Benign and Malignant Tumors of the Oral Cavity

. Benign Tumors of Epithelial Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Epithelial Tissue Origin

. ‘Premalignant’ Lesions/Conditions of Epithelial Tissue Origin

. ‘Premalignant’ Lesions/Conditions of Epithelial Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of the Epithelial Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of the Epithelial Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Connective Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Connective Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of Connective Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of Connective Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Muscle Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Muscle Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of Muscle Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of Muscle Tissue Origin

The study of tumors of the oral cavity and adjacent structures constitutes an important phase of dentistry because of the role which the dentist plays in the diagnosis and treatment of these lesions. Although tumors constitute only a small number of the pathologic conditions seen by the dentist, they are of great significance since they have the potential ability to jeopardize the health and longevity of the patient. Many of the great variety of oral tumors will seldom be seen by the general practitioner of dentistry. Yet, it is of utmost importance that he/she be familiar with them so that when one does present itself, he/she may either institute appropriate treatment or refer the patient to the proper therapist.

A tumor, by definition, is simply a swelling of the tissue in the strict sense, the word does not imply a neoplastic process. Many of the lesions to be discussed in this chapter are called tumors only because they are manifested as swellings; they are in no way actually related to true neoplasms.

Neoplasia is a poorly understood biological phenomenon which, in some instances, cannot be clearly differentiated from other processes or tissue reactions. A neoplasm can be defined as an abnormal mass of tissue, the growth of which exceeds and is uncoordinated with that of the normal tissues and persists in the same excessive manner after cessation of the stimuli which evoked the change (Willis 1952).

Benign Tumors of Epithelial Tissue Origin

Squamous Papilloma

The oral squamous papillomas are seemed to be associated with papilloma virus, the one commonly incriminated as causative in skin warts. It is the fourth most common oral mucosal mass and is found in 4 of every 1,000 and accounts for 3–4% of all biopsied oral soft tissue lesions.

The HPV types 6 and 11, commonly associated with squamous papillomas, failed to be demonstrated in oral malignancies as well as potentially malignant oral lesions. Even though all HPV lesions are infective, the squamous papilloma appears to have an extremely low virulence and infectivity rate; it does not seem to be contagious.

Since the squamous papilloma may be clinically and microscopically indistinguishable from verruca vulgaris, the virus-induced focal papillary hyperplasia of the epidermis, it is briefly discussed in this section.

Clinical Features

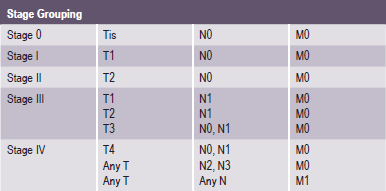

The papilloma is an exophytic growth made up of numerous, small finger like projections which result in a lesion with a roughened, verrucous or ‘cauliflower like’ surface. It is nearly always a well circumscribed pedunculated tumor, occasionally sessile. It is painless, usually white but sometimes pink in color. Intraorally it is found most commonly on the tongue, lips, buccal mucosa, gingiva and palate, particularly that area adjacent to the uvula (Fig. 2-1). The majority of papillomas are only a few millimeters in diameter, but lesions may be encountered which measure several centimeters. These growths occur at any age and are seen even in young children. A series of 110 cases has been reported by Greer and Goldman, while a series of 464 cases has been studied by Abbey and his coworkers; this is somewhat indicative of the prevalent nature of the lesion.

Figure 2-1 Papilloma. Large (A) and small (B) papillomas of the tongue illustrate the variation in clinical appearance of the lesion. The photomicrograph (C) illustrates the many finger like projections (1), each containing a thin, central connective tissue core (2), of which the lesion is composed.

The common wart or verruca vulgaris, is a frequent tumor of the skin analogous to the oral papilloma. It is uncommon on oral mucous membranes but extremely common on the skin. The associated viruses in verruca are the subtypes HPV-2, HPV-4 and HPV-40. Clinically it shows pointed or verruciform surface projections, a very narrow stalk, appears white due to considerable surface keratin, and presents as multiple or clustered individual lesions. It enlarges rapidly to its maximum size, seldom achieving more than 5 mm in greatest diameter. Verruca vulgaris is contagious and capable of spreading to other parts of an affected person’s skin or membranes by way of autoinoculation. Lesions that are histologically identical to the verruca vulgaris of the skin are frequently found on the lips and occasionally intraorally (Fig. 2-2). These are often seen in patients with verrucae on the hands or fingers, and the oral lesions appear to arise through autoinoculation by finger sucking or fingernail biting.

Figure 2-2 Verruca vulgaris. These verrucae of the lips occurred in a girl, with similar lesions on the fingers, who habitually bit her fingernails (Courtesy of Dr Paul E Starkey).

Papilloma like or papillomatous lesions as well as ‘pebbly’ lesions and fibromas of various sites in the oral cavity are recognized as one of the many manifestations of the multiple hamartoma and neoplasia syndrome (Cowden’s syndrome). This is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by facial trichilemmomas associated with the gastrointestinal tract, the thyroid, CNS and musculoskeletal abnormalities as well as oral lesions. It is also considered a cutaneous marker of breast cancer.

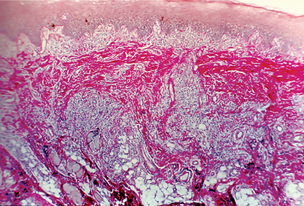

Histologic Features

The microscopic appearance of the papilloma is characteristic and consists of many long, thin, finger-like projections extending above the surface of the mucosa, each made up of a continuous layer of stratified squamous epithelium and containing a thin, central connective tissue core which supports the nutrient blood vessels (Fig. 2-1 C). Some papillomas exhibit hyperkeratosis, although this finding is probably secondary to the location of the lesion and the amount of trauma or frictional irritation to which it has been subjected. The essential feature is a proliferation of the spinous cells in a papillary pattern; the connective tissue present is supportive stroma only and is not considered a part of the neoplastic element. Occasional papillomas demonstrate pronounced basilar hyperplasia and mild mitotic activity which should not be mistaken for mild epithelial dysplasia. Koilocytes (HPV altered epithelial cells with perinuclear clear spaces and nuclear pyknosis) may or may not be found in the superficial layers of the epithelium. The presence of chronic inflammatory cells may be variably noted in the connective tissue.

Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment of the papilloma consists of excision, including the base of the mucosa into which the pedicle or stalk inserts. Removal should never be accomplished by an incision through the pedicle. If the tumor is properly excised, recurrence is rare. The possibility of malignant degeneration in the oral papilloma is quite unlikely, although fixation of the base or induration of the deeper tissues should always be viewed with some suspicion.

Intraoral verruca vulgaris is also treated effectively by conservative surgical excision or curettage, but liquid nitrogen cryotherapy and topical application of keratinolytic agents (usually containing salicylic acid and lactic acid) are also effective. Recurrence is seen in a small proportion of treated cases.

Squamous Acanthoma

The squamous acanthoma is an uncommon lesion which probably represents a reactive phenomenon of the epithelium rather than a true neoplasm. It bears no known relationship to the clear cell acanthoma, which occurs with considerable frequency on the skin and may also be found on the lips, as in the two cases reported by Weitzner.

The squamous acanthoma has no distinctive clinical appearance by which it may be identified or even suspected, and may occur at virtually any site on the oral mucosa, usually in older adults. It is generally described as a small flat or elevated, white, sessile or pedunculated lesion on the mucosa. The lesion is histologically distinctive and consists of a well-demarcated elevated and/or umbilicated epithelial proliferation with a markedly thickened layer of orthokeratin and underlying spinous layer of cells. Tomich and Shafer, who originally described this lesion, postulated that it was caused by trauma and developed its characteristic morphology through a series of epithelial alterations beginning with a localized pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. It is not known to recur after excision.

Keratoacanthoma (Self-healing carcinoma, molluscum pseudocarcinomatosum, molluscum sebaceum, verrucoma)

A lesion which clinically and pathologically resembles squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma is a relatively common low-grade malignancy that originates in the pilosebaceous glands. It is considered to be a variant of invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

The definite cause of this lesion remains unclear but similarity in epidemiologic data with squamous cell carcinoma and Bowen disease supports sunlight as an important etiologic factor. Industrial workers exposed to pitch and tar have been well established as having a higher incidence of keratoacanthoma, thus chemical carcinogens may be one of the etiologic factors. Trauma, human papilloma virus (specifically types 9, 11, 13, 16, 18, 24, 25, 33, 37, and 57), genetic factors and immunocompromised status also have been implicated as etiologic factors. Recent studies identified that up to one-third of keratoacanthomas harbor chromosomal aberrations such as gains on 8q, 1p, and 9q with deletions on 3p, 9p, 19p, and 19q. One other report identified a 46, XY, t (2;8) (p13; p23) chromosomal aberration.

