CHAPTER 19 Admission, transfer and discharge processes

At completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to

• Describe the planning and implementation of care for the client who requires admission, transfer or discharge

• Describe the means by which a child may be prepared for admission to hospital

• Identify common stressors related to illness and hospitalisation

• Describe the physiological and psychological responses to stress

• Demonstrate a range of nursing skills that alleviate stress in anxious clients

The scenario when an individual is admitted to a healthcare facility such as a hospital can represent a major disruption for the client and their significant others, resulting in anxiety, not only regarding their admission but also the implications and causes of their illness. While all hospitals have subtle variations in the process of admission, the basic protocols generally remain the same. During this time of heightened anxiety and fear, the nurse has a key role in alleviating some of the fears of hospitalisation, not only for the client but also for their loved ones. This chapter focuses on the admission process, the transferring and the discharge of children, adolescents and adults and the nurse’s role in ensuring these processes cause minimal disruption.

My son was 3 when he was first admitted to hospital. He’d been having continuous ear infections and sinus problems and his specialist decided that he should have grommets inserted and his adenoids removed. We booked a date, and I tried to put it to the back of my mind, and then the day was finally here. I was so nervous and worried for him. I tried to keep replaying what the specialist had said about how ‘routine’ his surgery was, but when they came to wheel him away, I broke down. The theatre nurse was so warm and caring, but I still felt so silly. It’s not easy leaving your child in the care of strangers.

TYPES OF ADMISSION

Admissions are classified as either elective or non-elective. Admissions are deemed elective when they are planned and not emergent and while acuity is generally not severe, the potential to deteriorate and require intervention is possible (Berman et al 2012). Clients awaiting an elective admission can often be on waiting lists until such time that a hospital bed becomes vacant. They usually receive a letter or phone call to advise them when their procedure will be performed.

Non-elective or emergency admissions occur, by their very nature, suddenly, and may be associated with severe injury or life-threatening disease. They are the cause of about 90% of all hospital admissions (Willis et al 2009). Clients in emergent situations may be admitted any number of ways, including through referral from their medical practitioner, or the emergency department of a hospital, or perhaps by ambulance.

Healthcare facilities individually have policies regarding the admission and discharge process for elective and emergency admissions. In most cases clients presenting for elective procedures will report to an admitting department on a prearranged date and time for the purpose of commencing the admission process. Prior to reporting for their procedure the client should have received some written material with information regarding their diet prior to admission (e.g. fasting for surgery), whether to cease taking particular prescription or over-the-counter medications, what items to bring (e.g. toiletries, clothing) and information regarding visiting hours and the provision of telephones, televisions and location of the cafeteria (Mitchell 2007).

REACTIONS TO ADMISSION

With the possible exception of maternity, the majority of individuals facing admission to a hospital do so with trepidation and reluctance. Regardless of the duration of the hospital visit, admission is likely to cause a degree of stress, and reactions to this stress will vary depending on a number of factors including age, gender, past experiences and expectations. The principal causes of anxiety that hospitalised individuals experience are predominantly related to fears associated with anaesthesia, pain and complications (Sveinsdoóttir 2010). While elective procedures are often associated with lower levels of anxiety, the nurse must acknowledge that all clients will have an individual and valid reaction to the impending stress of hospitalisation in their life.

Stress is widely regarded as an aversive state of arousal in which a physiological response occurs in reaction to a demand or stressor (Elder et al 2009; Fontaine 2009; Kring et al 2010). Stress can be experienced as either psychological or physical and can result in a range of varying responses which require a response or change. The stressful impact of hospitalisation on an individual’s self-esteem, self-concept and body-image are varying and diverse and include:

• Loss of independence and vulnerability

• Relationship disruptions and fretting about loved ones

• Unfamiliar environment, equipment and personnel

• Potential loss of income and impacts on employment

• The nature and implications of the illness

• Painful and/or embarrassing tests or procedures

• Impacts on activities of daily living (ADLs)

Reactions to stress and coping mechanisms include:

Physiological manifestations of stress include:

• Elevated blood pressure, pulse and respirations

• Difficulty concentrating (Elder et al 2009; Fontaine 2009; Fortinash & Holoday Worret 2008; Happell et al 2008; Kring et al 2010).

It is essential for the benefit of the client that the nurse acknowledges the distress this anxiety may be causing the client, and demonstrates empathy, warmth and respect while preserving dignity and independence (Happell et al 2008; O’Toole 2008). The nurse should adopt a collaborative approach to care that is inclusive of the client’s rights and needs, through empowerment and mutual understanding (Kelly 2007; O’Toole 2008). Advocating for collaboration in care is fundamental; when clients are empowered and involved in the decision-making processes of their treatment, improved nursing outcomes ensue (Norman 2010).

Illness and stress

Hospitalised adults

Hospitalisation means that clients are not, for the duration of their stay, able to follow their usual daily routines; for example, the diet or exercise they are used to. They often severely miss the lack of home comforts and the presence of family, friends and familiar things. They may also be stressed by an unknown diagnosis and frightened about possible pain and discomfort, potential treatments and outcomes. The nurse can help alleviate some of this anxiety by providing full and timely information. Anxiety can affect concentration and memory, so when a client is anxious it is particularly important to ascertain whether the information has been understood, to repeat it if necessary and provide written information that the client may consider later.

Clients also have to adapt to stressors such as the lack of privacy, which may include concerns about sharing a room with strangers, strangers finding out about their medical details, having to wear hospital gowns that are open down the back, exposure of private areas during surgery, investigative procedures or treatments and having healthcare workers coming into their room during toileting or bathing. The nurse can help alleviate some of these stressors by introducing newly admitted clients to those in the shared room, by being diligent about protecting confidentiality and taking practical steps to prevent unnecessary exposure. Nurses not assisting with personal care should themselves undertake not to enter the room or the area behind closed curtains without first confirming that the client is not exposed.

Some clients may be very anxious about the ability to meet religious dietary, worship, modesty or hygiene requirements. Those with limited spoken English are likely to be stressed about the ability to understand or be understood. A nursing assessment that carefully identifies cultural and spiritual needs is the tool that helps the nurse minimise associated stressors. Resolution might include coordinating care to allow time for prayer, adapting western-oriented hygiene methods to suit specific modesty needs and involving an interpreter.

Other stressors include worry about family responsibilities, costs of medical treatment and perhaps loss of earnings while ill. Compounding the problem there may be an inability to sleep because of pain, discomfort, noise, a strange bed or missing the usual sleeping partner. Empathic and considerate general nursing care activities can significantly reduce these common anxieties.

A significant aspect of care related to minimising stress is the establishment of a relationship that demonstrates respect and empathy for the client. This includes being prepared to sit and listen to the client and facilitating the expression of fears and anxieties.

Children

It is not unusual for children to feel anxiety. Very young children often fear strangers or being left alone; preschoolers often fear imaginary creatures, animals and the dark. School-age children may experience anxiety about their own safety; for example, being very anxious during a storm. As children move towards the middle years of school and head into adolescence, anxieties tend to become more focused on performance at school, appearance and other social and health issues.

It is quite common for children to develop fears about losing their parents (separation anxiety). When this anxiety is strong, children may be diagnosed with separation anxiety disorder. Children who have separation anxiety may experience physical symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, stomach pains, palpitations, respiratory difficulty and dizziness. Separation anxiety can occur at any age. Children may follow parents around the house, needing to be constantly in very close proximity, they may refuse to go to school and may worry about being kidnapped and killed, or their parents being killed. Most children outgrow this fear but some have symptoms that recur periodically and especially when attachments are threatened or disrupted, such as at the time of hospitalisation (Fontaine 2009).

The nurse who is aiming to reduce stress in children is most therapeutic when able to listen actively and encourage dialogue with open questions such as, ‘Tell me about what you like playing with at home’. It is best to avoid the specific question–answer format because children tend to feel uncomfortable about this and answer with very short, simple responses that give little information. Communicating effectively with children is a specific communication skill. Children are very sensitive to insincere platitudes and fake sentiments and are usually very quick at determining if a nurse is genuine and can be trusted.

