Stress and coping

The material in this chapter will help you to:

distinguish between stress as a stimulus, a process and a response

distinguish between stress as a stimulus, a process and a response

understand the effects of stress on health and illness

understand the effects of stress on health and illness

understand how cognitive appraisals and personality styles influence an individual's coping response

understand how cognitive appraisals and personality styles influence an individual's coping response

Introduction

Stress is a term that is used in everyday conversation and frequently featured in the popular media and press. It has also been the focus of psychological research for decades. The concentration of stress research has principally been in three areas, namely to examine stress as: (1) a response – the individual's reaction; (2) a stimulus – the event or stressor that prompted the reaction; or (3) a process – the transaction between the individual and the environment.

While stress is generally considered to be a state to be avoided, the experience and outcomes of stress are, nevertheless, not always negative. At times a stressful occurrence may even be welcome. Desired events like a promotion at work and getting married produce similar physical and psychological reactions, as do unwelcome events like redundancy and divorce. Furthermore, events that are ambiguous, uncontrollable, unpredictable or unrelenting are stressful, as are multiple demands that tax the individual's ability to cope (Taylor 2012).

Consider the statement ‘I am feeling stressed’. How often have you heard or said this? What does this statement mean? What causes stress and how is it experienced? Does everyone experience stress in the same way? Is stress always harmful and how can it be managed when it is excessive? The answers to such questions will be explored in this chapter. The concept of stress will be considered and factors that make an event stressful will be identified. The health consequences of stress will also be examined and finally moderators of stress will be examined.

What is stress?

Stress is a physical, cognitive, emotional and behavioural reaction of an individual (or organism) to a stressful event – stressor – that threatens, challenges or exceeds the individual's internal and external coping resources. The threat may be actual (e.g. being robbed at knife point) or perceived (e.g. a student who believes he will fail a forthcoming exam). The threat or stressor can be physically or emotionally challenging, or both. It may also be perceived as either a positive or negative event by the individual. See Table 10.1 for examples of physical and emotional stressors.

Table 10.1

| Physical stressors | Emotional stressors |

| Undergoing surgery | Diagnosis of a chronic disease |

| Insomnia | Marriage |

| Loss of eyesight | Overseas travel |

| Heat stress | Redundancy |

| Physical trauma | Relationship breakup |

| Pain | Moving house |

| Illness | Winning the lottery |

Stress prompts the individual into action. The precipitating stressor may be a major life event like a disaster such as a tsunami, or a minor life event such as daily hassles like being late for an appointment because you were caught up in traffic. Additionally the precipitating event can be viewed as negative, harmful and threatening, or challenging and exciting by the individual. Moreover, the same event may be perceived differently by different people, as evidenced by the scenario in the Classroom activity on page 224.

Stress as a response, stimulus or process

Stress is a topic of interest not only to health professionals but also to the general public, as evidenced by the number of publications on the topic in the popular psychology literature such as in self-help books, the internet and health and lifestyle magazines. Furthermore, stress is the most investigated phenomenon in health psychology research with regard to examining the relationship between psychology and disease (Contrada & Baum 2010). Despite this, not all researchers use the concept in the same way. Research that investigates the relationship between stress and health falls into three main categories that view stress as one of the following:

response – the individual's physical and psychological reaction to the stressor

response – the individual's physical and psychological reaction to the stressor

stimulus – a stressor in the environment that precipitates a stress reaction

stimulus – a stressor in the environment that precipitates a stress reaction

process – a transaction between the individual and the environment.

process – a transaction between the individual and the environment.

Stress as a response

Stress as a response refers to the individual's physiological and psychological reactions to a perceived threat or stressor, such as a student who discovers that the hard disc on their computer is corrupted and they do not have another copy of an assignment that is due that day. Physical symptoms include dry mouth, palpitations, appetite changes and insomnia, while psychological responses can include anxiety and forgetfulness and, in extreme circumstances, burnout or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Physiologists in the first half of the 20th century such as Cannon and Selye were the first researchers to describe the stress response and pioneered research in this field.

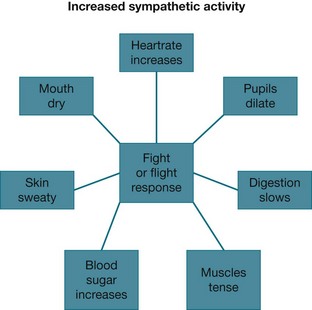

Fight or flight

Walter Cannon (1932) was a physiologist and early stress researcher who first described the fight or flight response – a primitive, inborn protective mechanism to defend the organism against harm. The response is a physical reaction by an organism (including humans) to a perception of threat. Cannon observed that when an organism was threatened the sympathetic nervous system and the endocrine system were aroused, preparing the organism to respond to the anticipated danger by either reacting aggressively (fight) or by fleeing (flight).

The physiological mechanism of this involves arousal of the sympathetic nervous system that stimulates the adrenal glands to secrete catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline), which then elevate blood pressure, increase the heart rate, divert blood supply from internal organs to muscles and limbs and dilate pupils to enable the organism to take action in the face of a threat (see Fig 10.1). Activation of the endocrine system prompts the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol, which provides a quick burst of energy, heightens alertness and memory, and increases the organism's pain threshold. Together they enable the organism to confront or withdraw from the threat.

The fight or flight response is adaptive when arousal enables the individual to take action: to either address or escape the threat. However, prolonged arousal, which is unrelenting or for which adaptation does not occur, is potentially harmful and can lead to long-term health consequences. For example, when caught speeding by a radar and pulled over by a police officer, neither fight nor flight is an adaptive response.

In the landmark Whitehall I and II studies, British civil servants in lower level jobs experienced greater stress due to having less control of their workload than higher level employees (Marmot et al 1997). Also, the final report of the World Health Organization's (WHO) Commission of Social Determinants of Health states that ‘stress at work is associated with a 50% excess risk of coronary heart disease and there is consistent evidence that high job demand, low control and effort–reward imbalance are risk factors for mental and physical health problems’ (WHO 2008 p 8).

