Postoperative Patient Management

Many patients worry about having surgery more because of fears about what it will be like after the surgery than what will occur during the operation. This is particularly true if they trust the effectiveness of the planned method of anesthesia. There are several things the surgeon can do after surgery to diminish these patient concerns and lower the chances of postoperative problems. This chapter discusses those strategies.

Once the surgical procedure has been completed, patients and any accompanying family members should be given proper instructions on how to care for common postsurgical sequelae for the remainder of the day of surgery and a few days thereafter. Postoperative instructions should describe what the patient is likely to experience, explain why these phenomena occur, and tell the patient how to manage and control typical postoperative situations. The instructions must be given to the patient verbally and on a written sheet, and easily understood lay terms should be used. The instruction sheet should describe the typical problems and their management. Instructions should also include a telephone number at which the surgeon or covering doctor can be reached in an emergency.

If the patient is to receive intravenous sedation, the postoperative management instructions must be discussed before the sedation is given and must be repeated to the patient’s escort before discharge from the office. In addition, a written set of postextraction instructions should be given to patients or their escorts. A typical postoperative instruction sheet is found in Appendix V.

CONTROL OF POSTOPERATIVE HEMORRHAGE

Once an extraction has been completed, the initial maneuver to control postoperative bleeding is the placement of a small gauze directly over the socket. Large packs that cover the occlusal surfaces of teeth adjacent to the extraction site do not apply pressure to the bleeding socket and so are ineffective (Fig. 10-1). The gauze may be moistened so that the oozing blood does not coagulate in the gauze and then dislodge the clot when the gauze is removed. The patient should be instructed to bite firmly on this gauze for at least 30 minutes and not to chew on the gauze. The patient should hold the gauze in place without opening or closing the mouth. Talking should be kept to a minimum for 2 to 3 hours.

FIGURE 10-1 A, Fresh extraction site will bleed excessively unless a properly positioned gauze pack is placed, B, Small gauze pack is placed to fit only in area of extraction; this permits pressure to be applied directly to socket. C, Large or mispositioned gauze pack is not effective in controlling bleeding because the pressure of biting is not precisely directed onto the socket.

Patients should be informed that it is normal for a fresh extraction site to ooze slightly for up to 24 hours after the extraction procedure. Patients should be warned that a small amount of blood and a large amount of saliva might appear to be a large amount of blood. If the bleeding is more than a slight ooze, the patient should be told how to reapply a small gauze directly over the area of the extraction. The patient should be instructed to hold this second gauze pack in place for as long as 1 hour to gain control of bleeding. Further control can be attained if necessary by having the patient bite on a tea bag for 30 minutes. The tannic acid in regular tea serves as a local vasoconstrictor.

Patients should be cautioned to avoid things that may aggravate the bleeding. Patients who smoke should be encouraged to avoid smoking for the first 12 hours or, more commonly, if they must smoke, to draw on the cigarette very lightly. Tobacco smoke and nicotine interfere with wound healing. The patient should also be told not to suck on a straw when drinking because this also creates negative pressure. The patient should not spit during the first 12 hours after surgery. The process of spitting involves negative pressure and mechanical agitation of the extraction site, which may trigger fresh bleeding. Patients who object to having blood in the mouth should be encouraged to bite firmly on a piece of gauze to control the hemorrhage and to swallow their saliva instead of spitting it out. Finally, no strenuous exercise should be performed for the first 12 to 24 hours after extraction because the increased blood pressure may result in greater bleeding.

Patients should be warned that there may be some oozing during the night and that they will probably have some blood stains on their pillows. This will prevent many frantic telephone calls to the surgeon in the middle of the night. Patients should also be instructed that if they are worried about their bleeding, they should call to get additional advice. Prolonged oozing, bright red bleeding, or large clots in the patient’s mouth are indications for a return visit. The dentist should then examine the area closely and apply appropriate measures to control the hemorrhage (see Chapter 11).

