Behaviour change

The material in this chapter will help you to:

describe and understand the dominant psychological approaches that aim to explain health behaviours, namely

describe and understand the dominant psychological approaches that aim to explain health behaviours, namely

» the theory of planned behaviour

» the transtheoretical model of behaviour change

» the health action process approach

utilise the above theories and models to explain the initiation and the continuation of health-enhancing and health ‘risk’ behaviours

utilise the above theories and models to explain the initiation and the continuation of health-enhancing and health ‘risk’ behaviours

utilise the above theories and models to modify health behaviours

utilise the above theories and models to modify health behaviours

identify the limitations of psychological theories and models as predictors and moderators of health behaviours.

identify the limitations of psychological theories and models as predictors and moderators of health behaviours.

Introduction

How healthy is your lifestyle? Do you regularly follow the health practices identified in Chapter 4 regarding nutrition, physical activity, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption? Have you ever made a decision regarding one of these health behaviours but not continued with the activity as you intended, for example, to exercise regularly? Or perhaps you did follow through with your intention and maintained the activity. Why might there be different outcomes to these scenarios when your intention was the same in both? What other factors might influence the outcomes in these two scenarios?

Such questions underpin psychological health research and contribute to the development of theories and models that can explain and predict an individual's health-related behaviours. Additionally, psychological theories propose models of behaviour change and identify interventions that can change unhealthy behaviours. This chapter will examine a range of psychological approaches that propose explanations as to how internal (within the person) and external (within the environment) factors influence an individual's health behaviours and lifestyle.

Health-enhancing behaviours: what are they?

Health behaviours are actions that enhance, maintain or threaten an individual's health. They are activities that an individual practices or abstains from in order to maintain health or to reduce the risk of illness or accident. Health behaviours can be either positive or negative and include such practices as: following a healthy diet and eating in moderation; not driving a car while under the influence of alcohol or drugs; keeping immunisations up to date; and regular health screening such as for dental health and breast or prostate cancer. When practised regularly (such as daily teeth brushing) a health behaviour is called a health habit, while clusters of health behaviours are referred to as lifestyle.

Health-enhancing behaviours: why focus on them?

Up until the mid-20th century global public health threats were mainly from infectious and communicable diseases. However, in developed countries, a shift occurred over the past one hundred years whereby the major health threats are now posed by diseases in which lifestyle plays a role in the aetiology and/or management of illness (Frieden 2010). For example, the modifiable risk factors for coronary heart disease, a leading cause of disease burden, are tobacco smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol level, insufficient physical activity, overweight/obesity, poor nutrition and diabetes (AIHW 2010), all of which are linked to health behaviours and lifestyle.

Disease burden is measured by disability adjusted life years (DALYs), which comprises years of life lost (YLLs) (mortality) and years lived with disability (YLDs) (morbidity). In Australia, New Zealand and other Western nations the health conditions with the greatest disease burden (measured by DALYs and YLDs) are cancers, cardiovascular diseases, mental illness, injuries, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes (AIHW 2010). Each of these conditions, at least in part, can be attributed to lifestyle and the course of the conditions can be moderated by health behavioural practices. Hence, there is intuitive appeal in encouraging people to lead a healthy lifestyle to thereby reduce their disease risk and to improve quality of life for people with chronic health conditions. There is also abundant research evidence about the relationship between health behaviours and health from research evidence to support lifestyle interventions (Chiu et al 2011, Cox et al 2008, Harvey et al 2008).

From the individual's perspective the reasons to change health behaviours include prevention (to avoid the risk of a health problem), management (treatment of an identified health problem) recovery (living well with an ongoing health problem) and for general wellbeing. From the health professionals' and health services' perspectives additional motives include reducing the incidence and burden of the health issue in the community and the best utilisation of resources.

Health psychology: theories and models

Health psychology is interested in factors that influence the initiation, continuation, cessation and modification of behaviours that impact on health and health outcomes. To this end psychological theories propose hypotheses to explain and predict behaviour, while models (which are derived from theories) detail the processes and stages of how the behaviour under observation is enacted. In addition to observable behaviours the health beliefs held by individuals and the impact these beliefs have on their health-related behaviours are investigated. Finally, health psychology is interested in finding effective strategies to help people to overcome resistance to change their behaviour and prevent relapse.

Psychological theories and models of health behaviour attempt to explain or predict an individual's engagement in behaviours that influence the risk for illness or injury and the maintenance of health. Psychological theories of health behaviour fall into two broad categories: behavioural/learning theories and cognitive theories. Behavioural/learning approaches include operant conditioning, classical conditioning and modelling or imitation (see below and Ch 1). Cognitive approaches include the health belief model, the transtheoretical model of behaviour change and motivational interviewing. The theory of planned behaviour introduces social influences to a cognitive model as does the health action process approach. These behavioural and cognitive approaches to behaviour change will now be examined.

Learning theories

Learning (also called behavioural) theories propose that personality is determined by prior learning, that human behaviour is changeable throughout the lifespan and that changes in behaviour are generally caused by changes in the environment. They are concerned only with behaviour that is observable, and not mental or affective processes. Specifically, learning theories focus on the conditions that produce behaviour, factors that reinforce behaviour and vicarious learning through watching and imitating the behaviour of others. The three main learning approaches are:

classical conditioning – learning by association

classical conditioning – learning by association

operant conditioning – learning by reinforcement

operant conditioning – learning by reinforcement

social learning theory – vicarious learning (modelling/observation and copying).

social learning theory – vicarious learning (modelling/observation and copying).