General adaptation syndrome

Hans Selye (1956) was another pioneer stress researcher who identified the relationship between stress and illness in a model he called the general adaptation syndrome (GAS). The GAS provides a biomedical explanation of the stress response and how it influences health outcomes. The theory identifies a pattern of reaction to a threat or challenge and proposes that stress is the individual's non-specific response to the specific environmental stressor. Selye defined this as a demand on the body that induces the stress response – the individual is required to adapt (Selye 1956). GAS is non-specific in that the response is the same regardless of stimuli; that is, whether the stressor is physical or emotional or whether it is viewed as positive or negative.

The GAS includes three phases:

1. alarm reaction – in which the organism is alerted to a perceived threat

2. resistance stage – in which the body attempts to regain equilibrium and adapt to the stressor

3. exhaustion stage – occurs when the body's attempts to resist the stressor are unsuccessful.

When a threat is perceived the body's reaction is one of alarm and the individual is mobilised to take action. In this phase nervous system arousal and alterations to hormone levels prepare the individual for action. Initially this includes the activation of the autonomic nervous system, leading to adrenaline and noradrenaline being secreted by the adrenal medulla. Subsequently, the pituitary gland produces adrenocorticotrophic hormone, which stimulates the release of corticosteroids by the adrenal cortex.

With continued exposure to the threat resistance occurs. In this phase hormones remain raised and the immune system aroused as the individual takes further action to cope with the stressor. The exhaustion phase follows if the individual is unsuccessful in adapting to or overcoming the threat. Exhaustion weakens the body's defences, making the individual vulnerable to disease due to depleted physiological resources.

Despite the influence of Selye's stress response model on stress research it does not escape criticism. First, that it describes a physiological process and overlooks the role of cognitive appraisal as identified by Lazarus and Folkman (1984); second, not all individuals respond in the same physiological way to stress; and third, Selye's model refers to responses to actual stress, whereas an individual can experience the stress response to an anticipated stressor (Taylor 2012). For example, in agoraphobia the person fears the anxiety they might experience if they leave their ‘safe place’, usually their home.

In summary, the stress response is an automatic reaction that enables a person to take action in order to adapt to, or make changes in response to, a perceived or actual threat or stressor. The stress response is most effective for stressors that are of short-term duration and where adaptation is possible. However, should adaptation not be achievable or the stress prolonged, the individual is at risk of developing health problems as a consequence.

Stress as a stimulus

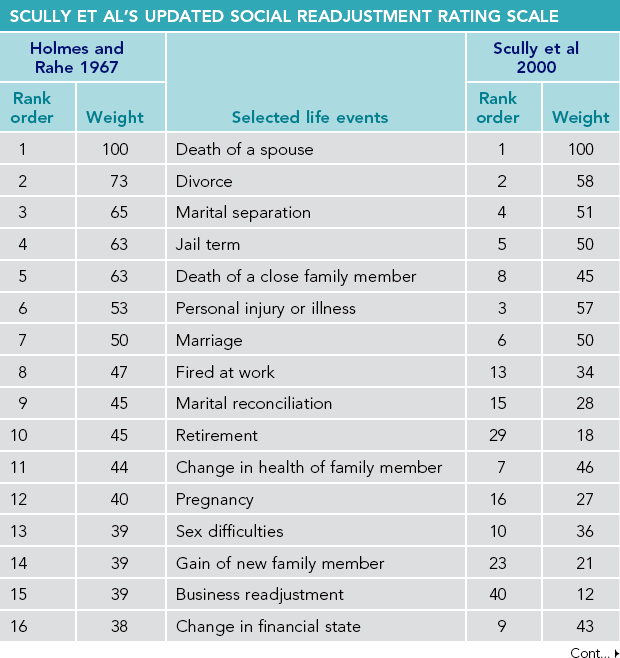

Another approach to stress research is to view it as a stimulus that produces a reaction. According to Yerkes and Dodson (1908) stress is the stimulus that prompts action and the amount of stress experienced predicts how well the individual performs. The stimulus can be a major life event such as those identified by Holmes and Rahe in 1967 (see Table 10.2). Alternatively the stimulus may be an accumulation of minor life events or hassles as described by Kanner and colleagues in a study that compared the stress from daily hassles and uplifts with the stress produced by major life events (Kanner et al 1981).

Table 10.2

SCULLY ET AL'S UPDATED SOCIAL READJUSTMENT RATING SCALE

Source: Scully J, Tosi H, Banning K 2000 Life events checklist: revisiting the social readjustment rating scale after 30 years. Educational and Psychological Measurement Vol 60 No 6, p 864–876, American College Personnel Assocation, Science Research Associates, copyright Sage Publications, Inc.

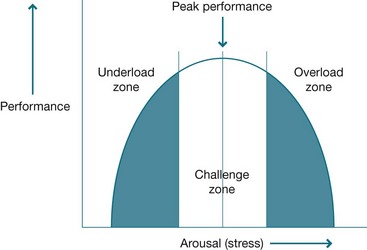

The Yerkes–Dodson law

Yerkes and Dodson (1908) hypothesised that a relationship exists between arousal and performance and that stress is a stimulus that prompts an individual to take action. According to the Yerkes–Dodson law, when stressed (aroused) an individual's performance increases to a maximum point after which performance reduces. The relationship is represented graphically as an inverted ‘U’ (see Fig 10.2).

The model proposes there is an optimal level of arousal (stress) at which an individual is challenged and thereby performs at their best. With too little arousal the individual is not sufficiently motivated to take action in response to the stimulus and hence performance is minimal. Increasing arousal energises the individual to take the action required to achieve a goal such as study to pass an exam. However, excessive arousal can result in the individual being overloaded and, consequently, performance deteriorates, such as in the case of a student who is highly anxious about a forthcoming exam and loses concentration or becomes ill.

Major life events

The theory that major life events are a stimulus for stress emerged from the research of Holmes and Rahe who hypothesised that major or frequent changes in one's life predisposes the individual to illness due to the cumulative effect of the life stressors. This hypothesis was proposed by the researchers after they observed that tuberculosis infection commonly followed a major crisis or multiple life crises. They subsequently developed a tool to measure the impact of life changes on health and to predict individual vulnerability to illness: the social readjustment rating scale (SRRS) (Holmes & Rahe 1967).

