13 Pulp Chambers and Canals

The terminology and essential features of the pulp chambers and pulp canals are considered before presenting the details of pulp chambers and canals using sectioned tooth specimens. Then a brief section on radiographic visualization of pulp chambers and canals is provided. After that a short section is presented on crown and root fractures. A final section considers the relationship of the teeth to the mandibular canal.

The use of the term pulp chamber, pulp cavity, or coronal pulp to designate that part of the crown normally filled with soft tissue varies with the anatomist; however, as with the terms root pulp and radicular pulp, and pulp canal and root canal, it is probably a matter of professional preference, because a good case can be made for each of the terms. These two sets of terms relating to crown and root are used as if they have the same meaning, with the recognition that arguably there may be contextualized differences.

Pulp, Chamber, and Canals

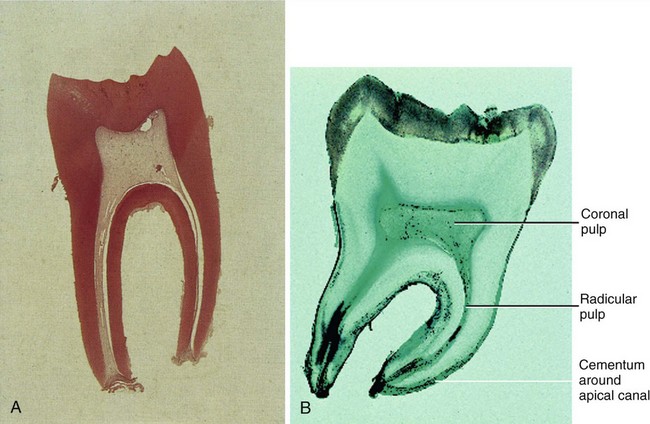

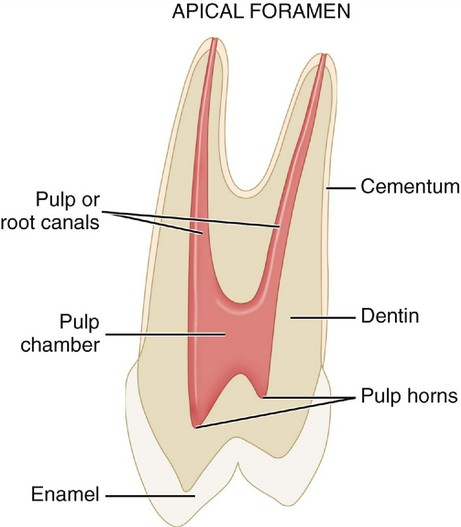

The crown and root portion of a tooth that contains the pulp tissues has been arbitrarily divided into the pulp chamber and the root or pulp canal (Figure 13-1). The complexities of these cavities cannot be fully appreciated without studying longitudinal and transverse sections of each of the representative types of teeth.

The dental pulp is the soft tissue component of the tooth. It occupies the internal cavities of the tooth (i.e., the pulp chamber and pulp canal). In general, the outline of the pulp tissue corresponds to the external outline form of the tooth (i.e., the outline form of the pulp chamber corresponds with the shape of the crown, whereas the outline form of the pulp canal corresponds with the shape of the roots of a tooth).

The dental pulp within these cavities originates from the mesenchyme and has been assigned a number of different functions: formative, nutritive, sensory, and defensive. The initial function of the dental pulp is the formation of dentin during the developmental period. The complex sensory system within the dental pulp controls the blood flow and is responsible for at least mediation of the sensation of pain. The formation of reparative dentin or secondary dentition (osteoid-like dentin) represents a defensive response to any form of irritation, whether it is mechanical, thermal, chemical, or bacterial. The reactive dentin is usually limited to the area of pulpal irritation. Separating reactive changes (response to injury) from purely aging-related changes may be difficult or impossible to do at this time.

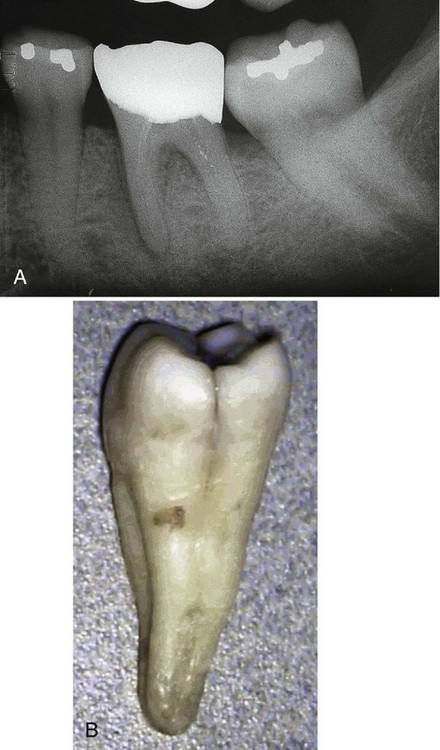

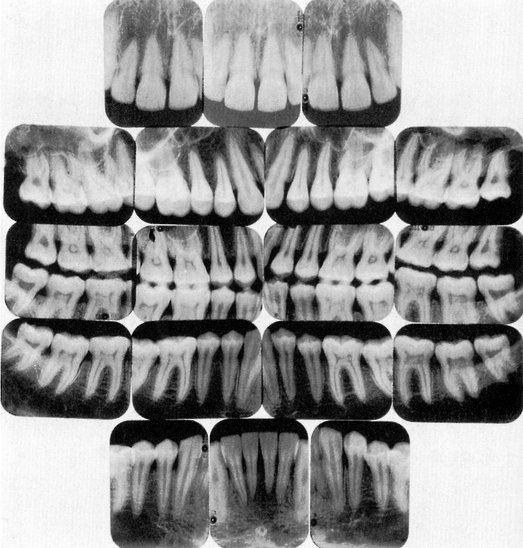

Radiographs

The use of radiographs or digital radiography for the diagnosis and treatment of pulpal disease requires that the morphological features of the pulp chambers and root canals, which are three-dimensional, be visualized when compressed into a “two-dimensional” radiographic image. Thus, radiographic views taken of the teeth from a facial orientation show a monoplane, buccolingual view of the hard tooth structures and radiolucent spaces for the pulp and canals (Figure 13-2). Mesiodistal aspects of longitudinal sections usually are seen only incidentally (e.g., on radiographs of malposed, rotated teeth). Thus, the radiographic anatomy of the pulp cavity from a mesial-distal aspect is not well known. Radiographic views of the pulp chambers and canals will be considered in more detail later.

SIZE OF THE PULP CAVITY

The size of the pulp chamber depends on the age of the tooth and its history of trauma. Secondary dentin is formed continuously throughout the life of the tooth as a normal process, as long as the vitality of the tooth is maintained. The formation of secondary dentin is not uniform, because the odontoblasts adjacent to the floor and roof of the pulp cavity produce greater quantities of secondary dentin than do the odontoblasts located adjacent to the walls of the pulp cavity.1 Therefore the size of the pulp cavity is much larger in a young individual than in an adult (Figure 13-3, A and B) and should be considered before extensive tooth reduction is accomplished, especially in a young person.

Figure 13-3 Comparison in size of the pulps of two intact lower first permanent molars at different ages. A, The young pulp chamber is large (magnification ×8). B, The older pulp is greatly reduced in size (magnification ×8).

(A From Berkovitz BKB, Holland GR, Moxham BJ: Oral anatomy, histology, and embryology, ed 3, St Louis, 2002, Mosby. B from Avery JK, Chiego DJ: Essentials of oral histology and embryology, ed 3, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

Various traumatic injuries occur that, if severe enough, will initiate a different type of dentin formation. Irritation-induced or reparative dentin may be formed in response to the carious process, abrasion, and attrition, as well as to operative procedures. This response is protective but may ultimately be detrimental in later years, because a finite amount of space is present within the pulp cavity. The size of the pulp cavity in a given tooth should be compared with that in the other teeth. If the calcification demonstrated is a localized phenomenon and is extensive, elective endodontic therapy is strongly suggested before any restorative procedure. Elective endodontics should be considered when extreme calcification is present in a tooth scheduled for complex restorative procedures.

Foramen

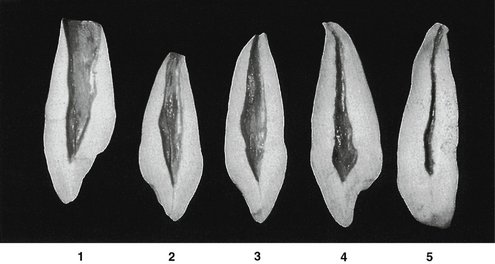

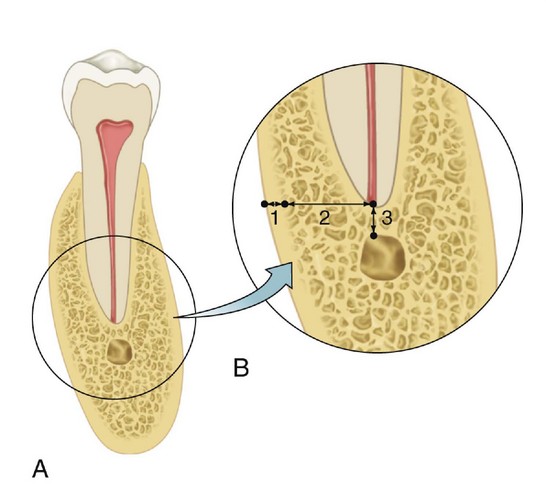

The neurovascular bundle, which supplies the internal contents of the pulp cavity, enters through the apical foramen or foramina (see Figure 13-1). As the root begins to develop, the apical foramen is actually larger than the pulp chamber (Figure 13-4, 1), but it becomes more constricted at the completion of root formation (Figure 13-4, 2 through 5).

Figure 13-4 Maxillary canine. Labiolingual sections show various stages of development. 1, Crown complete; root partially completed with large pulp cavity, wide open at apical end. 2, Tooth almost complete, except for lack of constriction of apical foramen. 3, Canine of young individual with large pulp cavity and completed root tip. 4, Typical canine of adult, demonstrating constriction of the foramen. 5, Canine of an elderly individual with a constricted pulp chamber and canal; this specimen has lost its original crown form because of wear during function.

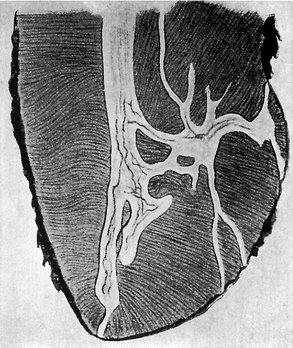

It is possible for any root of a tooth to have multiple apical foramina. If these openings are large enough, the space that leads to the main root canal is called a supplementary or lateral canal (Figure 13-5). If the root canal breaks up into multiple tiny canals, it is referred to as a delta system2 because of its complexity (Figure 13-6).

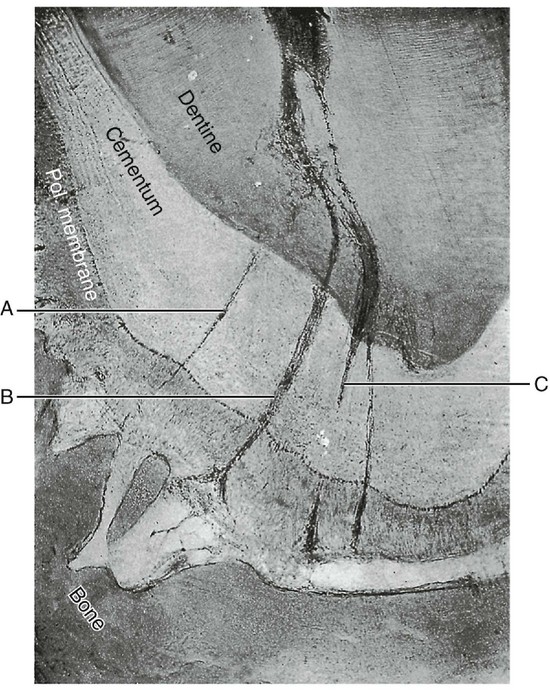

Demarcation of Pulp Cavity and Canal

The cementoenamel junction (CEJ) is not quite at the level at which the root canal becomes the pulp chamber (see Figure 13-1). This demarcation is mainly macroscopically based but may be visualized by exploring the CEJ (see Figure 2-16) and noting the difference in density between the enamel and dentin at the mesial and distal tooth surfaces on radiographs. Enamel covers the external surface of the dentin, which makes up part of the pulp chamber, whereas cementum covers the entire external dentinal surface of the root canal space. The demarcation is simpler in multirooted teeth, because the pulp cavity within the root is the root canal and the remaining pulp cavity is the pulp chamber. Microscopically, the pulp within the chamber appears to be more cellular than the pulp found within the pulp of the root canal. The odontoblasts are cuboidal in the coronal pulp chamber but gradually flatten out as the apex is approached. The transition from the pulp chamber to the root canal is not sharply demarcated microscopically, and this demarcation is not sharply delineated macroscopically.