Working with emotionally stressed children in the area of mental health is an area of specialty. A variety of therapies is helpful, including play therapy, art therapy and guided imagery. The goals of therapy are to:

• Help children reveal feelings they are unable to verbalise

• Enable children to act out feelings, anxieties or tension in a constructive manner

• Understand children’s relationships and interactions with others of significance to them in their lives

Guided imagery and children

Guided imagery is an anxiety-reducing technique that many adults find helpful. It is a form of therapy that helps clients consciously visualise positive images to lift their mood, reduce their anxiety, deal with the effects of illness or trauma or prevent illness (Hitchcock & Schubert 2002). In a simple form it can successfully be used with children to increase their coping skills and enhance their feelings of self-worth. Children usually have strong imaginations and are able to conjure up mental pictures quite easily. Guided imagery begins with a short relaxation exercise followed by general directions for the imagery (visualisation). Children may be gently guided towards mental images of heroes and heroines that help them cope, and may be able to visualise themselves and their families as happy and cheerful. They may also imagine different ways of interacting with others (Fontaine & Fletcher 2002). For example, Laura, aged 10, had frequent nightmares and was very frightened of the ‘dark monster who comes in the night’. She was able to imagine herself a friend to a fire-breathing dragon. Through guided imagery she learned how to call on her dragon friend, whom she called Sheba, to come and stay by her to protect her whenever she felt scared.

Adolescents

Sometimes high levels of stress during hospitalisation can result in adolescent behaviours that challenge the nurse. The adolescent years are a time of incredible physical and psychological adjustment. The tasks of adolescence include acceptance of a changed body image, establishing independence from parents, deciding on a career pathway and adjusting to a comfortable sexual role. The adolescent may be supersensitive to recent body changes and may have concerns about body image. The threat of body exposure may be a source of great embarrassment. The nurse can help reduce adolescent stress by respecting client autonomy and valuing the client as a person, facilitating the verbalisation of fears, demonstrating sensitivity to concerns about body image, exposure and function and providing clear explanations about all care, treatment and procedures.

Common reasons for hospitalisation in adolescence include vehicle and sporting accidents, unsuccessful suicide attempts, teenage pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, drug abuse and depression. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are also common but are generally treated on an outpatient basis unless severe enough to be life-threatening (Shives 2007). Whatever personal views the nurse may hold about these issues, every client deserves to be cared for with compassion and without judgment.

Sometimes concerns are overwhelming for the adolescent and may result in emotional responses such as resentment, hostility or guilt. The hospitalised adolescent may become isolative, manipulative and reject hospital rules or even physical care if feelings such as fear, guilt or embarrassment are unmanageable (see Clinical Scenario Box 19.1).

Clinical Scenario Box 19.1

The link between fears and behaviour

Melanie, 15, was diagnosed with diabetes. She was resentful and hostile towards the nurse who was encouraging her to self-administer her insulin medication. Melanie stormed away, shouting and refusing the treatment altogether. A little later the nurse sat and talked with Melanie, who eventually disclosed fears about how having diabetes would affect her social life. She also revealed beliefs that the diabetes was her own fault, a punishment for promiscuous behaviour and a termination of pregnancy that she had not told her parents about. The nurse listened without judging Melanie, alleviated some of the guilt by answering questions about the onset of diabetes and helped her to identify some ways that she might cope with the diabetes after discharge.

Stressors may be lessened by supportive peer interactions. Visits from friends are important, especially when adolescents are placed on wards with only adults for company. This may help relieve anxiety about missing school, social activities or losing touch with the peer group. Sometimes the adolescent client’s feelings and fears can be exacerbated because adult clients in a shared room tease or give erroneous advice or information. It should be acknowledged that while the adolescents may strive to demonstrate adult behaviour, they may be struggling with homesickness—hospitalisation is sometimes the first time young teenagers have been separated from parents or family without being with their peers (Shives 2007). Nursing interventions to address adolescent emotional responses and some of the more common behaviours are identified in Table 19.1.

Table 19.1 Nursing interventions for a selection of common adolescent emotional responses and behaviours

Older adults

People in the older age group frequently experience many losses and changes in a relatively short time frame. Some older people adapt effectively to the stress this causes. Many are able to plan and implement a successful transition from work to retirement. Many are able to respond positively to the challenges and find exciting and creative activities that provide a high quality of life well into old age. Others experience difficulty with the transition, the accumulative losses and changes and suffer stress overload. Nurses may be able to observe signs of this, such as unconscious repetitive actions that serve to relieve tension and stress and, sometimes, changes to cognitive abilities. Many physical changes such as those that affect sight and hearing or mobility may occur gradually and this allows time for the process of adaptation. However, such stressors, whether slow or sudden, may compound with social losses and concerns about the future to the point where strong inner resources are needed to avert a stress crisis. Some of the stressors faced by older people include:

• Increases in rent or living costs and ability to manage financially now or in the future

• Coping with home maintenance

• Loss of driver’s licence or transport independence

• Death of friends, siblings or pets

• Concern about care and protection when frail and vulnerable

• Fear of losing, or loss of, mental abilities

• Fear of loneliness, dying alone or not being found

• Fear of institutionalisation and leaving own possessions or pets

• Intolerance or negative ageist attitudes demonstrated by others

Anxiety and low self-esteem often occur together and particularly in older people who are ill, hospitalised or living in residential care settings. The way care is provided and the nurse’s communication with clients or residents can have a highly positive effect on reducing anxiety and increasing morale. Two basic principles for minimising stress are:

1. Limiting change as much as possible; for example, when and where possible, have the same people provide services and care (change increases stress) (see Clinical Scenario Box 19.2).

2. Coordinating care and implementing any essential changes during the times when clients are best able to cope. People frequently have times of the day, month or year when they are functioning better or are less stressed than others; for example, it would not be advisable to discuss changing a client’s accommodation arrangements late in the evening if that is when they are most tired; it would be unwise to introduce any major changes near the anniversary of a significant bereavement.

Clinical Scenario Box 19.2

Avoiding change—regular services reduce client stress and increase ability to cope

Mavis is totally dependent now; she can’t move much at all. I change her, feed her, put her to bed. I do all the cooking. I used to cope better when Joanne was our regular nurse. She came as regularly as clockwork to bath Mavis. She came at the same time every day, except weekends, for 8 years. She could do it all herself, manage the lifter and everything. While she was here I could sit and have my breakfast, read the paper and relax. It was the thing that set me up for the day. Since Joanne left to have her baby we have had a constant stream of different people, for weeks now, not even always the same time of day. Mostly I have to show the new ones how to do it, help them get her into the lifter. I just get them knowing what needs doing when a different person comes. I really miss that one little bit of peaceful time in the mornings, and Mavis doesn’t even bother trying to talk to them now. She used to enjoy her bath with Joanne. Now we both hate it and I don’t know how much longer I can go on like this. Some days I feel like screaming and I’ve even thought about walking out. It’s surprising what a difference that little bit of time made.

(Frank, 68, carer husband of Mavis, who has multiple sclerosis)

The nurse can also help to limit the damage from the structural and chemical changes to the body and the risk of illness caused by prolonged stress by ensuring that, whenever possible, the client has a highly nutritious diet, and by ensuring the provision of an environment and nursing strategies that ensure the client obtains adequate rest and sleep (Ebersole et al 2008).

Preventing and treating stress in the older person

Preventing and treating stress in the older person includes promoting self-worth, a sense of control, feelings of connectedness and hope. The nurse can facilitate feelings of self-worth by complimenting clients on their achievements and encouraging reflection on personal strengths. A sense of control can be promoted by allowing clients to make decisions for themselves. For a client with dementia this may mean offering simple choices that do not confuse, for example, ‘Would you like to wear this dress today?’ Simple actions such as encouraging participation in group activities, introducing clients to each other and smiling and speaking to the client that you pass in the corridor helps to foster feelings of connectedness. Providing pleasurable experiences and things to do fosters happiness and hope, even in very difficult circumstances. For example, the client who has cancer or a degenerative disorder can still enjoy the pleasures of music, a beautiful garden, the smell of roses, the company of pets, children and other social interactions.

THE ADMISSION PROCESS

Preadmission

Preadmission clinics are an important aspect in the provision of holistic and continuous care. They can reduce a client’s anxiety regarding their admission (this is particularly beneficial with children), and provide and obtain useful health history information and assessment of vital signs (Giangiulio 2008). It is during preadmission that discharge planning should (and does) commence, and provides the client with opportunities to ask questions, tour the ward (if applicable) and familiarise themselves with staff and routines (Goodman 2010; Kralik & van Loon 2011).

Admitting an adult to a healthcare facility

When an individual is admitted to a healthcare facility, potential anxiety can be reduced by the efficiency and effective organisation of this process in an empathetic and sensitive manner. Effective admission procedures are directed towards:

• Confirming the client’s identity

• Assessing the client’s physical and psychological status

• Promoting the client’s comfort in an unfamiliar environment

• Providing items needed for care

• Providing the client with information about various practices and protocols

• Providing the client the opportunity to ask questions (Berman et al 2012; Jarvis 2008).