Clinical Features

Keratoacanthoma has been reported in all age groups, but incidence increases with age. It occurs twice as frequently in men as in women and is less common in darker skinned individuals. Most keratoacanthomas occur on sun-exposed areas. The face, neck, and dorsum of the upper extremities are common sites; 8.1% of the cases occurred on the lips and the vermilion border of both the upper and lower lip are affected with equal frequency. Intraoral lesions are quite uncommon, a total of four cases were reviewed by Freedman and his associates.

Lesions typically are solitary and begin as firm, round, skin-colored or reddish papules that rapidly progress to dome-shaped nodules with a smooth shiny surface and a central crateriform ulceration or keratin plug that may project like a horn. The lesion appears as an elevated umbilicated or crateriform one with a depressed central core or plug (Fig. 2-3). It is seldom over 1.0 to 1.5 cm in diameter. The lesion is often painful and regional lymphadenopathy may be present.

Figure 2-3 Keratoacanthoma. This small keratoacanthoma of the lip illustrates the typical elevated, umbilicated appearance of the lesion (Courtesy of Dr Charles E Huttom).

The clinical course of the lesion is one of its unusual aspects. It begins as a small, firm nodule that develops to full size over a period of four to eight weeks, persists as a static lesion for another four to eight weeks, then undergoes spontaneous regression over the next six-to eight-week period by expulsion of the keratin core with resorption of the mass. However, lesions with an overall duration of as long as two years have been reported. Recurrence is rare.

The differential diagnoses include actinic keratosis, molluscum contagiosum, Muir-Torre syndrome, squamous cell carcinoma, and verrucous carcinoma.

Histologic Findings

The lesion consists of hyperplastic squamous epithelium growing into the underlying connective tissue. The surface is covered by a thickened layer of parakeratin or orthokeratin with central plugging. The epithelial cells do not usually show atypia but occasionally dysplastic features are found. At the deep leading margin of the tumor, islands of epithelium often appear to be invading and frequently this area cannot be differentiated from epidermoid carcinoma. Lapins and Helwig, among others, have also reported that the keratoacanthoma on occasion may invade perineural spaces, but this does not adversely affect the biologic behavior of the lesion; neither can it be used as a distinguishing characteristic between keratoacanthoma and epidermoid carcinoma. Pseud-ocarcinomatous infiltration typically presents a smooth, regular, well-demarcated front that does not extend beyond the level of the sweat glands. The connective tissue in the area shows chronic inflammatory cell infiltration. The most characteristic feature of the lesion is found at the margins where the normal adjacent epithelium is elevated towards the central portion of the crater; then an abrupt change in the normal epithelium occurs as the hyperplastic acanthotic epithelium is reached. For this reason, the diagnosis may be impossible if the adjacent border of the specimen is not included in the biopsy.

The term squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma type has been introduced for otherwise classic keratoacanthomas that reveal a peripheral zone formed by squamous cells with atypical mitotic figures, hyperchromatic nuclei, and loss of polarity to some degree. These marginal cells also may penetrate into surrounding tissue in a more aggressive pattern.

Treatment

The lesion is usually treated by surgical excision. Spontaneous regression does not occur in every case; where it has occurred, residual scar may be present. Prognosis is excellent following excisional surgery. Recurrent tumors may require more aggressive therapy. Patients with a history of keratoacanthoma should be followed for the development of new primary skin cancers (squamous cell carcinoma, in particular).

Oral Nevi (Oral melanocytic nevus, nevocellular nevus, mole, mucosal melanocytic nevi)

Categorized as hamartomas, developmental malformations, the nevi are benign proliferations of nevus cells in either epithelium or connective tissue. In 1943, Ackermann and Field have reported the first case of an oral nevus. King et al, adopted the less anatomically specific term, intramucosal nevus. Adult whites harbor this lesion rather commonly but intraoral lesions are much less common.

Nevi may also be classified as congenital or acquired (Buchner and Hansen). On the basis of the histologic location of the nevus cells, cutaneous acquired nevi can be classified into three categories:

• Junctional nevus—when nevus cells are limited to the basal cell layer of the epithelium

• Compound nevus—nevus cells are in the epidermis and dermis

• Intradermal nevus (common mole)—nests of nevus cells are entirely in the dermis.

Oral nevi follow the same classification where the term intradermal is replaced by intramucosal.

Oral acquired melanocytic nevi evolve through stages similar to those of nevi on the skin. Junctional nevi that are first noted in infants, children and young adults typically mature into compound nevi. Then, during later adulthood, the lesions mature into intramucosal nevi. As the nevus cells penetrate into the dermis, their pigmentation diminishes; approximately 15% of intramucosal nevi are nonpigmented.

The most common mucosal type is the intramucosal nevus, which accounts for more than one half of all reported oral nevi. The common blue nevus is the second most common type found in the oral cavity. The blue nevi is commoner in the mouth than in the skin; which account for 25–36% of all oral nevi, according to different studies. Junctional and compound nevi account for only 3–6% of all oral nevi.

Clinical Features

Ainsworth and her colleagues separate the congenital nevi of the skin into ‘small’ and ‘garment’ nevi. The ‘small’ nevi are greater than 1 cm in diameter and usually 3–5 cm. The ‘garment’ nevi are greater than 10 cm in diameter and can cover large areas of the skin. The congenital nevi occur in 1–2.5% of neonates and, with the passage of time, may change from flat, pale tan macules to elevated, verrucous, hairy lesions. Approximately 15% occur on the skin of the head and neck. Intraoral occurrence is extremely rare.

Acquired nevi are extremely common. They appear in about the eighth month of life and increase in number with age, apparently reaching their peak numerically in the late third decade of life. Clark has stated that the number of nevi which a person has is genetically determined. Interestingly, the number of nevi begin to decrease as one ages, so that elderly persons average far fewer nevi than younger adults.

The intradermal nevus (common mole) is one of the most common lesions of the skin, most persons exhibiting several, often dozens, scattered over the body. The common mole may be a smooth flat lesion or may be elevated above the surface; it may or may not exhibit brown pigmentation, and it often shows strands of hair growing from its surface (Fig. 2-4). This form of mole seldom occurs on the soles of the feet, the palms of the hands or the genitalia.

Figure 2-4 Pigmented cellular nevus. Typical examples of nevi of the skin (A) and palate (B) are illustrated.

The junctional nevus may appear clinically similar to the intradermal nevus, the distinction being chiefly histologic. It is extremely important; however, that a distinction be drawn, since the prognosis of the two lesions is different, as will be pointed out later.

The compound nevus is a lesion composed of two elements: an intradermal nevus and an overlying junctional nevus.

The spindle cell and/or epithelioid cell nevus (Spitz nevus) occurs chiefly in children, only about 15% appearing in adults, and may appear histologically similar to malignant melanoma in the adult. Seldom; however, does this lesion exhibit clinically malignant features. Essentially, this lesion is clinically benign, but histologically malignant. Weedon and Little have reviewed 211 cases of spindle cell and epithelioid cell nevi while Allen has reviewed 262 cases, and none of these authors have found any nevus of this type on a mucous membrane surface, including the oral cavity.

The blue nevus is a true mesodermal structure composed of dermal melanocytes which only rarely undergo malignant transformation. It occurs chiefly on the buttocks, on the dorsum of the feet and hands, on the face and occasionally on other areas. The majority of blue nevi are present at birth or appear in early childhood and persist unchanged throughout life. The lesion is smooth, exhibits hairs growing from its surface and varies in color from brown to blue or bluish black. Scofield reviewed this lesion in 1959 and reported two intraoral cases, the first recorded occurrence of the lesions in the mouth. Since then, numerous intraoral lesions have been reported.

Histologic variants of acquired nevi such as neural, balloon cell and halo nevi occur. Only the halo nevus is clinicopathologically distinctive. The neural and balloon cell nevi are histologic variants of intradermal or compound nevi.

Oral Manifestations

Eight-five percent of oral nevi are found in patients younger than 40 years. Oral nevi are found in all races and more frequently in whites, in whom 55% of reported oral nevi occurred. Approximately 23% of oral nevi occurred in black patients. Patients with junctional or compound nevi were relatively young; they were aged 22 and 24 years, respectively, whereas the mean age of patients with intramucosal nevi and blue nevi was 35 years and 38 years, respectively. Studies have revealed that oral mucosal nevi are slightly predominant in women rather than men. Oral nevi most commonly occur on the hard palate, with almost 40% presenting in that location. The second most common location is the buccal mucosa (20% of cases). Other common locations include the vermilion border of the lip and the labial mucosa. Roughly 10% of all types of oral nevi are found on the gingiva. Only one mucosal nevus has been reported on the tongue or floor of the mouth.

Most oral nevi are asymptomatic, and the lesions are usually detected as an incidental finding on routine dental examination. Nevi are often mistaken for melanotic macules, amalgam tattoos, physiologic ethnic pigmentation, smoker’s melanosis, or other vascular or pigmented lesions.

