CHAPTER 11 Growth and development: Late childhood through to adolescence

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to

• Describe the physical changes that occur at puberty

• Discuss the changes that occur during adolescence

• Discuss factors influencing the growth and development of the adolescent

• Identify the role that ‘others’ have during adolescence (peers, family and friends)

• Plan health promotion activities for a group of adolescents

Adolescence is the transitional stage between being a child and becoming an adult. For the child it is a time marked with many changes, from the most obvious physical ones to the more intrinsic cognitive, emotional and attitudinal changes. It is a time that is packed with milestones and incorporates many rites of passage. Although there are many guides to providing care for the adolescent, the rates of change for the child can vary considerably, so that each adolescent must be cared for individually and according to the stage that they are at. This chapter takes a holistic look at the preadolescent and the adolescent and helps guide the reader through the often complex route between being a child and developing into an adult. While this chapter discusses both the preadolescent and the adolescent experiences, the use of the term adolescent often encompasses all stages of adolescence.

An understanding of preadolescent and adolescent development is essential for nurses in their daily practice. This is the period in the life span where the individual, previously reliant on parents and carers for values and identity, becomes independent and, in this move towards independence, attempts to create a new and personal identity. It is a time when group identity is vital, often a time of experimentation with self-image, and a time to question family values and beliefs. It is a period of rapid and complex changes. This chapter highlights the growth and development of the adolescent and helps the nurse to understand how to use this knowledge to provide optimal nursing care for the adolescent when hospitalised or treated within the community.

My mother found my packet of ‘the pill’ and she is really giving me a hard time. She thinks that I will end up pregnant or will catch some deadly disease. Why doesn’t she understand that I know what I am doing? You can’t get away from all the stuff they push at you about pregnancy and AIDS. It’s at school, on the TV, on the internet. Gee, there is even a mention of safe sex in an ad on my Facebook page! One of my friends got pregnant and had to have a termination; someone else I know had to go to the sex clinic for tests and be treated for Chlamydia. There is no way I am going down those tracks. I am sure that I know a lot more than my mother does about these things. I wonder what she would say if she knew I carried a packet of condoms in my purse? I bet that would cause a fuss!

I was horrified when I found her packet of ‘the pill’. I just want to make sure she knows what she is doing, but she just will not talk to me about it. She’s a bright kid and we have great plans for her going to university and getting a good career. It would be dreadful if she got pregnant to some dreadful boy and ended up being a single mum on a pension for the rest of her life. Plus the risk of her catching something like AIDS is just so frightening. I wish I knew what to do.

PREADOLESCENCE

The transitional period between childhood and adolescence is referred to as preadolescence. However, it may also be referred to as late childhood, early adolescence or pubescence. Preadolescence is the period of about 2 years before puberty when the individual is developing preliminary physical changes that herald sexual maturity. Children during this period of time are often popularly referred to as tweenies or tweenagers, both newly coined terms that have only recently entered the English language. They are heavily targeted by advertisers as children of this age represent an important demographic. Often because they have their own purchasing power, they influence their parents’ buying decisions and they are the adult consumers of the future.

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE PREADOLESCENT

Physical development

Preadolescence refers to the beginning of the second skeletal growth spurt, when physical changes such as the development of female breasts and pubic hair also begin. These physical changes occur about 2 years earlier in girls than boys (Tortora & Derricksen 2008). The bones begin to lengthen and broaden. More in-depth descriptions of these changes are included in this chapter under the heading ‘Physical development’ in the section on adolescence below.

Cognitive development

Cognition is involved with thinking; perception, language, learning, memory and problem solving. According to the theories of the French psychologist Piaget, the preadolescent is in what is termed ‘the concrete operational stage’ of thinking (Atherton 2011). In this stage children think logically as long as they have the object of their thoughts physically present to manipulate. It is difficult for them to understand theories or abstract concepts.

Emotional development

The preadolescent is better able to describe their feelings than the younger child, especially about developmental changes they are experiencing. They become better at problem solving and achieving their goals. Some experience mood swings, which develop from the same hormones that contribute to physical changes. They may feel happy one minute and irritable or sad the next. Their feelings may be overpowering. The preadolescent may also give in to impulses, as the parts of the brain that are involved in impulse control have not yet developed fully.

Psychosocial development

In the preadolescent stage children become more social and their behavioural patterns become much less predictable. Included in this stage are experimentation with makeup by girls and the interest in music and performers that are popular with older adolescents. Typically they have same-sex friends and tend to spend more time with their friends than with their families. Preadolescents often develop friendships with adults other than their parents and use these relationships to gather information about adults. They are no longer totally egocentric and begin to see the importance of others within their social environments.

Sexual development

During this time most children experience some of the changes of puberty. As their bodies begin to change they tend to develop a natural modesty. They are frequently curious about sex and, provided that there is an environment where sex can be spoken about comfortably, they are likely to ask many questions. Sometimes when children are in hospital and curious about their bodies they ask questions of nurses they trust. This may be an indication that information relating to sexuality or sexual matters is wanted. It is advisable for the nurse to find out what knowledge the child already has to avoid giving inappropriate answers (Carpenito-Moyet 2006). (See Clinical Scenario Box 11.1.)

Clinical Scenario Box 11.1

Sarah is an 11-year-old girl you are caring for following an appendicectomy in the paediatric surgical ward. When you go to get her out of bed and take her to the bathroom, you notice that she is quite nervous about moving from under the covers and allowing you to touch or see the area around her wound site. As the RN had already assessed her pain levels and had administered her analgesia, you believe that her nervousness is not from fear or pain but may be caused by something else. Knowing that you need to build trust with Sarah before she will share with you her concerns, you stop trying to make her get out of bed and quietly ask her what the matter is. Sarah shares with you that she does not have any underwear on and that if you look at the wound site, then you will see her ‘privates’. She was also very worried that when she got out of bed and walked to the toilet others would also see she had no underwear on. The natural modesty of the adolescent had made her very uncomfortable with being partly undressed in the presence of others. You find a loose pair of pants and help her put them on before progressing with her care. This time Sarah is only too happy to allow you to view the wound site, get out of bed and mobilise to the toilet.

ADOLESCENCE

Adolescence is the period of development from age 12 to 20 and is the stage that marks the transition from childhood to adulthood (Mitchell & Ziegler 2007). Adolescence is a stage of development characterised by sudden physical changes and social and emotional maturing. It begins with the gradual appearance of secondary sex characteristics and ends with the cessation of body growth.

The term ‘adolescent’ usually refers to psychological maturation of the person, whereas puberty refers to the point at which sexual maturity is achieved and reproduction becomes possible. Puberty mainly refers to the maturational, hormonal and growth process that occurs when the reproductive organs begin to function and the secondary sex characteristics develop.