Pulp Horns

Projections or prolongations in the roof of the pulp chamber correspond to the various major cusps or lobes of the crown. The pulpal tissues that occupy these prolongations are called pulp horns (Figure 13-7). The prominence of the cusps or lobes corresponds with the development of the pulp horns. If the cusps or labial lobes are prominent (as in young individuals), one should expect to find equally prominent pulp horns underlying these structures (see Figure 13-8, B, 6). These projections become less prominent with time as a result of the formation of secondary dentin (see Figure 13-8, B, 1).

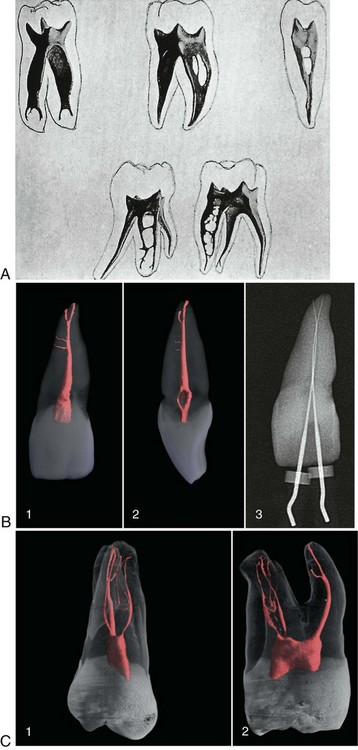

Figure 13-7 A, Molar and bicuspid pulp cavities. Note the prominence of the pulp horns and the complexities of the pulp chambers and root canal systems. B, Microcomputed tomographic scans of dental anatomy (36 µm resolution). 1, Clinical view of tooth #9 shows two accessory canals and an apical bifurcation. 2, Mesiodistal view of the tooth shown in 1. 3, Working length radiograph with files placed in both apical canal aspects. C, Microcomputed tomographic scans of more complicated dental anatomy (36 µm resolution). 1, Clinical view of tooth #3 shows a fine mesiobuccal and distobuccal canal system with additional anatomy in all three roots. 2, Mesiodistal view of the tooth shown in 1.

(A From Riethmuller RH: The filling of root canals with Prinz’ paraffin compound, Dent Cosmos 56:490, 1914. B and C from Cohen S, Hargreaves KM: Pathways of the pulp, ed 9, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

Clinical Applications

One of the primary functions of the dentist is to prevent, intercept, and treat diseases or disorders affecting the dentition. It is also essential that the clinician be aware of the location and size of the pulp cavities during operative procedures to prevent unnecessary encroachment on the pulp. It is also incumbent on the clinician to know the location of the mandibular canal and nerve.

Endodontic procedures also require a thorough knowledge of the pulp cavity. Perforation during access preparation, failure to locate all the canals, or perforation of the root surface may result in the ultimate loss of the tooth. Therefore the clinician performing endodontics must know the size and location of the pulp chamber and the expected number of roots and canals.

Radiographic detection of all accessory roots or canals may not be possible, although some evidence is present based on the shape of the crown that additional canals are present. Even so, the clinician must recognize some of the internal signs of additional canals during the endodontic procedure. With a thorough knowledge of the pulp cavities in the permanent dentition, prevention, interception, and treatment of dentition-related disease processes will be accomplished with a greater degree of success.

Pulp Cavities of the Maxillary Teeth

MAXILLARY CENTRAL INCISOR

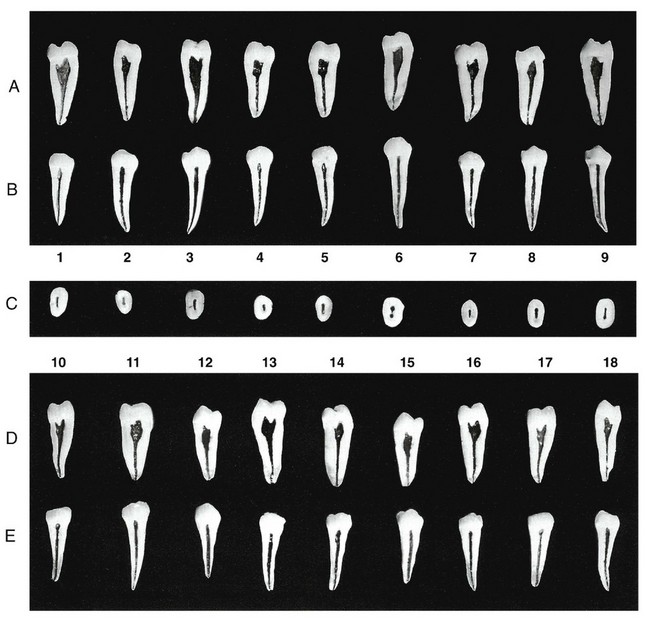

Labiolingual Section (Figure 13-8, A)

The pulp cavity follows the general outline of the crown and root. The pulp chamber is very narrow in the incisal region. If a great amount of secondary or irritation-induced dentin has been produced, this portion of the pulp chamber may be partially or completely obliterated (Figure 13-8, A, 3). In the cervical region of the tooth, the pulp chamber increases to its largest labiolingual dimension.

Below the cervical area, the root canal tapers, gradually ending in a constriction at the apex of the tooth (apical constriction). The apical foramen is usually located near the very tip of the root but may be located slightly to the labial (Figure 13-8, A, 3, 4, and 5) or lingual aspect of the root (Figure 13-8, A, 1 and 6). Because of this generalized phenomenon it has been suggested that the root canal filling should appear on radiographs to extend no closer than 1 mm from the radiographic apex of the tooth. However, with the use of an electronic apical locator the clinician can have more confidence in more closely reaching the apex without overfilling.

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-8, B)

The pulp chamber is wider in the mesiodistal dimension than in the labiolingual dimension. The pulp cavity conforms to the general shape of the outer surface of the tooth. If prominent mamelons (see Figure 1-10, B) are or have been present, it is not unusual to find definite prolongations or pulp horns in the incisal region of the tooth (Figure 13-8, B, 5 and 6). The pulp cavity then tapers rather evenly along its entire length until reaching the apical constriction. The position of the apical foramen is usually slightly off center from the tip of the root, but some foramina deviate drastically from the apex of the root (Figure 13-8, B, 6).

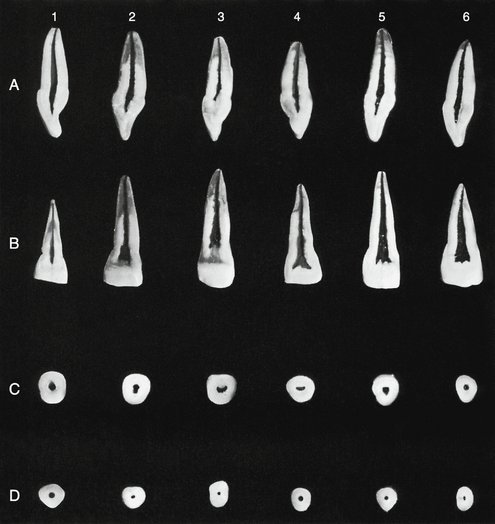

Cervical and Midroot Cross Sections (Figure 13-8, C and D)

The pulp cavity is widest at about the cervical level, and the pulp chamber is generally centered within the dentin of the root (Figure 13-8, C, 1 through 5). In young individuals the pulp chamber is roughly triangular in outline, with the base of the triangle at the labial aspect of the root (Figure 13-8, C, 5). As the amount of secondary or reactive dentin increases, the pulp chamber becomes more round or crescent-shaped (Figure 13-8, C, 3, 4, and 6). The outline form of the root at the cervical level is typically triangular with rounded corners (Figure 13-8, C, 5 and 6), but some are more rectangular or angular with rounded corners (Figure 13-8, C, 1 through 4). The root and pulp canal tend to be rounder at the midroot level (Figure 13-8, D, 1 through 6) than at the cervical level. The anatomy at the midroot level is essentially the same as that found at the cervical level, just smaller in all dimensions.

MAXILLARY LATERAL INCISOR

Labiolingual Section (Figure 13-9, A)

The anatomy of the lateral incisor is similar to that of the central incisor. The pulp cavity of the lateral incisor generally follows the outline form of the crown and the root. The pulp horns are usually prominent. The pulp chamber is narrow in the incisal region and may become very wide at the cervical level of the tooth (Figure 13-9, A, 1, 2, 3, and 5). Those teeth lacking this cervical enlargement of the pulp chamber possess a root canal that tapers slightly to the apical constriction (Figure 13-9, A, 4 and 6). Many of the apical foramina appear to be located at the tip of the root in the labiolingual aspect (Figure 13-9, A, 1, 4, and 6), whereas some exit on the labial (Figure 13-9, A, 2, and 3) or lingual aspect of the root tip (Figure 13-9, A, 5).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-9, B)

The pulp cavity closely follows the external outline of the tooth. The pulpal projections or pulp horns appear to be blunted when viewed from the labial aspect of the tooth. The pulp chamber and root canal gradually taper toward the apex, which often demonstrates a significant curve toward the distal in the apical region (Figure 13-9, B, 1 through 4, and 6).

Cervical and Midroot Cross Sections (Figure 13-9, C and D)

The cervical cross section shows the pulp chamber to be centered within the root. The root form of this tooth shows a large variation in shape (see the discussion of the lateral incisor in Chapter 6). The outline form of this tooth may be triangular, oval, or round (Figure 13-9, C, 1 through 6). The pulp chamber generally follows the outline form of the root, but secondary dentin may narrow the canal significantly (Figure 13-9, D, 4 and 6).

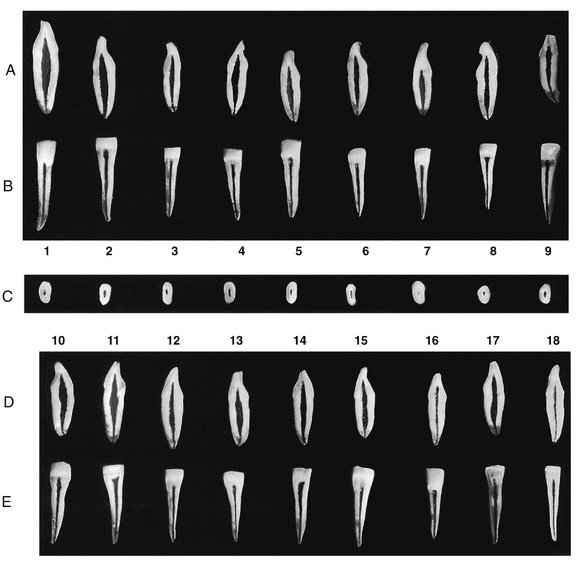

MAXILLARY CANINE

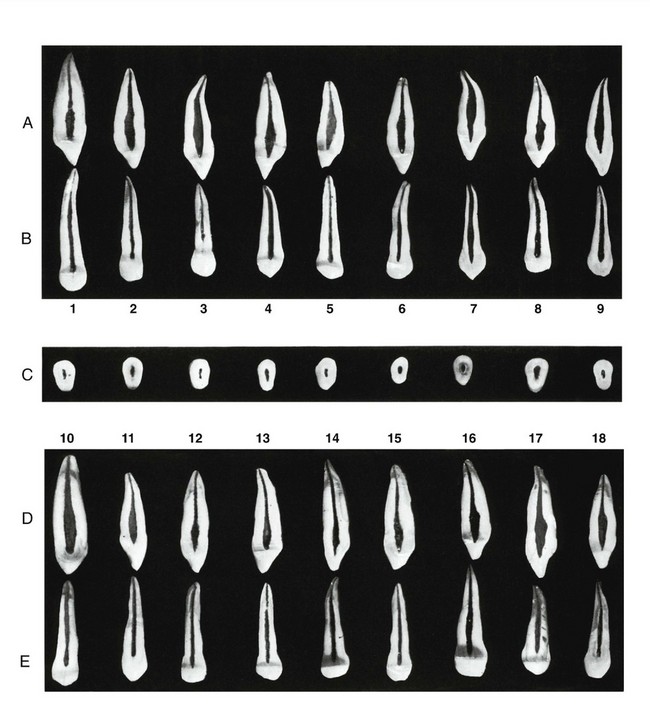

Labiolingual Section (Figure 13-10, A and D)

The maxillary canine has the largest labiolingual root dimension of any tooth in the mouth. Because the pulp cavity corresponds closely to the outline of the tooth, the size of the pulp chamber of this tooth may also be the largest in the mouth.

