CHAPTER 17 General health assessment

At completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to

• Identify the purposes of undertaking a health assessment

• Identify the expected outcomes of a health assessment

• Describe the techniques used with each assessment skill

• Identify information from the nursing history before performing a physical assessment

• Document assessment findings appropriately

• Understand the importance of information gathered during assessment in clinical handover

Obtaining a general health assessment is vital to managing comprehensive nursing care. It is performed primarily on admission to a healthcare facility. This assessment involves a detailed review of the client’s condition, with the nurse collecting a nursing history and performing a behavioural and physical examination. Periodic assessments are performed on a regular basis throughout the shift and when there is an event that may change the client’s condition. Effective assessment skills can facilitate the identification of new signs and symptoms that indicate complications of an illness or adverse reaction. One of the main tasks of nurses in the provision of client-centred nursing care is recognition of normal and abnormal signs and symptoms in assessment, intervention and evaluation of individual health and functional status (ANMC 2002).

A client was admitted to the medical ward for symptoms of insect bite on the right leg. The leg was swollen, red and tender. As the nurse assigned to care for the client, I entered the room to take the vital signs as routine for a new admission. However, I was so focused on managing his infected leg that I failed to notice that the client was actually diaphoretic and flushed as a result of an adverse reaction to a drug given at the Emergency Department.

GUIDELINES FOR CONDUCTING A GENERAL HEALTH ASSESSMENT

Conducting a general health assessment allows nurses to be engaged with their clients. By engaging, nurses are able to establish baseline responses of their clients to physical and psychosocial needs such that when there is an altered response or a deviation from the baseline, appropriate nursing measures can be established by applying clinical judgment (Phaneuf 2008).

General health assessments need to include overall health status, detailed health history and physical examination, using a holistic approach. When commencing a general health assessment the nurse should:

• Set priorities for assessment based on a client’s presenting signs and symptoms

• Use a head-to-toe approach, as this facilitates an effective assessment

• Engage the client by allowing active participation in the assessment process

• Record quick notes to facilitate accurate documentation

• Integrate health promotion and education into physical assessment activities

• Consider the cultural background of the client (see Table 17.1).

Table 17.1 Cultural considerations in health assessment

Centre for Culture, Ethnicity & Health

Zambas (2010) suggests that a systematic approach to assessment does not necessarily involve a formal assessment each time. In fact, every encounter a nurse has with the client is an opportunity for assessment of physiological functioning and coping. These forms of assessments can be done while the nurse is administering medication; helping the client to change position in bed; assisting with toileting and shower or at any other times the nurse observes the client during the course of the shift. Continued assessments encourage a client-centred approach and thus help to reduce incidences of adverse events.

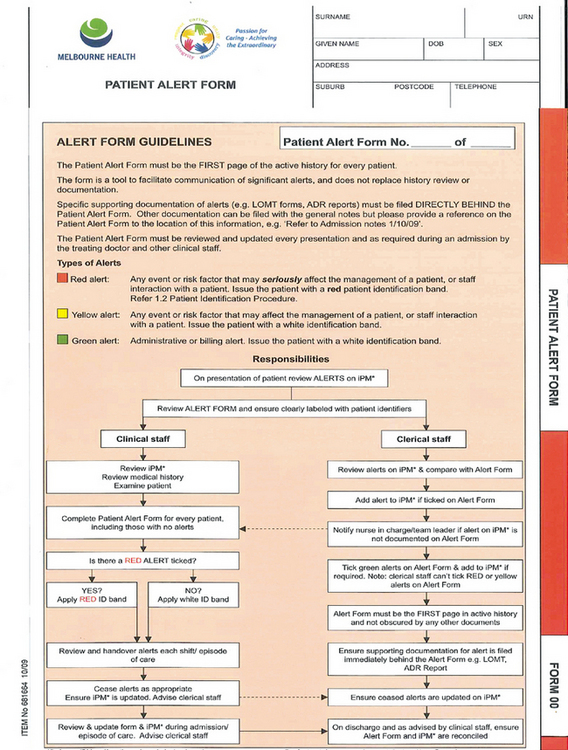

General health assessments conducted at the Emergency Department are brief so that the information gathered can effectively rule out differential diagnosis and quickly allow appropriate nursing measures to be taken. On the other hand, assessments performed for an admission need to include a comprehensive set of client information so that nurses can plan for actual as well as potential nursing interventions for the length of the hospitalisation (see Fig 17.1).

