Head

The Head – Leading from the Top

The skeleton of the head (Caput/Cephalon), i.e. the skull (Cranium), consists of two parts: the facial bones (Viscerocranium) and the skull (Neurocranium). The border between the two – the roof of one and the floor of the other – is the base of the skull (Basis cranii), which lies roughly in an oblique plane defined by the eyebrows, the external opening of the outer ear canal and the base of the occiput.

Skull Cap (Calvaria) and Scalp

The highly arched Calvaria (skull cap, cranial cap) forms a longitudinal oval dome over the cranial base and protects the cranial cavity (Cavitas cranii), in which the brain (Cerebrum) surrounded by hard and soft meninges (Meninges) floats in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The Calvaria is divided in frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital regions formed by identically named bones (Os frontale, Os parietale, Os temporale and Os occipitale).

The skin of the Calvaria is tough (“scalp”) and firmly adherent to a flat tendon, which spans from the forehead to the occiput. This tendon (Galea aponeurotica) is part of the M. occipitofrontalis, a mimic muscle that raises eyebrows and wrinkles the skin of the forehead horizontally. Skin and tendon are movable on the skull cap and can be relatively easily lifted off and removed as the scalp. Vascular injuries of the scalp can lead to a severe but usually not-life threatening bleeding.

Skull Base

The base of the skull forms the roof of the two orbits (Orbitae) and the nasal cavity (Cavitas nasi), but also the roof of the throat (Pharynx, reaching up to the base of the skull) and the base of the occiput which articulates at the occipital foramen (Foramen magnum) with the first cervical vertebra. Numerous foramina, canals, and fissures cover the cranial base and serve as passageways for many nerves and blood vessels. At the bottom side of the skull base, pointing towards the Viscerocranium, numerous processes, spines, and notches (Processus/Spinae/Incisurae) are present, to which muscles and ligaments are attached. The upper side of the skull base, the floor of the Neurocranium, is less irregular and resembles terraces on three floors: the top floor, the anterior cranial fossa (Fossa cranii anterior), is positioned above the Orbitae. One step down, the middle cranial fossa (Fossa cranii media) is located at the level of the temporal bones. The last step leads down into the posterior cranial fossa (Fossa cranii posterior) with the Foramen magnum.

Facial Bones and Cavities

The largest facial bone, the maxillary bone (Maxilla), is placed in the centre of the Viscerocranium. The Maxilla forms the floor of the Orbitae, most of the sidewalls of the nasal cavity, the anterior part of the palate, and carries the maxillary row of teeth. Like many other bones of the skull, the maxilla is “pneumatised”, i.e. it is hollow and filled with air which is drawn from the nasal cavity (Sinus maxillaris, paranasal sinuses). Besides the Maxilla, half a dozen other smaller bones are involved in the construction of the Viscerocranium.

Breathing, smelling, tasting, chewing, swallowing, speaking, seeing, and being seen – these are the tasks of the organs that are supported and protected by the Viscerocranium.

The eyes and their auxiliary apparatus (Organum visus, → p. 98) are responsible for vision. Being seen is the responsibility of the facial muscles. The permanent activity of these muscles, which do not control bones but the facial skin, is responsible for the formation of wrinkles.

The olfactory sense is up to the nose (Nasus), even though it only performs it with its smallest part, the olfactory epithelium at the roof of the nasal cavity under the base of the skull. The outer cartilage-framed nasal vestibule (Vestibulum nasi) and the far more spacious, bony inner nasal cavity (Cavitas nasalis ossea) serve for breathing: Through the inner nostrils (Choanae), the nasal cavity opens behind the throat (Pharynx) which in turn communicates much more caudally with the Larynx and the windpipe (Trachea).

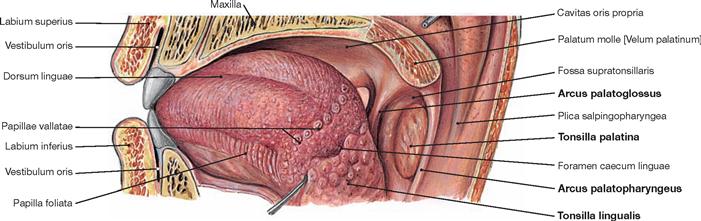

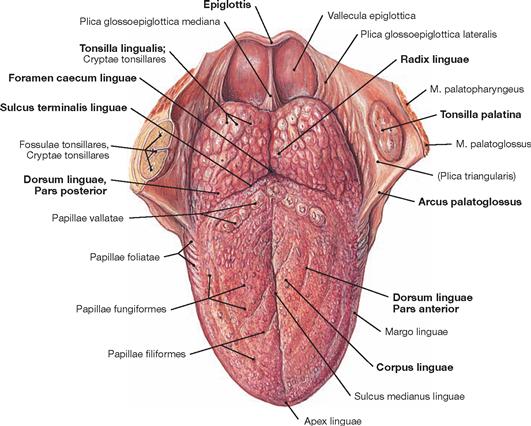

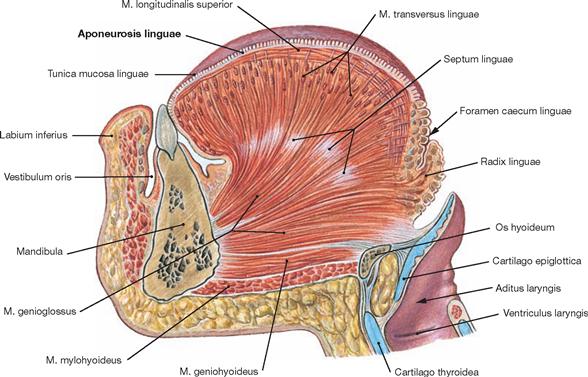

Biting, chewing, talking, tasting, and swallowing are the functions of the oral cavity (Cavitas oris) and the accompanying organs. Similar to the nose, the oral cavity also has a vestibule (Vestibulum oris), the space between lips (Labiae) and cheeks (Buccae) on one side and the teeth (Dentes) on the other side.

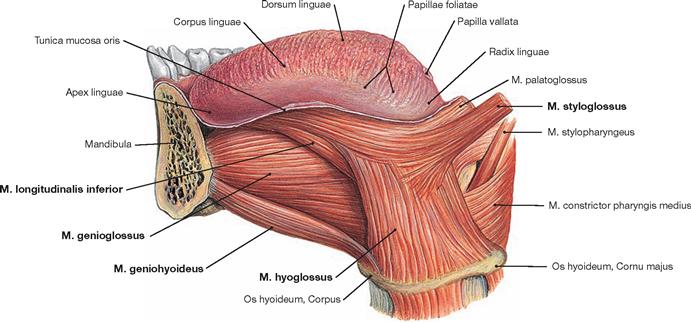

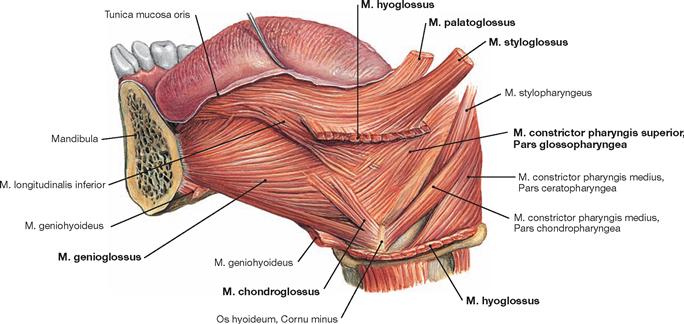

Behind the teeth lies the larger oral cavity proper (Cavitas oris propria) which is almost completely filled by the tongue (Lingua) at a closed bite. At its posterior aspect, the oral cavity opens towards the Pharynx and, at the price of choking, the respiratory tract and ingestive tract cross here. The roof of the mouth, the palate (Palatum), also forms the floor of the nasal cavity. In the front, the palate is rigid and bony, while dorsally towards the Pharynx it becomes soft, flexible, and muscular. The Uvula dangles from the soft part of the palate. The floor of the mouth, which is surrounded by the movable mandible (Mandibula) and which carries the tongue, is made of muscle plates. During speech almost all of these structures act together (along with many other structures), whereby the nose is used as an additional resonator.

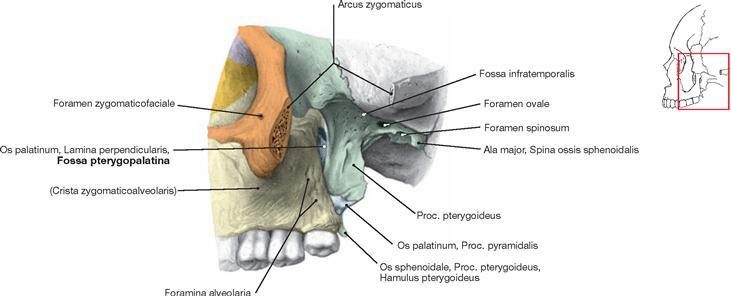

Two pits of the facial skeleton are important: If one removes (first imaginary, later on in reality during the dissection sessions) the ascending bony branch of the Mandibula (Ramus mandibulae), which leads to the temporomandibular joint (Articulatio temporomandibularis), one enters the soft tissues of the lateral aspect of the head from “behind the cheek” and enters a space that is referred to as the infratemporal fossa (Fossa infratemporalis). Positioned in this region are masticatory muscles (Mm. pterygoidei medialis and lateralis) and several branches of nerves. In addition, the terminal branches of the large external carotid artery lead towards the centre of the Viscerocranium.

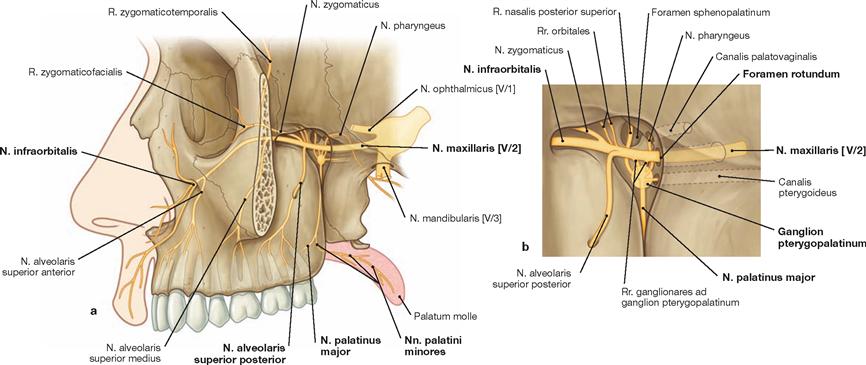

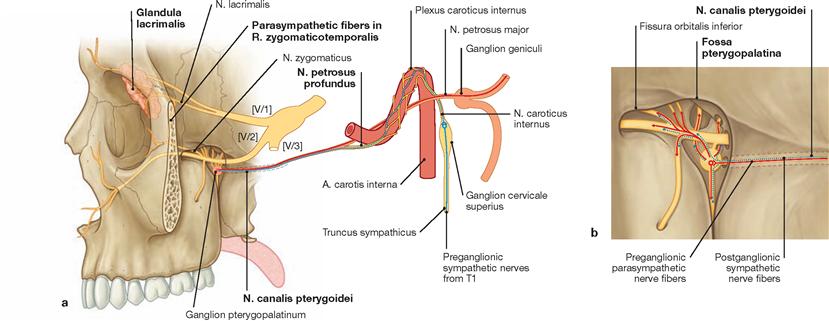

In the direction of the Orbita, the Fossa infratemporalis extends further inwards and cranially into a wider space, the pterygopalatine fossa (Fossa pterygopalatina). It is essential to locate this cavity during dissection and its contents and multiple pathways are important to remember. This cavity is a “key distributor” for vessels and nerves of the Viscerocranium. Since it is hidden and its anatomy is extremely complex, all anatomists adore it and like to examine students on it.

→ Dissection Link

The dissection of the superficial facial region at the lateral sagittal plane of the head (head in a lateral position) is showing the facial arteries and veins, muscles of facial expression, all branches of the N. facialis, and the peripheral branches of the N. trigeminus.

The dissection of the deep facial region includes the removal of the Glandula parotidea, the presentation of the Plexus parotideus (N. facialis [VII]), the dissection of the Fossa retromandibularis, the representation of all four masticatory muscles, and the demonstration of the course of the A. maxillaris up to its terminal branches, as well as the preparation of the temporomandibular joint with presentation of the Discus articularis and identification of the Chorda tympani.

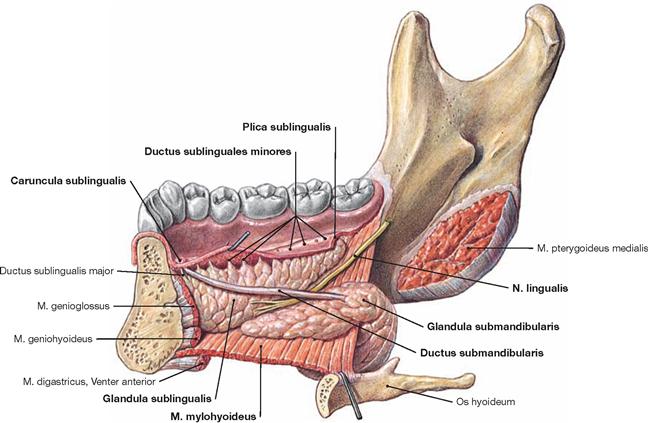

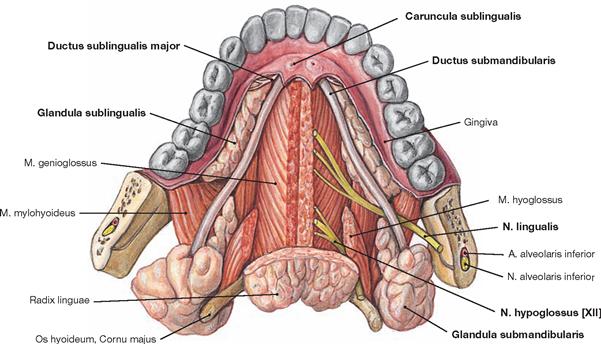

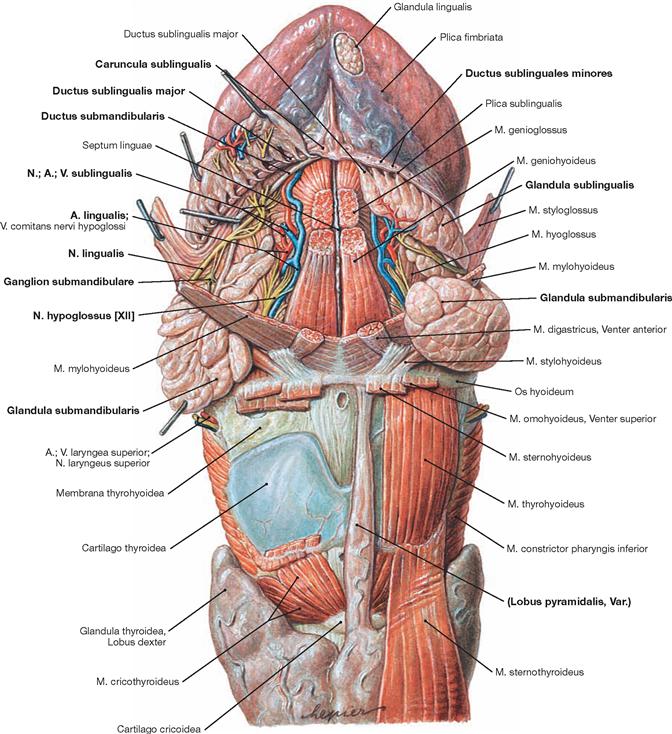

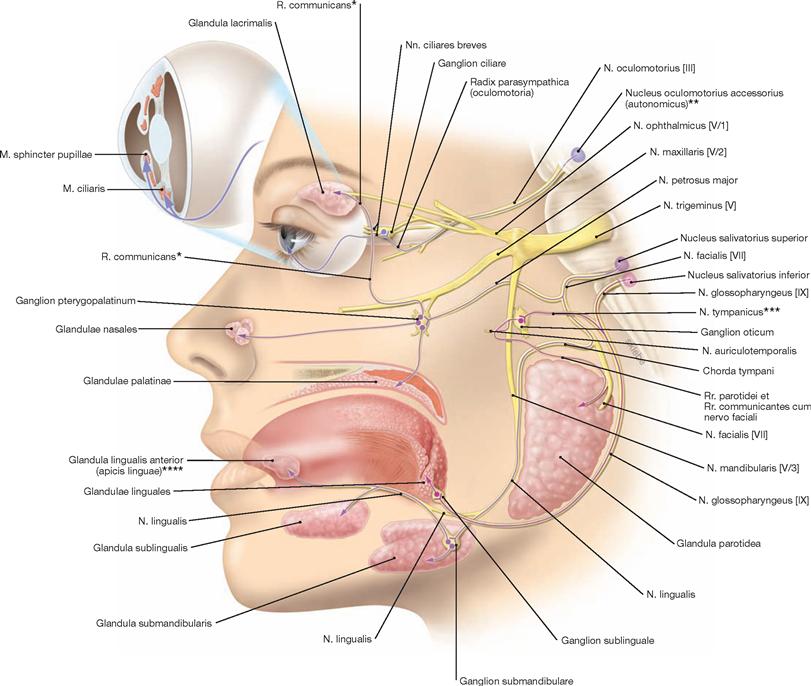

Dissection of the midsagittal planes of the head (head in medial position): The dissection of the nasal septum with its cartilaginous and bony parts as well as the Fila olfactoria and the N. nasopalatinus is followed by the removal of the nasal septum and the presentation of the lateral nasal wall with openings of the paranasal sinuses and the Ductus nasolacrimalis. The Fossa pterygopalatina is opened and its contents are displayed. Finally, the A. sphenopalatina at the Foramen sphenopalatinum is located, followed by the full dissection of the oral cavity with representation of the Glandulae submandibularis and sublingualis, Nn. lingualis, hypoglossus, and glossopharyngeus, as well as the dissection of the palatal muscles beneath the auditory tube cartilage, and of the tonsillar fossa.

Overview

Skeleton and joints

Skull

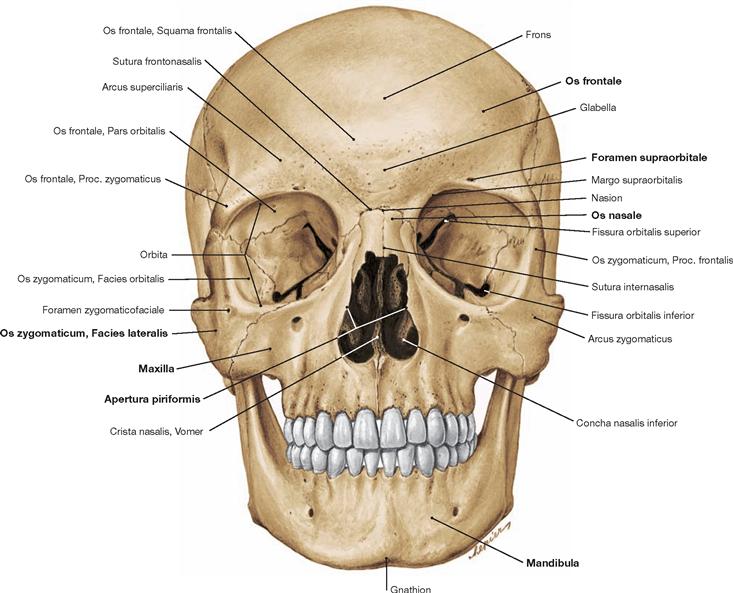

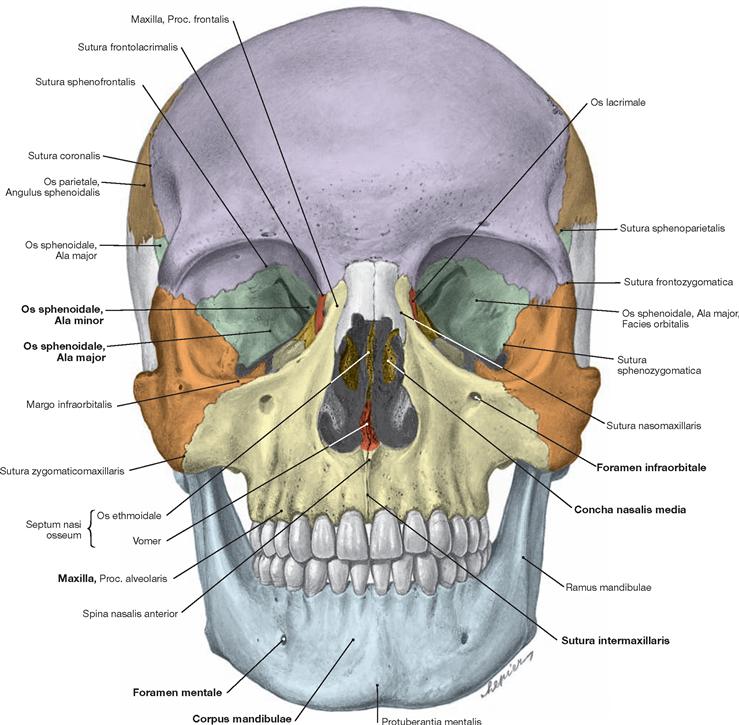

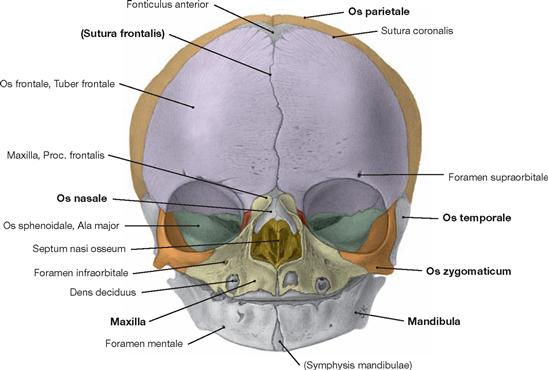

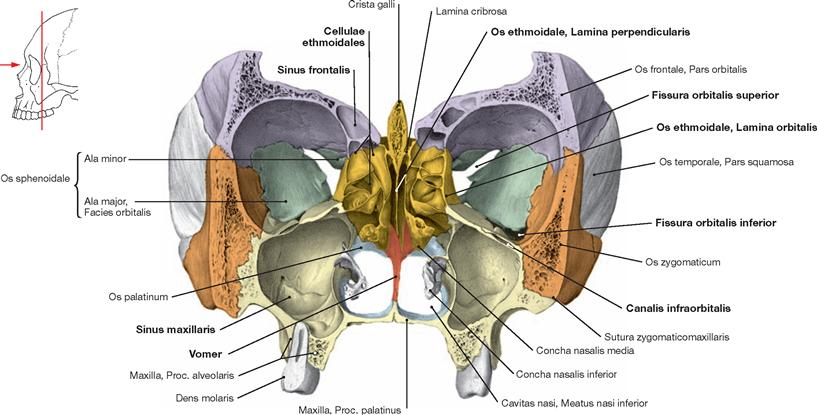

Fig. 8.3 Skull, Cranium; frontal view.

From bottom to top one can see the lower jaw or mandible (Mandibula), the two upper jaws or maxillary bones (Maxillae), the nasal bones (Ossa nasalia) located between the maxillary bone and the orbit (Orbita) as well as the frontal bone (Os frontale) above the orbit.

The frontal bone (Os frontale) consists of four parts (→ Fig. 8.23).

Above the upper margin of the orbit (Margo supraorbitalis) the bilateral Arcus superciliaris bulges out. A part of the Os frontale protrudes medially downwards and forms a portion of the medial margin of the orbit. At the lateral aspect, the Proc. zygomaticus has contact with the Proc. frontalis of the Os zygomaticum. Both form the lateral margin of the orbit.

The zygomatic bone (Os zygomaticum) constitutes the major part of the lateral and lower margins of the orbit.

The pair of nasal bones (Os nasale) is connected to the Os frontale by the Sutura frontonasalis and to each other by the Sutura internasalis.

Skull bones

Fig. 8.5 Skull bones, Ossa cranii; frontal view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The upper jaw or maxillary bone (Maxilla) is located between the orbit and the oral cavity. The maxilla participates in the formation of the lower and medial margins of the orbit and has a lateral border with the Os zygomaticum. The Proc. frontalis of the maxilla connects with the Os frontale. The Foramen infraorbitale is located below the lower margin of the orbit in the Corpus maxillae. The Spina nasalis anterior protrudes in the midline. The Proc. alveolaris creates the lower margin of the Maxilla and supports the teeth. In the orbit, the Maxilla creates the lower margin of the Fissura orbitalis inferior and, together with the Os zygomaticum, forms the lateral margin of the orbit.

The lower jaw or mandible (Mandibula) consists of a Corpus and Rami mandibulae, which merge in the Angulus mandibulae. The Corpus mandibulae is composed of the Pars alveolaris with teeth and the Basis mandibulae beneath. The latter protrudes in the midline as Protuberantia mentalis. In addition, the Foramen mentale is shown.

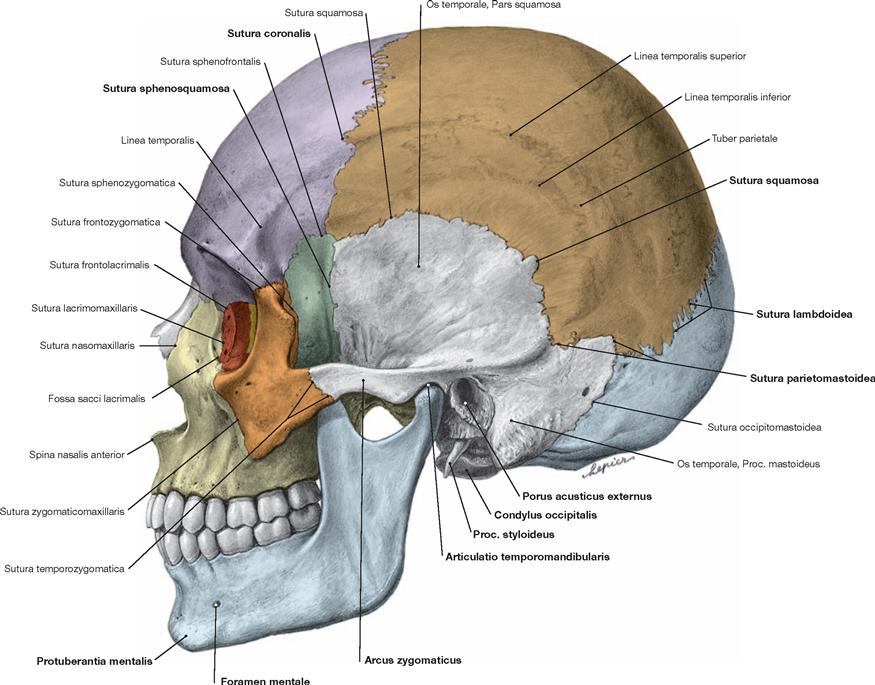

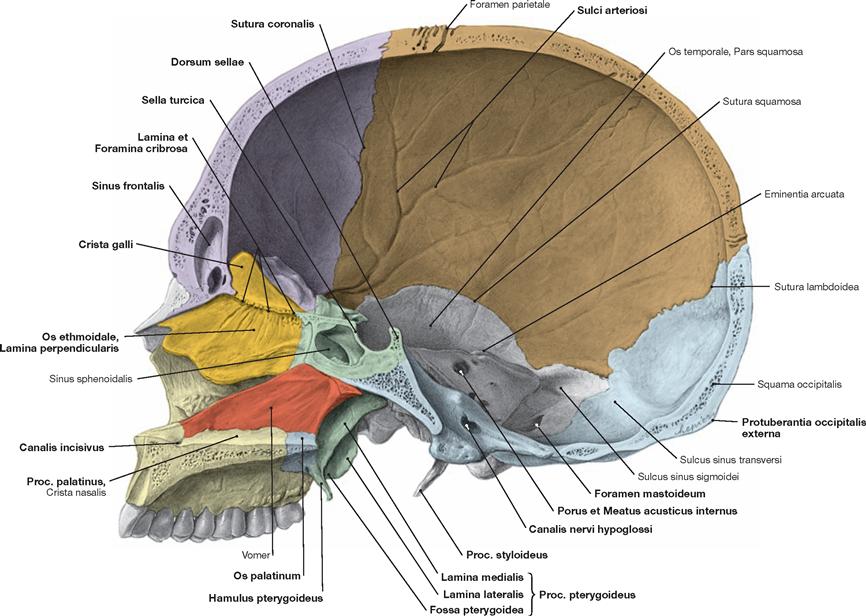

Fig. 8.6 Skull bones, Ossa cranii; lateral view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The lateral view displays parts of the Ossa frontale, parietale, occipitale, sphenoidale, and temporale, parts of the viscerocranium (Os nasale, Os lacrimale, Maxilla, and Os zygomaticum) as well as the lateral side of the lower jaw (Mandibula).

