Neck

The Neck – Seamless Connectivity

Boundaries

The boundaries of the neck (Collum/Cervix) towards the head, trunk, and shoulder girdle are diffuse. Fish have no necks; their heads adjoin to the trunk and shoulder girdle. Terrestrial animals possess necks, however, the neck is not a fundamental novelty, rather the head-trunk-boundary was stretched or protracted, so to speak. This explains many features such as the fact that cranial nerves participate in the innervation of the shoulder muscles and that the arm is innervated by nerves which emerge from the cervical vertebral column (see below).

If not the soft tissues but the bony structures are used to determine the boundaries of the neck, the upper borders of the neck are defined by the mandible and occipital bone and the lower borders by the clavi- cle and superior margin of the Scapula. Towards the centre of the chest, the neck transitions into the thoracic aperture (i.e. through the bony ring comprising of the first rib, the first thoracic vertebra, and Sternum) into the mediastinum of the thorax.

Nape

If one touches the back of the neck, the nape (Regio cervicalis posterior), one palpates almost nothing but muscles: below the thin muscular layers of the M. trapezius on both sides of the vertebral column the powerful strands of the autochthonous (intrinsic) back muscles (→ p. 76, vol. 1) are located. They act as muscles of the neck and insert at the base of the occiput. The spinous processes of the upper six cervical vertebrae (Vertebrae cervicales) cannot be palpated as they lie below a dense sagittal tendon sheath, the nuchal ligament (Lig. nuchae). However, the spinous process of the 7th cervical vertebra is visible and palpable, hence its name Vertebra prominens.

Anterior Cervical Region

If one applied the same force to grab the anterior cervical region (Regio cervicalis anterior = Trigonum colli anterius) as is possible for the nape, this would result in very unpleasant and painful sensations. As much as muscles determine the appearance of the nape, sensitive organs such as the viscera of the mediastinum extend into the anterior aspect of the neck. The lateral borders of the anterior cervical region are marked by both the Mm. sternocleidomastoidei which turn the head. Turning the head to either side causes the slim, actively flexed muscle belly of the M. sternocleidomastoideus of the opposite side to protrude.

The jugular fossa (Fossa jugularis) is located at the base of the anterior cervical region between the clavicles and immediately above the Sternum. Applying pressure with one’s finger directly at the jugular fossa compresses the Trachea and causes a feeling of being strangled. The Oesophagus is located posteriorly to the trachea and extends towards the Larynx. The Oesophagus is impalpable, but one feels its posterior proximity to the Trachea when swallowing an overly large and hard-edged bolus. The bolus presses ventrally on the Trachea, since the extensibility of the Oesophagus is limited dorsally by the proximity of the Oesophagus to the cervical vertebral column.

Palpating along the Trachea from the jugular fossa towards the head, one reaches the skeleton of the Larynx; in men, the Adam’s apple (Prominentia laryngea) projects prominently. At about the level of the Adam’s apple, the Larynx separates the airways (anterior) and the alimentary passage (dorsal). The Larynx is very mobile, and is held only by muscle loops. When swallowing, it moves cranially by as much as one entire cervical vertebra. The thyroid gland (Glandula thyroidea), located next to the Trachea and the lower part of the Larynx, consists of two large right and left lobes, which are hardly palpable – except in case of a goitre, an abnormal enlargement of the thyroid gland.

The cavity located cranially to the Larynx is named the Pharynx. Airways and alimentary passage cross at this point. Mouth and nasal cav- ities also open into the Pharynx. Pressing the thumb and index finger on both sides of the Larynx and moving them upward along the side of the neck towards the mandible while applying pressure causes major discomfort. This area is referred to as the Trigonum caroticum, where the pulse of the common carotid artery, A. carotis communis, is pal- pable very easily. This is where the common carotid artery divides into its two terminal branches, the A. carotis externa and the A. carotis interna. If one slightly increases the external pressure, a bone is palpable in this region: the greater horn of the hyoid bone (Os hyoideum). Pro- vided one has the courage to swallow while applying pressure, one notices the upward movement of the hyoid bone and Larynx. In fact, the hyoid bone is a “tension rod” of the Larynx, where some pharyngeal muscles attach and engage when swallowing. With further increased firm pressure the A. carotis is pressed against the hyoid bone (and the thyroid cartilage) – which can result in fainting (syncope) – or the hyoid bone can fracture, and in this case the blocking of the passage to the Larynx leads to suffocation. Therefore medical examiners investigate the hyoid bone meticulously in doubtful causes of death.

Ensheathed in a common fascia (Vagina carotica), the A. carotis communis, the V. jugularis interna, and the N. vagus [X] descend bilaterally along the continuum of the Trachea, the Oesophagus, the Larynx, and the Pharynx. The A. carotis communis arises from the aortic arch on the left-hand side or the Truncus brachiocephalicus on the right-hand side. The V. jugularis interna collects blood from the intracranial sinuses and the viscerocranium. The N. vagus [X], a cranial nerve, descends towards the mediastinum and into the abdominal cavity. In the lower part of the anterior cervical region and in close proximity to the clavicle the M. sternocleidomastoideus largely overlies this neurovascular bundle.

The Lateral Cervical Region

The lateral cervical region (Regio cervicalis lateralis = Trigonum colli laterale) is confined caudally by the clavicle (Clavicula), medially by the M. sternocleidomastoideus and dorsally by the M. trapezius. The broadly defined inner space of the Trigonum extends – without sharp margins – under the clavicle and into the armpit (Axilla). The Trigonum colli laterale contains the large neural pathways descending steeply from the cervical vertebral column to the arm. Most nerves supplying the arm (Plexus brachialis) emerge from the cervical vertebral column. The Trigonum also encompasses the great vessels of the arm (A./V. subclavia), which come from the mediastinum, through the superior thoracic aperture, and descend behind the clavicle first into the Trigonum and then into the Axilla. There is hardly anything palpable, not even the pulse of the A. subclavia, because it lies deep in the Trigonum, slightly behind the clavicle. There is also hardly anything visible as in a slim neck the skin covering the Trigonum over the clavicle forms the Fossa supraclavicularis major. Sometimes, the large cutaneous vein of the neck, the V. jugularis externa, is visible through the skin; if one gri- maces, the great cervical cutaneous muscle (Platysma) stretches the thin skin of the neck.

→Dissection Link

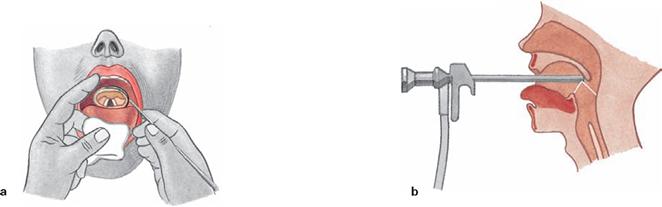

Dissection of the neck from ventral: After exposing and reflecting the Platysma superiorly, the epifascial nerves of the Plexus cervicalis are demonstrated. Subsequently, the superficial fascia of the neck is removed, followed by dissection of the M. sternocleidomastoideus, the anterior border of the M. trapezius and the N. accessorius [XI] in the lateral triangle of the neck. Upon removal of the middle fascia of the neck and exposure of the infrahyoid muscles, the Vagina carotica is exposed together with the Aa. carotides communis, externa and interna, the V. jugularis interna, and the N. vagus [X]. The M. sternocleidomastoideus is severed at the clavicle and deflected superiorly. The bilateral exarticulation of the clavicle is followed by the complete representation of the infrahyoid muscles with Ansa cervicalis, by the detachment of the infrahyoid muscles which insert at the Sternum, the visualisation of the thyroid gland and its ventral blood supply as well as the dissection of the large vessels between head and arm, and of Mm. scaleni, Plexus brachialis, N. phrenicus, Glandula submandibularis and its adjacent vessels, and the Larynx from ventral and lateral. Subsequently, after the presentation of the sympathetic trunk on the cervical vertebral column, the head is exarticulated at the atlanto-occipital joint of the cervical vertebral column and, together with attached cervical structures, removed from the torso. After preparation of the Pharynx from the dorsal side and illustration of the cerebral nerves, the Pharynx is opened dorsally in the median line. This is followed by the dissection of the Larynx from the dorsal side with a presentation of the vocal folds and the laryngeal muscles. Finally, the ventral aspect of the Larynx is dissected.

Muscles

Regions of the neck

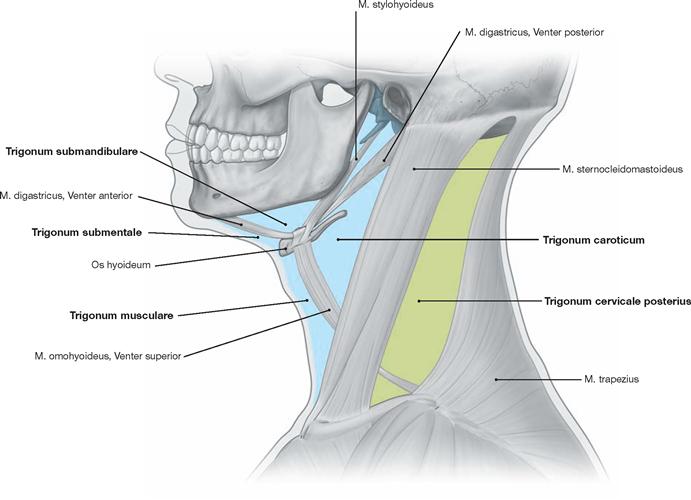

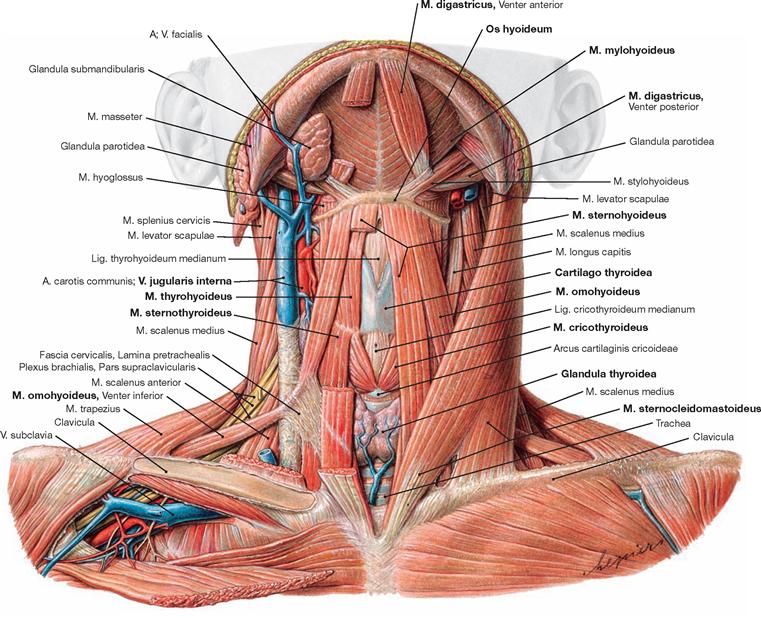

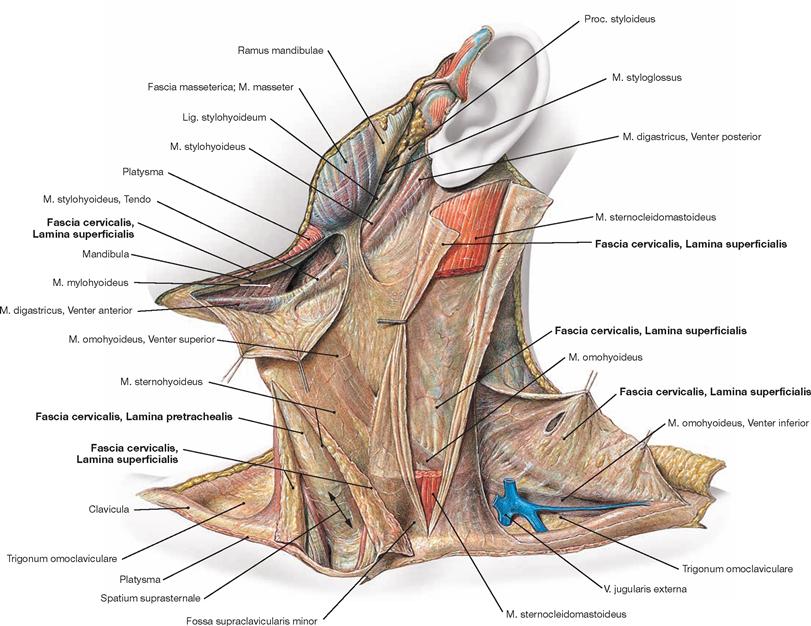

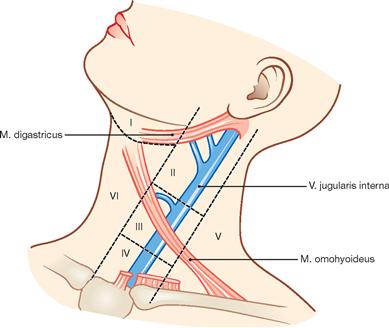

Fig. 11.1 Anterior and lateral regions of the neck; Regiones cervicales anterior et lateralis, left side; lateral view. [8]

Boundaries of the anterior triangle of the neck (Regio cervicalis anterior [Trigonum cervicale anterius]) are the lower rim of the mandible, the anterior rim of the M. sternocleidomastoideus, and the Linea mediana cervicis. Located within the anterior triangle of the neck are the Trigonum submandibulare (margins: lower rim of the Mandibula, Venter anterior and Venter posterior of the M. digastricus), the Trigonum submentale (margins: Os hyoideum, Venter anterior of the M. digastricus, Linea mediana cervicis), the Trigonum musculare (margins: Os hyoideum, Venter superior of the M. omohyoideus, M. sternocleidomastoideus, midline of the neck), and the Trigonum caroticum (margins: Venter superior of the M. omohyoideus, the lowest part of the M. stylohyoideus, Venter posterior of the M. digastricus, M. sternocleidomastoideus).

Boundaries of the posterior triangle of the neck (Regio cervicalis posterior [Trigonum cervicale posterius]) are the posterior rim of the M. sternocleidomastoideus, the anterior rim of the M. trapezius, the upper rim of the clavicle and the Os occipitale.

Neck muscles

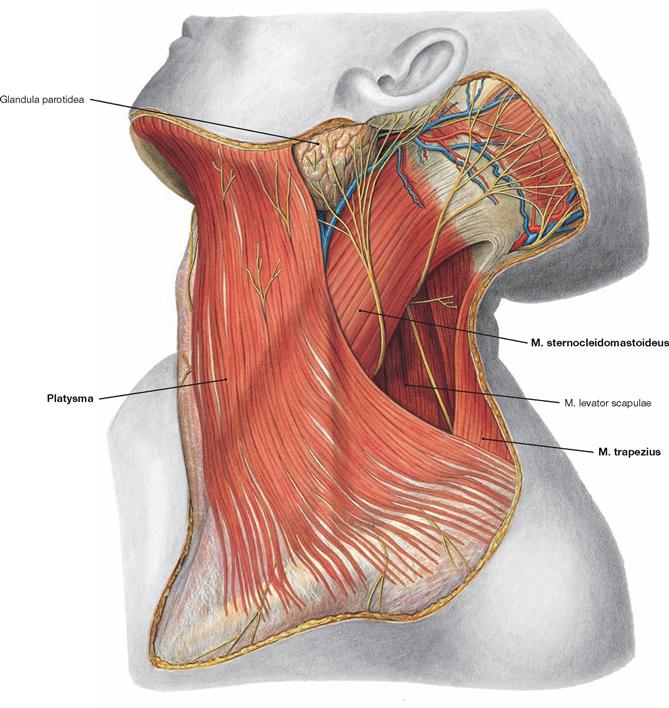

Fig. 11.2 Muscles of the anterior and lateral neck regions, Regiones cervicales anterior et lateralis, superficial layer; left side; lateral view.

The Platysma (a mimetic muscle without fascia) is a thin muscular plate and locates superficially directly under the skin. It extends from the mandible, across the clavicle, and onto the Thorax. The posterolateral part of the superficial neck fascia has been removed. The upper part of the M. sternocleidomastoideus is a reference point during surgical interventions. Located further posterior and inferior, the anterior rim of the M. trapezius becomes visible. The lower pole of the Glandula parotidea lies between the Platysma and the M. sternocleidomastoideus and can extend into the neck region to a variable degree. The M. levator scapulae is visible deep in the posterior triangle of the neck.![]()

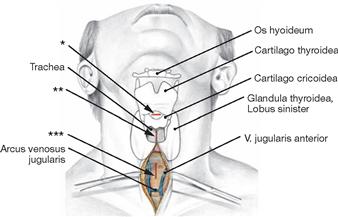

Neck muscles and tracheotomy

Fig. 11.3 Neck muscles, Mm. colli; ventral view; chin elevated.

