The social context of behaviour

The material in this chapter will help you to:

describe the social model and the social determinants of health

describe the social model and the social determinants of health

understand the history and evidence leading to a social model of health as a counter to the biomedical model of health

understand the history and evidence leading to a social model of health as a counter to the biomedical model of health

evaluate the social justice argument in support of a social model of health and the implications for government policy

evaluate the social justice argument in support of a social model of health and the implications for government policy

examine the relationship between the structural and the intermediary determinants of health as a way of understanding the relationship between the social determinants of health and psychological and behavioural explanations of health.

examine the relationship between the structural and the intermediary determinants of health as a way of understanding the relationship between the social determinants of health and psychological and behavioural explanations of health.

Introduction

In Chapter 4 it was argued that the biomedical model of health was inadequate in explaining the patterns of mortality and morbidity for populations and individuals. A biopsychosocial model of health was proposed and a brief outline of the social determinants of health presented. This chapter takes the ‘social’ aspects of the biopsychosocial model of health and examines the evidence, debates and theories that argue that illness and disease for individuals, populations and nations is not simply a matter of germs and viruses (biomedical) or individual psychology and behaviour (biopsychological) but a complex interaction between the social system of a given society and the individual (biopsychosocial) and their particular genetic inheritance (biomedical).

Traditionally there has been a stand-off between biomedical, biopsychological and social models of health. This stand-off is counterproductive and contrary to the evidence. Over the past three decades particular population groups within affluent nations have failed to make the promised biomedical and health promotion gains (Raphael et al 2005). Evidence of this has been obtained from long-term studies of health differences between sections of society in Western nations (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006, World Health Organization (WHO) 2008). Comparisons of health outcomes between individuals and nations have shown that although baseline improvements in life expectancy, infant mortality and death from childhood injury have occurred in countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and the United States, there are marked differences in health status between individuals in these countries, as well as marked differences between countries (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006, WHO 2008).

These differences appear to be the result of life chances and the kind of social institutions and welfare policies a country has. For example, in the Scandinavian countries, while the gains in health have mirrored those in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and the United States, the population as a whole has made further health gains as the percentage of people on low incomes is lower than in English-speaking countries (Raphael 2006). This is best explained through the kinds of social policies in place in the Scandinavian countries.

The social model of health and the social determinants of health

The social model of health

There are two major components to a social model of health. First, health and illness are seen to be partly attributed to the social circumstances of individuals and populations. These social circumstances include their level of income in absolute terms and relative to other people in the population, their education, employment, gender, culture and status. Epidemiological evidence provides clear proof of differences in health status between individuals based on these factors. For instance, research on the social gradient (one of the social determinants of health) explains how the perception of one's social position can be a predeterminant of a chronic stress response that may create long-term physical and psychological illness (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006).

The second aspect of the social model of health suggests that the health of individuals and populations is influenced by the social, economic, political and welfare policies of a country. This includes policies covering: taxation; welfare payments and eligibility; public services such as health and education; and employment opportunities. A social model of health means that governments need to focus on policy at all levels, not just health policy. This is referred to as intersectorial collaboration across policy portfolios or a ‘whole-of-government approach’ to health.

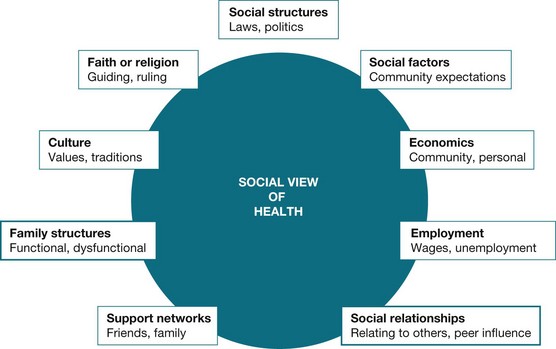

Figure 5.1 illustrates the complex and multifaceted view of health portrayed by the social view of health. It incorporates the social, cultural, community, familial and economic circumstances that influence and determine health status.

The implications of the social model

The implications of taking a social model approach to health is that rather than focus solely on the individual's behaviour or their biological or genetic attributes, the focus shifts onto the attributes of society such as the level of wealth, differences in income, poverty and government policies dealing with these inequalities. This differs from the biomedical model that defines illness as a condition of the individual who may now have a disease or injury. It also differs from the biopsychological or behavioural model of health that suggests many illnesses result from the interaction between physical factors and the behaviour of individuals with the responsibility for treatment residing solely with the individual.