This tool consists of 43 items: 17 are rated as desirable such as going on vacation; 18 are rated as undesirable such as the death of a close friend; and eight are classified as neutral such as ‘major change in responsibilities at work’ (Holmes & Rahe 1967 p 214). Such a change may be the consequence of a promotion that is desirable but it could be the result of a restructure and reduction of staff at the workplace, which would be undesirable because there would be fewer people to undertake the workload.

Items in the SRRS are given a weighting that reflects the magnitude of the stressful stimulus (see Table 10.2). For example, the death of a spouse was found to be the most stressful life event and was given a score of 100. A score of 150–299 for the preceding year places the individual at moderate risk for illness, whereas a score of 300 in the preceding six months or more than 500 in the preceding year places the individual at high risk of developing a stress-related illness.

Since its development in the 1960s the Holmes–Rahe SRRS is one of the most widely cited tools in stress research. Thirty years later Scully et al (2000) replicated the research to examine the usefulness of the tool as an indicator of health risk and to consider the validity of criticisms raised in the literature in relation to the tool. Scully et al's research found that the relative weightings and rank order of the selected life events remained valid and concluded that SRRS continues to be ‘a robust instrument for identifying the potential for the occurrences of stress-related outcomes (Scully et al 2000 p 875). Table 10.2 compares weight and rank order for selected life events in Holmes and Rahe’s seminal study and the replication by Scully et al.

Not everyone experiences or responds to major life events in the same way, though. In a study of coping following multiple negative life events Armstrong et al (2011) found that participants were more resilient following a stressful event if they had a high score on scales for emotional self-awareness, emotional expression, emotional self-control and emotional self-management.

Minor life events

Kanner and his colleagues were interested to see if minor as well as major life events had health consequences for an individual. The researchers defined minor stressful events that were irritating or frustrating as hassles. Minor life events would cause inconvenience for the individual rather than require a major adjustment as is required with major life events (Kanner et al 1981). Examples of such stressful events include: discovering that your mobile phone battery is flat when you want to make a phone call; arriving late to watch a soccer grand final and being told that you cannot enter the stadium until half-time; or finding that an ATM machine is out of order when you need to withdraw cash. Findings from Kanner et al's research demonstrated that hassles can impact on health. This occurred when multiple hassles occurred at once or when minor life events occurred concurrently with a major life event and when minor stressful events were prolonged or repeated such as a person who was late for work three times in one week due to traffic congestion.

In summary, it is evident that both major and minor events may stimulate a stress reaction in humans that, in turn, can affect health. Nevertheless, the presence of a stressful stimulus is not predictive of how someone will respond to the stressor. Different people will respond differently to the same stressor and the same event can lead to positive or negative outcomes in different people. For example, a person who has a dog phobia will react differently from a dog lover when a dog is present. This observation prompted psychologists studying stress to examine the relationship between the individual, their perceptions and their environment, that is, stress as a process.

Stress as a process

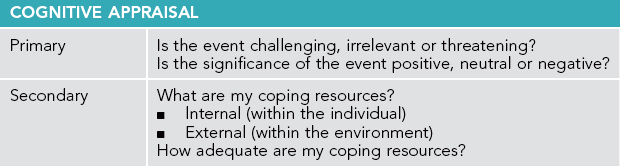

The notion of stress as a process was first introduced by Richard Lazarus and later refined in collaboration with his colleague Susan Folkman (Lazarus 1966, Lazarus & Folkman 1984). Lazarus's theory proposed that stress was a transaction between the individual and their environment. The transaction involves the individual making a cognitive assessment (appraisal) of the demands of the stressor and the coping resources available to him or her. Lazarus distinguished between stressors that are negative (distress) and positive (eustress).

In appraising an event or situation an individual will ask one of three questions. Is the event:

Lazarus's theory proposes that distress is experienced when a person perceives that a stressor is potentially negative and also believes that his or her available resources are insufficient to meet the demands of this particular stressor. Cognitive appraisal is the term used to describe the process of perceiving the stressor and of judging one's ability to manage or respond to the stressor.

Cognitive appraisal occurs at two levels: primary and secondary. Primary appraisal refers to an individual's judgment as to whether this event or situation is negative (poses a threat), positive (provides opportunity/challenge) or benign (neutral/irrelevant). Secondary appraisal refers to a person's assessment of their personal (internal) and environmental (external) resources to respond to the stressful event or situation (Lazarus & Folkman 1984). These two processes are carried out simultaneously as the person assesses the threat and their ability to manage (see Table 10.3).

Stress myths

Finally, that stress is an unavoidable consequence of modern life that produces negative outcomes is a commonly held view that is not correct. Stress is only problematic if it is perceived as such and/or has negative consequences. According to the Yerkes–Dodson law moderate stress motivates a person to make adaptive responses (see Fig 10.2). Nevertheless, myths abound about the causes, consequences and how one should respond to stress. The American Psychological Association (APA) (2012) identifies and challenges the six most common stress myths, as outlined in Box 10.1.

Effects of stress on health

Stress can impact on a person's health physically or psychologically (or both) and can have short- or long-term consequences. Physical outcomes include impaired immunity, vulnerability to infection and increased risk for cancer and cardiovascular and autoimmune diseases. Psychological consequences of excessive and prolonged stress include cognitive, emotional and behavioural problems, and in extreme circumstances can lead to disorders such as anxiety, depression or risky health behaviours like drug and alcohol abuse. Let us examine these effects in more detail.

