Psychology

An introduction

The material in this chapter will help you to:

understand the psychological theories that provide explanations of human behaviour and personality

understand the psychological theories that provide explanations of human behaviour and personality

describe and critique biomedical, psychological and sociological theories of human behaviour

describe and critique biomedical, psychological and sociological theories of human behaviour

apply your knowledge of psychological theory to understand the behaviour of yourself and others

apply your knowledge of psychological theory to understand the behaviour of yourself and others

describe how psychological theory informs interventions in healthcare practice

describe how psychological theory informs interventions in healthcare practice

explain the nature versus nurture debate

explain the nature versus nurture debate

understand the interrelationship between psychological, biological and social influences on human behaviour.

understand the interrelationship between psychological, biological and social influences on human behaviour.

Introduction

Who are you? How have you come to be who you are? What influences how you think, feel and act? Are your personality and behaviour determined by your genetic makeup and biological events, by thoughts and feelings, by your experiences in the world, or by an interrelationship between some or all of these? Most of us, at one time or another, have thought about these questions. Through attempting to understand why humans behave as they do, a further question arises: Are human behaviour and personality determined by genetics and biology (nature) or shaped by one's upbringing, experiences and environmental factors (nurture)?

These questions have long engaged the interest and passion of philosophers, healers and health professionals and, in more recent times, psychologists and scientists. Investigation of these questions has resulted in various theories being proposed to explain normal and abnormal thoughts, feelings and behaviours, as well as mental health and mental illness. These concepts – the theories that attempt to explain and provide understandings of behaviour – will be examined in this chapter. The nature versus nurture debate will also be explored.

Psychology

Psychology is a theoretical and applied discipline that emerged in the 19th century in Europe and North America from the established disciplines of physiology and philosophy. Its principal focus is the scientific study of behaviour. To achieve this psychologists study how organisms (primarily humans but not exclusively) act, think, learn, perceive, feel, interact with others and understand themselves. Nevertheless, given that psychological theory originated in a Western context, caution is recommended when applying psychological theory to people from other cultures such as New Zealand M ori or Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

ori or Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

The discipline of psychology focuses on behavioural responses (including affective and cognitive) to certain sets of conditions. Psychology is both a natural and a social science that attempts to determine the laws of nature at a cellular level (as in bioscientific enquiry) and also to explain human behaviour in individuals and groups. Within the discipline professional psychologists practise in two broad areas: theoretical (research or academic) and applied (clinical practice or organisational psychology).

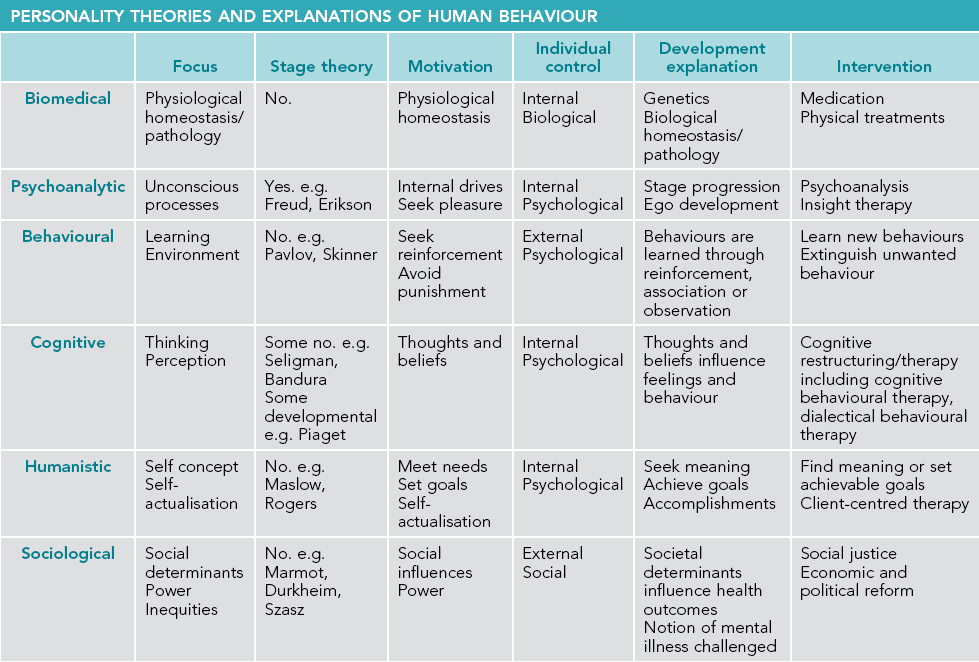

The major theoretical perspectives (also called paradigms) that attempt to explain and predict specific behaviours include psychoanalytic, behavioural (learning), cognitive and humanistic. At times these theories can be complementary, but at other times they can be contradictory. Finally, other theoretical perspectives that are outside the field of psychology are recognised for the role they play in influencing behaviour. These paradigms include the biomedical model and sociological theories.

Theories of personality and human behaviour

Personality theories propose psychological models to explain human behaviours. They emerged from curiosity about and philosophical enquiry into the human condition. The theories also place particular emphasis on identifying the causes of abnormal behaviour so as to develop models for understanding, prevention or treatment of health problems with a behavioural or lifestyle component such as physical activity or tobacco smoking. Explanations of human behaviour can be broadly divided into three paradigms:

biomedical or biological/physical models

biomedical or biological/physical models

psychological models, including psychoanalytic, behavioural, cognitive and humanistic approaches

psychological models, including psychoanalytic, behavioural, cognitive and humanistic approaches

Within these paradigms are a number of major viewpoints that offer a theory of personality development or an explanation of human behaviour. They are listed below.

Biomedical model – proposes that behaviour is influenced by physiology, with normal behaviour occurring when the body is in a state of equilibrium and abnormal behaviour being a consequence of physical pathology.

Biomedical model – proposes that behaviour is influenced by physiology, with normal behaviour occurring when the body is in a state of equilibrium and abnormal behaviour being a consequence of physical pathology.

Psychoanalytic theory – asserts that behaviour is driven by unconscious processes and influenced by childhood/developmental conflicts that have either been resolved or remain unresolved.

Psychoanalytic theory – asserts that behaviour is driven by unconscious processes and influenced by childhood/developmental conflicts that have either been resolved or remain unresolved.