The difference can clearly be seen if we take the example of a student with the disability of cerebral palsy. In a biomedical analysis the individual has ‘cerebral palsy’, uses a wheelchair and therefore is not able to attend lectures due to the cerebral palsy. Conversely, the social model would assert that as the lecture theatre does not have wheelchair access, the person is discriminated against and denied access due to lecture theatre design. The social model acknowledges and describes aspects of life that are external to the individual that mediate how the individual can function and participate within a society. Clearly, in this example, the solution lies in government policy legislating equal access, building design and adequate funding. Illness and health are therefore tackled through social interventions.

A social model of health identifies the social determinants of health

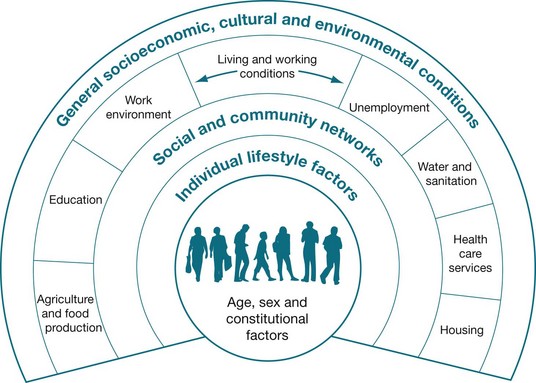

The factors that make up the social model of health are known as the social determinants of health (SDH). These SDH explain the differences in health outcomes between individuals and populations. Each social determinant of health describes a set of circumstances that influences a particular health outcome. The SDH listed in Figure 5.2 were developed by Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991). In their model there are four layers of influence: individual lifestyle factors followed by three layers of social determinants. The first or outer layer includes the socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions; the second layer includes agriculture and food production, education, the work environment, unemployment, sanitation and water supplies, healthcare services and housing. Dahlgren and Whitehead add a third layer that suggests that social networks also impact on health outcomes. It is not until the fourth layer that the individual and their behaviour are listed. This diagram is not simply a listing of features in a society. The authors are suggesting that the outer layers are features of a society that determine the health of its members and that each layer shapes the next inner layer.

Other theorists have suggested alternative social determinants. These include childhood poverty, differences in social class between groups, stress (Marmot 2001), social exclusion, unemployment (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006), type of work (Bartley et al 2006), lack of social support (Stansfeld 2006), social patterns of addiction (Jarvis & Wardle 2006), quality and quantity of food supplies (Robertson et al 2006) and transport (McCarthy 2006).

Figure 5.2 and the brief outline above have highlighted how complex and interdependent the SDH are. The SDH also provide a means of addressing inequalities in health outcomes in a manner that the biomedical model of health cannot. For example, by providing affordable, reliable, public transport to outer suburbs, a number of the social determinants could be addressed, such as access to health services. This is because transport contributes to a reduction in social isolation, increases the chance of people entering a city for employment and increases the opportunities to access health services. Thus, one government policy action can have a flow-on effect.

The history and the formation of the social determinants of health

The acknowledgment of the importance of the social model of health was demonstrated with the formation of WHO in 1948. The WHO constitution clearly outlines the need for a whole-of-government approach to health. Unfortunately, in the following 30 years governments around the world pursued a technologically driven model of health that only addressed the downstream, curative approach of health (Solar & Irwin 2007), thus failing to direct health policy towards the upstream, structural determinants of health. The term structural is used here to make the point that the problem lies in the organisation of a society or group, not in individual behaviour.

The 1978 Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care and the Health for All movement attempted to revive action on the SDH through promoting a social model of health. While many governments in principle embraced the Health for All concepts and acknowledged the importance of incorporating a broader view of health that addressed aspects such as housing, education and employment on health (Solar & Irwin 2007), neo-liberal economic policies were gaining favour. The neo-liberal policies encouraged governments to reduce public spending on health, housing, employment and other welfare services, turning away from a social model.

However, work defining and refining the social model and the SDH has continued. The previously mentioned deficits in the biomedical model of health were highlighted by the seminal work of McKeown and Illich (Solar & Irwin 2007) and the Black Report in the United Kingdom (Turrell et al 1999). The works of McKeown, Illich and Black (and his colleagues) were instrumental in highlighting the gaps in health outcomes of population groups that were directly related to social conditions (Black et al 1980, Kelly et al 2006, Turrell et al 1999). The SDH have again risen to prominence in light of the mounting evidence that the efficiency models of the neo-liberal economic policies are exacerbating the health differences between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’ such that, in Australia, there is now a 20-year mortality difference between those individuals in the highest socioeconomic group and those in the lowest (Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) 2005). In 2003 WHO created the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (Kelly et al 2006). The commission delivered its final report in 2008, which has placed the SDH and their ongoing refinement and definition firmly on the policy and research agenda (WHO 2008).

