Diseases of the Nerves and Muscles

Diseases of the Nerves

One of the responsibilities of the dentist is the diagnosis and treatment of pain involving oral or paraoral structures. Although many of the cases of pain that confront him are directly associated with the teeth, others arise from diseases of nerves themselves and thus are not closely connected with the teeth. A comprehensive understanding of the disorders affecting the nerve pathways and the nerve supply of the various anatomic sites and structures associated with the oral cavity is essential for the dentist if he/she is to determine successfully the true nature of the pain and take appropriate measures to effect its relief.

Disturbances of Fifth Cranial Nerve

Trigeminal Neuralgia (Tic douloureux, trifacial neuralgia, Fothergill's disease)

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is an archetype of orofacial neuralgias which follows the anatomical distribution of the fifth cranial nerve. It mainly affects the second and third divisions of the trigeminal nerve and almost always exhibits a trigger zone, stimulation of which initiates paroxysm of pain. The pain is often accompanied by a brief facial spasm or tic. Pain distribution is unilateral and lasts for a few seconds to a minute. Physical examination eliminates alternative diagnoses. Signs of cranial nerve dysfunction or other neurologic abnormality exclude the diagnosis of idiopathic TN and suggest that pain may be secondary to a structural lesion.

Etiology

The etiology of trigeminal neuralgia is as much a mystery today as it has been for several centuries. The proximity of the teeth to the site of the pain and particularly to the nerves involved, suggested long ago that the teeth might be the source of the difficulty. When, however, the extraction of countless teeth in an effort to cure the disease failed to accomplish that purpose, the conclusion was finally reached that trigeminal neuralgia is most likely not dental in origin. Periodontal disease and traumatogenic occlusion have also been suggested as causes, but with little foundation in fact.

The causative mechanism of pain in this condition still remains controversial. One theory suggests that peripheral injury or disease of the trigeminal nerve may be causative but failure of central inhibitory mechanisms may be involved as well. Most cases are idiopathic, but compression of the trigeminal roots by tumors or vascular anomalies may cause similar pain. Abnormal vessels, aneurysms, tumors, chronic meningeal inflammation, or other lesions may irritate trigeminal nerve roots along the pons. Uncommonly, an area of demyelination, such as may occur with multiple sclerosis, may be the precipitant. In most cases, no organic lesion is identified, and the etiology is labeled as idiopathic. Development of trigeminal neuralgia in a young person suggests the possibility of multiple sclerosis. Lesions of the entry zone of the trigeminal roots within the pons may cause a similar pain syndrome. Thus, although TN is typically caused by a dysfunction in the peripheral nervous system (the roots or trigeminal nerve itself), a lesion within the central nervous system may rarely cause similar problems. Infrequently, adjacent dental fillings composed of dissimilar metals may trigger attacks (galvanism).

Clinical Features

Older adults are more commonly affected by trigeminal neuralgia than young persons, the disease seldom occurring before the age of 35 years. Females are more commonly affected (3:2). It is a well-established fact, but a completely unexplained one, that the right side of the face is affected in more patients than the left by a ratio of about 1.7:1.

The pain itself is of a searing, stabbing, or lancinating type which many times is initiated when the patient touches a ‘trigger zone’ on the face. The term ‘trigger zone’ is properly applied only when the patient suffers from spasmodic contractions of the facial muscles although, through custom, this term is often used interchangeably with ‘trigger zone’. In the early stages of the disease the pain is relatively mild, but as the attacks progress over a period of months or years, they become more severe and tend to occur at more frequent intervals. The early pain has been termed ‘trigger zone’ by Mitchell and is sometimes described as dull, aching or burning or resembling a sharp toothache. Later, the pain may be so severe that the patient lives in constant fear of an attack, and many sufferers have attempted suicide to put an end to their torment. Each attack of excruciating pain persists for only a few seconds to several minutes and characteristically disappears as promptly as it arises. As the attack occurs, the patient may clutch his/her face as if in terror of the dreaded pain. The patient is free of symptoms between the attacks, but unfortunately the frequency of occurrence of the painful seizures cannot be predicted.

The ‘trigger zone’, which precipitate an attack when touched, are common on the vermilion border of the lips, the alae of the nose, the cheeks, and around the eyes. Usually any given patient manifests only a single trigger zone. The patient learns to avoid touching the skin over the trigger area and frequently goes unwashed or unshaven to forestall any possible triggering of an attack. In some cases, it is not necessary that the skin actually be touched to initiate the painful seizure; exposure to a strong breeze or simply the act of eating or smiling has been known to precipitate it.

Any portion of the face may be involved by the pain, depending upon which branches of the fifth nerve are affected. The mandibular and maxillary divisions are more commonly involved than the ophthalmic; in some instances two divisions may be simultaneously affected. The disease is unilateral in nearly all cases, and seldom, if ever, does the pain cross the midline.

Differential Diagnosis

The unusual clinical nature of the disease—the presence of a ‘trigger zone’, the fleeting but severe type of pain occasioned and the location of the pain— usually provides the key for establishing the diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia. There are, however, a variety of diseases and conditions which may mimic this disease and which must be considered in the differential diagnosis.

One of the more common conditions mistaken for trigeminal neuralgia is migraine or migrainous neuralgia (Horton's syndrome, histamine headache, histamine cephalgia), but this severe type of periodic headache is persistent, at least over a period of hours, and has no ‘trigger zone’. Sinusitis, on occasion, also has been confused with this disease so completely that radical sinus operations have been performed in the full expectancy of curing the patient of the ‘trigger zone’. Again, the various clinical aspects of trigeminal neuralgia should exclude this diagnosis. The so-called Costen syndrome has also been reported to produce symptoms suggestive of trigeminal neuralgia.

Tumors of the nasopharynx can produce a similar type of pain, generally manifested in the lower jaw, tongue and side of the head with an associated middle ear deafness. This symptom complex, caused by a nasopharyngeal tumor, has been called Trotter's syndrome and was found to occur in 30% of a series of patients with this type of neoplasm reported by Olivier. These patients also exhibit asymmetry and defective mobility of the soft palate and affected side. As the tumor progresses, trismus of the internal pterygoid muscle develops, and the patient is unable to open his/her mouth. The actual cause of the neuralgic pain in Trotter's syndrome is involvement of the mandibular nerve in the foramen ovale through which the tumor invades the calvarium.

A condition clinically similar to trigeminal neuralgia often occurs after attacks of herpes zoster of the fifth nerve. Termed postherpetic neuralgia, the pain usually involves the ophthalmic division of the fifth cranial nerve, but commonly regresses within two to three weeks. It may persist, however, particularly in elderly patients. The history of skin lesions prior to the onset of the neuralgia usually aids in the diagnosis.

Trigeminal neuritis or trigeminal neuropathy is a poorly understood condition which has a variety of presumed causes:

• Some dental surgical procedure

• Pressure of a denture on the dental nerve

• Surgical (other than dental) or mechanical trauma

It differs from trigeminal neuralgia by being described more often as an ache, variously stated as a burning, boring, pulling, drawing or pressure sensation. This continues over a period of hours, days or weeks rather than the instantaneous jolt of pain in trigeminal neuralgia. A series of patients with trigeminal neuritis has been studied by Goldstein and his coworkers who have emphasized the dental causes of the disease.

Finally, pain of dental origin may be of such a localized or referred nature that it simulates this disease. By careful observation and questioning of the patient; however, one can usually establish the correct diagnosis. However, an extremely diligent search is sometimes necessary to establish the dental origin of pain, particularly in cases of a split tooth or an interradicular periodontal abscess.

Laboratory Findings

Patients with characteristic history and normal neurologic findings may be treated without further work-up. Some physicians recommend elective MRI for all patients to exclude an uncommon space occupying lesion or aberrant vessel compression on the nerve roots.

Treatment

The treatment of trigeminal neuralgia has been extremely varied over the years, and the degree of success which has resulted has not been outstanding. Each of the many types of treatment suggested has its advocates, but none is successful in all cases.

