Malignant Tumors of Connective Tissue Origin

Fibrosarcoma

Fibrosarcoma is a tumor of mesenchymal cell origin that is composed of malignant fibroblasts in a collagenous background. It can occur as a soft tissue mass or as a primary or secondary bone tumor. The fibrosarcoma was once considered to be one of the most common of the malignant soft-tissue neoplasms. However, the gradual separation of other tumors from this group as our knowledge of fibrous lesions increased has in effect reduced the apparent frequency of the disease, so that nowadays fibrosarcoma, particularly of the head and neck area, is a quite uncommon neoplasm.

The sarcomas as a group differ from malignant epithelial neoplasms by their typical occurrence in relatively younger persons and their greater tendency to metastasize through the blood stream rather than the lymphatics, thereby producing more widespread foci of secondary tumor growth.

Two main types of fibrosarcoma of bone exist, primary and secondary. Primary fibrosarcoma is a fibroblastic malignancy that produces variable amounts of collagen. It is central, arising within the medullary canal, or peripheral, arising from the periosteum. Secondary fibrosarcoma of bone arises from a preexisting lesion or after radiotherapy to an area of bone or soft tissue. This is a more aggressive tumor with poorer prognosis.

Etiopathogenesis

Fibrosarcoma, like other soft tissue sarcomas, has no definite cause.

Several inherited syndromes like multiple neurofibromas may have a 10% risk over a lifetime of developing a neurosarcoma or fibrosarcoma.

Fibrosarcoma also has been noted to arise from preexisting lesions, such as fibrous dysplasia, chronic osteomyelitis, bone infarcts, Paget’s disease, and in previously irradiated areas of bone. These lesions are very aggressive and are associated with much poorer outcome than the primary fibrosarcoma of bone.

Clinical Features

Fibrosarcoma represents only about 10% of musculoskeletal sarcomas and less than 5% of all primary tumors of bone. No known racial predilection exists. Fibrosarcoma of bone occurs slightly more commonly in men than in women. Fibrosarcoma of bone is seen more commonly in patients of fourth decade of life and is usually in the lower extremities, especially the femur and the tibia. Fibrosarcoma of the soft tissues usually affects a wider age spectrum of patients than fibrosarcoma of the bone, with an age range of 35–55 years. It often arises in the soft tissues of the thigh and the posterior knee. It is generally a large painless mass deep to fascia and has an ill-defined margin.

An infantile form (in children <10 years) of fibrosarcoma exists. Unlike fibrosarcoma in adults, it has an excellent prognosis, even in the face of metastatic disease at presentation, when treated with a combination of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy and resection.

Sarcomas involving bone often present with pain and swelling after a long duration of symptoms. They may even grow large enough to threaten the structural integrity of the bone and cause pathologic fracture as the initial presentation. A prior history of bone infarct, irradiation, or other such risk factors should alert the physician to the possibility of a secondary fibrosarcoma.

Soft tissue sarcomas most often present as painless masses. The duration, however, is often shorter than with lesions involving bone. Because these lesions often arise deep in the muscular fascia, they may become extremely large tumors prior to diagnosis.

Differential diagnoses include fibrous dysplasia, fibrous histiocytoma, osteosarcoma, Paget’s sarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, malignant neurosarcoma.

Histologic Features

Fibrosarcomas are tumors of malignant fibroblasts. They vary in histologic grade.

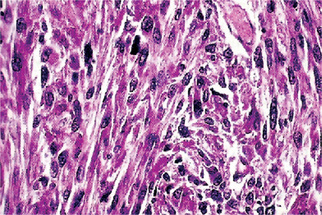

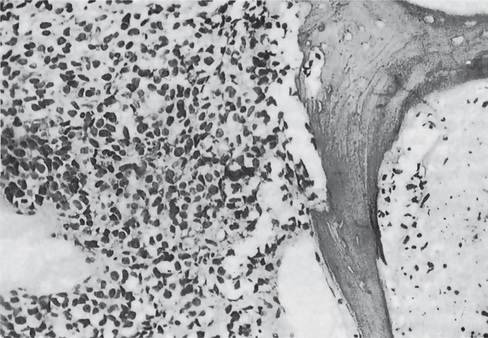

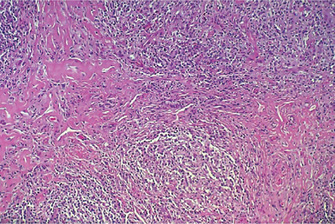

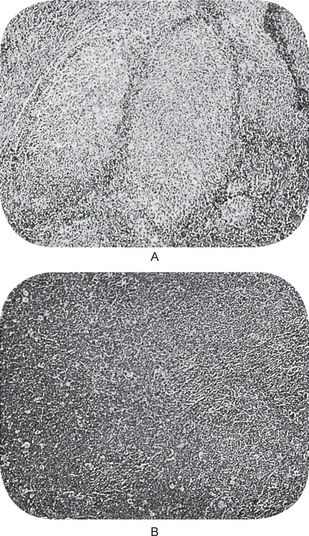

Well-differentiatedforms have multiple plump fibroblasts with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and deeply staining spindled nuclei with tapered ends. The malignant cells are dispersed in a rich collagen background. The lesion is typically scattered, histologically normal mitotic figures are seen in small numbers, but cells and nuclei are not pleomorphic (Fig. 2-66).

Figure 2-66 Low power appearance of well-differentiated fibrosarcoma. The tumor has a monotonous hypercellular look with regimentation of nuclei. Mitotic figures are common.

Intermediate gradetumors are cellular and have the typical herringbone pattern showing the diagnostic parallel sheets of cells arranged in intertwining whorls. Quite cellular with slight degree of cellular pleomorphism but moderate amounts of mature collagen may be produced, perhaps with areas of hyalinization (Fig. 2-67).

High-grade lesions are very cellular with marked cellular atypia and mitotic activity. The matrix is sparse. Multinucleated giant cells are rarely seen. No malignant osteoid formation should be present. Higher grades are extremely anaplastic and pleomorphic with bizarre nuclei that bring to mind the histologic features of malignant fibrous histiocytoma. In fact, some pathologists believe that the division between malignant fibrous histiocytoma, high-grade osteosarcoma, and fibrosarcoma may be artificial. Immunohistochemical studies reveal positivity for smooth muscle actin, desmin, S100 protein, and CD34

Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma is an uncommon tumor of deep soft tissues. Histologically, sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma composed predominantly of small to moderate size, round to ovoid, relatively uniform cells, often with clear cytoplasm, embedded in a hyalinized fibrous stroma. The only consistent immunohistochemical finding was a strong, diffuse reactivity of tumor cells for vimentin.

Treatment and Prognosis

Tumors require radical surgery, including removal of potentially invaded muscle and bone. The use of chemotherapy is controversial, but is generally used in bone lesions. Radiation therapy is used in conjunction with surgery for soft tissue fibrosarcomas, with or without additional chemotherapy. Fibrosarcoma seldom metastasizes except late in its clinical course, but when this does occur the metastatic deposits are usually blood-born and carried to distant sites, especially the lungs, liver and bones. Radiotherapy may be used as salvage for recurrences.

If all grades are included, primary fibrosarcoma of the bone has a worse prognosis than osteosarcoma, with a five-year survival rate of 65%. Specifically, in high-grade primary fibrosarcoma, the 10-year survival rate is less than 30%. Secondary fibrosarcoma is associated with a very poor outcome, with a less than 10% survival rate at 10 years.

Miscellaneous Locally Aggressive Fibrous Lesions

There is a sizable of locally aggressive but nonmetastasizing fibrous lesions which must always be differentiated type. In the past, many of these benign but locally aggressive lesions have been confused with sarcoma, and it is only in recent years that the pathologist has been able to separate these lesions with any assurance.

All of these lesions are quite uncommon in the oral cavity, and for this reason, no detailed description of them will be made here. This group consists chiefly of the following:

1. Nodular fasciitis (pseudosarcomatous fibromatosis)

2. Aggressive fibromatosis (extra abdominal desmoid)

4. Fibrous histiocytoma (fibroxanthoma)

Each of these lesions has been described in detail in the Atlas of Tumor Pathology Fascicle on Tumors of the Soft Tissues (AFIP) by Stout and Lattes and in the World Health Typing of Soft Tissue Tumors by Enzinger, Lattes and Torloni.

Definitions of each of the above lesions have been proposed in this WHO monograph and are reproduced as follows:

1 Nodular fasciitis

“A benign and probably reactive fibroblastic growth extending as a solitary nodule from the superficial fascia into the subcutaneous fat, or less frequently, into the subjacent muscle. Confusion with a sarcoma is possible because of its cellularity, its mitotic activity, its richly mucoid stroma, and its rapid growth. Other fibroblastic proliferations, such as proliferative myositis, are probably akin to this lesion. Nodular fasciitis is most common in the upper extremity, the trunk and the neck region of young adults.”

Nodular fasciitis of the head and neck has been described in detail by Werning, who reported 41 cases in this area and reviewed the pertinent literature. In his series, lesions occurred in every age group but were most common in the third through the fifth decade of life. These lesions developed most often within subcutaneous tissues overlying the mandible and zygoma, although intraoral lesions of buccal mucosa, tongue and alveolar mucosa also occurred. Since so many of the cases occurred in areas which serve as sites of origin or insertion of muscles of mastication and which are particularly vulnerable to trauma, Werning has emphasized that this lends support to the theory that nodular fasciitis is a pseudoneoplastic exuberant fibroblastic or myofibroblastic reactive process. These were usually firm, painless masses but, on occasion, there was pain, tenderness and a history of rapid growth. The treatment for this lesion is surgical excision and recurrence is rare.

2 Aggressive fibromatosis

“A nonmetastasizing tumor like fibroblastic growth of unknown pathogenesis involving voluntary muscle as well as aponeurotic and fascial structures.Histologically, it is indistinguishable from an abdominal fibromatosis. The lesion has a strong tendency to local recurrence and aggressive, infiltrating growth. It is most common in the shoulder girdle, the thigh, and the buttock of young adults.”

Aggressive fibromatosis of the oral or paraoral structures has been reported on occasion but it is quite uncommon in this location. Melrose and Abrams, reporting three cases involving the jaws of children, have discussed the protean nature of this group. For example, some are rapidly enlarging while others are of quite slow growth. Pain may or may not be present. When in apposition to bone, destruction of the bone occurs. The microscopic appearance of their lesions was quite uniform, however, consisting of cellular interlacing bundles of elongated fibroblasts showing no pleomorphism, little or no mitotic activity and no giant cells but typically with numerous slit-like vascular spaces not associated with inflammation. Treatment consists of complete surgical excision with generous margins of normal tissue. Recurrence is always a strong possibility and some workers recommend prolonged indefinite follow-up.