Classical conditioning

As outlined in Chapter 1, classical conditioning was first described by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov who observed the relationship between stimulus and response through demonstrating that a dog could be conditioned to salivate (respond) to a non-food stimulus (a bell) (Pavlov 1927). For example, a patient may be receiving intravenous chemotherapy for cancer, which has the side effect of nausea. Over time the patient may experience nausea when the chemotherapy nurse enters the room, and before the injection is given. The feeling of nausea when the nurse is present has been learned through classical conditioning.

Operant conditioning

B F Skinner formulated the notion of instrumental or operant conditioning in which reinforcers (rewards) contribute to the probability of a response being either repeated or extinguished. Skinner's research demonstrated that the contingencies on which behaviour is based are external to the person, rather than internal. Consequently, changing contingencies could alter an individual's behaviour (Skinner 1953). For example, if a child throws a tantrum when told it is bedtime, and the parent relents and allows the child to stay up later, the child learns that they can get what they want by throwing a tantrum. To reverse this behaviour the parent would need to ignore the child's tantrum and firmly insist that it is bedtime.

Observational learning theory

Observational learning theory (also called modelling or social learning theory) was proposed by Bandura (1969, 2006) who asserts that observational learning has a more significant influence on how humans learn than intrapsychic (psychoanalytic) or environmental (behavioural/learning) forces alone. Bandura proposed that human behaviour results from the interaction between the environment and the person's thinking and perceptions. He also asserted that humans can learn from observing – not just by doing. Observational learning differs from operant conditioning in that it is not the learner who is rewarded for the behaviour; rather, the learner observes the other person being rewarded and learns vicariously through this. New behaviours are acquired by observing others being rewarded for performing a behaviour, and then imitating that behaviour.

Observational learning is particularly important for children's learning because it is easier to influence a behaviour while it is being acquired rather than changing an established behaviour. Hence parents, family and schooling play a significant role in the health habits that children acquire. These habits can be both positive health behaviours, such as participating in sport and cleaning their teeth, or negative practices such as tobacco smoking. For example, in a 12-month study of 1237 seventh and eighth grade students in Germany, Krahé and Möller (2010) found that watching violent media was predictive of aggressive behaviour.

Learning theory approaches

Have you ever received a parking fine, a speeding ticket, lost your driver's licence, been locked out of a concert until interval because you arrived late or been refused borrowing rights at your library until you paid your fine for late returns? Do you feel motivated after your boss tells you that he is impressed with your work or smile back at someone who has just smiled at you? Most of us, without realising it and without being able to use the technical terminology of behavioural change programs, actually practise behaviour modification in our everyday lives and have it practised on us. In your various roles as citizens, partners, parents, friends and health professionals, you will, by the end of this chapter, be surprised to discover how much of your own behaviour is governed by the fundamental principles of learning theory, on which behavioural change programs are based, and how much of the behaviour of those around you is at least partly determined by your own behavioural change strategies.

Behavioural change programs

Behavioural change programs aim to change behaviour, not attitudes, beliefs, motivation, personality or other unobserved characteristics of individuals. Behaviour may be defined as anything that a person does or says; that is, behaviour is any action or response to an environmental event that is observable and measurable. Behaviours can be overt (readily observed and counted) or covert (not readily observed but can still be counted and changed, such as thoughts and feelings using the principles described in this chapter). Regardless of the orientation of specific programs, all behavioural change programs operate on the following four tenets:

Behaviour can be explained by the principles of learning and conditioning.

Behaviour can be explained by the principles of learning and conditioning.

The same laws of learning apply to all behaviour, both normal and abnormal.

The same laws of learning apply to all behaviour, both normal and abnormal.

Abnormal behaviour is the normal response to abnormal learning conditions.

Abnormal behaviour is the normal response to abnormal learning conditions.

These four tenets underpin the four major theoretical models that have been derived from learning theory, namely, classical conditioning, operant conditioning, observational (imitation) learning and cognitive behaviourism (Beck 1976, Ellis 1984, Meichenbaum 1974).

Historically, behaviour therapy referred to the techniques based on classical conditioning, devised by Wolpe (1958) and Eysenck (1960) to treat anxiety; behaviour modification was used to describe programs based on the principles of operant conditioning devised by Skinner (1953) to create new behaviours in children who had an intellectual disability and patients experiencing psychotic symptoms.

In current practice, the terms behaviour therapy, behavioural change programs and behaviour modification are used interchangeably to describe therapeutic programs based on the principles of behavioural/learning theory. The term ‘behavioural change program’ will be used in this chapter. The following outlines the principles a clinical psychologist would use when designing a behavioural program.

Functional analysis of behaviour

The principles of operant conditioning (learning by reinforcement) describe the relationship between behaviour and environmental events, both antecedents and consequences that influence behaviour. This relationship, referred to as a contingency, consists of three components:

antecedents (i.e. stimulus events that precede or trigger the target behaviour)

antecedents (i.e. stimulus events that precede or trigger the target behaviour)

behaviours (i.e. responses, usually the identified problem behaviour)

behaviours (i.e. responses, usually the identified problem behaviour)

consequences (outcomes of the behaviour, i.e. what actually happened immediately after the problem behaviour occurred).

consequences (outcomes of the behaviour, i.e. what actually happened immediately after the problem behaviour occurred).

