CHAPTER 5 Health promotion, education and wellness

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to

• Explore the concepts of health and wellness in relation to both scientific data and personal experience

• Gain an overview of models of health and wellness

• Recognise the variables influencing health beliefs and practices

• Discuss the concept of health promotion and the inception of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion

• Describe the benefits of early recognition and treatment of disease

• Become familiar with the different types of health promotion programs

• Discuss the role of the nurse in health promotion

• Utilise the nursing process in health promotion

• Plan nursing interventions that support changes commensurate with the beliefs and values of the family unit

This chapter provides an overview of health and wellness as distinct from the absence of disease. It provides a focus for nurses from which to view the family as a whole, recognising the interrelationship of society, culture, the environment and family on the health beliefs and behaviours of the individual. From this perspective nurses may facilitate their client’s understanding of the interplay between social, psychological and biomedical components of their ill health, and the client’s own role in a multidisciplinary approach to their care while encouraging ownership of and responsibility for lifestyle change.

As a result of technological developments and medical and scientific achievements over the last century, the world’s population is generally living longer and healthier lives. However, major disparities in health still exist for some of the world’s population, with some countries still experiencing high morbidity and mortality rates. In recognition of these disparities in world health, the World Health Organization (WHO) works towards achieving health for all of the world’s population. Health promotion and education provide the key to minimising or eliminating disparities in world health and play fundamental roles in achieving the goals and objectives as determined by WHO. By raising the level of health awareness and providing health education for both the individual and the community, nurses play a vital role in health promotion.

Recently, as Director of Nursing, I introduced health checks in the workplace which were offered by WorkCover. As a result of this initiative, one member of staff discovered that she had high blood pressure another that she was at risk of type 2 diabetes. Fortunately, they have both been able to alter their diet and lifestyles and have managed to eliminate these medical conditions, which may otherwise have not been identified if this workplace health promotion initiative had not been undertaken.

CONCEPTS OF HEALTH AND WELLNESS

Health and wellness have many different definitions and meanings. The nurse needs to be familiar with these so that they can be taken into consideration when dealing with the client.

Health

Health is generally understood to be an absence of disease or illness. The WHO defines health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (WHO 1978). WHO’s definition of health is holistic in that it considers physical, psychological, cultural and social factors. According to WHO, ‘health depends on our ability to understand and manage the interaction between human activities and the physical and biological environment’ (WHO 1992:409). Health is a basic human right and prerequisite for social and economic development. It is a positive concept, emphasising social and personal resources, as well as physical capacities. Health is a result of many factors including shelter, food, education, social security, health and social services, income, and respect for human rights and employment. If people are given access to opportunities, knowledge, services and resources, it empowers them to ‘produce their own health’, and the health of their families, by their own actions. Health, then, may be defined according to circumstances, context and perceptions, and experiences, which may vary between individuals and between communities.

Concepts of health and wellness are based on both objective scientific measurements derived from large and varied population studies, as well as the subjective experience of individuals who describe themselves as being well or healthy. Scientific data provide information related to the determinants of health that include biological factors, health beliefs and behaviours as well as socioeconomic and environmental conditions accounting for health trends across societies and cultures. Studies of healthy people also contribute to what is referred to as indices of health, such as the body mass index (BMI). The BMI provides guidelines for healthy weight.

Such data have also provided a foundation for government-funded health screening and health promotion campaigns to raise public awareness of the interplay between lifestyle, nutrition, environmental health risks and disease. An example of health promotion programs can be seen in after school care nutrition programs that encourage children to become familiar with healthy food choices while raising parents’ awareness of the link between poor nutrition and obesity in school-age children and the rising incidence of type 1 diabetes in adolescents.

Health and wellbeing are integral elements of each person’s identity and, as such, influence actual and potential interactions with every aspect of life. WHO promotes a positive concept of health, with defining characteristics that capture the many interrelated determinants of health, as well as the importance of cultural and spiritual beliefs in health outcomes (WHO 1992). WHO has actively supported a societal shift from focusing on illness to focusing on health, recognising that personal concepts of health are derived initially from family norms and values relating to health. For example, a child whose parents openly enjoy smoking cigarettes while denying any link with respiratory disease will share that belief until such time that other events challenge those beliefs. Personal concepts of health are also shaped by geographical location, socioeconomic status and social structures, all of which influence and support family norms related to diet and lifestyle as well as healthcare access.

As children mature the values they ascribe to their health may be challenged by new information, role models outside their family of origin and by personal experience. Personal values also influence health behaviours, and a young person who prizes physical fitness may pay more attention to diet and exercise than a person in the middle years of life who attaches importance to being not ill. Older people may value health in relation to their functionality, or their ability to do things, and in enjoying life even in the presence of disease rather than focusing on the pathology of ageing.

To complete this broad overview of health and illness it is important to recognise the interrelatedness of physical and mental wellbeing as well as the interplay of both internal and external factors on each individual’s state of health. Each system and subsystem within the human body continuously exchanges information to maintain a steady state or homeostasis in the face of actual or perceived change. When these adjustment processes fail to maintain an adequate physiological balance, disease or illness may result. Responses to both internal and external challenges to homeostasis vary according to the magnitude of the challenge and the emotional readiness of each individual to cope with change. Nutritional status, age, preexisting disease and social support also influence individual responses; thus, different dimensions of wellbeing are infinitely related and linked in the socio-physical dimensions of health (see Clinical Interest Box 5.1).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.1 Health and wellness

Health is defined not only by the absence of disease but also includes the importance of psychosocial wellbeing, including the ability to make and maintain healthy relationships, to cope with daily stresses and to remain generally optimistic and motivated. This can be seen in the following example.

Mrs N, 89, has lived on her own since her husband’s death many years ago. Although she is almost blind from macular degeneration, she pursues an active lifestyle, walking her dog for at least 30 minutes every morning and participating in the administration of a day-care program for the elderly, even though many of the program participants are younger than she is.

Mrs N has evidence of rheumatoid arthritis in her hands, as well as loss of height from pronounced scoliosis of the spine, and often experiences pain from these deformities. She will often reflect on her sadness at no longer being able to knit, sew or read, as well as being annoyed with the clumsiness caused by her inflamed and disfigured finger joints.

However, while her body has a certain frailty that comes with advanced age, her voice is vibrant as she speaks animatedly to her neighbour who has come to visit. As she prepares fresh vegetables for her dinner, the smell of freshly cooked scones for the day centre pervades the kitchen. What sets Mrs N apart from many others her age is her philosophy on life—her commitment to reach beyond her physical limitations by actively contributing to her community. She has embraced the opportunities available through the use of audiotapes that substitute for letter writing, as well as being able to listen to ‘talking’ books. Mrs N maintains an interest in world affairs and keeps in touch with her daughter, grandchildren and, lately, her great grandchildren, all of whom live overseas.

Wellness

Wellness is a decision to move towards optimal health. It is the integration of body, spirit and mind. In other words, everything you do, think, feel and believe can have either a positive or a negative impact on your health. It is the lifestyle that you lead in order to achieve your optimal potential for wellbeing. Wellness is a full and balanced integration of physical, emotional, socio/cultural and spiritual components of health that includes environmental and intellectual dimensions (TAFE SA 2007:22).