3 Proliferative myositis

“A rapidly growing, poorly circumscribed, probably reactive proliferation of fibroblasts and ganglion cell-like giant cells involving chiefly the connective tissue framework of striated muscle tissue. In contrast to myositis ossificans, a history of preceding trauma is infrequent and the lesion occurs chiefly in patients older than 45 years. The lesion is benign and should not be mistaken for a rhabdomyosarcoma or some other malignant neoplasm. Proliferative myositis has been discussed in Chapter 20 on Diseases of the Nerves and Muscles (q.v.).

4 Fibrous histiocytoma

“A benign, unencapsulated and often richly vascular growth made up of histiocytes and collagen-producing fibroblast-like cells, which are arranged in a whorled or cartwheel pattern. Frequently, the growth contains lipid-carrying macrophages. It may occur anywhere but is most common in the dermis.”

5 Atypical fibroxanthoma

“A probably benign growth, which is closely related to fibroxanthoma but shows a much greater degree of cellular pleomorphism with multinucleated giant cells and occasional giant cells of the Touton type as well as numerous mitotic figures, including atypical forms. The relatively small size of the lesion (generally less than 3 cm), its prevalence in the sun-damaged or irradiated skin of elderly individuals, and the fact that it is usually well-circumscribed, help in the difficult differential diagnosis from malignant fibroxanthoma. It probably does not occur in the oral cavity.

6 Desmoplastic fibroma of bone

This is a lesion of bone, including the jaws, which is histologically indistinguishable from aggressive fibromatosis or the extra abdominal desmoid. Although there is a wide spread in the age of occurrence, the vast majority of cases have occurred in the second decade. The lesion does not metastasize but often shows local recurrence. Wide local excision is, therefore, the treatment of choice.

The desmoplastic fibroma of the jaws has been reviewed by Freedman and his associates, who have analyzed and discussed 26 cases described in the literature. They found also that nearly all cases in this location occurred in the first three decades of life with the vast majority involving the mandible, particularly the molar-ramus-angle area. Swelling of the jaw was the common presenting complaint, pain or tenderness rarely being present. In a high percentage of cases, the lesions appeared as well-delineated radiolucencies, either unilocular or multilocular. The broadening of the microscopic parameters of this lesion was also emphasized by Freedman, who summarized the concept of the desmoplastic fibroma of bone as being composed of cells that may be either small and uniform, plump and uniform, or both in the same lesion, set in a variably collagenized stroma. The cells lack anaplastic forms or significant numbers of mitotic figures. Treatment of this lesion appears to be surgical excision or thorough curettage. Recurrence of jaw lesions has been uncommon.

Fibrous Histiocytoma

Fibrous histiocytoma represents a benign but diverse group of neoplasms which exhibit both fibroblastic and histiocytic differentiation. The cell of origin is believed to be the histiocyte, but the varied microscopic appearance of the lesion has led to the use of numerous alternative diagnostic terms, including dermatofibroma, sclerosing hemangioma, xanthogranuloma, fibroxanthoma, and nodular subepidermal fibrosis. A malignant variant of this neoplasm is discussed in the following section.

Clinical Features

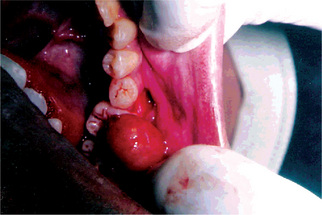

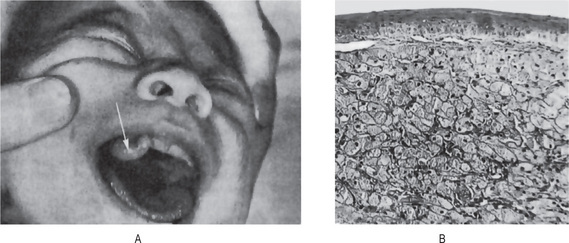

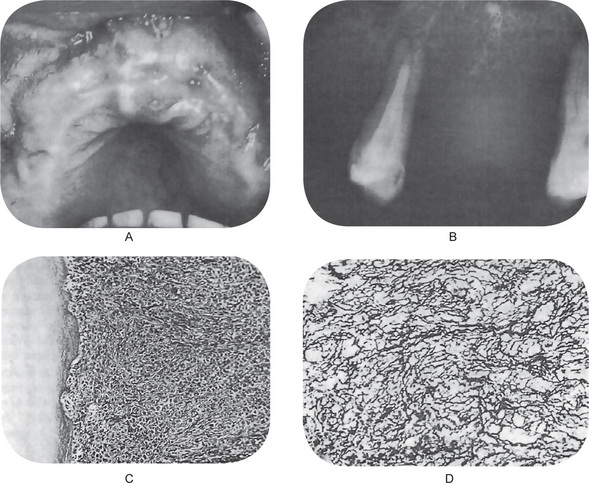

The most common site of occurrence is the skin of the extremities, where it usually presents as a small, firm nodule. Oral and perioral lesions are uncommon, but when seen they occur predominantly on the buccal mucosa and vestibule (Fig. 2-68). The oral lesion is typically found in middle-aged and older adults, where it presents as a painless submucosal nodule which can vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Deeper tumors tend to be larger and most lesions cannot be easily moved about beneath the epithelium.

Histological Features

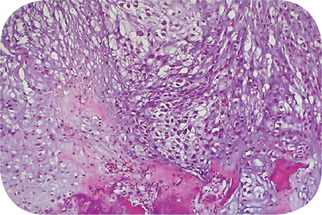

Fibrous histiocytoma is characterized by a submucosal, cellular aggregation of spindle-shaped, fibroblast like cells with relatively pale, oval nuclei; scattered rounded histiocytic cells are also present. Foamy histiocytes and Touton-type multinucleated giant cells, with nuclei pushed to the periphery, may be seen to contain phagocytosed lipid or hemosiderin; these cells sometimes are so numerous that they form xanthomatous aggregates. A background stroma of variably dense collagenous tissue and vascularity is seen. The spindled cells may be arranged randomly but usually there are large areas with tumor cells streaming in interlacing fascicles from a central nidus and intersecting with cells from adjacent aggregates, imparting a storiform or crisscross pattern on low power magnification.

The fibrous histiocytoma is poorly demarcated from surrounding tissues and is separated from the overlying mucosa by a zone of fibrovascular connective tissue (grenz zone). The overlying epithelium often demonstrates considerable acanthosis, with regular elongation of rete processes. Chronic inflammatory cells, especially lymphocytes, are usually scattered throughout the tumor in small numbers. The lesional stroma is occasionally very densely fibrotic or hyalinized, leading some in the past to use the diagnostic misnomer sclerosing hemangioma. Deeper lesions may contain focal areas of dystrophic calcification or metaplastic osteoid.

Benign fibrous histiocytoma is often confused with other benign fibrous lesions and must be differentiated from nodular fasciitis, myofibroma, palisading encapsulated neuroma, neurofibroma, leiomyoma and the spindle cell type of myoepithelioma. It is important, moreover, to separate this tumor from aggressive forms of fibrous and fibrohistiocytic neoplasms such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, malignant fibrous histiocytoma and fibrosarcoma.

Treatment and Prognosis

Benign fibrous histiocytoma is treated by wide surgical excision, with 5–10% of cases recurring locally. Deeper and larger lesions have a higher rate of recurrence. More aggressive examples usually show the microscopic features of dysplasia, such as marked cellularity, mitotic activity, focal necrosis, even atypical giant cells. It is sometimes, however, very difficult to predict biological behavior on the basis of cellular features alone. This warrants the need for extensive follow-up of cases.

Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) was first described in 1964 under the name malignant fibrous xanthoma. Since then several major variants have been identified and it has become the most commonly diagnosed of all the sarcomas of adults. Oral and maxillofacial sites are seldom involved, however, and the tumor occurs primarily in the soft tissues of the extremities and retroperitoneum.

Clinical Features

The MFH occurs primarily in adults, especially those 50–70 years of age, but rare cases have been described in children. Regardless of the histopathologic subtype, men are affected almost twice as frequently as women.

Within the maxillofacial region the most common complaint is a moderately firm submucosal mass expanding slowly or moderately fast, with or without pain and surface ulceration. The irregular nodular lesion is typically unencapsulated and attached to surrounding tissues and adjacent structures. Itis usually less than 4 cm in greatest diameter at the time of biopsy. The myxoid variant often has a soft consistency and the angiomatoid variant is often found in a location more superficial than that of the other variants.

Histologic Features

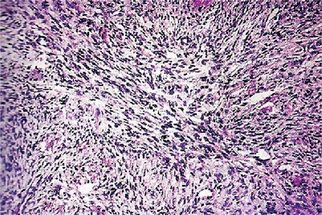

MFH has a wide spectrum of cellular and tissue alterations. The cellular differentiation and density vary markedly, even within the same tumor. The classic histopathologic features, however, include at least mild cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, an admixture of fibroblastic and histiocytic elements, and focal areas with a storiform or cartwheel pattern of streaming spindle cells. This classic pattern is the one most frequently encountered in head and neck sites and is often referred to as the storiform-pleomorphic MFH.

Most lesional cells are spindled fibroblast like cells which tend to be arranged in short woven fascicles or bundles. The spindle cells may be long and thin with minimal atypia, but there are usually areas with plump cells containing enlarged, hyperchromatic and irregular nuclei. Varying numbers of rounded, polygonal and irregularly shaped histiocyte like cells may dominate some areas of the lesion, often with very pleomorphic, multinucleated giant cells interspersed. The histiocytic cells have either abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm or pale foamy cytoplasm, and cell membranes are not easily visualized. Areas with histiocytic predominance usually have a haphazard structural appearance.

Chronic inflammatory cells are often scattered sparsely throughout the tumor, including foamy histiocytes, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Mitotic activity varies widely and is directly related to the degree of cellular pleomorphism.

The fibrous stroma of MFH varies in density, being less pronounced in areas of lesser cellular differentiation. Myxoid stroma may be found, and rarely, foci of osteoid or cartilage metaplasia are present. While blood vessels are usually inconspicuous, some lesions present with numerous dilated, branching vessels. Depending on the dominant morphology, MFH is currently subclassified as one of several major variants: pleomorphic-storiform, myxoid, angiomatoid (aneurysmal), and giant cell MFH.