An aid in differential diagnosis is that melanotic macules and amalgam tattoos are usually flat while the majority of nevi elevate from the mucosal surface. Ethnic pigmentation is nearly always symmetric and rarely affects the surface topography or disturbs the normal stippling in the gingiva. Smoker’s melanosis involves only the anterior gingiva and most often occurs in women who smoke and take oral contraceptives. Vascular lesions can be mistaken for melanocytic proliferations; the former usually blanch with compression, and aspiration may be helpful in differentiating a nevus from a vascular process. Malignant melanoma is frequently associated with diffuse areas of pigmentation, possible ulceration, nodularity, variegation in color, and an irregular outline.

Approximately 85% of oral nevi are pigmented. Pigmentation usually varies from brown to black or blue. Nevi are well circumscribed, round, or oval, and are raised or slightly raised in 65–80% of cases. Approximately 15% of nevi are amelanotic. Many amelanocytic lesions appear as sessile growths that resemble fibromas or papillomas or excrescences of normal color.

The anatomic distribution of nevi closely follows its histologic type. Almost two-thirds of blue nevi occur in hard palate. Intramucosal nevi are distributed almost equally between the hard palate and buccal mucosa, with almost 25% in each location. Approximately 17% of intramucosal nevi are on the gingiva, 12% on the vermilion border of the lip, and almost 9% on the labial mucosa.

Histologic Features

The nevus cells are assumed to be derived from neural crest and their envisaged relationship with true melanocytes remains uncertain. Nevus cells are large ovoid, rounded, or spindle-shaped cells with pale cytoplasm; and may contain granules of melanin pigment in their cytoplasm. The nucleus is vesicular and lacks the dendritic processes typical of melanocytes. In addition, they either lack contact inhibition or lose it shortly after the proliferation process begins. Melanosomes are retained by nevus cells and are not transferred to adjacent keratinocytes. They tend to be grouped in sheets or cords which are called nest or thèque. Nevus cells also have the ability to migrate from the basal cell layer into the underlying connective tissue.

Multinucleated giant nevus cells are sometimes seen, but are of little prognostic significance. Mitotic figures are not common.

In the intradermal nevus, the nevus cells are situated within the connective tissue and are separated from the overlying epithelium by a well defined band of connective tissue. Thus, in the intradermal nevus, the nevus cells are not in contact with the surface epithelium (Fig. 2-5 A).

Figure 2-5 Pigmented cellular nevus. The intradermal nevus (A) demonstrates a thick band of connective tissue (1) separating the nevus cells from the overlying epithelium. In the compound nevus (B), the nevus cells are in contact with the overlying epithelium and are in the underlying connective tissue. The nevus cells are shown under high magniication (C), Pigmented cellular nevus—nevus cells are in contact with the overlying epithelium and appear to blend into the epithelium (D). (Courtesy of Dr Hari S,Noorul Islam College of Dental Science,Trivandrum )

In the junctional nevus, this zone of demarcation is absent, and the nevus cells contact and seem to blend into the surface epithelium. This overlying epithelium is usually thin and irregular and shows cells apparently crossing the junction and growing down into the connective tissue—the so-called abtropfung or ‘dropping off ’ effect. This ‘junctional activity’ has serious implications because junctional nevi have been known to undergo transformation into malignant melanomas (Fig. 2-5 D).

The compound nevus shows features of both the junctional and intradermal nevus. Nests of nevus cells are dropping off from the epidermis, while large nests of nevus cells are also present in the dermis (Fig. 2-5 B, C).

The spindle cell and/or epithelioid cell nevus is commonly composed of pleomorphic cells of three basic types: spindle cells, oval or ‘epithelioid’ cells, and both mononuclear and multinucleated giant cells. These are arranged in well-circumscribed sheets and there is generally considerable junctional activity.

The blue nevus is of two types: the common blue nevus and the cellular blue nevus. In the common blue nevus, elongated melanocytes with long branching dendritic processes lie in bundles, usually oriented parallel to the epidermis, in the middle and lower third of the dermis. There is no junctional activity. The melanocytes are typically packed with melanin granules, sometimes obscuring the nucleus, and these granules may extend into the dendritic processes. In the cellular blue nevus, an additional cell type is present: a large, round or spindle cell with a pale vacuolated cytoplasm. These cells commonly are arranged in an alveolar pattern.

Treatment and Prognosis

Since the acquired pigmented nevus is of such common occurrence, it would obviously be impossible to attempt to eradicate all such lesions. It has be-come customary to recommend removal of pigmented moles if they occur in areas which are irritated by clothing, such as at the belt or collar line, or if they suddenly begin to increase in size, deepen in color, or become ulcerated. Allen and Spitz have stated that it is fairly certain that trauma to an intradermal nevus will not induce malignancy. Whether simple trauma to a junctional nevus will produce malignancy is not known.

On the other hand, it is now well recognized that the congenital nevi have a great risk for transformation to malignant melanoma. Kaplan reported seven cases which were seen at the Stanford University Hospital and discussed 49 other cases. It is estimated that 14% of the large congenital nevi may undergo malignant transformation. Of particular interest is the occurrence of the B-K mole syndrome described by Clark and coworkers. This autosomal dominant condition is characterized by large pigmented nevi and a high risk for the development of melanoma. Its occurrence; however, has not been documented intraorally.

Surgical excision of all intraoral pigmented nevi is recommended as a prophylactic measure because of the constant chronic irritation of the mucosa in nearly all intraoral sites occasioned by eating, toothbrushing, etc.

‘Premalignant’ Lesions/Conditions of Epithelial Tissue Origin

Several lines of evidence, including clinical, experimental, and morphological data, support the concept that squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract arises from noninvasive lesions of the squamous mucosa. These lesions encompass a histological continuum between the normal mucosa at one end and high grade dysplasia/carcinoma in situ, at the other, establishing a model of neoplastic progression. This continuum of preinvasive neoplasia is encountered in many other epithelia, including the lower respiratory tract and the cervix uteri.

The identification of preneoplastic lesions of the upper aerodigestive tract, through clinical, morphological and more recently, molecular means, helps in the early detection and treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Moreover, understanding and documenting the morphological and molecular abnormalities associated with this progression may shed light on the biology of these tumors.

Historically, the definition of an oral premalignant lesion dates back to 1978, when it was defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “a morphologically altered tissue in which cancer is more likely to occur than in its apparently normal counterpart.” The precancerous condition in its turn is “a generalized state associated with a significantly increased risk of cancer”. Examples of precancerous conditions are siderope-nic dysphagia, submucous fibrosis and possibly, lichen planus.

Cancer being a genetic disorder involves multiple alterations of the genome progressively accumulated during a protracted period, the overall effects of which surpass the inherent reparative ability of the cell. In the course of its progression, visible physical changes are taking place at the cellular level (atypia) and at the resultant tissue level (dysplasia). These alterations include genetic changes, epigenetic changes, surface alterations and alterations in intercellular interactions. The sum total of these physical and morphological alterations are of diagnostic and prognostic relevance and are designated as ‘precancerous’ changes. In many situations, the relationship between these changes and the progression towards neoplasia is not understood. Nevertheless, it seems probable that these changes are ultimately involved in driving cells further along the path to neoplastic transformation.

The diagnosis of precancers is primarily based on morphology and its grading on histology (dysplasia). Despite the fact that this estimation is subjective and therefore carries a low prognostic value of an impending malignancy, it is still widely practiced to assess the risk of malignant potential of such lesions. Because of this inherent discrepancy such lesions may well be designated as potentially malignant.

A premalignant phase in the development of oral cancer is predicted by the classic model of experimental epithelial carcinogenesis. Virtually all oral squamous cell carcinomas arise from a premalignant precursor, but it is difficult to specifically define the term ‘premalignant’. Oral pathologists use the term epithelial dysplasia to indicate microscopic features in a biopsy specimen that are associated with a risk of malignant change and then assign a grade of severity. There is good correlation between higher grades of dysplasia and increasing risk of cancer but less so with the lower grades.

Dysplasia

The histologic connotation to premalignancy is marked by aberrant and uncoordinated cellular proliferation depicted basically at cellular level (atypia), reflections of which could be discerned at tissue levels too (dysplasia). Frequently it is the forerunner of cancer, the causation of this twilight zone in cellular transformation is by no means clear. Dysplasia is encountered principally in the epithelia. “It comprises a loss in the uniformity of the individual cells, as well as a loss in their architectural orientation.” Dysplastic cells exhibit considerable pleomorphism (variation in size and shape) and often possess deeply stained (hyperchromatic) nuclei, which are abnormally large for the size of the cell. The nuclear: cytoplasmic ratio increases from 1:4 to 1:1, at the expense of the cytoplasmic volume. Mitotic figures are more abundant than usual, although almost invariably they conform to normal pattern. Frequently, the mitoses appear in abnormal locations within the epithelium and may appear at all levels rather than in its usual basal location. The usual proliferative organization of the epithelium (see below) is lost and is replaced by a disorderly arranged scramble of cells with varying degrees of differentiation arrest.