Adolescence is often described in three distinct sub-phases: early adolescence (11–14 years), middle adolescence (15–17 years) and late adolescence (18–20 years).

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE ADOLESCENT

Physical development

The physical development and changes of early adolescence (puberty) are primarily the result of hormonal activity with the sequence of pubertal growth changes the same in most individuals (Sigelman & Rider 2011). (See Tables 11.1 and 11.2.)

Table 11.1 Usual sequence of maturational changes in adolescence

| Boys | Girls |

|---|---|

| Skeletal growth spurt | Skeletal growth spurt |

| Enlargement of testes and scrotal sac | Beginning of breast development |

| Appearance of pubic hair | Appearance of pubic hair |

| Changes in larynx and voice | Menarche |

| Enlargement of penis and prostate gland | Ovulation and completion of breast growth |

| Nocturnal emissions | Appearance of axillary hair |

| Growth of downy facial hair | Widening of pelvis, deposition of body fat |

| Appearance of axillary hair | Abrupt decrease of linear growth |

| Increase in shoulder width | |

| Deepening of voice, appearance of coarse facial hair | |

| Abrupt decrease of linear growth |

Table 11.2 Growth and development during adolescence

| Early adolescence (11–14 years) | Middle adolescence (14–17 years) | Late adolescence (17–20 years) |

|---|---|---|

| Growth | ||

| Cognition | ||

| Identity | ||

| Relationships with parents | ||

| Relationships with peers | ||

| Sexuality | ||

| Psychological health | ||

Physical changes occur rapidly in both males and females. Physical distinctions between boys and girls are determined on the basis of distinguishing characteristics: primary sex characteristics are the internal and external organs that carry out reproductive functions (ovaries, breasts, penis, uterus); secondary sex characteristics play no direct part in reproduction but are the changes that occur in the body as a result of the hormonal change (development of facial and pubic hair, changes in voice, fat deposits). Secondary sex characteristics externally differentiate males from females.

The main physical changes are:

• Increased growth rate of the skeleton and muscles

• Alteration in the distribution of muscle and fat

• Gender-specific changes, such as changes in shoulder and hip width

• Development of the reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics.

Height and weight usually increase during the prepubertal growth spurt. The final 20% to 25% of height is achieved during puberty, with most of this growth occurring in a 24–36 month period. For girls this usually begins between 8 and 14 years of age. Weight increases by 7–25 kg and height increases by 5–20 cm. Growth in height usually stops 2–2.5 years after menarche in girls. For males this growth spurt occurs between 10 and 16 years of age. Height increases by 10–30 cm and weight increases by 7–30 kg. Growth in length of the limbs and neck precedes growth in other areas. Increases in hip and chest width take place in a few months, followed by an increase in shoulder width several months later (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Growth in height usually stops at age 18–20 in boys. The individual often appears awkward and clumsy and the sequence of changes is responsible for the long-legged gawky appearance that is often seen. These changes require the adolescent to adjust their perception of their self in space as well as accepting a new body image. Fat becomes redistributed into adult proportions as height and mass increase, and the adolescent gradually assumes an adult appearance. Adolescents who are concerned about physical changes that make them different from their peers should be reassured by the nurse about normal growth curves and that their own growth patterns are normal.

An increase in the secretion of sebum occurs from the skin and frequently results in acne. This development can have significant effects on how the adolescent views their physical image. (See Fig 11.1.)

Hormonal changes of puberty

Hormonal production is controlled by the anterior pituitary gland, which is in turn stimulated by the hypothalamus. The stimulation of the anterior pituitary results in the release of the gonadotrophic hormones that stimulate the gonads. As a result of this stimulation, testicular cells produce testosterone and ovarian cells produce oestrogen. These hormones contribute to the development of secondary sex characteristics and play an essential role in reproduction. The changing concentration of these hormones is also linked to problems of adolescence, such as body odour and acne.

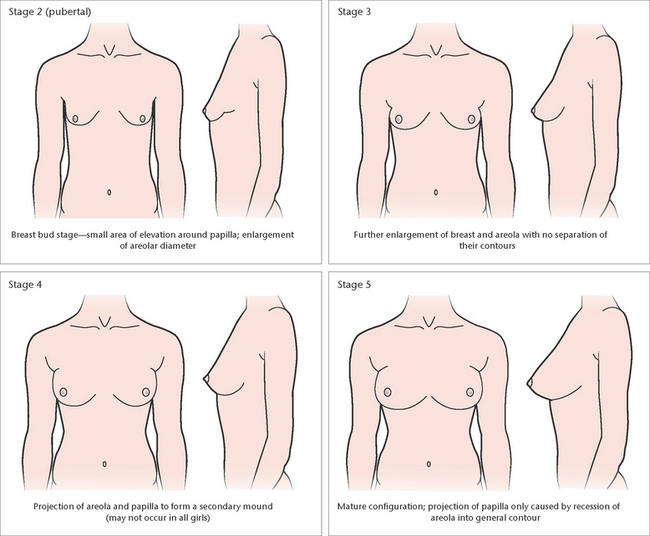

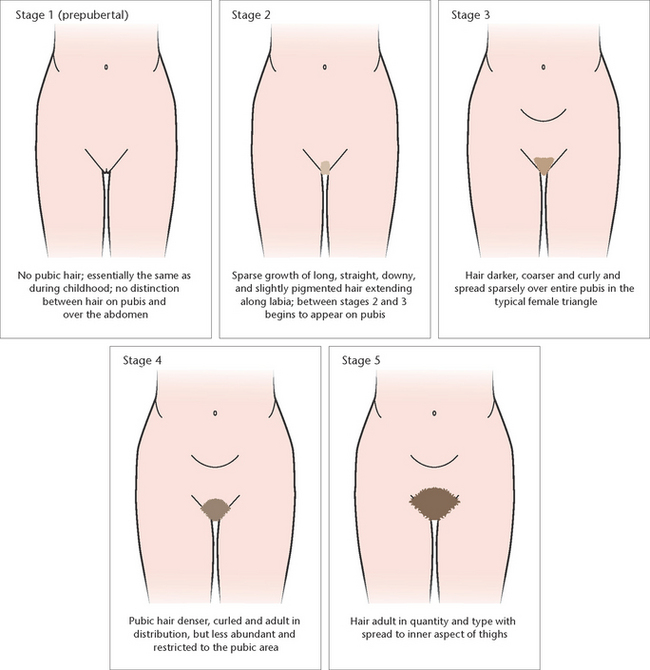

Sexual maturation in girls

The initial indication of puberty in most girls is the appearance of breast buds. Breasts begin to develop from about age 10 (development continues until about age 17). (See Fig 11.2.) About 2–6 months later, growth of pubic hair on the mons pubis begins. (See Fig 11.3.) The initial appearance of menstruation (menarche) occurs about 2 years after the first pubescent changes. The normal age range of menarche is 10.5–15 years, with ovulation usually beginning 6–14 months after menarche.