In the viscerocranium, the Os nasale has its cranial and posterior borders with the Os frontale and the Maxilla, respectively. The upper part of the lacrimal bone (Os lacrimale) forms the Fossa sacci lacrimalis between the Maxilla and the Os ethmoidale. The Proc. alveolaris of the Maxilla contains the upper teeth. The medial aspect of the Maxilla connects with the Os frontale, its lateral aspect contacts the Os zygomaticum. The Spina nasalis anterior protrudes in the anterior midline. The Os zygomaticum is responsible for the contour of the region of the cheek.

The head of the mandible (Caput mandibulae) articulates with the Os temporale in the temporomandibular joint (Articulatio temporomandibularis).

In its upper frontal aspect, the Os frontale is connected with the parietal bone (Os parietale) and the sphenoidal bone (Os sphenoidale) via the Sutura coronalis. The Os parietale connects with the occipital bone (Os occipitale) in the Sutura lambdoidea and with the Os sphenoidale in the Sutura shenoparietalis. The Os sphenoidale and the temporal bone (Os temporale) form the Sutura sphenosquamosa. Os temporale and Os occipitale connect in the posterior Sutura occipitomastoidea. The major part of the lateral wall of the skull is formed by the Pars squamosa of the Os temporale.

Os temporale and Os zygomaticum form the zygomatic arch (Arcus zygomaticus), which bridges the Fossa temporalis. The Pars tympanica of the Os temporale is located below the base of the Proc. zygomaticus and directly adjacent to the Pars squamosa. At its surface lies the Porus acusticus externus.

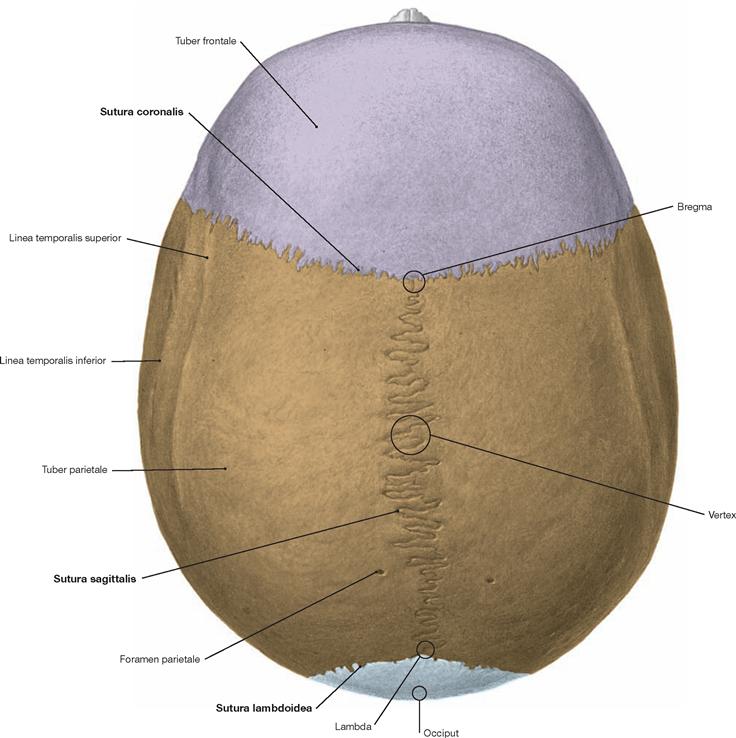

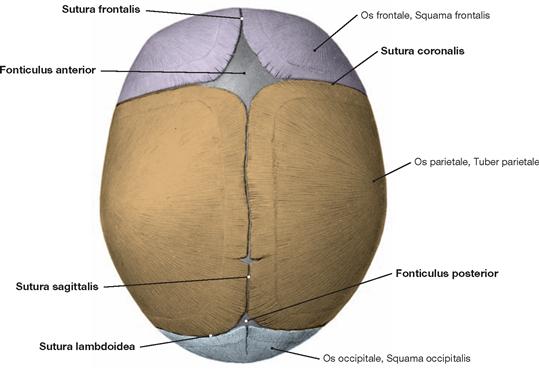

Fig. 8.8 Skull bones, Ossa cranii; superior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

A view on the upper part of the skull (skull cap, Calvaria) reveals the Os frontale, the Ossa parietalia, and the Os occipitale. Os frontale and Ossa parietalia are separated by the coronal suture (Sutura coronalis). Both Ossa parietalia meet at the sagittal suture (Sutura sagittalis). The Os occipitale connects with the two Ossa parietalia by the lambdoid suture (Sutura lambdoidea). The contact point between the Suturae coronalis and sagittalis is called Bregma, the contact point of the Suturae sagittalis and lambdoidea is named Lambda. In the dorsal part of the Ossa parietalia and bilaterally in close proximity to the Sutura sagittalis are the paired Foramina parietalia for the passage of the Vv. emissariae.

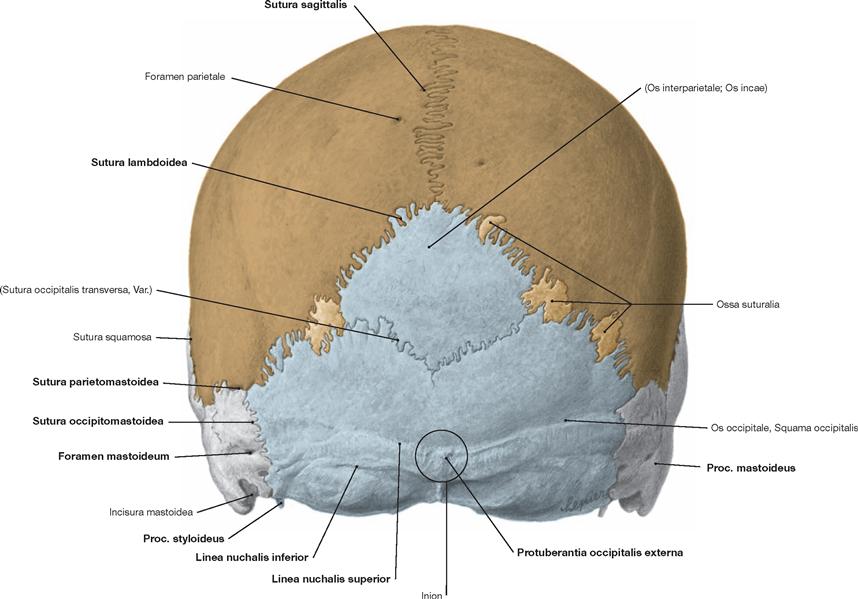

Fig. 8.9 Skull bones, Ossa cranii; posterior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

This view from the posterior side shows the Ossa temporalia, parietalia, and the Os occipitale. To both sides of the Os temporale the Proc. mastoideus is visible. At the lower medial margin of the Proc. mastoideus lies the Incisura mastoidea; this notch serves as attachment point for the Venter posterior of the M. digastricus.

Shown from posterior, both Ossa parietalia meet in the midline in the Sutura sagittalis, connect posteriorly with the Os occipitale in the Sutura lambdoidea, and are separated laterally from the Ossa temporalia by the Sutura parietomastoidea.

The Os occipitale occupies most of the posterior part of the skull. The central structure is the Squama occipitalis. Frequently, sutural bones (Ossa suturalia) are found along the Sutura lambdoidea. The Protuberantia occipitalis externa is an easily palpable bony reference point on the Os occipitale. Its most protruding point is the Inion. The Protuberantia extends bilaterally in an arch-shaped line as Linea nuchalis superior, a bony crest which serves for the attachment of the autochthonous (intrinsic) muscles of the back. At approximately 2–2.5 cm below the Protuberantia occipitalis externa, the Lineae nuchales inferiores run in a similar arch-shaped fashion, serving as additional attachment sites for muscles.

Fig. 8.10 Skull bones, Ossa cranii, right side; medial view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The cranial cavity includes the skull cap (Calvaria) and the base of the skull which is composed of the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossae. The cranial cavity surrounds the brain with its meninges and encloses the proximal portion of the cranial nerves, including the blood vessels and the venous sinuses. On the inside of the cranial cavity, the pulsations of the A. meningea media have carved out Sulci arteriosi. The Lamina perpendicularis of the Os ethmoidale and the Vomer, the bony part of the nasal septum, are located at the transition region from Neurocranium to Viscerocranium. The Proc. palatinus of the Maxilla and the Os palatinum form the hard palate.

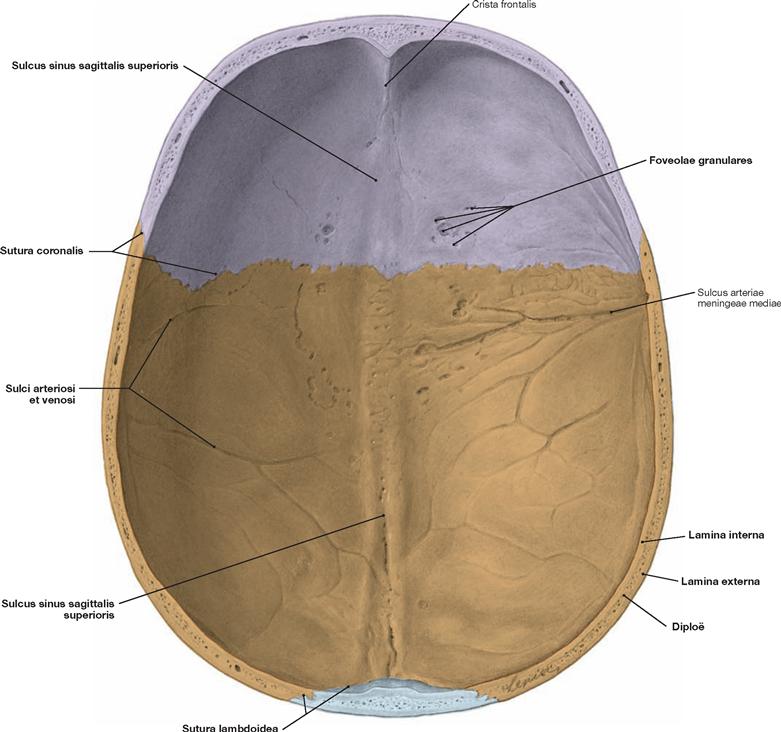

Fig. 8.11 Roof of the skull, Calvaria; inner aspect; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The inside of the skull cap reveals the Sutura coronalis between Os frontale and Ossa parietalia and the Sutura lambdoidea between Ossa parietalia and Os occipitale. Also visible at the inside of the Os frontale is the Crista frontalis which serves as an attachment for the Falx cerebri (duplication of the Dura mater composed of tough fibrous tissue; separates both cerebral hemispheres). The Crista frontalis transitions into the Sulcus sinus sagittalis superioris (location of the Sinus sagittalis superior) which becomes wider and deeper in its posterior part. It extends across the Sutura lambdoidea onto the Os occipitale.

Bilaterally and alongside the entire length of the Sulcus sinus sagittalis superioris, irregularly grouped small depressions (Foveolae granulares, location of the cauliflower-like Granulationes arachnoideae [PACCHIONIAN granulations] are identified. The lateral part of the Calvaria contains multiple grooves (Sulci arteriosi et venosi).

The bones of the Calvaria possess a special structure. They consist of a thick outer and thin inner compacta, named Lamina externa and Lamina interna (Lamina vitrea), and a thin layer of spongiosa, known as Diploë.

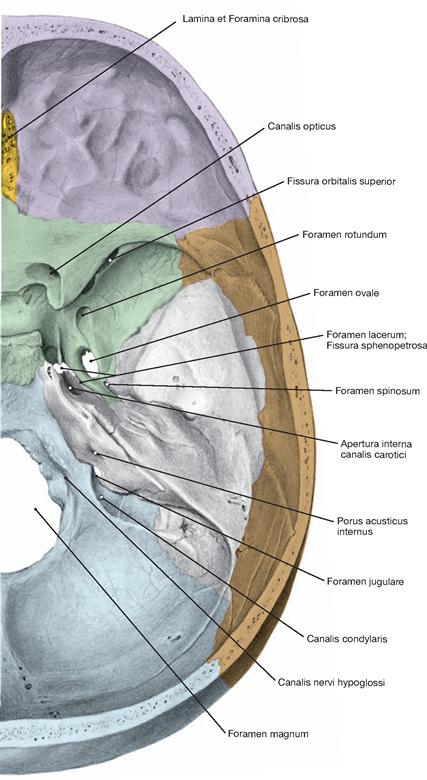

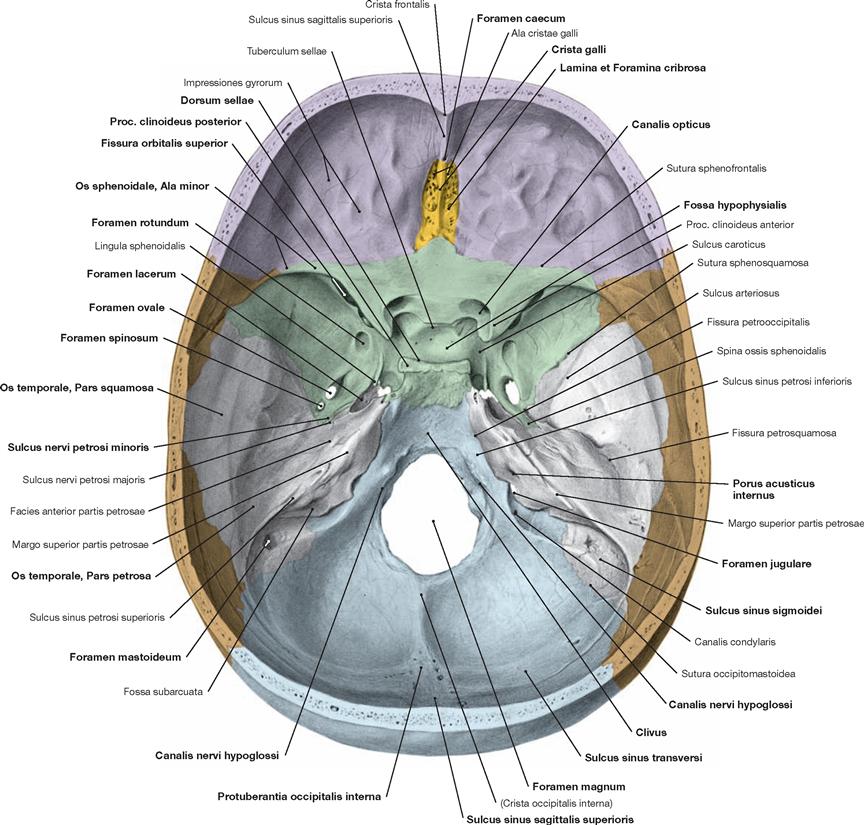

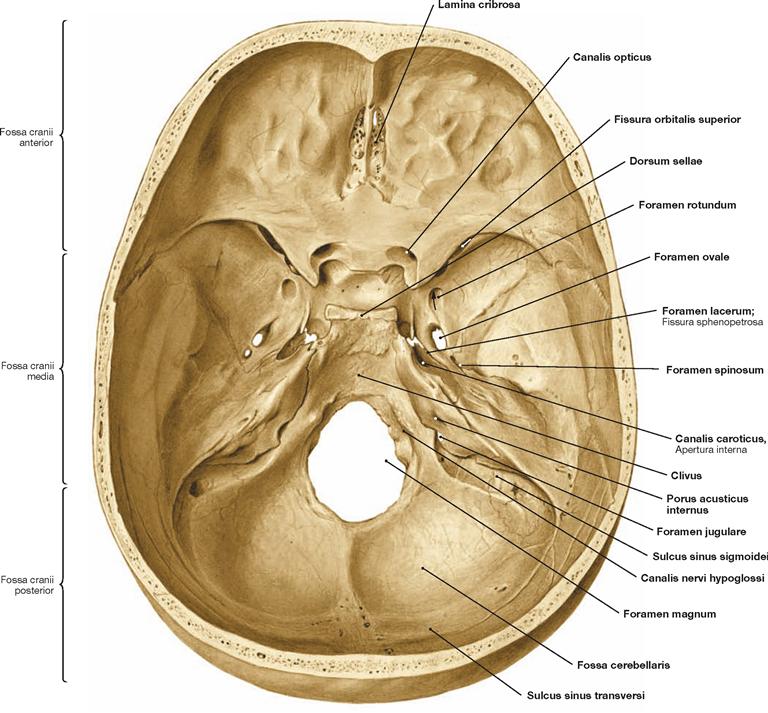

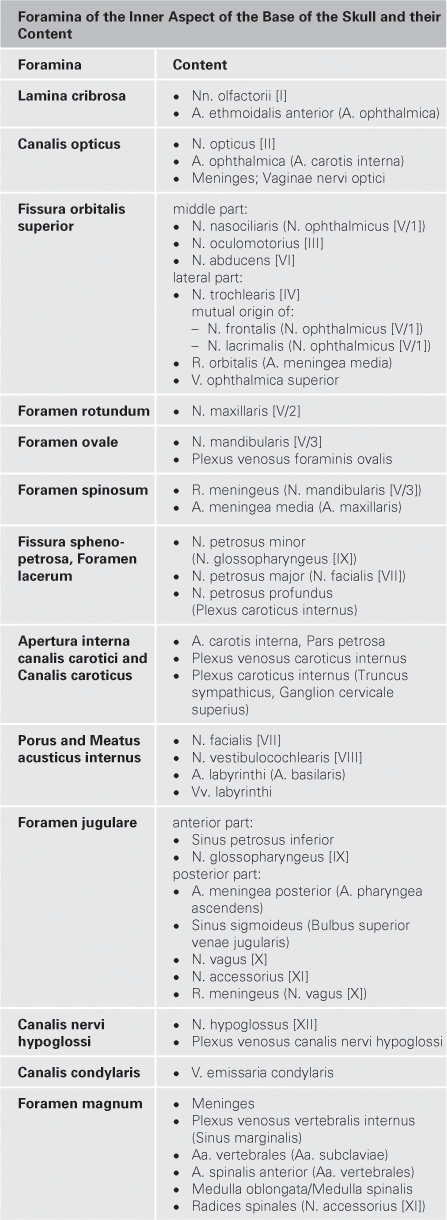

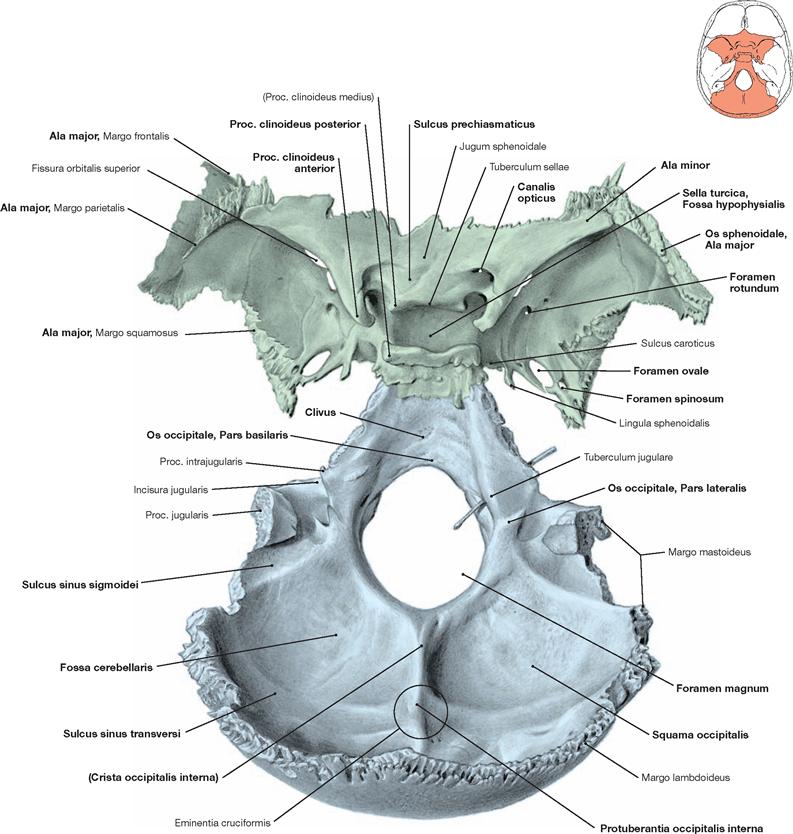

Inner aspect of the base of the skull

Fig. 8.12 Inner aspect of the base of the skull, Basis cranii interna; superior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The anterior (Fossa cranii anterior), middle (Fossa cranii media), and posterior cranial fossae (Fossa cranii posterior) form the inner base of the skull. Ossa frontale, ethmoidalia, and sphenoidale participate in the structure of the anterior cranial fossa. The latter is located above the nasal cavity and orbit and contains the Foramen caecum, the Crista galli (attachment point for the Falx cerebri), and the bilateral Lamina cribrosa. Posterior to the Os frontale and Ossa ethmoidalia, the Corpus and the Alae minores of the Os sphenoidale form the base of the anterior cranial fossa. The Corpus also forms the border to the middle cra- nial fossa.

The middle cranial fossa is composed of the Ossa sphenoidale and temporalia. Its floor is elevated in the midline, and at this point it becomes part of the Corpus of the Os sphenoidale. The pit-shaped lateral portions are parts of the Ala major of the Os sphenoidale and the Pars squamosa of the Os temporale. Located in the middle cranial fossa are the saddle-shaped Sella turcica with the Fossa hypophysialis, and on both sides the Canalis opticus, the Fissura orbitalis superior, and the Foramina rotundum, ovale, spinosum, and lacerum. The Facies anterior partis petrosae demarcates the posterior aspect of the middle cranial fossa.

Fig. 8.13 Inner aspect of the base of the skull, Basis cranii interna; superior view.

Of the three cranial fossae, the posterior cranial fossa is the biggest. It is composed of the Ossa temporalia, the Os occipitale, and, to a smaller extent, of the Os sphenoidale and the Ossa parietalia.

In the midline, its anterior margin is formed by the Dorsum sellae and the Clivus. The Clivus is an oblique bony rim, which creates a slope from the Dorsum sellae to the Foramen magnum. The Clivus is com- posed of parts of the Corpus of the Os sphenoidale and the Pars basilaris of the Os occipitale. The posterior aspect of the posterior cranial fossa consists mainly of the Sulcus sinus transversi. The Foramen magnum is the largest opening of the posterior cranial fossa.

Additional structures of the posterior cranial fossa include the Canalis nervi hypoglossi, the Porus acusticus internus, and the Foramen jugulare. The Sulcus sinus sigmoidei approaches the Foramen jugulare from lateral. The central depression in the posterior cranial fossa is the Fossa cerebellaris.

Outer aspect of the base of the skull

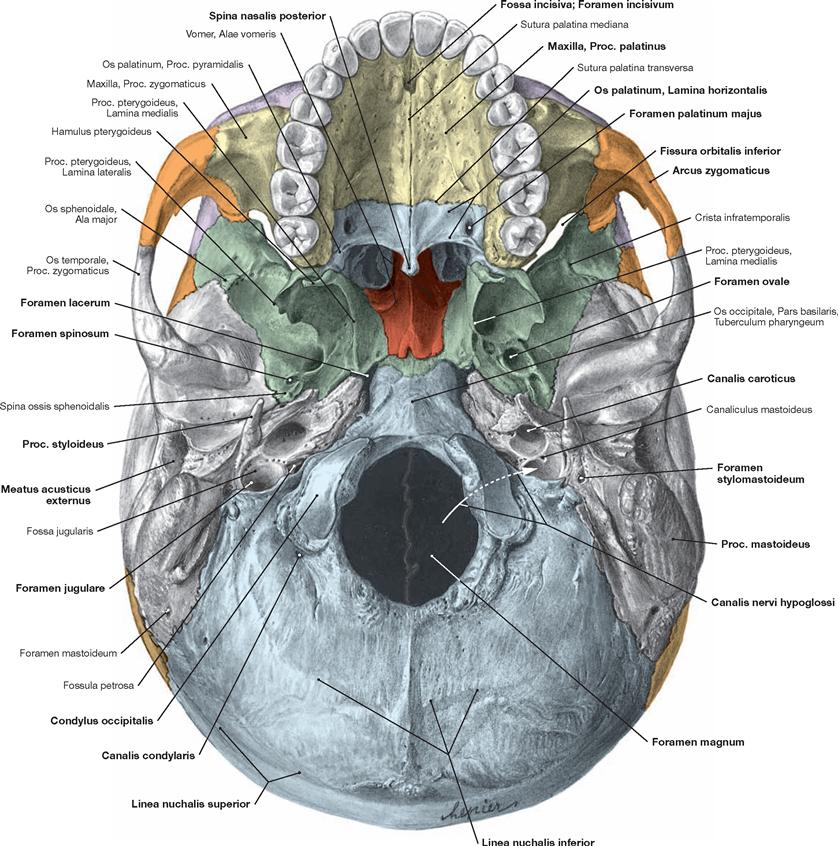

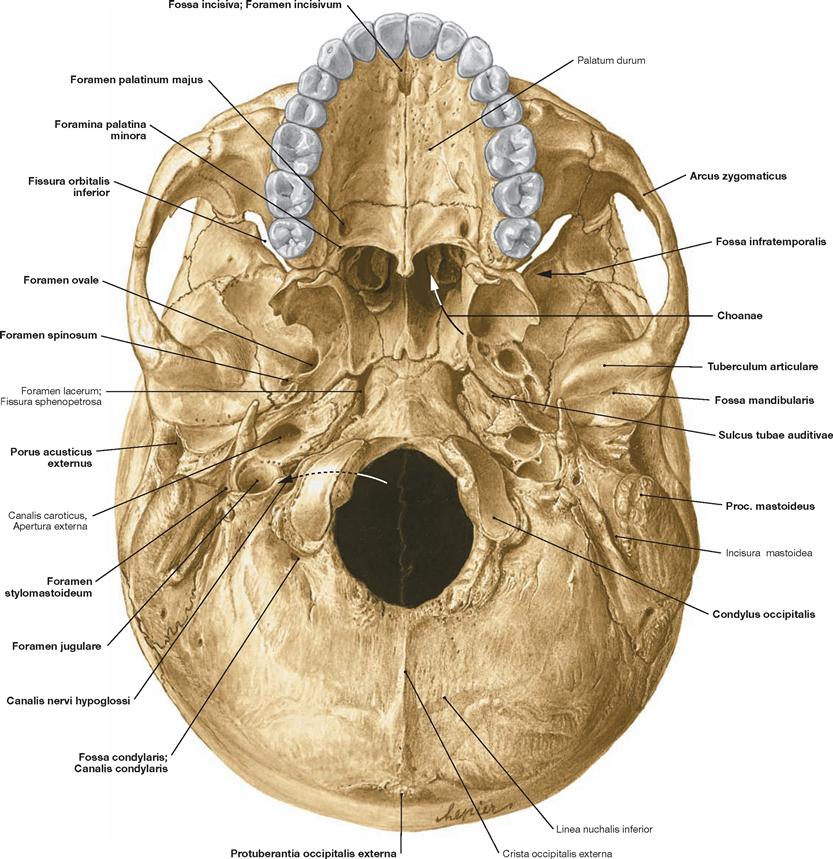

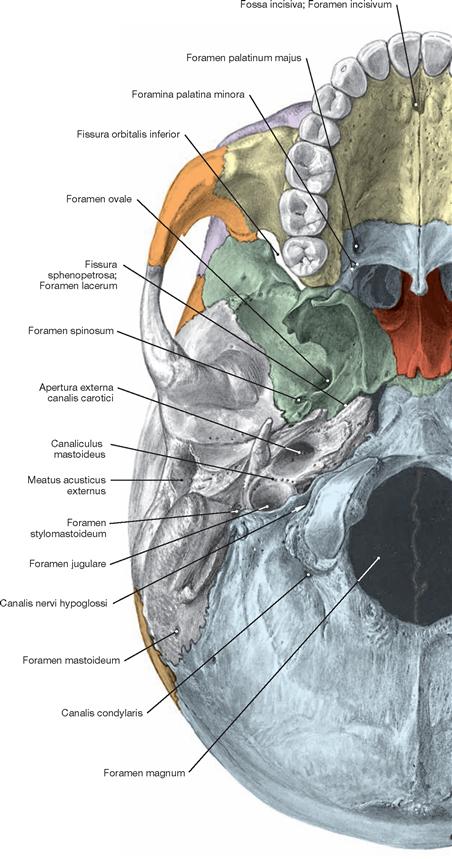

Fig. 8.14 Outer aspect of the base of the skull, Basis cranii externa; inferior view.