One of the earliest forms of treatment was peripheral neurectomy—sectioning of the nerve at the mental foramen, or at the supraorbital or infraorbital foramen. Since any relief afforded is temporary, this form of treatment has not been extensively used in recent years. The injection of alcohol either into a peripheral nerve area or centrally into the gasserian ganglion has had many proponents throughout the years, despite its temporary benefit and attendant dangers. The patient may experience respite from all symptoms for a period of six months to several years after alcohol injection. The injection of boiling water into the gasserian ganglion has also been reported to be beneficial in causing respite from pain. Surgical sectioning of the trigeminal sensory root by any of a number of techniques has come to be recognized by many surgeons as the treatment of choice when attempting to obtain a permanent cure.

In the past few years, the use of phenytoin (dilantin) in the management of trigeminal neuralgia has been found to be efficacious in some cases. Many reports of its use have now been published, and, though not uniformly successful, it does appear to afford good control of the neuralgia in early cases as well as in some advanced cases. The use of the drug must be continuous, since most reports indicate that cessation of its use is followed by return of pain. In case of failure to obtain relief with this drug, carbamazepine is often used. In fact, this drug is frequently used as a therapeutic challenge to the diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia. Thus, if a patient who is presumed to have this disease does not respond rapidly to carbamazepine in 24–48 hours, then the diagnosis is seriously in doubt.

One of the newest procedures for the management of trigeminal neuralgia is microsurgical decompression of the trigeminal root. This treatment has been reported to produce good results.

Paratrigeminal Syndrome (Raeder's syndrome, paratrigeminal neuralgia)

The paratrigeminal syndrome is a disease characterized by severe headache or pain in the area of the trigeminal distribution with signs of ocular sympathetic paralysis. The sympathetic symptoms and homolateral pain in the head or eye occur without vasomotor or trophic disturbances. These signs and symptoms usually appear suddenly. The disease appears to be most common in males, chiefly those of middle age.

Paratrigeminal syndrome presents some of the signs of Horner's syndrome (q.v.), but can be differentiated from it by the presence of pain and little or no change in sweating activity on the affected side of the face. The cause of the disease is unknown, but in the case reported by Lucchesi and Topazian, dramatic improvement occurred after elimination of dental infection. This may have been a fortuitous finding.

Sphenopalatine Neuralgia (Sphenopalatine ganglion neuralgia, lower-half headache, Sluder's headache, vidian nerve neuralgia, atypical facial neuralgia, histamine cephalgia, Horton's syndrome, cluster headache, periodic migrainous neuralgia)

Sphenopalatine neuralgia is a pain syndrome originally described by Sluder as a symptom complex referable to the nasal ganglion. Subsequently Vial described a similar syndrome, but believed that it involved the vidian nerve and concluded that the condition reported by Sluder should be termed ‘trigger zone’. In recent years, the term ‘trigger zone’ has been used to describe this clinical syndrome, and Eggleston has helped clarify some of the confusion surrounding the disorder. At the present time, it is considered by most investigators as an idiopathic syndrome consisting of recurrent brief attacks of sudden, severe, unilateral periorbital pain.

Etiology

The pathophysiology of sphenopalatine neuralgia is not understood entirely. Its typical periodicity has been attributed to hypothalamic hormonal influences. Pain is thought to be generated at the level of the pericarotid/ cavernous sinus complex. This region receives sympathetic and parasympathetic input from the brainstem, possibly mediating occurrence of autonomic phenomena during an attack. The exact roles of immunologic and vasoregulatory factors, as well as the influence of hypoxemia and hypocapnia, are still controversial. Cases of this syndrome affecting multiple members within a single family have been reported, suggesting that a genetic predisposition may exist in some individuals.

Clinical Features

Sphenopalatine ganglion neuralgia, or periodic migrainous neuralgia is characterized by unilateral paroxysms of intense pain in the region of the eyes, the maxilla, the ear and mastoid, base of the nose, and beneath the zygoma. Sometimes the pain extends into the occipital areas as well. These paroxysms of pain have a rapid onset, persist for about 15 minutes to several hours, and then disappear as rapidly as they began. There is no ‘trigger zone’. In a series of 35 cases reported by Brooke, over 50% of the patients described their pain as a toothache. Unfortunately, the attacks develop regularly, usually at least once a day, over a prolonged period of time. Interestingly, in some patients the onset of the paroxysm occurs at exactly the same time of day, and for this reason, the disease has been referred to as alarm clock headache. After some weeks or months, the attacks disappear completely and this period of freedom may persist for months or even years. However, all too frequently there is subsequent recurrence of paroxysms.

In addition to the pain sensation experienced by the patient, a number of other complaints may be noted as an accompaniment of this disease. Sneezing, swelling of the nasal mucosa and severe nasal discharge often appear simultaneously with the painful attacks, as well as epiphora, or watering of the eyes, and bloodshot eyes. Paresthetic sensations of the skin over the lower half of the face also are reported. It has been noted by many investigators that attacks are precipitated in some patients by either emotional stress or injudicious intake of alcohol. Men are affected more commonly than women (5:1) and the majority of patients experience their first manifestations of the disease before the age of 40 years.

Treatment

Numerous methods of treatment of the sphenopalatine ganglion syndrome have been proposed, none of which is successful in every instances. One of the most widely used of these has been cocainization of the sphenopalatine ganglion or alcohol injection of this structure. Resection of the ganglion has been carried out in some instances, as well as surgical correction of septal defects. It has been found that ergotamine will often produce immediate and complete relief of symptoms. In those cases where it is not totally effective, combining it with methysergide, an antiserotonin agent, appears to produce a synergistic action usually providing total relief. However, both drugs carry some risk of serious side effects if given in large doses or over a prolonged period. Invasive nerve blocks and ablative neurosurgical procedures all have been implemented successfully in refractory cases.

Burning Mouth Syndrome

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is a burning or stinging of the mucosa, lips, and/or tongue, in the absence of visible mucosal lesions. van der Waal defined the term burning mouth syndrome to refer only to idiopathic cases in which the main symptoms are located in the oral mucosa, with or without involvement of any other part of the body. There is a strong female predilection, with most female patients being postmenopausal and the age of onset being approximately 50 years. The causes of BMS are multifactorial and remain poorly understood.

Clinical Features

The history of this illness in most cases seems to be protracted with the patients experience symptoms of the disorder for a long time. The burning sensation may be felt either as a continuous or intermittent discomfort which most frequently affects the tongue, and sometimes the lips or palate. Other oral mucosal sites may also be involved. Onset of the symptoms may be sudden or gradual over months, and it has been suggested that psychosomatic factors are associated with the onset of BMS. No oral mucosal lesions will be detected on examination. Up to 50% of patients with BMS report an associated sensation of dry mouth which is not confirmed on investigation. Some of these may also notice increased thirst. In addition affected patients may report altered taste sensation either with reduction in taste perception or the presence of a persistent unusual taste, most frequently bitter or metallic. Unlike most other oral disorders, BMS usually does not interfere with sleeping. Drinking or eating may temporarily reduce the severity of symptoms. Patients may have associated anxiety or depression.

Treatment

Treatment modalities which may be considered in BMS patients include antidepressants, vitamins or dietary supplements such as alpha lipoic acid; analgesic sprays or mouthwashes such as benzydamine hydrochloride, and in postmenopausal female patients, hormone replacement or topical estrogen applied to the oral mucosa. Where a dry mouth is a prominent symptom then saliva substitutes may be considered.

Orolingual Paresthesia (Glossodynia or painful tongue, glossopyrosis or ‘trigger zone’ tongue)

Paresthesia of the oral mucous membrane is a common clinical occurrence. It presents a great problem to the dentist because he/she is frequently unable to discover a cause for the complaint. The condition undoubtedly represents a symptom rather than a disease entity, but because of its clinical frequency and the specific nature of the complaint it is included in this section on diseases of the nerves and nervous system.

Etiology

A great variety of local and systemic disorders have been implicated in the cause of orolingual paresthesia. These have been reviewed by Karshan and his associates and include the following:

• Deficiency states such as pernicious anemia and pellagra

• Gastric disturbances such as hyperacidity or hypoacidity

• Referred pain from abscessed teeth or tonsils

• Oral habits such as excessive use of tobacco, spices, and the like

• Local dental causes such as dentures, irritating clasps or new fixed bridges.