Figure 11.2 Development of breasts in girls. Stage 1 (prepubertal elevation of papillae only) not shown

(Adapted from Hockenberry 2005 [Modified from Marshall WA, Tanner JM: Arch Dis Child 44:291, 1969; Daniel WA, Paulshock BZ: A Physician’s guide to sexual maturity, Patient Care May 13, 122–124, 1979])

Figure 11.3 Growth of pubic hair in girls

(Adapted from Hockenberry 2005 [Modified from Marshall WA, Tanner JM: Arch Dis Child 44:291, 1969; Daniel WA, Paulshock BZ: A Physician’s guide to sexual maturity, Patient Care May 13, 122–124, 1979])

Concerns about pubertal delay in girls should be considered if breasts have not started to develop by age 13 or if menarche has not occurred within 4 years of the onset of breast development (Sigelman & Rider 2011). It is important to remember that racial origin and environmental issues can contribute to when puberty begins. Girls from some genetic backgrounds will experience earlier menarche than girls from others. Similarly, girls with nutritional problems such as anorexia or those having to keep a minimal body weight for some activities such as dancing, modelling and gymnastics may also experience delayed menarche. The body requires a set level of fat deposits before menarche can be initiated.

The commencement of menstruation is often seen as a rite of passage in many cultures and is frequently heralded with celebrations. In mainstream Australasian and North American culture this time is not celebrated overtly. However in other cultures it is celebrated by ritual bathing, specific ceremonies or the wearing of special clothing. In some Indigenous communities the practice of female circumcision is still undertaken to celebrate and mark this rite of passage.

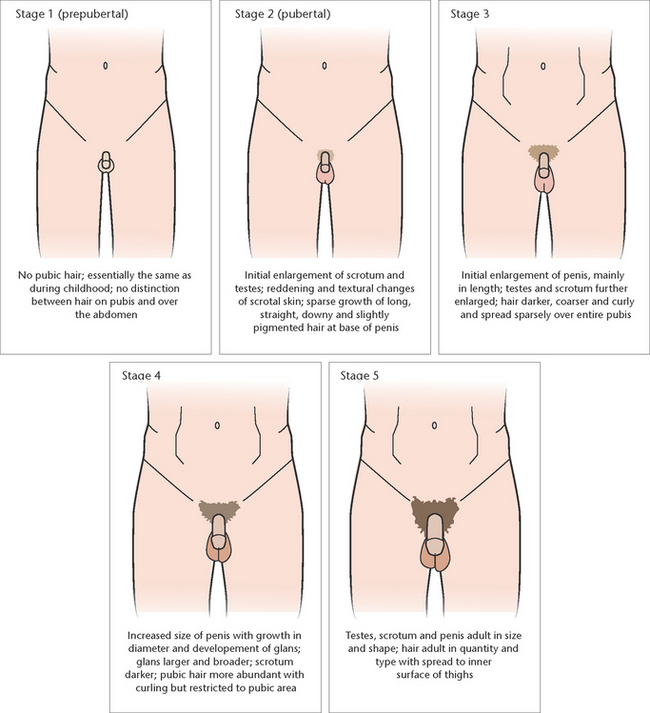

Sexual maturation in boys

Testicular enlargement, accompanied by thinning, reddening and increased looseness of the scrotum, is the first pubescent change in boys and usually occurs between age 9.5 and 14. Penile enlargement begins, with continuing testicular enlargement and growth of pubic hair. (See Fig 11.4.) Facial hair may develop along with early voice changes. Temporary breast enlargement (gynaecomastia) and tenderness are common during mid-puberty. This breast enlargement usually disappears within 2 years. Height and weight growth occur towards the end of mid-puberty. Nocturnal emissions of seminal fluid are an indication of puberty in the male and occur spontaneously and periodically during sleep. In late puberty the testicles and penis enlarge, and the voice deepens. Axillary hair develops and facial hair extends to cover the neck. During this time the opening of the foreskin in non-circumcised boys becomes larger and enables the foreskin to be retracted to below the head of the glans.

Figure 11.4 Developmental stages of secondary sex characteristics and genital development in boys

(Adapted from Hockenberry 2005 [Modified from Marshall WA, Tanner JM: Arch Dis Child 44:291, 1969; Daniel WA, Paulshock BZ: A Physician’s guide to sexual maturity, Patient Care May 13, 122–124, 1979])

Boys may be considered to have pubertal delay if there is no enlargement of the testes or scrotal changes by age 13.5–14 or if genital growth is not complete 4 years after enlargement of the testicles.

In some cultures sexual maturation in boys is celebrated by routine circumcision or the undertaking of specific ceremonies. These ceremonies are aimed at initiating the boy into manhood. In mainstream Australasian and North American cultures no specific rite of passage is undertaken. Rites of passage for boys are more frequently celebrated at the attaining of a specific age rather than on the attaining of puberty. (See Clinical Interest Box 11.1.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 11.1 Rites of passage

Achieving sexual maturity is often celebrated as a rite of passage in some cultures. These ritual events mark the passage from child to adult. Some of these coming of age traditions include:

The physical changes that occur during adolescence are rapid and dramatic and play a significant role in psychosocial development. By understanding these changes you are better able to plan appropriate nursing care and to reassure and educate adolescents about their body care needs. The timing of these physical changes depends on factors such as heredity and nutrition and whether the adolescent is a boy or girl. The sequence of growth changes (Tables 11.1 and 11.2) is the same in most individuals (Sigelman & Rider 2011).

Physiological needs

The strength and size of the heart and systolic blood pressure and blood volume increase during puberty. The pulse rate and basal heat production decrease. Boys have a higher blood volume than girls, which may be related to boys having a greater muscle mass. All formed elements of the body reach adult levels. Respiratory volume and vital capacity are increased, but respiratory rate and the basal metabolic rate decrease. As a result of increased strength and size of muscles and increased cardiac, respiratory and cardiac functioning, physiological responses to exercise change dramatically.

Nutritional needs

During adolescence nutritional needs are significantly increased. As the person goes through this time of accelerated physical and emotional development, the body’s metabolic rate increases, which intensifies the body’s nutritional needs. There is no other time in life except during pregnancy and lactation that nutritional requirements are at this maximum. Both boys and girls are often constantly hungry and may have to eat frequently to meet their needs. Boys may even have to consume up to 16 000 kilojoules per day simply to avoid losing weight. Increased protein, fibre, calcium, iron and phosphorus especially are required to fuel the extra demands of the developing body. The adolescent who does not meet these needs is at high risk of compromising both psychomotor and cognitive development (Murray & Zentner 2009). Conditions such as malnutrition and anorexia are especially harmful at this stage. Chapter 28 of this text provides you with more information about meeting the nutritional needs of the individual.

