Prevention and Management of Surgical Complications

This chapter discusses the most common complications occurring during or after oral surgical procedures. Some are minor, whereas others are more serious. These are surgical, not medical, complications; the latter are discussed in Chapter 3.

PREVENTION OF COMPLICATIONS

As is the case of medical complications, the best and easiest way to manage a surgical complication is to prevent it from happening. Prevention of surgical complications is best accomplished by a thorough preoperative assessment and comprehensive treatment plan and careful execution of the surgical procedure. Only when these are routinely performed can the surgeon expect to have few complications. One must realize that even with such planning and with excellent surgical technique, complications occasionally occur. In situations in which the dentist has planned carefully, the complication is often predictable and can be managed routinely. For example, when extracting a maxillary first premolar that has long, thin roots, it is far easier to remove the buccal root than the palatal root. Therefore the surgeon uses more force toward the buccal root than toward the palatal root. If a root does fracture, it is the buccal root rather than the palatal root, and the subsequent buccal root retrieval is more straightforward.

Dentists must perform surgery that is within their limitations of capabilities. They must therefore carefully evaluate their training and ability before deciding to perform a specific surgical task. Thus, for example, it is inappropriate for a dentist with limited experience in the management of impacted third molars to undertake the surgical extraction of an embedded tooth. The incidence of operative and postoperative complications is unacceptably high in this situation. Surgeons must be cautious of unwarranted optimism, which clouds their judgment and prevents them from delivering the best possible care to the patient. The dentist must keep in mind that referral to a specialist is an option that should always be exercised if the planned surgery is beyond the dentist’s own skill level. In some situations, this is not only a moral obligation but also wise medicolegal risk management.

In planning a surgical procedure, the first step is always a thorough review of the patient’s medical history. Several of the complications to be discussed in this chapter can be caused by inadequate attention to medical histories that would have revealed the presence of a factor increasing surgical risk.

One of the primary ways to prevent complications is by obtaining adequate images and carefully reviewing them (see Chapter 7). Radiographs must include the entire area of surgery, including the apices of the roots of the teeth to be extracted and the local and regional anatomic structures, such as adjacent parts of the maxillary sinus and the inferior alveolar canal. The surgeon must look for the presence of abnormal tooth root morphology or signs that the tooth may be ankylosed. After careful examination of the radiographs, the surgeon must occasionally alter the treatment plan to prevent or limit the magnitude of the complications that might be anticipated with a closed extraction. Instead, the surgeon should consider surgical approaches to removing teeth in such cases.

After an adequate medical history has been taken and the radiographs have been analyzed, the surgeon must do the preoperative planning. This is not simply a preparation of a detailed surgical plan and instrumentation but is also a plan for managing patient pain and anxiety and postoperative recovery (instructions and modifications of normal activity for the patient). Thorough preoperative instructions and explanations for the patient are essential in preventing or limiting the impact of the majority of complications that occur in the postoperative period. If the instructions are not carefully explained and the importance of compliance made clear, the patient is less likely to comply with them.

Finally, to keep complications at a minimum, the surgeon must always follow basic surgical principles. There should always be clear visualization and access to the operative field, which requires adequate light, adequate soft tissue retraction and reflection (including lips, cheeks, tongue, and soft tissue flaps), and adequate suction. The teeth to be removed must have an unimpeded pathway for removal. Occasionally, bone must be removed and teeth must be sectioned to achieve this goal. Controlled force is of paramount importance; this means “finesse,” not “force.” The surgeon must follow the principles of asepsis, atraumatic handling of tissues, hemostasis, and thorough débridement of the wound after the surgical procedure. Violation of these principles leads to an increased incidence and severity of surgical complications.

SOFT TISSUE INJURIES

Injuries to the soft tissue of the oral cavity are almost always the result of the surgeon’s lack of adequate attention to the delicate nature of the mucosa, attempts to do surgery with inadequate access, or the use of excessive and uncontrolled force. The surgeon must continue to pay careful attention to the soft tissue while working on bone and tooth structures (Box 11-1).

Tear of a Mucosal Flap

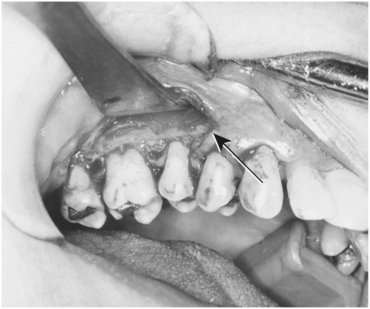

The most common soft tissue injury during oral surgery is the tearing of the mucosal flap during surgical extraction of a tooth. This usually results from an initially inadequately sized envelope flap, which is then forcibly retracted beyond the ability of the tissue to stretch as the surgeon tries to gain needed surgical access (Fig. 11-1). This results in a tearing, usually at one end of the incision. Prevention of this complication is threefold: (1) create adequately sized flaps to prevent excess tension on the flap, (2) use controlled amounts of retraction force on the flap, and (3) create releasing incisions when indicated. If a tear does occur in the flap, the flap should be carefully repositioned once the surgery is complete. Or if the surgeon or assistant sees a flap beginning to tear, the hard tissue surgery can be stopped and the incision can be lengthened to gain better access before continuing the hard tissue surgery. In most patients, careful suturing of the tear results in adequate but somewhat delayed healing. If the tear is especially jagged, the surgeon may consider excising the edges of the torn flap to create a smooth flap margin before closure. This latter step should be performed with caution because excision of excessive amounts of tissue leads to closure of the wound under tension and probable wound dehiscence, or it might compromise the amount of attached gingiva adjacent to a tooth.

Puncture Wound

The second soft tissue injury that occurs with some frequency is inadvertent puncturing of the soft tissue. Instruments, such as a straight elevator or periosteal elevator, may slip from the surgical field and puncture or tear into adjacent soft tissue.

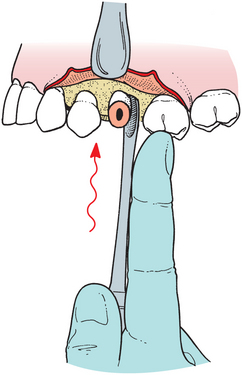

Once again, this injury is the result of using uncontrolled force and is best prevented by the use of controlled force, with special attention given to using finger rests or support from the opposite hand in anticipation of slippage. If the instrument slips from the tooth or bone, the fingers thus catch the hand before injury occurs (Fig. 11-2). When a puncture wound does occur, the treatment is primarily aimed at preventing infection and allowing healing to occur, usually by secondary intention. If the wound bleeds excessively, it should be controlled by direct pressure applied to the wound. Once hemostasis is achieved, the wound is usually left open unsutured so that if a small infection were to occur, there is an adequate pathway for drainage.

Stretch or Abrasion

Abrasions or burns of the lips, corners of the mouth, or flaps usually result from the rotating shank of the bur rubbing on the soft tissue or on a metal retractor in contact with soft tissue (Fig. 11-3). When the surgeon is focused on the cutting end of the bur, the assistant should be aware of the location of the shank of the bur in relation to the cheeks and lips. However, the surgeon should also remain aware of shaft location. If an area of oral mucosa is abraded or burned, little treatment is possible other than keeping the area clean with regular oral rinsing. Usually such wounds heal in 4 to 7 days (depending on the depth of damage) without scarring. If such an abrasion or burn does develop on the skin, the dentist should advise the patient to keep it covered with an antibiotic ointment. The patient must keep the ointment only on the abraded area and not spread onto intact skin because the ointment is likely to cause a rash. These abrasions usually take 5 to 10 days to heal. The patient should keep the area moist with the ointment during the entire healing period to prevent eschar formation and delayed healing, as well as to keep the area reasonably comfortable. Scarring or permanent discoloration of the affected skin may occur but is limited by proper wound care.