Why support a social model of health? The social justice argument and the implications for government policy

Health as a human right

As health professionals and as a society it is important to qualify our notions of health and the availability of health services. One way of achieving this is through defining and understanding health as a core value or human right. Values can be defined as:

… the beliefs of a person or group which contain some emotional investment or [are] held as sacrosanct; while core is the most essential or vital part of some idea.

The idea of health as a core value is espoused in the notion of health as a human right, as this places health as a central ideal and a ‘right for all’ (Lie 2004). If health is a right for all humans then it falls outside the individual to solely provide for it and becomes a joint responsibility of the individual and the government or society to provide. As a right for all, the provision of health becomes an entitlement and therefore falls on governments to ensure adequate provision (Baum et al 2009). By viewing health as a human right it enables governments to legislate to protect those rights and enables service providers to broaden the constructs of health to be inclusive of social conditions such as housing and education.

Health as a right ensures equity

When governments incorporate health as a human right into their policy agenda the advancement of health equity is also ensured (Lie 2004). Where health is a human right, health services are provided regardless of people's socioeconomic position, gender, educational level, ethnicity or religion (Baum et al 2009, Solar & Irwin 2007). To charge people for health services is to charge them for something that is regarded as a right. Unfortunately, in many countries where healthcare is not free, factors such as socioeconomic position determine the level of health that can be enjoyed by an individual (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006).

Theoretical models for understanding the social determinants of health

If morbidity and mortality rates for a population are a result of social conditions it is important to identify what these SDH are and to introduce policy that will reduce the impact. One approach is to examine each SDH for how it impacts on health status and to make recommendations for the kind of social policy required to eliminate the negative effects (Raphael 2006). A number of social epidemiologists have taken this approach by identifying a range of social determinants they view as important in the higher rates of morbidity and mortality of some population groups.

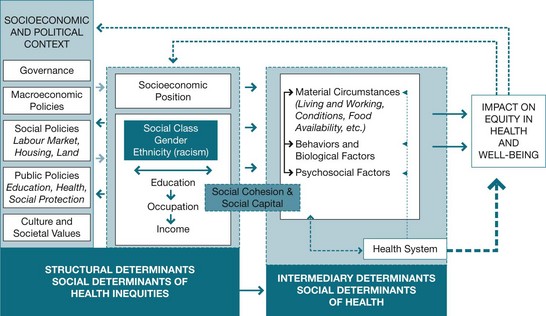

Drawing on the work of these theorists the WHO Commission for the Social Determinants of Health has developed a model that integrates the social with the psychological model to form an explanatory psychosocial model. The psychosocial model acknowledges that there is a pathway or conduit between the social factors and the individual, their behaviour and mental states that influence health. This model is divided into three components: (1) the socioeconomic and political context, (2) the structural and (3) the intermediary social determinants of health.

The socioeconomic and political context

The first factor impacting on the SDH is the socioeconomic and political context of a society. While this refers to the impact of the political and cultural system of a society on the health of the population, it is best understood in concrete terms as the impact of economic, social and public policy on the life chances of the population. Examples of economic policy include those governing industrial relations such as rates of pay and the casualisation of work for young people, including hours of work.

Social policies include those dealing with welfare issues such as access to housing, disability, old age and sickness benefits, while public policies cover issues such as access to education, the provision of healthcare and utilities such as power, water and communications. Policies that enable poor people to access resources such as power, water, education and healthcare, or protect workers from discrimination, or support workers during times of unemployment go some way towards achieving a reduction in inequality.

The kinds of policies a particular government puts in place will be very much influenced by its politics, values or beliefs. For example, where the political party in power believes health or education are human/citizen rights these services will be provided free by the government or at a cost that all can afford. Providing such services is referred to as the welfare state. Underpinning the welfare state is the idea that it is the responsibility of government to provide for its citizens' social insurance against hardship, poverty, illness or misfortune. The role of the welfare state is to redistribute the resources within a society from rich to poor, so that no one is destitute. This is usually done through taxation policies whereby everyone (rich and poor) subsidises those in need. The type and range of welfare provided by countries differs. A classic example is in healthcare. Some countries provide free, universal healthcare to all citizens; other countries have healthcare systems where patients must pay for the service, while elsewhere access to health services may be means tested or based on income.

The health impact of such policies is illustrated in the differences in mortality rates between the United Kingdom (free universal healthcare to all), the United States (private system with access to free healthcare means tested in its extension to the poor and elderly only) and Australia with a mixed public–private system. In 2007 the probability of a child under five years of age dying was 6/1000 in the United Kingdom and Australia and 8/1000 in the United States. These differences, while not stark, are explained partly as a result of healthcare policy where access to care is free in Australia and the United Kingdom, but not so in the United States (World Health Statistics 2007).