CONTROL OF POSTOPERATIVE PAIN AND DISCOMFORT

All patients expect a certain amount of pain after a surgical procedure, so it is important for the dentist to discuss this issue carefully with each patient before discharge from the office. The surgeon must help the patient to have a realistic expectation of what type of pain may occur and must pay attention to the patient’s concerns of how much pain is likely to occur.

Patients who tell the surgeon that they expect a great deal of pain after surgery should not be ignored and told to take an over-the-counter analgesic if it hurts; these patients are the ones most likely to experience pain postoperatively. It is important for the surgeon to assure patients, especially the latter group, that their postoperative discomfort can be effectively managed.

The pain a patient may experience after a surgical procedure, such as tooth extraction, is highly variable and depends a great deal on the patient’s preoperative frame of mind. The surgeon who spends several minutes discussing these issues with the patient before surgery will be able to recommend the most appropriate medication.

All patients should be given advice concerning analgesics before they are discharged. Even when the surgeon believes that no prescription analgesics are necessary, the patient should be told to take ibuprofen or acetaminophen postoperatively to prevent initial discomfort when the effect of the local anesthetic disappears. Patients who are expected to have a higher level of pain should be given a prescription analgesic that will control the pain. The surgeon should also take care to advise the patient that the goal of analgesic medication is management of pain and not elimination of all soreness.

The surgeon must understand the three characteristics of the pain that occurs after tooth extraction. First, the pain is usually not severe and can be managed in most patients with mild analgesics. Second, the peak pain experience occurs about 12 hours after the extraction and diminishes rapidly after that. Finally, significant pain from extraction rarely persists longer than 2 days after surgery. With these factors in mind, patients can best be advised regarding the effective use of analgesics.

The first dose of analgesic medication should be taken before the effect of the local anesthetic subsides. If this is done, the patient is less likely to experience the intense, sharp pain after the loss of the local anesthesia. By preventing the sudden onset of surgical pain, the subsequent control of it is more predictably achieved with mild analgesics. Postoperative pain is much more difficult to overcome if administration of analgesic medication is delayed. If the patient waits to take the first dose of analgesic until the effects of the local anesthesia have disappeared, it may take up to 90 minutes for the analgesic to become effective. During this time, the patient is likely to become impatient and take additional medication that will increase the risk of nausea and vomiting.

The strength of the analgesic is also important. Potent analgesics are not required in most routine extraction situations; instead, analgesics with a lower potency per dose are effective. The patient can then be told to take one, two, or three unit doses as necessary to control pain. By allowing the patient to assume an active role in determining the amount of medication to take, more precise control can be achieved.

Patients should be warned that taking too much of narcotic medications will result in drowsiness and an increased chance of gastric upset. In most situations, patients should take medication with some type of food to decrease its irritating effect on the stomach.

Ibuprofen has been demonstrated to be an effective medication to control the pain and discomfort of a tooth extraction. This drug works primarily peripherally, interfering with prostaglandin synthesis. Ibuprofen has the disadvantage of causing a decrease in platelet aggregation and bleeding time, but this does not appear to have a clinically important effect on postoperative bleeding. Acetaminophen does not interfere with platelet function, and it may be useful in certain situations where the patient has a platelet defect and is likely to bleed. If the surgeon prescribes a combination drug of acetaminophen and narcotic, it should be a combination that delivers 500 to 650 mg of acetaminophen per dose.