FIGURE 11-3 Abrasion of lower lip as a result of shank of burr rotating on soft tissue. Abrasion represents a combination of friction and heat damage. Wound should be kept covered with antibiotic ointment until an eschar forms, taking care to keep the ointment off uninjured skin as much as possible. (Photo courtesy Dr. Myron Tucker.)

PROBLEMS WITH A TOOTH BEING EXTRACTED

The most common problem associated with the tooth being extracted is fracture of its roots. Long, curved, divergent roots that lie in dense bone are the most likely to be fractured. The main methods of preventing fracture of roots is to perform surgery in the manner described in previous chapters or to use an open extraction technique and remove bone to decrease the amount of force necessary to remove the tooth (Box 11-2). Recovery of a fractured root with a surgical approach is discussed in Chapter 8.

Root Displacement

The tooth root that is most commonly displaced into unfavorable anatomic spaces is the maxillary molar root, when it is forced or lost into the maxillary sinus. If a fractured root of a maxillary molar is being removed with a straight elevator being used with excess apical pressure, the tooth root can be displaced into the maxillary sinus. If this occurs, the surgeon must make several assessments to determine the appropriate treatment. First, the surgeon must identify the size of the root lost into the sinus. It may be a root tip of several millimeters or an entire tooth root. The surgeon must next assess whether there has been any infection of the tooth or periapical tissues. If the tooth was not infected, management is more straightforward than if the tooth had been acutely infected. Finally, the surgeon must assess the preoperative condition of the maxillary sinus. For the patient who has a healthy maxillary sinus, it is easier to manage a displaced root than if the sinus is or has been chronically infected.

If the displaced tooth fragment is a small (2 or 3 mm) root tip and the tooth and sinus have no preexisting infection, the surgeon should make a brief attempt at removing the root. First, a radiograph of the fractured tooth root should be taken to document its position and size. Once that has been accomplished, the surgeon should irrigate through the small opening in the socket apex and then suction the irrigating solution from the sinus via the socket. This occasionally flushes the root apex from the sinus through the socket. The surgeon should check the suction solution and confirm radiographically that the root has been removed. If this technique is not successful, no additional surgical procedure should be performed through the socket, and the root tip should be left in the sinus. The small, noninfected root tip can be left in place because it is unlikely to cause any troublesome sequelae. Additional surgery in this situation causes more patient morbidity than leaving the root tip in the sinus. If the root tip is left in the sinus, measures should be taken similar to those taken when leaving any root tip in place. The patient must be informed of the decision and given proper follow-up instructions for regular monitoring of the root and the sinus.

The oroantral communication should be managed as discussed later, with a figure-of-eight suture over the socket, sinus precautions, antibiotics, and a nasal spray to lessen the chance of infection by keeping the ostium open. The most likely occurrence is that the root apex will fibrose onto the sinus membrane with no subsequent problems. If the tooth root is infected or the patient has chronic sinusitis, the patient should be referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon for removal of the root tip via a Caldwell-Luc approach.

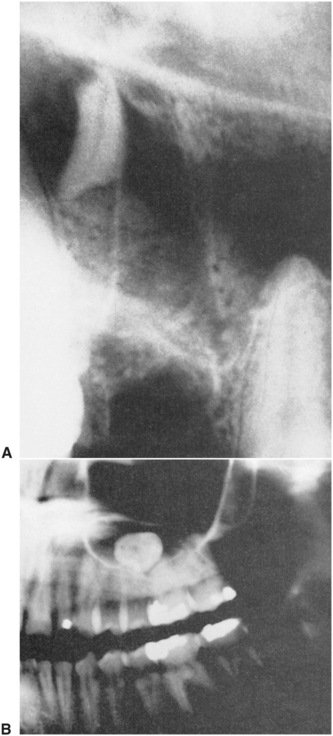

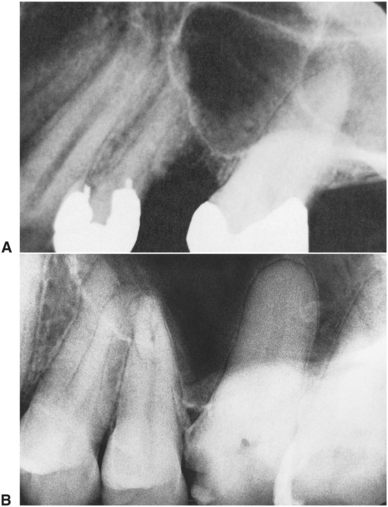

If a large root fragment or the entire tooth is displaced into the maxillary sinus, it should be removed (Fig. 11-4). The usual method is a Caldwell-Luc approach into the maxillary sinus in the canine fossa region and then removal of the tooth. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons perform this procedure (see Chapter 19).

FIGURE 11-4 A, Large root fragment displaced into maxillary sinus. Fragment should be removed with Caldwell-Luc approach. B, Tooth in maxillary sinus is maxillary third molar that was displaced into sinus during elevation of tooth. This tooth must be removed from sinus, probably via a Caldwell-Luc approach.

Impacted maxillary third molars are occasionally displaced into the maxillary sinus (from which they are removed via a Caldwell-Luc approach). But if displacement occurs, it is more commonly into the infratemporal space. During elevation of the tooth, the elevator may force the tooth posteriorly through the periosteum into the infratemporal fossa. The tooth is usually lateral to the lateral pterygoid plate and inferior to the lateral pterygoid muscle. If good access and light are available, the surgeon should make a single cautious effort to retrieve the tooth with a hemostat. However, the tooth is usually not visible, and blind probing results in further displacement. If the tooth is not retrieved after a single effort, the incision should be closed and the operation stopped. The patient should be informed that the tooth has been displaced and will be removed later. Antibiotics should be given to help decrease the possibility of an infection, and routine postoperative care should be provided. During the initial healing time, fibrosis occurs and stabilizes the tooth in a firm position. The tooth is removed later by an oral and maxillofacial surgeon after radiographic localization.

The lingual cortical bone over the roots of the molars becomes thinner as it progresses posteriorly. Mandibular third molars, for example, frequently have dehiscence in the overlying lingual bone and may be actually sitting in the submandibular space preoperatively. Fractured mandibular molar roots that are being removed with apical pressures may be displaced through the lingual cortical plate and into the submandibular space. Even small amounts of apical pressure can result in displacement of the root into that space. Prevention of displacement into the submandibular space is primarily achieved by avoiding all apical pressures when removing the mandibular roots.

Triangular-shaped elevators, such as the Cryer, are usually used to elevate broken tooth roots of mandibular molars. If the root disappears during the root removal, the dentist should make a single effort to remove it. The index finger of the left hand is inserted onto the lingual aspect of the floor of the mouth in an attempt to place pressure against the lingual aspect of the mandible and force the root back into the socket. If this works, the surgeon may be able to tease the root out of the socket with a root tip pick. If this effort is not successful on the initial attempt, the dentist should abandon the procedure and refer the patient to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. The usual, definitive procedure for removing such a root tip is to reflect a soft tissue flap on the lingual aspect of the mandible and gently dissect the overlying mucoperiosteum until the root tip can be found. As with teeth that are displaced into the maxillary sinus, if the root fragment is small and was not infected preoperatively, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon may elect to leave the root in its position because surgical retrieval of the root may be an extensive procedure or risk serious injury to the lingual nerve.