“Dysplasia is characteristically associated with protracted chronic irritation or inflammation”, of which oral cavity is a common site. Due to its peculiar anatomic location and its constant presence of endogenous and exogenous micro-organisms, a sustained state of chronic subclinical infection is maintained at the oral cavity. Overlying physical trauma consistently inflicted on the oral mucosa, compounds the existing situation.

“Dysplasia is a reversible, and therefore presumably a controlled, cellular alteration. When the underlying inciting stimulus is removed, the dysplastic alterations revert to normal.” However, there is an important and significant cellular change discerned at the morphological level which cautions its likelihood of subsequent neoplastic transformation. The line of demarcation when the cell surpasses the point of no return is rather faint and the underlying mechanism poorly defined. In short, dysplasia giving rise to neoplasia is akin to cellular changes in response to a noxious stimulus. As it is evident it traverses the stage of cellular adaptation, reversible damage, and finally, irreversible cell death. When a susceptive cell is exposed to a carcinogen it probably tries to adapt to it, depending on the extent and duration of stimuli. An increase in cell proliferation, diminishing the cytosolic volume and the associated organellar load, could be an attempt in this direction. In the context of oral epithelium, an accelerated growth phase depicted by broadening the progenitor compartment (hyperplasia) is the earlier sequela of exposure to an irritant. When the irritant persists, the epithelium shows features of cellular atrophy, again a well characterized feature of adaptation (atrophy). At a later stage when the stages of adaptation and reversible cell damage surpass, the cells progressively slip into a stage of irreversible cell damage; manifests either as cell death or neoplastic transformation. It appears that some mysterious line is crossed, whereby dysplastic cells escape the normal homeostatic controls and assume the autonomy of a tumor cell. The accelerated pace of cell division noted at the earlier stages of transformation as part of an adaptive response (to replace the damaged cell pool) is, in a way, facilitative of the accumulation of further genetic damage, thereby driving the cells further along the path of transformation. As it is apparent from the foregoing discussion, there is considerable overlap between the stages of cellular adaptation, reversible damage and atypia. Precise morphologic and genetic criteria delineating this line of demarcation between atypia (reversible damage) and neoplasia is unfortunately unknown and is the scope of the study of tumor biology.

Proliferative Organization of Oral Epithelium

Advances in our understanding of the proliferative organization of the oral epithelium has been a slow process for several reasons. These include a lack of suitable experimental models to test hypotheses, difficulty in extrapolating from other renewing cell systems and the need for new investigative techniques (Hume, 1991). The earlier rather mechanistic concept envisages a uniform progenitor compartment occupying the basal layer, retained in a state of sustained replication readiness with roughly equal cell cycle times and their migration towards the surface layers is simply by physical process of forward push induced during waves of cell division. Experimental work to elucidate these underpinned concepts and radical revisions are made (Leblond et al, 1964).

Between 1969 and 1975, a number of workers showed that these concepts were too simple, which suggested that a complex pattern of migration from the basal layer to the surface had to occur to maintain this highly ordered and non-random cell stacking. This, in turn, focused attention on the pattern of cell proliferation in the basal layer and led to the concept of the existence of a number of proliferative subpopulations, of which the stem cell population seemed to be of particular importance for tissue homeostasis and disease. This concept envisages that not all cells in the basal layer can divide, that a number are instead already differentiating, that cells capable of division comprise a number of subpopulations and finally, that cell migration is not caused by cell proliferation pressure but is an independent biological process.

The use of oral epithelium as a model for the investigation of the behavior of proliferative subpopulations followed on from the work that had already begun in rodent skin, it is also true that because of its particular morphological structure and marked circadian (diurnal) variation in cell proliferation, it has contributed significantly to the development of an integrated cell proliferation model applicable also to bone marrow, intestine, testis, nematodes and also to developmental situations (Hume, 1991).

Staging of Oral Precancerous Lesions

The value of histology as an indicator of cancer risk is time-tested not only in the oral cavity or other head and neck regions, but also in other sites, including the uterine cervix, lung, breast, skin, and esophagus. More likely, the future will see gradual extension of the classical histological and clinical approaches to include an evaluation of molecular markers.

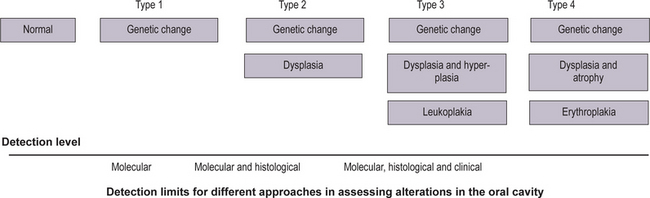

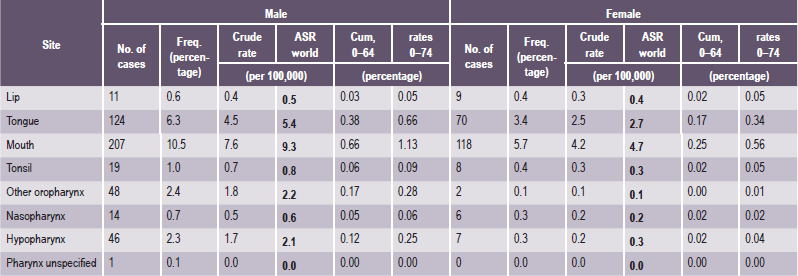

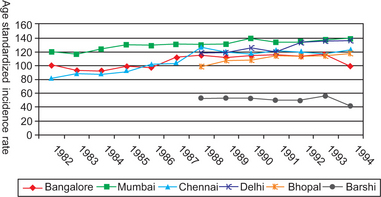

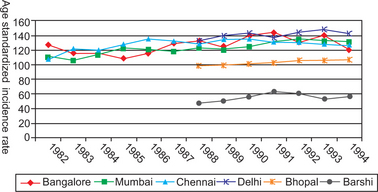

An increase in abnormality in either histology or genetic markers was associated with an increase in cancer risk (Fig. 2-6). More recently, studies reported an association of ploidy status (DNA content) in dysplastic lesions with progression risk of oral precancers. The lowest risk was associated with diploid dysplastic lesions (3% progressed into oral squamous cell carcinoma), tetraploid lesions had an intermediate risk (60% showed progression), and aneuploid dysplasia showed the greatest risk (84% progressed). (Lippmann SM, Hong WK, 2001). With time, more such studies will accrue. A future goal will be to determine which combinations of histological and molecular markers best predict risk.

How can such information best be handled? One possibility is to develop staging systems that incorporate different risk factors into risk models. One such model is presented in Table 2-1. For the sake of simplicity, this hypothetical model only includes pathological and molecular markers (clinical features such as appearance, site, and size of the lesion, are not included but should be part of an eventual screening system). In this model, the majority of lesions would be placed into stage 1, with the lowest probability of progressing to cancer. Such lesions would contain both low-risk pathology (P1) and genetic patterns (G1). The emergence of intermediate-risk patterns in either histology (P2) or genetic profile (G2) would place a lesion into stage 2. Stage 3 would contain lesions with a high-risk genetic or histology pattern. It should be noted that the greatest impact of such a staging system would be on lesions in stage 3. Such lesions would now include cases with a relatively benign phenotype (without or with minimal dysplasia) but a high-risk genotype (e.g. P1 G3).

Table 2-1

Staging of oral premalignant lesions with both pathologic and genetic indicesa

| Stage (cancer risk) | Pathology (P)b and genetic (G)c patterns |

| 1 | P1 G1 |

| 2 | P1 G2 |

| P2 G1 | |

| P2 G2 | |

| 3 | P3 G1 |

| P3 G2 | |

| P1 G3 | |

| P2 G3 | |

| P3 G3 |

aAdapted from Zhang and Rosin (2001).

bPathological indices: P1, no dysplasia or mild dysplasia; P2, moderate dysplasia and P3, severe dysplasia/CIS.

cGenetic patterns, categorized by increasing risk: G1, low risk; G2, intermediate risk, and G3, high risk.

Leukoplakia (Leukokeratosis)

Leukoplakia (white patch) is the most common potentially malignant lesion of the oral mucosa. However, its usage should be limited exclusively to the clinical context by the exclusion of other lesions, which present as oral white plaques. Such lesions are lichen planus (hypertrophic), chronic cheek-bite (morsicatio), frictional keratosis, tobacco-induced keratosis (nicotine stomatitis), leukoedema and white sponge nevus. When a biopsy is taken, the term leukoplakia should be replaced by the diagnosis obtained histologically. In other words, leukoplakia denotes a negative diagnosis based on exclusion criteria. It represents an area localized in distribution, hyperkeratotic in nature and white in appearance due to wetting of the keratotic patch while in contact with saliva. It should be stressed that the diagnosis of leukoplakia denotes mainly, that

• The mucosa is irritated by either mechanical, chemical or galvanic means, and

• The mucosa is trying to adapt to the noxious stimuli by undergoing hyperkeratinization of its surface (good example of tissue adaptation—see earlier paragraphs).