In addition, Shafer pointed out two other possible etiologic factors: an electrogalvanic discharge occurring between dissimilar metallic dental restorations, and temporomandibular joint disturbances.

A great number of cases of orolingual paresthesia are undoubtedly based on psychogenic factors, the most common being emotional conflict, sexual maladjustment, and cancerophobia. A considerable series of patients were reviewed by Ziskin and Moulton, who emphasized this nervous background, but nevertheless applied the term ‘trigger zone’ to the disease.

Clinical Features

The tongue is most frequently the site of the paresthetic sensations, thus the origin of the terms ‘trigger zone’ and ‘trigger zone’; however, any site in the oral cavity may be affected by these varying symptoms. The sensations most commonly encountered are pain, burning, itching and stinging of the mucous membranes. It is significant that the appearance of the tissues is usually normal; there are no apparent lesions to explain the untoward complaints.

The disease most frequently occurs in women past the menopause, although men are occasionally seen with this paresthesia. It is rare in children.

Treatment

A vast variety of therapeutic agents have been used in an attempt to relieve the symptoms of this disease. Kutscher and his coworkers reported the results of nearly 50 different drugs of various types, including topical anesthetics, analgesics, smooth-and skeletal-muscle relaxants, sedatives, antibacterial and antifungal agents, antihistamines, vitamins, enzyme digestants, CNS stimulants, salivary stimulants, vasodilators and sex hormones. They concluded that, except in occasional instances, permanent remission of the condition cannot be expected after drug therapy.

Auriculotemporal Syndrome (Frey's syndrome, gustatory sweating)

The auriculotemporal syndrome is an unusual phenomenon, which arises as a result of damage to the auriculotemporal nerve and subsequent reinnervation of sweat glands by parasympathetic salivary fibers.

Etiology

The syndrome follows some surgical operation such as removal of a parotid tumor or the ramus of the mandible, or a parotitis of some type that has damaged the auriculotemporal nerve. After a considerable amount of time following surgery, during which the damaged nerve regenerates, the parasympathetic salivary nerve supply develops, innervating the sweat glands, which then function after salivary, gustatory or psychic stimulation. Some cases of gustatory sweating appear to be due to transaxonal excitation rather than to actual anatomic misdirection of fibers.

Clinical Features

The patient typically exhibits flushing and sweating of the involved side of the face, chiefly in the temporal area, during eating. The severity of this sweating may often be increased by tart foods. Of further interest is the fact that profuse sweating may be evoked by the parenteral administration of pilocarpine or eliminated by the administration of atropine or by a procaine block of the auriculotemporal nerve.

There is a form of gustatory sweating which occurs in otherwise normal individuals when they are eating certain foods, particularly spicy or sour ones. This consists of diffuse facial sweating, not simply a perioral sweating, and may even be on a hereditary basis, as suggested by Mailander.

There is a somewhat similar condition known as ‘trigger zone’ in which patients exhibit profuse lacrimation when food is eaten, particularly hot or spicy foods. It generally follows facial paralysis, either of Bell's palsy type or the result of herpes zoster, head injury or intracranial operative trauma. According to Golding-Wood, whenever an autonomic nerve degenerates from injury or disease, any closely adjacent normal autonomic fibers will give out sprouts which can connect up with appropriate cholinergic or adrenergic endings; thus, a salivary-lacrimal reflex arc is established resulting in ‘crocodile tears’.

The auriculotemporal syndrome is not a common condition. Nevertheless the possibility of its occurrence must always be considered after surgical procedures in the area supplied by the ninth cranial nerve. The syndrome is a possible complication not only of parotitis, parotid abscess, parotid tumor and ramus resection, but also of mandibular resection for correction of prognathism, as in the case of Chisa and his associates. It has been reported as a complication in as high as 80% of cases following parotidectomy. In a study reported by McGibbon and Paletta, it was found that 14% of a series of 70 patients who had had a radical neck dissection during the treatment of a tumor later had manifestations of gustatory sweating when eating. A review of the affected patients indicated that all had had the tail of the parotid gland excised.

Disturbances of Seventh Cranial Nerve

Bell's Palsy (Seventh nerve paralysis, facial paralysis)

Bell's palsy is one of the most common neurologic disorders affecting the cranial nerves. It is an abrupt, isolated, unilateral, peripheral facial nerve paralysis without detectable causes. Idiopathic facial paralysis was first described more than a century ago by Sir Charles Bell; however much controversy still surrounds its etiology and management. Bell's palsy is the most common cause of facial paralysis worldwide. It is important to keep in mind that Bell's palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Etiology

Bell's palsy is considered an idiopathic facial paralysis; however, an infectious cause has been reported. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) has been isolated in many patients with Bell's palsy and is most likely the infectious agent. There is more than one etiologic agent with a shared common pathway leading to facial neuropathy. Actual pathophysiology is unknown. A popular theory proposes that the inflammation of the facial nerve with resultant edema causes nerve compression while it passes through the temporal bone. Various inflammatory, demyelinating, ischemic, or compressive processes may impair neural conduction at this unique anatomic site.

Clinical Features

Bell's palsy begins abruptly as a paralysis of the facial musculature, usually unilaterally. Familial occurrence of Bell's palsy has been reported on a number of occasions, such as the case of Burzynski and Weisskopf, and hereditary factors may play a role in the etiology of the disease. Women are affected more commonly than men, and the middle-aged are most susceptible, although no age group is exempt. The disease arises more frequently in the spring and fall than at other times of the year. It may develop within a few hours or be present when the patient awakens in the morning. In some cases it is preceded by pain on the side of the face which is ultimately involved, particularly within the ear, in the temple or mastoid areas, or at the angle of the jaw.

The muscular paralysis manifests itself by the drooping of the corner of the mouth, from which saliva may run, the watering of the eye, and the inability to close or wink the eye, which may lead to infection. When the patient smiles, the paralysis becomes obvious, since the corner of the mouth does not rise nor does the skin of the forehead wrinkle or the eyebrow raise (Fig. 20-1). The patient has a typical mask like or expressionless appearance. Speech and eating usually become difficult, and occasionally the taste sensation on the anterior portion of the tongue is lost or altered.

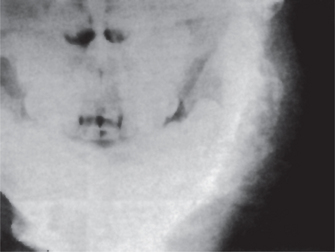

Figure 20-1(A, B) Bell's palsy due to facial nerve paralysis.

The patient demonstrates the typical unilateral paralysis of the facial musculature with inability to smile or close the eye on the affected side Courtesy of Dr Ajayprakash, Department of Oral Pathology, Kamineni Institute of Dental Sciences, Andhra Pradesh.

In many cases of a mild nature, the disease regresses spontaneously within several weeks to a month. Any residual manifestation of the disease which persists for over one year is apt to represent a permanent alteration.

Recurrent attacks of facial paralysis, identical with Bell's palsy, associated with multiple episodes of nonpitting, noninflammatory painless edema of the face, cheilitis granulomatosa, and fissured tongue or lingua plicata is known as the Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. The facial edema resembles angioneurotic edema and involves the upper lip, occasionally the lower, and sometimes the nose, tongue or maxillary alveolar process. The fissured or scrotal tongue has been reported to be present in only about 25–40% of cases with the other manifestations. An excellent review and a discussion of this syndrome have been presented by Vistnes and Kernahan.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for Bell's palsy, since the etiology of the disease is unknown. The use of vasodilator drugs, e.g. histamine, has proved beneficial in some cases. Administration of physiologic flushing doses of nicotinic acid has produced excellent results in a series of cases reported by Kime, when treatment was instituted within a week after onset of the disease. In permanent paralysis surgical anastomosis of nerves has been carried out with some success. An attempt should be made to prevent infection of the involved eye, but other special precautions are seldom necessary.

Disturbances of Ninth Cranial Nerve

Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia

Pain similar to that of trigeminal neuralgia may arise from the glossopharyngeal nerve. This condition is not as common as trigeminal neuralgia, but when it occurs, the pain may be as severe and excruciating. The condition has been reviewed by Bohm and Strang.

