Discovering the World of Nursing Research

Welcome to the world of nursing research. You might think it is strange to consider research a “world,” but research is truly a new way of experiencing reality. Entering a new world requires learning a unique language, incorporating new rules, and using new experiences to learn how to interact effectively within that world. As you become a part of this new world, your perceptions and methods of reasoning will be modified and expanded. Understanding the world of nursing research is critical to providing evidence-based care to your patients. Since the 1990s, there has been a growing emphasis for nurses, especially advanced practice nurses (APNs), administrators, educators, and nurse researchers, to promote an evidence-based practice in nursing (Brown, 1999; Craig & Smyth, 2007; Malloch & Porter-O’Grady, 2006; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005; Nursing Executive Center, 2005; Pearson, Field, & Jordan, 2007). Evidence-based practice in nursing requires a strong body of research knowledge that nurses must synthesize and use to promote quality care for their patients. We developed this text to facilitate your understanding of nursing research and its contribution to the delivery of evidenced-based nursing practice.

This chapter explains broadly the world of research. We begin with a definition of nursing research, followed by the framework for this text that connects nursing research to the world of nursing. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the significance of research in developing an evidence-based practice for nursing.

DEFINITION OF NURSING RESEARCH

The root meaning of the word research is “search again” or “examine carefully.” More specifically, research is the diligent, systematic inquiry or investigation to validate and refine existing knowledge and generate new knowledge. The concepts systematic and diligent are critical to the meaning of research because they imply planning, organization, and persistence. Many disciplines conduct research, so what distinguishes nursing research from research in other disciplines? In some ways there are no differences, because the knowledge and skills required to conduct research are similar from one discipline to another. However, in looking at other dimensions of research within a discipline, it is clear that research in nursing must also be unique to address the questions relevant to the profession. Nurse researchers need to implement the most effective research methodologies to develop a unique body of knowledge for nursing practice.

In 2003, the American Nurses Association (ANA) developed the following definition of nursing to clarify this unique body of knowledge:

Nursing is the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and abilities, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, communities, and populations.(ANA, 2003, p. 6)

Based on this definition, nursing studies need to focus on understanding human responses and determining the best interventions to promote health, prevent illness, and manage illness. Since the 1960s, the holistic perspective has also influenced the development and implementation of nursing studies and the interpretation of the findings (ANA, 2003; Riley, Beal, Levi, & McCausland, 2002). Many nurses hold the view that nursing research should focus on acquiring knowledge that can be directly applied to clinical practice (Pearson et al., 2007). However, another view is that nursing research should include studies of nursing education, nursing administration, health services, and nurses’ characteristics and roles, as well as clinical situations. Riley et al. (2002) support this view and believe nursing scholarship should include education, practice, and service. The research conducted in these areas will either directly or indirectly influence the development of an evidence-based practice for nursing. Research is needed to identify teaching-learning strategies to promote nurses’ understanding and management of practice. Studies of nursing administration, health services, and nursing roles are necessary to promote quality in the health care system.

Therefore, nursing research generates knowledge that will directly and indirectly influence nursing practice. In this text, nursing research is defined as a scientific process that validates and refines existing knowledge and generates new knowledge that directly and indirectly influences the delivery of evidence-based nursing practice.

FRAMEWORK LINKING NURSING RESEARCH TO THE WORLD OF NURSING

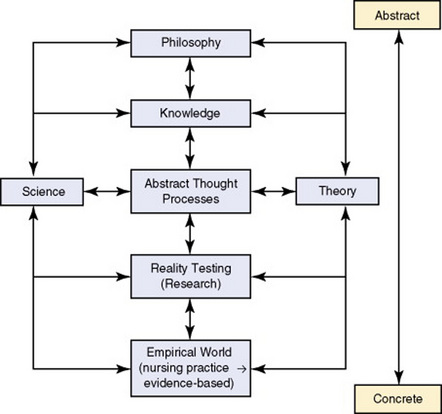

To best explore nursing research, we have developed a framework to help establish connections between research and the various elements of nursing. The framework presented in the following pages links nursing research to the world of nursing and is used as an organizing model for this textbook. In the framework model (see Figure 1-1), nursing research is not an entity disconnected from the rest of nursing but rather is influenced by and influences all other nursing elements. The concepts in this model are pictured on a continuum from concrete to abstract. The discussion introduces this continuum and progresses from the concrete concept of the empirical world of nursing practice to the most abstract concept of nursing philosophy. The use of two-way arrows in the model indicates the dynamic interaction among the concepts.

Concrete-Abstract Continuum

Figure 1-1 presents the components of nursing on a concrete-abstract continuum. This continuum demonstrates that nursing thought flows both from concrete to abstract thinking and from abstract to concrete thinking. Concrete thinking is oriented toward and limited by tangible things or by events that we observe and experience in reality. Thus, the focus of concrete thinking is immediate events that are limited by time and space. Most nurses believe they are concrete thinkers because they focus on the specific actions in nursing practice. Abstract thinking is oriented toward the development of an idea without application to, or association with, a particular instance. Abstract thinkers tend to look for meaning, patterns, relationships, and philosophical implications. This type of thinking is independent of time and space. Currently, graduate nursing education fosters abstract thinking, because it is an essential skill for developing theory and creating an idea for study. Nurses assuming advanced roles need to use both abstract and concrete thinking. For example, a nurse practitioner must explore the best research evidence about a practice problem (abstract thinking) before using his or her clinical expertise to diagnose and manage an individual patient’s health problem (concrete thinking).

Nursing research requires skills in both concrete and abstract thinking. Abstract thought is required to identify researchable problems, design studies, and interpret findings. Concrete thought is necessary in both planning and implementing the detailed steps of data collection and analysis. This back-and-forth flow between abstract and concrete thought may be one reason why nursing research seems complex and challenging.

Empirical World

The empirical world is what we experience through our senses and is the concrete portion of our existence. It is what we often call reality, and “doing” kinds of activities are part of this world. There is a sense of certainty about the empirical or real world; it seems understandable, predictable, controllable. Concrete thinking focuses on the empirical world; words associated with this thinking include “practical,” “down-to-earth,” “solid,” and “factual.” Concrete thinkers want facts. They want to be able to apply whatever they know to the current situation.

