Florence Nightingale

In 1853 Florence Nightingale went to Paris to study with the Sisters of Charity and was later appointed superintendent of the English General Hospitals in Turkey. During this period she brought about major reforms in hygiene, sanitation and nursing practice and reduced the mortality rate at the Barracks Hospital in Scutari, Turkey, from 42.7% to 2.2% in 6 months (Woodham-Smith, 1983). It was her work at Scutari that led to her becoming known as the founder of modern nursing. Florence Nightingale established the first professional nursing philosophy based on health maintenance and restoration in Notes on nursing: what it is and what it is not (Nightingale, 1860). Her views on nursing were derived from both her intense community involvement with people of all classes and a strong spiritual philosophy, developed in her adolescence and adulthood (Gill, 2004), and reflected the changing needs of society. She saw the role of nursing as having ‘charge of somebody’s health’ based on the knowledge of ‘how to put the body in such a state to be free of disease or to recover from disease’ (Nightingale, 1860). During the same year as her book was written, she developed the first organised program for training nurses, the Nightingale Training School for Nurses at St Thomas’s Hospital in London.

Nightingale was the first nurse epidemiologist and she developed some of the first known graphical representations of health-related data, which she used to describe the situations she witnessed in the British Army in her book of 1858, Notes on matters affecting the health, efficiency, and hospital administration of the British Army. Her statistical analyses connected poor sanitation with cholera and dysentery. She viewed nursing as a search for truth in finding answers to healthcare questions (Gill, 2004). Nightingale had a profound effect on both Australia and New Zealand, with the governments of both countries writing to Britain to request that Nightingale-trained nurses be sent to the colonies to improve the standards of care being provided in hospitals.

The influence of Nightingale could have been even more profound in New Zealand had it not been for an accident of timing. Governor Gray, the governor of New Zealand, wrote to Florence Nightingale asking her opinion on how he should manage the health needs of the ‘native’ population. However, by the time Nightingale replied, Governor Gray had been posted to South Africa and it was not until a century later that the letter from Nightingale was discovered. Lady Jocelyn Keith, a New Zealand Nightingale scholar, discovered the letter, in which Nightingale had suggested a radically different approach to indigenous health from the medical advice at the time. Nightingale’s suggestions were based on what we would recognise today as contemporary and sound public health principles, such as increasing the distance between beds.

Historical perspectives on Australian and New Zealand nursing

The history of nursing in Australia is inextricably linked to the country’s penal past. In the establishment of the colony at Sydney Cove, little attention was paid to the provision of care for the ill and infirm. When Sydney Hospital was opened in 1811, the majority of nurses were convict women, with some convict men also performing nursing duties. They were provided with their keep, but no wages, in exchange for their labour. The nurses were frequently described as being of poor character, with drunkenness common while on duty (McCoppin and Gardiner, 1994).

One of the first Australian lunatic asylums was opened at Tarban Creek in 1838. Untrained mental attendants staffed the institution and physical restraint was used as the primary means of control for large numbers of disturbed people. There was virtually no emphasis on treatment, but rather removal from society.

The first trained nurses arrived in Sydney in 1838; they were five Irish Sisters of Charity. The Nightingale influence began in 1868 when Lucy Osburn and her four Nightingale nurses landed. Gradually, the Nightingale principles for the care of the physically ill were adopted. Nurses were trained in practical skills such as the application of dressings, leeching and the administration of enemas. Of equal importance were the character traits of punctuality, cleanliness, sexual purity and, above all, obedience (McCoppin and Gardiner, 1994).

A large proportion of nursing work was akin to housekeeping, dominated by domestic tasks. It was, however, acknowledged that diligence and compassion were desirable characteristics in those who cared for the sick.

New Zealand, in contrast, was settled a little later by ‘free settlers’, largely Scottish in background, and in family groups, as opposed to the largely male population of convicts and gaolers in Australia.