Synovial Sarcoma

Synovial sarcoma comprises 8–10% of all sarcomas and most commonly affects adults in the third-to-fifth decades of life. The malignancy most commonly involves the extremities, especially the lower extremities around the knees. Synovial sarcoma frequently is misdiagnosed as benign often because of its small size, slow growth, and well-defined appearance.

Etiopathogenesis

Synovial sarcoma is so named because of its resemblance to developing synovial tissue under light microscope. It arises from pluripotential mesenchymal cells I near joint surfaces, tendons, tendon sheaths, juxta-articular SECTION membranes, and fascial aponeuroses.

Clinical Features

Synovial sarcoma can occur in patients with a wide age range, but it is most common in patients in the third-to-fifth decades of life. In one series of 121 cases, 83.6% of tumors occurred in patients aged 10–50 years, with a median age of 31.3 years (Lewis JJ et al, 2000). A slight male predilection is seen with the male-to-female ratio of 3 : 2. The region around the knee is the most common site of involvement. In head and neck area this tumor is very rare. Other head and neck locations include the cervical or parapharyngeal regions, masticator space, soft palate, tongue, suboccipital and infratemporal fossa regions, and sinonasal space. Most synovial sarcomas are found within 5 cm of a joint; only 10% of cases are intraarticular.

The clinical features of synovial sarcoma are nonspecific. No features to distinguish synovial sarcoma from other sarcomas. Most commonly, patients notice a slowly enlarging, deep-seated mass, which is painful in slightly more than one half of patients. In head and neck involvement, patients complain of symptoms such as dyspnea, dysphagia, hoarseness, and headache.

Radiographic Features

Plain radiograph may aid in the di-agnosis as synovial sarcoma typically produces spotty calcification (snowstorm) within the matrix of the soft-tissue tumor. CT scan or MRI is used to confirm the presence of a mass, its size, and its location.

Histologic Features

Gross specimens are usually well-demarcated, pink, fleshy masses with a heterogeneous appearance, and specimens may display solid, hemorrhagic, or cystic components on sectioning. Calcification foci are occasionally noted. Heavy calcification tends to indicate less aggressive lesions and offers a more favorable prognosis.

Typical morphology is that of two strikingly distinct well-differentiated cell populations. Depending on which cell type predominates, overall histologic appearances can be described as biphasic (epithelioid and spindle cell), monophasic spindle cell, or monophasic epithelioid. Marked cellular pleomorphism and atypia are uncommon, and when present, the appearance overlaps with that of high-grade malignant fibrous histiocytoma and fibrosarcoma.

The histologic appearance is that of large polygonal cells (epithelioid) which show an organization suggestive of microscopic joint spaces (cleft like or slit like spaces lined by cuboidal epithelial-like cells). The spaces may contain a PAS-positive mucoid material. These cells are surrounded by spindle cells that simulate subsynovial mesenchymal cells. Punctate areas of calcification may be observed. The second pattern is comprised of a fibrosarcoma like proliferation of cells with associated collagen and reticulin. A monophasic pattern without the slit like spaces exists but is very uncommon.

Treatment

The treatment is wide resection with negative margins, which often include surrounding muscle groups or total amputation. Resection is commonly followed by localized irradiation. Synovial sarcomas have been shown to be markedly chemosensitive, multidrug adjuvant chemotherapy is currently recommended for systemic control of the tumor. The prognosis of head and neck synovial sarcoma is better than that of sarcoma involving the extremities, with five-year survival rates of 47–82%.

Liposarcoma

Liposarcoma is a malignancy of fat cells. Virchow first described liposarcoma in the 1860s.

The most recent World Health Organization classification of soft-tissue tumors recognizes five categories of liposarcomas:

In rare circumstances, lesions can have a combination of morphologic types; these are classified as combined or mixed-type liposarcomas.

Etiopathogenesis

No well-established causative factor has been identified, although trauma has been implicated. The development of a liposarcoma from a preexisting benign lipoma is rare. Most cases arise de novo. Liposarcomas most frequently arise from the deep-seated connective tissue stroma rather than the submucosal or subcutaneous fat.

Clinical Features

Liposarcoma is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma, accounting for approximately 17% of all soft-tissue sarcomas with an annual incidence of 2.5 cases per million population, and 3% of all liposarcomas occur in the head and neck region.

Although there is a wide range, from children to the very elderly, the liposarcoma of the head and neck region occurs most frequently in adults. Liposarcomas are slightly more common in males than in females. No association with race or geography is known. Oral involvement is rare; a fewer than 50 oral cases has been reported.The most commonly affected site was the tongue; other sites are the submandibular area, cheek, tongue, floor of mouth and soft palate. Most cases present as a slowly growing, painless, nonulcerated submucosal mass. But some lesions grow rapidly and become ulcerated early. The clinical impression seems to be lipoma or fibroma in the majority of cases. Tumor size ranged from 0.6–8.0 cm.

Histologic Features

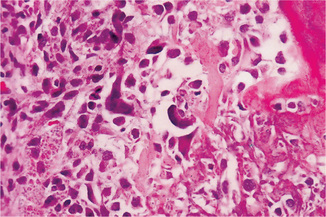

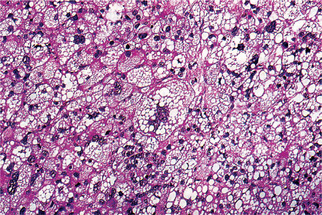

The recognition of lipoblasts is the key finding in the diagnosis of liposarcoma. A lipoblast has the ability to produce and accumulate nonmembrane-bound lipidwithin its cytoplasm (Fig. 2-69).

Figure 2-69 Liposarcoma. Numerous tumor giant cells and malignant cells showing features of lipoblasts (Courtesy of Dr Juan Rosai).

Well-differentiated liposarcomas usually contain a predominance of mature fat cells with relatively few, widely scattered lipoblasts. A misdiagnosis of lipoma can result from inadequate sampling. In the sclerosing subtype of a well-differentiated liposarcoma, collagen fibrils that encircle fat cells and lipoblasts make up a prominent part of the matrix.

Myxoid liposarcoma, the most common type, is diagnosedby the observation of a delicate plexiform (chicken wire)pattern of capillary network that is associated with both primitive mesenchyme-like cells (spindle cells) and a variable number of lipoblasts. The stroma contains a large proportion of myxoid ground substance (i.e. hyaluronic acid), in which numerous microcysts may form.

In the round-cell type, lipoblasts with very little lipid are interspersed among sheets of poorly differentiated round cells. The round cells have a small to moderate amount of finely vacuolated or granular cytoplasm and may appear epithelioid or pericytoid.

Poorly differentiated pleomorphic liposarcoma is recognized by an extreme cellularity, mixture of bizarre, often multivacuolated lipoblasts and atypical stromal cells, many of which contain highly abnormal mitotic figures including bizarre giant cells. Lesional cells may be polygonal or stellate with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and poorly-demarcated cell boundaries. Hemorrhagic and necrotic areas are common. The characteristic lipoblast distinguishes pleomorphic liposarcoma from malignant fibrous histiocytosis (MFH). The round-cell and pleomorphic types are the high-grade liposarcomas.

However, it has been noted by Baden and Newman that the majority of liposarcomas of the head and neck area were myxoid liposarcomas and that the majority of these were well-differentiated neoplasms.

Stains for lipids are often useful in the diagnosis of liposarcoma, but this material may be scarce and is sometimes produced by unrelated mesenchymal and epithelial neoplasms. The mucinous matrix, when present, will stain with alcian blue and is metachromatic with toluidine blue and cresyl violet stains; it is weakly positive with Meyer’s mucicarmine stain. Intracellular glycogen (diastase-sensitive, PAS positive) may be seen in some lesional cells. Adipocytes and lipoblasts react positively for vimentin and S100 protein immunostains, but these vary in intensity and may not be expressed in poorly differentiated lesions.

Hemangioendothelioma

Hemangioendothelioma is a varied group of proliferative and neoplastic vascular lesions, which have a biological behavior that falls somewhere between the benign hemangioma and malignant angiosarcoma. Approximately 10% of cases are associated with other developmental anomalies or syndromes, including early onset varicose veins, lymphedema, Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome, and Maffucci’s syndrome.

Chromosomal translocation involving chromosomes 1 and 3 [t(1;3)(p36.3;q25)] was detected in few cases of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

Clinical Features

The tumor is usually seen during the second and third decades of life and there is no gender predilection. This neoplasm may occur anywhere in the body, but is most commonly found in the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Primary lesions of the oral cavity, though not common, have been reported in a variety of locations, including the lips, palate, gingiva, tongue and centrally within the maxilla and mandible. The literature pertaining to malignant hemangioendotheliomas of the oral cavity was reviewed by Wesley and his associates and Zachariades and his coworkers, who tabulated 46 reported oral cases.

The hemangioendothelioma arises at any age and has been found present even at birth. Females appear to be affected almost twice as often as males. Localized swelling may be the primary manifestation of the lesion, although pain is occasionally present as well.

The malignant hemangioendothelioma is similar to the hemangioma in appearance and is usually manifested clinically as a flat or slightly raised lesion of varying size, dark red or bluish red, sometimes ulcerated and showing a tendency to bleed after even slight trauma. Bone may be involved by the tumor, producing a destructive process.

Histologic Features

The hemangioendothelioma is a poorly circumscribed, usually biphasic proliferation of venous or capillary vessels. There are dilated and congested veins with inactive endothelial cell nuclei and with occasional thrombi or phleboliths. These vessels are intermixed with solid sheets of epithelioid (epithelioid hemangioendothelioma) or spindle-shaped (spindle cell hemangioendothelioma) mesenchymal cells with minimal dysplasia, few mitotic figures, and minimal differentiation toward a vascular lumen or channel.

The epithelioid cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, may contain vacuoles (primitive lumina), and may be admixed with smooth muscle bundles. These cells stain positively with Ulex europaeus and many will show cytoplasmic factor VIII-associated antigen reactivity with immunohistochemistry. Tumor cells also stain for endothelial markers such as CD31 and CD34 in approximately one-fifth of cases.

The lesional cells of the spindle cell hemangioendothelioma are rather bland, bipolar mesenchymal fibroblast like cells which may contain vacuoles, presumed to be abortive or primitive vascular lumina. Epithelioid cells are usually seen in small numbers in scattered areas and the associated dilated venous channels are more prone to contain thrombi and phleboliths than are those of the epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, histopathologically an admixture of tissues similar to both capillary hemangioma and Kaposi’s sarcoma, has been reported from an oral or pharyngeal location (Zukerberg LR et al, 1993). Uniform spindle cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and elongated nuclei associated with slit like vascular channels, similar to those of Kaposi’s sarcoma, with mild extravasation of erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition within or outside of macrophages. Mitotic figures and atypia are rare.