The practice of nursing takes place in the empirical world, as demonstrated in Figure 1-1. The scope of nursing practice varies for the registered nurse (RN) and the APN. RNs provide care to and coordinate care for patients, families, and communities in a variety of settings. They initiate interventions and carry out treatments authorized by other health care providers. APNs (nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and clinical nurse specialists) have an expanded practice. Their knowledge, skills, and expertise promote role autonomy and overlap with medical practice. APNs usually concentrate their clinical practice in a specialty area, such as acute care, pediatrics, gerontology, adult, family, psychiatric-mental health, and women’s health (ANA, 2003, 2004). The nursing profession is working toward an evidence-based practice for all types of nurses. The aspects of evidence-based practice and the significance of research in developing evidence-based practice are covered later in this chapter.

Reality Testing

People tend to validate or test the reality of their existence through their senses. In everyday activities, they constantly check out the messages received from their senses. For example, they might ask, “Am I really seeing what I think I am seeing?” Sometimes their senses can play tricks on them. This is why instruments have been developed to record sensory experiences more accurately. For example, does the patient just feel hot or actually have a fever? Thermometers were developed to test this sensory perception accurately. Through research, the most accurate and precise measures have been developed to assess the temperature of patients based on age and health status. Thus, research is a way to test reality and generate the best evidence to guide nursing practice.

Abstract Thought Processes

Abstract thought processes influence every element of the nursing world. In a sense, they link all the elements together. Without skills in abstract thought, we are trapped in a flat existence; we can experience the empirical world, we cannot explain or understand it (Abbott, 1952). Through abstract thinking, however, we can test our theories (which explain the nursing world) and then include them in the body of scientific knowledge. Abstract thinking also allows scientific findings to be developed into theories. Abstract thought enables both science and theories to be blended into a cohesive body of knowledge, guided by a philosophical framework, and applied in clinical practice (see Figure 1-1). Thus, abstract thought processes are essential for synthesizing research evidence and knowing when and how to use this knowledge in practice.

Three major abstract thought processes—introspection, intuition, and reasoning—are important in nursing (Silva, 1977). These thought processes are used in critically appraising and applying best research evidence in practice, planning and implementing research, and developing and evaluating theory.

Introspection

Introspection is the process of turning your attention inward toward your own thoughts. It occurs at two levels. At the more superficial level, you are aware of the thoughts you are experiencing. You have a greater awareness of the flow and interplay of feelings and ideas that occur in constantly changing patterns. These thoughts or ideas can rapidly fade from view and disappear if you do not quickly write them down. When you allow introspection to occur in more depth, you examine your thoughts more critically and in detail. Patterns or links between thoughts and ideas emerge, and you may recognize fallacies or weaknesses in your thinking. You may question what brought you to this point and find yourself really enjoying the experience.

Imagine the following clinical situation. You have just left John Brown’s home. John has a colostomy and has been receiving home health care for several weeks. Although John is caring for his colostomy, he is still reluctant to leave home for any length of time. You are irritated and frustrated with this situation. You begin to review your nursing actions and to recall other patients who reacted in similar ways. What were the patterns of their behavior?

You have an idea: Perhaps the patient’s behavior is linked to the level of family support. You feel unsure about your ability to help the patient and family deal with this situation effectively. You recall other nurses describing similar reactions in their patients, and you wonder how many patients with colostomies have this problem. Your thoughts jump to reviewing the charts of other patients with colostomies and reading relevant ideas discussed in the literature. Some research has been conducted on this topic recently, and you could critically appraise these findings to determine the level of evidence for possible use in practice. If the findings are inadequate, perhaps other nurses would be interested in studying this situation with you.

Intuition

Intuition is an insight or understanding of a situation or event as a whole that usually cannot be logically explained (Rew & Barrow, 1987). Because intuition is a type of knowing that seems to come unbidden, it may also be described as a “gut feeling” or a “hunch.” Because intuition cannot be explained with ease scientifically, many people are uncomfortable with it. Some even say that it does not exist. Sometimes, therefore, the feeling or sense is suppressed, ignored, or dismissed as silly. However, intuition is not the lack of knowing; rather, it is a result of deep knowledge— tacit knowing or personal knowledge (Benner, 1984; Polanyi, 1962, 1966). The knowledge is incorporated so deeply within that it is difficult to bring it consciously to the surface and express it in a logical manner (Beveridge, 1950; Kaplan, 1964).

Intuition is generally considered unscientific and unacceptable for use in research. In some instances, that consideration is valid. For example, a hunch that there is a significant difference between one set of scores and another set of scores is not particularly useful as an analytical technique. However, even though intuition is often unexplainable, it has some important scientific uses. Researchers do not always need to be able to explain something in order to use it. A burst of intuition may identify a problem for study, indicate important variables to measure, or link two ideas together in interpreting the findings. The trick is to recognize the feeling, value it, and hang on to the idea long enough to consider it. Some researchers keep a journal to capture elusive thoughts and hunches as they think about their phenomenon of interest. These intuitive hunches often become important later as they conduct their studies.

Imagine the following situation. You have been working in an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation center for the past 3 years. You and two other nurses working on the unit have been meeting with the clinical nurse specialist to plan a study to determine which factors are important for promoting positive patient outcomes in the rehabilitation program. The group has met several times with a nursing professor at the university, who is collaborating with the group to develop the study. At present, the group is concerned with identifying the factors that need to be measured and how to measure them.

You have had a busy morning. Mr. Green, a patient, stops by to chat on his way out of the clinic. You listen, but not attentively at first. You then become more acutely aware of what he is saying and begin to have a feeling about one variable that should be studied. While he didn’t specifically mention fear of breaking the news about having cancer to his children, you sense that he is anxious about conveying bad news to his loved ones. Although you cannot really explain the origin of this feeling, something in the flow of Mr. Green’s words has stimulated a burst of intuition. You suspect other patients newly diagnosed with cancer face similar fear and hesitation about informing their family members about bad news. You believe the variable “fear of breaking bad news to loved ones” needs to be studied. You feel both excited and uncertain. What will the other nurses think? If the variable has not been studied, is it really significant? Somehow, you feel that it is important to consider.