Specifying these contingencies forms the basis of a functional analysis of behaviour. The aim of a functional analysis is to identify factors that influence the occurrence and maintenance of a particular (problem or desired) response. This process should not be confused with other explanatory models that may seek to explain behaviour in terms of a medical diagnosis or a personality trait. Behavioural change programs are more concerned with the nature of our interactions with the environment than with our nature per se.

Conducting a functional analysis of behaviour is the first step in designing a behavioural change program. It consists of the three components outlined below.

1 Selecting the target behaviour

The target behaviour must be specified in such a way that it can be readily observed and measured. The behaviour of interest may be a behavioural excess (e.g. tantrums, exceeding the speed limit, driving while intoxicated) or a behavioural deficit (e.g. an eight-year-old who cannot tie his shoelaces, an adult who does not complete recommended physiotherapy exercises, a well elderly person who does not perform self-care activities). From the examples given, it will be clear that behavioural deficits are of two types: behaviours that exist in the behavioural repertoire of the individual but which the individual does not perform, and behaviours that are not in the behavioural repertoire of the individual and must be developed. It is important to distinguish among these different groups of target behaviours as each requires the application of different behavioural change strategies.

Behaviour must never be viewed in isolation. The behavioural change agent considers the setting in which the behaviour occurs, the nature of the task and the characteristics of the client. Behaviour may be appropriately performed in one setting and not another. For example, it would be appropriate for a three-year-old child who has just learned to take his clothes off to do so in the bathroom in his home, but not in a busy shopping centre. A behavioural change program in this instance would aim to teach the child the appropriate setting for performing this newly acquired behaviour. Behaviour may also be considered problematic due to its rate, duration or intensity rather than the behaviour itself. For example, taking a shower is a common behaviour that may become problematic if the person spends one hour doing so or showers multiple times through the day. In this case, the behavioural change program would aim to reduce the amount of time spent in the shower or the frequency of showers.

2 Identifying current contingencies

This process involves two steps. The first is identifying the stimulus event(s) (i.e. antecedents) that precede(s) an occurrence of the problem behaviour. This includes an assessment of the physical (where the behaviour occurs) and social (who is present) environment in which the behaviour occurs. Certain behaviours will frequently occur at a high rate in one setting and be absent or occur at a low rate in others. For example, parents may complain about their child throwing tantrums and being argumentative at home to the child's teacher, who reports that the child is compliant and polite in the classroom. Alternatively, the teacher may notice that the child stays on task in some subjects and not in others or during the morning session but not during the afternoon. In the hospital setting, two nurses may discover that a particular patient rings the buzzer for nursing assistance twice as often for one nurse compared with another, or that a child with cerebral palsy is more likely to persist with his physiotherapy exercises when his mother is not in the treatment room. These observations provide important information about the stimulus events that may be controlling the target behaviour.

The second step requires identifying the consequences that follow the problem behaviour; that is, what happened after the behaviour was performed? To follow through with our examples above, did the parents respond to the child's tantrum by giving the child what she wanted or did they ignore her tantruming behaviour? Did they engage in a verbal debate with the child when she talked back or did they calmly state their rule that talk backs would not be answered? In an aged care setting two nurses notice that an elderly resident rings the buzzer twice as often for one nurse compared with another—were there any differences in each of the two nurses' responses to the buzzer ringing? A child does not cooperate with physiotherapy exercises when his mother is in the room—what was the mother doing in the treatment room during her child's physiotherapy sessions? Answers to these questions are essential for effective behavioural management to occur.

3 Measuring and recording behaviour

There are five basic methods of measuring behaviour in healthcare settings:

Once you have specified the target behaviour and identified the setting in which this behaviour occurs, it is necessary to obtain a baseline of the frequency or length of its occurrence. The way you measure frequency or length depends on the nature of the target behaviour and what you wish to find out about the behaviour.

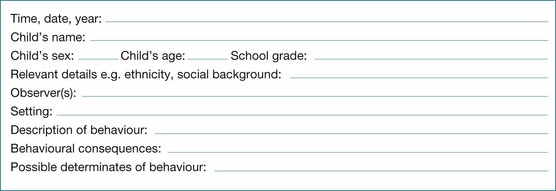

Narrative recording

Narrative recording involves the observation and recording of behaviour in progress. It is often used in the early stages of the functional analysis of behaviour as a way of identifying possible antecedents and consequences of a given problem behaviour. Figure 7.1 provides an example of a narrative recording chart, for example, for a child with type 1 diabetes mellitus who refuses to take and record their blood sugar levels while at school.

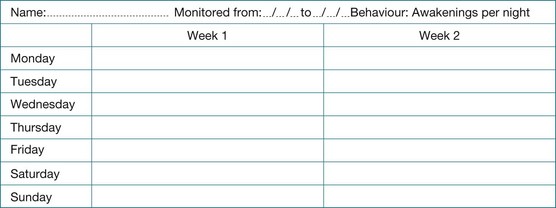

Counting

Counting is the method of choice if the target behaviour is discrete (i.e. an observer can identify the beginning and end of each instance of behaviour). Behaviours such as head banging, exercising and incontinence are examples of discrete, countable behaviours. Simple tally sheets or frequency counters can be used to record countable behaviours. One can also count the number of tasks completed or the percentage of items correct. These are examples of counts of the product or outcome of behaviour. They do not require continuous observation of the behaviour per se. Figure 7.2 provides an example of a recording chart for counting responses. In this case, the number of times the person awoke in the night is recorded.