Polymorphous hemangioendothelioma consists of mixture of solid and primitive vascular and angiomatous endothelial areas.

The pathologist must be careful to rule out metastatic carcinoma or melanoma, which typically display much more dysplasia than hemangioendothelioma. The various epithelioid sarcomas must also be ruled out, especially the epithelioid angiosarcoma.

Hemangiopericytoma

Stout and Murray in 1942 were the first to suggest hemangiopericytoma as a distinctly different vascular neoplasm. Stout also was the first to report an oral hemangiopericytoma, just a few years after its initial reporting. It is a neoplasm which is usually benign but has a definite malignant counterpart.

Head and neck lesions represent 16–25% of all reported hemangiopericytomas, and the tumor represents 2–3% of all soft tissue sarcomas in humans. Chromosomal translocations t(12;19) and t(13;22) have been observed in lesional cells.

Clinical Features

The oral hemangiopericytoma is typically a rapidly enlarging red or bluish mass which arises in all age groups but is rare prior to the second decade or after the seventh decade. There is no gender predilection. It is soft or rubbery, is usually painless and is relatively well demarcated from the surrounding mucosa. The lesion may be sessile or somewhat pedunculated, and may demonstrate a surface lobularity or telangiectasia. Intraosseous examples have been reported.

The oral/pharyngeal mucosa is, additionally, one of the most common locations for the rarely reported infantile hemangiopericytoma. This lesion is usually multiple and congenital, and often demonstrates an alarmingly rapid rate of enlargement after birth. Although this entity tends to recur after surgical excision, there is no potential for metastasis.

Histologic Features

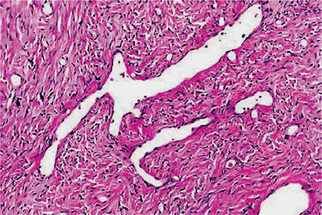

On gross examination, hemangioperi-cytomas may be well circumscribed and appear grayish white. The appearance is much less hemorrhagic than endothelial tu-mors. The consistency is variable and may be solid or spongy, friable or granular (Fig. 2-70).

Hemangiopericytoma is a tumor thought to be derived from pericytes. Hemangiopericytoma consists of numerous vascular channels with plump endothelial nuclei and a surrounding, tightly packed proliferation of oval and spindled cells, hyerchromatic nuclei and a moderate amount of cytoplasm. The cells have indistinct cytoplasmic borders. The tumor cells do not arise from endothelial cells even though they surround irregular vascular spaces. The branching vascular channels of varying sizes is often described as a ‘staghorn’ pattern (Fig. 2-71). Older, less aggressive lesions tend to have less cellularity and may have a largely mucoid interstitial appearance, which can be mistaken for myxoid lipoma or myxoid liposarcoma. Focal cartilage production may rarely be seen and such lesions must be differentiated from mesenchymal chondrosarcoma.

Figure 2-71 Dilated, thin-walled vessels as shown here are common. These vessels simulate ‘staghorns’ that are often associated with hemangioperi-cytoma.

Reticulin staining will demonstrate lesional vessels lined by a single layer of endothelial cells, with the pericytes lying outside the basal lamina. Lesional cells are immunoreactive for vimentin (variable intensity), factor XIIIa antigen, HLA-DR antigen and QBEND10 (CD34). They do not stain for or react with factor VIII-related antigen, Ulex europaeus I lectin, alpha-smooth muscle actin, desmin, myoglobin, low-molecular weight cytokeratin, high-molecular weight cytokeratin, or epithelial membrane antigen.

The differential diagnosis of this lesion includes, in addition to the tumors named above, fibrous histiocytoma, MFH, synovial sarcoma, other stromal sarcomas, vascular leiomyoma, and juvenile hemangioma.

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of hemangio-pericytoma is dependent on the amount of cellular dysplasia and mitotic activity. The more bland lesions with minimal mi-totic activity are treated by wide local excision, but the more active and dysplastic lesions are treated by radical surgical excision, with or without adjunctive radiotherapy.

Multiple Idiopathic Hemorrhagic Sarcoma of Kaposi (Kaposi's sarcoma, angioreticuloendothelioma)

Kaposi’s sarcoma is a multicentric proliferation of vascular and spindle cell components, which was first described in 1872 by Moritz Kaposi, a Hungarian dermatologist, who described skin tumors in five men in their sixth and seventh decades of life as ‘idiopathic multiple pigmented sarcoma of the skin’. Now considered to be a viral-induced or viral-associated tumor, it is unclear whether the lesion is a true neoplasm or a simple hyperplasia. This tumour is currently incriminated with HIV/AIDS and its clinical stage depends greatly on the immune status of the patient. Although found predominantly in HIV-infected persons, HIV does not seem to be the direct cause of the tumorous proliferation and HIV amino acid sequences have not been identified within lesional cells.

Clinical Features

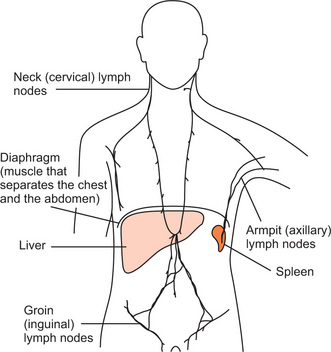

Kaposi’s sarcoma has four major clinical presentations: classic (chronic), endemic (lymph-adenopathic; African), immunosuppression-associated (transplant), and AIDS-related.

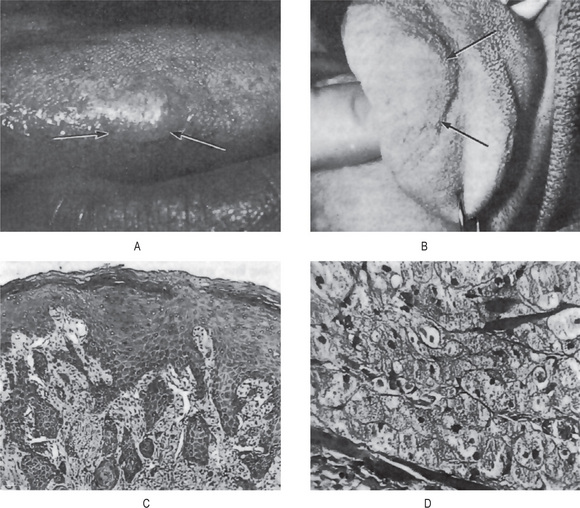

The classic variant is often associated with altered immune states as well as lymphoreticular and other malignancies. Cutaneous multifocal blue-red nodules develop on the lower extremities and slowly increase in size and numbers, with some lesions regressing while new ones are forming on adjacent or distant skin. Oral involvement in this form of the disease is quite unusual but when it occurs it does so as soft, bluish nodules of the palatal mucosa or gingiva.

Lymphadenopathic Kaposi’s sarcoma is endemic to young African children and presents as a localized or generalized enlargement of lymph node chains, including the cervical nodes. The disease follows a fulminant course with visceral involvement and minimal skin or mucous membrane involvement. In the head and neck region, salivary glands may be affected. This variant does not appear to be HIV related.

Transplantation-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma is seen in 1–4% of renal transplant patients, usually becoming manifested one or two years after transplantation. The extent and progression of the disease correlates directly with the loss of cellular immunity of the host. Sarcomatous involvement occurs on the skin as well as internal organs, but oral mucosal lesions are decidedly rare.

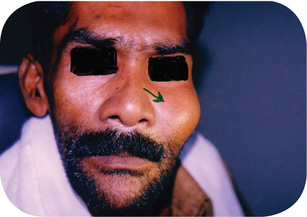

AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Approximately 40% of homosexual AIDS patients will develop Kaposi’s sarcoma, often as an early sign of the disease. Affected patients are usually young adults or early middle-aged males, with the average age at diagnosis being 39 years in the US. Individual lesions occur in many cutaneous locations, especially along lines of cleavage and on the tip of the nose. Oral lesions can also occur on any mucosal surface but have a strong predilection for palatal and gingival mucosa.

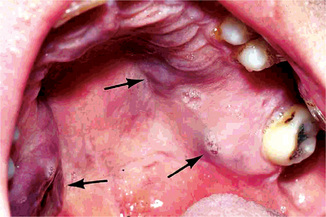

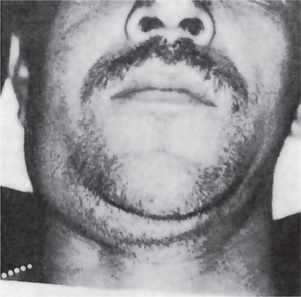

Early oral mucosal sarcomas are flat and slightly blue, red or purple plaques, either focal or diffuse, may be completely asymptomatic and easily overlooked. With time, lesions become more deeply discolored and surface papules and soft nodules develop, or may become exophytic and ulcerated, and may bleed, usually remaining less than 2 cm in size (Fig. 2-72). Individual lesions may coalesce and occasional patients never develop the nodular variant. Cervical lymph nodes and salivary gland enlargement may also be seen. The patient may have oral candidiasis and AIDS-related gingivitis as well. Other oral sites of KS involvement include the gingiva, tongue, uvula, tonsils, pharynx, and trachea. These lesions may interfere with mastication phonation and cause tooth loss and airway obstruction (eating and speaking, cause tooth loss, or compromise the airways).

Histologic Features

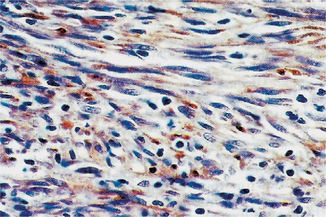

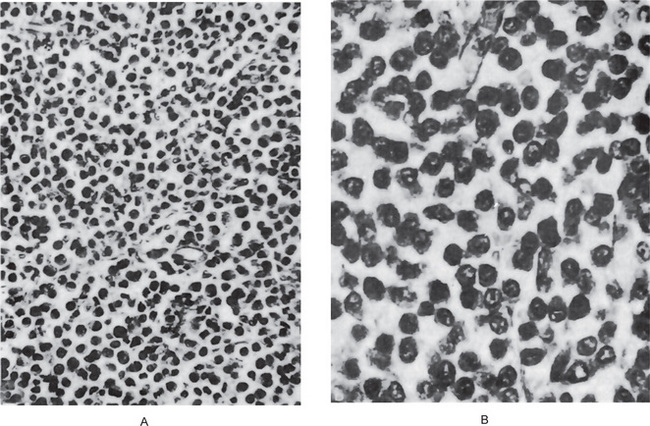

Kaposi’s sarcoma has a similar histopathologic appearance in all of its clinical subtypes. The early lesion (patch stage) is characterized by proliferation of small veins and capillaries around one or more preexisting dilated vessels. The slit like vessels are present around preexisting blood vessel, skin adnexa and between collagen fibers. Vessels are lined by plump, mildly atypical endothelial cells. The features resemble granulation tissue. A pronounced mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate, including mast cells, scattered erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposits may be present. There may be an inconspicuous perivascular proliferation of spindle cells, but cellular atypia is minimal.

