Health and health psychology

The material in this chapter will help you to:

understand the complex dynamics of the concept of health

understand the complex dynamics of the concept of health

understand the role of health psychology in healthcare practice

understand the role of health psychology in healthcare practice

describe the biomedical model of health and illness

describe the biomedical model of health and illness

describe the biopsychosocial model of health and illness

describe the biopsychosocial model of health and illness

explain the contribution of psychology and, in particular, health psychology to understandings of health, illness and health behaviours

explain the contribution of psychology and, in particular, health psychology to understandings of health, illness and health behaviours

analyse and critique the interrelationship between biological, psychological and social factors in health and illness behaviours and in the delivery of healthcare services.

analyse and critique the interrelationship between biological, psychological and social factors in health and illness behaviours and in the delivery of healthcare services.

Introduction

In this chapter health is presented as a dynamic concept that is constantly changing, is multidimensional and is influenced by factors that are both internal and external to the individual. The biomedical (also called bioscience) model of health and illness, which dominated healthcare delivery up until the middle of the 20th century and perpetuates the notion of a mind–body split, is examined and critiqued. Finally, it will be argued that the biopsychosocial model, which utilises research evidence, theory and clinical practices from a range of health disciplines including bioscience, psychology and sociology, offers a more comprehensive explanation for health behaviours and health outcomes than is provided by the biomedical model alone. In particular, health psychology (a branch of psychology) is examined for the contribution it makes to understandings of human behaviour in relation to health and illness and thereby to the clinical practice of not only psychologists but of all health professionals.

Psychological theories offer complementary and, at times, contradictory views of human behaviour that reflect different assumptions about the nature of individuals and how they should be studied. These varying theoretical perspectives include bioscience, psychoanalytic, behavioural (or learning), cognitive and humanistic theories. These explanations are described in detail in Chapter 1 and underpin the approaches used in health psychology. You will discover that each theoretical position offers a different perspective on human behaviour and each may provide useful explanations in specific situations. Nevertheless, none provide a universal explanation of behaviour that is applicable to all people in all situations.

What is health?

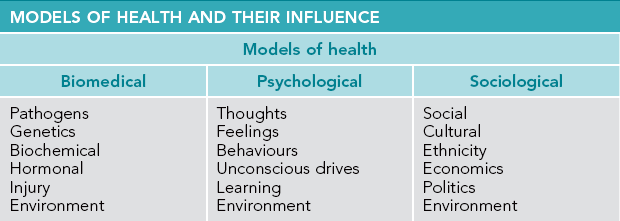

Health is a construct that can be defined in both broad and narrow terms. Narrow interpretations are provided by the biomedical model, which emphasises the presence or absence of disease, pathogens and/or symptoms. A broader interpretation is provided by the biopsychosocial approach that proposes that health is influenced by a complex interaction of biological, psychological and social factors. See Table 4.1 for sociological, psychological and biomedical factors that influence health.

Additionally, health can be examined both objectively and subjectively. Objective measures such as an x-ray or scan can indicate health or illness, while an individual's subjective interpretation will report whether he or she feels healthy or ill, but there may be no correlation between the two. For example, a person may report feeling healthy but have dangerously high blood pressure, or another person may report pain for which physical pathology cannot be identified. Therefore, given the range of criteria and the different perceptions that can influence a definition of health, it is not surprising that many interpretations exist and that debate surrounds an agreed definition of the concept (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2010, Jormfeldt et al 2007).

Furthermore, health can have different meanings for the general public or laypeople than it does for health professionals. Three consistent themes arise in research into laypeople's understanding of the concept of health. They are: health is not being ill; health is a prerequisite for life's functions; and health involves both physical and mental wellbeing (Baum 2008 p 7). Baum suggests that these lay definitions have more in common with the World Health Organization's (WHO) definition of health (more than the absence of disease) than biomedical interpretations do.

Biomedical model

Throughout history, explanations for illness have included somatic imbalance, demonology, witchcraft and environmental pathogens. In Western-industrialised countries up until the middle of the 20th century, health was generally viewed as the absence of disease, and illness was seen as a pathological state. With the emergence of the public health movement in the 19th century the biomedical approach (also called the medical model) rose to prominence and dominated Western medicine for more than 200 years. The biomedical model proposes organic, pathological theories to explain and treat illness. Essentially, this approach is an illness-based model with the underpinning assumption that illness and disease are caused by disequilibrium in the body that is brought about by one or more of the following:

biological pathogens such as viral or bacterial infection

biological pathogens such as viral or bacterial infection

trauma or injury such as acquired brain injury

trauma or injury such as acquired brain injury

a biochemical imbalance in the body such as hypothyroidism or diabetes

a biochemical imbalance in the body such as hypothyroidism or diabetes

From the 19th century, public health strategies utilising a biomedical approach such as mass vaccinations and sanitation have achieved a worldwide reduction in many communicable diseases like polio, smallpox and pneumonia, and an increase in life expectancy (Brannon & Feist 2009, Frieden 2010). In the 20th century, the discovery of antibiotics, psychotropic medications and the development of sophisticated surgical techniques such as organ transplantation have enabled previously life-threatening diseases and conditions to be treated and, in many instances, cured.

However, by the latter half of the 20th century it became apparent that the treatment era of the previous decades did not live up to the expectations of the scientific or wider community. In Western countries, for example, diseases related to lifestyle, like diabetes and cardiovascular disease, now pose a greater threat to health than that of infectious diseases. Also, with regard to the treatment of infectious diseases, some bacterial strains have developed resistance to antibiotics (e.g. methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) and for many cancers neither a cure, nor preventive vaccination has been discovered. In the main, many cancer prevention and chronic illness management strategies are related to lifestyle and the environment, such as ceasing cigarette smoking, using sun protection, being physically active, eating a healthy diet and maintaining weight within the healthy range.