The cranial base extends to the middle incisors in the front, bilaterally to the Proc. mastoidei and the Arcus zygomatici, and to the Lineae nuchales superiores in the back. The cranial base divides into three compartments:

• anterior compartment with upper teeth and hard palate

• middle compartment posterior to the palate up to the anterior margin of the Foramen magnum

• posterior compartment from the anterior margin of the Foramen magnum to the Lineae nuchales superiores

Anterior cranial base: encompasses the palate (→ Fig. 8.26). Middle cranial base: the anterior part of this middle compartment is composed of the Vomer and the Os sphenoidale; the Ossa temporalia and the Os occipitale form the posterior part. The Vomer is located in the frontal part of the midline, rides on the Os sphenoidale, and constitutes the posterior part of the nasal septum.

The Os sphenoidale is composed of a central Corpus and the paired Alae majores and Alae minores (not visible from below).

Following directly behind the Corpus of the Os sphenoidale is the Pars basilaris of the Os occipitale, which represents the beginning of the posterior cranial base. The Pars basilaris extends up to the Foramen magnum. Here, the Tuberculum pharyngeum protrudes. It constitutes the bony attachment point for parts of the Pharynx.

Fig. 8.15 Outer aspect of the base of the skull, Basis cranii externa; inferior view.

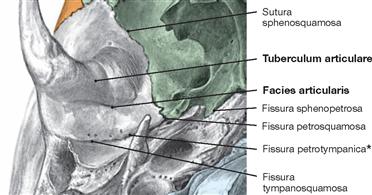

Middle cranial base (continuation of → Fig. 8.14): The Sulcus tubae auditivae is positioned at the border between The Ala major of the Os sphenoidale and the Pars petrosa of the Os temporale and represents the entrance into the bony part of the Tuba auditiva (→ p. 145). The bony canal continues through the Pars petrosa of the Os temporale to the tympanic cavity. Located laterally is the Pars squamosa of the Os temporale which is involved in the formation of the temporomandibular joint (Articulatio temporomandibularis). The Fossa mandibularis is part of the articular surface of the temporomandibular joint (→ pp. 36–39). The Tuberculum articulare is located at the anterior margin of the Fossa mandibularis.

Posterior cranial base: The posterior compartment extends from the anterior margin of the Foramen magnum to the Lineae nuchales superiores and consists of parts of the Os occipitale and Ossa temporalia. Each of the paired Pars lateralis possesses a Condylus occipitalis for the articulation with the Atlas. Located behind the condyle is the Fossa condylaris, which contains the Canalis condylaris; anterior to the con- dyle the Canalis nervi hypoglossi is situated. Immediately lateral thereof lies the Foramen jugulare.

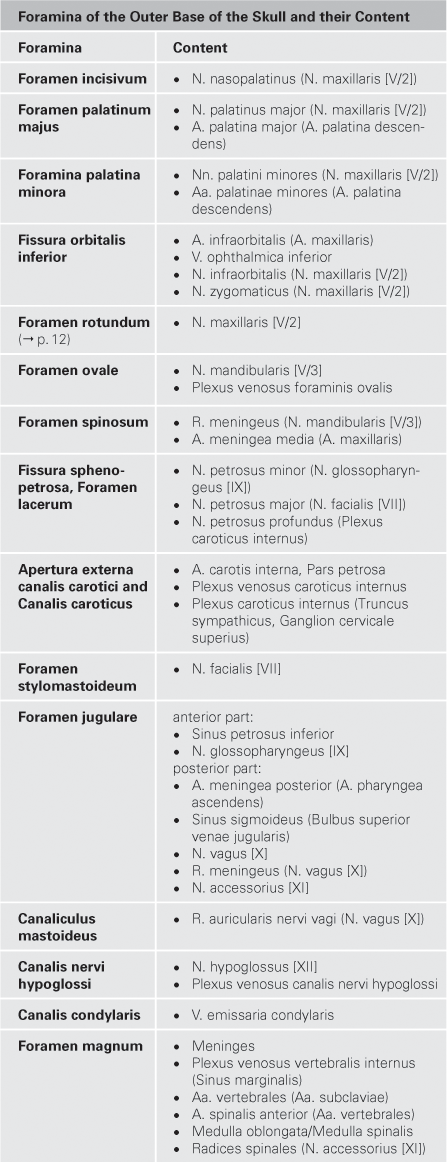

Foramina of the Outer Base of the Skull and their Content

Fig. 8.16 Outer aspect of the base of the skull, Basis cranii externa, with Foramina; inferior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

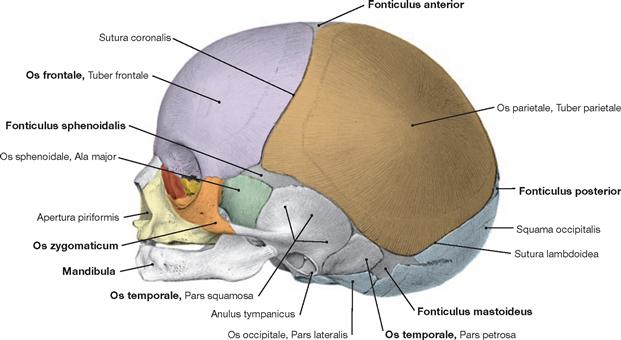

Development of the skull

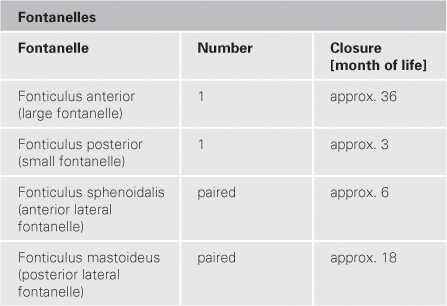

Fig. 8.18 and Fig. 8.19 Skull, Cranium, of a newborn; frontal (→ Fig. 8.18) and lateral (→ Fig. 8.19) views; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

At birth, the newborn has six fontanelles, two unpaired (Fonticuli anterior and posterior) and two paired (Fonticuli sphenoidales and mastoidei). During delivery, sutures and fontanelles serve as reference structures to assess the location and position of the foetal head. Shortly before birth, the Fonticulus posterior becomes the leading part of the head in the case of a normal cephalic presentation.

In concert with the sutures (Suturae), the fontanelles allow a limited deformation of the foetal skull during delivery. The remarkable postnatal growth results in the fontanelles becoming rapidly smaller, and complete closure will occur by the end of the third year of life.

Fig. 8.20 Skull, Cranium, of a newborn; superior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

At birth, the bony plates of the skull cap (Calvaria) are still separated by the interstitial tissue located in the cranial sutures. The sutures are widened to fontanelles (Fonticuli) in regions where more than two bones meet. During life, most sutures, fontanelles (Fonticuli), and synchondroses ossify. Important sutures include the Suturae lambdoidea (lambdoid suture), frontalis (frontal suture), sagittalis (sagittal suture), and coronalis (coronal suture) which gradually fuse up to about 50 years of age (the frontal suture already between the first and second year of life).

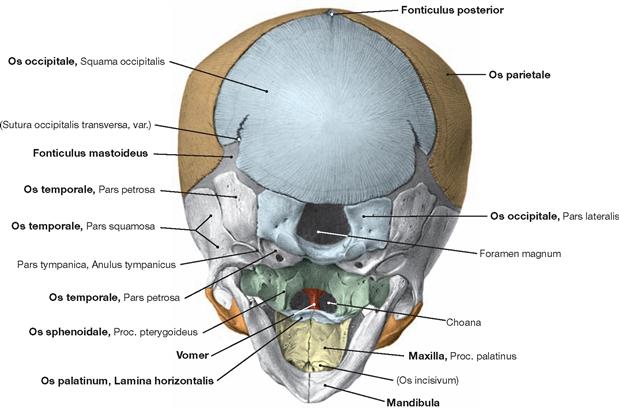

Fig. 8.21 Skull, Cranium, of a newborn; posterior inferior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

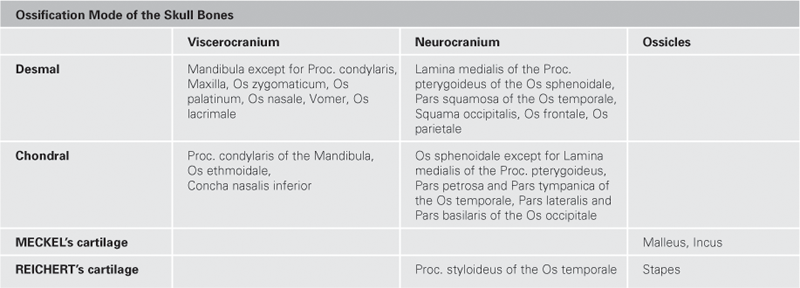

The development of the skull involves a desmal and an enchondral ossification mode (→ table). The mesenchyme of the head is the primordial building material that derives from the prechordal mesoderm, the occipital somites, and the neural crest. At the time of birth, some cranial bones are linked by cartilaginous joints (Articulationes cartilagineae; Synchondroses cranii).

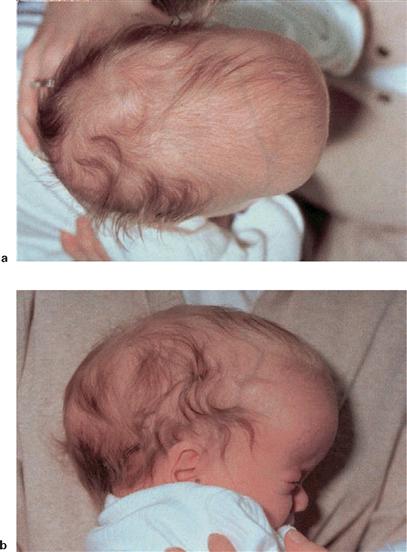

Craniostenoses

Fig. 8.22 a and b Craniostenoses; child with Scaphocephalus. [20]

This clinical picture is the result of a premature closure of the sagittal suture. The skull cap is disproportionally long.

Frontal and ethmoidal bones

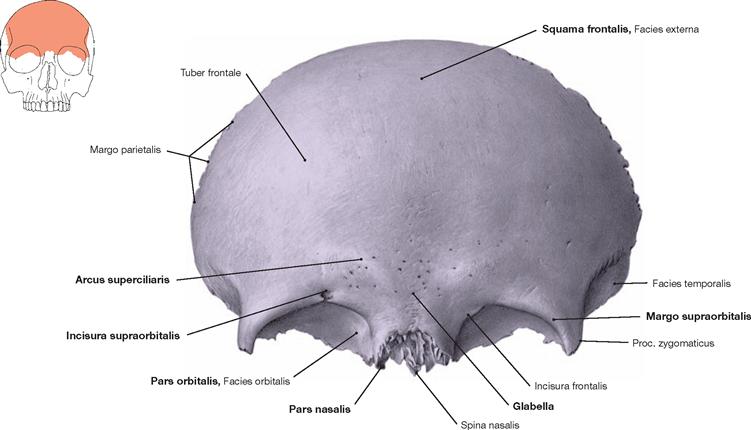

Fig. 8.23 Frontal bone, Os frontale; frontal view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

Located most anterior in the skull cap, the frontal bone participates in the formation of the walls of the orbital and nasal cavity. The unpaired Os frontale has four parts:

Above the upper margin of the orbit (Margo supraorbitalis) the prominent Arcus superciliaris protrudes, a phenotype commonly more devel- oped in men than in women. In the midline between the two Arcus, the bone is flat and creates the Glabella (area between the eyebrows). Frequently, a Foramen supraorbitale, more rarely an Incisura frontalis, is present at the medial margin of the orbit.

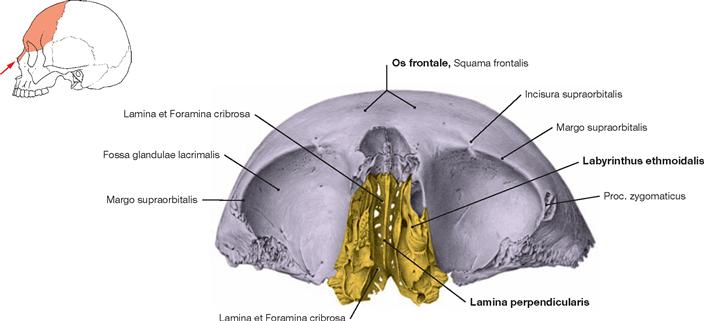

Fig. 8.24 Frontal bone, Os frontale, ethmoidal bone, Os ethmoidale, and nasal bones, Ossa nasalia; inferior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The Os ethmoidale and Ossa nasalia connect with the Os frontale in a medial anterior and caudal position and form part of the nasal skeleton. The Sinus frontalis is located within the frontal bone.

Upper jaw and palatine bone

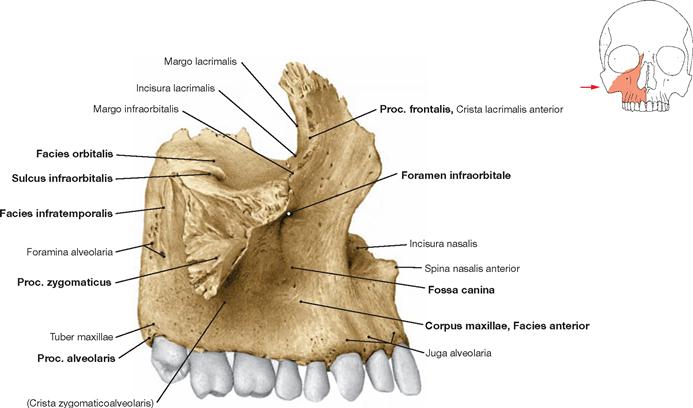

Fig. 8.25 Upper jaw, Maxilla, right side; lateral view.

The upper jaw can be divided into the body of maxilla (Corpus maxillae), frontal process (Proc. frontalis, connects with the Os frontale), zygo- matic process (Proc. zygomaticus, connects with the zygomatic bone), palatine process (Proc. palatinus, anterior part of the palate, → Fig. 8.26), and alveolar process (Proc. alveolaris). The latter creates the lower margin of the Maxilla and is composed of the dental alveoli (Alveoli dentales) which contain the roots of the teeth. The protruding anterior rim of these dental sockets are named Juga alveolaria. The Foramen infraorbitale is located in the Corpus maxillae, immediately below the lower orbital margin.

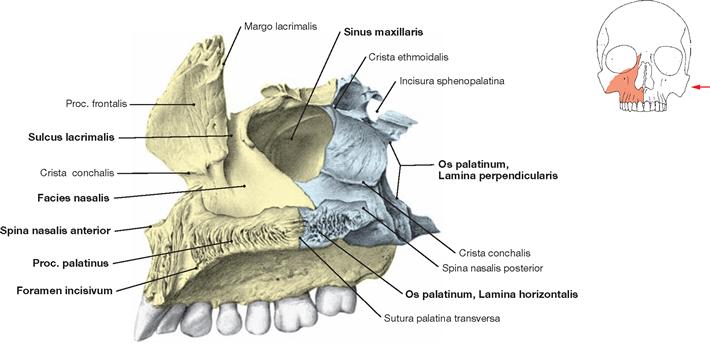

Fig. 8.26 Upper jaw, Maxilla, and palatine bone, Os palatinum, right side; medial view into the Sinus maxillaris; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

Posterior to the Maxilla lies the palatine bone which is composed of two plates: The Lamina horizontalis creates the posterior part of the palate (Palatum osseum), the Lamina perpendicularis extends vertically upright (perpendicular to the horizontal lamina) and is the posterior medial margin of the Sinus maxillaris.

Nasal cavity

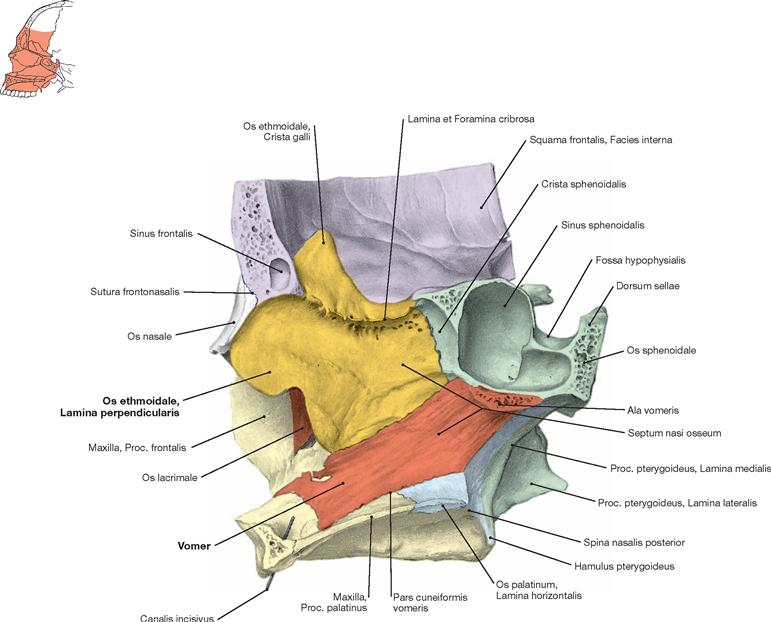

Fig. 8.27 Bony septum of the nose, Septum nasi osseum; lateral view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

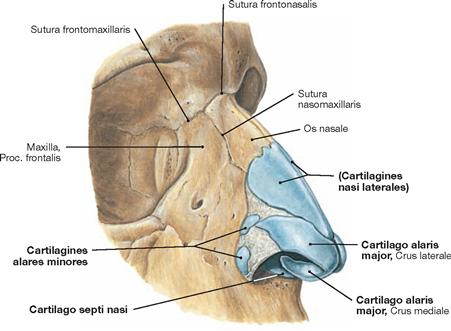

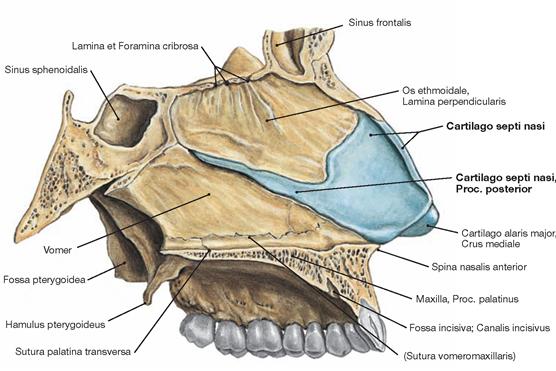

The Lamina perpendicularis of the ethmoidal bone (Os ethmoidale) and the Vomer create the bony septum of the nose. The Os ethmoidale is located between the Os frontale and Maxilla and is also connected with the Ossa nasalia, lacrimalia, sphenoidale, and palatina. At its top, the ethmoidal bone forms the Crista galli. Perforated with multiple holes, the Lamina cribrosa is the roof of the nasal cavity and part of the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. The Lamina perpendicularis of the Os ethmoidale is located below the Crista galli, divides the bony labyrinth of the ethmoidal bone into a right and left part, and constitutes the upper part of the bony nasal septum.

The Vomer forms the largest part of the bony nasal septal skeleton. This flat and trapezoid bone connects cranially with the Lamina perpendicularis of the Os ethmoidale and at its posterior aspect via the Ala vomeris with the Os sphenoidale. Caudally, its Pars cuneiformis vomeris borders at the Proc. palatinus of the Maxilla and at the Lamina horizontalis of the Os palatinum.

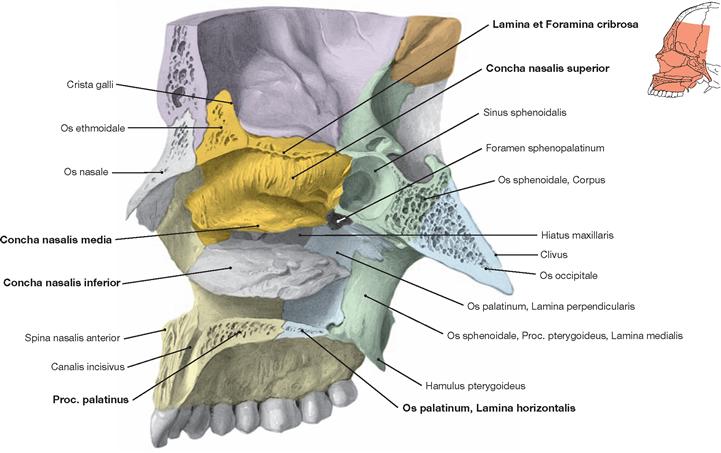

Fig. 8.28 Lateral wall of the nasal cavity, Cavitas nasi; right side; view from the left side; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The view onto the lateral wall of the nasal cavity reveals the roof cre- ated by the Lamina cribrosa of the ethmoidal bone (Os ethmoidale) which also forms the upper (Concha nasalis superior) and middle nasal conchae (Concha nasalis media). The upper nasal passage (Meatus nasalis superior) is located between the two nasal conchae. Below sits the inferior nasal concha (Concha nasalis inferior) as a separate bone.

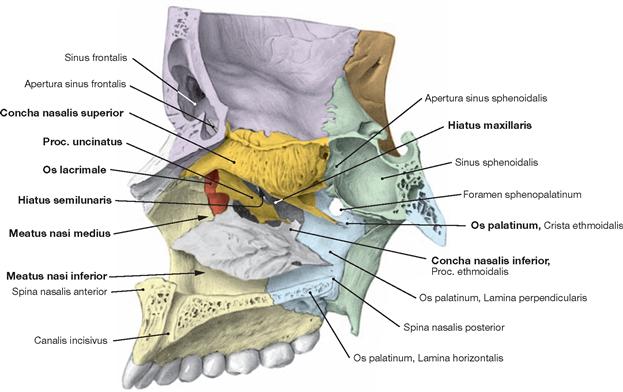

Fig. 8.29 Lateral wall of the nasal cavity, Cavitas nasi; right side; medial view after the middle nasal concha was removed; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

Beneath the middle nasal concha, a thin bony lamella, the Proc. uncinatus, is part of the ethmoidal bone. It provides only an incomplete closure of the medial wall of the maxillary sinus. Many openings remain above and below the Proc. uncinatus and one of them is the Hiatus maxillaris.

The Maxilla and the Os palatinum create the floor and parts of the lateral wall (floor: Lamina horizontalis; lateral wall: Lamina perpendicularis). The Os lacrimale is also part of the lateral wall and contributes to the anterior margin of the maxillary sinus. The Concha nasalis inferior is anchored to all of these three bones and divides the nasal wall in a middle (Meatus nasalis medius) and an inferior nasal passage (Meatus nasalis inferior) which are located above and below this nasal concha, respectively.

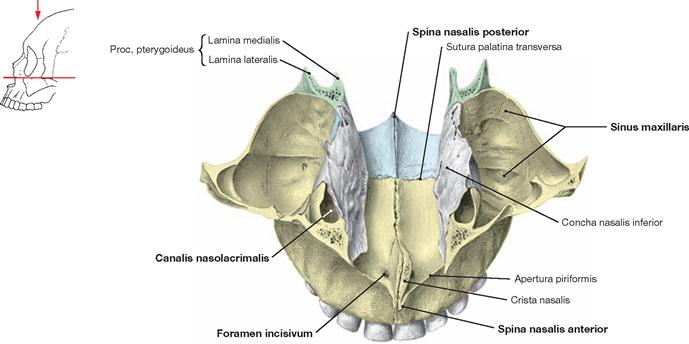

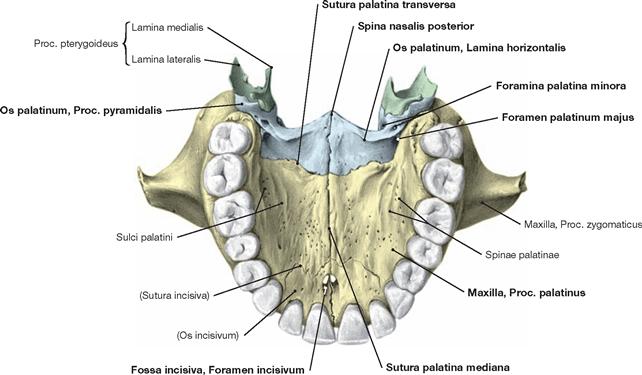

Hard palate

Fig. 8.30 Hard palate, Palatum durum; Maxillary sinus, Sinus maxillaris, and inferior nasal concha, Concha nasalis inferior; superior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

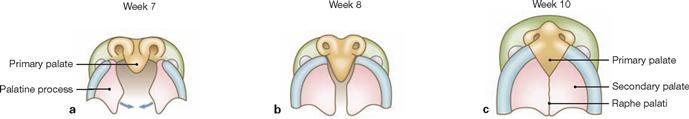

The hard palate represents a horizontal bony plate created by the Maxilla and the Os palatinum. It separates the oral front from the nasal cavity. The Foramen incisivum is a connection between both cavities. The present image shows the floor of the nasal cavity. Located laterally are the Sinus maxillares.

Fig. 8.31 Hard palate, Palatum durum; inferior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The hard palate is part of the anterior cranial fossa. The teeth are attached to the two maxillary alveolar arches. These arches are the anterior and lateral margins of the hard palate. Its rostral part consists of the Procc. palatini of the two Maxillae and the Laminae horizontales of the Ossa palatina in its posterior aspect. In the midline, the Procc. palatini are connected by the Sutura palatina mediana and dorsally they connect via the Sutura palatina transversa with the Ossa palatina. The Laminae horizontales of the Ossa palatina are connected in the midline by the Sutura interpalatina (a continuation of the Sutura palatina mediana).

Located behind the incisures in the frontal part of the midline is the Fossa incisiva which becomes the Foramen incisivum and the Canales incisivi. Near the posterior margin to both sides of the hard palate are the Foramina palatina majora, which become Canales palatini majores, and the Foramina palatina minora. The latter are located in the Proc. pyramidalis of the Os palatinum and open into the Canales palatini minores. In the posterior aspect of the midline, the Spina nasalis posterior protrudes as a pointed process of the hard palate.

