Infection Control in Surgical Practice

It would be difficult for a person currently living in an industrialized society to have avoided being exposed to modern concepts of personal and public hygiene. Personal cleanliness and public sanitation have been ingrained in the culture of modern civilized societies through parental and public education and are reinforced by government regulations and media advertising. This awareness contrasts starkly with earlier centuries, when the importance of hygienic measures for the control of infectious diseases was not widely appreciated. The monumental work of Semmelweis, Koch, and Lister led to enlightenment about asepsis so that today the use of aseptic techniques seems instinctive.

Despite ongoing advancements in the area of infection control, health professionals must still learn and practice techniques that limit the spread of contagions. This is especially true for dentists performing surgery for two reasons: First, to perform surgery, the dentist typically violates an epithelial surface, the most important barrier against infection. Second, during most oral surgical procedures, the dentist, assistants, and equipment become contaminated with the patient’s blood and saliva.

COMMUNICABLE PATHOGENIC ORGANISMS

Two of the most important pieces of knowledge in any conflict are the identity of the enemy and the enemy’s strengths and weaknesses. In the case of oral surgery, the opposition includes virulent bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, and viruses. The strengths of the opposition are the various means that organisms use to prevent their own destruction, and their weaknesses are their susceptibilities to chemical, biologic, and physical agents. By understanding the “enemy,” the dentist can make rational decisions about infection control.

Bacteria

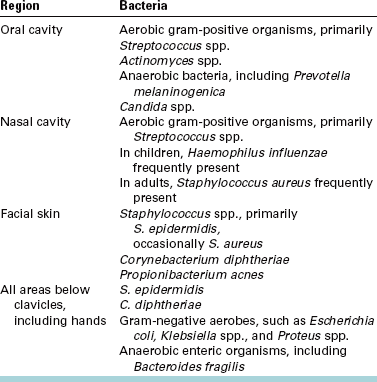

Normal oral flora contains the microorganisms usually present in the saliva and on the surfaces of oral tissues in healthy, immunocompetent individuals who have not been exposed to agents that alter the composition of oral organisms. A complete description of this flora can be found in Chapter 15. In brief, normal oral flora consists of aerobic, gram-positive cocci (primarily streptococci), actinomycetes, anaerobic bacteria, and candidal species (Table 5-1). The total number of oral organisms is held in check by the following four main processes: (1) rapid epithelial turnover with desquamation; (2) host immunologic factors, such as salivary immunoglobulin A; (3) dilution by salivary flow; and (4) competition between oral organisms for available nutrients and attachment sites. Any agent—physical, biologic, or chemical—that alters any of the forces that keep oral microbes under control will permit potentially pathologic organisms to overgrow and set the stage for a wound infection.

The flora of the nose and paranasal sinuses consists primarily of gram-positive aerobic streptococci and anaerobes. In addition, many children harbor Haemophilus influenzae bacteria in these areas, and many adults have Staphylococcus aureus as a part of their transient or resident nasal and paranasal sinus flora. The normal flora in this region of the body is limited by the presence of ciliated respiratory epithelium, secretory immunoglobulins, and epithelial desquamation. The epithelial cilia move organisms trapped in blankets of mucus into the alimentary tract.

Maxillofacial Skin Flora

The skin of the maxillofacial region has surprisingly few resident organisms in its normal flora. The bacteria S. epidermidis and Corynebacterium diphtheriae are the predominant species present. Propionibacterium acnes is found in pores and hair follicles, and many individuals carry S. aureus, spread from their nose, on their facial skin (Table 5-1).

The skin has several means of preventing surface organisms from entering. The most superficial layer of skin is composed of keratinized epithelial cells able to resist mild trauma. In addition, epithelial cells are joined by tight bonds that resist bacterial entrance.

Processes that alter skin flora are, for example, the application of occlusive dressings (which prevent skin desiccation and desquamation), dirt or dried blood (which provide increased nutrients for organisms), and antimicrobial agents (which disturb the balance between various organisms).

Nonmaxillofacial Flora

The flora below the region of the clavicles make up a gradually increasing number of aerobic gram-negative and anaerobic enteric organisms, especially moving toward the pelvic region and unwashed fingertips. General knowledge of these bacteria is important for dental surgeons when preparing themselves for surgery and when treating patients requiring venipuncture or other procedures away from the orofacial region.

Viral Organisms

Viruses are ubiquitous in the environment, but fortunately only a few pose a serious threat to the patient and the surgical team. The viral organisms that cause the most difficulty are the hepatitis B and C viruses and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). These viruses have differences in their susceptibility to inactivation that are important to understand when attempting to prevent their spread. Each virus is described with respect to hardiness and usual mode of transmission. In addition, the circumstances in which the clinician might suspect that an individual is carrying one of these viruses are briefly described, allowing the surgical team to take necessary precautions.

