET tube. Generally, a 6- or 12-mL syringe is used. It should be readily available throughout the procedure, but the syringe should not be placed in a pocket, out of sight. Securing a syringe case to an accessible area of the anesthesia machine provides reliable storage for constant availability.

Laryngoscope or Light Source

The use of some type of light source significantly enhances the process of intubation. Easy visualization of the larynx permits greater success of first attempts to intubate. Laryngoscopes are composed of two major parts: the blade and the handle (Figure 2-35). The blade houses the light bulb and can be curved or straight. Curved blades are commonly identified as Miller blades, and straight blades are often called Wisconsin blades. The numbers included in the identification process refer to the length of the blade. The higher the number, the longer the blade. Often, “0” blades work well with cats, No. 1 blades for small dogs, No. 2 for medium-sized dogs, and No. 3 blades for large dogs. The handle houses the batteries that power the laryngoscope. Alternative light sources include floor lamps and overhead lights.

Mouth Speculum

The use of a mouth speculum is not necessary, but its use can be advantageous to some. First, the mouth can be opened wider to allow better visualization, therefore increasing success rates for endotracheal intubation. Second, the speculum prevents the patient from biting the ET tube if the patient transitions into a lighter stage of anesthesia. Third, the speculum helps the restrainer keep the mouth open.

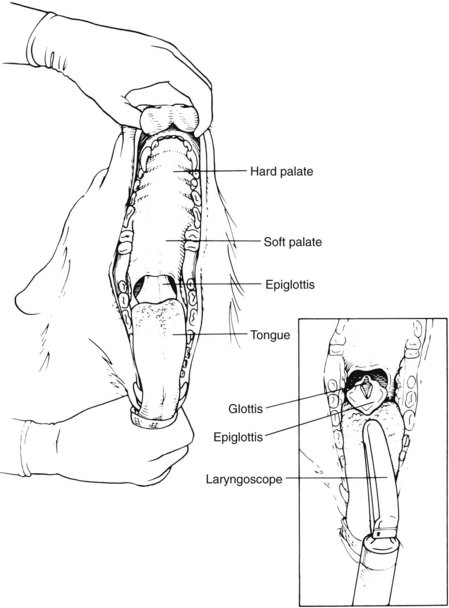

Tube Placement

Proper knowledge of the anatomy of the throat is critical to placement of the ET tube. Proper recognition of structures assists in the detection of abnormalities and helps ensure proper placement of the tube. Figure 2-36 displays the anatomy of the throat. When one is viewing the throat, the following structures can be seen: vocal folds, epiglottis, and glottis. The vocal folds are the most lateral structures, located on the lateral edges of the glottis. The epiglottis is a triangular flap of tissue that covers (or protects) the glottis when in the “up” or most dorsal position. The epiglottis must be lying down for intubation to be accomplished. The vocal folds are located on the lateral edges of the glottis. The glottis is the most ventral opening in the throat. The esophagus runs along the dorsal surface of the trachea, just left of center.

One-Person Technique

Box 2-7 describes the technique for performing single-person endotracheal intubation.

Two-Person Technique

Box 2-8 describes the technique for performing two-person endotracheal intubation.

Laryngospasms

Certain species, most often cats and rabbits, experience the phenomenon of laryngospasm during endotracheal intubation. If excessively stimulated, the muscles of the larynx spasm, and the vocal folds clamp shut. Application of 0.05 mL of 2% lidocaine to each vocal fold (dripping the lidocaine out of a tuberculin syringe onto the vocal folds with the needle removed) just before attempting intubation will significantly decrease the occurrence of laryngospasm. Care must be taken with this step because laryngeal paralysis can occur. A safer tactic to avoid laryngospasm is good technique. Repeated stimulation of the area may cause the muscles to spasm, so avoiding unnecessary touching of the area until the tube is actually passed is beneficial.

Confirmation of Proper Tube Placement

The following methods are used to confirm proper placement of the ET tube:

Cough: Many animals cough as the tube is passed into the trachea. Although fairly accurate, this method can be deceiving because as the animal coughs, the ET tube may move off the glottis and into the esophagus as it is advanced.

Fogging in the tube: When an ET tube has been properly placed in the trachea, there should be fogging of the lumen of the tube with each expiration. This method can be employed only if a clear tube is used.

Blowing of gauze or hair: A few strands of gauze or hair placed at the connector end of the ET tube blow away with each expiration if the tube is correctly placed. A disadvantage is that the hair may move from the tube because of excessive movement of room air rather than expiration.

Air movement: If the ET tube is in the trachea, forced air should be felt at the connector end of the tube with each expiration. Bilateral chest compressions can be used with this method to ensure placement. Care must be taken to avoid compressing the abdomen, because an incorrectly placed tube may provide a false-positive assessment.

Palpation: Palpation of the ventral neck should result in the identification of one “tube.” If the ET tube is in the trachea, only one firm, tubelike structure should be felt. If the ET tube is in the esophagus, however, two firm, tubelike structures are palpated.