Tooth Lost into the Pharynx

Occasionally, the crown of a tooth or an entire tooth might be lost into the pharynx. If this occurs, the patient should be turned toward the surgeon and placed into position with the mouth toward the floor as much as possible. The patient should be encouraged to cough and spit the tooth out onto the floor. The suction device can sometimes be used to help remove the tooth.

In spite of these efforts, the tooth may be swallowed or aspirated. If the patient has no coughing or respiratory distress, it is most likely that the tooth was swallowed and has traveled down the esophagus into the stomach. However, if the patient has a violent episode of coughing or shortness of breath, the tooth may have been aspirated through the vocal cords into the trachea and from there on to a main stem bronchus.

In either case the patient should be transported to an emergency room, and chest and abdominal radiographs should be taken to determine the specific location of the tooth. If the tooth has been aspirated, consultation should be requested regarding the possibility of removing the tooth with a bronchoscope. The urgent management of aspiration is to maintain the patient’s airway and breathing. Supplemental oxygen may be appropriate if respiratory distress appears to be occurring.

If the tooth has been swallowed, it is highly probable that it will pass through the gastrointestinal tract within 2 to 4 days. Because teeth are not usually jagged or sharp, unimpeded passage occurs in almost all situations. However, it may be prudent to have the patient go to an emergency room and have a radiograph of the abdomen taken to confirm the presence of the tooth in the gastrointestinal tract instead of in the respiratory tract. Follow-up radiographs are probably not necessary because the usual fate of swallowed teeth is passage.

INJURIES TO ADJACENT TEETH

When the dentist extracts a tooth, the focus of attention is on that particular tooth and the application of forces to luxate and deliver it. When the surgeon’s total attention is thus focused, likelihood of injury to the adjacent teeth increases. Injury is often due to use of a bur to remove bone or divide a tooth for removal. The surgeon should take care to avoid getting too close to adjacent teeth when surgically removing a tooth. This usually requires the surgeon to keep some of the focus on structures adjacent to the site of the surgery.

Fracture or Dislodgment of an Adjacent Restoration

The most common injury to adjacent teeth is the inadvertent fracture or dislodgment of a restoration or of a severely carious tooth while the surgeon is attempting to luxate the tooth to be removed with an elevator (Fig. 11-5). If a large restoration exists, the surgeon should warn the patient preoperatively about the possibility of fracturing it during the extraction. Prevention of such a fracture is primarily achieved by avoiding application of instrumentation and force on the restoration (Box 11-3). This means that the straight elevator should be used with great caution, inserting it entirely into the periodontal ligament space, or not used at all to luxate the tooth before extraction when the adjacent tooth has a large restoration. If a restoration is dislodged or fractured, the surgeon should make sure that the displaced restoration is removed from the mouth and does not fall into the empty tooth socket. Once the surgical procedure has been completed, the injured tooth should be treated by replacement of the displaced crown or placement of a temporary restoration. The patient should be informed if a fracture of a tooth or restoration has occurred and that a replacement restoration is needed (see Chapter 12).

FIGURE 11-5 Mandibular first molar. If first molar is to be removed, surgeon must take care not to fracture amalgam in second premolar with elevators or forceps.

Teeth in the opposite arch may also be injured as a result of uncontrolled forces. This usually occurs when buccolingual forces inadequately mobilize a tooth and/or excessive tractional forces are used. The tooth suddenly releases from the socket, and the forceps strikes the teeth of the opposite arch, chipping or fracturing a cusp. This is more likely to occur with extraction of lower teeth because these teeth may require more vertical tractional forces for their delivery, especially when using the No. 23 (cowhorn) forceps. Prevention of this type of injury can be accomplished by several methods. First and primarily, the surgeon should avoid the use of excessive tractional forces. The tooth should be adequately luxated with apical, buccolingual, and rotational forces to minimize the need for tractional forces.

Even when this is done, however, occasionally a tooth releases unexpectedly. The surgeon or assistant should protect the teeth of the opposite arch by holding a finger or suction tip against them to absorb the blow should the forceps be released in that direction. If such an injury occurs, the tooth should be smoothed or restored as necessary to keep the patient comfortable until a permanent restoration can be constructed.

Luxation of an Adjacent Tooth

Inappropriate use of the extraction instruments may luxate an adjacent tooth. Luxation is prevented by judicious use of force with elevators and forceps. If the tooth to be extracted is crowded and has overlapping adjacent teeth, as is commonly seen in the mandibular incisor region, a thin, narrow forceps such as the No. 286 forceps may be useful for the extraction (Fig. 11-6). Forceps with broader beaks should be avoided because they will cause injury and luxation of adjacent teeth.

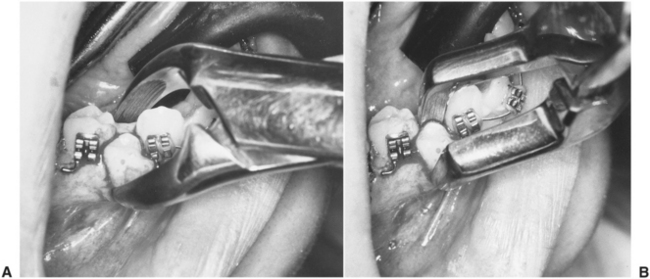

FIGURE 11-6 A, No. 151 forceps, which are too wide to grasp premolar to be extracted without luxating adjacent teeth. B, Maxillary root forceps, which can be adapted easily to tooth for extraction.

If an adjacent tooth is significantly luxated or partially avulsed, the treatment goal is to reposition the tooth into its appropriate position and stabilize it so that adequate healing occurs. This usually requires that the tooth simply be repositioned in the tooth socket and left alone. The occlusion should be checked to ensure that the tooth has not been displaced into a hypererupted and traumatic occlusion. Occasionally, the luxated tooth is mobile. If this is the case, the tooth should be stabilized with semirigid fixation to maintain the tooth in its position. A simple silk suture that crosses the occlusal table and is sutured to the adjacent gingiva is usually sufficient. Rigid fixation with circumdental wires and arch bars results in increased chances for external root resorption and ankylosis of the tooth and therefore should usually be avoided (see Chapter 23).

Extraction of the Wrong Tooth

A complication that every dentist believes can never happen—but happens surprisingly often—is extraction of the wrong tooth. This is usually the most common cause of malpractice lawsuits against dentists. Extraction of the wrong tooth should never occur if appropriate attention is given to the planning and execution of the surgical procedure.

This problem may be the result of inadequate attention to the preoperative assessment. If the tooth to be extracted is grossly carious, it is less likely that the wrong tooth will be removed. A common reason for removing the wrong tooth is that a dentist removes a tooth for another dentist. The use of differing tooth numbering systems or differences in the mounting of radiographs can easily lead the treating dentist to misunderstand the instructions from the referring dentist. Thus the wrong tooth is sometimes extracted when the dentist is asked to remove teeth for orthodontic purposes, especially from patients who are in mixed dentition stages and whose orthodontists have asked for unusual extractions. Careful preoperative planning, good communications with referring dentists, and clinical assessment of which tooth is to be removed before the elevator and forceps are applied are the main methods of preventing this complication (Box 11-4).