Hepatitis Viruses

Hepatitis A, B, C, and D viruses are responsible for most infectious hepatic diseases. Hepatitis A is spread primarily by contact with the feces of infected individuals. Hepatitis C may spread through contaminated feces or by contaminated blood. Hepatitis B and D are spread by contact with any human secretion.

The hepatitis B virus has the most serious risk of transmission for unvaccinated dentists, their staffs, and their patients. Hepatitis B virus is usually transmitted by the introduction of infected blood into the bloodstream of a susceptible person; however, infected individuals may also secrete large numbers of the virus in their saliva, which can enter an individual through any moist mucosal surface or epithelial (skin or mucosal) wound. Minute quantities of the virus have been found capable of transmitting disease (only 105 to 107 virions/mL blood). Unlike most viruses, the hepatitis virus is exceptionally resistant to desiccation and chemical disinfectants, including alcohols, phenols, and quaternary ammonium compounds. Therefore the hepatitis B virus is difficult to contain, particularly when oral surgery is being performed.

Fortunately, means of inactivating the virus include halogen-containing disinfectants (e.g., iodophor and hypochlorite), formaldehyde, ethylene oxide gas, all types of properly performed heat sterilization, and irradiation. These methods can be used to minimize the spread of hepatitis from one patient to another.

In addition to preventing patient-to-patient spread, the dentist and staff also need to take precautions to protect themselves from contamination, because several instances have occurred in which dentists have been the primary source of a hepatitis B epidemic. Dentists who perform oral surgical procedures are exposed to blood and saliva; therefore the dental surgery team should wear barriers to protect against contaminating any open wounds on the hands and any exposed mucosal surfaces. This includes wearing gloves, a face mask, and eyeglasses or goggles during surgery. The dental staff should continue to wear these protective devices when cleaning instruments and when handling impressions, casts, or specimens from patients. A common means of hepatitis inoculation is injury with a needle or blade that is contaminated with blood or saliva. In addition, members of the dental staff should receive hepatitis B vaccinations, which have been shown to effectively reduce an individual’s susceptibility to hepatitis B infection, although the longevity of protection has not been definitively determined. Finally, office-cleaning personnel and commercial laboratory technicians can be protected by proper segregation and labeling of contaminated objects and by proper disposal of sharp objects (Box 5-1).

Recognition of all individuals known to be carriers of hepatitis B and C would aid in knowing when special precautions were necessary. However, only about half of the persons infected with hepatitis ever have clinical signs and symptoms of the infection, and some individuals who have completely recovered from the disease still shed intact virus particles in their secretions.

The concept of universal precautions was developed to address the inability of health care providers specifically to identify all patients with communicable diseases. The theory on which the universal precautions concept is based is that protection of self, staff, and patients from contamination by using barrier techniques when treating all patients as if they all had a communicable disease ensures that everyone is protected from those who do have an infectious process.

Universal precautions typically include having all doctors and staff who come in contact with patient blood or secretions, whether directly or in aerosol form, wear barrier devices, including a face mask, eye protection, and gloves. Universal precaution procedures go on to include decontaminating or disposing of all surfaces that are exposed to patient blood, tissue, and secretions. Finally, universal precautions mandate avoidance of touching, and thereby contaminating, surfaces (e.g., the dental record, uncovered light handles, and telephone) with contaminated gloves or instruments.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Because of its relative inability to survive outside the host organism, HIV (the cause of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]), acts in a fashion similar to other sexually transmitted infectious disease agents. That is, transfer of the virions from one individual to another requires direct contact between virus-laden blood or secretions from the infected host organism and a mucosal surface or epithelial wound of the potential host. Evidence has shown that the HIV loses its infectivity once desiccated. In addition, few persons carrying HIV secrete the virus in their saliva, and those who do tend to secrete extremely small amounts. No epidemiologic evidence supports the possibility of HIV infection by saliva alone. Even the blood of patients who are HIV-positive has low concentrations of infectious particles (106 particles/mL compared with 1013 particles/mL in hepatitis patients). This probably explains why professionals who are not in any of the known high-risk groups for HIV positivity have an extremely low probability of contracting it, even when exposed to the blood and secretions of large numbers of patients who are HIV-positive during the performance of surgery or if accidentally autoinoculated with contaminated blood or secretions. Nevertheless, until the transmission of HIV becomes fully understood, prudent surgeons will take steps to prevent the spread of infection from the HIV-carrying patient to themselves and their assistants through the use of universal precautions, including barrier techniques.

In general, the universal precautions used for bacterial, mycotic, and other viral processes protect the dentist, office staff, and other patients from the spread of the virus that causes AIDS (Box 5-1). Also important is that patients with depressed immune function be afforded extra care to prevent the spread of contagions to them. Thus all patients infected with HIV who have CD4+ T lymphocyte counts of less than 200/μL or category B or C HIV infection should be treated by doctors and staff free of clinically evident infectious diseases. These patients should not be put in a circumstance in which they are forced to be closely exposed to patients with clinically apparent symptoms of a communicable disease.