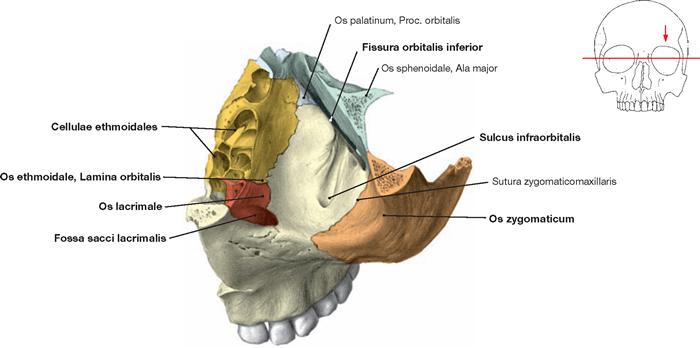

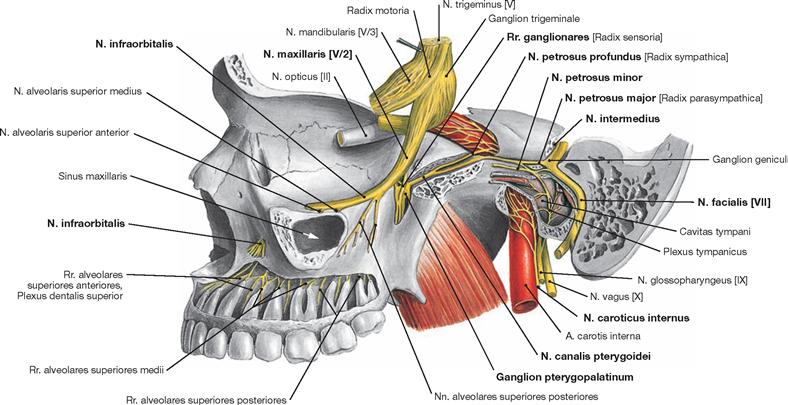

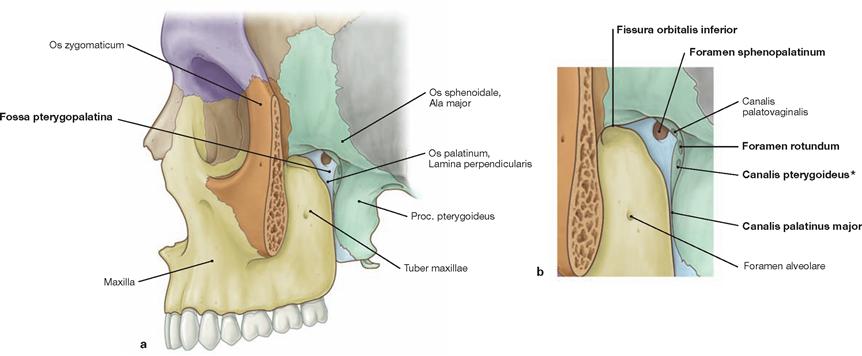

Orbit and pterygopalatine fossa

Fig. 8.32 Floor of the orbital cavity, Paries inferior orbitae, left side; superior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The floor of the orbit is the roof of the maxillary sinus. In it lies the Sulcus infraorbitalis, which becomes a bony canal below the floor of the orbit and ends in the Foramen infraorbitale. It contains the N. infraorbitalis and the corresponding blood vessels. The Os zygomaticum forms the lateral part of the floor of the orbit and the medial part is composed of the Lamina orbitalis of the Os ethmoidale and the Os lacrimale. Together with the Maxilla, the latter creates the Fossa sacci lacrimalis containing the Glandula lacrimalis. For the orbital cavity → Figs. 9.9 to 9.13.

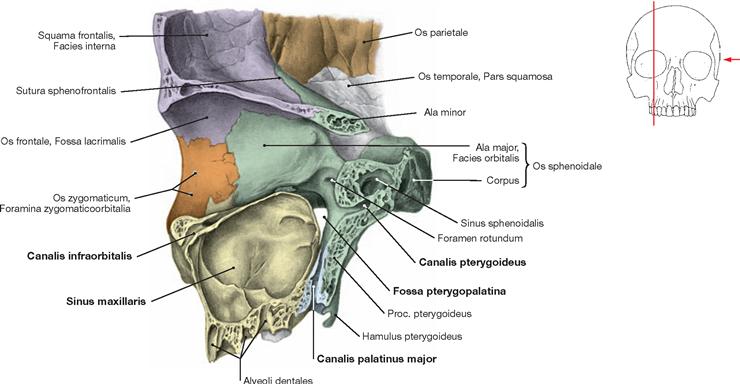

Fig. 8.33 Pterygopalatine fossa, Fossa pterygopalatina, left side; lateral view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The Fossa pterygopalatina is the medial continuation of the Fossa infratemporalis. Its bony margins are the Maxilla, the Os palatinum, and the Os sphenoidale. This fossa is an important relais station connecting the middle cranial fossa, the orbit, and the nasal cavity. It serves as a conduit for many nerves and blood vessels located in these structures (→ pp. 78 and 79).

The lateral access route to the pterygopalatine fossa is a common surgical strategy for the resection of tumours in this region, such as nasopharyngeal fibroma.

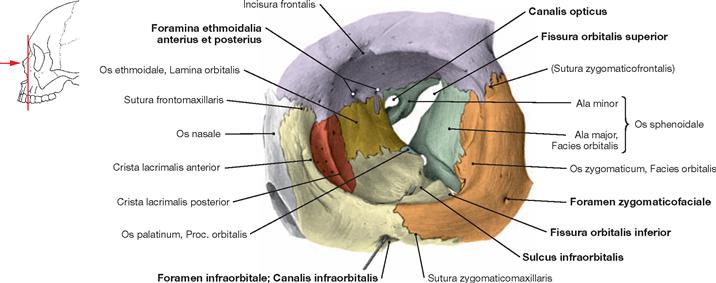

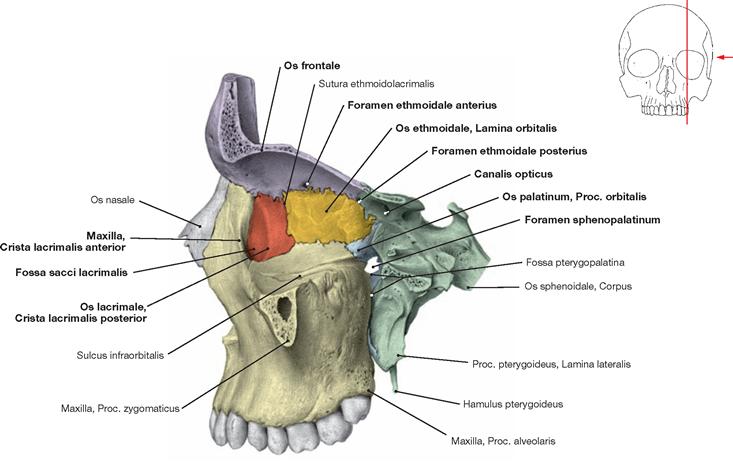

Orbit

Fig. 8.34 Orbit, Orbita, left side; frontal view; probe in the the Canalis infraorbitalis; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The Ossa ethmoidale, lacrimale, palatinum, sphenoidale, zygomaticum, and the Maxilla create the margins of the orbital cavity. Passages to and from the orbit are the Fissurae orbitales superior and inferior, the Canalis opticus, and the Foramina ethmoidalia anterius and posterius. Lo- cated in the posterior part of the orbital floor, the Sulcus infraorbitalis becomes the Canalis infraorbitalis which projects towards the front of the orbit and ends as Foramen infraorbitale located below the inferior margin of the orbit. Positioned laterally, the Os zygomaticum regularly contains a Foramen zygomaticofaciale. For the orbital cavity → Figs. 9.9 to 9.13.

Fig. 8.35 Viscerocranium, Viscerocranium; frontal section at the level of the two Orbitae; frontal view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The unpaired ethmoidal bone (Os ethmoidale) contains the anterior and posterior ethmoidal cells (Cellulae ethmoidales). The Lamina perpendicularis of the Os ethmoidale lies immediately beneath the Crista galli, separates the bony labyrinth of the ethmoidal bone into a right and a left half, and participates in the upper part of the bony nasal septum. At its posterior aspect it is followed by the Vomer. The lateral walls of the Cellulae ethmoidales consist of a thin Lamina orbitalis, known as Lamina papyracea, constituting the major part of the medial wall of the orbit. The Sinus maxillaris is located directly below the orbit. The Canalis infraorbitalis is located in its roof, which also constitutes the floor of the orbit. The Lamina cribrosa positions clearly below the roof of the orbit. For the orbital cavity → Figs. 9.9 to 9.13.

Fig. 8.36 The lateral wall of the orbit, Paries lateralis orbitae, right side; medial view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The Ossa zygomaticum, frontale, sphenoidale, and the Maxilla form the lateral wall of the orbit. The Canalis infraorbitalis is depicted clearly in the anterior third of the orbital floor, as is the very thin bony layer separating the orbit from the Sinus maxillaris. The Fossa pterygopalatina is located posteriorly to the Sinus maxillaris and connects laterally to the Fossa infratemporalis, cranially to the orbit, and in its inferior aspect connects to the oral cavity via the Canalis palatinus major. From a posterior cranial position, the Canalis pterygoideus exits into the Fossa pterygopalatina.

Fig. 8.37 The medial wall of the orbit, Paries medialis orbitae, left side; lateral view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The Os lacrimale, the Maxilla, and the Os frontale form the anterior part of the medial wall of the orbit, whereas in the posterior part the Lamina orbitalis of the Os ethmoidale (Lamina papyracea), the Proc. orbitalis of the Os palatinum, and the Os sphenoidale are placed between the Os frontale and the Maxilla. Both, the Crista lacrimalis anterior of the Maxilla and the Crista lacrimalis posterior of the Os lacrimale provide the margins for a depression (Fossa sacci lacrimalis) of the lacrimal sac. Located in the medial wall of the orbit are the Foramina ethmoidalia anterius and posterius and the Canalis opticus. The Foramen sphenopalatinum is located at the top of the Fossa pterygopalatina.

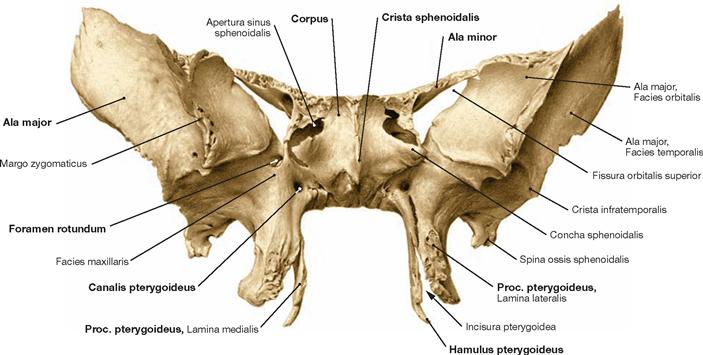

Sphenoidal bone

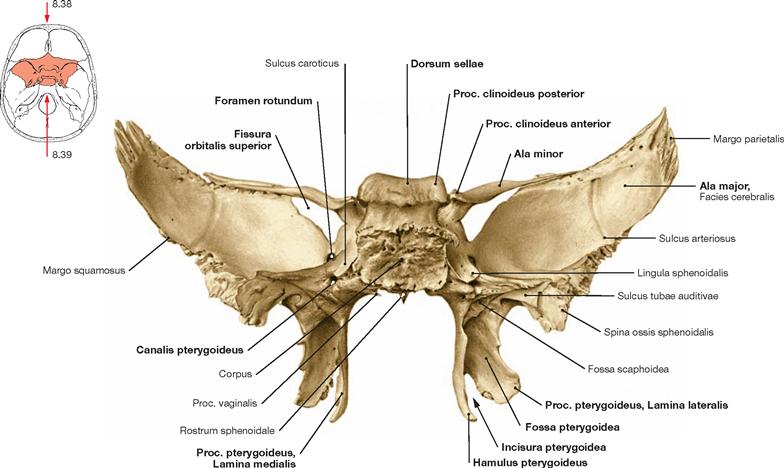

Fig. 8.38 Sphenoidal bone, Os sphenoidale; frontal view.

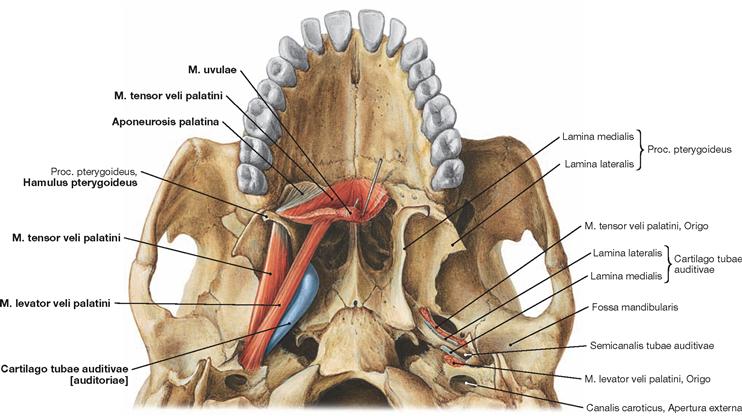

The unpaired Os sphenoidale connects the viscerocranium with the neurocranium. Two pairs of wing-shaped bones (Alae) extend from the body (Corpus) of the sphenoidal bone. The Alae minores sit on the top, the Alae majores at the bottom, and below the Procc. pterygoidei project. The centre of the sphenoidal bone contains the Sinus sphenoidales. The Crista sphenoidalis subdivides the anterior part of the Corpus into two halves.

Fig. 8.39 Sphenoidal bone, Os sphenoidale; posterior view.

Ala minor and Ala major of the Os sphenoidale participate in the formation of the Fissura orbitalis superior. On both sides, the Proc. pterygoideus divides into a smaller Lamina medialis and a larger Lamina lateralis, which create the Incisura (Fissura) pterygoidea and enclose the Fossa pterygoidea. The Hamulus pterygoideus is the caudal extension of the Lamina medialis. At its base, the Canalis pterygoideus perforates the Os sphenoidale and enters into the Fossa pterygopalatina.

Sphenoidal bone and occipital bone

Fig. 8.40 Sphenoidal bone, Os sphenoidale, and occipital bone, Os occipitale; superior view; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The centre of the Os sphenoidale is composed of the Sella turcica with the Fossa hypophysialis. The Tuberculum sellae creates the anterior rim of the Fossa hypophysialis and extends laterally into the Proc. clinoideus medius. The Sulcus prechiasmaticus and the Jugum sphenoidale are located in front of the Tuberculum sellae. The Clivus forms the posterior part of the saddle-shaped Sella turcica and the Proc. clinoideus posterior represents the lateral elevated end of its upper rim. In the region of the Sella turcica and at its anterior rim, the Canalis opticus perforates the Ala minor. The Foramina rotundum, ovale, and spinosum pierce the Ala major bilaterally in an anterior cranial to posterior caudal direction.

The unpaired Os occipitale is composed of the Squama occipitalis, two Partes laterales, and one Pars basilaris. These four parts delimit the Foramen magnum. At the inner surface of the Squama occipitalis, the Sulcus sinus sagittalis superioris and the Sulci of the Sinus transversi meet at the Protuberantia occipitalis interna. Further, the Sulcus sinus sigmoidei and the Sulcus sinus occipitalis are visible at the inner surface. Above and below the Protuberantia occipitalis, the inner surface of the Squama occipitalis forms the Fossa cerebralis and the Fossa cerebellaris, respectively. Together with the Corpus of the Os sphenoidale, the Pars basilaris of the Os occipitale generates the Clivus.

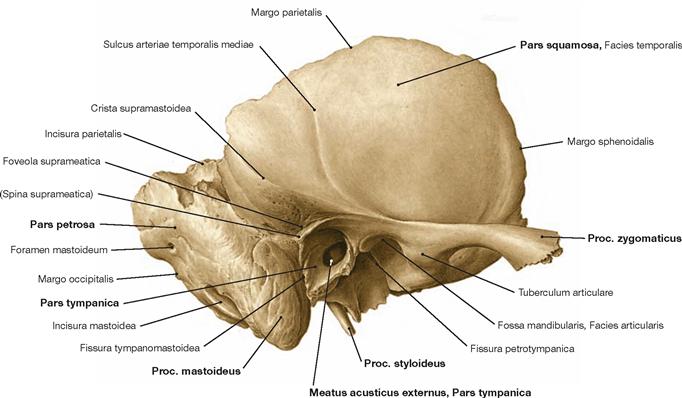

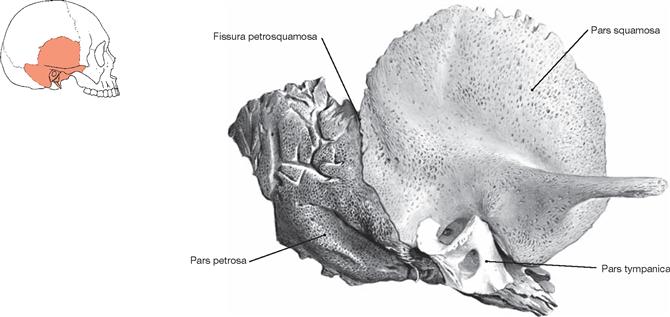

Temporal bone

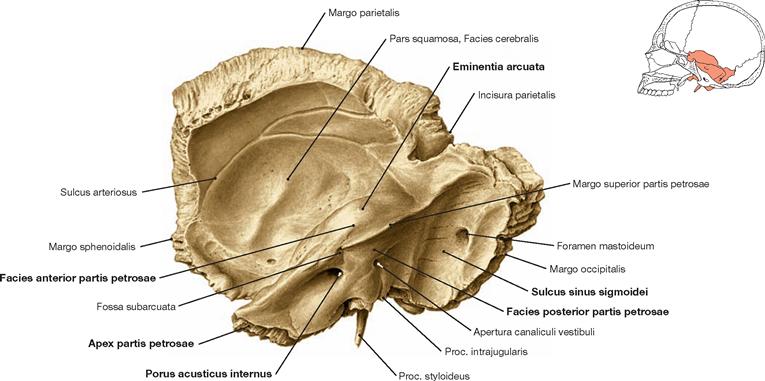

Fig. 8.41 Temporal bone, Os temporale, right side; lateral view.

The paired Os temporale is part of the viscerocranium and neurocranium. It participates in the formation of the lateral side and the base of the cranium. The Pars squamosa, the Pars tympanica, and the Pars petrosa (petrous bone) can be distinguished.

Through its Margo parietalis, the squama-shaped Pars squamosa connects with the Os parietale. The Proc. zygomaticus protrudes anterior and superior of the Meatus and extends in an anterior direction.

The Pars petrosa borders at the Ossa parietale and occipitale. The central outer opening is the Meatus acusticus externus. Located at its posterior caudal aspect is the Proc. mastoideus. Middle and inner ear are located within the Pars petrosa (not visible). Access routes are the internal acoustic meatus (Meatus acusticus internus, → p. 17), the Foramen stylomastoideum (→ p. 16) and the Canalis musculotubarius (→ Figs. 10.30 and 10.37).

The Pars tympanica forms the bony wall of the external acoustic meatus. As a ring-shaped structure, it is associated with the Partes squamosa and petrosa. The Pars tympanica delimits the Meatus acusticus externus at its frontal, caudal, and posterior side and extends to the tympanic membrane (→ Figs. 10.15 and 10.25).

Fig. 8.42 Temporal bone, Os temporale, of a newborn, right side; lateral view; schematic drawing; colour chart see inside of the back cover of this volume.

The image displays different parts of the temporal bone: Pars squamosa, Pars petrosa, and Pars tympanica.

Fig. 8.43 Temporal bone, Os temporale, right side; inner aspect.

The Pars petrosa is shaped like a pyramid with its tip (Apex partis petrosae) directed anterior medial and its base pointing towards the Proc. mastoideus. The Facies anterior is part of the middle cranial fossa and contains the protruding Eminentia arcuata; contained within the Facies posterior is the Porus acusticus internus which constitutes the entrance to the Meatus acusticus internus. The posterior surface of the Pars petrosa shows the indentation by the Sulcus sinus sigmoidei. The Foramen mastoideum is located here as well. On the inner surface (Facies cerebralis) of the Pars squamosa the Sulcus arteriosi of the A. meningea media are visible.

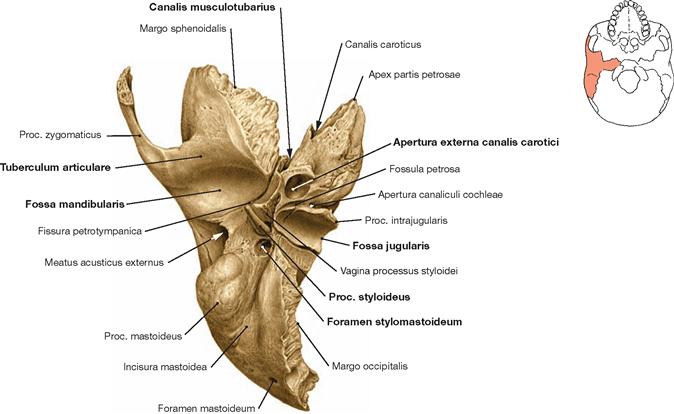

Fig. 8.44 Temporal bone, Os temporale, right side; inferior view.

The Facies inferior of the Os temporale depresses to become the Fossa jugularis and, together with the Os occipitale, delineates the Foramen jugulare. The notch at the border between the Pars squamosa and Pars petrosa indicates the starting point of the Canalis musculotubarius. In addition, the Apertura externa canalis carotici and the Proc. styloideus are visible. The Foramen stylomastoideum opens to the lateral posterior side. Just in front of the external acoustic meatus, the Pars squamosa contains the Fossa mandibularis which, at its rostral aspect, is demarcated by the Tuberculum articulare.

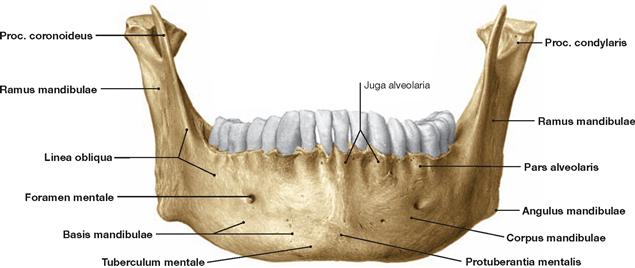

Lower jaw

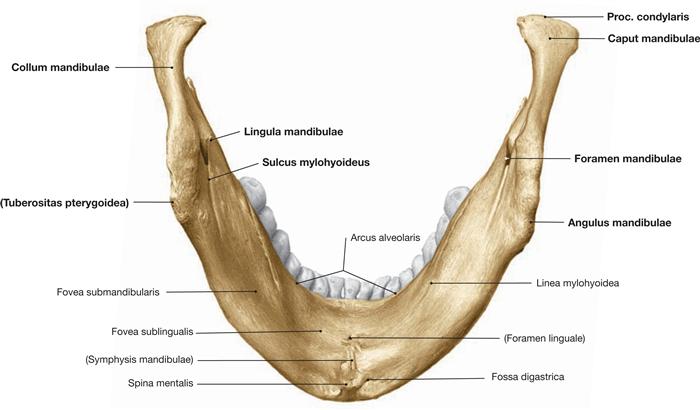

Fig. 8.45 Lower jaw, Mandibula; frontal view.

The unpaired Mandibula consists of a body of the mandible (Corpus mandibulae) and two rami (Rami mandibulae). Each ramus divides into a Proc. coronoideus and a Proc. condylaris. The body of the mandible is composed of the base and the Pars alveolaris separated by the Linea obliqua which descends from the Proc. coronoideus in an oblique anterior trajectory. The frontal part of the Pars alveolaris consists of the chin (Mentum) with the Protuberantia mentalis, the bilateral mental tubercles (Tubercula mentalia) and the Foramina mentalia.

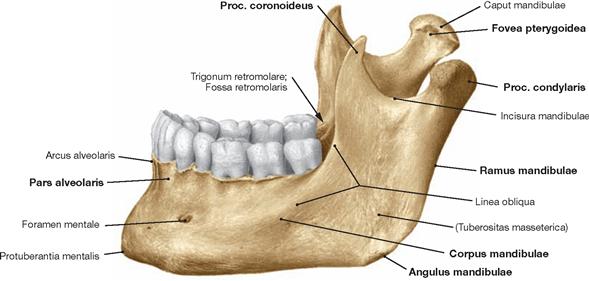

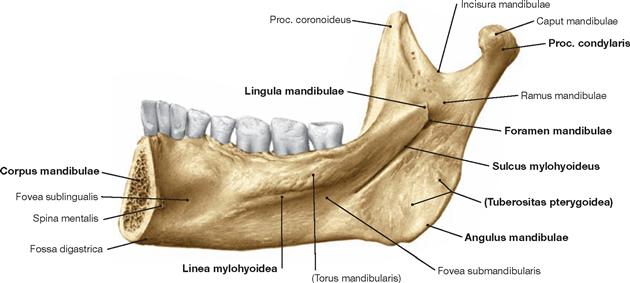

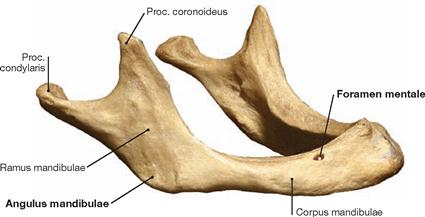

Fig. 8.46 Lower jaw, Mandibula; lateral view. Corpus mandibulae and Ramus mandibulae merge at the Angulus.

The Caput mandibulare sits on top of the Proc. condylaris.

Fig. 8.47 Lower jaw, Mandibula; inner aspect of the mandibular arch.

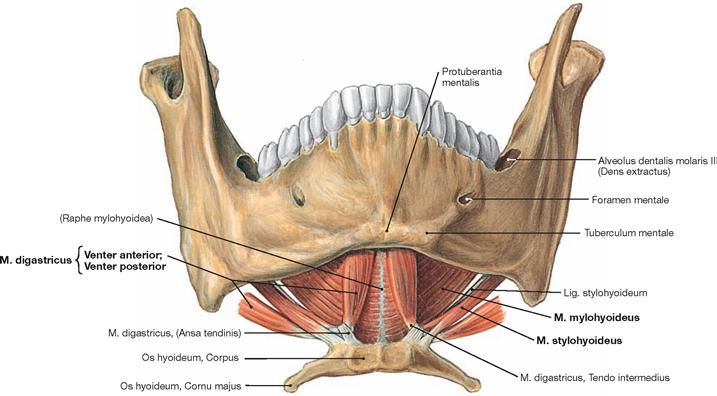

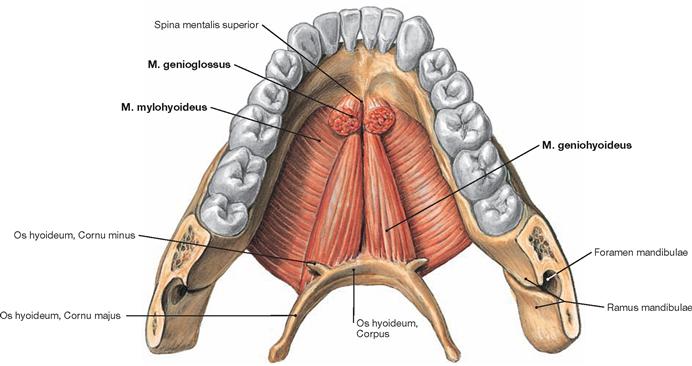

The Foramen mandibulae is located at the inside of the Ramus mandibulae. In front thereof, the Linea mylohyoidea creates a stepwise crest, which serves as an attachment for the M. mylohyoideus and demarcates the level of the floor of the mouth.

Fig. 8.48 Lower jaw, Mandibula; inferior view.

The Spina mentalis is located at the inside of the Mandibula close to the midline. Bony depressions represent the Fossa digastrica below and lateral to the Spina mentalis and the Fovea sublingualis and Fovea submandibularis above the Spina mentalis. On the inside of the Angulus mandibulae the Tuberositas pterygoidea is found.

Fig. 8.49 Lower jaw, Mandibula, of an old person.

Loss of teeth – particularly at an advanced age – results in a regression of the Pars alveolaris of the Mandibula. This can progress until the Foramen mentale becomes located at the upper rim of the toothless lower jaw. The Angulus mandibulae has a much wider angle than in a mandible with dentition.

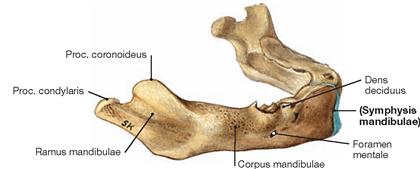

Fig. 8.50 Lower jaw, Mandibula, of a newborn.

In a newborn, the Symphysis mandibulae connects the two mandibular segments. The angle between the Corpus and Ramus mandibulae is still very large.