The superficial M. sternocleidomastoideus has two origins (Caput sternale and Caput claviculare) and extends to the Proc. mastoideus. Its caudal section covers the origin of the infrahyoid muscles with the Mm. sternohyoideus, sternothyroideus, thyrohyoideus and omohyoideus, which stretch between the Sternum, thyroid cartilage, hyoid bone, and Scapula (M. omohyoideus). The M. omohyoideus is composed of two bellies separated by an intermediate tendon affixed to the connective tissue of the carotid sheath (Vagina carotica) and serves to keep the lumen of the V. jugularis open. The isthmus of the thyroid gland, the paired M. cricothyroideus (an outer laryngeal muscle), the thyroid cartilage, and the hyoid bone are located beneath the infrahyoid muscles (from caudal to cranial). Above the hyoid bone, the M. mylohyoideus forms the floor of the mouth.![]()

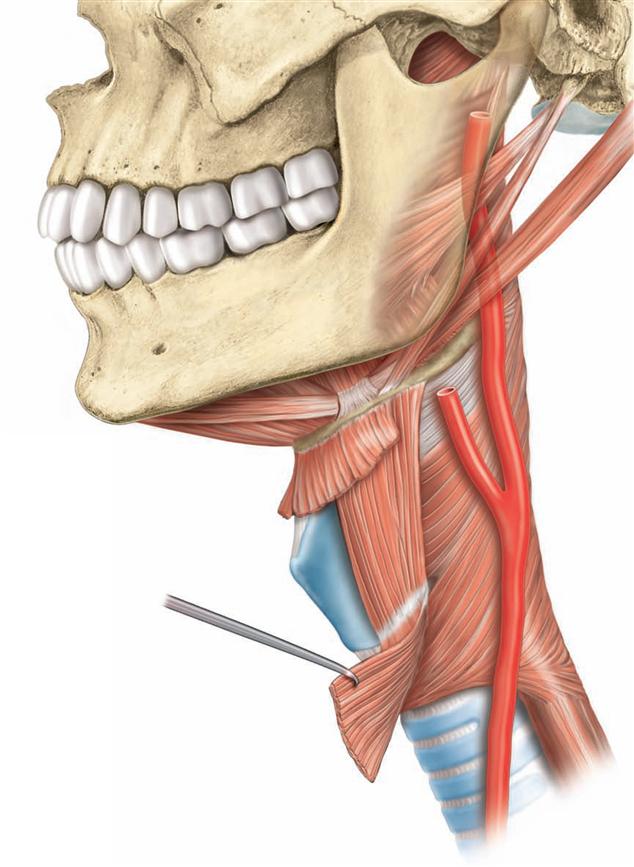

Fig. 11.4 Surgical access to the Trachea; ventral view; with the neck hyperextended dorsally.

During coniotomy, an incision or puncture through the Lig. cricothyroideum medianum (Lig. conicum, → Fig. 11.28) in between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages is performed to access the laryngeal lumen shortly beneath the vocal folds.

Performing a tracheotomy, there are three possible access routes: (i) an upper access above the isthmus of the thyroid gland, (ii) a middle access route by cutting through the isthmus, and (iii) a lower access below the isthmus of the thyroid gland (→ Fig. 11.50).

* coniotomy

** upper tracheotomy

*** lower tracheotomy

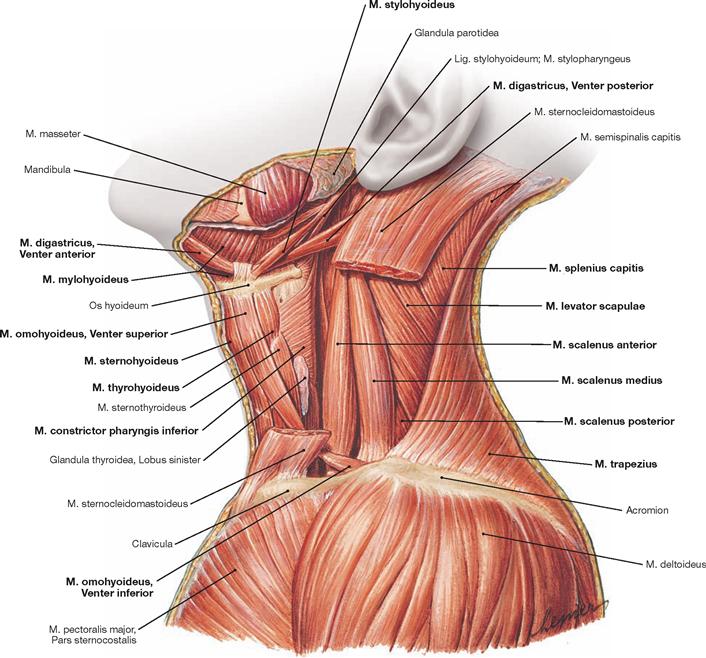

Neck muscles

Fig. 11.5 Neck muscles, Mm. colli; lateral view.

All muscle fascias, the Platysma, and the middle portion of the M. sternocleidomastoideus were resected. From anterior to posterior the following structures can be seen: the infrahyoid muscles with the Mm. sternohyoideus, omohyoideus (Venter superior; the Venter inferior runs above the clavicle in the lateral triangle of the neck), thyrohyoideus and sternothyroideus, parts of the pharyngeal muscles (M. con- strictor pharyngis inferior), the Mm. scaleni (anterior, medius, and posterior), the M. levator scapulae, the M. splenius capitis, and the M. trapezius. Above the hyoid bone, three suprahyoid muscles (M. digastricus with Venter anterior and Venter posterior, M. mylohyoideus, and M. stylohyoideus) are visible.![]()

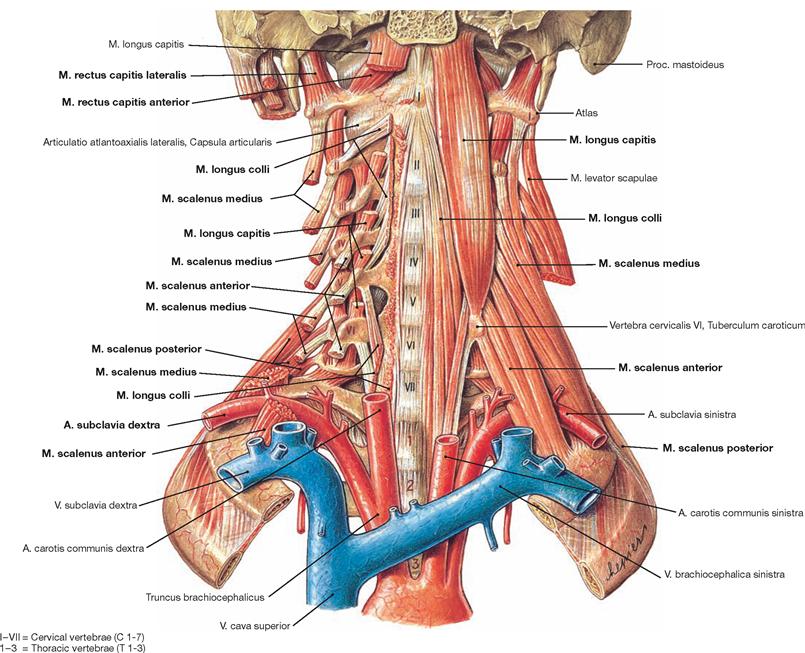

Prevertebral muscles

Fig. 11.6 Prevertebral muscles and Mm. scaleni; ventral view.

The prevertebral muscles are located on both sides of the vertebral bodies of the cervical and upper thoracic vertebral column and are covered by the Lamina prevertebralis of the Fascia cervicalis. The M. rectus capitis anterior stretches between the anterolateral parts of the Atlas and the Axis. In addition to the M. rectus capitis anterior, the M. longus capitis and the M. longus colli are prevertebral muscles. As part of the ventrolateral muscle group, the M. rectus capitis lateralis has migrated into the prevertebral region.

The Mm. scaleni anterior, medius, and posterior insert at the first ribs and form a triangular-shaped muscle plate in the lateral region of the cervical vertebral column. Together with the upper rim of the rib I, the M. scalenus anterior and M. scalenus medius create the scalene hiatus. The A. subclavia and the Plexus brachialis pass through the scalene hiatus (not shown).

Some authors distinguish between an anterior and posterior scalene hiatus. The anterior scalene hiatus represents the course of the V. subclavia anterior of the M. scalenus across rib I, while the posterior sca- lene hiatus marks the space between the Mm. scaleni anterior and medius for the A. subclavia and the Plexus brachialis to cross rib I. Since the anterior scalene hiatus is not a true gap, the term scalene hiatus should only be used for the space between the M. scalenus anterior and M. scalenus medius.![]()

Fasciae of the neck

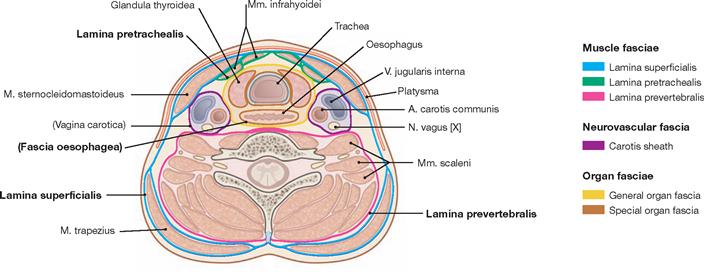

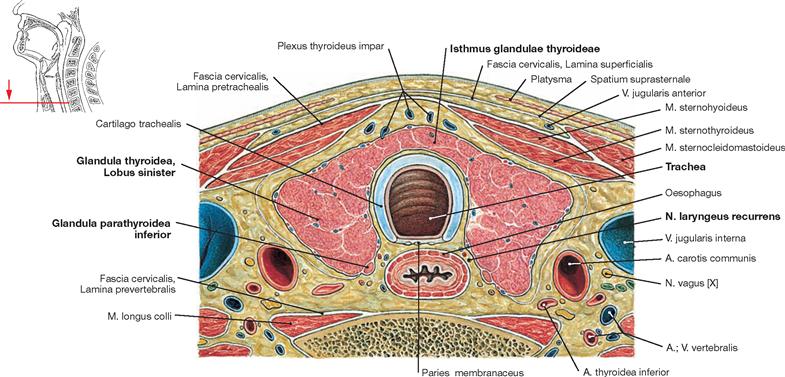

Fig. 11.7 Cervical fasciae, Fasciae cervicales; transverse section through the neck. [8]

A muscle fascia with three laminae can be distinguished from a neurovascular fascia, and an organ fascia with two laminae.

Muscle fasciae:

• Lamina superficialis (superficial lamina, encases the whole neck and ensheathes the M. sternocleidomastoideus as well as the Mm. levator scapulae and trapezius in the neck region)

• Lamina pretrachealis (middle lamina, ensheathes the infrahyoid muscles)

• Lamina prevertebralis (deep lamina, enwraps the Mm. scaleni, prevertebral muscles, the M. rectus capitis lateralis, and merges with the fascia of the intrinsic [autochthonous] muscles of the back)

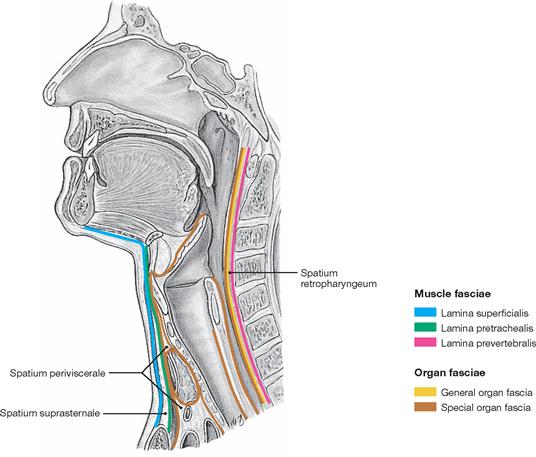

Fig. 11.8 Schematic drawing of the cervical fasciae, Fasciae cervicales; sagittal section through the neck at the level of the Larynx.

Above the Sternum, the Spatium suprasternale is formed between the superficial and middle cervical fasciae. The Spatium periviscerale is located in front of the Trachea and in between the middle cervical fascia and the general organ fascia. The Spatium retropharyngeum lies in a prevertebral space delineated by the middle cervical fascia and the general organ fascia (→ Fig. 11.17).

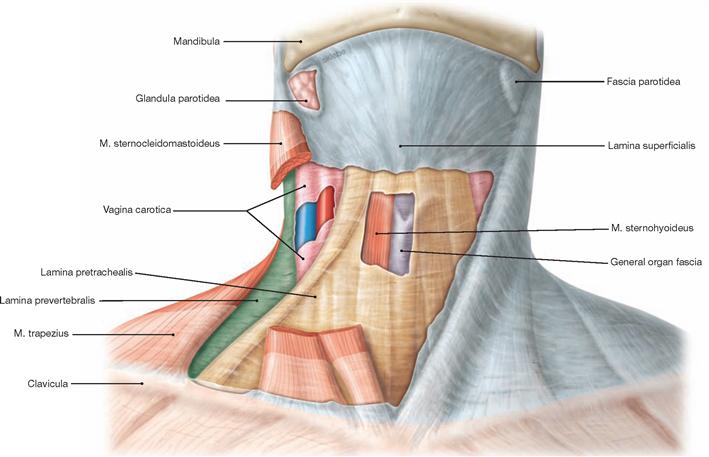

Fig. 11.9 Muscle fasciae of the neck, Fasciae cervicales; ventral view.

The Platysma was removed on both sides. On the right side, the superficial lamina of the cervical fascia is intact and ensheathes the M. sternocleidomastoideus. On the left side, most of the muscles and the superficial lamina of the cervical fascia were resected. Above the Larynx, a small part of the middle cervical fascia was removed to demonstrate the M. sternohyoideus, a muscle normally ensheathed by the middle cervical fascia, and the general organ fascia located below. The fenestrated carotid sheath and the deep cervical fascia are visible at the posterior margin of the M. omohyoideus.

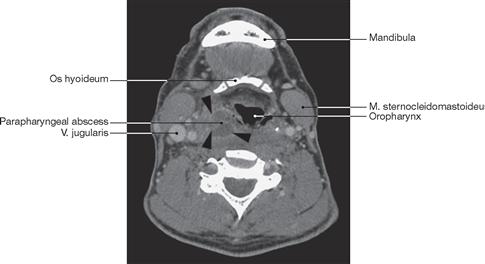

Fig. 11.10 Parapharyngeal abscess, left side; ventral view. [13]

The abscess extends along the anatomically defined space (Spatium lateropharyngeum) in the cervical region (black arrow tips).

Fig. 11.11 Cervical fascia, Fascia cervicalis, left side; ventrolateral view.

The superficial lamina of the cervical fascia (Fascia cervicalis, Lamina superficialis) has been opened and detached in various places. The superficial lamina of the cervical fascia that ensheathes the M. sternocleidomastoideus has been opened also and the middle portion of the M. sternocleidomastoideus has been resected. Thus, the fascial sheath and the deep part of the superficial fascia become visible. From the Incisura jugularis of the Sternum to the level of the Larynx the superficial lamina of the cervical fascia has been slit open and folded sideways to open up the Spatium suprasternale. Upon removal of the adipose tissue (frequently the Arcus venosus jugularis can be found here, → Fig. 11.17), the pretracheal (middle) lamina of the cervical fascia (Fascia cervicalis, Lamina pretrachealis) becomes visible, which forms the posterior wall of the Spatium suprasternale. In addition, the superficial lamina of the cervical fascia has been resected at the mandible and was folded downwards to demonstrate the tendon of the M. stylohyoideus, the M. mylohyoideus, and the Venter anterior of the M. digastricus. In the posterior triangle of the neck, the superficial cervical fascia has been removed from the clavicle and folded upwards. Beneath, the V. jugularis externa and the Venter inferior of the M. omohyoideus, ensheathed by the middle cervical fascia, are visible.

Pharyngeal muscles

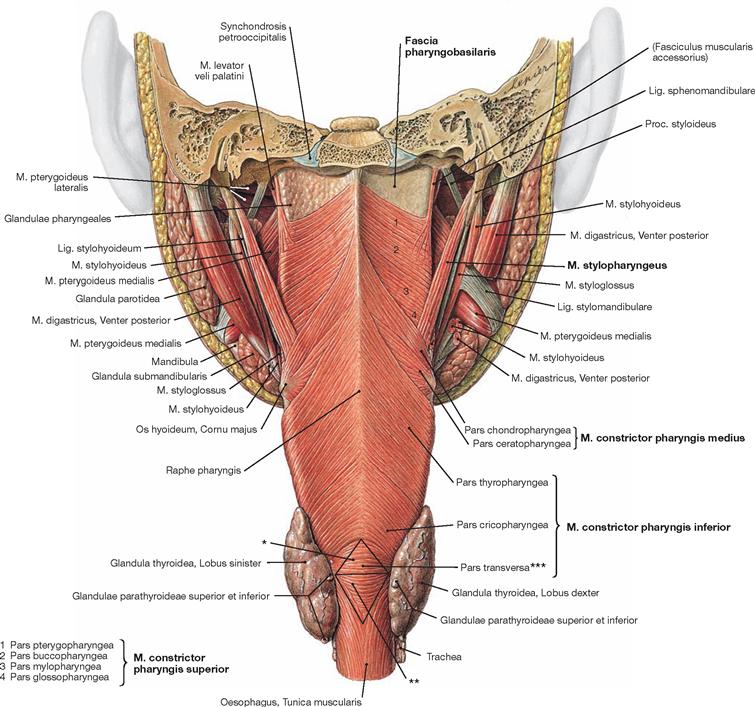

Fig. 11.12 Pharyngeal muscles, Mm. pharyngis; dorsal view.