Behavioural psychology – presents the view that behaviour is influenced by factors external to the individual. Behaviours are learned depending on whether they are rewarded or not, by association with another event or by imitation.

Behavioural psychology – presents the view that behaviour is influenced by factors external to the individual. Behaviours are learned depending on whether they are rewarded or not, by association with another event or by imitation.

Cognitive psychology – acknowledges the role of perception and thoughts about oneself, one's individual experience and the environment in influencing behaviour.

Cognitive psychology – acknowledges the role of perception and thoughts about oneself, one's individual experience and the environment in influencing behaviour.

Humanistic psychology – focuses on the development of a concept of self and the striving of the individual to achieve personal goals.

Humanistic psychology – focuses on the development of a concept of self and the striving of the individual to achieve personal goals.

Eclectic approach – (also called holistic) draws on the theory and research of several paradigms to obtain an overall understanding or provide a more comprehensive explanation than would be achieved by using one theoretical model alone. For example, in clinical practice cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a frequently used counselling approach; in research a mixed-methods approach may be utilised.

Eclectic approach – (also called holistic) draws on the theory and research of several paradigms to obtain an overall understanding or provide a more comprehensive explanation than would be achieved by using one theoretical model alone. For example, in clinical practice cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a frequently used counselling approach; in research a mixed-methods approach may be utilised.

Sociological theories – shifts the emphasis from the individual to the broader social forces that influence people. This model challenges the notion of individual pathology and acknowledges the responsibility of society for the health of its citizens.

Sociological theories – shifts the emphasis from the individual to the broader social forces that influence people. This model challenges the notion of individual pathology and acknowledges the responsibility of society for the health of its citizens.

Each of these seemingly disparate perspectives makes a substantial contribution to the understanding of how and why humans think, feel and behave as they do, and thereby identifies opportunities for prevention and treatment of health problems with a behavioural component. Nevertheless, as a comprehensive theory of human behaviour, each also has major shortcomings, hence the practice of using an eclectic approach that utilises more than one theory.

Biomedical model

Also known as psychobiology or the neuroscience perspective, the biomedical model asserts that normal behaviour is a consequence of equilibrium within the body and that abnormal behaviour results from pathological bodily or brain function. This is not a new notion; in the fourth century BC the Greek physician Hippocrates attributed mental disorder to brain pathology. His ideas were overshadowed, however, when throughout the Dark Ages and later during the Renaissance, thinking and explanations shifted to witchcraft or demonic possession (Butcher et al 2011, Kring et al 2010). In the 19th century, a return to biophysical explanations accompanied the emergence of the public health movement.

In recent times, advances in technology have led to increased understanding of organic determinants of behaviour. Research and treatment have focused on four main areas:

Nervous system disorders, in particular neurotransmitter disturbance at the synaptic gap between neurons – more than 50 neurotransmitters have been identified, four of which are implicated in mental illness. These are acetylcholine (Alzheimer's disease), dopamine (schizophrenia), noradrenaline (mood disorder) and serotonin (mood disorder).

Nervous system disorders, in particular neurotransmitter disturbance at the synaptic gap between neurons – more than 50 neurotransmitters have been identified, four of which are implicated in mental illness. These are acetylcholine (Alzheimer's disease), dopamine (schizophrenia), noradrenaline (mood disorder) and serotonin (mood disorder).

Structural changes to the brain – perhaps following trauma or in degenerative disorders such as Huntington's disease.

Structural changes to the brain – perhaps following trauma or in degenerative disorders such as Huntington's disease.

Endocrine or gland dysfunction, as in hypothyroidism – this has a similar presentation to clinical depression and hormonal changes are considered to be a contributing factor in postnatal depression.

Endocrine or gland dysfunction, as in hypothyroidism – this has a similar presentation to clinical depression and hormonal changes are considered to be a contributing factor in postnatal depression.

Familial (genetic) transmission of mental illness – twin studies reviewed by Irving Gottesman found the following lifetime risks of developing schizophrenia: general population 1%, one parent 13%, sibling 9%, dizygotic (non-identical) twin 17%, two parents 46% and monozygotic (identical) twin 48% (Butcher et al 2011, Cando & Gottesman 2000).

Familial (genetic) transmission of mental illness – twin studies reviewed by Irving Gottesman found the following lifetime risks of developing schizophrenia: general population 1%, one parent 13%, sibling 9%, dizygotic (non-identical) twin 17%, two parents 46% and monozygotic (identical) twin 48% (Butcher et al 2011, Cando & Gottesman 2000).

Although genetic studies demonstrate a correlation between having a close relative with schizophrenia and the likelihood of developing the disorder, a shared genetic history alone is not sufficient. If genetics were the only aetiological factor, the concordance rate for monozygotic twins could be expected to be 100%. Gottesman's (1991, 1997) research is important because it supports the diathesis-stress hypothesis, a widely held explanation for the development of mental disorder that proposes that constitutional predisposition combined with environmental stress will lead to mental illness (Kring et al 2010).

Critique of the biomedical model

Among treatments that emerge from the biomedical model are medications that alter the function, production and reabsorption of neurotransmitters in the synaptic gap. However, evidence that a particular intervention is an effective treatment is not proof of a causal link with the illness. For example, consider a person with type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Because this person lacks insulin to metabolise glucose, the condition is managed with regular insulin injections. However, the lack of insulin is a symptom of the disease, not the cause. Whatever caused the pancreas to cease producing insulin is not known, despite the treatment being effective. Similarly, with schizophrenia, the relationship between taking antipsychotic medications (which are dopamine antagonists), dopamine levels and symptom management is correlational, not causal. Therefore, although antipsychotic medication affects dopamine receptors and hence dopamine levels, and can be an effective treatment to manage the symptoms of schizophrenia, this does not provide evidence that elevated dopamine levels cause the disorder.

Psychoanalytic theory

Sigmund Freud developed the first psychological explanation of human behaviour – psychoanalytic theory – in the late 19th century. He placed strong emphasis on the role of unconscious processes (not in the conscious mind of the individual) in determining human behaviour. Central tenets of the theory are that intrapsychic (generally unconscious) forces, developmental factors and family relationships determine human behaviour. According to psychoanalytic theory normal development results when the individual satisfactorily traverses each developmental stage and mental illness is seen as a consequence of fixation at a particular developmental stage or conflict that has not been resolved.

