Concepts of Basic Nutrition and Cultural Considerations

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Review the structure and function of the gastrointestinal system.

2 Utilize the components of the USDA MyPyramid website to assist patients to plan their diets.

3 Discuss the function of proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water in the human body.

4 Identify food sources of proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, and minerals.

5 List medical conditions that may occur as a result of protein, calorie, vitamin, or mineral deficiency or excess.

6 Identify a variety of factors that influence nutrition.

7 Describe cultural influences on nutritional practices.

8 Identify nutritional needs throughout the life span.

9 Discuss components of a basic nutritional assessment.

1 Identify patients at risk for nutritional deficits.

2 Complete a nutritional assessment on an assigned patient.

3 Use therapeutic communication with a patient while discussing needed diet modification.

4 Develop a teaching plan for the patient for whom a therapeutic diet is prescribed.

amino acids ( , p. 460)

, p. 460)

body mass index (BMI) (p. 475)

carbohydrates ( , p. 463)

, p. 463)

carotenoids (p. 466)

cholesterol ( ) (p. 466)

) (p. 466)

colostrum ( , p. 473)

, p. 473)

complementary proteins ( , p. 463)

, p. 463)

complete proteins (p. 461)

digestion (p. 457)

essential amino acids (p. 460)

fat (p. 465)

fiber (p. 465)

fructose ( , p. 464)

, p. 464)

glucose (p. 464)

incomplete proteins (p. 461)

kosher (p. 471)

kwashiorkor ( , p. 463)

, p. 463)

lacto-ovo-vegetarian ( , p. 463)

, p. 463)

lactose (p. 464)

lactovegetarian (p. 463)

malnutrition (p. 463)

marasmus ( , p. 463)

, p. 463)

metabolism (p. 457)

minerals (p. 467)

MyPyramid (p. 459)

nonessential amino acids (p. 460)

nutrients (p. 460)

nutrition (p. 457)

obesity (p. 473)

protein (p. 460)

saturated fats (p. 466)

sucrose (p. 464)

toxicity (p. 466)

unsaturated fats (p. 466)

vegan ( , p. 463)

, p. 463)

vegetarians ( , p. 463)

, p. 463)

vitamins ( , p. 466)

, p. 466)

Health promotion and prevention of disease are major roles of the nurse: Adequate nutrition is an essential component of attaining and maintaining good health. Nutrition is the sum of processes involved in taking in nutrients and absorbing and using them. Nutrition is concerned with those properties of food that build sound bodies and promote health. To achieve adequate nutrition, individuals should consume a balanced diet containing adequate amounts of the essential nutrients for proper body function. The functions of nutrition include providing energy, regulating body processes, and building, maintaining, and repairing tissue.

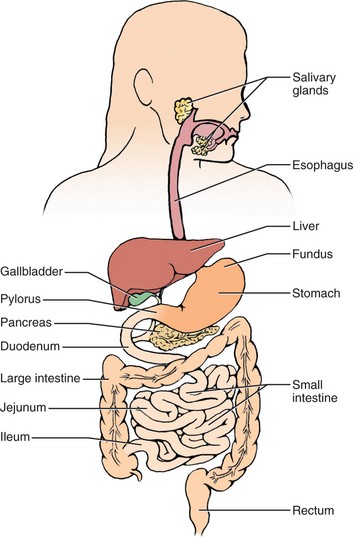

The gastrointestinal (GI) system includes the mouth (with tongue and teeth), pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. The salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas are accessory organs for the gastrointestinal system. Foods are digested and absorbed, and the nutrients in these foods are made available to all body cells through the process of metabolism (process by which large molecules are broken down into smaller molecules to make energy available to the organism). Metabolism enables the absorbed nutrients to enter the blood following digestion (process of converting food into chemical substances that can be ab sorbed into the blood and utilized by the body tissue), for the use of all body cells.

DIETARY GUIDELINES

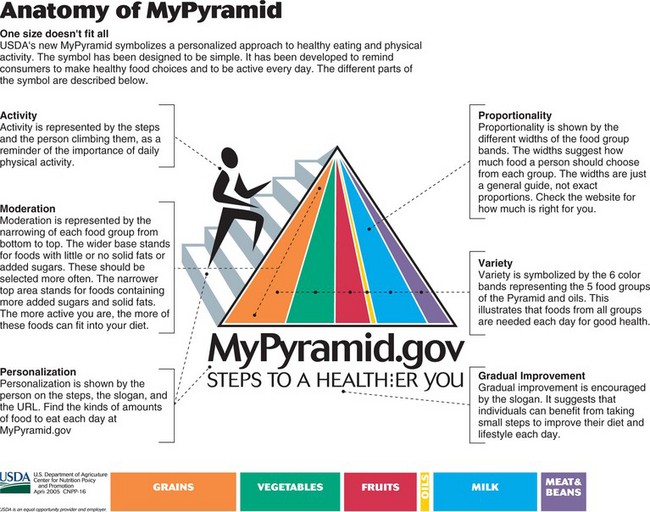

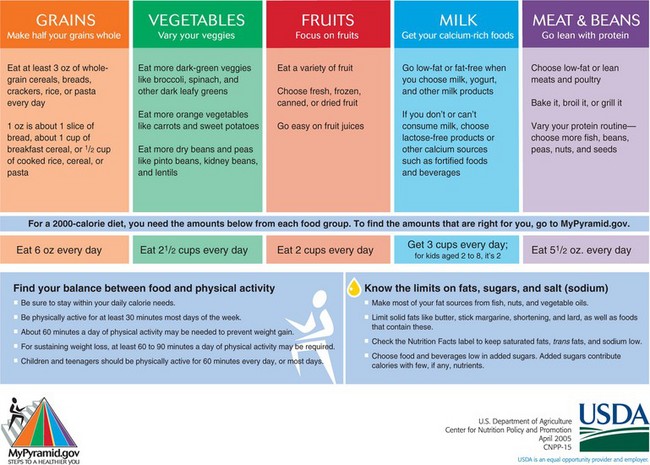

The MyPyramid food guidance system developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) (Figure 26-2) shows the six food groups necessary for good nutrition and explains the use of each component. The pyramid is developed based on the 2005 USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The guidelines describe a healthy diet as one that

• Emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products

• Includes lean meats, poultry, fish, beans, eggs, and nuts

• Is low in saturated fats, trans fats, cholesterol, sodium, and added sugars

The pyramid emphasizes a personalized approach to nutrition and is designed for individuals ages 2 and above. A variety of foods from each group is needed to achieve a healthy diet. See Figure 26-3 for the USDA’s Food Guide Recommendations for a 2000-Calorie Diet.

FIGURE 26-3 MyPyramid recommendations for 2000-calorie diet. (From U.S. Department of Agriculture, April 2006.)

The bread group consists of breads, cereals, rice, and pasta products, such as spaghetti and macaroni. The greatest number of servings per day should come from this group, and at least half should be whole-grain products. Three to five servings are recommended from the vegetable group. These servings are usually divided between lunch and dinner. The fruit group, which includes juices, is allocated two to four servings per day. Milk, yogurt, and cheese comprise the milk group, and intake should be three servings per day. The meat group includes meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, eggs, and nuts. Most Americans exceed the recommended two to three servings a day from the meat group. It is recommended that extra portions of grains and vegetables replace excess protein in the diet. This would decrease the amount of protein and fat that is now consumed in the usual adult diet. Fats, oils, and sweets are included in the MyPyramid dietary recommendations; however, they should be consumed sparingly. People of all ages are encouraged to adjust their exercise level and food intake to maintain body weight within the recommended limits. The American Heart Association released new recommendations in 2006 for diet and lifestyle. The American Heart Association 2006 Diet and Lifestyle Recommendations are presented in Box 26-1.

An alliance of federal and state agencies, the Healthy People Consortium, has contributed to the development of national health objectives. These objectives were revised in December 2005 and released by the Secretary’s Council on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention as Objectives for 2010 (Box 26-2,p. 462). Healthy People 2010 also addressed the issue of disparities in risk for nutrition-related disease among ethnic minorities and low-income groups. Issues such as obesity and food insecurity (limited access to safe, nutritious food) was evident in the low-income, Hispanic, African American, Native American, and Asian/Pacific Islander American communities, es-pecially among females. A major focus on meetingthe objectives of this area of Healthy People 2010 in-cluded improving accessibility of nutritional information, nutritional education, nutritional counseling and related services, and healthful foods in a variety ofsettings and for all population groups (Healthy People 2010, 2005).