In the mental illness field the unwanted side effects of antipsychotic drugs are often problematic and can contribute to non-adherence to treatment, for example, the rapid and sustained weight gain and iatrogenic diabetes mellitus experienced by some patients taking atypical antipsychotic medication to treat schizophrenia (Hasnain et al 2009, Kim et al 2010). Such consequences of treatment present a challenge to both patients and health professionals with regard to the relative cost–benefit of the treatment. For patients, the unwanted social and health consequences may interfere with adherence to the recommended treatment. For health professionals, there is the ethical dilemma of encouraging adherence to a treatment for one health condition such as schizophrenia that carries a high risk that the patient will develop another serious health condition such as diabetes mellitus.

Challenges to an exclusive biomedical approach

Initially, the biomedical model held great promise to improve the health of individuals and communities. Scientific research in the 20th century led to the discovery of medications that could cure, or eliminate, many diseases. Sulphur drugs – developed in the 1930s – and other antibiotics revolutionised the treatment of infection. In the mental health field the first antipsychotic medication (chlorpromazine) was introduced in 1950. At the time it was lauded as a breakthrough in the treatment of schizophrenia because of its ability to reduce disruptive behaviour (Meadows et al 2012). Patients who would have been in straitjackets and lived out their lives in a mental institution could now be discharged and returned to live in the community.

However, by the middle of the 20th century concerns were mounting regarding the cost escalation of scientific, technological medicine; worldwide there was recognition of the need for sustainable environments. It was also evident, particularly in Western countries, that the diseases that threatened communities were no longer infectious and acute but were chronic and related to lifestyle. For example, the health conditions that now carry the greatest burden of disease are mental illness, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, substance abuse and interpersonal violence (AIHW 2010, Marmot & Wilkinson 2006).

Challenges to the biomedical model as the exclusive framework for understanding health and to structure the delivery of healthcare services began to emerge from the middle of the 20th century, the major criticism being that an exclusive biomedical approach fails to take into account the contribution of broader psychological, sociological, political, economic and environmental factors that influence health and illness. A further criticism of an exclusive biomedical approach is that health resources are directed to costly curative services rather than to health promotion or illness prevention. Baum argues that ‘there needs to be more research on the ways in which social and economic factors affect health and what social, educational, housing and health interventions most improve health and health equity’ (Baum 2008 p 145).

Questioning of the dominance of the biomedical model by policymakers, commentators and clinicians coincided with the United Nations establishing WHO in the 1940s. WHO was given the brief to work towards ‘the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health’ and in 1946 the organisation released its then groundbreaking definition of health that stated:

Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

(WHO 1946)

This definition was developed in response to the changing healthcare needs of populations. The WHO explanation contested the efficacy of the prevailing biomedical view of health at the time by recognising the contribution of not only physical factors to health and illness but social and psychological factors as well. WHO's broadening of the definition of health signalled the introduction of what became known as the biopsychosocial approach in which the contribution of individual, lifestyle and social factors to health outcomes is acknowledged. It also laid the foundation for the emergence in the 1970s of the primary health care/new public health movement.

Nevertheless, while the WHO definition of health is a comprehensive one, it has its limitations. The use of the word ‘complete’ is problematic. Is it possible to be completely healthy in all areas identified (physical, mental and social) and at all times? And if this is not possible does it necessarily follow that an individual who has one health issue is unhealthy? Consider, for example, a person with a well-managed chronic illness (asthma) or a disability (vision impairment) who is otherwise in good health. If you asked either of these two individuals to rate their health do you think they would describe themselves as unhealthy? They probably would not. When asthma is managed by medication and vision impairment corrected by glasses the person does not experience limitations from the health issue. Therefore, in seeking a comprehensive definition of health other factors must be considered including the individual's sense of control of and satisfaction with his or her health and life.

Furthermore, there are demonstrated links between income and health outcomes, that is, that poor people have worse health outcomes regarding morbidity and mortality than people who are wealthy. This occurs both within and between countries (Babones 2008, WHO 2008). For example, in a Finnish study Tarkiainen et al (2011) found a gap in life expectancy of 5.1 years for men and 2.9 years for women between people in the lowest and highest income groups. And, while life expectancy in New Zealand is 79 years, it is only 39 years in Angola (NationMaster 2011). WHO recognises the importance of addressing income inequities to improve health and stated in the Closing the Gap report that ‘higher levels of better coordinated aid and debt relief, applied to poverty reduction through a social determinants of health framework are a matter both of life and death and of global justice’ (WHO 2008 p 130).

Increased longevity over the past two centuries, in Western countries, is attributed not only to advances in medical treatments, but also to public health initiatives and population-level interventions such as access to safe water and sanitation, programs to address global road safety, tobacco control and vaccination programs for preventable diseases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011). In fact, the biggest increase in life expectancy that occurred in the first half of the 20th century is attributed mainly to public health initiatives and population-focused interventions, not advances in medical science (Frieden 2010). Yet, in 2007–08 the Australian Government spent only 21.6% if its $100 billion health budget on public health activities for whole populations or population groups (AIHW 2010 p 442). This means that almost 80% of the government's health budget was allocated to treatment interventions and services for illness and injury, yet the evidence suggests that this is not the most effective allocation of financial resources to achieve the best health outcomes for individuals and populations (Kickbusch et al 2011, Marmot 2010).

In summary, the biomedical model holds the view that health outcomes are influenced by physiology, with health occurring when the body is in a state of equilibrium and illness being a consequence of physical pathology or disequilibrium. The approach is limited as a theory to explain and understand health and the provision of healthcare services because it is a one-dimensional model that fails to take into account the complex interplay of other factors, namely, psychological and social factors that interact with biological factors and affect health.

Biopsychosocial model

As discussed, the philosophy that underpins the biopsychosocial model is that health or illness results from a complex interplay between biological, psychological and social factors. The model emerged in the 1970s in response to realisations regarding the limitations of the biomedical model in a changing world.