Reasoning

Reasoning is the processing and organizing of ideas in order to reach conclusions. Through reasoning, people are able to make sense of their thoughts and experiences. This type of thinking is often evident in the verbal presentation of a logical argument in which each part is linked together to reach a logical conclusion. Patterns of reasoning are used to develop theories and to plan and implement research. Barnum (1998) identified four patterns of reasoning as being essential to nursing: (1) problematic, (2) operational, (3) dialectic, and (4) logistic. An individual uses all four types of reasoning, but frequently one type of reasoning is more dominant than the others. Reasoning is also classified by the discipline of logic into inductive and deductive modes (Chinn & Kramer, 2008; Omery, Kasper, & Page, 1995).

Problematic Reasoning: Problematic reasoning involves (1) identifying a problem and the factors influencing it, (2) selecting solutions to the problem, and (3) resolving the problem. For example, nurses use problematic reasoning in the nursing process to identify diagnoses and to implement nursing interventions to resolve these problems. Problematic reasoning is also evident when one identifies a research problem and successfully develops a methodology to examine it.

Operational Reasoning: Operational reasoning involves the identification of and discrimination among many alternatives and viewpoints. It focuses on the process (debating alternatives) rather than on the resolution (Barnum, 1998). Nurses use operational reasoning to develop realistic, measurable health goals with patients and families. Nurse practitioners use operational reasoning to debate which pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments to use in managing patient illnesses. In research, operationalizing a treatment for implementation and debating which measurement methods or data analysis techniques to use in a study require operational thought (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000; Omery et al., 1995).

Dialectic Reasoning: Dialectic reasoning involves looking at situations in a holistic way. A dialectic thinker believes that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts and that the whole organizes the parts (Barnum, 1998). For example, a nurse using dialectic reasoning would view a patient as a person with strengths and weaknesses who is experiencing an illness, and not just as the “stroke in room 219.” Dialectic reasoning also involves examining factors that are opposites and making sense of them by merging them into a single unit or idea that is greater than either alone. For example, analyzing studies with conflicting findings and summarizing these findings to determine the current knowledge base for a research problem require dialectic reasoning.

Logistic Reasoning: Logic is a science that involves valid ways of relating ideas to promote understanding. The aim of logic is to determine truth or to explain and predict phenomena. The science of logic deals with thought processes, such as concrete and abstract thinking, and methods of reasoning, such as logistic, inductive, and deductive.

Logistic reasoning is used to break the whole into parts that can be carefully examined, as can the relationships among the parts. In some ways, logistic reasoning is the opposite of dialectic reasoning. A logistic reasoner assumes that the whole is the sum of the parts and that the parts organize the whole. For example, a patient states that she is cold. You logically examine the following parts of the situation and their relationships: (1) room temperature, (2) patient’s temperature, (3) patient’s clothing, and (4) patient’s activity. The room temperature is 65°F, the patient’s temperature is 98.6°F, and the patient is wearing lightweight pajamas and drinking ice water. You conclude that the patient is cold because of external environmental factors (room temperature, lightweight pajamas, and drinking ice water). Logistic reasoning is used frequently in research to develop a study design, plan and implement data collection, and conduct statistical analyses.

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning: The science of logic also includes inductive and deductive reasoning. People use these modes of reasoning constantly, although the choice of types of reasoning may not always be conscious (Kaplan, 1964). Inductive reasoning moves from the specific to the general, whereby particular instances are observed and then combined into a larger whole or general statement (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). An example of inductive reasoning follows:

A headache is an altered level of health that is stressful.

A fractured bone is an altered level of health that is stressful.

A terminal illness is an altered level of health that is stressful.

Therefore, all altered levels of health are stressful.

In this example, inductive reasoning is used to move from the specific instances of altered levels of health that are stressful to the general belief that all altered levels of health are stressful. By testing many different altered levels of health through research to determine whether they are stressful, one can confirm the general statement that all types of altered health are stressful.

Deductive reasoning moves from the general to the specific or from a general premise to a particular situation or conclusion. A premise or hypothesis is a statement of the proposed relationship between two or more variables. An example of deductive reasoning follows:

In this example, deductive reasoning is used to move from the two general premises about human beings experiencing loss and adolescents being human beings to the specific conclusion, “All adolescents experience loss.” However, the conclusions generated from deductive reasoning are valid only if they are based on valid premises. Consider the following example:

Science

Science is a coherent body of knowledge composed of research findings and tested theories for a specific discipline. Science is both a product (end point) and a process (mechanism to reach an end point) (Silva & Rothbart, 1984). An example from the discipline of physics is Newton’s law of gravity, which was developed through extensive research. The knowledge of gravity (product) is a part of the science of physics that evolved through formulating and testing theoretical ideas (process). The ultimate goal of science is to explain the empirical world and thus to have greater control over it. To accomplish this goal, scientists must discover new knowledge, expand existing knowledge, and reaffirm previously held knowledge in a discipline (Greene, 1979; Toulmin, 1960). Health professionals integrate this evidence-based knowledge to control the delivery of care and thereby improve patient outcomes (evidence-based practice).

The science of a field determines the accepted process for obtaining knowledge within that field. Research is an important process for obtaining scientific knowledge in nursing. Some sciences rigidly limit the types of research that can be used to obtain knowledge. A valued method for developing a science is the traditional research process, or quantitative research. According to this process, the information gained from one study is not sufficient for its inclusion in the body of science. A study must be replicated several times and must yield similar results each time before that information can be considered to be sound empirical evidence (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000; Toulmin, 1960).