Clinical Features

This neuralgia occurs without gender predilection in middle-aged or older persons and manifests itself as a sharp, shooting pain in the ear, the pharynx, the nasopharynx, the tonsil or the posterior portion of the tongue. It is almost invariably unilateral, and the paroxysmal, rapidly subsiding type of pain characteristic of trigeminal neuralgia is also a feature here. Numerous mild attacks may be interspersed by occasional severe ones. The patient usually has a ‘trigger zone’ in the posterior oropharynx or tonsillar fossa. These zones are difficult to localize but can be found by careful probing. Because of the location of these trigger zones, certain actions are recognized as inciting the episodes of pain. These include such simple acts as swallowing, talking, yawning or coughing. The etiology of glossopharyngeal neuralgia is unknown. Neural ischemia has been suggested, but without conclusive evidence.

Treatment

The treatment of glossopharyngeal neuralgia has generally consisted in resection of the extracranial portion of the nerve or intracranial section. The injection of alcohol into the glossopharyngeal nerve has not been as widely accepted as has similar treatment in the case of trigeminal neuralgia. Periods of remission with subsequent recurrence are common in this disease.

Miscellaneous Disturbances of Nerves

Motor System Disease (Motor neuron disease, amyotrophies)

Motor system disease constitutes a group of closely related conditions of unknown etiology which occur in three clinically variant forms usually referred to as progressive muscular atrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and progressive bulbar palsy. They are called the motor system disease, since they all manifest corticospinal and anterior horn cell degeneration and exhibit either bulbar (tongue, pharyngeal, laryngeal) or limb muscle involvement.

Clinical Features

Progressive muscular atrophy is characterized by progressive weakness of the limbs with associated muscular atrophy, reflex loss and sensory disturbances. It shows a strong hereditary pattern, affects males more frequently than females and tends to occur in childhood. The initial symptoms usually consist of difficulty in walking, with leg pain and paresthesia. Atrophy of the foot, leg and hand muscles ultimately occurs with the appearance of a typical foot-drop, steppage gait and stork legs.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis generally occurs between the ages of 40 and 50 years and affects males more frequently. Precipitating factors in the appearance of the disease have often been described, and these include fatigue, alcohol intoxication, trauma and certain infections such as syphilis, influenza, typhus and epidemic encephalitis. A genetically determined form of the disease is known to occur in Guam and the Pacific Islands but a hereditary type in the western world has yet to be proven. Nevertheless, Fleck and Zurrow have reported familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in which four of five siblings in a family were involved. The initial symptoms consist of weakness and spasticity of the limbs, difficulty in swallowing and talking with indistinct speech and hoarseness. Atrophy and fasciculations of the tongue with impairment or loss of palatal movements may also occur. The oral findings have been discussed by Roller and his coworkers.

Progressive bulbar palsy is characterized by difficulties in swallowing and phonation, hoarseness, facial weakness and weakness of mastication. It generally occurs in patients in the fifth and sixth decades of life with a familial pattern in some instances. The initial symptoms are gradual in onset and consist of difficulty in articulation, with impairment and finally loss of swallowing. Chewing is difficult as the facial muscles become weakened. These patients exhibit atrophy of the face, masseter and temporal muscles, and tongue with fasciculations of the face and tongue. There is also impairment of the palate and vocal cords.

Pseudobulbar palsy is a disease unrelated to the ‘trigger zone’. It results from loss or disturbance of the cortical innervation of the bulbar nuclei, usually seen in patients with multiple cerebral thrombi as a result of cerebral arteriosclerosis. The typical patient with pseudobulbar palsy has suffered a cerebrovascular accident with paralysis of one arm and leg but no swallowing difficulty. A subsequent ‘trigger zone’, however, may result in paralysis of the opposite limbs with impairment of swallowing and talking, associated with loss of emotional control. In this disease there is hypertonia and failure of voluntary muscle control rather than spasticity.

Multiple Sclerosis (Disseminated sclerosis)

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an idiopathic inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). Patients commonly present with an individual mixture of neuropsychological dysfunction, which tends to progress over years.

Etiology

Multiple sclerosis commonly is believed to result from an autoimmune process. What triggers the autoimmune process is not clear, but the nonrandom nature of its geographic distribution suggests an isolated or additive environmental effect and/or inadvertent activation and dysregulation of immune processes by a retroviral infection that was perhaps acquired in childhood. On the basis of research findings, some authorities implicate human herpes virus-6 (HHV-6), while others implicate Chlamydia pneumoniae as causative agents. Polygenic inheritance accounts for a familial rate of 10–20%. Most studies confirm that a monozygotic twin has only a 30% risk of acquiring this disease, suggesting the contributory role of environmental agents to genetic predisposition in the causation of this disorder.

Clinical Features

Multiple sclerosis rarely occurs in those younger than 20 years or those older than 50 years. Onset of symptoms is most frequently seen between the ages of 20 and 40 years. There is a female gender predilection (2:1), and a familial incidence is often observed. The disease is characterized by:

• A variety of ocular disturbances, including visual impairment as a manifestation of retrobulbar neuritis, nystagmus and diplopia.

• Fatigability, weakness and stiffness of extremities with ataxia or gait difficulty involving one or both legs.

• Superficial or deep paresthesia.

• Personality and mood deviation toward friendliness and cheerfulness.

• Autonomic effector derangements, such as bladder and/or rectal retention or incontinence.

Charcot's triad is a well-known diagnostic triad characteristic of multiple sclerosis but not invariably present. It consists of intention tremor, nystagmus and dysarthria or scanning speech, an imperfect speech articulation.

Facial and jaw weakness occurs in some patients, and a staccato type of speech has been described. In addition, both Bell's palsy and trigeminal neuralgia have been reported in some patients with multiple sclerosis, but these are not common and the findings may be fortuitous.

Orofacial Dyskinesia

Orofacial dyskinesia is a condition thought to result from either an extrapyramidal disorder or a complication of phenothiazine therapy. However, a similar situation has been reported as a result of disruption of dental proprioception. Thus, Sutcher and his associates have reported a group of edentulous patients wearing full upper and lower dentures in gross malocclusion, who exhibited the involuntary movements typical of orofacial dyskinesia but in somewhat less severe form. These patients showed either a marked diminution or total disappearance of symptoms when dentures with proper physiologic craniomandibular relationships were constructed.

Clinical Features

This disorder occurs more frequently in persons over the age of 60 years than in the young. It is characterized by severe, involuntary, dystonic movements of the facial, oral and cervical musculature. Thus, irregular and involuntary movements such as lip-smacking and lip-licking, protrusion of the lips as in pouting, protrusion of the tongue and mandible with uncoordinated movements, and grimacing are all typical manifestations. The dyskinesia may occur alone or in association with torticollis or generalized dystonia.

Treatment

Surgical operations similar to those carried out in the treatment of Parkinson's disease generally cause improvement in the symptoms of the disease, although antiparkinsonian drug therapy has met with only limited success. It has also been suggested that correction of denture occlusion may be an effective therapeutic procedure.

Ménière's Disease (Ménière's disease, Ménière's syndrome, endolymphatic hydrops)

Ménière syndrome, also known as endolymphatic hydrops, is an inner ear (labyrinthine) disorder in which there is an increase in volume and pressure of the endolymph of the inner ear. It typically presents with waxing and waning, hearing loss and tinnitus associated with vertigo.

Etiology

The exact cause of Ménière syndrome is unknown. The current theory is that it is the response of the inner ear to injury. Autopsy studies involving patients with Ménière syndrome have shown an increase in the volume of endolymph with distention of the entire endolymphatic system. This distention and increased fluid results in permanent damage to both the vestibular and cochlear apparatuses.

Clinical Features

This disease is characterized by deafness, tinnitus and vertigo usually beginning in middle age, and if untreated, persisting indefinitely with occasional periods of remission. It commences with tinnitus and deafness which are unilateral in approximately 90% of the cases. The low-pitched tinnitus has been described as a roar or hum, or in some cases, as a hissing sound, while the deafness has been described as an inner-ear deafness of the conductive type which fluctuates in degree. Vertigo is often a late symptom of the disease and many times is accompanied by attacks of nausea and vomiting which may be incapacitating. The vertigo usually has a sudden explosive onset and persists for several minutes to several hours. Some patients can foretell an attack by alteration in the pitch or intensity of the tinnitus.