Mycobacterial Organisms

The only mycobacterial organism of significance to most dentists is Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Although tuberculosis (TB) is an uncommon disease in the United States and Canada, the frequent movement of persons between countries, including those where TB is common, continues to spread M. tuberculosis organisms worldwide. In addition, some newer strains of M. tuberculosis have become resistant to the drugs historically used to treat TB. Therefore it is important that measures be followed to prevent the spread of TB from patients to the dental team.

TB is transmitted primarily through exhaled aerosols that carry M. tuberculosis bacilli from the infected lungs of one individual to the lungs of another individual. Droplets are produced by those with untreated TB during breathing, coughing, sneezing, and speaking. M. tuberculosis is not a highly contagious microorganism. However, transmission can also occur via inadequately sterilized instruments, because although M. tuberculosis organisms do not form spores, they are highly resistant to desiccation and to most chemical disinfectants. To prevent transmission of TB from an infected individual to the dental staff, the staff should wear face masks whenever treating or in close contact with these patients. The organisms are sensitive to heat, ethylene oxide, and irradiation; therefore, to prevent their spread from patient to patient, all reusable instruments and supplies should be sterilized with heat or ethylene oxide gas. When safe to do so, patients with untreated TB should have their surgery postponed until they can begin treatment for their TB.

ASEPTIC TECHNIQUES AND UNIVERSAL PRECAUTIONS

Different terms are used to describe various means of preventing infection. However, despite their differing definitions, terms such as disinfection and sterilization are often used interchangeably. This can lead to the misconception that a certain technique or chemical has sterilized an object when it has merely reduced the level of contamination. Therefore the dental team must be aware of the precise definition of words used for the various techniques of asepsis.

Sepsis is the breakdown of living tissue by the action of microorganisms and is usually accompanied by inflammation. Thus the mere presence of microorganisms, such as in bacteremia, does not constitute a septic state. Asepsis refers to the avoidance of sepsis. Medical asepsis is the attempt to keep patients, health care staff, and objects as free as possible of agents that cause infection. Surgical asepsis is the attempt to prevent microbes from gaining access to surgically created traumatic wounds.

Antiseptic and disinfectant are terms that are often misused. Both refer to substances that can prevent the multiplication of organisms capable of causing infection. The difference is that antiseptics are applied to living tissue, whereas disinfectants are designed for use on inanimate objects.

Sterility is the freedom from viable forms of microorganisms. Sterility represents an absolute state; there are no degrees of sterility. Sanitization is the reduction of the number of viable microorganisms to levels judged safe by public health standards. Sanitization should not be confused with sterilization. Decontamination is similar to sanitization, except that it is not connected with public health standards.

Concepts

Chemical and physical agents are the two principal means of reducing the number of microbes on a surface. Antiseptics, disinfectants, and ethylene oxide gas are the major chemical means of killing microorganisms on surfaces. Heat, irradiation, and mechanical dislodgment are the primary physical means of eliminating viable organisms (Box 5-2).

The microbes that cause human disease include bacteria, viruses, mycobacteria, parasites, and fungi. The microbes within these groups have variable ability to resist chemical or physical agents. The microorganisms most resistant to elimination are bacterial endospores. Therefore in general, any method of sterilization or disinfection that kills endospores is also capable of eliminating bacteria, viruses, mycobacteria, fungi, mold, and parasites. This concept is used in monitoring the success of disinfection and sterilization techniques.

Techniques of Instrument Sterilization

Any means of instrument sterilization to be used in office-based dental and surgical care must be reliable, practical, and safe for the instruments. The three methods generally available for instrument sterilization are dry heat, moist heat, and ethylene oxide gas.

Sterilization with Heat

Heat is one of the oldest means of destroying microorganisms. Pasteur used heat to reduce the number of pathogens in liquids for preservation. Koch was the first to use heat for sterilization. He found that 1½ hours of dry heat at 100° C would destroy all vegetative bacteria, but that 3 hours of dry heat at 140° C was necessary to eliminate the spores of anthrax bacilli. Koch then tested moist heat and found it a more efficient means of heat sterilization because it reduces the temperature and time necessary to kill spores. Moist heat is probably more effective because dry heat oxidizes cell proteins, a process requiring extremely high temperatures, whereas moist heat causes destructive protein coagulation quickly at relatively low temperatures.

Because spores are the most resistant forms of microbial life, they are used to monitor sterilization techniques. The spore of the bacteria Bacillus stearothermophilus is extremely resistant to heat and is therefore used to test the reliability of heat sterilization. These bacilli can be purchased by hospitals and private offices and run through the sterilizer with the instruments being sterilized. A laboratory then places the heat-treated spores into culture. If no growth occurs, the sterilization procedure was successful.