The pharyngeal muscles (Tunica muscularis pharyngis) consist of the constrictor muscles (Mm. constrictores pharyngis) and three paired levator muscles elevating the Pharynx (Mm. levatores pharyngis). Tela submucosa and Tunica adventitia combine to form the Fascia pharyngobasilaris in a muscle-free upper part of the pharyngeal wall. Constricting and elevating pharyngeal muscles mainly act during swallowing, choking, and during speaking and singing.

The Mm. constrictores pharyngis superior, medius, and inferior consist of different parts. The muscles enclose the pharyngeal lumen like a horseshoe and overlap, with the lower muscle slightly covering the lower margin of the muscle above. The Pars cricopharyngea of the inferior constrictor muscle is composed of two muscle parts which together form a triangle weak in muscle fibres (KILLIAN’s dehiscence, also called KILLIAN’s triangle). On the dorsal side, at the transition from the Pars fundiformis of the inferior constrictor pharyngeal muscle to the Oesophagus, muscle fibres projecting upwards from the Oesophagus form a muscular triangle (LAIMER’s triangle). The tip of the LAIMER’s triangle points in the opposite direction to the tip of the KILLIAN’s triangle. The Pars fundiformis (of the Pars cricopharyngea of the M. constrictor pharyngis inferior) is the base of both triangles.

The muscles elevating the pharynx are the Mm. palatopharyngeus, salpingopharyngeus, and stylopharyngeus.![]()

* KILLIAN’s triangle or dehiscence

** LAIMER’s triangle

*** Pars fundiformis of the Pars cricopharyngea (KILLIAN’s muscle)

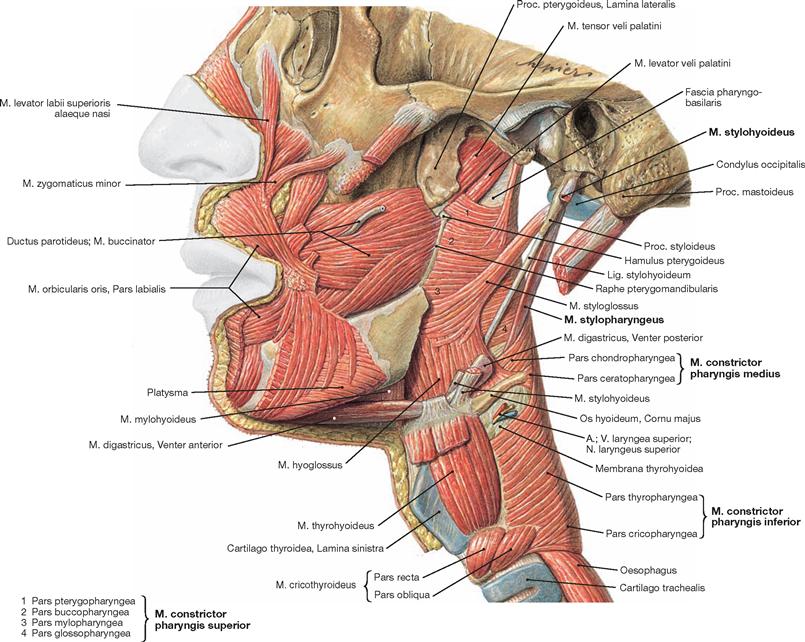

Facial and pharyngeal muscles

Fig. 11.13 Pharyngeal muscles, Mm. pharyngis, and facial muscles, Mm. faciei, left side; lateral view.

The pharyngeal muscles divide into constrictor muscles (Mm. constrictores pharyngis superior, medius, and inferior) and levator muscles (Mm. stylopharyngeus, salpingopharyngeus, and palatopharyngeus). This lateral view displays the different parts of the Mm. constrictores pharyngis and the M. stylopharyngeus.![]()

Clinics

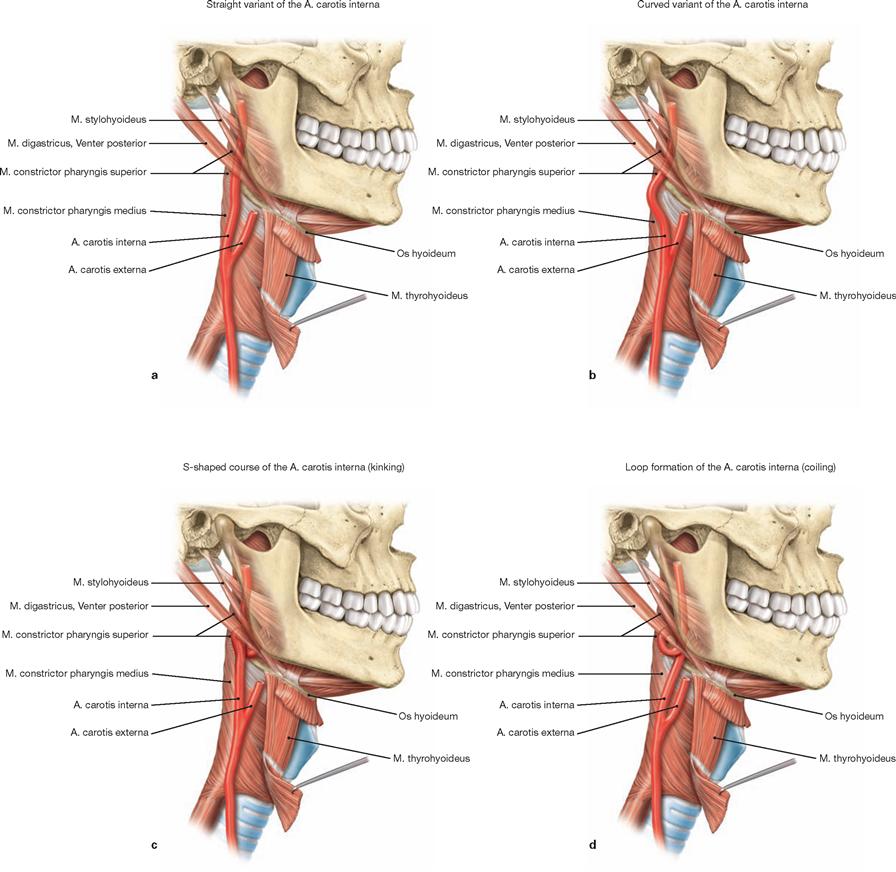

Fig. 11.14 a to d Variations in the course of the Pars cervicalis of the A. carotis interna in relation to the pharyngeal wall.

a. straight variant (frequency 66%)

b. curved variant (frequency 26.2%)

c. S-shaped course (frequency 6%, 2.8% thereof in close association with the pharyngeal wall)

d. loop formation (frequency 1.8%, 2.8% thereof in close association with the pharyngeal wall)

The S-shaped course and the loop formation are classified as dan- gerous carotid loops (c and d).

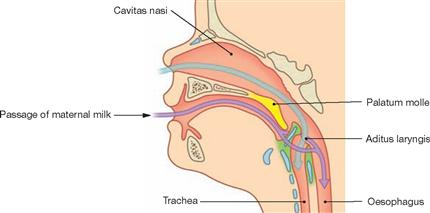

Fig. 11.15 Head of an infant; midsagittal section at the level of the nose and Larynx. [9]

Contrary to adults and children, an infant can drink and breath simultaneously. Since the Larynx locates relatively high in the neck, the Epiglottis reaches the Nasopharynx. Fluids (e.g. the breast milk from the mother) pass through the Recessus piriformes of the Larynx into the Oesophagus without entering the lower airways.

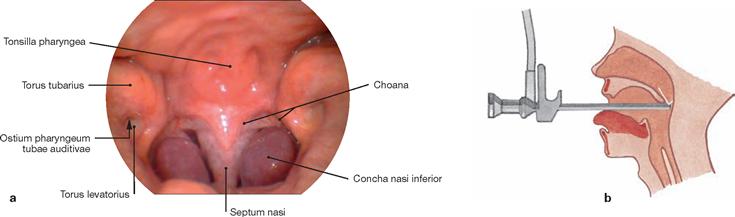

Fig. 11.16 a and b Nasopharynx; endoscopy of the Nasopharynx; posterior view at the Choanae, the opening of the Tubae auditivae and the Tonsilla pharyngea.

The endoscopic view from posterior into the nasopharyngeal space shows the posterior tips of the inferior nasal conchae on both sides and the pharyngeal opening of the Tuba auditiva [auditoria] (Ostium pharyngeum tubae auditivae). The inconspicuous pharyngeal tonsil (Tonsilla pharyngea) locates at the roof of the Pharynx.

Inner relief of the pharynx

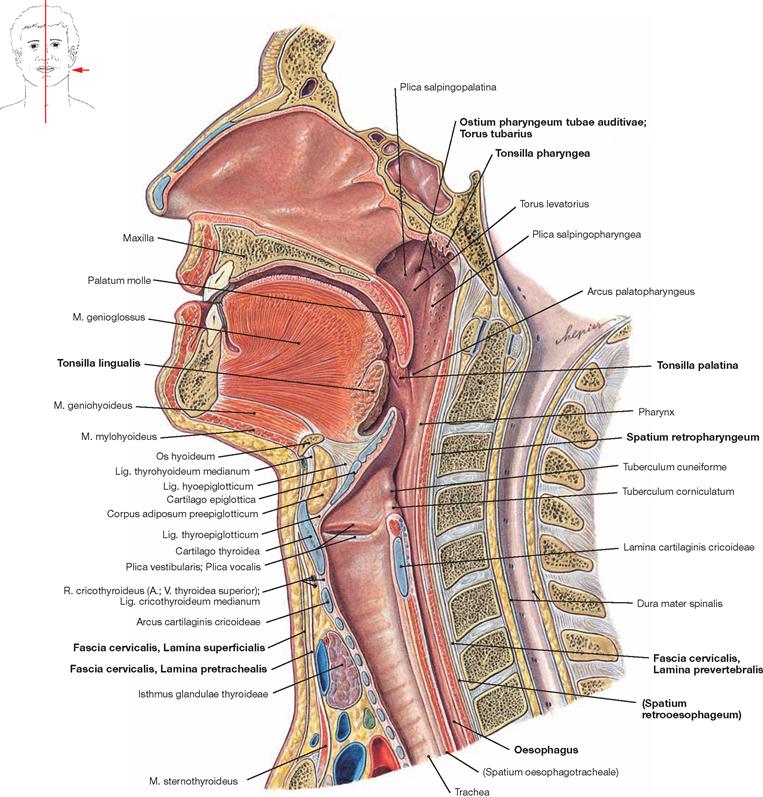

Fig. 11.17 Oral cavity, Cavitas oris, pharynx, Pharynx, and larynx, Larynx; midsagittal section.

Relationships of the different levels of the Pharynx to neighbouring structures:

• The Nasopharynx connects with the nasal cavity and the middle ear through the choanae and the Tuba auditiva, respectively.

• The Oropharynx represents the junction between the superior and inferior pharyngeal levels and connects with the oral cavity through the Isthmus faucium.

• The Laryngopharynx has an anterior connection with the Larynx through the Aditus laryngis and transitions caudally into the Oesophagus. Airways and alimentary passage cross within the Pharynx.

The WALDEYER’s ring consists of lympho-epithelial tissue, and is part of the immune defence of the body. Situated in the transitional space between the nasal and oral cavity, the WALDEYER’s ring is composed of the Tonsillae pharyngea, tubariae (not shown), palatinae and lingualis as well as lateral strands of lymphoid tissue located on the Plicae salpingopharyngeae.

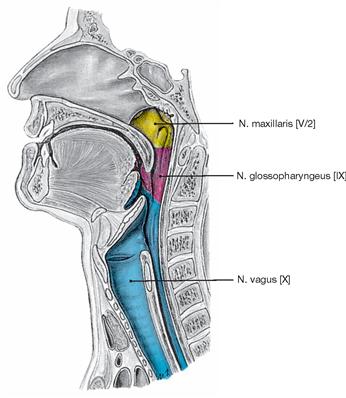

Levels and innervation of the pharynx

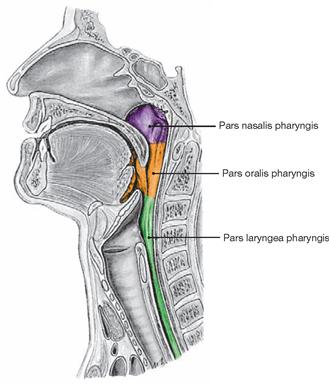

Fig. 11.18 Levels of the pharynx; midsagittal section.

According to its openings, the Pharynx can be devided into three levels:

Fig. 11.19 Sensory innervation of the pharynx; midsagittal section.

Sensory fibres of the second trigeminal branch (R. pharyngeus, a branch of the Rr. ganglionares [Nn. pterygopalatini] of the N. maxillaris [V/2]) contribute to the innervation of the Nasopharynx. Branches of the N. glossopharyngeus [IX] and the N. vagus [X] (N. laryngeus superior) innervate the rest of the Pharynx. Together with autonomic nerve fibres of the Truncus sympathicus, these fibres form a neuronal network at the outer surface of the Pharynx (Plexus pharyngealis). Afferent and efferent fibres of this Plexus pharyngealis are part of the vital swallowing and choking reflexes which remain active during sleep. The coordination of these complex reflexes takes place in the Medulla oblongata.

Pharynx

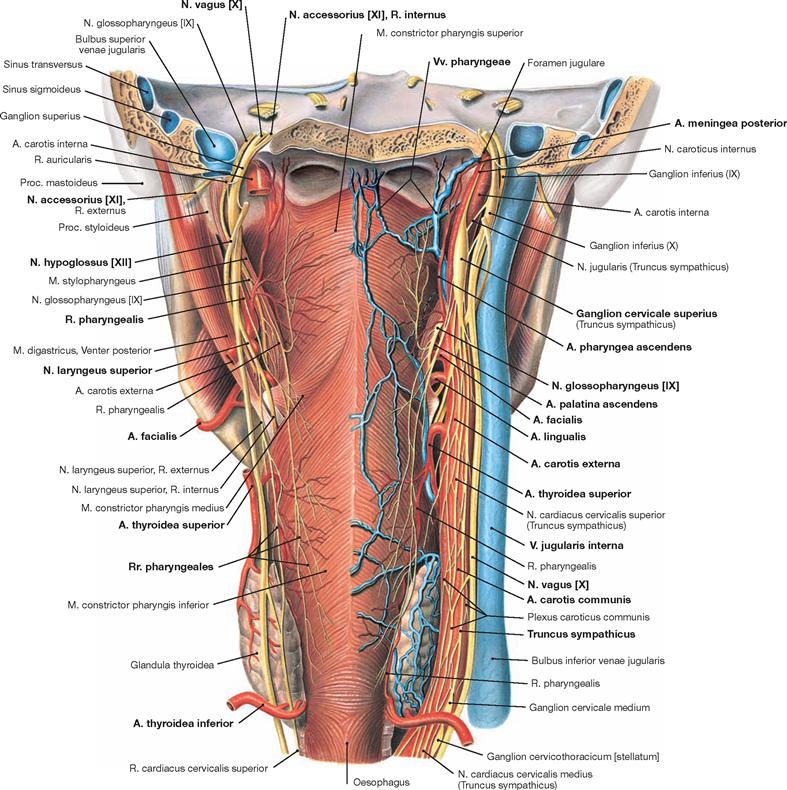

Vessels and nerves of the parapharyngeal space

Fig. 11.20 Vessels and nerves of the pharynx, Pharynx, and the parapharyngeal space, Spatium lateropharyngeum; dorsal view.

The main source of blood supply is the A. pharyngea ascendens. This artery ascends to the base of the skull in the parapharyngeal space medial of the neurovascular bundle of the neck. Its terminal branch, the A. meningea posterior, enters the posterior cranial fossa through the Foramen jugulare. Additional blood supply comes from the A. palatina ascendens in the region of the pharyngeal opening of the Tuba auditiva [auditoria] (Ostium pharyngeum tubae auditivae) and from the A. thyroidea inferior in the Hypopharynx.

The entire submucosa of the pharynx contains a venous plexus (Plexus pharyngeus). The venous drainage is performed by the Vv. pharyngeae into the V. jugularis interna and into the Vv. meningeae in the nasopharyngeal region.

The lymphatic drainage of the Tonsilla pharyngea and the pharyngeal wall reaches the Nodi lymphoidei retropharyngeales and the Nodi lymphoidei cervicales profundi (not shown).

Innervation: In addition to the Plexus pharyngealis and the N. pharyngeus of the N. maxillaris [V/2] (see sensory innervation of the Pharynx → Figs. 11.19 and 12.144), the N. glossopharyngeus [IX] provides motor innervation for the superior and some medial pharyngeal constrictor muscles and for the levator pharyngeal muscles; the N. vagus [X] innervates the lower part of the medial pharyngeal constrictor muscles and the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles.