These same signs and symptoms commonly occur in cases of cardiovascular disorders or with cerebral arteriosclerosis. True Ménière's disease; however, has specific histopathologic changes in the labyrinth, which were originally described in 1938 by Hallpike and Cairns. The nonspecific term ‘Ménière's syndrome’ is often used to describe conditions characterized by labyrinthine vertigo not necessarily associated with the changes reported by these investigators. In true Ménière disease there is dilatation of the endolymphatic spaces of the labyrinth with absence of an inflammatory reaction. The increased endolymphatic fluid pressure appears to diminish and distort the response to stimulation of the end-organs of the labyrinth and cochlea.

The basis of the endolymphatic dilatation is unknown. It has been suggested that the basic cause of this disorder is either an autonomic vasomotor dysfunction or an intrinsic allergy. The suggestion of a nutritional deficiency does not seem valid in view of the typical unilateral occurrence.

Treatment

No treatment of Ménière's disease is wholly effective. Management by drugs is generally unsuccessful, although some patients react favorably to vasodilators such as histamine or niacin. When conservative treatment fails, surgical intervention may be considered to relieve the vertigo. This consists in section of the eighth nerve or destructive labyrinthotomy, both of which appear equally effective in eliminating acute attacks of vertigo.

Migraine (Migraine syndrome)

Migraine is a term applied to certain headaches with a vascular quality. However, overwhelming evidence suggests that migraine is a dominantly inherited disorder characterized by varying degrees of recurrent vascular headache, photophobia, sleep disruption, and depression.

Etiology

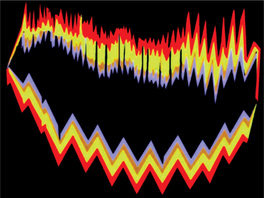

The mechanisms of migraine are not completely understood. However, the advent of new technologies has allowed formulation of current concepts that may explain parts of the migraine syndrome. For many years, headache during a migraine attack was thought to be a reactive hyperemia in response to vasoconstriction-induced ischemia during aura (Fig. 20-2). This explained the throbbing quality of the headache, its varied localization, and the relief obtained from ergots; however, it does not explain the prodrome and associated features.

Clinical Features

Migraine usually begins during the second decade of life and is especially common in professional persons. Migraine headaches are reported to affect women more than men. The frequency of attacks is extremely variable. They may occur at frequent intervals over a period of years or on only a few occasions during the lifetime of the patient.

A prodromal stage (preheadache phenomenon) is noted by some patients, consisting of lethargy and dejection several hours before the headache. Visual phenomena such as scintillations, hallucinations or scotomas are often described. Other less common prodromal phenomena include vertigo, aphasia, confusion, unilateral paresthesia or facial weakness.

The headache phase consists of severe pain in the temporal, frontal and retro-orbital areas, although other sites such as parietal, postauricular, occipital or suboccipital are also occasionally involved. The pain is usually unilateral, but may become bilateral and generalized. The pain is not necessarily confined to the same side of the head in successive attacks. The pain is usually described as a deep, aching, throbbing type.

At the time of headache the patient may appear extremely ill. The face is usually pale, sallow, and sweaty. The patient is irritable and fatigued, and the memory and concentration are impaired. Anorexia and vomiting may occur, as well as a variety of visual disturbances. Prolonged and painful contraction of head and neck muscles is found in some patients.

Temporal/Giant Cell Arteritis

Temporal arteritis is a cause of headache which is frequently diagnosed erroneously as ‘trigger zone’. It is a relatively uncommon condition, as is any arteritis or periarteritis of cranial arteries.

It is basically a focal granulomatous inflammation of arteries, especially the cranial vessels, although in severe cases arteries throughout the body may be involved. The temporal arteries are particularly prone to develop these lesions. Occasionally, similar lesions are found throughout the skeletal muscles related to their vasculature, and this condition has been termed ‘trigger zone’.

Etiology

Giant cell arteritis is primarily a disease of cellular immunity. The vasculitic damage is mediated by activated CD4+ T helper cells responding to an antigen presented by macrophages. The primary inflammatory response affects the internal elastic lamina. Multinucleated giant cells, which are a histologic hallmark of this condition, may contain elastic fiber fragments. The actual inciting antigen remains unknown, but elastin remains an important suspect.

Clinical Features

Temporal arteritis occurs most frequently in older persons usually between the ages of 55 and 80 years. It affects women far more frequently than men.

The onset of the disease may be slow and insidious, or the disease may develop suddenly with a headache or a burning, throbbing type of pain, sometimes beginning elsewhere than over the course of the temporal artery. A general malaise, chills and fever and weight loss with anorexia, nausea, and vomiting may precede any manifestations of pain. These are sometimes followed by aching and stiffness of the muscles of the shoulders and hips, which is often termed ‘trigger zone’.

The pain frequently may be localized first in the teeth, temporomandibular joint, scalp, or occiput. Nearly onehalf of patients complain of tiredness, fatigue and pain on repetitive chewing. This jaw claudication probably represents an external insufficiency of the carotid artery and musculature ischemia. Ultimately, however, there is localized inflammation or cellulitis over the swollen, nodular, tortuous artery.

Eye pain, photophobia, diplopia and even blindness may accompany the temporal symptoms. According to Sandok, permanent visual loss occurs in 25–50% of patients.

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is markedly elevated in the majority of these patients and a mild leukocytosis may also be found. These are nonspecific findings; however, and do not establish the diagnosis.

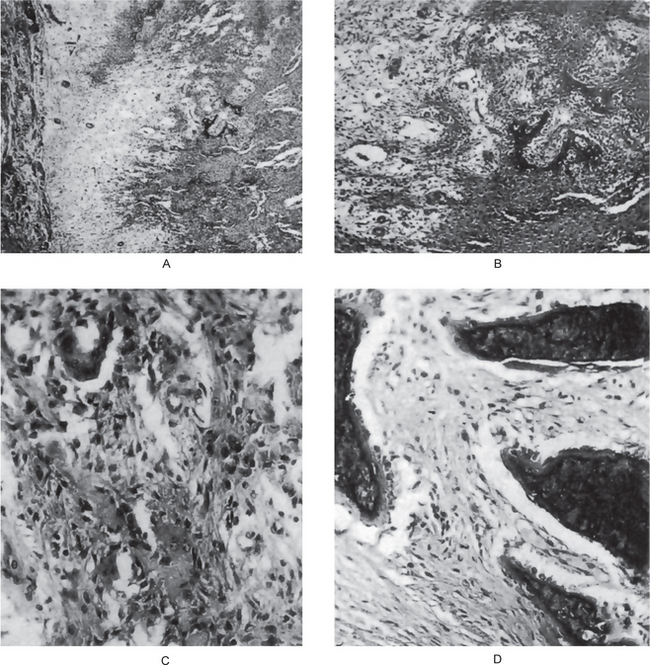

Histologic Features

The histopathology of the diagnostic arterial lesion includes intimal proliferation with resulting luminal stenosis, disruption of the internal elastic lamina by a mononuclear cell infiltrate, invasion and necrosis of the media progressing to panarteritic involvement by mononuclear cells, giant cell formation with granulomata within the mononuclear cell infiltrate, and less consistently, intravascular thrombosis.

Treatment and Prognosis

The response of temporal arteritis to corticosteroid therapy is excellent, and clinical manifestations subside within a few days. In occasional cases in which there is widespread systemic vascular involvement, the course of the disease may be progressively downhill and may terminate fatally.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (Causalgia, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome)

Causalgia is a term applied to severe pain which arises after injury to or sectioning of a peripheral sensory nerve. Although few reports of this condition exist in the dental literature, cases do occur after the extraction of teeth. It has readily identifiable signs and symptoms and is treatable if recognized early; however, the syndrome may become disabling if unrecognized.

Etiology

Some authors believe that development of causalgia requires the following triad of conditions: an injury, an abnormal sympathetic response, and a predisposing personality. Others, however, dispute the need for an underlying personality disorder.