Figure 13-10 Maxillary canine. A, Labiolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the labial or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Cervical cross section at the cementoenamel junction exposing the pulp chamber. These are the openings to root canals that will be seen in the floor of the pulp chamber. D, Labiolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the labial or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The incisal aspect of the canine corresponds to the shape of the crown. If a prominent cusp is present, a long narrow projection from the pulp chamber (the pulp horn) will be present. The pulp chamber and incisal third or half of the root canal may be very wide, showing a very abrupt constriction of the root canal in the apical region, which then gently tapers toward the apex (Figure 13-10, A, 4, 5, 6, and 8; D, 16, 17, and 18). In other instances, a root canal may taper evenly from the pulp chamber to the apex of the root (Figure 13-10, A, 9; D, 10, 11, 13, and 14).

Some canines have severe curves in the apical aspect of the root (Figure 13-10, A, 3 and 7). The apical foramen may appear to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-10, A, 2 and 5 through 8; D, 11, 17, and 18) or labially to the apex of the root (Figure 13-10, A, 1, 3, and 4; D, 12 through 16).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-10, B and E)

The pulp cavity is much narrower in the mesiodistal aspect. The dimension and degree of taper of the pulp canal of the maxillary canine are very similar to those of the central and lateral incisors; however, the cuspid has a much longer root. The pulp cavity gently tapers from the incisal aspect to the apical foramen. A mesial or distal curve of the apical root may be present (Figure 13-10, B, 1, 4, 6, and 8; E, 14, 17, and 18). The apical foramen may appear to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-10, B, 1, 3 through 5, 7, and 9; E, 10, 11, 13, 14, 17, and 18) or slightly to the mesial or distal aspect of the root (Figure 13-10, B, 2, 6, and 8; E, 12, 15, and 16).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-10, C)

In cervical cross section, the shape of the root and pulp cavity is oval (Figure 13-10, C, 6, 7, and 9), triangular (Figure 13-10, C, 8), or elliptical (Figure 13-10, C, 1 through 5). The pulp chamber and canal are often centered within the crown and root (Figure 13-10, C, 1, 3, 4, and 9).

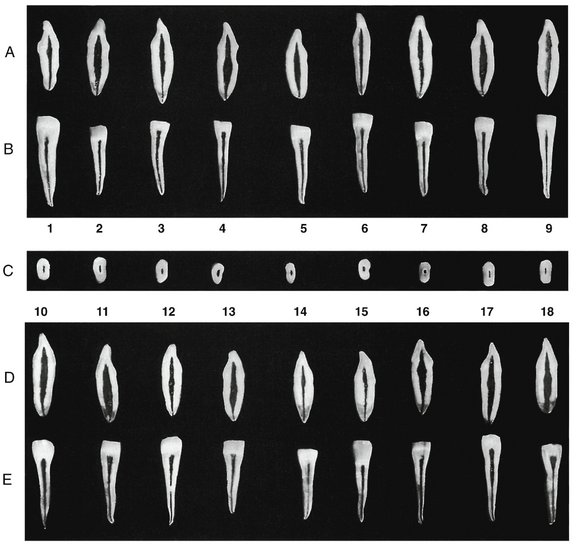

MAXILLARY FIRST PREMOLAR

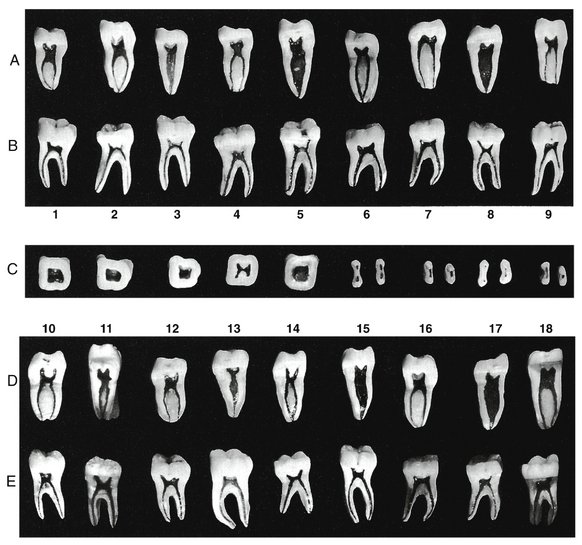

Buccolingual Section (Figure 13-11, A and D)

The maxillary first premolar may have two well-developed roots (Figure 13-11, A, 1, 2, and 9; D, 10 and 14), two root projections that are not fully separated (Figure 13-11, A, 3, 5, 7, and 8; D, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, and 17), or one broad root (Figure 13-11, A, 4 and 6; D, 18). The majority of maxillary first premolars have two root canals (Figure 13-11, A and D). A small percentage of maxillary first premolar teeth may have three roots that may be almost undetectable radiographically.

Figure 13-11 Maxillary first premolar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Cervical cross section at the cementoenamel junction exposing the pulp chamber. These are the openings to root canals that will be seen in the floor of the pulp chamber. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The pulp horn usually extends further incisally under the buccal cusp, because this cusp is usually better developed than the lingual cusp. The pulp horns may be blunted (Figure 13-11, A, 1, 5, and 6; D, 11) in teeth possessing cusps that demonstrate a fair amount of attrition. The pulp chamber floor is below the cervical level of all the variations found in the maxillary first premolar. The pulp chamber of teeth having the least root separation usually shows the largest incisal-apical dimension (Figure 13-11, A, 4; D, 18). Those teeth possessing a partial root separation may also have this large dimension (Figure 13-11, A, 8; D, 10). Teeth having two separate canals usually demonstrate a rather small pulp chamber in the incisal-apical direction (Figure 13-11, A, 1, 2, and 9; D, 11 and 14). The shape of the pulp chamber (excluding the pulp horns) tends to be square (Figure 13-11, A, 1 and 8; D, 10, 12, 13, 14, and 18) or rectangular (Figure 13-11, A, 2 through 7; D, 11, 15, 16, and 17).

The root canal often appears to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-11, A, 1, 4, 6, 7, and 8; B, 12, 13, and 15 through 18), slightly to the labial or lingual (Figure 13-11, A, 2), or a combination of the two locations (Figure 13-11, A, 3, 5, and 9; B, 10, 11, and 14).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-11, B and E)

The pulp horns appear blunted from the mesial or distal aspect, and the pulp chamber cannot be differentiated from the root canal. The pulp cavity tapers slightly from the occlusal aspect to the apical foramen. If two canals are present, the radiopacity will increase in the apical half of the tooth because of an increased amount of dentin and bone and a decrease in the volume of the pulp cavity.

The apical foramen appears to exit at the tip of the root most of the time (Figure 13-11, B, 1, 2, 3, and 6 through 9; E, 10 and 12 through 18), but some appear to exit on the mesial or distal aspects of the root (Figure 13-11, B, 4 and 5; E, 11).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-11, C)

The cross section at the cervical level shows the kidney-shaped outline form characteristic of the maxillary first premolar (Figure 13-11, C). A mesial developmental groove is usually present, giving this tooth its classic indentation. The pulp cavity may demonstrate a constriction adjacent to the developmental groove (Figure 13-11, C, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 9), or it may follow the general outline of the root surface (Figure 13-11, C, 1, 4, 7, and 8). Some roots demonstrate two separate root canals (Figure 13-11, C, 7), whereas a cross section of a three-rooted maxillary first premolar will show three separate canals (Figure 13-11, C, 3).

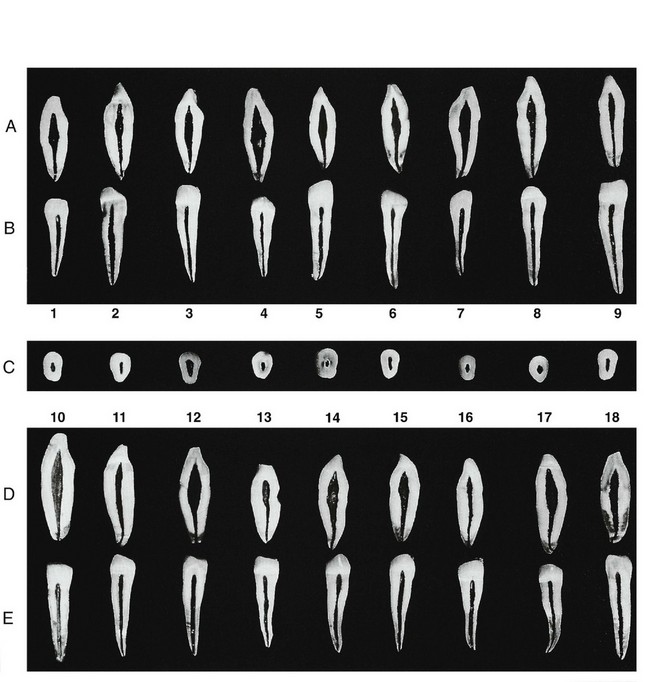

MAXILLARY SECOND PREMOLAR

Buccolingual Section (Figure 13-12, A and D)

Most maxillary second premolars have only one root and canal. Two roots are possible, although two canals within a single root may also be found.

Figure 13-12 Maxillary second premolar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Cervical cross section at the cementoenamel junction exposing the pulp chamber. These are the openings to root canals that will be seen in the floor of the pulp chamber. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The pulp cavity may demonstrate well-developed pulp horns (Figure 13-12, A, 1, 2, 6, 7, and 8; D, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, and 17); others may have blunted or nonexistent pulp horns (Figure 13-12, A, 3, 4, 5, and 9; D, 13, 15, and 18). The pulp chamber and root canal are very broad in the buccolingual aspect of teeth with single canals. The pulp cavity does not show a well-defined demarcation between the root cavity and the pulp cavity because of the large buccolingual extent of the pulp cavity in the upper half of the tooth. In the apical half or third of the tooth, the pulp cavity often narrows abruptly (Figure 13-12, A, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8; D, 11, 12, 13, and 18) and then tapers gently toward the apex. Some teeth possess dentinal islands in the apical third of the root; this situation essentially forces the clinician to treat these as teeth with two canals (Figure 13-22, A, 5; D, 15 and 17). Other maxillary second premolars have a canal that bifurcates at the apical third of the root (Figure 13-12, D, 10, 15, and 16). It should also be noted that buccal and lingual pulpal projections or fins are present at the level of the CEJ (Figure 13-12, A, 2; D, 12 and 18). Some teeth show a constriction at this same level (Figure 13-12, D, 10).