Consider the research on the relationships between smoking and lung damage and cancer. Numerous studies conducted on animals and humans over the past few decades indicate relationships between smoking and lung damage and smoking and lung cancer. Everyone who smokes experiences lung damage; and although not everyone who smokes gets lung cancer, smokers are at a much higher risk for cancer. Extensive, quality quantitative research has been conducted to generate empirical evidence about the health hazards of smoking, and this evidence guides the actions of nurses in practice. We provide education, support, and new drugs like chantix (varenicline) to assist individuals to stop smoking.

Findings from studies are systematically related to one another in a way that seems to best explain the empirical world. Abstract thought processes are used to make these linkages. The linkages are called laws, principles, or axioms, depending on the certainty of the facts and relationships within the linkage. Laws express the most certain relationships and provide the best research evidence for use in practice. The certainty depends on the amount of research conducted to test a relationship and, to some extent, on the skills in abstract thought processes to link the research findings to form meaningful evidence. The truths or explanations of the empirical world reflected by these laws, principles, and axioms are never absolutely certain and may be disproved by further research.

Nursing science has been developed through the use of predominantly quantitative research methods. However, since 1980, a strong qualitative research tradition has evolved in nursing. Qualitative research is based on a philosophical orientation toward reality that is different from that of quantitative research (Kikuchi & Simmons, 1994; Marshall & Rossman, 2006; Munhall, 2001). Within the qualitative research tradition, many of the long-held tenets about science and ways of obtaining knowledge are questioned. The philosophical orientation of qualitative research is holistic, and the purpose of this research is to examine the whole rather than the parts. Qualitative researchers are more interested in understanding complex phenomena than in determining cause-and-effect relationships among specific variables. Both quantitative and qualitative research methods are important to the development of nursing knowledge (Craig & Smyth, 2007; Munhall, 2001; Pearson et al., 2007), and some researchers effectively combine these two methods to address selected problems in nursing (Foss & Ellefsen, 2002).

Medicine, health care agencies, and now nursing are focusing on the outcomes of patient care. Outcomes research is an important scientific methodology that has evolved to examine the end results of patient care and the outcomes for health care providers (nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and physicians) and health care agencies (Jones & Burney, 2002). Nurses are also engaged in intervention research, a new methodology for investigating the effectiveness of nursing interventions in achieving the desired outcomes in natural settings (Sidani & Braden, 1998). Nursing is in the beginning stages of developing a science for the profession, and additional original and replication studies are needed to develop the knowledge necessary for practice (Fahs, Morgan, & Kalman, 2003; Pearson et al., 2007).

Theory

A theory is a creative and rigorous structuring of ideas used to describe, explain, predict, or control a particular phenomenon or segment of the empirical world (Chinn & Kramer, 2008; Dubin, 1978). A theory consists of a set of concepts that are defined and interrelated to present a systematic view of a phenomenon. For example, Selye (1976) developed a theory about stress that continues to be useful in describing a person’s response to life events. Extensive research has been conducted to detail the types, number, and severity of stressors experienced in life and the effective interventions to manage these stressful situations.

A theory is developed from a combination of personal experiences, research findings, and abstract thought processes. The theorist may use findings from research as a starting point and then organize the findings to best explain the empirical world. This is the process Selye used to develop his theory of stress. Alternatively, the theorist may use abstract thought processes, personal knowledge, and intuition to develop a theory of a phenomenon. This theory then requires testing through research to determine if it is an accurate reflection of reality. Thus, research has a major role in theory development, testing, and refinement. Qualitative research often focuses on developing or generating theory. Types of quantitative research, outcomes research, and intervention research are often implemented to test the accuracy of theory and to refine aspects of the theory (Chinn & Kramer, 2008; Fawcett & Downs, 1999).

Knowledge

Knowledge is a complex, multifaceted concept. For example, you may say that you know your friend John, know that the earth rotates around the sun, know how to give an injection, and know pharmacology. These are examples of knowing—being familiar with a person, comprehending facts, acquiring a psychomotor skill, and mastering a subject. There are differences in types of knowing, yet there are also similarities. Knowing presupposes order or imposes order on thoughts and ideas (Engelhardt, 1980). People have a desire to know what to expect (Russell, 1948). There is a need for certainty in the world, and individuals seek it by trying to decrease uncertainty through knowledge (Ayer, 1966). Think of the questions you ask a person who has presented some bit of knowledge: “Is it true?” “Are you sure?” “How do you know?” Thus, the knowledge that we acquire is expected to be an accurate reflection of reality.

Ways of Acquiring Nursing Knowledge

We acquire knowledge in a variety of ways and expect it to be an accurate reflection of the real world (White, 1982). Nurses have historically acquired knowledge through (1) traditions, (2) authority, (3) borrowing, (4) trial and error, (5) personal experience, (6) role-modeling and mentorship, (7) intuition, (8) reasoning, and (9) research. Intuition, reasoning, and research were discussed earlier in this chapter; the other ways of acquiring knowledge are briefly described in this section.

Traditions: Traditions consist of “truths” or beliefs that are based on customs and past trends. Nursing traditions from the past have been transferred to the present by written and verbal communication and role-modeling and continue to influence the present practice of nursing. For example, some of the policies and procedures in hospitals and other health care facilities contain traditional ideas. In addition, some nursing interventions are transmitted verbally from one nurse to another over the years or by observation of experienced nurses. For example, the idea of providing a patient with a clean, safe, well-ventilated environment originated with Florence Nightingale (1859).

However, traditions can also narrow and limit the knowledge sought for nursing practice. For example, tradition has established the time and pattern for providing baths, evaluating vital signs, and allowing patient visitation on many hospital units. The nurses on these units quickly inform new staff members about the accepted or traditional behaviors for the unit. Traditions are difficult to change because they have existed for long periods of time and are frequently supported by people with power and authority. Many traditions have not been tested for accuracy or efficiency. The body of knowledge for nursing needs to have an empirical rather than a traditional base. Through the use of evidence-based interventions, nurses can exert a powerful, positive impact on the health care system and patient outcomes.