Physical effects of stress

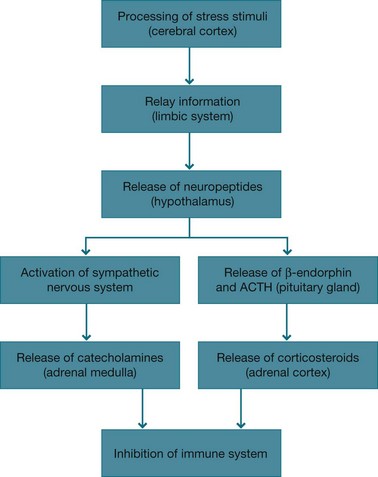

The physical functions of the body are regulated by the nervous, endocrine and immune systems. In humans the nervous system comprises the central and peripheral nervous systems. The central nervous system consists of the brain and spinal cord, the peripheral nervous system and all the other neural structures and pathways in the body. The immune system defends us against infection, including bacteria and viruses, and can protect against some cancers. The endocrine system consists of glands and organs that secrete hormones to regulate metabolism, growth and development. Malfunction in one of these systems will impact on the other systems and cause illness. For example, in a study of 33 anxious and non-anxious women, anxiety was found to be significantly associated with altered and lowered immune functioning (Arranz et al 2007); numerous studies have shown that students' immunity is compromised in the period surrounding exams (Taylor 2012).

Psychoneuroimmunology

Psychoneuroimmunology is the multidisciplinary scientific study of the relationship between the nervous system and the immune system. The term psychoneuroimmunology was coined by George Solomon in 1964, but it would be another decade before research in the field became widespread. This occurred in the 1970s following a finding by Robert Ader, an American psychiatrist, that the immune system of rats could be suppressed through classical conditioning (see Ch 1). Ader published these findings with his colleague, Cohen (Ader & Cohen 1975).

Ader and Cohen's evidence that immune functioning could be affected by the manipulation of psychological processes was a significant milestone in psychoneuroimmunology research. Subsequently, research that investigates the relationship between stress and the immune system has intensified. There is now a substantial body of knowledge to support the hypothesis that immune system alteration precipitated by psychological processes, including stress, can cause physical illness. This applies not only to illnesses that are caused by infection but also to autoimmune and metabolic diseases like multiple sclerosis, asthma and rheumatoid arthritis, and to some cancers (Irwin 2008, Kiecolt-Glasser 2009, 2010).

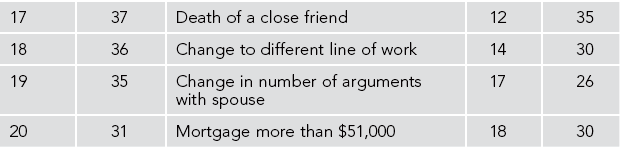

Immune system

The immune system is the body's protection against infection and illness. Its primary function is to detect foreign cells in the body and eradicate them. It consists of organs (such as the spleen) and cells (such as lymphocytes) that detect pathogens like bacteria, viruses and cancer-producing cells, and destroys them. Cells within the immune system have receptors for neuropeptides and hormones enabling them to respond to nervous and neuroendocrine system signals. Nerve fibres connect immune system organs and cells to the autonomic nervous system. Consequently the central nervous system moderates stress through changes in immune cell activity. Because the brain and nervous system are connected to the immune system by neuroanatomic and neuroendocrine pathways, immune functioning can be affected. Figure 10.3 shows the pathway for central nervous system effects on the immune system.

Figure 10.3 Inhibition of immune system From: Lewis S L, Ruff Dirksen S, McLean Heitkemper M, Bucher L, Camera I N, (eds) 2011 Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, 8th edn., Elsevier, St Louis

Immunosuppression

Immunosuppression is a consequence of stress that can result from being exposed to both short- and long-term stress. There is an extensive body of research that links stress to immune dysregulation. Effects include: reduced number and function of natural killer cells (whose role is to respond to and reject viral and tumour cells); increased production of proinflammatory cytokines (which are implicated in depression and sleep disorders); and decreased monocytes (which protect the body from foreign substances e.g. infection) (Irwin 2008). The clinical consequence of immunosuppression include chronic low-grade inflammation, delayed wound healing, poor response to vaccines and increased susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections (Gouin 2011, Irwin 2008).

Pathways between the central nervous, endocrine and immune systems travel in two directions. What this means is that not only can the central nervous system affect the endocrine and immune systems but these both have the potential to also affect the central nervous system (see Fig 10.4).

Figure 10.4 Neurochemical links between the nervous, endocrine and immune systems From: Lewis S L, Ruff Dirksen S, McLean Heitkemper M, Bucher L, Camera I N, (eds) 2011 Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, 8th edn., Elsevier, St Louis

As a consequence of the interrelationship between the three systems not only can cognitions and emotions influence immunity and endocrine function but the immune and endocrine systems can send messages to the brain and influence behaviour. For example, both adrenal corticosteroids and catecholamines can cause immunosuppression that, in turn, can lead to illness behaviour such as tiredness and appetite reduction. Also, in addition to adrenocortical hormones, other hormones including thyroid and growth, can suppress immune function.

In summary, there is now clear evidence that stress-induced immunosuppression can lead to illness. Research that identifies these links provides opportunities for intervention and prevention. Nevertheless, despite the body of research demonstrating the links between stress and illness many questions remain unanswered, namely, how much stress is required to bring about changes to the immune system and how can stress-induced immunosuppression be prevented or mediated?

Psychological effects of stress

The psychological and behavioural health effects of stress also have both short-and long-term consequences. These consequences can include cognitive changes (forgetfulness and obsessional thoughts), affective changes (anxiety and mood alteration) and changes to health behaviours (dietary changes, altered sleep patterns and increased tobacco smoking and alcohol/drug use). In the longer term unrelieved stress can have serious lifestyle consequences such as burnout and be a contributing factor in mental illnesses like clinical depression and PTSD.

Burnout

Burnout is a psychological syndrome characterised by: emotional exhaustion; depersonalisation and cynicism; and a diminished sense of self-efficacy and personal accomplishment that occurs as a consequence of prolonged chronic workplace stress (Lee & Akhtar 2011, Maslach 2003). According to Maslach (2003) anyone who works with needy people, and particularly healthcare workers, is at risk of burnout. Maslach and Jackson (1981) developed the first tool to identify burnout in human services workers. Their tool measures (1) emotional exhaustion, (2) depersonalisation and (3) reduced personal accomplishment, and has an optional fourth subscale of reduced involvement.