The apical foramen often appears to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-12, A, 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8; D, 11, 12, and 14 through 18). Some apical foramina appear to exit on the buccal aspect of the root (Figure 13-12, A, 4; D, 13), on the lingual aspect of the root (Figure 13-12, A, 7 and 9), or on both sides of the root tip (Figure 13-12, A, 3; D, 10 and 15).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-12, B and E)

The view of the pulp cavity in the mesiodistal section of the second maxillary premolar does not vary from that found in the maxillary first premolar. The pulp horns are blunted, and the pulp cavity tapers slightly from the occlusal aspect to the apex. The apical foramen may appear to be located off center of the root tip (Figure 13-12, A, 2, 6, and 9; D, 10 and 13) or appear to exit at the root tip (Figure 13-12, B, 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8; E, 11, 12, and 14 through 18).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-12, C)

The cervical cross section of the maxillary second premolar is usually oval (Figure 13-12, C, 2 and 4 through 9), with some teeth having a kidney-shaped cross section (Figure 13-12, C, 1 and 3). The pulp cavity is centered in the root and may have a constriction in the middle of the canal space (Figure 13-12, C, 1, 4, 6, and 9), an entire separation (Figure 13-12, C, 2), or an elliptical pulp cavity (Figure 13-12, C, 3, 5, 7, and 8).

MAXILLARY FIRST MOLAR

Buccolingual Section (Figure 13-13, A and D)

The buccolingual section of the maxillary first molar in Figure 13-13 shows the pulp cavities of the mesiobuccal and palatal root. These roots were chosen to demonstrate the pulp cavity anatomy because of the complexity of the mesiobuccal root. The distobuccal root is straighter and smaller and presents fewer variations in shape. The entire removal of the pulp is an impossibility in many maxillary first molar teeth because of the complexities of the root canal system (see Figure 13-7).

Figure 13-13 Maxillary first molar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Five cross sections at cervical line and four cross sections at midroot. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal aspect of the pulp cavity.

The maxillary first molar usually has three roots and three canals. The palatal root usually has the largest dimensions, followed by the mesiobuccal and distobuccal roots, respectively. The mesiobuccal root is often very wide buccolingually and usually possesses an accessory canal commonly called MB2, which usually is the smallest of all the canals in this tooth.

The pulp horns are usually prominent in this tooth (Figure 13-13, A, 1, and 4 through 8; D, 10 through 13, and 15 through 18). The pulp chamber is somewhat rectangular (excluding the pulp horns) when viewed from the mesial aspect of the tooth. The palatal root usually has the largest canal (Figure 13-13, A, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6; D, 10, 15, 17, and 18). The mesiobuccal canal is often very small (Figure 13-13, A, 2 and 6; D, 10, 14, and 17), but some mesiobuccal canals may be very wide within a very wide root (Figure 13-13, A, 9; D, 12 and 13).

The presence of an unmarked MB2 is strongly suggested when the root canal appears to be off to one side (Figure 13-13, A, 2, 6, and 8; D, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, and 18).

The root canals of the wide mesiobuccal roots are widest at the midroot level and taper to a very fine diameter at the apical foramen. The palatal root canal and the mesiobuccal root canal of most teeth taper gently to the apical region, where they terminate at or near the apex. The apical foramen of the palatal canal may appear to exit at the apex (Figure 13-13, A, 1, and 4 through 9; D, 11 through 17), slightly lingually (Figure 13-13, A, 2; D, 10) or buccally to the root tip (Figure 13-13, A, 3; D, 18).

The apical foramen of the mesiobuccal canal may appear to exit on the tip of the root (Figure 13-13, A, 2 through 5, 7, 8, and 9; D, 10, 12, 13, 17, and 18) or on the buccal (Figure 13-13, A, 1 and 6; D, 14 and 15) or lingual (Figure 13-13, D, 16) aspect of the root.

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-13, B and E)

The mesiodistal section of the maxillary first molar includes the distobuccal root, which was not visible on the previously mentioned buccolingual section. The mesiobuccal root has a great tendency to possess a more curved root and canal than the distobuccal root (Figure 13-13, B, 1 through 8; E, 12, 14, and 15). Some of the buccal canals are relatively straight (Figure 13-13, E, 10, 11, and 13).

The pulp horns are very distinct from this view, with the mesiobuccal pulp horn usually appearing a little larger than the distobuccal pulp horn (Figure 13-13, B, 1 and 3 through 9; E, 10 through 13 and 15 through 18). In some teeth, the pulp horns are of equal size (Figure 13-13, B, 2; E, 14). The pulp chamber is somewhat square (if the pulp horns are excluded) when viewed from the buccal aspect. The demarcation of the root canal is much more distinct in the mesiodistal section. The root canals appear much smaller when viewed from the buccal or lingual aspect. The canals taper slightly as they approach the apical foramen. The apical foramen often appears to be located at the tip of the root (Figure 13-13, B, 1 through 7 and 9; E, 11, 14, 16, and 18), but the apical foramen may appear to be located on the mesial (Figure 13-13, E,10 and 17, mesial root only) or on the distal aspect of the root (Figure 13-13, B, 8; E, 12 and 13, distal root only).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-13, C)

The cervical outline form of the maxillary first molar is rhomboidal with rounded corners (Figure 13-13, C, 1 through 5). The mesiobuccal angle has an acute angle, the distobuccal angle is obtuse, and the lingual angles are essentially right angles. The orifices of the root canals have the following relation to the floor of the pulp chamber.

The palatal canal is centered lingually; the distobuccal canal is near the obtuse angle of the pulp chamber; the mesiobuccal root canal is buccal and mesial to the distobuccal canal, in what seems to be the extreme corner, positioned within the acute angle of the pulp chamber. If an accessory mesiobuccal canal (MB2) is present, it will be located lingual to the mesiobuccal canal. The canals of this tooth form a triangular pattern; a line drawn between the mesiobuccal canal and the palatal canal makes the base of the triangle, and the distobuccal canal, which is slightly closer to the palatal canal, makes the third point of the triangle. If a mesiobuccal accessory canal is present, it will be between the mesiobuccal and palatal canal just off an imaginary line between the two canals (Figure 13-13, C, 7, 8, and 9). The MB2 may even be mesial to a line connecting the mesiobuccal and the palatal canals (Figure 13-13, C, 8).

Midroot Cross Section (Figure 13-13, C)

The midroot sections were added to the molar descriptions because some molars possess more than one canal within the root (Figure 13-13, C, 6 through 9). The palatal root is usually the largest root having a round outline form. The distobuccal canal is oval to round but much smaller than the palatal root. The mesiobuccal root is an elongated oval to kidney-shaped root with the indentation located toward the furcation. The root canals of the palatal and distobuccal root are oval to round, whereas the mesiobuccal canals are elongated (Figure 13-13, C, 6 and 9), elliptical (Figure 13-13, C, 7), or round (Figure 13-13, C, 8 and 9). The pulp canals may be extremely difficult to locate and instrument if secondary or irritation-induced dentin is abundant (Figure 13-13, C, 9). A thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the pulp chambers and canals is necessary if endodontic procedures are to be accomplished.

MAXILLARY SECOND MOLAR

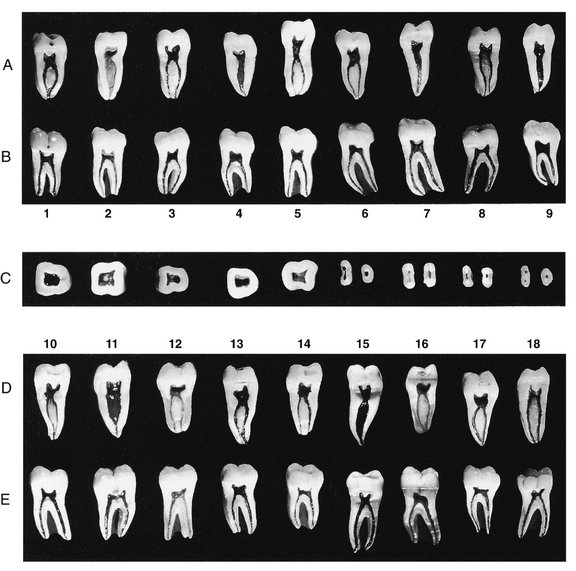

Buccolingual Section (Figure 13-14, A and D)

The buccal roots of the maxillary second molar are straighter and closer together than those of the maxillary first molar. The tendency for root fusion is greater in the second maxillary molar than in the first maxillary molar, but the palatal root is usually separate. Most often maxillary second molars possess three roots and three canals.

Figure 13-14 Maxillary second molar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Five cross sections at cervical line and four cross sections at midroot. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The mesiobuccal root of the maxillary second molar is not as complex as that formed in the maxillary first molar. The tendency for a very wide mesiobuccal canal is not present in the maxillary second molar. The presence of two canals in the mesiobuccal root is not as common in the maxillary second molar as in the maxillary first molar; however, it does occur (Figure 13-14, A, 5 and 7).

The pulp horns may be well developed (Figure 13-14, A, 1 through 3, 5, 8, and 9; D, 10 through 18) or virtually absent (Figure 13-14, A, 4, 6, and 7). The pulp chamber appears somewhat rectangular (excluding the pulp horns). The pulp canals gradually taper toward the apex until reaching the apical constriction, which occurs just before the apical foramen.

The mesiobuccal root canal of the maxillary second molar does not have the tendency to be extremely large, as is demonstrated in the mesiobuccal canal of the maxillary first molar. The apical foramen of the palatal root often appears to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-14, A, 1, 2, 3, and 5 through 8; D, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, and 18), but it may exist on the lingual (Figure 13-14, A, 4 and 9; D, 15) or buccal aspect of the root (Figure 13-14, D, 10 and 12).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-14, B and E)

The mesiodistal section of the maxillary second molar is similar to that of the maxillary first molar. The buccal roots of the second molar are not as far apart as they are in the maxillary first molar, and their buccal roots have a greater tendency to be fused.

The pulp horns are usually well developed (Figure 13-14, B, 1 through 5, 8, and 9; E, 10 through 15 and 17). Some teeth demonstrate an obvious blunting or absence of the pulp horns (Figure 13-14, B, 6 and 7; E, 18). The mesiobuccal pulp horn is often larger than the distobuccal pulp horn (Figure 13-14, B, 1, 4, 5, 8, and 9; E, 10, 12, 13, 15, 17, and 18).

The pulp chamber appears much smaller in the mesiodistal section than in the buccolingual section. The pulp chamber is square (excluding the pulp horns) when viewed from the buccal aspect. The pulp canals gently taper from the pulp chamber to the apical constriction. The mesiobuccal pulp canal has a greater tendency to be curved than the distobuccal canal. The majority of the apical foramen appears to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-14, B, 1, 2, and 4 through 9; E, 10 through 16 and 18).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-14, C)

The cervical cross section of the maxillary second molar demonstrates angulations of the outline form that are more extreme than those found in the maxillary first molar. The mesiobuccal angle is more acute and the distobuccal angle is more obtuse than that found in the maxillary first molar, and the outline form of the pulp chamber reflects these differences.

The mesiobuccal canal orifice is located farther to the buccal and mesial aspect of the pulp chamber (Figure 13-14, C, 4 and 5). The distobuccal canal more nearly approaches the midpoint between the mesiobuccal and palatal canal (Figure 13-14, C, 4). The palatal canal is located at the most lingual aspect of the root.

Because of the tendency for the roots to be fused or at least closer together, the orifices of the root canals are much closer together in the maxillary second molar than in the maxillary first molar (Figure 13-14, C, 4). In the cervical cross section, the triangularity of the floor of the pulp chamber is clearly demonstrated.

Midroot Cross Section (Figure 13-14, C)

The palatal root of the maxillary second molar may be the largest of the three roots (Figure 13-14, C, 7 and 8). The mesiobuccal root may have a larger buccolingual dimension, but it has a narrower mesiodistal dimension. The distobuccal canal is the smallest root of the three.

The distobuccal root and the palatal root have a round or oval outline form. The mesiobuccal root is usually rectangular with rounded corners. If one canal is present, the canal follows the outline form of the root and is usually narrower at the middle of the root, which makes the canal appear as two canals (Figure 13-14, C, 7). If two separate canals are present, they are usually round (Figure 13-14, C, 8).