Structural and intermediary determinants

The SDH can be further categorised into those determinants that are ‘structurally’ produced and addressed through changes at a societal level via policy intervention and those determinants that act more directly on individuals and are ‘intermediary’ determinants that can be addressed through community health programs and individual health interventions and behaviour change (Solar & Irwin 2007). Dividing the SDH into these two categories makes health-promoting action clearer. The necessary policy for creating a healthy environment becomes evident whether this is through policy directed towards alleviating poverty (structural) or programs to help individuals change their behaviour (intermediary). The pathway between the structural and intermediary also goes some way to integrating the social and psychological.

Structural determinants of health inequities

Structural determinants are those factors that generate or reinforce social divisions and power and status differences in a society, and as a result impact on people's life chances (Solar & Irwin 2007 p 26). The key to understanding the structural determinants lies in the concept of social stratification (Solar & Irwin 2007). Social stratification is the division created in a society between different groups. It can be based on income (class), gender, ethnicity, sexual preference, education or occupation. These factors describe one's social position in a society (Solar & Irwin 2007). Forms of social stratification differ between social and cultural groups but in all cases impact either positively or negatively on an individual's access to resources, education and employment and, ultimately, health.

The difficulty with using a measure such as social stratification is that it does not tell us how differences in status impact on health. Understanding the SDH requires more than identification – the pathway between each determinant and illness must also be understood or, if not completely understood, explored. A number of the social determinants described below can be broadly defined using the term socioeconomic position. This term has its origins in two theoretical positions: the first Marxist, the second Weberian. The first refers to social class. A person's social class tells us how much money they earn and have to use in their daily life. For example, they may own their own business, be a manager, boss or worker. A person who owns their own business has more control over their work than a person who works for an owner. In some cases their take-home money may be very similar but one gives the orders and the other performs the tasks. Influential studies by Michael Marmot (2001) have shown that even well-paid workers who must take orders from more senior managers have higher rates of illness. This would appear to be best explained by their lack of power in the workplace. This lack of power appears to impact on stress levels leading, for example, to higher rates of mental illness and heart disease (Marmot 2001). Marmot and his colleagues are continuing to work on understanding the pathway between the stress caused by lack of power and the consequent impact on morbidity and mortality levels for these populations.

Measuring socioeconomic position simply through one's class and power in the workplace is limited. There are other ways to access power besides money. These other variables include status (one's social power) and political affiliation. This theory was first described by Weber. An example of status power would be being a boy in a society that valued boys over girls, belonging to a religious or ethnic group that had access to all the best jobs or having a job with high prestige so one's opinion was more valued than lower status occupations. Political party power refers to one person's access to resources through affiliations with powerful groups or organisations. When sociologists combine class power (whether one is a worker or owner) with status power (social prestige) and political power (one's affiliations to powerful groups) they use the term socioeconomic position. The variables outlined below all contribute to one's socioeconomic position. The first is income.

Income

Income is the measure of the amount of money available to individuals and families to purchase the material assets necessary for life. These include food, healthcare, shelter (housing), employment and any other assets considered essential in that society. It is a commonly used indicator of socioeconomic position in society. Income has a direct positive relationship with health; as income improves, health improves. Correspondingly if income decreases, health decreases (Baum 2005). Income determines the amount of material wealth available to an individual or a family, as well as access to healthcare. It enables access to good food and determines the resources available to the children within the family. Adult health outcomes begin in childhood so that income and health have a cumulative effect over the lifespan (Blane 2006, McLaughlin et al 2011). The relationship between income and health status in Australia is evident across a variety of diseases. Poorer people have higher rates of arthritis (22% compared with 16%), higher rates of musculoskeletal problems (21% versus 17%) and higher rates of mental illness (16% come from disadvantaged areas and 9% from advantaged areas) (ABS 2006, 2009). Further, McLaughlin et al (2011) found that childhood socioeconomic status impacts on the onset, persistence and severity of mental illnesses.

Social class

Social class is closely related to income. One of the most intriguing findings related to social class has been the impact of the social gradient. This finding suggests that the steeper the income and social distance between people in a society, the wider the health gaps (Morrissey 2006). The impact of income differences is seen as one of the explanations for the poor health status of Aboriginal people in Australia. The income of Aboriginal people is higher than population groups in many underdeveloped countries, yet their mortality rates are higher. One explanation is that while Aboriginal people are not as poor as some population groups in Africa or Asia, the difference between Aboriginal people and non-Indigenous Australians is significant and a factor in explaining their poor health status (Morrissey 2006, Vos et al 2009). The link here may be one of comparison and it is through comparison that stress levels are affected and ill health results.