MODELS OF HEALTH AND WELLNESS

A model is a symbolic representation of a complex issue such as health and provides a framework for understanding and guidance. Models are developed from research studies that identify constant factors pertaining to an issue, with recognition of links to other factors that shape or influence the outcome. Models of health can be used, for example, to predict health needs and outcomes in relation to health-related behaviours. They may also facilitate nurses’ understanding of clients’ care requirements in relation to their health beliefs and practices.

Nurses’ work has traditionally been influenced by western medical models of health that focus on the organic nature and cause of mental and physical disease, rather than on the influence of internal and external variables on the health of the whole person. This medical diagnostic-centred model is potentially disrespectful of the individual’s health beliefs and may disregard the internal and external variables that shape the social, psychological and behavioural influences on health outcomes.

The holistic health model

Contemporary nursing care delivery is guided by a holistic model of health, which encompasses a broader reference to both traditional and non-traditional therapies and acknowledges the interplay of physical, psychological and spiritual dimensions on the client’s health. This model is client centred, respecting the individual’s healthcare beliefs and actively including the client, family and carers in healthcare planning (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Ideally, this holistic model of healthcare delivery encourages clients to take responsibility for their behaviour in relation to health and illness, empowering them to assume a greater control over culturally appropriate healthcare options.

The health–illness continuum

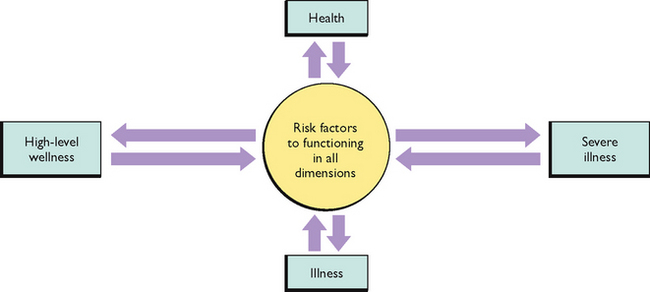

The health–illness continuum model of health assists nurses to recognise individuals’ states of health and wellness as a position on a continuum that ranges from a high level of wellness at one end to severe illness at the other (Fig 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Health–illness continuum model of health

(Redrawn from Travis JW, Ryan RS: Wellness Workbook, Berkeley CA, 1981, Ten Speed Press)

This continuum represents mental and physical functionality based on vision, hearing, speech, mobility, dexterity, cognition, emotion, pain or discomfort. The health–illness continuum model can also represent the level of individual risk for disease or illness in relation to age, socioeconomic status, cultural beliefs and geographical location. By placing high risk at one end of the continuum and low risk at the other, the comparison of age with risk of infectious childhood diseases such as mumps or rubella identifies young children as being at high risk. Population statistics identify a greater risk associated with car accidents for young people between the ages of 16 and 26 than for other age groups. Risk factors for infant mortality are related to socioeconomic status and geographical location, while the risk factors associated with tropical diseases such as malaria are much greater for people living near the equator compared with those who do not. Cultural and religious beliefs related to health practices may prohibit groups of people from the benefits of specific care options, thus increasing their associated risk factors. A continuum does not provide us with an absolute measure but, by identifying their position on the continuum, people can be encouraged to see a comparison between current and previous health states, or their position in relation to specific risk factors (Crisp & Taylor 2009). This model describes the relationship between health and illness and provides a method of identifying a client’s level of health. This model is valuable when comparing a client’s present health status with their previous level of health and for then setting nursing goals and objectives to promote a future level of health (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

The health belief model

The health belief model (Crisp & Taylor 2009) demonstrates the link between people’s beliefs about health and their health-related behaviours or health practices. Health beliefs can be defined as the concepts or ideas about health that the individual believes as true. Health practices can be defined as the activities or behaviours that the individual will engage in as a result of, or in line with, their beliefs about health. Many health practices can become unconscious habits, such as cleaning teeth before going to bed, and for most people health beliefs are grounded in family health beliefs, values and practices. Family health beliefs usually reflect the dominant societal attitudes to health at that time.

Further information or experiences may either support these beliefs or contribute to a change. This model identifies two factors that influence change in health-related behaviours: personal readiness for change, and the strength of the stimulus. Readiness for change may be related to an event such as health breakdown or a close encounter with death, or it may arise from dissatisfaction with personal states of health. The strength of the stimulus for change is directly related to the individual’s perception of personal vulnerability to death or disease and it is precisely at this time that health education is most effective in the short term. This model may be best understood through the scenario in Clinical Interest Box 5.2.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.2 Application of the health belief model

Tom is a 50-year-old married man who has noticed a change in his personal level of fitness over the last few years. He acknowledged a gradual weight gain when his clothes were no longer comfortable and he began using the lift to his office because he became breathless when climbing a flight of stairs.

Related health beliefs

Tom believes that weight gain is inevitable with advancing years because both his parents had become much heavier as they aged. Both Tom and his wife smoked cigarettes but were undeterred by the health warnings on the cigarette packets because no one in their family developed lung cancer or heart disease.

Health-related event

Tom was forced to walk up stairs to his office when the lift was out of order. He was breathless from the exertion and experienced heaviness in his chest. His secretary called an ambulance and Tom was subsequently diagnosed with a myocardial infarction.

Stimulus to change health behaviours

Tom made a good recovery but the experience had frightened him. He paid attention to the health education sessions for clients in the cardiac step-down unit and sought advice about diet, exercise and cigarette smoking.

Strength of the stimulus

Tom never forgot the pain in his chest and his fear of dying. He stopped smoking and gradually increased his level of fitness with the support of the cardiac rehabilitation team. His wife was scared Tom was going to die and supported him throughout his illness and rehabilitation. She cut back her cigarette smoking and didn’t smoke in front of Tom but was unable to ‘kick the habit’. Tom’s parents were very supportive but thought they were too old to change their health behaviours.

Barriers to changing health-related behaviours include personal and financial cost to the individual, stated or anticipated family disapproval and low expectation of personal benefit related to the intended change. By recognising the subjective nature of perceived threats to health and the influence of family and cultural beliefs about health practices, the health belief model can offer nurses a guide for client readiness to change. It also assists the nurse to identify the optimal time for health education and the probability of the individual making a commitment to change. The health belief model is one of the most widely used conceptual health promotion models and was developed to assist in understanding health behaviour. This model can be effective in developing health education strategies and can also be a useful framework for designing change strategies.

VARIABLES INFLUENCING HEALTH BELIEFS AND PRACTICES

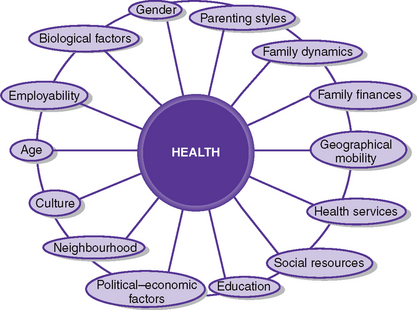

For each individual, health is a complex and inconsistent state, subject to change. The forces that influence change in health status arise from within the individual as well as the social and physical environments in which people live, the infrastructure for access to healthcare and the expectations of health that are common to that society. Internal factors include physical and intellectual development and emotional states as well as strength of character and ability to cope with change. Healthy psychological development may also be supported by spiritual beliefs and values, which bring hope and meaning to life. These internal factors cannot be separated from external factors, including socioeconomic status, cultural or family norms and values, as well as wider global influences. Figure 5.2 shows the interactions between the variety of factors that can affect health. An overview of the interrelationship of these influences on health outcomes is explored in this section.