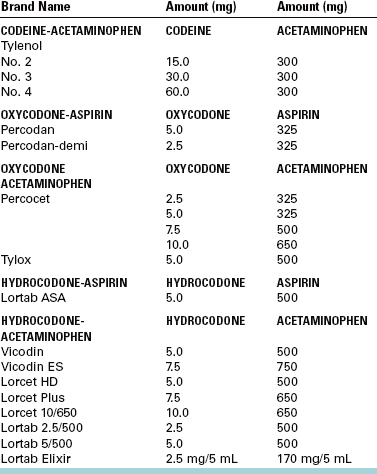

Drugs useful in situations with varying degrees of pain are listed in Table 10-1. Centrally acting opioid analgesics are also frequently used to control pain after tooth extraction. The most commonly used drugs are codeine and the codeine congeners oxycodone and hydrocodone. These narcotics are well absorbed from the gut and can produce drowsiness and gastrointestinal upset. Opioid analgesics are rarely used alone; instead, they are formulated with other analgesics, primarily aspirin or acetaminophen. When codeine is used, the amount of codeine is frequently designated by a numbering system. Compounds labeled No. 1 have 7.5 mg of codeine; No. 2, 15 mg; No. 3, 30 mg; and No. 4, 60 mg. When a combination of analgesic drugs is used, the dentist must keep in mind that it is necessary to provide 500 to 1000 mg of aspirin or acetaminophen every 4 hours to achieve maximal effectiveness from the nonnarcotic. Many of the compound drugs have only 300 mg of aspirin or acetaminophen added to the narcotic. An example of a ratio-nal approach would be to prescribe a compound containing 300 mg of acetaminophen and 15 mg of codeine (No. 2). The usual adult dose would be two tablets of this compound every 4 hours. This two-tablet (30 mg of codeine and 600 mg of acetaminophen) dose provides a nearly ideal analgesic. Should the patient require stronger analgesic action, three tablets can be taken with increased effectiveness of acetaminophen and codeine. Doses that supply 30 to 60 mg of codeine but only 300 mg of acetaminophen fail to take full advantage of the analgesic effect of acetaminophen (Table 10-2).

TABLE 10-1

Analgesics for Postextraction Pain

| Oral Narcotic | Usual Dose |

| MILD PAIN SITUATIONS | |

| Ibuprofen | 400-800 mg q4h |

| Acetaminophen | 500-1000 mg q4h |

| MODERATE PAIN SITUATIONS | |

| Codeine | 15-60 mg |

| Hydrocodone | 5-10 mg |

| SEVERE PAIN SITUATIONS | |

| Oxycodone | 2.5-10 mg |

The Drug Enforcement Administration controls narcotic analgesics. To write prescriptions for these drugs, the dentist must have a Drug Enforcement Administration permit and number. The drugs are categorized into four basic schedules based on their liability for abuse. Several important differences exist between schedule II and schedule III drugs concerning writing prescriptions (see Appendix III).

It is important to emphasize that the most effective method of controlling pain is to build a close relationship between surgeon and patient. Specific time must be spent discussing the issue of postoperative discomfort, with concern clearly expressed by the surgeon. Prescriptions should be given with clear instructions about when to begin the medication and how to take it at each interval. If these procedures are followed, mild analgesics given for a short time (usually no longer than 2 to 3 days) may be all that is required.

Diet

Patients who have had extractions may avoid eating because of local pain or fear of pain when eating. Therefore, they should be given specific instructions regarding their postoperative diet. A high-calorie, high-volume liquid diet is best for the first 12 to 24 hours.

The patient must have an adequate intake of fluids, usually at least 2L, during the first 24 hours. The fluids can be juices, milk, water, or any other beverage that appeals to the patient.

Food in the first 12 hours should be soft and cool. Cool and cold foods help keep the local area comfortable. Ice cream and milkshakes, unlike solid foods, tend not to cause local trauma or initiate rebleeding episodes.

If the patient had multiple extractions in all areas of the mouth, a soft diet is recommended for several days after the surgical procedure. The patient should be advised to return to a normal diet as soon as possible.

Patients who are diabetic should be encouraged to return to their normal insulin and caloric intake as soon as possible. For such patients the surgeon may plan surgery on only one side of the mouth at each surgical sitting, thereby not overly interfering with normal dietary intake.