Since leukoplakia is an adaptive response, offered by a viable and healthy oral mucosa against some forms of sustained, low-grade irritant, it is irrational to consider it as a disease entity (hence its assumption of a negative diagnostic state).

Deinition and Terminology

Oral leukoplakia has recently been redefined as “a predominantly white lesion of the oral mucosa that cannot be characterized as any other definable lesion; some oral leukoplakia will transform into cancer” (Axell T, 1996). A provisional diagnosis is made when a lesion at clinical examination cannot be clearly diagnosed as any other disease of the oral mucosa with a white appearance. A definitive diagnosis is made when it is histopathologically examined. The term preleukoplakia is sometimes used when the whiteness is not very distinct and should not be confused with leukoedema (a hereditary malformation of the oral mucosa).

Definable White Lesions

• Hyperplastic candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia). When dealing with a hyperplastic epithelial lesion in which the presence of Candida albicans is demonstrated, it is referred to as candida-associated leukoplakia or others prefer the term hyperplastic candidiasis. In the absence of clinical re-sponse to antifungal treatment, it seems preferable to con-sider such lesion as leukoplakia (van der Waal, 1997).

• Hairy leukoplakia (Greenspan lesion). The term ‘hairy leukoplakia’ is a misnomer due to several reasons. First of all, hairy leukoplakia is a definable lesion. Furthermore, the lesion is not premalignant in nature. Therefore, the use of the term should be abandoned. As an alternative, the term ‘Greenspan lesion’ has been suggested.

• Tobacco-induced white lesions. Smoker’s palate (leukokera-tosis nicotina palati), palatal keratosis in reverse smokers and snuff dippers lesions are clearly related to tobacco use and, therefore, are usually listed as ‘tobaccoinduced le-sions’. These lesions are being regarded as ‘definable le-sions’ and are traditionally not described as leukoplakia. Nevertheless, some of these lesions may transform into cancer.

• Tobacco-associated leukoplakia. The etiological role of to-bacco in patients who smoke cigarettes, cigars or pipes is less obvious. Therefore, preference has been given to the term ‘tobacco-associated leukoplakia’ (leukoplakia in smokers) over the term ‘tobacco-induced white lesions’.

• Idiopathic leukoplakia. One also recognizes nontobacco-associated leukoplakia (leukoplakia in nonsmokers), often referred to as idiopathic leukoplakia.

Premalignant/Potentially Malignant Lesion

In two studies from India (Gupta PC et al, 1980, Silverman S et al, 1976), rather low annual malignant transformation rates of oral leukoplakia have been reported, 0.3% and 0.06%, respectively. In reports from western countries, usually based on hospital material, somewhat higher figures have been mentioned (Axell T, 1987). One must take the following into account, when studying percentages of malignant transformation rates of oral leukoplakia:

On the basis of the lowest reported annual malignant transformation rate of oral leukoplakia, it can be calculated that patients with oral leukoplakia carry a five fold higher risk of developing oral cancer than controls. Recently the role(s) of dietary factors in determining the precancerous nature of oral leukoplakia among tobacco habitues revealed interesting results (Gupta PC et al, 1998). A population-based case control study in the Bhavnagar district, Gujarat, India estimated nutrient intake in blinded, house-to-house interviews. Among 5,018 male tobacco users, 318 were diagnosed as cases. An equal number of controls matched on age (± 5 years), gender, village, and use of tobacco were selected. Odd ratio (OR), a measure of the relative risk of malignant transformation of individual lesions were calculated from multiple logistic regression analysis controlling for relevant variables (type of tobacco use and economic status), a protective effect of fiber was observed for both oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) and leukoplakia; with 10% reduction in risk per gm day (p<0.05). Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) appeared to be protective against leukoplakia with the halving of associated risk of malignant transformation (OR 0.46; p<0.10). It is apparent that in addition to tobacco use, intake of specific nutrients and their deficiency may have a role in the development and progression of oral precancerous lesions.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of this lesion in Ernakulam district (Kerala, India) was 17 per 1,000; it was highest (61 per 1,000) among people with mixed habits. The annual age adjusted incidence rate was 2.1 per 1,000 among men and 1.3 per 1,000 among women; the highest incidence (6.0 per 1,000) was among men who both chewed and smoked. In an adult Swedish population a 3.6% prevalence rate was recorded (Axell T, 1976). Almost all leukoplakia in India occur in tobacco users. A definite dose-response relationship between leukoplakia and various forms of tobacco use in this area has been demonstrated. The dose-response relationship was stronger for the smoking habit than for the chewing habit and remained significant after taking account of age, gender and type of tobacco habit.

Age and Gender

The onset of leukoplakia usually takes place after the age of 30 years; resulting in a peak incidence above the age of 50 years. The gender distribution in most studies varies, ranging from a strong male predominance in different parts in India, to almost 1 : 1 in the western world.

Etiology

Leukoplakia occurs more frequently in smokers of tobacco than in nonsmokers. There is a dose-response relationship between tobacco usage and the prevalence of oral leukoplakia. Reducing or cessation of tobacco use may result in the regression or disappearance of oral leukoplakia (Gupta et al, 1995). On the other hand, disappearance of oral leukoplakia has occasionally been reported in patients who continued to smoke (Silverman and Rozen, 1968). Tobacco was most often chewed as an ingredient in betel quid (smokeless tobacco or paan) in India. The paan-chewers’ lesion consists of a thick, brownish-black encrustation on the buccal mucosa at the site of the placement of betel quid. It is often seen in heavily addicted betel quid chewers. It could be scraped off with a piece of gauze (leukoplakia); it regresses spontaneously when the habit is discontinued. Due to these reasons the paan-chewer’s lesion does not deserve the designation of leukoplakia. This is a specific entity and rarely progresses to leukoplakia. Whether the use of alcohol by itself is an independent etiological factor in the development of oral leukoplakia, is still questionable. Its effect, at best, may be synergistic to other well-known etiological factors (physical irritants). The role of Candida albicans as a possible etiological factor in leukoplakia and its possible role in malignant transformation is still unclear. About 10% of oral leukoplakias satisfy the clinical and histological criteria for chronic hyperplastic candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia). Epithelial dysplasia is reported to occur four to five times more frequently in Candida leukoplakia than in leukoplakia in general. However, this change is more common in the speckled variant than in homogeneous leukoplakia and carcinomatous change is more a characteristic of the speckled lesion than that of candidal superinfection. Various kinds of evidence has been presented to justify an etiologic role for candida in neoplastic transformation, which includes, among others, the catalytic transformation in vitro of the carcinogenic nitrosamine, N-nitrosobenzyl-methylamine, by strains of C. albicans demonstrated to be selectively associated with leukoplakia. The possible contributory role of viral agents (human papilloma virus strains 16, 18) in the pathogenesis of oral leukoplakia has also been discussed, particularly with regard to exophytic verrucous leukoplakia (Palefsky JM et al, 1995). In a study from India, serum levels of vitamin A, B12, C, beta-carotene and folic acid were significantly decreased in patients with oral leukoplakia compared to controls, whereas, serum vitamin E was not (Ramaswamy G et al, 1996). Relatively little is yet known with regard to possible genetic factors in the development of oral leukoplakia.

Clinical Aspects

Preleukoplakia is defined as a low-grade or very mild reaction of the oral mucosa, appearing as a gray or grayish-white, but never completely white area with a slightly lobular pattern and with indistinct borders blending into the adjacent normal mucosa (Pindborg et al, 1968).

Clinical Classification

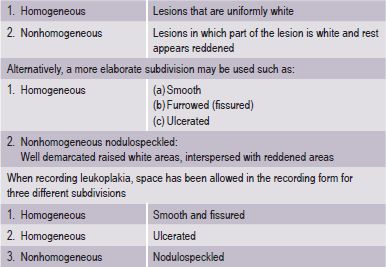

It is desirable to record, separately the various forms of leukoplakia and for this purpose subdivisions are recommended (WHO, 1980) (Table 2-2).

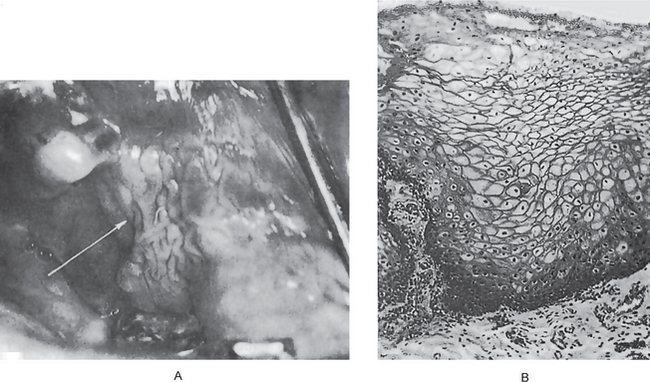

The adjective ‘nonhomogeneous’ is applicable both to the aspect of color, i.e. mixture of white and red changes (erythroleukoplakia) and to the aspect of texture, i.e. exophytic, papillary or verrucous. With regard to the latter lesions, no reproducible clinical criteria can be provided to distinguish (proliferative) verrucous leukoplakia from the clinical aspect of verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. The homogeneous type is usually otherwise asymptomatic, whereas the nonhomogeneous (mixed white and red) leukoplakia are often associated with mild complaints of localized pain or discomfort. In the presence of redness or palpable induration, malignancy may already be present (Fig. 2-7).

Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia and its Related Lesions

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) and verrucous hyperplasia (VH) are two related oral mucosal lesions. The terms; however, are not clinically or pathologically interchangeable. The term PVL is preferably a clinical one, but the diagnosis of VH, on the other hand, must be made histologically.

PVL

First described by Hansen et al, in 1985, PVL continues to be recognized as a particularly aggressive form of oral idiopathic leukoplakia that has a considerable morbidity and a strong potential for malignant transformation. Diagnosis is often made late in the protracted course of PVL with the disease in an advanced stage when it is especially refractory to treatment. The histologic spectrum that is seen in PVL are:

VH

This is a forerunner of verrucous carcinoma and the transition is so consistent that the hyperplasia, once diagnosed, should be treated like verrucous carcinoma.

Histopathological Aspects

It should be emphasized that leukoplakia is a clinical term, and its use carries no implications with regard to the histological findings. However, it is recommended that a histological report should always include a statement on the presence or absence of epithelial dysplasia, and if present, the assessment of its severity. The hallmarks of the histopathological aspects of leukoplakia are epithelial hyperplasia and surface hyperkeratosis. Epithelial dysplasia, if present, may range from mild to severe. In some instances, carcinoma in situ and even squamous cell carcinoma are encountered histologically. The various cellular changes that may occur in epithelial dysplasia are listed in Table 2-3. The clinical significance of human papilloma virus-associated epithelial dysplasia, so-called ‘koilocytic dysplasia’ remains to be investigated. The term ‘lichenoid dysplasia’ is sometimes used when the dysplastic epithelium may show features that, to some extent, resemble those of lichen planus. The term ‘chevron’ type of keratinization is used when it is associated with use of tobacco. Microabscesses may be observed in the superficial layers of the epithelium in the presence of C. albicans and inflammatory cell infiltration is commonly seen. Some of the exophytic, verrucous or papillomatous lesions, in spite of the absence of epithelial dysplasia, may in time progress to squamous cell carcinoma and that long-term follow-up should be considered. The final diagnosis of a white lesion of the oral mucosa can often only be made through a close dialogue between the clinician and the pathologist. Even then, cases may remain unsettled.

Table 2-3

Histopathological features of epithelial dysplasia

1. Loss of polarity of the basal cells

2. Presence of more than one layer of cells having a basaloid appearance

3. Increased nuclear cytoplasmic ratio

4. Drop-shaped rete processes

5. Irregular epithelial stratification

6. Increased number of mitotic figures (a few abnormal mitoses may be present)

7. Presence of mitotic figures in the superficial half of the epithelium

8. Cellular pleomorphism

9. Nuclear hyperchromatism

10. Enlarged nucleoli

11. Reduction of cellular cohesion

12. Keratinization of single cells or cell groups in the prickle layer

Grading of Epithelial Dysplasia

Epithelial dysplasia is usually assessed subjectively and considerable interobserver variability exists in its interpretation. Principally, what is lacking in this exercise is objectivity and lack of reproducibility. A consensus decision is, by and large, adopted in the management of individual lesions and based on the presence of dysplastic features, epithelial dyplasia is usually divided into three categories: mild, moderate and severe. It is recommended that the histological report of a leukoplakia should include a statement on the absence or presence of epithelial dysplasia and an assessment of its severity. The practical value of the grading of epithelial dysplasia is questionable. Although leukoplakia with moderate or severe epithelial dysplasia shows a greater disposition for malignant transformation than in the absence of dysplastic features, carcinomatous transformation may also take place in non-dysplastic leukoplakias.

Modified Classification and Staging System for Oral Leukoplakia

A proposal for a modified classification and staging system for oral leukoplakia (OLEP) has been presented by Van der Waal et al, 2000 in which the size of the leukoplakia and the presence or absence of epithelial dysplasia are taken into account. Altogether four stages are recognized:

L1 — Size of leukoplakia <2 cm

L2 — Size of leukoplakia 2–4 cm

L3 — Size of leukoplakia >4 cm

P1 — Distinct epithelial dysplasia

Px — Dysplasia not specified in the pathology report.

OLEP Staging System

The proposed system should facilitate uniform reporting of treatment or management results of OLEPs in which a biopsy has become available. The system can easily be adjusted by replacing the histopathological criteria of epithelial dysplasia by a clinical subdivision in homogeneous and nonhomogeneous leukoplakia for cases in which no biopsy is available. It also could serve as a means for epidemiological studies. It has yet to be shown whether such a staging system may also be helpful in providing guidelines for the management of oral leukoplakias.

Diagnostic Procedures

Elimination of Possible Cause(s)

The clinician should first try to rule out any of the definable white lesions before accepting a definitive clinical diagnosis of leukoplakia.

Biopsy

In homogeneous leukoplakia, the value of histological examination might, to some extent, be questioned. The occurrence of epithelial dysplasia is rather low in this clinical subtype, as is the risk of future malignant transformation. However, this cannot be taken as the dictum in all cases since at least in few cases it proves to be otherwise. Therefore, the taking of a biopsy in homogeneous leukoplakia should be the standard rule. If treatment consists of CO2-laser evaporation, it is mandatory to have a biopsy taken prior to such treatment. In nonhomogeneous leukoplakia, biopsy should be taken at the site of symptoms, if present, and/or at a site of redness or induration. Diagnostic methods other than histological examination, such as the use of toluidine blue staining or Lugol’s iodine and exfoliative cytology are of limited value when dealing with leukoplakia.

Treatment Modalities

Apart from the surgical excision, various treatment modalities are available, such as cryosurgery, CO2-laser surgery, retinoids and other drugs, and recently, photodynamic therapy. The last is a rather recent application with regard to oral leukoplakia, therefore does not deserve comment on long-term results.

Possible Solutions

This overview demonstrates that to-bacco smoking and betel quid chewing are detrimental to oral health, as they are strongly associated with oral leukoplakia, oral cancer and other mucosal pathologies. In view of these findings, specific studies for primary and secondary preven-tion of these lesions are warranted. Prevention was found to be feasible and effective (Gupta et al, 1980) by timely diag-nosis and management of oral precancerous lesions like leu-koplakia and by measures like habit alleviation. Effort in this direction will take us a long way into the overall control and management of potentially malignant oral mucosal lesions.

Leukoedema

Leukoedema is an abnormality of the buccal mucosa which clinically resembles early leukoplakia, but appears to differ from it in certain respects.

Clinical Features

The gross appearance of leukoedema varies from a filmy opalescence of the mucosa in the early stages to a more definite grayish-white cast with a coarsely wrinkled surface in the later stages (Fig. 2-8 A). Lesions occur bilaterally in the majority of cases and frequently involve most of the buccal mucosa, extending onto the oral surface of the lips. Leukoedema is most noticeable along the occlusal line in the bicuspid and molar region. In some cases, desquamation occurs, leaving the surface eroded.

Etiology

The etiology of leukoedema is unknown. An extensive study of this condition was carried out in the United States by Sandstead and Lowe, who found no apparent correlation between the incidence of the condition and the use of tobacco, the pH of the saliva, oral bacterial infection, syphilis or galvanic irritation. In their study, the incidence of leukoedema was approximately 45% in Caucasian men and 40% in Caucasian women, while it was 94% in Negro men and 86% in Negro women, all adults with an average age of 45 years.

It has now been identified in many countries around the world with a remarkable variation in prevalence that suggests some ethnic association. The different reported epidemiological studies have been reviewed by Axell and Henricsson, who also noted an incidence of occurrence of nearly 50% in a survey of over 20,000 persons aged 15 years and above in Sweden. Their data suggested that tobacco smoking was closely correlated with the occurrence of the leukoedema, although studies from India, where tobacco use is extremely prevalent, have shown a very low incidence of leukoedema.

Histologic Features

The microscopic features of leukoede-ma consist of an increase in thickness of the epithelium, intra-cellular edema of the spinous or malphigian layer, a superfi-cial parakeratotic layer of several cells in thickness, and broad rete pegs which appear irregularly elongated (Fig. 2-8 B). The characteristic edematous cells appear extremely large and pale, and they present a reticular pattern. The cytoplasm appears lost, and the nuclei appear absent, clear or pyknotic. Infla-mmatory cell infiltration of the subjacent connective tissue is not a common finding.

In a review and discussion of leukoedema, Archard and his coworkers have concluded that the clinical appearance of the lesion is due to a retained superficial layer of parakeratotic cells.