A fundamental difference between the two countries occurred in the relationships that developed between Europeans and the indigenous populations. The cohabitation of both countries was far from peaceful. A formal treaty recognising indigenous rights eventuated only in New Zealand; there has never been such a treaty developed in Australia. The Treaty of Waitangi has been a fundamental and governing platform for indigenous and European relationships to this day. In Australia the history is more troubled, and the health status of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today has its origins in the early treatment of black by white. Until relatively recently, Australia was regarded in law as terra nullius (‘the land of no one’) prior to European settlement. This legacy of poor relationships in the past may be seen as contributing to the contemporary health inequalities so vividly and politically highlighted through federal intervention in 2007 (see Chapter 2).

By the late 1800s, both countries had experienced a large population increase in response to the discovery of gold. This increased the need for hospitals, and by 1870 New Zealand had 37 hospitals. Another common development was the perceived need to develop places of asylum for ‘lunatics’, and both countries had developed lunatic asylums by the mid-1880s.

Through the latter half of the 1800s the governments of both countries saw the need to improve hospital standards, and their governments independently sent word to Britain to send Nightingale nurses to the colonies. Under the Nightingale influence, schools of nursing were established and training programs implemented. It was not long before this new style of nurse was in need of professional affiliation. Professional associations and professional journals began independently in each country within a matter of years of each other. The Australasian Trained Nurses Association was founded in 1899 in New South Wales and the first journal was published in 1903 (Russell, 1990). The New Zealand Trained Nurses Association was established in 1909, combining pre-existing local associations from Christchurch, Dunedin, Wellington, and the New Zealand journal Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand was begun in 1908 (Papps, 2002).

It was New Zealand which led the way in professional regulation. Under the stewardship of Grace Neill, a senior government nurse who had addressed the International Council of Women’s conference in London in 1899 on the need for the registration of nurses, New Zealand passed its Nurse’s Registration Act in 1901. Australia, now federated, still maintained state control of nursing and the states trickled along with their independent regulation of nursing, from South Australia in 1920 to the Australian Capital Territory in 1933. The New South Wales registration Bill, passed in 1924, was the culmination of over 20 years of struggle through parliament for such recognition. This differing pace of political change—affecting healthcare, nursing education and practice—remains a difference between New Zealand and Australia today.

Nursing in the United States began its association with the university sector early, with the first university-affiliated nursing program starting in 1901 and the first professor of nursing appointed in 1907—Mary Adelaide Nutting. This was significant in the early establishment of research and publication as important nursing roles. The first research journal, Nursing Research, was published in 1952 and continues today. Australia and New Zealand both suffered from the lag in linking to the education sector. They both continued to follow the British tradition of hospital-based training. In 1925 in New Zealand there was an innovative attempt to have a university nursing program at the University of Otago, but it foundered for lack of funding. In 1928 a postgraduate school was set up in Wellington, but it was for nurses already registered and was not linked to a traditional education path through master’s and doctoral work. Hospital training remained the basis of nursing education in both Australia and New Zealand until the 1970s.

In 1970 New Zealand commissioned a review of the nursing education system and the report that followed, the Carpenter Report (1971), clearly advocated the education of nurses to take place within an educational institution. However, the government decided that the appropriate place would be not the university but rather the polytechnic system. This was understandable, given the geographical accessibility of the polytechnics, but it had a consequence of keeping the education standard at a diploma level for nearly 20 years and of not encouraging higher degrees for students or even for teaching staff. A further consequence was the lack of emphasis on research and publications that would have come from a university presence. New Zealand nurses’ pre-registration programs were held at diploma level until 1992, when the Education Amendment Act 1990 enabled polytechnics to offer degrees.

In Australia during the 1960s and 1970s there were no fewer than 15 expert committee reports about nursing and nursing education. Among them the influential Truskett Report (1970) recommended that control of nursing education be transferred from the Minister for Health to the Minister for Education, but this movement of control was met with significant disagreement within the profession (Russell, 1990).