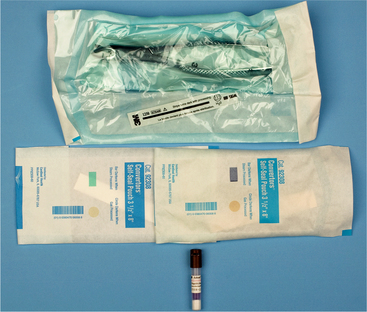

It has been shown that 6 months after sterilization the possibility of organisms entering sterilization bags increases, although some individuals think that an even longer period is acceptable as long as the bags are properly handled. Therefore, all sterilized items should be labeled with an expiration date that is no longer than 6 to 12 months in the future (Fig. 5-1).

FIGURE 5-1 Tests of sterilization equipment. Color-coded packaging is made of paper and cellophane; test areas on package change color on exposure to sterilizing temperatures or to ethylene oxide gas (top and center). Vial contains spores of Bacillus stearothermophilus, which is used for testing efficiency of heat-sterilization equipment (bottom).

A useful alternative technique for sterilely storing surgical instruments is to place them into cassettes that are double wrapped in specifically designed paper and sterilized as a set for use on a single patient.

DRY HEAT.: Dry heat is a method of sterilization that can be provided in most dental offices because the necessary equipment is no more complicated than a thermostatically controlled oven and a timer. Dry heat is most commonly used to sterilize glassware and bulky items that can withstand heat but are susceptible to rust. The success of sterilization depends not only on attaining a certain temperature but also on maintaining the temperature for a sufficient time. Therefore the following three factors must be considered when using dry heat: (1) warm-up time for the oven and the materials to be sterilized, (2) heat conductivity of the materials, and (3) airflow throughout the oven and through the objects being sterilized. In addition, time for the sterilized equipment to cool after heating must be taken into consideration. The time necessary for dry-heat sterilization limits its practicality in the ambulatory setting, because it lengthens the turnover time and forces the dentist to have many duplicate instruments.

The advantages of dry heat are the relative ease of use and the unlikelihood of damaging heat-resistant instruments. The disadvantages are the time necessary and the potential damage to heat-sensitive equipment. Guidelines for the use of dry-heat sterilization are provided in Table 5-2.

TABLE 5-2

Guidelines for Dry-Heat and Steam Sterilization

| Temperature | Duration of Treatment or Exposure* |

| DRY HEAT | |

| 121° C (250° F) | 6-12 hours |

| 140° C (285° F) | 3 hours |

| 150° C (300° F) | 21/2 hours |

| 160° C (320° F) | 2 hours |

| 170° C (340° F) | 1 hour |

| STEAM | |

| 116° C (240° F) | 60 minutes |

| 118° C (245° F) | 36 minutes |

| 121° C (250° F) | 24 minutes |

| 125° C (257° F) | 16 minutes |

| 132° C (270° F) | 4 minutes |

| 138° C (280° F) | 11/2 minutes |

*Times for dry-heat treatments do not begin until temperature of oven reaches goal. Use spore tests weekly to judge effectiveness of sterilization technique and equipment. Use temperature-sensitive monitors each time equipment is used to indicate that sterilization cycle was initiated.

MOIST HEAT.: Moist heat is more efficient than dry heat for sterilization because it is effective at much lower temperatures and requires less time. The reason for this is based on several physical principles. First, water boiling at 100° C takes less time to kill organisms than does dry heat at the same temperature because water is better than air at transferring heat. Second, it takes approximately 7 times as much heat to convert boiling water to steam as it takes to cause the same amount of room temperature water to boil. When steam comes into contact with an object, the steam condenses and almost instantly releases that stored heat energy, which quickly denatures vital cell proteins. Saturated steam placed under pressure (autoclaving) is even more efficient than nonpressurized steam. This is because increasing pressure in a container of steam increases the boiling point of water so that the new steam entering a closed container gradually becomes hotter. Temperatures attainable by steam under pressure include 109° C at 5 psi, 115° C at 10 psi, 121° C at 15 psi, and 126° C at 20 psi (Table 5-2).

The container usually used for providing steam under pressure is known as an autoclave (Fig. 5-2). The autoclave works by creating steam and then, through a series of valves, increasing the pressure so that the steam becomes superheated. Instruments placed into an autoclave should be packaged to allow the free flow of steam to the equipment, such as by placing instruments in paper bags or wrapping them in cotton cloth.

FIGURE 5-2 Office-proportioned autoclave that can be used as a steam and dry-heat sterilizer. (Lisa Sterilizer, Courtesy A-dec, Newburg, Ore.)

Simply placing instruments in boiling water or free-flowing steam results in disinfection rather than sterilization, because at the temperature of 100° C, many spores and certain viruses survive.

The advantages of sterilization with moist heat are its effectiveness, speed, and the relative availability of office-proportioned autoclaving equipment. Disadvantages include the tendency of moist heat to dull and rust instruments and the cost of autoclaves (Table 5-3).