Day of surgery admission

Many hospitals are admitting elective surgical admissions to a specialty unit designed to facilitate admissions to theatre. This ensures a smoother transition to the operating theatre. Nursing and medical staff work together to ensure each client is prepared for theatre. Clients are sent home with a friend or relative who can watch them (of particular importance after a general anaesthetic), and a brochure on what signs and symptoms to look for, analgesia management and emergency contacts.

Admitting department

Medical admissions and many elective surgical admissions are transferred from the admitting department directly to the unit. Clerical staff confirm the client’s identity and admission details before escorting the client to the allocated unit, where they are received by the nurse.

Room preparation

Prior to the client’s admission to the unit, the nursing team will determine the location of their bed. Depending on the client’s individual needs and room availability, they may be admitted into a shared or single room. Prior to the orientation of the client to the unit, the nurse should ensure that the room is in order and that all necessary items are available. The room will likely contain a bed, bedside locker, over-bed table, chair and wardrobe. The location of showering and toileting facilitates may be located in the client’s room, or communally out on the unit. The bed may need to be adapted to meet specific needs; namely the provision of extra pillows, a bed-cradle, high-low bed, falls mat, padded cot sides or a sheepskin blanket (Berman et al 2012).

Although the items placed in the room may vary slightly in different healthcare facilities, the basic items provided for each individual are two bath towels, two face washers and an information booklet. Information provided in this booklet usually involves aspects such as details of visiting hours; meal times; how to identify various personnel; cafeteria, telephone, television and laundry facilities available; regulations regarding smoking, and the time the individual is expected to vacate the room upon discharge. Extra items such as oxygen equipment, suction apparatus or an intravenous pole are placed in the room if required. The top of the bedclothes may be turned back or they may be folded down to receive a client who arrives on a trolley (Berman et al 2012).

Reception of the client

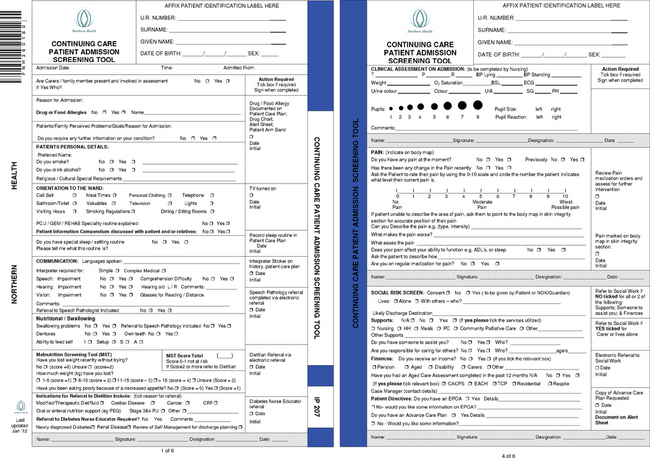

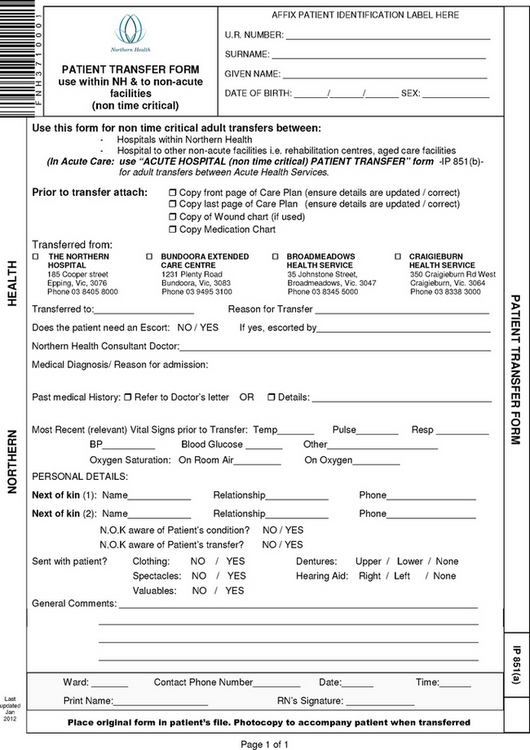

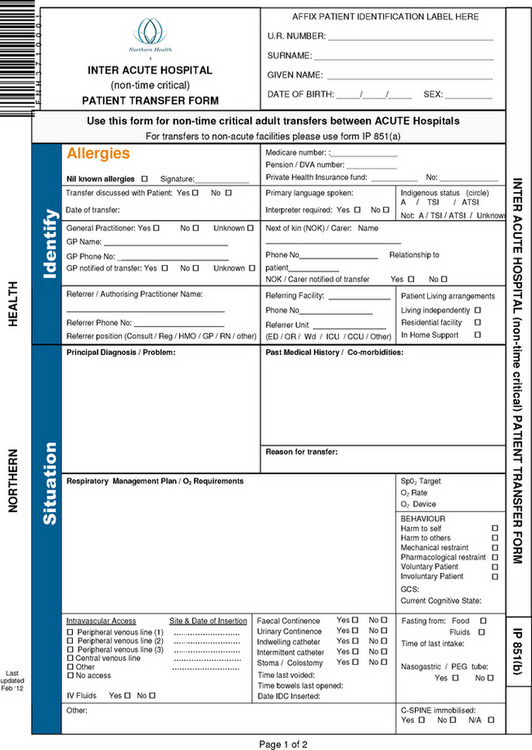

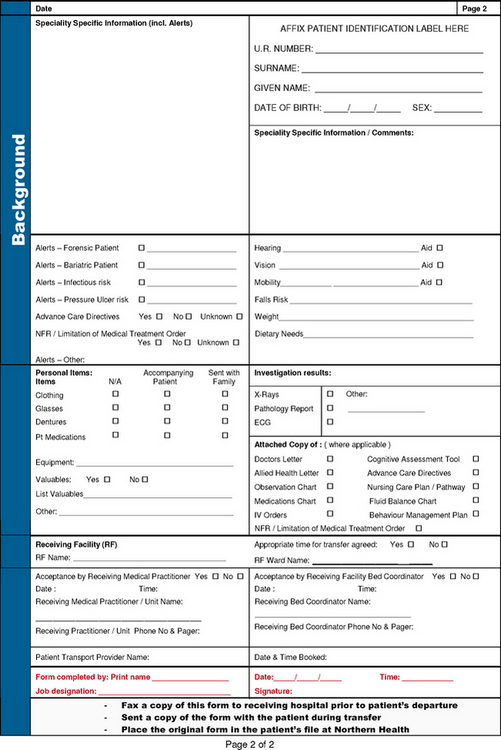

Chapter 17 provides details of the admission assessment. Unless the admission is emergent, prior to arrival in the unit the client should report to the admitting department of the healthcare facility. Here a member of the clerical staff obtains and records information including the person’s full name; age; gender; marital status; religion; next of kin contact details (name, address, phone number); private insurance details (if any) and Medicare number. An identification band (Fig 19.1) is placed on the client’s wrist as a basic safety precaution against mistaken identity and treatment. If the client has any medication allergies, an alert wrist band will also be placed on them. Some facilities require a wrist and ankle identification band. Should the client require an x-ray or pathology test, they will be referred to this department prior to admission to the unit. The client will then be escorted to the unit where a nurse will receive and orientate them.

The nurse, who has been allocated the admission of the client, should greet them and any accompanying friend or relative in a warm and friendly manner. The nurse should address the client by their preferred name and introduce themselves, then escort the person to the room and begin the process of admission. Depending on the circumstances, a relative or friend may be present and may be offered a seat in a waiting area.

The admission procedure is basically the same in most healthcare facilities but will vary in detail in different settings, and in sequence, according to circumstances. The client is taken to their room and if they are sharing, introduced to any other person in the room. It is important to remember the significance of respecting privacy in a shared room by drawing curtains and lowering your voice in these situations. The client should be shown the layout of the room, including where to stow personal belongings. It is important that the client is shown how to use the signal device (call bell), and how to operate the electronic bed, lights, television and radio controls. The client’s identity band should be checked against the bed and or/treatment sheet to ensure they are correct. Depending on the circumstances, the client may remain in day clothes and be able to walk about the unit, or they may be required to change into hospital-provided clothes or personal night attire and get into bed.