If the wrong tooth is extracted and the surgeon realizes this error immediately, the tooth should be replaced quickly into the tooth socket. If the extraction is for orthodontic purposes, the surgeon should contact the orthodontist immediately and discuss whether the tooth that was removed can substitute for the tooth that should have been removed. If the orthodontist believes the original tooth must be removed, the correct extraction should be deferred for 4 or 5 weeks until the fate of the replanted tooth can be assessed. If the wrongfully extracted tooth has regained its attachment to the alveolar process, then the originally planned extraction may proceed. In addition, the surgeon should not extract the contralateral tooth until a definite alternative treatment plan is made.

If the surgeon does not recognize that the wrong tooth was extracted until the patient returns for a postoperative visit, little can be done to correct the problem. Replantation of the extracted tooth after it has dried cannot be successfully accomplished.

When the wrong tooth is extracted, it is important to inform the patient, the patient’s parents (if the patient is a minor), and any other dentist involved with the patient’s care, such as the orthodontist. In some situations the orthodontist may be able to adjust the treatment plan so that extraction of the wrong tooth necessitates only a minor adjustment. And if the case did not involve orthodontic care, a dental implant-supported restoration may totally restore the patient’s dental status as it was before the inadvertent extraction.

INJURIES TO OSSEOUS STRUCTURES

Fracture of the Alveolar Process

The extraction of a tooth usually requires that the surrounding alveolar bone be expanded to allow an unimpeded pathway for tooth removal. However, in some situations the bone fractures and is removed with the tooth instead of expanding. The most likely cause of fracture of the alveolar process is the use of excessive force with forceps, which fractures large portions of cortical plate. If the surgeon realizes that excessive force is necessary to remove a tooth, a soft tissue flap should be elevated, and controlled amounts of bone should be removed so that the tooth can be easily delivered or in the case of multirooted teeth, sectioning of the tooth. If this principle is not adhered to and the surgeon continues to use excessive or uncontrolled force, fracture of the bone commonly occurs.

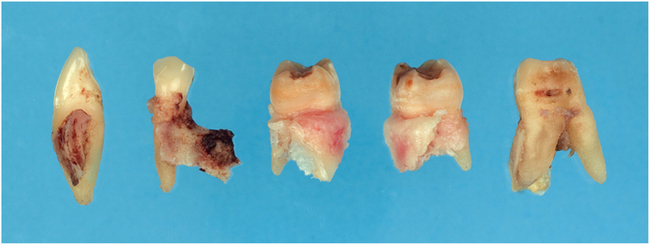

The most likely places for bony fracture are the buccal cortical plate over the maxillary canine, the buccal cortical plate over the maxillary molars (especially the first molar), the portions of the floor of the maxillary sinus associated with maxillary molars, the maxillary tuberosity, and the labial bone on mandibular incisors (Fig. 11-7). All of these bony injuries are caused by excessive force from the forceps.

FIGURE 11-7 Forceps extraction of these teeth resulted in removal of bone and tooth instead of just tooth.

The primary method of preventing these fractures is to perform a careful preoperative examination of the alveolar process, clinically and radiographically (Box 11-5). Surgeons should inspect the root form of the tooth to be removed and assess the proximity of the roots to the maxillary sinus (Fig. 11-8). Surgeons should also check the thickness of the buccal cortical plate overlying the tooth to be extracted (Fig. 11-9). If the roots diverge widely, if they lie close to the sinus, or if the patient has a heavy buccal cortical bone, surgeons must take special measures to prevent fracturing excessive portions of bone. Age is a factor to be considered because the bones of older patients are likely to be less elastic and therefore are more likely to fracture than to expand.

FIGURE 11-8 A, Floor of sinus associated with roots of teeth. If extraction is required, tooth should be removed surgically. B, Maxillary molar teeth immediately adjacent to sinus present increased danger of sinus exposure.

FIGURE 11-9 Patient with heavy buccal cortical plate who requires open extraction. (From Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM et al: Oral and maxillofacial pathology, ed 2, St Louis, 2002, Saunders.)

The surgeon who preoperatively determines that a high probability exists for bone fracture should consider performing the extraction by the open surgical technique. Using this method the surgeon can remove a smaller, more controlled amount of bone, which results in more rapid healing and a more ideal ridge form for prosthetic reconstruction.

When the maxillary molar lies close to the maxillary sinus, surgical exposure of the tooth, with sectioning of the tooth roots into two or three portions prevents the removal of a portion of the maxillary sinus floor. This then prevents the formation of a chronic oroantral fistula, which requires secondary procedures to close.

In summary, prevention of fractures of large portions of the cortical plate depends on preoperative radiographic and clinical assessment, avoidance of the use of excessive amounts of uncontrolled force, and the early decision to perform an open extraction with removal of controlled amounts of bone and sectioning of multirooted teeth. During a forceps extraction, if the appropriate amount of tooth mobilization does not occur early, then the wise and prudent surgeon will alter the treatment plan to the surgical technique instead of pursuing the closed method.

Management of fractures of the alveolar bone takes several different forms, depending on the type and severity of the fracture: If the bone has been completely removed from the tooth socket along with the tooth, it should not be replaced. The surgeon should simply make sure that the soft tissue has been repositioned as best as possible over the remaining bone to prevent delayed healing. The surgeon must also smooth any sharp edges that may have been caused by the fracture. If such sharp edges of bone exist, the surgeon should reflect a small amount of soft tissue and use a bone file to round off the sharp edges or rongeur to remove the sharpness.

The surgeon who has been supporting the alveolar process with the fingers during the extraction usually feels the fracture of the buccal cortical plate when it occurs. At this time the bone remains attached to the periosteum and usually heals if it can be separated from the tooth and left attached to the overlying soft tissue. The surgeon must carefully dissect the bone with its attached associated soft tissue away from the tooth. For this procedure the tooth must be stabilized with the forceps, and a small sharp instrument, such as a No. 9 periosteal elevator, should be used to elevate the buccal bone from the tooth root. One must realize that if the soft tissue flap is reflected from the bone, the blood supply to the overlying bone will be severed and the bone will then undergo necrosis. Once the bone and soft tissue have been elevated from the tooth, the tooth is removed and the bone and soft tissue flap are reapproximated and secured with sutures. When treated in this fashion, it is highly probable that the bone will heal in a more favorable ridge form for prosthetic reconstruction than if the bone had been removed along with the tooth. Therefore, it is worth the special effort to dissect the bone from the tooth.

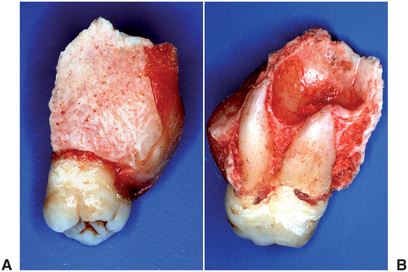

Fracture of the Maxillary Tuberosity

Fracture of a large section of bone in the maxillary tuberosity area is a situation of special concern. The maxillary tuberosity is important for the construction of a stable retentive maxillary denture. If a large portion of this tuberosity is removed along with the maxillary tooth, denture stability is likely to be compromised. The maxillary tuberosity fractures most commonly result from extraction of an erupted maxillary third molar or from extraction of the second molar if it is the last tooth in the arch (Fig. 11-10).