Sigmund Freud

Freud (1856–1939) was an Austrian neurologist who, in his clinical practice, saw a number of patients with sensory or neurological problems for which he was unable to identify a physiological cause. These patients were mainly middle-class Viennese women. It was from his work with these patients that Freud hypothesised that the cause of their illnesses was psychological. From this assumption he developed an explanation of personality development, which he called psychoanalytic theory. According to Freud the mind is composed of three forces:

The id – the primitive biological force comprising two basic drives: sexual and aggressive. The id operates on the pleasure principle and seeks to satisfy life-sustaining needs such as food, love and creativity, in addition to sexual gratification.

The id – the primitive biological force comprising two basic drives: sexual and aggressive. The id operates on the pleasure principle and seeks to satisfy life-sustaining needs such as food, love and creativity, in addition to sexual gratification.

The ego – the cognitive component of personality that attempts to use realistic means (the reality principle) to achieve the desires of the id.

The ego – the cognitive component of personality that attempts to use realistic means (the reality principle) to achieve the desires of the id.

The superego – the internalised moral standards of the society in which one lives. It represents the person's ideal self and can be equated to a conscience.

The superego – the internalised moral standards of the society in which one lives. It represents the person's ideal self and can be equated to a conscience.

Freud's theory proposes that personality development progresses through five stages throughout childhood. At each stage the child's behaviour is driven by the need to satisfy sexual and aggressive drives via the mouth, anus or genitals. Failure of the child to satisfy these needs at any one of the stages will result in psychological difficulties that are carried into adulthood. For example, unresolved issues at the oral stage can lead to dependency issues in adulthood; problems in the anal stage may lead to the child later developing obsessive-compulsive traits. Freud's stages of psychosexual development are:

1. oral – from birth to about 18 months, where the primary focus of the id is the mouth

2. anal – from approximately 18 months to three years, where libido shifts from the mouth to the anus and primary gratification is derived from expelling or retaining faeces

3. phallic – from approximately three to six years, where gratification of the id occurs through the genitals

4. latent – Freud proposed that from approximately six to 12 years, the child goes through a latency phase in which sexual urges are dormant

5. genital – once the child passes through puberty, sexual urges re-emerge but now they are directed towards another person, not the self as they were at an earlier stage of development (Butcher et al 2011, Kring et al 2010).

Defence mechanisms

An important contribution of psychoanalytic theory to the understanding of behaviour has been the identification of defence mechanisms and the role they play in mediating anxiety. Defence mechanisms were first described by Freud and later elaborated on by his daughter, Anna (Freud 1966). They are unconscious, protective processes whereby anxiety experienced by the ego is reduced. Commonly used defence mechanisms include:

repression – the primary defence mechanism and an unconscious process whereby unacceptable impulses/feelings/thoughts are barred from consciousness (e.g. memories of sexual abuse in childhood)

repression – the primary defence mechanism and an unconscious process whereby unacceptable impulses/feelings/thoughts are barred from consciousness (e.g. memories of sexual abuse in childhood)

regression – the avoidance of present difficulties by a reversion to an earlier, less mature way of dealing with the situation (e.g. a toilet-trained child who becomes incontinent following the birth of a sibling)

regression – the avoidance of present difficulties by a reversion to an earlier, less mature way of dealing with the situation (e.g. a toilet-trained child who becomes incontinent following the birth of a sibling)

denial – the blocking of painful information from consciousness (e.g. not accepting that a loss has occurred)

denial – the blocking of painful information from consciousness (e.g. not accepting that a loss has occurred)

projection – the denial of one's own unconscious impulses by attributing them to another person (e.g. when you dislike someone but believe it is the other person who does not like you)

projection – the denial of one's own unconscious impulses by attributing them to another person (e.g. when you dislike someone but believe it is the other person who does not like you)

sublimation – an unconscious process whereby libido is transformed into a more socially acceptable outlet (e.g. creativity, art or sport)

sublimation – an unconscious process whereby libido is transformed into a more socially acceptable outlet (e.g. creativity, art or sport)

displacement – the transferring of emotion from the source to a substitute (e.g. a person who is unassertive in an interaction with a supervisor at work and ‘kicks the cat’ on arriving home)

displacement – the transferring of emotion from the source to a substitute (e.g. a person who is unassertive in an interaction with a supervisor at work and ‘kicks the cat’ on arriving home)

rationalisation – a rational excuse is used to explain behaviour that may be motivated by an irrational force (e.g. cheating when completing a tax return, with the excuse that ‘everyone does it’)

rationalisation – a rational excuse is used to explain behaviour that may be motivated by an irrational force (e.g. cheating when completing a tax return, with the excuse that ‘everyone does it’)

intellectualisation/isolation – feelings are cut off from the event in which they occur (e.g. after an unsuccessful job interview the person says, ‘I didn’t really want the job anyway’)

intellectualisation/isolation – feelings are cut off from the event in which they occur (e.g. after an unsuccessful job interview the person says, ‘I didn’t really want the job anyway’)

reaction formation – developing a personality trait that is the opposite of the original unconscious or repressed trait (e.g. avoiding a friend's partner because you are attracted to that person).

reaction formation – developing a personality trait that is the opposite of the original unconscious or repressed trait (e.g. avoiding a friend's partner because you are attracted to that person).

Being aware of defence mechanisms and the role they play in managing anxiety can assist health professionals to understand that a person's seemingly irrational behaviour may have an unconscious cause. For example, the child who regresses following a serious illness is not attention seeking, but reverting to behaviours from a time when they felt safe.

Critique of psychoanalytic theory

Although the notions of unconscious motivations and defence mechanisms are helpful in interpreting behaviours, Freud's version of psychoanalytic theory has not been without its critics. Fellow psychoanalyst Erik Erikson disagreed with Freud's theory of psychosexual stages of development and proposed instead a psychosocial theory in which development occurred throughout the lifespan not just through childhood as in Freud's model (e.g. Erikson 1963, Santrock 2009). (See Chs 2 and 3 for more detail on developmental theories.)

The unconscious nature of Freud's concepts and stages renders them difficult to test and therefore there is little evidence to support Freudian theory. Feminists also object to Freud's interpretation of the psychological development of women, arguing that there is scant evidence to support the hypothesis that women view their bodies as inferior to men's because they do not have a penis (Kring et al 2010). Nevertheless, despite these criticisms, psychoanalytic theory does provide plausible explanations for seemingly irrational behaviour.