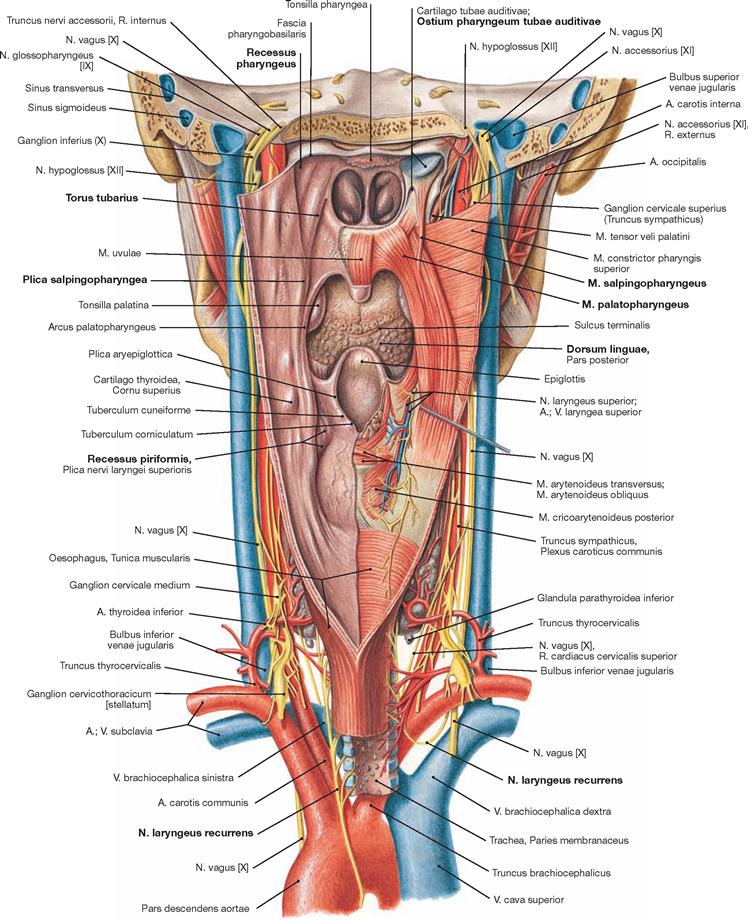

Fig. 11.21 Vessels and nerves of the pharynx, Pharynx, and the parapharyngeal space, Spatium lateropharyngeum; dorsal view. Pharynx opened from the dorsal side.

The pharyngeal opening of the Tuba auditiva [auditoria] (Ostium pharyngeum tubae auditivae) lies roughly at the level of the inferior nasal meatus. At its posterior and superior side, this opening displays an elevation, the Torus tubarius. Caudally, the Torus tubarius extends into a longitudinal mucosal fold (Plica salpingopharyngea) which is created by the M. salpingopharyngeus. The inferior part of the Ostium pharyngeum tubae auditivae displays another elevation, the Torus levatorius, which is formed by the M. levator veli palatini. This orifice is the entrance to the Tuba auditiva [auditoria] (EUSTACHIAN tube) and connects the Pars nasalis pharyngis with the tympanic cavity. Immediately behind the Torus tubarius there is a fossa (Recessus pharyngeus, fossa of ROSENMÜLLER) extending upwards to the roof of the Pharynx. The M. palatopharyngeus creates the lateral margin of the Isthmus faucium. The dorsal view also shows the dorsum of the tongue (Dorsum linguae), the dorsal side of the laryngeal wall, and the entrance to the Oesophagus. On either side of the posterior laryngeal wall lies the Recessus piriformis. Note the side difference in the course of the N. laryngeus recurrens; on the left side the nerve winds around the Arcus aortae and on the right side around the A. subclavia.

Larynx

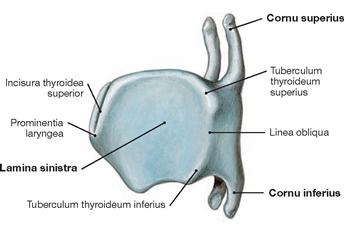

Skeleton of the larynx

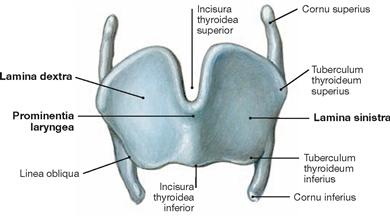

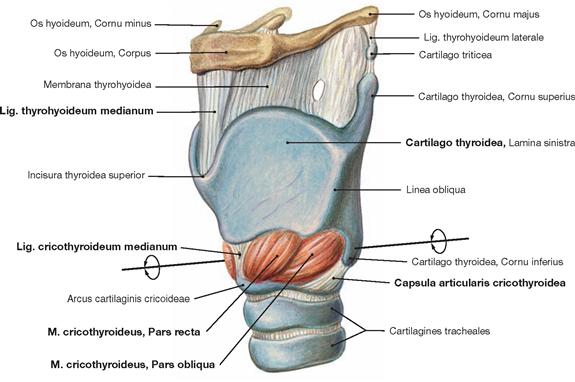

Fig. 11.22 Thyroid cartilage, Cartilago thyroidea; view from the left side.

The thyroid cartilage is composed of two laminae (Lamina dextra and Lamina sinistra) with a superior and an inferior horn.

Fig. 11.23 Thyroid cartilage, Cartilago thyroidea; ventral view.

Both laminae of the thyroid cartilage join at an angle of 90° and 120° in men and women, respectively.

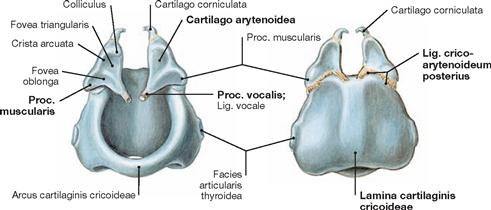

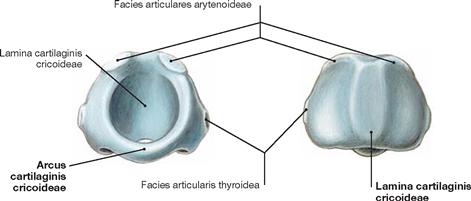

Fig. 11.24 Cricoid cartilage, Cartilago cricoidea, and arytenoid cartilages, Cartilagines arytenoideae; ventral and dorsal views.

The Lig. cricoarytenoideum posterius extends between the cricoid and arytenoid cartilages.

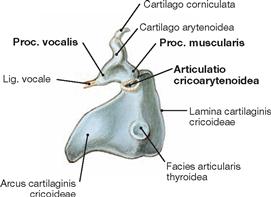

Fig. 11.25 Cricoid cartilage, Cartilago cricoidea, and arytenoid cartilages, Cartilagines arytenoideae; view from the left side.

The Articulatio cricoarytenoidea, a diarthrotic joint, connects the cricoid and arytenoid cartilages.

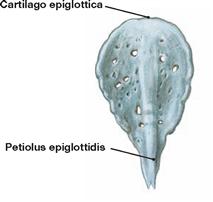

Fig. 11.26 Epiglottic cartilage, Cartilago epiglottica; dorsal view.

In contrast to the other major hyaline laryngeal cartilages, the Epiglottis is made of elastic cartilage.

Fig. 11.27 Cricoid cartilage, Cartilago cricoidea; ventral and dorsal view.

The cricoid cartilage has the shape of a signet ring.

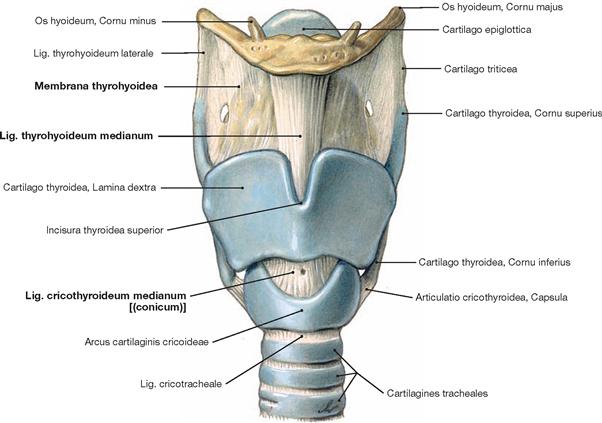

Hyoid bone and skeleton of the larynx

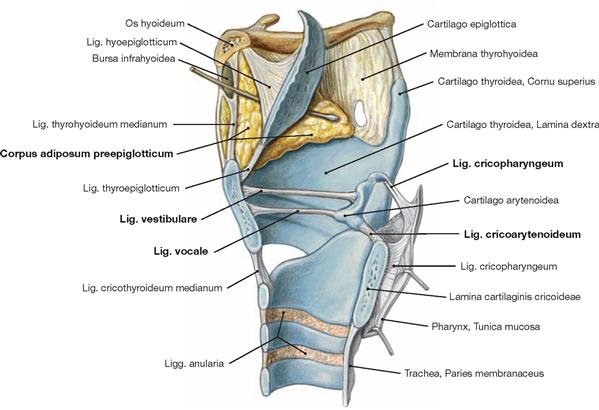

Fig. 11.28 Larynx, Larynx, and hyoid bone, Os hyoideum; ventral view.

Developmentally and functionally, the hyoid bone has a close relationship with the laryngeal skeleton. The individual parts of the laryngeal skeleton connect by syndesmoses and true joints (diarthroses).

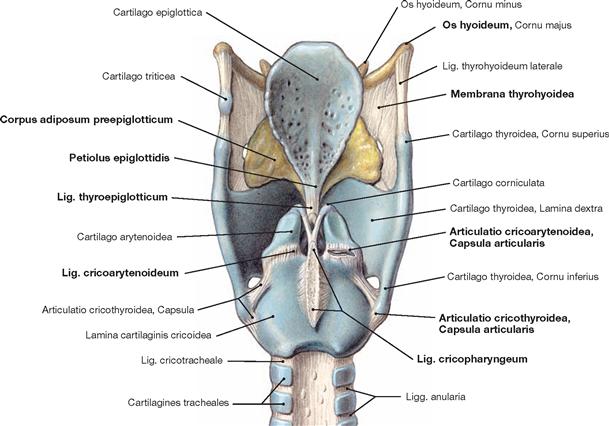

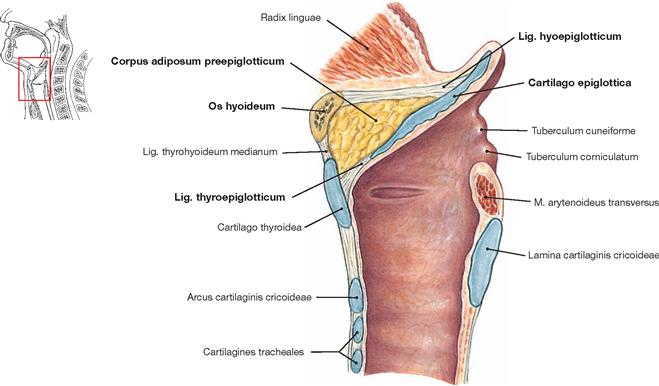

Fig. 11.29 Laryngeal cartilages, Cartilagines laryngis, and hyoid bone, Os hyoideum; dorsal view.

Beneath the Membrana thyrohyoidea an adipose body (Corpus adiposum preepiglotticum) extends in a cranial direction to the Lig. hyoepiglotticum and in a dorsocaudal direction to the frontal side of the Epiglottis. The Lig. thyroepiglotticum attaches the stalk of the Epiglottis (Petiolus epiglottidis) to the inside of the thyroid cartilage.

True joints of the Larynx are the Articulatio cricothyroidea, the paired joint between the cricoid cartilage (Cartilago cricoidea) and the inferior horns of the thyroid cartilage (Cartilago thyroidea) as well as the Articulatio cricoarytenoidea between the cricoid and arytenoid cartilages (Cartilago arytenoidea). The Lig. cricoarytenoideum and the Lig. cricopharyngeum act as dorsal reins for the arytenoid cartilage.

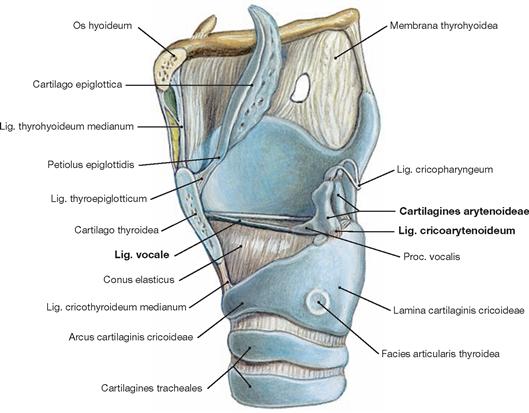

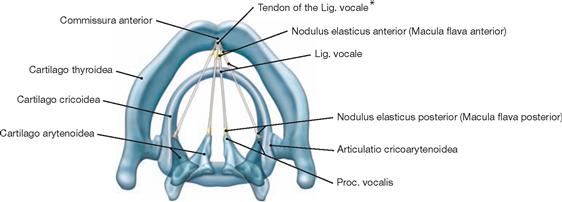

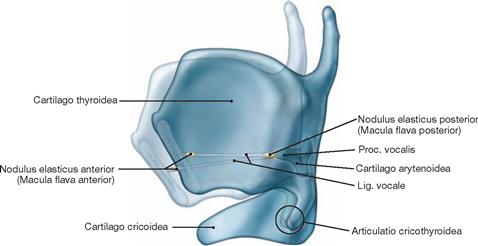

Fig. 11.30 Larynx, Larynx, and hyoid bone, Os hyoideum; view onto the Lig. vocale and the arytenoid cartilage from the left side; the left lamina of thyroid cartilage has been removed.

The cricoid (Cartilago cricoidea) and arytenoid cartilages (Cartilago arytenoidea) articulate in the Articulatio cricoarytenoidea. The articular surfaces of the cricoid cartilage are convex and oval in size (cylinder-shaped, → Fig. 11.27); the articular surface of the arytenoid cartilage is concave and more round. This shape of the articular cartilaginous components and the Lig. cricoarytenoideum (posterius) provide stability to the joint. Functionally, this ligament guides the arytenoid cartilage and counteracts the forces of the Lig. vocale.

Fig. 11.31 Larynx, Larynx, and hyoid bone, Os hyoideum; superior view.

The cricoarytenoid joint permits hinge and sliding motions parallel to the cylindrical axis; this joint primarily supports the opening and closure of the space between the vocal ligaments (Glottis, Rima glottidis) and also keeps tension on the vocal ligament (Lig. vocale). A hinge-like outward rotation results in elevation and abduction of the Proc. vocalis and, consecutively, an opening of the Glottis. Inward rotation through the hinge as well as depression and adduction of the Proc. vocalis cause the occlusion of the Glottis. These hinge-like movements can combine with gliding motions, whereby ventral or dorsal movement occurs during abduction and adduction of the arytenoid cartilage, respectively. The Lig. vocale and the Lig. vestibulare connect the arytenoid and thyroid cartilages.

* BROYLE’s tendon

Skeleton of the larynx

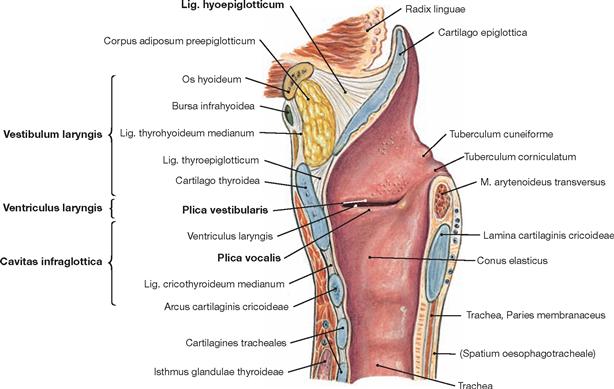

Fig. 11.32 Larynx, Larynx, and hyoid bone, Os hyoideum; median section, medial view.

The Articulationes cricothyroideae connect thyroid and cricoid cartilages. The cricoid and arytenoid cartilages articulate in the Articulatio cricoarytenoidea. The arytenoid and thyroid cartilages are connected by the Lig. vocale and the Lig. vestibulare. The Lig. cricoarytenoideum and Lig. cricopharyngeum act as a dorsal rein of the arytenoid cartilage. Lateral and in front of the Epiglottis the Corpus adiposum preepiglotticum is visible.

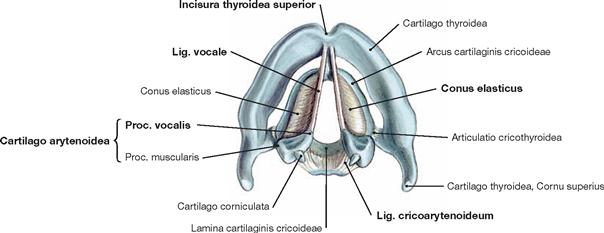

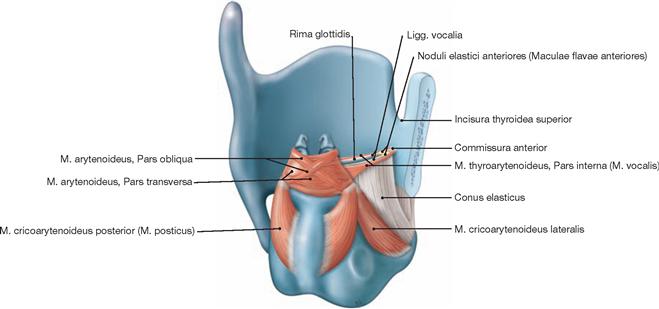

Fig. 11.33 Laryngeal cartilages, Cartilagines laryngis, and vocal ligament, Lig. vocale; cranioventral view.