General assessment

A general assessment includes the following steps (Crisp & Taylor 2009):

• Assess the client’s responses

• Review baseline vital signs (see Ch 18 for vital signs)

• Review the client’s fluid intake and output

• Assess posture and position and body movements

• Observe hygiene and grooming:

• Inspect the nose externally for shape, skin colour, alignment and presence of deformity or inflammation. Note the colour of the mucosa and any lesions, discharge, swelling or presence of bleeding

• In clients with nasogastric tubes, inspect the nares for excoriation or inflammation

• Assess the mouth, inspect the oral mucosa, tongue, teeth and gums for hydration; determine whether the client wears dentures

• Inspect the skin surfaces, comparing the skin colour of symmetrical body parts

• Inspect the character of any secretions: note colour, odour, amount and consistency

• Assess the condition of the skin for pressure areas

• Assess consciousness, feelings and emotional status

• Observe the client’s interaction with their spouse or partner, older adult child or carer

Focused assessment

Sometimes a more focused assessment may be necessary. Focused assessments are used to observe and monitor systems-related complications. For example, if a client suddenly presents with lowered conscious status, the nurse needs to pay close attention to the immediate assessment of the neurological status in order to plan appropriate interventions. These assessments are usually initiated by identifying and responding to an acute onset of the client’s symptoms. Even when a focused assessment is performed, it is still important to look at the entire client presentation. This is because a problem in one body system will affect or be affected by another body system. So it is important to observe from head to toe and note any changes in other body systems.

Physical assessment

A physical assessment of a client in a healthcare facility is obtained to (Crisp & Taylor 2009):

• Gather baseline data about the client’s health

• Supplement, confirm or refute data obtained in the nursing history

• Confirm and identify nursing diagnoses

• Make clinical judgments about a client’s changing health status and management.

A nurse must learn how to really discern a client’s condition so that, even in passing or without conscious effort, clues to client health or ill-health are not missed. This includes being aware of clients and their general appearance, colour, expression and body posture. During closer contact with the client, no significant external feature should escape the nurse’s notice. The nurse must be able to recognise deviations from what is acceptable and usual for the client. To do this the nurse must know what to look for and what constitutes the acceptable and usual for each client.

Observation skills are critical to taking a thorough health history; performing a physical assessment, and relying on these accumulated skills for the interpretation of clinical data (Pellico et al 2009). (See Clinical Interest Box 17.1.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 17.1 Purpose of the systematic physical assessment in everyday practice

A less obvious purpose of the physical assessment but one that is no less important is that of enhancing communication and caring opportunities with the patient. The incorporation of physical assessment into the nurse’s everyday practice brings the nurse to the bedside—touching, observing and communicating with the patient. Physical assessment can provide an opportunity to take the time to be with the patient, an important component in developing a therapeutic relationship (Zambas 2010).

Clients are assessed when they are first admitted to a healthcare institution or when community or home nursing care is initiated. Thereafter, assessment is performed continuously to evaluate client progress and to identify changing needs. Table 17.2 lists the observations to be made during the admission assessment, the acceptable findings and various deviations from the norm.

Table 17.2 I Admission assessment

| Aspect | Normal | Deviations from normal |

|---|---|---|

| General physical appearance | ||

| Skin | ||

| Hair | ||

| Nails | ||

| Eyes | ||

| Ears | ||

| Mouth | ||

| Thorax and lungs | ||

| Abdomen | Slightly convex, symmetrical | Excessively concave, asymmetrical, distended |

| Posture and gait | Able to sit, stand and walk normally | Postural abnormalities, e.g. kyphosis, scoliosis; abnormal gait |

| Mobility | Full range of joint motion | Stiffness or instability of a joint, unusual joint movement, swelling of a joint, pain on movement |

| Muscle tone and strength | Normal tone and strength | Increased or decreased tone, decreased strength |

| Speech | Ability to speak clearly | Speech impairment, e.g. lisp or stammer |

| Mental and emotional status | Appropriate emotional responses | Responses inappropriate, apprehension, anxiety, depression, hostility |

| Level of consciousness and orientation | Alert, responsive, oriented to time, place, person | Disoriented, unresponsive to stimuli, shortened attention span |

| Presence of prosthesis or aids | None, although aids to sight and hearing are common | Spectacles, contact lenses, artificial eye, hearing aids, walking sticks, frames, wheelchairs, artificial limb, dentures |