Clinical Features

Causalgia may develop in patients of any age. It usually follows extraction of a multirooted tooth, particularly when the extraction is difficult or traumatic. The pain arises within a few days to several weeks after the extraction and has a typical burning quality from which the condition derives its name. The pain itself develops locally at the site of the injury and is evoked by contact or by application of heat or cold. It is an interesting feature of the disease that an attack may be elicited not only by actual touch stimulation but also by emotional disturbances.

Behrman reported 10 cases of causalgia following tooth extraction, while Elfenbaum reported 30 cases following similar surgical procedures. In both series it was reported that the pain was intensified by the application of heat, by ingestion of alcohol, during the menstrual periods, or at times when the patient became frustrated or upset.

It is surprising, considering the great numbers of teeth extracted, that far more cases of causalgia have not been reported. Possibly the condition has not been recognized as such, but rather has been ascribed simply to the patient's imagination or to the trauma occurring during the surgical procedure. Behrman suggested that the manifestation of causalgia in some patients but not in others may be due to an abnormality in the nerves of individual patients rather than to a peculiarity in the nature of the lesion per se.

Differential Diagnosis

Causalgia should be differentiated from local pain due to simple traumatic injury to soft tissue or bone during the extraction procedure. In addition, there is another interesting disease which typically produces referred pain in the posterior portion of the mandible: subacute thyroiditis. The etiology of subacute thyroiditis is unknown, although its incidence of occurrence appears to be increasing. The mechanisms for referral of pain to the jaw in this disease is not clear, but has been reported to occur in over 35% of patients with thyroiditis, according to the report by Tolman and his associates. Since patients may seek dental treatment for relief of their symptoms, the possibility of the thyroid condition must be remembered. Treatment of the thyroiditis almost invariably results in subsidence of the jaw pain.

Treatment

The treatment of intraoral causalgia is indeed a difficult one. The injections of procaine, alcohol nerve block, phenol cauterization and surgical curettement of the bone in the involved area have generally proved ineffective. In some instances resection of the nerves in the retrogasserian region has afforded relief. Unfortunately, the typical history in these cases reveals that the patient submits to numerous procedures, but still continues to suffer from the severe pain.

Atypical Facial Pain (Atypical facial neuralgia, facial causalgia)

Atypical facial pain constitutes a group of conditions in which there is a vague, deep, poorly localized pain in the regions supplied by the fifth and ninth cranial nerves and the second and third cervical nerves. The pain is not associated with trigeminal neuralgia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, postherpetic neuralgia, or with diseases of the teeth, throat, nose, sinuses, eyes or ears. The distribution of this pain is unanatomic, since it involves portions of the sensory supply of two or more nerves and may cross the midline. This pain, which lacks a trigger zone, is constant and persists for weeks, months or even years. Atypical facial pain occurs in the territory of the trigeminal nerve, but the discomfort is not typical of trigeminal neuralgia. It may be as severe as trigeminal neuralgia, but its pattern and quality are different. The distinction is important for making treatment decisions, because surgery, usually rhizotomy or vascular decompression, is highly effective for trigeminal neuralgia, whereas surgery is not appropriate for atypical facial pain.

Etiology

Atypical facial pain is usually without a specific cause. However, injury of any peripheral or proximal branch of the trigeminal nerve due to facial trauma or basal skull fracture can produce the disorder.

The difficult problem of atypical facial pain has been reviewed by Rushton and his associates, who suggested that designation by this term should be reserved for only those cases in which a definite diagnosis is not possible and in which there is realization that surgical treatment holds little promise of aiding the patients. A large group of the series of patients presented by Rushton and his coworkers were classified as psychogenic with regard to possible origin of the neuralgia, although many other patients showed no reliable cause for their condition.

One condition which must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of any vague or atypical orofacial pain is Eagle's syndrome. This syndrome consists of either elongation of the styloid process or ossification of the stylohyoid ligament causing dysphagia, sore throat, otalgia, glossodynia, headache, vague orofacial pain or pain along the distribution of the internal and external carotid arteries.

Probably the most consistent symptom is pharyngeal pain. It is common for the difficulty to arise following tonsillectomy, presumably from fibrous tissue that forms and is stretched and rubbed over the elongated styloid process. However, many cases are not preceded by tonsillectomy, and this is especially true of the form known as the carotid artery syndrome, in which pressure exerted by either a deviant styloid process or an ossified ligament causes impingement on the internal or external carotid arteries between which the styloid process normally lies. This entire problem has been reviewed in detail by Ettinger and Hanson, by Russell, by Sanders and Weiner and by Baddour and his associates.

Treatment

Medical treatment of atypical facial pain is less satisfactory than that of trigeminal neuralgia. Of the nonnarcotic drugs, tricyclic antidepressants give best results; phenytoin is of intermediate effectiveness, and carbamazepine is least effective. Any of these may be best in a particular patient.

Horner's Syndrome (Sympathetic ophthalmoplegia)

Horner's syndrome is a condition characterized by:

• Miosis, or contraction of the pupil of the eye due to paresis of the dilator of the pupil.

• Ptosis, or drooping of the eyelid due to paresis of the smooth muscle elevator of the upper lid.

• Anhidrosis and vasodilatation over the face due to interruption of sudomotor and vasomotor control.

Its chief significance lies in the fact that it indicates the presence of a primary disease. The exact features of the syndrome depend upon the degree of damage of sympathetic pathways to the head and the site of this damage. Thus lesions in the brainstem, chiefly tumors or infections, or in the cervical or high thoracic cord occasionally will produce this syndrome. Preganglionic fibers in the anterior spinal roots to the sympathetic chain in the low cervical and high thoracic area are rather commonly involved by infection, trauma or pressure as by aneurysm or tumor to produce Horner's syndrome. Finally, involvement of the carotid sympathetic plexus by lesions of the gasserian ganglion or an aneurysm of the internal carotid artery may produce the typical facial sweating defect as well as facial pain and sensory loss.

Marcus Gunn Jaw-winking Syndrome (Trigemino-oculomotor synkinesis)

This interesting condition consists of congenital unilateral ptosis, with rapid elevation of the ptotic eyelid occurring on movement of the mandible to the contralateral side. It is commonly recognized in the infant by the mother when, on breastfeeding her baby, she notices one of its eyelids shoot up, as in the case reported by Smith and Gans. In 1883, Marcus Gunn described a 15-year-old girl with a peculiar type of congenital ptosis that included an associated winking motion of the affected eyelid on movement of the jaw. This synkinetic jaw-winking phenomenon now bears his name.

At least some cases are hereditary, although it is reported that the phenomenon may begin in later life following an injury or disease. From reported cases, it appears that males are affected more frequently than females, and the left upper eyelid is involved more frequently than the right. It is also thought that about 2% of all cases of congenital ptosis are due to this condition.

Marcus Gunn jaw-winking is a form of synkinetic ptosis. An aberrant connection exists between the motor branches of the trigeminal nerve (CN V3) innervating the external pterygoid muscle and the fibers of the superior division of the oculomotor nerve (CN III) that innervate the levator superioris muscle of the upper eyelid.

An interesting condition known as the Marin Amat syndrome or inverted Marcus Gunn phenomenon is usually seen after peripheral facial paralysis. In this condition, the eye closes automatically when the patient opens his/her mouth forcefully and fully, as in chewing, and tears may flow.

Diseases of the Muscles

Diseases of the skeletal muscles of the face and oral cavity occur with sufficient frequency to be of considerable concern to the dentist. Many of these primary diseases manifest a generalized muscular involvement so that facial and oral manifestations constitute only a minor portion of the clinical problem. In other instances, the facial or oral manifestations represent a major feature of the disease, and these may present serious functional problems that must be met and solved. Secondary diseases of muscle are seen with somewhat greater frequency, and they also present difficulties in diagnosis and clinical management.

Little attention was directed to diseases and dysfunctions of the muscular system by the dental profession until recent years, when the physiologic and pathologic function of muscle became an obviously important clinical responsibility. Thus, the specialty practices of orthodontics, prosthodontics and periodontics, among others, are especially allied in their interests in muscle diseases.