The paired Lig. vocale stretches between the Proc. vocalis of the arytenoid cartilage (Cartilago arytenoidea) and the inside of the thyroid cartilage shortly below the Incisura thyroidea superior. The Conus elasticus is an elastic membrane and extends between the Lig. vocale and the upper rim of the cricoid cartilage. The Conus elasticus directs the airflow from the lungs in the direction of the Ligg. vocalia. The strong Lig. cricoarytenoideum is visible on the dorsal aspect of the arytenoid cartilage.

Laryngeal muscles

Fig. 11.34 Cricothyroid muscle, M. cricothyroideus; ventral view from the left side.

The cricoid cartilage (Cartilago cricoidea) and the thyroid cartilage (Cartilago thyroidea) articulate in the left and right Articulatio cricothyroidea. These are spheroidal joints with a firm joint capsule. This joint allows hinge-like motions in the transverse axis and small gliding (translatory) movements in the sagittal plane. Contraction of the M. cricothyroideus increases the tension of the vocal folds (→ Fig. 11.35).![]()

Fig. 11.35 Cricothyroid muscle, M. cricothyroideus; lateral view.

Contraction of the M. cricothyroideus causes the anterior part of the thyroid cartilage (Cartilago thyroidea) to rock towards the arch of the cricoid cartilage (Arcus cartilaginis cricoideae). This results in the elongation of the vocal ligament which is now under increased tension. During this rocking movement, the arytenoid cartilages (Cartilagines arytenoideae) are stabilised by the actions of the M. cricoarytenoideus posterior and the Lig. cricoarytenoideum.

Biomechanics of the vocal folds: The structures at the insertion site of the vocal ligaments (Noduli elastici anteriores and posteriores, BROYLE‘s tendon of the Lig. vocale, → Fig. 11.48) have biomechanical functions during the vibration of the Plicae vocales by equalising the different elastic modules of the vocal ligament, cartilage, and bone. This prevents the vocal ligaments from rupturing at their insertion points during vibration.![]()

Laryngeal muscles

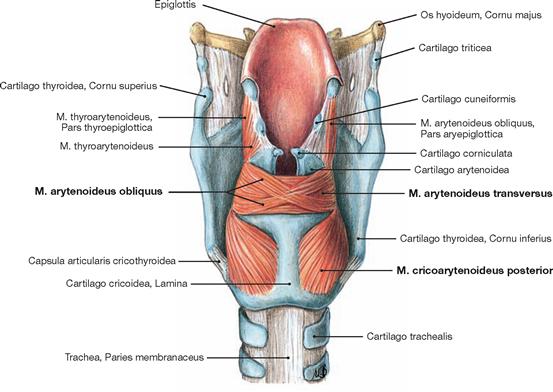

Fig. 11.36 Laryngeal muscles, Mm. laryngis; dorsal view.

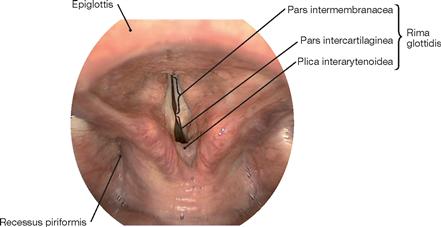

The actions of the Mm. laryngis determine the shape of the Rima glottidis and the tension of the vocal ligament. The M. cricoarytenoideus posterior (“posticus“) is mainly responsible for the abduction and elevation of the Proc. vocalis of the arytenoid cartilage resulting in the widening of the Glottis as part of the inspiration. All other muscles that act on the space between the vocal folds cause the narrowing of the Glottis and include the M. arytenoideus transversus and M. arytenoideus obliquus as well as the Mm. cricoarytenoidei laterales (→ Fig. 11.37).

Whispering is made possible by the isolated contraction of the M. cricoarytenoideus lateralis, which results in the so-called “whispering triangle”, the formation of a small triangular opening in the posterior part of the Rima glottidis (→ Fig. 11.43).![]()

Fig. 11.37 Laryngeal muscles, Mm. laryngis; dorsal view from an oblique angle.

In this particular view, the M. cricoarytenoideus lateralis and the Pars interna of the M. thyroarytenoideus (M. vocalis) are visible. The M. cricoarytenoideus lateralis closes the Rima glottidis. “Fine-tuning” of the vocal folds is performed by the M. vocalis (Pars interna of the M. thyroarytenoideus). Its muscle fibres run parallel to the Lig. vocale and to the vocal fold. The muscle creates a cushion which acts like the mouthpiece of a pipe. The tension of this mouthpiece is regulated by isometric muscle contractions and its length is shortened by isotonic muscle contractions. Thus, the actions of the M. vocalis have an important impact on sound quality and vocalisation.![]()

Levels and inner relief of the larynx

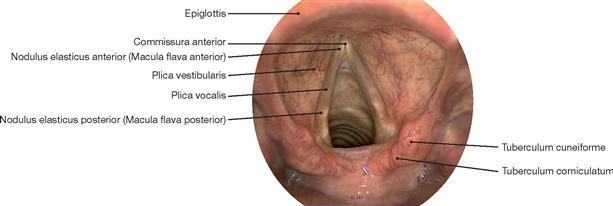

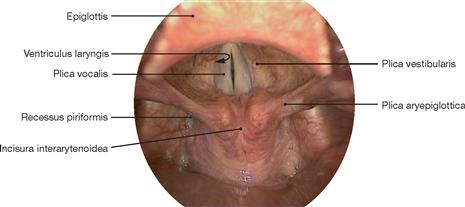

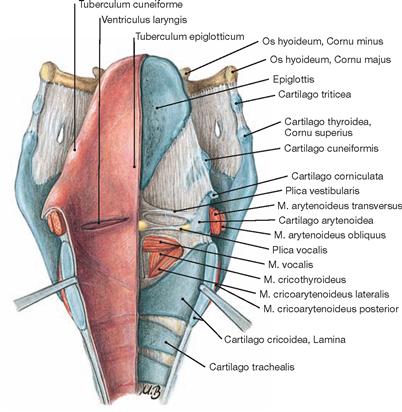

Fig. 11.38 Larynx, Larynx; dorsal view; the Larynx was sectioned from dorsal in the median plane and separated with hooks.

On the left side, the mucosal lining is shown; on the right side, the laryngeal muscles (M. vocalis [= Pars interna of the M. thyroarytenoideus], Mm. cricothyroideus, and cricoarytenoideus lateralis), the cartilages (Epiglottis, arytenoid, cricoid, and thyroid cartilages as well as the small laryngeal cartilages), and the mucosal folds (Plicae vestibularis and vocalis) are depicted.![]()

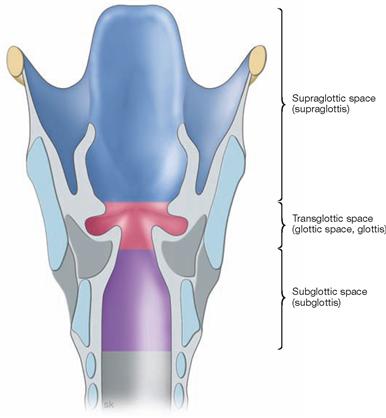

Fig. 11.39 Compartments of the larynx, Larynx.

Clinicians divide the larynx into the following spaces:

Supraglottic space (Supraglottis): This space extends from the Aditus laryngis to the level of the vestibular folds (Plicae vestibulares) and is divided into:

• Epilarynx: laryngeal area of the Epiglottis, Plicae aryepiglotticae and aryepiglottic folds

• Vestibulum laryngis: Petiolus epiglottidis, Plicae vestibulares = ventriculares, Ventriculus laryngis = MORGAGNI’s ventricle

Glottic space (Glottis): The area extends from the free rim of the vocal folds as opposed to the “transglottic space” which encompasses the space between Glottis, vestibular folds, and Ventriculi laryngis. The anterior part of the Glottis including the anterior commissure (Commissura anterior) is known as Pars intermembranacea; the dorsal part of the Glottis between the arytenoid cartilages is the Pars intercartilaginea (→ Fig. 11.43) and constitutes two-thirds of the Rima glottidis. In their dorsal part, the vocal folds end at the transition of the Pars intercartilaginea into the Plica interarytenoidea (→ Fig. 11.43).

Subglottic space (Subglottis): The Subglottis is the space that extends below the vocal folds to the lower rim of the cricoid cartilage (Cartilago cricoidea). It is a conical space between the free margin of the vocal fold, the area below the vocal fold, and the lower margin of the cricoid cartilage. The cranial border of the Subglottis is the macroscopically visible Linea arcuata inferior (→ Fig. 11.49) of the Plica vocalis. The caudal border is at the level of the lower rim of the cricoid cartilage. Craniolaterally, it is confined by the Conus elasticus, and further caudally by the cricoid cartilage. The caudal part of the Subglottis as- sumes a cylindrical shape, and tapers off at its cranial end due to the shape of the Conus elasticus. The ventral border is the Lig. cricothyroideum medianum (Lig. conicum), and the cricoid cartilage is the dorsal demarcation.

Inner relief of the larynx

Fig. 11.44 Larynx, Larynx; midsagittal section.

The paired vocal fold (Plica vocalis) locates below the paired vestibular fold (Plica vestibularis) in the middle laryngeal compartment. The largest part of the laryngeal cavity (Cavitas laryngis) is lined by respiratory epithelium. Non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium is commonly present in some areas of the Larynx, while in other areas this type of surface epithelium is only observed occasionally with large interindividual variations. Non-keratinised stratified squamous epithelium is commonly localised to the vocal folds covering the Lig. vocale. This epithelium spreads along the mucosal lining of the arytenoid cartilages and seamlessly transitions into the stratified squamous Epithelium of the Hypopharynx. Squamous epithelium covers the lingual area of the epiglottis. The distribution of respiratory and squamous epithelium on the Plicae vestibulares and in the entire laryngeal cavity is subject to significant variations specific to each individual. With increasing age, laryngeal areas covered with squamous epithelium increase.

Fig. 11.45 Larynx, Larynx, position of the Epiglottis during swallowing; midsagittal section.

Swallowing involves a change in the position of the structures of the laryngeal orifice. The Epiglottis is pushed downward. The pre-epiglottic fat body moves dorsally, the Aditus laryngis becomes narrow.

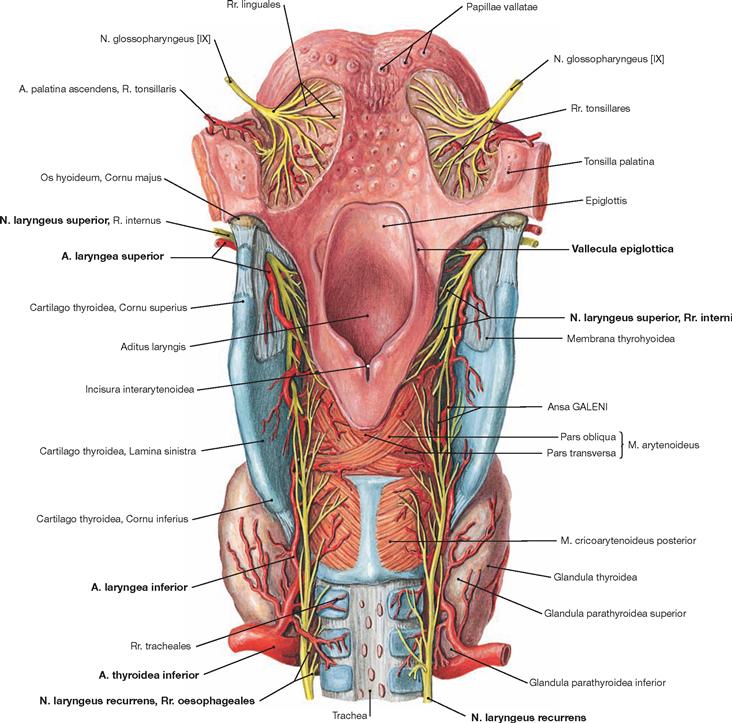

Arteries and nerves of the larynx

Fig. 11.46 Arteries and nerves of the larynx, Larynx, and root of the tongue, Radix linguae; dorsal view.

The A. laryngea superior branches off the A. thyroidea superior, perforates the Membrana thyrohyoidea below the Cornu majus of the hyoid bone, and divides into smaller branches within the mucosa of the Recessus piriformis. Here, the A. laryngea superior has multiple anastomoses and collaterals with the A. laryngea inferior.

The Larynx receives bilateral innervation through two branches of the N. vagus [X]:

• The N. laryngeus superior divides into a R. internus and a R. externus (→ Fig. 11.81). The R. internus projects lateral in the wall of the Pharynx and, jointly with the A. laryngea superior, passes through the Membrana thyrohyoidea into the Larynx where it provides sensory innervation for the supraglottic mucosa, the mucosa of the Valleculae epiglotticae, and the Epiglottis. Sensory innervation of the laryngeal mucosa is very dense (cough reflex). Apart from its motor and sensory fibres, the N. laryngeus superior also contains many parasympathetic fibres for the innervation of glands.

• The N. laryngeus recurrens (inferior) provides motor innervation for the inner laryngeal muscles. The innervation of the paired M. cricoarytenoideus posterior and M. arytenoideus on the posterior side of the Larynx is shown. The connection between the N. laryngeus superior and the N. laryngeus inferior is called Ansa GALENI (GALEN’s anastomosis). For demonstration of the course of the Nn. laryngei recurrentes → Figures 11.21 and 11.56.

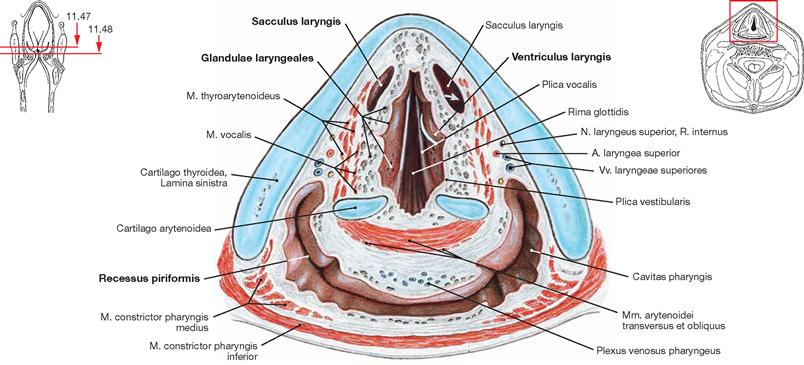

Larynx, transverse sections

Fig. 11.47 Larynx, Larynx; transverse section at the level of the vestibular folds.

The vestibular folds (Plicae vestibulares) contain multiple seromucous glands (Glandulae laryngeales) which serve to moisten the vocal folds. The white arrow indicates the connection between the laryngeal ventricle and the laryngeal saccule. Posterior to the Larynx, the laryngopharynx with the Recessus piriformis are visible.

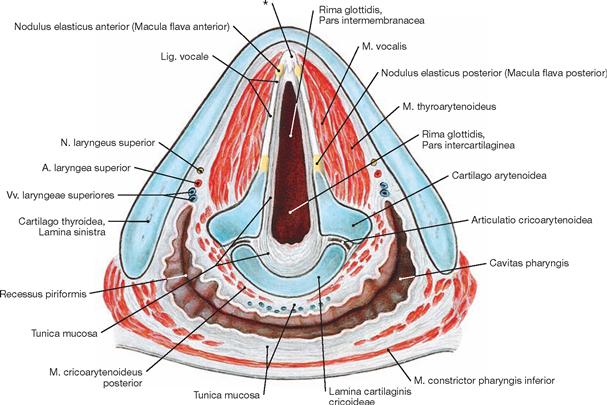

Fig. 11.48 Larynx, Larynx; transverse section at the level of the vocal folds, Plicae vocales.

The section at the level of the true opening of the vocal ligaments (Glottis, Rima glottidis) displays the mucosa (Tunica mucosa) of the vocal ligaments. The following structures are arranged from the inside to the outside of the Glottis: the vocal ligament (Lig. vocale), the M. vocalis (Pars interna of the M. thyroarytenoideus), and the Pars externa of the M. thyroarytenoideus. The cartilage-free part of the vocal fold is the Pars intermembranacea, the part between the two arytenoid cartilages is the Pars intercartilaginea (→ Fig. 11.43). In the front, the vocal folds converge on the thyroid cartilage. The insertion site is described as the anterior commissure. Here, the vocal folds insert via Noduli elastici anteriores and the tendon of the vocal ligament (BROYLE’s tendon*) at the thyroid cartilage. Dorsally the Lig. vocale attaches at the Proc. vocalis of the arytenoid cartilage via the Nodulus elasticus posterior.