MAXILLARY THIRD MOLAR

The maxillary third molar has the most variable anatomy of any of the maxillary teeth. A description of the pulpal anatomy will not be provided because of the tremendous variability of the maxillary third molar. A sample of longitudinal and cross sections, displayed in the same manner as for all the other maxillary teeth, shows a comparison of this molar with the other maxillary molars (Figure 13-15). When the maxillary third molar is compared in development and eruption with the other maxillary molars, it is evident that the third molar is smaller than the other molars. The crown is usually triangular or round rather than quadrilateral. The roots are shorter, more curved, and have a greater tendency for root fusion, which makes these teeth appear to be single rooted (Figure 13-15, A, 8; B, 3, 5, and 8; D, 10 and 12; E, 11 through 14, and 16). Because the maxillary third molar is 8 or 9 years younger than the first molar, the pulp chamber will have less secondary dentin than the older first and second molars. This allows easier access to the canals. However, because of the higher incidence in malformations of the roots, the endodontic procedure may be very difficult.

Figure 13-15 Maxillary third molar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear in dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Five cross sections at cervical line and four cross sections at midroot. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

Third molars have generally been condemned without fully appreciating their possible usefulness in later years. If these teeth can be managed well and are functioning, they should be maintained, because they can provide suitable support for restorative procedures in later years.

Pulp Cavities of the Mandibular Teeth

MANDIBULAR CENTRAL INCISOR

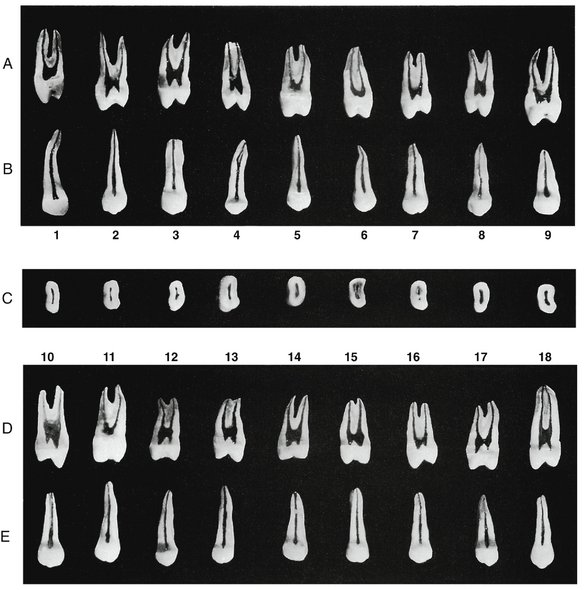

Labiolingual Section (Figure 13-16, A and D)

The mandibular central incisor is the smallest tooth in the mouth, but its labiolingual dimension is very large. This tooth usually has one canal; two canals may be found, but not very frequently. The pulp horn is well developed in this tooth (Figure 13-16, A, 1 through 6 and 8; D, 10 through 18). As attrition occurs, reactive dentin is produced that will essentially move the pulp tissue farther from the original location of the external surface of the tooth (Figure 13-16, A, 9). The pulp chamber may be very large (Figure 13-16, A, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8; D, 10, 11, 13, and 17), intermediate in size (Figure 13-16, A, 3, 5, 7, and 9; D, 12, 14, and 15), or very small (Figure 13-16, D, 16 and 18).

Figure 13-16 Mandibular central incisor (first incisor). A, Labiolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the labial or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Cervical cross section at the cementoenamel junction exposing the pulp chamber. These are the openings to root canals that will be seen in the floor of the pulp chamber. D, Labiolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the labial or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The pulp canal may taper gently to the apex (Figure 13-16, A, 2, 3, and 7; D, 10, 11, 14, 16, and 18) or narrow abruptly in the apical 3 to 4 mm of the root (Figure 13-16, A, 1, 4, 5, 6, and 8; D, 12, 13, 15, and 17).

The apical foramen may appear to exit at the apex (Figure 13-16, A, 1, 4, 6, 7, and 9; D, 11, 12, 15, 16, and 18) or on the buccal aspect of the root (Figure 13-16, A, 2, 3, 5, and 8; D, 10, 13, 14, and 17).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-16, B and E)

A buccal or facial view of a mesiodistal section of the mandibular central incisor demonstrates the narrowness of the pulp cavity. A small endodontic file can generally be used to negotiate these canals in spite of this narrowness, because of the wide labiolingual dimension of the pulp chamber. However, secondary or tertiary (irritation-induced) dentin may interfere with endodontic treatment (Figure 13-16, D, 16 and 18; E, 13 and 18).

The pulp horn is usually prominent but single. The canal also appears narrow, having a gentle taper from the pulp chamber to the apical constriction. The canal may exit at the apex (Figure 13-16, B, 2, 5, and 8; E, 12, 14, 16, and 17) or mesially or distally to the apex of the root (Figure 13-16, B, 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 9; E, 10, 11, 13, 15, and 18).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-16, C)

The cervical cross section demonstrates the proportions of the root. The mesiodistal dimension is small, whereas the labiolingual dimension is very large. The external shape is variable; it may be round, oval, or elliptical. The more nearly round the root, the more nearly round the canal (Figure 13-16, C). Two separate canals may be present, or a dentinal island may make it appear as though two canals are present (Figure 13-17).

MANDIBULAR LATERAL INCISOR

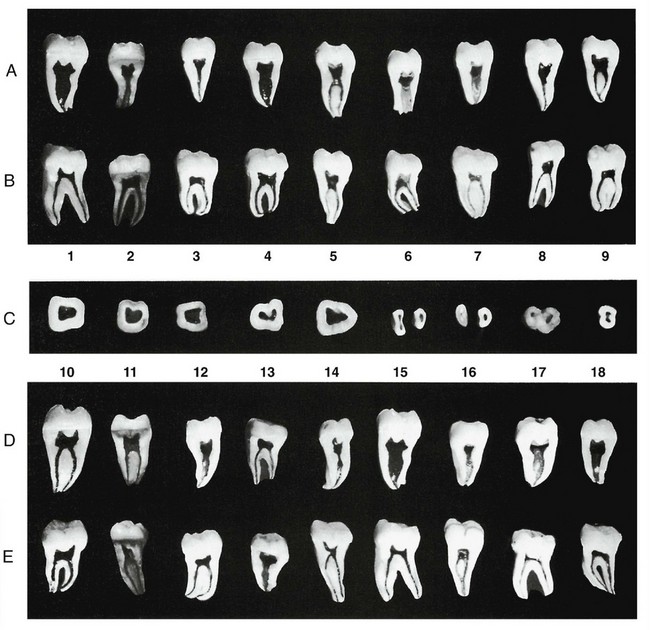

Labiolingual Section (Figure 13-18, A and D)

The mandibular lateral incisor tends to be a little larger than the mandibular central incisor in all dimensions, and the pulp chamber is also larger. The form and function of the mandibular lateral incisor are identical to those of the central incisor.

Figure 13-18 Mandibular lateral incisor (second incisor). A, Labiolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the labial or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Cervical cross section at the cementoenamel junction, exposing the pulp chamber. These are the openings to root canals that will be seen in the floor of the pulp chamber. D, Labiolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the labial or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The pulp horn is usually prominent. The pulp chamber may possess a dimension that is very large (Figure 13-18, A, 2, 4, 5, 8, and 9; D, 10, 11, 16, 17, and 18), intermediate in size (Figure 13-18, A, 1, 3, 6, and 7; D, 12), or small (Figure 13-18, D, 14 and 15). The pulp canal may taper gently from the apex (Figure 13-18, A, 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, and 9; D, 12, 14 through 17) or narrow abruptly in the last 3 to 4 mm of the canal (Figure 13-18, A, 3, 5, and 8; D, 10 through 13). The apical foramen may appear to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-18, A, 1 through 6, 8, and 9; D, 12 through 15, 17, and 18) or on the buccal or lingual aspect of the root tip (Figure 13-18, A, 7; D, 10, 11, and 16).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-18, B and E)

The pulp chamber and canal, as viewed from this aspect, will demonstrate a slender cavity. The mandibular lateral incisor resembles the mandibular incisor, but it may appear a little wider and have a pulpal dimension that is larger. The pulp horns are prominent, and the pulp chamber and canal gently taper to the apex. The apical foramen may appear to exit at the tip (Figure 13-18, A, 1, 2, 3, 6, and 9; D, 12 through 15, 17, and 18) or on the mesial or distal aspect of the root tip (Figure 13-18, A, 5, 7, and 8; D, 10, 11 and 16).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-18, C)

The cervical cross section of the mandibular lateral incisor shows the pulp canal centered in the root. A comparison of several of the sections demonstrates a root somewhat larger than that of the mandibular central incisor. Considerable variation is evident in the form of the root. The root outline form is oval to elliptical. Some cross sections of the larger teeth resemble the cervical cross sections of small mandibular canines (Figure 13-18, C, 2, 3, and 4). The root canal follows the outline form of the root, and some roots demonstrate root grooves (Figure 13-18, C, 6).

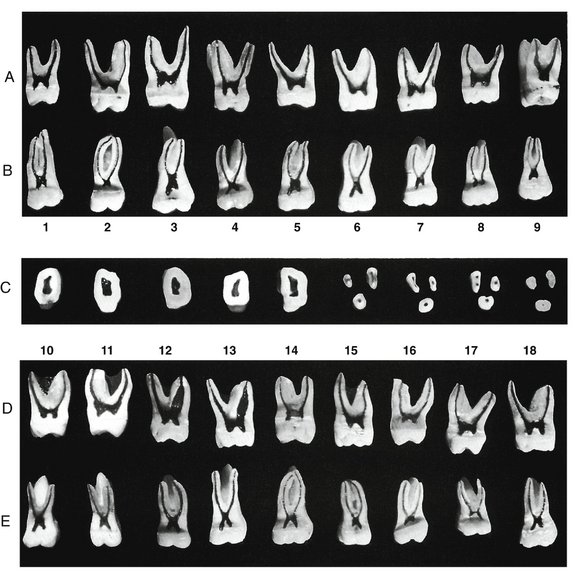

MANDIBULAR CANINE

Labiolingual Section (Figure 13-19, A and D)

The pulp cavity of the mandibular canine is similar in size and shape to that of the maxillary canine. The mandibular canine tends to be a little shorter, although the opposite can be found. It is not uncommon to find two roots or at least two canals in the mandibular canine. A dentinal island may be found in any tooth that demonstrates an extremely wide labiolingual dimension and a narrow mesiodistal dimension. Because the presence of two canals cannot be easily detected radiographically, their presence must be ruled out clinically as well. The pulp cavity in a tooth of this kind varies according to where the section is examined (see Figure 8-24, 1, 2, 5, and 6).

Figure 13-19 Mandibular canine. A, Labiolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the labial or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Cervical cross section at the cementoenamel junction, exposing the pulp chamber. These are the openings to root canals that will be seen in the floor of the pulp chamber. D, Labiolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the labial or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The pulp horn is prominent in the mandibular canine unless an extensive amount of attrition has taken place (Figure 13-19, A, 1 and 3). The pulp chamber usually is very wide (Figure 13-19, A, 1, 3, 4, 5, and 7; D, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, and 18) but may be average to small (Figure 13-19, A, 2, 6, and 9; D, 11, 13, and 16).

Some mandibular canines demonstrate an abrupt narrowing of the pulp cavity when passing from the region of the pulp chamber to the region of the pulp canal (Figure 13-19, A, 8; D, 13). Other mandibular canines demonstrate an abrupt narrowing of the pulp canal in the apical region (Figure 13-19, A, 1 through 6; D, 11, 12, and 18), after which the canal gently tapers to the apex. If an abrupt narrowing of the canal is absent, the tooth will demonstrate a canal that gently tapers to the apical foramen.