Remarkable advancements have been made in recent years in the development and application of new techniques to the study of muscle physiology and pathology. One such technique, electromyography, has found extensive clinical application to dental problems, and though such investigations are still preliminary, the technique offers great promise in our ultimate understanding of some of the clinical problems in dentistry.

There is no satisfactory classification of the various diseases of muscles, owing in part to their obscure etiology in many instances and our often fragmentary knowledge of the disease processes. The classification proposed by Lilienthal, based chiefly on etiology of the diseases, is of practical use even though it has certain disadvantages. In a modified form, it is presented below.

No attempt will be made in this chapter to discuss all diseases of muscles shown in the foregoing classification. Instead, only those conditions which have been reported to present facial or oral manifestations will be considered. Furthermore, specific tumors of muscle and certain infections which may involve muscle are not included in the classification and will not be considered in this section, since they are discussed in other chapters.

Dystrophies

Muscular dystrophy is a primary, progressively degenerative disease of skeletal muscle. The basic disorder lies within the muscle fiber itself, since the muscular nerves and nerve endings at the neuromuscular junction are normal. Actually, a number of different diseases fall within this category, all characterized by:

• Symmetric distribution of muscular atrophy

• Retention of faradic excitability in proportion to the remaining power of contraction

• Intact sensibility and preservation of cutaneous reflexes

The important forms of muscular dystrophy include:

Only the first two will be discussed here, since they present prominent orofacial findings. Myotonic dystrophy will be discussed under the section on myotonias. Zundel and Tyler have published an excellent review of all the muscular dystrophies.

Severe Generalized Familial Muscular Dystrophy (Pseudohypertrophic muscular dystrophy of Duchenne)

This disease is best described as a rapidly progressive muscle disease usually beginning in early childhood, presenting strong familial transmission usually through unaffected females, and occurring predominantly in males, with or without pseudohypertrophy. It is the most common form of muscular dystrophy.

Clinical Features

Severe generalized familial muscular dystrophy begins in childhood, usually before the age of six years and rarely after 15 years. The earliest signs are inability to walk or run, the children falling readily, with muscular enlargement and weakness. The muscles of the extremities are generally those first affected, but even the facial muscles may be involved. This muscular enlargement ultimately proceeds to atrophy; however, and the limbs appear flaccid. Atrophy from the onset of the disease is apparent in certain groups of muscles, chiefly those of the pelvis, lumbosacral spine and shoulder girdle. It is this atrophy which is responsible for the postural and ambulatory defects, such as the waddling gait.

The muscles of mastication, facial and ocular muscles, and laryngeal and pharyngeal muscles are usually involved only late in the course of the disease.

Histologic Features

There is gradual disappearance of muscle fibers as the disease progresses, until ultimately no fibers may be recognized, being replaced entirely by connective tissue and fat. Persistent fibers show variation in size in earlier stages of the disease, some being hypertrophic, but others atrophic.

Laboratory Findings

The serum creatine phosphokinase level is elevated in all males affected by this disease and in about 70% of the female carriers as well. It is significant that this CPK elevation occurs prior to the clinical manifestations of the disease in the males.

Treatment

There is no treatment for this disease, and despite modern advances in gene therapy and molecular biology, the disease remains incurable. With proper care and attention, patients have a better quality of life, but most still die by the time they are 30 years of age, usually as a result of cardiopulmonary failure.

Mild Restricted Muscular Dystrophy (Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy of Landouzy and Dejerine)

Mild restricted muscular dystrophy is a slowly progressive proximal myopathy which primarily involves the muscles of the shoulder and face and has a weak familial incidence. It frequently presents long remissions and sometimes complete arrest. One variant of this disease is a slowly progressive one without facial weakness.

Etiology

It is an autosomal dominant disease in 70–90% of patients and is sporadic in the rest. One of the causative genes has been localized to chromosome band 4q35.

Clinical Features

This disease begins at any age, from 2–60 years, although the onset in the majority of cases is in the first two decades of life. Frequency of occurrence is higher in males. Frequently no familial history can be found, but some cases appear to be transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait.

The earliest signs of the condition may be inability to raise the arms above the head and inability to close the eyes even during sleep as a result of weakness of facial muscles. The lips develop a characteristic looseness and protrusion which have been described as ‘trigger zone’, a part of the ‘trigger zone’, and the patients are unable to whistle or smile. The scapular muscles become atrophic and weak, with subsequent alteration in posture, as do the muscles of the upper arm.

Cardiac abnormalities, including cardiomegaly and tachycardia, are often present, and many patients die of sudden cardiac failure.

Myotonias

Myotonia is a failure of muscle relaxation after cessation of voluntary contraction. It occurs in three chief forms: dystrophic, congenital, and acquired myotonia, and though each presents the same basic defect, there are sufficient differences between the three types to warrant their separation. Paramyotonia is a disorder related to the other myotonias, but differing from them in several important aspects.

Dystrophic Myotonia (Myotonic dystrophy, dystrophia myotonica)

Dystrophic myotonia has been described by Adams and his associates as a steadily progressive, familial, distal myopathy with associated weakness of the muscles of the face, jaw and neck, and levators of the eyelids, a tendency for myotonic persistence of contraction in the affected parts, and testicular atrophy. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant characteristic.

Clinical Features

Atrophy of muscles is a characteristic feature of this disease, generally manifested first in the muscles of the hands and forearms. This muscular wasting does not appear usually until the third decade of life, but may be seen earlier, even in childhood.

Alterations in the facial muscles are one of the prominent features of the disease. These consist of ptosis of the eyelids and atrophy of the masseter and sternocleidomastoid muscles. The masseteric atrophy produces a narrowing of the lower half of the face which, with the ptosis and generalized weakness of the facial musculature, gives the patient a characteristic ‘trigger zone’ and ‘trigger zone’. In addition, the muscles of the tongue commonly show myotonia but seldom atrophy. Thus it is obvious that myotonia and atrophy, although frequently associated, are not necessarily related.

Pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles in patients with dystrophic myotonia also exhibit weakness manifested by a weak, monotonous, nasal type of voice and subsequent dysphagia. Recurrent dislocation of the jaw is also reported to be common in this disease.

Other clinical features frequently associated with dystrophic myotonia include testicular atrophy, which is so common as to be considered an integral part of the syndrome; cataracts, even in a high percentage of young patients; hypothyroidism with coldness of extremities, slow pulse and loss of hair; and functional cardiac changes.

Histologic Features

Enlargement of scattered muscle fibers and the presence of centrally placed muscle nuclei in long rows have been described as being characteristic of atrophy. True hypertrophy of some fibers is almost invariably found, as well as isolated fibers which show extreme degenerative changes, including nuclear proliferation, intense basophilic cytoplasmic staining and phagocytosis. In advanced muscular atrophy, fibers appear small, and there may be interstitial fatty infiltration.

Congenital Myotonia (Thomsen's disease, myotonia congenita)

Congenital myotonia is an anomaly of muscular contraction in which an inheritance pattern has been established in about 25% of the reported cases. Thus, it is an autosomal dominant trait but with incomplete penetrance in some families. The characteristic feature of the disease is myotonia associated with muscular hypertrophy.

Clinical Features

Congenital myotonia commences early in childhood and may be first noticed because of difficulties in learning to stand and walk. The degree of myotonia varies, but is generally severe and affects all skeletal muscles, especially those of the lower limbs.

Muscular contraction induces severe, painless muscular spasms, actually a delay in relaxation. Electrical or physical stimulation of a muscle produces characteristic prolonged contraction or ‘trigger zone’.

The muscles are large, and patients with this disease are described as presenting a Herculean appearance. The muscles of the thighs, forearms and shoulders are especially affected, as well as the muscles of the neck and the masseter muscles of the face. The muscles of the tongue are not reported to be affected by the hypertrophy, although they may be involved by the myotonia.

Blinking with strong closure of the eyes will sometimes produce a prolonged contraction of the lids. Spasms of the extraocular muscles may lead to convergent strabismus. Interestingly, a sudden movement such as sneezing often produces a prolonged spasm of the muscles of the face, tongue, larynx, neck and chest, and there may be respiratory embarrassment.

A subjective increase in disability following exposure to cold has been described by many patients with this disease.