Six nutrients (biochemical substances used by the body that must be supplied in adequate amounts from foods consumed) are essential to normal functioning: proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water.

PROTEIN

A constant supply of protein is essential to meet the body’s need to build and replace tissue and cells. During times of illness and after surgery, injuries, burns, or blood loss, we require more protein production to help in rebuilding cells and tissues. Protein plays a role in maintaining fluid balance, acid–base balance, transportation of nutrients, and antibody, enzyme, and hormone production. Protein is also a source of energy for the body. Protein supplies 4 calories per gram. The body does not store protein except in body tissues and fluids, collectively referred to as the “amino acid” pool. The body will protect its protein stores by first using carbohydrates, then fat, for energy. If these are low or absent, the body will use dietary protein, then tissue protein, for energy.

Proteins are composed of amino acids (organic compounds that are the chief components of proteins). The body can produce some amino acids to build its own proteins. Nine amino acids are considered essential amino acids because they must be consumed through food sources. The liver can manufacture 11 amino acids; these are considered nonessential amino acids. For body cells to build proteins, they must have all amino acids.

FOOD SOURCES OF PROTEIN

Food sources of protein include meats, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products, cereals, grains, legumes, and most vegetables. Animal sources (red meat, eggs, milk and milk products, poultry, fish) are complete (or high-quality) proteins because they contain all nine essential amino acids. Plant sources of protein are incomplete (or low-quality) proteins because they do not contain all essential amino acids. The only plant source of all nine essential amino acids is soybeans. Soybeans and soy products can be a less expensive substitute for meat in the diet while supplying high-quality protein. Combining plant sources of foods can provide “complementary” complete protein intake in the diet (e.g., cereal with milk, beans with rice, peanut butter sandwiches).

DIETARY REFERENCE INTAKES OF PROTEIN

Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) have been developed by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences to eventually replace Recommended Daily Allowances. DRIs provide guidelines for estimating nutrient intake for planning and evaluating diets of healthy people. DRIs are a combination of four separate recommendations: Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA, used by individuals to reduce disease risk); Adequate Intake (AI, used by individuals to set dietary goals); Estimated Average Requirement (EAR, used to plan diets for large groups); and Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL, maximum amount a person can consume without health risk). Healthy adults require 0.8 g of protein per kilogram of body weight. The average DRI is 46 to 56 g of protein per day for the healthy adult. This can be achieved through a combination of meat and plant sources. Protein intake should be approximately 10% to 15% of the total daily calories. The typical American diet is high in protein (,75 g/day). A serving of protein is, for example, a 3-oz portion of meat or a serving of beans equivalent to one-half cup of dry beans. A 3-oz serving is about the size of a deck of cards.

The DRI for protein may vary depending on ac-tivity level, state of health, and availability of protein food sources. Very active adults such as athletes and bodybuilders may raise their DRI to 1.2 to 1.4 g/kg, or up to a maximum of 1.7 to 1.8 g/kg. The body requires more protein (1) during times of illness or injury, for such processes as cell repair and antibody production; and (2) during times of rapid tissue growth, such as pregnancy and lactation. Individuals who are vegetarians or live in areas where meat sources of protein are scarce may need to consume up to 1.6 g/kg of complementary proteins to meet complete protein needs through combining foods.

To determine the protein requirement per day for a healthy adult, calculate as follows:

PROTEIN DEFICIENCY

In many nations throughout the world, the availability of protein-rich food is limited. Millions of children under age 5 are affected by lack of protein intake. Lack of protein in young children can lead to permanent disabilities because of the fast rate of brain growth that occurs during this period. Extreme protein deficiency results in the conditions of marasmus and kwashiorkor. Marasmus is a form of protein–energy and nutrient malnutrition (a disorder of nutrition related to unbalanced diet, malabsorption, or lack of assimilation of nutrients) occurring chiefly in the first year of life, characterized by growth retardation and wasting of subcutaneous fat and muscle. Marasmus is the result of severe starvation. The body uses its carbohydrate and fat sources for energy. When these are depleted, protein muscle mass is used for energy. Use of muscle mass for energy will result in heart, lung, and kidney damage if the condition continues. Uncorrected, marasmus can lead to death.

Kwashiorkor is a condition occurring in infants and young children soon after weaning from breast milk. It is due to severe protein deficiency. Kwashiorkor differs from marasmus in that adequate energy from other nutrients may be consumed; however, the diet is deficient in protein. Symptoms of kwashiorkor include edema, pigment changes in the hair and skin, impaired growth and development, distention of the abdomen, and liver changes. These symptoms occur because low protein intake leads to changes in water balance, which leads to edema. Protein is the main component of hair. Therefore, deficiency results in changes in color and texture. The liver becomes fatty and loses it ability to function. Fatty enlargement of the liver results in an enlarged abdomen.

PROTEIN EXCESS

The average American diet supplies 1½ to 2 times the DRI for protein. Athletes and very active individuals may consume higher levels. High-protein diets for people who do not require a protein increase are stressful to the liver and kidneys. The kidneys must rid the body of excess waste products resulting from an increased protein intake. This increased stress on the kidneys can contribute to kidney damage. Protein is metabolized by the liver. Liver function is strained with the excess load of protein to metabolize, which could contribute to decreased liver function. High-protein diets, especially from meat sources, can lead to excess fat in the diet. High-fat diets are associated with increased risk of obesity, heart disease, and certain types of cancer (colon, breast, pancreas, and prostate).

VEGETARIAN DIETS

Many people have become vegetarians as a means to maintain desired weight and decrease the amount of animal fat in the diet. Cultural, religious, and personal factors (e.g., objection to the killing of animals for food) also influence a person’s choice of a vegetarian diet. The primary types of vegetarian diets are as follows:

• Lacto-ovo-vegetarian: Dairy products, eggs, and plant foods are included in the diet.

• Lactovegetarian: Eggs are excluded. Dairy products and plant foods are included.

• Vegan: All animal food sources are excluded, including honey.

A vegetarian diet must be planned to include essential nutrients. Individuals choosing this dietary practice should engage in research and consult a nutrition specialist to ensure nutritional needs are met. The well-planned vegetarian diet is believed to offer health benefits such as reduced risk of heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. The challenge is to plan meals that provide adequate levels of complete proteins, vitamins, and minerals. Vegans, in particular, may have a diet deficient in vitamin B6, vitamin B12, iron, zinc, calcium, riboflavin, and vitamin D. The more limited the vegetarian diet, the greater the risk of nutritional deficiencies.

Nutrient requirements can be met by combining categories of food to meet protein needs by following a modified version of the MyPyramid. Some combinations that provide a good protein source are whole grains plus legumes, legumes plus nuts or seeds, or whole grains, legumes, nuts, or seeds plus dairy products. Soybeans are a legume high in protein and contain all nine essential amino acids. Soy products are available in many sources, including tofu, legumes, protein powders, and soy milk. Mineral deficits canbe avoided by eating dark green leafy vegetables, adding fruits with high levels of vitamin C to meals toaid in absorption of iron, or taking dietary supplements of calcium and vitamin B12 because these may be difficult to obtain in the absence of animal food sources.

Individuals who follow vegetarian diets meet their protein needs without consuming meat products. This is accomplished by combining plant sources of food to achieve a complete protein intake. These are called complementary proteins. Examples include red beans and rice, peanut butter on whole-wheat bread, bean soup with cornbread, or stir-fried vegetables with tofu.

CARBOHYDRATES

Carbohydrates are the body’s main source of energy. Carbohydrates should make up about 50% to 60% of the daily caloric intake. Each gram of carbohydrate supplies 4 calories. The three major forms of carbohy drates are simple carbohydrates, complex carbohydrates, and fiber. Complex carbohydrates should comprise about 90% of the total proportion of carbohydrates consumed. This category of carbohydrates contains fiber and other nutrients. Simple carbohydrates tend to be nutrient poor.