Internal factors

Physical development

At birth a baby’s health depends initially on fetal development and gestational age, genetic makeup and, finally, a healthy birth weight. These variables are largely related to maternal health and diet, which in turn are influenced by socioeconomic status of the family as well as cultural norms. As the children grow, their health status will be influenced by exposure to disease and their immune status. Undeniably, health beliefs and behaviours play a large part in disease prevention, for example, acceptance or rejection of immunisation schedules, and housing and sanitary conditions. Diet and exercise play an important role in further biological and psychosocial development, as do the health behaviours that are modelled by family members, for example, taking a drug, resting or massaging to relieve headache. Physical development and the experience of health cannot be separated from the society in which the individual lives, the physical body being one with the psychosocial body and the forces that shape it such as gender, age and developmental level (Berman et al 2012; Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Intellectual development

For people to take responsibility for their health behaviours they must fully understand the relationship between health risks and health behaviours. Information about health can be accessed through libraries and health and medical centres, but more than ever, electronic information informs lifestyle choices. However, the ability to critically appraise this wealth of information and to make informed choices about health practices depends on many factors, for example, cognitive development, access to adequate education and family values related to academic success, positive and negative personal health experiences, lifestyle choices and spiritual and religious beliefs.

Emotional development

Adult mental health is largely influenced through appropriate parental attachments in the early years of infant life and sets the stage for the development of behavioural self-regulation. Early relationships and active social interactions have a far-reaching effect on personality development as well as the ability to form appropriate emotional relationships as an adult. Most importantly, positive emotional experiences in early childhood influence the individual’s adaptive capacities to meet the many demands of adulthood, including emotional stress and occasions of physical illness. The interrelationship of emotional and cognitive function with activation of the immune system relates to the individual’s ability to heal from both biological and psychological trauma (Berman et al 2012). The body’s physiological response to perceived stressful events is also initiated by the brain. The release of neurochemicals sets off a cascade of physiological reactions assisting well-balanced individuals to cope with a wide range of stress and anxiety without compromising their health beliefs and practices.

External factors

Socioeconomic factors

The interaction of social and economic factors on health beliefs and practices are far-reaching and include the compounding effects of social status, physical location and standard of housing; education, employment and income levels; marital status, stability of the relationship and carer responsibilities; private health insurance; and access to, and use of, healthcare and information. Levels of education influence people’s use of health-related information, while social status in the community largely influences the ways that families define health and how and when they seek medical aid, including the use of health-screening services. The effects of these factors on health is evidenced through the increased probability of people with lower levels of education and income engaging in health-risk behaviours such as smoking cigarettes, abusing alcohol or leading a sedentary lifestyle, with the associated health problems that relate to excess body weight and obesity.

Patterns of illness differ between people of different cultures and social classes and in Australia and New Zealand the health status of Indigenous Australians and Māori are typically worse than that of the general population (AIHW 2010; Ministry of Health 2011b). This is partly due to the influence of western cultures and diseases on their traditional lifestyle but is also adversely affected by a constellation of socioeconomic factors including geographic location in remote areas and access to healthcare with under-resourced and inappropriate healthcare services (McMurray & Clendon 2011).

Family health practices/social support

Family patterns, rituals and routines have a considerable influence on children’s learned behaviours in relation to health behaviour and practices and these are often perpetuated into adulthood. Family attitudes, values and behaviours set the standard for how family members care for each other, the type of diet that is provided on a regular basis and the use of exercise both as a family activity and as a health routine (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Family values also influence the use of, and compliance with, health promotion activities such as children’s immunisation schedules, age-appropriate health screening practices and conformity with road and vehicle safety regulations. Information about family health values and routines are important for nurses planning healthcare interventions or health education. The introduction or promotion of different healthcare practices must be commensurate with family values and lifestyle if they are to have a positive and lasting effect. Clinical Interest Box 5.3 lists examples of healthy lifestyle choices, and Clinical Interest Box 5.4 is an example of a family’s health beliefs.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.4 Health beliefs

I remember my grandmother and mother applying turmeric paste, which is used for cooking in many Asian cuisines, on cuts and wounds. They used to tell me it was an ancient remedy and they believed turmeric had many therapeutic values. I still use this traditional method of wound management with my children when they come home with cuts and bruises from the playground and I have found that it is the cheapest, safest and most effective antiseptic cream you can get—straight out of the pantry.

(Meera, mother of four young children)

Spiritual factors/cultural beliefs

Culture can influence how illness is experienced, how that experience is communicated to health professionals and the type of care sought (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Each culture has ideas about health, and these ideas are passed from one generation to another (Berman et al 2012). Traditional Chinese beliefs adopt a holistic view that emphasises the importance of environmental factors in increasing risk of disease. According to Chinese health beliefs, these factors influence the balance of the body’s harmony, yin and yang. These are two opposite but complementary forces and together with qi (vital energy), they control the universe and explain the relationship between people and their surroundings. Any imbalance in these two forces, or in qi, results in illness.

Spiritual and religious beliefs can affect health behaviour (Berman et al 2012). Seventh Day Adventist teaching, for example, prohibits the use of tobacco and alcohol and encourages vegetarianism. Religious coping methods such as prayer, reading of scripture, ritual meditation and talking with caregivers, ministers or clergy can have psychological, physical, spiritual and emotional benefit (Marche 2006).

Environmental factors

The environment plays a major role on health and illness. Housing, sanitation, climate, pollution of air, food and water are aspects of environmental factors (Berman et al 2012). Clean air, water and food are the most important factors affecting health, and these remain issues of major concern in the twenty-first century (AIHW 2008, in McMurray & Clendon 2011). Pollution of water, air and soil affects the health of cells. Global warming is another environmental hazard as it affects food production and the spread or development of illness or disease (Berman et al 2012).

Ill health and disease

Ill health or illness may be described as an abnormal event in which aspects of a person’s social, physical, emotional or intellectual condition are impaired (Berman et al 2012). Illness is not simply the presence of a disease process; rather, it is directly related to the total person and their environment and culture. Disease may be defined as a disturbance in structure and/or function of any aspect of a person (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Diseases may be classified according to their cause, the way in which they are acquired, or according to the body system affected. Disease is often construed to be a medical condition associated with specific signs and symptoms. It may be caused by external factors such as infectious disease, or it may be caused by internal dysfunctions, for example, autoimmune diseases. Diseases usually affect people not only physically, but also emotionally, as contracting and living with disease can alter their perspective on life, and their personality. There are four main types of disease: pathological, deficiency, hereditary and physiological.