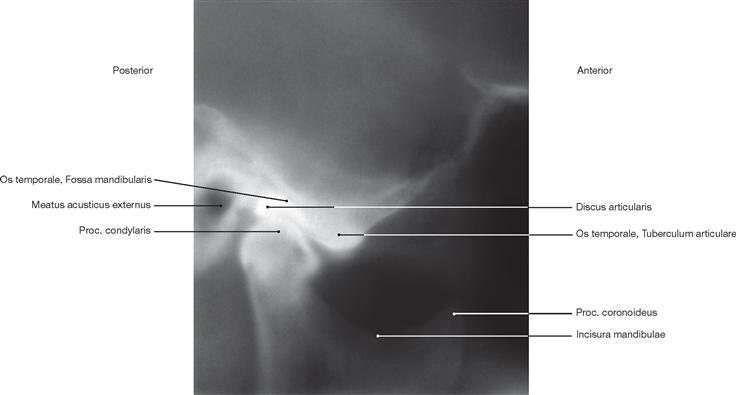

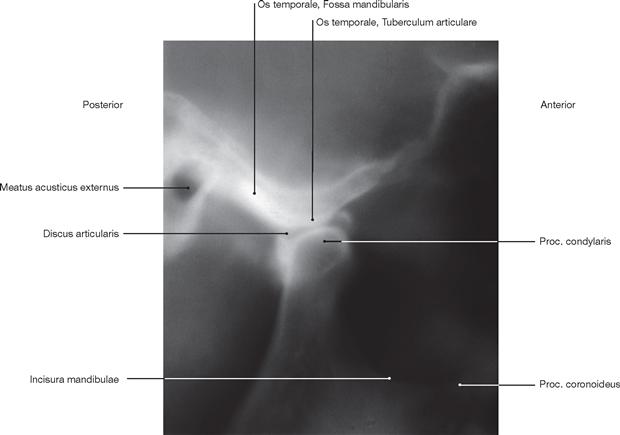

Temporomandibular joint

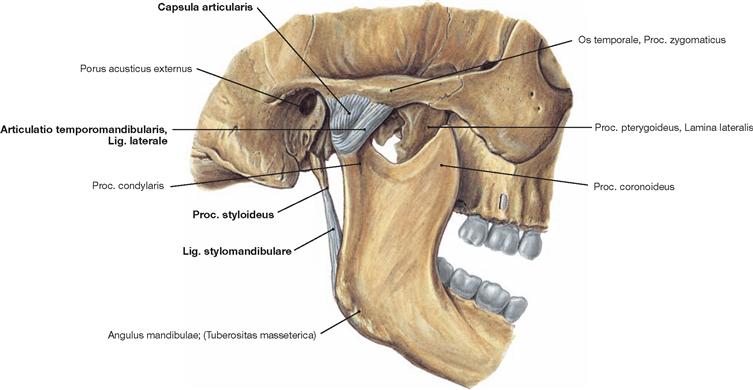

Fig. 8.51 Temporomandibular joint, Articulatio temporomandibularis, right side; lateral view.

A wide cone-shaped joint capsule (Capsula articularis) stretching from the temporal bone to the Proc. condylaris surrounds the mandibular joint. In its frontal and lateral parts, the Lig. laterale reinforces the joint capsule and extends from the zygomatic arch in an oblique posterior caudal direction to the Collum mandibulae. At the inside of the joint (not shown), connective tissue generates the variable Lig. mediale. The Ligg. laterale and mediale (if present) assist in guiding the joint movements and foremost inhibit posterior movements of the mandibular head. When bite force is applied, the Lig. laterale also stabilises the Condylus. The Lig. stylomandibulare projects from the Proc. styloideus to the posterior rim of the Ramus mandibulae. It is usually weak and, together with the Lig. sphenomandibulare, resists further lower jaw movements at a position close to maximal opening of the mouth (→ Fig. 8.52).

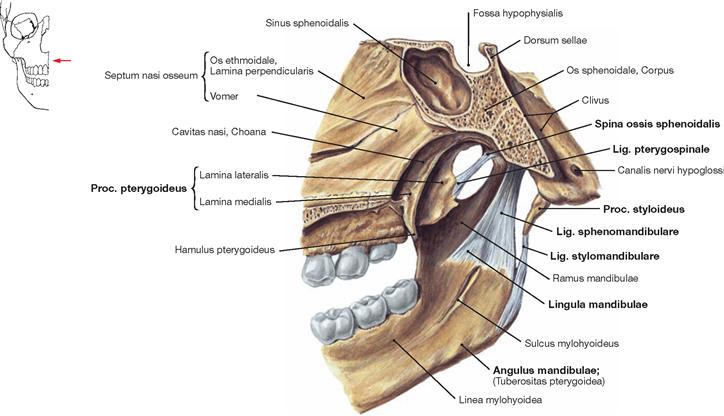

Fig. 8.52 Lig. stylomandibulare and Lig. sphenomandibulare, right side; medial view.

Both ligaments affect the kinematics of the temporomandibular joint but are not associated with the joint capsule.

The strong Lig. sphenomandibulare has its origin at the Spina ossis sphenoidalis and passes between the Mm. pterygoidei lateralis and medialis and inserts in a fan-shaped pattern at the Lingula mandibulae. The Lig. stylomandibulare originates from the Proc. styloideus and projects to the Angulus mandibulae. Together, both ligaments inhibit lower jaw movements at a position close to the maximal opening of the mouth.

The Lig. pterygospinale has no relationship to the temporomandibular joint nor does it affect the joint kinematics. It has its origin at the Spina ossis sphenoidalis and inserts at the Lamina lateralis of the Proc. pterygoideus. This ligament has a stabilising function.

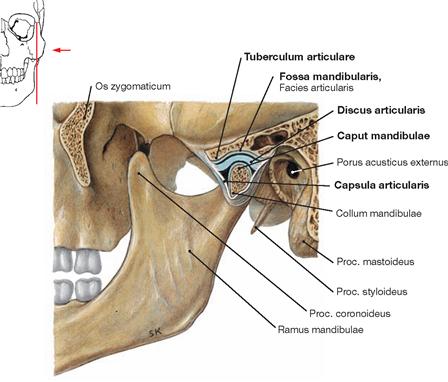

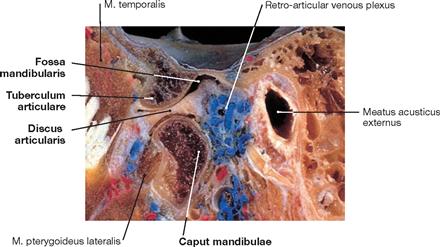

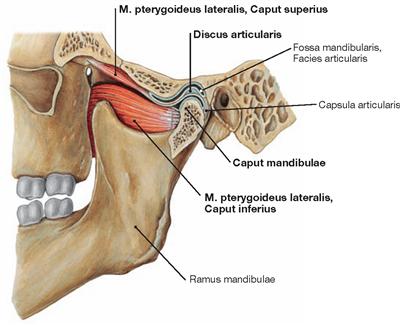

Fig. 8.53 Temporomandibular joint, Articulatio temporomandibularis, left side; sagittal section; lateral view; mouth almost closed.

In the temporomandibular joint, the Caput mandibulae, Fossa mandibularis, and Tuberculum articulare of the temporal bone articulate with each other. Both joint components are separated by a disc (Discus articularis). The temporomandibular joint is positioned in front of the bony part of the external acoustic meatus (Porus acusticus externus).

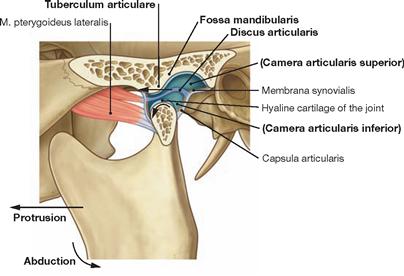

Fig. 8.54 Temporomandibular joint, Articulatio temporomandibularis, left side; sagittal section; lateral view; mouth opened. [8]

A Discus articularis completely divides the temporomandibular joint into two separate chambers (dithalamic joint):

• The lower chamber permits hinge-like opening and closure movements of the Mandibula.

• The upper chamber allows for the Caput mandibulae to slide forward on the Tuberculum articulare (protrusion). This particularly requires the action of the M. pterygoideus lateralis. The movement back into the Fossa mandibularis is called retraction (retrusion).

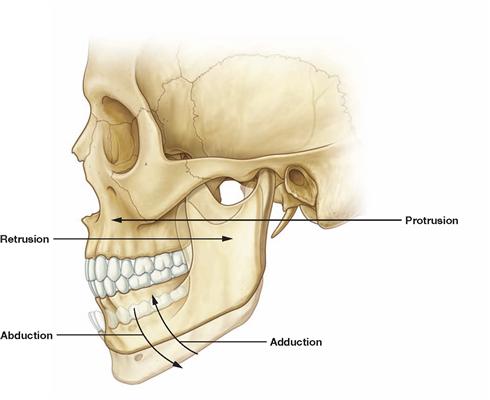

Fig. 8.55 Movements of the temporomandibular joint, Articulatio temporomandibularis, left side; lateral view. [8]

Independent movements in one temporomandibular joint are not possible because both temporomandibular joints are joined in the bony mandibular arch. The temporomandibular joints permit two main functions during chewing: elevation (adduction) and depression (abduction) of the lower jaw as well as grinding movements. Apart from abduction and adduction, the forward (protrusion) and backward movement (retrusion) as well as grinding (sideways sliding – laterotrusion and mediotrusion) constitute the movement patterns of the temporomandibular joint. The masticatory muscles contribute in different ways to the mobility of the joint.

Fig. 8.56 Fossa and tubercle of the temporomandibular joint, Articulatio temporomandibularis, right side; inferior view.

View onto the Facies articularis of the Fossa mandibularis, which is normally covered with hyaline articular cartilage. Also covered by hyaline cartilage, the Tuberculum articulare is located anterior to the Fossa mandibularis. In the posterior third of the Fossa mandibularis, the Pars squamosa connects with the Pars petrosa of the Os temporale, and medially the Os temporale borders at the Os sphenoidale. As a result, this region contains three fissures:

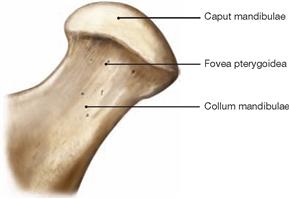

Fig. 8.57 Articular process, Proc. condylaris, of the lower jaw, right side; frontal view.

The Proc. condylaris is composed of a Caput and Collum mandibulae. At the frontal side, it contains the Fovea pterygoidea. Here, the M. pterygoideus lateralis attaches with its Caput inferius.

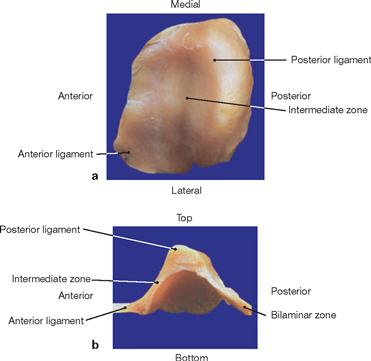

Fig. 8.58 a and b Articular disc, Discus articularis, of the temporomandibular joint, Articulatio temporomandibularis.

From front to back, the Discus articularis consists of an anterior ligament (connective tissue), an intermediate zone (fibrous cartilage), a posterior ligament (connective tissue), and a bilaminar zone (connective tissue). In its lateral part, the intermediate zone is particularly thin.

Fig. 8.59 Temporomandibular joint, Articulatio temporomandibularis; sagittal section at the level of the temporomandibular joint region with injected veins (coloured); lateral view. [1]

The bilaminar zone between the Tuberculum articulare and Caput mandibulae is visible. The bony septum between the middle cranial fossa and the Fossa mandibularis is thin. Among the connective tissue of the bilaminar zone lies an extensive retro-articular venous plexus. Close proximity exists to the external acoustic meatus.

Muscles

Facial muscles

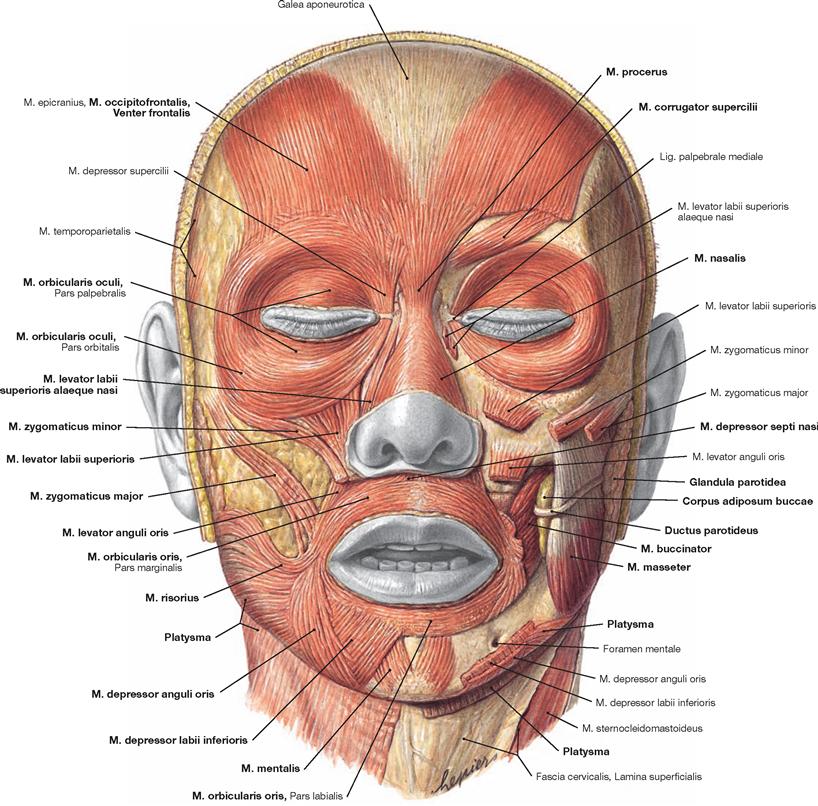

Fig. 8.62 Facial muscles, Mm. faciei, and masticatory muscles, Mm. masticatorii; frontal view.

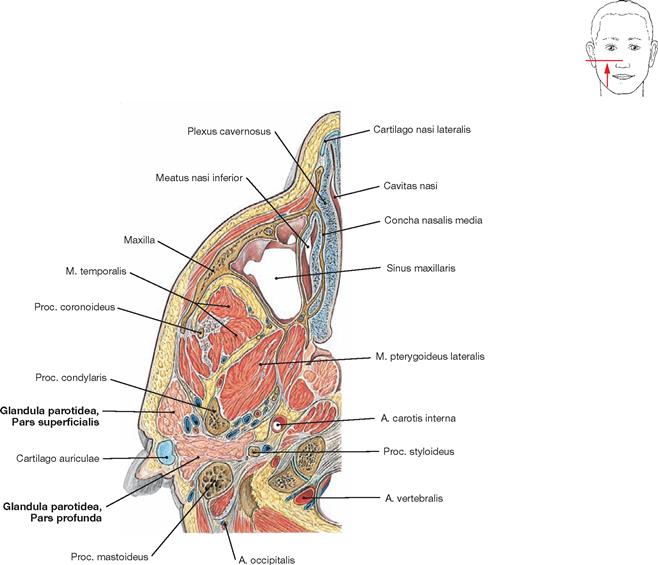

Mimic muscles determine the facial expression and create the individual appearance of a facial physiognomy of a person. The muscles around the eye have important protective functions, while the muscles in the region of the mouth serve in food uptake and articulation.

Visible on both sides of the face are the Venter frontalis of the M. occipitofrontalis (M. epicranius), the Partes orbitalis and palpebralis of the M. orbicularis oculi (Pars lacrimalis → Fig. 9.19), the M. corrugator supercilii, the M. procerus, the Mm. nasalis, depressor septi nasi, levator labii superioris alaeque nasi, the M. orbicularis oris with Pars labialis and Pars marginalis, the M. buccinator, the Mm. zygomatici major and minor, the Mm. risorius, levator labii superioris, levator anguli oris, depressor anguli oris, depressor labii inferioris and mentalis as well as the Platysma projecting onto the neck.

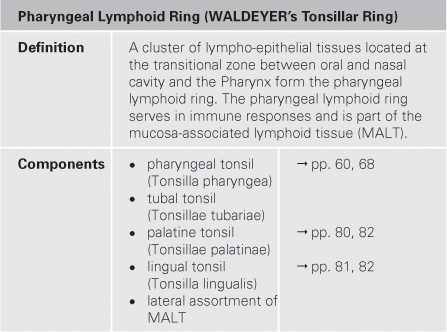

Of the masticatory muscles, only the M. masseter on the left side of the face is shown. The Ductus parotideus (STENSON’s duct) of the Glandula parotidea passes across the M. masseter and bends around its frontal edge in an almost right angle to penetrate the M. buccinator. A fat pad (Corpus adiposum buccae, BICHAT’s fat pad) is located between the M. masseter and the M. buccinator and contributes to the contour of the region of the cheek. With the exception of the M. buccinator, the facial muscles do not contain a fascia. The fasciae of the M. buccinator, the M. masseter, and the Glandula parotidea have been removed.![]()

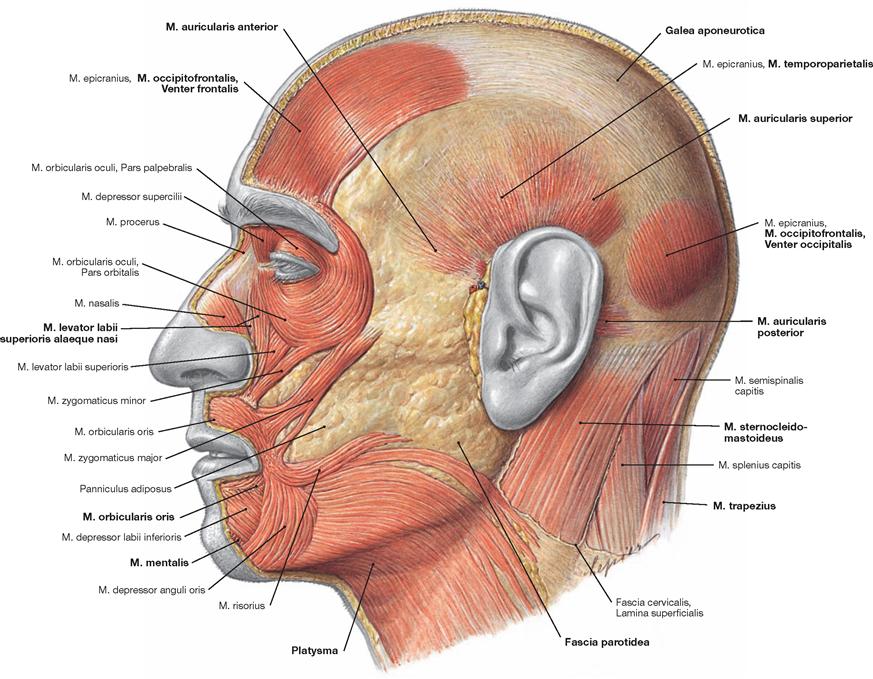

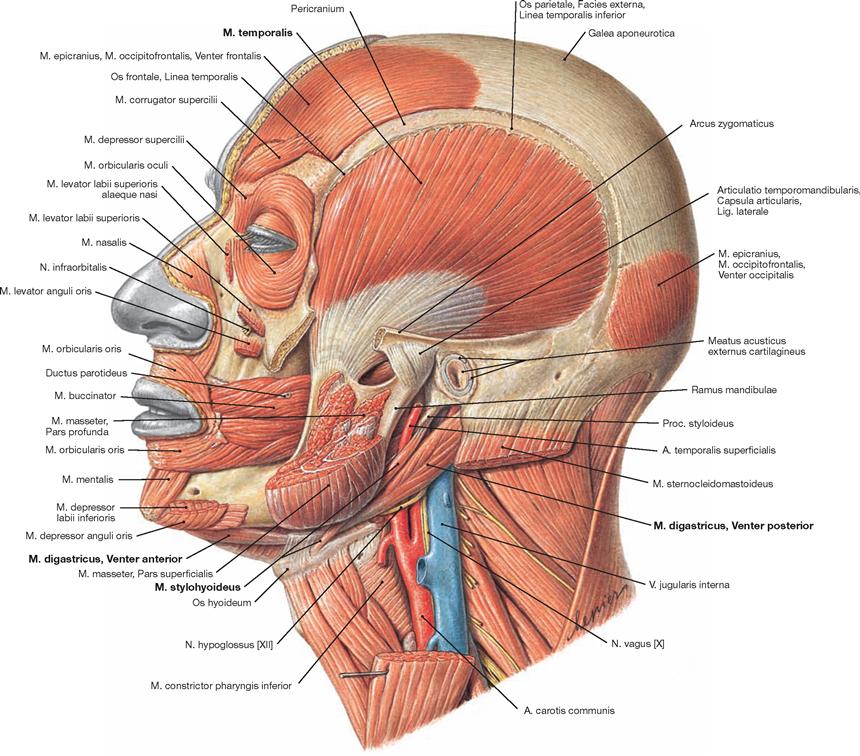

Fig. 8.63 Facial muscles, Mm. faciei, left side; lateral view.

In addition to the muscles displayed in → Figure 8.62, this lateral view also shows the Venter occipitalis of the M. occipitofrontalis (M. epicranius) with the Galea aponeurotica extending between the Venter frontalis and the Venter occipitalis. Located above the ear and also projecting into the Galea aponeurotica is the M. temporoparietalis (also a part of the M. epicranius) which originates from the Fascia temporalis. Additional mimetic muscles are also shown and include the Mm. auriculares anterior, superior, and posterior. In the neck region, parts of the M. sternocleidomastoideus, the M. trapezius, and some autochthonous muscles of the back are visible.![]()

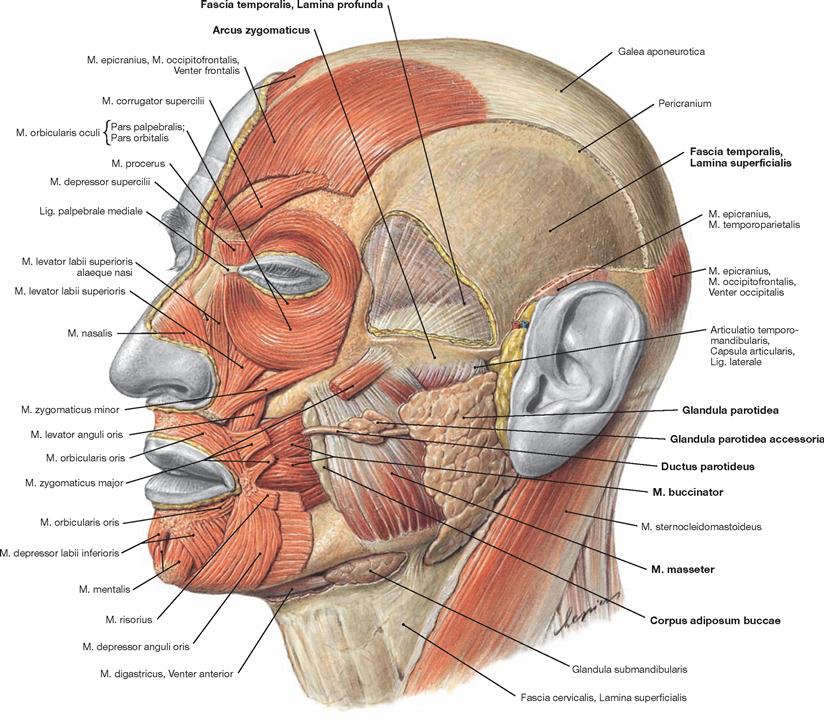

Facial and masticatory muscles

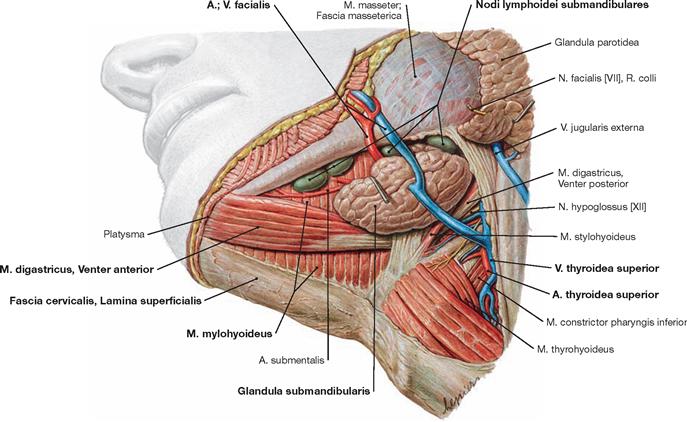

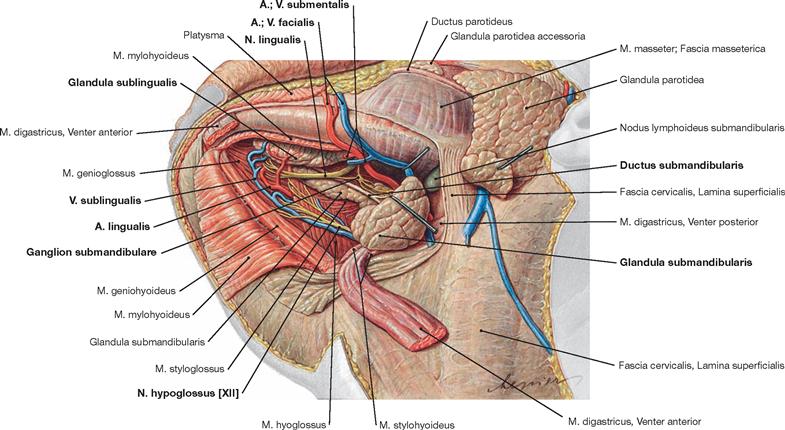

Fig. 8.64 Facial muscles, Mm. faciei, and masticatory muscles, Mm. masticatorii; lateral view from an oblique angle.

The fascia of the M. buccinator, the M. masseter, the Glandula parotidea as well as part of the superficial fascia of the neck were removed. As a result, the corresponding muscles, the Glandula parotidea extending to the neck, and the Glandula submandibularis become visible. The major excretory duct of the Glandula parotidea, the Ductus parotideus (STENSEN’s duct), exits the gland at its anterior pole, crosses the M. masseter in a horizontal line from posterior to anterior and, at the anterior margin of the M. masseter, bends inwards in an almost perfect right angle to penetrate the M. buccinator. Between the M. buccinator and M. masseter lies the Corpus adiposum buccae (BICHAT’s fat pad). Associated with the Ductus parotideus is accessory glandular tissue (Glandula parotidea accessoria).

In the temporal region, the M. parietoparietalis of the M. epicranius was removed. This allows a clear view onto the superficial lamina (Lamina superficialis) of the Fascia temporalis.

Above the zygomatic arch (Arcus zygomaticus) parts of the Lamina superficialis and the temporal fat pad underneath (Corpus adiposum temporalis) were removed to permit a clear view onto the deep lamina (Lamina profunda) of the Fascia temporalis with the M. temporalis shining through.![]()

Fig. 8.65 Facial muscles, Mm. faciei, and masticatory muscles, Mm. masticatorii, left side; lateral view.

Upon removal of the superficial and the deep laminae of the temporal fascia and the partial removal of the zygomatic arch and parts of the M. masseter, the M. temporalis becomes visible.

The origin of the M. temporalis along the Linea temporalis inferior of the Facies externa of the Os parietale and the Linea temporalis of the Os frontale are shown. The muscle fibres converge into a flat tendon that disppears in the Fossa infratemporalis behind the zygomatic arch and inserts at the Proc. coronoideus.