FUNCTIONS OF CARBOHYDRATES

Carbohydrates are a quick source of energy. They are easily converted to glucose, the fuel for the body’s cells. Carbohydrates are important to the function of internal organs, the nervous system, and muscles. Carbohydrates are also needed to regulate protein and fat metabolism. They help to fight infection and promote growth of body tissues. Many carbohydrates are also high in dietary fiber, which is essential to the bulk in stool, aiding in regular waste elimination. High fiber intake is helpful in treating certain gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., constipation, hemorrhoids) and reducing blood cholesterol levels and synthesis.

SIMPLE CARBOHYDRATES

Glucose is the metabolized form of sugar in the body. It is found in table sugar (sucrose), fruit sugar (fructose), and milk sugar (lactose). These are quickly absorbed into the bloodstream as a ready source of energy for the cells. Sucrose is the major sweetener found in foods such as candy, ice cream, cookies, and cakes. The typical American diet is high in simple carbohydrates. Although simple sugars cause a quick rise in blood sugar, the level falls rapidly and can result in a return to a hunger state.

COMPLEX CARBOHYDRATES (STARCHES)

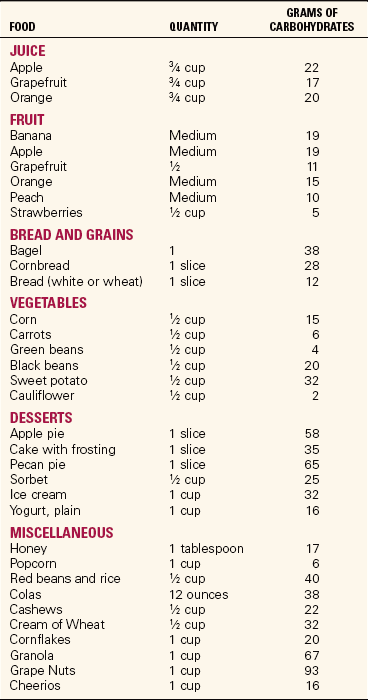

Complex carbohydrates are foods such as breads, pasta, cereal, potatoes, and rice. They are broken down into simple sugars for digestion, absorption, and use by the body. Starches provide a more consistent blood sugar level than simple sugars. Experts recommend that 85% to 95% of carbohydrates consumed should be complex, and 5% to 15% should be simple sugars. The carbohydrate content of some common foods is listed in Table 26-1.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INTAKE

Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) were developed for carbohydrates in 2002. Children and adults need a minimum of 130 g of carbohydrates per day. Approximately 50% to 60% of total calories should be carbohydrates. Diet crazes, including both the Atkins diet and the South Beach diet, stresses low carbohydrate consumption. Several research studies conducted since 2002 suggest there may be benefits to low-carbohydrate diets as a means for weight loss. Compared to other meal plans, these diets may be effective for weight loss, maintaining weight loss, and improvement of high-density lipo-protein (HDL) and triglyceride levels. Research is being conducted on the long-term effects of low-carbohydrate intake and, although the data are not in, there are questions about the nutritional effects and safety of long-term use of a low-carbohydrate diet. Some concerns include promotion of heart disease and increased risk of complications of liver and renal disease because of the high protein content of the diets. Most Americans need to increase complex carbohydrates and decrease consumption of simple sugar. It is suggested that the maximum intake of added sugars be limited to providing no more than 25% of energy.

FIBER

Dietary fiber is the portion of carbohydrates that cannot be broken down by intestinal enzymes and juices. Fiber passes through the small intestine and colon undigested. Food sources of fiber include whole-grain cereals and skins of fruits, vegetables, and legumes.

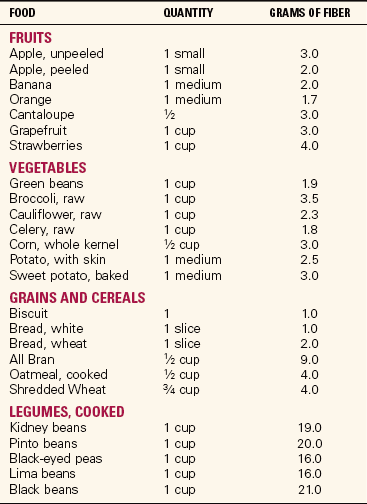

Fiber increases bulk in the stool, leading to good intestinal function and elimination. The presence of fiber in the colon also is beneficial in delaying absorption of carbohydrates and cholesterol from the intestine. This delay may be beneficial to diabetic patients by decreasing blood glucose levels. Some properties of fiber may also decrease absorption of fat. Health experts recommend 21 to 38 g of fiber per day. Fiber content in the diet can be increased by such practices as replacing white bread with whole-wheat bread and white rice with brown rice, or eating whole-grain cereals and pasta. Increasing intake of fresh fruit and vegetables, as well as beans and peas, will also increase fiber intake. Fiber content of selected foods is listed in Table 26-2.

FATS (LIPIDS)

Americans are becoming more aware of fats in their diets. Health promotion strategies emphasize the negative impact of fat on health. High fat intake has been linked to obesity, breast and colon cancer, hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases, and stroke. Triglycerides are the major lipid found in both foods and the body.

FUNCTIONS OF FAT

Fat is an essential nutrient. Fat supplies a concentrated form of energy. It also spares protein from being burned for energy. Fat supplies 9 calories/g consumed. Other functions of fat include the following:

• Provides a source of fatty acids

• Adds flavor to foods and contributes to texture

• Dissolves and transports fat-soluble vitamins and fat-soluble phytonutrients (carotenoids)

• Insulates and controls body temperature

• Cushions and protects body organs

Fats are made up of fatty acids and glycerol called triglycerides. Fatty acids are classified as either saturated fats or unsaturated fats. Fats can be of liquid or solid consistency. Fats that are liquid at room temperature are called oils. Most oils are unsaturated fat and include corn oil, safflower oil, and canola oil. Omega-3 fatty acid (found in salmon, trout, halibut, sardines, tuna, canola oil, soybean oil, omega-3–rich chicken eggs, and walnuts) is the most unsaturated form of fatty acid. These foods should be added to the diet as sources of unsaturated fat. Solid fats include shortening and lard and are saturated fats.

FOOD SOURCES OF FAT

Animal food sources provide the most saturated fatty acids, and vegetables, nuts, or seeds supply unsaturated fatty acids. Two saturated vegetable fats are coconut oil and palm oil. There are three essential fatty acids: linoleic acid (found in corn oil, safflower oil, and sunflower oil), oleic acid (found in olive oil and beef), and linolenic acid (found in green leafy vegetables, walnuts, pecans, soybean oil, and soybean products). These fatty acids are necessary for the production of healthy blood cells, healthy arteries, nerve function, and skin maintenance. Deficiencies of these three fatty acids may lead to illness or skin problems.

Most Americans consume more fat in the diet than is needed to maintain health. The recommended daily allowance of fat is 25% to 30% of total calories. Saturated fats should be limited to 10% of total fat intake, or 2.5% to 3% of total calories. Some cardiologists recommend diets of 20% fat for individuals at risk for heart disease and as low as 10% fat for individuals with a history of heart disease. Research has shown a marked reduction of risk for further complications of heart disease and in some instances reversal of cardiac pathology.

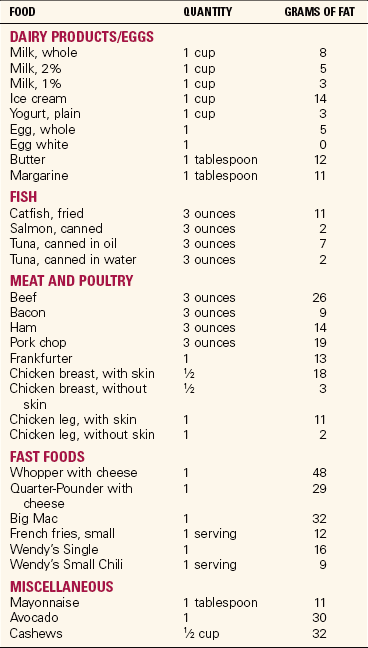

A component of fat, cholesterol, is linked to heart disease and hardening of the arteries. Cholesterol is only found in animal products and oils such as palm and coconut. Increased cholesterol level places the individual at risk for heart disease and stroke. Cholesterol, however, has an important role in the structure of essential hormones and in the conversion of vitamin D by the action of sunlight on the skin. Cholesterol is also essential to the production of bile in the liver. Table 26-3 lists fat content of selected foods.