Burnout produces a range of negative outcomes for workers' health and wellbeing including: anxiety and depression; psychosomatic problems such as headaches; and physical health problems such as immunosuppression leading to increased vulnerability to infection (Pipe et al 2009). Other serious consequences of chronic workplace stress include hypertension, coronary heart disease, excessive alcohol use and mental illness (Hurrell & Kelloway 2007). People who work closely with others, such as health professionals, are particularly vulnerable to burnout (Glasberg et al 2007). In a study of burnout among Hong Kong nurses, Lee and Akhtar (2011) found that the ‘social context’ of nursing work was more significantly associated with burnout than the ‘job content’. They defined social context as: lack of professional recognition; professional uncertainty; interpersonal and family conflicts; tensions in work relations; and tensions in nurse–patient relations. Job content, on the other hand, comprised patient care responsibilities, job demands and role conflict. These findings have implications regarding how individual nurses and the organisations they work for address workplace stressors.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

PTSD is a serious, debilitating mental illness that affects some people who experience or witness an extremely traumatic stressful event – one which is outside the realm of usual human experience and involves the threat of death or serious injury. Examples of such events include being the victim of an assault, witnessing a person being run over by a train or the soldier in a war zone who is exposed to gunfire that results in the death and injury of colleagues and bystanders.

Features of PTSD include: insomnia; intrusive thoughts and dreams about the traumatic event; irritability and outbursts of anger; poor concentration; hypervigilance; and an exaggerated startle reflex. People with PTSD may also experience survivor guilt, relationship difficulties, detachment from loved ones, anxiety symptoms and clinical depression (Evans 2012). Furthermore, a study of Vietnam war veterans found that veterans with PTSD also had a ‘pattern of physical health outcomes that is consistent with altered inflammatory responsiveness’ (O'Toole & Catts 2008 p 33). In other words the stress experienced by these soldiers had not only produced psychological symptoms but also immunosuppression and consequent physical disorders.

While it is clear that experiencing a traumatic stressful event causes PTSD there are still many unanswered questions about this condition. In particular: Why do some people develop PTSD after an extremely traumatic event while others do not? And is stress debriefing beneficial to all victims following a traumatic stress or can this increase psychological distress?

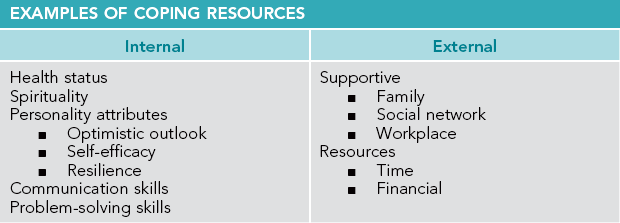

Coping

We will now examine psychological explanations regarding how people cope with excessive stress and stressors. Coping refers to the process of managing demands that challenge or exceed an individual's resources. Its purpose is to enable the person to: tolerate or adjust to stressful events or realities; retain a positive sense of self; and achieve harmonious relationships with others. It includes an evaluation of one's coping resources and the options available to determine if they are sufficient to overcome the threat. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) describe it as the cognitive and behavioural strategies that the individual uses to manage the demands perceived to challenge or exceed their resources.

Coping resources

The resources one calls on to cope may be internal (within the person), external (within the environment) or both. Internal resources refer to qualities and attributes that the individual possesses and can utilise in response to the stressor. They include the person's cognitive and behavioural responses to stress, personality attributes and disposition. External coping resources are factors external to the person, such as other people and tangible resources they can access that enable them to deal with the stressor. See Table 10.4 for examples of internal and external coping resources.

Internal coping resources: personality attributes and disposition

Personality refers to the qualities that comprise a person's cognitive, affective and behavioural makeup, and which distinguishes individuals from each other. Personality attributes and disposition are internal resources that can facilitate or hinder coping. Attitudes and disposition identified as influencing coping include: locus of control (Rotter 1966); self-efficacy (Bandura 1977); optimism and pessimism (Seligman 1994, 2011); and resilience (Garmezy 1987). Let us examine the role of personality attributes and disposition in coping.

Locus of control

Locus of control (LOC) is a construct described by the social learning theorist Julian Rotter (1966). It refers to an individual's belief regarding responsibility for reinforcement of a particular behaviour and whether the individual believes that reinforcements (outcomes) are controlled by the self, others or by chance (see also Chs 4 and 9).

People are described as possessing an internal LOC when they believe their behaviour influences outcomes, whereas a person who has an external LOC believes that forces outside the self influence outcomes, that is, chance, fate or other more powerful people. Wallston et al (1978) further refined Rotter's model to propose a ‘health LOC’ (HLOC) that comprises three attributional constructs, namely, internal, external and powerful others. For example, a person with diabetes who has one of these three attributional constructs would say:

internal – how I manage my diabetes will limit complications

internal – how I manage my diabetes will limit complications

external – no matter what I do my blood sugar levels are always unstable

external – no matter what I do my blood sugar levels are always unstable

powerful others – my doctors know more about this than me so I will leave management of my condition to them.

powerful others – my doctors know more about this than me so I will leave management of my condition to them.

Rotter proposed that a person with an internal attributional style would take more responsibility for their health; however, this only occurs when the reinforcements or outcomes are valued by the individual. For example, Rotter's theory would predict that a person with an internal LOC who valued fitness is more likely to engage in exercise than a person with an internal LOC who did not value fitness.

Furthermore, the model is not predictive of coping when the desired outcome is not exclusively under the control of the individual, for example, a person who has cancer and believes that by adhering to the prescribed treatment they will overcome the disease. While this will initially facilitate coping, should the cancer not be cured, it can have a detrimental impact on the person, who may consequently become depressed. For example, a study that examined HLOC in healthy and cancer patients found that while a high internal HLOC assisted functioning in cancer patients early in the disease, the positive affect was only evident while the patients were sufficiently well enough ‘to exert control over their health’ (Knappe & Pinquart 2009 p 201).

