3 Pathological and other abnormal gaits

Although some variability is present in normal gait, particularly in the use of the muscles, there is an identifiable ‘normal pattern’ of walking and a ‘normal range’ can be defined for all of the variables which can be measured. Pathology of the locomotor system frequently produces gait patterns which are clearly ‘abnormal’. Some of these abnormalities can be identified by eye, but others can only be identified by the use of appropriate measurement systems.

In order for a person to walk, the locomotor system must be able to accomplish four things:

1. Each leg in turn must be able to support the body weight without collapsing

2. Balance must be maintained, either statically or dynamically, during single leg stance

3. The swinging leg must be able to advance to a position where it can take over the supporting role

4. Sufficient power must be provided to make the necessary limb movements and to advance the trunk.

In normal walking, all of these are achieved without any apparent difficulty and with a modest energy consumption. However, in many forms of pathological gait they can be accomplished only by means of abnormal movements, which usually increase the energy consumption, or by the use of walking aids such as canes, crutches or orthoses (calipers and braces). If even one of these four requirements cannot be met, the subject is unable to walk.

The pattern of gait is the outcome of a complex interaction between the many neuromuscular and structural elements of the locomotor system. Abnormal gait may result from a disorder in any part of this system, including the brain, spinal cord, nerves, muscles, joints and skeleton. Abnormal gait may also result from the presence of pain, so that although a person is physically capable of walking normally, they find it more comfortable to walk in some other way.

The term limp is commonly used to describe a wide variety of abnormal gait patterns. However, dictionary definitions are unhelpful, a typical one being ‘to walk lamely’. Since the word has no clearly defined scientific meaning, it should only be used with caution in the context of gait analysis. The most appropriate use of the word is probably for a gait abnormality involving some degree of asymmetry, which is readily apparent to an untrained observer.

Since gait is the end result of a complicated process, a number of different original problems may manifest themselves in the same abnormality of gait. For this reason, the abnormal gait patterns will be described separately from the pathological conditions which cause them. This chapter describes, in some detail, the most common abnormal gait patterns. This is followed by a description of the use of walking aids such as canes and walkers, and treadmill gait.

Specific gait abnormalities

The following sections are based on a manual of lecture notes for student orthotists published by New York University (1986). Despite being over 25 years old, the manual includes a very useful list of common gait abnormalities, all of which can be identified by eye, which still hold today. The manual criticises the common practice of identifying gait abnormalities by their pathological cause, for example ‘hemiplegic gait’, which immediately suggests that all hemiplegics walk in the same way, which is far from true, and also neglects the changes in gait which may occur with the passage of time, or result from treatment. The manual suggests that it is preferable to use purely descriptive terms, such as ‘excessive medial foot contact’. This practice will be adopted in the following sections. Some of the gait abnormalities described in the New York University publication apply only to the gait of subjects wearing orthoses; these descriptions have been omitted from the present text.

The pathological gait patterns to be described may occur either alone or in combination. If in combination, they may interact, so that the individual gait modifications do not exactly fit the description. The list that follows is not exhaustive; a subject may use a variation of one of the general patterns or may use another gait pattern which is not listed here.

When studying a pathological gait, particularly one which does not appear to fit into one of the standard patterns, it is helpful to remember that an abnormal movement may be performed for one of two reasons:

1. The subject has no choice, the movement being ‘forced’ on them by weakness, spasticity or deformity

2. The movement is a compensation, which the subject is using to correct for some other problem, which therefore needs to be identified.

Lateral trunk bending

Bending the trunk towards the side of the supporting limb during the stance phase is known as lateral trunk bending, ipsilateral lean or, more commonly, a Trendelenburg gait. The purpose of the manoeuvre is generally to reduce the forces in the abductor muscles and hip joint during single leg stance.

Lateral trunk bending is best observed from the front or the back. During the double support phase, the trunk is generally upright but as soon as the swing leg leaves the ground, the trunk leans over towards the side of the stance phase leg, returning to the upright attitude again at the beginning of the next double support phase. The trunk bending may be unilateral, being restricted to the stance phase of one leg, or it may be bilateral, the trunk swaying from one side to the other, to produce a gait pattern known as waddling.

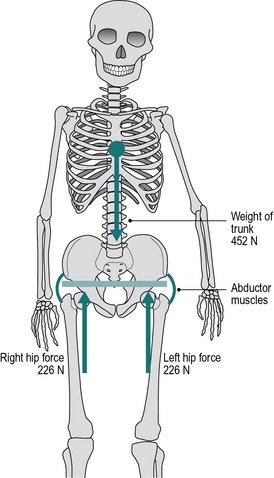

In the examples which follow, the weight of the trunk is 452 N, corresponding to a mass of 46 kg, and the weight of the right leg is 147 N, corresponding to a mass of 15 kg. As explained in Chapter 1 (p. 000), weight is a force, calculated by multiplying an object's mass by the acceleration due to gravity, 9.81 m/s2.

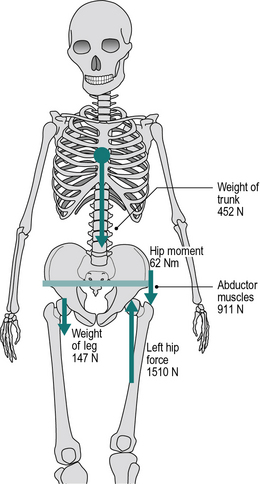

Figure 3.1 shows a schematic of the trunk, pelvis and hip joints when standing on both legs. The abductor muscles are inactive and the weight of the trunk is divided equally between the two hip joints. Figure 3.2 shows what happens in a normal individual when the right foot is lifted off the ground: the force through the left hip joint increases by a factor of six, from 226 N (23 kgf or 51 lbf) to 1510 N (154 kgf or 339 lbf). This increase in force is made up of three components:

1. The whole of the weight of the trunk is now supported by the left hip joint, instead of being shared between the two hips which produces an anti-clockwise moment

2. The weight of the right leg is now taken by the left hip instead of by the ground, which also produces an anti-clockwise moment

3. The left hip abductors (primarily gluteus medius) contract, produces a clockwise moment to keep the pelvis from dropping on the unsupported side. The reaction force to this contraction passes through the left hip.

Fig. 3.1 • Schematic of double legged stance: the force in each hip joint (226 N) is half the weight of the trunk (452 N). The abductors are not contracting.

Fig. 3.2 • Schematic of single legged stance on the left (the right leg is held up). The force in the left hip (1510 N) is the sum of: (i) weight of trunk (452 N), (ii) weight of right leg (147 N) and (iii) contraction force of abductor muscles (911 N).