VITAMINS

Vitamins are present in small amounts in a wide variety of food sources. They are essential nutrients that must be taken in through food sources or supplements. It is best to consume vitamins through food sources; however, vitamin supplements can provide the nutrients needed. Vitamins are classified as fat soluble or water soluble. Water-soluble vitamins are easily absorbed into the bloodstream for use by the body. Fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed in the small intestine the same as other fats by action of bile in the duodenum, and are stored in the liver.

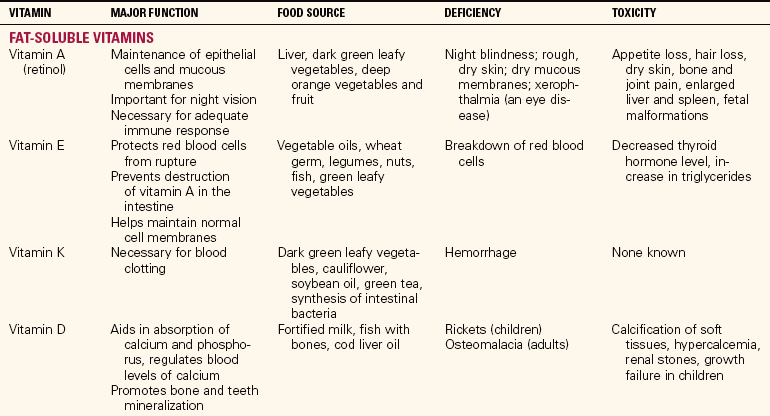

The fat-soluble vitamins are vitamins A, D, E, and K. These vitamins, because they are stored in the body, can cause toxicity (poisoning) if ingested in excessive quantities. Vitamin A can be produced in the body by carotenoids (e.g., beta-carotene) Carotenoids act as antioxidants, protecting the cells and tissues from damage from free radicals, and have been shown to increase immunity, improve vision, and have a role in cancer prevention.

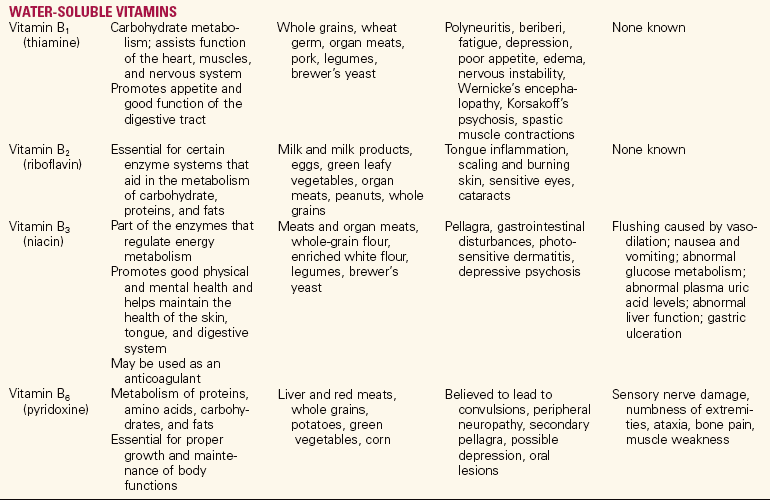

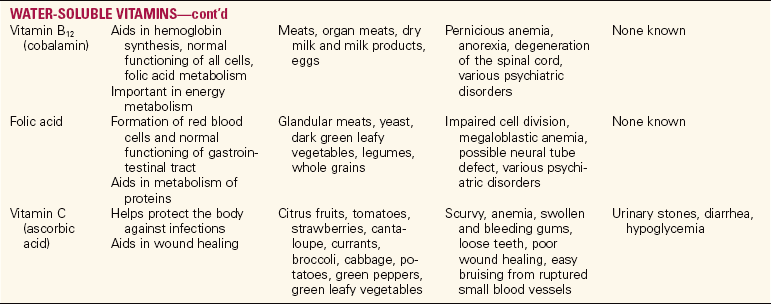

The water-soluble vitamins include the B-complex vitamins (thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folic acid, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, and biotin) and vitamin C. Some of these vitamins (especially niacin, vitamin B6, and folate) accumulate in toxic amounts only if a person is taking large quantities of them as supplements or is suffering from kidney failure. Although vitamins do not have caloric value, they are essential to the body for the building of tissue and for proper cellular function and to facilitate the reactions that release energy from carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Table 26-4 summarizes the function, common food sources, signs of deficiency, and signs of toxicity of fat-soluble and water-soluble vitamins.

MINERALS

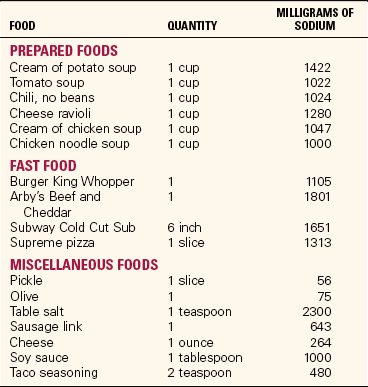

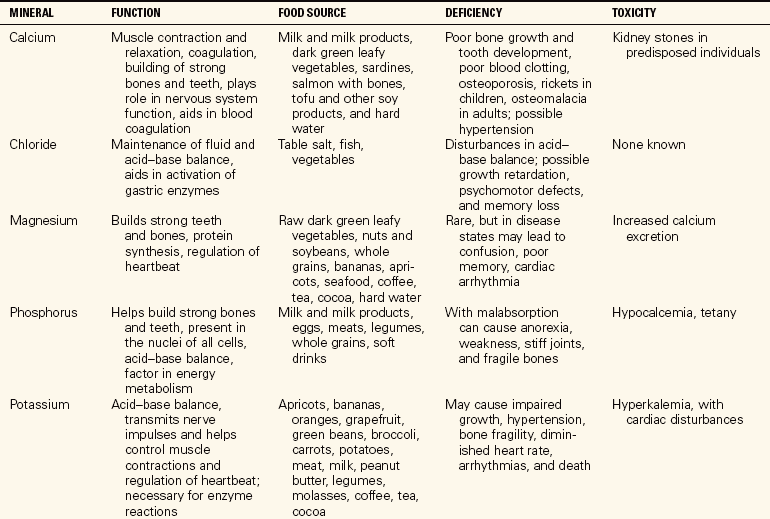

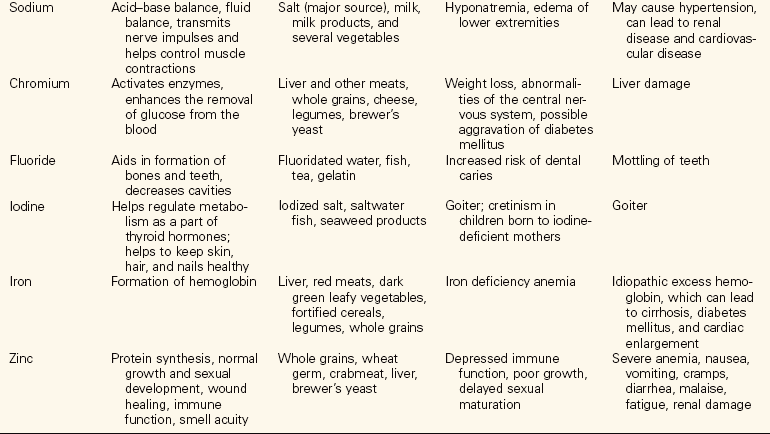

Minerals are inorganic substances contained in animals and plants. They are essential for metabolism and cellular function. Minerals are categorized as major minerals (macro minerals) or trace minerals (micro minerals). The major minerals are calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, phosphorus, sulfur, and chlorine. Selected foods with high sodium content are listed in Table 26-5. Trace minerals are iron, copper, iodine, manganese, cobalt, zinc, molybdenum, selenium, fluoride, and chromium. Minerals are necessary for proper muscle and nerve function and act as catalysts for many cellular functions. They combine to form salts and are largely responsible for the acid–base balance of the body. Because mineral actions are interrelated, a deficiency of one mineral will affect the action of another mineral in the body. Other functions of minerals include the following:

• Maintaining rigidity and strength in teeth and bones

Dietary Reference Intakes have been created for every mineral. Generally, sufficient minerals can be supplied by a balanced diet. Extra iron is needed when blood loss from surgery or trauma has occurred. The body does not manufacture its own minerals; therefore, all must be provided through food sources. Table 26-6 lists minerals, their function, food sources, signs of deficiency, and signs of toxicity.