Self-efficacy

Bandura, too, was a social learning theorist who believed that human behaviour results from the interaction between the individual's perception and thinking and the environment. He proposed the construct of self-efficacy, which he described as a personal belief that one is capable of taking action to achieve desired or required outcomes (Bandura 1977, 2001).

According to Bandura's model the thoughts a person has about a particular event or circumstance (their self-talk) are predictive of the outcome because the person is cognitively rehearsing the eventual outcome. Self-talk can be either positive or negative. Positive talk increases the likelihood of a positive outcome because the person engages in behaviours that will bring about the desired outcome. For example, a person learning a new skill who tells themselves that ‘once I master this I will be right’ will engage in behaviours to achieve this, such as practising the skill. Alternatively, the person whose self-talk is negative, for example, ‘I will never be able to manage this’, is unlikely to practise and therefore less likely to acquire the skill.

Optimism and pessimism

Martin Seligman is a cognitive psychologist who developed the theory of learned helplessness as a cognitive behavioural explanation of depression (Seligman 1974). He later focused his attention on learned optimism, arguing that psychological research has focused excessively on illness with insufficient attention being given to wellness (Seligman 2011). Seligman is attributed as being the founder of the specialist field of positive psychology.

A person with an optimistic attribution style believes they can influence the outcomes in certain circumstances. For example, a person with diabetes who has an optimistic attribution style may make the statement, ‘Fluctuations in my blood sugar levels are a challenge to be managed’. Whereas a person with a pessimistic style who believes that the outcome has nothing to do with their actions may make the statement, ‘Even if I watch my diet my blood sugar levels are high, so I don’t bother’.

Rasmussen et al (2009), in a meta-analytic review of optimism and physical health, found that optimism was a significant indicator of physical health, although the exact mechanism of how optimism affects health and disease was not evident. Furthermore, an optimistic outlook is not necessarily the ideal approach in all circumstances and at times may be unrealistic. Segerstrom (2006), for example, found that when an optimist persists in trying to cope with a significant stressor and is unsuccessful they may experience further stress and impaired immune functioning (Segerstrom 2006).

Resilience

As discussed in Chapter 4, resilience refers to the ability to cope with and bounce back from adversity. Research in this area was initiated by Garmezy (1987), who observed that some children coped well despite their adverse family situation. Garmezy identified protective factors for these children and explored what facilitated their coping, that is, what enabled some children to be resilient despite living in a challenging family situation.

This and subsequent research has identified that being resilient involves: having caring and supportive relationships within the family and with others; being able to make realistic plans and take steps to carry them out; having a positive view of oneself and belief in one's abilities; good communication and problem-solving skills; and being able to manage strong feelings and impulses. Being resilient, though, doesn't mean that you will never feel stressed, anxious or depressed; it means that you have the requisite internal and external resources to call on in challlenging times (APA 2011).

Garmezy concluded that resilience did not influence vulnerability to stress but, rather, enabled people to cope with challenges and adversity (Garmezy 1991). That is to say that a resilient person is not less vulnerable to stress but that in a stressful situation they are likely to utilise more adaptive coping strategies than those employed by a person who is less resilient. Furthermore, resilience is not a static trait – it can be enhanced. See Box 10.2 from the APA (2011), which outlines strategies for adolescents to build resilience.

Coping strategies

Coping strategies are the actions people take in response to stress. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) separate coping strategies into two categories: emotion-focused and problem-focused. In using either or both of these coping strategies the person is active not passive and enters a process of engagement with the stressor, which they call a transaction.

Emotion-focused coping uses self-regulation in order to control one's emotional response to a stressor. Stress is moderated when the person engages in strategies that help manage their affective response to the stressor. For example, a person who seeks support from family and friends when given the diagnosis of a terminal illness is using an emotion-focused approach. Problem-focused coping addresses the stressor itself to resolve stress. If the person in the example above had researched the internet to obtain information about the treatments available for their particular illness they would have been using a problem-focused strategy. See Table 10.5 for examples of problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies.

Table 10.5

EMOTION- AND PROBLEM-FOCUSED COPING STRATEGIES

| Stressor | Emotion-focused | Problem-focused |

| Being diagnosed with diabetes | Joins a diabetes support group | Enrols in a diabetes education class |

| Made redundant at work | Takes a holiday | Registers with an employment agency |

| Having recurrent arguments with partner | Goes out with friends | Seeks relationship counselling |

| Waking up feeling ill on the day of an exam | Rolls over and goes back to sleep | Makes a GP appointment to obtain a medical certificate |

| A child who is bullied at school | Spends lunchtime in the library to avoid the bullies | Reports the bullying to a teacher |

Furthermore, at times both emotion- and problem-focused strategies can be utilised to respond to the same stressor. And while people use both problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies individuals do have a preferred style. In addition a person may use different styles in different situations such as being emotion-focused at home and problem-focused at work (Taylor 2012). Regardless, neither style is preferable – it depends on the context and the demands of the situation.

In summary, while the general intent of coping strategies is to facilitate coping this is not always the outcome. What if, for example, the person who is given the diagnosis of a terminal illness utilises the defence mechanism denial (as discussed in Ch 1)? This is an emotion-focused coping strategy that, in the short term, achieves the outcome of minimising the person's anxiety. However, denial is not an effective long-term coping strategy because it does not assist the person and their family to adjust to the reality and consequences of the illness. Furthermore, Hulbert-Williams et al's (2011) study of psychosocial predictors of cancer adjustment found that cognitions and appraisals were more predictive of the outcome than emotions. They concluded that ‘the comparative importance of cognitions in outcome prediction suggests that supportive interventions might usefully include theraputic techniques aimed at cognitive re-structuring and/or psychological acceptance of distressing thoughts and feelings’ (Hulbert-Williams et al 2011 p 11).

External coping resources

In addition to an individual's unique response to stressors, coping is also dependent on the external resources available to the person. These include, but are not limited to, social support (family and friends), education, employment and time. Socioeconomic status (SES) is a significant resource for health, with poverty and disadvantage being predictors of shorter lifespan, poorer health and reduced quality of life (Baum 2008). Conversely people of higher SES generally have more tangible external resources at their disposal to deal with stressors. See Chapter 5 for a more detailed account of the influence of social factors on health.