TABLE 5-3

Comparison of Dry-Heat Versus Moist-Heat Sterilization Techniques

| Dry Heat | Moist Heat | |

| Principal antimicrobial effect | Oxidizes cell proteins | Denatures cell proteins |

| Time necessary to achieve sterilization | Long | Short |

| Equipment complexity and cost | Low | High |

| Tendency to dull or rust instruments | Low | High |

| Availability of equipment sized for office use | Good | Good |

Gaseous Sterilization

Certain gases exert a lethal action on bacteria by destroying enzymes and other vital biochemical structures. Of the several gases available for sterilization, ethylene oxide is the most commonly used. Ethylene oxide is a highly flammable gas and is mixed with carbon dioxide or nitrogen to make it safer to use. Because ethylene oxide gas is at room temperature, it can readily diffuse through porous materials, such as plastic and rubber. At 50° C ethylene oxide is effective for killing all organisms, including spores, within 3 hours. However, because it is highly toxic to animal tissue, equipment exposed to ethylene oxide must be aerated for 8 to 12 hours at 50° to 60° C or at ambient temperatures for 4 to 7 days.

The advantages of ethylene oxide for sterilization are its effectiveness for sterilizing porous materials, large equipment, and materials sensitive to heat or moisture. The disadvantages are the need for special equipment and the length of sterilization and aeration time necessary to reduce tissue toxicity. This technique is rarely practical for dental use, unless the dentist has easy access to a large facility willing to gas sterilize dental equipment (e.g., hospital or ambulatory surgery center).

Techniques of Instrument Disinfection

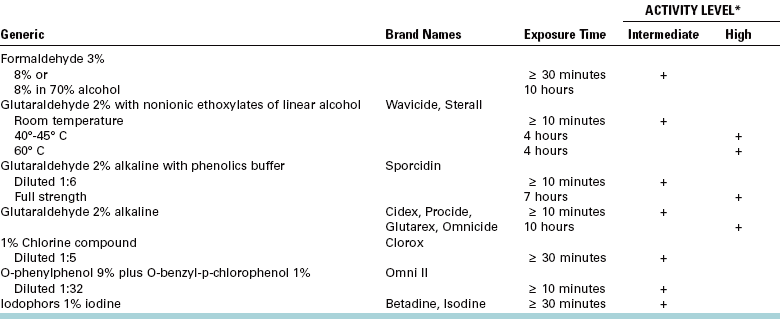

Many dental instruments cannot withstand the temperatures required for heat sterilization. Therefore if gaseous sterilization is not available and absolute sterility is not required, chemical disinfection can be performed. Chemical agents with potential disinfectant capabilities have been classified as being high, intermediate, or low in biocidal activity. The classification is based on the ability of the agent to inactivate vegetative bacteria, tubercle bacilli, bacterial spores, nonlipid viruses, and lipid viruses. Agents with low biocidal activity are effective only against vegetative bacteria and lipid viruses, intermediate disinfectants are effective against all microbes except bacterial spores, and agents with high activity are biocidal for all microbes. The classification depends not only on innate properties of the chemical but also, and just as important, on how the chemical is used (Table 5-4).

TABLE 5-4

Classification System for the Biocidal Effects of Chemical Disinfectants

*In absence of gross organic materials on surfaces being disinfected.

Substances acceptable for disinfecting dental instruments for surgery include glutaraldehyde, iodophors, chlorine compounds, and formaldehyde; glutaraldehyde-containing compounds are the most commonly used. Table 5-5 summarizes the biocidal activity of most of the acceptable disinfecting agents when used properly. Alcohols are not suitable for general dental disinfection, because they evaporate too rapidly; however, they can be used to disinfect local anesthetic cartridges.

TABLE 5-5

Biocidal Activity of Various Chemical Disinfectants

*Grossly visible contamination, such as blood, must be removed before chemical disinfection to maximize biocidal activity.

Quaternary ammonium compounds are not recommended for dentistry because they are not effective against the hepatitis B virus and become inactivated by soap and anionic agents.

Certain procedures must be followed to ensure maximal disinfection, regardless of which disinfectant solution is used. The agent must be properly reformulated and discarded periodically, as specified by the manufacturer. Instruments must remain in contact with the solution for the designated period, and no new contaminated instruments should be added to the solution during that time. All instruments must be washed free of blood or other visible material before being placed in the solution.

Finally, after disinfection the instruments must be rinsed free of chemicals and used within a short time.

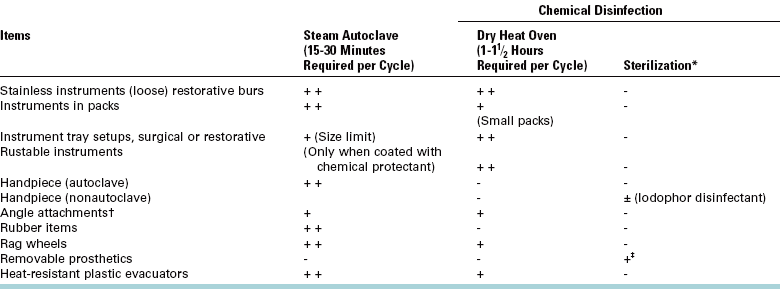

An outline of the preferred method of sterilization for selected dental instruments is presented in Table 5-6.