WATER

Water is the most essential of all nutrients. The adult body is 50% to 60% water by weight. The proportion of water is dependent upon body composition, age, bone density, body weight, and hormone status. As the body ages, the percentage of body water decreases. The water requirement for adults is approximately 1 mL/calorie of intake (or 35 mL/kg in adults, 30 mL/kg in the elderly). Water requirements are increased for patients who are immobile, have a fever, or have diarrhea.

Water is used in every body process from digestion to absorption to elimination or secretion. Most foods contain water, and the body obtains a substantial amount of the water needed directly from food. Water is not stored in the body, and what is lost during 24 hours must be replaced. A general rule is that the patient should take in an amount equal to the recorded fluid output plus 500 mL.

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE NUTRITION

To assist patients to reach their optimum nutritional state, you must consider a variety of factors that may influence an individual’s ability to meet nutritional needs. A dietitian should be consulted if malnutrition or risk of malnutrition is suspected.

AGE

Infants are dependent upon others to meet their nutritional needs. Nutrition may be provided by breast milk or formula. As the child grows, nutritional needs change based on the stage of development. Parents and caregivers face the challenge of experimenting with a variety of foods and meal strategies to meet the needs of growing children.

Adolescents are strongly influenced by their peers. Food choices are often of the fast-food and pizza variety. Growth spurts during this time may result in voracious appetites, leading to concerns about weight management. Eating disorders are a concern during this growth period, especially among adolescent girls, but the prevalence in adolescent boys is increasing.

Physiologic changes and physical limitations may influence the eating habits of the elderly. The elderly may be at risk for inadequate nutrition because of income limits, loneliness, and difficulty obtaining and/or preparing food. Nutritional deficiencies can often mimic the dementia of aging, and elderly patients showing signs of dementia should be evaluated for deficiencies.

ILLNESS

Nutritional needs usually increase during illness. Patients with diseases such as cancer and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) experience loss of muscle mass, resulting in the need for more calories and protein. A loss of appetite may occur due to pain, nausea, vomiting, and stomatitis. These patients are a special challenge to health care workers.

EMOTIONAL STATUS

An individual’s emotional state has a strong influence on eating habits. Some persons tend to overeat during times of emotional distress, whereas others will lose their appetite. You should be aware of the patient’s response to stress and take opportunities to intervene if nutrition is compromised.

ECONOMIC STATUS

Sufficient income does not guarantee optimum nutrition. However, it does provide the opportunity to make healthy choices. Individuals with limited income can benefit from patient education related to good nutritional choices because a balanced diet is affordable even with low income. In addition, patients should be referred to community and government programs (e.g., Women, Infants, and Children [WIC]; Supplemental Food Program) for assistance in meeting nutritional needs. Social workers and dietitians can be helpful in recommending community resources providing nutritional interventions and programs.

RELIGION

Religious practices and affiliations influence nutrition by dictating food preparation, foods allowed, and those to avoid. You must develop an awareness of and respect for patients’ religious beliefs related to food to promote good nutrition effectively. Some common religious food practices include the following:

• Islam: No pork or pork products. No alcohol.

• Judaism: Foods prepared in kosher manner (prepared for use according to Jewish law). Separate dishes, pans, and silverware must be used to prepare and serve meat and dairy food. Meat and milk may not be eaten at the same meal. Pork, shellfish, crustaceans, and birds of prey are not allowed. Orthodox Jews follow stricter guidelines than others.

• Seventh-Day Adventist: No stimulants (coffee, tea). Shellfish, pork, and alcohol must be avoided. Many are lacto-ovo-vegetarians with emphasis on whole-grain foods.

CULTURE

Cultural influences, both ethnic and environmental, have an important impact on nutrition. Individuals are more likely to consume foods with which they are familiar. Most traditional ethnic diets can be modified to meet required nutritional needs. Many rely on combining incomplete proteins (rice and beans, etc.) to make complete proteins.

CULTURAL INFLUENCES ON NUTRITION

American society is composed of multiple cultures. Ethnicity, culture, and region of residence have a strong influence on nutrition. Awareness of nutritional preferences of different ethnic groups can enhance your ability to provide effective nutritional counseling.

AFRICAN AMERICAN

The African American diet closely resembles food preferences of the southern region of the United States. African and West Indian influences are also prevalent in the African American diet, as evidenced by inclusion of foods such as okra, black-eyed peas, and peanuts and peanut products in the diet.

Typical foods in the traditional African American diet include a variety of greens (collard, mustard, turnip, kale), dry beans, cornbread, sweet potatoes, pork, catfish, and chicken. Most meats and fish are prepared by frying. Seasonings for vegetables include smoked bacon, ham, and salted pork. Desserts may include sweet potato pie, peach cobbler, and fried pies. These preferences often contributed to high fat, sugar, and salt content in the traditional African American diet. Dietary counseling should include modification of the diet to accomplish a more healthy composition while maintaining the basic components of the diet.

HISPANIC AMERICAN

The Hispanic population is one of the fastest growing in the United States. Several groups are represented, including Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban. Nutrition preferences have a Spanish and American Indian influence. The Hispanic diet is high in carbohydrates such as beans, rice, corn, and tortillas. Meats and meat dishes are heavily seasoned and spicy. The diet can be high in fat because of the use of lard in the preparation of fried foods. Desserts are very sweet and may be prepared with syrup-like sauces. Preferences for fried foods lead to high fat in the diet.

ASIAN AMERICAN

The popularity of Asian American cuisine is evident throughout the United States. The traditional Asian diet is high in carbohydrates and vegetables, and low in meat and fish. Mung beans and soybeans and products such as sprouts are also used. Vegetables are rarely eaten raw. They are stir-fried and added to meat, rice, or noodle dishes. The practice of adding monosodium glutamate (MSG) to enhance flavor has decreased. However, dishes may still have a high sodium and high fat content.

MIDDLE EASTERN AMERICAN

Food preferences among Middle Eastern cultures include fermented dairy products such as yogurt, meats, grains in the form or wheat or rice at each meal, fresh fruits, and vegetables. Some foods are specially prepared if the individual practices the Muslim religion. Food preparation includes grilling, frying, grinding, and stewing.

The nurse and dietitian can assist patients to modify diets to meet nutritional requirements. Meals can be made healthier by teaching patients to prepare food with less fat and sodium. Use of herbal, low-sodium seasoning can maintain the desired flavor. A summary of food patterns of American cultural groups can be found in Table 26-7.

Table 26-7

Culturally Diverse Food Patterns of Americans

| CULTURE | HISTORICAL DIETARY PATTERN* |

| African American | All meats, fish, and chicken; pork often consumed (spareribs, bacon, and sausage); vegetables cooked in salt pork for long periods of time; grits and cornbread muffins; some lactose intolerance. Popular vegetables include collard greens, beet greens, and sweet potatoes. |

| Chinese American | Rich in vegetables (bean sprouts, broccoli, bamboo shoots, and mushrooms). Vegetables cooked until crisp; meat consumed in small portions with other food. Soy sauce, tofu, peanut butter; limited milk and cheese; fish baked with native spices; soups with egg, meat, and vegetables. Tea is China’s national beverage. Rice is staple of diet. |

| Jewish American | Diet varies according to whether family is Orthodox, Reform, or Conservative. For Orthodox family, food must be kosher (clean); meat is soaked in salt water to remove blood; only meat eaten is that of divided hoofed animals that chew a cud; fish without scales (shellfish) and pork are prohibited; milk and meat cannot be combined. Favorites are gefilte fish, lox (smoked salmon), herring, eggs, bagels, cream cheese, and matzo. |

| Laotian American | Numerous varieties of freshwater fish and shellfish (eaten fresh, dried, or salted); pork, beef, chicken, rabbit, often mixed with vegetables and spices; eggs, peanuts, black-eyed peas; vegetables eaten raw, as juice, or cooked with meat or fish and preserved by drying or pickling; sticky rice, rice or bean thread noodles, and legumes often used in desserts; soybean drink, sugar cane drink, tea, and coconut juice. Popular seasonings include padek, chilies, curry, tamarind, and red and black pepper. |