Behavioural psychology

Behavioural psychology (also called behaviourism) is a school of psychological thought founded in the United States by J B Watson in the early 20th century with the purpose of objectively studying observable human behaviour, as opposed to examining the mind, which was the prevalent psychological method at the time in Europe. The model proposes a scientific approach to the study of behaviour, a feature that behaviourists argue is lacking in psychoanalytic theory (and in humanistic psychology, which developed later).

Behaviourism opposes the introspective, structuralist approach of psychoanalysis and emphasises the importance of the environment in shaping behaviour. The focus is on observable behaviour and conditions that elicit and maintain the behaviour (classical conditioning) or factors that reinforce behaviour (operant conditioning) or vicarious learning through watching and imitating the behaviour of others (modelling).

Three basic assumptions underpin behavioural theory. These are that personality is determined by prior learning, that human behaviour is changeable throughout the lifespan and that changes in behaviour are generally caused by changes in the environment. The following people were prominent figures in the development of behavioural psychology.

Ivan Pavlov

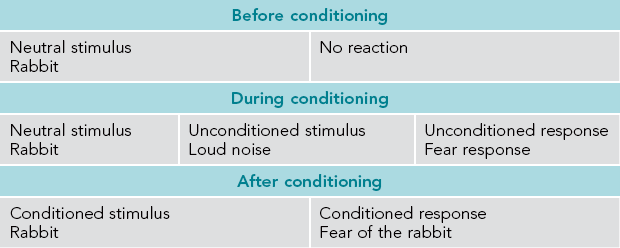

Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) was the first to describe the relationship between stimulus and response. Pavlov demonstrated that a dog could learn to salivate (respond) to a non-food stimulus (a bell) if the stimulus was simultaneously presented with the food. His discovery became known as learning by association or classical conditioning. Phobias and fear, for example, can be explained by classical conditioning. See Table 1.1 for an explanation of how fear or phobia of a rabbit (an animal that is not normally feared) can develop.

John B Watson

Watson (1878–1958), who is attributed as being the founder of behaviourism, changed the focus of psychology from the study of inner sensations to the study of observable behaviour. In his quest to make psychology a true science Watson further developed Pavlov's work on stimulus–response learning and experimented by manipulating stimulus conditions. In the classic ‘Little Albert’ experiment Watson and his colleague Rayner (1920) conditioned a young child to fear a white rat by producing a loud noise at the same time that Albert touched the rat (which he initially did not fear). Albert's fear reaction also generalised to other furry objects such as a fur coat and a white rabbit.

Watch it on YouTube! For a short video of the ‘Little Albert’ experiment see <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9hBfnXACsOI>.

Furthermore, Watson believed that abnormal behaviours were the result of earlier faulty conditioning and that reconditioning could modify these behaviours. His work heralded the introduction of psychological approaches to treat problem behaviours.

B F Skinner

Skinner (1904–1990) formulated the notion of instrumental or operant conditioning in which reinforcers (rewards) contribute to the probability of a response being either repeated or extinguished. Skinner believed that behaviour was the result of an interaction between the individual and the environment and, because the environment was more readily amenable to change, this was the most appropriate place to intervene to bring about change. His research demonstrated that by changing contingencies that were external to the person, behaviour could be altered. This is an underlying principle in interventions using an operant conditioning or learning by consequence approach (Skinner 1953).

Critique of behavioural psychology

Behaviourism provided the first scientifically testable theories of human development, as well as plausible explanations of how behaviours are learned and, in the clinical arena, how conditions such as addictions, depression, phobias and anxiety develop. Behavioural principles underpin many approaches to behaviour change (these are discussed more fully in Ch 7). Behavioural explanations are less convincing, however, when applied to complex human emotions (e.g. compassion) or behaviours (e.g. altruism), or the behaviours of a person with a medical condition like dementia. Furthermore, most behavioural research has been conducted on animals under laboratory conditions, so to extrapolate findings from this research to humans is mechanistic and does not allow for intrinsic human qualities like creativity or altruism. Finally, behavioural theory falls short in explaining the success of an individual brought up in an adverse environment or why a person whose environment is apparently healthy and advantaged engages in deviant or antisocial behaviour.

Cognitive psychology

Since the 1950s, interest in the cognitive or thinking processes involved in behavioural responses has expanded. Cognitive psychological theory proposes that people actively interpret their environment and cognitively construct their world. Therefore, behaviour is a result of the interplay of external and internal events. External events are the stimuli and reinforcements that regulate behaviour and internal events are one's perceptions and thoughts about oneself and the world, as well as one's behaviour in the world. In other words, how you think about a situation will influence how you behave in that situation. The following people are prominent figures in the development of cognitive psychology.

Albert Bandura

According to Bandura (b. 1925) it is not intrapsychic or environmental forces alone that influence behaviour. Rather, human behaviour results from the interaction of the environment with the individual's perception and thinking. Self-efficacy, or the belief that one can achieve a certain goal, is the critical component in the achievement of that goal. Bandura also proposed that consequences do not have to be directly experienced by the individual for learning to occur – learning can occur vicariously through the process of modelling or learning by imitation (Bandura 2000, 2006, 2012).

Aaron T Beck

Problem behaviour, says Beck (b. 1921), results from cognitive distortions or faulty thinking. For example, a depressed person will selectively choose information that maintains a gloomy perspective. Depression is experienced when one has a negative schema about oneself or one's situation. According to Beck, depression is a behavioural response to an attitude or cognition of hopelessness, as opposed to hopelessness being a symptom of depression. Anxiety, he says, is experienced when the person has a distorted anticipation of danger. Treatment within Beck's model involves changing the person's views about themselves and their life situation (Beck 1972, Beck et al 2005).

Martin Seligman

Seligman (b. 1942) first proposed his theory of learned helplessness as an explanation for depression. The theory suggests that if an individual experiences adversity, and attempts to alleviate the situation are unsuccessful, then depression follows. Seligman later expanded his model to include learned optimism (Seligman 1994): a process of challenging negative cognitions to change from a position of passivity to one of control. He currently conducts research to investigate factors and circumstances that enable humans to flourish. Seligman's theoretical approach is called positive psychology (Seligman 2004, 2011).