Origins of the M. temporalis:

• Linea temporalis inferior of the Facies externa of the Os parietale

• Facies temporalis of the Os frontale

• Facies temporalis, Pars squamosa of the Os temporale

• Facies temporalis of the Os zygomaticum

• Facies temporalis of the Os sphenoidale up to the Crista infratemporalis

The image also displays a few suprahyal muscles (M. digastricus with Venter anterior and Venter posterior, M. stylohyoideus).![]()

Masticatory muscles

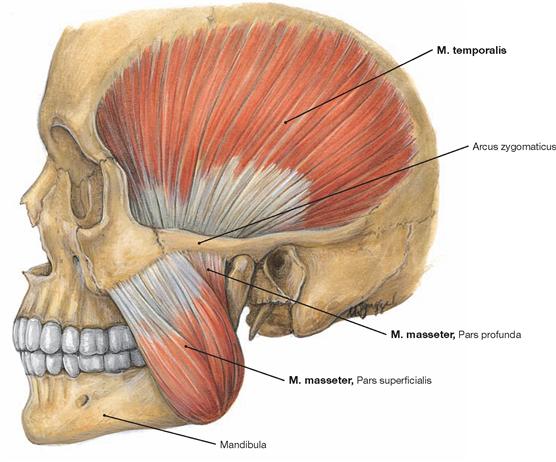

Fig. 8.66 M. masseter and M. temporalis, left side; lateral view.

The M. masseter consists of a Pars superficialis and a Pars profunda.![]()

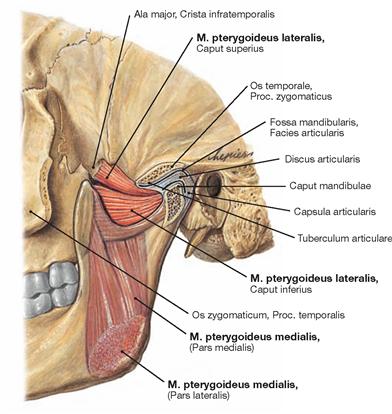

Fig. 8.67 Temporomandibular joint, Articulatio temporomandibularis, M. pterygoideus medialis and M. pterygoideus lateralis, left side; lateral view.

The M. pterygoideus medialis consists of a Pars medialis and a Pars lateralis.![]()

Fig. 8.68 Temporomandibular joint, Articulatio temporomandibularis, and relationship to the M. pterygoideus lateralis, left side; lateral view.

The M. pterygoideus lateralis consists of a Caput superius and a Caput inferius (→ Fig. 8.67).

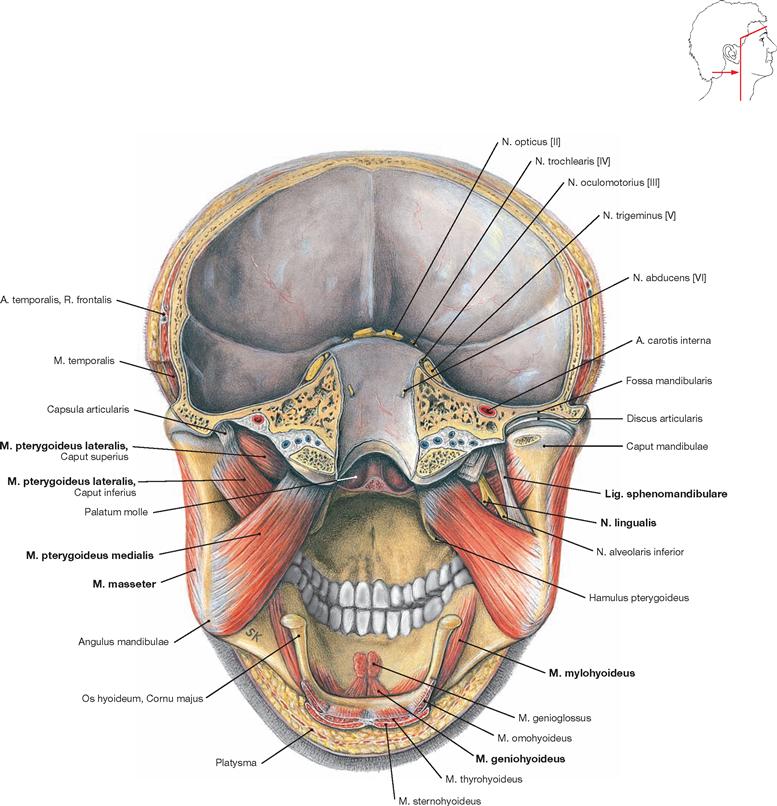

Fig. 8.69 Masticatory muscles, Mm. masticatorii; frontal section at the level of the temporomandibular joint and horizontal section of the skull cap; posterior view.

The bilateral insertion sites of the Mm. masseter and pterygoideus medialis at the Angulus mandibulae are shown. The Mandibula is suspended by these muscles like a swing. On the right side, the Lig. sphenomandibulare between the M. pterygoideus lateralis and the M. pterygoideus medialis as well as the N. lingualis are visible.![]()

Topography

Vessels and nerves of head and neck

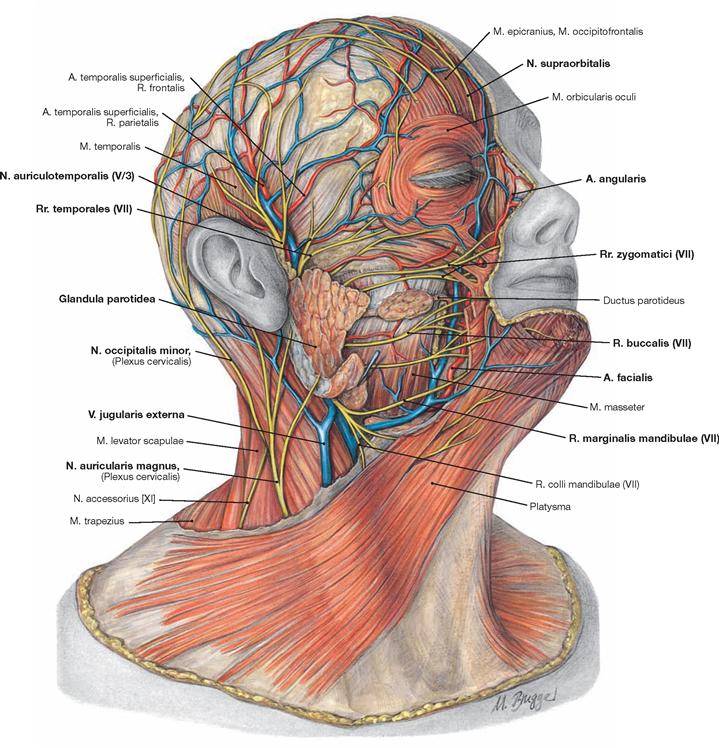

Fig. 8.70 Vessels and nerves of head and neck, lateral superficial regions, right side; lateral view.

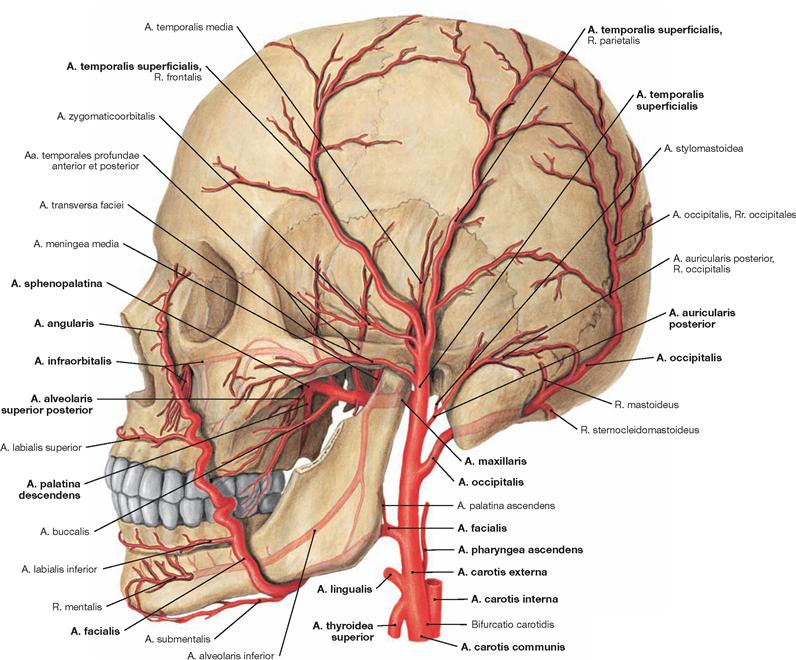

Superficial arteries in the area of the face are the A. facialis and its branches and the R. parietalis and R. frontalis of the A. temporalis superficialis, which originates from the A. carotis externa in the lateral head region. The blood drains from here through identically named veins into the V. jugularis externa.

The terminal branches of the N. facialis [VII] are the superficial nerves radiating from the Plexus intraparotideus located within the Glandula parotidea (Rr. temporales, Rr. zygomatici, Rr. buccales, R. marginalis mandibulae, R. colli mandibulae). In front of the auricle the N. auriculotemporalis, a branch of the N. trigeminus [V], ascends. The N. supraorbitalis, also a branch of the N. trigeminus [V], leaves the orbit and pierces the M. orbicularis oculi.

Neck and occiput receive sensory innervation from branches of the Plexus cervicalis which largely derive from the Punctum nervosum (ERB’s point) at the posterior margin of the M. sternocleidomastoideus: N. transversus colli, N. auricularis magnus, N. occipitalis minor, and Nn. supraclaviculares.

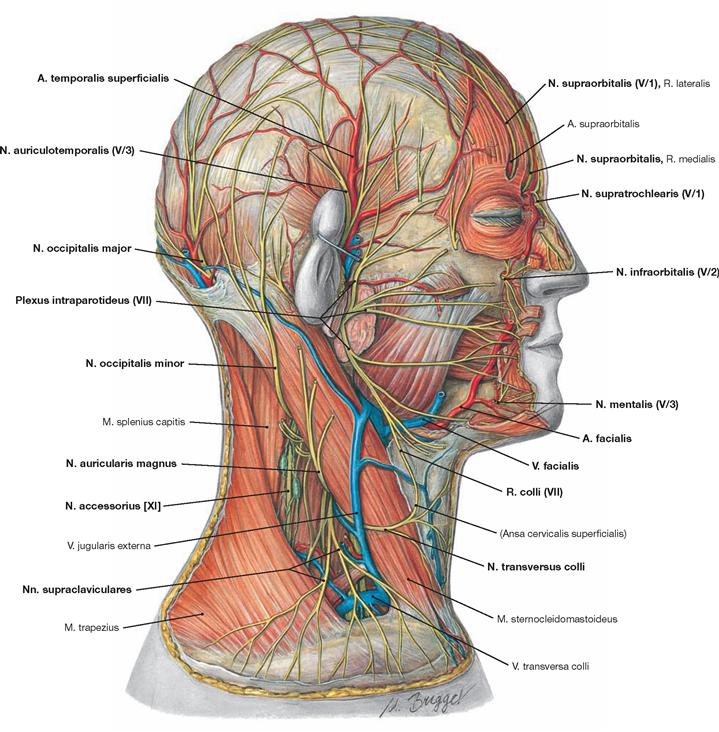

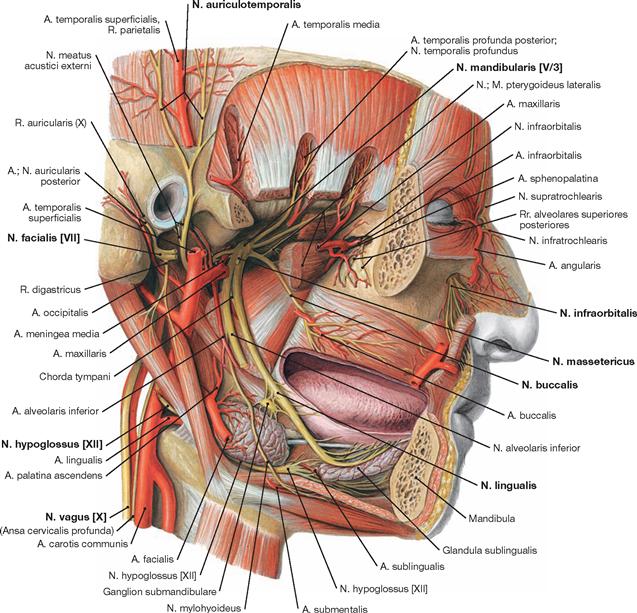

Fig. 8.71 Vessels and nerves of the head and neck, lateral deep regions, right side; lateral view.

Upon removal of the facial muscles and the superficial parts of the Glandula parotidea, the course of the A. facialis and the origin of the terminal branches of the N. facialis derived from the Plexus infraparotideus become visible. Also shown are the terminal sensory branches of the N. trigeminus [V] which originate from its three parts:

• Nn. supraorbitalis and supratrochlearis (from N. ophthalmicus [V/1])

In the lateral triangle of the neck at the posterior side of the M. sternocleidomastoideus, the four cervical branches exit at the ERB’s point:

The N. transversus colli receives motor fibres via the R. colli of the N. facialis [VII] for the innervation of more distal parts of the Platysma. Further, in the lateral triangle of the neck the N. accessorius [XI] runs from the posterior border of the M. sternocleidomastoideus to the anterior border of the M. trapezius. The occiput receives sensory innervation through the N. occipitalis major (branch of the Plexus cervicalis) and blood supply through the A. and V. occipitalis.

Vessels and nerves of the lateral facial region

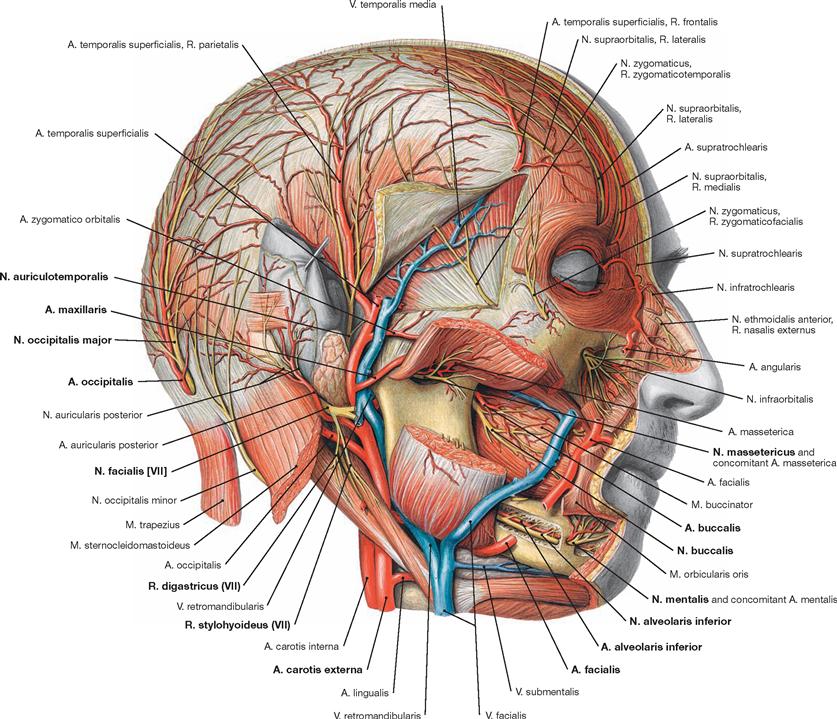

Fig. 8.72 Vessels and nerves of the head, lateral deep regions, right side; lateral view.

Upon removal of large parts of the Glandula parotidea, the structures of the Fossa retromandibularis in the deep lateral head region become visible.

Below the auricle, the undivided stem of the N. facialis [VII] is visible. Shortly after exiting the Foramen stylomastoideum, the facial nerve [VII] provides branches to the M. digastricus, Venter posterior (R. digastricus), to the M. stylohyoideus (R. stylohyoideus), and to the auricular muscles (N. auricularis posterior).

Beneath the Mm. digastricus and stylohyoideus, the Aa. carotides interna and externa ascend. Together with the V. retromandibularis and the N. auriculotemporalis, the A. carotis externa runs in the Fossa retromandibularis and branches into the Aa. occipitalis, auricularis posterior, maxillaris, and temporalis superficialis as well as multiple small branches. The M. masseter was cut and folded backwards to demonstrate its supplying structures located on the back of this muscle (N. massetericus – branch of the N. mandibularis [V/3]; A. masseterica – branch of the A. maxillaris). These supplying structures reach this muscle through the Incisura mandibulae. In the lower facial region, all mimic muscles were removed from the Mandibula; the Canalis mandibularis, which runs within the bone from the Foramen mandibulae to the Foramen mentale, was opened up to display the N. alveolaris inferior and the corresponding artery. At the Foramen mentale, this nerve becomes the N. mentalis.

Below the orbit, the A. facialis was partly removed. This artery continues as A. angularis below the eye and in the orbit it anastomoses with branches of the A. ophthalmica. On top of the M. buccinator, the sensory N. buccalis, a branch of the N. mandibularis [V/3], is visible.

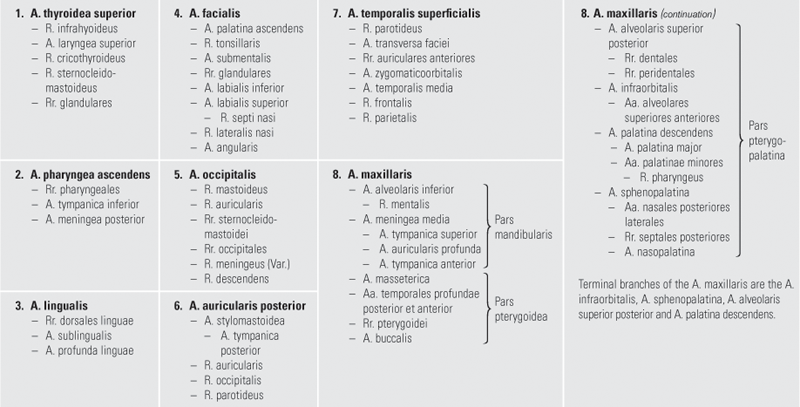

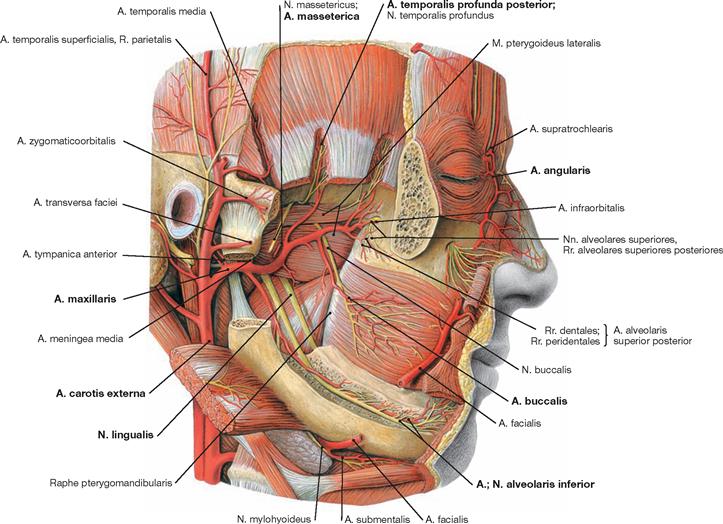

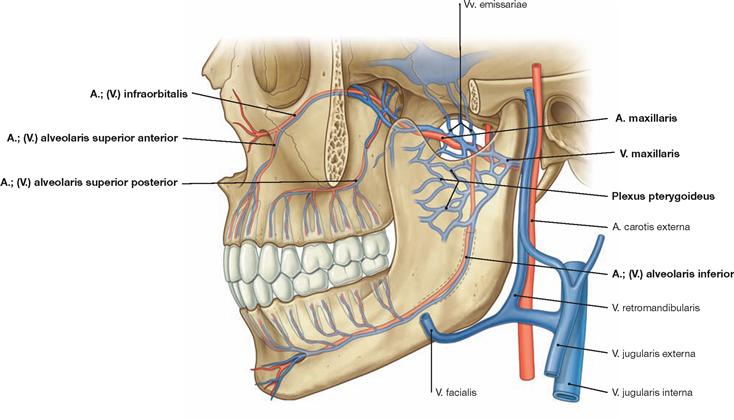

A. maxillaris

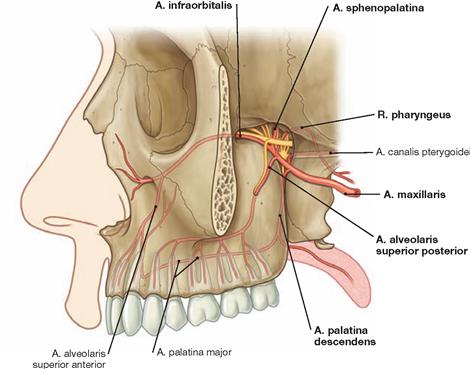

Fig. 8.73 Arteries and nerves of the head, lateral deep regions, right side; lateral view.

In most cases, the A. maxillaris courses behind the Ramus mandibulae. Only rarely does the artery run laterally to the ramus. The A. maxillaris continues through the masticatory muscles, supplies these muscles with blood, and provides branches to the M. buccinator and the Mandibula. Its terminal branches reach the orbit, nose, maxilla, and palate. The A. carotis externa and its branches course through the Fossa retromandibularis. The A. facialis was removed at the level of the Corpus mandibulae. Normally, the pulse of the A. facialis is palpable where it bends around the edge of the Mandibula.

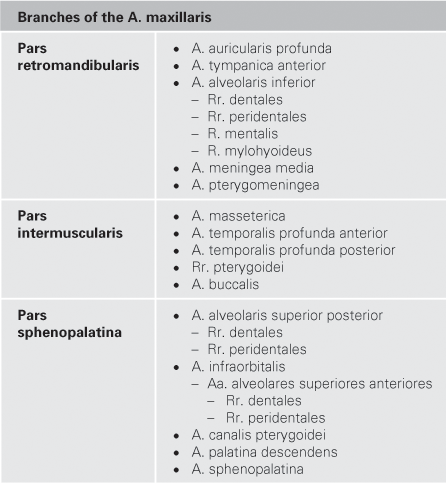

Fig. 8.74 a to d Variations of the course of the A. maxillaris.

a. course of the A. maxillaris medial of the M. pterygoideus lateralis and medial to the N. lingualis and N. alveolaris inferior

b. course of the A. maxillaris between the N. lingualis and N. alveolaris inferior

c. course of the A. maxillaris through a loop of the N. alveolaris inferior

d. branching of the A. meningea media distal of the bifurcation of the A. alveolaris inferior

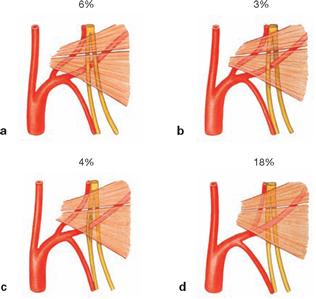

Plexus pterygoideus

Fig. 8.75 Vessels and nerves of the head, lateral deep regions, right side; lateral view.

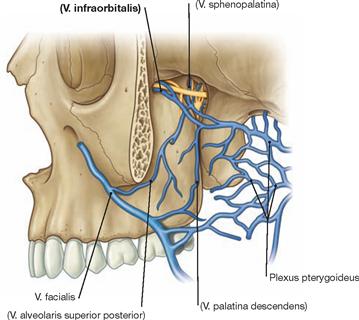

The Plexus pterygoideus drains the venous blood in the region of the masticatory muscles and releases it mainly into the V. maxillaris. The Plexus pterygoideus also connects with the V. facialis via the V. profunda faciei and with the Sinus cavernosus via the V. ophthalmica inferior.

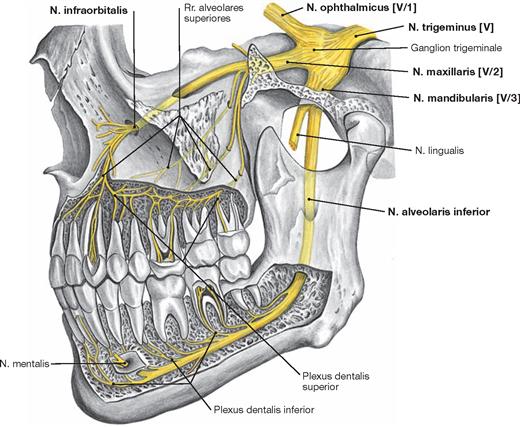

Fig. 8.76 Branching of the N. mandibularis [V/3], right side; frontal view. [9]

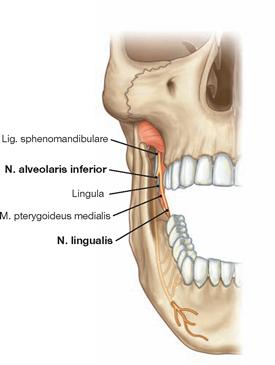

The branching of the N. mandibularis [V/3] (→ Fig. 12.144) into the N. lingualis and N. alveolaris inferior normally occurs between the Lig. sphenomandibulare and the M. pterygoideus medialis, Pars medialis. Then the N. alveolaris inferior turns lateral and enters the Canalis mandibulae lateral of the Lig. sphenomandibulare.

N. mandibularis [V/3]

Fig. 8.77 Arteries and nerves of the head, lateral deepest regions, right side; lateral view.

Upon exiting the Foramen ovale, the N. mandibularis [V/3] divides into the N. lingualis, N. alveolaris inferior, N. buccalis, and the N. auriculotemporalis and sends branches to the masticatory muscles.

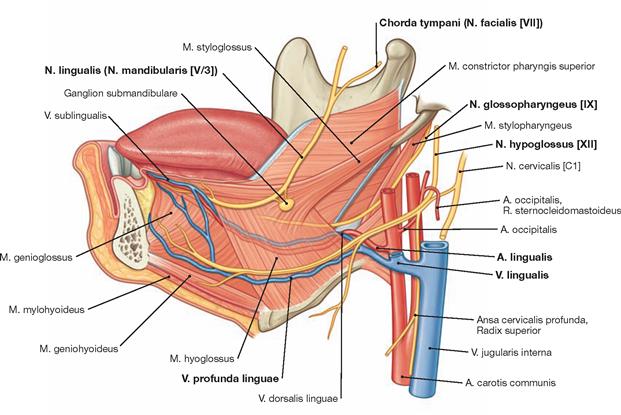

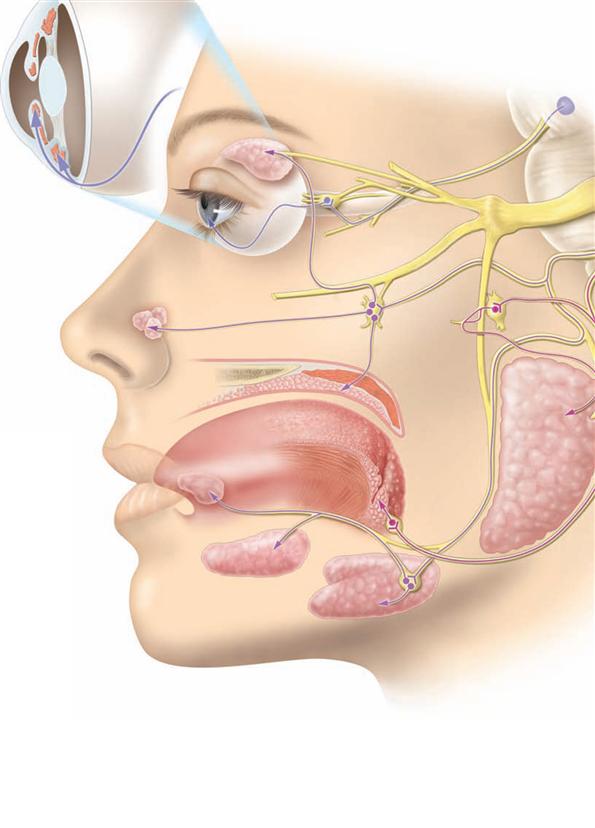

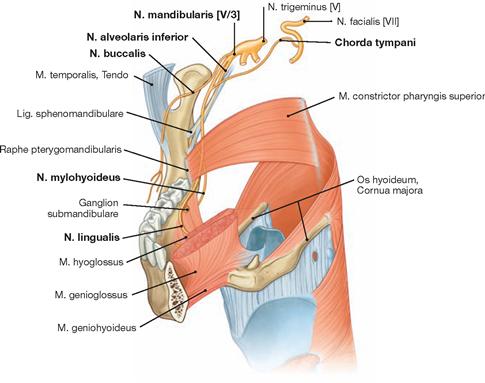

Fig. 8.78 Branching of the N. mandibularis [V/3], right side; frontal view from the left side. [9]

Branching off the N. mandibularis [V/3], the N. lingualis enters the tongue from the lateral side. Shortly after leaving the N. mandibularis [V/3], the lingual nerve is accompanied by the Chorda tympani, which branches off the N. facialis [VII] within the Canalis facialis. The Chorda tympani contains parasympathetic fibres for the Ganglion submandibulare as well as gustatory fibres for the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

Vessels and nerves

Arteries of the head

Fig. 8.79 A. carotis externa (→ p. 53). External carotid artery, A. carotis externa, left side; lateral view (→ p. 52).