| Italian American | All meats, fish, and chicken, including cold cuts (salami, mortadella) and Italian pork sausage; pasta (staple of diet), breads, olive oil, wine, cheese, and all varieties of fruits and vegetables. |

| Japanese American | Fish and seafood (fresh, smoked, and raw) and beef. Food is cut into small portions. Principal fruit is nasi, which tastes much like a pear. Many vegetables are eaten, such as seaweed, bamboo shoots, onions, beans, and dried mushrooms (shitake); enjoy pickled vegetables. Rice is national staple. Beverages include tea and sake. Little cheese, milk, butter, or cream is consumed. Chief cooking fat is soybean oil or rice oil. |

| Mexican American | Chicken, pork chops, wieners, cold cuts, hamburger, eggs (used frequently), beans (eaten mashed or refried with lard), potatoes (basic item, usually fried), chilies, fresh tomatoes, corn (maize—often used as basic grain), tortillas, packaged cereals; little milk because of lactose intolerance. |

| American Indian | Acorn flour, a staple food made into mush or bread; salmon, fresh or dried; other varieties of fish, deer, duck, geese, and other small game; nuts such as buckeye and hazel; wild berries, seeds, and roots. |

| Puerto Rican American | Meat cooked in stews; poultry, pork, fish, dried beans or peas mixed with rice; milk in combination with coffee (cafe con leche), variety of fruits, starchy vegetables (plantains, cassava, sweet potatoes), salad, soft drinks. |

| Vietnamese American | Pork—most common meat; meats cut into small pieces and fried, boiled, or steamed; fish—all types of freshwater and saltwater fish and shellfish, often fried and dipped in fish sauce; eggs, soybeans, legumes, and wide variety of fruits and vegetables; rice often eaten with every meal; seasonings including oyster sauce, soy sauce, monosodium glutamate, ginger, garlic, nuoc mam sauce; tea, coffee, soft drinks, soybean milk. |

| Middle Eastern American | Lamb is the most commonly eaten meat. Pork is prohibited if the individual is of the Muslim or Jewish faith. Legumes such as black beans, chick peas, and lentils may be used for food preparation. Feta cheese is a favorite dairy product. Breads and cereals may include unleavened bread, and pita bread is commonly eaten. Eggplant is very common in the Middle Eastern diet. Fruits and vegetables are preferred raw. Preferred spices and herbs include dill, garlic, mint, cinnamon, oregano, parsley, pepper, and olive oil. |

*More diverse eating patterns occur as future generations of a culture become assimilated.

Adapted from Leifer, G. (2003). Introduction to Maternity & Pediatric Nursing (5th ed., p. 36). Philadelphia: Saunders; and data from Mahan, L.K., & Escott-Stump, S. (2008). Krause’s Food, Nutrition and Diet Therapy (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; and other sources.

NUTRITIONAL NEEDS THROUGHOUT THE LIFE SPAN

The first year of life marks the fastest growth period of human development. By 6 months of age, the birth weight of the normal newborn should double. By the end of the first year, the birth weight should triple. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that infants be breast-fed or receive breast milk for the first full year of life. Emphasis on the importance of breast-feeding is a major component of prenatal education programs. In addition to providing complete nutrition, breast milk also provides immunity to most childhood diseases through the first few months of life. The first breast fluid, colostrum, is available at delivery. Colostrum also contributes to passage of meconium stool and growth of normal bacterial flora in the bowel. Within 7 to 10 days of delivery, the composition of breast milk changes. Protein and fat-soluble vitamin content decreases, and water-soluble vitamins, fat, and calories increase. By the 14th day, mature milk is produced. Breast milk rarely causes allergic responses in the infant.

Infant formulas are similar in composition to breast milk; however, nutrients in human milk are more easily digested and absorbed. Formulas are a modified form of cow’s milk, made more digestible and with added carbohydrate and fat content. Infants with allergy to modified cow’s milk may use soy-based formulas (unless soy allergy is a concern) or special hypoallergenic formulas. An advantage of bottle feeding is the opportunity to share the feeding responsibility with other caregivers. Feeding can be a time to build an emotional bond with the infant. Fathers, grandparents, and older siblings can also establish this bond. Breast-feeding mothers can pump their breasts so that the infant can be bottle-fed by other caregivers.

A milestone for infants is the introduction of solid foods. Pediatricians prefer adding solid foods to the diet at 4 to 6 months of age; however, some health care professionals encourage later introduction of solid foods (starting at 9 to 12 months) to further decrease the risk of food allergy or sensitivity. Many parents add solid foods earlier in the belief that solid foods will satisfy the infant and result in the infant sleeping through the night. This practice should be discouraged because the infant’s GI system is still immature and is unable to digest cereals before 3 months of age. Introducing solid foods before 4 to 6 months of age also increases the risk of the infant developing food allergies as the immune system matures.

Solid foods should be introduced gradually, one item at a time. This provides the opportunity to identify allergic responses. A cereal such as rice is a good initial choice. Rice is easily tolerated and provides additional iron and calories. Another new food can be introduced in about 1 week. Each new food should be a single item. Introduction of combination foods decreases the ability to identify foods that may be responsible for an allergic response should one occur. As the child shows evidence of tolerating solid foods, weaning from the bottle or breast should be considered. Parents and caregivers should allow children to develop their own food preferences and to decide when and how much to eat.

TODDLERS AND PRESCHOOL CHILDREN

During the toddler and preschool years (ages 2 to 5), the growth rate tends to level off. The child consumes less milk and increases intake of solid foods. Toddlers’ food choices may change frequently. They seem to have a hearty appetite at times, then show lack of appetite at other times. Specific food preferences may be evidenced (e.g., mashed potatoes and gravy); then the child suddenly refuses these items. Parents and caregivers become very frustrated with these reactions and are often concerned that the child is not obtaining adequate nutrition. Parents can use some of the following guidelines to assist toddlers to eat:

• Provide a pleasant environment at mealtimes.

• Avoid combination foods. Toddlers prefer single-item foods that do not touch each other on the plate.

• Provide plates and utensils in a size that can be easily handled by the small child.

• Use dishes that are colorful and/or contain pictures of favorite characters.

• Avoid forcing a child to eat.

SCHOOL-AGE CHILDREN

School-age children may be influenced by their peer group when making food choices. They are very susceptible to commercial ads for fast food that show toys as prizes and show children in play areas when eating. Children at this age may desire sweet, non-nutritive foods such as soda, candy, cake, and ice cream. Parents and caregivers should serve as role models by eating nutritious meals and snacks and providing healthy meals and snacks for school time. Children should be served a well-balanced breakfast before leaving for school. Studies have shown that a healthy breakfast increases a child’s ability to concentrate and achieve in school. Lunches could be taken from home or selected from the school cafeteria menu. Children should be taught to make wise choices from the school menu. Children from lower income families may be able to take advantage of government-sponsored school breakfast and lunch programs.

An increasing number of children come home after school to an environment without adult supervision. Parents can provide nutritious after-school snacks such as fruit and raw vegetables. Snacks high in sodium and sugar should be minimized or avoided. Because of the high calorie and high sodium preferences of many young children, obesity (excessive accumulation of body fat) can be a health issue during the school-age years.

ADOLESCENTS

Many physiologic changes occur during the adolescent years. Of these changes, the growth spurt and social and emotional changes related to puberty have great impact on nutrition and eating habits. Adolescents tend to consume many fast foods, either from fast-food restaurants or vending machines. Fast-food restaurants also serve as a social gathering place for many adolescents.

During the growth spurt (girls ages 10.5 to 14, and boys ages 12.5 to 14), the body requires more calories as well as nutrients such as B vitamins, calcium, vitamin D, and iron. Adolescent females require increased levels of iron after the menstrual cycle begins. Adolescent girls are very aware of their appearance. Concern about weight may lead to eating disorders, resulting in inadequate calories and nutrients for growth. Parental supervision and intervention may be critical to assisting the adolescent to meet appropriate nutritional needs. Parents can assist by

• Providing snacks high in calcium, iron, and protein

• Decreasing preparation of high-fat foods

• Teaching how to select more healthful choices from fast-food restaurants and preparing healthier versions at home with friends

• Keeping fruit juice and low-fat milk available instead of high-calorie sodas

• Keeping vegetable sticks and fresh fruit available as snack choices

ADULTS

Child-rearing, work, and family responsibilities have an influence on the eating habits of most adults. Many adults rely on fast food or convenience foods to meet their nutritional needs. Studies have shown that adults eat many of their meals, especially breakfast and lunch, from fast-food restaurants. Oftentimes the only meal consumed at home is the evening meal, and even that may not be prepared at home. Medical problems such as obesity and hypertension are prevalent during early and middle adulthood. This can be attributed to stress, poor eating habits, and lack of exercise. Lifestyle and dietary recommendations for adults include

• Decrease fat and sodium intake.