Critique of cognitive psychology

The therapeutic techniques derived from cognitive (and cognitive behavioural) theory are practical and effective, and can be self-administered by the client under the direction of a therapist. These therapies have an established record in changing problem behaviours such as phobias, obsessions and compulsions, and in stress management (Butcher et al 2011). They also make a contribution in the treatment of depression and schizophrenia, though whether the treatment result is more effective than other interventions is inconclusive in the literature (Lynch et al 2010, Turkington et al 2004). Furthermore, cognitive theory is criticised as being unscientific (as are psychoanalytic and humanistic theories) because mental processes cannot be objectively observed and subjective reports are not necessarily reliable (Kring et al 2010). Additionally, the insight that one's thinking is the cause of one's problems will not in itself bring about behaviour change.

Finally, contrary to the proposal that thoughts influence feelings, which in turn influence behaviour (a notion that underpins the cognitive approach), research conducted by Kearns and Gardiner (2010) into procrastination and motivation among postgraduate university students suggests that if the behaviour is changed first – that is, the student starts working on their study – then the student will feel more motivated and procrastination will be reduced. These findings can be explained by the relational model of Ivey, Ivey and Zalaquett (2010) in which thoughts, feelings and behaviour interact with each other and with meaning, in contrast to the linear unidirectional explanation of cognitive psychology (see Ivey et al 2010 Fig 8.1). The thrust of the interactive model is that a change in any one part of the system may result in a change in other parts as well (Ivey et al 2010 p 294). So while cognitions play an integral part in behavioural outcomes, they may not necessarily be the initiating factor as proposed by cognitive theory.

Humanistic psychology

Following disenchantment with the existing psychological theories of the time, Charlotte Bühler, Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers and their colleagues in the United States established the Association for Humanistic Psychology in 1962. Humanistic psychology has its intellectual and social roots in philosophical humanism and existentialism, which brought psychology back to a close relationship with philosophy (Bühler & Allen 1972). This school of psychology, which became known as the Third Force, arose in response to dissatisfaction at the time with the mechanistic approach of psychoanalysis and behaviourism and the negative views of humankind that were implicit in both these theoretical perspectives.

Humanist psychologists objected to the determinism of the two prevailing theories: psychoanalysis, with its emphasis on unconscious drives; and behaviourism, which saw the environment as central in shaping behaviour. Humanistic psychology rejected the reductionism of explaining human behaviour, feelings, thinking and motivation merely in terms of psychological mechanisms or biological processes. It also opposed the mechanistic approach of behaviourism and psychoanalysis for the way in which they minimised human experience and qualities such as choice, creativity and spontaneity.

Humanistic psychologists focused on the intrinsic human qualities of the individual, such as free will, altruism, self-esteem, freedom and self-actualisation, qualities which, they asserted, distinguished humans from other animals. Humanistic psychology therefore differed from its predecessors in its emphasis on the whole person, human emotions, experience and the meaning of experience, the creative potential of the individual, choice, self-realisation and self-actualisation. The theory also opposed dualistic (subject/object–mind/body splits), deterministic, reductionistic and mechanistic explanations of human behaviour.

The humanistic movement also reflected a historical trend in Western industrialised cultures at that time, namely an interest in the worth of the individual and the meaning of life and to be concerned about the rise of bureaucracy, the threat of nuclear war, the growing emphasis on scientific/positivist paradigms, alienation of the individual and consequent loss of individual identity in mass society. This led to humanistic psychology being aligned with the philosophical school of existentialism, as well as being associated with the human potential movements of the 1960s and 1970s, the legacy of which can be seen today in individual and group counselling approaches. Humanistic psychology also played a part in the growing interest in qualitative research methods (see Ch 6) that seek to understand the experience of the individual and the meaning of the experience, such as phenomenology. The following people were prominent figures in the development of humanistic psychology.

Charlotte Bühler

Bühler (1893–1974) distinguished her theory from Freudian psychoanalysis with the thesis that development was lifelong, goals were personally selected and that the individual was searching for meaning in life beyond their own existence. She maintained that self-fulfillment was the key to human development and that this was achieved by living constructively, establishing a personal value system, setting goals and reviewing progress to thereby realise one's potential. Throughout the lifespan, according to Bühler, individuals strive to achieve four basic human tendencies, which are to:

satisfy one's need for sex, love and recognition

satisfy one's need for sex, love and recognition

engage in self-limiting adaptation in order to fit in, belong and feel secure

engage in self-limiting adaptation in order to fit in, belong and feel secure

express oneself through creative achievements

express oneself through creative achievements

uphold and restore order so as to be true to one's values and conscience (Bühler & Allen 1972, Ragsdale 2003).

uphold and restore order so as to be true to one's values and conscience (Bühler & Allen 1972, Ragsdale 2003).

Carl Rogers

Rogers (1902–1987) proposed a more hopeful and optimistic view of humankind than that of his psychoanalytic and behaviourist contemporaries. He believed that each person contained within themselves the potential for healthy, creative growth. According to Rogers, the failure to achieve one's potential resulted from constricting and distorting influences of poor parenting, education or other social pressures. Client-centred therapy is the counselling model that Rogers developed to assist the individual to overcome these harmful effects and take responsibility for their life (Rogers 1951, 1961).

Abraham Maslow

As a frequently cited author in the healthcare literature, Maslow (1908–1970) is renowned for his theory of human needs. Maslow, like Bühler and Rogers, premised his theory on the notion that human beings are intrinsically good and that human behaviour is motivated by a drive for self-actualisation or fulfillment. Maslow (1968) identifies three categories of human need:

belongingness and love (connection with others, to be accepted and to belong)

belongingness and love (connection with others, to be accepted and to belong)

self-esteem (to achieve, be competent, gain approval and recognition)

self-esteem (to achieve, be competent, gain approval and recognition)

to achieve one's innate potential (Gething et al 2004, Maslow 1968).

to achieve one's innate potential (Gething et al 2004, Maslow 1968).

Typically, Maslow's needs are represented in a hierarchical pyramid with fundamental needs at the base of the triangle and self-actualisation at the top, although Maslow did not describe his model in this way, nor did he suggest that progression through the hierarchy was in one direction (i.e. ascending) as his model is often depicted. For example, one may have a positive sense of self (self-esteem needs met) but be vulnerable regarding safety needs during a natural disaster like a tsunami.