The branches of the A. carotis externa are listed in the table (→ p. 52) in their consecutive branching order.

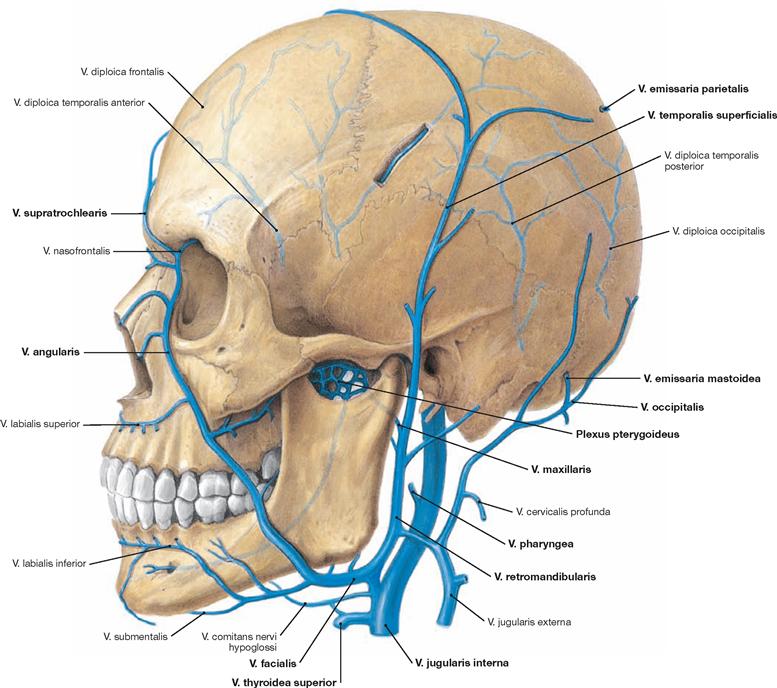

Veins of the head

Fig. 8.80 Internal jugular vein, V. jugularis interna, left side; lateral view.

The V. jugularis interna starts as a dilated extension of the Sinus sigmoideus at the cranial base. This vein drains the blood from the regions of the skull, brain, face, and parts of the neck. The Vv. facialis, lingualis, pharyngea, occipitalis, thyroidea superior, thyroidea media, and Vv. emissariae drain blood from the superficial head region into the V. jugularis interna.

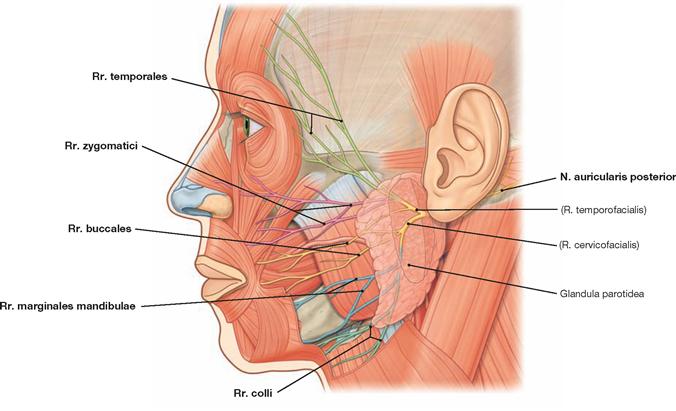

N. facialis [VII]

Fig. 8.81 Terminal branches of the N. facialis [VII] in the face, left side; lateral view. [8]

Within the Glandula parotidea, the N. facialis [VII] (→ Fig. 12.149) creates the Plexus intraparotideus which, for clinical purposes, is divided into a R. temporofacialis (Pars temporofacialis) and a R. cervicofacialis (Pars cervicofacialis). These two parts generate the terminal branches of the N. facialis [VII]: Rr. temporales, zygomatici, buccales, marginales mandibulae, and colli. Projecting dorsally behind the auricle is the N. auricularis posterior, another terminal branch of the N. facialis [VII].

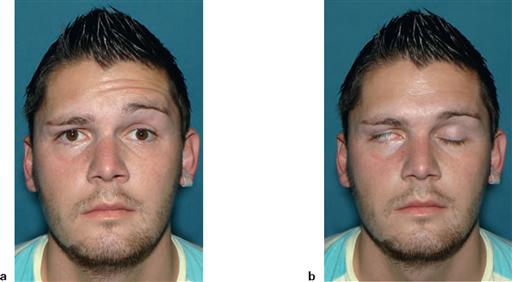

Fig. 8.82 a and b Peripheral palsy of the N. facialis [VII], left side.

a. Upon the request to raise the eyebrows, only the left half of the forehead displays wrinkles (loss of function of the M. occipitofrontalis, sign of peripheral facial nerve palsy).

b. Upon the request to tightly shut both eyes, the eye on the injured side fails to close properly (lagophthalmos). When closing the eyes, the eyeball automatically turns upwards. Because the eyelid on the affected side fails to close properly, the white sclera becomes vis- ible (BELL’s phenomenon).

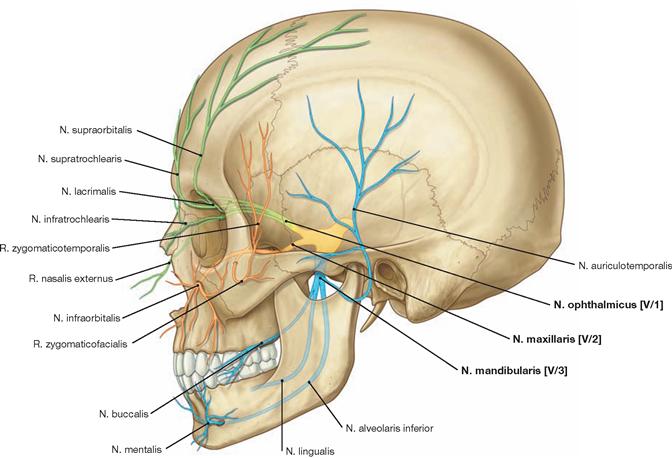

Skin innervation

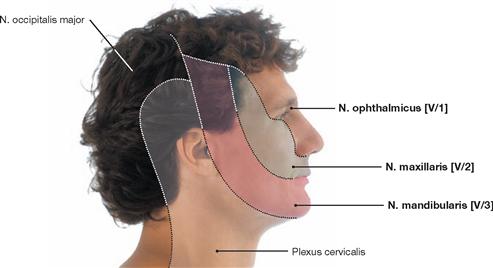

Fig. 8.83 Branches of the N. trigeminus [V], left side; lateral view. [8]

Upon exit from the cranium, the three major branches of the N. trigeminus [V], N. ophthalmicus [V/1], N. maxillaris [V/2], and N. mandibularis [V/3], subdivide into smaller branches in a specific topographic order. Visible branches of the N. ophthalmicus [V/1] are the Nn. supraorbitalis, supratrochlearis, lacrimalis, infratrochlearis, and R. nasalis externus. The N. maxillaris [V/2] provides the Nn. infraorbitalis and zygomaticus with its Rr. zygomaticotemporalis and zygomaticofacialis as shown in the image. Branches of the N. mandibularis [V/3] are the Nn. buccalis, lingualis, alveolaris inferior, and auriculotemporalis. When leaving the Canalis mandibulae, the N. mentalis represents the terminal branch of the N. alveolaris inferior.

Fig. 8.84 Skin innervation of the head and neck, right side; lateral view.

The view from ventral is depicted in → Figure 12.146.

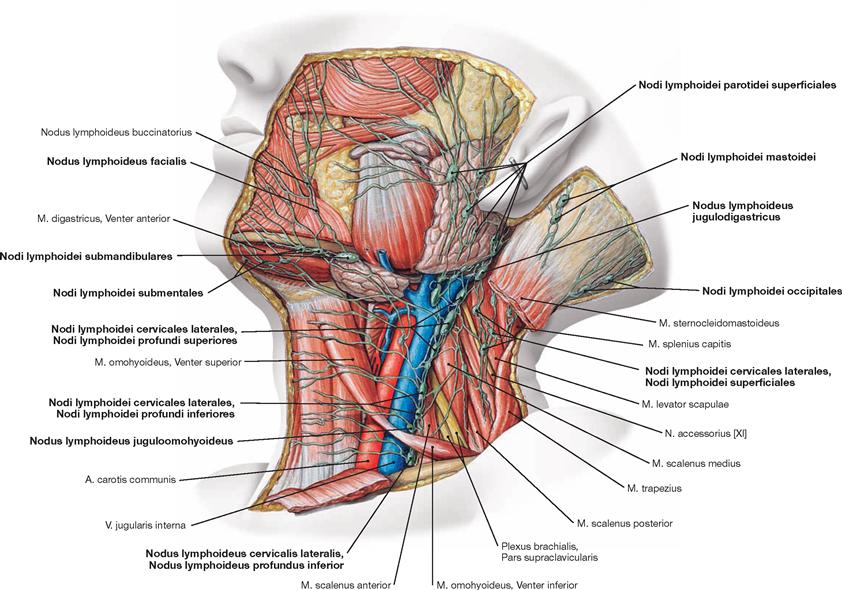

Lymph vessels and lymph nodes of the head

Fig. 8.85 Superficial lymph vessels, Vasa lymphatica superficialia, and lymph nodes, Nodi lymphoidei, of the head and neck of a child, left side; lateral view.

The regional Nodi lymphoidei submentales, submandibulares, parotidei, mastoidei, and occipitales collect the lymphatic fluid of the face, scalp, and occiput. From here, the lymph is drained into superficial (Nodi lymphoidei cervicales laterales superficiales) and deep cervical lymph nodes (Nodi lymphoidei cervicales laterales profundi superiores and inferiores, → Fig. 11.75).

An important deep cervical lymph node is the Nodus lymphoideus jugulodigastricus, located between the anterior margin of the M. sternocleidomastoideus and the mandibular angle at the lower border of the Glandula parotidea.

The Nodi lymphoidei parotidei are divided into superficial (Nodi lymphoidei parotidei superficiales) and deep (Nodi lymphoidei parotidei profundi) nodes. The latter include the Nodi lymphoidei preauriculares, infraauriculares, and intraglandulares. In addition, there are isolated facial lymph nodes (Nodi lymphoidei faciales: Nodi lymphoidei buccinatorius, nasolabialis, mandibularis, malaris) and lymph nodes of the tongue (Nodi lymphoidei linguales).

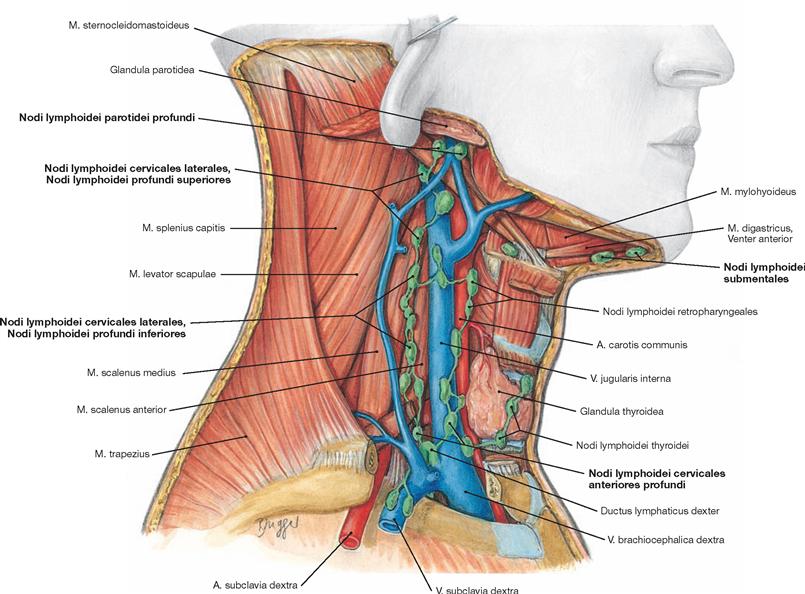

Deep lymph vessels of the neck

Fig. 8.86 Deep lymph nodes of the neck, Nodi lymphoidei cervicales profundi, right side; lateral view.

Cervical lymph nodes of both the anterior (Nodi lymphoidei cervicales anteriores) and lateral (Nodi lymphoidei cervicales laterales) aspects of the neck are divided into a superficial and deep lymph node compartment. The Nodi lymphoidei infrahyoidei with the Nodi lymphoidei prelaryngei, the Nodi lymphoidei thyroidei, Nodi lymphoidei pretracheales, Nodi lymphoidei paratracheales, and Nodi lymphoidei retropharyngeales constitute the anterior deep cervical lymph nodes (Nodi lymphoidei cervicales anteriores profundi).

The lateral deep cervical lymph nodes (Nodi lymphoidei cervicales laterales profundi) are divided into an upper group (Nodi lymphoidei profundi superiores), composed of the Nodus lymphoideus jugulodigastricus, Nodus lymphoideus lateralis and Nodus lymphoideus anterior, and a lower group (Nodi lymphoidei profundi inferiores) with the Nodus lymphoideus juguloomohyoideus, Nodus lymphoideus lateralis, and Nodi lymphoidei anteriores. In addition, there are the Nodi lymphoidei supraclaviculares and the Nodi lymphoidei accessorii (in association with the N. accessorius [XI]) with the Nodi lymphoidei retropharyn- geales.

Nose

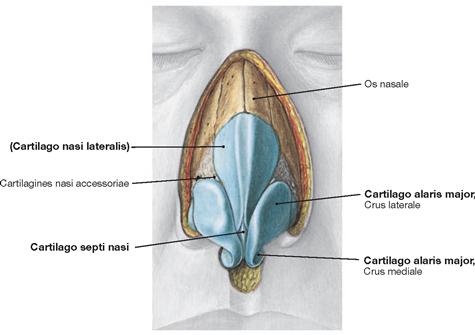

Nasal skeleton

Fig. 8.87 Nasal skeleton; frontal view.

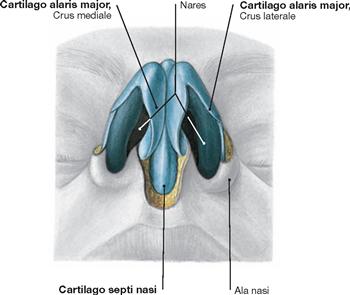

The nasal skeleton consists of a bony and a cartilaginous part. Connective tissue fixes the cartilaginous part to the Apertura piriformis which is composed of the Os nasale and Maxilla. The individual elements consist of hyaline cartilage and are linked by connective tissue. The upper lateral or triangular cartilage (Cartilago nasi lateralis, Cartilago triangularis) forms the roof; the nasal tip or major alar cartilage (Cartilago alaris major) with a Crus laterale and a Crus mediale creates the nasal wings. In addition, two smaller alar cartilages (Cartilagines alares minores) exist bilaterally. At its bottom and central part, the cartilaginous part of the nasal septum (Cartilago septi nasi) supports the nasal skeleton.

Fig. 8.88 Nasal cartilages, Cartilagines nasi; inferior view.

The view from below shows the nasal orifices (Nares) which are delineated by the two crura of the major alar cartilage (Crus mediale and Crus laterale of the Cartilago alaris major). In the central lower region, the cartilaginous part of the nasal septum is visible (Cartilago septi nasi).

Fig. 8.89 Nasal skeleton; frontal view from the right side.

The cartilaginous nasal skeleton attaches to the Apertura piriformis by connective tissue. The Cartilagines nasi laterales, alares majores, alares minores and the Cartilago septi nasi are visible. There is connective tissue within the non-cartilaginous nasal areas.

Nasal septum

Fig. 8.90 Nasal septum, Septum nasi; view from the right side.

The Cartilago septi nasi forms the frontal part of the nasal septum and extends as a long cartilaginous Proc. posterior between the bony parts of the nasal septum (top), composed of the Lamina perpendicularis of the Os ethmoidale, and the Vomer (bottom).

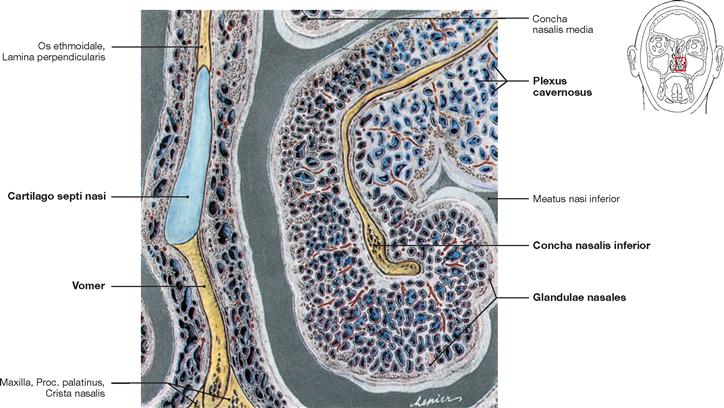

Fig. 8.91 Inferior nasal concha, Concha nasalis inferior, left side; frontal section at the level of the initial part of the Proc. posterior of the Cartilago septi nasi; frontal view.

This section demonstrates the thin bony skeleton of the inferior nasal concha (Concha nasalis inferior) which is covered by a vascular plexus (Plexus cavernosus) composed of a network of specialised arteries and veins. Ciliated epithelium and interspersed serous glands (Glandulae nasales) cover the surface of the nasal concha.

Nasal cavity

Fig. 8.92 Lateral wall of the nasal cavity, Cavitas nasi, left side; lateral view.

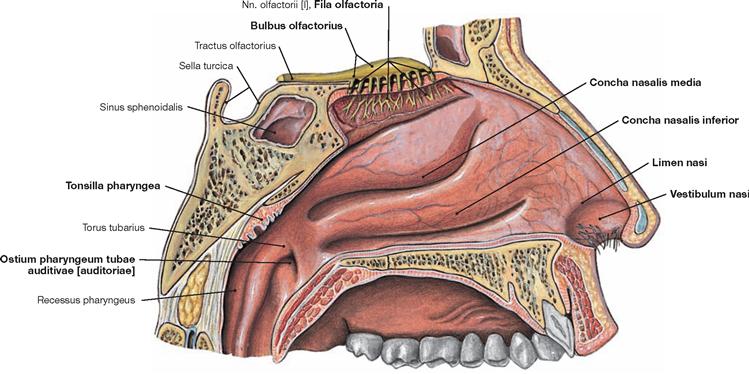

The lateral wall of the nasal cavity is mainly occupied by the inferior (Concha nasalis inferior) and middle nasal conchae (Concha nasalis media). The superior nasal concha (Concha nasalis superior) is small and located in close vicinity to the olfactory region at the nasal roof. Here, the Fila olfactoria of the Bulbus olfactorius penetrate the Lamina cribrosa and reach the neighbouring mucosa, including the mucosa of the upper nasal concha.

Keratinised stratified squamous epithelium covers the Vestibulum nasi. At the Limen nasi, the epithelial layer transforms into non-keratinised stratified squamous epithelium and then into ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium. An imaginary line from the inferior nasal concha projects to Ostium pharyngeum of the Tuba auditiva. Above the Ostium at the pharyngeal roof lies Tonsilla pharyngea.

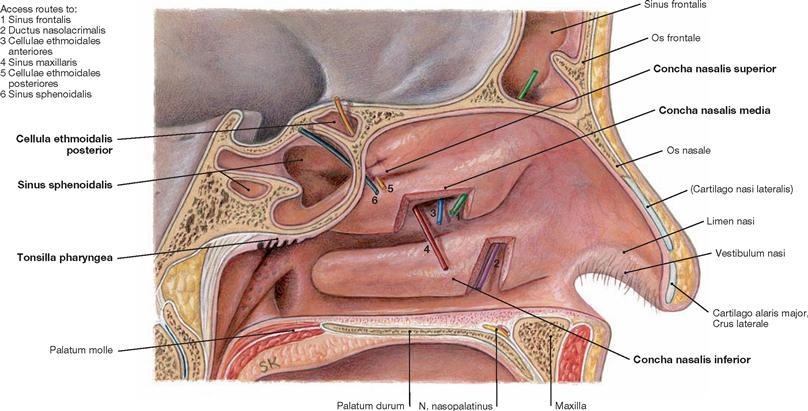

Fig. 8.93 Nasal cavity, Cavitas nasi, and entrance into the paranasal sinuses, Sinus paranasales, left side; view from the right side.

Beneath the anterior third of the inferior nasal concha, the Ductus nasolacrimalis opens into the lower nasal meatus (purple probe). Beneath the middle nasal concha, the openings of the Sinus frontalis (green probe), Sinus maxillaris (red probe), and Cellulae ethmoidales anteriores (blue probe) are located. Beneath and behind the superior nasal concha, the Cellulae ethmoidales posteriores (yellow probe) and the Sinus sphenoidalis (dark blue probe) open into the nasal cavity.

Paranasal sinuses

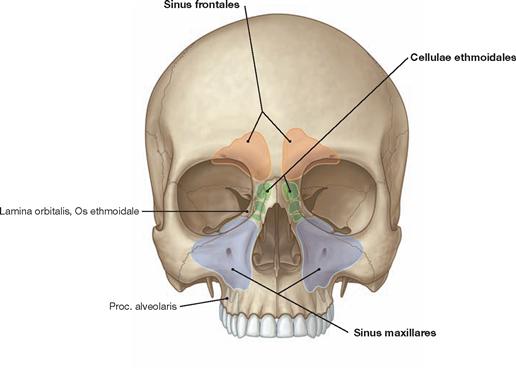

Fig. 8.94 Projection of the paranasal sinuses onto the skull; frontal view. [8]

The projections of the Sinus frontales and maxillares as well as the Cellulae ethmoidales are shown.

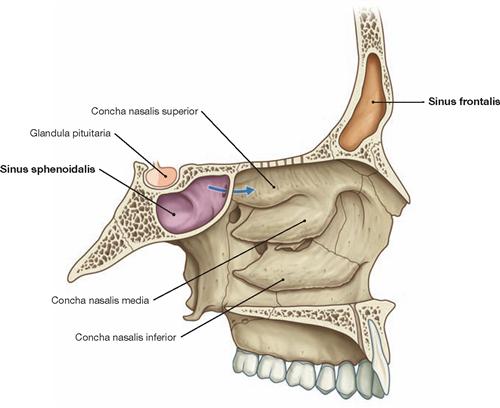

Fig. 8.95 Location of the Sinus frontalis and Sinus sphenoidalis in the skull, right side; view from the left side. [8]

The Sinus sphenoidalis is in close topographic relationship to the pituitary gland (Glandula pituitaria).

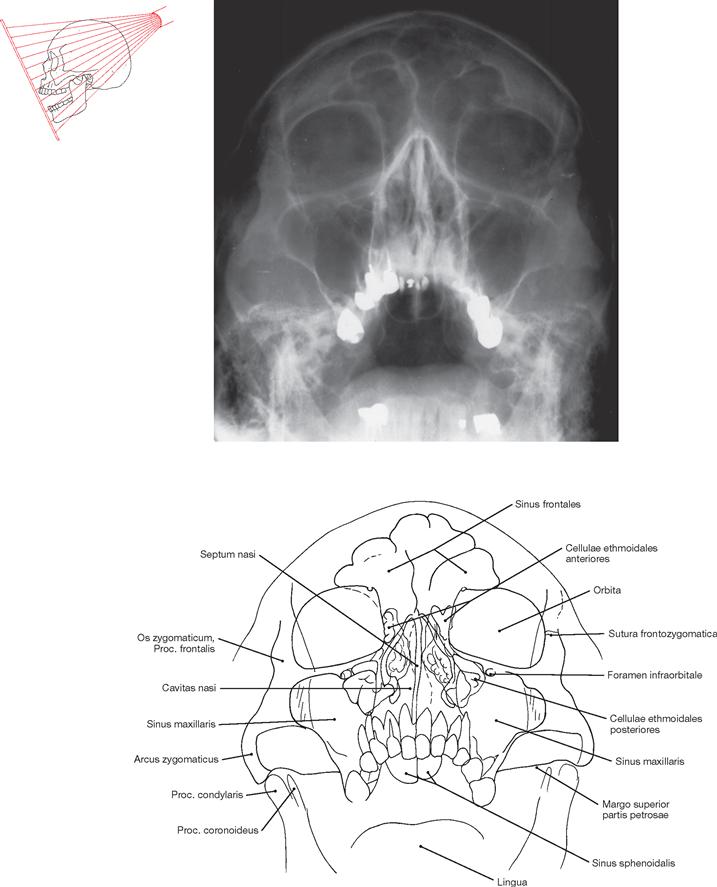

Paranasal sinuses, radiography

Fig. 8.96 Paranasal sinuses, Sinus paranasales; radiograph of the skull with opened mouth in posterior-anterior (PA) beam projection.

Paranasal sinuses

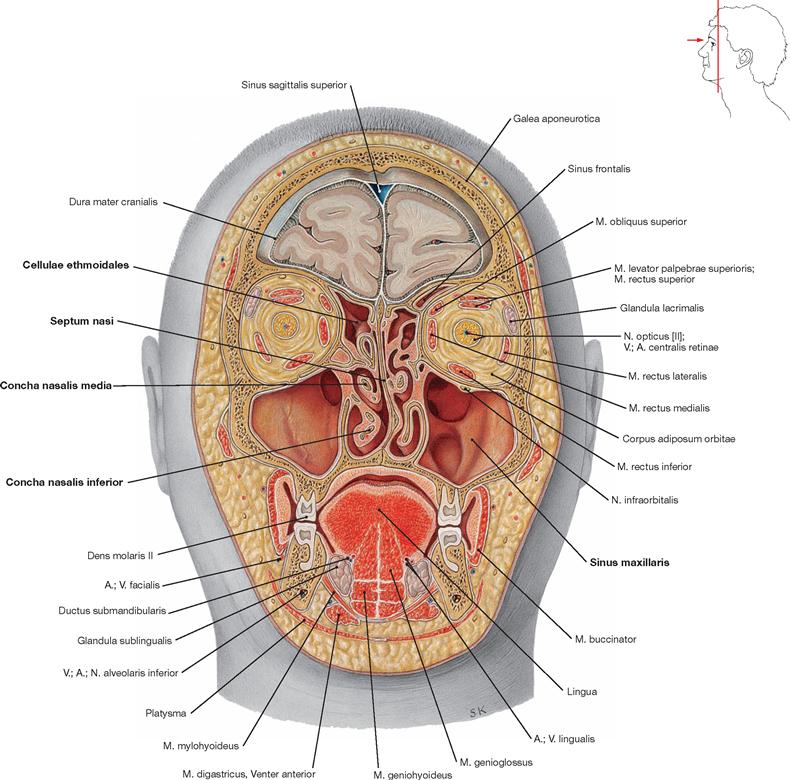

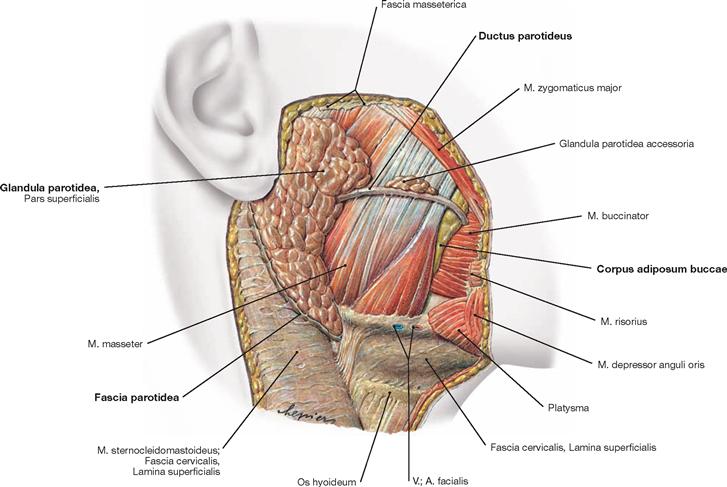

Fig. 8.97 Frontal section through the head at the level of the second upper molar; frontal view.