Clinical Significance

It has been suggested that leuko-edema may represent a lesion of the oral mucosa in which leukoplakia is more apt to develop than in normal epithelium. This conclusion is based upon the fact that nearly all patients examined who manifested leukoplakia also exhibited leuko-edema in the adjacent mucosa. However, Archard and his coworkers have concluded, on the basis of their studies, that there is no evidence to support this contention. Furthermore, they concluded that there is no evidence that this lesion is pre-malignant or in any way associated with potential malignant alteration.

Since leukoedema appears to be simply a variant of normal mucosa, no treatment is necessary.

Intraepithelial Carcinoma (Carcinoma in situ)

Intraepithelial carcinoma is a condition which arises frequently on the skin, but occurs also on mucous membranes including those of the oral cavity. Some authorities believe that this disease represents a precancerous dyskeratotic process, but others say that it is a laterally spreading, intraepithelial type of superficial epithelioma or carcinoma. As Chandler Smith has expressed in a discussion on the concept of the term carcinoma in situ, it “does not reveal whether the lesion is a cancer now but has not yet become invasive, or whether it is not a cancer now but will become a cancer at some later time”. Nevertheless, in this stage, it does not exhibit invasive malignant properties. Since metastasis cannot occur without infiltration of tumor cells into connective tissue and consequent accessibility to lymphatic or blood vessels, metastasis is impossible in intraepithelial carcinoma.

Bowen’s disease is a special form of intraepithelial carcinoma occurring with some frequency on the skin, particularly in patients who have had arsenic therapy, and is often associated with the development of internal or extracutaneous cancer. On rare occasions, as reported by Gorlin, Bowen’s disease may occur in the oral cavity.

Clinical Features

In a study of 82 lesions of carcinoma in situ in 77 patients reported by Shafer, he found that the clinical appearance was that of a leukoplakia in 45% of the lesions, an erythroplakia in 16% of the lesions, a combination of leukoplakia and erythroplakia in 9%, an ulcerated lesion in 13%, a white and ulcerated lesion in 5%, a red and ulcerated lesion in 1% and not stated in 11%.

These lesions have been reported to occur at all intraoral sites but the most common in the study of Shafer were floor of mouth (23%), tongue (22%) and lips in males (20%). This distribution is roughly comparable to that found in a series of 158 lesions of asymptomatic early oral epidermoid carcinoma reported by Mashberg and his associates. They appear to be somewhat more common in men than in women (1.8 : 1) and tend to occur principally in elderly persons.

Histologic Features

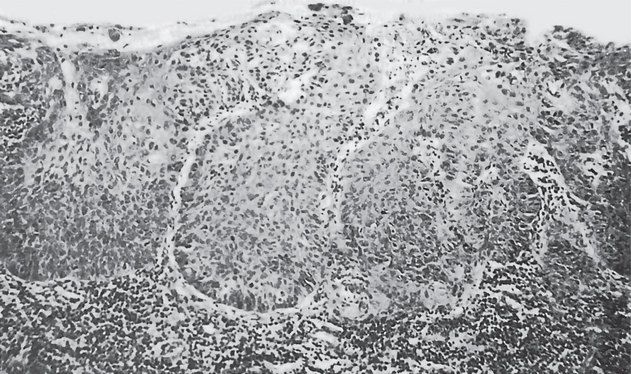

Intraepithelial carcinoma is character-ized by a remarkable range of variation in histologic appear-ance. Keratin may or may not be found on the surface of the lesion but, if present, is more apt to be parakeratin rather than orthokeratin. Individual cell keratinization and epithelial or keratin pearl formation are exceedingly rare. In fact, these ap-pear to be a hallmark of transformation of carcinoma in situ into invasive carcinoma, so that if these are found, a further search should be made for carcinomatous invasion. In some instances, there appears to be hyperplasia of the altered epithe-lium, while in others there is atrophy.

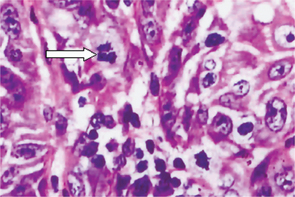

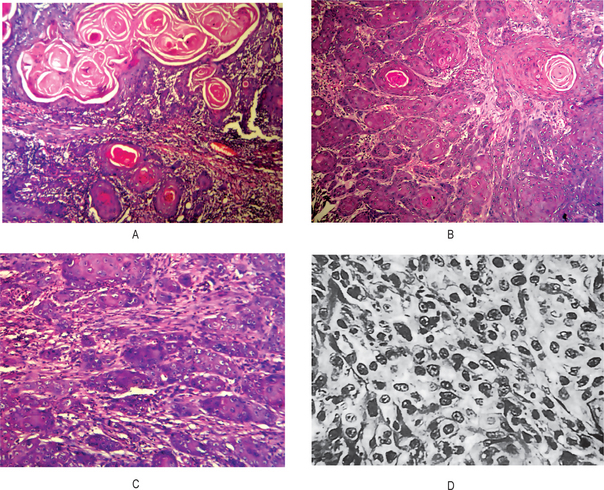

Certain cytologic alterations may also occur. An increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and nuclear hyperchromatism are sometimes seen, but many cases do not show these. Cellular pleomorphism is quite uncommon. One of the most conspicuous and consistent alterations is loss of orientation of cells and loss of their normal polarity. Mitotic activity is extremely variable and of little significance unless overwhelming (Fig. 2-9).

Figure 2-9 Intraepithelial carcinoma or carcinoma in situ. The epithelial cells exhibit all the features of malignant cells, but invasion of the connective tissue has not begun.

It has also been found that sometimes a sharp line of division between normal and altered epithelium extends from the surface down to the connective tissue rather than a blending of epithelial changes. It is also not unusual to find multiple areas of carcinoma in situ interspersed by essentially normal appearing epithelium, producing multifocal carcinoma in situ.

All of the above changes occur within the surface epithelium, which remains confined by the basement membrane.

Treatment and Prognosis

There is no uniformly accepted treatment for intraepithelial carcinoma. The lesions have been surgically excised, irradiated, cauterized and even exposed to solid carbon dioxide. If the condition is left untreated, carcinomatous invasion is thought to occur eventually. Spontaneous regression of carcinoma in situ without treatment is known to occur in certain sites, chiefly the uterine cervix, in a significant percentage of cases. However, it is doubtful that this happens in the oral cavity; although progression into invasive carcinoma may take years in some instances, in others it apparently develops within months.

Erythroplakia (Erythroplasia of Queyrat)

Whilst leukoplakia is a relatively common condition, erythro-plakia is rare. In contrast to leukoplakia, erythroplakia is almost always associated with premalignant changes histologically and is, therefore, the most important precancerous lesion. The term ‘erythroplakia’ is used analogously to leukoplakia to designate lesions of the oral mucosa that present as bright red velvety plaques which cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as due to any other condition. Just as there are many oral lesions that present clinically as white patches on the mucosa, so there are a number of conditions that appear as red areas. These include some dermatoses, inflammatory conditions due to local infection, or a more general subacute or chronic stomatitis associated with the presence of dentures, tuberculosis, fungus infection and other conditions. Some red plaques prove to be early squamous cell carcinomas. The red patches that cannot be classified in any of these classes fall into the group of erythroplakia (a negative diagnosis— refer leukoplakia). The term ‘erythroplasia’ was originally used by Queyrat to describe a precancerous red lesion that develops on the penis. Oral erythroplakia is clinically and histopathologi-cally similar to the genital process. Whereas red lesions of the oral mucosa have been noted for many years, the use of the term erythroplakia in this context was rare. Erythroplakia lesions are easily overlooked and the true prevalence of the condition is not known. This blatant underreporting probably reflects the fact that leukoplakias are more likely to be biopsied and emphasizes the lack of appreciation of the significance of erythroplakia clinically. Several clinical variants of erythroplakia have been described by different investigators, but there is no general agreement on classification. Shear, in 1972, described “homogeneous erythroplakia, erythroplakia interspersed with patches of leukoplakia, and granular or speckled erythropla-kia” (the last category identical to speckled leukoplakia). The suggestion has also been made to change the term speckled leukoplakia to speckled erythroplakia, to emphasize the frequency with which this particular lesion is associated with cellular atypia. Many of these lesions are irregular in outline, and some contain islands of normal mucosa within areas of erythroplakia, a phenomenon that has been attributed to co-alescence of a number of precancerous foci. The high rate of premalignant and malignant changes noticed in erythroplakia is true for all clinical varieties of this lesion and not solely a feature of speckled erythroplakia. Different studies have dem-onstrated that 80–90% of erythroplakias are histopathologically either severe epithelial dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or invasive carcinoma. Erythroplakia has no apparent sex predilection; most cases reported have occurred in the sixth and seventh decades. The etiology of erythoplakia is unknown, although it seems likely that smoking and alcohol abuse are important etiological factors.