FIGURE 11-10 Tuberosity removed with maxillary second molar, which eliminates important prosthetic retention area and exposes maxillary sinus. A, Buccal view of bone removed with tooth. B, Superior view, looking onto sinus floor, which was removed with tooth. (Courtesy Dr. Edward Ellis III.)

If a tuberosity fracture occurs during an extraction, the treatment is similar to that just discussed for other bony fractures. The surgeon, using finger support for the alveolar process during the fracture (if the bone remains attached to the periosteum), should take measures to ensure the survival of that bony segment. If at all possible, the bony segment should be dissected away from the tooth, and the tooth should be removed in the usual fashion. The tuberosity is then stabilized with mucosal sutures as previously indicated.

However, if the tuberosity is excessively mobile and cannot be dissected from the tooth, the surgeon has several options. The first option is to splint the tooth being extracted to adjacent teeth and defer the extraction for 6 to 8 weeks, allowing time for the bone to heal. The tooth is then extracted with an open surgical technique. The second option is to section the crown of the tooth from the roots and allow the tuberosity and tooth root section to heal. After 6 to 8 weeks the surgeon can reenter the area and remove the tooth roots in the usual fashion. If the maxillary molar tooth was infected before surgery, these two techniques should be used with caution.

If the maxillary tuberosity is completely separated from the soft tissue, the usual steps are to smooth the sharp edges of the remaining bone and to reposition and suture the remaining soft tissue. The surgeon must carefully check for an oroantral communication and treat as necessary.

Fractures of the maxillary tuberosity should be viewed as a significant complication. The major therapeutic goal of management is to maintain the fractured bone in place and to provide the best possible environment for healing. This may be a situation that can best be handled by referral to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon.

INJURIES TO ADJACENT STRUCTURES

During the process of tooth extraction, it is possible to injure adjacent tissues. The prudent surgeon preoperatively evaluates all adjacent anatomic areas and designs a surgical procedure to lessen the chance of injury to these tissues.

Injury to Regional Nerves

The branches of the fifth cranial nerve, which provide innervation to the mucosa and skin, are the adjacent structures most likely to be injured during extraction. The most frequently involved specific branches are the mental nerve, the lingual nerve, the buccal nerve, and the nasopalatine nerve. The nasopalatine and buccal nerves are frequently sectioned during the creation of flaps for removal of impacted teeth. The area of sensory innervation of these two nerves is relatively small, and reinnervation of the affected area usually occurs rapidly. Therefore the nasopalatine and long buccal nerves can be surgically sectioned without long-lasting sequelae or much bother to the patient.

Surgical removal of mandibular premolar roots or impacted mandibular premolars and periapical surgery in the area of the mental nerve and mental foramen must be performed with great care. If the mental nerve is injured, the patient will have a paresthesia or anesthesia of the lip and chin. If the injury is the result of flap reflection or manipulation, normal sensation usually returns in a few days to a few weeks. If the mental nerve is sectioned at its exit from the mental foramen or torn along its course, it is likely that mental nerve function will not return, and the patient will have a permanent state of anesthesia. If surgery is to be performed in the area of the mental nerve or the mental foramen, it is imperative that surgeons have a keen awareness of the potential morbidity from injury to this nerve (Box 11-6). If surgeons have any question concerning their ability to perform the indicated surgical procedure, they should refer the patient to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. If a three-corner flap is to be used in the area of the mental nerve, the vertical-releasing incision must be placed far enough anterior to avoid severing any portion of the mental nerve. Rarely is it advisable to make the vertical-releasing incision at the interdental papilla between the canine and second premolar.

The lingual nerve is usually anatomically located directly against the lingual aspect of the mandible in the retromolar pad region. Occasionally, the path of the lingual nerve takes it into the retromolar pad area itself. The lingual nerve rarely regenerates if it is severely traumatized. Incisions made in the retromolar pad region of the mandible should be placed so as to avoid coming close to this nerve. Therefore, incisions made for surgical exposure of impacted third molars or of bony areas in the posterior molar region should be made well to the buccal aspect of the mandible. Similarly, if dissecting a flap involving the retromolar pad, care must be taken to avoid excessive dissection or stretching of the tissues on the lingual aspect of the retromolar pad. Prevention of injury to the lingual nerve is of paramount importance for avoiding this difficult complication.

Finally, the inferior alveolar nerve may be traumatized along the course of its intrabony canal. The most common place of injury is the area of the mandibular third molar. Removal of impacted third molars may bruise, crush, or sharply injure the nerve in its canal. This complication is common enough during the extraction of third molars that it is important routinely to inform patients preoperatively that it is a possibility. The surgeon must then take every precaution possible to avoid injuring the nerve during the extraction.

Injury to the Temporomandibular Joint

Another major structure that can be traumatized during an extraction procedure in the mandible is the temporomandibular joint. Removal of mandibular molar teeth frequently requires the application of a substantial amount of force. If the jaw is inadequately supported during the extraction to help counteract the forces, the patient may experience pain in this region. Controlled force and adequate support of the jaw prevents this. The use of a bite block on the contralateral side may provide an adequate balance of forces so that injury does not occur (Box 11-7). The surgeon or assistant should also support the jaw by holding the lower border of the mandible. If the patient complains of pain in the temporomandibular joint immediately after the extraction procedure, the surgeon should recommend the use of moist heat, rest for the jaw, a soft diet, and 600 to 800 mg of ibuprofen every 4 hours for several days. Patients who cannot tolerate nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs may take 500 to 1000 mg of acetaminophen.

OROANTRAL COMMUNICATIONS

Removal of maxillary molars occasionally results in communication between the oral cavity and the maxillary sinus. If the maxillary sinus is greatly pneumatized, if little or no bone exists between the roots of the teeth and the maxillary sinus, and if the roots of the tooth are widely divergent, it is common for a portion of the bony floor of the sinus to be removed with the tooth or a communication to be created even if no bone comes out with the tooth. If this problem occurs, appropriate measures are necessary to prevent a variety of sequelae. The two sequelae of most concern are postoperative maxillary sinusitis and formation of a chronic oroantral fistula. The probability that either of these two sequelae will occur is related to the size of the oroantral communication and the management of the exposure.

As with all complications, prevention is the easiest and most efficient method of managing the situation. Preoperative radiographs must be carefully evaluated for the tooth-sinus relationship whenever maxillary molars are to be extracted. If the sinus floor seems to be close to the tooth roots and the tooth roots are widely divergent, the surgeon should avoid a closed extraction and perform a surgical removal with sectioning of tooth roots (Fig. 11-8). Large amounts of force should be avoided in the removal of such maxillary molars (Box 11-8).

Diagnosis of the oroantral communication can be made in several ways: The first is to examine the tooth once it is removed. If a section of bone is adhered to the root ends of the tooth, the surgeon should assume that a communication between the sinus and mouth exists. If a small amount of bone or no bone adheres to the molars, a communication may exist anyway. Some advocate using the nose-blowing test to confirm the presence of a communication. This test involves pinching the nostrils together to occlude the patient’s nose and asking the patient to blow gently through the nose while the surgeon observes the area of the tooth extraction. If a communication exists, there will be passage of air through the tooth socket and bubbling of blood in the socket area. However, if there is not a communication, forceful blowing like this may create a communication. Thus this test should be done only if it will alter treatment.