Authority: An authority is a person with expertise and power who is able to influence opinion and behavior. A person is thought of as an authority because she or he knows more in a given area than others do. Knowledge acquired from authority is illustrated when one person credits another person as the source of information. Nurses who publish articles and books or develop theories are frequently considered authorities. Students usually view their instructors as authorities, and clinical nursing experts are considered authorities within their clinical settings. However, persons viewed as authorities in one field are not necessarily authorities in other fields. An expert is an authority only when addressing his or her area of expertise. Like tradition, the knowledge acquired from authorities sometimes has not been validated through research and is not considered the best evidence for practice.

Borrowing: As some nursing leaders have noted, knowledge in the nursing practice is partly made up of information that has been borrowed from disciplines such as medicine, psychology, physiology, and education (Andreoli & Thompson, 1977; McMurrey, 1982). Borrowing in nursing involves the appropriation and use of knowledge from other fields or disciplines to guide nursing practice.

Nursing practice has borrowed knowledge in two ways. For years, some nurses have taken information from other disciplines and applied it directly to nursing practice. This information was not integrated within the unique focus of nursing. For example, some nurses have used the medical model to guide their nursing practice, thus focusing on the diagnosis and treatment of physiological diseases with limited attention to the patient’s holistic nature. This type of borrowing continues today as nurses use technological advances to focus on the detection and treatment of disease, to the exclusion of health promotion and illness prevention.

Another way of borrowing, which is more useful in nursing, is the integration of information from other disciplines within the focus of nursing. Because disciplines share knowledge, it is sometimes difficult to know where the boundaries exist between nursing’s knowledge base and those of other disciplines. Boundaries blur as the knowledge bases of disciplines evolve (McMurrey, 1982). For example, information about self-esteem as a characteristic of the human personality is associated with psychology, but this knowledge also directs the nurse in assessing the psychological needs of patients and families. However, borrowed knowledge has not been adequate for answering many questions generated in nursing practice.

Trial and Error: Trial and error is an approach with unknown outcomes that is used in a situation of uncertainty, when other sources of knowledge are unavailable. The profession evolved through a great deal of trial and error before knowledge of effective practices was codified in textbooks and journals. Because each patient responds uniquely to a situation, there is uncertainty in nursing practice. Because of this uncertainty, nurses must use trial and error in providing care. However, with trial and error, there is frequently no formal documentation of effective and ineffective nursing actions. When this strategy is used, the knowledge a practitioner gains from experience often is not shared with others. The trial-and-error way of acquiring knowledge can also be time-consuming, because multiple interventions might be implemented before one is found to be effective. There is also a risk of implementing nursing actions that are detrimental to a patient’s health.

Personal Experience: Personal experience is the knowledge that comes from being personally involved in an event, situation, or circumstance. In nursing, personal experience enables one to gain skills and expertise by providing care to patients and families in clinical settings. The nurse not only learns but is able to cluster ideas into a meaningful whole. For example, students may be told how to give an injection in a classroom setting, but they do not know how to give an injection until they observe other nurses giving injections to patients and actually give several injections themselves.

The amount of personal experience you have will affect the complexity of your knowledge base as a nurse. Benner (1984) described five levels of experience in the development of clinical knowledge and expertise: (1) novice, (2) advanced beginner, (3) competent, (4) proficient, and (5) expert. Novice nurses have no personal experience in the work that they are to perform, but they have preconceived notions and expectations about clinical practice that are challenged, refined, confirmed, or contradicted by personal experience in a clinical setting. The advanced beginner has just enough experience to recognize and intervene in recurrent situations. For example, the advanced beginner nurse is able to recognize and intervene to meet patients’ needs for pain management.

Competent nurses frequently have been on the job for 2 or 3 years, and their personal experiences enable them to generate and achieve long-range goals and plans. Through experience, the competent nurse is able to use personal knowledge to take conscious, deliberate actions that are efficient and organized. From a more complex knowledge base, the proficient nurse views the patient as a whole and as a member of a family and community. The proficient nurse recognizes that each patient and family have specific values and needs that lead them to respond differently to illness and health.

The expert nurse has had extensive experience and is able to identify accurately and intervene skillfully in a situation. Personal experience increases an expert nurse’s ability to grasp a situation intuitively with accuracy and speed. The clinical expertise of the nurse is a critical component of evidence-based practice. It is the expert nurse who has the greatest skill and ability to implement the best research evidence in practice to meet the unique values and needs of patients and families.

Role-Modeling and Mentorship: Role-modeling is learning by imitating the behaviors of an exemplar. An exemplar or role model knows the appropriate and rewarded roles for a profession, and these roles reflect the attitudes and include the standards and norms of behavior for that profession (Bidwell & Brasler, 1989). In nursing, role-modeling enables the novice nurse to learn from interacting with expert nurses or following their examples. Examples of role models are “admired teachers, practitioners, researchers, or illustrious individuals who inspire students through their examples” (Werley & Newcomb, 1983, p. 206).

An intense form of role-modeling is mentorship. In a mentorship, the expert nurse, or mentor, serves as a teacher, sponsor, guide, exemplar, and counselor for the novice nurse (or mentee). Both the mentor and the mentee or protégé invest time and effort, which often results in a close, personal mentor-mentee relationship. This relationship promotes a mutual exchange of ideas and aspirations relative to the mentee’s career plans. The mentee assumes the values, attitudes, and behaviors of the mentor while gaining intuitive knowledge and personal experience. Mentorship is essential for building research competence in nursing (Byrne & Keefe, 2002).

To summarize, in nursing, a body of knowledge must be acquired (learned), incorporated, and assimilated by each member of the profession and collectively by the profession as a whole. This body of knowledge guides the thinking and behavior of the profession and individual practitioners. It also directs further development and influences how science and theory are interpreted within the discipline. This knowledge base is necessary in order for health professionals, consumers, and society to recognize nursing as a science.

Philosophy

Philosophy provides a broad, global explanation of the world. It is the most abstract and most all-encompassing concept in the model (see Figure 1-1). Philosophy gives unity and meaning to the world of nursing and provides a framework within which thinking, knowing, and doing occur (Kikuchi & Simmons, 1994). Nursing’s philosophical position influences its knowledge base. How nurses use science and theories to explain the empirical world depends on their philosophy. Ideas about truth and reality, as well as beliefs, values, and attitudes, are part of philosophy. Philosophy asks questions such as, “Is there an absolute truth, or is truth relative?” “Is there one reality, or is reality different for each individual?”