These three components contribute to the increased force in the left hip as follows:

• The force from the trunk increases from 226 N to 452 N (23 kgf or 51 lbf) as this is now not shared

• Weight of right leg: 147 N (15 kgf or 33 lbf)

It should be noted that this example was invented for the purposes of illustration – the actual numbers should not be taken too seriously!

The four conditions which must be met if this mechanism is to operate satisfactorily are:

• The absence of significant pain on loading

• Adequate power in the hip abductors

Should one or more of these conditions not be met, the subject may adopt lateral trunk bending in an attempt to compensate.

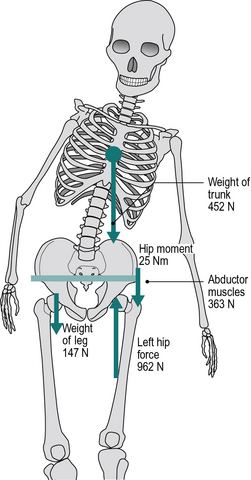

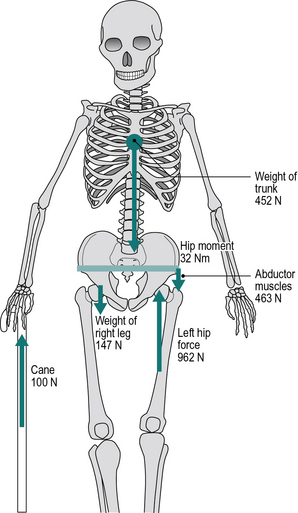

The effect of lateral trunk bending on the joint force is shown in Figure 3.3. There is no effect on components (1) and (2) of the increased force, but if the centre of gravity of the trunk is moved directly above the left hip, this eliminates the anti-clockwise moment produced by the mass of the trunk. The abductors are now only required to contract with a force of 363 N (37 kgf or 81 lbf) to balance the anti-clockwise moment provided by the weight of the right leg. There is thus a reduction of 548 N (56 kgf or 123 lbf) in the abductor contraction force and a corresponding reduction in the total joint force, from 1501 N down to 962 N. The numbers in the illustrations refer to standing; during the stance phase of walking, higher forces are to be expected due to the vertical accelerations of the centre of gravity, which cause the force transmitted through the leg to fluctuate above and below body weight (see Fig. 2.19). However, these fluctuations tend to be less in pathological than in normal gait, since the vertical accelerations are less in someone walking with a shorter stride length. The numbers also suppose that the bending of the trunk brings its centre of gravity exactly above the hip joint. This is unlikely to happen in practice, of course, but the principles remain the same, whether the centre of gravity is not deviated as far as the hip joint or even if it passes lateral to it.

Fig. 3.3 • Lateral trunk bending: bringing the trunk across the supporting hip reduces the anti-clockwise moments about the left hip from 62 Nm to 25 Nm, permitting the pelvis to be stabilised by a smaller abductor force. The force in the left hip (962 N) is the sum of: (i) weight of trunk (452 N), (ii) weight of right leg (147 N), and (iii) contraction force of abductor muscles (363 N).

There are a number of conditions in which this gait abnormality is adopted.

1. Painful hip:

If the hip joint is painful, as in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, the amount of pain experienced usually depends to a very large extent on the force being transmitted through the joint. Since lateral trunk bending reduces the total joint force, ‘Trendelenburg gait’ is extremely common in people with arthritis of the hip. Although it produces a useful reduction in force and hence in pain, the forces still remain substantial (962 N in Fig. 3.3) and some form of definitive treatment is usually required.

2. Hip abductor weakness:

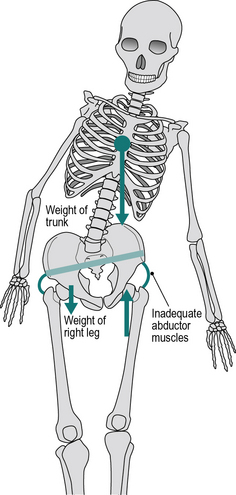

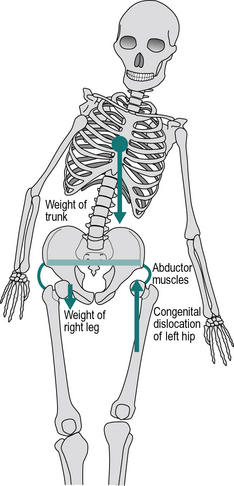

If the hip abductors are weak, they may be unable to contract with sufficient force to stabilise the pelvis during single leg stance. In this case, the pelvis will dip on the side of the foot which is off the ground (Trendelenburg's sign, as opposed to ‘Trendelenburg gait’). In order to reduce the demands on the weakened muscles, the subject will usually employ lateral trunk bending, in both standing and walking, to reduce joint moment as far as possible (Fig. 3.4). Hip abductor weakness may be caused by disease or injury affecting either the muscles themselves or the nervous system which controls them.

3. Abnormal hip joint:

Three conditions around the hip joint will lead to difficulties in stabilising the pelvis using the abductors: congenital dislocation of the hip (CDH, also known as developmental dysplasia of the hip), coxa vara and slipped femoral epiphysis. In all three, the effective length of the gluteus medius is reduced because the greater trochanter of the femur moves proximally, towards the pelvic brim. Since the muscle is shortened, it is unable to function efficiently and thus contracts with a reduced tension. In CDH and severe cases of slipped femoral epiphysis, a further problem exists in that the normal hip joint is effectively lost, to be replaced by a false hip joint, or pseudarthrosis. This abnormal joint is more laterally placed, giving a reduced lever arm for the abductor muscles, and it may fail to provide the ‘solid and stable fulcrum’ required. The combination of reduced lever arm and reduced muscle force gives these subjects a powerful incentive to walk with lateral trunk bending (Fig. 3.5). In many cases, particularly in older people with CDH, the false hip joint becomes arthritic and they add a painful hip to their other problems. Pain is frequently also a factor in slipped femoral epiphysis.

4. Wide walking base:

If the walking base is abnormally wide, there is a problem with balance during single leg stance. Rather than tip the whole body to maintain balance, as in Figure 2.28A, lateral bending of the trunk may be used to keep the centre of gravity of the body roughly over the supporting leg. In most cases, this will need to be done during the stance phase on both sides, leading to bilateral trunk bending and a waddling gait. A number of conditions, which will be described later, may cause a wide walking base.

5. Unequal leg length:

When walking with an unequal leg length, the pelvis tips downwards on the side of the shortened limb, as the body weight is transferred to it. This is sometimes described as ‘stepping into a hole’. The pelvic tilt is accompanied by a compensatory lateral bend of the trunk.