Although the client will have been advised not to bring valuable items, an inventory is made of any personal effects. Generally it is not necessary to itemise clothing, but a list compiled of any items of value, such as wristwatch, jewellery, television set, radio and money may be needed. Some healthcare facilities also require that documentation is made of any prosthesis, such as dentures, eye glasses, hearing aids or a prosthetic limb. If the client has arrived with a large sum of money they are encouraged to either send it home with a relative or to place it in the healthcare facility’s safe. A ‘valuables’ envelope is provided for the safe-keeping of money or other valuable items. It is very important to inform the client that the healthcare facility accepts no responsibility for valuable items, unless they are deposited in their safe. The nurse is advised to follow individual hospital policies regarding the procedures to be followed when clients’ valuables are stored.

As soon as practicable, assessment is made of vital signs and weight, and this information is documented in the clinical file. A sample of urine may be obtained and urinalysis performed. (Information on vital signs and urinalysis is provided in Chs 18 and 29.) The client’s height may also be measured and documented.

Throughout the admission procedure, the nurse should discreetly observe the client to gain information that will assist in planning care. Assessment is made, and documented (Fig 19.2) of the client’s:

• Level of consciousness and orientation

• Use of prostheses or aids. (Berman et al 2012; Jarvis 2008).

At the time of admission or as soon as practical afterwards, a nursing history is compiled and a nursing care plan developed. (Information on these and other aspects of the nursing process is provided in Chs 15 and 16.)

Unless the client is on fluid restriction due to their illness or impending surgery, they should be offered a jug of water and a cup of tea or coffee. Anyone accompanying the client may also be offered a drink, or directed to the cafeteria and telephone areas. This assistance is of particular importance in the event of an emergency admission. It is common for significant others to be very distressed, and it may be appropriate for them to be shown to a private area where they can rest or contact family. The hospital may also provide accommodation options for relatives if the client is very ill.

Prior to leaving the room, the nurse should ensure that the client and significant others have been given all the information they require, in conjunction with an opportunity to ask any questions. Should the nurse be unable to answer any questions, it is important that the family be referred to the appropriate person who can. When individuals are stressed they may demonstrate poor concentration and may not remember information provided to them; therefore, it is important to ensure that information is repeated whenever necessary and/or provided in written format as available and in the required language (Fortinash & Holoday Worret 2008; Happell et al 2008).

ADMITTING THE CLIENT TO THE MENTAL HEALTH UNIT

When a client arrives to a mental health unit it can often be under duress, resulting in distress and, more frequently, anger. Individuals presenting to a mental health unit can be scheduled as ‘voluntary’ or ‘involuntary’ (see Ch 37). The initial reception of a client to the mental health unit is an opportunity for the nurse to commence the foundations for developing a therapeutic relationship. The therapeutic relationship in the mental health setting is an imperative aspect of nursing, and its development and maintenance has significant impacts on outcomes.

As with the admission of any client, the nurse should demonstrate an empathetic manner, validate the client’s distress at being detained involuntarily and adopt a warm and sensitive approach (Elder et al 2009; Fortinash & Holoday Worret 2008). Care and sensitivity should be taken when discussing the legalities of an involuntary admission; the client should be informed of their rights and the avenues of appeal. Care should also be taken when liaising with family or significant others. Consent must be obtained by the client prior to sharing information with family, and obviously this can result in significant distress when clients do not want concerned family members to be informed of their treatment (Elder et al 2009). Mental health nurses must maintain their client’s wishes, while acknowledging the distress close family and friends are often experiencing at being uninformed. Mental health nurses must also be cognisant of the potential for their client to engage in self-harming behaviours, and consequently remove any potentially dangerous items (see Clinical Interest Box 19.1).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 19.1 Clinical risk factors when admitting the client to the mental health unit

• Orientation to room and unit, including communal areas, toileting/showering facilities, kitchen and laundry areas, telephone

• Introduction to all other clients (particularly those sharing a room)

• Introduction to medical, nursing, interdisciplinary staff

• Information regarding meal times; medication times; community meetings; group sessions and basic unit routines (including curfew if applicable)

• Search and documentation of belongings (for clients with potential to harm self or others)

• Removal and documentation of valuables to units safe

• Removal of sharp items (razors, mirror, glass, scissors etc)

• Removal of potential other self-harming items (belts, stockings, tracksuit cords/ties, shoe laces, electrical cords)

(Elder et al 2008; Keltner et al 2011)

ADMITTING A CHILD TO A HEALTHCARE FACILITY

When a child has a condition that requires hospitalisation the nurse should understand the effects of this admission on the child and their parents/carers. Admission to hospital for a child may be elective or an emergency and it is important to understand that an emergency admission to hospital for a child and their parents/carers is often a time of high stress and crisis. In the emergency situation it is imperative that the nurse provides a safe environment for the child and their parents, and that the nurse demonstrates good communication skills and adequate procedure explanations (Moorey 2010). Children in crisis situations will often mirror or mimic their parents’/carer’s emotional responses, so it is imperative that the nurse reassures and comforts parents to alleviate their distress and ultimately that of the child’s (Moorey 2010). It is important that parents and healthcare providers are honest about hospitalisation, and that children are never threatened with an admission as a form of punishment or told they are going on a holiday (Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). From an elective admission perspective, research suggests that children and their parents/carers benefit from pre-admission visits and the provision of detailed leaflets on their procedure prior to admission (O’Shea et al 2010).

Many factors influence the way in which a child and the child’s family react when illness or an injury makes it necessary for the child to be admitted to hospital. These include:

• The age of the child and their cognitive ability

• The degree of preparation the child has been given by parents/carers prior to admission. Children who are emotionally secure usually adapt well if they are provided with a realistic explanation of hospital life, informed of the reason for their admission and reassured that their parents will spend as much time as possible with them. Parents/carers often fail to adequately inform their child about impending hospitalisation and can unintentionally transfer their own fears and anxieties which can result in the admission to hospital as a very frightening and traumatic experience for the child (Chiocca 2011; Hockenberry & Wilson 2011).

• The condition of the child. An acutely ill or severely injured child may not be totally aware of the situation but the parents/carers will be distressed and apprehensive.

• The cultural background of the child. In some cultures there is an extended and very close-knit family pattern and the child who is accustomed to the loving protection and guidance from parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles can be quite devastated and distressed when separated from such an environment (Chiocca 2011). Also the child who is accustomed to a little companionship or family support may find the noise and company of other children welcome, or completely overwhelming.

• The parents’/carers’ reactions to the situation can markedly impact the situation. Emotional outbursts, anxiety and tension are likely to increase feelings of anxiety, insecurity and apprehension in the child. On the contrary, emotionally composed, calm and confident parents/carers will allay their child’s fears by promoting feelings of security (Chiocca 2011; Hockenberry & Wilson 2011).

• The relationship between the healthcare staff and the child’s parents/carers is a very important factor, particularly in the case of an older child, who will relate more readily to nurses who have established rapport with the parents.

It is evident and widely held that the role of the parents/carers during a child’s hospitalisation is important, and parents/carers are often provided unrestricted visiting opportunities, and accommodation facilities as necessary (Chiocca 2011; Hockenberry & Wilson 2011; Young et al 2006). Parents/carers are encouraged to participate in the treatment of their child; however, care should be taken as many parents/carers find this experience anxiety provoking and are confused by blurred or ill-defined roles (Young et al 2006). When a parent/carer is restricted from spending time with their ill child due to home commitments, economic or travelling issues, they should be referred to the hospital’s social worker with a view to arranging help.

Preparation for admission

Research suggests that preparation is the key to children accepting hospitalisation as reality (Moorey 2010; Murphy-Taylor 1999; O’Shea et al 2010; Stone & Glasper 1997). While difficulty lies in explaining hospitalisation to infants, children from the age of 2 years can be helped to adjust to hospitalisation by means of adequate preparation through use of drawings and role playing with dolls or their favourite soft toy (Chiocca 2011; Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). Many hospitals have independently published posters, books, DVDs and computer games in order to educate children (and their parents) on the likely procedures and processes of their impending hospital stay, and these tools in conjunction with adequate explanations can enhance understanding (The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne 2005). Preparation is directed towards overcoming fears and anxieties, such as the fear of:

The process of preparing for admission includes explaining to the child what will happen to them in age-appropriate, meaningful language. Parents/carers should encourage their child to discuss all aspects of hospitalisation to help overcome any fears and anxieties. Many hospitals now encourage visits to the ward before admission so that the child can see the area and meet some of the personnel who will be involved in their care. Many hospitals with children’s facilities also offer ‘practice’ opportunities prior to procedures, for treatments such as CT scans and MRIs where remaining motionless in a noisy area is imperative. Another way of preparing children prior to hospitalisation is to allow them to pack their own belongings such as favourite pyjamas and teddy in readiness for the trip.