Oral Hygiene

Patients should be advised that keeping the teeth and mouth reasonably clean results in a more rapid healing of their surgical wounds. Postoperatively on the day of surgery patients may gently brush the teeth that are away from the area of surgery in the usual fashion. They should avoid brushing the teeth immediately adjacent to the extraction site to prevent a new bleeding episode, avoid disturbing sutures, and to avoid pain.

The next day, patients should begin gentle rinses with warm water. The water should be warm but not hot enough to burn the tissue. Most patients can resume preoperative oral hygienic methods by the third or fourth day after surgery. Dental floss should be used in the usual fashion on teeth anterior and posterior to the extraction sites as soon as the patient is sufficiently comfortable.

If oral hygiene is likely to be difficult after extractions in multiple areas of the mouth, mouth rinses with agents such as dilute hydrogen peroxide may be used. Rinsing 3 to 4 times a day for approximately 1 week after surgery may result in more rapid healing.

Edema

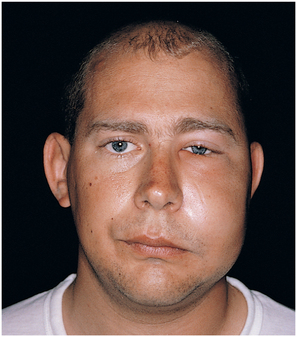

Many surgical procedures result in a certain amount of edema or swelling after surgery. Routine extraction of a single tooth will probably not result in swelling that the patient can see, whereas the extraction of multiple impacted teeth with reflection of soft tissue and removal of bone may result in moderately large amounts of swelling (Fig. 10-2). Swelling usually reaches its maximum 24 to 48 hours after the surgical procedure. Swelling begins to subside on the third or fourth day and is usually resolved by the end of the first week. Increased swelling after the third day may be an indication of infection rather than continued postsurgical edema.

FIGURE 10-2 Extraction of impacted right maxillary and mandibular third molars was performed 2 days before this photograph was taken. Patient exhibits moderate amount of facial edema, which will resolve within 1 week of surgery.

Once the surgery is completed and the patient is ready to be discharged, some dentists use ice packs to help minimize the swelling and make the patient feel more comfortable; however, there is no evidence that the cooling actually controls this type of edema. Ice should not be placed directly on the skin, but rather a layer of dry cloth should be placed between the ice container and the tissue to prevent superficial tissue damage. An ice bag or small bag of frozen peas should be kept on the local area for 20 minutes and then left off for 20 minutes for 12 to 24 hours.

On the second postoperative day, neither ice nor heat should be applied to the face. On the third and subsequent postoperative days, application of heat may help to resolve the swelling more quickly. Heat sources such as hot water bottles and heating pads are recommended. Patients should be warned to avoid high-level heat for long periods to keep from injuring the skin.

Most important is that patients anticipate some amount of swelling. They should also be warned that the swelling may tend to wax and wane, occurring more in the morning and less in the evening because of postural variation. Patients should be informed that a moderate amount of swelling is a normal and healthy reaction of the tissue to the trauma of surgery. Patients should not be concerned or frightened by swelling, because it will resolve within a few days.

Prevention and Recognition of Infection

The principal way to prevent infection following routine extractions is for the surgeon to adhere carefully to the basic principles of surgery. These principles are to minimize tissue damage, remove sources of infection, and cleanse the wound. No other special measures must be taken with the average patient. However, some patients, especially those with depressed host-defense responses, may require antibiotics to prevent infection. Antibiotics in these patients should be administered before the surgical procedure is begun (see Chapter 15). Additional antibiotics after the surgery are usually not necessary for routine extraction in healthy patients.

Infections after routine extractions are unusual. The typical signs are development of a fever, increasing edema or worsening pain 3 to 4 days after surgery. Infected wounds looked inflamed, and some purulence is usually present.

Trismus

Extraction of teeth may result in trismus, or limitation in mouth opening. Trismus results from inflammation involving the muscles of mastication. The trismus may result from multiple injections of local anesthetic, especially if the injections have penetrated muscles. The muscle most likely to be involved is the medial pterygoid muscle, which may be penetrated by the local anesthetic needle during the inferior alveolar nerve block.