6. Other causes:

Perry (1992) gives a number of other causes for lateral bending of the trunk, including adductor contracture, scoliosis and an impaired body image, typically following a stroke.

Anterior trunk bending

In anterior trunk bending, the subject flexes his or her trunk forwards early in the stance phase. If only one leg is affected, the trunk is straightened again around the time of opposite initial contact, but if both sides are affected, the trunk may be kept flexed throughout the gait cycle. This gait abnormality is best seen from the side.

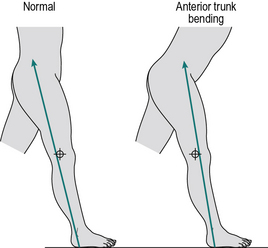

One important purpose of this gait pattern is to compensate for an inadequacy of the knee extensors. The left panel of Figure 3.6 shows that early in the stance phase, the line of action of the ground reaction force vector normally passes behind the axis of the knee joint and generates an external moment which attempts to flex it. This is opposed by contraction of the quadriceps, to generate an internal extension moment. If the quadriceps are weak or paralysed, they cannot generate this internal moment and the knee will tend to collapse. As shown in the right panel of Figure 3.6, anterior trunk bending is used to move the centre of gravity of the body forwards, which results in the line of force passing in front of the axis of the knee, producing an external extension (or hyperextension) moment. In addition to anterior trunk bending, subjects will sometimes keep one hand on the affected thigh while walking, to provide further stabilisation for the knee.

Fig. 3.6 • Anterior trunk bending: in normal walking, the line of force early in the stance phase passes behind the knee; anterior trunk bending brings the line of force in front of the knee, to compensate for weak knee extensors.

Other causes for anterior trunk bending are equinus deformity of the foot, hip extensor weakness and hip flexion contracture (Perry, 1992).

Posterior trunk bending

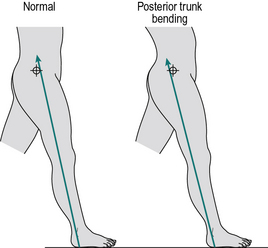

One form of posterior trunk bending is essentially a reversed version of anterior trunk bending, in that early in the stance phase, the whole trunk moves in the sagittal plane, but this time backwards instead of forwards. Again, it is most easily observed from the side. The purpose of this is to compensate for ineffective (weak) hip extensors. The line of the ground reaction force early in the stance phase normally passes in front of the hip joint (Fig. 3.7, left panel). This produces an external moment which attempts to flex the trunk forward on the thigh and is opposed by contraction of the hip extensors, particularly the gluteus maximus. Should these muscles be weak or paralysed, the subject may compensate by moving the trunk backwards at this time, bringing the line of action of the external force behind the axis of the hip joint, as shown in the right panel diagram of Figure 3.7.

Fig. 3.7 • Posterior trunk bending: in normal walking, the line of force early in the stance phase passes in front of the hip; posterior trunk bending brings the line of force behind the hip, to compensate for weak hip extensors.

A different type of posterior trunk bending may occur early in the swing phase, where the subject may throw the trunk backwards in order to propel the swinging leg forwards. This is most often used to compensate for weakness of the hip flexors or spasticity of the hip extensors, either of which makes it difficult to accelerate the femur forwards at the beginning of swing. This manoeuvre may also be used if the knee is unable to flex, since the whole leg must be accelerated forwards as one unit, which greatly increases the demands on the hip flexors. Posterior trunk bending may also occur when the hip is ankylosed (fused), the trunk moving backwards as the thigh moves forwards.

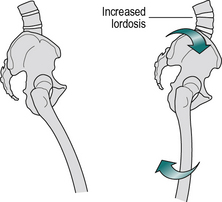

Increased lumbar lordosis

Many people have an exaggerated lumbar lordosis, but it is only regarded as a gait abnormality if the lordosis is used to aid walking in some way, which generally means that the degree of lordosis varies during the course of the gait cycle. Increased lumbar lordosis is observed from the side of the subject and generally reaches a peak at the end of the stance phase on the affected side.

The most common cause of increased lumbar lordosis is a flexion contracture of the hip. It is also seen if the hip joint is immobile due to ankylosis. Both of these deformities cause the stride length to be very short, by preventing the femur from moving backwards from its flexed position. This difficulty can be overcome if the femur can be brought into the vertical (or even extended) position, not through movement at the hip joint but by extension of the lumbar spine, with a consequent increase in the lumbar lordosis (Fig. 3.8).

Fig. 3.8 • Increased lumbar lordosis: when there is a fixed flexion deformity of the hip (left panel), the whole pelvis must rotate forwards for the femur to move into a vertical position (right panel), with a resulting increase in lumbar lordosis.

The orientation of the pelvis in the sagittal plane is maintained by the opposing pulls of the trunk muscles above and the limb muscles below. If there is muscle imbalance, for example a weakness of the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall, weakness of the hip extensors or spasticity of the hip flexors, the subject may develop an excessive anterior pelvic tilt, again with an increase in the lumbar lordosis.

Functional leg length discrepancy

Four gait abnormalities (circumduction, hip hiking, steppage and vaulting) are closely related, in that they are designed to overcome the same problem – a functional discrepancy in leg length. A review on the topic of leg length discrepancy was published by Gurney (2002).

An ‘anatomical’ leg length discrepancy occurs when the legs are actually different lengths, as measured with a tape measure or, more accurately, by long-leg X-rays. A ‘functional’ leg length discrepancy means that the legs are not necessarily different lengths (although they may be) but that one or both are unable to adjust to the appropriate length for a particular phase of the gait cycle. In order for natural walking to occur, the stance phase leg needs to be longer than the swing phase leg. If it is not, the swinging leg collides with the ground and is unable to pass the stance leg. The way that a leg is functionally lengthened (for the stance phase) is to extend at the hip and knee and to plantarflex at the ankle. Conversely, the way in which a leg is functionally shortened (for the swing phase) is to flex at the hip and knee and to dorsiflex at the ankle. Failure to achieve all the necessary flexions and extensions is likely to lead to a functional leg discrepancy and hence to one of these gait abnormalities. This usually occurs as the result of a neurological problem. Spasticity of any of the extensors or weakness of any of the flexors tends to make a leg too long in the swing phase, as does the mechanical locking of a joint in extension. Conversely, spasticity of the flexors, weakness of the extensors or a flexion contracture in a joint makes the limb too short for the stance phase. Other causes of functional leg length discrepancy include musculoskeletal problems such as sacroiliac joint dysfunction.

An increase in functional leg length is particularly common following a ‘stroke’, where a foot drop (due to anterior tibial weakness or paralysis) may be accompanied by an increase in tone in the hip and knee extensor muscles.