Cognitive development

Adolescents are capable of using deductive reasoning and abstract thinking and can consider the logic of a problem. According to Piaget, this stage, known as the period of formal operations, is the highest level of intellectual development. Being able to think logically about role behaviours enables adolescents to develop their own thoughts and means of expressing their identity. Intellectual development continues through formal education and the pursuit of personal interests (Atherton 2011). Without an appropriate educational environment, individuals may not reach this stage. The teenager can think abstractly and is no longer restricted to the real and actual, but can deal with the hypothetical. Adolescents are able to manipulate more than two different variables at one time. They think about what might be, whereas primary school-age children only think about what is. This allows adolescents to have more skill and insight when playing board games or video games, for example.

By mid-adolescence, cognition develops an introspective quality. At this stage adolescents wonder about what others think of them and increasingly imagine the thoughts of others. They question society and its values and, although they have the ability to think as well as an adult, they do not have the experiences that an adult has on which to build. They can think about the consequences of their actions and can detect logical consistency or inconsistency in a set of statements or actions (Crisp & Taylor 2009). For example, they will question a parent who swears but tries to persuade the adolescent not to use bad language.

Language development is relatively complete by adolescence, although vocabulary continues to expand. The main focus becomes the development of communication skills that can be employed effectively in various situations. Adolescents need to share thoughts, facts and feelings to parents, teachers, peers and others. The skills needed are varied. The adolescent must decide whom they will communicate with, the message they wish to share and the way they will transmit the message. For example, the way a teenager tells peers about a new relationship is not the same as the way they tell their parents (Mitchell & Ziegler 2007).

Psychosocial development

Adolescence is a time when the young person is seeking and learning the skills to become independent. It is often a period of emotional turmoil and insecurity, caused by the conflict between the need and desire for independence and the need to retain dependence on others. It is a time when identity is consolidated and a time when choices about vocation and lifestyle must be made. Relationships with parents undergo change and the adolescent begins to assert individuality and a desire for independence, often by resisting adult authority and advice. The adolescent usually displays mood swings, and experiences confused emotions. In later adolescence, emotions are better controlled and more mature. However, an older adolescent is still subject to heightened emotion and their expressive behaviour reflects feelings of insecurity and indecision (Crisp & Taylor 2009). As adolescents move into adulthood they normally become less reliant on positive reinforcement from others as their main source of self-esteem-enhancing experiences.

For those working with adolescents, knowledge of the theories of adolescent development is essential to obtain an understanding of the adolescent stage and the ability to recognise the tasks of adolescence. One such theory is Erikson’s theory of human development (1963) which encompasses the whole of the lifespan in eight stages, each of which involves opposing crises which must be negotiated to be able to go on to the next stage. This theory recognises the period of adolescence as a time spent searching for identity. Erikson sees identity (or role) confusion as the main danger of this stage. The adolescent’s search for identity involves the quest for individual, sex-role, moral and group identity (Mitchell & Ziegler 2007).

Group identity

The adolescent’s need to develop a personal sense of self is strong and an adolescent will often identify with a peer group that provides an identity. Adolescents seek to belong to a group to feel that they belong and have status. The pressure to belong to a group intensifies and, as the adolescent moves away from the family, the values of the peer group and their appraisal of them become increasingly important. Peer groups provide a sense of belonging, approval and the opportunity to learn acceptable behaviour. By developing close bonds with peers, adolescents are able to develop a frame of reference for their own identity (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Individual identity

A sense of identity is the individual’s concept of who they are and where they are going in life. To find out who they are, adolescents must formulate standards of conduct and know what they value as important and worth doing. This fulfils their need for a sense of their own worth and importance. Adolescents need to develop their own ethical systems based on personal values. When parental views and values differ greatly from those of peers and other important figures, the possibility for conflict is great. As a result, the adolescent may experience role diffusion as they try out one role after another and they may have difficulty in synthesising the different roles into a single identity. A positive identity eventually emerges after periods of confusion and adjustment, as the adolescent makes choices about the future.

Moral development (identity)

Moral development is consolidated in adolescence as the teenager moves from accepting the decisions of adults to gaining their own set of morals and values. Kohlberg (1964) explains moral development in terms of stages and, according to his theory of moral development, adolescents begin to question existing moral values and learn to make choices. The development of moral judgment depends on communication, cognitive skills and peer interaction. Not all adolescents reach the same level of moral development. Boys may have more justice-oriented responses to moral problems, while girls have been found to have more caring responses. Table 11.3 summarises the developmental behaviours of adolescents.

Table 11.3 I Developmental behaviours of adolescents

| Relationships with parents |

| Adolescents’ desires for increasing independence and autonomy and continuing need for some dependence and limit setting by parents place strain on their relationship. Effective communication and democratic parenting are best tools for meeting this challenge. |

| Relationships with siblings |

| Younger siblings rarely understand their adolescent sibling’s need for privacy to think, dream and talk with peers. Adolescents often enjoy interacting with and guiding younger brothers and sisters when timing is convenient for them and they can remain in control. |

| Relationships with peers |

|

Peer group is a factor of critical influence to adolescents, who have increasing need for recognition and acceptance. Companionship offered by peer groups provides a secure environment for individuals to try out new ideas and share similar feelings and attitudes. Adolescents often form cliques with peers from the same socioeconomic group with similar interests. Cliques, which are highly exclusive, help their members, who have strong emotional bonds, develop their identities. The crowd, which is more impersonal than the clique, offers opportunities for heterosexual interaction and social activities. The crowd also maintains rigid membership requirements; clique membership is usually a prerequisite for crowd membership. |

| Self-concept |

| Formal and informal peer groups are a primary force in shaping self-concept of group members. Popularity and recognition within the peer group enhance self-esteem and reinforce self-concept. Total immersion in peer group may make it appear that adolescents have no original thoughts and are incapable of making decisions. Adolescents who withdraw from peers into isolation struggle with developing identity. |

| Fears |

|

Fears in this age group centre around peer group acceptance, body changes, loss of self-control and emerging sexual urges. Adolescents constantly examine their bodies for changes and signs of imperfection. Any defect, real or imagined, is the cause of endless worry. Adolescents’ developing awareness of economic and political problems may result in fear of going to war, with its resulting death and destruction. |