Whatever method is used to ascertain correct tube placement, it should be performed before the patient is connected to the anesthesia machine. Once the patient is connected to the machine, a double check of placement can be done. Movement of the flutter valves and the rebreathing bag with each inspiration and expiration confirm proper placement. A stethoscope can also be used to auscultate bilateral lung sounds, the presence of which ensures that the tube has not migrated too far down in the trachea.

Once the patient is successfully intubated, the intended surgical site can be prepared.

Patient Preparation

Proper preparation (“prepping”) of the surgical patient is a critical part of the surgical process. The veterinary technician should be the primary staff member responsible for this task. Proper prepping should include the following steps:

• Extremely dirty patients may require a bath before surgery. The bath decreases overall body soil and aids in reducing the risk of postoperative complications from iatrogenic contamination. However, the patient’s hair coat must be completely dry before general anesthesia is induced. Wet animals are at an increased risk of hypothermia while under anesthesia.

• A double check (with the neck ID band, cage card, and medical record) and triple check (with the surgeon) of the patient’s correct identity and exact procedure are made. Cross-check that the consent form has been signed by the client for the correct procedures. If the procedure is an amputation, double-check (with the record and consent form) and triple-check (with the surgeon) that the correct limb is being prepared. Any radiographs taken before anesthesia should be in the surgery room and hung on the view boxes.

Anesthesia Form

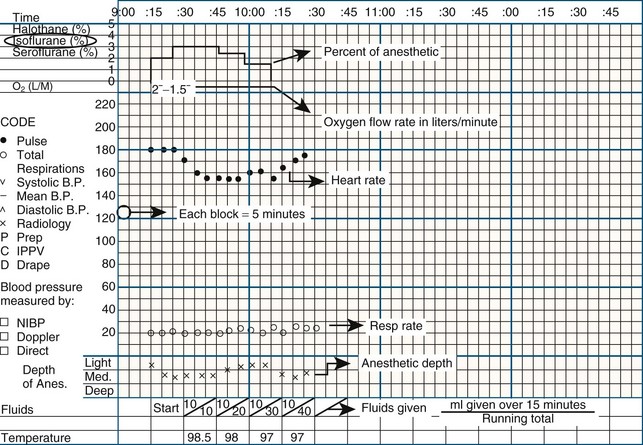

The anesthesia form “tells the story” of the anesthesia event from beginning to end. It is an important piece of the patient’s medical record and can serve as a legal document. It can help guide the choice of anesthetic protocols to follow in the future. The anesthesia form documents vital signs and their trends intraoperatively. For example, a graph of the patient’s blood pressure may be a line that goes down over time, with an occasional spike as the procedure proceeds, indicating that the trend for the overall blood pressure is dropping, which is a cause for concern.

The anesthesia form should be filled out completely and accurately, starting the minute the patient is given any premedications. The following paragraphs entail the information typically found in each section of the form.

Demographics

The demographics section records the owner’s name and the patient’s signalment, with date of birth (DOB). The technician should fill in the blanks using the information from the medical record.

Preanesthetic Values and Disposition

The preanesthetic values and disposition section of the anesthesia form records the date and patient’s weight, identifies the clinician, and lists the surgical procedure(s) to be performed, as follows:

Weight: Be sure to enter both pounds (lb) and kilograms (kg).

Procedures: More than one procedure may be done. List the procedures in the order they will be performed.

Preanesthetic values (Pre-anes. values): Temperature (Temp), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), mucous membrane color and capillary refill time (MM/CRT), packed cell volume (PCV), total protein (TP), renal function, and hydration are the values obtained just before premedication is given.

ASA status: The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) rating system is used to assess a particular patient’s risk for an anesthetic procedure, helping to define the patient’s anesthetic risk category (Table 2-5).

TABLE 2-5

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Rating System for Anesthetic Risk (ASA Status)*

| Category | Physical Condition | Examples Of Possible Situations |

| Class I: Minimal risk | Normal healthy patient with no underlying disease | Ovariohysterectomy; castration; declawing procedure; hip dysplasia radiographs |

| Class II: Slight risk | Patient with slight to mild systemic disturbances Patient able to compensate; no clinical signs of disease |

Neonatal or geriatric patients; obese patients; fracture without shock; mild diabetes; compensated heart or kidney disease; full-blown estrus |

| Class III: Moderate risk | Patient with moderate systemic disease or mild clinical signs | Anemia; anorexia; moderate dehydration; low-grade kidney disease; low-grade heart disturbances, heart murmur, or cardiac disease; moderate fever |

| Class IV: High risk | Patient with preexisting systemic disease or severe disturbances | Severe dehydration; shock; anemia; uremia or toxemia; high fever; uncompensated heart disease; diabetes; pulmonary disease |

| Class V: Grave risk | Surgery often performed in desperation on patients with life-threatening systemic disease or disturbances not correctable by surgery; includes all moribund patients not expected to survive 24 hours | Advanced cases of heart, kidney, liver, lung, or endocrine disease; profound shock; major head injury; severe trauma; pulmonary embolus |

*ASA recommends that every patient with ASA status of III, IV, or V have a responsible person solely dedicated to managing the patient during the anesthetic period. However, more veterinarians are finding it advantageous to have an anesthetist assigned to all patients under anesthesia.