Everyone’s world is modified by her or his philosophy, as a pair of eyeglasses would modify vision. Perceptions are influenced first by philosophy and then by knowledge. For example, if what you see is not within your ideas of truth or reality, if it does not fit your belief system, you may not see it. Your mind may reject it altogether or may modify it to fit your philosophy (Scheffler, 1967). As you start to discover the world of nursing research, it is important for you to keep an open mind to the value of research and your future role in the development or use of research evidence in practice.

Philosophical positions commonly held within the nursing profession include the view that human beings are holistic, rational, and responsible. Nurses believe that people desire health, and health is considered to be better than illness. Quality of life is as important as quantity of life. Good nursing care facilitates improved patterns of health and quality of life (ANA, 2003, 2004). In nursing, truth is relative, and reality tends to vary with perception (Kikuchi, Simmons, Romyn, 1996; Silva, 1977). For example, because nurses believe that reality varies with perception and that truth is relative, they would not try to impose their views of truth and reality on patients. Rather, they would accept patients’ views of the world and help them seek health from within those worldviews, which is a critical component of evidence-based practice. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the significance of research in developing an evidence-based practice for nursing.

SIGNIFICANCE OF RESEARCH IN BUILDING AN EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE FOR NURSING

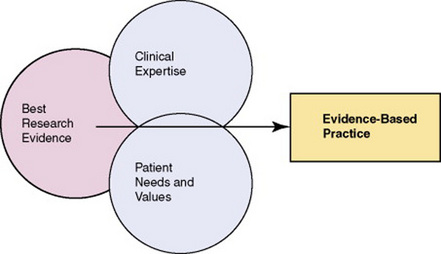

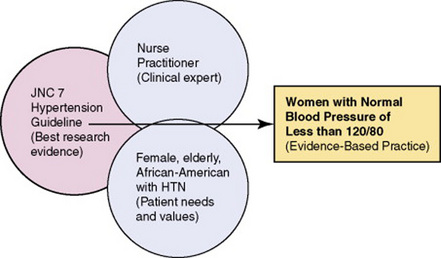

The ultimate goal of nursing is to provide evidence-based care that promotes quality outcomes for patients, families, health care providers, and the health care system (Craig & Smyth, 2007; Pearson et al., 2007). Evidence-based practice (EBP) evolves from the integration of the best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient needs and values (Institute of Medicine, 2001; Sackett, Straus, Richardson, Rosenberg, & Haynes, 2000). Figure 1-2 demonstrates the major contribution of the best research evidence to the delivery of EBP. The best research evidence is the empirical knowledge generated from the synthesis of quality study findings to address a practice problem. A discussion of the levels of best research evidence and the sources for this evidence are presented in Chapter 2. A team of expert researchers, health care professionals, policy makers, and consumers often synthesizes the best research evidence for developing standardized guidelines for clinical practice. For example, research related to the chronic health problem of hypertension (HTN) has been conducted, critically appraised, and synthesized by experts to develop a practice guideline for implementation by APNs (such as nurse practitioners and clinical specialists) and physicians to ensure that patients with HTN receive quality, cost-effective care (Chobanian et al., 2003). The most current guidelines for the treatment of HTN, “The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report,” were published in 2003 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (Chobanian et al., 2003) and are available online at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension. Many national standardized guidelines are available through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which is discussed in more detail in Chapters 2 and 27 of this text.

Clinical expertise is the knowledge and skills of the health care professional providing care. A nurse’s clinical expertise is determined by his or her years of practice, current knowledge of the research and clinical literature, and educational preparation. The stronger the nurse’s clinical expertise, the better his or her clinical judgment in the delivery of quality care (Craig & Smyth, 2007; Sackett et al., 2000). The patient’s need(s) might focus on health promotion, illness prevention, acute or chronic illness management, or rehabilitation (see Figure 1-2). In addition, patients bring values or unique preferences, expectations, concerns, and cultural beliefs to the clinical encounter. With EBP, patients and their families are encouraged to take an active role in managing their health care (Pearson et al., 2007). In summary, expert clinicians use the best research evidence available to deliver quality, cost-effective care to a patients and families with specific health needs and values to achieve EBP (see Figure 1-2) (Brown, 1999; Craig & Smyth, 2007; Sackett et al., 2000).

Figure 1-3 provides an example of the delivery of evidence-based care to women with HTN. In this example, the best research evidence on HTN is the JNC 7 National Standardized Guideline (Chobanian et al., 2003). This guideline is translated by an expert nurse practitioner to meet the needs (chronic illness management) and values of elderly African-American women with HTN. In this case, the outcome of EBP is women with a normal blood pressure of less than 120/80 (see Figure 1-3). A detailed discussion of how to locate, critically appraise, and use national standardized guidelines (such as the JNC 7) in practice is presented in Chapter 27.

In nursing, the research evidence must focus on the description, explanation, prediction, and control of phenomena important to practice. The following sections address the types of knowledge that need to be generated in these four areas as nursing moves toward EBP.

Description

Description involves identifying and understanding the nature of nursing phenomena and, sometimes, the relationships among them (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). Through research, nurses are able to (1) describe what exists in nursing practice, (2) discover new information, (3) promote understanding of situations, and (4) classify information for use in the discipline. Some examples of clinically important research evidence developed from research focused on description include the following:

• Identification of the responses of individuals to a variety of health conditions

• Description of the health promotion and illness prevention strategies used by various populations

• Determination of the incidence of a disease locally, nationally, and internationally.