Nursing and ill health and disease

The focus of nursing care in the twenty-first century has largely shifted from an ill-health medical model to include client-centred holistic care and health promotion, using theory and research as a basis for practice. Nursing has moved from being disease oriented to caring for the whole person with an illness, emphasising the importance of preserving and maintaining health. This approach respects the client’s perspective as valid and important and diminishes the nurse’s assumed right to ‘know for’ the client and thereby make judgments about the individual’s experience of illness.

Although illness as such is not disease, it can be understood as including the client’s experiences associated with acute or chronic illness such as pain, personal discomfort and embarrassment, fear and powerlessness. It is important for nurses to establish an understanding of the beliefs that surround a person’s illness experience by listening to the client’s stories of declining health, precipitating factors, beliefs about cause, issues of concern and expected outcomes. This places the nurse in a privileged position of confidant, educator and guide and, by valuing these dialogues, nurses can encourage clients to examine alternative solutions to their healthcare issues.

If patients have an acute or chronic illness, the experience may have left them feeling vulnerable or powerless. When patients are actively encouraged to participate in their care management, as well as to examine the implications of their diet and lifestyle on their future health outcomes, they effectively form a power-sharing partnership with the nurse. This in turn has the potential to improve their psychological wellbeing, reduce their stress and promote wellness.

IMPACT OF ACUTE AND CHRONIC ILLNESS ON CLIENT AND FAMILY

As patterns of mortality in Australasia and the western world change from the infectious epidemics of earlier centuries to long-term degenerative diseases of the present day, treatment therapies and healthcare provision have also changed. Modern technology and critical-care medicine facilitate many clients’ recovery from trauma and acute episodes of illness, but shorter hospital stays and the provision of services that support ongoing care in the home can represent a crisis not only for the client, but also for all members of the family. The effects of illness on families and clients vary in relation to the severity of the disease, the age of the client and other family members, as well as the ability of each to cope with the exigencies of treatment therapies, personal stress and changes to family dynamics (Berman et al 2012).

While today many people can look forward to a longer and generally healthier life, the structure of present-day family units has changed. It does not very frequently include members of the extended family, such as grandparents, who would have traditionally provided care for other members during periods of illness. The family unit, which now more often includes single parents or same-sex couples, or which has been remoulded through divorce and remarriage, can be defined as an interactive system with established roles and functions for each member. Changes for one family member will set off a succession of changes because of the evolving and interdependent nature of family relationships. This situation becomes more complex in the event of chronic illness, when the sick role becomes the focus of attention and other family members must incorporate elements of responsibility into their previously established roles. Family routines are changed; previously important events may be overlooked and family members may be in a state of shock, denial and/or anger when informed about the serious nature of the illness. The mood in the family may change from hope for the future to despondency and may be compounded in some situations by financial difficulties or impact on carers.

Parents of sick children often display controlling and overprotective behaviours as an expression of their anxiety, although parents of chronically ill children may have developed some level of expertise in managing their child’s care, often finding some solace and empowerment in their role. Adolescents who live with disabling conditions resulting from chronic diseases such as asthma, diabetes, cystic fibrosis or juvenile arthritis must cope not only with the demands of their illness but also with social and sexual development, completion of secondary education and entry to tertiary education or finding a position in the workforce. Just as these young people are seeking some level of independence from their family, their parents may express reluctance to loosen the ties, having shaped their lives to accommodate the demands of their illness.

Maintaining health

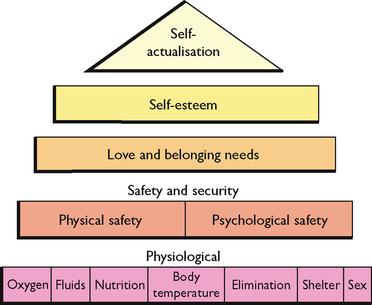

Maintaining health requires achieving a balance of all aspects of life. Factors such as age, sex, family relationships, cultural influences and economic status may have an impact on achieving that balance. Several models have been developed to provide nurses with frameworks to assist people to achieve optimal health. The earliest model was developed in the 1940s by Abraham Maslow. He believed that a person’s motivations and behaviour are formed by attempting to meet their basic needs. Maslow defined basic human needs as physiological needs, safety and security, love and belongingness, self-esteem and self-actualisation. Maslow’s ‘hierarchy of needs’ model (Fig 5.3) emphasises that some needs are more basic than others and that the more basic needs need to be met before consideration of higher needs. Maslow’s hierarchy has provided an important foundation for human services, including nursing, where it forms the basis of most nursing models.

Early recognition and detection of disease

Healthcare services recognise the need to focus on health rather than illness; therefore the emphasis is on health promotion and illness prevention at an individual and community level. Health promotion and illness prevention have become an important focus of healthcare for several reasons; for example, there are still no cures for many diseases, healthcare costs are rising rapidly, and the community is more aware of the value of health maintenance. Advancements in technology and scientific and medical achievements have led to the development of advanced diagnostic equipment. The early detection and recognition of the contributing factors that influence health and illness can prevent the spread of disease at both an individual and a community level. An example is the free breast-screening programs for women aged over 50 in Australia (45 years of age in New Zealand) to detect tumours early and significantly reduce the need for radical surgery and improve recovery rates.

HEALTH PROMOTION

Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase their control over, and to improve, their health. To reach a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing an individual or group must be able to identify and realise aspirations, satisfy needs and change or cope with the environment. Health promotion is carried out by and with people, not on or to people. Health is therefore seen as a resource of everyday life, not the objective of living. Health is a positive concept emphasising social and personal resources as well as physical capacities. Therefore, health promotion is not just the responsibility of the health sector but goes beyond healthy lifestyles to wellbeing (WHO 1986). As opposed to illness prevention activities, which aim to protect the client from actual or potential threats to health, health promotion aims to help people maintain their present level of health or increase control over, and improve, their health.

The concepts of health promotion and illness prevention are closely related (Clinical Interest Box 5.5). Leavell and Clark (1965) defined three levels of prevention: primary, secondary and tertiary.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.5 Health promotion and illness prevention

Primary health-promotion practices and illness-prevention practices aim to avoid or delay occurrence of a specific disease or disorder. Examples include:

• Maintaining ideal body weight

• Wearing seatbelts or safety helmets

• Minimal exposure to the sun, wearing hats and applying sunscreen when out of doors

Secondary health-promotion practices and illness-prevention practices consist of steps to aid early diagnosis and prompt intervention in disease, shortening the disease process. Examples include:

• Having regular Papanicolaou (Pap) smears or prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests

Tertiary health-promotion practices and illness-prevention practices consist of rehabilitation measures after the disease or disorder has been stabilised and treating existing diseases or disorders. Examples include:

Nurses focus on health promotion and illness prevention when providing healthcare, which assists clients to maintain good health and improve health, as well as providing care after illness has occurred. Health promotion activities can be passive or active. Active health promotion activities require the client to be motivated to adopt a specific health program such as giving up smoking. Passive health promotion occurs when the client benefits from the activities of others without necessarily acting themselves, such as in the fluoridation of drinking water.