More advanced lesions (plaque stage) are nodular and show increased numbers of small capillaries or dilated vascular channels interspersed with proliferating sheets of sarcomatous or atypical spindle cells, often with large numbers of extravasated erythrocytes and abundant hemosiderin deposition. Slit like vascular channels without a visible endothelial lining are typically interspersed with the spindle cells. Lesional cells have somewhat enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with mild to moderate pleomorphism. Mitotic activity is quite variable but is usually minimal. Infiltration by chronic inflammatory cells is also variable. In the nodular stage, all the histologic features are more prominent than plaque stage.

Treatment and Prognosis

Various treatments have been used in oral Kaposi’s sarcoma with variable success. Small or localized lesions can be surgically excised with a small surrounding margin of clinically normal tissue, but more recent therapies have concentrated on low-dose irradiation and intralesional chemotherapy and sclerosing solutions. For larger and multifocal lesions, systemic chemotherapy is often effective.

Ewing’s Sarcoma (Endothelial myeloma, ‘round cell’ sarcoma)

Ewing’s sarcoma is a sarcoma of the bone, classically described under small round cell tumors. There is considerable clinical and histologic overlap between this tumor and the primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET). Now with sophisticated molecular biological analysis, it turns out that both tumors share a common and unique chromosomal translocation. Most investigators now believe that Ewing’s sarcoma and PNET are different morphological expressions of one tumor type. In general, Ewing’s sarcoma arises within the bone while PNET arises within soft tissues. However, there are overlap cases of Ewing’s sarcoma arising within soft tissue (extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma) and PNET arising within the bone. Under the microscope, the tumors share a considerable homology though there are usually more neuroendocrine features with PNET. Ewing’s sarcoma is thought to be a more undifferentiated tumor. Though data is conflicting, some investigators believe Ewing’s sarcoma to have a slightly better prognosis.

A practical working definition is to consider all highly malignant, small round-to-oval cell sarcomas with the clinical and radiographic characteristics of a primary osseous lesion to be Ewing’s tumor (Unni KK, 1996). Inherent in this concept is the exclusion of cytologically incompatible lesions such as myeloma, malignant lymphoma, and histiocytosis X. Production of a chondroid or osteoid matrix by the neoplastic cells likewise excludes Ewing’s sarcoma. Similarly, true spindling of the nuclei is incompatible with the diagnosis of Ewing’s sarcoma. It is sometimes impossible to differentiate a biopsy specimen of a metastatic malignant tumor such as neuroblastoma, small cell carcinoma of the lung, or even a leukemic infiltrate from a specimen of Ewing’s tumor, even after critical histologic study according to modern concept. Immunoperoxidase stains, however, can effectively rule out metastatic carcinomas and lymphomas and leukemias.

Clinical Features

This neoplastic disease occurs predominantly in children and young adults between the ages of five and 25 years, the median age of occurrence is 13 years, 80% occur within first two decades of life, but is seen on occasion in older patients also. In the series of 107 cases reported by Bhansali and Desai, six patients were over the age of 40 years, the oldest being an 83-year-old woman. Thus it arises in the same general age group in which osteogenic sarcoma is most prevalent. It is approximately twice as common in males as in females, and uncommon in blacks.

It is noteworthy that an episode of trauma often precedes the development of the tumor, although it must not be inferred that this is in any manner important in the etiology of the neoplasm.

Pain, usually of an intermittent nature, and swelling of the involved bone are often the earliest clinical signs and symptoms of Ewing’s sarcoma. The bones most commonly affected are the long bones of the extremities, although the skull, clavicle, ribs and shoulder and pelvic girdles may be involved, as well as the maxilla and mandible. The jaws were involved in 13% of a series of 126 cases reported by Geschickter and Copeland. Nine additional cases, eight in the mandible and one in the maxilla, have been reported by Potdar.

Facial neuralgia and lip paresthesia have been reported in cases of jaw involvement. The appearance of the jaw swelling is often a relatively rapid one, and the intraoral mass may become ulcerated. The patient may have a low-grade fever and an elevated white blood cell count, and these findings have often given rise to an erroneous tentative diagnosis of an infection.

An extraskeletal form of this tumor has been described by Angervall and Enzinger and termed Ewing’s sarcoma of soft tissues. The ultrastructural characteristics of the cells constituting this tumor, studied by Gillespie and his associates, among others, are identical to those of the typical Ewing’s cells.

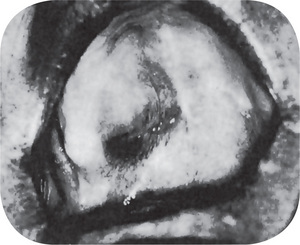

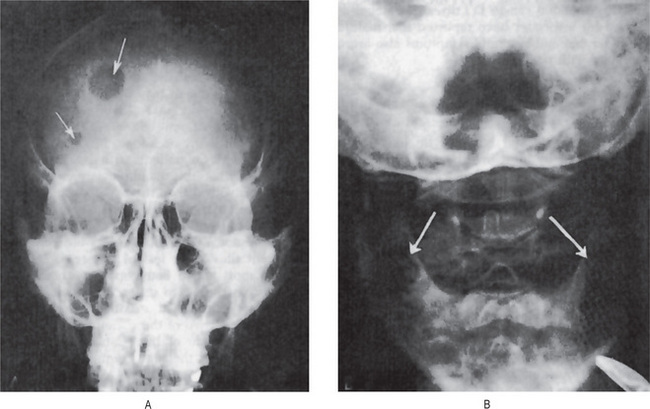

Radiographic Features

The radiographic appearance of Ew-ing’s sarcoma has been described as being suggestive but not pathognomonic of the disease. The lesion is a destructive one and produces an irregular, diffuse radiolucency, although lesions of the jaw resembling sclerosing osteomyelitis have been described.

A common characteristic radiographic feature is the formation of layers of new subperiosteal bone producing the so-called ‘onion skin’ appearance on the film. This thickened cortex is usually infiltrated by tumor. Osteophyte formation may also be visible on the radiograph and, in such cases, may be similar to the ‘sun-ray’ appearance of osteosarcoma.

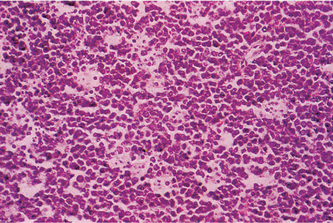

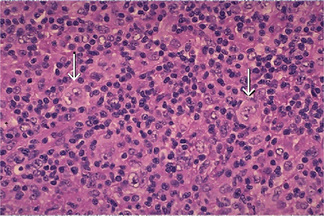

Histologic Features

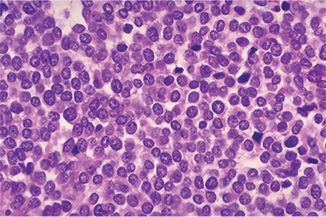

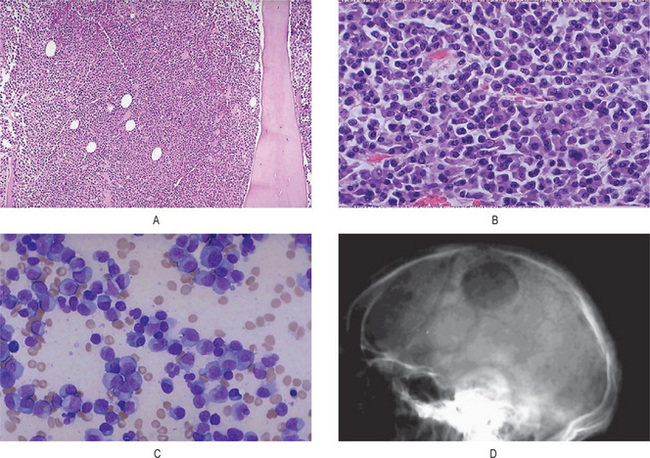

Ewing’s sarcoma is an extremely cellular neoplasm composed of solid sheets or masses of small round cells with very little stroma, although a few connective tissue septa may be present (Fig. 2-74). The cells themselves are small and round, with scanty cytoplasm and relatively large round or ovoid nuclei with dispersed chromatin and hyperchromasia. The cell borders are indistinct. The sarcoma cells are arranged in Filigree pattern. Mitotic figures are common. The cells are positive for glycogen and are diastase resistant. The importance of intracytoplasmic glycogen in the diagnosis of Ewing’s sarcoma has been reaffirmed by Telles and his coworkers 1978, who also emphasized that therapy did not alter the presence of this glycogen. Rosettes present in 10% of cases. Many tiny vascular channels may also be present. Hemorrhage with vascular lakes or sinuses may be seen. Geographic necrosis with perivascular sparing is a common feature. However, as Telles and his associates pointed out in an autopsy study of 26 cases of Ewing’s sarcoma, increased cellular pleomorphism and increased numbers of bizarre giant cells may be found in the lesions in patients treated with radiation and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Figure 2-74 Ewing’s sarcoma. Ewing’s sarcoma is one of the ‘small round blue cell’ tumors histologically. Note the many mitotic figures in the field.

Encroachment of tumor cells on a bone trabecula causing its ragged resorption is apparent. Necrosis is also present on the opposite side of the fragment of bone (Fig. 2-75).

The cells of Ewing’s sarcoma can generally be differentiated from reticulum cell sarcoma with little difficulty. In some cases of Ewing’s sarcoma, however, the cells are larger and may simulate the malignant lymphoma. Schajowicz has reported that tumor cells of Ewing’s sarcoma contain histochemically demonstrable glycogen, which is absent in cells of the reticulum cell sarcoma, thus providing an easy method of differentiation. Other tumors which have to be differentiated from Ewing’s sarcoma are small cell osteosarcoma, PNET (peripheral neuroectodermal tumor of infancy), metastatic neuroblastoma, mesenchymal chondrosarcoma.