The notion of an alternative to the biomedical model was first proposed by Engel (1977) and quickly gained momentum among health professionals and policymakers. The biopsychosocial model is holistic in approach and thereby avoids the mind–body split inherent in the biomedical model. A further outcome of this approach is the recognition of the contribution made by allied health professionals to healthcare and the emergence of the multidisciplinary team as a mechanism for providing health services.

Health priorities

Australia's National Health Priority Areas (AIHW 2011) are health issues identified by the federal Department of Health and Ageing for focused attention because they contribute significantly to the burden of illness and injury in Australia. The eight priority areas are: cancer control; injury prevention and control; cardiovascular health; diabetes mellitus; mental health; asthma; arthritis and musculoskeletal conditions; and obesity – all of which have complex aetiology including lifestyle, biological, psychological and social factors. In addressing these health problems the holistic nature of the biopsychosocial model offers greater opportunity to improve health outcomes than a biomedical approach alone because the biopsychosocial approach addresses more than just the symptoms of the condition.

Nevertheless, despite the intrinsic appeal of the biopsychosocial model some critics argue that, generally, social issues are not sufficiently addressed in practice (Lyons & Chamberlain 2006, Yamada & Brekke 2008). Utilising another approach – primary health care/new public health that operates from a biopsychosocial framework and has a strong emphasis on social and political issues that impact on health – is proposed as a way to overcome this shortcoming.

Primary health care/new public health

The emergence of the primary health care/new public health movement also in the 1970s coincided with the growing awareness that psychological and social influences as well as physical and biological factors influenced health outcomes for individuals and communities. It was formally endorsed as a mechanism to achieve Health for all by the year 2000 at the 1978 WHO conference in the Declaration of Alma-Ata in the former Soviet Union. The declaration was the culmination of a WHO–UNICEF sponsored conference at which representatives from 134 nations endorsed the declaration with the philosophical principles of: social justice; equity; access; empowerment; self-determination; political action; health promotion and illness prevention; collaboration between consumers, practitioners, countries, governments and those responsible for health; and striving for world peace.

Worldwide policymakers, health professionals and communities were increasingly looking beyond the biomedical model for answers to health problems (Baum 2008, Karlsson et al 2010, Marmot 2008). In 1981 Lalonde, the then Canadian Minister of National Health and Welfare, described four general determinants of health that he called human biology, environment, lifestyle and healthcare organisation. Supporting a shift from a biomedical approach to a broader approach acknowledging biopsychosocial factors Lalonde stated:

There can be no doubt that the traditional view of equating the level of health in Canada with the availability of physicians and hospitals is inadequate. Marvellous though healthcare services are in Canada in comparison with many other countries, there is little doubt that future improvements in the level of health of Canadians lie mainly in improving the environment, moderating self imposed risks and adding to our knowledge of human biology.

(Lalonde 1981 p 18)

In 1986, eight years after the Alma-Ata declaration, the first WHO International Conference on Health Promotion was held in Ottawa, Canada. Conference participants developed an action framework of five strategies (the Ottawa Charter) to achieve Health for All. These five strategies have become the cornerstone of the primary health care/new public health movement and the Charter continues to be a robust, insightful and useful document in contemporary healthcare policy and practice (Baum & Sanders 2011). Nevertheless, some commentators argue that health policy alone is insufficient to achieve health equity and social justice, and that a ‘health in all policies’ (e.g. education, welfare, housing) approach is needed to redress health inequities (Baum & Sanders 2011, Kickbusch et al 2011).

Table 4.2

ACTIONS OF THE OTTAWA CHARTER FOR HEALTH PROMOTION

| Ottawa Charter strategy | Action |

| Build healthy public policy | Direct policymakers to be aware of the health consequences of their decisions and to develop socially responsible policy |

| Create supportive environments | Generate living and working conditions that are safe, stimulating, satisfying and enjoyable |

| Strengthen community action | Empower communities and enable ownership and control of their own endeavours and destinies |

| Develop personal skills | Support personal and social development through providing information, education for health and enhancing life skills |

| Reorient health services | Share responsibility for health promotion in health services among individuals, community groups, health professionals, health service institutions and government |

Health of Australians and New Zealanders

When compared with other countries in the world, the health of Australians and New Zealanders ranks highly. They are rated among the top 10 developed countries in the world across a range of significant indicators. Life expectancy is ranked among that of the top nations in the world. See Table 4.3 for life expectancies for selected countries.

Table 4.3

LIFE EXPECTANCY IN SELECTED COUNTRIES

| Selected countries | Life expectancy at birth |

| Japan | 82.25 |

| Hong Kong | 82.14 |

| Singapore | 82.04 |

| Australia | 81.81 |

| Indigenous Australians | 70.0 |

| Korea (South) | 79.05 |

| United Kingdom | 80.05 |

| New Zealand | 79.0 |

M ori ori |

70.4 |

| United States | 78.37 |

| China | 74.68 |

| Indonesia | 71.33 |

| Papua New Guinea | 66.24 |

| India | 66.8 |

| Angola | 38.76 |

Source: AIHW 2010, NationMaster 2011, NZ Ministry of Social Development 2010

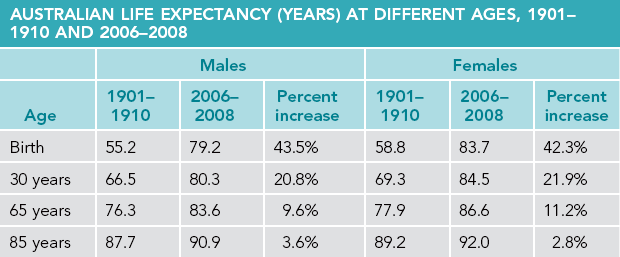

In addition, Australians born in the 21st century can expect to live 20–25 years longer than their ancestors born at the commencement of the 20th century. That is, a male born in 1901 had a life expectancy of 55.2 years, whereas a male born in 2008 has a life expectancy of 79.2 years (see Table 4.4).