In addition to the observations listed in this table, the nurse must assess the client’s:

• Ability to perform the activities of daily living

• Ability to interact with others

• Reactions and responses to treatment; for example, medications

• Basic needs; for example, for food, water, oxygen, safety, exercise and comfort

• Specific needs; for example, for wound care or pain relief

• Excretions and secretions; for example, urine, faeces, vomitus, wound drainage.

Information on these topics is provided in the relevant chapters; for example, Chapter 21 addresses comfort needs and Chapter 31 addresses the need for freedom from pain.

Subjective and objective data are included in the assessment of the client. Subjective data are collected by interviewing the client during the nursing history. This includes information that can only be described or verified by the client. Family members and caregivers can also contribute to subjective data about the client. Subjective data are also referred to as symptoms. Objective data are data that can be observed and measured. These types of data are obtained using inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation and olfaction during the physical examination. Objective data are also called signs. Although subjective data are usually obtained by interview and objective data are obtained by physical examination, it is common for the client to provide subjective data while the nurse is performing the physical examination, and it is also common for the nurse to observe objective signs while interviewing the client during the history (Brown & Edwards 2012).

Before the assessment

Preparing the client before the assessment involves (Crisp & Taylor 2009):

• A full explanation of the type of assessment to be performed

• An opportunity to empty the bladder and/or bowel. The client will feel more comfortable and the assessment will be performed more effectively if the bladder and rectum are empty

• Providing privacy by closing any doors or windows or by drawing the screens around the bed

• Providing a drape for warmth and privacy. The upper bedclothes should be folded to the bottom of the bed

• Assistance to the required position (information on various positions is provided in Ch 21). The pillows should be arranged to provide comfort and support. The positions normally used are:

Before the assessment the nurse may need to assist the medical officer in collecting the equipment required. Check each health facility’s protocol for the list of equipment and procedure outline.

During the assessment

During the assessment the nurse should remain with the client to provide physical and emotional support and assist when a change of position is required, remembering to provide adequate physical support and privacy (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Emotional support is partially provided by the nurse’s presence, and further support may be given in the form of encouragement and explanations of what is to happen. The nurse may also be required to assist the medical officer or receive any specimen obtained.

After the assessment

The client is assisted into a position of comfort, clothing is readjusted and the bedclothes are arranged to meet needs. If a rectal or vaginal examination was performed, the person should be provided with tissues to wipe off any excess lubricant (Crisp & Taylor 2009). The equipment is removed and attended to in the appropriate manner. Any specimens are despatched to the laboratory as soon as possible. The assessment and the person’s response to it is reported to the nurse in charge and documented.

ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUES

Inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation and olfaction are the five basic assessment techniques. Each skill enables the nurse to collect a broad range of physical data about clients (Brown & Edwards 2012).

Assessment through inspection

While observation of all the aspects mentioned in this chapter is essential, one of the most important skills a nurse develops is the ability to look at a client and determine whether they are comfortable. A client’s comfort depends on many things, the most basic of which are that needs for hygiene, posture, maintenance of body temperature and freedom from pain are met. deWit (2009) lists the following as items that the nurse observes and assesses when looking at a client:

As well as observing and assessing the client and their needs, the nurse must also use the sense of sight to assess the functioning of equipment used in client care. Nurses assess various items of equipment to determine whether they are functioning correctly when they are in use, for example:

While enrolled nurses may not be directly responsible for the management of specific items of equipment, they have a responsibility to observe their functioning and report any deviations from normal immediately to the appropriate person so that appropriate measures can be taken.