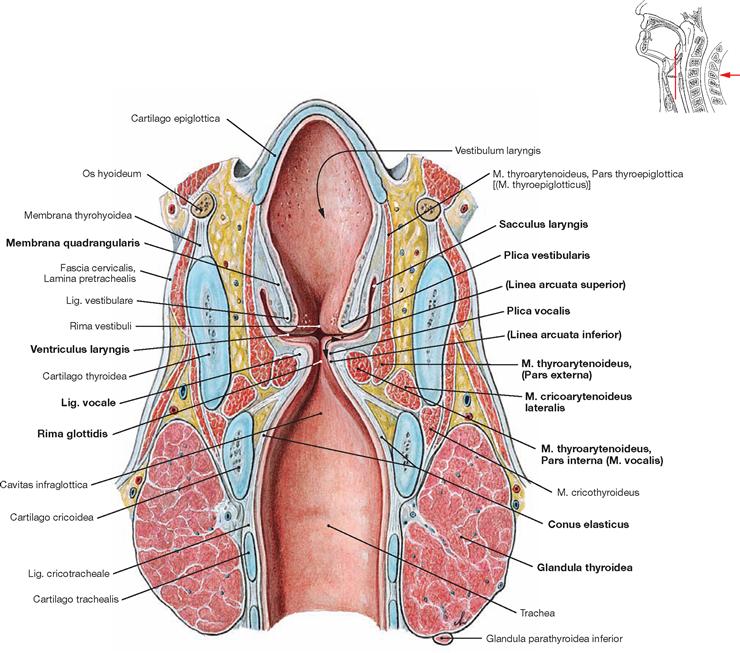

Larynx, frontal section

Fig. 11.49 Larynx, Larynx, and thyroid gland, Glandula thyroidea; frontal section.

Normally, the vocal folds (Plicae vocales) extend beyond the vestibular folds (Plicae vestibulares) and protrude more into the lumen of the Larynx, which makes them accessible for inspection by laryngoscopy. The vocal folds are composed of an outer mucosa, the Lig. vocale, followed caudally by the Conus elasticus, and the M. vocalis (Pars interna of the M. thyroarytenoideus), and the Pars externa of the M. thyroarytenoideus. Located at both sides is the M. cricoarytenoideus lateralis. Both vocal folds demarcate the opening of the vocal ligaments (Glottis, Rima glottidis) which represents the part of the Larynx responsible for phonation.

The Lig. vocale is lined by a loose subepithelial connective tissue layer between the Linea arcuata superior and Linea arcuata inferior which provides a flexible potential space (REINKE’s space, arrow). The Ventriculus laryngis extends in between the vocal and vestibular folds. The elastic Membrana quadrangularis forms the connective tissue framework for the laryngeal ventricle. The thyroid gland with its two lobes is located between the cricoid cartilage and the upper tracheal semicircular cartilages.

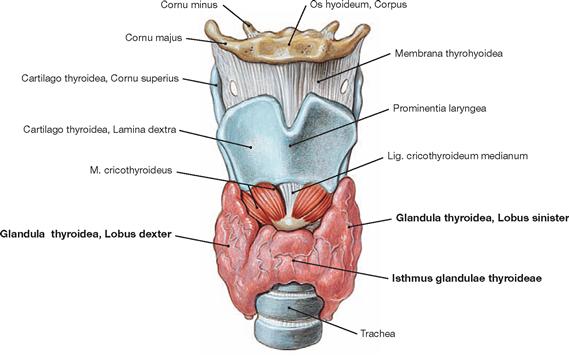

Thyroid gland

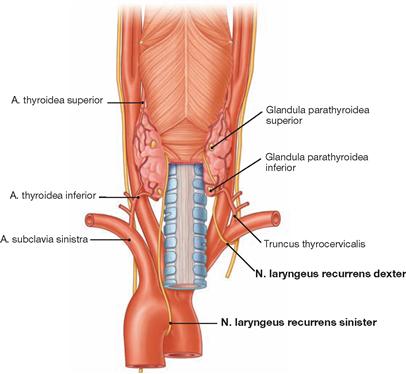

Fig. 11.50 Position of the thyroid gland, Glandula thyroidea; ventral view.

The thyroid gland (weight in an adult 20–25 g) is located below the Larynx. The Glandula thyroidea surrounds the upper part of the Trachea with bilateral lobes (Lobus dexter and Lobus sinister) and an anterior isthmus.

Fig. 11.51 Thyroid gland, Glandula thyroidea; horizontal section.

The thyroid gland covers the upper tracheal part from lateral and ven- tral. It is the largest endocrine gland in the body and secretes the hormones thyroxine (tetraiodothyronine, T4), triiodothyronine (T3), and calcitonin. The gland is ensheathed in its own capsule and, together with the Larynx, Trachea, Oesophagus, and Pharynx, is surrounded by the general organ fascia.

Placed at the posterior side of each glandular lobe there are two grain-sized epithelial bodies (parathyroid glands, Glandulae parathyroideae) weighing 12–50 mg, which produce the parathyroid hormone (PTH).

On both sides, the N. laryngeus recurrens courses between the Trachea and the Oesophagus. The nerve is located outside of the special organ fasciae but inside the general organ fascia.

Thyroid gland

Development of the thyroid gland

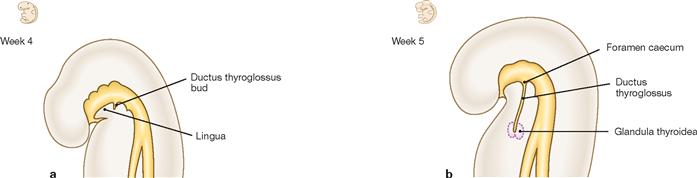

Fig. 11.52 a and b Development of the thyroid gland. [21]

From day 24 after fertilisation onwards, epithelium from the ektodermal stomodaeum grows caudally past the hyoid bone and the Larynx to form the Ductus thyroglossus (a). When the Ductus thyroglossus has reached its final location at the thyroid cartilage of the Larynx at week 7, it forms the isthmus and the two lobes of the thyroid gland (b). The cranial part of the Ductus thyroglossus regresses. The proximal opening of the Ductus thyroglossus persists as Foramen caecum behind the Sulcus terminalis and frequently a Lobus pyramidalis (thyroid gland tissue) is found along the passageway of the primitive Ductus thyroglossus (→ Fig. 8.162). Protruding from the fifth pharyngeal pouch, the ultimobranchial body gives rise to C-cells (produce calcitonin) which migrate into the thyroid gland. The epithelial bodies (produce parathyroid hormone) derive from the third and fourth pharyngeal pouches.

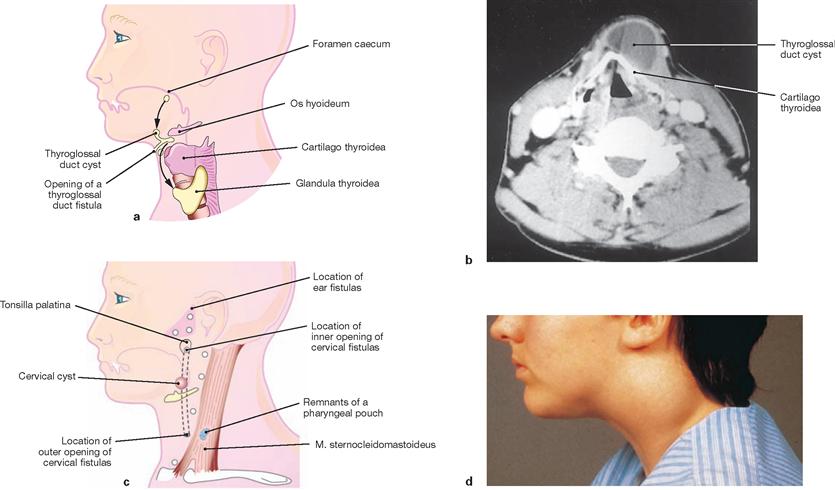

Fig. 11.53 a to d Cervical cysts and cervical fistulas. [20]

a. possible locations of cysts derived from the Ductus thyroglossus (arrows show the location of the Ductus thyroglossus during the descent of the thyroid gland from the Foramen caecum to the final position in the anterior cervical region)

b. computed tomography of a thyroglossal duct cyst in front of the thyroid cartilage

c. possible locations of cervical cysts and cervical fistulas

d. lateral cervical cyst; notice the swelling on the lateral side of the neck.

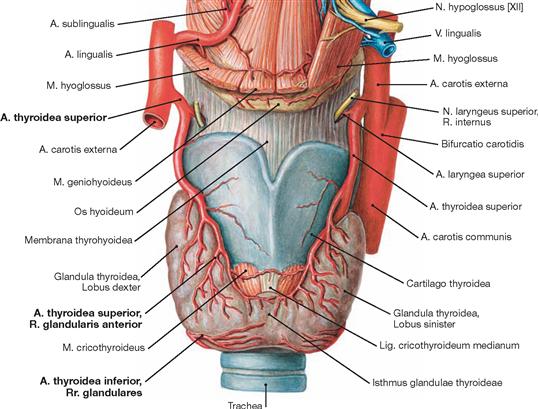

Vessels and nerves of the thyroid gland

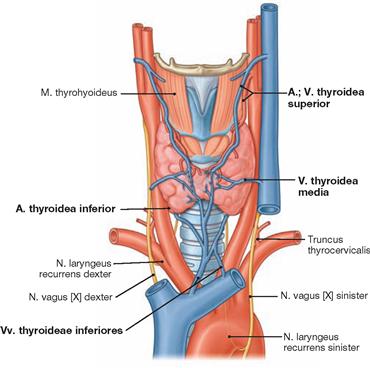

Fig. 11.54 Arteries of the thyroid gland, Glandula thyroidea; ventral view.

Being an endocrine organ, the thyroid gland has an exquisite blood supply through the A. thyroidea superior (with Rr. glandulares anterior and posterior) from the A. carotis externa as well as through the A. thyroidea inferior from the Truncus thyrocervicalis. Sometimes, a small A. thyroidea ima from the Truncus brachiocephalicus or the Arcus aortae also contributes to the blood supply (not shown). The blood vessels also supply blood to the epithelial bodies (→ Fig. 11.56).

Fig. 11.55 Veins of the thyroid gland, Glandula thyroidea; ventral view. [8]

Three paired veins collect the blood of the thyroid gland. The Vv. thyroideae superior and media drain into the V. jugularis interna, whereas the V. thyroidea inferior leads the blood into the left V. brachiocephalica.

Fig. 11.56 Aa. thyroideae superior and inferior as well as Nn. laryngei recurrentes sinister and dexter; dorsal view. [8]

The thyroid gland has a close topographic relationship with the Nn. laryngei recurrentes (Nn. laryngei inferiores). In the grove between the Trachea and the Oesophagus these nerves course cranially to the Larynx (→ Fig. 11.46).

Imaging and clinics

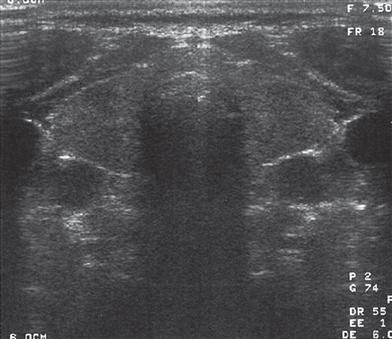

Fig. 11.57 Thyroid gland, Glandula thyroidea; ultrasound image, normal thyroid, transverse section at the level of the isthmus of the thyroid gland. [27]

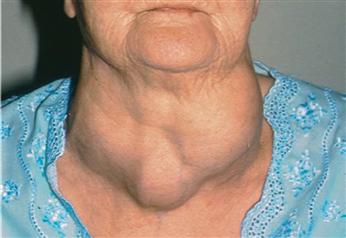

Fig. 11.58 Enlargement of the thyroid gland (Struma multinodosa).

Three large nodes are visible (multinodular goitre).

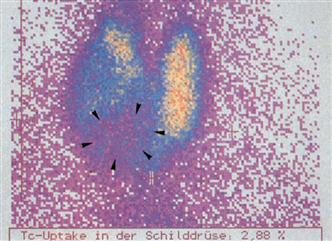

Fig. 11.59 Thyroid gland, Glandula thyroidea; scintigraphic scan, ventral view. [6]

Scintigraphy is a diagnostic procedure which provides topographic and functional information of the thyroid gland. This image was taken 20 minutes after intravenous injection of technetium-99m-pertechnetate and shows a “cold nodule” (arrowheads) in the right thyroid lobe extending into the isthmus. The left thyroid lobe displays a homogeneous distribution of nuclides. The “cold node” represents functionally inactive thyroid tissue.

Fig. 11.60 Patient with endocrine ophthalmopathy: exophthalmus and retraction of the upper eyelid due to hyperthyroidism. [5]

Topography

Vessels and nerves of the neck

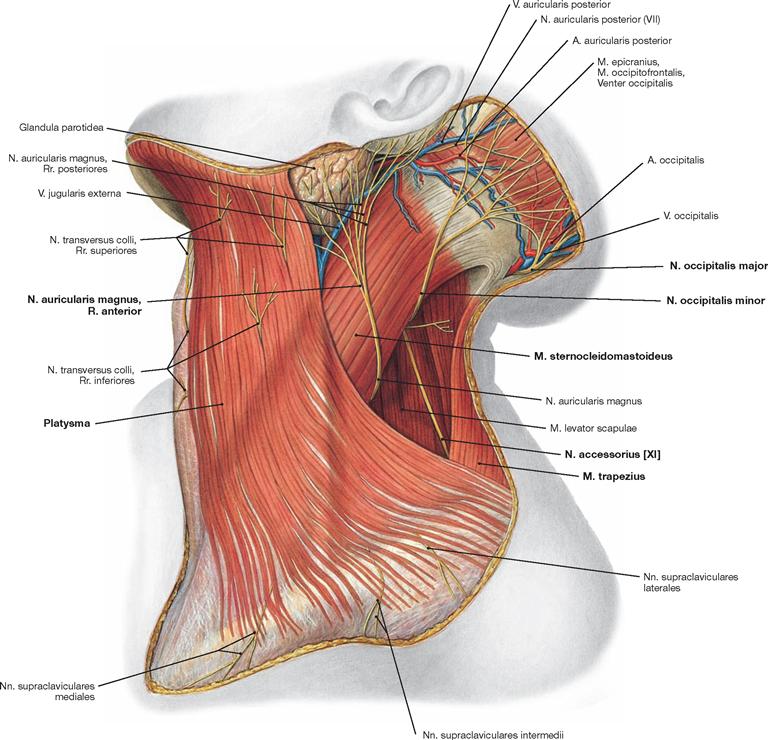

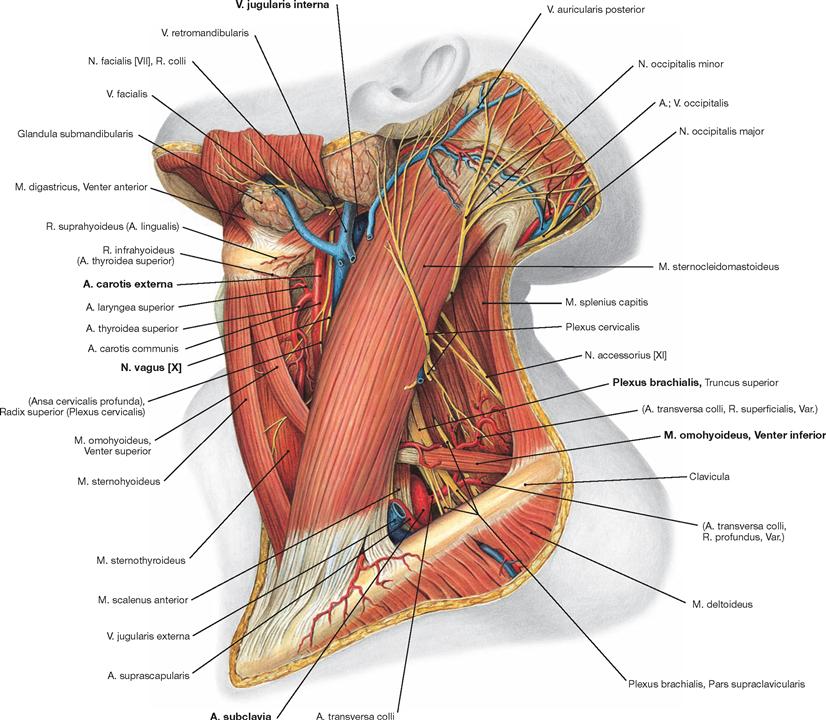

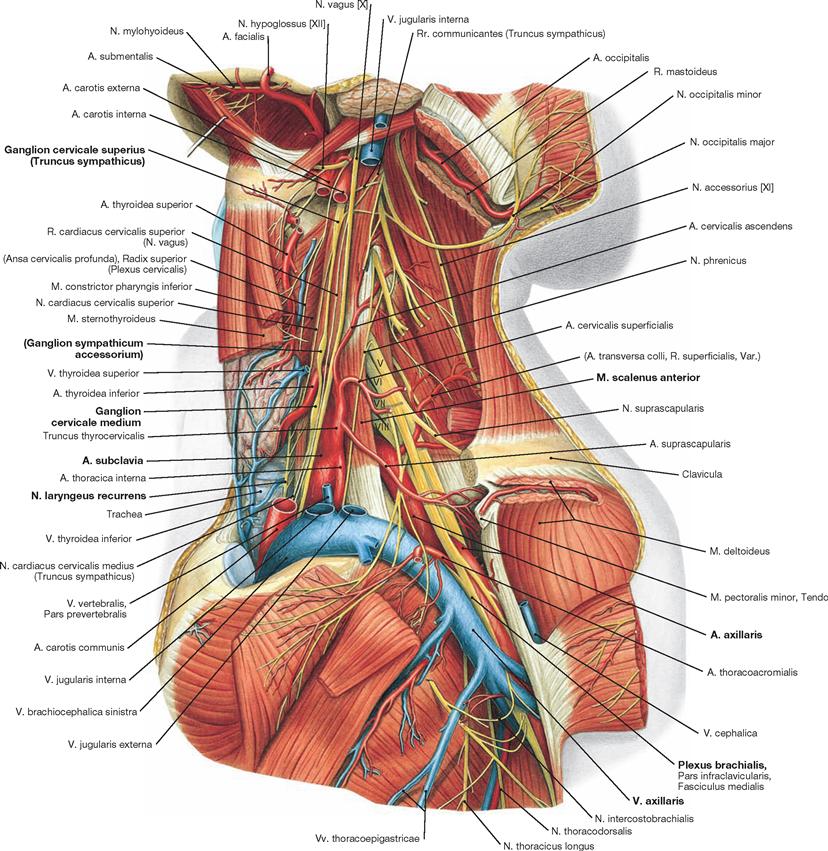

Fig. 11.61 Vessels and nerves of the anterior and lateral cervical regions, Regiones cervicales anterior et lateralis; lateral view.