The apical foramen often appears to exit at the tip of the apex (Figure 13-19, A, 3, 5, 7, and 9; D, 10, 12, 14 through 16), slightly buccally (Figure 13-19, A, 1, 2, 6, and 8; D, 11, 13, and 17), or lingually to the root tip (Figure 13-19, D, 18).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-19, B and E)

The mesiodistal cross section of the mandibular canine appears very similar to that of the maxillary canine. The mesiodistal section demonstrates how narrow this tooth is in the mesiodistal aspect. This view also shows the degree of curvature of the apical portion of the root. The curvature of the root canal may be in the mesial direction (Figure 13-19, E, 17). The pulp horn is usually prominent but appears blunted in this view. The pulp chamber and canal show a continuous gentle taper to the apex, where the apical foramen appears to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-19, B, 1 through 4; E, 10, 11, 13, 15, and 17) or slightly mesially or distally to the root tip (Figure 13-19, B, 5 through 7; E, 12, 14, and 18).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-19, C)

A cervical cross section of the mandibular canine shows considerable variation in size and shape (Figure 13-19, C, 1 through 9). The outline form of the root may be oval (Figure 13-19, C, 1, 4, 7, and 8), rectangular (Figure 13-19, C, 2, 5, 6, and 9), or triangular (Figure 13-19, C, 3). The size and shape of the canal are also variable. The pulp cavity outline form closely resembles the root form.

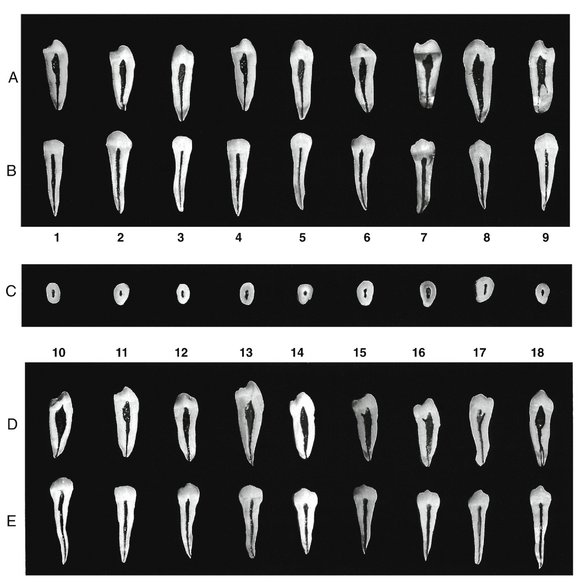

MANDIBULAR FIRST PREMOLAR

Buccolingual Section (Figure 13-20, A and D)

The mandibular first premolar looks like a small mandibular canine with an extra small cusp. The pulp cavity also looks similar to that of the mandibular canine. The majority of these teeth have one canal, but two or three canals are possible (Figure 13-20, A, 9; D, 18).

Figure 13-20 Mandibular first premolar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Cervical cross section at the cementoenamel junction, exposing the pulp chamber. These are the openings to root canals that will be seen in the floor of the pulp chamber. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The pulp horn of the buccal cusp is prominent in some teeth (Figure 13-20, A, 1, 2, 4, and 6 through 9; D, 10 through 18). The pulp horn of the lingual cusp may be prominent but small (Figure 13-20, D, 15, 16, and 17) or vestigial (Figure 13-20, A, 1, 4, and 6 through 9; D, 10, 11, and 12), or it may be completely absent (Figure 13-20, A, 2, 3, and 5; D, 14 and 18).

The pulp chamber is usually very large. The pulp cavity may taper gently toward the apex (Figure 13-20, A, 2, 3, 5, and 6; D, 12 and 13) or abruptly as the root canal starts (Figure 13-20, A, 1, 4, and 7; D, 11, 17, and 18), or it may gently and abruptly constrict in the apical region (Figure 13-20, A, 2 and 8; D, 10, 14, 15, and 16).

The apical foramen usually appears to exit at the apex (Figure 13-20, A, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 9; D, 10 through 13, and 18) or slightly to the buccal (Figure 13-20, A, 8; D, 14, 15, and 16) or lingual aspect of the root tip (Figure 13-20, A, 1 and 4; D, 17).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-20, B and E)

The pulp horn is prominent and may be very fine at its occlusal extent (Figure 13-20, B, 6 and 9; E, 12 and 18). The pulp chamber and root canal taper gently to the apex.

The apical foramen may appear to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-20, B, 3, 5, 8, and 9; E, 11, 14, 17, and 18) or on the buccal or lingual aspect of the root (Figure 13-20, B, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7; E, 10, 12, 13, 15, and 16).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-20, C)

The crown and root size of the mandibular premolars vary considerably, and the pulp cavities vary proportionately. The outline form of the root may be oval (Figure 13-20, C, 2, 6, and 9), rectangular (Figure 13-20, C, 1, 3, and 4), or triangular (Figure 13-20, C, 5, 7, and 8).

The pulp cavity may be rounded (Figure 13-20, C, 5), elliptical (Figure 13-20, C, 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 9), or triangular (Figure 13-20, C, 7), depending on the external shape of the root. If two separate canals are present and the cross section is below the bifurcation level, two or three round canals would be seen rather than elliptical or ribbon-shaped canals.

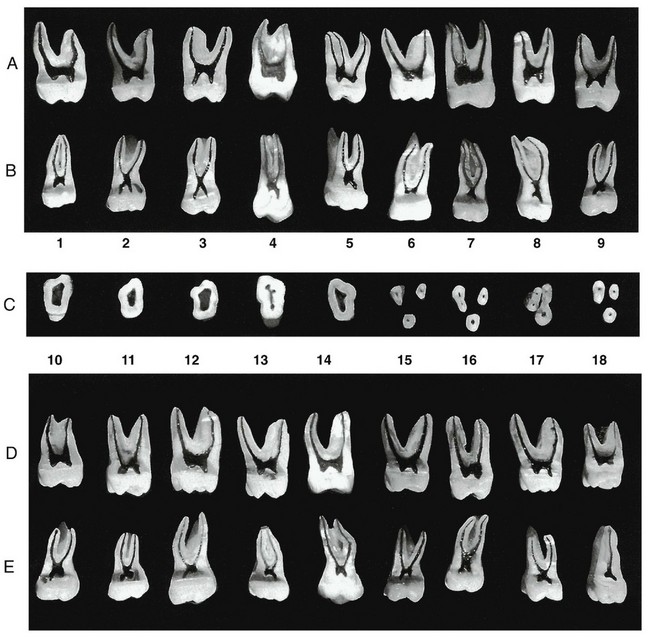

MANDIBULAR SECOND PREMOLAR

Buccolingual Section (Figure 13-21, A and D)

The mandibular second premolar has a larger crown and root than the first premolar. The dimensions of the pulp cavities are increased, but the extremely wide dimensions are confined to the crown and the upper portion of the root canal. Another difference between the first and second premolar is that the pulp horns in the second premolar tend to be more prominent and the lingual pulp horn is present more often.

Figure 13-21 Mandibular second premolar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Cervical cross section at the cementoenamel junction, exposing the pulp chamber. These are the openings to root canals that will be seen in the floor of the pulp chamber. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The pulp horns are prominent in most of the teeth (Figure 13-21, A, 1, 2, 3, 7, and 9; D, 10, 13, 16, and 17), but the lingual pulp horn may be vestigial (Figure 13-21, A, 4, 5 and 6; D, 11, 12, 14, 15, and 16) or nonexistent (Figure 13-21, A, 8).

The pulp chambers are usually large and may abruptly constrict (Figure 13-21, A, 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8; D, 11, 13, 14, 16, and 18) or gently taper into the pulp canal (Figure 13-21, A, 1, 3, 6, and 9; D, 10, 12, 15, and 17).

The apical foramen may appear to exit at the apex (Figure 13-21, A, 1 through 6, 8, and 9; D, 10 through 14, 16, and 17) or on the buccal or lingual aspect of the root tip (Figure 13-21, A, 7; D, 15 and 18).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-21, B and E)

The mandibular second premolar is very similar to the mandibular first premolar, except that the overall dimensions of the second premolar are slightly larger. In general, the mesiodistal cross section of the mandibular premolars and the canine are similar. The mandibular second premolar usually has one root and canal that may be curved, but usually in the distal direction.

The pulp horns are prominent, and the pulp chamber and root canal gently taper toward the apex. The apical foramen appears to exit at the tip of the root in the majority of cases.

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-21, C)

The amount of root structure is substantial in the mandibular second premolar, as is clearly demonstrated in the cervical cross section. The outline form of the root is rectangular (Figure 13-21, C, 1, 3, 6, 8, and 9), oval (Figure 13-21, C, 4 and 7), or triangular (Figure 13-21, C, 2 and 5).

The pulp cavity generally follows the outline of the tooth unless multiple canals are present (Figure 13-21, C, 6).

MANDIBULAR FIRST MOLAR

Buccolingual Section (Figure 13-22, A and D)

The buccolingual cross section of the mandibular first molar demonstrates a large pulp chamber that may extend well down into the root formation (Figure 13-22, A, 1 and 2; D, 16 and 18). The mesial root usually has a more complicated root canal system because of the presence of two canals. The distal root usually has one large canal, but two canals are often present. Occasionally, a fourth canal is present that has its own separate root.

Figure 13-22 Mandibular first molar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Five cross sections at cervical line and four cross sections at midroot. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

The pulp horns are quite prominent in most mandibular first molars (Figure 13-22, A, 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9; D, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, and 18), but the pulp horns of some of mandibular first molars are quite small (Figure 13-22, A, 3, 4, and 7; D, 13 and 16). The pulp chambers of the mesial roots are square to rectangular (excluding the pulp horns) (Figure 13-22, A, 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, and 9; D, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, and 18), but this configuration is not seen in a root with a single canal (Figure 13-22, A, 3 and 8; D, 13, 15, and 17).

One or both of the mesial canals may be significantly curved (Figure 13-22, A, 1 and 2; D, 16 and 18), moderately curved (Figure 13-22, A, 4 and 6; D, 10, 12, and 14), or relatively straight (Figure 13-22, A, 7 and 9). The two canals may join each other in the apical region to exit in a common foramen (Figure 13-22, A, 1, 2, and 6; D, 14), or they may have separate apical foramina (Figure 13-22, A, 4, 7, and 9; D, 10, 12, 16, and 18).

The apical foramen usually appears to exit on the tip of the broad mesial root (Figure 13-22, A, 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, and 9; D, 10, 14, and 16), but in some roots one of the two canals exits on the side of the root tip (Figure 13-22, D, 12 and 18). The diameter of the mesial canals is usually very small and demonstrates a slight taper.

The distal root usually has one large pulp chamber, which is very wide in the buccolingual dimension (Figure 13-22, A, 3, 5, and 8; D, 15 and 17), whereas other distal roots may possess a pulp chamber that is more constricted (Figure 13-22, D, 11 and 13). The distal root usually has one large pulp canal, which may show a considerable buccolingual dimension until the canal constricts abruptly a few millimeters from the apex of the root (Figure 13-22, A, 3, 5 and 8; D, 17). A constriction of the canal in the last few millimeters of the root is not always present (Figure 13-22, D, 15). When two canals are present, they will be partially or completely separated by a dentinal island (Figure 13-22, D, 11). The apical foramen of a root with a single canal usually appears to be located at the apex of the root (Figure 13-22, A, 3 and 8; D, 13), but it may be slightly buccal or lingual to the apex of the root (Figure 13-22, A, 5; D, 15 and 17).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-22, B and E)

The mesiodistal section of the mandibular first molar presents few variations in the form of the pulp chamber or canals. The mesial and distal pulp cavities have canals and chambers that are centered within the roots and crowns.

The pulp horns may be prominent (Figure 13-22, B, 8; E, 11, 14, and 15), moderately evident (Figure 13-22, B, 2, 3, 6, and 7; E, 12), or barely detectable (Figure 13-22, B, 4; E, 13 and 16), or may demonstrate a combination of these variations (Figure 13-22, B, 1 and 9; E, 17 and 18).

The pulp chambers are usually rectangular (excluding the pulp horns) and may be large (Figure 13-22, B, 1, 4 through 7, and 9; E, 10 through 18), or very small (Figure 13-22, B, 2, 3, and 8).

The mesial root and canal usually show considerable curvature (Figure 13-22, B, 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 9; E, 12, 13, 15, 16, and 18). Some canals demonstrate less curvature (Figure 13-22, B, 6; E, 10, 11, 14, and 17). Extensive secondary or reactive dentin deposition may also be seen (Figure 13-22, B, 2).