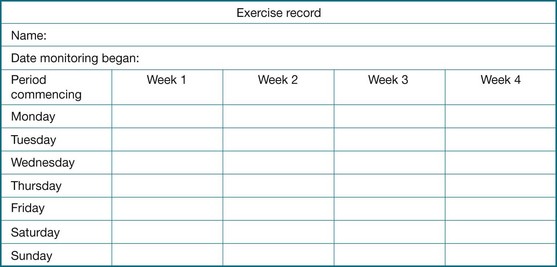

Timing (duration)

When a behaviour becomes a problem because of the length of time it takes to complete the task, or when you are interested in increasing the duration of a particular behaviour, you may choose to collect temporal data. Examples of behaviours for which temporal data are appropriate are length of time it takes for a doctor to perform a given task such as a surgical procedure, the length of time it takes for a hospitalised patient to shower in the morning or the amount of time a person spends in the gym practising physiotherapy exercises. Figure 7.3 provides an example of a chart for timing the duration of a target behaviour, in this case performing rehabilitation exercises in the gym over a four-week period.

Checking

Checking or interval recording is used when you want to know whether an individual performs a specified task or not. In such cases your code requires a simple yes–no response. By checking on groups of related behaviours, you can quickly build up a picture of the individual's current level of functioning. For example, you may wish to increase the self-care behaviours of a patient with advanced dementia. When he arrives at breakfast each morning, you can check whether he has combed his hair, shaved, dressed in day clothes (as opposed to pyjamas) and is wearing shoes. After you obtain a baseline following several days of checking, you will be ready to design a behavioural change program to address any outstanding deficits in self-care. Figure 7.4 is an example of a checklist, for example, for assessing how well a person with dementia manages their personal hygiene and grooming.

Rating

Rating is a method of assessing the quality of a response and, as such, requires a subjective judgment on the part of the observer. You may wish to assess the intelligibility of the speech of a person who is dysarthric. One quick measure of intelligibility is to ask the nursing staff and family members to rate the person on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = very difficult to understand to 5 = very easy to understand.

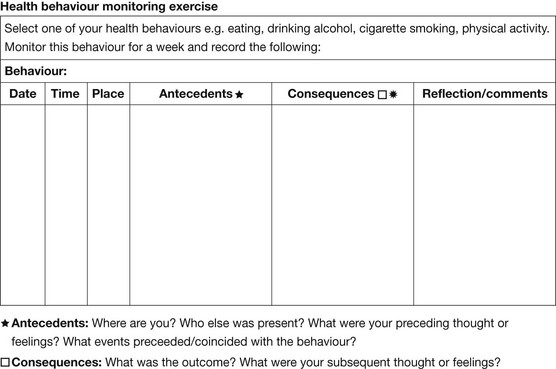

In summary, a functional analysis of behaviour can identify the antecedents (what triggers the behaviour) and the consequences (outcomes of the behaviour). Consider one of your own health behaviours from a behavioural/learning perspective and monitor this for one week using the ‘Health behaviour monitoring exercise’ in Figure 7.5, then complete the Classroom activity.

Cognitive theories of health behaviour

Cognitive psychological theories propose that people actively interpret their environment and cognitively construct their world. Therefore, behaviour (including health-related behaviour) is a result of two factors, namely:

internal (within the person) events, which are the individual's thoughts and perceptions about themself, the world and their behaviour in the world

internal (within the person) events, which are the individual's thoughts and perceptions about themself, the world and their behaviour in the world

external (within the environment) events, which are the stimuli and reinforcements that regulate behaviour.

external (within the environment) events, which are the stimuli and reinforcements that regulate behaviour.

While cognitive psychology emerged as a field of study and therapy in the 1970s the notion that one's thinking influences one's behaviour is not new. Epictetus, the Greek Stoic philosopher, is attributed to making the statement that ‘we are disturbed not by the things but by the view we take of them’ and Buddha observed that ‘we are what we think’ (Wood 2012 p 172). Consider the following scenario that exemplifies how different outcomes can result from different thoughts about the same situation or event.

Health belief model

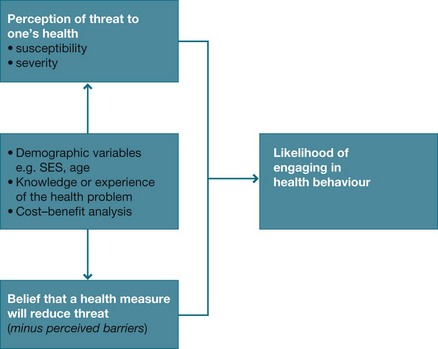

The health belief model (HBM) (Fig 7.6) was the first cognitive explanatory model in health psychology and continues to be used today. It was developed in the 1950s by Hockbaum and Rosenstock to explain the unexpected low levels of participation in health screening and illness prevention programs (Rosenstock 1966, 1974, 1991).

Since the 1970s the HBM has been widely utilised in health education and health promotion programs. This cognitive model predicts the seeking of treatment or the changing of health behaviours on the basis of two factors:

the individual's perception of threat to his/her health, including susceptibility and severity

the individual's perception of threat to his/her health, including susceptibility and severity

the degree to which the individual believes that a particular health action or behaviour will influence the health outcome and be effective in reducing the threat. It includes an assessment of the perceived benefits of the behaviours and the perceived barriers to carrying out the new behaviour.

the degree to which the individual believes that a particular health action or behaviour will influence the health outcome and be effective in reducing the threat. It includes an assessment of the perceived benefits of the behaviours and the perceived barriers to carrying out the new behaviour.