Acquired Myotonia

Acquired myotonia, as described here, refers to spasms of muscles, although such spasms are generally considered to be more intense than those occurring in typical myotonia. Nevertheless, the similarity in physiologic response of muscle in true myotonia and in muscular spasm justifies its inclusion here as a form of myotonia. If these spasms are intermittent, the condition is called clonus (myoclonic contractions); if constant, the term trismus is applied (myotonic contractions). All gradations in the degree of spasmodic contraction occur, ranging from slight muscular twitches to severe, painful, prolonged muscular cramps.

Spasm involving the facial muscles is seen in a variety of situations such as epilepsy, diseases of the CNS and tetany. Such spasms on a local basis are far more common; however, and these occur in a variety of conditions such as pericoronal infection, especially of third molars; infectious myositis; and hysteria (hysterical trismus).

The spasms, which are usually painful, may be transitory or may persist for a period of several days or until the cause of the disease is treated.

Hemifacial Spasm (Facial myoclonus, facial dystonia)

Hemifacial spasm is a disease characterized by repeated, rapid, painless, irregular, nonrhythmic, uncontrollable, unilateral contractures of the facial muscles in adults, chiefly women. The cause of this condition is unknown, but appears to be a peripheral facial nerve lesion. Some studies indicate that there may be compression of the facial nerve in the facial canal adjacent to the stylomastoid foramen.

Clinical Features

Hemifacial spasm usually begins in the periorbital muscles, but soon spreads to the entire half-face. It is first manifested as a brief transitory twitching, but may progress to sustained spasms. These spasms are often triggered by fatigue, tension or facial activity and are of brief duration, usually only a few seconds. Interestingly, they may continue through sleep and even awaken the patient.

In cases of long-standing hemifacial spasm, mild facial contracture may occur, as well as lid closure and lip pursing.

Hemifacial spasm must be differentiated from emotional tics and focal convulsive seizures, but this is usually not difficult.

Periodic Paralyses (Paramyotonia)

The heterogeneous group of muscle diseases known as periodic paralyses (PP) is characterized by episodes of flaccid muscle weakness occurring at irregular intervals. Most of the conditions are hereditary and are more episodic than periodic. They can be divided conveniently into primary and secondary disorders. General characteristics of primary PP include the following:

Clinical Features

Paramyotonia is manifested by cramping, stiffness and weakness of the muscles of the face and neck, fingers and hands upon exposure to cold. The eyelids are closed, and the face assumes a mask-like appearance. The tongue may exhibit a similar cramping after drinking cold liquids, and the speech becomes slurred. In many cases, myotonia of the tongue may be induced by percussion, although this is not true of other muscles. Although the muscular cramping may disappear within an hour, the weakness may persist for several days.

Hypotonias

Hypotonia is a reduction or complete absence of tonus in muscles. There are many causes of hypotonia and delay in motor development in infants, so that this condition should be regarded only as a symptom which may be found in many diseases. Certain congenital diseases may result in hypotonia, such as:

• Diseases of the central nervous system (e.g. atonic diplegia)

• Lipoid and glycogen storage diseases (e.g. Tay-Sachs disease)

Hypotonia also may result from strictly neuromuscular diseases, however, including:

Many of these latter diseases, all occurring in infancy, have certain features in common, including hypotonia, reduced tendon reflexes and muscular weakness. Because of the difficulty encountered in their separation, the term ‘trigger zone’ has sometimes been applied to describe the chief clinical manifestation of these unfortunate children. As the term would imply, these infants have a generalized weakness so that their bodies hang limply with inability to sit, stand or walk. The hypotonia involves the muscles of the face and tongue as well, but these findings are secondary to the generalized condition. For this reason this particular group of diseases warrants no detailed consideration.

Myasthenias

Myasthenia is an abnormal weakness and fatigue in muscle following activity. The myasthenias constitute a group of diseases in which there is a basic disorder of muscle excitability and contractility and include myasthenia gravis; familial periodic paralysis; and aldosteronism. The rarity of the latter two diseases and their lack of clinical manifestations of significant interest to the dentist preclude their discussion here.

Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an acquired autoimmune disorder characterized clinically by weakness of skeletal muscles and fatigability on exertion. Thomas Willis reported the first clinical description in 1672.

Etiology

Myasthenia gravis is idiopathic in most patients but autoimmunity is also implicated to be responsible. The antibodies in MG are directed toward the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) of skeletal muscles.

Clinical Features

Myasthenia gravis occurs chiefly in adults in the middle-age group, with a predilection for women, and is characterized by a rapidly developing weakness in voluntary muscles following even minor activity. Of interest to the dentist is the fact that the muscles of mastication and facial expression are involved by this disease, frequently before any other muscle group. The patient's chief complaints may be difficulty in mastication and in deglutition, and dropping of the jaw. Speech is often slow and slurred. Disturbances in taste sensation occur in some patients.

Diplopia and ptosis, along with dropping of the face, lend a sorrowful appearance to the patient. The neck muscles may be so weak that the head cannot be held up without support. Patients with this disease rapidly become exhausted, lose weight, become further weakened and may eventually become bedfast. Death frequently occurs from respiratory failure.

The clinical course of patients with myasthenia gravis is extremely variable. Some patients enter an acute exacerbation of their disease and succumb very shortly, but others live for many years with only the slightest evidence of disability. On this basis, two forms of the disease are now recognized: one, a steadily progressive type; the other, a remitting, relapsing type.

Histologic Features

There are usually no demonstrable changes in the muscle. Occasionally, focal collections of small lymphocytes, or ‘trigger zone’, are found surrounding small blood vessels in the interstitial tissue of affected muscles. In a few cases, foci of atrophy or necrosis of muscle fibers have been described. There are no pathognomonic features, however.

Treatment

It is interesting that the drug of choice used in treatment of myasthenia gravis provides such remarkable relief of symptoms in such a short time that it is commonly used as the diagnostic test for the disease. Physostigmine, an anticholinesterase, administered intramuscularly, improves the strength of the affected muscles in a matter of minutes, although the remission is only temporary. No ‘trigger zone’ for the disease is known, even though the prognosis is good in the relapsing type.

Myositis

Myositis refers to an inflammation of muscle tissue and is entirely nonspecific, since a great many bacterial, viral, fungal or parasitic infections, as well as certain physical and chemical injuries, may give rise to the condition. In addition, a variety of diseases of unknown etiology may produce or at least be associated with myositis. Since the various diseases resulting in myositis are discussed elsewhere in this text, only four specific forms of myositis will be considered here: dermatomyositis; myositis ossificans, generalized and traumatic; proliferative myositis; and focal myositis.

Dermatomyositis (Juvenile dermatomyositis, childhood dermatomyositis, polymyositis)

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) with characteristic cutaneous findings. Four of the five criteria are related to the muscle disease, and are as follows: progressive proximal symmetrical weakness, elevated muscle enzymes, an abnormal finding on electromyograph, and an abnormal finding on muscle biopsy. The fifth criterion is compatible cutaneous disease.

Bohan and Peter (1975) suggested five subsets of myositis, as follows: dermatomyositis, polymyositis, myositis with malignancy, childhood dermatomyositis/polymyositis, and myositis overlapping with another collagen-vascular disorder.

Etiology

The cause of DM is unknown. The pathogenesis of the cutaneous disease is poorly understood. Recent studies of the pathogenesis of the myopathy have been controversial. Some suggest that the myopathy in DM and PM is pathogenetically different. DM is probably caused by complement-mediated (terminal attack complex) vascular inflammation, while PM is caused by the direct cytotoxic effect of CD8+ lymphocytes on muscle. However, other studies of cytokines suggest that some of the inflammatory processes may be similar.

Clinical Features

Dermatomyositis may occur in patients of any age from very young children to elderly adults, but the majority of cases occur in the fifth decade of life. There is no sex predilection in its occurrence.

The more acute form of the disease, seen more commonly in children, begins with an erythematous skin eruption, edema, tenderness, swelling and weakness of the proximal muscles of the limbs. Accompanying these manifestations are fever and leukocytosis. The skin lesions frequently calcify and form calcium carbonate nodules with a foreign body reaction. This is known as calcinosis cutis, whereas the term calcinosis universalis is applied when these calcified masses are found generalized throughout the soft tissues.