The apical foramen usually appears to exit at the tip of the root (Figure 13-22, B, 1, 5, 7, and 8; E, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, and 17) but may appear to exit on the mesial (Figure 13-22, B, 2, 4, 6, and 9; E, 16) or on the distal aspect of the root (Figure 13-22, B, 3).

The distal root is usually straighter and tends to be a little shorter than the curved mesial root (Figure 13-22, B, 1, 3, 6, and 8; E, 12, 14, and 15); however, it may be the same length (Figure 13-22, B, 2, 4, and 7; E, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, and 18) or even slightly longer (Figure 13-22, B, 5 and 9). The distal canal is usually larger than the mesial canal (Figure 13-22, B, 2, and 4 through 7; E, 11, 14, 15, 16, and 18), but the canals may look very similar in size when viewed from the buccal aspect (Figure 13-22, B, 1, 3, 8, and 9; E, 10, 12, 13, and 17).

The distal canal usually tapers gently to the apical constriction. The apical foramen most often appears to be located on the distal aspect of the root (Figure 13-22, B, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 8; E, 13, 16, and 17). In some teeth, this distal deviation is quite marked (Figure 13-22, B, 5 and 7; E, 13 and 17). Mesial deviation of the canal does occur (Figure 13-22, B, 6); however, it is usually only a minor deviation. The apical foramen of the distal root will often appear to be located at the tip of the root (Figure 13-22, B, 1; E, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, and 18).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-22, C, 1 through 5)

The cervical cross section of the mandibular first molar is generally quadrilateral in form. Distally, it tapers a little from the wider buccolingual measurement of the mesial aspect of the tooth. The pulp chamber outline generally follows that of the root (Figure 13-22, C, 1, 2, and 5) but may show buccal (Figure 13-22, C, 3) and/or lingual (Figure 13-22, C, 4) projections of dentin if the pulp chamber is excessively narrowed by secondary or reactive osteodentin.

The pulp chamber floor has two small funnel-shaped openings into the mesial root (one buccal and one lingual), whereas the distal aspect of the pulp chamber usually shows a single opening that is less constricted.

Midroot Cross Section (Figure 13-22, C, 6 through 9)

The midroot view of the mandibular molar usually demonstrates the root canal form, which is consistent with the major form of this tooth.

The mesial root usually is somewhat kidney-shaped, with two separate canals (Figure 13-22, C, 7 and 9), but a figure-eight shape of the root is also very common (Figure 13-22, C, 6 and 8). The two canals may be totally separate (Figure 13-22, C, 6 and 8), or one may be confluent with the other canal (Figure 13-22, C, 7 and 9). Even three canals may be found in this root on occasion.

The distal root is usually rounder than the mesial root (Figure 13-22, C, 7 and 9), but a very wide root is also common (Figure 13-22, C, 6 and 8). Those roots that tend to be round usually demonstrate only one canal, whereas the broader distal roots tend to have two canals (Figure 13-22, C, 6 and 8) or a very thin canal that is single; or they may possess a dentinal island (Figure 13-22, C, 8). Even in a root with a single canal, the distal canal tends to show a developmental depression or concavity on the mesial aspect of the root (Figure 13-22, C, 7 and 9).

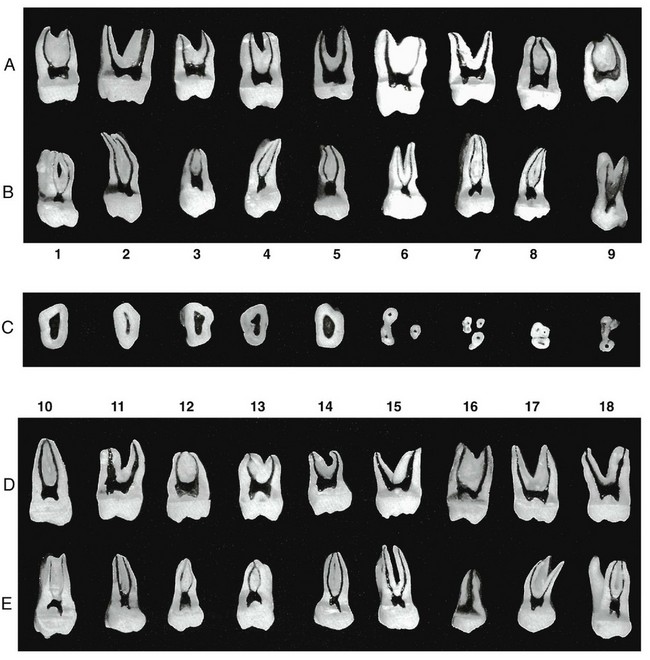

MANDIBULAR SECOND MOLAR

Anatomically, the mandibular second molar has many similarities with the mandibular first molar (Figure 13-23). The proportions of the crown and root are very similar to those of the mandibular first molar. The roots of the second molar may be straighter with less divergence from the furcation than in the first molar. The roots may be shorter, but there is no assurance that any of these differences will be manifested in any one tooth.

Figure 13-23 Mandibular second molar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Five cross sections at cervical line and four cross sections at midroot. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal aspect of the pulp cavity.

Buccolingual Section (Figure 13-23, A and D)

The buccolingual section of the mandibular second molar demonstrates a pulp chamber and pulp canals that tend to be more variable and complex than those found in the mandibular first molar.

The pulp horns of the mandibular second molar are usually rather prominent (Figure 13-23, A, 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9; D, 10, 13, 14, 15, 17, and 18), but some pulp horns may be small to nonexistent (Figure 13-23, A, 2, 4, and 7; D, 11, 12, and 16). The pulp chamber of the mesial root (Figure 13-23, A, 1, 3, 5, 6, and 8; D, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, and 18) is well demarcated because of the presence of two canals. The pulp chamber (excluding the pulp horns) may be somewhat square (Figure 13-23, A, 1, 3, and 8; D, 10, 12, 14, 16, 17, and 18) or rectangular (Figure 13-23, A, 5 and 6; D, 13).

Two root canals are usually present in the mesial root, but only one may be present. The mesial canals may be large (Figure 13-23, A, 1; D, 17 and 18), medium (Figure 13-23, A, 3, 5, 6, and 8; D, 13), or small (Figure 13-23, D, 12, 14, and 16). The curvature of these canals may be severe (Figure 13-23, A, 1; D, 13), moderate (Figure 13-23, A, 5 and 8; D, 12 and 16), virtually absent (Figure 13-23, D, 14 and 18), or a combination of the aforementioned variations (Figure 13-23, A, 3 and 6; D, 17). Most of the canals appear to exit from the mesial root separately (Figure 13-23, A, 3, 5, 6, and 8; D, 12, 13, 14, 16, and 18), but some join just before reaching the apex so that a common canal exits from the apex (Figure 13-23, A, 1; D, 17).

The apical foramen usually appears to be located at the tip of the root (Figure 13-23, A, 1, 3, and 6; D, 12, 17, and 18), but some appear to exit slightly to the buccal or lingual aspect of the apex of the root (Figure 13-23, A, 5 and 8; D, 14 and 16).

The pulp chamber of the distal root of the mandibular second molar is not as easily identified because of the extremely large pulp canal that is usually present (Figure 13-23, A, 2, 4, 7, and 9; D, 11 and 15). One canal is usually present in the distal root, but two totally or partially separate canals are possible (Figure 13-23, D, 10).

Pulp horns may be present, but they are not nearly as prominent as in the mesial root (Figure 13-23, A, 2, 4, 7, and 9; D, 11 and 15) unless two canals are present (Figure 13-23, D, 10).

The pulp canal is usually very large in the mesiobuccal sections. The pulp canal may taper gently from the pulp chamber until the apical constriction (Figure 13-23, A, 2 and 7; D, 10 and 15), or an abrupt constriction of the canal may occur in the last 2 to 3 mm of the canal (Figure 13-23, A, 4 and 9; D, 11). The apical foramen often appears to be located at the tip of the root (Figure 13-23, A, 1, 4, 7, and 9; D, 10, 11, and 15).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-23, B and E)

The mesiodistal sections of the mandibular second molar are very similar to those of the mandibular first molar. However, the roots of the mandibular first molar tend to be straighter and closer together (less furcation deviation).

The pulp horns are usually prominent (Figure 13-23, B, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, and 9; E, 10, 11, 13, 15, and 18), but some are small or absent (Figure 13-23, B, 4 and 6; E, 12, 14, 16, and 17).

The pulp chamber is rectangular (excluding the pulp horns). The size of the chamber varies from very large (Figure 13-23, B, 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 9; E, 13 and 16) to very small (Figure 13-23, B, 2 and 8; E, 11, 14, 17, and 18).

The curvature of the mesial canal may be severe (Figure 13-23, B, 3, 6, 8, and 9; E, 11, 14, 16, and 17), moderate (Figure 13-23, B, 2, 4, and 7; E, 10, 13, 15, and 18), or essentially straight (Figure 13-23, B, 1 and 5; E, 12). The canals gently taper from the pulp chamber to the apical constriction.

The apical foramen usually appears to be located at the tip of the root (Figure 13-23, B, 2, 4 through 7, and 8; E, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, and 18), but the foramen may appear to be located mesially (Figure 13-23, B, 3; E, 10, 13, and 16) or distally (Figure 13-23, B, 9; E, 14) on the root tip.

The distal canal may be slightly curved (Figure 13-23, B, 1 through 5, and 7; E, 11, 14, and 16) or straight (Figure 13-23, B, 4, 6, 8, and 9; E, 10, 12, 13, 17, and 18). The distal root may be slightly shorter than (Figure 13-23, B, 1, 2, 4, and 7), equal to (Figure 13-23, B, 3, 5, and 6; E, 10, 13, 14, 16, and 17), or longer than (Figure 13-23, B, 8 and 9; E, 11, 12, 15, and 18) the mesial root.

The distal canal is usually larger than the mesial canals (Figure 13-23, B, 3, 4, and 6 through 9; E, 11, 13, 15, and 16) but may be equal to the mesial canals (Figure 13-23, B, 1, 2, and 5; E, 12, 14, and 18). The distal canal tapers gently to the apex.

The apical foramen usually appears to be located at the tip of the root (Figure 13-23, B, 1 through 7; E, 10 through 13, 16, and 18), but the foramen may appear to exit mesially (Figure 13-23, B, 9) or distally (Figure 13-23, B, 8; E, 14, 15, and 17) to the apex of the root.

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-23, C, 1 through 5)

The cervical cross section of the mandibular second molar is similar to that of the mandibular first molar (Figure 13-23, C, 1 through 5). The outline form of the mandibular second molar is more triangular (rather than quadrilateral like that of the mandibular first molar) because of the smaller dimensions that are usually seen in the distal aspect of this tooth. The pulp chamber also tends to be triangular. The floor of the pulp chamber may have two openings, one mesially and one distally, which are centered within the dentin. If only one canal is present in the distal root, it will be centered within the dentin.

Midroot Cross Section (Figure 13-23, C, 6 through 9)

Midroot cross sections of the mandibular molars demonstrate that the mesial root is very broad buccolingually and narrow mesiodistally (Figure 13-23, C, 6 through 9). The outline form is kidney-shaped (Figure 13-23, C, 6 and 7) or slightly in the form of a figure eight (Figure 13-23, C, 8 and 9).

The canals may be totally separate (Figure 13-23, C, 9) or confluent (Figure 13-23, C, 6, 7 and 8), which makes it difficult to determine the presence of two mesial canals (Figure 13-23, C, 8). The distal root may be rounder than the mesial root, because the outline form of this root is usually oval (Figure 13-23, C, 6 and 9), but broad distal roots are also seen (Figure 13-23, C, 7 and 8). One canal is usually present in the distal root, but two canals are often present.

MANDIBULAR THIRD MOLAR

The mandibular third molar pulp cavities vary greatly (Figure 13-24). The pulp cavity resembles the second mandibular molar most, but the crown looks too large for the roots, which may be shorter and curved and tend to be fused together.

Figure 13-24 Mandibular third molar. A, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. This aspect does not appear on dental radiographs. B, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity. C, Five cross sections at cervical line and four cross sections at midroot. D, Buccolingual section, exposing the mesial or distal aspect of the pulp cavity. E, Mesiodistal section, exposing the buccal or lingual aspect of the pulp cavity.