When the model was devised it was assumed that increased knowledge through health education programs would lead to greater participation in public health programs. However, the expected outcome of changed health behaviours following exposure to health education did not always eventuate. For example, in a study of sexual risk taking among American college students (n = 71), Downing-Matibag and Geisinger (2009) found that situational characteristics such as ‘spontaneity’ interfered with students being able to engage in ‘safe sex’ despite the student being aware of the possibility of acquiring a sexually transmitted infection.

Initially health education strategies utilising the HBM do increase the individual's motivation to engage in health-enhancing behaviours, but this does not necessarily translate into action. The knowledge that a particular behaviour is beneficial or harmful to one's health is insufficient, on its own, to change many people's health practices or behaviour. This is because the HBM identifies what to change but not necessarily how to make the required changes, nor does the HBM teach the skills required to make and sustain the change.

Consider the current concern being expressed about rising obesity rates in Western nations. The majority of obese people know that being overweight poses health risks and understand that to lose weight they need to eat a healthy diet and be physically active – that is, to balance kilojoule intake and expenditure. Yet obesity levels continue to rise. Therefore, while the HBM is useful in predicting some health behaviours, such as regular breast screening by a woman with a family history of breast cancer, the model is not universally applicable for all people or all health issues.

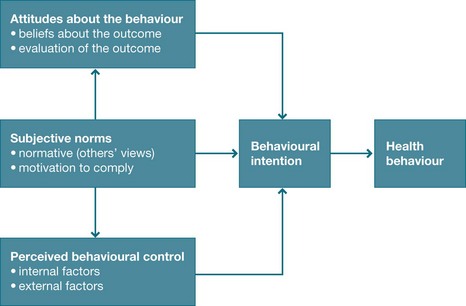

Theory of planned behaviour

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) was first proposed by Ajzen and Maddern (1986) to seek understandings of behaviours that behavioural and cognitive theories had failed to explain, particularly the non-uptake of healthy behaviours. The TPB is based on the premise that using cognitive and behavioural models alone is insufficient to understand health behaviours or to produce change. It proposes that social processes must also be taken into account. It, therefore, introduces ‘social cognitions’ to the previously developed cognitive models like the HBM.

The TPB (see Fig 7.7) proposes that three beliefs are predictive of the individual's health behaviour or behavioural outcomes. These are:

Overall, the TPB is a better predictor of health behaviour change than previous cognitive models because it takes account of the individual's belief in their capability to achieve the desired outcome (self-efficacy) and the social context in which the behaviour occurs. For example, in a high school where binge drinking is an accepted ‘norm’ it can be predicted that many adolescents will engage in this behaviour, despite being aware that this practice is harmful. This is because an individual may not have the confidence to be different and is motivated to comply with the subjective norm. Furthermore, research suggests that it is not just intention that leads to performing a certain behaviour but that environmental factors also play a role. Norman's (2011) study of binge drinking among undergraduate students found that while binge drinking was influenced by the student's intention to drink, contextual cues such as how much others were drinking also influenced whether they engaged in binge drinking or not. The researcher concluded that in addressing binge drinking as a health issue it is important to focus on both the motivational intentions of the individual as well as environmental factors.

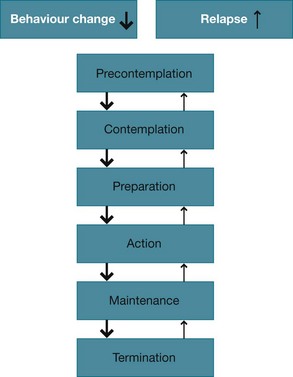

Transtheoretical model of behavioural change

The transtheoretical model of behaviour change (TTM) utilises both behavioural and cognitive strategies. The model was developed by Prochaska and DiClemente (1984) from their research in addiction studies. It was further refined by Prochaska et al (1992) and Prochaska (2006).

TTM proposes that lasting behaviour change can be achieved using this cognitively based therapy to assist people to move towards the maintenance stage of a positive health behaviour such as gambling cessation. While the authors present the stages in a sequential manner they stress that movement through the stages is not linear. An individual will move backwards and forwards through and between the stages before maintenance is established (see Fig 7.8). It is not uncommon for an individual who has reached the maintenance stage to relapse and revert to an earlier stage before achieving stable maintenance. When relapse occurs the person is encouraged to view this as part of the cycle of change, not failure – a challenge not a catastrophe.

The five stages of change of the TTM are:

1. Precontemplation – The stage in which the person does not recognise that the behaviour poses health risks and therefore does not perceive a need to change. This may be due to lack of knowledge or information, or the person may be using denial. For example, a person with osteoarthritis may be unaware of the role of exercise in maintaining joint mobility and consequently reduce their physical activity as a strategy to manage pain. A tobacco smoker who rationalises that, ‘My grandfather smoked until he was 80 years old and never suffered any ill effects’ may be utilising denial regarding the risks associated with smoking.

2. Contemplation – The stage in which the person is aware that the behaviour potentially causes health problems but is ambivalent about making a commitment to change. A shift to this stage from precontemplation may be triggered by an event such as when a smoker or a close family member is diagnosed with a smoking-related health problem.

3. Preparation – In this stage the individual acknowledges the risk inherent in the behaviour and makes a commitment to change such as purchasing nicotine patches, tells others of their intention or seeks professional assistance.