Assessment through palpation

Palpation uses the sense of touch. Through palpation the hands make delicate and sensitive measurements of specific physical signs. Palpation detects resistance, resilience, roughness, texture, temperature and mobility. The nurse uses different parts of the hand to detect specific characteristics. For example, the back of the hand is sensitive to temperature variations. The pads of the fingertips detect subtle changes in texture, shape, size, consistency and pulsation of body parts. The palm of the hand is sensitive to vibration. The nurse measures position, consistency and turgor by lightly grasping the body part with fingertips. Assist the client to relax and position comfortably as muscle tension during palpation impairs the ability to palpate correctly. Asking the client to take slow, deep breaths enhances muscle relaxation. Palpate tender areas and ask client to point out areas that are more sensitive and note any nonverbal signs of discomfort (Elkin et al 2008).

The sense of touch should be developed so that a nurse is able to detect abnormalities such as:

• Abnormally hot, cool, moist, dry, inelastic or roughened skin

• An excessively hard or soft peripheral vein

Touch is also used when examining a client by palpation or percussion. Palpation, usually performed by a medical officer or a registered nurse, is a technique whereby the examiner feels the texture, size, consistency and location of certain parts of the body with the hands. For example, the examiner may palpate the upper abdomen to determine the size of the liver.

Assessment through percussion

Percussion, usually performed by a medical officer or a registered nurse, is a technique in which the examiner strikes the body surface with a finger, producing vibration and sound. An abnormal sound suggests the presence of a mass or accumulation of fluid within an organ or cavity. For example, the examiner may percuss the posterior chest wall to determine the presence of fluid in the lungs.

Assessment using the sense of auscultation

It is important that a nurse learns to listen effectively, so that not only what a client says is registered but also the tone of voice, which often conveys a great deal. A nurse must also learn how to recognise abnormal sounds. Information on the art of effective listening in communication is provided in Chapter 6 and emphasises the importance of recognising that listening is an active process that involves much more than just hearing the spoken word. In client care, recognising abnormal sounds involves the ability to detect:

• Abnormalities of breathing; for example, respirations that are wheezing, noisy or distressed

• Abnormalities of heart sounds, blood pressure, bowel sounds or fetal heart sounds, when using a stethoscope

• Manifestations of a client’s distress; for example, coughing, expectorating sputum, vomiting, crying or moaning

• Changes in the sound or rhythm of technical equipment such as suction or artificial ventilation apparatus.

Auscultation is listening with a stethoscope to sounds produced by the body. To auscultate correctly, listen in a quiet environment. To be successful, the nurse must first be able to recognise normal sounds from each body structure, including the passage of blood through an artery, heart sounds and movement of air through the lungs (Elkin et al 2008).

Assessment using the sense of olfaction (smell)

A well-developed sense of smell enables a nurse to detect odours that are characteristic of certain conditions. Some alterations in body function and certain bacteria create characteristic odours, for example:

• The ‘fishy’ smell of infected urine

• The ammonia odour associated with concentrated or decomposed urine

• The musty or offensive odour of an infected wound

• The offensive rotting odour associated with gangrene (tissue necrosis)

• The smell of ketones on the breath in ketoacidosis (accumulation of ketones in the body)

• The smell of alcohol on the breath, due to ingestion of alcohol

• Halitosis (offensive breath) accompanying mouth infections; for example, gingivitis or certain disorders of the digestive system; for example, appendicitis

• The foul odour associated with steatorrhoea (abnormal amount of fat in the faeces)

• The characteristic odour associated with melaena (abnormal black tarry stool containing blood)

• The faecal odour of vomitus associated with a bowel obstruction

• Bromhidrosis (offensive smelling perspiration) caused by bacterial decomposition of perspiration on the skin.

Assessment using equipment

A nurse should acquire proficiency in the correct operation of equipment used to provide information about a client (Crisp & Taylor 2009); for example:

• Tape-measure; for example, to measure head, limb or abdominal circumference

Clinical Scenario Box 17.1

A 55-year-old male client presented at the Emergency Department with dyspnoea. He claims that he has been having difficulty breathing for the past 3 days. It gets worse when walking up stairs and unloading groceries from the car.