The gait modifications designed to overcome the problem may either lengthen the stance phase leg or shorten the swing phase leg, thus allowing a normal swing to occur. They are not mutually exclusive and a subject may use them in combination. The gait modification employed by a particular person may have been forced on them by the underlying pathology or it may have been a matter of chance. Two people with apparently identical clinical conditions may have found different solutions to the problem.

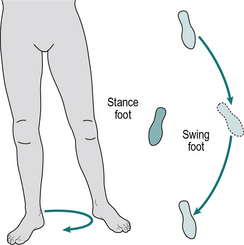

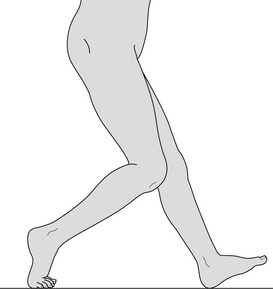

Circumduction

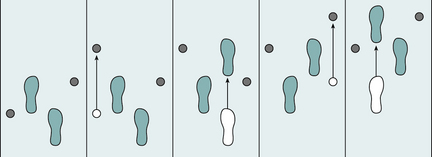

Ground contact by the swinging leg can be avoided if it is swung outward, in a movement known as circumduction (Fig. 3.9). The swing phase of the other leg will usually be normal. The movement of circumduction is best seen from in front or behind. Circumduction may also be used to advance the swinging leg in the presence of weak hip flexors, by improving the ability of the adductor muscles to act as hip flexors while the hip joint is extended.

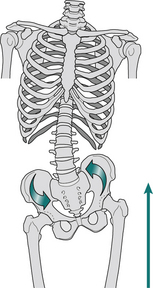

Hip hiking

Hip hiking is a gait modification in which the pelvis is lifted on the side of the swinging leg (Fig. 3.10), by contraction of the spinal muscles and the lateral abdominal wall. The movement is best seen from behind or in front.

By tipping the pelvis up on the side of the swinging leg, hip hiking involves a reversal of the second determinant of gait (pelvic obliquity about an anteroposterior axis). It may also involve an exaggeration of the first determinant (pelvic rotation about a vertical axis), to assist with leg advancement. Leg advancement may also be helped by posterior trunk bending at the beginning of the swing phase.

According to the New York University manual (1986), hip hiking is commonly used in slow walking with weak hamstrings, since the knee tends to extend prematurely and thus to make the leg too long towards the end of the swing phase. It is seldom employed for limb lengthening due to plantarflexion of the ankle.

Steppage

Steppage is a very simple swing phase modification, consisting of exaggerated knee and hip flexion, to lift the foot higher than usual for increased ground clearance (Fig. 3.11). It is best observed from the side. It is particularly used to compensate for a plantarflexed ankle, commonly known as foot drop, due to inadequate dorsiflexion control, which will be described later.

Vaulting

The ground clearance for the swinging leg will be increased if the subject goes up on the toes of the stance phase leg, a movement known as vaulting (Fig. 3.12). This causes an exaggerated vertical movement of the trunk, which is both ungainly in appearance and wasteful of energy. It may be observed from either the side or the front.

Fig. 3.12 • Vaulting: the subject goes up on the toes of the stance phase leg to increase ground clearance for the swing phase leg.

Vaulting is a stance phase modification, whereas the related gait abnormalities (circumduction, hip hiking and steppage) are swing phase modifications. For this reason, vaulting may be a more appropriate solution for problems involving the swing phase leg. Like hip hiking, it is commonly used in slow walking with hamstring weakness, when the knee tends to extend too early in the swing phase. It may also be used on the ‘normal’ side of an above-knee amputee whose prosthetic knee fails to flex adequately in the swing phase.

Abnormal hip rotation

As the hip is able to make large rotations in the transverse plane, for which the knee and ankle cannot compensate, an abnormal rotation at the hip involves the whole leg, with the foot showing an abnormal ‘toe in’ or ‘toe out’ alignment. The gait pattern may involve both stance and swing phases and is best observed from behind or in front.

Abnormal hip rotation may result from one of three causes:

1. A problem with the muscles producing hip rotation

2. A fault in the way the foot makes contact with the ground

3. As a compensatory movement to overcome some other problem.

Problems with the muscles producing hip rotation usually involve spasticity or weakness of the muscles which rotate the femur about the hip joint. For example, overactivity of the hip extensors in cerebral palsy may include an element of internal rotation. Imbalance between the medial and lateral hamstrings is a common cause of rotation; weakness of biceps femoris or spasticity of the medial hamstrings will cause internal rotation of the leg. Conversely, spasticity of biceps femoris or weakness of the medial hamstrings will result in an external rotation.

A number of foot disorders will produce an abnormal rotation at the hip. Inversion of the foot, whether due to a fixed inversion (pes varus) or to weakness of the peroneal muscles, will internally rotate the whole limb when weight is taken on it. A corresponding eversion of the foot, whether fixed (pes valgus) or due to weakness of the anterior and posterior tibial muscles, will result in an external rotation of the leg.

External rotation may be used as a compensation for quadriceps weakness, to alter the direction of the line of force through the knee. This could be used as an alternative to, or in addition to, anterior trunk bending. External rotation may also be used to facilitate hip flexion, using the adductors as flexors, if the true hip flexors are weak. Subjects with weakness of the triceps surae may also externally rotate the leg, to permit the use of the peroneal muscles as plantar flexors. Femoral anteversion or retroversion could cause excessive hip internal or external rotation, respectively.

Excessive knee extension

In the gait abnormality of excessive knee extension, the normal stance phase flexion of the knee is lost, to be replaced by full extension or even hyperextension, in which the knee is angulated backwards. This is best seen from the side.

One cause of knee hyperextension has already been described: quadriceps weakness can be compensated for by keeping the leg fully extended, using anterior trunk bending (Fig. 3.6), external rotation of the leg, or both, to keep the line of the ground reaction force from passing behind the axis of the knee joint. Other means of keeping the knee fully extended are pushing the thigh back by keeping one hand on it while walking and using the hip extensors to snap the thigh sharply back at the time of initial contact.