• Identification of the cluster of symptoms for a particular disease

• Description of the effects and side effects of selected pharmacological agents in a variety of populations

For example, Ryan et al. (2007) conducted a study to determine the cluster of symptoms that represent an acute myocardial infarction (AMI). These researchers synthesized their findings as follows:

Symptoms of AMI occur in clusters, and these clusters vary among persons. None of the clusters identified in this study included all of the symptoms that are included typically as symptoms of AMI (chest discomfort, diaphoresis, shortness of breath, nausea, and lightheadedness). These AMI symptom clusters must be communicated clearly to the public in a way that will assist them in assessing their symptoms more efficiently and will guide their treatment-seeking behavior. Symptom clusters for AMI must also be communicated to the professional community in a way that will facilitate assessment and rapid intervention for AMI. (Ryan et al., 2007, p. 72)

The findings from this study provide insights into the varying symptom clusters of patients experiencing an AMI. This type of research, focused on description, is essential groundwork for studies that will help to explain, predict, and control nursing phenomena.

Explanation

Explanation clarifies the relationships among phenomena and clarifies why certain events occur. Research focused on explanation provides the following types of evidence essential for practice:

• Determination of the assessment data (both subjective data from the health history and objective data from physical exam) needed to address a patient’s health need

• Link of assessment data to determine a diagnosis (both nursing and medical)

• Link of causative risk factors or etiologies to illness, morbidity, and mortality

• Determine the relationships among health risks, health status, and health care costs

For example, Pronk Goodman, O’Connor, and Martinson (1999) studied the relationships between modifiable health risks (physical inactivity, obesity, and smoking) and health care charges and found that adverse health risks translate into significantly higher health care charges. Thus, managed health care systems, nurse providers, and consumers seeking to improve societal health and reduce health care costs need to promote the modification of health risks. Explanatory research continues to link sedentary behaviors to obesity and diabetes in adults (Hu, Li, Colditz, Willett, & Manson, 2003) and to link the prenatal environment and cumulated social risk factors in the overweight adolescent (Salsberry & Reagan, 2007). These studies illustrate how explanatory research can identify relationships among nursing phenomena that are the basis for research focused on prediction and control.

Prediction

Through prediction, one can estimate the probability of a specific outcome in a given situation (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). However, predicting an outcome does not necessarily enable one to modify or control the outcome. It is through prediction that the risk of illness is identified and linked to possible screening methods that will identify the illness. Knowledge generated from research focused on prediction is critical for EBP and includes the following:

• Prediction of the risk for a disease in different populations

• Prediction of the accuracy and precision of a screening instrument, such as mammogram, to detect a disease

• Prediction of the prognosis once an illness is identified in a variety of populations

• Prediction of behaviors that promote health and prevent illness

• Prediction of the health care required based on a patient’s need and values

For example, Scheetz and Kolassa (2007, p. 399) examined “crash scene variables to predict the need for trauma center care in older persons.” The researchers analyzed 26 crash scene variables and developed triage decision rules for managing persons with severe and moderate injuries. Further research is needed to determine whether the triage decision rules improve the health outcomes of the elderly following trauma. Predictive studies isolate independent variables that require additional research to ensure that their manipulation or control results in successful outcomes for patients, health care professionals, and health care agencies (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000; Omery et al., 1995).

Control

If one can predict the outcome of a situation, the next step is to control or manipulate the situation to produce the desired outcome. Dickoff, James, and Wiedenbach (1968) described control as the ability to write a prescription to produce the desired results. Using the best research evidence, nurses could prescribe specific interventions to meet the needs of patients and their families. This is the type of research evidence that nurses need in order to provide EBP (see Figure 1-2). Research in the following areas is important for generating an evidence-based practice in nursing:

• Testing interventions to improve the health status of individuals, families, and communities

• Testing interventions to improve health care delivery

• Determining the quality and cost-effectiveness of interventions

• Implementing an evidence-based intervention to determine if it is effective in managing a patient’s health need (health promotion, illness prevention, acute and chronic illness management, and rehabilitation) and producing quality outcomes

Lusk, Ronis, Kazanis, Eakin, Hong, and Raymond (2003) conducted a study that implemented a prescribed, tailored intervention to increase the use of hearing protection devices (HPDs) by factory workers. They found that significantly more workers used HPDs in the intervention group than in the other groups. Thus, this intervention manipulated or controlled the situation to produce the positive outcome of HPD use in a noisy work environment.

Only a limited number of studies have been conducted to generate the research evidence in the areas of prediction and control that is needed for EBP in nursing (Pearson et al., 2007). Thus, there is a great need for additional research in nursing and many opportunities for you to be involved in the world of nursing research.

This chapter introduced you to the world of nursing research and the significance of research in developing an evidence-based practice for nursing. The following chapters will expand your ability to critically appraise studies, synthesize research findings, and use the best research evidence available in clinical practice. The text also provides you with a background for conducting research in collaboration with expert nurse researchers. We think you will find that nursing research is an exciting adventure that holds much promise for the future practice of nursing.

SUMMARY

• This chapter introduces you to the world of nursing research.

• Nursing research is defined as a scientific process that validates and refines existing knowledge and generates new knowledge that directly and indirectly influences the delivery of evidence-based nursing practice.

• This chapter presents a framework that links nursing research to the world of nursing and organizes the content presented in this textbook (see Figure 1-1). The concepts in this framework range from concrete to abstract and include concrete and abstract thinking, the empirical world (evidence-based nursing practice), reality testing (research), abstract thought processes, science, theory, knowledge, and philosophy.

• The goal of nurses and other health care professionals is to deliver evidence-based health care to patients and their families.

• Evidence-based practice (EBP) evolves from the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient needs and values (see Figure 1-2).

• The best research evidence is the empirical knowledge generated from the synthesis of quality studies to address a practice problem.

• The clinical expertise of a nurse is determined by his or her years of clinical experience, current knowledge of the research and clinical literature, and educational preparation.

• The patient brings values—such as unique preferences, expectations, concerns, and cultural beliefs, and health needs—to the clinical encounter.

• The knowledge generated through research is essential for describing, explaining, predicting, and controlling nursing phenomena.

• Reliance on tradition, authority, trial and error, and personal experience is no longer an adequate basis for sound nursing practice.

• Nursing practice based on synthesized research findings can have a powerful, positive impact on patient outcomes and the health care system.

REFERENCES

Abbott, E.A. Flatland. New York: Dover, 1952.

American Nurses Association. Nursing’s social policy statement, (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Author; 2003.