• Inability to complete sentences, moderately obese

• Physical assessment: BP 145/89 mmHg, RR 22/min with distended neck veins and productive cough

These primary observations seem to indicate a complication related to circulation and ineffective gaseous exchange. Therefore, the focused assessment will be aimed at managing this client’s cardiorespiratory system and the nursing interventions will be aimed at managing actual and potential complications related to breathing and comfort.

ROUTINE SHIFT ASSESSMENT

Each client should also be assessed at the beginning of each shift, as this helps the nurse to establish priorities of care and organise the work for the shift (Elkin et al 2008). Table 17.3 outlines the routine shift assessment. The nurse introduces themself to each client at the start of the shift and observes:

Table 17.3 Checklist for routine shift assessment

It is important to note that a client should be assessed whenever you first have contact with that client (Elkin et al 2008). Nurses also need to:

• Ascertain the time of the last bowel movement

• Check tubes and equipment (IV lines, nasogastric tubes, urinary catheters, dressings, wound suction devices, oxygen rates, traction)

• Ensure that call bell, TV control, water and tissues are in reach

• Check that room temperature is suitable

• Determine which supplies will be needed in the room for the remainder of the shift.

See also Table 17.3.

DIAGNOSTIC INVESTIGATIONS

Apart from the physical examination, specific tests may be performed to assist diagnosis or aid in evaluating the client’s condition. Diagnostic procedures include:

The nurse may be involved in preparing the client before a diagnostic procedure, assisting throughout the procedure and providing care after the procedure (Crisp & Taylor 2009). To determine the specific preparation and post-test care required for each procedure, the nurse should refer to the healthcare facility’s policy manual.

Preparing the client before any diagnostic procedure involves both physical and psychological preparation. The nurse should explain the purpose of the test and the procedure. If the client understands what is to happen and why, they may be less anxious about the test. The nurse should ensure that the client is informed of when, where and who will perform the test, and that the client’s informed consent has been obtained. Many tests, especially those of an invasive nature, require that the client gives informed consent for the test to be performed.

RECORDING AND REPORTING

After conducting a general health assessment the nurse should document the collected data as follows (Elkin et al 2008):

• Record the client’s vital signs on the vital signs chart

• Record the description of alterations in the client’s general appearance

• Describe the client’s behaviours using appropriate terminology. Include the client’s description of their own signs and symptoms

• Report abnormalities and acute symptoms to the registered nurse or medical officer.

TEACHING CONSIDERATIONS

While conducting the general survey, the nurse should use it as an opportunity to undertake health education with the client (Crisp & Taylor 2009). The following could be incorporated:

• During the general survey, inform the client of the acceptable ranges for vital signs and normal weight for height

• Discuss the client’s dietary intake and discuss any problems the client has in terms of food preparation or food selection

• If the client has been undertaking any high-risk behaviour activity such as smoking, overexposure to the sun, drinking alcohol; discuss the health risks of these.

Clinical Scenario Box 17.2

The following are details of Pamela’s health assessment:

• A 64-year-old female with 4-year history of type 2 diabetes with noncompliance to medication

• Physical assessment: BMI 32.6 kg/m2, BP 154/96 mmHg, RR 20/minute, Pulse 88/min

• After a physical health assessment was conducted, a pressure sore was identified on one of Pamela’s right toes. Pamela was not aware of this sore.

• Pamela will require a referral to a diabetic educator who can provide vital information about living with diabetes. She will also benefit from a referral for dietitian who can perform medical nutrition therapy assessments with focus on weight loss.

• The fact that Pamela was not aware of the sore on her right toe seems to suggest that she may have reduced peripheral sensation. This finding is typical in clients developing peripheral neuropathy, which is one of the complications of type 2 diabetes. Therefore, Pamela will need to be educated about the importance of foot care as part of her discharge planning.

CLINICAL HANDOVER

Handover is about communicating the client’s relevant information including health assessment, past medical history, current health status and overall management to the healthcare team to establish an effective continuity of care (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2010). Nurses have the most contact with each client. Therefore, they play a significant role in being able to identify the subtle changes that the clients may be presenting prior to a deteriorating event.

The OSSIE Guide to Clinical Handover Improvement has been developed by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. The document is aimed at improving nursing and medical handover—which includes verbal and documented formats—from shift to shift.