Parents/carers are likely to also experience fear and anxiety when their child is to be admitted to hospital (Moorey 2010). They can be helped to overcome this anxiety if they are provided with information about their child’s condition, aspects of their hospitalisation and given an opportunity to ventilate any fears that they have. The emphasis on parental involvement and family-centred care can do much to relieve anxiety. Parents/carers should be informed of the facilities available should they wish to stay with their child and be provided with opportunities to participate in their child’s care.

In an emergency admission there is no time to prepare the child or parents and the event can therefore be very traumatic for both (Moorey 2010). Encouraging one or both parents to stay as long as possible can reduce some of the child’s fears and anxieties (Chiocca 2011; Hockenberry & Wilson 2011; Moorey 2010).

Many children go through various phases of disturbance when they are hospitalised, particularly if they are separated from their parents. During the initial phase, that of protest, the child may cry or scream for their parents and refuse the attention of anyone else (Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). It is not unusual for the child to stop protesting only when physically exhausted. During the second stage, that of despair, the crying generally subsides and the child may become withdrawn and apathetic (Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). The child may feel abandoned and experience feelings of hopelessness and grief. During the third stage, that of detachment, the child appears to have adjusted to the separation but in reality the child is detaching from the parents in an attempt to escape the pain and wishing they were there (Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). When the parents do visit, the child may react with disinterest and, unless the parents understand these reactions, they may become very distressed. In order to provide an appropriate response, it is important that nurses are familiar with separation anxiety issues and accept that a portion of their time will be directed towards settling the child and helping the parents adjust to the reality of hospitalisation.

Admission

Understandably an admission, either emergency or elective, can be frightening and distressing for the child and their family. Given that many children respond to their parents’ emotional reactions with fear and apprehension, it is imperative that the nurse develops a rapport with parents/carers and gains their confidence from the time of admission (Moorey 2010). This will reassure the child, and likely calm a potentially distressing situation. Research shows that children experience fears and concerns regarding pain, mutilation, parental separation, immobility and loss of control (Coyne 2006a). The nurse has a crucial role to play in alleviating some of this distress.

Prior to admission, the nurse in charge of the unit assigns a room based on the child’s age and diagnosis. Some hospitals’ paediatric units have age-segregated rooms or units (including adolescent units), while others, where possible, keep infants together to ensure older children can rest without interruption. Other children in the unit will be informed of the pending arrival so that they can be welcomed. Like any other admission, the room should be appropriately prepared with any necessary equipment prior to the child’s arrival, as this ensures the nurse will not have to leave the child to gather items.

The admission procedure may vary slightly between hospitals, depending on hospital policy and the prevailing circumstances. The child should have their vital signs assessed, height and weight recorded, identity bands placed on their wrist and/or ankle (or pinned on their clothing if they become upset by this) and urinalysis done if required. The child and their family should also be orientated to the facilities on the unit, including call bells, bed controls, television and radio remotes, telephone and toileting facilities. The child and their family should also be shown the playroom, dining areas and the parents should be provided with details about rooming-in facilities.

During the admission, the parents/carers are encouraged to remain with the child and to assist with activities such as undressing and settling at night. The functions of equipment should be explained and, where appropriate, the child should be encouraged to handle some equipment with supervision, to allay fears. Children and their parents/carers are likely to adapt better if they are informed in advance of the possibility of treatments involving the use of intravenous therapy equipment, drainage tubes, dressings, plasters or oxygen apparatus. Like adults, children benefit from participating in the decision-making process, and therefore the nurse should adopt a collaborative and inclusive approach to care (Coyne 2006b).

General aspects of paediatric nursing

Care of children differs from the care of adults in many ways; for example, the inability of very young children to communicate necessitates special skills of observation and interpretation. While each child must be treated as an individual, there are certain aspects of care which apply to all children:

• Complete honesty is important. Age-appropriate explanations should be given prior to any procedure. The nurse should not tell a child that a procedure will not hurt if, in fact, it is likely to cause pain; however, the nurse should avoid generating gratuitous concern and distress (Engel 2006; Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). The nurse should be patient and anticipate that for some children, becoming ‘ready’ for the procedure may take time.

• The nurse should recognise the child’s need for love and a feeling of security. Should the parents/carers be unable to be present all the time, the nurse should ensure the child receives extra time and affectionate support.

• Continuity of care is important; therefore, where possible, the same nurse should care for the child during hospitalisation. Attempts should be made to maintain a routine similar to the one the child is accustomed to at home. A similar routine makes hospital life less bewildering for a child and promotes a feeling of security.

• Efforts should be made to minimise a hospital-type environment, for example, by encouraging the child to wear their own clothes, to sit at a table for meals and by parents providing personal effects such as toys and photographs.

• Encourage discussions on family, pets, friends and school in an attempt to lessen feelings of separation. If parents cannot be with the child all the time, it is sometimes helpful if they leave small presents for the child to open each day. School friends and siblings should be encouraged to visit.

• Always attempt to maintain the child’s dignity and independence after establishing the parameters with their parents. Developmental regression can be distressing for both the child and the parents/carers and can be exacerbated by hospitalisation.

• Allow for periods of regression during hospitalisation and recognise that regressive behaviour is a feature of illness. Given that regression is exacerbated by stress and hospitalisation is a known cause of stress, it is not uncommon for children to experience regression (Hockenberry & Wilson 2011; Young et al 2006). For example, a previously toilet-trained child may begin bed-wetting while in hospital.

• The provision of opportunities for play is very important in paediatric units. ‘Play’ is a concept whereby children engage in creative activities of an exploratory nature that are fun, where they interact with their environment in a safe and unpredictable manner (Stagnitti 2004). Within the hospital environment, play can provide opportunities to reduce anxiety, ensure skill retention and enhancement, provide a diversion and therefore reduce feelings of homesickness and increase empowerment (Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). Children should have access to age-appropriate and safe toys and games in an appropriately supervised environment. Many hospitals now provide children opportunities to play with DVDs and game consoles, to be visited by play and music therapists and, for those with longer-term hospitalisations, to be provided with school programs. Some charitable organisations also fund activities such as clowns, and excursions off the hospital site.

• Provide an atmosphere and opportunities that encourage free expression of feelings by the child and parents.

• Discharge preparation involves providing the parents/carers and child with information about medication or other forms of treatment, postoperative or wound care and follow-up appointments with their doctor or community nurse. It is important to explain to parents/carers that children may experience behavioural disruptions upon returning home such as sleep disturbances, difficulties at school or regressive behaviours (Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). The prevalence of home hospital care has seen an increase in the degree of medical technology used to treat ill individuals in the comfort of their home. Should a child be discharged with intravenous medications, oxygen or other medical treatment, parents/carers should be educated to use this equipment, given opportunities to practise and provided with a contact telephone number should they need advice (Hockenberry & Wilson 2011).

ADMITTING AN ADOLESCENT TO A HEALTHCARE FACILITY

Adolescence is an important stage of development during which the individual transitions from childhood, enhancing their maturity both physically and emotionally; it is characterised by the appearance of secondary sex characteristics and eventually a cessation of body growth (Chiocca 2011; Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). (More information on growth and development during adolescence is provided in Chs 11 and 12.) When an adolescent requires hospitalisation, the most appropriate and beneficial environment is one which is specifically designed to cater for their needs. Every effort should be made to accommodate hospitalised adolescents in age-appropriate and, where available, gender specific units and rooms.

Collaboration in care is a vital process in empowering the adolescent in decision making, and is adopted in conjunction with promoting independence and autonomy (Chiocca 2011; Hockenberry & Wilson 2011; Kelly 2007; O’Toole 2008).

In Australia and New Zealand, accidents are the leading cause of death and injury in adolescence. They are largely the result of a tendency to risk-taking behaviours in conjunction with feelings of indestructibility (Crisp & Taylor 2009). The nurse has the opportunity to provide health-promoting education regarding risk-taking behaviours, in a non-judgmental and non-authoritarian manner.