A dynamic improvement in health and life expectancy has occurred in the last century in line with significant advances in technology. However, major disparities and inequalities in access to and equity in better health are recognised for different world populations. WHO was established by the United Nations in 1948 to deal with international health matters and concerns. There are 194 member countries of the World Health Assembly, which is the supreme decision-making body of WHO. This worldwide organisation agreed that ‘Governments have a responsibility for the health of their peoples, which can be fulfilled only by the provision of adequate health and social measures’ (WHO 1992). The Declaration of Alma-Ata (Health for All by the Year 2000) came about after the 1978 WHO conference. This was to be the milestone for world health. The declaration called for:

• Community participation and maximal community self-reliance

• Use of socially acceptable technology

• Health promotion and disease prevention

• Involvement of government departments other than health departments

• Cooperation between countries

• Reduction of money spent on armaments, to increase funds for primary healthcare

These principles from the Declaration of Alma-Ata provide the underpinning concepts for ‘primary healthcare’. Primary healthcare is essential care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology, made universally accessible to people and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development, in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination (WHO 1978).

Primary healthcare focuses on social justice, equity, community participation, socially acceptable and affordable technology, the provision of services on the basis of the needs of the population, health education and work to improve the root causes of ill health. It emphasises working with people to enable them to make decisions about their needs and how best to address them (McMurray & Clendon 2011). These guiding principles of primary healthcare should be applied throughout the health system and adopted by all health workers (Talbot & Verrinder 2010; Wass 2000).

To distinguish between other often misconstrued concepts of primary healthcare, and to understand exactly what primary healthcare is, Wass (2000) provides an explanation of what primary healthcare is not:

• Primary healthcare is not primary medical care or primary care. This is medical care provided for people at their first point of contact with the health system, provided in the outpatients’ section of a hospital, or by a general medical practitioner

• Primary healthcare is also not primary nursing, as this is a system of nursing in which an individual nurse takes primary responsibility for specific clients. Primary healthcare is not just community-based healthcare. The primary healthcare approach has implications throughout the entire health system

• Primary healthcare is applicable to all countries of the world, not just developing countries, and consequently cannot be referred to as simply Third World healthcare.

Primary care is not necessarily the same as primary healthcare unless it meets all of the criteria as outlined by the Declaration of Alma-Ata. In New Zealand, primary care is directed to address acute and chronic medical conditions. Primary healthcare services focus on illness prevention and health promotion activities are administered through the New Zealand Primary Health Care Strategy. In Australia, trials such as SA HealthPlus attempt to create a shift to a population-based model of care from a funding based model of care. There was a shift from an acute to a chronic illness focus with the aim of providing integrated services (Battersby et al (2005), as cited in Talbot & Verrinder 2010).

The new public health movement arose out of the recognition that ill health arises from social, biological, economic, environmental and emotional factors. Improvements in health status in the twentieth century are related to improvements in these determinants (Talbot & Verrinder 2010). Primary healthcare, health promotion and the new public health all aim to improve health.

Models of health promotion

Over the past 30 years, three key models of health have influenced health promotion: the medical, behavioural and socio-environmental. Various models of health promotion have been developed by nurses to provide conceptual frameworks for identifying a client’s health behaviour and beliefs. A client’s health beliefs may stem from many factors, including health perception, demographics and personality type. Tannahill’s model, for example, shows health promotion as being made up of three areas: prevention, health protection and health education (Downie et al 1996). Beattie’s model (1991), which is useful for charting ethical and political tensions, can be used as a planning tool. This model has four approaches to health promotion: health persuasion, personal counselling, community development and legislative action for health.

PREREQUISITES FOR HEALTH

The fundamental conditions and resources for health are peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice and equity. To work effectively, improving health requires a secure foundation in these basic prerequisites. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (Clinical Interest Box 5.6) highlights the need for health workers to be effective in advocacy, enabling and mediation to assist people in gaining greater control over their lives (WHO 1986).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.6 The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion

As a response to growing expectations for a new public health movement around the world, the first International Conference on Health Promotion was held in Ottawa, Canada in November 1986. The outcome of this conference was a charter for action to achieve ‘Health for All by the Year 2000 and Beyond’. This charter is known as the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion.

Advocacy

Good health is a major component of social, economic and personal development and an important part of quality of life. Political, economic, cultural, environmental, behavioural and biological factors can all affect our health. Health promotion aims to make these conditions favourable through advocacy for health.

Enabling

Health promotion focuses on achieving equity in health and aims to reduce differences in current health. The Ottawa charter states that ‘People cannot achieve their fullest health potential unless they are able to take control of those things which determine their health. This must apply equally to women and men’ (WHO 1986).

Mediation

The health sector alone cannot ensure the prerequisites and prospects for health. Health promotion requires coordinated action by all concerned: by governments, health and other social and economic sectors, non-governmental and voluntary organisations, local authorities, industry and the media. People are involved as individuals, families and communities. Professional and social groups and health personnel need to mediate between differing interests in society for the pursuit of health. Health promotion strategies and programs should be adapted to the local needs and possibilities of individual countries and regions to take into account differing social, cultural and economic systems.

Unlike previous public health approaches, the new public health movement recognises the broader issues of health promotion and the need for governments and health bodies to work collaboratively. It further recognises the need to increase community control and to consider the importance of people’s environments as determinants of health. Subsequent international conferences have expanded on these fundamental issues.

The Ottawa Conference was preceded by the International Conference on Primary Health Care in Alma-Ata (USSR) in 1978, and followed by conferences in Adelaide (1988), Sundsvall (1991), Jakarta (1997), Mexico (2000) and Bangkok (2005). Each conference continues to strengthen health promotion principles and practice, such as healthy public policy, supportive environments, building healthy alliances and bridging the equity gap. The 7th Global Conference on Health Promotion was held in Nairobi in 2009. Health promotion was seen in this conference to be an essential, effective approach in line with the renewal of primary healthcare as endorsed by the Executive Board of WHO. According to WHO, health promotion strategies are not limited to a specific health problem, nor to a specific set of behaviours. Rather, WHO applies the principles of, and strategies for, health promotion to a variety of population groups, risk factors, diseases, and in various settings. Health promotion and the associated efforts put into education, community development, policy, legislation and regulation are as valid for the prevention of communicable diseases, injury and violence, and mental problems, as they are for the prevention of non-communicable diseases (WHO 2009).

Australian Government policy on health activity began in the mid-1980s. In 1986 the Better Health Commission formulated Australia’s response to the goal of ‘Health for All by the Year 2000’. The Health for All Australians report (Health Targets and Implementation (Health for All) Committee 1988) represents the beginning of Australia’s commitment to health goals and targets, carried through in several subsequent documents, including Health Goals and Targets for Australian Children and Youth (Child, Adolescent and Family Health Service 1992), Goals and Targets for Australia’s Health in the Year 2000 and Beyond (Nutbeam et al 1993) and Better Health Outcomes for Australians (Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health 1994) and the National Health Priority Areas (NHPA) (AIHW nd). The National Health Priority Areas initiative was Australia’s response to the WHO’s global strategy ‘Health for All by the Year 2000’. The initial 1996 set of NHPAs included cardiovascular health, cancer control, injury prevention and control and mental health. Diabetes mellitus was added in 1997, followed by asthma in 1999, arthritis and musculoskeletal conditions in 2002 and obesity in 2008.