| Coping patterns |

|

Repertoire of coping behaviours has expanded with experiences adolescents have gained from life and from developing cognitive maturity. By age 15, most use full range of defence mechanisms, including rationalisation and intellectualisation. Adolescents’ problem-solving abilities have matured, and they can reason through philosophical discussions and complex situations that require abstract thinking and proposition of hypotheses. Some adolescents use avoidance coping strategies in which the problem is denied or repressed and an attempt is made to reduce tension by engaging in chemical abuse or avoiding people. |

| Morals |

| According to Kohlberg (1964), as youths approach adolescence they reach conventional level, where internalisation of expectations of their family and society begins. Initially there is considerable conformity to rules to win praise or approval from others and to avoid social disapproval or rejection; later, they seek to avoid criticism from persons of authority in institutions. |

| Diversional activity |

| Many adolescents develop special interests in certain sports and concentrate on developing maximal skills therein. Recreational activities are often determined by what is popular with peers and what can provide independence from parents (e.g. computers, cars). |

| Nutrition |

| Total nutritional needs become greater during adolescence. Girls’ energy needs decrease and their need for protein increases slightly. Iron needed by adolescent boys is almost twice that of adult men, and growth spurts increase calcium demand. |

modified from Crisp & Taylor 2009

Social development

Social development involves an expansion of the network of social relationships and social activities. For many adolescents the peer group remains the most important social group, serving as a strong support providing a sense of belonging. It provides a link between independence and autonomy. Adolescents may move away from family domination and define their identity independently of parental authority. Adolescents may want to separate from parental restraints but at the same time may be fearful of the consequences associated with independence. This process of achieving independence often involves turmoil and ambiguity as both adolescent and parent learn new roles. Conflicts can arise from almost any situation or subject. Adolescents may find themselves argumentative, critical and remote with both parents as they attempt to achieve independence from parental controls. This rejection is usually not consistent and varies with mood changes. Some research shows that parents who provide a more cooperative style of parenting rather than an authorative style improve the adolescent’s ability to be independent and make appropriate decisions (Peterson 2009). Social relationships that develop outside the family help the adolescent identify their role in society.

Sexual development

Adolescence is a time of acute awareness and sensitivity to emerging sexuality and body image, when appearance, personal and sexual attractiveness and peer acceptance are of crucial importance to self-esteem and a sense of belonging (Varcarolis et al 2006; Videbeck 2007).

A positive self-concept and sense of emotional security depends significantly on the support the adolescent receives while coping with the physical and emotional changes experienced during the difficult and sometimes tumultuous transition to adulthood. Support includes allowing for privacy, the freedom to develop personal interests and new relationships and understanding the frequent changes of mood and behaviour that commonly occur.

Particular sensitivity is needed when nursing the ill or hospitalised adolescent, because changes or threats to appearance or functioning can have a profound impact, resulting in anxiety, feelings of vulnerability and a negative impact on self-image. The nurse can help the adolescent, as any other client, by demonstrating respect, which reinforces self-worth. The nurse can show this in many ways, including by being non-judgmental, reinforcing the belief that the client is doing their best to cope, to adapt or to change and by demonstrating acceptance of the adolescent client’s own perspective and feelings (Stein-Parbury 2009).

During adolescence there may be a great deal of experimentation in the expression of sexuality. Heterosexual and homosexual liaisons are common and sexual behaviour usually includes masturbation (Makadon 2007). Assurance about what is generally accepted as normal in physical and emotional development is helpful, as is open, honest and accurate information on topics such as body changes, sexual orientation, sexual practices, emotional responses within intimate relationships, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and contraception. (Information about contraception and reproductive health is provided in Chapter 35.)

There are times when the nurse may feel it appropriate to explore sexuality issues with an adolescent, for example, when working in sexual health clinics, adolescent mental health units and in drug and alcohol clinics.

Experts generally agree that sexual orientation is probably the outcome of complex interactions between biological, cognitive and environmental factors and that it is established at an early age but commonly emerges in adolescence. It is accepted that genetic and hormonal factors play a part in shaping a person’s sexuality to the extent that the person has no conscious choice in the matter, but also that there are probably many combining reasons for a person’s sexual orientation, which may be different for different people (Makadon 2007; Rathus et al 2007). Often it is difficult for the adolescent to discuss with their family and friends their thoughts in relation to their own sexuality or sexual orientation. Always be aware that the adolescent who is developing their sexual identity may not be ready or willing to discuss this issue with health practitioners either. Huffaker and Calvert (2005) suggest that the use of social media and virtual reality may be one area in which adolescents may feel more comfortable expressing their sexual orientation and exploring their sexual identity beyond social prescriptions. This is mainly due to the anonymity that can be gained by communicating online.

Many healthcare providers including nurses feel uncomfortable and unskilled in discussing sexuality with their adolescent clients. It is essential, therefore, that you first examine your own attitudes about sexuality, particularly those that relate to adolescents, and reflect on how these attitudes affect your work with teenagers.

ISSUES IN ADOLESCENCE

Social media

The adolescent of today has always had exposure to electronic media. The computer, the internet and mobile phones have been part of their lives since early childhood. Their use as a tool for communication is an important aspect of the adolescent’s life. There is significant discussion about the effects of the use of social media, with some researchers suggesting that heavy use can have negative effects, and others observing the positive influences that social media can have on adolescent development (Valkenburg & Peter 2007). Networking sites like Twitter and Facebook are often used by the adolescent to keep in touch with their friends and can be seen as positive tools in maintaining relationships. However, heavy usage of these sites may have risks for susceptible persons. Cyber bullying, stalking and predatory behaviour are just a few of the issues that can affect the adolescent user. Unfortunately the cyber bully can remain anonymous to the victim, making it difficult to track and/or halt the behaviour. It is suggested that the cyber bully can be motivated to use not only SMS phone text messages but to also use chat rooms and emails as tools of bullying. While research in this area is still fairly limited, it has been suggested that such bullying is widespread. The management of cyber bullying can be difficult due to its covert nature and the difficulty of tracing the offender (Cross et al 2009).

Body image

How the adolescent responds to the physical changes of puberty depends on their stage of development. In early adolescence some adolescents are preoccupied with the changes in their body and body image. Girls find body changes difficult to adjust to and are often concerned with weight increase and associated fat deposits. This may lead them to think they are obese and lead to fad dieting. Frequently they will compare their body with images in the media and their peers. With the increased use of ‘photoshopping’ of photographs of celebrities to remove evidence of imperfections and fat deposits, and the increasingly slimmer bodies of those portrayed in the media, the adolescent is often using an invalid measure to compare their bodies with. As the average model is 23% thinner than the average person and with the media praising and celebrating this fact, it can be very difficult for the adolescent to be satisfied with their body shape (Derenne & Beresin 2006). The nurse must be extremely cautious when working with the adolescent with body image distortions. Always refer to the care plan or seek advice from the RN when you are unsure how to approach an adolescent in your care who has body image issues.