Social support

Social support refers to the perceived comfort, understanding and help a person receives from others. It was first described as a moderator of stress by Cobb (1976) who defined social support as the perception of being loved and cared for, of feeling esteemed and valued, and of having a social network such as family and friends who could provide resources in times of need. Support may mediate stress either by reducing the impact of stress (buffering effect) or by reducing the likelihood of adverse events (direct effect). Five types of social support that can influence health outcomes are:

emotional support – involves providing empathy and concern for the person, which provides comfort, reassurance and a sense of being loved during difficult times

emotional support – involves providing empathy and concern for the person, which provides comfort, reassurance and a sense of being loved during difficult times

esteem support – occurs when others express positive regard or encouragement for the person or validate the person's views and feelings that build feelings of self-worth and competence in the person

esteem support – occurs when others express positive regard or encouragement for the person or validate the person's views and feelings that build feelings of self-worth and competence in the person

instrumental support – refers to providing direct assistance like lending the person money or babysitting their children during stressful times, which reduces demand on the person's own resources

instrumental support – refers to providing direct assistance like lending the person money or babysitting their children during stressful times, which reduces demand on the person's own resources

information support – involves giving advice and making suggestions to assist decision making or providing feedback on action taken to affirm decisions made, which facilitates self-efficacy

information support – involves giving advice and making suggestions to assist decision making or providing feedback on action taken to affirm decisions made, which facilitates self-efficacy

network support – involves being a member of a group of people who share similar values, interests or experiences that provides the person with a sense of belonging, or assists the person to realise that they are not the only person who has experienced the particular stressor.

network support – involves being a member of a group of people who share similar values, interests or experiences that provides the person with a sense of belonging, or assists the person to realise that they are not the only person who has experienced the particular stressor.

Evidence that social support also influences health outcomes is abundant (Taylor 2012). A perception that one has adequate social support during illness can moderate the harmful effects of stress and, conversely, having inadequate social support while ill is associated with adverse outcomes. For example, Zhang et al, in a longitudinal study of 1431 elderly people with diabetes, demonstrated a relationship between perceived social support and mortality. Findings were that people who reported a low level of social support had the highest risk of death over the six years of the study. People with moderate social support had 41% less risk of death than people with the lowest reported level of social support. Furthermore, those who reported the highest levels of support were 55% less likely to have died (Zhang et al 2007).

Nevertheless, despite the reported beneficial effects of social support there are some circumstances when it is unhelpful. This can occur when: the help provided is not what the recipient perceives they require; the help is excessive, leading to depletion of the person's coping skills and overdependence on the helper; or harmful coping strategies are encouraged such as excessive alcohol use.

Coping with illness

Being diagnosed with an illness is a stressor that requires a response from the individual. How the person copes is influenced by a number of factors, including: whether the illness is acute, chronic or terminal; whether the person experiences pain, disability or loss; whether stigma is associated with the illness such as mental illness; whether treatment is available; the person's attribution style, such as internal or external LOC; and whether the person has sufficient social support and financial resources to assist coping. Importantly, coping with illness will be influenced by whether the person's quality of life (QoL) is affected. QoL refers to the person's perception of their wellbeing in their physical, functional, psychological/emotional and social/occupational domains (Fallowfield 2009).

Common emotional reactions to illness include denial, anxiety and depression (Taylor 2012). These responses produce additional stressors for the individual, particularly when the illness is chronic. The ‘self-regulation model’ for coping with chronic illness was proposed by Leventhal et al (1998) to explain how individuals cope with the stress of living with a chronic illness. Self-regulation refers to the individual proactively taking action to manage their health condition and to limit the negative effects of the illness. The stimulus to take action can be either internal, such as a person with diabetes who feels light headed so checks their blood sugar level, or external such as a person with diabetes who keeps a record of their daily blood sugar levels because they know their doctor will want to review them at the next appointment. The self-regulation model is a cognitive one that takes into account a person's view of their physical and social environments, as well as thoughts about themselves. See Chapter 9 for further discussion of chronic illness.

Conclusion

This chapter presented an overview of stress and coping. Stress was defined as the physical and psychological phenomenon experienced when a person perceives an event to threaten, challenge or exceed their available coping resources. While popular opinion views stress as a negative experience and one to be avoided, psychological research demonstrates that stress is a common experience that is a necessary part of everyday life and that stress stimulates an individual to take action in response to life's challenges and threats. Nevertheless, when stress is extreme, prolonged or the person is unable to adapt, negative health consequences can result. This also occurs when the person is overloaded with multiple stresses.

Coping was defined as the processes and strategies that a person adopts as they attempt to accommodate the actual or perceived discrepancies between stressful demands and their coping resources. When coping processes are adaptive they enable the person to respond to and manage the challenge. However, when coping resources are insufficient to manage the threat, physical and psychological illness can result. In summary, this chapter has demonstrated that the process whereby a person perceives and responds to stress is complex and influenced by a range of factors that are both internal and external to that person.

Further resources

Arranz, L., Guayerbas, N., De la Fuente, M., Impairment of several immune functions in anxious women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007;62:1–8.

Glasberg, A., Eriksson, S., Norberg, A. Burnout and ‘stress of conscience’ among healthcare personnel. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007; 57(4):392–403.

Hill Rice, V. Handbook of stress, coping and health: implications for nursing research, theory and practice, second ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2012.

Pipe, T., Bortz, J., Dueck, M., et al. Nurse leader mindfulness meditation program for stress management: a randomized control trial. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2009; 39(3):130–137.

Scully, J., Tosi, H., Banning, K. Life events checklist: revisiting the social readjustment rating scale after 30 years. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2000; 60(6):864–876.

American Psychological Association

http://www.apa.org/topics/stress/index.aspx

The APA's ‘stress’ webpage includes tips on stress management and links to publications and research.

Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health

The Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health undertakes trauma-related research, policy advice, service development and education. This website is a resource for health professionals who work with people who have experienced traumatic events.

www.helpguide.org/mental/stress_management_relief_coping.htm

The Helpguide.org website is a resource to help understand, prevent and resolve life's challenges.

This website contains resources, research and publications about positive psychology including the writings of Martin Seligman.

References

Ader, R., Cohen, N., Behaviourally conditioned immunosuppression. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1975;(37):333–340.

American Psychological Association. Six myths about stress. Online Available http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/stress-myths.aspx, 2012. [24 Sep 2012].

American Psychological Association. Resilience for teens. Online Available http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/bounce.aspx, 2011. [24 Sep 2012].

Armstrong, A., Galligan, R., Critchley, C. Emotional intelligence and psychological resilience to negative life events. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011; 51:331–336.

Arranz, L., Guayerbas, N., De la Fuente, M. Impairment of several immune functions in anxious women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007; 62:1–8.

Bandura, A. Self efficacy: towards a unifying theory of behaviour change. Psychological Review. 1977; 84:191–215.

Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001; 52:1–26.

Baum, F. The new public health, third ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Bosma, H., Marmot, M., Hemingway, H., et al. Low job control and risk of coronary heart disease in Whitehall II (prospective cohort) study. British Medical Journal. 1997; 314:558–565.

Cannon, W. The wisdom of the body. New York: Norton; 1932.

Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1976; 38:300–314.

Contrada, R., Baum, A. The handbook of stress science: biology, psychology and health. New York: Springer; 2010.

Evans, K. Anxiety disorders. In Elder R., Evans K., Nizette D., eds.: Psychiatric and mental health nursing, third ed, Sydney: Elsevier, 2012.

Fallowfield, L. What is quality of life? Health economics. Online Available http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/painres/download/whatis/WhatisQOL.pdf, 2009. [26 Sep 2009].

Garmezy, N. Stress, competence and development: continuities in the study of schizophrenic adults and the search for stress resistant children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987; 57(2):159–174.

Garmezy, N. Resiliency and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty. American Journal of Behavioral Science. 1991; 34:416–430.

Glasberg, A., Eriksson, S., Norberg, A. Burnout and ‘stress of conscience’ among healthcare personnel. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007; 57(4):392–403.

Gouin, J. Chronic stress, immune dysregulation and health. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2011; 5:476–485.

Holmes, T., Rahe, R. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967; 11:213–218.

Hulbert-Williams, N., Neal, R., Morrison, V., et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life after cancer diagnosis: what psychosocial variables best predict how patients adjust? Psycho-Oncology. 2011; 1–11.

Hurrell, J., Kelloway, E. Psychological job stress. In Rom W.N., Markowitz S.B., eds.: Environmental and occupational medicine, fourth ed, New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

Kiecolt-Glasser, J. Stress, food and inflammation: psychoneuroimmuniology and nutrition at the cutting edge. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010; 72(4):365–369.

Irwin, M. Human psychoimmunology: 20 years of discovery. Brain, Behaviour and Immunity. 2008; 22:129–139.

Kiecolt-Glasser, J. Psychoneuroimmuniology: psychology's gateway to the biomedical future. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009; 4(3):367–369.

Kanner, A., Coyne, J., Schaefer, C., et al. Comparison of two models of stress management: daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1981; 4:1–39.

Knappe, S., Pinquart, M. Tracing criteria of successful aging? Health locus of control and well-being in older patients with internal diseases. Psychology Health and Medicine. 2009; 14(2):201–212.

Lazarus, R. Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1966.

Lazarus, R., Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

Lee, J., Akhtar, S. Effects of the workplace social context and job content on nurse burnout. Human Resources Management. 2011; 50(2):227–245.

Leventhal, H., Leventhal, E., Contrada, R. Self-regulation, health and behaviour: a perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychology and Health. 1998; 13:717–733.

Marmot, M., Kogevinas, M., Elston, M. Social economic status and disease. Annual Review of Public Health. 1987; 8:111–135.

Marmot, M., Bosma, H., Hemingway, H., et al. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. The Lancet. 1997; 350:235–239.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational. Behaviour. 1981; 2:99–113.

Maslach, C. Job burnout: new directions in research and intervention. Current Directions. 2003; 12:189–192.

O'Toole, B., Catts, S. Trauma, PTSD and physical health: an epidemiological study of Australian Vietnam veterans. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2008; 64:33–40.

Pipe, T., Bortz, J., Dueck, M., et al. Nurse leader mindfulness meditation peogram for stress management: a randomized control trial. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2009; 39(3):130–137.

Rasmussen, H., Scheier, M., Greenhouse, J. Optimism and physical health: a meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioural Medicine. 2009; 37:239–256.

Rotter, J. Generalized expectancies for internal and external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and Applied. 1966; 80:1–28.

Scully, J., Tosi, H., Banning, K. Life events checklist: revisiting the social readjustment rating scale after 30 years. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2000; 60(6):864–876.

Segerstrom, S. How does optimism suppress immunity: evaluation of three affective pathways. Health Psychology. 2006; 25:653–657.

Seligman, M. Depression and learned helplessness. In: Friedman J., Katz M., eds. The psychology of depression: theory and research. Washington: Winston-Wiley, 1974.

Seligman, M. Learned optimism. Sydney: Random House; 1994.

Seligman, M. Flourish: a new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press; 2011.

Selye, H. The stress of life. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1956.

Taylor, S. Health psychology, eighth ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

Wallston, K., Wallston, B., DeVellis, R. Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health Education and Behavior. 1978; 6(1):160–170.

Witek-Janusek, L., Barkway, P. Stress and adaptation. In Brown H., Edwards D., eds.: Lewis's medical-surgical nursing, second ed, Australian ed, Sydney: Elsevier, 2004.

World Health Organization (WHO). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health; 2008.

Yerkes, R., Dodson, J., The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology 1908; 18:459–482. Online Available http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Yerkes/Law [24 Sep 2012].

Zhang, X., Norris, S., Gregg, E., et al. Social support and mortality among older persons with diabetes. Diabetes Educator. 2007; 33(2):273–281.