4. Action – This is the stage at which intervention is most effective. This is when the individual takes action to change a health behaviour such as the smoker who purchases nicotine replacement patches and enrols for a Quit smoking course.

5. Maintenance or termination – Maintenance is the stage in which the person sustains the desired health behaviour (e.g. smoking cessation), while termination applies to the health behaviours that do not need to be ongoing such as vaccination or health screening.

Transtheoretical model in clinical practice

A strength of the TTM is that it suggests strategies to work with unmotivated clients who previously were not considered amenable to intervention or treatment (Prochaska 2006, Di Clemente et al 2011). This enables the therapist to facilitate movement towards a stage of readiness. After identifying the stage at which the client is at, the therapist can then initiate interventions to facilitate the client moving to the next stage. For example, if the individual is at the precontemplation stage and is unaware of the risk the behaviour poses for their health the therapist can present the relevant health education information to the client to facilitate movement to the next stage. However, if the patient is using denial in this stage, intervention is extremely difficult, whereas intervening at the action stage is more effective because the person is motivated to make changes. This is the stage at which intervention is most likely to be effective in bringing about the desired change in behaviour.

Providing intervention based on an individual's stage of cessation is the principle behind the Australian Quit Now and New Zealand Quitline Me Mutu smoking cessation campaigns. Graphic images of the consequences of smoking on cigarette packets and in television commercials aim to shift smokers from the precontemplation to the contemplation and ultimately action stages. The Quit programs also provide information about access to strategies and support services to assist smokers to move from the contemplation stage through to the action and maintenance stages.

It is important to note that once the person reaches the maintenance stage relapse is still possible, as it is at any of the preceding stages. Should relapse occur the individual's thoughts regarding the relapse will influence what happens next. For example, a person who views relapse as a setback or challenge can plan to return to the stage previously achieved, whereas a person who views relapse as a failure or catastrophe will not be motivated to persevere with the behaviour change.

In summary TTM identifies the stages an individual goes through when making health behaviour changes. It identifies internal and external influences, thereby identifying opportunities for intervention. It is particularly effective for changing addictive (e.g. alcohol and gambling problems) and other behaviours that pose health risks (e.g. unsafe sex).

Motivational interviewing

Miller and Rollnick initially developed motivational interviewing as a therapeutic intervention for use with people who had addictive behaviours such as drug, alcohol or gambling problems, but it is now used for a wide range of health issues (Rollnick & Miller 1995, Rollnick et al 2007). It evolved from the person-centred counselling approach of humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers (Hettema et al 2005) and shares similarities with the TTM in that both interventions aim to encourage the individual to recognise the need for change and then to take action to bring about change. Both models also stress the importance of the individual taking responsibility for initiating and implementing the behaviour change.

In a motivational interview the person is encouraged to explore all the beliefs and values they hold for and against a behaviour that requires change – to thereby create a state of cognitive dissonance (conflict) for the person. The person is asked to make a list of the positive and negative consequences of the behaviour. For example, eliciting statements like ‘gambling gives me a buzz when I win’ and ‘my relationship with my partner is suffering because of my gambling’ are conflicting outcomes of continuing to gamble. The person is then encouraged to make a decision regarding whether or not they wish to stop gambling. If they decide to make the behavioural change (i.e. cease gambling) the therapist then assists the person to develop and implement a plan to facilitate the behaviour change. The key points of the motivational interviewing counselling approach are (Rollnick & Miller 1995, Rollnick et al 2007):

Motivation to change is elicited from the client, and not imposed externally.

Motivation to change is elicited from the client, and not imposed externally.

It is the client's task, not the counsellor's, to articulate his or her ambivalence.

It is the client's task, not the counsellor's, to articulate his or her ambivalence.

Direct persuasion is not an effective method for resolving ambivalence.

Direct persuasion is not an effective method for resolving ambivalence.

The counselling style is generally a quiet and eliciting one.

The counselling style is generally a quiet and eliciting one.

The counsellor is directive in helping the client to examine and resolve ambivalence.

The counsellor is directive in helping the client to examine and resolve ambivalence.

Readiness to change is not a client trait but a fluctuating product of interpersonal interaction.

Readiness to change is not a client trait but a fluctuating product of interpersonal interaction.

The therapeutic relationship is more like a partnership or companionship than expert/recipient roles.

The therapeutic relationship is more like a partnership or companionship than expert/recipient roles.

Four principles underpin a motivational interviewing counselling approach: empathy expression, whereby the counsellor conveys understanding of the person's situation and perspective; non-confrontation, to allow the person to identify the discrepancies for themselves; accept resistance as a part of the process of change; and encourage self-efficacy and optimism regarding the person's ability to change (Rollnick et al 2007).

A significant component of the motivational interviewing approach is for the therapist to resist telling the person what they should or should not do and to not lead the person to a decision by coercion as this can lead to resistance (Palmer 2012). Rather, the role of the therapist is to assist the person to come to their own decision and to assist them in developing and implementing an action plan. See the Research focus for an example of using motivational interviewing to facilitate medication adherence by adolescents with asthma.