Critique of humanistic psychology

Intuitively, humanistic psychology appeals as a positive, optimistic view of humankind with its focus on personal growth, not disorder. However, this can also be a criticism in that, as a theory, humanistic psychology is naïve and incomplete. If humans are driven by a need to achieve their best and to live harmoniously with others as Bühler, Rogers and Maslow suggest, how does this account for disturbed states like depression or antisocial behaviour like assault? Humanistic concepts can be difficult to define objectively, thereby posing a challenge for scientific investigation of the theory. Finally, there is little recognition of unconscious drives in explaining behaviour, which limits the ability of the theory to contribute to an understanding of abnormal, deviant or antisocial behaviour.

Eclectic approach

An eclectic or holistic approach is used in both psychological research and clinical practice. For example, initially Seligman's theory of learned helplessness (to explain depression) was underpinned by cognitive principles (Seligman 1974). However, as Seligman (2004, 2011) broadened his theory to seek explanations for happiness and wellbeing, and to establish a branch of psychology, which he called positive psychology, he integrated theoretical principles from cognitive psychology (e.g. focus on strengths, setting of achievable goals), humanistic psychology (e.g. the seeking of meaning) and sociology (e.g. the importance of relationships). Joseph, an advocate of such an approach states ‘[t]he convergence of interests between humanistic and positive psychology promises to provide new avenues for research and theory development’ (Joseph 2008 p 223). Furthermore, in healthcare practice settings, biomedical and psychological interventions are frequently used concurrently to achieve better outcomes, as demonstrated in the following Research focus.

Sociological theories

Sociological and psychological theories differ in that sociological theories do not seek explanations for individual behaviour; rather, they examine societal factors for their influence on the behaviour of its members (see Ch 5). Sociologists propose that the origin of behaviour (both normal and abnormal) lies not in the individual's mind but in the broader social forces of the society in which the individual lives. For example, demographic factors for which patterns of mental illness are observed include:

age – the elderly are more likely to suffer from depression

age – the elderly are more likely to suffer from depression

gender – the suicide rate for men is higher than for women, although the rate for attempted suicide is higher for women than for men

gender – the suicide rate for men is higher than for women, although the rate for attempted suicide is higher for women than for men

socioeconomic status – poverty is associated with poorer physical and mental health outcomes

socioeconomic status – poverty is associated with poorer physical and mental health outcomes

marital status – depression and alcohol problems are two to three times more prevalent in people who have never married or are divorced than among people who are married (AIHW 2012, NZ Ministry of Health 2010).

marital status – depression and alcohol problems are two to three times more prevalent in people who have never married or are divorced than among people who are married (AIHW 2012, NZ Ministry of Health 2010).

The following social commentators propose interpretations of mental illness that challenge the notion of individual pathology.

Emile Durkheim

Durkheim's (1858–1917) classic study of suicide led him to postulate a societal rather than an individual explanation for this phenomenon. He argued that suicide was not an individual act but that it could be understood in terms of the bonds that exist between the person and society or the regulation of the individual by social norms. Durkheim's analysis of suicide statistics found that suicide was more prevalent in groups where the bond between the individual and the group was overly weak or strong, or where the regulation of individual desires and aspirations by societal norms was either inadequate or excessive. According to Durkheim there are four types of suicide:

egoistic – where the social bonds of attachment are weak and the individual is less integrated into the social group and therefore not bound by its obligations (e.g. unmarried men)

egoistic – where the social bonds of attachment are weak and the individual is less integrated into the social group and therefore not bound by its obligations (e.g. unmarried men)

altruistic – where the social bonds of attachment are overly strong and the individual's sense of self is not distinguished from the group; the individual may be driven to suicide by a commitment to the group (e.g. suicide bombers)

altruistic – where the social bonds of attachment are overly strong and the individual's sense of self is not distinguished from the group; the individual may be driven to suicide by a commitment to the group (e.g. suicide bombers)

anomic – where regulation of the individual's desires and aspirations is not adequate: this can occur in a society undergoing rapid change, which dislocates social norms, as has been the experience of farmers who have had to adjust to the change in their economic circumstances as a result of the rural economic downturn

anomic – where regulation of the individual's desires and aspirations is not adequate: this can occur in a society undergoing rapid change, which dislocates social norms, as has been the experience of farmers who have had to adjust to the change in their economic circumstances as a result of the rural economic downturn

fatalistic – where there is over-regulation by society that renders a sense of powerlessness in the individual and predisposes the person to suicide (e.g. deaths in custody) (Durkheim 1951).

fatalistic – where there is over-regulation by society that renders a sense of powerlessness in the individual and predisposes the person to suicide (e.g. deaths in custody) (Durkheim 1951).

Thomas Szasz

Since the 1960s prominent psychiatrist Thomas Szasz (1920–2012) challenged the concept of mental illness, arguing that disease implies a pathology that often cannot be objectively identified (Szasz 1961, 2000). He attacked the biomedical model, claiming that its purpose was to give control over people's lives to psychiatrists and argued that psychiatrists exercised coercive domination in the guise of protecting the public and the ‘mad from their madness’ (Szasz 2000 pp 44–45). Contrary to the illusion that psychiatry was coping well with society's vexing problems, Szasz claimed that social problems were in fact being obfuscated and aggravated by the disease interpretation of psychiatry (Szasz 2000 p 53).

Critique of sociological models

Sociological models identify social determinants of health (WHO 2008), vulnerable populations and health promotion opportunities (Navarro 2009), as well as biases that influence diagnosis and treatment. It is important to note, however, that although social determinants are associated with better or poorer health outcomes, the relationships are correlational and cannot be assumed to be in themselves causative. Nevertheless, the contribution of population statistics and social demographic data remains significant. By identifying social determinants that are associated with protective factors for mental health and risk factors for mental illness, potential areas for prevention and intervention are thereby identified. For example, the Australian Government's suicide prevention plan Mental health: Taking action to tackle suicide was developed in response to the Senate Committee's report, The hidden toll: suicide in Australia, which identified at risk population groups as ‘Indigenous Australians; men; young people; gay, lesbian, bisexual and intersex communities; those bereaved by suicide; those living with mental health disorders and people living in rural areas’ (Commonwealth of Australia 2010 p 1).