Twenty-first century health challenges

Regardless of the gains made in longevity over the past one hundred years in Australia and New Zealand there are some disturbing trends in the health statistics of these two nations. Life expectancy for Indigenous Australians is 11.8 years lower than the national average. While this gap has reduced from 17.5 years in 2005–07 the AIHW cautions that the decrease is more likely to be as a consequence of a change in how the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) collects statistics rather than an actual increase in Indigenous life expectancy (AIHW 2010 p 234). Also, while the discrepancy is not as great in New Zealand as it is in Australia, M ori life expectancy is 8.6 years less than the New Zealand average (NZ Ministry of Social Development 2010). Furthermore, Indigenous Australians not only die younger than the national average, they also experience significantly more ill health and disability than other Australians (AIHW 2010 p 229).

ori life expectancy is 8.6 years less than the New Zealand average (NZ Ministry of Social Development 2010). Furthermore, Indigenous Australians not only die younger than the national average, they also experience significantly more ill health and disability than other Australians (AIHW 2010 p 229).

Also of concern is cardiovascular disease, which, in Australia, is the leading cause of death (36% of deaths) and one of the leading causes of disability (6.9% of the population). And while mortality figures for most health conditions, including coronary heart disease, stroke, colon cancer and infant mortality, have improved over the past 25 years in Australia, the mortality figures have worsened for some other illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and accidental falls (AIHW 2010 p 29). Finally, Australia has the unenviable ‘honour’ of being ranked in the ‘worst’ third of OECD countries for obesity levels, measured by a body mass index greater than 30 (AIHW 2010 p 31). That puts these Australians at increased risk for lifestyle health conditions such as high cholesterol, hypertension, heart disease and some cancers.

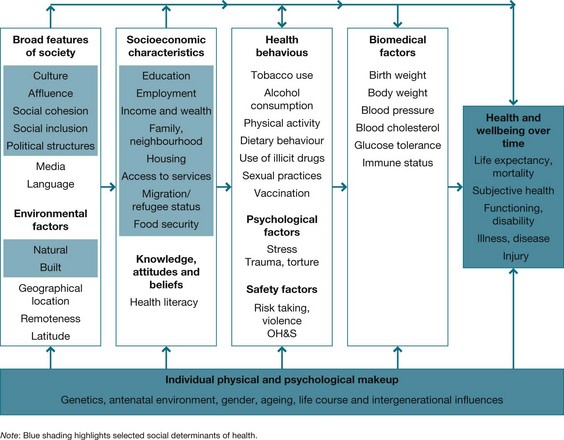

Framework for health

In conclusion, finding a universally applicable definition of health is challenging because health is a dynamic concept influenced by a complex range of factors that interact with and influence each other. Therefore, rather than pursuing an all-encompassing definition of health, a more useful approach is to utilise a framework for understanding health, such as the one developed by the AIHW (2012) (see Fig 4.1) that identifies individual, societal and environmental influences on health and the interrelationship between these factors.

What is health psychology?

Health psychology emerged as a branch of psychology in the 1970s during the emergence of the biopsychosocial model and the primary health care/new public health movement. Influential in the development of health psychology was the changing health needs of populations, mounting dissatisfaction with the biomedical model and concerns regarding the escalating costs of a medically oriented healthcare system, alongside the growing realisation of the role psychological, social and lifestyle factors play in health and illness. Additionally, chronic illnesses were replacing acute illnesses as posing the greatest burden of disease to individuals, communities and healthcare resources. The prevailing view at this time was that individuals were primarily responsible for their own health and that health outcomes were a consequence of the individual's lifestyle choices (Marks 2002 p 9).

In 1980 Matarazzo provided a definition of health psychology that stated that health psychology was an:

[a]ggregate of the specific educational, scientific and professional contributions of the discipline of psychology to the promotion and maintenance of health, the prevention and treatment of illness, the identification of etiologic and diagnostic correlates of health, illness and related dysfunction and the improvement of the healthcare system and health policy formation.

(Matarazzo 1980 p 815)

This definition specified the scope of health psychology that was to:

study the psychological aspects of how people engage in behaviours that maintain health and minimises health risks

study the psychological aspects of how people engage in behaviours that maintain health and minimises health risks

study how thoughts, feelings and personal qualities influence health behaviours and lifestyle choices

study how thoughts, feelings and personal qualities influence health behaviours and lifestyle choices

study how thoughts, feelings and personal qualities influence responses to stress, pain, loss and chronic illness

study how thoughts, feelings and personal qualities influence responses to stress, pain, loss and chronic illness

study how people recognise and respond to illness and how they decide to seek, start and complete treatment (or not)

study how people recognise and respond to illness and how they decide to seek, start and complete treatment (or not)

identify health promotion and illness prevention strategies and early intervention opportunities.

identify health promotion and illness prevention strategies and early intervention opportunities.

Contemporary critical health psychologists, however, question the moral and ethical stance of the psychological approaches to health that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s that blamed individuals for their health behaviours such as smoking or eating unhealthy food (Marks 2002 p 5). In the 21st century there is now abundant evidence that social determinants play a major role in health outcomes (Baum 2008, WHO 2008). Hence, contemporary critical health psychologists place increasing importance on the contexts in which individuals live their lives and advise that social, political and economic forces must be taken into consideration when exploring explanations of health behaviours (Brannon & Feist 2009, Marks 2002). As Murray (2012 p 38) observes, health psychology ‘is not the steady accumulation of knowledge but rather a process of inquiry and action that is socially immersed’.