• Decrease intake of simple sugars.

• Increase fruit, fresh vegetables, and whole grains in the diet.

• Prepare more meals at home, where fat and sodium content can be controlled.

Patient teaching about good nutrition and making healthy choices is very important. Many want to change habits, but may not have the needed information (Communication Cues 26-1).

OLDER ADULTS

Older adults are the group most at risk for inadequate nutrition. Many factors influence eating habits of older adults. Economic status, physical disabilities, chronic disease, access to food sources, and physiologic changes must be considered when planning nutrition for this group. Nutrient requirements do not change with aging except in the presence of disease and/or illness. Older adults may need to decrease calories if activity level is decreased; however, increasing physical activity by including strength training and flexibility activities should be encouraged to promote appetite and a sense of well-being. Physiologic changes such as a decrease in taste and smell may decrease the appetite of many older adults. The taste of sweets remains strongest and may contribute to elderly people consuming more sweets than is advisable. Physical limitations such as chronic lung disease and arthritis make food preparation more difficult and may result in reliance on convenience foods that may not be nutritious. Many older adults have lost spouses and friends through death. Eating alone is not pleasant for many individuals. If possible, arrange for companionship during meals, such as sitters or attendance at senior day services centers. At least two meals a day are served at most centers. Some older adults have limited incomes and must limit food choices. Programs such as Meals on Wheels, the Food Stamp Program, and community food banks, as well as family intervention, can help older adults to meet nutritional needs. Social workers and dietitians can assist in making these referrals. Families can prepare meals that can be frozen and easily heated by the elderly person. Patient Teaching 26-1 gives strategies to assist older patients to meet nutritional needs.

Another concern for older adults living alone is senility. Many elders with memory loss may not remember eating and may not eat for long periods of time. Family intervention to provide supervision of meal preparation and eating can help to ensure the person is eating nutritionally and preparing foods safely.

APPLICATION of the NURSING PROCESS

The nurse should be aware of factors that may havea negative impact on the patient’s nutritional sta-tus. The admission physical assessment is a good time to observe the patient for potential nutritional problems. Admission diagnoses such as cancer, kidney disease, liver disease, gastrointestinal disease, HIV/AIDS, obesity, diabetes mellitus, or hypertension indicate a need to address nutritional issues. Surgical procedures such as gastrectomy or colonresection also indicate the need to address nutrition. Dietitians should be consulted for any of these diagnoses.

The nutritional assessment begins with a complete medical, family, and social history. Information can be obtained from the family if the patient is unable to respond. The patient’s income level, education, activity, and family status should be considered.

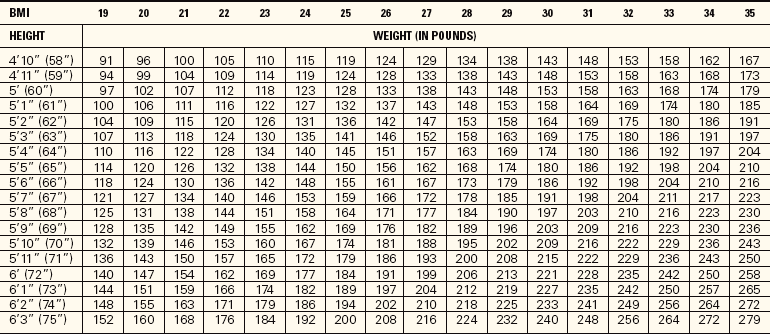

Physical examination should begin with observation of the patient’s general appearance. Is the patient obese? Is there muscle wasting? Notation should be made of the patient’s skin, hair, nails, eyes, mouth, and extremities. Neurologic function should be assessed as well. Height and weight should be measured. Weight gain or loss should be noted. Determination of the patient’s thinness or excessive fatness should also be determined. A common technique used is to determine the patient’s body mass index (BMI). The BMI uses height and weight to estimate fat values at which the risk for disease increases. The BMI may provide more useful information than body weight alone because ideal body weight formulas do not take into consideration individuals with large muscle mass. A simple way to determine the BMI is to multiply the weight in pounds by 705, then divide this figure by the square of the height in inches. For example, for a person who weighs 165 lb and is 5–8” tall:

A BMI chart with most calculations completed may also be used (Table 26-8). The chart is not all-inclusive. Use of a more extensive chart or calculations are required for those patients whose weight is outside the limits of the chart.

Table 26-8

From National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2007). Obesity Education Initiative. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Available at: www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi.

The recommended range for BMI is 18.5 to 24.9. A BMI below 18.5 is considered underweight, between 25 and 29.9 overweight, above 30 obese, and above 40 morbidly obese and at severe risk for disease. Waist circumference may also be a determining factor for risk of disease. A waist size greater than 35 inches for women and 40 inches for men is associated with increased risk for disease. The BMI serves as a screen only. Results should be evaluated with other assessment information to determine the patient’s risk for disease.

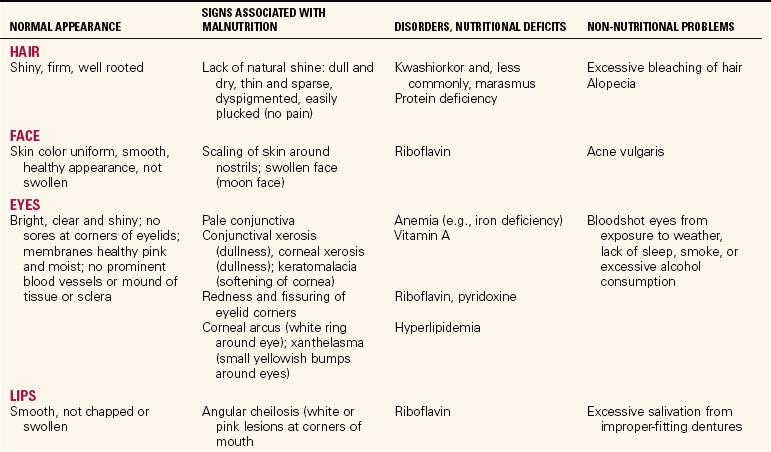

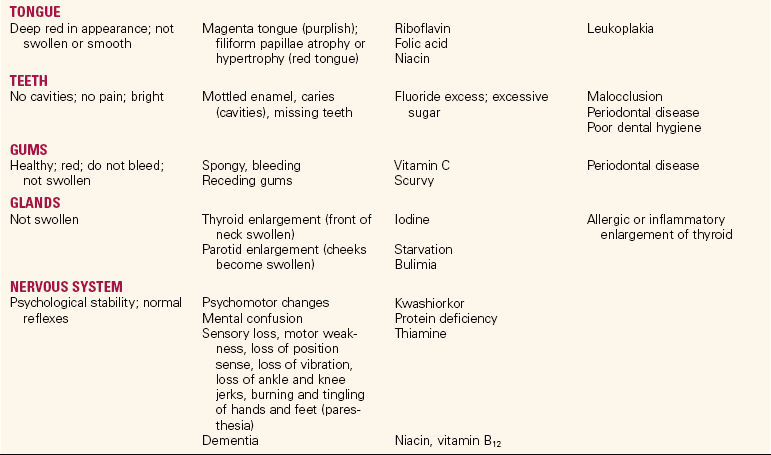

You must also review results of laboratory studies as part of the nutritional assessment. Serum albumin (protein), hemoglobin, and hematocrit will indicate if the patient is at risk for malnutrition, anemic, or dehydrated. Table 26-9 summarizes physical signs of malnutrition. Further assessment of the patient’s nutritional status can be completed by asking the questions in Focused Assessment 26-1.

Table 26-9

Physical Signs Indicating Possible Malnutrition

Adapted from Mahan, C.K., & Arlin, M. (2008). Krause’s Food, Nutrition and Diet Therapy (10th ed., p. 375). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; and Peck-enpaugh, N.J. (2007). Nutrition: Essentials and Diet Therapy (12th ed., pp. 469–470). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders.