Personality theories and explanations of human behaviour

Table 1.2 outlines the key features of the major biomedical, psychological and sociological theories that propose explanations of human behaviour. These theories inform our understanding of ourselves and others and underpin interventions for health promotion, health behaviour change and treatments for mental illness.

Personality and behaviour: nature versus nurture

Who or what is responsible for personality and human development: heredity or the environment? Philosophers have long debated this issue, though scientific interest is more recent, dating from the work of Galton. Galton was a 19th-century British pioneer in the study of individual differences and is reportedly credited with proposing the immortal phrase nature versus nurture (Gottesman 1997, Schaffner 2001). The ensuing debate resulted in a proliferation of philosophical discussion about, and scientific investigation into, the effects of biological phenomena and inheritance (nature) and the individual's environment and experiences in the world (nurture).

Theoretical perspectives on nature versus nurture

The theories discussed in this chapter place varied emphasis on whether hereditary or environmental factors play a more important role in personality development, human behaviour and mental illness. Behavioural and cognitive psychology advocate for the environment and factors external to the individual being more influential, as does the sociological perspective, though for different reasons. The biomedical model argues for a nature explanation, while psychoanalytic theory and humanistic psychology acknowledge the contribution of both. The psychoanalytic concept of the id, for instance, is biological but it interacts with the environment in personality development. In humanistic psychology the need to achieve one's potential is considered to be innate, but the eventual outcome is influenced by the person's experiences in the world.

Nature or nurture?

There is an abundance of evidence to support an interactive explanation of nature and nurture rather than the answer being found in the either/or proposal (Gottesman 1991, Gottesman & Shields 1976, Hunter & Woodroofe 2005). Despite this, some commentators and theorists continue to advocate for the relative importance of one over the other, notably exponents of the biomedical model for nature and behaviourism for nurture.

Evidence to support a genetic or nature position can be found in family, twin and adoptee studies. Research over the past 20 years demonstrates that human behaviour, personality and mental illness do have a genetic component (Gottesman 1991, Gottesman & Shields 1976, Keshavan et al 2005). Findings from studies into the heritability of intelligence (IQ) offer the most convincing nature evidence. An American, British and Swedish study of 240 octogenarian twins found the heritability of IQ to be 62% (Gottesman 1997). In the Colorado Adoption Project a correlation was found between the IQ of adopted adolescents and their birth parents but no relationship was found between the IQ of adopted adolescents and their adoptive parents. The researchers concluded that the environment in which the young person was reared had little impact on cognitive ability.

In the case of schizophrenia, however, heredity accounts for less than 50% of the predictability of the disorder. Genetic inheritance is only a partial influence, with the environment accounting for the rest. Gottesman's research found that even when an identical twin had schizophrenia, the likelihood of the other twin not developing schizophrenia was 52% (Gottesman 1991). In addition, 63% of people with schizophrenia do not have a first- or second-degree relative with the condition (Schaffner 2001). It is clearly evident, therefore, that factors in addition to one's genetic inheritance influence whether the disorder manifests. Such factors, it is assumed, can be found in the environment.

Gottesman's research assumes that siblings reared together share the same environment. Schaffner (2001) recommends caution in presuming this, as different siblings in the same family do not necessarily experience exactly the same environment. Siblings do share many experiences, such as the same parents, social class and home environment; however, other experiences are unique to the individual and not shared by siblings. This non-shared environment can include such experiences as birth trauma, illness and different schooling. Significantly, it appears that it is the non-shared environment that accounts for most of the environmental influence on children's personality and mood (Santrock 2009) and that behaviour is a result of the interplay between the inherited characteristics and the environment rather than either/or (Rutter 2006).

Nature and nurture

An individual's personality does not develop without a genetic inheritance, nor can it develop in the absence of influences from experience and the environment. How, then, can the nature versus nurture debate be resolved?

Gestalt psychology, founded by Fritz Perls (1893–1970) in the 1960s, comprises humanistic and existentialist elements and offers a model for understanding the nature versus nurture debate – that is, to view personality development as a gestalt. There is no exact English equivalent for this German term but it loosely translates as ‘a meaningful, organised whole’ that is more than the sum of its parts (Perls et al 1973 p 16). Consider a cake, for example: flour, eggs, milk and sugar are its basic ingredients, but the product or gestalt bears no resemblance to any of the original ingredients. Yet each of the ingredients is vital to the final product, as is the process of cooking. Leave out the sugar and it will not taste like a cake; omit the heating process and it will not have the texture of a cake.

Considering human personality development as a gestalt means that neither nature nor nurture can be considered in isolation from the other. The process of their interaction and the context in which they interact are significant. Attributing a relative value of one over the other serves no purpose. Both nature and nurture are vital, inseparable, interdependent components of personality and human development that also influence human behaviour and health outcomes.

Conclusion

The theoretical perspectives discussed in this chapter provide complementary, overlapping and, at times, contradictory theories of human behaviour and personality development. Yet despite individual theories being able to provide plausible explanations for specific human behaviours, no theory alone is sufficient to explain all human behaviour or a single behaviour in all circumstances. Additionally, the theories must be used cautiously when being applied to people from non-Western cultures.

Some psychological theories offer a nature, others a nurture, explanation, and yet others incorporate both. Even when a specific theory provides convincing evidence to support a nature or nurture explanation, such evidence is generally correlational and therefore cannot be considered to be causative. Consequently, in seeking to identify factors that influence personality development and human behaviour, it is evident that the answer will not be found in asking the nature or nurture question; rather, in investigating how the nature is nurtured.

In conclusion, although psychological theories do have limitations, they nonetheless provide insightful understandings of human behaviour and explanations of personality in many contexts. These theories can be used by health professionals to understand the motivations and behaviours of the people they care for and to plan appropriate interventions and care. Furthermore, humans are biological beings who exist in a social context therefore psychological theories must be utilised within a biopsychosocial framework that also acknowledges these other influences.

Note: This chapter is an adaptation of Barkway P 2012 Ch 8, Beyond theory: Understanding theories of mental health and mental illness. In: Elder R, Evans K, Nizette D (eds) Practical perspectives in psychiatric and mental health nursing, 3rd edn. Elsevier, Australia.