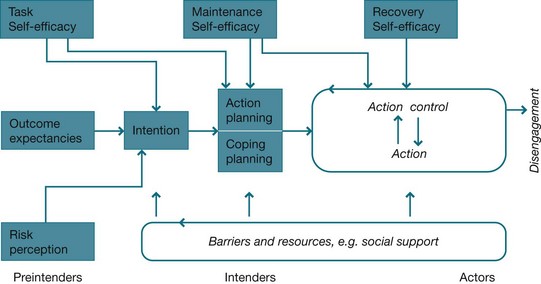

Health action process approach

The health action process approach (HAPA) is a social cognition model that highlights the role of self-efficacy and addresses the ‘intention–behaviour gap’ (Schwarzer 1992, 2011) or why people do or do not complete a behaviour that they intend to complete. The model (see Fig 7.9) adds a social dimension to previous cognitive models.

Figure 7.9 Health action process approach model Schwarzer R 2011 Health action process approach. Online: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/health/hapa.htm

Schwarzer developed the model from research that identified that self-efficacy played a role in the individual's intention to change and subsequently whether change occurred or not. The model makes a distinction between the three stages, being: intention, decision making and motivation; planning and action; and maintenance and recovery. It proposes there are three precursors to change:

self-efficacy or the individual's belief in their ability to action the change

self-efficacy or the individual's belief in their ability to action the change

outcome expectations or the belief as to whether the intended action will improve health or not

outcome expectations or the belief as to whether the intended action will improve health or not

risk perception or whether or not changing will affect health.

risk perception or whether or not changing will affect health.

Of the three precursors Schwarzer suggests that self-efficacy is the best predictor of behavioural outcomes (Schwarzer 2011). Like the TPB, the HAPA proposes that the individual's belief in their ability to carry out the desired behaviour is predictive of the individual's success in doing so. For example, the model would predict that the person who believes he can comply with a recommended dietary change will be more successful in making the change than a person who believes that making the change is too difficult.

Cognitive behavioural therapies

Cognitive behavioural therapies refers to a range of interventions that utilise both cognitive and behavioural strategies to bring about changes in an individual's behaviours and to treat some mental illnesses (including but not limited to depression, anxiety, phobias and schizophrenia) and chronic illness (e.g. chronic fatigue syndrome), and to manage behavioural problems such as addictive behaviours. The underlying premise behind cognitive behavioural therapies is that thoughts, feelings and behaviours are interrelated and changes in one or more will bring about change in one or all of these. Key elements of cognitive behavioural approaches are a focus on:

the present rather than the past, and identifying the problem and its extent (history is acknowledged for its contribution to the present problem but is not the focus of treatment)

the present rather than the past, and identifying the problem and its extent (history is acknowledged for its contribution to the present problem but is not the focus of treatment)

setting goals that are achievable and measurable

setting goals that are achievable and measurable

collaboration between the person and the therapist to set goals and test strategies

collaboration between the person and the therapist to set goals and test strategies

bringing about changes in thoughts, feelings, behaviour and physiological responses (Meadows et al 2007).

bringing about changes in thoughts, feelings, behaviour and physiological responses (Meadows et al 2007).

Limitations of psychological models

While behavioural and cognitive approaches to initiating and maintaining health behaviours can be effective, they do not provide a universal explanation for all people in all situations. Commentators suggest this is because relying on an individual's behavioural response and cognitive process is a narrow approach to understanding human behaviour (Crossley 2000, Murray 2010, Norman 2011). Cognitive and behavioural models of health behaviour do not take into consideration other psychological and social factors that influence the initiation, continuation or cessation of health behaviours.

The models also assume rational decision making and fail to take into account unconscious processes as identified in psychoanalytic theory, such as the defence mechanism of denial. Nor do they acknowledge the contribution of affective states such as fear or the physiological component of some practices such as nicotine addiction in tobacco smoking or genetics. Significantly, the models do not take into account where the person is located in the lifespan or the social contexts of individuals' lives. Social factors (which are examined in more detail in Ch 4) that are not specifically considered in psychological behavioural change theories include:

Socioeconomic status (SES). Does the person have access to the resources required to make the change required?

Socioeconomic status (SES). Does the person have access to the resources required to make the change required?

Social connectedness. Does the person have sufficient social supports to carry out the activity?

Social connectedness. Does the person have sufficient social supports to carry out the activity?

Gender. Do men and women respond in the same way to similar health challenges?

Gender. Do men and women respond in the same way to similar health challenges?

Ethnicity. What role does ethnicity play in health behaviours?

Ethnicity. What role does ethnicity play in health behaviours?

Culture. How applicable are psychological theories developed in Western cultures to people from non-Western cultures?

Culture. How applicable are psychological theories developed in Western cultures to people from non-Western cultures?

Finally, cognitive and behavioural models are better predictors of behavioural intention than they are of behavioural outcomes (Morrison et al 2012). They are, therefore, more effective in predicting who is at risk of health problems but not particularly useful in predicting who will be successful in engaging in health-enhancing behaviours, or who will be successful in changing unhealthy behaviours.

Conclusion

This chapter presented a range of psychological theories and models that propose explanations as to how internal and external factors influence an individual's health behaviours and lifestyle. These theories and models provide useful insights into the motivators and reinforcers regarding why an individual does or does not engage in health-enhancing behaviours or why an individual engages in behaviours that pose health risks. These understandings also identify possibilities to change health behaviours; however, this knowledge needs to be utilised within a framework that also takes account of the social contexts of the person's life.

Chiu, C., Lynch, R., Chan, F., et al. The health action process approach as a motivational model for physical activity self-management for people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011; 65(3):171–181.

Cooper D., ed. Interventions in mental health-substance use. London: Radcliffe, 2011.

Dempsey, A. Predicting oral contraception continuation using the transtheoretical model of behaviour change. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011; 43(1):23–29.