Overeating or undereating during adolescence is of concern particularly for girls who, when they experience the normal increase in fat deposition and weight associated with the growth spurt, are more likely to resort to dieting.

Anorexia nervosa is a clinical syndrome with physical and psychosocial components. People with anorexia nervosa have an intense fear of gaining weight and refuse to maintain their weight at the normal minimal weight for their age and height. Bulimia nervosa involves binge eating followed by behaviours such as induced vomiting, use of laxatives and excessive exercise to prevent weight gain. It is important to take a thorough dietary history when working with these adolescents. Good and appropriate nursing care can make a significant difference in the recovery process of clients with anorexia nervosa (Ommen et al 2009). (See Nursing Care Plan 11.1 for a sample care plan for an eating disorder.)

Nursing care plan 11.1 Sample plan for the adolescent with anorexia nervosa

Assessment

Katie is a 15-year-old girl admitted to your ward with anorexia nervosa. Her weight has dropped to 45 kg, she exercises excessively, takes laxatives and will only eat small amounts of vegetables and fruit. She has recently broken up with her boyfriend and believes this is because she is ‘fat’

Obesity is becoming more prevalent in adolescence. American studies refer to ‘the childhood obesity crisis’ with research identifying that almost one-third of children in the US over the age of 2 are already overweight or obese (Wojcicki & Heyman 2010). Australian research also identifies similar findings, with up to 25% of all children between the ages of 5 and 17 identified as being either overweight or obese. In 2006–07 the prevalence of obesity in the 15–24 year age group in New Zealand was 14.2% (Ministry of Health 2009). There are now more severely obese children than ever. Poor nutrition and decreased physical activity have been identified as two major risk factors for individuals who are overweight and obese. In the adolescent the most immediate consequence of obesity is social discrimination associated with poor self-esteem and depression. They are also more likely to develop other comorbidities such as diabetes than children within normal weight ranges (Queensland Health 2008). This problem has serious ongoing affects across the health continuum.

CULTURAL DIVERSITY

With Australia and New Zealand rapidly becoming more multicultural it is important for the nurse to be aware of some of the cultural issues surrounding the development of the adolescent. Not all cultures have the same attitudes or beliefs about adolescence and it is extremely important that the normalised western theories of adolescence are not measured against all adolescent behaviours. While these theories are a sound template, cultural differences must always be considered. If you are caring for an adolescent from a culturally diverse background, ensure that the advice and care that you give are culturally appropriate.

Adolescents from diverse cultures and migrant families may have stressors that affect the way they behave. Immigration has its own inherent problems such as dealing with a new life pattern and issues of loss. And at times individuals face discrimination as they adjust to life within a new country. Conflict often occurs between the adolescent and their family in relation to social and gender differences between Australia or New Zealand and their country of origin (Murray & Zentner 2009). Chapter 8 of this text provides more insight into the cultural issues of Australia and New Zealand.

Indigenous adolescents

Australian and New Zealand Indigenous adolescents have not only the concerns of all adolescents, but also their own specific set of problems. They may feel alienated from both their traditional cultures and mainstream society. Without a thorough understanding of both the contemporary and the historical issues surrounding these two groups no appropriate understanding of the health and developmental issues of these adolescents can be gained. Readers are advised to research texts and articles specifically written for these groups to obtain further information.

As a nurse you are also urged to discover more about social determinants and their effects on the Australian and New Zealand Indigenous adolescent before attempting to make assumptions on the health status of the adolescents you are caring for. When developing health promotion and other tools to address these issues, care must be taken to ensure that the literature is culturally sensitive and in the appropriate language. It is essential to adopt a culturally appropriate approach to provide effective client education. Chapter 9 of this text provides you with a greater insight into Indigenous health.

HEALTH RISKS

The major causes of morbidity and mortality in adolescents are not diseases but health-damaging behaviours related to depression, injury, violence and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Risk taking

Adolescents are risk takers. While there are a number of theories which attempt to determine why the adolescent engages in risk-taking behaviours, it is often seen as a normal part of the adolescent process. Teenagers are good at weighing up the pros and cons of their decisions but take risks because they enjoy the thrill of a risky situation more than other age groups, especially when they have a ‘lucky escape’. Teenagers take risks, not because they do not foresee the consequences, but because they choose to take those risks (Burnett et al 2010). Research with adolescents has revealed that risk-taking behaviour is more prevalent among males, early school leavers, as well as youths with less parental supervision, peers who also actively engage in risk-taking behaviour, negative attitudes to authority and high alcohol use. Unfortunately, a tendency for risk-taking behaviour together with feelings of indestructibility makes adolescents particularly prone to accidents, especially those involving motor vehicles and sports. Risk behaviours in adolescents are reported to be the primary source of death in adolescents (Fredrickson & Levin 2007). (See Clinical Scenario Box 11.2.)

Clinical Scenario Box 11.2

While working in the accident and emergency department of the hospital a 14-year-old boy is admitted with a suspected fractured right fibula and tibia. When you are taking his vital signs he tells you that he fell off his bike while riding at full speed over a rough bush track. His parents are extremely distressed and keep saying that they had no idea why he would take such a risk. They thought that as he got older he would stop doing risky activities and were very worried that he was still doing so. This was his second admission to the hospital following an accident on his bike. The previous time was only 12 months ago. They blamed themselves for allowing him to ride his bike in the bush. While they were waiting for his leg to be plastered you spoke with them and discussed the reasons why adolescents take risks. You were able to reassure them that they were not to blame and that taking risks was often seen as normal in adolescence. You also helped them make an appointment with the social worker so that they could be referred to an appropriate professional about helping their son set limits on his risk-taking behaviours.

Suicide

Suicide accounted for 20% of deaths among older teenagers and young adults (aged 15–24 years) in Australia in 2004–06, making it the second most common cause of death in that age group (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2008). This compares to 1% of deaths among people aged 25 years and over. Every year approximately 100 young New Zealanders (aged 15–24 years) die by suicide. This accounts for about one-fifth of the total number of suicides each year. Suicide continues to be a significant cause of death accounting for approximately 25% of all deaths in this age group (Ministry of Health 2008).

In New Zealand men and Māori youth are particularly affected by suicide. Based on 2006 figures, young men have a rate of 31 per 100 000 population, which is significantly higher than the total population rate of 12 deaths per 100 000. The Māori youth rate is 33 per 100 000 population, compared with the non-Māori youth rate of 15 per 100 000 (The Social Report 2010).