TABLE 5-6

Methods of Sterilization or Disinfection of Selected Dental Instruments

*Chemical disinfecting/sterilizing solutions are not the method of choice for sterilization of any items used in the mouth. In some circumstances, they may be used when other, more suitable procedures have been precluded.

†Clinician should confirm with manufacturer that attachment is capable of withstanding heat sterilization.

‡Rinse prosthetic well, immerse in 1:10 household bleach solution (5%-6% sodium hypochlorite) for 5 minutes. Rinse the prosthetic (repeat disinfection procedure before returning to patient).

Maintenance of Sterility

Materials and drugs used during oral and maxillofacial surgery—such as sutures, local anesthetics, scalpel blades, and syringes with needles—are sterilized by the manufacturer with a variety of techniques, including gases, autoclaving, filtration, and irradiation. To maintain sterility, the dentist must only properly remove the material or drug from its container. Most surgical supplies are double wrapped (the only common exception is scalpel blades). The outer wrapper is designed to be handled in a nonsterile fashion and usually is sealed in a manner that allows an unsterile individual to unwrap it and discharge the material still wrapped in a sterile inner wrapper. The unsterile individual can allow the surgical material in the sterile inner wrapper to drop onto a sterile part of the surgical field or allow an individual gloved in a sterile fashion to remove the wrapped material in a sterile manner (Fig. 5-3). Scalpel blades are handled in a similar fashion; the unwrapped blade can be dropped onto the field or grasped in a sterile manner by another individual.

FIGURE 5-3 Method of sterilely transferring double-wrapped sterile supplies from clean individual (ungloved hands) to sterilely gowned individual (gloved hands). Package is designed to be peeled open from one end, without touching sterile interior of package. Sterile contents are then promptly presented to recipient.

Surgical Field Maintenance

An absolutely sterile surgical field is impossible to attain. For oral procedures, even a relatively clean field is difficult to maintain because of oral and upper respiratory tract contamination. Therefore, during oral and maxillofacial surgery the goal is to prevent any organisms from the surgical staff or other patients from entering the patient’s wound.

Once instruments are sterilized or disinfected, they should be set up for use during surgery in a manner that limits the likelihood of contamination by organisms foreign to the patient’s maxillofacial flora. A flat platform, such as a Mayo stand, should be used, and two layers of sterile towels or waterproof paper should be placed on it. Then the clinician or assistant should lay the instrument pack on the platform and open out the edges in a sterile fashion. Anything placed on the platform should be sterile or disinfected. Care should be taken not to allow excessive moisture to get on the towels or paper; if the towels become saturated, they can allow bacteria from the unsterile undersurface to wick up to the sterile instruments.

Operatory Disinfection

The various surfaces present in the dental operatory have different requirements concerning disinfection that depend on the potential for contamination and the degree of patient contact with the surface. Any surface that a patient or patient’s secretions contact is a potential carrier of infectious organisms. In addition, when high-speed drilling equipment is used, patient blood and secretions are dispersed over much of the surfaces of the operatory. The operatory can be disinfected in two basic ways. The first is to wipe all surfaces with a hospital-grade disinfectant solution. The second is to cover surfaces with protective shields that are changed between each patient. Fortunately, many chemical disinfectants, including chlorine compounds and glutaraldehyde, can prevent transfer of the hepatitis viruses when used on surfaces in certain concentrations (0.2% for chlorine, 2% for glutaraldehyde). Headrests, tray tables, hosing and lines, nitrous oxide and chair controls, and light handles can be covered with commercially available, single-use, disposable covers; the rest of the dental chair can be quickly sprayed with a disinfectant. Countertops usually come into contact with patients only indirectly, so counters should be periodically disinfected, especially before surgical procedures. Limiting the number of objects left on counters in operatories will make periodic cleaning easier and more effective.

Soap dispensers and sink faucets are another source of contamination. Unless they can be activated without using the hands, they should be disinfected frequently because many bacteria survive—even thrive—in a soapy environment (discussed later in this section). This is one reason common soap is not the ideal agent when preparing hands for surgery.

Anesthetic equipment used to deliver gases, such as oxygen or nitrous oxide, may also spread infection patient to patient. Plastic nasal cannulas are designed to be discarded after one use. Nasal masks and the tubing leading to the mask from the source of the gases are available in disposable form or can be covered with disposable sleeves.

Surgical Staff Preparation

The preparation of the operating team for surgery differs according to the nature of the procedure being performed and the location of the surgery. The two basic types of personnel asepsis to be discussed are (1) the clean technique and (2) the sterile technique. Antiseptics are used during each of the techniques, so they are discussed first.

Hand and Arm Preparation

Antiseptics are used to prepare the surgical team’s hands and arms before gloves are donned and to disinfect the surgical site. Because antiseptics are used on living tissue, they are designed to have low-tissue toxicity while maintaining disinfecting properties. The three antiseptics most commonly used in dentistry are (1) iodophors, (2) chlorhexidine, and (3) hexachlorophene.