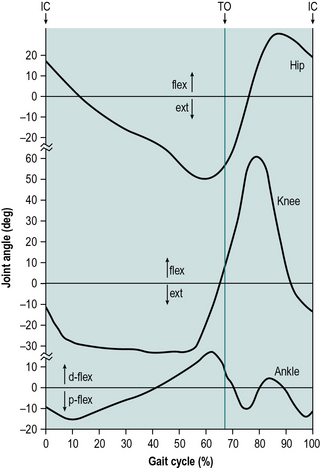

Hyperextension of the knee, accompanied by anterior trunk bending, is seen quite frequently in people with paralysis of the quadriceps following poliomyelitis. The gait abnormality is clearly of great value to the subject, since without it he or she would be unable to walk. However, the external hyperextension moment is resisted by tension in the posterior joint capsule, which gradually stretches, allowing the knee to develop a hyperextension deformity (‘genu recurvatum’). As a result of this deformity, the joint frequently develops osteoarthritis in later life. This is illustrated in Figure 3.13, which shows the left sagittal plane hip, knee and ankle angles during walking in a 41-year-old woman, whose quadriceps were paralysed on both sides by poliomyelitis at the age of 12. She walked very slowly, using two forearm crutches (cycle time 1.9 s; cadence 63 steps/min; stride length 1.00 m; speed 0.52 m/s). The knee hyperextended to 32° during weightbearing, but flexed normally to 63° during the swing phase. The hip extended more than in normal individuals, since hyperextension of the knee places the knee joint more posteriorly than usual, thus altering the angle of the femur.

Fig. 3.13 • Excessive knee extension: sagittal plane hip, knee and ankle angles in a subject with paralysed quadriceps, showing gross hyperextension of the knee and increased extension of the hip. Abbreviations as in Figure 2.5.

In normal walking, an external moment attempts to hyperextend the knee during terminal stance. This is resisted by an internal flexor moment (see Fig. 2.6), generated primarily by gastrocnemius. Should gastrocnemius be weak, the knee may be pushed backwards into hyperextension. This may help with walking, since the leg lengthening required during pre-swing can be provided by extending the knee, rather than by plantarflexing the ankle. However, there is a risk that the knee will go beyond full extension into hyperextension, with consequent damage to the posterior capsule.

Hyperextension of the knee is common in spasticity. One common cause is overactivity of the quadriceps, which extends the knee directly. Another is spasticity of the triceps surae, which plantarflexes the ankle and causes the body weight to be taken through the forefoot. The resulting forward movement of the ground reaction force vector generates an external moment, which is an exaggeration of the normal plantarflexion, and knee extension moments, which results in hyperextension of the knee.

Shortness of one leg may cause a person when standing to take all their weight on the other (longer) leg, with the knee hyperextended. This is because it is uncomfortable to stand on both legs, since the knee on the longer side would have to be kept flexed.

Excessive knee flexion

The knee is normally fully extended (or nearly so) twice during the gait cycle: around initial contact and around heel rise. In the gait abnormality known as excessive knee flexion, one or both of these movements into extension fails to occur. The flexion and extension of the knee are best seen from the side of the subject.

A flexion contracture of the knee will obviously prevent it from extending normally. A flexion contracture of the hip may also prevent the knee from extending, if hip flexion prevents the femur from becoming vertical or extended during the latter part of the stance phase (Fig. 3.14). By reducing the effective length of the leg during the stance phase, one of the compensations for a functional discrepancy in leg length will probably also be required.

Fig. 3.14 • Excessive knee flexion: in late stance phase there is increased knee flexion, caused by a flexion contracture of the hip.

Spasticity of the knee flexors may also cause the gait pattern of excessive knee flexion. Since the knee flexors are able to overpower the quadriceps, this may lead to other gait modifications, such as anterior trunk bending, to compensate for a relative weakness of the quadriceps. The knee may flex excessively following initial contact if the normal plantarflexion of the foot during loading response is prevented, through immobility of the ankle joint or a calcaneus deformity of the foot, preventing the force vector from migrating forwards along the foot. Increased flexion of the knee may also be part of a compensatory movement, either to reduce the effective limb length in functional leg length discrepancy or as part of a pattern of exaggerated hip, knee and arm movements, to make up for a lack of plantarflexor power in push off.

Inadequate dorsiflexion control

The dorsiflexors are active at two different times during the gait cycle, so inadequate dorsiflexion control may give rise to two different gait abnormalities. During loading response, the dorsiflexors resist the external plantarflexion moment, thus permitting the foot to be lowered to the ground gently. If they are weak, the foot is lowered abruptly in a foot slap. The dorsiflexors are also active during the swing phase, when they are used to raise the foot and achieve ground clearance. Failure to raise the foot sufficiently during initial swing may cause toe drag. Both problems are best observed from the side of the subject and both make a distinctive noise. A subject with inadequate dorsiflexion control can often be diagnosed by ear, before they have come into view!

Inadequate dorsiflexion control may result from weakness or paralysis of the anterior tibial muscles or from these muscles being overpowered by spasticity of the triceps surae. An inability to dorsiflex the foot during the swing phase causes a functional leg length discrepancy, for which a number of compensations were described previously. Toe drag will only be observed if the subject fails to compensate. Toe drag may also occur if there is delayed flexion of the hip or knee in initial swing, causing the foot to catch on the ground, despite adequate dorsiflexion at the ankle.

Even if they suffer from inadequate dorsiflexion control, subjects with spasticity are frequently able to achieve dorsiflexion in the swing phase, because flexion of the hip and knee are often accompanied by reflex dorsiflexion of the ankle, in a primitive movement pattern related to the flexor withdrawal reflex, mentioned in Chapter 1.

Abnormal foot contact

The foot may be abnormally loaded so that the weight is primarily borne on only one of its four quadrants. Loading on the heel or forefoot is best observed from the side and loading on the medial or lateral side is best observed from the front, although some authorities state that the foot should always be observed from behind. Where a glass walkway is available, viewing the foot from below gives an excellent idea of the pattern of foot loading.

Loading of the heel occurs in the deformity known as talipes calcaneus (also known as pes calcaneus), where the forefoot is pulled up into extreme dorsiflexion (Fig. 3.15), usually as a result of muscle imbalance, such as results from spasticity of the anterior tibial muscles or weakness of the triceps surae. Except in mild cases, weight is never taken by the forefoot and the stance phase duration is reduced by the loss of the ‘terminal rocker’ (p. 000). The reduced stance phase duration on the affected side reduces the swing phase duration on the opposite side, which in turn reduces the opposite step length and the overall stride length. The ground reaction force vector remains posterior, producing an increased external flexion moment at the knee.

In the deformity known as talipes equinus (or pes equinus) (Fig. 3.16), the forefoot is fixed in plantarflexion, usually through spasticity of the plantarflexors. In a mild equinus deformity, the foot may be placed onto the ground flat; in more severe cases the heel never contacts the ground at all and initial contact is made by the metatarsal heads, in a gait pattern known as primary toestrike. Because the line of force from the ground reaction is displaced anteriorly, an increased external moment tending to extend the knee is present (plantarflexion/knee extension couple). The loss of the initial rocker (p. 00) shortens the stride length.