Suicide usually results from a combination of factors and between 23.5% and 49% of teenagers have thoughts of suicide at some time (RCMH 2010). In adolescence it is often used to escape from a situation that they do not feel they can manage and it can be associated with depression. The following warning signs may occur for at least a month before a suicide attempt:

• Decreased performance at school

• Crying, sadness and loneliness

• Disturbance in sleep and appetite

Prevention of suicide always involves education. This can be done in major health promotional campaigns such as the Queensland Government Suicide Prevention Strategy 2003–2008 Queensland, (Queensland Health nd), the New Zealand Suicide Prevention Strategy 2006–2016 (Ministry of Health 2006) or in smaller campaigns run by school and community nurses or even one-on-one sessions with susceptible individuals. As a nurse, you need to be able to identify precipitating events and adolescent suicide risk factors. If assessment suggests that the adolescent is at risk of suicide you need to facilitate referral to mental health professionals while helping the adolescent to focus on the positive aspects of life and develop coping skills such as problem solving, anger management, conflict resolution and assertive communication.

Substance abuse

Substance abuse involves the use of mood-altering substances in an attempt to create a sense of wellbeing or improve levels of performance. The adolescent’s peer group can have a significant affect upon the individual’s use of illicit or other substances. All adolescents are at risk of substance abuse and have a higher risk of becoming addicted than an adult if abuse continues. The adolescent will use illegal/recreational substances for a number of reasons; these include perceived risk, social approval and availability (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Drug-related health problems vary according to the type of drug, how much is used and the duration of use.

Alcohol is one of the main substances that the adolescent is liable to abuse and although only a small percentage (2.6%) of all adolescents claim to have undertaken risky drinking, the percentage is increasing. Not only is alcohol use by the young person proven to be linked to dependence later in life, it also can have a detrimental effect on the maturing brain (AIHW 2009).

It is important to note that if the adolescent has a substance abuse problem it is not just an individual problem. Their network of family and friends will also be affected in some way.

Sexual experimentation

Sexual experimentation during adolescence is often seen as behaviour to confirm sexual orientation. The two main consequences of sexual activity during adolescence are sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unplanned pregnancy. At least 1 in 4 sexually active teenage American girls has a sexually transmitted disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2008). While these are American statistics it is reasonable to assume that the figures would be similar in Australasia.

A thorough sexual history should be included in any screening of adolescent health. The nurse can use the interview process to identify risk factors. Education about the ways STIs are transmitted is recommended, as most adolescents believe they are not at risk. The rate of adolescent pregnancy has fallen in Australia. This is a result of education and the availability of contraception and, in most states and territories, access to abortion. (See Clinical Interest Box 11.2.)

HEALTH PROMOTION

Health promotion for adolescents consists mainly of teaching and guidance to avoid health-damaging behaviours and risk-taking activities. Health professionals who work with adolescents should acknowledge their increasing independence and responsibility, and try to maintain privacy and confidentiality. Health promotion during adolescence is directed towards:

• Establishing healthy habits of daily living in relation to personal care, such as vision, hearing, posture, body-piercing and sun-tanning

• Education in stress-reducing techniques

• Providing information on nutritional requirements and eating habits and behaviours

• Accident prevention in relation to vehicle-related injuries and sport injuries

• Education about sexuality and guidance on avoiding STIs and unplanned pregnancies

(See also Table 11.4.)

Table 11.4 Health promotion during the adolescent period

modified from Crisp & Taylor 2009

Nurses need to be aware of the prevalence of adolescent problems affecting healthy habits of daily living and must make assessments accordingly. Community and school-based health programs focus on illness prevention and health promotion. Nurses can play an important role in preventing injuries and deaths related to accidents and substance abuse. You will find more information about health promotion in Chapter 5.

NURSING IMPLICATIONS

All nurses caring for the adolescent need to understand that this is a lengthy transition period. During this transition from childhood to adulthood, the adolescent undergoes a significant number of changes and these changes are both diverse and complex.

These changes can cause considerable emotional stress for the adolescent which can manifest in many ways. The adolescent will often rebel against rules and regulations, criticise treatment and be uncooperative. This may be due to a combination of an instinctive negative reaction against authority and hidden anxieties and fears. Much of the behaviour observed in the adolescent is related to the struggle for independence and the external constraints that are placed on this maturation process. It is essential that the nurse has a strong understanding of the issues of adolescence and provides an empathetic and understanding approach to care. More information on care of the hospitalised adolescent can be found in Chapter 19.

Summary

Adolescent behaviour patterns highlight the need for the nurse to understand the expected process through which an adolescent passes. Adolescents cannot be cared for wholly as adults, as they often lack the emotional maturity to cope with independence and still require the emotional support of parents or adult carers. Nurses with an understanding of adolescent phases will be able to develop an environment that provides privacy and protects independence, which will enable the adolescent to feel supported in unfamiliar surroundings.

1. You are employed as an enrolled nurse (meds) in a small 12-bed country hospital. You are working with one registered nurse and a carer. During the registered nurse’s break you notice that a rather unkempt-looking girl of about 15 years has walked into the reception area. You approach her to find out what she wants. Tearfully she explains to you that she thinks she may be pregnant. While speaking with her you find that she does not know when her last period was and is not really clear when she had sex. What are the issues in this situation? How should it be handled?

2. You have just been advised by a colleague that her 12-year-old son has spent the money he was saving to go to a basketball camp in the holidays on a video game. She is quite angry and tells you that he should know better, stop living for the present and start thinking about the future. Considering the developmental stage that her son may be in what could you say to her to about her son’s behaviour?

1. Briefly explain why the physical changes during puberty take place.

2. What differences would you expect to find between a 10-year-old preadolescent and a 16-year-old adolescent? Consider physical, cognitive and psychosocial aspects.

3. What observable behaviours would you find if caring for an adolescent who is at risk of suicide?

4. Give a brief explanation of why the adolescent is more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviours than individuals in other age groups.

Select True (T) or False (F) for each of these statements:

| Select True (T) or False (F) for each of these statements: | ||

| Puberty is the time following the completion of all body changes. | T | F |

| Concrete operational thinking is a cognitive developmental stage. | T | F |

| Risk taking is an issue best managed with psychiatric help. | T | F |

| One set of health promotional materials can be used for all cultural groups. | T | F |

| The use of social media should be discouraged during adolescence. | T | F |

| Nurses should always refect on their own attitudes before advising the adolescent. | T | F |

| Systolic blood pressure increases during adolescence. | T | F |

| Suicide is the most common form of death in adolescence. | T | F |

| Peer groups are important for the adolescent. | T | F |

| Breast buds appear in girls after menarche. | T | F |

References and Recommended Reading

Atherton JS. Learning and Teaching; Piaget’s developmental theory. Online. Available: www.learningandteaching.info/learning/piaget.htm, 2011.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Risk Taking by Young People. Online. Available: www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/lookup/4102.0chapter5002008, 2008.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2009) Australian Demographic Statistics, March 2009. ABS Catalogue no3101.0. ABS, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). National Survey of Adult Oral Health 2004–2006. Canberra: AIHW, 2008.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2009) A Picture of Australia’s Children 2009. Cat. no. PHE 112. AIHW, Canberra

Burnett S. Teenagers Programmed to Take Risks. Online. Available: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/03/100324211144.htm, 2010.