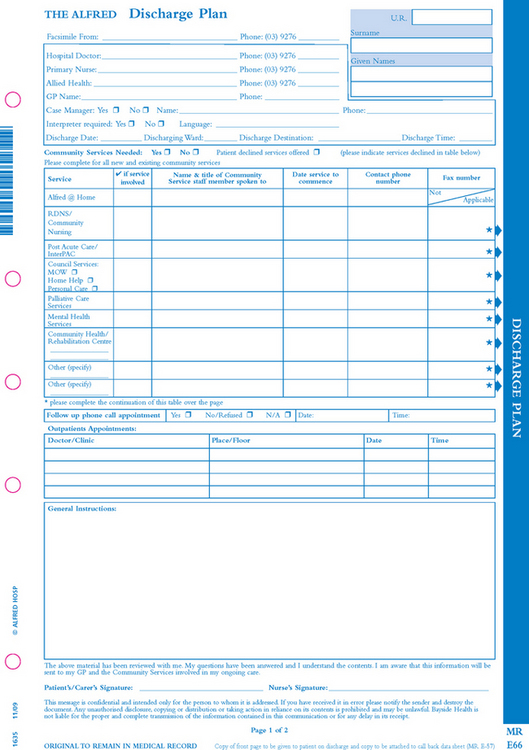

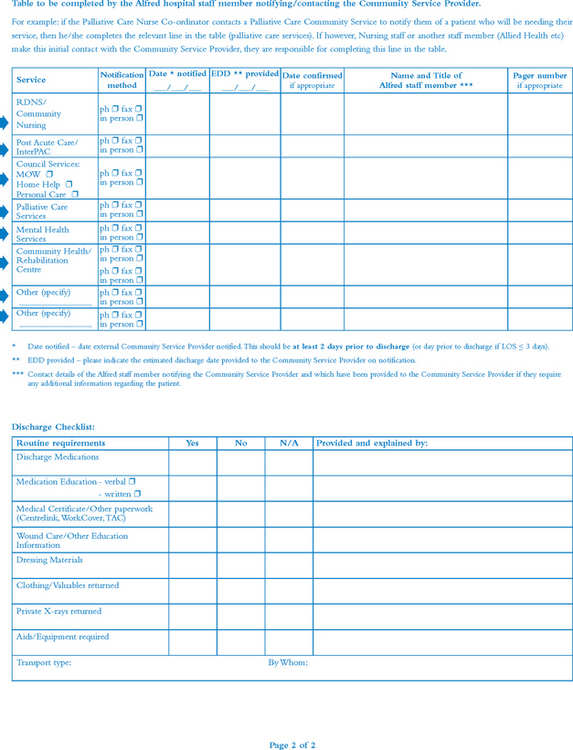

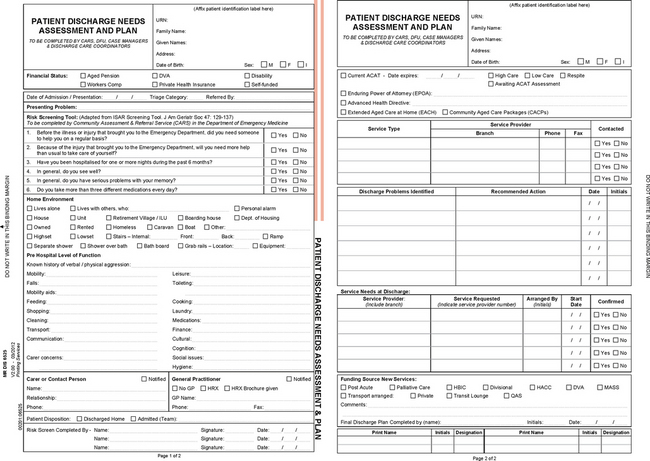

DISCHARGE PLANNING

There are a number of key elements to discharge planning, namely collaboration with the client, efficient communication, prompt assessment of potential interventions needed at home and an interdisciplinary approach (Day et al 2009; Goodman 2010). Ideally, discharge planning should commence at a pre-admission clinic or as soon as the client is admitted to hospital and may involve carers or significant others who will be involved with the client after discharge (Goodman 2010; Kralik & van Loon 2011). The purpose of discharge planning is to assist the client to make a smooth transition from one setting or level of care to another without impeding the progress already achieved. By adopting a holistic, interdisciplinary approach the nurse can utilise the diversity of skills in the team, resulting in a positive outcome for the client (Kralik & van Loon 2011). While many clients are discharged to their home, some move onto long-term rehabilitative settings, nursing homes or palliation. Community services such as Meals on Wheels, community day centres, home cleaners and district nurses all allow the transition from hospital to home to flow smoothly. It is important to acknowledge that client outcomes are improved when the discharge process is commenced promptly and efficiently, is inclusive of the client and their wishes and provides appropriate follow-up at home, in the form of telephone support or postoperative counselling (Kralik & van Loon 2011). Effective discharge planning is also associated with a decrease in readmission rates, a reduction in the length of hospital stays and a reduction in the degree of follow-up community care (Kralik & van Loon 2011).

Discharge planning should adopt a team approach and should be family inclusive, ensuring the involvement of the client, medical officers, nurses and other member of the interdisciplinary team; for example, occupational therapist, dietitian, psychologist and social worker (Kralik & van Loon 2011). Clinical Interest Box 19.2 outlines the elements on a discharge form.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 19.2 Elements of a written discharge summary form

• Mode of discharge: ambulatory, wheelchair, stretcher

• Client instructions for self-care activities: medications, diet, food–drug interactions, wound care, self-catheterisation, pain management, tracheostomy care and treatments

• Signs, symptoms and actions to be taken regarding complications or drug reactions

• Permissible activities: e.g. lifting, driving

• Correct settings for required equipment

• Follow-up instructions and appointments

• Health-promoting education and interventions

• Explanation of emergency procedures in meaningful language and/or print

• Client’s signature, acknowledging understanding of instructions

Steps involved in discharge planning are:

• Assessing the client and their significant others

• Interpreting data to identify specific needs and targeting those needs

• Planning to meet those needs

• Evaluating the discharge planning process and the results (Fig 19.3).

Preparing clients to go home

Nurses preparing the client to go home need to assess:

• The client’s personal and health data

• The client’s ability to safely perform the activities of daily living

• Any physical, cognitive or other functional limitations the client may have

• Carers’ responses and abilities

• Adequacy of client’s financial resources

• Hazards or barriers that the home environment presents (e.g. stairs, no shower)

The following outcomes must be evaluated for a client’s discharge plan (Fig 19.4):

• Can the client and family, if appropriate, explain the diagnosis and the safe and effective use of discharge medication?

• What specialist instruction or training is required for the client and family to be able to provide proper care after discharge?

• What community support systems need to be coordinated to enable the client to return home safely?

• Are there any physical barriers to returning home (e.g. stairs)?

• Are the client and family able to cope with the client’s health status?

• Is relocation of the client, coordination of support systems or transfer to another healthcare facility needed?

Clinical Interest Box 19.3 outlines home assessment parameters that need to be considered before discharging a client home.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 19.3 Discharge planning—home assessment parameters

Age, gender, height and weight, cultural data (religion), medical history, current health status, surgery

Abilities to perform activities of daily living (ADLs)

Abilities for dressing, eating, toileting, bathing (bath, shower, sponge), ambulating (with or without aids such as a cane, crutches, walker, wheelchair), transferring (from bed to chair, in and out of bath, in and out of car), meal preparation, transportation, shopping and the impact medications may have on completing these safely

Sensory losses (auditory, visual, tactile), motor losses (paralysis, amputation), communication disorder (aphasia), mental confusion or depression, incontinence

Principal carer’s relationship to client, thoughts and feelings about client’s discharge, expectations for recovery, health and coping abilities, comfort with performing required care

Financial resources and needs (note equipment, supplies, medications, special foods required), impact of unemployment on financial situation

Family members, friends, neighbours, volunteers, religious affiliations, resources such as nutrition services, health centres, community health nurses, day programs, specific interest groups (e.g. MS support groups, or local diabetes support groups) legal assistance, home care (cooking, cleaning), respite care

Safety precautions (stairs with or without handrails; lighting in rooms, hallways and stairways; nightlights in hallways or bathroom; grab bars near toilet and bath; firmly attached carpets and rugs), self-care barriers (lack of running water, lack of wheelchair access to bathroom or home, lack of space for required equipment, lack of elevator)

Need for healthcare assistance

Home-delivered meals; special dietary needs; volunteers for telephone reassurance, friendly visiting, transportation, shopping; assistance with bathing; assistance with housekeeping; assistance with wound care, ostomies, tubes, oxygen therapy, intravenous medication