After completion of the nutritional assessment, determine if a nutritional problem is present. Document the findings and conclusions. Documentation should include a summary of the findings and indicate any problem identified and the course of action taken. Make a nutritional referral to the dietitian, with the physician’s permission, if malnutrition or other nutritional problems are identified so that early intervention can be started.

Nursing Diagnosis

After data collection, nursing diagnoses and goals/expected outcomes should be formulated. Some nursing diagnoses related to nutrition include the following:

Planning

Some examples of goals and expected outcomes for the above nursing diagnoses are as follows:

• Patient will consume 2200 calories per day.

• Patient will restrict caloric intake to 1800 calories per day.

• Patient will verbalize methods to manage stress, such as relaxation exercises.

• Patient will consume 1500 mL of fluid per day.

• Patient with edema in upper and lower extremities will experience its decrease by day of discharge.

• Infant will gain 5 oz by day of discharge.

• Patient will choose appropriate foods from the hospital menu for a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet.

• Patient will consume at least 50% of a pureed diet.

• Patient will have breath sounds that remain clear with no evidence of aspiration on repeat swallow studies.

Implementation

Interventions for nutritional care include assisting patients with the meal tray, feeding when necessary, providing enteral nutrition or total parenteral nutrition when needed, teaching about proper diet, encouraging adherence to a therapeutic diet, and monitoring the patient’s nutritional status.

Before serving a meal, provide for elimination by offering the bedpan or urinal or assisting the patient to the bathroom. Assist the patient to wash the hands and face as needed. Provide oral hygiene if desired. Create an attractive and pleasant environment for eating. Remove distracting articles, such as an emesis basin or a urinal, and use a spray or deodorizer to remove unpleasant odors in the room if not contraindicated. Position the patient comfortably for the meal, with the head of the bed elevated (if allowed), or assist the patient to sit up in a chair and clear the over-the-bed table for the diet tray.

When serving prepared trays from the dietary kitchen, serve those patients first who are able to feed themselves. Each tray should be checked against the unit dietary order list to verify that the correct diet tray has been prepared for each patient. Deliver the trays as quickly as possible to prevent food from cooling.

When dietary personnel deliver meal trays, the nurse is responsible for positioning the patient and setting up the tray to promote food and fluid intake (Assignment Considerations 26-1). Many people have difficulty opening the sealed packages of eating utensils and condiments. For the patient with an intravenous cannula in the hand, milk cartons and other sealed food items should be opened and prepared for eating. Attending to these details quickly after the trays are served helps the patient enjoy a warm meal.

Patient and Family Teaching: Depending on the patient’s nutritional problem and type of diet prescribed, the following points may be included in the patient’s teaching plan:

• Normal weight for body height and build

• Caloric intake needed to maintain normal weight

• Need for added calories, proteins, and vitamins to promote healing

• Foods high in iron and vitamin C that are used to build iron stores

• Use of “low-salt” or “no-salt” canned vegetables

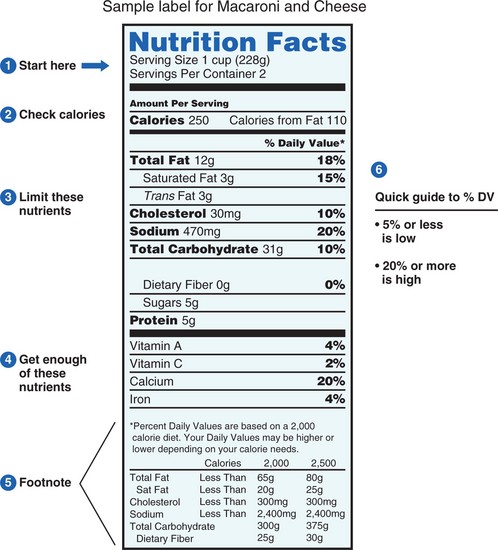

• How to read food labels to determine the content and caloric value of various foods

• Use of a variety of herbs and spices to enhance the taste of food when salt is restricted

• Use of frequent small meals, which may be more appealing when appetite is diminished

• Ways to increase the amount of vegetables and fruit in the diet

• Methods of shopping wisely for prepared frozen foods when there is limited time available for food preparation

• Resources such as community food banks, Food Stamp Program, and WIC for patients with limited financial resources

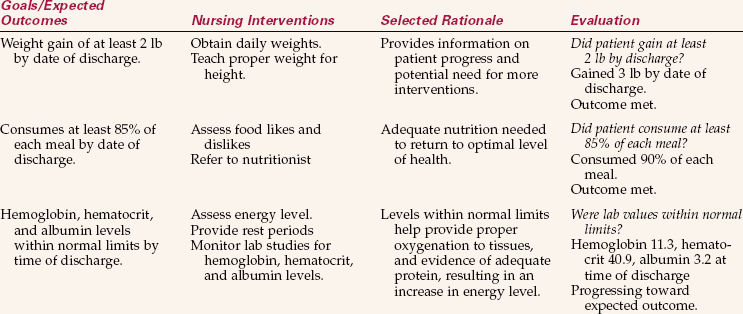

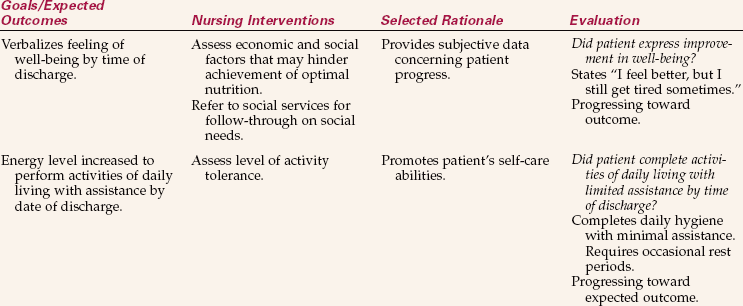

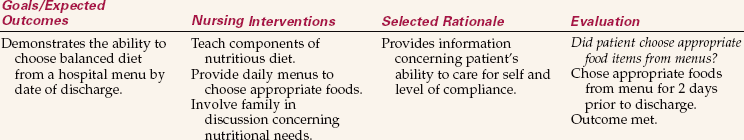

Evaluation

Evaluation is based on the achievement of the expected outcomes. Review the goals/expected outcomes. Did the patients achieve them? Did they partially achieve them? If problems were not resolved, why not? While evaluating a patient’s achievement of outcomes, you may need to work with the patient to change, modify, or eliminate some expectations (Nursing Care Plan 26-1).

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. When teaching a patient about essential nutrients, which of the following will the nurse explain provides energy to the body? (Select all that apply.)

2. The major nutrient(s) involved in fluid balance are: (Select all that apply.)

3. The patient’s potassium level is reported as 2.5 mEq/L. The nurse recognizes this as a critically low value. The patient is at high risk for __________________________. (Fill in the blank.)

4. Carbohydrate digestion begins when:

2. pancreatic enzymes are present in the small intestine.

5. The major component necessary for metabolism of carbohydrate is:

6. A woman’s BMI is measured as 26. This BMI level is classified as:

7. A patient who weighs 185 lb is placed on a 2200-calorie diet. How many grams of protein should the diet contain to meet the maximum recommended daily requirement of this nutrient?

8. The dietitian recommends an increase of fiber in the diet. Which of the following foods is a good source of fiber?

9. The nurse teaches the patient that which of the following has the least saturated fat in the diet?

10. During a physical examination of a patient, which of the following is NOT indicative of malnutrition?

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES ? Read each clinical scenario and discuss the questions with your classmates.

Ray Brown, age 28, is 6–1” and weighs 250 lb. He states he has had difficulty remaining on the 2500-calorie diet prescribed by the dietitian. History reveals Mr. Brown’s diet is mainly a traditional African American diet, including many high-fat and high-sodium foods.

Scenario B

Tina Aquirre, age 19, is a student at a local community college. She frequently skips breakfast and lunch or grabs a sweet roll and soda midmorning and a candy bar and soda midafternoon. She is experiencing fatigue and inability to concentrate during late afternoon classes.

Scenario C

Sam Minor, a 56-year-old accountant, is diagnosed with hypertension. His blood pressure is 164/100 when he comes to the physician’s office for a checkup.