Further resources

Bandura A., ed. Psychological modeling: conflicting theories, second ed, New Jersey: Aldine Transaction, 2006.

Carducci, B. The psychology of personality: Viewpoints, research and application, second ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

Germov J., ed. Second opinion: an introduction to health sociology, forth ed, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Kring, A., Johnson, S., Davison, G., et al. Abnormal psychology, eleventh ed. New York: Wiley; 2010.

Seligman, M. Flourish: a new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press; 2011.

van Lange, P., Kruglanski, A., Higgins, E. Handbook of theories of social psychology; Vol. 1. Sage, London, 2012.

About.com: psychology theories

http://psychology.about.com/od/psychology101/u/psychology-theories.htm

This website provides an overview of the major psychological and developmental theories.

American Psychological Association

This website contains useful information about psychology topics, publications and resources.

http://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu/Default.aspx

This website contains information about positive psychology, which focuses on the empirical study of wellbeing, positive emotions, strengths-based research.

The Australian Psychological Society

The Australian Psychological Society is the peak professional association for psychologists in Australia. The society's website contains information relevant to psychologists and health professionals and provides academic resources, publications and community information.

The New Zealand Psychological Society

The New Zealand Psychological Society is the premier professional association for psychologists in New Zealand. The society's website contains information about the society, membership, services and publications, as well as acting as a gateway to psychology in New Zealand.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australia's health 2012. Canberra: AIHW; 2012.

Bandura, A., Social cognitive theory, Ch 17. 2012. Handbook of theories of social psychology. van Lange, P., Kruglanski, A., Higgins, E., eds. 2012. Handbook of theories of social psychology; Vol. 1. Sage, London, 2012.

, Psychological modeling: conflicting theoriesBandura, A., eds. second ed. Aldine Transaction, New Jersey, 2006.

Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001; 52:1–26.

Beck, A. Depression: causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1972.

Beck, A., Emery, G., Greenberg, R.L. Anxiety disorders and phobias: a cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books; 2005.

Bühler, C., Allen, M. Introduction to humanistic psychology. California: Brooks/Cole; 1972.

Butcher, J., Mineka, S., Hooley, K. Abnormal psychology: care concepts. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2011.

Cando, A., Gottesman, I.I. Twin studies of schizophrenia: from bow-and-arrow concordances to Star Wars Mx and functional genomics. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2000; 97(1):12–17.

Commonwealth of Australia, Commonwealth response to: The hidden toll: suicide in Australia. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2010. Online Available http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/mental-pubs-c-commresp-suicide [24 Sep 2012].

Durkheim, E. Suicide: a study in sociology. New York: The Free Press; 1951.

Erikson, E. Childhood and society, second ed. New York: WW Norton; 1963.

Freud, A. The ego and the mechanisms of defence. New York: International Universities Press; 1966.

Gething, L., Papalia, D., Olds, S. Lifespan development, second Australian ed. Sydney: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

Gottesman, I., Shields, J. A critical review of recent adoption, twin and family studies of schizophrenia: behavioral genetics perspectives. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1976; 2(3):360–401.

Gottesman, I.I. Schizophrenia genesis: the origins of madness. New York: Freeman; 1991.

Gottesman, I.I. Twins: en route to QTLs for cognition. Science. 1997; 277(5318):1522–1523.

Hunter, M., Woodroofe, P. History, aetiology and symptomatology of schizophrenia. Psychiatry. 2005; 4(10):2–6.

Ivey, A., Ivey, M., Zalaquett, C. Intentional interviewing and counselling: facilitating client development in a multicultural society, seventh ed. Pacific Grove: Thompson Brooks/Cole; 2010.

Joseph, S. Humanistic and integrative therapies: the state of the art. Psychiatry. 2008; 7(5):221–224.

Kearns, H., Gardiner, M. Waiting for the motivation fairy. Nature. 2010; 472:127.

Keshavan, M., Diwadkar, V., Montrose, D., et al. Premorbid indicators and risk for schizophrenia: a selective review and update. Schizophrenia Research. 2005; 79(1):45–57.

Kring, A., Johnson, S., Davison, G., et al. Abnormal psychology, eleventh ed. New York: Wiley; 2010.

Lynch, D., Laws, K., McKenna, P. Cognitive behaviour therapy for major psychiatric disorders: does it really work? A meta-analytical review of well-controlled trials. Psychological Medicine. 2010; 4:9–24.

Maslow, A. Towards a psychology of being. New Jersey: Van Nostrand; 1968.

Navarro, V. What we mean by social determinants of health. International Journal of Health Sciences. 2009; 39(3):423–441.

New Zealand Ministry of Health. Data and statistics. Online Available http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/dataandstatistics, 2010. [24 Sep 2012].

Perls, F., Hefferline, R., Goodman, P. Gestalt therapy now: experiment and growth in the human personality. London: Pelican; 1973.

Ragsdale, S. Charlotte Malachowski Bühler, PhD (1893–1974). Online Available http://www.webster.edu/~woolflm/charlottebuhler.html, 2003. [24 Sep 2012].

Rogers, C. Client-centered therapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

Rogers, C. On becoming a person: a therapist's view of psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1961.

Rutter, M. Genes and behaviour: nature–nurture interplay explained. Boston: Blackwell; 2006.

Santrock, J. Life-span development, twelfth ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

Schaffner, K. Nature and nurture. Current Opinions in Psychiatry. 2001; 14(5):485–490.

Seligman, M. Depression and learned helplessness. In: Friedman J., Katz M., eds. The psychology of depression: theory and research. Washington: Winston-Wiley, 1974.

Seligman, M. Learned optimism. Sydney: Random House; 1994.

Seligman, M. Authentic happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press; 2004.

Seligman, M. Flourish: a new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press; 2011.

Skinner, B.F. Science and human behaviour. New York: Macmillan; 1953.

Szasz, T. The myth of mental illness. New York: Harper & Row; 1961.

Szasz, T. The case against psychiatric power. In: Barker P., Stevenson C., eds. The construction of power and authority in psychiatry. Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann, 2000.

Turkington, D., Dudley, R., Warman, D., et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: a review. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2004; 10:5–16.

Watson, J., Rayner, R. Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1920; 3(1):1–14.

World Health Organization (WHO), Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. WHO, Geneva, 2008. Online Available http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.html [24 Sep 2012].