Norman, P. The theory of planned behavior and binge drinking among undergraduate students: assessing the impact of habit strength. Addictive Behaviors. 2011; 36:502–507.

Rollnick, S., Miller, W., Butler, C. Motivational interviewing: helping patients change behavior. New York: Guilford; 2007.

Australian national tobacco campaign

The Australian national tobacco campaign is part of the Australian Government's continuing efforts to reduce the level of tobacco use among Australians and is aimed directly at smokers, both youth and adults.

Flinders University Human Behaviour and Health Research Unit

www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/fhbhru

The Human Behaviour and Health Research Unit is a centre for research, evaluation and development of chronic condition management. The website contains links to the centre's programs, research and publications that focus on coordinated care, care planning, behavioural change and self-management.

www.des.emory.edu/mfp/self-efficacy

This website provides resources and publications about self-efficacy including the writings and video interviews of Albert Bandura.

The health action process approach

http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/hapa.htm

This website provides an overview of research and publications relating to Schwarzer's (2011) health action process model.

References

Ajzen, I., Maddern, M. Predictions of goal directed behaviour: attitudes, intentions and perceived behavioural control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1986; 22:453–474.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2010. Canberra: AIHW; 2010.

Bandura, A. Psychological modeling: conflicting theories, second ed. New Jersey: Aldine Transaction; 2006.

Bandura, A. Principles of behaviour modification. New York: Holt, Rhinehart & Winston; 1969.

Beck, A.T. Cognitive therapy and emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press; 1976.

Chiu, C., Lynch, R., Chan, F., et al. The health action process approach as a motivational model for physical activity self-management for people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011; 65(3):171–181.

Cox, J., De, P., Morissette, C., et al. Low perceived benefits and self-efficacy are associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection-related risk among injection drug users. Social Science and Medicine. 2008; 66:211–230.

Crossley, M. Rethinking health psychology. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2000.

DiClemente, C., Schumann, K., Greene, A., et al. A transtheoretical model perspective on change: process-focussed intervention in mental health-substance use. In: Cooper D., ed. Interventions in mental health-substance use. London: Radcliffe, 2011.

Downing-Matibag, T., Geisenger, B. Hooking up and sexual risk taking among college students: a health belief model perspective. Qualitative Health Research. 2009; 19(9):1196–1209.

Ellis, A. Rational-emotive therapy and cognitive behaviour therapy. New York: Springer; 1984.

Eysenck, H.J. Behaviour therapy and the neuroses. London: Pergamon; 1960.

Frieden, T. A framework for public health: the health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health. 2010; 100(4):590–595.

Harvey, P., Petkov, J., Misan, G., et al. Self-management support and training for patients with chronic and complex conditions improves health related behaviour and health outcomes. Australian Health Review. 2008; 32(2):330–338.

Hettema, J., Steele, J., Miller, W. Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005; 1:91–111.

Krahé, B., Möller, I. Longitudinal effects of media violence on aggression and empathy among German adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010; 31:401–409.

Meadows, G., Singh, B., Grigg, M. Mental health in Australia: collaborative community practice. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Meichenbaum, D.H. Cognitive behaviour modification: an integrative approach. New York: Plenum; 1974.

Morrison, V., Bennett, P., Butow, P., et al. Introduction to health psychology in Australia, second ed. Sydney: Pearson Education; 2012.

Murray, M. Health psychology in context. The European Health Psychologist. 2010; 12:39–41.

Norman, P. The theory of planned behavior and binge drinking among undergraduate students: assessing the impact of habit strength. Addictive Behaviors. 2011; 36:502–507.

Palmer, C. Therapeutic interventions. In Elder R., Evans K., Nizette D., eds.: Practical perspectives in psychiatric and mental health nursing, third ed, Sydney: Elsevier, 2012.

Pavlov, I.P. Conditioned reflexes: an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Trans. G.V. Anrep. London: Oxford University Press; 1927.

Prochaska, J. Moving beyond the transtheoretical model. Addiction. 2006; 101(6):768–778.

Prochaska, J., DiClemente, C.C., Norcross, J.C. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992; 47:1102–1114.

Prochaska, J., DiClemente, C. The transtheoretical approach: crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. Chicago: Dow Jones/Irwin; 1984.

Reikert, K., Borrelli, B., Bilderback, A., et al. The development of a motivational interviewing intervention to promote medication adherence among inner-city African American adolescents. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011; 82:117–122.

Rollnick, S., Miller, W. What is motivational interviewing? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1995; 23:325–334.

Rollnick, S., Miller, W., Butler, C. Motivational interviewing: helping patients change behaviour. New York: Guilford; 2007.

Rosenstock, I. Why people use health services. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1966; 44:94–124.

Rosenstock, I. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monographs. 1974; 2:1–8.

Rosenstock, I. Health belief model: explaining health behavior through expectancies. In: Glanz K., Lewis F.M., Rimer B.K., eds. Health behavior and health education: theory research and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Boss; 1991:39–58.

Schwarzer, R. Self-efficacy: thought control of action. Washington: Hemisphere; 1992.

Schwarzer, R. Health action process approach. Online Available http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/hapa.htm, 2011. [17 Sep 2012].

Skinner, B.F. Science and human behaviour. New York: Macmillan; 1953.

Wolpe, J. Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1958.

Wood, J. Interpersonal communication: everyday encounters, seventh ed. Wadsworth: Cengage Learning; 2012.