Teaching as a part of discharge planning

The goal is to provide clients and families with the knowledge and skills required to meet ongoing health needs. It is difficult to provide clients with information they need the evening before or the morning of discharge. Before beginning to teach you must determine what information has already been given by the medical officer or other carers. A useful way of determining a client’s degree of understanding is to ask them to describe what they believe they are to do when they return home. Any discrepancies can then be identified and the nurse can work with the client to ensure that they are aware of this information prior to discharge. It is important that the nurse be cognisant of any potential barriers to communication or learning issues that may disrupt the client from understanding their discharge needs (see Clinical Interest Box 19.4). In particular, language barriers must be addressed with interpreters and/or written instructions in the required language. It is important that the client is provided with a medically trained interpreter, and not a family member. There are a number of reasons for this, namely issues pertaining to confidentiality and ensuring medical information is passed on correctly (Berman et al 2012; Johnstone 2009; O’Toole 2008). Given that clients from ethnically and linguistically diverse backgrounds have a higher likelihood of medication mismanagement than clients from the dominant culture, it is very important that they understand messages clearly and that nurses make every effort to ensure this happens (Kralik & van Loon 2011).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 19.4 Client risk factors for discharge planning

• Lack of understanding/knowledge of treatment plan

• Newly diagnosed chronic disease

• More than three active medical problems

• Emotional or mental instability

• Takes more than five medications

• Lack of available or approximate referral sources

• Culturally or linguistically diverse background

• Being bedridden for long periods

• Readmission to hospital within 2 weeks of discharge

• Poor family supports (lives alone)

Learning will be enhanced if spoken instructions are reinforced with materials in other formats such as DVDs, booklets and discussions, which can be used in conjunction with community support groups and internet forums. The nurse should document any instruction that is given to a client. After a family has learned how to perform any necessary carer skills, have them assume care before the client returns home. Many hospitals require family members to manage care before the client is discharged home (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Day of discharge

When the date and time of discharge have been determined, the client and significant others are informed, preferably the day before. Transport should be arranged in the form of a taxi, or a patient transport ambulance, if necessary. Before the client leaves the healthcare facility the nurse should check that:

• The medical officer’s discharge orders for prescriptions, changes in treatment or the need for special equipment have been organised

• Dismissal summary containing information pertaining to reason for admission, significant findings and results has been done

• All personal possessions have been collected and packed, including any items of value being held in the facility’s safe

• The client is assisted to dress, if necessary

• Any dressings or bandages have been applied as necessary

• Intravenous cannula has been removed

• The client is provided with any prescribed medications together with instructions for their administration. The healthcare facility generally provides an instruction/information sheet that includes this

• The client is aware of, and understands, any dietary or activity restrictions, including driving

• Reference material on their condition, or direction on how to access this has been provided

• The visiting nurse service has been notified, if necessary

• The client is aware of any follow-up appointments including referrals, if necessary

• The client is confident about performing any self-care activities that have been taught, such as administering insulin, dressing a wound or caring for a colostomy

• The client and significant others are provided with contact details should there be any problems after discharge (Berman et al 2012; Crisp & Taylor 2009; Day et al 2009; Goodman 2010; Kralik & van Loon 2011; Rose & Haugen 2010).

When the client is ready to leave the unit they are escorted to the discharge department and any documentation (usually health-insurance related) is completed. The client is then escorted to the exit. In the unit, the nurse reports to the nurse in charge and documents that the discharge has been completed.

Research (Hickman et al 2007) suggests that older persons are particularly vulnerable in the first few weeks postdischarge; therefore, it is of paramount importance that the discharge planning process is managed effectively to prevent readmissions and poor clinical outcomes for this age group.

Discharging the mental health client

The day of discharge for the client from the mental health unit is often one which fills the client with happiness, yet is often met with trepidation and apprehension from the family or carer. There are many considerations made when discharging clients from the mental health unit; importantly, bed shortages have seen an increase in discharge acuity levels (Elder et al 2009; Happell et al 2008). As in other areas of healthcare, discharge planning should commence from the time of admission (Elder et al 2009). While every effort should be made to adopt a collaborative approach to organising discharge, with the client heavily involved—with consent—it is highly beneficial for families and carers to also be involved in this process (see Clinical Interest Box 19.5 and Clinical Scenario Box 19.3). The burden of care for families with a mentally unwell loved one is very significant. Sensitivity and empathy should be adopted when liaising with families and support services, and resources should be provided for them. In particular, carers (with the client’s consent) should be provided with emergency crisis contact details, case manager details and treatment regimen information. All belongings should be returned to the client, paperwork signed by the treating psychiatrist and, if necessary, transportation arranged. Should the client be discharged on a community treatment order, copies of this containing any provisions and further contact details (of case manager, general practitioner and treating psychiatrist) and review dates should be included. Where possible, a meeting between the community treating team, family and client is useful prior to discharge.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 19.5 Discharge considerations in mental health

• Adherence to medication and treatment regimen

• Potential for relapse or exacerbation of psychiatric symptomatology

• Commencement of disability support pension as necessary

• Housing (homelessness, housing affordability)

• Potential for harm to self/others

• Degree of insight into their illness and need for ongoing treatment

• Ability to identify future stressors and how this may exacerbate their illness

• Information regarding community follow-up care, including crisis intervention contacts

Clinical Scenario Box 19.3

Discharging the mental health client

Anthony Collins is a 22-year-old man who was admitted to the mental health unit of his local hospital after a serious decline in his mental health, culminating in an involuntary admission. Anthony’s family and friends have become quite concerned with his behaviour in recent months, particularly his suspicion of others, and an increasing interest in religion. An incident with his mother 3 weeks ago resulted in hospitalisation. Anthony believes that his mother was trying to poison his food, and was very suspicious of her intent.

His friends and lecturers at university, where Anthony was studying business, noticed that he became very preoccupied with themes of a religious nature; namely that the Devil had possessed his mother and he needed to exorcise the demon out of her. Anthony’s deterioration in mental state culminated in him barricading himself in his bedroom, shouting religious passages and threatening to harm his mother. Anthony’s distraught mother phoned the police, and they in turn contacted the Crisis Assessment and Treatment Team (CATT) and Anthony was subsequently hospitalised. A mental state examination identified Anthony had pressured speech, restricted affect and was receiving ideas of reference from the television (see Ch 37).

On admission Anthony believed that God was speaking to him, and that his mother had been possessed by the Devil for a number of months. Anthony was very distressed and frightened, and his appearance was dishevelled and unkempt. Anthony spent 3 weeks in the mental health ward where he engaged with psychiatric nurses and medical practitioners collaboratively, in conjunction with interdisciplinary team members in an effort to stabilise his illness. While Anthony has made some progress, he remains very unwell, has poor insight in to his illness, remains suspicious at times and is reluctant to take antipsychotic medication.

Anthony is due to be discharged today. Anthony’s mother has said he can return home, but she admits to feeling ‘very worried’ about the prospect of relapse. Anthony has a follow-up appointment with his psychiatrist in one week and his CATT case manager will visit him tomorrow to give him his antipsychotic medication. The social worker at the hospital has applied for a disability support pension on Anthony’s behalf and she is looking into accommodation. With Anthony’s permission, the university has been contacted and he is meeting with his lecturers to discuss an intermission to his studies. Anthony has also been put in contact with student services. Anthony’s mother has been given 24-hour crisis intervention telephone numbers and some counselling as to what to do in the event of an emergency. Anthony’s case manager has also suggested that his mother attend a group for families affected by mental illness in loved ones. This will give her the opportunity to discuss her fears and anxiety regarding her son’s illness. For this family, Anthony’s diagnosis is the beginning of an often frightening and confronting journey where the likelihood of relapse is significant.

Discharge against medical advice

A client may at any time decide to leave a healthcare facility against the advice of the medical officer and nursing staff. Should this occur, the nurse must immediately report the incident to the nurse in charge and notify the client’s medical practitioner promptly. If the client cannot be dissuaded from leaving, they are asked to sign a statement to the effect that they are leaving at their own risk and that they are responsible for the consequences. If the client refuses to sign, this must be documented in their clinical file. The document is signed by at least one witness; this may be the medical officer or the nurse in charge. Given that self-discharge accounts for about 2% of hospital discharges overall, it is important to consider the reasons why clients leave against medical advice, in an effort to identify those clients potentially at risk (Alfandre 2009). Statistically, young males without health insurance who misuse substances, have no regular general practitioner and are from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to discharge themselves from hospital against advice (Alfandre 2009) (Clinical Interest Box 19.6).