In summary, health psychology seeks understanding for human health behaviours within the psychosocial, economic and political contexts in which people live in order to: identify ways of maintaining positive health behaviours; identify strategies to assist people to avoid or modify negative health behaviours; and assist people to maintain new health behaviours. This not only enables individuals to achieve, maintain or improve health but it is important for wider society in that it can improve the health of its citizens and reduce the human and resource cost of illness.

Health psychology as a career

Health psychology is a specialised branch of psychology and has two career pathways: theoretical (research) or applied (clinical practice). Research psychologists develop and test theories and evaluate interventions, while clinical psychologists work in a range of healthcare settings as members of multidisciplinary teams. Entry to both of these career pathways requires a specialist postgraduate qualification in psychology. According to the Australian Psychological Society, health psychologists:

… specialise in understanding the relationships between psychological factors (such as behaviours, attitudes, beliefs) and health and illness. Health Psychologists practise in two main areas: health promotion (prevention of illness and promotion of healthy lifestyles) and clinical health (application of psychology to illness assessment, treatment and rehabilitation).

Health psychology for health professionals

Moreover, health psychology makes a contribution to the education and practice of all health professionals. Theory and research from health psychology is a fundamental component in courses that prepare practitioners for all of the healthcare professions including, but not limited to, nursing, nutrition, medicine, occupational therapy, social work, speech pathology, paramedic practice and physiotherapy. Health professionals use knowledge and research findings from health psychology to understand the health behaviours of their patients and to plan treatment interventions, rehabilitation and recovery programs, illness prevention and health promotion programs.

Understanding health behaviours

Behaviours that promote health have long been known. For example, in 1983 Berkman and Breslow identified seven health practices that their research demonstrated could significantly reduce an individual's risk of dying at any age. They are:

sleeping seven to eight hours per day

sleeping seven to eight hours per day

being roughly appropriate weight for height

being roughly appropriate weight for height

drinking alcohol in moderation or not at all

drinking alcohol in moderation or not at all

engaging in physical activity regularly (Berkman & Breslow 1983).

engaging in physical activity regularly (Berkman & Breslow 1983).

These practices continue to be relevant in the 21st century. In 2010 the AIHW cited tobacco smoking, physical inactivity, alcohol misuse, illicit drug use, poor nutrition and unsafe sex as behavioural determinants of health, which contribute significantly to disease burden in Australia (AIHW 2010).

Influences on health behaviours

Psychological approaches to understanding health include: examinations of personality factors; perceptions and beliefs about personal control and individual; and environmental factors that reinforce behaviours. These will now be considered.

Personality

The psychological theories of personality that have particular relevance to the field of health psychology are the behavioural and cognitive models. Behavioural psychologists stress the role of learning, reinforcement and modelling in the initiation and maintenance of behaviours, while cognitivists argue that behaviours are influenced by the individual's beliefs and perceptions about themselves, events or circumstances. Additionally, personality traits and dispositions that are predictive of behaviour have been identified.

Personality types

The first description of a personality style that was purported to influence health was the type A personality type, which was described by two American cardiologists, who observed personality characteristics in their patients that they believed predisposed these patients to the risk of cardiovascular disease (Friedman & Rosenman 1959, 1974). Individuals with type A personality were considered to be competitive, impatient, time-conscious, hostile, unable to relax and had rapid, loud speech. Type B individuals were described as relaxed, quieter and less hurried than type A individuals.

While these categorisations have intuitive appeal it appears that the distinctions are not predictive of risk for coronary heart disease. For example, research conducted by Mitaishvili and Danelia examined the relationship between a range of psychological factors and coronary heart disease (CHD), and failed to find a significant relationship between CHD and personality. The researchers did find, however, that low socioeconomic status (SES) and jobs were associated with an increased risk of acute coronary events (Mitaishvili & Danelia 2006). This is similar to the finding of the landmark Whitehall study of the British civil service that found that workers in lower level positions with low job control experienced greater stress and had higher risk of CHD than higher level workers (Bosma et al 1997). See also Chapter 10.

Nevertheless, interest has been re-ignited recently in researching personality as a risk factor in the long-term prognosis of cardiac patients. With the introduction of the distressed personality type or type D, Denollet (2005) and Denollet and Pedersen (2009) described individuals who simultaneously experience high levels of negative affectivity or mood (NA) and high levels of social inhibition (SI). What this means is that when people with type D personality experience negative emotions they inhibit the expression of these emotions in social interactions. Chida and Steptoe (2009) undertook a meta-analysis review of 44 studies and concluded that anger and hostility were associated with CHD outcomes in both healthy populations and those with CHD, with the effect being greater in men than women. Denollet's research suggests it is not just the presence of negative emotions that may pose a risk factor for cardiac disease but also how that person copes with his or her negative emotions. This notion is further supported by research conducted by Williams et al (2008), as demonstrated in the following Research focus.

Resilience

Resilience is another personality trait that is linked to health outcomes. The word itself has a Latin derivation and means to spring or bounce back. In psychology resilience refers to a personality trait that is able to withstand and overcome adversity (American Psychological Association 2012).

Resilience was first described by Garmezy who, while researching risk factors for schizophrenia, observed that some children seemed to be thriving despite living in high-risk situations such as having a drug-addicted parent. Garmezy then shifted his research focus to examine what enabled such children to be successful, despite the adversity in which they lived. Subsequent research supports Garmezy's observation that resilient children are emotionally mature, that is they: possess high self-esteem and self-confidence; have the capacity to make and maintain friendships with peers; have the ability to gain the support of adults; are trusting; have a sense of purpose; possess a set of values and beliefs; and have an ‘internal locus of control’ (LOC) (Garmezy 1987).

Contemporary definitions of resilience include that it consists of individual and social components, that is, that resilience is a person's ability to adapt their emotions and to utilise social skills and resources when faced with adversity, which is mediated by culture and context (Howell 2011, Zraly 2010). Importantly, recognising the contribution of both the individual's personality traits and the role of wider society means that a person's ability to respond to negative events can be enhanced by intervening at the social level. By mobilising social resources the individual's ability to respond to and manage challenging experiences and events will be improved.