Characteristic translocation is seen with Ewing’s sarcoma of the bone. The fusion gene is designated as EWS/FLI-1(t(11;22)(q24q12)). Monoclonal antibodies to the fusion gene protein product are termed CD99.

Treatment and Prognosis

This neoplasm is radiosensitive, but unfortunately, in the past, has seldom been cured by X-ray radiation. Radical surgical excision has been done, alone and coupled with X-ray radiation, but it has been common for metastatic foci to appear in other bones and organs, such as lungs and lymph nodes, within a matter of a few weeks or months. Five-year survival with a combination of surgery and chemotherapy is 74%.

Chondrosarcoma

The chondrosarcoma is the malignant counterpart of the chondroma, and like the benign lesion, may occur in either the maxilla or the mandible, as well as in many other bones in the body.

The exact origin of chondrosarcoma is obscure, but the salient pathologic fact is that its basic proliferating tissue is cartilage throughout. Large portions of these tumors may become myxomatous, calcified or even ossified. Sometimes at the periphery of the lobules of a high-grade chondrosacroma, a few fibrosarcoma like spindled tumor cells occur. Osseous trabeculae, when present, are seen at the periphery of the lobules and appeared to be rimmed with osteobalsts, however, when the malignant cells produce an osteoid lacework or osteoid trabeculae directly, even in small foci, the neoplasm has clinical characteristics of osteosarcoma and belongs in that category (Unni KK, 1996).

Chondrosarcoma usually has a slow clinical evolution. Metastasis is relatively rare and often occurs late. Chondro-sarcomas can arise de novo (primary chondrosarcoma) in extraskeletal tissues or in teratomas and other mixed tumors. Chondrosarcomas composed of hyaline cartilage are extremely rare in the somatic soft tissues; most of the lesions are myxoid chondrosarcomas. Their general characteristics are similar to those of the skeletal examples.

Secondary chondrosarcomas arise most commonly in osteochondromas (osteocartilaginous exostoses), especially in the mutiple familial type. The primary and secondary chondrosarcomas may, on occasion, give rise to more highly malignant tumors—osteosarcomas, fibrosarcomas, or malignant fibrous histiocytomas—and these are called dedifferentiated chondrosarcomas.

Clinical Features

There are no pathognomonic signs or symptoms presented by the chondrosarcoma, nor may it be differentiated from the chondroma purely on the basis of the clinical findings. The tumor can occur at any age between 10 and 80 years. However, in the series of 288 cases reported by Henderson and Dahlin, the peak incidence was between 30 and 60 years, while in the series of 151 cases of McKenna and his associates, it was between 30 and 50 years. The secondary chondrosarcoma occurs at an earlier age than the primary chondrosarcoma, by an average of about 10 years. In general, chondrosarcomas occur more often in males, in a ratio of about 2 to 1. The presentation of chondrosarcoma depends on the grade of the tumor. A high-grade, fast growing tumor can present with excruciating pain. A low grade, more indolent tumor is likely to be present in an older patient complaining of pain and swelling. Chondrosarcoma usually has a slow clinical evolution. Metastasis is relatively rare and often occurs late.

Rare variants with distinctive microscopic and clinical features are discerned: clear cell chondrosarcoma (1%), mesenchymal chondrosarcoma (2%), juxtacortical chondrosarcoma (2%), extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (5%) and dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma (Table 2-14).

Table 2-14

Chondrosarcoma of bone and variants

Conventional chondrosarcoma

Borderline

Low grade

High grade

Secondary chondrosarcoma (originate from preexisting benign tumor)

Solitary exostoses

Multiple exostoses

Multiple chondromas

Synovial chondromatosis

Post radiation

Fibrous dysplasia

Peripheral chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma of upper respiratory (excluding larynx)

Clear cell chondrosarcoma

Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma of small bones

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is a characteristic and distinctive type of chondrosarcoma in which the majority of cases occur between the ages of 10 and 30 years, and in which there is an approximately equal gender distribution. In addition, the most common sites of origin are the jaws and ribs, according to Salvador and his associates.

Clear cell chondrosarcoma is a recognized variant of the usual chondrosarcoma from which it should be separated because of its slow growth pattern and its favorable clinical course with low metastatic potential and high probability of cure. Without radical excision, however, death can result. It may occur in the jaws, and such a case has been reported by Slootweg.

Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma is the most malignant form of chondrosarcoma. This tumor is a mix of low grade chondrosarcoma and high grade spindle cell sarcoma where the spindle cells are no longer identifiable as having a cartilage origin. The dedifferentiated portion of the lesion may have histological features of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, osteosarcoma, or undifferentiated sarcoma. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma has a five-year survival of 10%.

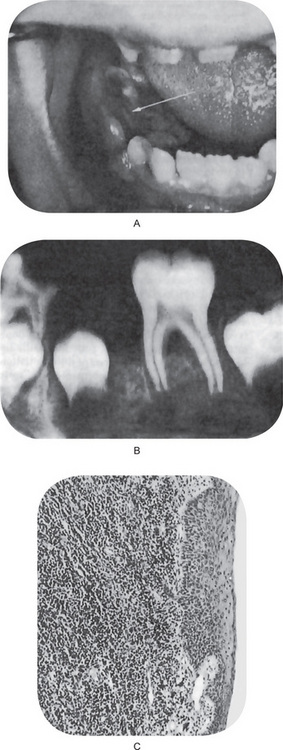

Oral Manifestations

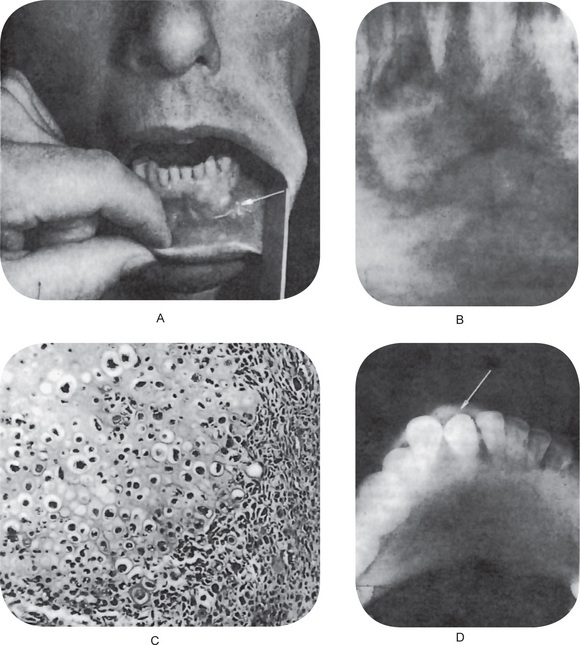

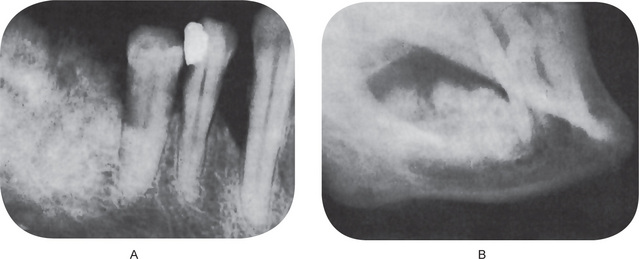

Chaudhry and his associates have reviewed all cartilaginous tumors of the jaws reported in the English literature between 1912 and 1959. Both primary and secondary jaw chondrosarcomas appear as an expanding lesion which is frequently painless (Fig. 2-76 A). The mucosa is often intact. The tumor may occur in the mandible or the maxilla with primary involvement of the alveolar ridge, or sometimes in the maxilla near the antrum. Resorption and exfoliation of teeth sometimes occur. In general, these lesions are invasive and destructive and metastasize readily.

Radiographic Features

Radiographic findings do not differ remarkably from those seen in the benign chondroma unless the lesion is of relatively long standing and has produced considerable destruction of bone. Occasional tumors will appear as radiopaque lesions because of calcification of the neoplastic cartilage (Fig. 2-76 B, C).

Histologic Features

Chondrosarcoma is one of the most difficult of the malignant tumors of the bone for the pathologist to diagnose. The criteria that differentiate a low-grade chondro-sarcoma from a chondroma are very subtle. However, some lesions may appear to be malignant by conventional criteria but are benign. The features proposed by Lichtenstein and Jaffe are very helpful when viable fields are studied. These include many cells with plump nuclei, more than an occasional cell with two such nuclei, and especially, giant cartilage cells with large single or multiple nuclei or with clumps of chromatin. The correct diagnosis depends on correct interpretation of the subtle qualitative characteristics. Furthermore, malignant foci may be obscured by necrotic regions or by zones with insufficient cytologic evidence for the diagnosis of sarcoma.

Most chondrosarcomas have sheets of chondrocytes, which may have a lobulated growth pattern under low power. Some chondrosarcomas, however, have pronounced cluttering of the chondrocytes similar to the classic appearance in synovial chondromatosis. Chondrosarcoma is not a spindle cell neoplasm, because chondrocytes lie within lacunae. Occasionally, however, the nuclei appear spindle shaped (Fig. 2-77).

Figure 2-77 Low power chondrosarcoma. This is the low power microscopic appearance of a chondrosarcoma. The tissue is recognizable as cartilage, and there are chondrocytes in clear spaces, but there is no orderly pattern. At the bottom, this neoplasm can be seen invading and destroying bone.

Most of the secondary chondrosarcomas are extremely undifferentiated, so that a clear histologic diagnosis of chondrosarcoma is usually not possible. In osteochondroma, there is a columnar arrangement of the chondrocytes towards the base. This orderly arrangement is lost when chondrosarcoma supervenes. Nodules of cartilage apparently permeating soft tissues and separated from the main mass of the tumor also are evidence of chondrosarcoma. Mitotic figures are uncommon in chondrosarcoma.

The mesenchymal chondrosarcoma consists of sheets of small, round or ovoid, undifferentiated cells interspersed by small islands of well-differentiated cartilage which often show calcification and metaplastic bone formation. Ultrastructural studies by Steiner and his associates have confirmed the presence of two cell types: a poorly differentiated mesenchymal cell and a cell with cartilaginous differentiation in an early stage of maturation.

The clear cell chondrosarcoma consists of single or clustered benign giant cells and tumor cells with clear cytoplasm. Conventional low-grade chondrosarcoma may sometimes be found in areas.

Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma consists of a mix of low grade chondrosarcoma and high grade spindle cell sarcoma where the spindle cells are no longer identifiable as having a cartilage origin. The dedifferentiated portion of the lesion may have histological features of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, osteosarcoma, or undifferentiated sarcoma.

Grading

Chondrosarcomas are graded mainly based on the cellularity of the neoplasm and the cytologic atypia. Because mitotic activity is uncommon in chondrosarcomas, it is not used in grading these tumors. Grade 1-chondrosarcomas are relatively hypercellular compared with enchondromas and have moderate cytologic atypia. Grade 2-chondrosarcomas are more cellular than grade 1, and similarly, cytologic atypia is more pronounced. Grade 3-chondrosarcomas are extremely uncommon. They are characterized by extreme cellularity, large bizarre nuclei, and small foci of spindling at the periphery of the lobule. Sheets of spindle cells are not seen in chondrosarcoma.

Approximately 10% of the tumors that recur have an increase in the degree of malignancy.

Treatment and Prognosis

The only beneficial treatment of the chondrosarcoma is surgery. The malignant nature of this tumor demands wide excision to ensure the greatest possibility for cure. X-ray radiation is of little value, since this type of neoplasm is resistant to such therapy. Neither does chemotherapy appear to be of significant benefit.

Data gathered from known cases of chondrosarcoma of the jaws indicate that the tumor in this location is exceedingly dangerous and often results in death, either from local invasion or from metastasis to distant sites. Although the lesion tends to grow slowly, surgical intervention often stimulates the growth rate and increases the tendency for metastasis.

The mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is even more variable in its clinical course, since metastasis may occur many years after the original surgical procedure and death is markedly delayed. Expression of ‘five-year survival’ is of little significance in the case of this tumor.

Osteosarcoma (Osteogenic sarcoma)

Osteosarcoma is the third most common cancer in adolescence, occurring less frequently than only lymphomas and brain tumors. It is thought to arise from a primitive mesenchymal bone-forming cell and is characterized by production of osteoid.

Clinical Features

Osteosarcoma is a bone tumor that can occur in any bone. It most commonly occurs in the long bones of the extremities near metaphyseal growth plates. The most common sites are femur (42%, with 75% of tumors in the distal femur), tibia (19%, with 80% of tumors in the proximal tibia), and humerus (10%, with 90% of tumors in the proximal humerus). Other significant locations are the skull or jaw (8%) and pelvis (8%).

Incidence is slightly higher in males than in females (1.25: 1). Osteosarcoma occurs chiefly in young persons, the majority between 10-25 years with decreasing incidence as the age advances. It is very rare in young children and the incidence increases steadily with age; a more dramatic increase in adolescence corresponds with the growth spurt.

The exact cause of osteosarcoma is unknown. However, a number of risk factors exist. Rapid bone growth appears to predispose patients to osteosarcoma, as suggested by the increased incidence during the adolescent growth spurt, and osteosarcoma’s typical location near the metaphyseal growth plate of long bones. Exposure to radiation is the only known environmental risk factor. A genetic predisposition may exist, for example:

• Familial cases where the deletion of chromosome 13q14 thus inactivating the retinoblastoma gene (RB gene) leading to development of retinoblastoma and is associated with a particularly high risk of osteosarcoma to develop.

• Bone dysplasias, including Paget’s disease, fibrous dysplasia, enchondromatosis, and hereditary multiple exostoses, increase the risk of osteosarcoma.

• Li-Fraumeni syndrome (germline TP53 mutation) is a predisposing factor for osteosarcoma development.

• Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (i.e. autosomal recessive association of congenital bone defects, hair and skin dysplasias, hypogonadism, cataracts) is associated with increased risk of osteosarcoma.

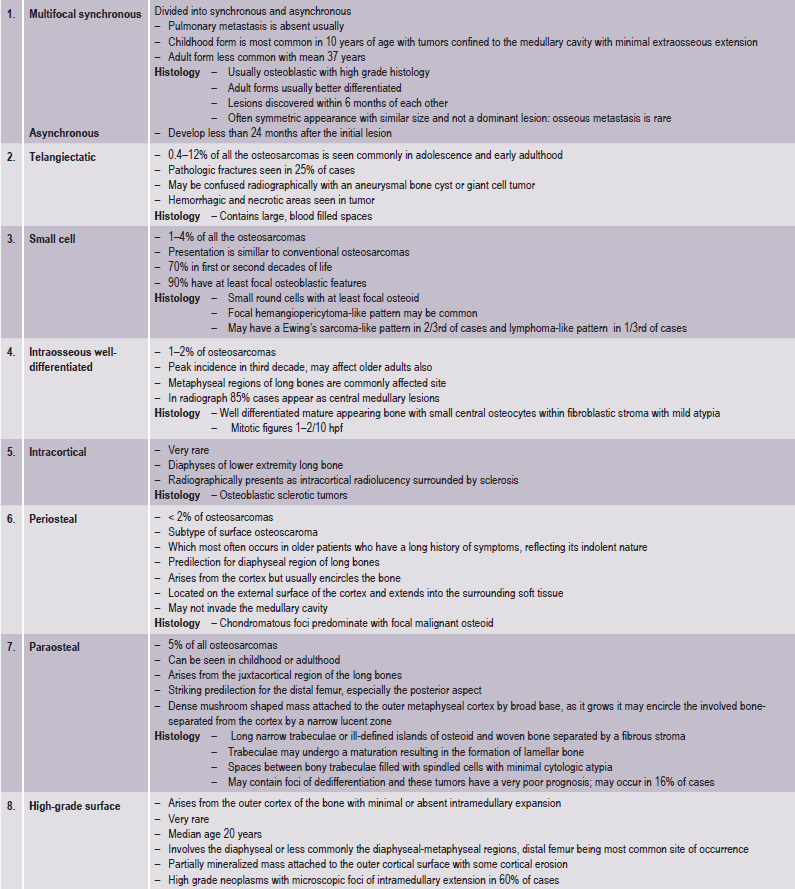

A number of variants of osteosarcoma are: conventional types (i.e. osteoblastic, chondro blastic, fibroblastic); multifocal; telangiectatic; small cell; intraosseous well-differentiated; intracortical; periosteal; paraosteal; high-grade surface; and extraosseous (Table 2-15).

Swelling and pain, particularly with activity of the involved bone, are the early features of the neoplasm. Patients may complain of a sprain, arthritis, or so-called grawing pain.

Systemic symptoms, such as fever and night sweats, are rare. Sometimes the presenting signs and symptoms are indistinguishable from those of osteomyelitis. Often, the patient has a history of trauma, though pathologic fractures are not particularly common. (The exception is the telangiectatic type of osteosarcoma, which is commonly associated with pathologic fractures). If in an extremity, the pain may result in a limp. Regional lymphadenopathy is unusual.

Oral Manifestations

Several large series of cases of osteo-sarcoma of the jaws have been published in recent years, contributing greatly to our knowledge of this tumor. The largest series was that of Garrington and his associates who analyzed 56 cases and found that the most common presenting symptoms of the patients were swelling of the involved area, often producing facial deformity and pain, followed by loose teeth, paresthesia, toothache, bleeding, nasal obstruction and a variety of other manifestations (Fig. 2-78).

The median age of the patients at the time of appearance of the first related symptoms was about 27 years, nearly a decade older than patients with osteosarcoma of other bones of the skeleton. Of 44 cases of osteosarcoma of the jaws and facial bones reported by Kragh and his associates, the mean age of occurrence was 33 years. In all series, mandibular tumors are more common than those in the maxilla, and there is usually a predilection for occurrence in males.

As indicated previously, it has been reported on numerous occasions that trauma to other sites in the skeleton has preceded the development of osteosarcoma at that site. Furthermore, it is recognized that osteosarcoma develops with considerable frequency in bone affected by osteitis deformans, or Paget’s disease, as in the 80 cases studied by Price and Goldie. Finally, bone that has been subjected to therapeutic X-ray radiation may undergo malignant transformation, as in the 50 cases studied by Arlen and his associates. Surprisingly, in nearly all cases of osteosarcoma of the jaws, there is no preceding history of trauma or of Paget’s disease. However, cases of osteosarcoma developing after X-ray radiation for benign jaw lesions such as fibrous dysplasia and giant cell granuloma are adequately documented; 43 such cases were discussed by De Lathouwe and Brocheriou in their review of the literature.

Parosteal (juxtacortical) osteosarcoma is a very uncommon form of osteosarcoma which occurs in many bones throughout the skeleton and is characterized by its slow growth and good prognosis because of its lower tendency for metastasis. It is exceedingly rare in the jaws, although two cases have been reported in a series of 20 osteosarcomas of the maxilla and mandible by Roca and his coworkers. A total of seven cases in the jaws have now been reported, according to a recent review by Bras and his coworkers (Fig. 2-79).

Periosteal osteosarcoma appears to be an aggressive variant of the parosteal osteosarcoma and has been separated out as an entity by Unni and his associates because of its more active biologic behavior. Nevertheless, it still has a much better prognosis than the conventional intramedullary osteosarcoma.

Extraosseous osteosarcoma involving extraskeletal osteosarcoma of soft tissue in the absence of a primary skeletal tumor occasionally occurs but is rare. Osteosarcoma occurring in certain organs, such as the breast, liver and kidney, may only represent malignant teratoma but, excluding these, a true soft-tissue osteosarcoma does exist. It is a highly malignant tumor and has been discussed by Miller and his associates.

Radiographic Features

As with many bone tumors, both benign and malignant, the radiographic appearance is variable and depends on the amount of tumor bone synthesized by the malignant osteoblasts. In those tumors with little tumor bone, the radiographic appearance will be radiolucent; whereas those tumors with much tumor bone will be radiodense. Mixed lucent-dense lesions indicate an intermediate degree of tumor bone formation. Cumulus cloud densities form within the intramedullary and soft tissue components caused by mineralizing tumor osteoid.

There are three features of osteosarcoma that are classics:

• Small streaks of bone radiate outward from approximately 25% of these tumors. This produces a sunray (sunburst) pattern.

• This tumor may grow within the periodontal membrane space causing resorption of the adjacent bone resulting in uniform widening of the space. Widening of the periodontal membrane space may also be seen in other conditions such as chondrosarcoma and scleroderma, and so it is not pathognomonic.

• In the long bones affected with osteosarcoma, the periosteum is elevated over the expanding tumor mass in a tentlike fashion. At the point on the bone where the periosteum begins to merge (edge of the tent), an acute angle between the bone surface and the periosteum is created. This is called Codman’s triangle and is highly suspicious for osteosarcoma.