According to the guide, clinical handover is the transfer of professional responsibility and accountability for some or all aspects of a client or a group of clients, to another person or professional group on a temporary or permanent basis. It is identified that proper clinical handover can reduce risk of unnecessary delays in diagnosis, treatment and care. See Chapter 6 for further information on clinical handover.

ADVANCE HEALTH DIRECTIVES

With advances in medical technology, there has been increasing effort by healthcare professionals to reduce mortality and prolong life through artificial means. However, this gives rise to concerns that some interventions may in fact compromise clients’ quality of life (Lee 2008). This is especially so when the treatments may be of limited or no benefit to the clients.

When the client can no longer communicate their own decision, doctors and family can find themselves having to decide for them when to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments (RACGP 2010).

An advance health directive is a document voluntarily completed by an individual which specifies their decisions about future medical treatment (see Clinical Interest Box 17.2).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 17.2 Advance Health Directives

What is an Advance Health Directive?

An advance health directive is a document that contains the client’s decisions about future treatment—including medical, surgical and dental treatment and other healthcare—that they are prepared to accept, or refuse.

On admission, it is important to find out if the client has completed an advance health directive prior to admission to the healthcare setting. If there is one, it must be acknowledged, clearly documented and handed over to all members of the healthcare team.

Summary

The general health assessment is conducted to assess the function and integrity of the client’s body. The health assessment is conducted in a systematic manner that requires the fewest position changes for the client. The data obtained in the physical health examination supplement, confirm or refute data obtained during the nursing history.

1. Mr Leonard enters hospital with a history of weight loss and general fatigue. What questions will you ask to elicit the appropriate responses that will help to establish the nursing assessment?

2. Forty-three-year old John Stuart complains of increasing symptoms of dyspnoea and cough which worsen upon physical exertion. He also experiences chest tightness with occasional wheezing symptoms. Identify the diagnostic investigations that could be carried out to determine the cause(s) of John’s condition. Explain the necessary preparation required for each of the investigations.

3. Enrolled nurses require well-developed assessment skills. What strategies will you use to ensure that you acquire, practise and retain the relevant skills and related knowledge to support your nursing practice?

References and Recommended Reading

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. OSSIE Guide to Clinical Handover Improvement. Online. Available: www.health.gov.au/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/content/priorityprogram-05_ossieguide, 2010.

Australian Nursing & Midwifery Council (ANMC). National Competency Standards for the Enrolled Nurse. Online. Available: www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Statements/Codes-Guidelines.aspx, 2002.

Berman A, Snyder S, Kozier B, et al. Kozier and Erb’s Fundamentals of Nursing Vol 2. 2nd edn. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Australia, 2012.

Brown D, Edwards H. Lewis’s Medical–Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems, 3rd edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2012.

Crisp J, Taylor C. Potter and Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 3rd edn., Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

deWit SC. Fundamental Concepts and Skills for Nursing, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2009.

Edvardsson D, Nay R. Acute care and older people: challenges and ways forward. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;27(2):63–69.

Elkin M, Perry A, Potter P. Nursing Interventions and Clinical Skills, 4th edn. Canada: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

Lee J. Autonomy and quality of life for elderly patients. Virtual Mentor. 2008;10(6):357–359.

Pellico LH, Friedlaender L, Fennie K. Looking is not seeing: Using art to improve observational skills. Journal of Nursing Education. 2009;48(11):648–653.

Phaneuf M. Clinical judgement—an essential tool in the nursing profession. Online. Available: www.infiressources.ca/fer/Depotdocument_anglais/Clinical_Judgement%E2%80%93An_Essential_Tool_in_the_Nursing_Profession.pdf, 2008.

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Guidelines. Advance Care Plans. Online. Available: www.racgp.org.au/guidelines/advancecareplans, 2010.

Zambas SI. Purpose of the systematic physical assessment in everyday practice: critique of a “Sacred Cow”. Journal of Nursing Education. 2010;49(6):305–310.

Advance Health Directives (AHD), www.health.wa.gov.au/advancehealthdirective/home/faqs.cfm#1.

Centre for Culture, Ethnicity & Health, www.ceh.org.au.