After the diagnosis of oroantral communication has been established or a strong suspicion exists, the surgeon should guess the approximate size of the communication because the treatment depends on the size of the opening. Probing a small opening may enlarge it, so if no bone came out with the tooth, the communication is likely to be 2 mm or less in diameter. However, if a sizable piece of bone comes out with the tooth, the size of the opening is measurable. If the communication is small (2 mm in diameter or less), no additional surgical treatment is necessary. The surgeon should take measures to ensure the formation of a high-quality blood clot in the socket and then advise the patient to take sinus precautions to prevent dislodgment of the blood clot.

Sinus precautions are aimed at preventing increases or decreases in the maxillary sinus air pressure that would dislodge the clot. Patients should be advised to avoid blowing the nose, violent sneezing, sucking on straws, and pipe or cigar smoking. Patients who smoke and who cannot stop (even temporarily) should be advised to smoke in small puffs, not in deep drags, to avoid pressure changes.

The surgeon must not probe through the socket into the sinus with a dental curette or a root tip pick. The bone of the sinus possibly may have been removed without perforation of the sinus lining. To probe the socket with an instrument might unnecessarily lacerate the membrane. Probing of the communication may also introduce foreign material, including bacteria, into the sinus and thereby further complicate the situation. Probing of the communication is therefore contraindicated.

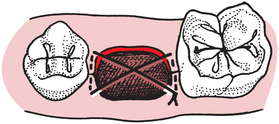

If the opening between the mouth and sinus is of moderate size (2 to 6 mm), additional measures should be taken. To help ensure the maintenance of the blood clot in the area, a figure-of-eight suture should be placed over the tooth socket (Fig. 11-11). Some surgeons also place some clot-promoting substances such as a gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) into the socket before suturing. The patient should also be told to follow sinus precautions. Finally, the patient should be prescribed several medications to help lessen the possibility that maxillary sinusitis will occur. Antibiotics—usually amoxicillin, cephalexin, or clindamycin—should be prescribed for 5 days. In addition, a decongestant nasal spray should be prescribed to shrink the nasal mucosa to maintain ostium patency. As long as the ostium is patent and normal sinus drainage can occur, sinusitis and sinus infection are less likely. An oral decongestant is also sometimes recommended.

FIGURE 11-11 A figure-of-eight stitch is usually performed to help maintain piece of oxidized cellulose in tooth socket.

If the sinus opening is large (7 mm or larger), the surgeon should consider having the sinus communication repaired with a flap procedure. This usually requires that the patient be referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon because flap development and closure of a sinus opening are complex procedures that require special skills and experience.

The most commonly used flap for small openings is a buccal flap. This technique mobilizes buccal soft tissue to cover the opening and provide for a primary closure. This technique should be performed as soon as possible, preferably on the same day in which the opening occurred. The same sinus precautions and medications are usually required (see Chapter 19).

The recommendations just described hold true for patients who have no preexisting sinus disease. If a communication does occur, it is important that the dentist inquire specifically about a history of sinusitis and sinus infections. If the patient has a history of chronic sinus disease, even small oroantral communications may heal poorly and may result in a chronic oroantral communication and eventual fistula. Therefore, creation of an oroantral communication in patients with chronic sinusitis is cause for referral to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon for definitive care (see Chapter 19).

The majority of oroantral communications treated in the methods just recommended heal uneventfully. Patients should be followed carefully for several weeks to ensure that healing has occurred. Even patients who return within a few days with a small communication usually heal spontaneously if no maxillary sinusitis exists. These patients should be followed closely and referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon if the communication persists for longer than 2 weeks. Closure of oroantral fistulae is important because air, water, food, and bacteria go from the oral cavity into the sinus, usually causing a chronic sinusitis. Additionally, if the patient is wearing a full maxillary denture, suction is not as strong; therefore retention of the denture is compromised.

POSTOPERATIVE BLEEDING

Extraction of teeth is a surgical procedure that presents a severe challenge to the hemostatic mechanism of the body. Several reasons exist for this challenge: First, the tissues of the mouth and jaws are highly vascular. Second, the extraction of a tooth leaves an open wound, with soft tissue and bone open, which allows additional oozing and bleeding. Third, it is almost impossible to apply dressing material with enough pressure and sealing to prevent additional bleeding during surgery. Fourth, patients tend to explore the area of surgery with their tongues and occasionally dislodge blood clots, which initiates secondary bleeding. The tongue may also cause secondary bleeding by creating small negative pressures that suction the blood clot from the socket. Finally, salivary enzymes may lyse the blood clot before it has organized and before the ingrowth of granulation tissue.

As with all complications, prevention of bleeding is the best way to manage this problem (Box 11-9). One of the prime factors in preventing bleeding is taking a thorough patient history regarding problems with coagulation. Several questions should be asked of the patient concerning any history of bleeding, particularly after injury or surgery, because affirmative answers to these questions should trigger special efforts to control bleeding (see Chapter 1).

The first question that patients should be asked is whether they have ever had a problem with bleeding in the past. The surgeon should inquire about bleeding after previous tooth extractions or other previous surgery or persistent bleeding after accidental lacerations. The surgeon must listen carefully to the patient’s answers to these questions because the patient’s idea of “persistent” may actually be normal. For example, it is normal for a socket to ooze small amounts of blood for the first 12 to 24 hours after extraction. However, if a patient relates a history of bleeding that persisted for more than a day or that required special attention from the surgeon, then his or her degree of suspicion should be substantially elevated.

The surgeon should inquire about any family history of bleeding. If anyone in the patient’s family has or had a history of prolonged bleeding, further inquiry about its cause should be pursued. Most congenital bleeding disorders are familial, inherited characteristics. These congenital disorders vary from mild to profound, the latter requiring substantial efforts to control.

The patient should next be asked about any medications currently being taken that might interfere with coagulation. Drugs such as anticoagulants may cause prolonged bleeding after extraction. Patients receiving anticancer chemotherapy or aspirin, or who are alcoholics or have severe liver disease may also tend to bleed excessively.

The patient who has a known or suspected coagulopathy should be evaluated by laboratory testing before surgery is performed to determine the severity of the disorder. It is usually advisable to enlist the aid of a hematologist if the patient has a hereditary coagulation disorder.

The means to measure the status of therapeutic anticoagulation is the international normalized ratio (INR). This value takes into account the patient’s prothrombin time and the standardized control. Normal anticoagulated status for most medical indications has an INR of 2.0 to 3.0. It is reasonable to perform extractions on patients who have an INR of 2.5 or less without reducing the anticoagulant dose. With special precautions, it is reasonably safe to do minor amounts of surgery in patients with an INR of up to 3.0, if special local hemostatic measures are taken. If the INR is higher than 3.0, the patient’s physician should be contacted to determine whether the physician would lower the anticoagulant dosage to allow the INR to fall.