In New Zealand, The New Zealand Health Strategy (Ministry of Health 2000) set out principles, goals and objectives for the health system. These guided the development of the Primary Health Care Strategy (Ministry of Health 2001). With the introduction of the Primary Health Care Strategy, the New Zealand Government aimed to establish a primary healthcare structure providing comprehensive coordinated services. Priority was placed on obesity, nutrition and physical activity in the New Zealand Health Strategy, and subsequent government policies aimed at reducing obesity and improving nutrition and physical activity levels. More recently there has been the development of ‘Better, Sooner, More Convenient Health Care in the Community’, a policy dedicated to New Zealand’s primary healthcare workforce (Ministry of Health 2011a).

Determinants of health

Many factors could potentially determine our health. In 2000, WHO developed 10 social determinants of health: the social gradient, stress, early development, work, unemployment, social support, social exclusion, addiction, food and transport. Talbot and Verrinder (2010) describe a further set of determinants for health: peace, shelter, education, social security, social relations, empowerment of women, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resource use, social justice, respect for human rights and equity. All of these factors will raise or lower health and they can have a positive or negative impact on people (Brown & Edwards 2012).

Research illustrates the relationship between lower socioeconomic status and ill health (Talbot & Verrinder 2010). The health and quality of life of most Australians compares well with the rest of the world, although there are some significant differences in population subgroups. Compared with those who have social and economic advantages, disadvantaged Australians are more likely to have shorter lives; Indigenous people are generally less healthy than other Australians, die at much younger ages and have more disability and a lower quality of life; and people living in rural and remote areas tend to have higher levels of disease risk factors and illness than those in major cities (AIHW 2010).

Those things that increase our risk of ill health are known as risk factors. Examples include behaviours such as smoking or being physically inactive, or the wider influence of lower socioeconomic status. Risk factors contribute to over 30% of Australia’s total burden of death, disease and disability. Tobacco smoking is the single most preventable cause of ill health and death in Australia (AIHW 2010), with lung cancer the leading cause of cancer deaths in New Zealand (Ministry of Health 2011b). Gender is also a significant determinant of health chances. In Australia mortality rates for males are higher than those for females. Men are also less inclined to seek medical assistance. The second highest risk to health is physical inactivity, with one-third of Australians and half of all New Zealanders failing to meet recommended daily levels of physical activity (McMurray & Clendon 2011).

Ethnicity is another determinant of health. While many migrants have better health on arrival than the average Australasian because of the requirement of the immigration process, this advantage disappears the longer they have been in Australasia because of a decline in job opportunities, different health habits from their country of origin and a lack of social support (WHO 2008; AIHW 2010).

Indigenous people

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience higher infant mortality (three times higher than for other Australians) and a hospitalisation rate 50% higher than other Australians. Life expectancy for Aboriginal children born in 1998–2000 is 19 to 21 years less than for other Australians (Talbot & Verrinder 2010). In 1989 a National Aboriginal Health Strategy was produced (National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party 1989), which identified both key issues and potential solutions to some of the major Aboriginal health issues. The strategy emphasises the structural basis of Aboriginal health, recognising the link between Aboriginal health, land rights and domination of Aboriginal people by non-Aboriginal culture. Further, the strategy argues for Aboriginal community control of health services and research into issues related to Aboriginal people and their health. Although considered to be a valuable contribution, this strategy was evaluated five years after its release and was deemed to have been ineffectively implemented, possibly due to under-funding (Wass 2000).

Māori life expectancy at birth is now approximately 70.4 years for males and 75.1 years for females, which is approximately 8.3 years less than non-Māori (Ministry of Health and Statistics 2009). Māori health promotion is the process of enabling Māori to increase control over the determinants of health and to strengthen their identity as Māori, thereby improving their health and position in society (Ratima 2001). To more fully understand Māori health promotion, it is useful to refer to two models for Māori health promotion—Te Pae Mahutonga (Durie 2000) and Kia Uruuru Mai a Hauora (Ratima 2001). Together, these models describe both the breadth of Māori health promotion and its defining characteristics. The characteristics include the underlying concept of health, the purpose, values, principles, prerequisites, processes, strategies, key tasks and markers.

GOALS AND TARGETS FOR AUSTRALIA’S AND NEW ZEALAND’S HEALTH IN THE 21ST CENTURY

The areas of health targeted by Australian and New Zealand health policies focus on preventable mortality and morbidity and include:

• Sexually transmitted infections

• Maternal health problems and disorders

Focus is also on healthy lifestyles and risk factors such as:

Other targeted areas include health literacy and health skills, such as life skills and coping, safety skills and first aid, self-help and self-care, social support and promoting healthy environments such as the physical environment, transport, housing, home and community infrastructure, work and the workplace, schools and healthcare settings.

Health promotion programs include activities such as:

• Education with a view to prevention

• Promotion of food supply and proper nutrition

• Provision of an adequate supply of safe water and basic sanitation

• Provision of maternal and child healthcare, including family planning

• Prevention and control of major infectious diseases

Other health programs are designed to address and focus on the targeted areas such as healthy lifestyles and known risk factors, health skills programs and healthy environments.

The New Zealand Health Strategy (Ministry of Health 2000) attempts to integrate primary healthcare across healthcare services. In Australia, following the 20/20 summit in 2008, the Federal government has undertaken a strategy to develop a National Preventative Health Taskforce to address issues of risk factors for chronic illness. At the same time a strategy called ‘Closing the Gap in Aboriginal Health’ was implemented in which funds were allocated to address the differences in health status between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The Jakarta Declaration on Health Promotion into the 21st century

The Jakarta Declaration (WHO 1997) provides the strategies and guiding principles for health promotion to take us into the twenty-first century and builds on the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. The guiding principles are to:

• Promote social responsibility for health

• Increase investments for health development

• Consolidate and expand partnerships for health

The focus is still on primary healthcare and social justice and emphasis remains on community empowerment.

THE ROLE OF THE NURSE IN HEALTH PROMOTION

The role of the nurse in promoting health can be multi-layered. It is important for all nurses to work within the confines of their scope of training and practice. For some nurses, health promotion may become simply a way of working that is client centred and holistic. To others it may be a set of more defined activities, including assessing health needs and providing information. An awareness of public health issues and factors that influence health status is an expectation of nurses.

Nurses can make a contribution to the health and social wellbeing of their individual clients by:

• Recognising there is a role for the nurse in the promotion of health and self-care

• Participating in providing health promotion interventions

• Being aware of the key health and social factors to be considered when carrying out an assessment of individual needs

• Being aware of the contributions of other professionals to assessment and intervention.

Nurses can adopt a positive perspective to health promotion when nursing in the community by:

• Recognising that clients are individuals within the group with specific needs

• Participating in health promotion activities

• Maintaining cultural awareness and sensitivity

• Learning and gaining knowledge about the community

• Networking and building on resources and partnerships

• Developing and improving personal skills required for practice.

If public health or health promotion is to be a central concept in nurses’ work, then nurses’ role-perception, skills, knowledge and attitude to health promotion will have a vital impact on the success or failure of health promotion activities.