Iodophors, such as polyvinylpyrrolidone-iodine (povidone-iodine) solution, have the broadest spectrum of antiseptic action, being effective for gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, most viruses, M. tuberculosis organisms, spores, and fungi.

Iodophors are usually formulated in a 1% iodine solution. The scrub form has an added anionic detergent. Iodophors are preferred over noncompounded solutions of iodine because they are much less toxic to tissue than free iodine and more water soluble. However, iodophors are contraindicated for use on individuals sensitive to iodinated materials, those with untreated hypothyroidism, and pregnant women. Iodophors exert their effect over a period of several minutes, so the solution should remain in contact with the surface for at least a few minutes for maximal effect.

Chlorhexidine and hexachlorophene are other useful antiseptics. Chlorhexidine is used extensively worldwide and is available in the United States as a skin preparation solution and for internal use. The potential for systemic toxicity with repeated use of hexachlorophene has limited its use. Both agents are more effective against gram-positive than gram-negative bacteria, which makes them useful for maxillofacial prepping. Chlorhexidine and hexachlorophene are more effective when used repeatedly during the day because they accumulate on the skin and leave a residual antibacterial effect after each wash. However, their ineffectiveness against tubercle bacilli, spores, and many viruses makes them less effective than iodophors.

Clean Technique

The clean technique is generally used for office-based surgery that does not specifically require a sterile technique. Office oral surgical procedures that call for a sterile technique include any surgery in which skin is incised. The clean technique is designed as much to protect the dental staff and other patients from a particular patient as it is to protect the patient from pathogens that the dental staff may harbor.

When using a clean technique, the dental staff can wear clean street clothing covered by long-sleeved laboratory coats (Fig. 5-4). Another option is a dental uniform (e.g., surgical scrubs), with no further covering or covered by a long-sleeved surgical gown.

FIGURE 5-4 Surgeon ready for office oral surgery, wearing clean gown over street clothes, mask over nose and mouth, cap covering scalp hair, clean gloves, and shatter-resistant eye protection. Nondangling earrings are acceptable in clean technique.

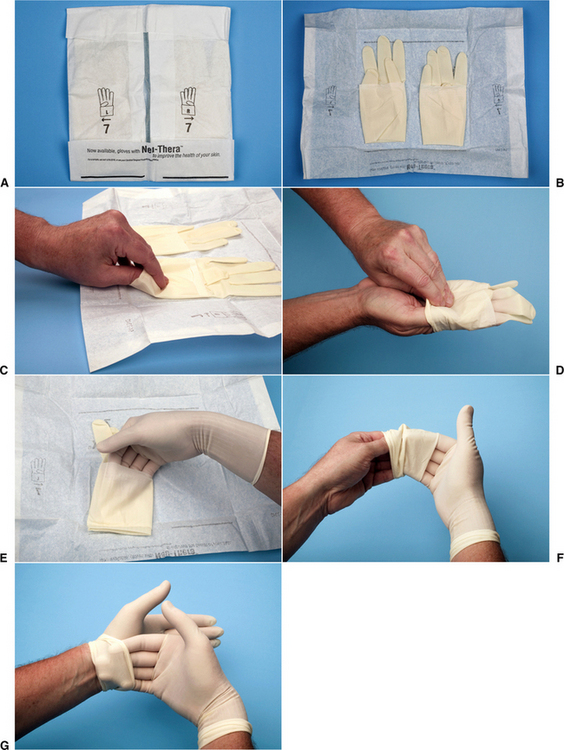

Dentists should wear gloves whenever they are providing dental care. When the clean technique is used, the hands can be washed with antiseptic soap and dried on a disposable towel before gloving. Gloves should be sterile and put on using an appropriate technique to maintain sterility of the external surfaces. The technique of sterile self-gloving is illustrated in Figure 5-5.

FIGURE 5-5 A, Inner wrapper laid open on surface with words facing the person gloving himself. Note that the outside surfaces of this wrapper considered are nonsterile, whereas the inner surface touching the gloves is sterile. B, While touching outside of wrapper, simultaneously pull the folds to each side exposing the gloves. C, Note that the open end of each glove is folded up to create a cuff; using the fingertip of the right hand, grasp the fold of the cuff of the left glove without touching anything else. Bring the glove to the outstretched fingers of the left hand and slide the finger into the glove while using the right hand to help pull the glove on. Release the glove’s cuff without unfolding the cuff. D, Place the fingers of the left hand into the cuff of the right glove. Bring the glove to the outstretched fingers of the right hand. E, Slide the fingers of the right hand into the glove while continuing to hold the glove with the left fingers in the cuff to stabilize the glove. Once the glove is on unfurl the cuff using the fingers still within the cuff. F, Finally place the fingers of the right hand into the cuff of the left glove to unfurl the cuff. The gloves can now be used to ensure that the fingertips of each glove are fully into the glove fingertips while taking care to touch only the sterile glove surfaces (G).