Primary control of bleeding during routine surgery depends on gaining control of all factors that may prolong bleeding. Surgery should be as atraumatic as possible, with clean incisions and gentle management of the soft tissue. Care should be taken not to crush the soft tissue because crushed tissue tends to ooze for longer periods. Sharp bony spicules should be smoothed or removed. All granulation tissue should be curetted from the periapical region of the socket and from around the necks of adjacent teeth and soft tissue flaps; however, this should be deferred when anatomic restrictions, such as the sinus or inferior alveolar canal, are present (Fig. 11-12). The wound should be carefully inspected for the presence of any specific bleeding arteries. If such arteries exist in the soft tissue, they should be controlled with direct pressure or, if pressure fails, by clamping the artery with a hemostat and ligating it with a resorbable suture.

FIGURE 11-12 Granuloma of second premolar. Surgeon should not curette periapically around this second premolar to remove granuloma because risk for sinus perforation is high.

The surgeon should also check for bleeding from the bone. Occasionally, a small, isolated vessel bleeds from a bony foramen. If this occurs, the foramen can be crushed with the closed end of a hemostat, thereby occluding the bleeding vessel. Once these measures have been accomplished, the bleeding socket is covered with a damp gauze sponge that has been folded to fit directly into the area from which the tooth was extracted. The patient bites down firmly on this gauze for at least 30 minutes. The surgeon should not dismiss the patient from the office until hemostasis has been achieved. This requires that the surgeon check the patient’s extraction socket about 30 minutes after the completion of surgery. The patient should open the mouth widely, the gauze should be removed, and the area should be inspected carefully for any persistent oozing. Initial control should have been achieved. New damp gauze is then folded and placed into position, and the patient is told to leave it in place for an additional 30 minutes.

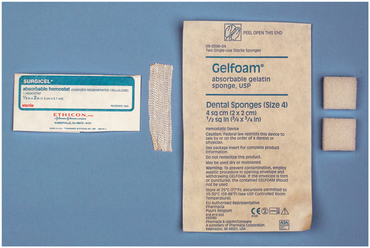

If bleeding persists but careful inspection of the socket reveals that it is not of an arterial origin, the surgeon should take additional measures to achieve hemostasis. Several different materials can be placed in the socket to help gain hemostasis (Fig. 11-13). The most commonly used and the least expensive is the absorbable gelatin sponge (e.g., Gelfoam). This material is placed in the extraction socket and is held in place with a figure-of-eight suture placed over the socket. The absorbable gelatin sponge forms a scaffold for the formation of a blood clot, and the suture helps maintain the sponge in position during the coagulation process. A gauze pack is then placed over the top of the socket and is held with pressure.

FIGURE 11-13 Examples of materials used to help control bleeding from an extraction socket. Surgical is oxidized regenerated cellulose and comes in a silky fabriclike form, whereas Gelfoam is absorbable gelatin that comes as latticework that is easily crushed with pressure. Both promote coagulation.

A second material that can be used to control bleeding is oxidized regenerated cellulose (e.g., Surgicel). This material promotes coagulation better than the absorbable gelatin sponge because it can be packed into the socket under pressure. The gelatin sponge becomes friable when wet and cannot be packed into a bleeding socket. When the cellulose is packed into the socket, it almost always causes some delayed healing of the socket. Therefore packing the socket with cellulose is reserved for more persistent bleeding.

If the surgeon has special concerns about the ability of the patient’s blood to clot, a liquid preparation of topical thrombin (prepared from human recombinant thrombin) can be saturated onto a gelatin sponge and inserted into the tooth socket. The thrombin bypasses steps in the coagulation cascade and helps to convert fibrinogen to fibrin enzymatically, which forms a clot. The sponge with the topical thrombin is secured in place with a figure-of-eight suture. A gauze pack is placed over the extraction site in the usual fashion.

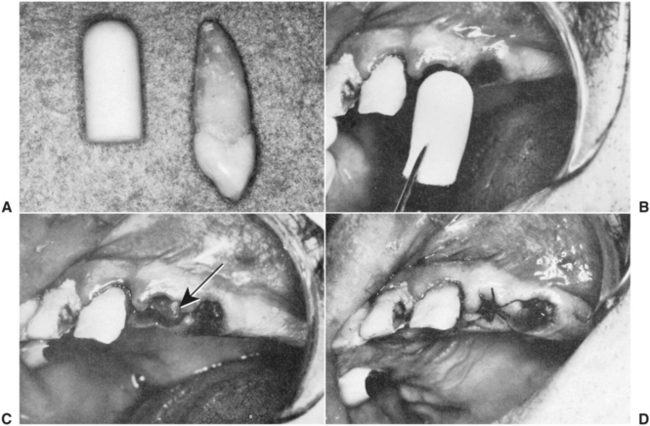

A final material that can be used to help control a bleeding socket is collagen. Collagen promotes platelet aggregation and thereby helps accelerate blood coagulation. Collagen is currently available in several different forms. Microfibular collagen (e.g., Avitene) is available as a fibular material that is loose and fluffy but can be packed into a tooth socket and held in by suturing and gauze packs, as with the other materials. A more highly cross-linked collagen is supplied as a plug (e.g., Collaplug) or as a tape (e.g., Collatape). These materials are more readily packed into a socket (Fig. 11-14) and are easier to use, but they are also more expensive.

FIGURE 11-14 A, Collagen shaped into the form of a plug is similar in size to the root of a maxillary canine. B and C, The collagen plug is placed into the socket with cotton pliers (arrow). D, A figure-of-eight suture is placed over the socket to maintain the collagen in the socket.

Even after primary hemostasis has been achieved, patients occasionally call the dentist with bleeding from the extraction site, referred to as secondary bleeding. The patient should be told to rinse the mouth gently with chilled water and then to place appropriate-sized, damp gauze over the area and bite firmly. The patient should sit quietly for 30 minutes, biting firmly on the gauze. If the bleeding persists, the patient should repeat the cold rinse and bite down on a damp tea bag. The tannin in the tea frequently helps stop the bleeding. If neither of these techniques is successful, the patient should return to the dentist.

The surgeon must have an orderly, planned regimen to control this secondary bleeding. Ideally, a trained dental assistant is present to help. The patient should be positioned in the dental chair, and all blood, saliva, and fluids should be suctioned from the mouth. Such patients frequently have large “liver clots” (clotted blood that resembles fresh liver) in their mouth that must be removed. The surgeon should visualize the bleeding site carefully with good light to determine the precise source of bleeding. If it is clearly seen to be a generalized oozing, the bleeding site is covered with a folded, damp gauze sponge held in place with firm pressure by the surgeon’s finger for at least 5 minutes.

This measure is sufficient to control most bleeding. The reason for the bleeding is usually some secondary trauma that is potentiated by the patient’s continuing to suck on the area or to spit blood from the mouth instead of continuing to apply pressure with a gauze sponge.

If 5 minutes of this treatment does not control the bleeding, the surgeon must administer a local anesthetic so that the socket can be treated more aggressively. Block techniques are to be encouraged instead of local infiltration techniques. Infiltration with solutions containing epinephrine causes vasoconstriction and may control the bleeding temporarily. However, when the effects of the epinephrine dissipate, rebound hemorrhage with recurrent bothersome bleeding may occur.