Education

Formal education is a reflection of both a child's and parents' circumstances. The kind of education an individual achieves is determined by their parents' social position, values and income. It is also determined by the social policies of the country. Where education is provided free, individuals have the opportunity to gain an education independent of parental income or values; where it is costly, their education will be determined by their parents' wealth or opinion about the value of education. Education as a variable of health status is a combination of both the baseline education (received during childhood and a result of the socioeconomic position of parents) and future education (one's own socioeconomic position) as an adult (Solar & Irwin 2007). It also influences occupational and employment outcomes, further impacting on access to healthcare and health resources as an adult. Education also enhances an individual's capacity to make healthy life choices because it exposes the adult to an array of health resources and services (Solar & Irwin 2007).

Occupation

Occupation is the type of work performed by an individual. It is an indicator of the amount of exposure to risk, social standing, income and level of education (Marmot et al 2006). Categorisation of individuals by occupation is a powerful predictor of inequalities in morbidity and mortality, especially workplace injury (Wadsworth & Butterworth 2006). Occupation also reflects one's social standing or value in a society and may result in access to privileges such as: better education, healthcare and nutrition; housing and community support; and facilities. Occupation may also provide the person with beneficial social networks and control and autonomy over their work. There is considerable research that suggests control over one's work reduces stress and impacts directly on health (Brunner & Marmot 2006, Marmot 2001).

Gender

All around the world women have less access to and control over resources such as health (female infanticide, genital mutilation, deliberate female underfeeding), income (economic dependency, lack of well-remunerated and secure employment or active discrimination in employment positions), education (nil or limited access to education) and housing (inability to inherit or secure housing without male support), and this has implications for the quality of life experience and health status (Solar & Irwin 2007). However, in Australia and New Zealand women have lower rates of mortality (they live longer) but higher rates of morbidity (they appear to be sicker) so the solutions are not clear cut. For example, in New Zealand the life expectancy for a male is 77.9 years but increases to 81.9 years for women (The Social Report 2007). Social stratification based on gender can only be addressed ‘upstream’ or structurally by governments through policy that legislates against gendered discrimination (Johnson et al 2006).

A caveat is worth noting at this point. Health inequities based on social stratification such as gender are unfair and unjust because they are socially produced, but they do not explain all variations in the health between men and women within a country. For example, differences in rates of prostate cancer between males and females are a consequence of being male rather than any inequity between men and women, since women do not have prostate glands (Braveman 2004). This is a difference based on one's sex. However, gender differences in health, such as the differing immunisation rates for boys over girls, is a clear form of social stratification causing health inequality (Braveman 2004).

Ethnicity

Similar to gender, ethnicity is a social construct (Solar & Irwin 2007). The active exclusion of particular groups due to their race/ethnicity has consequences for both psychological and physical health and is a result of discrimination (Nazroo & Williams 2006). Discrimination also impacts on access to income and stable employment (Nazroo & Williams 2006). Currently in Australia the life expectancy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders is almost 20 years behind non-Indigenous people (AIHW 2011, RACP 2005, Solar & Irwin 2007). For example, inequalities exist for Aboriginal people in South Australia across every variable of age and environment (Glover et al 2006). Further, Aboriginal people have the highest levels of disadvantage regarding life expectancy and this is reflected in that fact that an Aboriginal man has 18 years less life expectancy than the population average, while the most disadvantaged non-Indigenous male population groups have only 3.6 years less life expectancy than the population average (AIHW 2011). As discrimination is a structurally defined social and cultural concept, research and policy directives are hard to determine due to the intertwining nature with other aspects of stratification such as education, housing, health, employment and income. For example, the statistics noted above about gender differences in life expectancy need to be changed to accommodate ethnicity. In New Zealand life expectancy for M ori males is 69 years and 73.2 years for females (The Social Report 2007). In both cases there is up to an eight-year difference between M

ori males is 69 years and 73.2 years for females (The Social Report 2007). In both cases there is up to an eight-year difference between M ori and non-M

ori and non-M ori. It is the responsibility of governments to legislate against this active discrimination.

ori. It is the responsibility of governments to legislate against this active discrimination.

Intermediary determinants of health inequities

The intermediary determinants form the bridge between the structural determinants and the individual manifestations of the health inequalities (Solar & Irwin 2007). While social epidemiologists differ on what to include in the intermediary determinants of health, Solar and Irwin (2007) note the following: (1) material circumstances; (2) the social environment or psychosocial environment; (3) behavioural and biological factors; (4) the quality of the welfare-state aspects of the health system of the country; and (5) two cultural variables – social capital and social cohesion.