Personal control

Beliefs about who or what is responsible for behaviours differ between individuals. There are many psychological concepts that attempt to explain these differences. Two of them are LOC and self-efficacy. Both will now be examined.

Locus of control

LOC is an attribution style that was identified by Rotter in his social learning theory (Rotter 1966). It refers to the individual's belief as to whether outcomes or events in their life are brought about by themselves (internal LOC), powerful others or are random (external LOC). The model predicts that a person with an ‘internal’ explanatory style will assume responsibility for whatever happens to him/herself, crediting their own efforts when they are successful and citing insufficient effort for failure.

Wallston et al (1978) applied Rotter's LOC theory to health and developed an instrument called the multidimensional health locus of control scale (health LOC). In the health LOC model the ‘external’ explanatory style of Rotter's LOC model is expanded to describe people whose explanatory style was either that health outcomes were the result of chance or were under the control of powerful others (doctors or other people). Wallston's three dimensions of control in relation to health are: internal health LOC; chance health LOC; and powerful others health LOC (Wallston 2005, 2007). The model predicts that if a person believes that they can control their health (internal attribution) then they will behave in ways that are health-enhancing. Alternatively if a person has an external attribution style (chance or powerful other) they will be less likely to take responsibility for managing their health.

Self-efficacy

The concept of self-efficacy was first described by Bandura (1977) and refers to an individual's perceived ability to perform a certain task or achieve a specific goal in a given situation. Like health LOC, self-efficacy stresses the importance of the person's perceptions and beliefs about his or her personal control in a particular circumstance. However, self-efficacy also takes into account the expectation the person has about the consequences of action taken or not taken. For example, ‘What will happen if I take no action?’ (situation outcome expectancy); ‘What will happen if I change my behaviour?’ (action outcome expectancy); and ‘Am I capable of changing my behaviour to achieve the goal?’ (efficacy expectancy).

The theory speculates that an individual's level of confidence in his or her ability to succeed in a certain situation will influence whether the person engages in activities that will either facilitate success or failure. For example, when approaching an exam a student with a high level of self-efficacy who believes that he or she can pass the exam would engage in behaviours that lead to success such as managing their time to incorporate study, whereas a student who does not believe that they can pass the exam is likely to engage in behaviours that bring about failure such as procrastinating and avoiding preparing for the exam. Finally, while self-efficacy is considered a personality trait, it is amenable to modification through cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (Molaie et al 2010, Nash 2011).

Nevertheless, caution is advised in assuming that personality traits, resilience, internal LOC, high self-efficacy and an optimistic outlook are ideal in all circumstances. Consider the circumstance where the outcome cannot be controlled such as recurrence of cancer following a period of remission. The person who initially believed they could control their illness would have their belief seriously challenged by the recurrence and be vulnerable to depression according to Seligman's learned helplessness theory (Seligman 1994).

Social influences on health

Social influences on health are briefly identified here and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5. Demographic data demonstrate health inequities for:

SES – with lower income correlated with poorer health (Karlsson et al 2010, WHO 2008)

SES – with lower income correlated with poorer health (Karlsson et al 2010, WHO 2008)

age – the most pressing chronic health issue for young people is asthma, while it is arthritis for the elderly (AIHW 2010)

age – the most pressing chronic health issue for young people is asthma, while it is arthritis for the elderly (AIHW 2010)

gender – Australian and New Zealand women's life expectancy is almost five years greater than that of men's (AIHW 2010, Statistics New Zealand Tatauranga Aotearoa 2009)

gender – Australian and New Zealand women's life expectancy is almost five years greater than that of men's (AIHW 2010, Statistics New Zealand Tatauranga Aotearoa 2009)

ethnicity – Higgins et al found that ‘cultural and social factors … shape schizophrenia rehabilitation in China and India … including the use of traditional medicine and healers, emphasis on family involvement, stigma, gender inequality and lack of resources’ (Higgins et al 2007).

ethnicity – Higgins et al found that ‘cultural and social factors … shape schizophrenia rehabilitation in China and India … including the use of traditional medicine and healers, emphasis on family involvement, stigma, gender inequality and lack of resources’ (Higgins et al 2007).

Population groups considered at risk because of social inequities include: people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; unemployed people; Indigenous peoples; people living in rural and remote areas; prisoners; refugees; and people with mental illness (AIHW 2010). Interestingly, in Australia, migrant populations and people in the defence forces experience better health than the overall population (AIHW 2010 p xi).

Social determinants

WHO, in its publication Social determinants of health: the solid facts (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006), identified 10 key social and political factors that influence health. These different but interrelated social determinants of health are: the social gradient, stress, early life, social exclusion, work, unemployment, social support, addiction, food and transport. The authors stated that the publication of the Social determinants of health was intended to ‘ensure that policy – at all levels in government, public and private institutions, workplaces and the community – takes proper account of the wider responsibility for creating opportunities for health’ (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006 p 7).

Subsequently, WHO established the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health to examine and collate evidence on what could be done to bring about health equity and to foster a global movement to achieve it (WHO 2008). In the commission's report Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health the commissioners called on governments worldwide to reduce health inequities through policy and programs that engage key sectors of the community, such as economic development, transport and education, and to include health in all policies because health policies and programs alone cannot achieve health equity or social justice (Irwin et al 2008, Kickbusch et al 2011, WHO 2008).

Cross-cultural influences

Culture can be defined as the history, values, beliefs, language, practices, dress and customs that are shared by a group of people and that influences the behaviour of the members (Germov & Poole 2007). Commonly, culture is equated with ethnicity but this is a limited interpretation; other cultural groupings also exist based on shared understandings. For example, the phrase ‘right hander’ has different meaning for a surfer, a boxer or a schoolteacher. And, despite commonalities that define a culture, it cannot be assumed that all members of one culture necessarily share identical worldviews on any or all issues (McMurray 2010).