Histologic Features

Gross tissue of osteoblastic osteosarcoma show white-tan, yellow in color and firm in consistency. The chondroblastic elements appear as translucent lobules and fibroblastic elements appear as tan colored, with soft, or firm consistency. Hemorr hage and necrosis are common.

Osteosarcoma is characterized by the proliferation of both atypical osteoblasts and their less differentiated precursors. In general, the characteristic feature of osteosarcoma is the presence of osteoid formed by malignant osteoblasts in the lesion, even at sites distant from bone (e.g. the lung). Stromal cells may be spindle shaped and atypical with irregularly shaped nuclei.

A number of distinct histologic types of osteosarcoma exist. The conventional type is the most common in childhood and adolescence, and has been subdivided on the basis of the predominant features of the cells (i.e. osteoblastic, chondroblastic, fibroblastic), though the subtypes are clinically indistinguishable.

In the osteoblastic type of osteosarcoma atypical, neoplastic osteoblasts exhibit considerable variation in size and shape, show large, deeply staining nuclei and are arranged in a disorderly fashion about trabeculae of bone. In addition, there is a great deal of new tumor osteoid and bone formation, mostly in an irregular pattern and sometimes in solid sheets rather than in trabeculae. This comprised nearly 60% of the jaw lesions of Garrington’s group. Varying degrees of proliferation of anaplastic fibroblasts are also found, and in the absence of significant amounts of tumor osteoid or bone, when these cells predominate, the lesion is designated as a fibroblastic type of osteosarcoma. This type comprised about 34% of the above group of jaw tumors. Some tumors show occasional areas of neoplastic myxomatous tissue and cartilage. Most authorities currently believe that even though a lesion is composed chiefly of malignant cartilage, it should be diagnosed as osteosarcoma if significant malignant osteoblasts and tumor osteoid or bone can be identified since the course of the lesion will probably be that of an osteosarcoma rather than of a chondrosarcoma (Fig. 2-81). However, when only limited chondroid is present, it is termed chondroblastic type and this form accounts for less than 10% of jaw osteosarcomas.

Staging

The purpose of staging tumors is to stratify risk groups. The conventional staging system used for other solid tumors is not appropriate for skeletal tumors because these tumors rarely involve lymph nodes or spread regionally.

The osteosarcoma staging system can be summarized as follows:

Treatment

In the case of long bone involvement, amputation is a prime requisite. Neoplasms in other sites must be treated by radical resection, but, especially in the jaws, it is difficult to perform adequate and complete excision. Primary X-ray radiation is of no avail. Neoadjuvant (preoperative) chemotherapy has been found to facilitate subsequent surgical removal by shrinking the tumor. More recently, adjuvant chemotherapy in combination with surgery, including resection of pulmonary metastases, has appeared to offer promise of increased survival from this disease.

Patients who have a good histopathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (>95% tumor cell killed or necrosed) have a better prognosis than those whose tumors do not respond as favorably. The prognosis depends considerably upon the condition of the patient and the duration of the lesion when treatment is instituted. Under favorable conditions, when skeletal osteosarcoma was treated by proper radical means, the five-year cure rate of a series of 183 cases of sclerosing osteosarcoma reported by Geschickter and Cope-land was 21%, while the five-year cure rate for their series of 149 cases of osteolytic osteosarcoma was 16%.

Of 45 cases of osteosarcoma of the jaws available for follow-up in the Garrington series, 50% developed clinical evidence of metastasis, most commonly to the lung. The overall five-year survival rate for maxillary osteosarcoma was 25% and for mandibular osteosarcoma, 41%. There was no correlation between histologic characteristics of the tumor and prognosis.

The overall five-year survival rate for patients diagnosed between 1974 and 1994 was 63% (59% for males, 70% for females).

Malignant Lymphoma

The malignant lymphomas constitute a group of neoplasms of varying degrees of malignancy which are derived from the basic cells of lymphoid tissue, the lymphocytes and histiocytes in any of their developmental stages. For this reason these diseases are intimately related to each other, and a concise distinction cannot always be drawn even on histologic grounds. Lukes has rendered the following excellent definition of this disease process, “Malignant lymphoma is a neoplastic proliferative process of the lymphopoietic portion of the reticuloendothelial system that involves cells of either the lymphocytic or histiocytic series in varying degrees of differentiation and occurs in an essentially homogeneous population of a single cell type. The character of histologic involvement is either diffuse (uniform) or nodular and the distribution of involvement may be regional or systemic (generalized); however, the process is basically multicentric in character. Lymphomas and leuke mias of lymphocytes and histiocytes are identical, and the variation in the frequency of cells appearing in the peripheral blood appears to be relate to differences in distribution and is dependent usually upon the occurrence of bone marrow involvement.”

The malignant lymphomas, with the exception of Hodgkin’s disease which is well established nosologically, are currently in a state of change relative to a universally accepted classification. The non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas as they are known nowadays, were called lymphosarcomas for many years. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Gall and Mallory and Jackson and Parker developed classifications for the malignant lymphomas including Hodgkin’s disease. These classifications were generally accepted, but in 1956, Rappaport and his colleagues presented a new classification of the malignant lymphomas. Rappaport revised this classification in 1966 and currently it is used by many pathologists because of its clinicopathologic relevance. However, many authorities claim that the modified Rappaport classification is scientifically inaccurate. In 1974, Lukes and Collins developed an immunologic classification of the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas which was scientifically accurate but difficult to use in a clinical situation. During the ensuing years, a number of classifications of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas have evolved. These too have not been based upon extensive clinicopathologic correlation and in addition have required modifications as new entities or variants of lymphomas were recognized.

At the present time, there are six well-described classifications of the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Each has its proponents, advantages and disadvantages. As a result, the US-based National Cancer Institute sponsored an international study of nearly 1,200 cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The panel consisted of six ‘expert’ proponents of the respective classifications as well as six other pathologists with experience and expertize in lymph node pathology. The study was designed “to assess the clinical applicability and reproducibility of six major histopathologic systems of classification for the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and to evaluate whether any classification was superior to others in these regards.” Based upon morphologic criteria only, without the use of immunologic methods, a working classification of 10 major types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was devised. This working classification has provided a means for translating a lymphoma into the various classifications but most importantly has reaffirmed the prognostic significance of a follicular architecture in the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Unfortunately, there is no unanimity of opinion as to whether this system is superior to the others or to the revised Rappaport classification as far as clinical significance, scientific accuracy and reproducibility is concerned. Because these current classifications of the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are as yet not finalized and universally accepted, only a division of the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and Hodgkin’s disease will be used here until there is unification of the lymphoma concept.

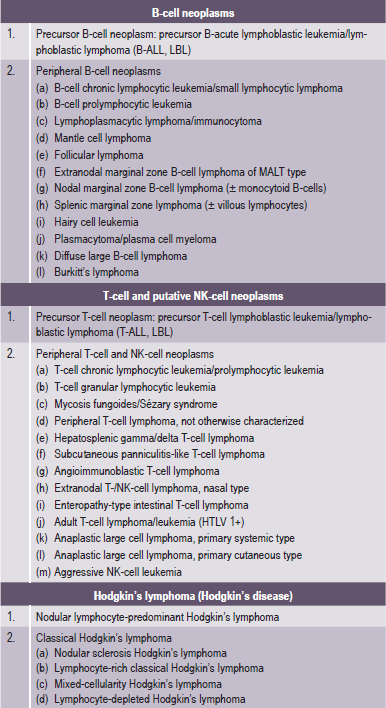

Over the years, classifications have evolved from purely morphologic systems combined with prognostic categories (working classification) to one which integrate immunohistochemical data (Revised European American Lymphoma and WHO Classifications).

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

The American Cancer Society predicted that approximately 23,000 cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas would occur in the United States in 1982. This accounts for approximately 70% of all new cases of malignant lymphoma. The non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative malignancies which can involve both lymph nodes and lymphoid organs as well as extranodal organs and tissues. The lymph nodes of the head and neck are commonly involved as well as the extranodal tissues of this area.

Classification

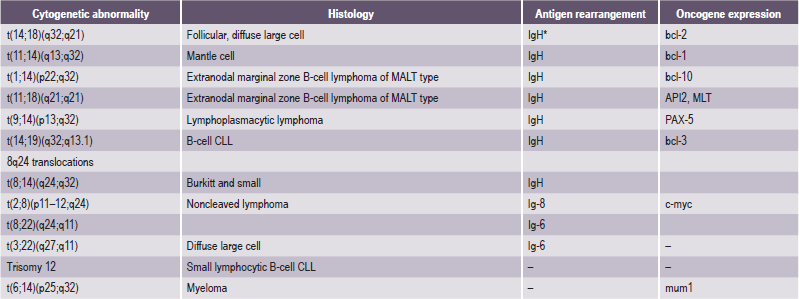

The treatment of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) has been hampered by lack of a uniform classification system. In 1982, results of a consensus study were published as the Working Formulation. The Working Formulation combined results from six major classification systems into one classification. This allowed comparison of studies from different institutions and countries. The Rappaport classification, which also follows, is no longer in common use (Table 2-16).

Table 2-16

Comparison of working formulation and Rappaport classification

| Working Formulation | Rappaport classification |

| Low-grade | |

| A. Small lymphocytic, consistent with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (SL) | Diffuse lymphocytic, well-differentiated (DLWD) |

| B. Follicular, predominantly small cleaved cell (FSC) | Nodular lymphocytic, poorly differentiated (NLPD) |

| C. Follicular, mixed small cleaved and large cell (FM) | Nodular mixed, lymphocytic and histiocytic (NM) |

| Intermediate-grade | |

| D. Follicular, predominantly large cell (FL) | Nodular histiocytic (NH) |

| E. Diffuse, small cleaved cell (DSC) | Diffuse lymphocytic, poorly differentiated (DLDP) |

| F. Diffuse mixed, small and large cell (DM) | Diffuse mixed, lymphocytic and histiocytic (DM) |

| G. Diffuse, large cell cleaved or noncleaved cell (DL) | Diffuse histiocytic (DH) |

| High-grade | |

| H. Immunoblastic, large cell (IBL) | Diffuse histiocytic (DH) |

| I. Lymphoblastic, convoluted or nonconvoluted cell (LL) | Diffuse lymphoblastic (DL) |

| J. Small noncleaved cell, Burkitt’s or non-Burkitt’s (SNC) | Diffuse undifferentiated Burkitt’s or non-Burkitt’s (DU) |

Source: Adapted from Med News, National Cancer Institute, 2004.