Material circumstances refer to aspects of the physical environment such as the quality of housing and access to transport, food and neighbourhood resources. Considerable research has been conducted to illustrate the impact of these factors on health. For example, people living in remote regions of Australia have higher rates of morbidity and mortality than people living in urban areas. There are many explanations as to why but at the intermediary level they have limited access to fresh foods and will often have to pay a higher price than people in cities. In cities supermarkets are often more numerous and better placed in high-income suburbs than in poorer neighbourhoods (Melchers et al 2009, Smith et al 2004), resulting in poorer people paying higher prices or having to travel further. The Research focus below provides an example of this.

Social, environmental or psychological factors include the stress of debt linked to poverty, uncertainty about employment and the impact of income differentials across a society discussed earlier. Material circumstances leading to overcrowding may also generate increased domestic violence or crime in the area, further impacting on the psychological health and wellbeing of the population. Behavioural and biological factors include the prevalence of smoking, alcohol consumption and eating patterns. Research demonstrates differences in these lifestyle factors based on socioeconomic status. The exact causal link between behaviour and illness is complex and not clearly understood. While there does appear to be a cultural factor, whereby poorer people are more likely to smoke, be physically inactive or have a poor diet, it would appear that there is also a stress factor associated with other aspects of their living conditions. For example, smoking may be a response to stress, and a diet high in saturated fats may lead to higher rates of heart disease. It is also possible, however, that stress linked to a social issue such as unemployment may activate the hormonal system, leading to high blood pressure (Brunner & Marmot 2006).

The resources and structure of the health system itself are intermediary factors (Solar & Irwin 2007) already explored. Countries with free universal health services usually have lower mortality and morbidity rates than those that rely on a market-based healthcare system where the consumer must pay for all services. The impact of the healthcare system goes beyond providing free access to acute medical services. It includes public health measures such as free immunisation and adequate financial support for those with chronic illness, those with a disability or those in need of rehabilitation.

The final intermediary determinant refers to social capital and social cohesion. Briefly, it is argued that population groups that have access to social networks, friends, neighbours and relatives who can assist them to improve their economic conditions have better health outcomes. Communities where there is a strong sense of collaboration and trust are also likely to enjoy better health. Importantly, these cultural factors cannot substitute for sound policy and structural reform.

The intermediary determinants create a causal chain of influence over the lifespan (Solar & Irwin 2007). The intermediary determinants provide the means of direct intervention (Solar & Irwin 2007). Interventions can be through direct policy or through health promotion initiatives that assist individuals and communities to change their behaviour. Clearly health promotion activities need to take account of the structural factors. Blaming poor people for their health status denies the causal factors found in their material circumstances and its subsequent stress. Figure 5.3 consists of all the SDH that interact to determine health outcomes for individuals. This overriding final framework devised by Solar and Irwin for the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health explains and visually represents the determinants that are currently used to inform WHO's research and policy recommendations (Solar & Irwin 2007).

Figure 5.3 Framework for the social determinants of health Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice), ISBN 978 92 4 150085 2, © World Health Organization 2010

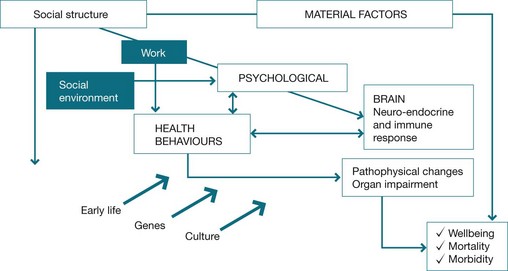

Social determinants of health and psychology

While there is irrefutable evidence that socioeconomic position impacts on health, the exact biopsychosocial pathway from the structural and intermediary determinants to the presence of physical illness, mental illness or disease within an individual's body or in an entire population is only just beginning to be investigated. Understanding how it is that low income or discrimination based on gender or ethnicity means higher mortality or morbidity is difficult to explain. A number of theories are proposed. These include explorations of the impact of the human fight or flight response on hormonal levels, metabolic rates or endocrine transmitters. The argument suggests that people in low socioeconomic groups are overloaded with psychological fight or flight demands (Brunner & Marmot 2006). This is covered in more detail in Chapter 10. Brunner and Marmot also suggest high levels of stress may make poorer people more susceptible to infection as a result of immune compromise. It is not our intention to describe the range of possible pathways as it is beyond the remit of this chapter. However, Figure 5.4 illustrates the connections between different factors in life and the psychosocial outcomes for individuals.