Once regional local anesthesia has been achieved, the surgeon should gently curette out the tooth extraction socket and suction all areas of old blood clot. The specific area of bleeding should be identified as clearly as possible. As with primary bleeding, the soft tissue should be checked for diffuse oozing versus specific arterial bleeding. The bone tissue should be checked for small nutrient artery bleeding or general oozing. The same measures described for control of primary bleeding should be used. The surgeon must then decide whether a hemostatic agent should be inserted into the bony socket. The use of an absorbable gelatin sponge with topical thrombin held in position with a figure-of-eight stitch and reinforced with application of firm pressure from a small, damp gauze pack is standard for local control of secondary bleeding. This technique works well in almost every bleeding socket. In many situations an absorbable gelatin sponge and gauze pressure are adequate. The patient should be given specific instructions on how to apply the gauze packs directly to the bleeding site should additional bleeding occur. Before the patient with secondary bleeding is discharged from the office, the surgeon should monitor the patient for at least 30 minutes to ensure that adequate hemostasis has been achieved.

If hemostasis is not achieved by any of the local measures just discussed, the surgeon should consider performing additional laboratory screening tests to determine whether the patient has a profound hemostatic defect. The dentist usually requests a consultation from a hematologist, who orders the typical screening tests. Abnormal test results will prompt the hematologist to investigate the patient’s hemostatic system further.

A final hemostatic complication relates to intraoperative and postoperative bleeding into the adjacent soft tissues. Blood that escapes into tissue spaces, especially subcutaneous tissue spaces, appears as bruising of the overlying soft tissue 2 to 5 days after the surgery. This bruising is termed ecchymosis (see Chapter 10).

DELAYED HEALING AND INFECTION

The most common cause of delayed wound healing is infection. Infections are a rare complication after routine dental extraction and are primarily seen after oral surgery that involves the reflection of soft tissue flaps and bone removal. Careful asepsis and thorough wound débridement after surgery can best prevent infection after surgical flap procedures. This means that the area of bone removal under the flap must be copiously irrigated with saline under pressure and that all visible foreign debris must be removed with a curette. Some patients are predisposed to postoperative wound infections and should be given antibiotics perioperatively for prophylaxis (see Chapter 15).

Wound Dehiscence

Another problem of delayed healing is wound dehiscence (separation of the wound edges; Box 11-10). If a soft tissue flap is replaced and sutured without an adequate bony foundation, the unsupported soft tissue flap often sags and separates along the line of incision. A second cause of dehiscence is suturing the wound under tension. This occurs when the surgeon must pull the edges of a wound together with sutures. The closure is under tension if the suture is the only force keeping the edges approximated. If the edges would spring apart if the suture were removed just after being placed, the wound closure is under tension. If the soft tissue flap is sutured under tension, the sutures cause ischemia of the flap margin with subsequent tissue necrosis, which allows the suture to pull through the flap margin and results in wound dehiscence. Therefore, sutures should always be placed in tissue without tension and tied loosely enough to prevent blanching of the tissue.

A common area of exposed bone after tooth extraction is the internal oblique ridge. After extraction of the first and second molar, during the initial healing, the lingual flap becomes stretched over the internal oblique (mylohyoid) ridge. Occasionally, the bone perforates through the thin mucosa, causing a sharp projection of bone in the area.

The two major treatment options are (1) to leave the projection alone or (2) to smooth it with bone file. If the area is left to heal untreated, the exposed bone will slough off in 2 to 4 weeks. If the irritation of the sharp bone is low, this is the preferred method. If a bone file is used, no flap should be elevated because this will result in an increased amount of exposed bone. The file is used only to smooth off the sharp projections of the bone. This procedure usually requires local anesthesia.

Dry Socket

Dry socket or alveolar osteitis is delayed healing but is not associated with an infection. This postoperative complication causes moderate to severe pain but is without the usual signs and symptoms of infection, such as fever, swelling, and erythema. The term dry socket describes the appearance of the tooth extraction socket when the pain begins. In the usual clinical course, pain develops on the third or fourth day after removal of the tooth. Almost all dry sockets occur after the removal of lower molars. On examination the tooth socket appears to be empty, with a partially or completely lost blood clot, and some bony surfaces of the socket are exposed. The exposed bone is sensitive and is the source of the pain. The dull, aching pain is moderate to severe, usually throbs, and frequently radiates to the patient’s ear. The area of the socket has a bad odor, and the patient frequently complains of a foul taste.

The cause of alveolar osteitis is not absolutely clear, but it appears to result from high levels of fibrinolytic activity in and around the tooth extraction socket. This fibrinolytic activity results in lysis of the blood clot and subsequent exposure of the bone. The fibrinolytic activity may result from subclinical infections, inflammation of the marrow space of the bone, or other factors. The occurrence of a dry socket after a routine tooth extraction is rare (2% of extractions), but it is frequent after the removal of impacted mandibular third molars (20% of extractions in some series).

Prevention of the dry socket syndrome requires that the surgeon minimize trauma and bacterial contamination in the area of surgery. The surgeon should perform atraumatic surgery with clean incisions and soft tissue reflection. After the surgical procedure, the wound should be irrigated thoroughly with large quantities of saline delivered under pressure, such as from a plastic syringe. Small amounts of antibiotics (e.g., tetracycline) placed in the socket alone or on a gelatin sponge have been shown to help substantially to decrease the incidence of dry socket in mandibular third molars. The incidence of dry socket can also be decreased by preoperative and postoperative rinses with antimicrobial mouth rinses, such as chlorhexidine. Well-controlled studies indicate that the incidence of dry socket after impacted mandibular third molar surgery can be reduced by 50% or more with these measures.

The treatment of alveolar osteitis is dictated by the single therapeutic goal of relieving the patient’s pain during the period of healing. If the patient receives no treatment, no sequela other than continued pain exists (treatment does not hasten healing).

Treatment is straightforward and consists of irrigation and insertion of a medicated dressing. First, the tooth socket is gently irrigated with sterile saline. The socket should not be curetted down to bare bone because this increases the amount of exposed bone and the pain. Usually the entire blood clot is not lysed, and the part that is intact should be retained. The socket is carefully suctioned of all excess saline, and a small strip of iodoform gauze soaked with the medication is inserted into the socket. The medication contains the following principal ingredients: eugenol, which obtunds the pain from the bone tissue; a topical anesthetic, such as benzocaine; and a carrying vehicle, such as balsam of Peru. The medication can be made by the surgeon’s pharmacist or can be obtained as a commercial preparation from dental supply houses.

The medicated gauze is gently inserted into the socket, and the patient usually experiences profound relief from pain within 5 minutes. The dressing is changed every other day for the next 3 to 6 days, depending on the severity of the pain. The socket is gently irrigated with saline at each dressing change. Once the patient’s pain decreases, the dressing should not be replaced, because it acts as a foreign body and further prolongs wound healing.

FRACTURES OF THE MANDIBLE

Fracture of the mandible during extraction is a rare complication; it is associated almost exclusively with the surgical removal of impacted third molars. A mandibular fracture is usually the result of the application of a force exceeding that needed to remove a tooth and often occurs during the forceful use of dental elevators. However, when lower third molars are deeply impacted, even small amounts of force may cause a fracture. Fractures may also occur during removal of impacted teeth from a severely atrophic mandible. Should such a fracture occur, it must be treated by the usual methods used for jaw fractures. The fracture must be adequately reduced and stabilized. Usually this means that the patient should be referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon for definitive care.

SUMMARY

Prevention of complications should be a major goal of the surgeon. Skillful management of complications when they do occur is the sine qua non of the wise and mature surgeon.

The surgeon who anticipates a high probability of an unusual specific complication should inform the patient and explain the anticipated management and sequelae. Notation of this should be made on the informed consent form that the patient signs.