The superficial fascia of the neck has been removed dorsally of the Platysma. The N. auricularis magnus and the N. occipitalis minor come from behind the M. sternocleidomastoideus and curve around this muscle in an anterior and superior direction. Both are sensory nerves derived from the Plexus cervicalis (C1–C4) and innervate the skin in front of and below the auricle to the occiput region. The N. occipitalis major passes through the tendinous origin of the M. trapezius at the Linea nuchae superior and provides the sensory cutaneous innervation to the occipital region. It is the R. dorsalis of the spinal nerve C2. The N. accessorius [XI] lies on top of the M. levator scapulae and courses through the lateral triangle of the neck from the M. sternocleidomastoideus to the M. trapezius, the two muscles innervated by this nerve. The N. accessorius [XI] has its origin in the brain stem and the upper cervical spinal cord (→ Fig. 12.160).

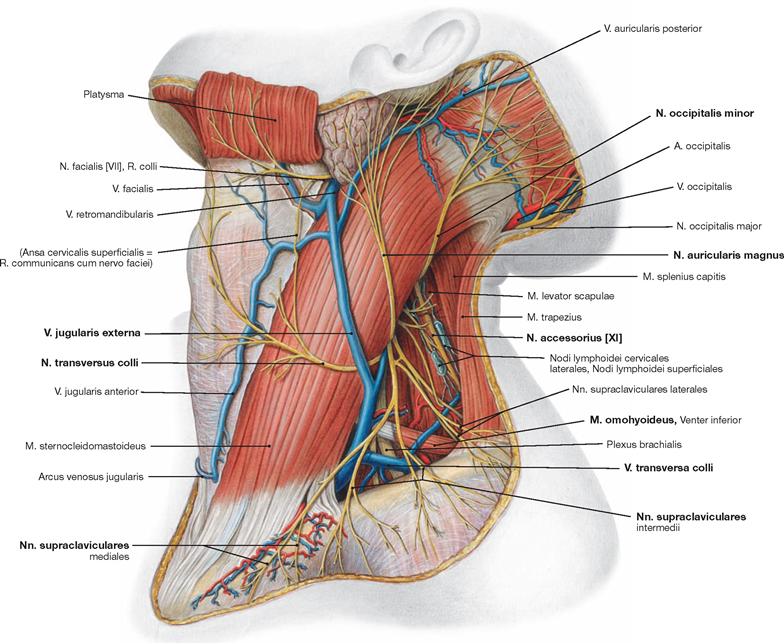

Fig. 11.62 Blood vessels and nerves of the lateral cervical region, Regio cervicalis lateralis, left side; lateral view. Parts of the platysma were deflected upwards, and the Lamina superficialis of the Fascia cervicalis was largely removed.

The sensory nerves of the Plexus cervicalis emerge at the posterior margin of the M. sternocleidomastoideus and penetrate the superficial fascia of the neck. The Nn. supraclaviculares, N. transversus colli, and N. auricularis magnus all emerge in a confined area, called Punctum nervosum (ERB’s point), midway of the M. sternocleidomastoideus. The Punctum nervosum also includes the N. occipitalis minor although it exits far more cranially. The N. accessorius [XI], the M. omohyoideus, and the V. transversa colli are visible in the posterior triangle of the neck. The V. transversa colli drains into the V. jugularis externa, which has a variable course across the M. sternocleidomastoideus.

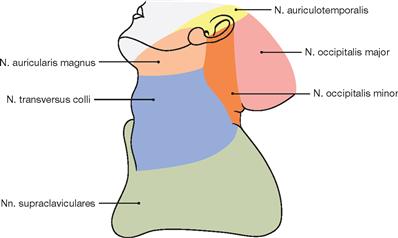

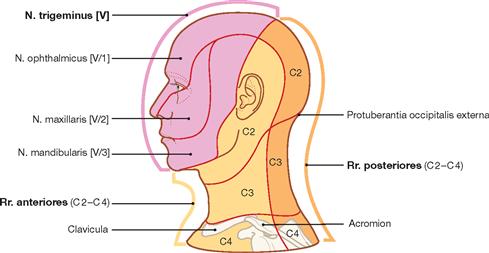

Fig. 11.63 Sensory innervation of the skin in the cervical region (cutaneous nerves).

The sensory innervation of the skin is provided by the Nn. supraclaviculares, transversus colli, auricularis magnus, occipitalis minor, occipitalis major and occipitalis tertius (not shown).

Fig. 11.64 Sensory innervation of the skin in the head and neck region as well as segmental mapping of the cutaneous areas [8]

The cervical segments C2, C3, and C4 provide the innervation to the skin in the neck region. The Rr. anteriores of the spinal nerves innervate the ventral area of the neck, while the Rr. posteriores provide the sensory innervation to the dorsal part of the neck.

Fig. 11.65 Vessels and nerves of the anterior and lateral cervical regions, Regiones cervicales anterior et lateralis, left side; lateral view; after removal of the superficial and middle fascia of the neck.

The anterior triangle of the neck depicts structures normally covered by the carotid sheath (A. carotis externa, N. vagus [X], V. jugularis interna); displayed in the posterior triangle of the neck are the Plexus brachialis and the A. subclavia in the scalene hiatus, which are crossed by the Venter inferior of the M. omohyoideus.

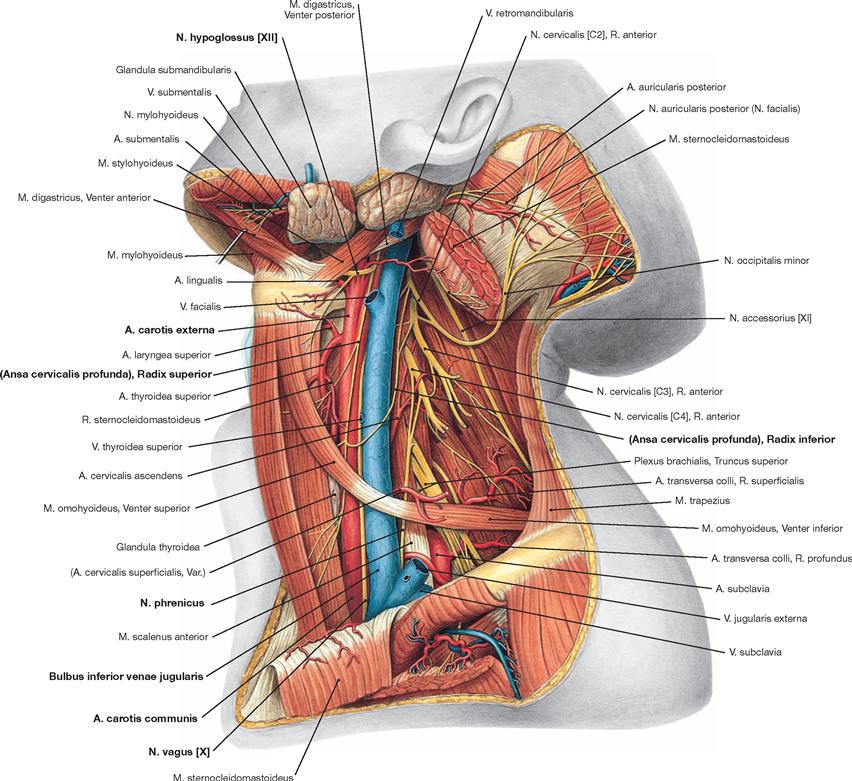

Fig. 11.66 Vessels and nerves of the lateral cervical region, Regio cervicalis lateralis, left side; lateral view; after almost complete removal of the M. sternocleidomastoideus.

The removal of the M. sternocleidomastoideus permits an unobstructed view of the A. carotis communis in the lower neck region, the A. carotis externa in the upper cervical region as well as the N. vagus [X] and the V. jugularis interna. In the upper cervical region, the Ansa cervicalis (profunda) with its Radices superior and inferior encloses the V. jugularis interna. The Radices superior and inferior provide branches to the infrahyoid muscles. Lateral to the V. jugularis interna, the N. phrenicus branches off the Plexus cervicalis and crosses the M. scalenus anterior in the lower cervical region to reach the upper thoracic aperture. In the upper cervical region, the N. hypoglossus [XII] projects forward and crosses the A. carotis externa close to the branching points of the A. lingualis and the A. facialis to disappear below the M. stylohyoideus.

Fig. 11.67 Vessels and nerves of the lateral cervical region, Regio cervicalis lateralis, deep layer, left side; lateral view.

Upon removal of the V. jugularis interna, the medially located A. subclavia, the A. vertebralis and the Truncus thyrocervicalis branching off the A. subclavia are visible. The A. subclavia courses dorsal to the M. scalenus anterior and, together with the Plexus brachialis, passes through the scalene hiatus

Vessels and nerves of neck and axilla

Fig. 11.68 Vessels and nerves of the lateral cervical region, Regio cervicalis lateralis, and the axillary region, Regio axillaris.

The numbers V to VIII mark the ventral branches of the corresponding cervical nerves.

After the removal of the anterior two-thirds of the clavicle, the Plexus brachialis and the A. subclavia passing through the scalene hiatus (between M. scalenus anterior and M. scalenus medius), and the course of the V. subclavia (in front of the M. scalenus anterior) across rib I into the upper extremity are visible. In some cases, the upper part of the Plexus brachialis can penetrate the M. scalenus medius. In the cervical region, the Plexus brachialis provides a number of smaller branches and, after multiple exchanges of fibres, forms fascicles which are located shortly below the clavicle lateral of the A. subclavia. Only in the middle of the Axilla they reach the topographic position depicted in their name.

On top of the deep cervical muscles lies the sympathetic trunk (Truncus sympathicus) with the Ganglia cervicalia superius and medium (in the upper cervical region the sympathetic trunk runs within the general organ fascia, in the lower cervical region between the Fascia prevertebralis and the general organ fascia, not shown). The N. laryngeus recurrens is visible below the thyroid gland between the Trachea and the Oesophagus.

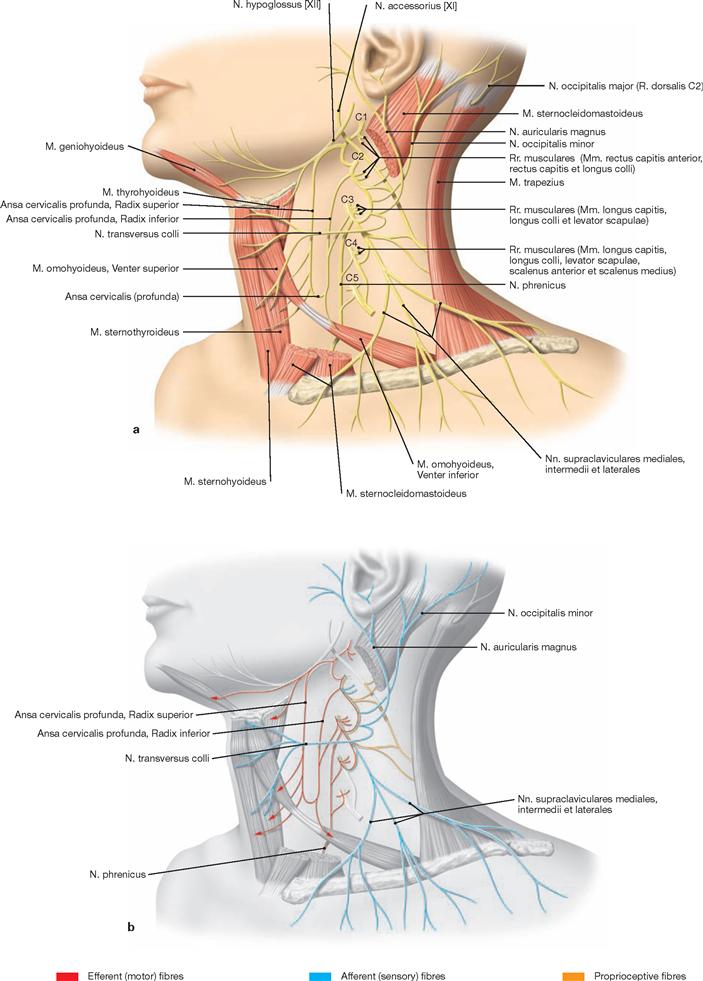

Plexus cervicalis

Fig. 11.69 a and b Plexus cervicalis, sensory and motor branches.

The Ansa cervicalis profunda and the N. phrenicus constitute the motor branches of the Plexus brachialis. The Ansa cervicalis profunda consisting of a Radix superior from segment C1 and a Radix inferior from segments C2 and C3 serves to innervate the infrahyoid muscles (Mm. thyrohyoideus, sternohyoideus, sternothyroideus, and omohyoideus). Additional motor branches innervate the suprahyoid M. geniohyoideus, the prevertebral muscles, the M. rectus capitis anterior, the Mm. sca- leni anterior and medius as well as parts of the M. levator scapulae. The N. phrenicus derives from the segments C3 to C5, runs caudally, and enters the thoracic cavity through the upper thoracic aperture.![]()

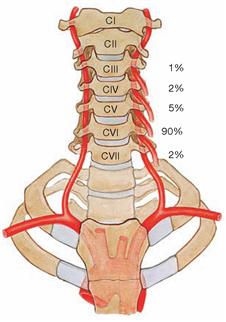

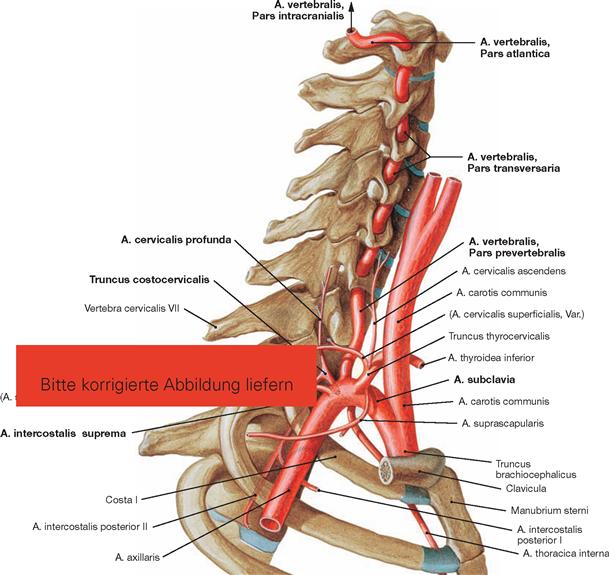

A. vertebralis and Truncus costocervicalis

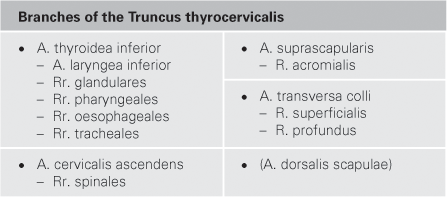

Fig. 11.70 Branches of the A. subclavia and A. vertebralis as well as Truncus costocervicalis; lateral view.

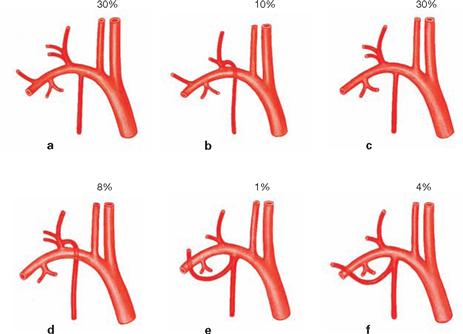

Fig. 11.71 a to f Variations in branching types of the A. subclavia and the Truncus thyrocervicalis.