Health education

Health education is linked to health promotion because the purpose of health education is to promote the presence of conditions that assist people in creating health, that is, to enhance conditions for personal and community health (Brown & Edwards 2012). Both registered and enrolled nurses play a pivotal role in health promotion, health maintenance and prevention of illness through provision of evidence-based information and education to individuals, groups and communities. This requires knowledge of resources available within the community and healthcare sectors to facilitate care for individuals and groups and the skills to communicate and educate. Health education can be defined as ‘any combination of learning experiences designed to facilitate voluntary actions conducive to health’ (Green & Kreuter 2005). Health education can be any planned educational intervention people can voluntarily take that aims to look after their health or the health of others.

Ewles and Simnett (2010) describe the dimensions of health education as:

• Concerned with the whole person, encompassing physical, mental, social, emotional, spiritual and societal aspects

• A lifelong process from birth to death, helping people to change and adapt at all stages

• Concerned with people at all points of health and illness, from the completely healthy to the chronically sick and handicapped, to maximise each person’s potential for healthy living

• Directed towards individuals, families, groups and whole communities

• Concerned with helping people to help themselves and with helping people to work towards creating healthier conditions for everybody ‘making healthy choices easier choices’

• Involved in formal and informal teaching and learning using a variety of methods

• Concerned with a range of goals, including giving information, attitude change, behaviour change and social change.

Health education involves working with individuals, communities and society and may be guided by the principles of primary healthcare. If nurses are to influence the health of individuals and communities, they need to be clear about what factors contribute to people’s health and ill health. There is also a role for the individual to take responsibility for their own health, and a clear role for communities and government in tackling the root causes of ill health:

The prerequisites and prospects for health cannot be ensured by the health sector alone. More importantly, health promotion demands coordinated action by all concerned: by governments, by health and other social and economic sectors, by non-governmental and voluntary organisations, by local authorities, by industry and by the media. People in all walks of life are involved as individuals, families and countries. Professional and social groups and health personnel have a major responsibility to mediate between differing interests in society for the pursuit of health (WHO 1986).

Understanding how people report health problems or adopt particular health behaviours is a first step to planning for health improvement. The nurse needs to consider how and to what extent they can involve their clients in planning their own healthcare. Nurses may be involved in:

• Advice and information giving

• Formal and informal education and training

• Supporting people and helping people understand their condition or diagnosis

• Policy development and contributing to health improvement programs

Whether working with groups or individuals, certain skills are required to enable the nurse to facilitate health promotion and education. Nurses need to be clear and unambiguous. Nurses need to be non-judgmental, updated with current knowledge and informed of scope of practice, and need to try to attain an understanding of the client’s concerns and position. Effective communication skills such as using open-ended questions, listening, recognising any cultural implications, assessing body language, and concise history taking and documentation will facilitate this process. When educational advice is being offered the nurse needs to check whether the client understands both the message and the language. Written material may support the interpersonal communication. The nurse often needs to be aware of other factors, such as the views of significant people in the client’s life and the individual’s own self-esteem that could influence the communication process. Establishing trust and rapport and having interpersonal skills will ensure effective communication (see Ch 6).

The challenge for nurses is how and when to provide health education information. If a client has specific learning needs about health promotion, risk reduction or management of a health problem, it is useful to develop and implement a teaching plan with the client. A teaching plan includes assessment of the client’s ability, need and readiness to learn, with identification of problems that can be resolved with teaching. The nurse then determines objectives with the client, delivers educational interventions and evaluates the effectiveness of the teaching. Clinical Interest Box 5.7 lists the principles to guide effective teaching and learning.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.7 Principles to guide effective teaching and learning

(Talbot & Verrinder 2010, as modified in Brown & Edwards 2012)

There are some stressors that detract from the effectiveness of the teaching effort. The stressors, including the strategies to help manage or overcome them, are outlined in Clinical Interest Box 5.8.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.8 Strategies to help manage or overcome nurse–teacher stressors

| Stressor | Approaches |

|---|---|

| Lack of time | Preplan. Set realistic goals. Use time with patient effciently, using all possible opportunities for teaching, such as when bathing or changing a dressing. Break teaching and practice into small time periods. Advocate for time for patient teaching. Carefully document what was taught and the time spent teaching in order to emphasise that it is a primary role of nursing and that it takes time. |

| Lack of knowledge | Broaden knowledge base. Read, study, ask questions. Screen teaching materials, participate in other teaching sessions, observe more experienced nurse–teachers, attend classes. |

| Disagreement with patient | Establish agreed-on, written goals. Develop a plan and discuss with patient before teaching begins. Introduce a role model to help illustrate therapeutic expectations. Enlist the aid of family and significant others. Revise expectations; learn to be satisfied with small achievements. |

| Powerlessness, frustration | Recognise personal reaction to stress. Develop a support system. Rely on friends and family for positive encouragement. Network with other nurses, health professionals and community leaders to change the situation. Become proactive in legislative processes affecting healthcare delivery. |

Indigenous health education/promotion

In the Northern Territory, staffing arrangements for delivery of health services in communities vary from place to place. In general, Aboriginal health workers (AHWs) and remote area nurses (RANs) are the full-time healthcare providers. In many communities that do not have resident nursing or medical staff, AHWs provide the primary healthcare services.

In Indigenous settings in Australia, other resident members of the multidisciplinary team may include:

• Community-based workers such as Aboriginal health workers, community nutrition workers and environmental health workers

• Support staff such as drivers, cleaners, liaison and administrative officers

Non-resident members of the multidisciplinary team may include:

• Members of a mobile nursing team

• Dentists and other allied health professionals (Northern Territory 2007).

The title ‘Aboriginal health worker’ refers to an Aboriginal person who has undertaken specific education and training. They are recognised as a professional group and are required to be registered. Community health teams also work with traditional healers who are respected for their knowledge of traditional medicines and healing techniques. Many people will choose to use a combination of traditional healing methods and western medicine. It is essential that all members of the multidisciplinary team work together to provide a comprehensive and responsive primary health service to the community (see Clinical Scenario Box 5.1).

Clinical Scenario Box 5.1

Taking the message to the people—Well Men’s Checkups

This case study shows how health promotion officers worked closely with AHWs to develop a project for Well Men’s Checkups in East Arnhem Land. The project aimed to raise awareness of health issues and to encourage them to make lifestyle changes to improve their health. The project team approached community football teams to talk about fitness and winning games. They used a mix of strategies, including screening followed by brief interventions, media for group and community education and incentives.

Men, especially Aboriginal men, rarely go the health centre when they are sick, let alone when they are healthy. They wait until a problem becomes unbearable before they go to the health centre. Five key strategies/concepts were included in the design of the Well Men’s Checkups.

The health centre was taken to the men. Tests such as blood pressure, height, weight, blood sugar levels, cholesterol, haemoglobin, sweat loss and peak flow were undertaken. The National Heart Foundation‘s healthy heart assessment was modified to include information on smoking, dehydration and drinking.

Health education was integrated into their group activities such as at football settings.

Messages were made relevant to the men and their activities; messages such as how to improve players’ chances of winning, by getting fitter, stronger, healthier and smarter. Discussions with players included the importance of water and maintaining hydration. How smoking reduces the lungs capacity to absorb oxygen, the detrimental effects of drinking kava or alcohol the night before playing football and the positive benefits of eating a high carbohydrate meal before a game, to increase energy levels.