Excessive medial contact occurs in a number of foot deformities. Weakness of the inverters or spasticity of the everters will cause the medial side of the foot to drop and to take most of the weight. In pes valgus, the medial arch is lowered, permitting weightbearing on the medial border of the foot. Increased medial foot contact may also be due to a valgus deformity of the knee, accompanied by an increased walking base.

Excessive lateral foot contact may also result from foot deformity, when the medial border of the foot is elevated or the lateral border depressed, by spasticity or weakness. The foot deformity known as talipes equinovarus (Fig. 3.17) combines equinus with varus, producing a curved foot where all the load is borne by the outer border of the forefoot. Although the term club foot may be applied to any foot deformity, it is most commonly applied to talipes equinovarus.

Another form of abnormal foot contact is the stamping that commonly accompanies a loss of sensation in the foot, such as occurs in tabes dorsalis, the final stage of syphilis. The subject receives feedback on ground contact from the vibration caused by the impact of the foot on the ground.

Abnormal foot rotation

Normal individuals place the foot on the ground approximately in line with the direction of walk, typically with a few degrees of toe out. Pathological toe in or toe out angles may be produced by internal or external hip rotation, torsion (twisting) of the femur or tibia, or deformity of the foot itself. An important consequence of an abnormal foot rotation is that it causes the ground reaction force to be in an abnormal position relative to the rest of the leg. For example, if the foot is internally rotated, the ground reaction force is more medial than normal, which will generate external adductor moments at the ankle and knee. In either internal or external foot rotation, the effective length of the foot is reduced in the direction of progression, so that the ground reaction force during terminal stance and pre-swing is likely to be more posterior than normal. This reduces the lever arm for the triceps surae to generate an internal plantarflexion moment.

This is one example of a problem known as lever arm disease or lever arm deficiency, in which individuals with normal muscle strength are unable to generate sufficient internal joint moments, due to a reduction in the length of a muscle's lever arm. This is particularly seen in individuals with cerebral palsy who have a severe degree of internal or external foot rotation; the resulting posterior placement of the ground reaction force increases the external moment flexing the knee.

Insufficient push off

In normal walking, weight is borne on the forefoot during the ‘push off’ in pre-swing. In the gait pattern known as insufficient push off, the weight is taken primarily on the heel and there is no push off phase, the whole foot being lifted off the ground at once. It is best observed from the side.

The main cause of insufficient push off is a problem with the triceps surae or Achilles tendon, which prevents adequate weightbearing on the forefoot. Rupture of the Achilles tendon and weakness of the soleus and gastrocnemius are typical causes. Weakness or paralysis of the intrinsic muscles of the foot may also prevent the foot from taking load through the forefoot. Insufficient push off may also result from any foot deformity, if the anatomy is so distorted that it prevents normal forefoot loading. A calcaneus deformity (Fig. 3.15) obviously makes it impossible to put any significant load on the forefoot.

Another important cause of insufficient push off is pain under the forefoot, if the amount of pain is affected by the degree of loading (as it usually is). This may occur in metatarsalgia and also when arthritis affects the metatarsophalangeal joints. The loss of the terminal rocker causes the foot to leave the ground prematurely, before the hip has fully extended. This reduces the stance phase duration on the affected side and hence the swing phase duration and step length on the opposite side, and produces an asymmetry in gait timing.

Abnormal walking base

The walking base is usually in the range 50–130 mm. In pathological gait it may be either increased or decreased beyond this range. While ideally determined by actual measurement, changes in the walking base may be estimated by eye, preferably from behind the subject.

An increased walking base may be caused by any deformity, such as an abducted hip or valgus knee, which causes the feet to be placed on the ground wider apart than usual. A consequence of an increased walking base is that increased lateral movement of the trunk is required to maintain balance, as shown in Figure 2.28.

The other important cause of an increased walking base is instability and a fear of falling, the feet being placed wide apart to increase the area of support. This allows a margin of error in the positioning of the centre of gravity over the feet. This gait abnormality is likely to be present when there is a deficiency in the sensation or proprioception of the legs, so that the subject is not quite sure where the feet are, relative to the trunk. It is also used in cerebellar ataxia, to increase the level of security in an uncoordinated gait pattern. Another effective way to improve stability is to walk with one or two canes.

A narrow walking base usually results from an adduction deformity at the hip or a varus deformity at the knee. Hip adduction may cause the swing phase leg to cross the midline, in a gait pattern known as scissoring, which is commonly seen in cerebral palsy. In milder cases, the swing phase leg is able to pass the stance phase leg, but then moves across in front of it. In more severe cases, the swinging leg is unable to pass the stance leg: it stops behind it, with the side-to-side positions of the two feet reversed. This is clearly a very disabling gait pattern, with a very short stride length and negative values for the walking base and for the step length on one side.

Rhythmic disturbances

Gait disorders may include abnormalities in the timing of the gait cycle. Two types of rhythmic disturbance can be identified: an asymmetrical rhythmic disturbance shows a difference in the gait timing between the two legs; an irregular rhythmic disturbance shows differences between one stride and the next. Rhythmic disturbances are best observed from the side and may also be audible.

An antalgic gait pattern is specifically a gait modification that reduces the amount of pain a person is experiencing. The term is usually applied to a rhythmic disturbance, in which as short a time as possible is spent on the painful limb and a correspondingly longer time is spent on the pain-free side. The pattern is asymmetrical between the two legs but is generally regular from one cycle to the next. A marked difference in leg length between the two sides may also produce a regular gait asymmetry of this type, as may a number of other differences between the two sides, such as joint contractures or ankylosis.

Irregular gait rhythmic disturbances, where the timing alters from one step to the next, are seen in a number of neurological conditions. In particular, cerebellar ataxia leads to loss of the ‘pattern generator’, responsible for a regular, coordinated sequence of footsteps. Loss of sensation or proprioception may also cause an irregular arrhythmia, due to a general uncertainty about limb position and orientation.

Other gait abnormalities

A number of other gait abnormalities may be observed, either alone or in combination with some of the gait patterns described above. They include:

1. Abnormal movements, for example intention tremors and athetoid movements

2. Abnormal attitude or movements of the upper limb, including a failure to swing the arms

3. Abnormal attitude or movements of the head and neck

4. Sideways rotation of the foot following heelstrike

5. Excessive external rotation of the foot during swing, sometimes called a ‘whip’

This account has concentrated on gait abnormalities which may be observed visually. However, a number of gait abnormalities can only be detected using kinetic/kinematic gait analysis systems. An example is the presence of an abnormal moment, such as the excessive internal varus moment which may be present in the knee of children with myelomeningocoele and which may predispose them to the development of osteoarthritis (Lim et al., 1998).