Figure 5.4 Connections between life factors and their psychosocial outcomes Brunner E, Marmot M 2006 Social organization, stress and health. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson R (eds) Social determinants of health. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Further, mental illness correlates with social patterns. Poorer people are likely to have higher rates of mental illness; this has been highlighted by several studies (Draine et al 2002, Heneghan et al 2006, McLaughlin et al 2011, Petrilla et al 2005). Biopsychological illnesses follow distinct social boundaries, with those in the lowest income quintile having a much higher incidence of mental and physical illness. For example, 34% of the population with mental illnesses are people living in one-parent households, while only 55% of people with a severe disorder are employed (Australian Government 2010 p 35). Draine et al's (2002) research highlights the improvements in mental illness outcomes following the implementation of a program that addressed social disadvantage. Draine et al (2002) assert that programs that do not address the social causes and the sociopolitical context of psychological illness perpetuate and maintain these illnesses.

Conclusion

This chapter first clarified the aspects of health external to the individual and individual health behaviours that determine health outcomes. The social model of health broadens the view of health beyond both the biomedical model and the biopsychological model to examine the influences on health that are determined by social circumstances. The social aspects of health have formed the basis of the SDH. The chapter argued that the social model of health suggests that health is a human right and responsibility for providing the determinants of health resides with governments as well as individuals.

In the second section of the chapter the SDH, such as education, income, gender, ethnicity and social class, were outlined. Those SDH that are described as structural are directly influenced by the social and political environments and institutions within society, and can be addressed by changes to policy in the areas of health, education, housing and so on. The SDH that are intermediary in nature are downstream and closer to the individual, and are addressed through community and individual health interventions. Both the structural and the intermediary SDH have short- and long-term effects on the physical and psychological outcomes of citizens within a society and mediate the level of health that can be attained. Importantly, the social determinants present health professionals with a dilemma. Having diagnosed, treated and cured the illness or disease, health professionals know that in many instances they discharge the patients back into the same illness-producing social system. Consequently, health professionals need to be social reformers!

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). National health survey: summary of results, Australia 2004–05 Cat. No. 4364.0. Canberra: ABS; 2009.

Brunner, E., Marmot, M. Social organization, stress, and health. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. 2006. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Jarvis, M.J., Wardle, J. The life course, the social gradient and health. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Marmot, M., Siegrist, J., Theorell, T. Health and the psychosocial environment at work. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. 2006. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Nganampa Health Council, South Australian Health Commission and the Aboriginal Health Organisation of SA. Uwankara Palyanyku Kanyintjaku report: an environmental and public health review within the Anangu Pitjantjatjara lands. Adelaide: UKP Report; 1987.

World Health Organization (WHO). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

World Health Organization report into health inequities

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf

The final report from the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health discussing the disparities between population groups and the action required to address these health inequities.

World Health Organization report into the social determinants of health

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/interim_statement_eng.pdf

This report outlines the social determinants of health and discusses their sociopolitical context, offering various theoretical explanations for the occurrence of the SDH. It also includes suggestions for researching the SDH and the policy actions required to address the SDH.

World Health Organization statistics

www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/en

This report presents the statistics from 193 states on healthcare within nations covering material wealth, preventable diseases, mortality rates and health trends.

http://www.publichealth.gov.au/publications/a-social-health-atlas-of-australia-[second-edition]—volume-1:-australia.html

This report describes the social aspects of Australia and provides information collected over several years outlining the disparities between population groups within Australia.

www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz/health

This webpage features the health section of The Social Report, outlining the disparities and deprivation that occurs between people within New Zealand. It includes information such as avoidable deaths, levels of education and other factors that determine an individual's wellbeing and health.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Musculoskeletal conditions in Australia: a snapshot 2004–05. Canberra: ABS; 2006.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), National health survey: summary of results, Australia 2004–05 Cat. No. 4364.0. ABS, Canberra, 2009.

Australian Government, The changes to Medicare primary care items. Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra, 2010. Online Available www.health.gov.au/internet/mbsonline [10 Mar 2011].

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Comparing life expectancy of indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States: conceptual, methodological and data issues. Cat. no. IHW 47. AIHW, Canberra, 2011. Online Available http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737420537 [25 Sep 2012].

Bartley, M., Ferrie, J., Montgomery, S.M. Health and labour market disadvantage: unemployment, non-employment and job insecurity. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Baum, F. Who cares about health for all in the 21st century? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005; 59:714–715.

Baum, F., Begin, M., Houweling, T., et al. Changes not for the faint hearted: reorienting healthcare systems towards health equity through action on the social determinants of health. American Journal of Public Health. 2009; 99(11):1967–1974.

Black, D., Morris, J.N., Smith, C., et al. Report of the working group on inequalities in health. London: Stationery Office, Department of Health and Social Security; 1980.

Blane, D. The life course, the social gradient and health. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Braveman, P. Defining equity in health. Health Policy and Development. 2004; 2(3):180–185.

Brunner, E., Marmot, M. Social organization, stress and health. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Dahlgren, G., Whitehead, M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm: Institute for Future Studies; 1991.

Draine, J., Salzer, M., Culbane, D., et al. Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2002; 53(5):565–573.