Healthy lifestyle role models were used to provide inspiration to younger men. A local football role model who plays Aussie Rules Football and speaks the same language was identified. He visited schools and football teams to talk about healthy lifestyles.

Finally, incentives were provided for men to attend Well Men’s Checkups: barbecues were held at the health centre after the men’s checkups.

(Smith and King 1998:69–71 cited in Northern Territory Department of Health 2007)

THE NURSING PROCESS IN HEALTH PROMOTION AND HEALTH EDUCATION

Essentially, the nursing process is a series of planned steps that produce a particular result. Specifically, the nursing process is a modified scientific method of systematic problem solving. In simple terms the nursing process is a method used to assess, plan, deliver and evaluate nursing care. The process of nursing, or scientific method of problem solving, remains the same whether the nursing care provided is a simple measure or a sequence of complicated nursing activities, and it can be adapted to individuals or communities. For a more detailed account of the components of the nursing process see Chapter 15.

It is essential to revise and update any plan of care continually to meet a client’s changing needs. By using the nursing process each individual’s specific needs are addressed, any problems are identified and a care plan is developed and implemented to meet those needs. The effectiveness of any care given is continuously evaluated in terms of the individual’s needs.

The nursing process provides an ideal framework to achieve health promotion and education for individual clients as well as groups or communities. The overall objectives for health promotion activities can be varied to:

• Include the prevention of disease

• Ensure that people are well informed and able to make choices

• Help people acquire skills and confidence to take greater control over the factors influencing their health

• Change policies and environments to facilitate healthy choices

• Address the determinants of health, such as poverty, housing and community life.

During the assessment phase of a community’s needs the principles of the nursing process remain the same. During data collection there must be a recognition that there may be many stakeholders, and research may need to be undertaken to obtain a community profile which takes into account the environment, policy, available services and resources, housing, finances and perhaps cultural considerations. Key questions to ask during the assessment phase are included in Clinical Interest Box 5.9.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.9 Assessment of characteristics that affect client teaching

Characteristics and key questions

• What are the patient’s age and sex?

• Is the patient fatigued? In pain?

• What is the primary diagnosis?

• Are there additional diagnoses?

• What is the patient’s current mental status?

• What is the patient’s hearing ability? Visual ability? Motor ability?

• What drugs does the patient take? Do they affect learning?

• Does the patient appear anxious, afraid, depressed, defensive?

• What is the patient’s present or past occupation?

• How does the patient describe their financial status?

• What is the patient’s educational experience and reading ability?

• What is the patient’s living arrangement?

• Does the patient have family or close friends?

• What are the patient’s beliefs regarding their illness or treatment?

• What is the patient’s cultural/ethnic identity?

• Is proposed teaching consistent with the patient’s cultural values?

• What does the patient already know?

• What does the patient think is most important to learn first?

• What prior learning experiences establish a frame of reference for current learning needs?

• What has the patient’s healthcare provider told the patient about the health problem?

• Is the patient ready to change behaviour or learn?

• Can the patient identify behaviours/habits that would make the problem better or worse?

• How does the patient learn best? Through reading, listening, doing things?

• In what kind of environment does the patient learn best? Formal classroom? Informal setting, such as home or office? Alone or among peers?

(Brown & Edwards 2012:55)

After collecting the data the nurse is able to identify the problem or areas of need and is then able to make a nursing assessment based on these findings. For example, in Clinical Interest Box 5.10 the nurse may make the assessment that Mary does not understand the implications of her current dietary habits and the need to make some changes. Once this has been determined the nurse is then able to plan the care needed for Mary to optimise activities to ensure health promotion.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.10 Subjective and objective assessment

Mary, 52, has recently been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus. She states, ‘I have always loved my food—in many ways it is my only enjoyment in life and now my doctor says I have to give up all the things I love to eat. I am finding it just too hard on the diet he has given me and I think I’ll just give up.’

The nurse observes that Mary does not appear to have altered her lifestyle, as she eats constantly, and there are several chocolate wrappers on the bench.

Health promotion should start from the existing knowledge and beliefs of the client. To plan the individual care needed for Mary and to begin the nursing process, it will be helpful for the nurse to first determine Mary’s health beliefs and her understanding of the diagnosis she has been given. This will require building up trust and obtaining a detailed social and medical history. This phase of the nursing process is the assessment phase and basically requires the gathering of subjective and objective data.

Subjective data are the client’s, or other significant person’s, perceptions, ideas and sensations about a health problem; for example, Mary has stated that she is finding it too hard and wants to give up. Objective data are the information observed or measured by the nurse; for example, the nurse has observed that Mary does not appear to have altered her lifestyle, she eats constantly and there are several chocolate wrappers on the bench.

Planning the care for Mary is the next phase. Planning involves setting goals, establishing priorities and determining nursing interventions to achieve the goals. This will require determining specific interventions aimed at achieving the ultimate goal for health promotion. There may be several levels of intervention, including individual one-on-one medical officer–client counselling on dietary changes, through to specialist diabetes education services. Some important questions to consider are:

• Have the issues clearly been defined?

• Who are the key stakeholders?

• Are the goals that have been set achievable and realistic?

The principles of the nursing process can again be adapted during the planning phase of health promotion activities at the community level. The above questions will provide a guide for the nurse and practitioner to ensure that objectives and aims of the program are being met.

Implementation means putting the nursing plan into action (nursing interventions); it is the actual performance of the activities that have been selected to help the client achieve the set goals. The client’s needs (either the individual or the community) are reassessed continuously during the implementation stage so that any new needs can be identified and the nursing plan modified or adapted. Techniques to enhance the teaching process with adults are presented in Clinical Interest Box 5.11.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 5.11 Techniques to enhance client learning

• Keep the physical environment relaxed and non-threatening.

• Maintain a respectful, warm and enthusiastic attitude.

• Let the patient’s expressed needs direct what information is provided.

• Focus on ‘must-know’ information, saving ‘nice-to-know’ information if time allows.

• Involve the patient and family in the process; emphasise active participation.

• Be aware of and take into consideration the patient’s previous experiences.

• Emphasise the relevance of the information to the patient’s lifestyle and suggest how it may provide an immediate solution to a problem.

• Schedule and pace learning experiences according to the patient’s needs and abilities.

• Individualise the teaching plan, even if standardised plans are used.

• Emphasise helping the patient to learn and not just transmitting subject matter.

• Review written materials with the patient.

• Remember that simple is best.

• Affirm progress with rewards valued by the patient to reinforce desired behaviours.

(Brown & Edwards 2012:60)

After the planned nursing interventions have been implemented, the nurse must then evaluate the results to determine whether the interventions were effective. Evaluation is the process of determining the extent to which the set goals or objectives have been achieved, and enables the nurse to monitor the effectiveness of the care plan. Whether the plan was a success or not is determined by comparing the client’s response to the nursing interventions within the set goals and set time frame. Evaluation also enables the nurse or practitioner to identify any new healthcare problems experienced by the individual client or the community.

Summary