Buccolingual Section (Figure 13-24, A and D)

In the buccolingual section, the pulp cavities of the mandibular third molar show a great deal of variation. Two roots and three canals are often present (Figure 13-24, B, 6 and 7), but two canals or two roots are also possible (Figure 13-24, C, 8 and 9). The presence of one canal and one root can also be found, but usually these teeth are not of much value for restorative purposes, because they have short roots that taper quickly.

Most mandibular third molars have prominent pulp horns (Figure 13-24, A, 1, 2, and 4 through 9; D, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, and 18), although others demonstrate small to nonexistent pulp horns (Figure 13-24, A, 3; D, 13 and 16).

The mesial roots of most mandibular third molars (Figure 13-24, A, 2 and 9; D, 10, 11, 13, and 14) demonstrate a square pulp chamber (excluding the pulp horns). The mesial root usually has two canals (Figure 13-24, A, 2, 5, and 9; D, 10, 11, and 14), but a single mesial root can be found (Figure 13-24, D, 14). The canals may be very curved (Figure 13-24, A, 5 and 9; D, 10) or relatively straight (Figure 13-24, A, 2; D, 11 and 13) as they taper gently toward the apical constriction.

The apical foramen usually appears to be located on the tip of the root (Figure 13-24, A, 1 and 5; D, 10, 11, and 13), but it may be located buccally (Figure 13-24, A, 9; D, 14) or lingually to the tip of the root. If two canals are present, they usually possess separate apical foramina (Figure 13-24, A, 2 and 5; D, 10, 11, and 13), but some canals join in the apical region, exiting through a common foramen (Figure 13-24, A, 9).

The distal root of mandibular third molars possesses a very large pulp chamber and canal that are difficult to delineate into separate areas (Figure 13-24, A, 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8; D, 12, and 15 through 18).

The pulp canals, which are very large (Figure 13-24, A, 1, 4, 6, and 7; D, 12, 15, and 18), may taper gently to the root tip (Figure 13-24, A, 4, 6, and 7; D, 16 and 18) or may demonstrate an abrupt constriction of the canal in the last few millimeters (Figure 13-24, A, 1; D, 12, 15, and 17).

The pulp chambers are square or rectangular (excluding the pulp horns). The pulp chambers, which are very small (Figure 13-24, A, 3 and 8), tend to show a constriction at the junction of the pulp chamber and canal, after which they taper gently to the apical constriction.

The apical foramen usually appears to be located at the tip of the root (Figure 13-24, A, 3, 6, 7, and 8; D, 16 and 17), but it may be located buccally or lingually to the root tip (Figure 13-24, A, 1 and 4; D, 15 and 18).

Mesiodistal Section (Figure 13-24, B and E)

The pulp horns of the mandibular third molar may be prominent (Figure 13-24, B, 1 and 5; E, 10, 11, 12, 14, and 15), small (Figure 13-24, A, 4, 6, and 7; D, 17), or nearly absent (Figure 13-24, B, 2, 3, 8, and 9; E, 13, 16, and 18).

The pulp chambers are usually square or rectangular (excluding pulp horns) when viewed from the buccal aspect (Figure 13-24, B, 1 through 4, 7, and 9; E, 10, 12, 13, 15, 17, and 18), but they may be somewhat square (Figure 13-24, B, 5; E, 14).

The degree of curvature of the mesial root may be slight (Figure 13-24, E, 13, single-rooted), moderate (Figure 13-24, B, 1, 2, 5, 8, and 9; E, 11, 15, and 17), or severe (Figure 13-24, B, 3, 4, 6, and 7; E, 10, 12, 14, 16, and 18).

The canal within the mesial root may be large (Figure 13-24, B, 2 and 4; E, 10) or very small (Figure 13-24, B, 1, 3, 5, 8, and 9; E, 11, 12, and 14 through 18). The canals usually taper gently to the apical constriction. The apical foramen may appear to be located at the apex of the root (Figure 13-24, B, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9; E, 11, 12, 14, 17, 18) or mesially (Figure 13-24, B, 7) or distally to the apex of the root (Figure 13-24, B, 4; E, 10 and 15).

The length of the mesial roots may be equal to (Figure 13-24, B, 2, 3, and 8; E, 10 and 11), shorter than (Figure 13-24, B, 5 and 9; E, 18), or longer than (Figure 13-24, B, 1, 4, 6, and 7; E, 12, 14, 15, and 17) the length of the distal root.

The distal canal may be larger than the mesial canal (Figure 13-24, B, 2 through 5, and 9; E, 14 and 18), but many are equal in size (Figure 13-24, B, 1, 6, 7, and 8; E, 10, 11, 12, 15, and 17). The distal canal gently tapers to the apical constriction (Figure 13-24, B, 1 through 8; E, 10 through 18).

The apical foramen may appear to be located at the apex of the root (Figure 13-24, B, 1 through 5, 7, and 9; E, 10, 11, 12, 15, 17, and 18), or it may be mesial (Figure 13-24, B, 8) or distal (Figure 13-24, B, 6; E, 14) to the apex of the root.

Some teeth show only one root with one or two canals. If only one canal is present (Figure 13-24, E, 13), the canal will be very large. If the third molar is multirooted, the canals will be much smaller (Figure 13-24, E, 16).

Cervical Cross Section (Figure 13-24, C, 1 through 5)

The cervical cross section demonstrates a variable outline form that may be rectangular (Figure 13-24, C, 1 through 4) or triangular (Figure 13-24, C, 5).

Midroot Cross Section (Figure 13-24, C, 6 through 9)

The mesial root, when present, is oval to figure eight in shape (Figure 13-24, C, 6 and 7). The distal root is oval (Figure 13-24, C, 6) or kidney-shaped (Figure 13-24, C, 7). If the roots are fused (Figure 13-24, C, 8) or only one root is present (Figure 13-24, C, 9), the canals are usually larger. The canals in the roots that are kidney-shaped or are in the form of a figure eight are more ellipsoidal.

Radiographs: Pulp Chamber and Canals

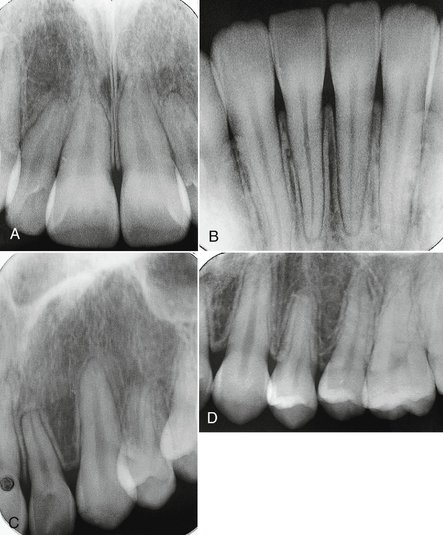

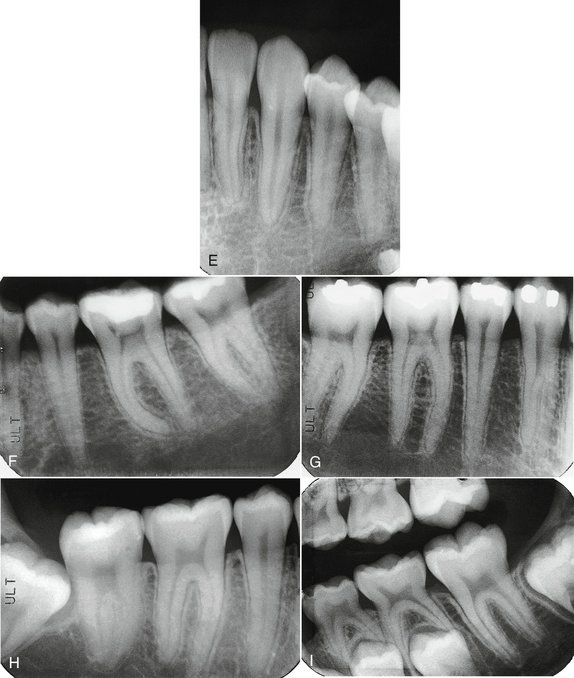

Visualization of the pulp chamber and pulp canal(s) by standard radiography or digital radiography provides the clinician with evidence to augment what has been found clinically. All teeth should be examined periodically radiographically and clinically. Knowing what might be expected anatomically about the pulp chamber and pulp canal(s), which has been considered in a previous section, helps when radiographs are taken. The radiographs in Figure 13-25, A through I illustrate normal pulp chambers and pulp canals. They are what are seen generally in the dental office, not the highly selected radiographs of the various teeth.

Figure 13-25 A, Large pulp chambers and pulp canals in a young adult. B, Mandibular incisors. Normal pulp canals. C, Lateral incisor and canine. Normal chambers and canals. Root resorption on lateral incisor. D, Maxillary canine and premolars with normal chambers and canals. Root resorption on first premolar associated with orthodontics.E, Mandibular lateral incisor, canine, and first premolar with normal chambers and canals. F, Mandibular second premolar and first and second molars with normal chambers and canals. Note curvature of the mesial root of the first molar. G, Mandibular molars and premolars with normal chambers and pulp canals. H, Impacted third molar adjacent to second mandibular molar. The pulp chambers and pulp canals are normal. I, First and second primary molars being resorbed in association with the erupting permanent premolars. Mandibular second molar in the process of erupting.

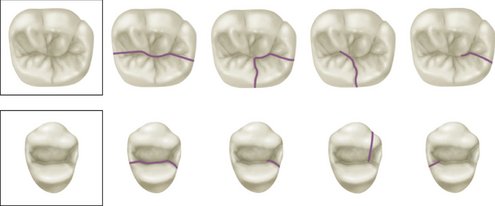

Crown and Root Fractures

Fractures of teeth may involve the crown, the crown and root, or the root. Probably the most common are fractures of the crown.3 In some cracked teeth, only the enamel is involved; in others, both the enamel and dentin may be affected; but initially or later, the pulp also may be involved with or without the loss of tooth structure (e.g., cusp). In severe trauma the whole crown may be lost. The clinician should be familiar with the most likely places, morphologically, for cracking or fractures to occur. The most likely places involve developmental grooves (Figure 13-26), often in relation to restorations.

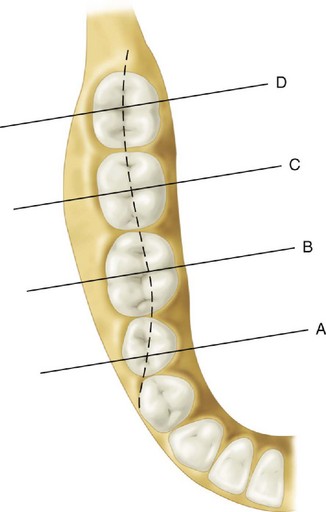

Figure 13-26 Fracture lines most commonly seen in first maxillary premolar and first mandibular molar.

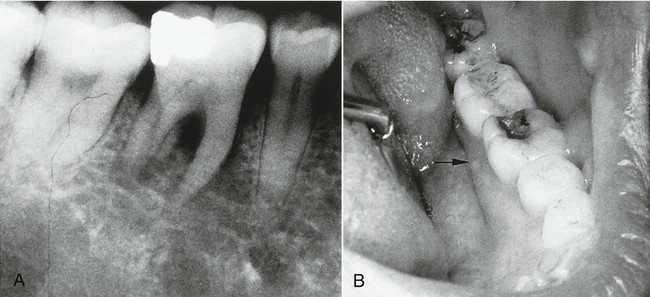

Fractures of cusps of the maxillary first premolar and mandibular first molars often occur along developmental grooves or stress lines as shown in Figure 13-26. Such fractures may occur in connection with bruxism and clenching. It is not uncommon for the distolingual cusp of the mandibular first molar to fracture in association with a large restoration, which leads to pulpitis (Figure 13-27).

Figure 13-27 A, Radiograph showing periapical radiolucency associated with parulis shown in B. B, Fracture of distolingual cusp related to undermined tooth structure and amalgam restoration.

(From Ash MM, Ramjford S: Occlusion, ed 4, Philadelphia, 1995, Saunders.)