Walking aids

The use of walking aids may modify the gait pattern considerably. While some people choose to use a walking aid to make it easier to walk, for example to reduce the pain in a painful joint, others are totally unable to walk without some form of aid. Although there are many detailed variations in design, walking aids, also called ‘assistive devices’, can be classified into three basic types – canes, crutches and frames. All three operate by supporting part of the body weight through the arm rather than the leg. While this is an effective way of coping with inadequacies of the legs, it frequently leads to problems with the wrist and shoulder joints, which are simply not designed for the transmission of large forces.

There is considerable variability in the way in which walking aids are used and people will often use them in ways which do not quite fit the typical patterns described in the following sections.

Canes

The simplest form of walking aid is the cane, also known as a walking stick, by means of which force can be transmitted to the ground through the wrist and hand. Since the forearm muscles are relatively weak and the joints of the wrist fairly small, it is impossible to transmit large forces through a cane for any length of time. The torque which can be applied to the upper end of the cane is limited by the grip strength and by the shape of the handle, since the hand tends to slip. For this reason the major direction of force transmission is along the axis of the cane. Canes may be used for three purposes, which are often combined:

Improve stability

Canes are frequently used by elderly and infirm people to improve their stability. This is achieved by increasing the size of the area of support, thus removing the need to position the centre of gravity over the relatively small supporting area provided by the feet. In those with only minor stability problems, a single cane may be used. This will not provide a secure supporting area during single limb support, but does make it easier to correct for small imbalances. Since the cane is usually placed on the ground some distance away from the feet, giving a relatively long lever arm, a modest force through the cane will produce a substantial moment to correct for any positioning error. For maximum security, a person will need to use two canes, so that a triangular supporting area is always available. This is provided by two canes and one foot during single limb support and by one cane and two feet during double support. If only a single cane is used, it will usually be advanced during the stance phase of the more secure leg. If two canes are used, they are usually advanced separately, during double limb support, to provide the maximum stability at all times.

Generate a moment

The use of a cane to generate a moment is illustrated in Figure 3.18. A vertical force of 100 N (10 kgf or 22 lbf) is applied through the cane, which generates a clockwise moment, applied to the shoulder girdle and hence to the pelvis. This reduces the size of the moment which the hip abductor muscles need to generate to keep the pelvis level. The contraction of these muscles is reduced from 911 N (93 kgf or 204 lbf) to 463 N (47 kgf or 104 lbf), a reduction of 448 N (56 kgf or 123 lbf). The total force in the hip joint is reduced by the sum of this amount and the force applied by the cane to the ground. For this mechanism to work, the cane must be held in the opposite hand to the painful hip. A cane may also be used to generate a lateral moment at the knee, to reduce the loading on one side of the joint. The cane is advanced during the swing phase of the leg it is protecting.

Fig. 3.18 • The use of a cane to generate a clockwise moment reduces the contraction force of the hip abductors and hence the force in the hip joint. The force in the left hip (962 N) is the sum of: (i) weight of trunk (452 N), (ii) weight of right leg (147 N), (iii) contraction force of abductor muscles (463 N), less: (iv) force through cane (100 N). (Compare with Figure 3.2 (force in left hip of 1510 N during single leg stance).)

Reduce limb loading

When using a cane to remove some of the load from the leg, it is usually held in the same hand as the affected leg and placed on the ground close to the foot. In this way, load sharing can be achieved between the leg and the cane, even to the extent of removing the load entirely from the leg. The cane follows the movements of the affected leg, being advanced during the swing phase on that side. The person will normally lean sideways over the cane, in a lateral lurch, to increase the vertical loading on it and hence to reduce the load in the leg. A cane may be used in this way to relieve pain in the hip, knee, ankle or foot. If the cane is held in the opposite hand, as is often recommended, the lateral lurching can be avoided but the degree of off-loading is reduced.

Whichever of these three reasons a person has for using a cane, the degree of disability will determine whether one or two canes are used. It may be observed that a subject uses a cane in the opposite hand from what might have been expected. In some cases he or she has simply not discovered that they would benefit more from using the cane in the other hand but more often, the observer has failed to appreciate fully all the compensations which the subject has adopted.

There are a number of ways in which the simple cane can be modified, including many different types of handgrip. A particularly important variant on the simple cane is the broad based cane, also known as a Hemi or crab cane, which may have three feet (tripod) or four feet (tetrapod or quad cane). This differs from the simple cane in that it will stand up by itself and will tolerate small horizontal force components, so long as the overall force vector remains within the area of its base. It is particularly helpful when standing up from the sitting position. The increased stability is gained at the expense of an increase in weight and particularly bulk, which may cause difficulties when going through doorways.

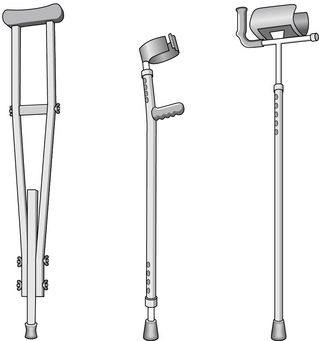

Crutches

The main difference in function between a crutch and a cane is that a crutch is able to transmit significant forces in the horizontal plane. This is because, unlike the cane, which is effectively fixed to the body at only a single point, the crutch has two points of attachment, one at the hand and one higher up the arm, which provide a lever arm for the transmission of torque. Although there are many different designs of crutch, they fall into two categories: axillary crutches and forearm crutches. As with the cane, it is also possible to have a broad-based crutch, ending in three or four feet.

Axillary crutches (Fig. 3.19, left panel), as their name suggests, fit under the axilla (armpit). They are usually of simple design, with a padded top surface and a hand-hold in the appropriate position. The lever arm between the axilla and the hand is fairly long and enough horizontal force can be generated to permit walking when both legs are straight and non-functional. A disadvantage of this type of crutch is that the axilla is not an ideal area for weightbearing and incorrect fitting or prolonged use may damage the blood vessels or nerves. Although some people use axillary crutches for many years, they are more suitable for short-term use, for instance while a patient has a broken leg set in plaster.

There are many different types of forearm crutches, also called elbow, Lofstrand or Canadian crutches (Fig. 3.19, middle panel). They differ from axillary crutches in that the upper point of contact between the body and the crutch is provided by either the forearm or the upper arm, rather than by the axilla. The lever arm is thus shorter than for an axillary crutch, although this is seldom a problem, and they usually run less risk of tissue damage, as well as being lighter and more acceptable cosmetically. In the normal forearm crutch, most of the vertical force is transmitted through the hand, but the use of a ‘gutter’ or ‘platform’ permits more load to be taken by the forearm itself (Fig. 3.19, right panel).