The first Australian diploma-level basic nursing course was introduced into the College of Nursing (Australia), a college of advanced education (CAE) in Melbourne in 1975, closely followed by similar courses in New South Wales, Western Australia and South Australia; by 1982 Queensland and Tasmania also had tertiary nursing programs (Russell, 1990). However, hospital training continued to be the dominant mode of education until 1985, when all nursing education programs in New South Wales were moved to the CAE sector and hospital training ceased. The whole country followed not long after, and the education of registered nurses has taken place in the tertiary sector across Australia since 1990.

A significant difference in nursing education between Australia and New Zealand has been the location of nursing education. In Australia, the university base has meant that nurses have access to the full range of tertiary programs—graduate certificates, graduate diplomas, masters, and doctoral programs—both the doctor of philosophy (PhD) and more recently the professional doctorate or doctor of nursing (DNurs). In New Zealand, Massey University was the only venue for obtaining university-based postgraduate degrees in nursing until 1994, when a second program was opened at Victoria University. Once two programs existed and entrance criteria were made less restrictive, there was a huge increase in the number of nurses stepping forward for further study. Recently, polytechnics and other universities have started postgraduate nursing education in New Zealand.

One further distinction between the two countries has been the emphasis in nursing on culture. In Australia, for many years there has been recognition of the multicultural nature of the country but little emphasis on the care of Indigenous people. In New Zealand the emphasis has been reversed. New Zealand sees itself first as a bicultural country, with many different cultures in the non-indigenous population. The specific concern for the Māri population’s interaction with healthcare led to the development of the concept of cultural safety, which was introduced into nursing curricula in 1992. The definition of the Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ, 1992:1) at the time was:

The effective nursing of a person/family from another culture by a nurse who has undertaken a process of reflection on our cultural identity and recognises the impact of the nurses’ culture on our nursing practice.

The Florence Nightingale pledge often used in both countries at graduation ceremonies included the words ‘regardless of colour or creed’. Papps (2002:96) suggests ‘cultural safety requires that nurses provide care regardful of those things which make people unique’. The NCNZ published a comprehensive guideline on cultural safety in nursing education and practice in 2005. These were amended and updated in 2011 and are available on NCNZ’s website (www.nursingcouncil.org.nz). The debates between cultural safety and the more multicultural focus of transcultural nursing are taken up in Chapter 17 of this textbook.

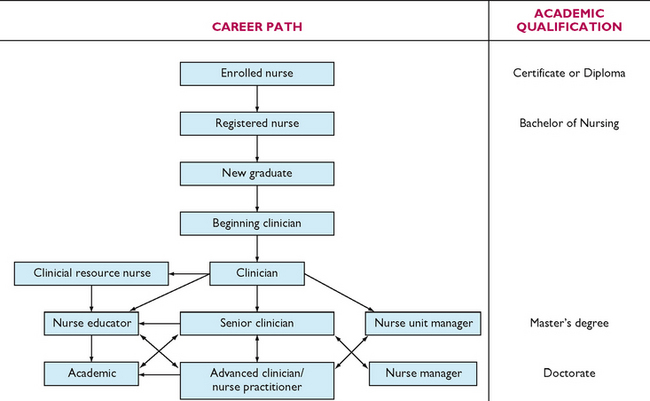

The 1990s brought turmoil to healthcare systems internationally, with resulting changes to nursing work role, workload and control over work. These changes are discussed in more detail later, but the outcomes for nurses, despite the differences in political approach, have led to some opportunities for change. Both Australia and New Zealand have introduced nurse practitioner (NP) roles where nurses, duly authorised, have the authority to prescribe medications, order diagnostic and pathology tests, and refer clients to other healthcare professionals as required. This is an essential final step in the clinical nursing career path, and means that career paths for nurses are available in management, education and clinical practice.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Florence Nightingale was a most extraordinary nurse, focused on public health as much as personal healthcare. Discuss in a small group the similarities and differences between Nightingale thinking and the return to a primary healthcare agenda of the current Western healthcare systems.