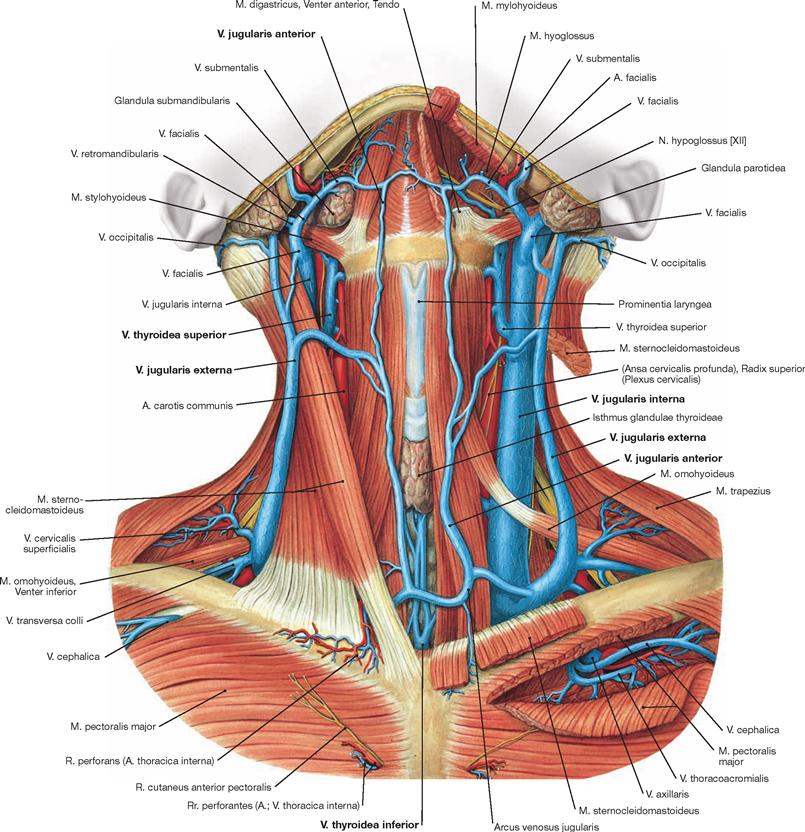

Veins of the neck

Fig. 11.73 Veins of the neck, Collum; ventral view.

The M. sternocleidomastoideus was largely removed on the left side. All fasciae of the neck have also been removed.

Superficial veins of the neck are the Vv. jugulares anteriores and the Vv. jugulares externae which drain venous blood into the Vv. jugulares internae, subclaviae, and brachiocephalicae.

Deep veins of the neck are the Vv. jugulares internae und thyroideae superiores, the V. thyroidea inferior and the Plexus thyroideus impar (not shown). The course of the superficial veins is very variable.

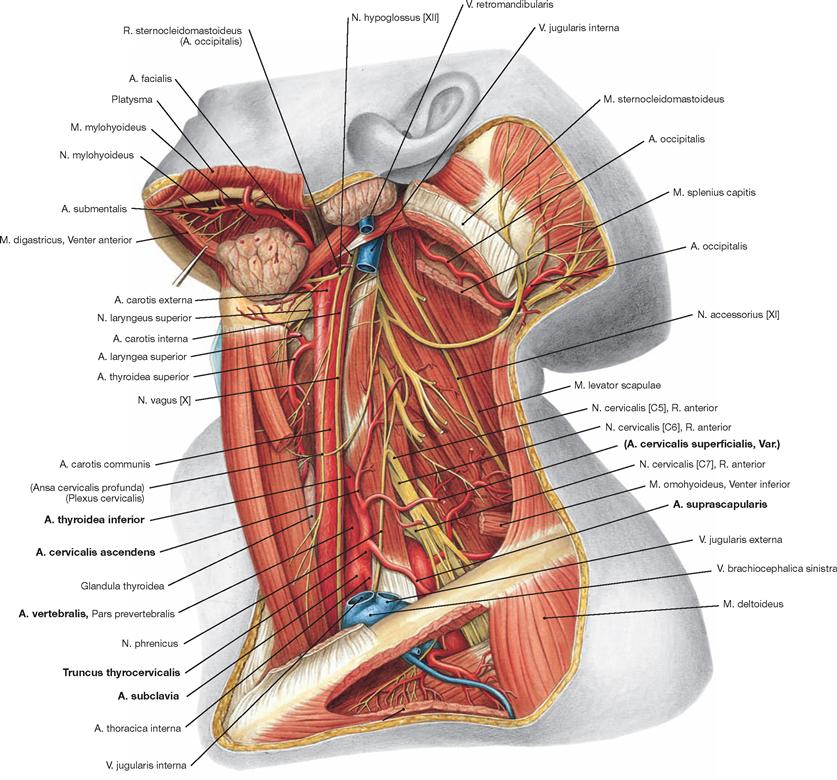

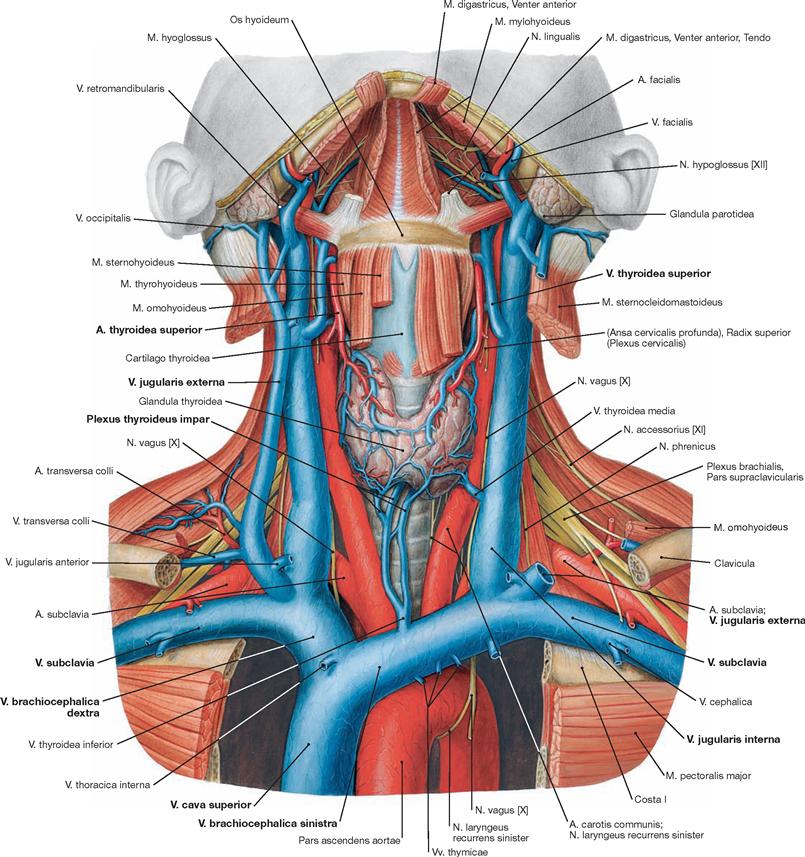

Vessels and nerves of the neck and upper thoracic aperture

Fig. 11.74 Vessels and nerves of the neck, Collum, and the upper thoracic aperture, Apertura thoracis superior; ventral view.

The sternum, parts of the clavicle, Mm. sternocleidomastoidei, and parts of the infrahyoid muscles were removed.

Presentation of the venous tributary of the V. cava superior (Vv. brachiocephalicae, jugulares internae, jugulares externae, and subclaviae) with particular emphasis on the venous drainage of the Glandula thyroidea (→ Fig. 11.55). Also visible are the Plexus brachialis as well as the A. and V. subclavia running between the clavicle and rib I, the course of the N. phrenicus across the M. scalenus anterior, and the left N. laryngeus recurrens curving around the aortic arch.

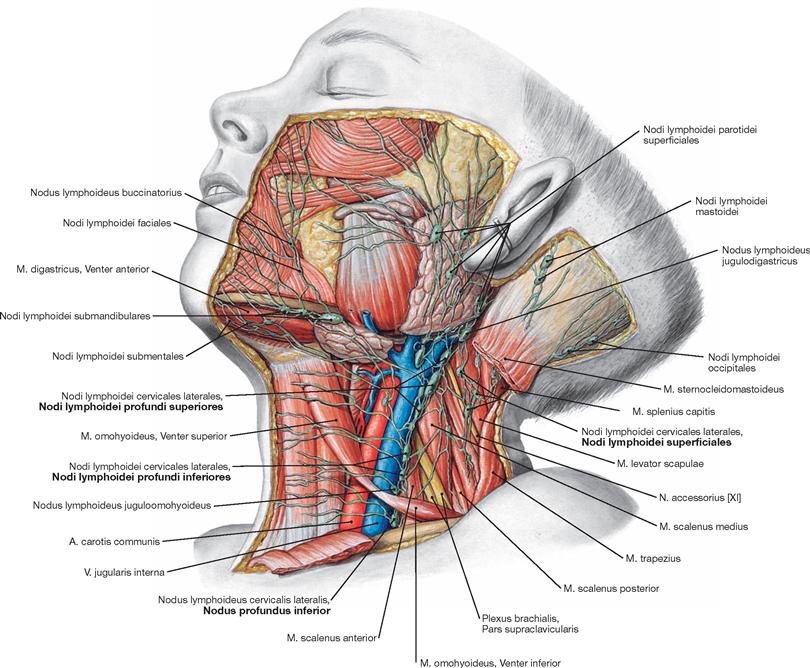

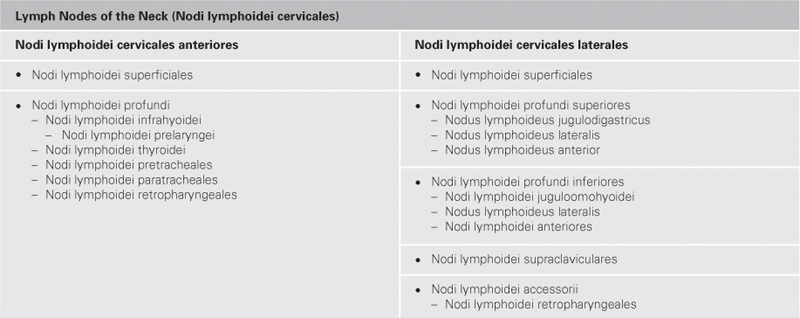

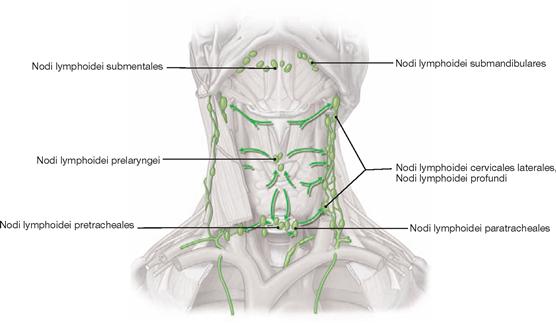

Lymph vessels and lymph nodes of the neck

Fig. 11.75 Superficial lymph vessels, Vasa lymphatica superficialia, and lymph nodes, Nodi lymphoidei, of the head and neck of a child.

The neck region contains 200 to 300 lymph nodes. The majority thereof assemble in groups along the neurovascular bundle (→ table,→ Fig. 8.85).

Lymphatic fluid of the right side of the head and neck drains into the Ductus lymphaticus dexter (→ Fig. 8.86), whereas the left side of the head and neck drains into the Ductus thoracicus. For entry of the Ductus thoracicus into the left venous angle → Figure 11.81.

Fig. 11.76 Classification of drainage regions of the head and neck into compartments; according to the classification of the American Joint Committee of Cancer (AJCC).

Fig. 11.77 Lymph vessels and lymph nodes of the larynx, Larynx, thyroid gland, Glandula thyroidea, and trachea, Trachea; ventral view. [10]

All three organs drain into the deep lymph nodes of the neck.

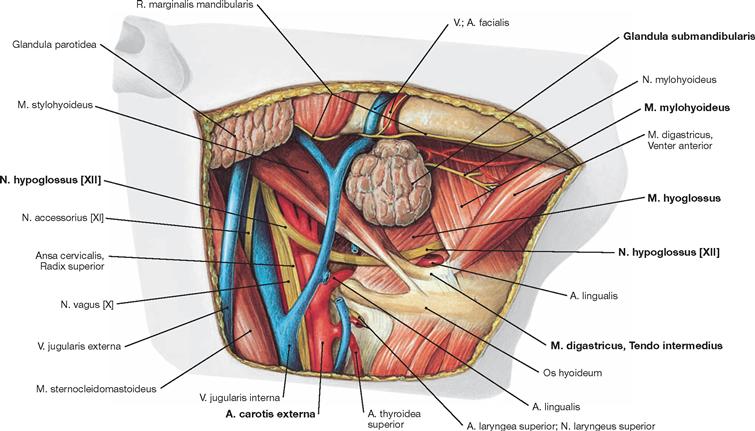

Vessels and nerves of the Trigonum submandibulare

Fig. 11.78 Vessels and nerves of the Trigonum submandibulare; inferolateral view.

Upon dissection of the submandibular gland (Glandula submandibularis) and the neurovascular bundle as well as after the removal of the fascial layers, the N. hypoglossus [XII] becomes visible. This cranial nerve separates from the neurovascular bundle in the parapharyngeal space, crosses the A. carotis externa and passes between the M. hyoglossus and the intermediate tendon of the M. digastricus until it disappears beneath the M. mylohyoideus.

Fig. 11.79 Vessels and nerves in the transition zone from the neck to the thorax and to the upper extremity.

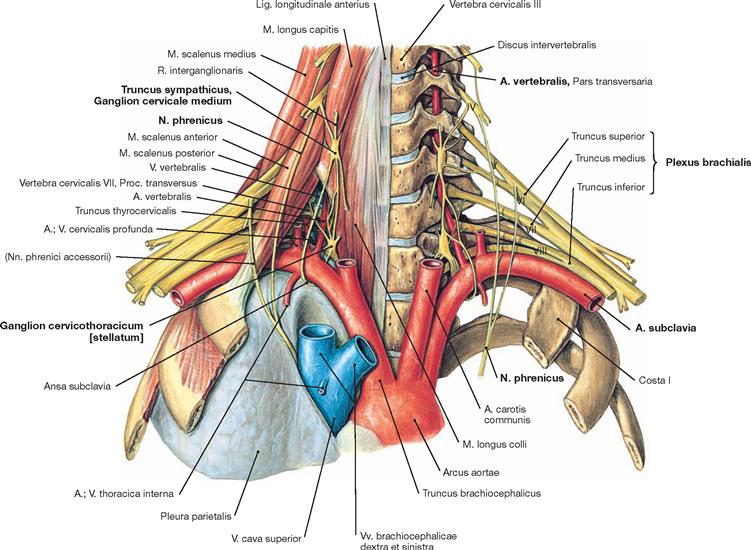

Visible are the pleural cupula, the scalene hiatus, the lower and middle sympathetic ganglia (Ganglion cervicale inferius/cervicothoracicum/ stellatum on top of the head of rib I and Ganglion cervicale medium on top of the M. longus colli), the course of the N. phrenicus, the course of the A. vertebralis, Trunci of the Plexus brachialis and the A. subclavia.

Numbers IV to VIII mark the ventral branches of the corresponding spinal nerves.

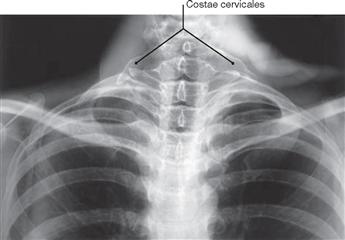

Fig. 11.80 Neck, Collum; radiograph in anteroposterior (AP) beam projection. [8]

Bilateral cervical ribs are visible (Costa cervicalis).

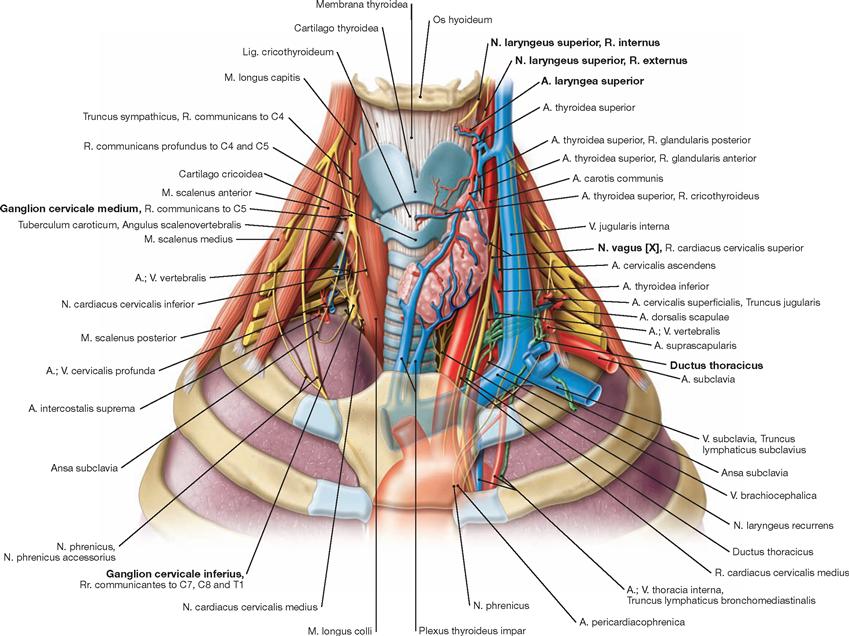

Pleural cupula and entry of the Ductus thoracicus

Fig. 11.81 Prevertebral and paravertebral structures of the neck and the upper thoracic aperture; ventral view.

On the right side of the body, the great blood vessels were removed to permit an unobstructed view onto the pleural cupula and the sympa- thetic trunk. The Ganglion cervicale inferius (Ganglion cervicothoracicum [stellatum]) rests on the head of rib I and Ganglion cervicale medium lies on top of the M. longus colli. The pleural cupula extends beyond the upper thoracic aperture. On the left side, the great blood vessels and the left thyroid lobe were left in place. Visible are the blood supply to the thyroid gland, the R. internus of the N. laryngeus superior and the Vasa laryngea superiora, the entry of the Ductus thoracicus into the left venous angle as well as the course of the N. vagus [X] between the A. carotis communis and the V. jugularis interna.