In general, eye protection should be worn when blood or saliva are dispersed, such as when high-speed cutting equipment is used (see Fig. 5-4). A mask should be used whenever aerosols are created or a surgical wound is to be made.

In most cases it is not absolutely necessary to prepare the operative site when using the clean technique. However, when surgery in the oral cavity is performed, the perioral skin may be decontaminated with the same solutions used to scrub the hands and the oral cavity may be prepared by brushing or rinsing with chlorhexidine gluconate (0.12%) or an alcohol-based mouthwash. These procedures reduce the amount of skin or oral mucosal contamination of the wound and decrease the microbial load of any aerosols made while using high-speed drills in the mouth. The dentist may desire to drape the patient to protect the patient’s clothes, to keep objects from accidentally entering the patient’s eyes, and to decrease suture contamination should it fall across an uncovered, unprepared part of the patient’s body.

During an oral surgical procedure, only sterile water or sterile saline solution should be used to irrigate open wounds. A disposable injection syringe, a reusable bulb syringe, or an irrigation pump connected to a bag of intravenous solution can be used to deliver irrigation. Reservoirs feeding irrigation lines to handpieces are also available and can be filled with sterile irrigation fluids.

Sterile Technique

The sterile technique is used for office-based surgery when skin incisions are made or when surgery is performed in an operating room.* The purpose of sterile technique is to minimize the number of organisms that enter wounds created by the surgeon. The technique requires strict attention to detail and cooperation among the members of the surgical team.

The surgical hand and arm scrub is another means of lessening the chance of contaminating a patient’s wound. Although sterile gloves are worn, gloves can be torn (especially when using high-speed drills or working around wires), thereby exposing the surgeon’s skin. By proper scrubbing with antiseptic solutions, the surface bacterial level of the hands and arms is greatly reduced.

Most hospitals have a surgical scrub protocol that should be followed when performing surgery in those institutions. Although several acceptable methods can be used, standard to most techniques is the use of an antiseptic soap solution, a moderately stiff brush, and a fingernail cleaner. The hands and forearms are wetted in a scrub sink, and the hands are kept above the level of the elbows after wetting until the hands and arms are dried. A copious amount of antiseptic soap is applied to the hands and arms from either wall dispensers or antiseptic-impregnated scrub brushes. The antiseptic soap is allowed to remain on the arms while any dirt is removed from underneath each fingernail tip using a sharp-tipped fingernail cleaner.

Then more antiseptic soap is applied and scrubbing is begun, with repeated firm strokes of the scrub brush on every surface of the hands and forearms up to approximately 5 cm from the elbow. Scrub techniques based on the number of strokes to each surface are more reliable than a set time for scrubbing. An individual’s scrub technique should follow a routine that has been designed to ensure that no forearm or hand surface is left improperly prepared. An example of an acceptable surgical scrub technique is shown in Chapter 31.

Postsurgical Asepsis

A few principles of postsurgical care are useful to prevent the spread of pathogens. Wounds should be inspected or dressed by hands that are covered with fresh, clean gloves. When several patients are waiting, those without infectious problems should be seen first, and those with problems such as a draining abscess should be seen afterward.

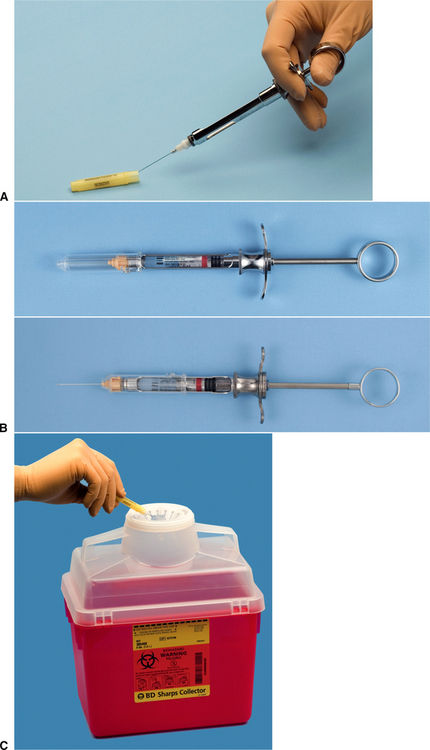

Sharps Management

During and after any surgery, contaminated materials should be disposed of in such a way that the staff and other patients will not be infected. The most common risk for transmission of disease from infected patients to the staff is by accidental needle sticks or scalpel lacerations. Sharps injuries can be prevented by using the local anesthetic needle to scoop up the sheath after use using an instrument such as a hemostat to hold the cover while resheathing the needle or using automatically resheathing needles (Fig. 5-6, A and B); taking care never to apply or remove a blade from a scalpel handle without an instrument; and disposing of used blades, needles, and other sharp disposable items into rigid, well-marked receptacles specially designed for contaminated sharp objects (Fig. 5-6, C). For environmental protection, contaminated supplies should be discarded in properly labeled bags and removed by a reputable hazardous waste management company.