Transfer

Sometimes it is necessary to transfer a client from one unit at a healthcare facility to another unit, or to an entirely different facility. Transfer of a client may be necessary for a variety of reasons, such as change in condition, utilisation of private health insurance, demand for available beds or the requirement to be isolated from others. Regardless of the reasons, a transfer may be a distressing experience for the client, who is likely to feel apprehensive about the need to adapt to new surroundings and personnel. The client may also be worried about the impacts on their family, particularly if the new service is a greater distance from home. Conversely, the transfer may be welcomed as an indication of an improvement in the client’s condition, or an improvement in facilities available; for example, being transferred to a general ward from intensive care, or from a public hospital with shared accommodation to a private hospital with their own room. It is important to acknowledge that being transferred to rehabilitation, palliation or a long-term facility can be confusing and frightening for clients. Whenever possible, have family or a close friend travel with the client or meet them when they arrive at the new facility.

As with discharge, when a client is to be transferred it is essential that they and their significant others are informed as soon as possible. A full explanation of the reasons for the transfer provides the person with time to adjust and provides their significant others time to make any changes necessary. In addition to preparing the client for the transfer, it is necessary to inform the staff in the receiving unit or facility of the client’s condition and care plan. Arrangements for transportation are made if necessary. Key aspects involved in transfer are:

• Informing the client and significant others of the date and time the transfer is to occur

• Assessing whether the client is able to walk or if a wheelchair or trolley is necessary

• Arranging transportation, e.g. an ambulance, if being transferred to another facility

• Notifying the receiving unit or facility of the date and expected time of the transfer

• Notifying admissions department of the transfer

• Assisting the person to pack all personal possessions, including valuables stowed in the safe. The nurse should check the entire room to ensure nothing is left behind

• Assembling the documents that are to accompany the client

• Sending medications with the client or returning them to the facilities pharmacy department

• Accompanying the client to the receiving unit, the ambulance or private care

• Introducing the client to the nursing staff in the receiving unit and remaining with them until the staff have received the client into their care

• Reporting to the nurse in charge and documenting that the transfer has been accomplished (Fig 19.5 overleaf).

Summary

Admission to a healthcare facility, whether by means of an elective or emergency presentation, is a major event for an individual and their significant others. Both the client and their significant others are often anxious about the admission and the implications surrounding this (e.g. emotional, financial). An individual may react to admission in one or more ways, including apprehension, relief, irritability, anger or depression. It is therefore important that the nurse perform the admission in an empathetic, caring and sensitive manner.

Prior to receiving the client onto the unit, the nurse must prepare the room. Reception of the individual is directed towards verifying the client’s identity, assessing the physical and psychological status, promoting the client’s comfort in an unfamiliar environment and providing items needed for care. It is also important that the nurse provide both written and verbal information to the client in meaningful language.

The challenges associated with admitting and discharging the client from the mental health unit are unique and must be addressed in a sensitive and empathetic manner. It is important, where possible and with consent, to involve family and significant others to ensure the best possible outcomes are achieved for the mental health client with potentially complex issues. Safety is of paramount importance.

The client may be transferred to another unit or healthcare facility and a full explanation as to the reasons for this is necessary for the client and their significant others. Discharge planning, which begins immediately upon admission (or in the event of elective procedures, prior to it), is directed towards assisting the individual to make a smooth transition from one setting to another. Discharge planning involves assessment, analysis of data planning, implementation and evaluation.

1. Thirteen-year-old Jess has been admitted to the adolescent ward for an exacerbation of asthma. It becomes apparent that Jess has not been taking her preventer medications. What is the nurse’s role in health promotion and education for Jess, and what approach might the nurse take?

2. What would you say to make an anxious client and their family more relaxed during admission?

3. Mr Braddon, aged 77, is about to be discharged from the medical ward after a hip replacement. On assessment, you discover that Mr Braddon is single and lives alone in a two-storey townhouse. He has trouble making meals for himself. What do you need to consider before discharging Mr Braddon, and which community and interdisciplinary services might be involved?

1. How would you plan and implement the care for the client who requires admission, transfer or discharge?

2. How can you ensure a successful paediatric admission?

3. What are the responsibilities of the nurse in relation to assessment and observation of children?

4. What are the key elements of discharge planning?

5. How can the nurse avert some of the issues regarding risk factors for discharge?

6. What safety considerations must be taken when admitting the client to a mental health unit?

7. Discuss the effects of hospitalisation in relation to clients and stress.

References and Recommended Reading

Alfandre DJ. ‘I’m going home’: Discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2009;84(3):255–260.

Berman A, Snyder S, Kozier B, et al. 2nd edn. Kozier and Erb’s Fundamentals of Nursing, Pearson, Frenchs Forest, NSW, 2012;Vol 2.

Chang S-H, Chiu YH, Liou I-P. Risks for unplanned hospital readmission in a teaching hospital in southern Taiwan. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2003;9:389–395.

Chiocca EM. Advanced Pediatric Assessment. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

Coyne I. Children’s experiences of hospitalisation. Journal of Child Health Care. 2006;10(4):326–336.

Coyne I. Consultation with children in hospital: children, parents’ and nurses’ perspectives. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2006;15:61–71.

Crisp J, Taylor C. Potter & Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 3rd edn., Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

Day MR, McCarthy G, Coffey A. Discharge planning: the role of the discharge co-ordinator. Nursing Older People. 2009;21(1):26–31.

DeLaune SC, Ladner PK. Fundamentals of Nursing—Standards & Practice, 3rd edn. Canada: Thomson Delmar Learning, 2006.

Elder R, Evans K, Nizette D. Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2nd edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

Engel JK. Mosby’s Pocket Guide to Pediatric Assessment, 5th edn. USA: Mosby-Elsevier, 2006.

Ebersole P, Hess P, Touhy TS, et al. Toward Healthy Ageing, 7th edn. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

Fontaine KL. Mental Health Nursing, 6th edn. NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009.

Fontaine KL, Fletcher S. Mental Health Nursing. NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002.

Fortinash KM, Holoday Worret PA. Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing, 4th edn. Canada: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

Giangiulio M, Aurilio L, Baker P, et al. Initiation and evaluation of an admission, discharge, transfer (ADT) nursing program in a paediatric setting. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2008;31:61–70.

Goodman H. Discharge from hospital: The importance of planning. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2010;5(6):274–279.

Happell B, Cowin L, Roper C, et al. Introducing Mental Health Nursing: A Consumer-Oriented Approach. Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2008.

Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D. Wong’s Nursing Care of Infants and Children, 9th edn. Canada: Mosby-Elsevier, 2011.

Hickman L, Newton P, Halcomb EJ, et al. Best practice interventions to improve the management of older people in acute are settings: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;60(2):113–126.

Hitchcock JE, Shubert PE. Community Health Nursing: Caring in Action. New York: Thomas Delmar Learning, 2002.

Jarvis C. Physical Examination & Health Assessment, 5th edn. Canada: Saunders Elsevier, 2008.

Johnstone M-J. Bioethics: A Nursing Perspective, 5th edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

Kelly MT. Achieving family-centred care: working on or working with stakeholders. Neonatal, Paediatric and Child Health Nursing. 2007;10(3):4–11.

Keltner NL, Bostrom CE, McGuinness TM. Psychiatric Nursing, 6th edn. USA: Mosby Elsevier, 2011.

Kralik D, van Loon A. Community Nursing in Australia, 2nd edn. Milton, Qld: Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Kring AM, Johnson SL, Davison GC, et al. Abnormal Psychology, 11th edn. USA: Wiley, 2010.

Lees L, Dyer P. Why patients self-discharge. Nursing Management. 2008;15(2):22–27.

Mitchell M. Psychological care of patients undergoing elective surgery. Nursing Standard. 2007;21(30):48–55.

Moorey S. Unplanned hospital admission: Supporting children, young people and their families. Paediatric Nursing. 2010;22(10):20–23.

Murphy-Taylor C. The benefits of preparing children and parents for day surgery. British Journal of Nursing. 1999;8(12):801–804.

Norman G. Moving beyond good intentions: making collaborative care a successful reality. American Health & Drug Benefits. 2010;3(6):383–385.

O’shea M, Cummins A, Kelleher A. Setting up pre-admission visits for children undergoing day surgery: a practice development initiative. British Journal of Paediatric Nursing. 2010;20(6):203–206.

O’Toole G. Communication: Core interpersonal skills for health professionals. Sydney: Elsevier, 2008.