Different interpretations of health and explanations for illness exist between cultures that are individualistic (i.e. a society in which the smallest socioeconomic unit is the individual and independence is valued) and cultures that are collectivist (i.e. a society in which the smallest socioeconomic unit is the family and human interdependence is valued). Individualism is a cultural pattern mainly found in developed Western countries and is ‘chiefly concerned with protecting the autonomy of individuals against obligation imposed by the state, family and community’ (Kato & Sleeboom-Faulkener 2011 p 509). Individualist cultures attribute responsibility for health to the individual. Collectivist cultures, on the other hand, recognise the role of the extended family and community in all aspects of life. Members are ‘usually characterized by a sense of emotional, moral, economic, social and political commitment to their collective’ (Haj-Yahia 2011 p 333). For example, traditional M ori beliefs are that four domains influence health: family/community, physical, spiritual and emotional (Lyons & Chamberlain 2006 p 7).

ori beliefs are that four domains influence health: family/community, physical, spiritual and emotional (Lyons & Chamberlain 2006 p 7).

Moreover, it is important to recognise that, in the main, psychological theories of behaviour were developed in Western Europe and the United States, which are individualistic cultures. Consequently, caution must be exercised when applying these psychological theories derived from research conducted in individualist societies to people from collectivist societies such as Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders or New Zealand M ori, and the immigrant populations of the two countries (Lyons & Chamberlain 2006).

ori, and the immigrant populations of the two countries (Lyons & Chamberlain 2006).

Conclusion

This chapter provides an overview of the many factors that influence health and health outcomes. In particular, the contribution that health psychology makes to understanding and managing health and illness is presented. While this branch of psychology generally focuses on understanding individual behaviour and the factors that influence health outcomes, the dynamic nature of health is acknowledged, particularly the social context in which individuals live. Health psychology, therefore, is located within the biopsychosocial framework – a model that recognises the interdependence and interrelationships between biological, psychological and social factors in understanding and managing health and illness.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2012. Canberra: AIHW; 2012.

Baum, F. The new public health, third ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Lee, L., Arthur, A., Avis, M. Using self-efficacy theory to develop interventions that help older people overcome psychological barriers to physical activity: a discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008; 45(11):1690–1699.

McMurray, A. Community health and wellness: a socio-ecological approach, fourth ed. Sydney: Elsevier; 2010.

World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health; 2008.

American Psychological Association

www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx

The APA provides general information about resilience and focuses on how the individual can develop and use a personal strategy to enhance resilience.

Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet

The Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet provides knowledge and information on many aspects of Indigenous health and support, ‘yarning places’ (electronic networks) that encourage information sharing and collaboration among people working in health and related sectors.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

The AIHW is Australia's national agency for health and welfare statistics and information.

New Zealand Health Information Service/Te Paronga Hauora

The New Zealand Health Information Service/Te Paronga Hauora contains health statistics and publications relevant to the health of New Zealanders.

The Social Report/Te Purongo Oranga Tangata

www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz/health

The Social Report/Te Purongo Oranga Tangata 2008 provides an overview of the current state of New Zealand's health and the likely trends in the future.

Hans Rosling's 200 countries, 200 years

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jbkSRLYSojo

This engaging presentation by Swedish Professor of Global Health Hans Rosling uses statistics to demonstrate the relationship between income, health and life expectancy changes throughout the world over the past 200 years.

References

American Psychological Association. The road to resilience. Online Available http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx, 2012. [12 Sep 2012].

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australia's health 2010. Canberra: AIHW; 2010.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Health Priority Areas. Online Available http://www.aihw.gov.au/health-priority-areas, 2011. [12 Sep 2012].

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Australia's health 2012: Australia's Health No. 12, AIHW cat. No. AUS122. AIHW, Canberra, 2012. Online Available www.aihw.gov.au [12 Sep 2012].

Australian Psychological Society. Specialist areas of Psychology. Online Available http://www.psychology.org.au/community/specialist, 2012. [12 Sep 2012].

Babones, S.J. Income inequality and population health: Correlation and causality. Social Science and Medicine. 2008; 66:1614–1626.

Bandura, A. Self efficacy: towards a unifying theory of behaviour change. Psychological Review. 1977; 84:191–215.

Baum, F. The new public health, third ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Baum, F., Sanders. Ottawa 25 years on: a more radical agenda for health equity is still required. Health Promotion International. 2011; 27(Supp 2):253–257.

Berkman, L., Breslow, L. Health and ways of living: the Alameda County study. New York: Oxford University Press; 1983.

Bosma, H., Marmot, M., Hemingway, H., et al. Low job control and risk of coronary heart disease in Whitehall II (prospective cohort) study. British Medical Journal. 1997; 314:558–565.

Brannon, L., Feist, J. Health psychology: an introduction to behaviour and health, seventh ed. Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2009.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ten great public health achievements worldwide: 2001–2010 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 24 June. Online Available http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6024a4.htm, 2011. [12 Sep 2012].

Chida, Y., Steptoe, A. The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review of prospective evidence. Journal of American College of Cardiology. 2009; 53(11):936–946.

Denollet, J., Pedersen, S. Anger, depression and anxiety in cardiac patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009; 53(11):947–949.

Denollet, J. DS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition and type D personality. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005; 67:89–97.

Engel, G. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for bio-medicine. Science. 1977; 196:129–135.

Frieden, T. A framework for public health: the health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health. 2010; 100(4):590–595.

Friedman, M., Rosenman, R. Association of specific overt behavior pattern with blood and cardiovascular findings; blood cholesterol level, blood clotting time, incidence of arcus senilis, and clinical coronary artery disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1959; 169(12):1286–1296.

Friedman, M., Rosenman, R. Type A behavior and your heart. New York: Knopf; 1974.