American Nurses Association. Nursing: Scope and standards of practice. Washington, DC: Author, 2004.

Andreoli, K.G., Thompson, C.E. The nature of science in nursing. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1977;9(2):32–37.

Ayer, A.J. The problem of knowledge. Baltimore: Penguin, 1966.

Barnum, B.S. Nursing theory: Analysis, application, evaluation, (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998.

Benner, P. From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley, 1984.

Beveridge, W.I.B. The art of scientific investigation. New York: Vintage Books, 1950.

Bidwell, A.S., Brasler, M.L. Role modeling versus mentoring in nursing education. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1989;21(1):23–25.

Brown, S.J. Knowledge for health care practice: A guide to using research evidence. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1999.

Byrne, M.W., Keefe, M.R. Building research competence in nursing through mentoring. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34(4):391–396.

Chinn, P.L., Kramer, M.K. Theory and nursing: Integrated knowledge development, (6th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby, 2008.

Chobanian, A.V., Bakris, G.L., Black, H.R., Cushman, W.C., Green, L.A., Izzo, J.L., et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(19):2560–2572.

Craig, J.V., Smyth, R.L. The evidence-based practice manual for nurses, (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.

Dickoff, J., James, P., Wiedenbach, E. Theory in a practice discipline: Practice oriented theory (Part I). Nursing Research. 1968;17(5):415–435.

Dubin, R. Theory building, (Rev. ed.). New York: Free Press, 1978.

Engelhardt, H.T., Jr., Knowing and valuing: Looking for common roots. Engelhardt, H.T., Callahan, D., eds., Knowing and valuing: The search for common roots, Vol. 4. New York: Hastings Center, 1980:1–17.

Fahs, P.S., Morgan, L.L., Kalman, M. A call for replication. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2003;35(1):67–71.

Fawcett, J., Downs, F.S. The relationship of theory and research, (3rd ed.). Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1999.

Foss, C., Ellefsen, B. Methodological issues in nursing research: The value of combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in nursing research by means of method triangulation. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;40(2):242–248.

Greene, J.A. Science, nursing and nursing science: A conceptual analysis. Advances in Nursing Science. 1979;2(1):57–64.

Hu, F.B., Li, T.Y, Colditz, G.A., Willett, W.C., Manson, J.E. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(14):1785–1791.

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001.

Jones, K.R., Burney, R.E. Outcomes research: An interdisciplinary perspective. Outcomes Management. 2002;6(3):103–109.

Kaplan, A. The conduct of inquiry. New York: Harper & Row, 1964.

Kerlinger, F.N., Lee, H.B. Foundations of behavioral research, (4th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers, 2000.

Kikuchi, J.F., Simmons, H. Developing a philosophy of nursing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994.

Kikuchi, J.F., Simmons, H., Romyn, D. Truth in nursing inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996.

Lusk, S.L., Ronis, D.L., Kazanis, A.S., Eakin, B.L., Hong, O., Raymond, D.M. Effectiveness of a tailored intervention to increase factory workers’ use of hearing protection. Nursing Research. 2003;52(5):289–295.

Malloch, K., Porter-O’Grady, T. Introduction to evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Barlett, 2006.

Marshall, C., Rossman, G.B. Designing qualitative research, (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006.

McMurrey, P.H. Toward a unique knowledge base in nursing. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1982;14(1):12–15.

Melnyk, B.M., Fineout-Overholt, E. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Munhall, P.L. Nursing research: A qualitative perspective, (3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett, 2001.

Nightingale, F. Notes on nursing: What it is, and what it is not. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1859.

Nursing Executive Center. Evidence-based nursing practice: Instilling rigor into clinical practice. Washington, DC: The Advisor Board Company, 2005.

Omery, A., Kasper, C.E., Page, G.G. In search of nursing science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995.

Pearson, A., Field, J., Jordan, Z. Evidence-based clinical practice in nursing and health care: Assimilating research, experience, and expertise. Oxford: Blackwell, 2007.

Polanyi, M. Personal knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

Polanyi, M. The tacit dimension. New York: Doubleday, 1966.

Pronk, N.P., Goodman, M.J., O’Connor, P.J., Martinson, B.C. Relationship between modifiable health risks and short-term health care charges. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(23):2235–2239.

Rew, L., Barrow, E.M. Intuition: A neglected hallmark of nursing knowledge. Advances in Nursing Science. 1987;10(1):49–62.

Riley, J.M., Beal, J., Levi, P., McCausland, M.P. Revisioning nursing scholarship. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34(4):383–389.

Russell, B. Human knowledge, its scope and limits. Brooklyn, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1948.

Ryan, C.J., DeVon, H.A., Horne, R., King, K.B., Milner, K., Moser, D.K., et al. Symptom clusters in acute myocardial infarction: A secondary data analysis. Nursing Research. 2007;56(2):72–81.

Sackett, D.L., Straus, S.E., Richardson, W.S., Rosenberg, W., Haynes, R.B. Evidence-based medicine: How to practice & teach EBM, (2nd ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Salsberry, P.J., Reagan, P.B. Taking the long view: The prenatal environment and early adolescent overweight. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30(3):297–307.

Scheetz, L.J., Kolassa, J.E. Using crash scene variables to predict the need for trauma center care in older persons. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30(4):399–412.

Scheffler, I. Science and subjectivity. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967.

Selye, H. The stress of life. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976.

Sidani, S., Braden, C.P. Evaluating nursing interventions: A theory-driven approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998.

Silva, M.C. Philosophy, science, theory: Interrelationships and implications for nursing research. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1977;9(3):59–63.

Silva, M.C., Rothbart, D. An analysis of changing trends in philosophies of science on nursing theory development and testing. Advances in Nursing Science. 1984;6(2):1–13.

Toulmin, S. The philosophy of science. New York: Harper & Row, 1960.

Werley, H.H., Newcomb, B.J. The research mentor: A missing element in nursing? In: The nursing profession: A time to speak. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1983:202–215.

White, A.R. The nature of knowledge. Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Littlefield, 1982.