Surgical extraction of impacted mandibular third molars usually results in some degree of trismus because the inflammatory response to the surgical procedure is sufficiently widespread to involve several muscles of mastication. Trismus is usually not severe and does not hamper the patient’s activity. However, to prevent alarm, patients should be warned that this phenomenon might occur.

Ecchymosis

In some patients, blood oozes submucosally and subcutaneously, which appears as a bruise in the oral tissues and/or on the face (Fig. 10-3). Blood in the submucosal or subcutaneous tissues is known as ecchymosis. Ecchymosis is usually seen in older patients because of their decreased tissue tone, increased capillary fragility, and weaker intercellular attachment. Ecchymosis is not dangerous and does not increase pain or infection. Patients, however, should be warned that ecchymosis may occur, because if they awaken on the second postoperative day and see bruising in the cheek, submandibular area, or anterior neck, they may become apprehensive. This anxiety is easily prevented by postoperative instructions. Typically, the onset of ecchymosis is 2 to 4 days after surgery and usually resolves within 7 to 10 days.

POSTOPERATIVE FOLLOW-UP VISIT

All patients seen by novice surgeons should be given a return appointment so that the surgeon can check the patient’s progress after the surgery and learn the appearance of a normally healing socket. In routine, uncomplicated procedures, a follow-up visit at 1 week is usually adequate. If sutures are to be removed, that can be done at a 1-week postoperative appointment.

Patients should be informed that if any question or problem arises, they should call the dentist and, if necessary, request an earlier follow-up visit. The most likely reasons for an earlier visit are prolonged bleeding, pain that is not responsive to the prescribed medication, and suspected infection.

If a patient who has had surgery begins to develop swelling with surface redness, fever, and/or pain on the third postoperative day or later, the patient can be assumed to have developed an infection until proved otherwise. The patient should be instructed to call for an appointment at the dentist’s office immediately. The surgeon must then inspect the patient carefully to confirm or rule out the diagnosis of infection. If an infection is diagnosed, appropriate therapeutic measures should be taken (see Chapter 15).

Postsurgical pain that decreases at first but on the third or fourth day begins to increase, yet is not accompanied by swelling or other signs of infection, is probably a sign of “dry socket.” This problem is usually confined to lower molar sockets. This annoying problem is simple to manage but may require that the patient return to the office several times (see Chapter 11).

OPERATIVE NOTE FOR THE RECORDS

The surgeon must enter into the records a note of what transpired during each visit. Some critical factors should be entered into the chart. The first is the date of the operation and a brief identification of the patient; then the surgeon states the diagnosis and reason for the extraction (e.g., nonrestorable caries or severe periodontal disease).

Comments regarding the patient’s pertinent medical history, medications, and vital signs should be mentioned in the chart. This information should be noted in the chart before the surgery is performed to confirm that the dentist has reviewed these issues with the patient and that the patient’s current status is satisfactory for the surgical procedure.

A brief mention should be made of the oral examination. During any routine long-term care of a patient, the dentist should examine the soft tissues of the face, mouth, and upper neck periodically. If this is done at the time of surgery, it should be noted in the chart.

The surgeon should enter into the chart the type and amount of anesthetic used. For example, if the drug were lidocaine with a vasoconstrictor, the dentist would write down the number of milligrams of lidocaine and of epinephrine.

The surgeon should then write a brief note concerning the procedure that was performed, which should include a description of surgery and any complications. A description of the patient’s tolerance of the procedure can also be included.

A comment concerning the discharge instructions, including mention of the postoperative instruction that was given to the patient, is recorded.

The prescribed medications are listed, including the name of the drug, its dose, and the total number of tablets. Alternatively, a copy of the prescriptions can be added to the chart. Finally, the need for a return appointment is recorded in the chart if indicated (Box 10-1). (See Appendix II.)