Garmezy, N. Stress, competence and development: continuities in the study of schizophrenic adults, children vulnerable to psychopathology and the search for stress-resistant children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987; 57(2):159–174.

Germov, J., Poole, M. Public sociology: an introduction to Australian society. Sydney: Allen & Unwin; 2007.

Haj-Yahia, M. Contextualising interventions with battered women in collectivist societies: issues and controversies. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011; 16:331–339.

Hasnain, M., Vieweg, W., Frederickson, S., et al. Clinical monitoring and management of the metabolic syndrome in patients receiving atypical antipsychotic medications. Primary Care Diabetes. 2009; 3:5–15.

Higgins, L., Dey-Ghatak, P., Davey, G. Mental health nurses’ experiences of schizophrenia rehabilitation in China and India. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2007; 16(1):22–27.

Howell, K.H. Resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to family violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011; 16:562–569.

Irwin, A., Solar, O., Vega, J. The United Nations Commission of Social Determinants of Health. In: International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Elsevier; 2008:64–69.

Jormfeldt, H., Svedberg, P., Fridlund, B., et al. Perceptions of the concept of health among nurses working in mental health services. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2007; 16(1):50–56.

Karlsson, M., Nilsson, T., Lyttkens, C., et al. Income inequality and health: importance of a cross-country perspective. Social Science and Medicine. 2010; 70:875–885.

Kato, M., Sleeboom-Faulkener, M. Dichotomies of collectivism and individualism in bioethics: selective abortion debates and issues of self-determinism in Japan and ‘the West. Social Science & Medicine. 2011; 73:507–514.

Kickbusch, I., Hein, W., Silberschmidt, G. Addressing global health governance challenges through a new mechanism: the proposal for a Committee C of the World Health Assembly. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2011; Fall:550–563.

Kim, S., Nikolics, L., Abbasi, F., et al. Relationship between body mass index and insulin resistance in patients treated with second generation antipsychotic agents. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010; 44:493–498.

Lalonde, M. A new perspective on the health of Canadians: a working document. Ottawa: Ministry of National Health and Welfare; 1981.

Lee, L., Arthur, A., Avis, M. Using self-efficacy theory to develop interventions that help older people overcome psychological barriers to physical activity: a discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008; 45(11):1690–1699.

Lyons, A., Chamberlain, K. Health psychology: a critical introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

McMurray, A. Community health and wellness: a socio-ecological approach, fourth ed. Sydney: Elsevier; 2010.

Marks, D. Freedom, responsibility and power: contrasting approaches to health psychology. Journal of Health Psychology. 2002; 7(1):5–19.

Marmot, M. Fair society, healthy lives: strategic review of health inequalities in England post 2010. London: The Marmot Review; 2010.

Marmot, M. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet. 2008; 327(8):1661–1669.

Marmot, M., Wilkinson, R. Social determinants of health: the solid facts, third ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

Matarazzo, J. Behavioral health and behavioral medicine: frontiers for a new health psychology. American Psychologist. 1980; 35:807–817.

Meadows, G., Farhall, J., Fossey, E., et al. Mental health in Australia: collaborative commnity practice, third ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Mitaishvili, N., Danelia, M. Personality type and coronary heart disease. Georgian Medical News. 2006; 134:58–60.

Molaie, A., Shahidi, S., Vazifeh, S., et al. Comparing the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy and movie therapy on improving abstinence self-efficacy in Iranian substance dependent adolescents. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2010; 5:1180–1184.

Murray, M., Social history of health psychology: contexts and textbooks. Health Psychology Review 2012;. Online Available http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17437199.2012.701058 [26 Sep 2012].

Nash, V. Cognitive behavioral therapy, self-efficacy and depression in persons with chronic pain. Pain Management Nursing. 2011; 12(2):e6.

NationMaster.com Health statistics: Life expectancy at birth. Online. Available: http://www.nationmaster.com/graph/hea_lif_exp_at_bir_tot_pop-life-expectancy-birth-total-population 12 Sep 2012

New Zealand Ministry of Social Development. The social report – te pūrongo oranga tangata 2010. Auckland: New Zealand Ministry of Social Development; 2010.

Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs. 1966; 80:234–240.

Seligman, M. Learned optimism. Sydney: Random House; 1994.

Statistics New Zealand Tatauranga Aotearoa. New Zealand life tables 2005–2007. Online Available http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/health/life_expectancy.aspx, 2009. [12 Sep 2012].

Tarkiainen, L., Martikainen, P., Laaksonen, M., et al, Trends in life expectancy by income from 1988 to 2007: decomposition by age and cause of death. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2011;. Online Available http://jech.bmj.com/content/early/2011/03/04/jech.2010.123182.short [12 Sep 2012].

Wallston, K., Wallston, B., DeVellis, R. Development of multidimensional health locus of control (MHLOC) scales. Health Education Monographs. 1978; 6:160–170.

Wallston, K. The validity of the multidimensional health locus of control scales. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005; 10(5):623–631.

Wallston, K. Multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Online Available http://www.vanderbilt.edu/nursing/kwallston/mhlcscales.htm, 2007. [26 Sep 2012].

Williams, L., O'Connor, R., Howard, S., et al. Type D personality mechanisms of effect: the role of health-related behavior and social support. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2008; 64(1):63–69.

World Health Organization (WHO), Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. WHO, Geneva, 2008. Online Available http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.html [12 Sep 2012].

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO constitution. New York: WHO; 1946.

Yamada, A., Brekke, J. Addressing mental health disparities through clinical competence not just cultural competence: the need for assessment of sociocultural issues in the delivery of evidence-based psychosocial rehabilitation services. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008; 28:1386–1399.

Zraly, M. Don't let the suffering make you fade away: an ethnographic study of resilience among survivors of genocide-rape in southern Rwanda. Social Science & Medicine. 2010; 70:1656–1664.