This section emphasises the individual bilateral differences in the formation of the sectioned paranasal sinuses. On both sides, the differently shaped Sinus maxillares display variable degrees of compartmentalisation. The nasal septum deviates to the left side (septum deviation). As a result, the lower and middle nasal conchae on the right side are markedly more developed than on the left side. The ethmoidal cells show differences in shape between the right and left side. In the left supraorbital region, part of the Sinus frontalis is visible.

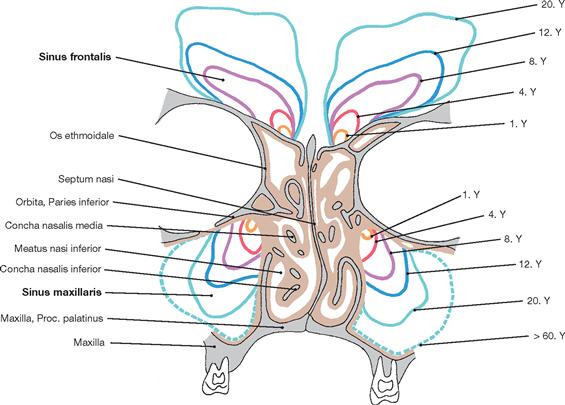

Development and clinics of the paranasal sinuses

Fig. 8.98 Development of the maxillary and frontal sinuses. Y: year of life.

At about 5 years of age, the developing frontal sinus reaches the upper margin of the orbit.

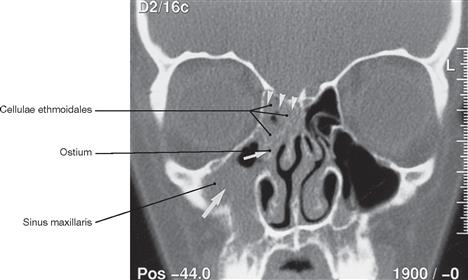

Fig. 8.99 Chronic sinusitis; coronal computed tomography (CT) of the paranasal sinuses; white arrows indicate a swelling of the inflamed mucosa in the right maxillary sinus and the ostium, while white arrow heads point to a swelling of the ethmoidal cells. [17]

Paranasal sinuses

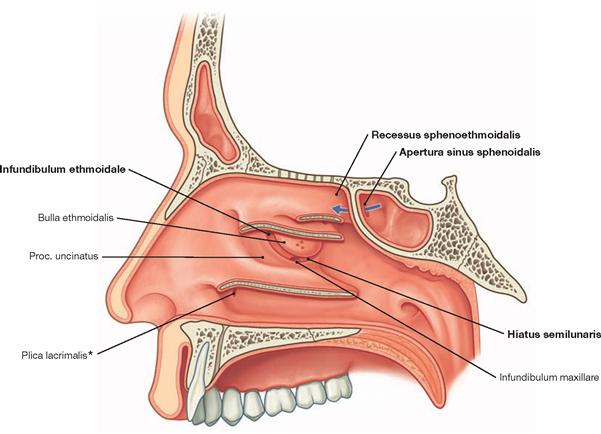

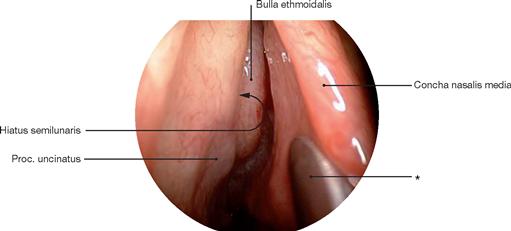

Fig. 8.100 Lateral nasal wall, right side; view from the left side; nasal conchae separated from the wall at the base. [8]

The Ductus nasolacrimalis opens into the lower nasal passage via the Plica lacrimalis (HASNER’s valve). Beneath the middle nasal concha, the Hiatus semilunaris is shown. The Bulla ethmoidalis and the Proc. uncinatus are located above and below the Hiatus semilunaris, respectively. Posterior to the superior nasal concha the Recessus sphenoethmoidalis with the opening of the Sinus sphenoidalis (Apertura sinus sphenoidalis, blue arrow) is located.

* HASNER’s valve

Arteries of the nasal cavity

Fig. 8.101 Nasal cavity, Cavitas nasi, left side; transnasal endoscopy with 30° optics.

The examiner views the head of the middle nasal concha (Concha nasalis media).

* spatula

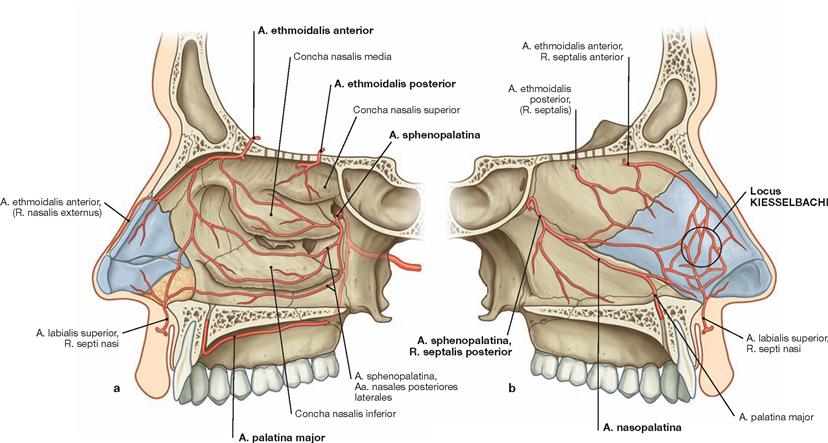

Fig. 8.102 a and b Arteries of the nasal cavity. [8]

The A. carotis externa provides the arterial supply to the nose. The Aa. ethmoidales anterior and posterior from the A. ophthalmica reach the lateral wall of the nose and the nasal septum by traversing through the anterior and posterior part of the Os ethmoidale. As a terminal branch of the A. maxillaris, the A. sphenopalatina gains access to the nasal cavity through the Foramen sphenopalatinum. There are anastomoses via arterial vessels of the lip to the A. facialis. At the nasal septum, the A. sphenopalatina becomes the A. nasopalatina which passes through the Canalis incisivus to reach the oral cavity where it anastomoses with the A. palatina major. The KIESSELBACH’s area, an arteriovenous plexus, is supplied by the A. nasopalatina and the Aa. ethmoidales anterior and posterior.

Veins and nerves of the nasal cavity

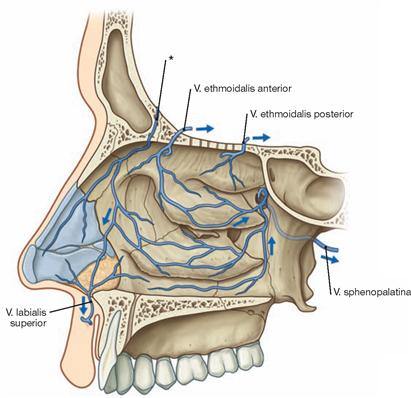

Fig. 8.103 Veins of the nasal cavity, right side; view onto the lateral nasal wall. [8]

The blood is drained via the Vv. ethmoidales anterior and posterior to the Sinus cavernosus at the base of the skull, via the V. sphenopalatina to the Plexus pterygoideus in the Fossa infratemporalis, and via the connection to the Vv. labiales to the V. facialis.

* connecting vein to the Sinus sagittalis superior via the Foramen caec um (only present during childhood)

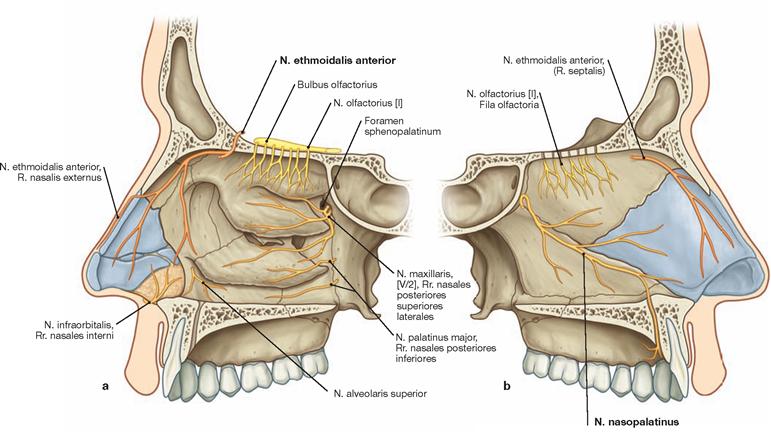

Fig. 8.104 a and b Innervation of the nasal cavity. [8]

Sensory innervation of the nasal mucosa is provided by branches of the N. trigeminus [V]: N. ophthalmicus [V/1] → N. ethmoidalis anterior and N. maxillaris [V/2] → Rr. nasales, N. nasopalatinus. The N. olfactorius [I] innervates the olfactory area. The N. nasopalatinus runs alongside the nasal septum through the Canalis incisivus, and innervates the mucosal area of the hard palate that stretches from the backside of the incisors to the canine teeth.

Mouth and oral cavity

Oral cavity

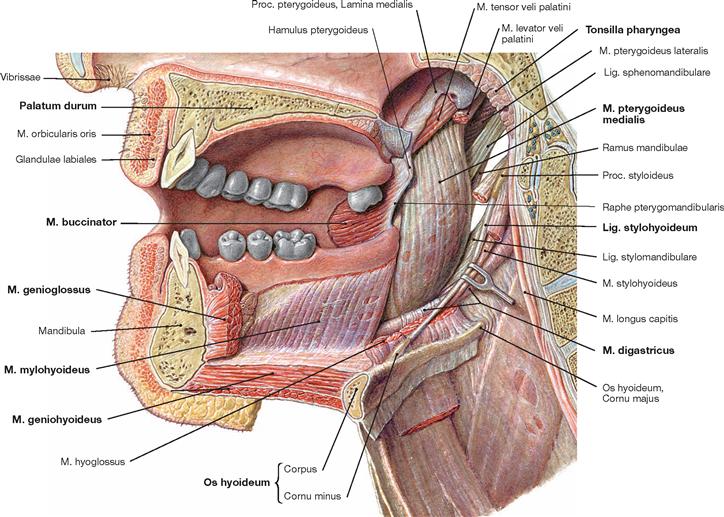

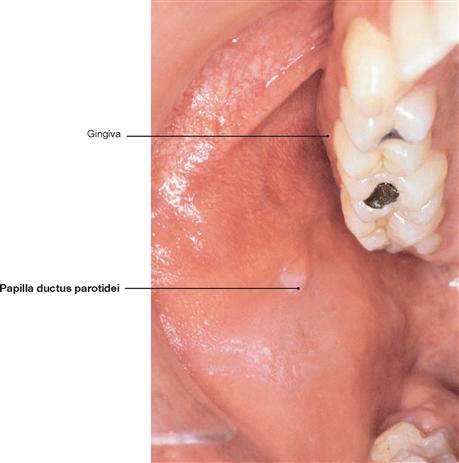

Fig. 8.105 Oral cavity, Cavitas oris, right side; view from the left side.

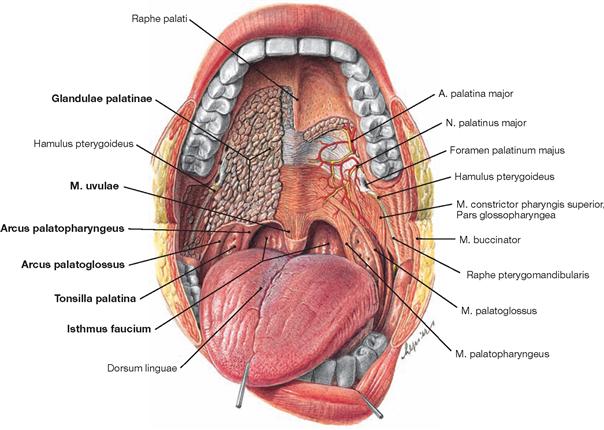

The margins of the oral cavity are the lips (anterior), the cheeks (lateral), the muscular floor of the mouth (bottom, caudal), and the palate (top, cranial).

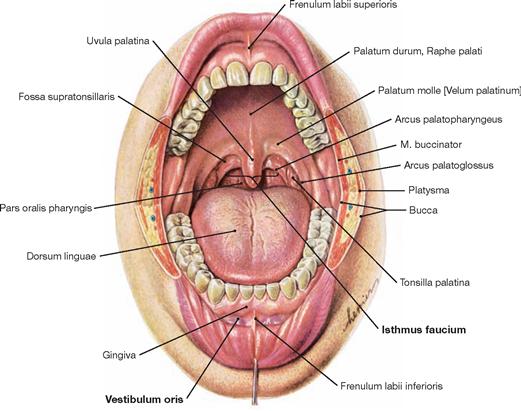

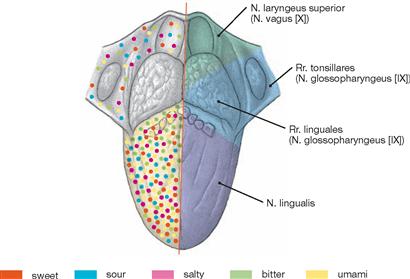

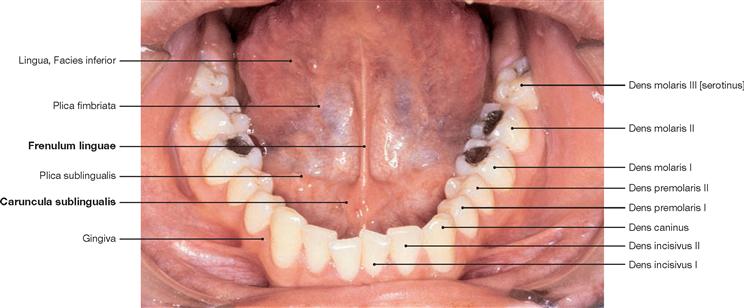

Fig. 8.106 Oral cavity; Cavitas oris; frontal view; mouth open.

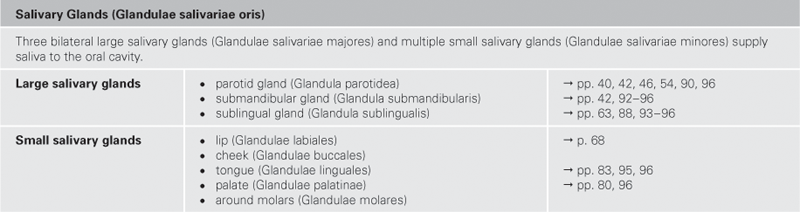

The oral opening (Rima oris) represents the entrance to the digestive tract and the oral cavity. The latter is divided into a vestibule (Vestibulum oris) and the cavity proper (Cavitas oris propria). The borders of the Vestibulum oris are the lips and cheeks at the outside and the alveolar processes and teeth at the inside. With the occlusion of teeth, a space behind the last molar tooth on each side (Spatium retromolare) allows access to the oral cavity. In the region of the oropharyngeal isthmus (Isthmus faucium) the oral cavity becomes the Pars oralis of the Pharynx (Oropharynx). The excretory ducts of numerous smaller salivary glands and those of the three paired large salivary glands all drain into the Vestibulum oris and the Cavitas oris propria. The body of the tongue (Corpus linguae) fills large parts of the inside of the oral cavity.

Dental arches

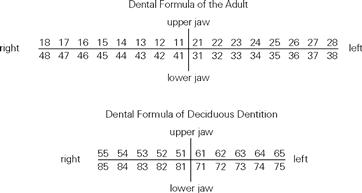

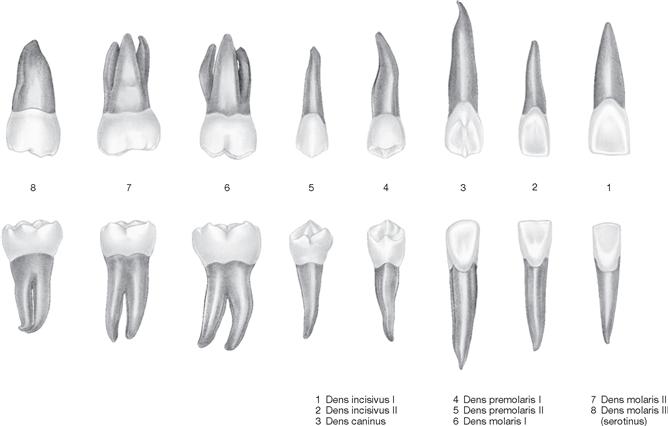

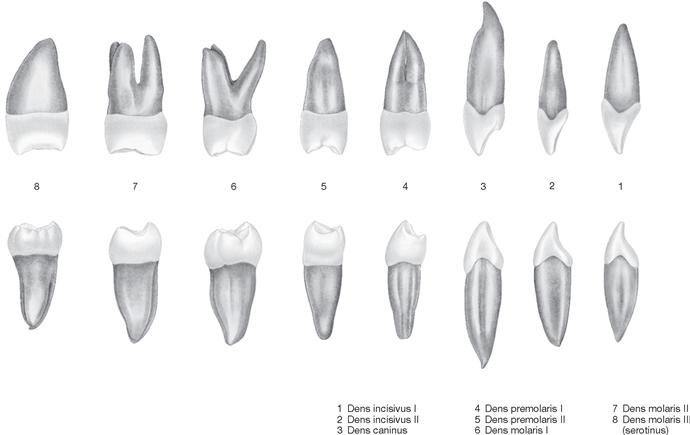

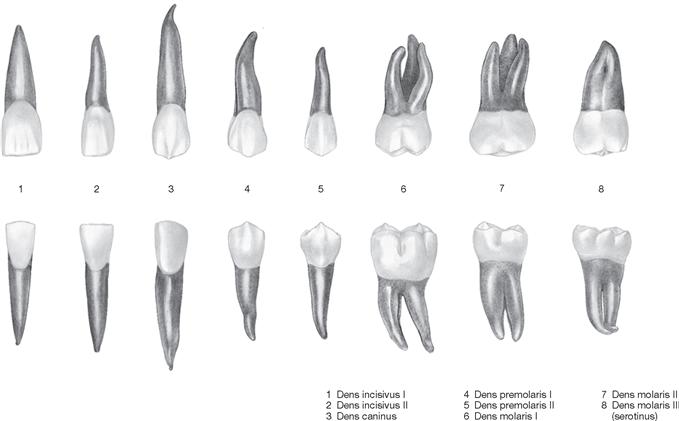

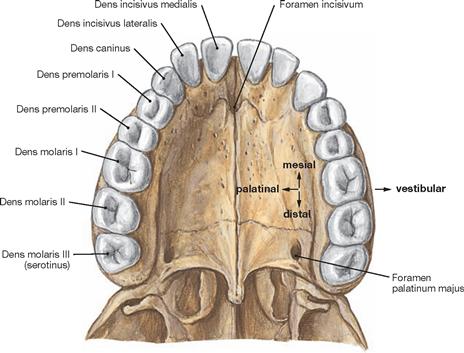

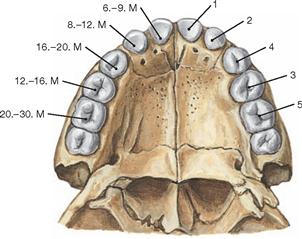

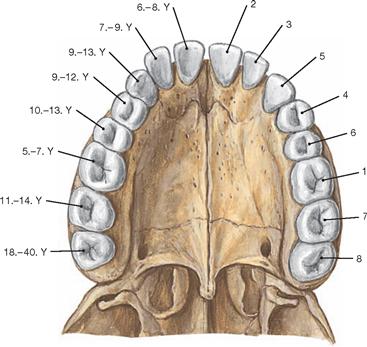

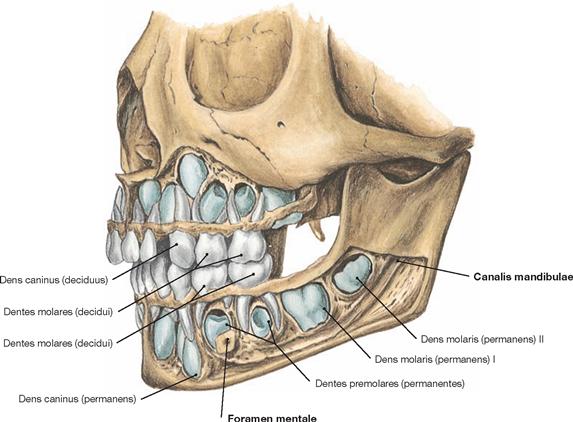

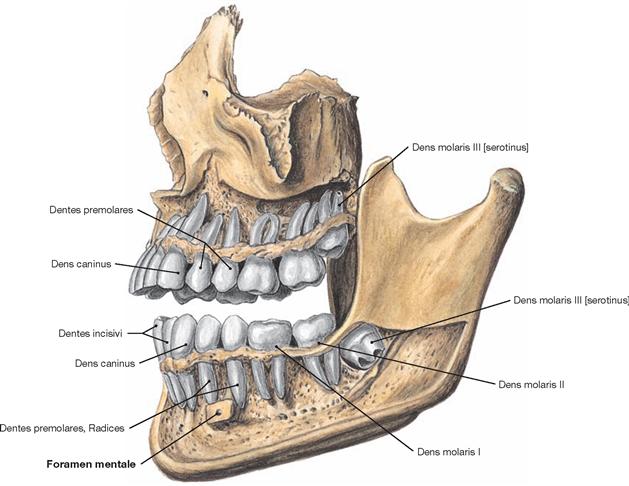

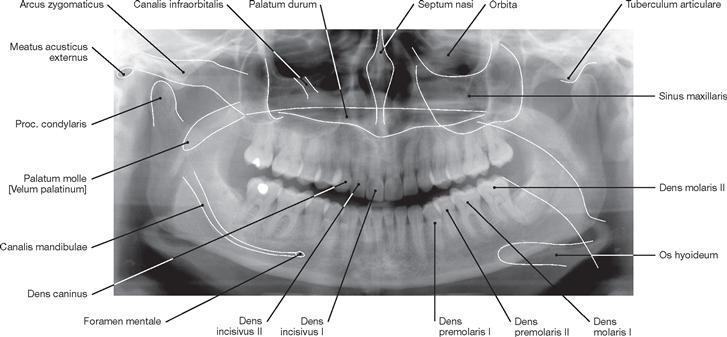

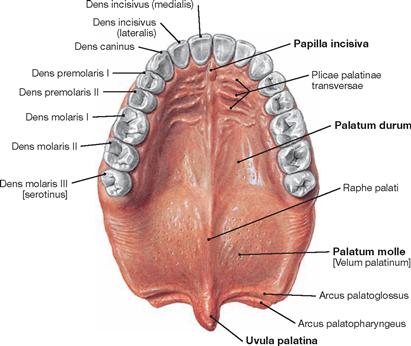

Fig. 8.107 Upper dental arch, Arcus dentalis maxillaris [superior].

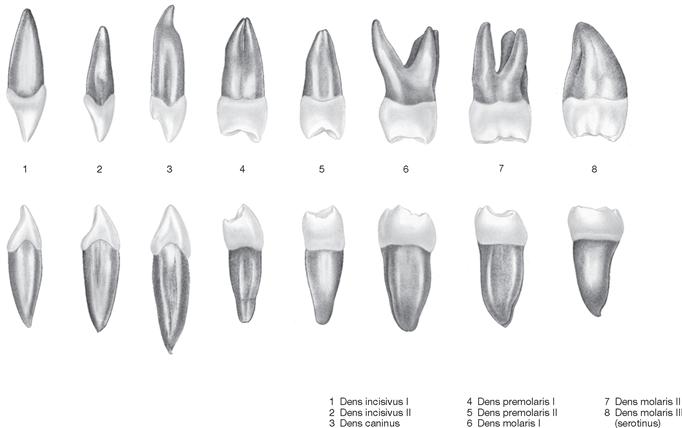

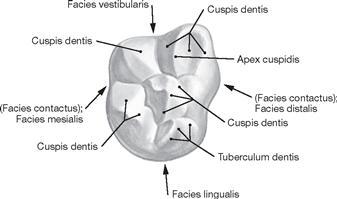

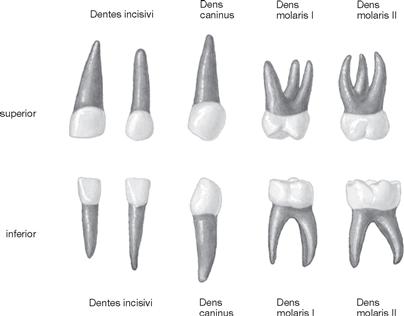

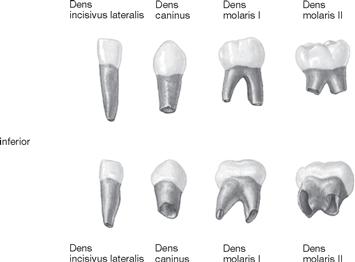

The teeth (Dentes) are arranged in two dental arches, the upper (Arcus dentalis maxillaris or superior) and the lower dental arch (Arcus dentalis mandibularis or inferior), and are anchored in the upper and lower jaw. Dentition in the human is heterodont; the teeth come in characteristic shapes as incisors (Incisivi), canines (Canini), premolars (Premolares), and molars (Molares). Incisors and canine teeth are also named front teeth, whereas premolars and molars are lateral teeth.

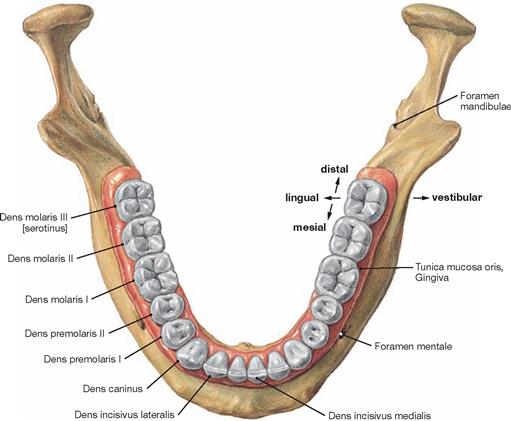

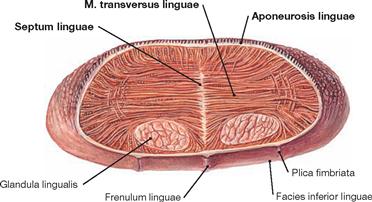

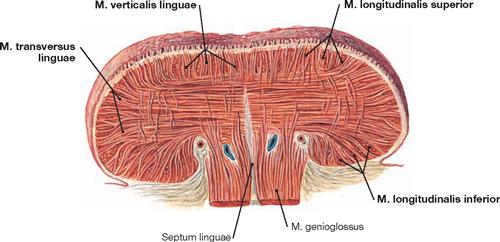

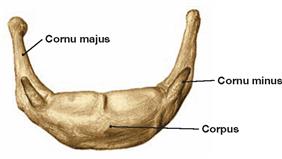

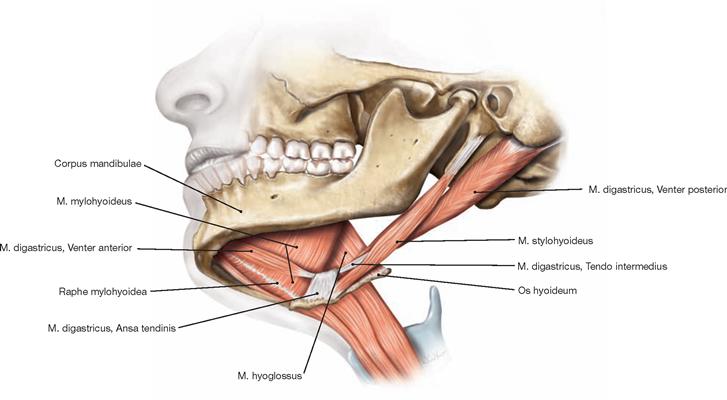

Fig. 8.108 Lower dental arch, Arcus dentalis mandibularis [inferior].