Glover, J., Hetzel, D., Glover, L., et al. A social health atlas of South Australia, third ed. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide; 2006.

Heneghan, C.J., Glasziou, P., Perera, R. Reminder packaging for improving adherence to self-administration of long-term medications. Cochrane Database System Review. (1):2006. [CD005025].

Jarvis, M.J., Wardle, J. The life course, the social gradient and health. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Johnson, M., Mercer, C.H., Cassell, J.A. Social determinants, sexual behaviour and sexual health. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Kelly, M.P., Bonnefoy, J., Morgan, A., et al. The development of the evidence base about the social determinants of health. World Health Organization Commission of Social Determinants of Health Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

Lie, R.K. Health, human rights and mobilization of resources for health. BMC International Health and Human Rights Journal. 2004; 4:4–12.

Marmot, M. Aetiology of coronary heart disease: foetal and infant growth and socioeconomic factors in adult life may act together. British Medical Journal. 2001; 323:1261–1262.

Marmot, M., Siegrist, J., Theorell, T. Health and the psychosocial environment at work. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. 2006. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

McCarthy, M., Transport and health 2006Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

McLaughlin, K.A., Breslau, J., Green, J.G., et al. Childhood socio-economic status and the onset, persistence and severity of DSM-IV mental disorders in a US national sample. Social Science & Medicine. 2011; 73(7):1088–1096.

Melchers, K.G., Klehe, U.-C., Richter, G.M., et al. I know what you want to know: the impact of interviewees’ ability to identify criteria on interview performance and construct-related validity. Human Performance. 2009; 22:355–374. [doi:10.1080/08959280903120295].

Morales, F., Gilner, L. Sage English dictionary 2002. Computer program. London: Sage; 2002.

Morrissey, M. The Australian state and Indigenous peoples 1990–2006. Journal of Sociology. 2006; 24(4):347–354.

Nazroo, J.Y., Williams, D.R. The social determination of ethnic/racial inequalities in health. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Nganampa Health Council, South Australian Health Commission and the Aboriginal Health Organisation of SA. Uwankara Palyanyku Kanyintjaku report: an environmental and public health review within the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands. Adelaide: UKP Report; 1987.

Pearce, M., Willis, E., McCarthy, C., et al., 2006. A response to the National Water Initiative from Nepabunna community, Report for the Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation Division of the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, South Australia, the Commonwealth Department of Family, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, CRC for Aboriginal Health, Desert Knowledge CRC and United Water.

Petrilla, A.A., Benner, J.S., Battleman, D.S., et al. Evidence-based interventions to improve patient compliance with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medications. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2005; 59(12):1411–1451.

Raphael, D. Social determinants of health: Present status, unanswered questions and future directions. International Journal of Health Services. 2006; 36(4):651–677.

Raphael, D., Macdonald, J., Colman, R., et al. Researching income and income distribution as determinants of health in Canada: gaps between theoretical knowledge research practice and policy implication. Health Policy. 2005; 72:217–232.

Robertson, A., Brunner, E., Sheiham, A. The life course, the social gradient and health. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP). Inequity and health: a call to action. Addressing health and socioeconomic inequality in Australia. Policy statement RACP; 2005.

Smith, A., Coveney, J., Carter, P., et al. The Eat Well SA Project: an evaluation-based case study in building capacity for promoting healthy eating. Health Promotion Journal. 2004; 19(3):327–334.

Social Health Atlas of Australi. http://www.publichealth.gov.au/publications/a-social-health-atlas-of-australia-[second-edition]-volume-1:-australia.html, 2011 [Online. Available 5 Mar 2011].

Solar, O., Irwin, A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Discussion paper for the Commission of Social Determinants of Health. Draft. April. Geneva: WHO; 2007.

Stansfeld, S. Social support and social cohesion. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

The Social Report New Zealan. http://www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz/health/index.html, 2007 [Online. Available 5 Mar 2008].

Tregenza, J., Tregenza, E. Cost of living on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands, Survey report. AP Services; 1998.

Turrell, G., Oldenburg, B., McGuffog, I., et al. Socioeconomic determinants of health: towards a national research program and a policy and intervention agenda. Canberra: Queensland University of Technology, School of Public Health, AusInfo; 1999.

Vos, T., Barker, B., Begg, S., et al. Burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: the Indigenous health gap. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009; 38:470–477.

Wadsworth, M., Butterworth, S. Early life. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R., eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

World Health Organization (WHO). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health, WHO commission on Social Determinants of Health. Online Available http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/en/index.html, 2008. [5 Sep 2008].

World Health Statistics. Health data and statistics. Online Available www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/en, 2007. [13 Mar 2008].