Burnett S, Bault N, Coricelli G, et al. Adolescents’ heightened risk-seeking in a probabilistic gambling task. Cognitive Development. 2010;25(2):183–196.

Carpenito-Moyet LJ. Nursing Diagnoses: Application to Clinical Practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 in 4 Teen Girls Has Sexually Transmitted Disease. Online. Available: www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23574940, 2008.

Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. Online. Available: www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.html

Crisp J, Taylor C. Potter & Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 3rd edn., Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

Cross D, Shaw T, Hearn L, et al. Australian Covert Bullying Prevalence Study (ACBPS). Perth: Child Health Promotion Research Centre, Edith Cowan University, 2009.

Derenne JL, Beresin EV. Body Image, Media, and Eating Disorders. Online. Available: http://ap.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/30/3/257, 2006.

Erikson EH, Childhood and society. Crisp J, Taylor C. Potter and Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 3rd edn., Sydney: Elsevier, 1963. (2009)

Fredrickson K, Levin R. Evidence-based practice: a reliable source to access interventions for youth risk behaviours. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2007;21:149–152.

Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D, Winkelstein ML. Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing, 7th edn., St Louis: Mosby, 2005.

Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D. Wong’s Nursing Care of Infants and Children, 9th edn. Mosby: St Louis, 2011.

Huffaker DA, Calvert SL. Gender, identity, and language use in teenage blogs. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 10(2), 2005. Online. Available: article 1: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue2/huffaker.html

Hughes F, Gray N. Cultural safety and the health of adolescents. British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7412):457. Online. Available: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC188531/

Jewish Virtual Library. Bar Mitzvah, Bat Mitzvah and Confirmation. Online. Available: www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/barmitz.html, 2012.

Kashan A, Baker P, Kenny L. Preterm birth and reduced birth weight in first and second teenage pregnancies: a register-based cohort study, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth Journal. Online. Available: www.biomedcentral.com/imedia/1079982345357945_article.pdf?random=396763, 2010.

Kohlberg L, Development of moral character and moral ideology. Hoffman ML, Hoffman LNW, eds. Review of Child Development Research, Vol 1. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1964.

Le Hoyt P. La Quinceañera: A Celebration of Budding Womanhood. Online. Available: www.mexconnect.com/articles/3192-la-quincea%C3%B1era-a-celebration-of-budding-womanhood, 1997.

Ministry of Health. The New Zealand Suicide Prevention Strategy 2006–2016. Ministry of Health, Wellington. Online. Available: www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-suicide-prevention-strategy-2006-2016, 2006.

Ministry of Health. Suicide Facts: Deaths and Intentional Self-harm Hospitalisations 2006. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2008.

Mitchell P, Ziegler F. Fundamentals of Development: the Psychology of Childhood. East Sussex: Psychology Press, 2007.

Murray R, Zentner J. Health Promotion Strategies through the Lifespan. New Jersey: Pearson Education, 2009.

Ommen J, Meerwijk E, Kars M, et al. Effective nursing care of adolescents diagnosed with anorexia nervosa: the patients’ perspective. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18(20):2801–2808.

Peterson C. Looking Forward through the Lifespan. Developmental psychology, 5th edn. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson, 2009.

Queensland Health. Submission: Inquiry into Obesity in Australia. Brisbane: Queensland State Government, 2008.

Queensland Health. (nd) Reducing Suicide: The Queensland Government Suicide Prevention Strategy 2003–2008. Online. Available: www.health.qld.gov.au/mentalhealth/docs/qgps_report_apr06.pdf.

Rathus SS, Nevid JS, Fichner-Rathus L. Human Sexuality in a World of Diversity. New Jersey: Allyn & Bacon, 2007.

Religious Tolerance.org Coming-of-Age Rituals. Online. Available: www.religioustolerance.org/wicpuber.htm.

Santrock J. Child Development. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2007.

Sigelman CK, Rider EA. Life-span Human Development, 7th edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2011.

Softpedia. The Land Diving Ritual. Online. Available: http://news.softpedia.com/news/The-Land-Diving-Ritual-37949.shtml, 2012.

Stein-Parbury J. Patient and Person: Interpersonal Skills in Nursing, 4th edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

Tassell NA, Hirini PR. Maori Child, Adolescent and Whanau Workforce Development. Online. Available: www.matatini.co.nz/cms_show_download.php?id=75, 2004.

The Heart of Hinduism. Samskaras: Rites of Passage. Online. Available: http://hinduism.iskcon.org/practice/600.htm, 2004.

The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne (RCMH). Youth Suicide in Australia. Online. Available: www.rch.org.au/cah/research.cfm?doc_id=11036, 2010.

The Social Report. Suicide. Online. Available: www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz/health/suicide.html, 2010.

Thomson N, MacRae A, Burns J, et al. Overview of Australian Indigenous Health Status, April 2010. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet, 2010. Online. Available: www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/uploads/docs/overview_of_australian_indigenous_health_status_apr_2010.pdf

Tortora G, Derricksen B. Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, 2008.

Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Online communication and adolescent well-being: Testing the stimulation versus the displacement hypothesis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 12(4), 2007. article 2. Online. Available: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol12/issue4/valkenburg.html

Varcarolis E, Benner-Carson V, Shoemaker NC. Foundations of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing: A Clinical Approach. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2006.

Videbeck SL. Psychiatric Mental-Health Nursing, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

Walrond C. Te Ara—the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Online. Available: www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/cook-islanders/2/3, 2011.

Wojcicki J, Heymann M. Let’s move—childhood obesity prevention from pregnancy and infancy onward. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:1457–1459.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, www.abs.gov.au.

Better Health Channel, www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au.

Headspace (National Youth Mental Health Foundation), www.headspace.org.au.

Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand, www.mentalhealth.org.nz.

Raising Children Network, www.raisingchildren.net.au.

Suicide Prevention Information New Zealand, www.spinz.org.nz.

Suicide Prevention (Australia), www.suicideprevention.com.au.

The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, www.rch.org.au.

United States National Library of Medicine, www.nlm.nih.gov (links to Medline)

Urge (Youthline New Zealand), www.urge.co.nz.