Walking frames

The most stable walking aid is the frame, also called a ‘walker’ or ‘Zimmer frame’, which enables the subject to stand and walk within the area of support provided by its base. Considerable force can be applied to the frame vertically and moderate forces can be applied horizontally, provided that the overall force vector remains within the area of support. The usual method of walking is first to move the frame forwards, then to take a short step with each foot, then to move the frame again and so on. Walking is thus extremely slow, with a start-stop pattern. Although the subject is encouraged to lift the frame forward at each step, they are more often simply slid along the ground.

A rolling walker is a variant on the walking frame, in which the front feet are replaced by wheels. This makes it easier to advance, at the expense of a slight reduction in stability in the direction of progression. The mode of walking is very similar to that with the frame, except that it is easier to move forwards, since tipping the rolling walker lifts the back feet clear of the ground. Commonly patients misuse the rolling walker by sliding it forwards, rather than tipping it and tennis balls are now frequently placed on the rear legs to facilitate sliding it due to its frequent occurrence. A further variant on the design is a rollator, which is a walking frame that has four wheels on all four legs, and is equipped with hand-operated brakes. These devices also often have seats in the middle, which the operator can use if they need to quickly sit, but the operator must turn around and face the opposite direction before sitting in most models. There are many other designs of frames and walkers, including those which fold, those with ‘gutters’ to support the body weight through the forearms, and those in which the two sides are connected at the back, rather than at the front. The stop–start gait pattern seen with some walking aids (especially frames) is known as an ‘arrest gait’.

Gait patterns with walking aids

There are a number of different ways of walking when using a cane, crutch or walker. The terminology varies somewhat from one author to another; the descriptions which follow are based on the well-illustrated text by Pierson (1994). The first four gait patterns involve the greatest support from the upper limbs, by means of a walking frame, two crutches or two canes. The last two require less support, with a crutch or cane held in only one hand.

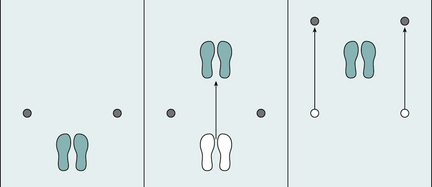

1. Four-point gait can be employed with canes or crutches. Also known as ‘reciprocal gait’, it involves the separate and alternate movement of each of the two legs and the two walking aids, for example: left crutch – right leg – right crutch – left leg (Fig. 3.20). This pattern is very stable and requires little energy but it is very slow, so that the oxygen cost (oxygen consumption per unit distance) may be higher than for the three-point gait described below.

2. Three-point gait is used when only one leg can take weight or the two legs move together as a single unit. It is only used with crutches or a walker. Two main forms of three-point gait are recognised: step-through and step-to. These terms are used when the lower limb musculature is able to provide the movement of the legs. If the legs are paralysed and their movement is provided by the upper limbs and trunk, the terms swing-through and swing-to are used (Pierson, 1994). In step-through gait, the foot or feet move from behind the line of the two crutches to in front of them (Fig. 3.21). This gait pattern requires a lot of energy and good control of balance but it can be fairly fast. In step-to gait, the foot or feet are advanced to just behind the line of the crutches, which are then moved further forwards and the process repeated (Fig. 3.22). Since the stride length is short, walking speed is slow but energy and stability requirements are not as high as for step-through gait.

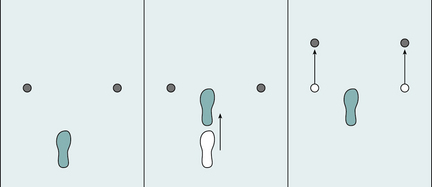

3. Modified three-point gait (also known as three-one gait) may be used when one leg is able to take full body weight but the other is not. It may be employed with a walker or with two crutches or canes. The walking aids and the affected leg move forward together, while weight is taken on the sound leg. That leg is then advanced, while weight is taken on the bad leg and the walking aids. This makes for a stable gait pattern, requiring little strength or energy, but the speed is fairly low.

4. Two-point gait resembles four-point gait, except that the crutch or cane on one side is moved forward at the same time as the leg on the other, for example: left crutch/right leg – right crutch/left leg. It is faster than four-point gait, yet is still fairly stable and requires little energy. However, it demands good coordination by the subject.

5. Modified four-point gait is performed when the walking aid is carried in the opposite hand to the affected leg. This gait pattern is typically used in hemiplegia, where there is paralysis of an arm and a leg on the same side. A typical walking sequence would be right crutch – left leg – right leg.

6. Modified two-point gait also involves the use of a walking aid on the opposite side to the bad leg, but the walking aid and the bad leg are moved forward together, for example: right crutch/left leg – right leg. It clearly needs better strength and coordination than modified four-point gait, but gives better speed.

Fig. 3.20 • Four-point gait. One crutch or leg is moved at a time in the pattern: left crutch – right leg – right crutch – left leg.

Treadmill gait

It is often more convenient to study gait while the subject walks on a treadmill rather than over the ground, since the volume in which measurements need to be made is much smaller and they can conveniently be connected to wires or breathing tubes. However, there are subtle differences between treadmill and overground gait, particularly with regard to joint angles. The reduced airflow over the body is unlikely to be a significant factor, but the subject's awareness of the limited length of the treadmill belt may cause them to shorten their stride. However, the most important differences are probably due to changes in the speed of the treadmill belt, as the subject's feet decelerate it at initial contact and accelerate it at push off, effectively storing energy in the treadmill motor. This effect is minimised by using a large treadmill with a powerful motor (Savelberg et al., 1998). Treadmills instrumented with force plates have been studied to examine potential differences between overground and treadmill walking and running. In general, these studies have found minimal differences in treadmill walking/running versus overground walking/running in both kinetic and kinematic parameters, provided the treadmill belt was sufficiently stiff and that subjects were acclimated to treadmill use (Riley et al., 2008).

Gurney B. Leg length discrepancy. Gait Posture. 2002;15:195–206.

Lim R., Dias L., Vankoski S., et al. Valgus knee stress in lumbosacral myelomeningocele: a gait-analysis evaluation. J. Pediatr. Orthop.. 1998;18:428–433.

New York University. Lower Limb Orthotics. New York, NY: New York University Postgraduate Medical School; 1986.

Perry J. Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated; 1992.

Pierson F.M. Principles and Techniques of Patient Care. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1994.

Riley P.O., Paolini G., Croce U.D., et al. A kinematics and kinetic comparison of overground and treadmill running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.. 2008;40(6):1093–1100.

Savelberg H.H.C.M., Vorstenbosch M.A.T.M., Kamman E.H., et al. Intra-stride belt-speed variation affects treadmill locomotion. Gait Posture. 1998;7:26–34.