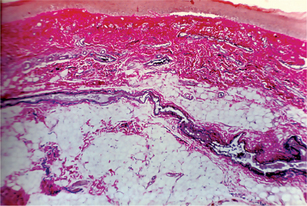

Histopathologic Features

The epithelium shows lack of keratin production and is often atrophic, but it may be hyperplastic. This lack of keratinization, especially when combined with epithelial thinness, allows the underlying microvasculature to show through, thereby causing the red color. The underlying connective tissue often demonstrates chronic inflammation. Differentiation of erythroplakia with malignant change and other early squamous cell carcinomas from benign inflammatory lesions of the oral mucosa can be enhanced by use of 1% toluidine blue (tolonium chloride) solution applied topically with a swab or as an oral rinse. This technique gives excellent results in detecting epithelial dysplasia with false-negative (underdiagnosis) and false positive (overdiagnosis) rates of well below 10%.

Treatment

It should follow the same principles outlined for leukoplakia. Observation for one to two weeks following elimination of suspected irritants is acceptable. Prompt biopsy is thereafter mandatory for lesions that persist. Surgical excision gives excellent results and a recurrence rate of less than 5% is reported.

Leukokeratosis Nicotina Palati

This lesion commonly seen among conventional smokers, consists of a grayish-white palate with small nodular excrescences having small central red spots corresponding to the inflamed orifices of the minor salivary glands (Murti et al, 1992).

Epidemiology

The prevalence of this lesion among Indians was 0.3%; 52% of the 31 lesions occurred among bidi smokers (Mehta FS et al, 1971). The annual age adjusted incidence rate among smokers was 1.7 per 1,000; 0.7 per 1,000 in those who smoked and chewed (Gupta PC et al, 1980).

Natural History

Over a longer period 66% of the 44 lesions remained stationary, 34% regressed spontaneously and none showed malignant transformation. Palatal changes in reverse smokers (smoke with the burning end of a cigar/ cigarette within the oral cavity), on the other hand, must be distinguished from this lesion and are multimorphic and precancerous, whereas leukokeratosis nicotina palati exhibits neither great variability nor malignant transformation (Table 2-4).

Table 2-4

Classiication of oral mucosal lesions

Based on different habits the lesions can be grouped broadly as shown:

Predominantly associated with smoking

Leukoedema

Leukokeratosis nicotina palati

Palatal erythema

Central papillary atrophy of tongue

Predominantly associated with chewing

Paan chewer’s lesion

Oral lichen planus-like lesion

Oral submucous fibrosis

Associated with smoking and chewing (mixed habit)

Leukoplakia and preleukoplakia

Oral lichen planus

Oral squamous carcinoma

Palatal Changes Associated with Reverse Smoking

Reverse chutta (crude form of cigar) smoking practiced especially among females of Srikakulam district of Andhra Pradesh, recorded a prevalence of 8.8% of leukoplakia, 4.6% preleukoplakia and 17.9% leukokeratosis nicotina palati (Daftary et al, 1992). Palatal involvement was noted in 422 (85%) of the 497 leukoplakia cases and in 168 (57%) of the 296 preleukoplakias, and of course in all of the cases of leukokeratosis nicotina palati. Palatal changes associated with reverse smoking thus exhibited a spectrum of clinical changes, and it was not satisfactory to group them under leukoplakia, preleukoplakia or leukokeratosis nicotina palati. Accordingly, a new classification for palatal changes encompassing the entire spectrum of clinical components was proposed by Mehta FS et al, 1977.

Epidemiology

The annual age-adjusted incidence rates of palatal changes (encompassing all components) was 24.9 per 1,000 among men and 39.6 per 1,000 among women and the peak incidence was in the 55–64 year age group (Srikakulam data).

Clinical Aspect

Palatal changes comprise several compo-nents:

• Keratosis—diffuse whitening of the entire palatal mucosa

• Excrescences—1–3 mm elevated nodules, often with central red spots

• Patches—well defined, elevated white plaques

• Red areas—well defined reddening of the palatal mucosa

• Ulcerated areas—crater-like areas covered by fibrin

• Nonpigmented areas—areas of palatal mucosa that are de-void of pigmentation.

Histological Features

Hyperorthokeratosis, epithelial dys-plasia and inflammatory cells in the connective tissue were observed in 87%, 23% and 55% of the biopsies collected from Srikakulam district (Daftary et al, 1992). Melanin depos-its were noted in the lamina propria of most of them. The epithelium was atrophic in 60% of biopsies from red areas. Epithelial dysplasia was observed in 52% of red areas, 25% of excrescences, 20% of ulcerations, 10% of patches and in 19% of nonpigmented areas.

Natural History

In a six-year follow-up study, palatal changes remained stationary in 75% of individuals; regressed in 14% and were variable in 11%, i.e. they regressed, recurred and regressed again (Gupta PC et al, 1980). The regression rates were higher when the habit was discontinued or reduced substantially. Malignant transformation was observed for 0.3% of the palatal lesions. In a 10-year intervention study in the same area, the malignant potential of various components of palatal changes was evaluated: red areas and patches were found to exhibit a high potential for malignant transformation.

Palatal Erythema

This lesion is marked by a diffused erythematous hard palate, occasionally extending to the soft palate.

Epidemiology

Of the 69 lesions observed among 7,216 tobacco users, 87% occurred among smokers, especially bidi smokers.

Clinical Aspects

This lesion occurs either independently or sometimes with other lesions. About 10% of the lesions were associated with palatal papillary hyperplasia and 25% with central papillary atrophy of the tongue and bilateral commissural leukoplakias. This triad of lesions is comparable to the multifocal candidiasis described in western literature.

Natural History

The highest percentage of persistent lesions (60%) was seen among people who did not give up their smoking habits, while the highest percentage (75%) of regressed lesions occurred among those who discontinued or reduced smoking substantially. These observations clearly indicate that palatal erythema is caused by smoking, particularly bidi smoking. None of the lesions progressed to cancer.

Central Papillary Atrophy of the Tongue

This lesion has also been described in the literature as median rhomboid glossitis and localized atrophy of the tongue papillae. It consists of a well-defined, oval, pink area in the center of the dorsum of the tongue devoid of lingual papillae.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of this lesion in the general population was 1%; it was present among 2.2% bidi smokers, 1.6% cigarette smokers and 0.3% of nonsmokers of tobacco. In a 10-year follow-up study from India, the annual age-adjusted incidence rate among smokers was 1.5 per 1000 as compared to 0.8 per 1,000 among nonsmokers.

Etiology

It is considered to be due to candidal infection, smoking or both (bidi smoking). Interestingly, very few women had this lesion due perhaps to the rarity of smoking among women.

Histologic Features

This lesion was marked by the absence of tongue papillae, the presence of slight parakeratinization of the epithelial surface, long slender rete ridges and occasional pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, chiefly of lymphocytes, was usually present within the epithelium and in the lamina propria. Candidal hyphae were observed in the superficial layers of epithelium in the majority of cases.

Lesions Associated with Betel Quid Chewing (Paan-chewer’s lesion)

This lesion consists of a thick brownish black encrustation on the buccal mucosa at the site of placement of the buccal quid (Fig. 2-10). It is often seen among heavily addicted betel quid chewers. It could be scrapped off with a piece of gauze; it regresses spontaneously; more frequently when the habit is discontinued.

Figure 2-10 Tobacco pouch keratosis. A white, wrinkled change of the mucosa in the mandibular buccal vestibule secondary to the use of chewing tobacco (Courtesy of Dr Regazi JA, Dr Sciubba JJ and Dr Pogrd MA).

Epidemiology

The annual age-adjusted incidence rate of this lesion was 28 per 1,000 among male chewers and 17.4 per 1,000 among female chewers (Gupta PC et al, 1980).

Oral Lichen Planus-like Lesion (Lichenoid reaction)

A characteristic lesion consisting of white, wavy, parallel, nonelevated striae that do not criss-cross (as in lichen planus) is observed in habitual betel quid chewers. Sometimes, these striae radiate from a central erythematous area at the site of placement of the betel quid.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of this lesion among 5,099 individuals in Ernakulam, Kerala was 0.7%. About 89% of the lesions occurred among betel quid chewers and 11% among people with mixed habits. The annual age-adjusted incidence rates among men and women were 0.7 and 2.2 per 1,000 respectively. The peak incidence for women was in the 45–54 year age group. The incidence was zero among smokers and nonusers of tobacco; and 4.3 per 1,000 among women who chewed. This lesion is thus entirely associated with betel quid chewing.

Clinical Aspects

The lesion always occurs on the buccal mucosa and mandibular groove, areas which are in intimate contact with the betel quid.

Histologic Features

The lesion shows parakeratinized, atrophic epithelium, liquefaction degeneration of the basal cell layer and a band-like inflammatory cell infiltrate containing lymphocytes and plasma cells. Unlike lichen planus, this lesion shows hyperparakeratosis, and plasma cells in the juxtaepithelial region.

Oral Submucous Fibrosis